HORIZON ADVISORY

September 2025

Executive Summary

Hemispheric trade and security matter more to the United States now than ever before. And China’s rise as a great power competitor has left America’s backyard more contested an environment than ever before.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is well on its way to seizing influence and coercive leverage across Latin America. That has been well recognized in a number of hubs where Washington is starting to compete: For example, the economic powerhouse of Brazil; the pariah state of Venezuela; and throughout the mineral rich lithium triangle of Chile, Argentina, and Bolivia. But China’s influence does not end in those hot spots. In Peru, for example, Beijing has been deploying its subversive, cross-domain playbook for decades. And that Peruvian positioning threatens to help China lock in its in influence throughout the region – to deleterious effect for American efforts to consolidate security and economic power in the Western Hemisphere.

Peru is a keystone in China’s Latin America plans. It offers transit pathways and infrastructures that will be instrumental in stringing together Beijing’s other bets in the region. China is building a pair of megaprojects in the region toward this end. The first into operation is the new port in Chancay. The massive megaport is China’s first deep water Pacific port in Latin America. It allows China to bypass the Panama Canal while cutting transit times and costs for trans-Pacific trade with Latin America. And the COSCO-developed project promises to connect China’s infrastructure and resource investments elsewhere in the region, including in Brazil, via another megaproject, a bi-oceanic railway that locks in Chinese influence and presence. China is backing the development of a rail line starting in Brazil and weaving through Peru to supply Chancay. That rail line is shaping up to be the latest in a long string of wins from China’s subnational influence playbook in Peru. The routing of the rail line appears set to deliver significant financial impact for the Mayor of Lima. He founded and owns a sizeable stake in PeruRail. That rail company already benefits tremendously from freight business generated at a Chinese-owned mine in Peru. And its Cusco rail hub – where the Lima Mayor Rafael López Aliaga also owns a portfolio of significant hotel properties – has been selected as a vital artery through which the Sino-Brazilian rail routing will pass to get to the Chancay Port.

Beijing’s presence in Peru is anything but benign The CCP wants to redeem economic gain More even than that, China’s leaders want to guarantee coercive leverage over the supply chains and politics that will decide global power over the long term. This Peruvian gambit is consistent with China’s approach to power projection: Beijing wants to lock in its hard power and protect its overseas investments through control of critical infrastructure. Doing so delivers immediate benefits to China’s State-backed multinationals while providing the CCP with a long-term power base from which to coerce and compel. That’s clear at Chancay. It’s clear with the bi-oceanic rail connecting Brazil to the new megaport and establishing China’s “strategic fulcrum” in Latin America. And it’s clear with the financial boons headed to the Mayor of Lima.

China wants regional dominance in the Western hemisphere. That imperils US national security interests, trade interests, and the corresponding economic and security interests of all of Washington’s partners in Latin America.

The United States needs to be aware of Beijing’s positioning and intent. Up to this point, Peru has fallen off the radar. The United States needs to understand China’s investments in Peru –including efforts to cultivate subnational influence through elite capture – and use that understanding to develop a strategic response.

Such a response must get ahead of China’s next move. It also has to be comprehensive: Washington should deploy a suite of responsive tools across diplomatic, economic, and security instruments of power. And those instruments need to address Beijing’s economic levers at the macro and micro layers. At the macro level, for example, the United States should leverage bilateral trade and investment agreements in Peru. China has outsize influence in Peru’s economy and strategic momentum. But hemispheric markets still matter for Lima. At the same time, US policy needs also to recognize that China’s subnational influence agenda has been applied across Peru and with great success in Lima. Washington’s approach to competing needs to identify and protect against the influence of captured elites, on the one hand, while advancing an affirmative, pro-hemispheric growth agenda on the other.

Visions for renewed ties across the Western hemisphere that can support US economic growth, energy dominance, and regional security depend not just on responding to China but on taking the offensive in this critical theater. That offensive should start with interventions from the US government to block Chinese investment in Peru at the Port of Chancay and in Brazil with the bi-oceanic railway set to connect to Chancay. Doing so should be an urgent effort to prevent Beijing’s Panama Canal 2.0 from locking in regional influence that will be far more costly and complicated to rollback years from now.

The State Department can follow those directions with subnational efforts to blunt China’s inroads with key influencers, like the Mayor of Lima. And the US military, under the leadership of US Southern Command, can socialize the operational and intelligence security risks that Chinese dominance of port and rail infrastructure in the region carry. That awareness campaign should also be paired with re-allocation of military assets that may be needed better to surveil and protect against China’s presence at Chancay and throughout Peru and Brazil.

Those actions offer a tactical start. And they can set the stage for a broader strategic push in the Western Hemisphere. The United States needs to revamp regional trade and investment relations and leverage those as a pathway for enhanced strategic ties in places like Peru and its vibrant economic and resource rich neighbors. A prosperous and strategically aligned Latin America can deliver hemispheric security and a foundation for the United States properly to offset Beijing’s global ambitions.

Introduction

The Panama Canal is a vital strategic corridor for the United States. Its 51-mile stretch allows seaborne trade to transit from the Pacific to the Atlantic with efficiency. It delivers logistical value for both commercial routes and military positioning. The canal is particularly critical for the United States: Over 70 percent of the Panama Canal’s traffic is transiting either to or from the United States.1

In 1999, President Bill Clinton’s State Department investigated risks that might emerge from Chinese-linked investment controlling both the Balboa and Cristobal ports, covering the Pacific and Atlantic ends of the Canal, respectively. The Clinton State Department determined that there was nothing to see there. It concluded that a Hong Kong-headquartered operation controlling the canal did “not represent a threat to canal operations or other US interests in Panama.”2

Fast forward some 25 years later and the risks posed by Chinese investment in the canal are obvious, non-controversial, and immediate. The United States is actively working to rollback Chinese access to and leverage over the canal. President Trump told Congress in March that “to further enhance national security, my administration will be taking back the Panama Canal and we’ve already started doing it.”3 Secretary of War Pete Hegseth shortly thereafter visited Panama and declared that the United States was set to “take back the Panama Canal from China’s influence.”4 These statements coincided with dealmaking efforts led by a BlackRockbacked consortium to buyout port operations at each end of the canal.

But the defensive campaign is easier said than done. Negotiations over the buyout remain in an uncertain limbo.5 And diplomatic tension has continued to escalate in the months since. At an August United Nations Security Council meeting, China’s permanent representative to the UN rebuffed the US campaign to reverse the operation of the canal:

The US is fabricating lies and making groundless attacks on China simply to create an excuse for its control of the Panama Canal … China firmly opposes economic coercion and bullying and urges the US to stop fabricating rumors and causing trouble.6

The Panama Canal has managed to make it to the top of the agenda in a busy US-China relationship. It registers for strategic importance alongside unprecedented trade war backand-forths, debate about artificial intelligence competition, and the imposition of export

1 “Market Intelligence: Panama: The Panama Canal,” US International Trade Administration, May 3, 2023, https://www.trade.gov/market-intelligence/panama-panama-canal

2 Lino Gutierrez, “The Security of the Panama Canal,” US Department of State: Statement before the US Senate Armed Services Committee, October 22, 1999, https://19972001.state.gov/policy_remarks/1999/991022_gutierrez_panama.html

3 “Presidential Address to Congress,” March 4, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jjHTr0Cd_XA.

4 Mithil Aggarwal, “Trump was touting his Panama victory. Then China stepped in.,” NBC News, April 9, 2025, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/trump-panama-canal-take-back-military-china-blackrock-rcna199438

5 “CK Hutchison will not sign deal to sell strategic Panama ports next week, sources say,” CNBC, March 29, 2025, https://www.cnbc.com/2025/03/29/ck-hutchison-wont-sign-deal-to-sell-panama-ports-to-blackrock-led-group.html

6 “

[China refutes US at UN Security Council over Panama Canal issue: Stop spreading rumors and causing trouble],” Global Times, August 13, 2025.

controls on cutting-edge technologies. Just as in those other high-profile cases, the future of the dispute is uncertain: It is not clear how exactly the Panama Canal tensions will be resolved between the Trump Administration and interlocutors in Xi’s Chinese Communist Party.

What is clear is that US recognition of the risk posed by Chinese influence of the canal is overdue – and that that tardiness imposes serious costs. If the Clinton administration had come to a different conclusion two decades ago, Washington would not currently be fretting Beijing’s influence over one of the most strategically important channels of global trade – and, by extension geopolitical power and influence.

What is equally clear is that, caught up in the Panama Canal debate, Washington is fighting yesterday’s battles and at the expense of today’s. China is several moves ahead. And that asymmetry threatens both American influence and the security and prosperity of Latin America.

This competitive reality is evident in, for instance, the Port of Chancay in Peru. While Washington tries to push back against Panama, Beijing has already turned on a new bi-oceanic pathway to bypass Panama for much of its regional trade. The Chancay Port in Peru – and a proposed bi-oceanic railway feeding it from Brazil – will allow China drastically to cut its costs and times for trade with Latin America. It will do so in a fashion that networks key resource extraction and production hubs across the region. And it will do so by way of a robust commercial and subnational influence toolkit that will be difficult and costly to rollback.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative keystone projects in Peru promise new, strategic value for China. They deserve new, strategic scrutiny from the United States.

The Sino-Peruvian Economic Partnership

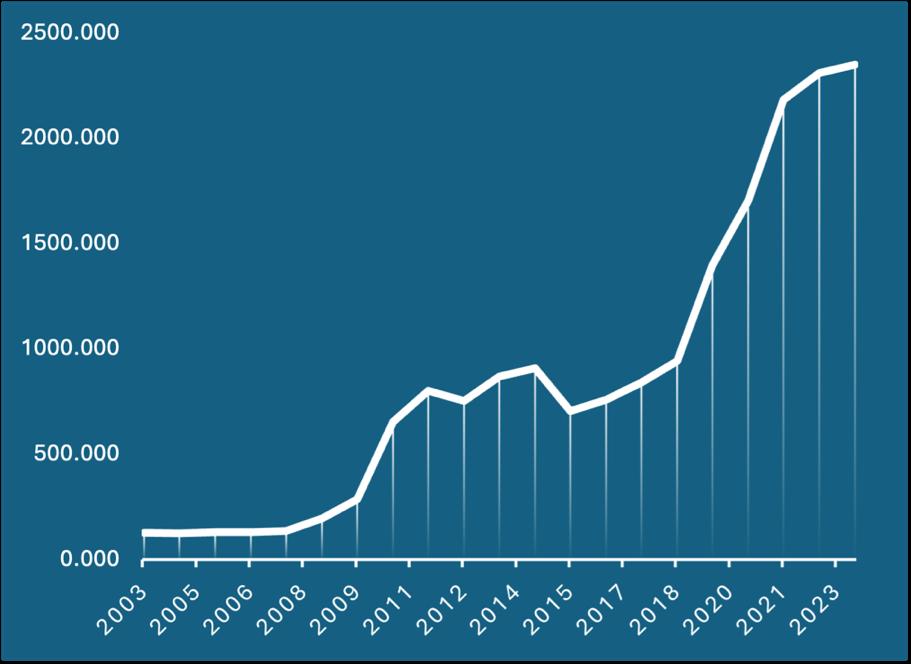

China’s Peruvian gambit is not new. It builds on a steady and increasing stream of economic ties that bind the Latin America hub to Chinese investment, trade, and infrastructure development.

China treats the Sino-Peruvian relationship as a “comprehensive strategic partnership,” making Peru unique among China’s Latin American partners. Beijing designated the two countries’ formal diplomatic relations as a “strategic partnership” in 2008 and upgraded them to the rarified level of “comprehensive strategic partnership” in 2013. Both sides celebrate that relatively recent development as a natural progression of the long-standing relationship, one also reflected in, as of May 2024, a national Peruvian holiday on February 1st dubbed “China Peru Friendship Day.”7

China has been Peru’s largest trading partner for over a decade. Trade between the two countries has consistently grown since they signed a free trade agreement in 2009 – making Peru China’s first free trade agreement partner in Latin America. In 2023, bilateral trade reached over $37 billion. That high watermark was a function of a consistent trend: Peru's exports to China have increased by 325.9 percent over the past 14 years, with an average annual growth rate of 13.2 percent.8

Chinese overseas direct investment into Peru has steadily built up its stock over the same period of time – and Peru has served as the second largest destination for Chinese investment in Latin America.

China’s Overseas Direct Investment (Stock) in Peru, 2003-2023 (USD, mm)

7 “中秘友谊源远流长,经贸关系迈上新台阶 [China-Peru friendship has a long history, and economic and trade relations have reached a new level],” China Daily, November 19, 2024.

8 “中秘友谊源远流长,经贸关系迈上新台阶 [China-Peru friendship has a long history, and economic and trade relations have reached a new level],” China Daily, November 19, 2024.

The Belt and Road Initiative has facilitated China’s inroads over recent years. Peru officially joined China’s Belt and Road with a joint memorandum of understanding in 2019. That led to a rapid expansion of Chinese-backed engineering and construction projects. Those encompass construction of everything from roads and bridges to airports, schools, and hospitals. And China’s direct investment into Peru has allowed Chinese State-backed and State-owned actors to secure points of control or influence over critical infrastructures. For example, in 2020, China Yangtze Power completed its takeover of Lourdes, the largest power company in Peru.9 This is precisely Beijing’s intention. The PRC’s framing of Peru’s role in the Belt and Road initiative describes the country as a keystone in a larger effort to secure influence across Latin America:

The Belt and Road Initiative has entered a new phase of high-quality development, injecting inexhaustible momentum into China's joint efforts with the Global South, including Latin America, toward modernization. The Belt and Road Initiative is deepening ties between China, Peru, and other Latin American countries, fostering deeper and more practical cooperation and common development between China and Peru, and between China and Latin America. Through policy coordination, infrastructure connectivity, unimpeded trade, financial integration, and people-topeople bonds, the Belt and Road Initiative is deepening ties between China and Peru, and between China and Latin America.10

China’s Belt and Road project certainly pursues and carries economic boons. But its centralized, State-guidance reflects a vision more nefarious than simple economic motives. Beijing uses the Belt and Road to secure influence and leverage. Beijing prioritizes partners with which it can sow dependency and through which it can project power. In Peru, that is on raw display with the routing of a proposed bi-oceanic railway that is set to generate a windfall for an important subnational leader in the Mayor of Lima. That is an invaluable type of influence. And Beijing captures it while also gaining the economic values that come with owning critical infrastructures like the railway and the mega port at Chancay to which it connects. Taken together, those projects and subnational influence combine to deliver a network that will allow China to box out any other competitors across the region.

Those soon to be realized strategic gains from China’s capture of Peru bring unanticipated risk – locally, regionally, and for the United States. As has been the case in other venues of Chinese overseas investment, that risk may only come into focus as high-profile, real-world infrastructures take root; as China cements the positioning it has so deliberately and painstakingly established; and when it is effectively too late to combat or unseat Beijing’s positioning.

9 ““秘中合作打开了一扇充满机遇之门” ["Peru-China cooperation has opened a door full of opportunities"],” People’s Daily, November 11, 2024.

10 “中秘共建“ 带一路”利好两国造福世界 [China and Peru jointly build the "Belt and Road" to benefit both countries and the world],” Xinhua, November 11, 2024.

Keystone Megaprojects

China aims to protect its global resource acquisition program – and overseas investments more generally – through its tangential dominance of processing and infrastructure. This may seem obvious. And it is. But it also defies conventional wisdom about the relationship between overseas economic dependencies and power projection.

American conventions assume that increased overseas investment will generate an increased necessity to invest in power projection capacity to protect those overseas assets as well as the global commons through which they must transit. Chinese strategy certainly benefits from American – and Western – defense of the global commons. Secure shipping lanes underwrite safe travel of seaborne trade for all trade participants, not just those friendly at any given moment with the US Navy.

But ultimately, China’s strategy prioritizes other, non-conventional power projection means for protecting its overseas investments. It invests in the downstream nodes of value chains on which its overseas resource assets depend – that is, the processing and refining necessary to take a raw material and convert it into its value-add purpose. China further locks in control of the infrastructures necessary to move those assets from their points of extraction into the global marketplace. When China builds a processing or refining facility or takes control of a port or railway, it is done so not for profit but for control. China’s national-level strategy of military-civil fusion codifies and operationalizes this logic to guarantee that control converts to leverage at the disposal of the Chinese Communist Party and the People’s Liberation Army.

That orienting strategy is on prime display in Peru. China wants to leverage its influence in Peru to lock in gains acquired throughout Latin American. And controlling Peru’s new largest port as well as the railway that connects the country to the rest of its resource-rich neighbors is just the way to do so. Discussion that follows will highlight both the Chancay Port and the bioceanic railway emanating from Brazil to deliver freight to Chancay. China built Chancay and has a hand in operated it; it has intervened with Brazil and along the proposed railway’s route to guarantee that the line services both this grand strategic ambition for Latin American and China’s subnational partners in Peru.

These twin, linked megaprojects are China’s power projection in the region; they should be perceived as the aircraft carriers that China does not need to deploy to protect its interests. They are vessels of military-civil fusion and economic warfare all in one – and they imperil US interests accordingly.

Chancay Port: China’s Pacific Hub in Latin America

China’s influence in Peru is not simply a story of dollars and cents. Infrastructure projects make Beijing’s positioning in the country tangible. The best demonstration is China’s keystone project in Peru: the Chancay Port. Strategically located north of Lima, Peru’s capital, Chancay is the only deepwater megaport project on Latin America’s Pacific coast. The State-owned conglomerate China Ocean Shipping Group (COSCO) led China’s investment in and development of the port

Chancay Terminal in Action

The Chancay project is a direct result of the 2019 memorandum of understanding signed between China and Peru to promote Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative. The port project is the largest Belt and Road Initiative project in Peru. And it is a regular focal point for the “Annual Conference on Practical Cooperation under the Belt and Road Initiative” co-hosted by Xinhua and Peru’s Andes News Agency.11

The Chancey project also poses a risk to Peru’s long-term economic and national security – as well as to American commercial and security interests. This port, like so much PRC infrastructure construction abroad, carries immediate economic rewards for Peru: It creates a much-need avenue to export the country’s rich natural resources generally, and to export them to China in particular. The problem is that that access to the Chinese market comes at the cost of both market and operational dependence on Bejing. China frames the effort as a “win-win” opportunity, but Beijing’s real goal is to ensure that Peru’s economy, and the larger regional economy rely on China. Beijing’s approach to building overseas infrastructure also requires countries to adopt Chinese technology, standards, and operators – and therefore to relinquish control over critical infrastructures.

Chancay went into operation in November 2024. It is already being touted as a landmark accomplishment by Chinese diplomats, politicians, and business leaders. Its launch was the focal point for a State visit to Peru by Xi Jinping that coincided with the 31st convening of the APEC Economic Leaders Meeting. Chancay also registered explicitly in the Joint Statement issued by both national governments following the Chinese Premiere’s visit: 11 “中秘共建“ 带一路”利好两国造福世界 [China and Peru jointly build the "Belt and Road" to benefit both countries and the world],” Xinhua, November 11, 2024.

Both sides congratulated the successful opening of the Port of Chancay, believing that it is of great significance and an important step in building Peru into one of the worldclass logistics, technology and industrial centers and strengthening trade relations between Latin America and Asia.12

Understandably, the Chinese State-owned enterprise that manages the port is similarly elated. He Bo, the local leader of COSCO Shipping Ports Peru Chancay, said in August 2025 that "the growth in transportation demand is faster than we expected."13 That demand reflects a commonality of a high-growth strategic and diplomatic relationship: China’s embrace of Peru is finding natural complements across economic sectors. That mutually beneficial alignment manifests in everything from the blueberry trade to national power infrastructure and the regional energy grid. That all suggests that Peru is headed down a path of dependency on Beijing. And the supporting infrastructure that will bring the port to life are the next front that look to lock in that dependency.

Bi-Oceanic Rail: The Linchpin for China’s “Strategic Fulcrum” in Latin America

The proposed rail line that will network Chancay to goods exported from Brazil furthers this risk. It cements China’s stranglehold over Latin American transit and trade as what Chinese observes call a “closed loop” system – one that feeds, responds to, and depends on Beijing.14 The proposed bi-oceanic rail link will make Chancay an even more central node in China’s Latin America network. The rail line will allow China to make more efficient its investments in upstream supplies as well as agricultural trade throughout Latin America. China’s investments in the port at Chancay are set to be immediately more valuable – and strategic – with the rail pairing that solidifies a Chinese-controlled “land-sea relay.” It provides China a bypass of the Panama Canal for its entire Latin American trade profile. With this rail line, Chancay becomes a “strategic corridor” not just a deepwater port. And China is leveraging its subnational influence playbook to guarantee that the rail line proceeds according to and ultimately serves Chinese interests in shaping Latin American economic development.

12 “中华人民共和国和秘鲁共和国关于深化全面战略伙伴关系的联合声明 [Joint Statement between the People's Republic of China and the Republic of Peru on Deepening Comprehensive Strategic Partnership],” PRC Ministry of Foreign Affairs, November 15, 2024.

13 “钱凯港助力跨大洋贸易“提速” [Chancay Port Helps Accelerate Transoceanic Trade],” Xinhua News Agency, August 1, 2025.

14 “巴西求助中国!建5000公里的铁路横贯东西通钱凯港! [Brazil seeks help from China! Build a 5,000-kilometer railway connecting east and west to the port of Qiancai!],” August 7, 2025.

Chinese Press Depiction of the Bi-Oceanic Railway

The “super railway” will cover a massive stretch of 5,000 kilometers. It is projected to shave 10 days off Sino-Brazilian trade routes and decrease logistical costs by up to 30 percent for goods moving from Brazil to Asia.15 It is cited as “not just an infrastructure project” and instead as “the South American version of the Belt and Road Initiative taking shape.”16 Chinese sources are confident that the project is “set to reconstruct the global circulation routes” of key strategic resources.17 Congestion at the Panama Canal and the risk of US objection to Chinese influence there are often cited as causes of the rail line’s bi-oceanic scope.18 Bypassing Panama will deliver an immediate and non-trivial return for Chinese trade with Latin America: Soybeans

15 “巴西求助中国!建5000公里的铁路横贯东西通钱凯港! [Brazil seeks help from China! Build a 5,000-kilometer railway connecting east and west to the port of Qiancai!],” August 7, 2025.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 “5月13日,两洋铁路连接巴西与秘鲁钱凯港,全⻓5000公里 [On May 13, the Transoceanic Railway connected Brazil and the Peruvian port of Chancay, with a total length of 5,000 kilometers.],” May 13, 2025.

from Brazil, for example, could take 50 hours travel time from Brazil to immediately get under way at Chancay. The transit time to Panama is longer and comes with an additional 15 day wait at port. But more so than simply replacing Panama, China’s “rail + port” play is set to serve as an entirely new and Chinese-owned and -operated “strategic fulcrum” covering both of Latin America’s coasts.19 All the while, it will also cement China’s capture of key commercial and political pillars in Peru.

Included among the big winners helping to shape this rail line and to bring to life China’s vision for regional dominance is PeruRail. In May 2025, Chinese State-linked media reported on Peru’s efforts to coordinate a tripartite dialogue with China and Brazil to optimize planning for a rail line that would feed Brazilian exports to Chancay.20 Subsequent reporting indicated that the Brazilian Ministry of Transport’s plans for the rail line would be the starting basis for SinoBrazilian deliberations on the plans to “build a railway line that would connect the port of Ilheus, on the Atlantic coast of the state of Bahia, with the so-called Peruvian megaport of Chancay, on the Pacific Ocean.”21 Curiously, it has also emerged that the proposed rail line, which appears to be set to be underwritten by Chinese and Brazilian investment, will transit through Cusco in Peru.22 That routing – which overlaps with PeruRail’s existing lines – will guarantee that the proposed line patching Brazil to Chancay benefits, rather than supplants, PeruRail.

PeruRail was founded in 1999. Its main lines then transited from the port of Matarani, Arequipa, Cusco and Puno on Lake Titicaca and operated as Peru Southern Railway prior to the PeruRail privatization of the line. PeruRail, conveniently, owns the only freight line that patches Peru’s interior and its border territories to the Pacific coastline.23 PeruRail is already captured by Chinese influence: Minmetals, a Chinese State-owned mining giant, owns Minera Las Bambas, a copper mine that counts as a major freight customer for PeruRail.24 It’s no surprise, as a result, that PeruRail appears as a primary character in the piecing together of China’s interests.

Mayor Rafael López Aliaga: PeruRail Co-Founder, Lima Power Broker, and Beijing’s Subnational Ally

It is commonly reported in public sources that PeruRail was founded by two Peruvian entrepreneurs and the British transit company Sea Containers. That origin story features a compelling central figure that often goes unnamed: Rafael López Aliaga. He is credited as a cofounder and major shareholder, alongside Lorenzo Sousa. He is also the current mayor of Lima.

19 Ibid.

20 Zhao Yusha, “Peru seeks meeting with China, Brazil to advance cross-continental railroad,” Global Times, May 27, 2025, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202505/1334943.shtml

21 Alberto Rene Zarate, “Port of Chancay: China will participate in the study of a possible railway between Brazil and Peru,” Asociacion Peruana de Agentes Maritimos, July 7, 2025, https://apam-peru.com/puerto-de-chancay-chinaparticipara-en-estudio-de-posible-ferrocarril-entre-brasil-y-peru/.

22 Pedro Luis Ramos Martinez, “The government disavows the bioceanic railway: ‘Peru has not authorized nor does it plan to invest in it at this time.’,” RPP, July 9, 2025, https://rpp.pe/economia/economia/tren-bioceanico-eduardo-aranasenala-que-el-ejecutivo-no-ha-autorizado-ni-piensa-invertir-en-la-propuesta-noticia-1645631?itlk=iknoticia

23 See, for example, discussion of the rail line’s principal activities at: https://www.ositran.gob.pe/anterior/wpcontent/uploads/2018/04/id-2021-fetransa.pdf

24 “Las Bambas rail transportation agreement signed,” MMG, June 10, 2015, https://www.mmg.com/media-release/lasbambas-rail-transportation-agreement-signed-d16/

And a high-profile, national politician in Peru with standing significant enough to be considered a leading Presidential candidate and to be called a “wanna-be Peruvian MAGA Mayor.25

It is no accident, of course, that this subnational leader happens to have financial interests aligned with China’s. The CCP prioritizes subnational influence like no other global power before. Chinese strategists and diplomats understand the underappreciated value and objective influence that can be secured at local levels.26

The recent Sino-Brazilian negotiations over the Chancay-supporting rail line underscore the degree to which Beijing may be going out of their way to guarantee the support of López Aliaga. Brazil has no explicit interest in tethering the bi-oceanic rail line that will support their export traffic to Cusco. But China, based on its interest in capturing and satiating a high-level Peruvian politician, may well have influenced that routing.

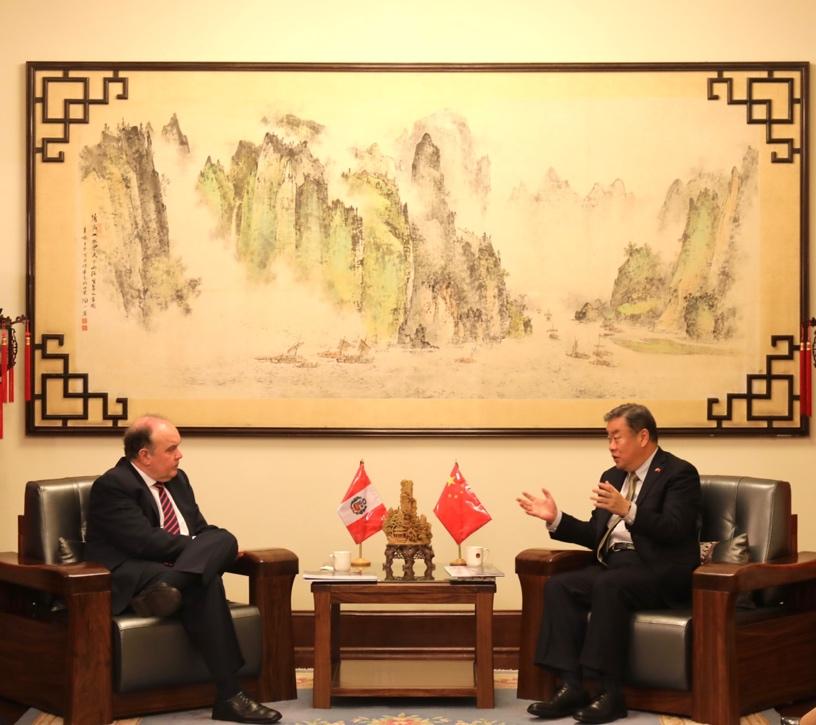

It would track also with the existing beneficial ties between China’s Statebacked enterprises operating in Peru and López Aliaga. PeruRail’s revenues have experienced a boon tied directly to the output of the Chinese owned mine at Minera Las Bambas and López Aliaga has been central in cementing ties between Lima and China. Take, for example, his hosting of the Chinese Ambassador to Peru in February 2023 when López Aliaga declared that Lima under his leadership was “willing to further strengthen friendly ties with China and pursue common development.”27

As is the case writ large, the Chancay strategic corridor demonstrates how Beijing is well on its way to capturing Peru. Securing subnational influence has been an important feature for China since it deliberately looked to expand economic ties over a decade ago. And those subnational ties appear set to figure prominently in Beijing’s approach to locking in gains through these infrastructure megaprojects.

25 Nathan Picarsic, “All Minerals are Local: China’s Man in Lima,” Real Clear Defense, https://www.realcleardefense.com/articles/2025/05/29/all_minerals_are_local_chinas_man_in_lima_1113128.html; Jessica Towhey, “Wanna-Be Peruvian ‘MAGA Mayor’ Gets GOP Blowback in D.C.,” DC Journal, May 6, 2025, https://dcjournal.com/wanna-be-peruvian-maga-mayor-gets-gop-blowback-in-d-c/.

26 Emily de La Bruyere and Nathan Picarsic, All Over the Map: The Chinese Communist Party’s Subnational Interests in the United States, Foundation for Defense of Democracies, November 15, 2021, https://www.fdd.org/analysis/2021/11/15/all-over-the-map/

27 “驻秘鲁大使宋扬拜会秘鲁首都利⻢市市⻓洛佩斯-阿里亚加 [Chinese Ambassador to Peru Song Yang pays a courtesy call on the Mayor of Lima, Peru, Lopez Arriaga],” Embassy of China in Peru, February 22, 2023, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/web/zwbd_673032/wshd_673034/202302/t20230222_11029351.shtml

PRC Ambassador Song Yang and Lima Mayor López Aliaga

“From Shanghai to Chancay”: How China’s Megaprojects

Deliver Regional Influence

As the twin, linked megaprojects of the Chancay port and the bi-oceanic railway make clear, China is not simply looking to seize economic gain in Peru and Brazil. China wants a new strategic corridor that can replace the Panama Canal. And they want that critical infrastructure to be able to lock in generational influence across Latin America. The port at Chancay is well on its way; the linked bi-oceanic railway megaproject is following along quickly.

Prior to Chancay’s development, Peru lacked a major deepwater port. Despite its strategic location, Peruvian exports to Asia largely depended on transit to and shipment from Brazil’s Atlantic ports in addition to the major hubs of Mexico and Panama. Chancay will change this –and in a way that is likely vastly to increased China’s economic influence in Peru and throughout the region

In November 2024, the heads of state of both China and Peru officially opened the Port of Chancay. The port’s launch immediately reduced shipment times from Peru to China – what once took 40 days or longer now takes only 23 days. The port has also already delivered a 20 percent savings in overall logistics costs for shipments transiting between China and Peru.

For producers in Peru’s strategic sectors – including those that build on healthy domestic reserves of copper, zinc, and silver, as well as robust agriculture and fishing sectors – this offers the hope of easy access to the Chinese market, with it of economic growth. That type of ready market access is no small matter. To date, despite Peru’s amble natural resources, local

producers have faced an uphill climb. The Andes mountains pose a natural barrier; Peru’s lagging infrastructure and technological base further compound the challenge.

All of those obstacles constitute opportunity for China. Beijing sees a chance to capture overseas market and geopolitical position. And Beijing does so – in Peru and in other countries like it through infrastructure development that is near universally embraced at the local level. The port at Chancay and the bi-oceanic railway feeding it deliver two prime examples of China’s megaproject playbook.

So far in 2025, Chancay has managed “stable operations” on its three trunk routes and three feeder routes, which collectively have handled over 117,000 TEUs in the first half of the year.28 That has delivered rapid growth in exports to China of Peru’s agricultural mainstays, like avocados and blueberries, as well as those from the fisheries sector. For example, Peru has risen to be the world's largest exporter of fishmeal and Chancay shipping routes are guaranteeing that Peru is and will long remain China's largest source of imported fishmeal.29 In aggregate, projections indicate that Chancay will contribute 4.5 billion in annual revenue for Peru and influence the hiring of over 8,000 jobs.30

But the implications of the port and its positioning extend well beyond the Peruvian export market and Sino-Peruvian trade. China describes the port as an “Inca Trail of the New Era” and as a step toward Peru’s vision of being “Latin America’s Singapore.”31 And its impact locks in Beijing’s influence –over not only Peru, but also the broader region.

The Port of Chancay serves South American countries including Brazil, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, Bolivia, and Argentina, potentially transforming the region's economic and trade landscape. Chinese State media describe the ambition for Chancay to be established as a “threedimensional, diversified, and efficient network of connectivity from the coast to the interior,

28 “新思想引领新征程丨坚定不移推进高水平开放 与世界共享新机遇 [New ideas lead a new journey丨 Unswervingly promote high-level opening up and share new opportunities with the world],” CCTV News, August 25, 2025.

29 “秘鲁农业与灌溉部部长:一提亚洲美国就生气,中国帮忙造的钱凯港帮了大忙 [Peruvian Minister of Agriculture and Irrigation: The US gets angry when Asia is mentioned, but China's help in building the Chancay Port has been a great help.],” Observer, August 19, 2025.

30 “中秘友谊源远流长,经贸关系迈上新台阶 [China-Peru friendship has a long history, and economic and trade relations have reached a new level],” China Daily, November 19, 2024.

31 “中秘友谊源远流长,经贸关系迈上新台阶 [China-Peru friendship has a long history, and economic and trade relations have reached a new level],” China Daily, November 19, 2024.

and from Peru to other Latin American and Caribbean countries.”32

In short, China wants Latin America to become dependent on it – for trade, for investment, for its capacity to operate the software and hardware that permit trade and investment. Chancay is a step in that direction.

Cooperation in the project on the part of other elements of the Chinese State and State-backed apparatus further underscore Beijing’s ambitions – and risk solidifying dependence. For example, in August 2025, the Shandong provincial government and Shandong port companies visited Peru. That visit saw the signing of strategic partnerships, including between Shandong’s Qingdao Port and Chancay.

Shandong-Chancay Cooperation Agreement Signing, August 2025

That tie up will help improve the production and management capabilities of the Chancay Port Terminal, including by enhancing “cooperation in the application of automated terminal technology and employee skills and quality training” and building a “more convenient international logistics channel for the economic and trade development of China and Peru.”33 And this was no empty rhetoric.

As of August 2025, there are now six direct container routes from Qingdao Port in Shandong Province to Peru, with one new route added just before the opening of the Port of Chancay. Over the course of the 2024 calendar year, Qingdao Port handled 96,000 TEUs of heavy containers between China and Peru and in the first half of 2025 those figures saw over 20 percent growth from the year prior.

Ties of this nature underscore the depth of China’s embrace of Peru. Beijing is not simply underwriting the flow of one-time capital expenditure or even the erection of static infrastructures. Rather, China is capturing the local ecosystem. Beijing is ensuring that the national market depends on exports to China; that the national logistics system depends on and connects to Chinese systems; and that national infrastructure is operated and owned by Chinese agents.

32 Ibid.

33 “山东港口青岛港与秘鲁钱凯港,签署合作协议 [Shandong Port Qingdao Port and Peru's Chancay Port signed a cooperation agreement],” China Shipping Weekly, August 12, 2025.

In addition to these business and financial interests, China is also deploying its social and cultural assets to Peru to further cement ties locally. Take, for example, a recent Shanghai Jiao Tong university visit to Chancay. That visit built on a May 2025 “framework cooperation agreement” signed between the School of Naval Architecture, Ocean Engineering, and Civil Engineering of Shanghai Jiao Tong University and COSCO SHIPPING Ports Peru. The university and COSCO’s Peruvian subsidiary are meant to establish in-depth collaboration in port construction and technology management that can serve as a “benchmark for the integration of industry, academia, and research along the Belt and Road.”34

[Shanghai Jiao Tong University students and teachers moved their ideological and political classes to Qiankai Port],” China Youth Daily, August 18, 2025.

SJU Delegates visiting Chancay Port Remote Terminal Operations

Students and teachers from the Shanghai university visited in August 2025 and had the chance to liaise with local operators and communities. Their interactions included visits to the port’s terminal operations as well as dialogues with local Peruvian universities. Exchanges like this present as innocuous educational and cultural dialogues. But they bleed into a front for subnational influence: Shanghai Jiao Tong’s ideological and political views are likely to be reflected in the research agendas, discourse, and ambitions of partner universities and individuals in Peru.35

Risk Channels and Actors

The strategic risk that Chancay poses is reflected in the overarching dependency that it induces for Peru. Beijing claims that the outcome will be a “win-win” one for both Peru and China. But that mutual benefit will last only until such time as it is stops being in China’s interests. And in the long term, co-option on the part of Chinese interests will negatively affect Peru’s domestic economy and security prospects.

This might seem a quick leap from the immediate economic boons that the Chancay project –and China’s presence more generally – offer Peru. But the story has played out time and time again. It is the same scenario that took place with Sri Lanka’s port cities at Colombo and Hambantota, and the same one that is currently unraveling with the Panama Canal.36 Those are grand strategic risks of economic and security capture. Chancay offers China a

35 “跨越太平洋的握手,中秘高校共探“ 带一路”绿色港航新篇章 [Across the Pacific, Chinese and Peruvian universities jointly explore a new chapter in the Belt and Road Initiative's green shipping sector.],” Eastday, August 25, 2025.

36 Asanga Abeyagoonasekera, “How China won over local agency to shackle Sri Lanka using a port city,” ORF Online: Raisina Debates, June 22, 2021, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/how-china-won-over-local-agency-to-shacklesri-lanka-using-a-port-city

gateway to Latin America. The economic influence likely to follow is the stuff of colonial mercantilism.

Perhaps just as concerning for both US and local interests are the operational harms presented by a Chinese owned and operated mega port in Peru. This is a “smart port” with largely remote operational controls. And the Chinese firms operating and managing the project have close ties not only to the Chinese government but also to the Chinese militry-civil fusion system. That should be a concern on the ground, just as it should be one for American commercial and military interests.

Chinese controlled ports can be placed at risk for disruption and manipulation; Beijing can monitor their transit data and patterns to claim an unparalleled operating picture. And Beijing can undermine the ability to properly execute customs and security monitoring to protect against, for example, terrorist attacks or illicit proliferation.

Those risks owe to the degree of State ownership and influence that Beijing enjoys among its overseas port developers and operators as well as the Chinese State’s strategy of military-civil fusion. China’s unique theory for power projection assumes that seemily commercial or civilian assets play a vital role. And ports like Chancay can provide a significant return on that dimension – from right in the backyard of the United States.

The cast of characters leading Chinese efforts at Chancay includes several entities explicitly designated by US authorities as security risks.

For example, COSCO, the conglomerate that led Chancay investment and development for Beijing, has had several of its subordinate entities included on the US Department of Defense’s Communist Chinese Military Company list.37 The Port of Chancay’s construction was undertaken by a joint venture between China Harbour Engineering Company (CHEC) and China Communications Construction Fourth Engineering Bureau, a subsidiary of China Communications Construction Company (CCCC).38 Those are the same actors who spearheaded other overseas Chinese megaprojects, like China’s Sri Lankan gambit. And CCCC was placed on the US Commerce Department’s Entity List in December 2020 for “engaging in activities contrary to US national security interests.”39 ZPMC, itself a subsidiary of CCCC, has not been designated under those same authorities. But its ties to the Chinese Communist Party, nonmarket economic backing from the Chinese State, and security risks have been profiled in US Congressional scrutiny.40

37 “Entities Identified as Chinese Military Companies,” Department of Defense, January 7, 2025, https://media.defense.gov/2025/Jan/07/2003625471/-1/-1/1/ENTITIES-IDENTIFIED-AS-CHINESE-MILITARYCOMPANIES-OPERATING-IN-THE-UNITED-STATES.PDF

38 “打造

[CCCC Fourth Engineering Bureau paints a new picture of green development by creating a benchmark environmental project],” China Transportation News Network, August 25, 2025.

39 “Entity List Fact Sheet,” US Embassy Colombo, https://lk.usembassy.gov/entities-list-fact-sheet/.

40 See, for example, “Handling Our Cargo: How the People’s Republic of China Invests Strategically in the US Maritime Industry,” Majority Staff Report: House Homeland Security Republicans and House Select Committee on Strategic Competition with the Chinese Communist Party,” September 2024, https://selectcommitteeontheccp.house.gov/sites/evo-subsites/selectcommitteeontheccp.house.gov/files/evo-mediadocument/Joint%20Homeland-China%20Select%20Port%20Security%20Report-compressed.pdf

Conclusion: Panama Canal 2.0 at a Crossroads

The United States needs to learn from the Panama Canal example. China is running its trusted playbook to capture political elites, business interests, and keystone insfrastructure megaprojects in Peru today.41 China’s Peruvian gambit stands to keep it multiple steps ahead of the United States in the hemispheric and global competition for economic gains and strategic influence. That is made clear by the infrastructure megaprojects, but also by the elites that are captive of and actively championing Chinese interests across Latin America.

The challenge of Chinese influence in Peru is made urgent by the tipping point moment presented by the Port of Chancay and the proposed Sino-Brazilian rail line that will feed it. This infrastructure suite is set to replace the Panama Canal as a vibrant mega port on Peru’s Pacific coast that can network a broad swathe of Beijing’s bets in Lain America. This effort is not notional. The port project is already operating. It has cut in half the transit time for goods to move between China and Peru. Meanwhile, China has seemingly strong-armed Brazil into its routing of the proposed rail line to guarantee that it further cements Beijing’s subnational influence in Peru. Together, this package promises to accelerate steadily growing ties between China and Peru. And the strategic reality is that the port and rail line are set to deliver a regional beachhead from which China will be able to solidify its influence over a range of critical infrastructures and trade routes across Latin America.

The story of Chancay and of the Sino-Brazilian rail line will serve as landmark examples of China’s ability to lock in gains in strategic locales with minimal or non-existent competition –and to do so with the “United Front” of local political and business leaders championing their cause. These megaprojects are China’s approach to power projection and part and parcel of their bid to pose risks to the United States in the Western hemisphere. And they are at a tipping point.

Now is the time for the United States to compete – before it is too late.

Competing though is not as simple as blocking or replacing projects like Chancay – as necessary and urgent a mission as that is. China is deploying its broader financial, commercial, and cultural assets to lock in economic and political influence. Chancay, again, demonstrates this neatly. The port boasts of strategic partnerships and cooperation with a wide-ranging set of actors. Those include State-backed port operators and equipment makers like COSCO, CCCC, and ZPMC – all of which have been designated by either the US Department of Defense or the US Commerce Department as actors supporting China’s military-civil fusion apparatus and posing risks to US counterparties. Those designated bad actors make up the team bringing Chancay to life and managing its operations. And China’s social, cultural, and political embrace of Peru helps it to capture elites and activate subnational influence to squash any potential push back at the local level.

China’s approach should not be a surprise. Beijing frames the entire project at Chancay as part of the global Belt and Road Initiative. That should make clear the project’s intent. It is meant to

41 See, for example: Peter Pinedo, “Meet ‘China’s man in Lima’ who jetted over to US to collect trains donated by Biden admin,” Fox News, July 12, 2025, https://www.foxnews.com/politics/chinas-man-lima-jets-over-us-collecttrains-donated-biden-admin

serve the Chinese Communist Party in its pursuit of international presence that provides economic returns to the Chinese actors involved on the ground – and, above all else, strategic influence over the long-term for Beijing’s rulers. And that effort is aimed not simply at capturing Peru. Rather, the ambition in Chancay – and broader Chinese influence in Peru – is to lock in regional gains; to make dependent on China the high-growth and strategic resources that Latin America has at its disposal. The rail line running from Brazil to Chancay is central to this effort. The United States should recognize the strategic stakes of this proposal and its implications for Chancay and the direction of Peru. Combatting the proposed rail line offers an avenue to send a signal to Peru’s leadership and to the region. It also offers a chance to impose costs on China’s efforts to network the entire region in its favor. And the Panama Canal example demonstrates the costs of inaction.

At present, Beijing is positioned to run roughshod over Peru’s economy and threaten the US vision of hemispheric security. Chancay is a first step to be followed swiftly by a rail line that locks in Chinese influence and control for a generation. China controlling Peru’s transit hubs will be bad in the long run for all involved – save for the Chinese Communist Party. Allowing it to happen is tantamount to strategic malpractice that will permit risk to foment right in America’s backyard.