Risk and Harm Typology

Psychedelic Risk and Harms Typology

Summary

Contents

Contents

Psychedelic Risk and Harms Typology Introduction

Glossary of Key Terms

The Challenge of Pinpointing Harms

Ethical Considerations in Evaluating “Harm”

The Landscape of Psychedelic Experiences

Risk Factors Typology

Risk Factors Typology

Harms Typology:

Harm Domain Definitions

Harms

References

Psychedelic Risk and Harms Typology

Introduction

Purpose

This document aims to establish a foundational framework for understanding and categorizing adverse experiences and risks associated with psychedelic use. Rather than attempting to enumerate every possible negative outcome, our goal is to develop an evidence-based typology that captures the broad categories and characteristics of challenging psychedelic experiences.

This framework serves multiple purposes:

1 To provide an overview of the nuanced and often paradoxical landscape of psychedelic experiences, where a burry line often exists between benefit and harm and seemingly negative experiences may sometimes lead to positive outcomes

2. In the context of psychedelic use, “harm” refers to any outcome that leaves an individual worse off or significantly impairs their judgment compared to their state before the psychedelic experience

3. To leverage that definition into a common lexicon for facilitating nuanced discussions about psychedelic public health and safety at the Psychedelic Safety Summit and in broader conversations within the field

This typology is intended to serve as a starting point rather than a definitive classification system We hope it provides the foundation for further research and investigation into psychedelic risks and adverse events, and more comprehensive frameworks for categorizing and understanding psychedelic adverse events and challenging experiences

Scope

This typology is based on insights from over 700 studies on psychedelic public health and safety. While it provides a foundation for categorizing psychedelic harms, further focused research is necessary to refine and expand this classification system The field of psychedelic science is still emerging, with many unknowns remaining Our aim is not to present a perfect framework but rather one that is practical enough to foster meaningful discussions and support efforts to reduce harms

This document is designed to enhance safety by promoting dialogue around these critical issues We acknowledge that various perspectives exist on how these harms should be classified As the Psychedelic Safety Institute, we do not position ourselves as a research body but as a facilitator of practical solutions for harm reduction, and we see the development of a common lexicon for psychedelic harm education as critical to all harm reduction efforts

We encourage the research community to engage with and provide feedback on this work, with the hope that it will support and inform ongoing research efforts We hope that this typology may be interoperable with future classification systems, to support a more folsom understanding of psychedelic adverse events and adverse event data

Glossary of Key Terms

● Risk Factors: Psychedelic risk factors are individual, contextual, and pharmacological conditions that increase the chance of adverse outcomes before, during, or after using psychedelics (Krebs & Johansen, 2013; Durante, 2020). These risk factors change based on the situation and come from many sources: the substance itself, the person's mental state, their surroundings, and social factors, and legal/policy factors related to drug laws Having risks doesn't mean something bad will definitely happen - it just

makes harms more likely To better assess individual risk factors related to mindset and psychological readiness, researchers have developed the Psychedelic Preparedness Scale and the Psychedelic Predictor Scale (McAlpine et al , 2024; Angyus et al , 2024) These tools help evaluate whether a participant's mental state, expectations, and coping strategies may reduce or increase their vulnerability to harm during a psychedelic experience, providing insight into their likelihood of having a safe and constructive journey.

● Adverse Events: In clinical and research contexts, an adverse event is any unintended or harmful experience that occurs during or after the administration of a substance, regardless of whether it is caused by that substance (Palitsky et al., 2024). In the case of psychedelic substances, adverse events can include physical symptoms (such as nausea or elevated heart rate) and psychological or emotional distress (such as acute anxiety or paranoia). Adverse events range from mild and transient (e.g. brief dizziness) to serious (e g a panic episode requiring medical intervention), and capturing all such events is a key part of clinical trial safety reporting. Importantly, these events may occur even within an otherwise beneficial or positive psychedelic experience (Palitsky et al , 2024; Carbonaro et al , 2016) For example, a participant might experience temporary nausea during a psilocybin session yet still report an overall therapeutic benefit from the session as a whole

● Psychedelic Harms are unexpected, unfavorable, or potentially dangerous outcomes of psychedelic use that result in lasting negative consequences, leaving individuals worse off than before They may surface immediately during the psychedelic experience or develop over time following the psychedelic experience, ranging from acute medical complications to persistent psychological or social difficulties. Indicators of harm include impaired daily functioning, deteriorating relationships, reduced quality of life, and enduring mental health issues. Unlike challenging but transient experiences, harms are longer-lasting, significantly disrupt everyday life, and do not offer meaningful benefits The Persisting Effects Questionnaire (PEQ) systematically evaluates long-term psychological and behavioral changes, including sustained negative outcomes, months after the experience (Griffiths et al , 2011) Additionally, changes in clinical measures of PTSD (e g , CAPS-5), depression (e g , QIDS, BDI), and anxiety (e g , STAI) can indicate lasting psychological distress following psychedelic use, particularly when scores worsen over time rather than improve Additionally, conditions such as Hallucinogen Persisting Perception Disorder (HPPD) are evaluated through structured psychiatric interviews and medical assessments, including ophthalmological and neurological examinations, to rule out other potential causes of persistent visual disturbances. These tools provide a way to assess whether a psychedelic experience has led to persistent harm rather than transient difficulty or growth

● Challenging Experiences are intense emotional, psychological, or physical sensations often including anxiety, fear, or discomfort that arise during or shortly after psychedelic use (Carbonaro et al , 2016) Sometimes called “bad trips,” they can persist for days or weeks beyond the acute effects Although these experiences can be distressing, they typically do not result in lasting problems unless they continue longer than expected, disrupt daily life, or lead to ongoing mental health issues Challenging

experiences may result in harm or may result in ultimate benefit These experiences are commonly assessed using validated measures such as the Challenging Experience Questionnaire (CEQ) (Barrett et al , 2016) and subscales from the 5-Dimensional Altered States of Consciousness scale (5D-ASC) (Studerus et al., 2010), which quantify distressing psychological and physical reactions.

● Extended Difficulties are adverse experiences that continue after the immediate effects of a psychedelic have worn off, sometimes persisting for weeks (Evans et al., 2023). They can involve prolonged emotional or psychological distress, ongoing trouble integrating the experience, or difficulty with daily functioning Often marked by lasting changes in perception, unstable emotions, or chronic stress, these challenges go beyond a typical adjustment period by interfering significantly with everyday life

● Functional Impairment: Functional impairment is a noticeable decline in a person’s ability to handle everyday tasks and responsibilities including work, communication, relationships, self-care, and clear thinking compared to their usual level of functioning prior to the psychedelic experience (Simonsson et al., 2023; Evans et al., 2023). Functional impairment may persist for weeks or longer following the psychedelic experiences

● Spiritual Emergency / Spiritual Emergence: refers to a spectrum of deep personal transformation that disrupts normal life functioning At one end, spiritual emergence is a challenging but ultimately growth-oriented process, creating temporary life disruptions but culminating in positive change. At the other, spiritual emergency involves an overwhelming experience that severely impacts daily functioning and may necessitate professional intervention (Grof & Grof, 2017) Both feature altered mental states and shifts in worldview, but the key distinction lies in whether individuals can manage daily responsibilities or require external support These terms are often used to understand and interpret post-psychedelic difficulties.

The Challenge of Pinpointing Harms

Ethical Considerations in Evaluating “Harm”

1. Risk of Pathologizing Growth

● Psychedelic Challenges May be a Catalyst for Growth: Challenging experiences whether acute or extended during or after psychedelic use can lead to deeper self-understanding and personal transformation (Bremler et al., 2023; Gashi et al , 2021; Carbonaro et al , 2016) However, this outcome is not guaranteed and often depends on having the right support systems, tools, and integration practices in place (Simonsson et al., 2023; Evans et al., 2023). What fosters growth for one person may not yield the same benefits for another

● Discomfort May be Beneficial: Distressing experiences can be integral to healing, and seeking to eliminate all risks or difficulties may undermine potential benefits Some

discomfort can be constructive, fostering deeper understanding and growth; however, there is a crucial distinction between beneficial discomfort and overwhelming distress that causes harm (Carbonaro et al , 2016) Recognizing this difference and having the support and tools to navigate it is important to achieving positive outcomes (Evans et al., 2023).

2. Risk of Bypassing Genuine Harm

● Bypassing or Overlooking Real Harm: While some difficulties can indeed be part of a healing process, it is crucial not to dismiss genuine harm by labeling every challenge as “just part of healing ” Doing so can minimize or invalidate real harm that requires acknowledgment and support (Palitsky et al., 2024). A practitioner's own positive beliefs about psychedelics' healing potential could lead them to downplay potential harms or interpret challenging events as ultimately beneficial, even if the client experiences significant distress (Rosenbaum et al., 2024). Watch for warning signs indicating that a situation has moved beyond a normal challenge, such as persistent disruption of daily activities, severe emotional distress, or the need for professional intervention.

● Power Imbalances can Mask Harms: When real harm is minimized or dismissed in contexts where facilitators wield significant power or influence, participants who may be in a highly suggestive state may be encouraged to see their difficulties as mere personal challenges or part of the healing process (Evans & Adams, 2025) This is especially concerning if coercive or abusive facilitation is at play, as people may ignore or downplay negative experiences out of misplaced trust. To protect participants, it is crucial to have external support systems and clear mechanisms for reporting and addressing potential harm

3. Interpretation of Psychedelic Experiences May Influence Harm

● Influence of Interpretation and Meaning Making: How a psychedelic experience is understood and interpreted by cultural and social contexts, peers, cultural frameworks, psychedelic practitioners, integration coaches, and other support networks can significantly shape an individual’s experience of harm or benefit (Gashi et al , 2021; Zeller, 2024). The ways in which someone makes sense of their experience, influenced by spiritual, psychological, or cultural perspectives, can lead to very different outcomes

● Balancing Personal Views with Safety: It is important to honor each person’s right to interpret their own psychedelic experiences while still providing support and resources for those who may feel harmed or struggle afterward (Dupuis & Veissière, 2022) At the same time, we must acknowledge that people may be susceptible to problematic or distorted interpretations, especially in settings such as controlling groups or in the presence of severe mental health challenges (Timmerman et al , 2022) Support should therefore respect individual perspectives while remaining vigilant for signs of harm, ensuring that those who need help receive it

4. Temporal Dimension of Interpreting Psychedelic Experiences

● Determining Harm or Benefit May Take Time: Participants may experience challenging experiences that may last moments, months, or even years and interpret the experience in varying ways through this period The ultimate harm or benefit of the experience may only become clear in an undetermined period of time (Palitsky et al., 2024)

● Interpretation of the Psychedelic Experience May Change: A period initially viewed as harmful may later be seen as beneficial once integration has occurred and perspective has shifted - and vice versa (Carbonaro et al, 2016) While it's normal for views to change, it's important to provide support for immediate care of immediate problems as they happen, even if someone might later see them differently.

The Landscape of Psychedelic Experiences

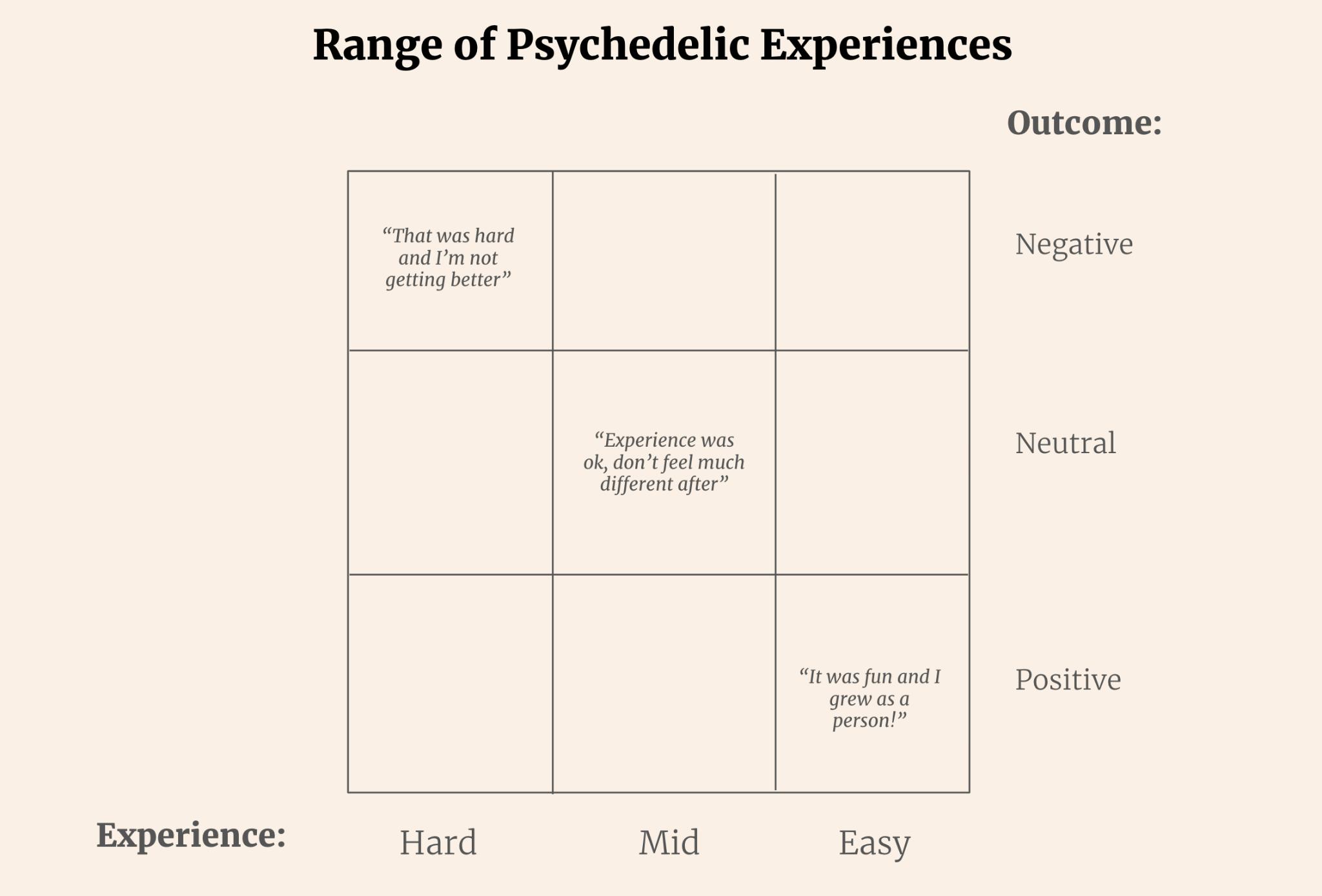

Psychedelic experiences often involve challenging or adverse elements, making it difficult to determine when a difficulty is truly harmful. For example, in research on ayahuasca, vomiting is commonly classified as an adverse effect; however, many practitioners and participants often view vomiting as an unpleasant experience integral to the healing process. Similarly, transient acute fear during a psychedelic session, when managed with appropriate therapeutic guidance, may catalyze beneficial psychological processing rather than constitute lasting harm.

The Challenge of Identifying Harms

This complexity highlights the challenge of distinguishing between experiences that are merely unwanted and those that are genuinely harmful Some transient adverse effects, such as mild nausea lasting only an hour after ingesting psilocybin mushrooms, may not necessarily

constitute harm In contrast, nausea that persists for weeks and results in considerable functional impairment could reasonably be deemed harmful.

One heuristic is to assess both the degree (or intensity) and duration of an unwanted experience. An experience remains tolerable if it is mild and short-lived; it may become harmful if it intensifies or endures beyond a brief period Hence, understanding the balance between these factors—how intense unwanted an experience is and how long it persists—can help determine when an adverse effect crosses the threshold into harm

Limitations and Alternatives

The degree / duration framework for identifying harms has inherent limitations due to the wide variance in subjective experiences and interpretations Some individuals may endure extremely challenging experiences that persist for an extended period but, upon later integration, may retrospectively perceive these experiences as beneficial despite initial adverse effects.. Conversely, others may encounter mild and brief adverse effects that, due to personal or contextual factors, are perceived as harmful—underscoring the need for objective evaluation alongside subjective reports.

This variability suggests that it may be helpful to introduce a third axis in the assessment framework one that accounts for the degree, duration, and interpretation of experiences. However, while this added complexity could enhance the precision of harm evaluation, it is crucial not to let intellectual nuance obscure the fundamental goal: to intuitively and clearly understand which types of experiences we should prevent or mitigate in public health and harm reduction efforts

Risk Factors Typology

We categorize risk factors into substance, set, and setting due to the widespread use of this framework in both research and public discourse. Despite its popularity, the terms “set” and “setting” are often vague and carry assumed meanings without clear definitions This can lead to confusion or misinterpretation However, we opted for this approach because of its simplicity and familiarity, allowing us to align with established terminology rather than challenging or redefining existing concepts Definitions of these terms for the purposes of this typology are proposed below.

Risks factors can also be categorized based on their temporal dimension: before, during, and after the psychedelic experience. However, if using the set, setting, and substance framework, it’s important to recognize that risk factors within each of these categories can arise at any stage of the experience For example, risk factors related to “set” (mindset) might involve pre-existing mental health issues before the experience, heightened suggestibility during the experience, or difficulty with integration afterward Similarly, risks in “setting” or “substance” can manifest at various points in time This multidimensional approach helps provide a more comprehensive understanding of potential risks.

In general, these domains are defined as:

● Substance: Risk factors inherent to the psychedelic itself, independent of the person or environment.

● Set: Risk factors related to the unique individual’s mindset, psychological state, neurobiology, sex, age, and personal characteristics that interact with the substance.

● Setting: Risk factors arising from the interaction between the substance, the individual, and the interaction with the physical, social, and cultural environment in which the psychedelic is used, including relational dynamics and environmental conditions.

Risk Factors Typology

● Substance:

○ Dose: Higher doses often typically carry greater risk

○ Quality, Purity, and Sourcing:

■ Contamination: The substance may be tainted with harmful chemicals or adulterants.

● Set:

■ Potency: Even with a “pure” substance, varying or unknown potency can lead to unexpectedly intense effects.

■ Mislabeled substances: Examples include NBOMe sold as LSD, which carries different (and often higher) risks.

■ Extraction or Synthesis Method: Some extraction processes introduce residual solvents or by-products

○ Route of Administration:

■ Pharmacokinetics & Pharmacodynamics: The route of administration affects both pharmacokinetics (how the body absorbs, metabolizes, and eliminates the substance) and pharmacodynamics (the intensity and nature of the experience). Specifically, the onset, duration, and intensity of the experience can vary widely by route (oral, insufflation, rectal, inhalation, intravenous, etc.). For example, inhalation and IV administration lead to sharp, intense peaks with short durations (e.g., 5-30 minutes), increasing the risk of overload and anxious ego dissolution, especially for first-time users or those with anxiety disorders.

■ Physical Risks: Irritation or damage to nasal passages, lungs, etc.

○ Intrinsic Mechanisms:

■ Risk of Serotonin Toxicity: Psychedelics vary in their mechanisms of action, leading to different risks of serotonin toxicity Some, like ayahuasca, contain MAOIs that inhibit serotonin breakdown, raising serotonin levels and increasing the risk of serotonin toxicity when combined with SSRIs, SNRIs, or other MAOIs. Others, like MDMA, increase serotonin release and carry higher risks when combined with MAOIs. Meanwhile, LSD and psilocybin primarily activate serotonin receptors and carry lower risks, while ketamine has minimal serotonergic activity Therefore, the risk of serotonin toxicity depends on both the specific psychedelic and any other psychoactive substances used in combination.

■ Neuroplastic Changes: Psychedelics can induce short- and long-term shifts in brain function and connectivity, which may facilitate new learning, emotional flexibility, and shifts in perspective. These psychoplastogenic effects can be therapeutically beneficial or risky, depending on the context and integration of the experience. When combined with negative or harmful experiences, they can lead to long-lasting psychological difficulties. Evidence suggests that psychedelics vary in how strongly they induce neuroplasticity, leading to different levels of risk. Additionally, psychological, social, and environmental influences–such as suggestibility, vulnerability, and “epistemic agency”--interact with these neuroplastic changes, shaping how experiences are internalized. The risk of long-term impact depends not only on the degree of neuroplasticity but also on contextual factors during and after the psychedelic experience.

○ Physiological Risk Factors: Drug interactions and comorbid medical conditions can turn a seemingly “low” risk scenario into a high-risk one.

■ Drug Interactions: Combining psychedelics with certain medications (e.g., SSRIs, MAOIs, other psychoactive substances) can introduce unexpected

effects or dangers. These interactions are influenced by how substances affect serotonin levels, neurotransmitter systems, and metabolic pathways, and the risk level will vary depending on the particular combination.

■ Polysubstance Use: Using multiple substances at once can amplify risks (e g , mixing a psychedelic with alcohol or stimulants)

■ Physiological Condition:

● Existing medical conditions: Heart problems, liver issues, etc.

● Genetic predispositions: Certain genotypes may heighten risk of psychotic breaks or metabolism-related issues.

● Physical health: Overall fitness or any acute illness.

● Metabolic / Enzymatic Factors: Some individuals have unique enzyme variants (e.g., CYP450 differences) that alter how they metabolize psychedelics or interact with other medications.

○ Psychological Risk Factors:

■ Individual Sensitivity: Some people are more sensitive to psychedelics and may experience stronger effects at lower doses.

■ Individual Mental Health:

● Mental health History: History of bipolar disorder, suicidality, anxiety, depression, etc. can significantly influence how one responds to psychedelics.

● Trauma History: Preexisting trauma can resurface during psychedelic states creating unique risks.

○ Type and Degree of Trauma: Combat-related, childhood abuse, sexual trauma, carry varying risk profiles

○ Trauma Support: Whether a person is already receiving support for their trauma

■ Personality: Traits like openness to experience, growth mindset vs high anxiety or rigidity, attachment style, and coping style can shape the psychedelic experience.

■ Emotional State: Acute stress, grief, major life transitions, or emotional instability before, during, and after the experience can color the outcome

■ Self-Awareness & Emotional Regulation: A person’s capacity to manage intense emotions and experiences may affect outcome

■ Worldview and Beliefs: The degree to which a psychedelic experience conflicts with a participant’s worldview and beliefs introduces risk. Individuals with rigid belief systems or those unprepared for intense metaphysical experiences.

○ Approach

■ Use Patterns:

● Single / Occasional Use vs. Repeated Dosing: One large-dose experience differs from repeated dosing or microdosing in terms of risks (tolerance, potential for persistent changes, etc.).

● Acute vs. Chronic Use: Long-term patterns of repeated psychedelic use may have different physiological or psychological implications.

● Setting:

■ Substance Familiarity: How familiar someone is and the degree of their experience with the given substance.

■ Psychedelic Education: How much someone knows about psychedelics and psychedelic harm reduction effects likelihood of negative outcomes

■ Intention: Why a person is taking psychedelics (e g , “to get high” vs for “therapeutic healing”) affects risk profiles Trying to “break through” or accelerate healing may additionally increase risk.

■ Preparation: Degree to which the participant has followed preparation principles (diet, mindset work, guidance, etc.).

■ Integration: Degree to which the participant has followed integration principles, has access to integration support, and the quality of integration support they receive.

○ Physical Setting:

■ Location Type: Whether an experience happens at a clinic, therapeutic office, home, festival, wilderness, presents distinct risk profiles

■ Familiarity with Setting: Settings that are unfamiliar may increase risk

■ Immediate Safety Hazards: Differences in immediate safety (trip hazards, controlling noise/light, possibility of medical intervention)

■ Sensory Environment: Lighting, temperature, sound/music design, can affect outcomes

■ Familiarity of Environment: The familiarity of the environment can influence the sense of ease or stress a participant experiences

■ Emergency Preparedness: Access to medical care, first aid, phone or radio, and other forms of help can affect outcomes in crisis.

■ Unforeseen Interruptions or Intrusions: Unexpected disturbances (e g , people entering the space unannounced or sudden external events) can disrupt the experience and introduce additional risks.

○ Relational Setting: Risk factors derived from interaction with people during experience

■ Practitioner-Related Risks:

● Practitioner Behavior and Misconduct: How a facilitator or guide interacts with the participant can create adverse outcomes (i.e abuse, guruism, fraud, etc - see Misconduct Typology)

● Facilitator / Sitter Training: Degree of experience and skill of practitioner introduces risk

● Familiarity with Practitioner: the participants familiarity with the practitioner, especially if they are unfamiliar with the practitioner's style, tradition, or approach, may increase risk

■ Interpersonal Behavior: i e peer bullying during a psychedelic experience, cultic environments, the presence or absence of support systems, etc.

○ Contextual Environment

■ Cultural Factors: Cultural context before, during, and after the experience can shape whether the user feels supported, shamed, or misunderstood Family, religious beliefs, or social stigma around psychedelics may increase psychological stress and the experience of isolation A mismatch between the participant’s prior worldview and the worldview of the setting (e g , spiritual or therapeutic frameworks) can lead to cognitive dissonance, confusion, or existential distress. This is especially relevant when participants encounter belief systems that contradict their personal values or challenge their cultural identity

■ Social Support and Stability: The quality of home life, social support, and life stability (e g , having a job, stable housing, or reliable relationships) significantly impact emotional integration and post-experience well-being.

■ Legal Status: Legal risks and enforcement contexts can influence whether a person seeks help if needed, or tries to hide use.

■ Economic / Accessibility Factors: Cost of safe/regulated substances or therapeutic services can push individuals toward dangerous sources or settings.

■ Equity-Related Factors: Difficulty accessing culturally informed care and the legacy of the war on drugs introduces unique risk factors for some demographics. Systemic inequities may compound these risks.

Harms Typology:

Limitations

This typology aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the potential harms associated with psychedelic use, organized by distinct domains However, several limitations should be acknowledged:

● Non-Exhaustive Scope: While extensive, this typology does not cover all possible harms or rare adverse events associated with every psychedelic substance. Emerging compounds and novel psychoactive substances are not included due to limited research data

● Context-Dependent Harms: The nature and severity of harms can vary significantly based on context, including dose, frequency, setting, and individual predispositions This typology does not account for all contextual variables that influence risk

● Underreporting and Bias: Due to the stigmatized and often illegal nature of psychedelic use, adverse events may be underreported, leading to potential bias in the available data.

● Causality and Correlation: Many harms are reported anecdotally or in case studies, making it difficult to establish causal links, and some harms may be influenced by poly-drug use or underlying health conditions.

● Cultural and Social Contexts: This typology does not explore cultural or social contexts that influence harm, such as traditional or ceremonial psychedelic use, which may carry different risk profiles and protective factors

● Harm Reduction Considerations: This typology does not explicitly address prevention or mitigation strategies, which will require a separate, context-specific framework

Scope

This typology categorizes the potential harms associated with psychedelic use into distinct domains, ranging from physical to relational and spiritual harms It includes:

● Acute and Chronic Harms: Both short-term and long-term effects are considered, including transient adverse events and lasting psychological, physical, or social consequences.

● Substance-Specific and Generalized Risks: While many harms are substance-specific, others are generalized across multiple psychedelic compounds This typology attempts to clarify where risks are linked to particular substances versus psychedelic use as a whole

● Individual Vulnerabilities: When possible, this typology recognizes that individual differences (e.g., genetic predispositions, pre-existing mental health conditions, or cardiovascular risk factors) influence the likelihood and severity of harms

● No Assumptions About Intent: The typology applies to all contexts of psychedelic use, including therapeutic, ceremonial, recreational, and exploratory use, without making assumptions about user intent

● Interdisciplinary Perspective: Drawing from clinical research, case studies, ethnographic reports, and anecdotal evidence to provide a multidisciplinary perspective on harms

Systemic Harms (Outside of Scope)

This typology acknowledges systemic harms associated with psychedelic use but considers them outside the scope of this paper. These include harms that are not necessarily related to the pharmacological or psychological effects of the substances but arise from social, ethical, cultural, and environmental dynamics

1. Ethical and Power-Dynamics Domain:

● Therapist/Guide Exploitation:

○ Description: Instances of sexual, financial, or emotional abuse by practitioners who wield authority over vulnerable clients, exploiting the power dynamics inherent in psychedelic-assisted therapy or ceremonial contexts

○ Examples: Coercive behaviors, boundary violations, and unethical financial demands

○ Relevance: These harms reflect systemic issues related to the unregulated nature of psychedelic services, ethical training gaps, and lack of accountability mechanisms

● Cultural Exploitation:

○ Description: Commercialization of indigenous or other practices and appropriation without consent or reciprocity

○ Examples: Misuse of traditional ceremonies or commodification of sacred plant medicines for profit without honoring indigenous knowledge holders

○ Relevance: This raises ethical concerns about cultural integrity, intellectual property rights, and the commodification of spiritual practices.

2. Environmental / Ecological Harms:

● Sustainability Concerns:

○ Description: Environmental impact due to the overharvesting of certain psychedelic plants in response to global demand.

○ Examples: Iboga (Tabernanthe iboga) and Ayahuasca (Banisteriopsis caapi and Psychotria viridis) are at risk of overharvesting, threatening their natural habitats and cultural sustainability.

○ Relevance: Raises questions about environmental stewardship, sustainable sourcing, and the ethical implications of global psychedelic demand

● Environmental Damage from Unregulated Production:

○ Description: Pollution and ecological harm resulting from unregulated synthesis of synthetic psychedelics

○ Examples: Chemical waste from clandestine labs producing LSD, 2C-x, or synthetic DMT analogs

○ Relevance: Highlights the environmental cost of prohibition-driven underground production versus regulated and sustainable practices.

3. Cultural Harms:

● Cultural Appropriation and Community Disruption:

○ Description: “Psychedelic tourism” and the global demand for plant medicines can undermine local traditions, distort cultural practices, and exploit Indigenous knowledge systems

○ Examples: Ceremonies being commodified for tourist consumption, loss of cultural context, and exploitation of traditional healers.

○ Relevance: Raises ethical concerns about cultural preservation, community autonomy, and the global power dynamics in the psychedelic renaissance.

Harm Domain Definitions

● Physical: Direct injury to bodily systems, including cardiovascular, neurological, gastrointestinal, respiratory, genitourinary, and other organ-specific harms, sometimes leading to physical disease or health complications

● Perceptual: Persistent sensory alterations or disruptions that continue beyond the acute psychedelic experience, including visual disturbances, auditory distortions, and tactile anomalies

● Psychological: Impairment of mental health or emotional well-being, including mood disturbances, anxiety, paranoia, or psychosis, leading to significant emotional distress or impaired social functioning

● Behavioral: Changes in behavior or lifestyle resulting from psychedelic use, including risky or impulsive behavior, increased substance use, impaired social functioning, and lifestyle deterioration, which may lead to extended functional impairment or significant social or legal consequences.

● Spiritual & Existential: Disruptions to spiritual or existential well-being, including identity confusion and loss of meaning leading to existential anxiety or crisis states.

● Relational / Social: Negative impacts on social relationships or community dynamics, leading to interpersonal conflict, social isolation, or exploitation, and impairing social functioning or social identity.

Harms

1. Physical Harms

● Cardiovascular Issues

○ Tachycardia (heart rate greater than 100 beats/min), palpitations, hypertension; in rarer cases, arrhythmias or severe cardiac events, e.g., myocardial infarction, cardiomyopathy, and cardiac arrest with the classic psychedelics and MDMA, and risk of QTc prolongation with psilocybin and ibogaine (Ghaznavi et al , 2025; Kafle et al., 2019; Nef et al., 2019; Li et al., 2019).

○ Intense vasoconstriction leading to limb ischemia and stroke has been reported, most commonly with high doses of LSD (Ghaznavi et al , 2025)

○ Cardiomyopathy has been associated with frequent heavy use of MDMA (Mouadili et al , 2020; Mizia-Stec et al , 2008), or acutely in extremely rare cases with MDMA or high doses of psilocybin (Kafle et al., 2019; Kotts et al., 2022).

○ Chronic MDMA use has been linked to valvular heart disease (VHD), with 28% of users showing valvulopathy on echocardiography in one study and severe cases requiring valve replacement (Droogmans et al., 2007; Sol et al., 2020). There have been no confirmed clinical cases of drug-induced VHD in the literature to date, though there are concerns that microdosing could lead to VHD

○ Potential exacerbation of pre-existing cardiovascular conditions (Nepal et al., 2017; Bae et al , 2023)

● Neurological & Seizures

○ Infrequent but serious reports of seizures with certain phenethylamines (e.g., 2C and NBOMe families, MDMA) and in some cases with 5-MeO-DMT, Ayahuasca, Psilocybin, and LSD (Bosak et al., 2013; Suzuki et al., 2015; Leach et al., 2012; Soto-Angona et al , 2024) (Evidence suggests these incidents may be linked to the simultaneous use of other drugs or underlying vulnerabilities to seizures Notably, no seizures have been reported as adverse events in modern clinical trials, all of which exclude individuals with epilepsy)

○ Serotonin Toxicity, or serotonin syndrome, produces a range of clinical symptoms from mild to life-threatening, including myoclonus (muscle jerks), muscle rigidity, severe hyperthermia, extreme and fluctuating vital signs, seizures, and comatose mental state (Malcom & Thomas, 2022) The primary risk arises when i) a Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitor (MAOI) is combined with a Serotonin-Releasing Agents (like MDMA), or ii) a MAOI (like ayahuasca) is combined with the class of Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (which includes SSRIs, Serotonin and Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs) and Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs)

● Muscle spasms, twitching, or tremors (sometimes mistaken for anxiety-related effects) are seen with the classic psychedelics including ayahausca, which may be due to a variety of causes including electrolyte imbalance, neuromuscular excitability, or psychological processes (Müller & Borgwardt, 2018; Bouso et al., 2022) MDMA is known to produce acute jaw clenching and teeth grinding that can be painful (Kalant et al., 2001)l.

● Dystonia-like effects of sustained muscle contractions or involuntary movement disorders in rare cases There are isolated case reports of dystonia resulting from MDMA use (Cosentino, 2004), and in some chronic MDMA abusers, movement disorders like tremor, dystonia, and even parkinsonian-like symptoms have been observed but causality remains unclear (Kish, 2003; Jerome et al , 2004)

● Thermoregulatory Dysregulation

○ MDMA can inhibit the hypothalamic regulation of body temperature, leading to hyperthermia, which can be life-threatening in extreme cases (Green et al , 2004; Wood et al., 2016). Mescaline has been reported to cause hyperthermia, occurring in approximately 5% of cases, according to one study (Klaiber et al , 2024). Excessive sweating without proper water intake can then lead to dehydration.

● Gastrointestinal Problems

○ Common with oral classic psychedelics: nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea (especially ayahuasca, psilocybin) (Breeksema et al , 2022; Rocha et al , 2022) Gastrointestinal distress can also occur with MDMA and ketamine (Mithoefer et al., 2011; Jagtiani, 2024).

○ “K-cramps” and other GI distress in chronic ketamine users (Muetzelfeldt et al , 2008)

● Respiratory Concerns

○ Possible respiratory depression at very high doses of ketamine, sometimes in polydrug contexts (Orhurhu et al., 2019).

● Genitourinary Damage

○ Ketamine-associated cystitis (“ketamine bladder”) is a well-documented long-term complication of chronic ketamine use, initially presenting as painful urination, blood in the urine, and inflammation of the bladder lining (Shahani et al., 2007). Over time, this inflammatory ulcerative cystitis can lead to scarring and obstruction of urinary outflow, which, if left untreated, may result in swelling of the kidneys and eventually progress to obstructive renal failure (Kannan, 2022)

○ Beyond cystitis, chronic ketamine use is strongly associated with bladder fibrosis potentially irreversible in severe cases as well as nephropathy (disease of the kidneys) (Castellani et al , 2020; Tsai et al , 2009) In addition to direct tissue damage, ketamine metabolites can form a gelatinous precipitate in the renal pelvis and ureters, contributing to urinary blockage and further renal injury (Kannan, 2022). Thus, what begins as cystitis can escalate into severe and lasting renal dysfunction with continued ketamine exposure

○ MDMA primarily causes acute kidney injury (and occasionally renal failure) by inducing hyperthermia and rhabdomyolysis, but its chronic use has not been linked with long-term kidney damage (Kannan, 2022) On rare instances, ingestion of LSD has precipitated rhabdomyolysis (muscle breakdown) leading to acute kidney injury (AKI) (Berrens et al., 2010), but there is no evidence that chronic or repeated LSD use causes cumulative kidney or liver damage

● Acute Bodily Injury from Impaired Coordination

○ Dizziness is a frequently reported adverse experience with the classic psychedelics and ketamine (Johnson et al , 2008; Schep et al , 2023)

○ Accidental injuries and falls especially in unsupervised party/festival settings (MDMA, LSD) (Santamarina et al , 2024; Kopra et al , 2022)

● Hyponatremia

○ MDMA can cause or exacerbate electrolyte disturbances and represent a potentially serious health complication (Atila et al , 2024)

● Neurotoxicity / Brain Damage

○ Animal research indicates that high or repeated doses of MDMA produce long-lasting changes to the serotonergic system, including decreases in serotonin levels and serotonin transporter expression (Lyles & Cadet, 2003; Capela et al., 2009). While some researchers argue that reductions in these markers do not necessarily indicate structural neurodegeneration, others maintain that MDMA exposure leads to lasting degeneration of serotonin axons, particularly those arising from the dorsal raphe nucleus (Biezonski & Meyer, 2011) Neuroimaging studies of heavy MDMA users suggest structural alterations in the brain, for example in the hippocampus and overall cortical gray matter (though these studies are complicated by the fact that many heavy users are also using other drugs) (den Hollander et al , 2012; Cowan et al , 2003)

○ At high doses, ketamine can acutely induce neurotoxic changes as evidenced by Olney’s lesions (Morris et al , 2021) - abnormal vacuoles (fluid-filled sacs)

forming in cortical neurons followed by apoptotic cell death Long-term recreational ketamine use has been linked to measurable brain structural changes, including widespread thinning of the cortex across frontal, parietal, and occipital lobes in people who regularly abuse ketamine (Zhong et al., 2021).

○ Mixed data exists for ibogaine–at very high doses, ibogaine has been linked to neurotoxic effects in animal studies, specifically degeneration of cerebellar Purkinje cells (O’hearn et al., 1993). However, this adverse effect appears to be dose-dependent and species-specific Notably, follow-up studies in primates did not find evidence of ibogaine-induced neurotoxicity (Mash et al , 1998)

● Liver Damage

● MDMA causes acute drug-induced liver injury (DILI), ranging from mild hepatitis to fulminant liver failure (Turillazzi et al , 2010), and is the second most common cause of acute liver injury in patients under 25 (Andreu et al., 1998). Long-term MDMA use is not known to cause chronic progressive liver disease By contrast, ketamine’s profile is the opposite of MDMA’s: the cumulative chronic use leads to cholestatic liver injury (but not fulminant liver failure), whereas infrequent use generally spares the liver (Rosenbaum et al , 2024)

2. Perceptual Harms

● Persistent Sensory Distortions and Hallucinogen Persisting Perception Disorder (HPPD)

○ The re-experiencing of one or more visual disturbances that persist after the acute effects of a psychedelic have worn off HPPD is most commonly seen after the use of LSD and psilocybin, and less commonly after DMT, 25N-NBOMe, MDMA, mescaline, ketamine, or ibogaine (Leo et al., 2013; Ford et al., 2022).

○ Symptoms include geometric hallucinations, false perceptions of movement, color flashes, intensified colors, visual trails, visual snow, afterimages, “floaters”, halos, and distortions of object size. Sometimes symptoms are short-term and do not cause distress, whereas for others these symptoms can persist for months or years and cause clinically significant distress or impairment in daily life (in which case would meet the DSM-5 criteria) (Leo et al , 2013)

○ Persistent perceptual distortions in audition (e g , persistent ringing, heightened sound sensitivity, auditory hallucinations), and touch (e.g. numbness, tingling, or phantom sensations) have also been observed after the acute drug effects have worn off, with some researchers arguing that HPPD’s diagnostic criteria should be expanded to include these other senses (Vis et al., 2021; Evans et al., 2023).

● Flashbacks and Reactivations

○ The ICD-10 defines flashbacks as short-lived visual perceptions, altered moods, and altered states of consciousness resembling the acute psychedelic state (ICD-10, F16 7, WHO 2010) Flashbacks may include sudden re-experiencing of past psychedelic visuals or bodily sensations. These experiences are typically described as brief, lasting on the order of seconds, and can have a neutral or

even positive tone, but can also be experienced as distressing (Müller et al , 2022). (Distressing flashbacks with strong cognitive and emotional facets are discussed below in the Psychological Harms section )

○ “Reactivations” are more frequently reported with 5-MeO-DMT and DMT but have also been observed with psilocybin and LSD (Dourron et al , 2023)

○ Note: Until recently, diagnostic features and definitions of "flashback" and HPPD remained unclear, leading to interchangeable use, although HPPD emphasizes visual disturbances

● Overwhelming Sensory Distortion

○ Intense sensory amplification, synesthesia, or illusions can lead to individuals feeling overwhelmed or anxious (Johnstad, 2021; Argyri et al , 2024)

○ Especially high risk if the setting is overstimulating or if the dose is unexpectedly large.

3. Psychological Harms

● “Bad Trips”: Acute Distress and Psychotic-Like Symptoms

○ Having a “Bad Trip” characterized by fear of losing control, intense dread, ego dissolution that feels threatening, catastrophic thinking, and/or intense anxiety that can escalate to panic attacks or severe paranoia, sometimes leading to dangerous behavior or self-harm attempts (Ghaznavi et al , 2025; Johnstad, 2021). The negative dimensions of “Bad trips” also occur with MDMA and ketamine MDMA and ketamine use can be accompanied by anxiety and agitation (Colcott et al., 2024), and “k-holes” (high-dose ketamine experiences) can be especially disorienting and terrifying (Muetzelfeldt et al , 2008) Individuals who score high in neuroticism and emotional lability may be more susceptible to challenging experiences that could exacerbate their existing difficulties (Breeksema et al , 2022)

○ Psychotic-like paranoia, delusions, or derealization during the session has been demonstrated across a range of classic psychedelics, MDMA, ketamine, and ibogaine (Argyri et al , 2024; Fiorentini, et al 2021; Rodríguez‐Cano et al , 2023) MDMA-related cases are very rare and reported as individual case reports (Soar et al., 2001). Individuals predisposed to psychosis or bipolar disorder, or with a family history of such conditions, are believed to be at higher risk for transient psychotic episodes with classic psychedelics, but data remains limited (Sabé et al , 2024)

● Prolonged or Induced Psychosis

○ Rare but documented cases of prolonged or induced psychosis with the classic psychedelics (including LSD, psilocybin, 5-MeO-DMT, DMT), MDMA, and ibogaine, especially in those with psychotic spectrum vulnerabilities (Sabé et al , 2024; Marta et al., 2015).

● Prolonged Derealization and Depersonalization

○ Derealization: Persistent difficulty reconnecting with reality (Argyri et al , 2024; Evans et al., 2023). Some users report feeling like they never fully "came back" from the experience, and express confusion or uncertainty over what is real (Bremler et al., 2023).

○ Depersonalization: A dissociative experience characterized by a persistent or recurrent feeling of detachment from oneself, one's body, or one's mental processes after the acute effects of the substance have worn off (Evans et al., 2023)

● Dysregulated Mood and Emotional Lability

○ Mood Swings: Rapid mood swings during and after use with the classic psychedelics; can include tearfulness, euphoria swinging into despair, etc (Carhart-Harris et al , 2016)

○ Post-Session “Crash”: MDMA is frequently associated with a “hangover” of low mood, irritability, or emotional exhaustion (Curran & Travill, 1997) Some users of classic psychedelics (including LSD, psilocybin, etc.) also report days of emotional fragility (Goldy et al , 2024)

○ Psychedelic Apathy: Some individuals report diminished drive for career, relationships, or personal growth post-experience (Lutkajtis & Evans, 2023). Can resemble "spiritual bypassing" but manifests as general disinterest in non-psychedelic aspects of life

● Post-Acute Worsening of Anxiety and Mood Disorders

○ Depressive Episodes/Suicidality: Though many studies point to potential antidepressant effects, some users (especially with pre-existing psychiatric conditions) experience worsened depression or suicidal ideation post-session (Hinkle et al , 2024; Breeksema et al , 2022) Suicidal ideation and behavior is sometimes reported in MDMA, LSD and high-dose psilocybin trials. Individuals with borderline or other personality disorders may face a fourfold greater risk of a substantial decline in well-being following a psychedelic experience (Marrocu et al., 2024).

○ Obsessive Thought Patterns: Development of fixations, particularly around psychedelic experiences (e g , hyperanalysis of visions or compulsive journaling about them) (Evans et al., 2023). Preoccupation with “message” interpretation, leading to ruminative anxiety and becoming “stuck” in their experience

○ Sleep Disregulation: Disrupted sleep cycles following acute psychedelic use, in particular with MDMA (Randall et al., 2009), and chronic use of MDMA is linked with persistent sleep cycle disturbances (Allen et al , 1993) Mixed data has been reported for microdosing–45% of people microdosing reported trouble sleeping in a recent survey (Lea et al , 2020), but a controlled research study found that microdosing LSD actually improved sleep on the night of microdosing (Allen et al., 2024). Reports of lucid dreams or intense nightmares, sometimes linked to trauma resurfacing or the experience of a “bad trip” (Evans et al , 2023)

● Trauma Memory Overwhelm and Vulnerability to Memory Distortions

○ Trauma Memory Reactivation and Overwhelm: Intense emotional memories or PTSD-like flashbacks can surface, particularly in those with unresolved trauma,

and in some cases overwhelm the participant (Krediet et al , 2020; Inserra, 2018; Rubin-Kahana et al., 2021; Elfrink & Bergin, 2025). Psilocybin, ayahuasca, and DMT can facilitate re-experiencing of traumatic events, which may be healing if guided well or destabilizing if unsupported.

○ Confabulation & False Memory Formation: Increased susceptibility to false memories due to heightened hyperactive pattern recognition under psychedelics (Doss et al., 2024; Kangaslampi & Lietz, 2024). Psychedelics weaken detailed, hippocampus-dependent memory while enhancing a more gist-like, cortex-based signal, creating a state of strong familiarity with diminished recall This may lead to memory misattributions, e.g., believing psychedelic visions are literal events from their past In controlled studies, participants under psilocybin or 2C-B struggled to recall specific details of images they had seen but were more likely to feel a sense of familiarity with images they had never actually encountered (Doss et al , 2024) Psychedelics also heighten suggestibility (Carhart-Harris et al., 2015), so individuals may be more likely to integrate external cues or narratives into re-activated memories, distorting them

● Emotional or cognitive flashbacks: sudden intrusive thoughts, emotional re-experiencing of the psychedelic experience, or recurrence of visions from the journey in ways that disrupt daily life (Evans et al , 2023; Bremler et al , 2023) Distressing flashbacks often occur after very intense experiences, and a person might suddenly re-experience the terror of a “bad trip.”

4. Cognitive Harms

● Memory Impairments

○ Acute impairment of short-term memory (MDMA, ketamine, classic psychedelics). (Basedow, et al., 2024). In particular, MDMA can impair memory or increase false recall in the short term (Kloft et al , 2022)

○ Chronic or repeated heavy ketamine or MDMA use is linked to persistent memory deficits (Morgan & Curran, 2006; Maxwell, 2005).

● Executive Dysfunction

○ Acutely, classic psychedelics and ketamine impair executive function, while these functions are relatively spared under MDMA (Basedow et al., 2024; Zhornitsky et al , 2022)

○ Heavy repeated use of ketamine and MDMA is linked with problems with decision-making, attention, or impulse control (Gomez-Escolar, et al , 2024; Maxwell, 2005)

○ May manifest as confusion, inability to focus on tasks, or risky decisions while under influence

5. Behavioral Harms

● Impulsive or High-Risk Behavior

○ Poor judgment, risk-taking, or accidental self-harm while intoxicated (Kopra et al., 2022; Bălăeţ, 2022; Darke et al., 2024).

○ Instances of violence, aggression, or disregard for safety under intense LSD, psilocybin, or DMT experiences though statistically low, do occur (Carbonaro et al , 2016)

● Social or Legal Repercussions

○ Unsafe or illegal settings, unregulated possession, or public intoxication can lead to accidents, arrest, or legal penalties (Wikipedia contributors, n d ; Palamar et al , 2024)

● Misuse and Dependence

○ While the classic psychedelics are not typically associated with dependency, some individuals struggle to find meaning or joy outside of psychedelic use with others, leading to avoidance of sober social interactions (Evans et al 2023)

○ MDMA carries some risk for developing substance use disorder, with one in five recreational MDMA users develop dependence (Bruno et al., 2012), characterized by compulsive and escalating use In clinical trials implementing MDMA for PTSD treatment, however, no evidence of misuse has been observed (Mitchell et al., 2023).

○ Ketamine carries a risk of misuse and dependence, evidenced by self-administration in animal studies (De Luca & Badiani, 2011) and heavy recreational use (Wolff & Winstock, 2006). However, clinical studies have not shown significant risks of dependence or substance use disorders (Chubbs et al , 2022), highlighting its complex risk-benefit profile.

6. Spiritual & Existential Harms

● Existential Anxiety or Crisis

○ Ego dissolution or mystical experiences can provoke crisis states feelings of meaninglessness, “ontological shock”, identity confusion, or long-lasting spiritual emergency (Evans et al , 2023; Argyri et al , 2024)

○ Some individuals report persistent existential dread or disorientation post-ceremony, with a feeling of “groundlessness” regarding the nature of reality (Argyri et al., 2024).

● Spiritual Bypassing or Narcissism

○ Users may seek repeated “transcendent” experiences to avoid real-life psychological or relational work, potentially worsening underlying issues (Aixalà, 2022; Read & Papaspyrou, 2021)

○ Risk of adopting inflated self-concepts, illusions of enlightenment, or dogmatic beliefs (Argyri et al., 2024; Evans & Adams, 2025).

● Cultural/Religious Conflicts

○ Psychedelic-induced shifts in religious/spiritual worldview may clash with one’s prior faith/worldview or that of their community, leading to distress or familial conflict (Palitsky et al , 2024; Watts, R , & Luoma, 2020; Cowley-Court et al , 2023).

● Belief System Rigidity

○ Development of rigid, unshakable spiritual beliefs that can cause alienation from family/friends (McGovern et al., 2024).

○ Resistance to questioning newfound beliefs or challenging psychedelic-induced worldviews (McGovern et al , 2024)

● Feelings of "Spiritual Failure"

○ Individuals who don’t have profound experiences (or who struggle to integrate them) may feel like they “did it wrong” or are spiritually inadequate (Gashi et al , 2021; Gorman et al., 2021). People who have challenging experiences may blame themselves or be blamed by their community for their difficulties

● Spiritual Attacks

○ In many cultural, religious, or ceremonial contexts, participants may perceive harm through the lens of spiritual attacks or curses, including harmful forces, malevolent entities, or ill-intentioned practitioners (e.g., shamans, sorcerers) (Bouso et al , 2022; Marcus, 2023) In the Global Ayahuasca Survey, about 15% of users reported “feeling ‘energetically attacked’ or a harmful connection with a spirit world” as an adverse experience during or after their ceremony (Bouso et al , 2022) While a Western medical view might label this a hallucination or paranoid delusion, within the individual’s belief framework (and the spiritual community they may belong to) such events represent a real source of harm requiring spiritual cleansing or protective rituals

7. Relational / Social Harms

● Interpersonal Conflicts

○ Heightened sensitivity or emotional volatility during or after a psychedelic experience can sometimes lead to tension in relationships or spark arguments (e g , interpreting a partner’s intentions through a paranoid lens on LSD) (Bremler et al , 2023 )

○ Family or close friends may not understand the user’s insights, deep personal realizations, or resurfaced memories, leading to interpersonal tension (Robinson et al., 2024).

● Stigma and Social Isolation

○ Fear of judgment or difficulty articulating their experience in a bid to feel understood can lead to feelings of isolation and lack of social support (Evans et al , 2023; Jivanescu et al , 2022) Sharing truthfully about one’s experience can be especially difficult when the other person has little familiarity with non-ordinary states of consciousness (Cowley-Court et al., 2023). Some users report sharing their experience and feeling hurt by others’ response, leading to a sense of alienation or identity crises (Evans et al., 2023; Jivanescu et al., 2022).

● Cultic or Devotional Enmeshment:

○ Becoming enthralled with a charismatic leader or manipulative group, leading to exploitative devotion, spiritual abuse, social isolation, and loss of autonomy (Evans & Adams, 2025).

References

Krebs, T S , & Johansen, P Ø (2013) Psychedelics and mental health: a population study PloS one, 8(8), e63972

Durante, Í , Dos Santos, R G , Bouso, J C , & Hallak, J E (2020) Risk assessment of ayahuasca use in a religious context: self-reported risk factors and adverse effects. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry, 43, 362-369

McAlpine, R G , Blackburne, G , & Kamboj, S K (2024) Development and psychometric validation of a novel scale for measuring ‘psychedelic preparedness’ Scientific Reports, 14(1), 3280.

Angyus, M., Osborn, S., Haijen, E., Erritzoe, D., Peill, J., Lyons, T., ... & Carhart-Harris, R. (2024) Validation of the imperial psychedelic predictor scale Psychological Medicine, 54(12), 3539-3547

Palitsky, R , Kaplan, D M , Perna, J , Bosshardt, Z , Maples-Keller, J L , Levin-Aspenson, H F, ... & Dunlop, B. W. (2024). A framework for assessment of adverse events occurring in psychedelic-assisted therapies Journal of Psychopharmacology, 38(8), 690-700

Carbonaro, T M , Bradstreet, M P, Barrett, F S , MacLean, K A , Jesse, R , Johnson, M W, & Griffiths, R. R. (2016). Survey study of challenging experiences after ingesting psilocybin mushrooms: Acute and enduring positive and negative consequences Journal of psychopharmacology, 30(12), 1268-1278

Griffiths, R R , Johnson, M W, Richards, W A , Richards, B D , McCann, U , & Jesse, R (2011). Psilocybin occasioned mystical-type experiences: immediate and persisting dose-related effects Psychopharmacology, 218, 649-665

Barrett, F S , Bradstreet, M P, Leoutsakos, J M S , Johnson, M W, & Griffiths, R R (2016) The Challenging Experience Questionnaire: Characterization of challenging experiences with psilocybin mushrooms. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 30(12), 1279-1295.

Studerus, E., Gamma, A., & Vollenweider, F. X. (2010). Psychometric evaluation of the altered states of consciousness rating scale (OAV) PloS one, 5(8), e12412

Evans, J , Robinson, O C , Argyri, E K , Suseelan, S , Murphy-Beiner, A , McAlpine, R , & Prideaux, E (2023) Extended difficulties following the use of psychedelic drugs: A mixed methods study. PLoS One, 18(10), e0293349.

Simonsson, O , Hendricks, P S , Chambers, R , Osika, W, & Goldberg, S B (2023)

Prevalence and associations of challenging, difficult or distressing experiences using classic psychedelics Journal of Affective Disorders, 326, 105-110

Grof, C , & Grof, S (2017) Spiritual emergency: The understanding and treatment of transpersonal crises. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 36(2), 5.

Bremler, R., Katati, N., Shergill, P., Erritzoe, D., & Carhart-Harris, R. L. (2023). Case analysis of long-term negative psychological responses to psychedelics. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 15998.

Gashi, L., Sandberg, S., & Pedersen, W. (2021). Making “bad trips” good: How users of psychedelics narratively transform challenging trips into valuable experiences International Journal of Drug Policy, 87, 102997.

Rosenbaum, D., Hare, C., Hapke, E., Herman, Y., Abbey, S. E., Sisti, D., & Buchman, D. Z. (2024) Experiential training in psychedelic‐assisted therapy: A risk‐benefit analysis Hastings Center Report, 54(4), 32-46

Evans, J , & Adams, J H (2025) Guruism and Cultic Social Dynamics in Psychedelic Practices and Organisations.

Zeller, M. (2024). Psychedelic therapies and belief change: are there risks of epistemic harm or epistemic injustice? Philosophical Psychology, 1-32

Dupuis, D , & Veissière, S (2022) Culture, context, and ethics in the therapeutic use of hallucinogens: Psychedelics as active super-placebos? Transcultural Psychiatry, 59(5), 571-578.

Timmermann, C., Watts, R., & Dupuis, D. (2022). Towards psychedelic apprenticeship: Developing a gentle touch for the mediation and validation of psychedelic-induced insights and revelations. Transcultural psychiatry, 59(5), 691-704.

Ghaznavi, S , Ruskin, J N , Haggerty, S J , King IV, F, & Rosenbaum, J F (2025) Primum non nocere: the onus to characterize the potential harms of psychedelic treatment. American Journal of Psychiatry, 182(1), 47-53

Kafle, P, Shrestha, B , Mandal, A , Sharma, D , Bhandari, M , Amgai, B , & Dufresne, A (2019). Ecstasy induced acute systolic heart failure and Non-Ischemic Cardiomyopathy in a young female: a rare case report and literature review. Journal of community hospital internal medicine perspectives, 9(4), 336-339

Nef, H M , Möllmann, H , Hilpert, P, Krause, N , Troidl, C , Weber, M , & Elsässer, A (2009) Apical regional wall motion abnormalities reminiscent to Tako-Tsubo cardiomyopathy following consumption of psychoactive fungi International journal of cardiology, 134(1), e39-e41

Li, S , Ma, Q B , Tian, C , Ge, H X , Liang, Y, Guo, Z G , & Riley, F (2019) Cardiac arrhythmias and cardiac arrest related to mushroom poisoning: a case report World journal of clinical cases, 7(16), 2330.

Mouadili, M., Elqadi, M., Goulehcen, A., Echarai, N., & Elhattaoui, M. (2020). P865 Ecstasy s use an unusual cause of dilated cardiomyopathy a case report European Heart Journal-Cardiovascular Imaging, 21(Supplement 1), jez319-509

Mizia-Stec, K , Gąsior, Z , Wojnicz, R , Haberka, M , Mielczarek, M , Wierzbicki, A , & Hartleb, M. (2008). Severe dilated cardiomyopathy as a consequence of Ecstasy intake. Cardiovascular Pathology, 17(4), 250-253

Kafle, P, Shrestha, B , Mandal, A , Sharma, D , Bhandari, M , Amgai, B , & Dufresne, A (2019). Ecstasy induced acute systolic heart failure and Non-Ischemic Cardiomyopathy in a young female: a rare case report and literature review. Journal of community hospital internal medicine perspectives, 9(4), 336-339

Kotts, W J , Gamble, D T, Dawson, D K , & Connor, D (2022) Psilocybin-induced takotsubo cardiomyopathy. BMJ Case Reports CP, 15(5), e245863.

Droogmans, S., Cosyns, B., D’haenen, H., Creeten, E., Weytjens, C., Franken, P. R., ... & Van Camp, G (2007) Possible association between 3, 4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine abuse and valvular heart disease The American journal of cardiology, 100(9), 1442-1445

Sol, B , Nijs, J , Forsyth, R , & Droogmans, S (2020)

Methylenedioxymethamphetamine-induced toxic valvulopathy. European Heart Journal-Case Reports, 4(6), 1-2

Nepal, C , Patel, S , Ahmad, N , Mirrer, B , & Cohen, R (2017) Out of Hospital Cardiac Arrest

Triggered by LSD in a Patient with Suspected Brugada Syndrome In B55 CRITICAL CARE

CASE REPORTS: DRUG OVERDOSES (pp. A3773-A3773). American Thoracic Society.

Bae, S , Vaysblat, M , Bae, E , Dejanovic, I , & Pierce, M (2023) Cardiac arrest associated with psilocybin use and hereditary hemochromatosis. Cureus, 15(5).

Bosak, A., LoVecchio, F., & Levine, M. (2013). Recurrent seizures and serotonin syndrome following “2C-I” ingestion Journal of medical toxicology, 9, 196-198

Suzuki, J , Dekker, M A , Valenti, E S , Cruz, F A A , Correa, A M , Poklis, J L , & Poklis, A (2015). Toxicities associated with NBOMe ingestion a novel class of potent hallucinogens: a review of the literature. Psychosomatics, 56(2), 129-139.

Leach, J. P., Mohanraj, R., & Borland, W. (2012). Alcohol and drugs in epilepsy: pathophysiology, presentation, possibilities, and prevention Epilepsia, 53, 48-57

Soto-Angona, Ó , Fortea, A , Fortea, L , Martínez-Ramírez, M , Santamarina, E , López, F J G , ... & Ona, G. (2024). Do classic psychedelics increase the risk of seizures? A scoping review. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 85, 35-42

Malcolm, B , & Thomas, K (2022) Serotonin toxicity of serotonergic psychedelics Psychopharmacology, 239(6), 1881-1891

Müller, F, & Borgwardt, S (2019) Acute effects of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) on resting brain function. Swiss medical weekly, 149(3940), w20124-w20124.

Bouso, J. C., Andión, Ó., Sarris, J. J., Scheidegger, M., Tófoli, L. F., Opaleye, E. S., ... & Perkins, D (2022) Adverse effects of ayahuasca: Results from the Global Ayahuasca Survey PLOS Global Public Health, 2(11), e0000438

Kalant, H (2001) The pharmacology and toxicology of “ecstasy”(MDMA) and related drugs Cmaj, 165(7), 917-928.

Cosentino, C. (2004). Ecstasy and acute dystonia. Movement Disorders: Official Journal of the Movement Disorder Society, 19(11), 1386-1387

Kish, S J (2003) What is the evidence that Ecstasy (MDMA) can cause Parkinson's disease? Movement disorders: official journal of the Movement Disorder Society, 18(11), 1219-1223

Jerome, L , Doblin, R , & Mithoefer, M (2004) Ecstasy use–Parkinson's disease link tenuous Movement Disorders: Official Journal of the Movement Disorder Society, 19(11), 1386-1386.

Green, A. R., O'shea, E., & Colado, M. I. (2004). A review of the mechanisms involved in the acute MDMA (ecstasy)-induced hyperthermic response European journal of pharmacology, 500(1-3), 3-13.

Wood, D. M., Giraudon, I., Mounteney, J., & Dargan, P. I. (2016). Hospital emergency presentations and acute drug toxicity in Europe: update from the Euro-DEN Plus research group and the EMCDDA Publications Office of the European Union

Klaiber, A , Humbert‐Droz, M , Ley, L , Schmid, Y, & Liechti, M E (2024) Safety pharmacology of acute mescaline administration in healthy participants. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology

Breeksema, J J , Kuin, B W, Kamphuis, J , van den Brink, W, Vermetten, E , & Schoevers, R A. (2022). Adverse events in clinical treatments with serotonergic psychedelics and MDMA: A mixed-methods systematic review. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 36(10), 1100-1117.

Rocha, J. M., Rossi, G. N., Osório, F. L., Hallak, J. E. C., & Dos Santos, R. G. (2022). Adverse effects after ayahuasca administration in the clinical setting Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 42(3), 321-324.

Mithoefer, M. C., Wagner, M. T., Mithoefer, A. T., Jerome, L., & Doblin, R. (2011). The safety and efficacy of±3, 4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine-assisted psychotherapy in subjects with chronic, treatment-resistant posttraumatic stress disorder: the first randomized controlled pilot study. Journal of psychopharmacology, 25(4), 439-452.

Jagtiani, A. (2024). Novel treatments of depression: bridging the gap in current therapeutic approaches Exploration of Neuroscience, 3(4), 272-286

Muetzelfeldt, L , Kamboj, S K , Rees, H , Taylor, J , Morgan, C J A , & Curran, H V (2008) Journey through the K-hole: phenomenological aspects of ketamine use Drug and alcohol dependence, 95(3), 219-229.

Orhurhu, V. J., Vashisht, R., Claus, L. E., & Cohen, S. P. (2019). Ketamine toxicity.

Barker, S A (2022) Administration of N, N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT) in psychedelic therapeutics and research and the study of endogenous DMT. Psychopharmacology, 239(6), 1749-1763

Shahani, R., Streutker, C., Dickson, B., & Stewart, R. J. (2007). Ketamine-associated ulcerative cystitis: a new clinical entity Urology, 69(5), 810-812

Kannan, L (2022) Renal manifestations of recreational drugs: A narrative review of the literature Medicine, 101(50), e31888

Castellani, D , Pirola, G M , Gubbiotti, M , Rubilotta, E , Gudaru, K , Gregori, A , & Dellabella, M. (2020). What urologists need to know about ketamine‐induced uropathy: a systematic review Neurourology and Urodynamics, 39(4), 1049-1062

Tsai, T H , Cha, T L , Lin, C M , Tsao, C W, Tang, S H , Chuang, F P, & Chang, S Y (2009) Ketamine‐associated bladder dysfunction International journal of urology, 16(10), 826-829.

Berrens, Z., Lammers, J., & White, C. (2010). Rhabdomyolysis after LSD ingestion. Psychosomatics, 51(4), 356-356

Johnson, M W, Richards, W A , & Griffiths, R R (2008) Human hallucinogen research: guidelines for safety. Journal of psychopharmacology, 22(6), 603-620.

Schep, L. J., Slaughter, R. J., Watts, M., Mackenzie, E., & Gee, P. (2023). The clinical toxicology of ketamine Clinical Toxicology, 61(6), 415-428

Santamarina, R , Caldicott, D , Fitzgerald, J , & Schumann, J L (2024) Drug-related deaths at Australian music festivals. International Journal of Drug Policy, 123, 104274.

Kopra, E. I., Ferris, J. A., Rucker, J. J., McClure, B., Young, A. H., Copeland, C. S., & Winstock, A. R. (2022). Adverse experiences resulting in emergency medical treatment seeking following the use of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) Journal of Psychopharmacology, 36(8), 956-964

Atila, C , Straumann, I , Vizeli, P, Beck, J , Monnerat, S , Holze, F, & Christ-Crain, M (2024)

Oxytocin and the Role of Fluid Restriction in MDMA-Induced Hyponatremia: A Secondary Analysis of 4 Randomized Clinical Trials JAMA Network Open, 7(11), e2445278-e2445278

Lyles, J , & Cadet, J L (2003) Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, Ecstasy) neurotoxicity: cellular and molecular mechanisms Brain Research Reviews, 42(2), 155-168

Capela, J P, Carmo, H , Remião, F, Bastos, M L , Meisel, A , & Carvalho, F (2009) Molecular and cellular mechanisms of ecstasy-induced neurotoxicity: an overview. Molecular neurobiology, 39, 210-271

K Biezonski, D , & S Meyer, J (2011) The nature of 3, 4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-induced serotonergic dysfunction: evidence for and against the neurodegeneration hypothesis. Current neuropharmacology, 9(1), 84-90.

den Hollander, B., Schouw, M., Groot, P., Huisman, H., Caan, M., Barkhof, F., & Reneman, L. (2012) Preliminary evidence of hippocampal damage in chronic users of ecstasy Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 83(1), 83-85.

Cowan, R. L., Lyoo, I. K., Sung, S. M., Ahn, K. H., Kim, M. J., Hwang, J., ... & Renshaw, P. F. (2003). Reduced cortical gray matter density in human MDMA (Ecstasy) users: a voxel-based morphometry study Drug and alcohol dependence, 72(3), 225-235

Morris, P J , Burke, R D , Sharma, A K , Lynch, D C , Lemke-Boutcher, L E , Mathew, S , & Thomas, C. J. (2021). A comparison of the pharmacokinetics and NMDAR antagonism-associated neurotoxicity of ketamine,(2R, 6R)-hydroxynorketamine and MK-801 Neurotoxicology and teratology, 87, 106993

Zhong, J , Wu, H , Wu, F, He, H , Zhang, Z , Huang, J , & Fan, N (2021) Cortical thickness changes in chronic ketamine users. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 645471.

O'hearn, E., & Molliver, M. E. (1993). Degeneration of Purkinje cells in parasagittal zones of the cerebellar vermis after treatment with ibogaine or harmaline Neuroscience, 55(2), 303-310

Mash, D C , Kovera, C A , Buck, B E , Norenberg, M D , Shapshak, P, Hearn, W L , & Sanchez‐Ramos, J. U. A. N. (1998). Medication Development of Ibogaine as a Pharmacotherapy for Drug Dependence a Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 844(1), 274-292.

Turillazzi, E., Riezzo, I., Neri, M., Bello, S., & Fineschi, V. (2010). MDMA toxicity and pathological consequences: a review about experimental data and autopsy findings. Current pharmaceutical biotechnology, 11(5), 500-509

Andreu, V, Mas, A , Bruguera, M , Salmerón, J M , Moreno, V, Nogué, S , & Rodés, J (1998) Ecstasy: a common cause of severe acute hepatotoxicity. Journal of hepatology, 29(3), 394-397.

Rosenbaum, S. B., Gupta, V., Patel, P., & Palacios, J. L. (2024). Ketamine. In StatPearls [Internet] StatPearls Publishing

Leo, H , Melanie, S , Martin, R , Anil, B , & Martin, G (2013) Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder (HPPD) and flashback–are they identical J Alcoholism Drug Depend, 1(121), 2

Ford, H , Fraser, C L , Solly, E , Clough, M , Fielding, J , White, O , & Van Der Walt, A (2022) Hallucinogenic persisting perception disorder: a case series and review of the literature. Frontiers in Neurology, 13, 878609

Vis, P J , Goudriaan, A E , Ter Meulen, B C , & Blom, J D (2021) On perception and consciousness in HPPD: A systematic review Frontiers in neuroscience, 15, 675768

WHO (2010) ICD-10 : international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems : tenth revision

Müller, F., Kraus, E., Holze, F., Becker, A., Ley, L., Schmid, Y., ... & Borgwardt, S. (2022). Flashback phenomena after administration of LSD and psilocybin in controlled studies with healthy participants. Psychopharmacology, 239(6), 1933-1943.

Dourron, H. M., Nichols, C. D., Simonsson, O., Bradley, M., Carhart-Harris, R., & Hendricks, P. S. (2023). 5-MeO-DMT: An atypical psychedelic with unique pharmacology, phenomenology & risk? Psychopharmacology, 1-23

Johnstad, P G (2021) Day trip to hell: A mixed methods study of challenging psychedelic experiences. Journal of Psychedelic Studies, 5(2), 114-127.

Argyri, E. K., Evans, J., Luke, D., Michael, P., Michelle, K., Rohani-Shukla, C., ... & Robinson, O. (2024) Navigating Groundlessness: An interview study on dealing with ontological shock and existential distress following psychedelic experiences Available at SSRN 4817368

Ghaznavi, S , Ruskin, J N , Haggerty, S J , King IV, F, & Rosenbaum, J F (2025) Primum non nocere: the onus to characterize the potential harms of psychedelic treatment. American Journal of Psychiatry, 182(1), 47-53

Colcott, J , Guerin, A A , Carter, O , Meikle, S , & Bedi, G (2024) Side-effects of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychopharmacology, 49(8), 1208-1226

Ceban, F, Rosenblat, J D , Kratiuk, K , Lee, Y, Rodrigues, N B , Gill, H , & McIntyre, R S (2021). Prevention and management of common adverse effects of ketamine and esketamine in patients with mood disorders. CNS drugs, 35(9), 925-934.

Muetzelfeldt, L., Kamboj, S. K., Rees, H., Taylor, J., Morgan, C. J. A., & Curran, H. V. (2008). Journey through the K-hole: phenomenological aspects of ketamine use Drug and alcohol dependence, 95(3), 219-229.

Fiorentini, A., Cantù, F., Crisanti, C., Cereda, G., Oldani, L., & Brambilla, P. (2021). Substance-induced psychoses: an updated literature review Frontiers in psychiatry, 12, 694863

Rodríguez‐Cano, B J , Kohek, M , Ona, G , Alcázar‐Córcoles, M Á , Dos Santos, R G , Hallak, J E , & Bouso, J C (2023) Underground ibogaine use for the treatment of substance use disorders: A qualitative analysis of subjective experiences. Drug and Alcohol Review, 42(2), 401-414

Soar, K , Turner, J J D , & Parrott, A C (2001) Psychiatric disorders in Ecstasy (MDMA) users: a literature review focusing on personal predisposition and drug history Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental, 16(8), 641-645.

Sabé, M., Sulstarova, A., Glangetas, A., De Pieri, M., Mallet, L., Curtis, L., ... & Kirschner, M. (2024) Reconsidering evidence for psychedelic-induced psychosis: an overview of reviews, a systematic review, and meta-analysis of human studies. Molecular Psychiatry, 1-33.

Marta, C. J., Ryan, W. C., Kopelowicz, A., & Koek, R. J. (2015). Mania following use of ibogaine: A case series. The American Journal on Addictions, 24(3), 203-205.

Curran, H. V., & Travill, R. A. (1997). Mood and cognitive effects of±3, 4‐methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA,‘ecstasy’): week‐end ‘high’ followed by mid‐week low. Addiction, 92(7), 821-831.

Goldy, S. P., Du, B. A., Rohde, J. S., Nayak, S. M., Strickland, J. C., Ehrenkranz, R., ... & Yaden, D B (2024) Psychedelic risks and benefits: A cross-sectional survey study Journal of Psychopharmacology, 02698811241292951

Carhart-Harris, R L , Kaelen, M , Bolstridge, M , Williams, T M , Williams, L T, Underwood, R , ... & Nutt, D. J. (2016). The paradoxical psychological effects of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) Psychological medicine, 46(7), 1379-1390

Hinkle, J T, Graziosi, M , Nayak, S M , & Yaden, D B (2024) Adverse events in studies of classic psychedelics: A systematic review and meta-analysis JAMA psychiatry

Marrocu, A , Kettner, H , Weiss, B , Zeifman, R J , Erritzoe, D , & Carhart-Harris, R L (2024) Psychiatric risks for worsened mental health after psychedelic use. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 38(3), 225-235