GLOBAL CATHOLICISM

Journal of VOLUME 7 | ISSUE 1

• The Parish Choir Movement and Generational Festivals in Romania’s Socialist Period • Girls’ Education and Child Marriage in Central Africa Part I: The Democratic Republic of Congo • Girls’ Education and Child Marriage in Central Africa Part II: The Republic of Congo • Renovation, Demolition, and the Architectural Politics of Local Belonging at the Our

of Csíksomlyó Hungarian

Shrine

Cover image: Romkat.ro, Mária Csúcs, László Dezső WINTER 2022 IN THIS ISSUE

Lady

National

THE JOURNAL OF GLOBAL CATHOLICISM is an international, interdisciplinary peer-reviewed journal. Its purpose is to foster the understanding of diverse forms of lived Catholicism with attention to their significance for theoretical approaches in anthropology, history, sociology, media studies, psychology, theology, and philosophy.

An open-access publication, the Journal of Global Catholicism is part of the Catholics & Cultures initiative (www.catholicsandcultures.org), administered by the Rev. Michael C. McFarland, S.J. Center for Religion, Ethics and Culture at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, USA. Read our Peer Review Statement of Principles and Commitments.

DIRECTOR & PUBLISHER

Thomas M. Landy, PhD, College of the Holy Cross

FOUNDER & EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Mathew N. Schmalz, PhD, College of the Holy Cross

MANAGING EDITOR

Marc Roscoe Loustau, ThD

PUBLICATIONS MANAGER

Danielle Lamoureux-Kane, College of the Holy Cross

EDITORIAL BOARD

Bernardo E. Brown, International Christian University, Tokyo

Michel Chambon, National University of Singapore

Teresia Hinga, Santa Clara University

Eunice Kamaara, Moi University, Kenya

Magdalena Lubanska, University of Warsaw

Kerry P. C. San Chirico, Villanova University Rev. Bernhard Udelhoven, Society of the Missionaries of Africa

2 |

JOURNAL OF GLOBAL CATHOLICISM

Journal of GLOBAL CATHOLICISM

VOLUME 7 ISSUE 1

INTRODUCTION

• Marc Roscoe Loustau / Overview & Acknowledgments 4

ARTICLES

• Eszter Kovács / The Parish Choir Movement and Generational Festivals 8 in Romania’s Socialist Period: New Community Festivities in Transylvania’s Gheorgheni (Gyergyó) Region

• Geneviève Bagamboula Mayamona, Jean-Christophe Boungou Bazika, 32 and Quentin Wodon / Girls’ Education and Child Marriage in Central Africa: Insights from Qualitative Fieldwork Part I: The Democratic Republic of Congo

• Jean-Christophe Boungou Bazika, Wolf Ulrich Mféré Akiana, and Quentin Wodon / 60 Girls’ Education and Child Marriage in Central Africa: Insights from Qualitative Fieldwork Part II: The Republic of Congo

• Marc Roscoe Loustau / Airplane Hangars and Triple Hills: 90 Renovation, Demolition, and the Architectural Politics of Local Belonging at the Our Lady of Csíksomlyó Hungarian National Shrine

ON THE COVER

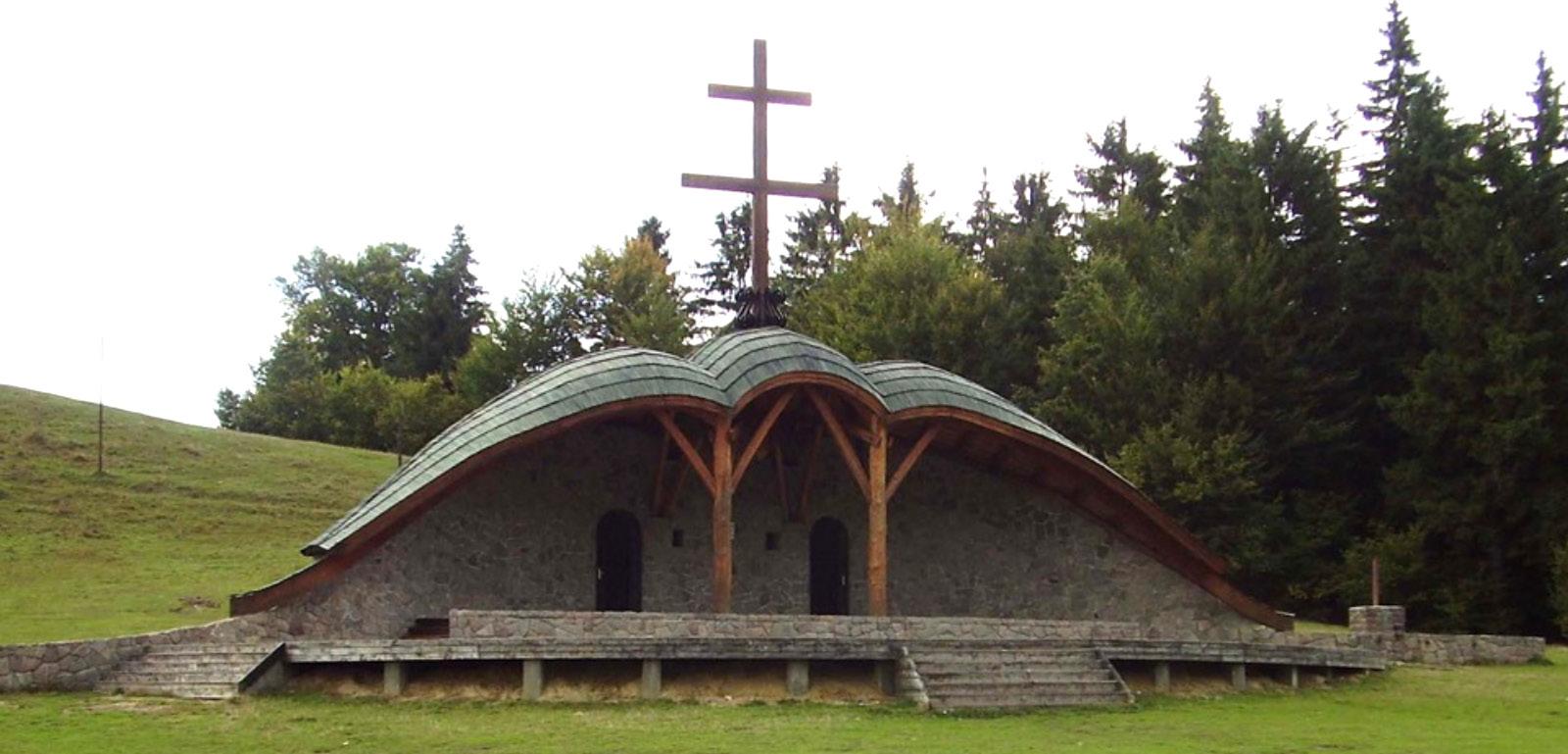

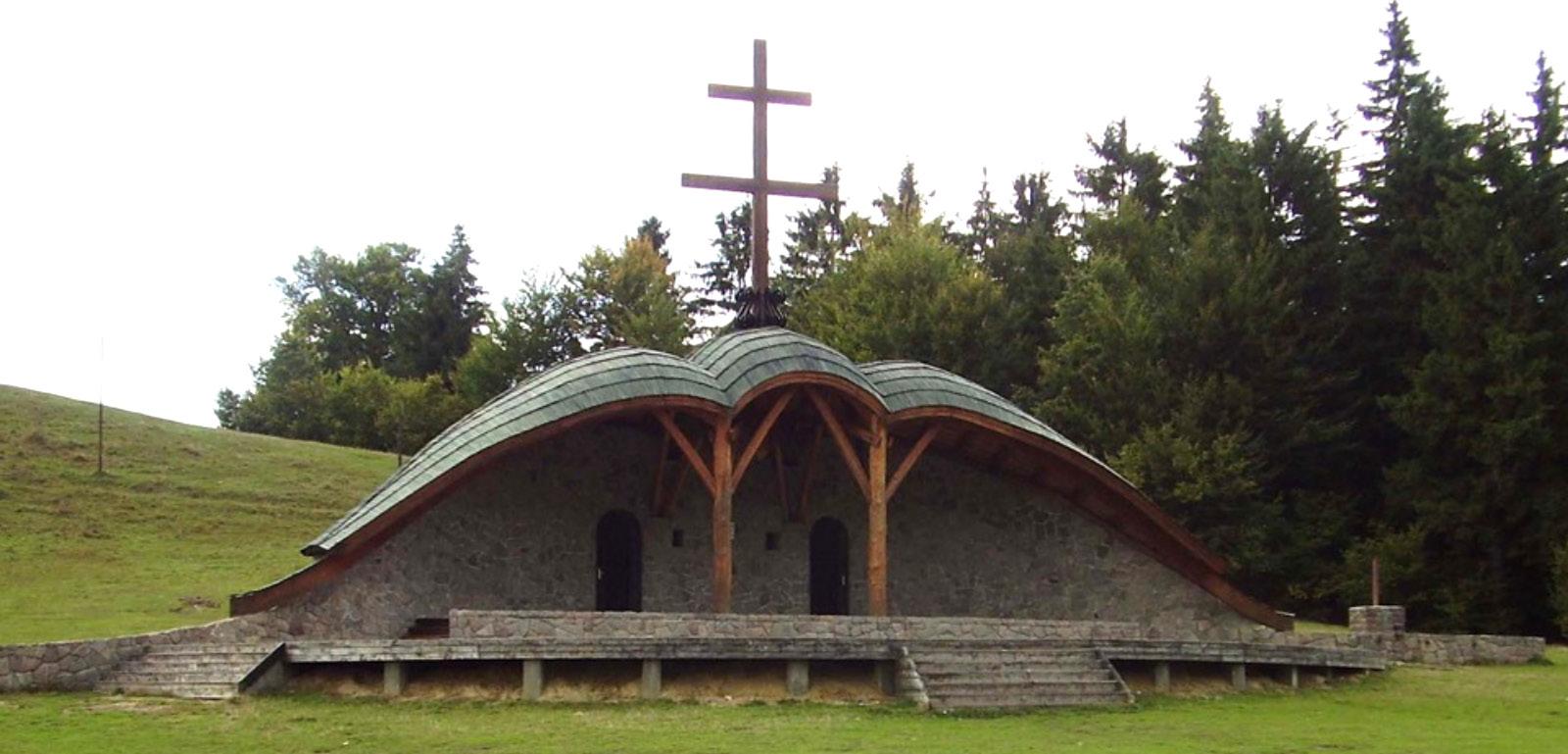

The iconic Triple Hill design of the altar at Our Lady of Csíksomlyó Hungarian National Shrine was obscured by roofing installed for the pope’s visit in 2019, raising the ire of hundreds of Hungarians who expressed their outrage on Facebook. See article inside.

Photo: Romkat.ro, Mária Csúcs, László Dezső.

| 3 VOLUME 7 ISSUE 1 | WINTER 2022

MARC ROSCOE LOUSTAU

Overview & Acknowledgments

Marc Roscoe Loustau is Managing Editor of the Journal of Global Catholicism and a Catholics & Cultures contributor. An anthropologist and scholar of religion, he earned a masters of divinity and a doctoral degree in religious studies from Harvard Divinity School. He holds a bachelor of arts in social anthropology from Reed College. He is author of Hungarian Catholic Intellectuals in Romania: Reforming Apostles, Contemporary Anthropology of Religion (Palgrave Macmillan, 2022). He is editor, with Eric Hoenes del Pinal and Kristin Norget, of Mediating Catholicism: Religion and Media in Global Catholic Imaginaries (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2022). He is the recipient of multiple awards and research grants, including a Dissertation Finishing Grant from the Panel on Theological Education, an East European Language Training Grant from the American Council of Learned Societies, a Frederick Knox Traveling Fellowship from Harvard University, and a John L. Loeb Fellowship from Harvard Divinity School. He has taught courses on Global Catholicism, Ethnographic Research Methods, and Charismatic and Pentecostal Christianities.

4 JOURNAL OF GLOBAL CATHOLICISM

With this issue, the Journal of Global Catholicism now welcomes all submissions. To this point we have published Special Issues of articles that gathered around and reflected on a single theme, like our issue on “Mediating Catholicisms” (vol. 3, no. 2, 2019). Others were based on research in a particular region of the world, like “Brazilian Catholicism” (vol. 5, no. 2, 2021). We are happy to announce that going forward we will also publish issues of individual articles submitted to us via our online system at https://crossworks.holycross.edu/jgc.

This issue includes two articles describing a mixed-methods research project on girls’ education in sub-Saharan Africa, specifically in the Republic of Congo (RoC) and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Both articles befit the JGC’s focus on lived Catholicism, which foregrounds the dynamic and conflictual nature of faith in a changing world. This dynamism and disagreement are most evident in the focus group conversations convened by Geneviève Bagamboula Mayamona, Jean-Christophe Boungou Bazika, and Quentin Wodon in the DRC and by Boungou Bazika, Wolf Ulrich Mféré Akiana, and Wodon in the RoC.

In the focus groups, the researchers described participants reflecting on trends toward marriage for “choice” and “love.” In some communities in the DRC, they write, parents influence marital decisions, while in others girls receive advice from multiple sources and the value of modern choice is growing. Anthropologists have noted similar diversity in views about marriage, even in neighboring villages, while doing research in sub-Saharan Africa, and growing recognition of urbanization and social change in this area has led to a conversation about “African marriages in transformation.”1

1 Julia Pauli, “African Marriages in Transformation: Anthropological Insights,” In Introduction to Gender Studies in Eastern and Southern Africa: A Reader, edited by James Etim (London: Sense Publishers, 2016), 95–113. See, for example, the Catholics & Cultures site on Nigeria: “Modernity and city life also seem to be transforming the family in modest ways,…” Thomas Landy, “Family Building in Nigeria Carries on Lineage, Spirit of Ancestors,” Catholics & Cultures, May 21, 2020, https://www.catholicsandcultures.org/family-building-nigeria-carries-lineage-spirit-ancestors

Marc Roscoe Loustau | 5 VOLUME 7 ISSUE 1 | WINTER 2022

While the researchers are also advocates for girls’ education, which they believe is hindered by the practice of early marriage in these countries, they also note that family and friends accord great status value to marriage, lineage, clan, and family; even research that emerges from a normative perspective can recognize that lived Catholicism is Catholicism embedded in and activated by multiple overlapping and meaningful social communities.

Eszter Kovács, a historian and social scientific researcher at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, describes present-day recollections on “underground” and “informal” Catholic practices of gathering and celebration during Romania’s Communist period before 1989. Her research, drawn from a dissertation that will be published next year, focuses on Catholic parish choirs that, beginning in the late 1980s, gathered to perform for each other and improve the quality of their singing. One enlightening moment in her article notes the element of strategy and access to resources that led leaders of these parish choir festivals to organize informally. They might have sought help from the state to acquire buses for transportation and food for the post-festival party, but this would have required making certain concessions in the festivals’ timing and content. It’s not that faith was “illegal” or “forbidden” in this period. Rather, Kovács’s appropriation of the concept of informality captures the catch-as-catch-can sense of choice within limits that characterized collective practices of faith under Communism.

This issue also includes an article by myself about online controversies surrounding the arrival of Pope Francis to a Catholic shrine in Romania’s Transylvania region. The controversy did not take up liturgical issues over traditional versus new forms of worship, a question that has divided English-speaking Catholics in North America. Instead, I reflected on the historical background that explains how architecture became the privileged site for debating the national character of Catholicism in Hungarian-speaking parts of Eastern Europe, a reality reflected by the fact that online commentators were incensed by architectural changes Vatican officials requested prior to the pope’s arrival at Our Lady of Csíksomlyó.

6 | Overview & Acknowledgments

JOURNAL OF GLOBAL CATHOLICISM

My gratitude goes to Mathew Schmalz, the JGC’s Founding Editor, and Thomas Landy, Director of the Catholics & Cultures initiative at the College of the Holy Cross. Special thanks also go to Danielle Kane, Associate Director for Communications at the Rev. Michael C. McFarland, S.J. Center for Religion, Ethics and Culture, and Ruby Francis, Program Coordinator for the McFarland Center at Holy Cross.

WORKS CITED

Landy, Thomas. “Family Building in Nigeria Carries on Lineage, Spirit of Ancestors.” Catholics & Cultures. May 21, 2020. https://www.catholicsandcultures.org/family-building-nigeria-carries-lineage-spirit-ancestors

Pauli, Julia. “African Marriages in Transformation: Anthropological Insights.” In Introduction to Gender Studies in Eastern and Southern Africa: A Reader, edited by J. Etim, 95–113. London: Sense Publishers, 2016.

Marc Roscoe Loustau | 7 VOLUME 7 ISSUE 1 | WINTER 2022

ESZTER KOVÁCS

The Parish Choir Movement and Generational Festivals in Romania’s Socialist Period: New Community Festivities

Transylvania’s Gheorgheni (Gyergyó) Region

in

Eszter Kovács is an ethnographer and historian who studies Hungarian minorities in Romania during the period of state socialism before 1989. She recently completed her doctoral studies at Corvinus University of Budapest, and her PhD thesis is titled “Informality, Self-organization, Quasi-publicity: Culture, sport, everyday discourses, church holidays and entertainment in the Gheorgheni Basin in the 1970s and 1980s.” Since 2017, she has been teaching at Pázmány Péter Catholic University in the Institute of Media and Communication. Her book based on dissertation will be published in 2024.

8 JOURNAL OF GLOBAL CATHOLICISM

Among the post-1945 East European socialist regimes, Romania and Poland were the only countries where the Catholic Church—despite government interventions, controls, and bans—managed to play a significant social and political role in community life. In spite of the persecution of churches beginning in the 1950s, the number of laypeople involved in Catholic Church activities continued to grow. Believers did not participate in the life of the Church to reject the Party state nor to engage in underground culture and read “samizdat” publications; but rather, I argue, because they required their preexisting frameworks for and habits of everyday thought and behavior. Parishes and religious communities remained independent from the lower- and higher-level Communist Party political leadership. The Church brought people together for regular events, and it provided opportunities for believers to build community and strengthen their awareness of their own distinctive cultural identity.

In Romania, the Party state and the Catholic Church never signed a formal agreement or legal accord. The regime tolerated the Catholic Church even though the Church was attached to an outside controlling power, the Vatican, in stark contrast with the Communist Party’s basic principles of operation.1 The socialist state did not recognize the official status of the Catholic Church, and priests were still regarded as a dangerous social group that posed a threat to the security of the state. Nevertheless, Catholic priests practiced their profession actively, and the majority of believers still participated in various aspects of parish life.2 This case study provides an ethnographic description of the parish choir movement and graduating class reunions, called “generational festivals” in Hungarian, in the Gheorgheni (Hu: Gyergyó) region in the 1970s and 1980s.3 During this period, these social and community gatherings became important public events even as

1 Miklós Tomka, “Egyház és “civil társadalom,” Vigilia 63 no. 5 (1998): 339–342; Miklós Tomka, “Vallásosság Kelet-Közép-Európában: Tények és értelmezések,” Szociológiai Szemle 3 (2009): 66–67.

2 József Marton, “A gyulafehérvári katolikus egyház a kommunizmus idején,” Studia Theologica Transsylvaniensia 2 (2012): 61–65, 75.

3 The organization of generation meetings became fashionable all around the Székely Land in the discussed era.

Eszter Kovács | 9 VOLUME 7 ISSUE 1 | WINTER 2022

they incorporated elements of religious rituals.4 The gatherings will be analyzed in the context of everyday life, the socialist system’s distinctive shortage economy, and official limits on religious activity that characterized the era. I will first describe the world of parish choir festivals, including the outside (official government) pressures that shaped the festivals by forcing organizers to make accommodations. In my descriptions of the choir festivals, I highlight ways in which participants exploited opportunities to engage in Catholic rituals as “informal” practices despite the government’s official ban on public religious ceremonies. I will also reconstruct and describe the most important features of these socialist-era festivals.

METHODOLOGY AND CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

This case study is based on semi-structured, in-depth interviews.5 This interview method helps the researcher get closer to the interviewees’ life in the past, making it possible to describe and reconstruct life events as subjects’ experienced and interpreted them.6 However, it must also be taken into account that the researcher is not omniscient, nor does he or she possess every possible aspect for the reconstruction of the past, and he or she always interprets and evaluates the past from the perspective of the present.7 Therefore, this interview method does not reflect on the differences between the past experience and the events recalled in the present, nor on the changes in the thirty years that have passed since the 1970s and 1980s. This method does not make it possible to tell what actually happened, and thus this paper does not aim to explore the objective truth or objective history.8 The

4 Zoltán A. Biró, Stratégiák vagy kényszerpályák? Tanulmányok a romániai magyar társadalomról (Miercurea Ciuc, Romania: Pro Print, 1998), 19; Vilmos Keszeg, “Vasárnap: natúra vagy kultúra,” in A fiatalok vasárnapja Európában, eds. V. Keszeg, F. Pozsony, and T. Tőtszegi (Cluj-Napoca, Romania: Kriza, 2009), 23.

5 The case study is part of research which was implemented in the form of a doctoral dissertation (“Informalitás, önszerveződés, kvázi-nyilvánosság. Kultúra, sport, hétköznapi diskurzusok, egyházi ünnepek és szórakozás a Gyergyói-medencében az 1970-1980-as években.” “Informality, self-organisation and quasi-publicity. Culture, sports, everyday discourse, religious holidays and entertainment in the Gyergyó Basin in the 1970s and 1980s”), the main subject of which is the reconstruction of the experience of everyday life events in the Gheorgheni region in the 1970s and 1980s.

6 Kvale Steinar, Az interjú – Bevezetés a kvalitatív kutatás interjútechnikáiba (Budapest: Jószöveg Műhely, 2005), 20.

7 Gábor Gyáni, A történelem, mint emlék(mű) (Budapest: Kalligram, 2016), 55–56.

8 Éva Kovács, “Elbeszélt történelem,” Replika, 63 (2007): 42–43.

JOURNAL OF GLOBAL CATHOLICISM

10

| The Parish Choir Movement and Generational Festivals in Romania’s Socialist Period: New Community Festivities in Transylvania’s Gheorgheni (Gyergyó) Region

purpose of the interviews was to invite subjects to recall the social context and their experience.

This case study is based on seven interviews conducted with eight persons, the material of 10 hours of conversations, which were recorded between January 2018 and July 2020. A database was created from the typed script of the interviews where the anonymized interviewees were assigned codes (e.g., R1, R2, etc.). The codes were grouped according to the following factors: gender, age, type of settlement, occupation, and type of interview.9 Only broad categories are given for their occupation. The respondents were associated with the two discussed topics in the given period, for example, they actively participated in the parish life and/or the organization of other community events.

A significant concept of the theoretical framework of the paper is informality, which in some contexts denotes the application of non-conventional activities, in contrast to formal regulations and official procedures: for example events occurring behind the official scene and forms of interaction when the partners can perform their expected roles relatively freely.10 Informality in a broader sense refers to open secrets, unwritten rules and hidden practices, 11 the ways people arrange things in various fields of life.12 To capture the sociopolitical and sociocultural factors of this phenomenon, Alena Ledeneva uses the example of the Russian term “blat.”

9 For the anonymization of the interviews, I followed Luis Corti, Annette Day and Gill Backhouse’s article on the anonymization of qualitative data. Luis Corti, “Progress and Problems of Preserving and Providing Access to Qualitative Data for Social Research: The International Picture of an Emerging Culture,” Qualitative Social Research 1, no. 3 (2000) https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-1.3.1019; Luis Corti, Anette Day, Gill Backhouse, “Confidentiality and Informed Consent: Issues for Consideration in the Preservation of and Provision of Access to Qualitative Data Archives,” Qualitative Social Research 1, no. 3 (2000). https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-1.3.1024

10 Barbara A. Misztal, Informality. Social Theory and Contemporary Practice (London: Routledge, 2000), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203003626

11 The equivalent of the Soviet blat was the acronym PCR in colloquial Romanian language, which seemingly stood for the Romanian Communist Party (Partidul Comunist Român) and its help, but in everyday language it meant Pile – Cunostinţe – Relaţii (contacts, knowledge, relations), which were necessary for arranging things. Stoica Augustin, “Old Habits Die Hard? An Exploratory Analysis of Communist-Era Social Ties in Post-Communist Romania,” European Journal of Science and Theology 8 (2012): 172–175.

12 Alena Ledeneva, Global Encyclopaedia of Informality: Understanding Social and Culture Complexity, Volume I (London: UCL Press, 2018), 1, https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781911307907.

Eszter Kovács | 11 VOLUME 7 ISSUE 1 | WINTER 2022

It denoted the informal contacts which developed as a result of the shortage economy in the Soviet Union. The term referred to the so-called arrangements, the way people handled their affairs through their personal connections in the system of mutual favors. Blat developed parallel with the regime, helping people to obtain basic necessities, work and housing. For example, people used blat to get family members who were class enemies, or kulaks, get out of prison. Party members used blat to arrange baptisms for their children despite bans on Party members’ participation in religious rituals.13 Ledeneva’s approach—stepping beyond research focusing on economic motivations—draws the attention to the unique social practices of informal self-organization, and also to the fact that informality relied on linguistic practices at regional, local or even personal idiosyncratic levels.

The other central concept is that of the quasi-public sphere, which was coined to describe everyday life under socialism.14 The quasi-public sphere selected values that had been preserved in the private sphere, which was isolated from public life. Actors then moved these values into the official sphere. This sphere was formal and official but also provided space for informal events, which were constructed from elements of both spheres in accordance with various possibilities and constraints. Due to the omnipotence of state power and discourse, the aim of everyday life was to lift up hidden values by inserting them into the realm of officiality and thus to conquer new areas for such expression.15

CHORAL FESTIVALS

Choral festivals became popular in the 1960s when local intellectuals exploited opportunities to reorganize amateur folk dance groups, drama clubs and other activities sponsored by houses of culture, government-run institutions that promoted

13 Alena Ledeneva, Russia’s Economy of Favours: Blat, Networking, and Informal Exchange (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 11–38.; Alena Ledeneva, “‘Blat’ and ‘Guanxi’: Informal Practices in Russia and China,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 50, no. 1 (2008): 119–127, DOI: 10.1017/S0010417508000078

14 The term was defined by Julianna Bodó in her research on the society of the Székely Land in the socialist era in the 1980s. In her work she discusses the mechanisms of the maneuvering room of the power and the individuals in various public scenes in society.

15 Julianna Bodó, A formális és informális szféra ünneplési gyakorlata az 1980-as években (Budapest: Scientia Humana, 2004), 56–63, 106–107.

JOURNAL OF GLOBAL CATHOLICISM

12 | The Parish Choir Movement and Generational Festivals in Romania’s Socialist Period: New Community Festivities in Transylvania’s Gheorgheni (Gyergyó) Region

local history, traditions and folk culture. The research and practice of folklore played a crucial role in the organization and these activities, which often involved groups of students, as well. Most villages and towns already had choirs, which competed with singing groups in various regional festivals.16 This case study discusses choir festivals, but the focus is on the reconstruction of the world of parish choirs and parish choir festivals.

Every village in the Gheorgheni region had a church choir led by the local parish organist and cantor.17 The choirs had an important role mainly during holidays, since they often performed songs during Mass on these occasions. In addition to parish choirs, wind bands also played an important role at cultural events: processions on state holidays, funerals, and choir festivals. Many members of the wind bands sang in the local church choirs, too. The composition of the latter was diverse: men and women, workers and intellectuals participated together, and it was not unusual for choir members to be members of the parish church governing council. Before important holidays, they rehearsed once or twice a week to prepare for the Mass. In what follows, church choir festivals and the church choir movement beginning in the late 1980s will be reconstructed, based on the accounts of the participants.

The first church choir festival in the Gheorgheni region was held in Ditrău (Ditró) in 1987. As this festival was a spontaneous and unofficial event, the accounts do not record exactly which three villages organized the first meeting. The participants only remember that the cantors of the three villages—who had been classmates and good friends—regularly kept in touch with each other, and this is how the first, rudimentary gathering was organized.

16 These belonged to the scope of the national folk festival “Singing of Romania.” Csaba Zoltán Novák, “Az egyház, a hatalom és az ügynök Romániában. Esettanulmány a Pálfi Géza dossziéról,” in Az ügynök arcai. Mindennapi kollaboráció és az ügynökkérés, ed. S. Horváth (Budapest: Libri, 2014), 44–45.

17 Cantors in the Unitarian, Reformed and Roman Catholic Churches were employed officially for four, six or eight hours. They provided church music accompaniment to the Masses on Sundays and holidays, and the ceremonies related to the landmarks of human life. Noémi Kicsi, “A kántori szerepkör – a kántori státus interdiszciplináris megközelítése. Maros megyei református kántorok 1948 után,” in Mágia, ima, misztika. Tanulmányok a népi vallásosságról, eds. L. Peti and V. Tánczos (Cluj-Napoca: Erdélyi Múzeum-Egyesület, 2019), 305.

Eszter Kovács | 13 VOLUME 7 ISSUE 1 | WINTER 2022

… these three had been classmates and then they decided that the three choirs should come together somewhere. They met in Ditró, and Zetelaka [Zetea] and joined too. But in the form as it is today, the first one was here in my village in 1988.18

Officially, it began in 1988, but there had been a few in Ditró before, but it was not official, Lövéte [Lueta], Ditró and Alfalu [Joseni], but many of us don’t regard it as the beginning. It was simply that the cantor colleagues came up with the idea of having a good sing, this is how it was arranged.19

In the following years the festivals were organized in the same way as today. After the news spread informally about the success of the meeting in Gheorgheni, another parish choir festival was organized the following year. The organizers regard the 1988 festival as the “official” beginning, because it was preceded by conscious organization work. The choirs of all parishes in the diocese were invited.20

Although the organizers called the festival in Lăzarea (Szárhegy) an “official” one, this word can only be used between quotation marks because they only referred to the conscious organization of the event. From the perspective of the authorities, it was illegal. The assembly was organized by the parishes in an informal way. The organizers did not apply for any permission or support because they were afraid that the performance of religious choral works in a church might not be permitted, or if they had applied for official permission, then they would have been required to include certain official messages and to integrate the event into a larger festival program also determined by ideological constraints. As the event took place inside a church, they hoped that this kind of ritual activity would be included in the “tolerated” category. Thus, the first choir festival was a spontaneously and informally organized one followed by a more institutionalized ecclesiastical cultural event.

18 R8

19 R38

20 These include Borsec (Borszék), Toplița (Maroshévíz), Remetea (Remete), Ditrău (Ditró), Lăzarea (Szárhegy), Joseni (Alfalu), Ciumani (Csomafalu), Valea Strâmbă (Tekerőpatak), Chileni (Kilyénfalu), Suseni (Újfalu), and Gheorgheni (Gyergyószentmiklós).

JOURNAL OF GLOBAL CATHOLICISM

14

| The Parish Choir Movement and Generational Festivals in Romania’s Socialist Period: New Community Festivities in Transylvania’s Gheorgheni (Gyergyó) Region

They didn’t thwart us, it wasn’t reported anywhere officially, they didn’t intervene.21

They organized it, and it could be organized because it was quite limited and because it was in the church and not in the house of culture or a place like that.22

Then I didn’t go anywhere to get permission because if I had done so, then it was, you know, a church event. […] There was only one event like that, the “Singing of Romania,” and that was all. No other cultural events could be held.23

The first meeting had a schedule, which was followed in the subsequent years as well: the guests gathered in the church’s front yard or in the parsonage from where they proceeded into the church, each choir carrying its own flag and banner. The local priest blessed the participants at the Mass, and then they performed the choral works. After agreeing on the order, each choir sang two pieces before the altar. After the performance, they went back to the local parsonage or a place which was suitable for being together, getting to know each other and assessing the program at a reception or lunch. In 1988, although all parishes received “official” invitations, only the choirs of nearby villages participated. Organizers also invited experts on classical music. Between the festivals, choirs practiced regularly to learn the choral works to be performed at the next choral festival.

We begin the Mass at 10 a.m., then we sing our anthems,24 and then comes the procession and the more pleasant part. In the past regime it was easier to arrange it because everyone had a job and fixed working hours.25

The day began with a Mass on Saturday. And for that I tried to invite a priest to preach who had some knowledge of church music so that he could preach to

21 R51 22 R50 23 R8

24 Each choir already had its own anthem. 25 R51

Eszter Kovács | 15 VOLUME 7 ISSUE 1 | WINTER 2022

the singers and give them, to use a modern phrase, some doping, because these people [sang] for free, or as they put it those days as patriotic work, so no one was paid anything for it, they got only oral recognition just like today.26

Invited experts provided an assessment of the performances. The reason for inviting critics was to improve the character of the amateurs’ singing and to develop the choirs’ overall quality. However, not everybody agreed with the presence of the critics and the assessment. Some said that it was not a competition but a festival where they wanted to be together, sing and listen to each other, and they did not want the possible criticisms to frighten away the choir members, most of whom did not have any musical training. As a result, at the choir festival held a year later, the invited critics shared their views concerning the performance of the choral works only with those parish organists and cantors who agreed to be given feedback.

It is a festival-type event, but behind the scenes we discuss which was the best, so there was such professional assessment, too. It was never like a competition, that was the point that everyone should sing from their souls. Of course, some colleagues paid more attention.27

The only professional feature was that the cantors were invited to the parsonage where we were told to be careful here because the soprano was too loud here, but all this in an encouragingly critical tone. It also matters what kind of choir you perform with, because not everyone can read music. But those had a much better attitude at the practice than those who could read music. There was a member who left the factory at 7 in the morning, but we had to be there at 9, and of course he was tired but he still came.28

And then there was a quick lunch for the cantors where I invited the music critics too and told them not to tell the choir if they had sung well or badly but tell us, and only those of us who want to hear the opinion of someone who is 26 R8

16 | The Parish Choir Movement and Generational Festivals in Romania’s Socialist Period: New Community Festivities in Transylvania’s Gheorgheni (Gyergyó) Region

JOURNAL OF GLOBAL CATHOLICISM

27 R50 28 R51

an expert in this, because there were some who said they didn’t want to know and we accepted it.29

Although religious ceremonies held inside churches were treated as tolerated community events, control by the authorities was apparent. Party officials mainly focused on sermons. If the priest preached provocative ideas, he was punished.30 Although choir festivals received (or could receive) Party officials’ special attention, there were no reported cases of violations or punishment.

Interestingly, I wasn’t summoned. It’s true though that no such songs were sung.31

Thus, Party officials did not consider choral works to be provocative, and the participants were careful not to include so-called dangerous songs in the repertoire.

The two works could only be church songs. “All lands praise the Lord,” “Sweet Virgin Mary,” “O salutaris ostriae.” But, for example, “Our Lady, the hope of our country” or anthems could not be sung at all.32

The church songbook we had those days included some songs that were banned so we couldn’t sing them. It had the Hungarian Anthem and we have a lot of songs about the Virgin Mary which is about the country like “The Lady of the Hungarians.” A song which was simply about Jesus was not an irredentist song. Those which were about the homeland, well, those were: “Our Mother Virgin Mary, our patron in heaven,” and it has a chorus that says “Hungary, our dear homeland,” or the song “Our Lady, the hope of our homeland,” because if it’s about the homeland, then that’s the one that King Saint Stephen offered to the Virgin Mary, and that’s not Romania.”33 29 R8 30 These punishments occurred in an informal way at the Militia or the Securitate at Gyergyószentmiklós, usually in the form of physical punishment. References to and remarks of the Hungarian minority or the oppressive regime were regarded as provocative and nationalist utterances. 31 R8 32 R8 33 R8

Eszter Kovács | 17 VOLUME 7 ISSUE 1 | WINTER 2022

The gatherings after the performances were events of special importance, the culminations of the festivals. These gatherings gave the cantors and singers the opportunity to have informal conversations. The atmosphere was pleasant, locals served food and drink to the guests. All of the accounts had positive memories about the atmosphere of the choir festivals, both the performances in the church and the gatherings afterwards. But when they explain what these festivals meant to them, they highlight the gatherings after the performances more emphatically. They looked forward to gathering after the concert, and to entertainment and good company. The gatherings lasted only a few hours, so they could not be regarded as parties, but they still gave a touch of party to the festivals.

The mood is unbelievable because every parish offered [food and drink] to the young ones; of course, it was easier in the villages […]. There weren’t so many bans that could’ve made it impossible to arrange and organize, but there were just enough to make the mood better. As for the sacral part, we performed in the church and it was like it was, but we did it, and then we went downstairs and just relaxed, a bottle of this and a bottle of that, we talked and sang or joked with each other. It made us so joyful that we began to look forward to the next year’s festival.34

The mood, especially at the first festivals, was very good, because we could appear in public, and it was good for us too because we could discuss the things with the colleagues.35

The festivals organized in 1988 and 1989 did not appear in the public place of the government houses of culture, which meant that catering was arranged in an informal way. The female choir members and the cook who served in the church parsonage provided everything necessary for catering. The churchyard, the classroom, and the parsonage provided space for the participants. The food and alcoholic drinks necessary for hospitality were obtained through networks of mutual assistance. 34 R50 35 R8

18 | The Parish Choir Movement and Generational Festivals in Romania’s Socialist Period: New Community Festivities in Transylvania’s Gheorgheni (Gyergyó) Region

JOURNAL OF GLOBAL CATHOLICISM

It’s difficult for the host to cater for so many people in a way that everything goes well. As we were preparing, if you had half a kilogram of coffee, you took it to the butcher, and then you cut off half of a kilogram off the meat and gave it to the grocer, who gave you drink, and this is how you could get drink. […] This is how it went. We always did it privately, you couldn’t go to the house of culture those days. Dinner was in the yard; you asked women and they came, cooked, and served the meal.36

There was kalács [sweet bread] and pálinka, and the women brought cakes. It didn’t cost any money for the congregation. The women brought everything, they made the sandwiches and served them […].37

At the end of the gatherings, the choir leaders agreed where to hold the festival next year, which choral works would be performed, and other technical details. But the choirs and the members were not inactive until the following year. Rehearsals, held once or twice a week, helped preserve the choirs’ group dynamics. The rehearsals themselves as well as the time members spent together after practice brought the choir members together. They saw the choir as their own community where everyone was equal, and nobody had a larger role than the others; they operated on a basis of mutual acceptance and solidarity. On the other hand, the gatherings after the practices also gave opportunity to rewind on a weekday, the members, especially the men, had some beers together or celebrated name-days. The leaders of the choirs were the local cantors, professional leaders of the group. The choirs organized leisure activities and excursions, which gave them the illusion that they had control over spending their own free time. These activities further strengthened and maintained their identity as choir members.

They were harrowing in the backyard of one of the choir members, and then in another choir member’s backyard too, and his harrow broke, and then he saw the other one’s harrow hanging on the wall of the barn, and it broke too, and then this story spread in the whole choir, and they made a model harrow

Eszter Kovács | 19 VOLUME 7 ISSUE 1 | WINTER 2022

36 R8 37 R38

and gave it to him as a present, and it looked like a real one. This is how they joked.38

After the choir practice, the men sometimes go out and have a beer. If someone has a name-day, he brings some pálinka and cakes and offers them to the others.39

I took my choir for an excursion, and those days there were no bus companies like today, and I could get a bus—because those days there were only those state ones—as the director of the house of culture always gave me a certificate that we were going to the “Singing of Romania” festival with the chorus. So, this is how we went on the excursion every year because these shortcuts were always there.40

The parish choir movement that began in the Gheorgheni region in the late 1980s can be regarded as a form of spontaneous and informal self-organization. The presence and active participation of the choirs indicate an understudied informal phenomenon, church-based cultural activities.41 As the Catholic Church operated as a tolerated institution in the late-socialist period, church choirs were also pushed into the background. Nevertheless, much like the dance house movement in Hungary, the church choir movement—which included these spontaneous choir festivals and offered opportunities for individuals to join voluntary associations according to their interests—developed into a self-organizing institution.42 Yet, in contrast with the definition of dance house movements, I do not regard church choirs and the choir movement to be resistance against official discourse and cultural ideology.43 Parish choirs had been an existing part of the institution of the Catholic Church.

38 R51 39 R51 40 R38

41 Dénes Kiss, “Románia a szakralizáció útján. Három romániai egyház profán társadalmi funkcióinak elemzése,” Erdélyi Társadalom 7, no. 1 (2009): 129.

42 László Kósa, Néphagyományok évszázadai (Budapest: Magvető, 1976), 94.

43 András Fejérdy, “Vallási ellenállás Magyarországon a kommunista rendszerrel szemben,” in Kulturális ellenállás a Kádár-korszakban, eds. P. Apor et al. (Budapest: MTA, 2018), 144; László Kósa, A magyar néprajz tudománytörténete (Budapest: Osiris, 2001), 210; James C. Scott, Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990), 17–19.

JOURNAL OF GLOBAL CATHOLICISM

20

| The Parish Choir Movement and Generational Festivals in Romania’s Socialist Period: New Community Festivities in Transylvania’s Gheorgheni (Gyergyó) Region

Likewise, the aims of the movement did not include resistance, only the provision of opportunities for spending free time and for relaxation in accordance with the participants’ interests.

The informality that permeates the choir movement is important for how it determined the way this institution existed, and also for the way it shaped parish choirs’ sense of identity. Corresponding with the characteristics of the “we” group, the choir members from each village belonged to the local choir and, in a wider sense, to the choir movement of the Gheorgheni region, the Catholic Church and the local community. This demonstrates their distancing from the “they” group in spite of the fact that many choir members were active in the local choir, too, with which they participated in the official state cultural competition called “Singing of Romania.” It means that they were members of both communities.

The same distinction is apparent when, disguised as traditional folk song choirs, they officially requested a bus to travel to the festival of the “they” group. But only until the moment when they could obtain support for spending their own free time. From the perspective of local Party officials, we can also see multiple identities at work. When they gave permission to parish choirs to rent a bus, they were members of both the official authority structure and also the local community, the Catholic Church. They supported the informal and illegal activity of the choir, thus expressing their solidarity with that movement.44

As a result, the choir enters the scene of quasi-publicity, and uses the representation of officiality for the creation of their own “our entertainment.” The choirs, together with the choir festivals, offered a strong bond to the members, a safe space where they could operate outside the restrictions of the state and without ideological influence, and, in addition, they nurtured strong professional and personal relationships, not only between the choir members but between the choirs. This strong bond—characterized by acceptance and mutual recognition and tolerance—helped

44 Ledeneva, “’Blat’ and ‘Guanxi’: Informal Practices in Russia and China,” 213–217; Eric Gordy, “Introduction: Group Identity and the Ambivalence of Norms,” in Global Encyclopaedia of Informality: Understanding Social and Cultural Complexity, ed. A. Ledeneva (London: UCL Press, 2018), 218–219.

Eszter Kovács | 21 VOLUME 7 ISSUE 1 | WINTER 2022

the choirs, but also hindered their ability to engage in self-expression and to improve the quality of their singing. This problem could occur in the critical conversations after the performances. Some choir leaders and choirs had to accept that they were participants of an event and an institution providing opportunities for community building, not a competition.45

GENERATIONAL FESTIVALS

In the 1970s and 1980s, a novel form of activity became popular around Transylvania’s Szekler Region (Székelyföld): generational festivals, or class reunions held in local villages. These were a form of celebration of communal and public gatherings with a cultural message and using a special set of ceremonies. As they were new public communal activities, these festivities have no cultural-sociological or social ethnographical definitions determining which habitual activities belonged to these events meetings as festivities.46 Meetings were organized for generations of people in their forties, fifties, and sixties, the most popular of which were those for fortyand fifty-year-olds due to the larger number of participants in this age range. Some volunteers from the given age group who lived in a given village began to organize the meeting at the end of the previous year or at the beginning of the year of the event.47 In what follows, generational festivals of the villages in the Gheorgheni region will be reconstructed based on participants’ accounts.

An organizing committee was established; the main organizers, who carried out the tasks and the purchases were usually people who worked for a place where they could get things easily. Then there had to be someone who could organize it all. The generation festivals were in August, but they met as early as January and began to organize it.48

45 Ledeneva, “’Blat’ and ‘Guanxi’: Informal Practices in Russia and China,” 213–217.

46 Lajos Balázs, “’Ez nekünk jött úgy, hogy csináljuk...’ Kortárstalálkozók. Vizsgálódás egy újkeletű ünnep körül,” in Kriza János Néprajzi Társaság Évkönyve 1, ed. V. Keszeg (1992): 106–107, 132.

47 In the field research, there were no reports of forming organizing committees, like the institution in Csíkszentdomokos, among the organizers, who were called doyens or organizing councils. Balázs, “’Ez nekünk jött úgy, hogy csináljuk...’” Kortárstalálkozók. Vizsgálódás egy újkeletű ünnep körül,” 110.

48 R4

JOURNAL OF GLOBAL CATHOLICISM

22

| The Parish Choir Movement and Generational Festivals in Romania’s Socialist Period: New Community Festivities in Transylvania’s Gheorgheni (Gyergyó) Region

There were generation festivals already in the ’70s. Those worked the same way, for example my father’s generation festivals, that they got things from here and there, and if someone had an older child, he or she had to help with serving or setting the table in the house of culture or the great hall.49

After the first meeting, the organizers met and discussed the tasks to be done every week if it was necessary. The tasks included setting the date, then inviting cultural groups or wind bands so that they would prepare with a program on the given day.50 Cultural programs at the meetings, however, were mentioned by the respondents only to a limited extent if at all.51 The only program they mention is the performance of wind bands52 and the religious songs sung in the church ceremony.

I remember from the first generational festival that they came and said that there would be a generational festival on Saturday, and they wanted someone who could sing nicely, and then there was someone who was working in the foundry, and they gave me this etching picture as a gift, that’s what I remember.

Maybe it was in 1970.53

It was followed by sending out the invitations. Those were invited who had been born in the given village but later moved away, and those as well who had been born elsewhere but were now living in the village. On the day of the festival, usually on a Sunday, those invited met at an agreed venue in early afternoon before the Mass.54 The meeting point could be the yard of the parsonage, but in Szárhegy they met outside the Lázár castle. After greeting each other, they went to the graveyard to remember the deceased members of their generation. It was followed

49 R5

50 Balázs, “‘Ez nekünk jött úgy, hogy csináljuk...’ Kortárstalálkozók. Vizsgálódás egy újkeletű ünnep körül,” 112.

51 Balázs writes that the organizers of the generation meeting in Csíkszentdomokos invited “agitation brigades,” drama groups and choirs to prepare for the event with a cultural program, and they posted advertisements in the county newspaper Hargita Népe and the national newspaper Előre with a list of the invited generation members. Balázs, “‘Ez nekünk jött úgy, hogy csináljuk...’ Kortárstalálkozók. Vizsgálódás egy újkeletű ünnep körül,” 112.

52 The bands greeted the participants of the generation meeting in Újfalu and Remete.

53 R8

54 Keszeg, “Vasárnap: natúra vagy kultúra,” 23.

Eszter Kovács | 23 VOLUME 7 ISSUE 1 | WINTER 2022

by the solemn Mass. In the sermon the members of the generation were greeted and their merits discussed, and the local priest also blessed them. At the Mass, the participants could confess and take the holy communion. After the Mass they went to a designated place where the family members, friends and acquaintances could greet the participants. These greetings usually took place outside. In the era it was customary to give flowers, or the closer family members gave a basket with flowers and an embellished number of the year designating the age. After the greetings, a photo was taken of the group with the baskets, still outside. After the photo, the participants and their spouses usually celebrated the event with a common dinner with live music in the local restaurant or the house of culture, similarly to wedding receptions.

The primary aim of the generational festivals was the communal participation of a large number of people to celebrate their common year of birth. On the day of the generation festival, the ritual acts of the participants, who were paid a special attention, show their attachment to the village and, at the same time, their distance from it. One of the objectives of the meetings was to achieve the highest possible attendance by the members of the generation, and the passive participation of the given village was also a precondition of the festivity. The latter refers to the crowd of “spectators” who attended the processions of the meetings, those who gave flowers and baskets to the celebrated ones. There are differences in the customs and ceremonies of the generation festivals in the regions and even between festivals villages. There are, however, some special features which characterized all generation festivals (in the villages examined) and represented the festive spirit: the celebratory moments of taking photographs, the procession of the celebrated ones with the spectator villagers, the festive garment (folk costume was not in fashion in these years yet), the decoration of the entrance of the house of culture (or the other venue where the evening dinner and reception took place) with pine boughs, and the flowers and flower baskets given to the celebrated ones.55

[…] they sent congratulatory telegrams to the generation festivals, too. My

55 Balázs, “‘Ez nekünk jött úgy, hogy csináljuk...’ Kortárstalálkozók. Vizsgálódás egy újkeletű ünnep körül,” 120–132.

24

| The Parish Choir Movement and Generational Festivals in Romania’s Socialist Period: New Community Festivities in Transylvania’s Gheorgheni (Gyergyó) Region

JOURNAL OF GLOBAL CATHOLICISM

father got 270. But the messages were not read aloud like at wedding receptions.56

The case study examines the obligatory elements and customs of the generation festivals, but it does not focus on the comparative analysis of the similarities and differences between the customs of the meetings in different villages. Instead, it highlights memories which are associated with the social and political context of the era. Such are the narratives referring to the economic crisis and the co-operational solutions of obtaining foodstuff. When describing the composition of the organizing committees, the accounts emphasized the importance of persons who could arrange things. For example, using their connections, they could give badges to the participants, or provide food for the festive dinner. In the villages in the Gyergyó region, the festive dinners were usually held in the local houses of culture—in Szárhegy, in the great hall of the castle—where the local women were asked to cook dinner, but the organizing committee had to provide the food and drink. They resorted to the informal practice of obtaining things through acquaintances, friends, or existing exchange relations.

We could get things even then; you had to be really helpless if you couldn’t get what you wanted. You needed to be in touch with people who worked for a proper place. I went to the distillery in Simon, and what was my luck? The manager of the distillery went to the same school as me, and we knew each other very well, so I went there and he says, if you bring me ten kilograms of meat, you can take as much alcohol as you want. So then I arranged the meat at home and then we brought the alcohol. I took him these ten kilos but then I never had any problems with getting alcohol.57

This example illustrates the instrumental58 feature of the relations with friends and 56 R5 57 R51

58 Ledeneva emphasizes the social nature and the social proximity of human relations and the instrumental feature of relations, or, in other words, the ambivalences in the interest-based use of relations. The substantive ambivalence means that whereas the participants notice the social aspect of the relations (friends, relatives), the outsiders and spectators can only see interest-based contacts. Ledeneva, Global Encyclopaedia of Informality, 9-13.

Eszter Kovács | 25 VOLUME 7 ISSUE 1 | WINTER 2022

acquaintances, in which a long-term and mutual assistance is apparent. Although in the account the two parties mutually benefit from the exchange, the respondent emphasized the social basis of the relationship, the years they had spent at school together.

The other informal form of cooperation which was characteristic of the era was the connection of the generation festivals to church ceremonies because some of the participants had higher positions and were not allowed to attend Mass.

I organized the first meeting for the 40-year-olds in 1976. I went to S. B., and told him that I wanted to do the meeting, and he said, just do it. We did it and had a Mass in the monastery. S. comes to the Mass and tells me: I should confess and take the holy communion because here I can do it but at home I can’t. And before that we went to the monk’s room and told him that he needs to confess and take the communion. It was very important for him, and after this we always organized these meetings.59

This example shows the informal, co-operational and mutual assistance activities of people of the same generation as the organizer finds his former classmate, who has moved away from the village and has a high Party position in his new place of living, and asks him to help him with various issues. One of these is the organization of the generational festival, but the respondent mentions him on several occasions as a person who helps the organizers of the meeting to get jobs or other social advantages.

Whatever complaints you brought to him, he arranged it. Many people from Szárhegy went to him, and they all called him S. For example, I myself had something to arrange. I was learning to be a plumber in Szereda [Csíkszereda], and I wanted to come back to Gyergyó [to work], and there was Comrade Virág, he was the boss where we took the exams, and he didn’t want to sign my transfer60 and didn’t give me the certificate. A day later I saw S., and he asks what are you up to? And I tell him. […] We had a glass of first-class pálinka 59 R39 60 The work placement of the given person.

26

| The Parish Choir Movement and Generational Festivals in Romania’s Socialist Period: New Community Festivities in Transylvania’s Gheorgheni (Gyergyó) Region

JOURNAL OF GLOBAL CATHOLICISM

and a coffee, and he sent me with a comrade to Comrade Virág, and we went to the party secretary in the construction office. Comrade Virág was called to the office and told to sign my certificate.61

Although this case was not connected to the generation festival, it still illustrates a long-term and mutual assistance system. The respondent and S. belonged to the same generation, there were classmates and lived in the same village until the age of adulthood moved them farther from each other both in space and society, but irrespective of this, they exploited the benefits and resources provided by their relationship for the fulfillment of their personal needs. S. helped the respondents find a job, and, in exchange, the organizer of the generation festival—thanks to his status as a member of the church council—established the secret and informal atmosphere for S. in which he could participate in the religious ceremonies even though he was prohibited to do so. In the example, the participants arranged things in the spirit of friendship and the cohesion of their local, ethnic, and religious communities. The instrumental nature of the relationship strengthens,62 but the respondent emphasizes a deeper, friendly relationship and not the fact that it was mutual assistance and a barter, but they helped each other on the ground of common identity and solidarity. In the example, the glass of pálinka and the coffee shows how matters were arranged and how an informal atmosphere and a more intimate relation was created, making it possible to settle the matter.

CONCLUSIONS

The case studies examine two community events which take place in the public sphere. The first one is an informal, self-organizing cultural activity which is linked to the Church and does not associate itself with the official cultural mass movements of the era, being an officially non-existent event. The church choir movement can be regarded as an institution, but the choirs of the parishes in the diocese are also parts of it as smaller institutions. Although the choirs operate in an informal way too, each choir has its own flag and anthem. Their arrival at the festival and the processions (from the parsonage to the church)—albeit a short distance—show the

61 R39

62 Ledeneva, Global Encyclopaedia of Informality, 9-13.

Eszter Kovács | 27 VOLUME 7 ISSUE 1 | WINTER 2022

practice of self-representation of the choirs.

We even made a procession from some public place, sang songs about the Virgin Mary which are usually sung at indulgence festivals.63

We marched through the center of the village here to just like when we were the organizers.64

When the choir festival was in Alfalu [in 1989], the choir from Csomafalva came on horse-drawn wagons. Each choir and village had a leader who decided who marches at the front and who follows him, and this is how we marched and then took our places [in the church]. 65

For the participants the event gave an opportunity for entertainment and being together with the community, providing counterbalance to the dictatorship which controlled everyday needs and the use of time.66 The choir festivals, albeit for a short time, occupy the public space used by the participants, partly on their arrival and partly during the procession. The section of the street, the village center and the route leading to the church become the venues of the festival. Although subconsciously, the celebration had the mood of a festival, with which they tried to recreate a certain form of publicity.67 The same function is apparent in the analysis of the second case study with the difference that generation festivals were considered legitimate by the power. This festivity could be attended by crowds, and there were no rules for participation, it was possible to greet the generation members, meet others and talk to them. Whereas in the first case a small micro-community appeared in space and time, in the second case the local community participated in the celebration together, and the participants tried to include religious ritual elements and forbidden forms of action in the celebration. In both community events the values which people found important but were restricted to the private sphere

63 R51 64 R51

65 R50

66 Gail Kligman, “Népesedéspoltikai, abortusz és társadalmi ellenőrzés Ceauşescu Romániájában.” Demográfia 4, no. 1 (2000): 68.

67 Bodó, A formális és informális szféra ünneplési gyakorlata az 1980-as években, 70–72.

JOURNAL OF GLOBAL CATHOLICISM

28

| The Parish Choir Movement and Generational Festivals in Romania’s Socialist Period: New Community Festivities in Transylvania’s Gheorgheni (Gyergyó) Region

were smuggled in the festive mood of the quasi-public sphere, and the organizers regard the use of informal bartering relations as a basic practice which was necessary for the creation of the festive mood (by obtaining everything necessary for the celebration).

APPENDIX

Code Type of interview Gender Village Occupation Year of birth

R4 personal male Gyergyószárhegy skilled worker 1965

R5 personal female Gyergyószárhegy skilled worker 1970

R8 personal male Gyergyószárhegy church 1957

R38 personal male Gyergyóalfalu church 1953

R39 personal male Gyergyószárhegy skilled worker, church 1936

R50 personal male Maroshévíz church 1954

R51 personal male Gyergyóújfalu church 1950

R55 personal female Gyergyószárhegy skilled worker 1943

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Augustin, Stoica. “Old Habits Die Hard? An Exploratory Analysis of Communist-Era Social Ties in Post-Communist Romania.” European Journal of Science and Theology 8 (2012): 171–93.

Balázs, Lajos. “‘Ez nekünk jött úgy, hogy csináljuk...’ Kortárstalálkozók. Vizsgálódás egy újkeletű ünnep körül.” In Kriza János Néprajzi Társaság Évkönyve, edited by V. Keszeg, 1 (1992): 106–133.

Biró, Zoltán A., Stratégiák vagy kényszerpályák? Tanulmányok a romániai magyar társadalomról. Miercurea Ciuc, Romania: Pro Print, 1998.

Bodó, Julianna. A formális és informális szféra ünneplési gyakorlata az 1980-as években. Budapest: Scientia Humana, 2004.

Eszter Kovács | 29 VOLUME 7 ISSUE 1 | WINTER 2022

Corti, Luis, “Progress and Problems of Preserving and Providing Access to Qualitative Data for Social Research: The International Picture of an Emerging Culture.” Qualitative Social Research 1, no. 3 (2000). https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-1.3.1019.

Corti, Luis, Anette Day, and Gill Backhouse. “Confidentiality and Informed Consent: Issues for Consideration in the Preservation of and Provision of Access to Qualitative Data Archives.” Qualitative Social Research 1, no. 3 (2000). https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-1.3.1024

Fejérdy, András. “Vallási ellenállás Magyarországon a kommunista rendszerrel szemben.” In Kulturális ellenállás a Kádár-korszakban, edited by P. Apor, L. Bódi, S. Horváth, H. Huhák, and T. Scheibner, 779-782. Budapest: MTA, 2018.

Gordy, Eric. “Introduction: Group Identity and the Ambivalence of Norms.” In Global Encyclopaedia of Informality: Understanding Social and Cultural Complexity, edited by A. Ledeneva, 217–219. London: UCL Press, 2018.

Gyáni, Gábor. A történelem, mint emlék(mű). Budapest: Kalligram, 2016.

Keszeg, Vilmos. “Vasárnap: natúra vagy kultúra.” In A fiatalok vasárnapja Európában, edited by Keszeg, F. Pozsony, and T. Tőtszegi, 18-49. ClujNapoca, Romania: Kriza, 2009.

Kicsi, Noémi. “A kántori szerepkör – a kántori státus interdiszciplináris megközelítése. Maros megyei református kántorok 1948 után.” In Mágia, ima, misztika. Tanulmányok a népi vallásosságról, edited by L. Peti and V. Tánczos, 297-322. Cluj-Napoca: Erdélyi Múzeum-Egyesület, 2019.

Kiss, Dénes. “Románia a szakralizáció útján. Három romániai egyház profán társadalmi funkcióinak elemzése.” Erdélyi Társadalom 7, no. 1 (2009): 123-35.

Kligman, Gail, “Népesedéspoltikai, abortusz és társadalmi ellenőrzés Ceauşescu Romániájában.” Demográfia 4, no. 1 (2000).

Kósa, László. Néphagyományok évszázadai. Budapest: Magvető, 1976.

JOURNAL OF GLOBAL CATHOLICISM

30

| The Parish Choir Movement and Generational Festivals in Romania’s Socialist Period: New Community Festivities in Transylvania’s Gheorgheni (Gyergyó) Region

_____.

A magyar néprajz tudománytörténete. Budapest: Osiris, 2001.

Kovács, Éva. “Elbeszélt történelem.” Replika 63 (2007): 41–43.

Kvale, Steinar. Az interjú – Bevezetés a kvalitatív kutatás interjútechnikáiba. Budapest: Jószöveg Műhely, 2005.

Ledeneva, Alena. Global Encyclopaedia of Informality: Understanding Social and Culture Complexity, Volume I. London: UCL Press, 2018. https://doi. org/10.14324/111.9781911307907

_____. Russia’s Economy of Favours: Blat, Networking, and Informal Exchange Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

_____. “‘Blat’ and ‘Guanxi’: Informal Practices in Russia and China.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 50, no. 1 (2008): 118-144. DOI: 10.1017/S0010417508000078

Marton, József. “A gyulafehérvári katolikus egyház a kommunizmus idején.” Studia Theologica Transsylvaniensia 2 (2012): 57-85.

Misztal, Barbara A. Informality: Social Theory and Contemporary Practice. London: Routledge, 2000. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203003626

Novák, Csaba Zoltán. “Az egyház, a hatalom és az ügynök Romániában. Esettanulmány a Pálfi Géza dossziéról.” In Az ügynök arcai. Mindennapi kollaboráció és az ügynökkérés, edited by S. Horváth, 409-425. Budapest: Libri, 2014.

Scott, James C. Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990.

Tomka, Miklós. “Egyház és “civil társadalom.” Vigilia 63, no. 5 (1998): 331–343.

_____. “Vallásosság Kelet-Közép-Európában: Tények és értelmezések.” Szociológiai Szemle 3 (2009): 64–79.

Eszter Kovács | 31 VOLUME 7 ISSUE 1 | WINTER 2022

GENEVIÈVE BAGAMBOULA MAYAMONA, JEAN-CHRISTOPHE BOUNGOU BAZIKA, AND QUENTIN WODON 1

Girls’ Education and Child Marriage in Central Africa: Insights from Qualitative Fieldwork

PART I: THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO

Geneviève Bagamboula Mayamona has been a researcher at the Centre d’Etudes et de Recherche sur les Analyses et Politiques Economiques (CERAPE) since 2005. She holds a Master’s degree in management of small and medium-sized enterprises and strategic foresight from ESGAE and a Master’s degree in international economic relations from Marien Ngouabi University in Brazzaville.

Jean-Christophe Boungou Bazika holds a doctorate in economics obtained in 2001. He taught international economics for 25 years at Marien Ngouabi University in Brazzaville. He serves since 2003 as director of the Centre d’Etudes et de Recherche sur les Analyses et Politiques Economiques (CERAPE).

Quentin Wodon is director of UNESCO’s International Institute for Capacity Building in Africa, based in Addis Ababa in Ethiopia.

32 JOURNAL OF GLOBAL CATHOLICISM

INTRODUCTION

Child marriage is defined as a formal or informal union before the age of 18. As in much of sub-Saharan Africa,2 the prevalence of child marriage remains high in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) in part because educational attainment for girls is too low. Based on qualitative fieldwork, this article looks at communities’ perceptions of child marriage and girls’ education and their suggestions for programs and policies that could improve outcomes for girls.

The article also discusses potential implications for Catholic and other faith-based schools, as well as faith leaders. The issues faced by adolescent girls discussed in this article are prevalent throughout sub-Saharan Africa. This is the region where enrollment in Catholic and other faith-based schools is largest and growing fastest.

In 2020, according to data from the Statistical Yearbook of the Church, 3 34.6 million children were enrolled in Catholic primary schools globally, with 19.3 million children enrolled in Catholic secondary schools and 7.5 million children enrolled at the preschool level. Africa accounted for 55% of all children enrolled in a Catholic primary school globally, and around 30% for children enrolled at the preschool and secondary levels. Under business-as-usual projections, the share of all children enrolled in Catholic schools who live in Africa is expected to continue to grow. Catholic schools and faith leaders simply must confront the issues of girls’ education, child marriage, and early childbearing and find ways to provide better

1 Jean-Christophe Boungou Bazika and Geneviève Bagamboula Mayamona are with CERAPE.

Quentin Wodon is with UNESCO’s International Institute for Capacity Building in Africa. The opinions and views expressed in this article are those of the authors only and need not represent the views of their employers. In particular, they need not represent the views of UNESCO. The data used for this paper were collected when the third author was at the World Bank.

2 Sub-Saharan Africa is now the region of the world with the highest prevalence of child marriage. See Alexis Le Nestour, Oliver Fiala, and Quentin Wodon, “Global and Regional Trends in Child Marriage: Estimates from 1990 to 2017,” Working paper (London: Save the Children UK, 2018).

3 Secretariat of State [of the Vatican], Annuarium statisticum Ecclesiae 2020 / Statistical Yearbook of the Church 2020 / Annuaire statistique de l’Eglise 2020 (Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2022). For an analysis of trends in enrollment in Catholic schools globally, see Quentin Wodon, Global Catholic Education Report 2023: Transforming Education and Making Education Transformative (Washington, DC: Global Catholic Education, 2022).

| 33 VOLUME 7 ISSUE 1 | WINTER 2022

Geneviève

Bagamboula Mayamona, Jean-Christophe Boungou Bazika, and Quentin Wodon

opportunities for girls. A first step is to better understand the issues, and this is main the contribution of this paper for the DRC.4

At the time of writing, estimates from UNICEF suggest that 29% of girls marry as children in the DRC, with 8% marrying before the age of 15 (data from the 201718 Multiple Indicators Cluster Survey).5 Child marriage is a leading cause of early childbearing, defined as a mother having her first child before the age of 18. In the DRC, the share of women ages 18-22 who had a child before 18 is estimated at 25.6%.6 It has decreased only slightly over time. Child marriage also contributes to low educational attainment for girls. According to estimates from the UNESCO Institute of Statistics available in the World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WDI), only 70% of girls complete their primary education in the DRC.7 For lower secondary, the completion rate is even lower at 36%.8

Child marriage, early childbearing, and low educational attainment for girls lead to low levels of human capital. The World Bank’s Human Capital Index9 (HCI) measures the expected future productivity in adulthood of today’s children. It is based on five variables likely to affect future earnings: (1) the survival rate of children past age five; (2) the expected number of years of education completed by youth; (3) the quality of learning in school; (4) how long workers will remain in the workforce,

4 A companion piece is available for the Republic of Congo. The introductions and some of the conclusions in both articles are very similar, so that readers interested in only one of the two studies get the necessary background by reading that study only (i.e., they do not need to read both articles). But the data and analysis are specific to each country. One important conclusion is that many findings are similar in both countries, suggesting these findings may be robust. See Jean-Christophe Boungou Bazika, Wolf Ulrich Mféré Akiana, and Quentin Wodon, “Girls’ Education and Child Marriage in Central Africa: Part II, Republic of Congo,” Journal of Global Catholicism 7, no. 1 (2022): 60-89, https://crossworks.holycross.edu/jgc/vol7/iss1/4/.

5 UNICEF data are available at https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-protection/child-marriage/. For a profile of child marriage in the country based on a previous survey, see Chata Male and Quentin Wodon, “Basic Profile of Child Marriage in the Democratic Republic of Congo,” Health, Nutrition and Population Knowledge Brief (Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2016).

6 Chata Male and Quentin Wodon, “Basic Profile of Early Childbirth in the Democratic Republic of Congo,” Health, Nutrition and Population Knowledge Brief (Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2016).

7 Latest estimate for 2015. https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators

8 Latest estimate for 2014. https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators

9 World Bank, The Human Capital Index – 2020 Update: Human Capital in the Time of COVID-19 (Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2021).

JOURNAL OF GLOBAL CATHOLICISM

34 |

Girls’

Education and Child Marriage in Central Africa: Democratic Republic of Congo

as proxied by adult survival past 60; and finally (5) prevention of stunting in young children.10

The available indicators on the prevalence of child marriage, educational attainment and learning for girls in the DRC, as well as the data for the estimation of the HCI, all predate the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic is likely to have worsened these indicators substantially. This is in part because schools were closed for a substantial period of time, and most children did not have access to quality distance learning (the rate of household connectivity to the internet is very low).11

In addition, as is the case for the sub-Saharan Africa region as a whole, the country is affected by other overlapping crises, including rising food and fuel prices that are leading more households to fall into poverty,12 thereby limiting the ability of parents to send their children to school.

What could be done to end child marriage, educate girls, and more generally provide them with better opportunities? Research has shown that child marriage affects educational attainment as very few girls manage to remain in school once

10 The HCI takes a value between zero and one. It represents the ratio of the expected productivity of today’s children and youth in comparison to the productivity that they could achieve with full education and health. For girls in the DRC, the HCI took on a value of only 0.39. This suggests that in adulthood, today’s children will reach less than 40% of their productive potential. Low levels of educational attainment as well as lack of learning in school contribute to this outcome. While girls may expect to complete 8.8 years of schooling, this is valued at only 4.3 years when taking into account how much children actually learn in school. Child marriage also affects the HCI, as it contributes not only to lower educational attainment for girls, but also to higher risks of under-five mortality and under-five stunting for the children of girls marrying and having children early, as well as higher risks of maternal mortality. See Quentin Wodon et al., Educating Girls and Ending Child Marriage: A Priority for Africa (Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2018). On the link between child marriage and early childbearing, see Quentin Wodon, Chata Male, and Adenike Onagoruwa, “A Simple Approach to Measuring the Share of Early Childbirths Likely Due to Child Marriage in Developing Countries,” Forum for Social Economics 49, no. 2 (2020): 166-79. https://doi.org/10.1 080/07360932.2017.1311799

11 On the impact of the pandemic on learning poverty, defined as the share of children not able to read and understand a simple text by age 10, see World Bank et al., The State of Global Learning Poverty: 2022 Update (Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2022).

12 On the current food and fuel price crisis and its impact in sub-Saharan Africa, see Cesar Calderon et al., Food System Opportunities in a Turbulent Time, Africa’s Pulse 26 (Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2022).

Bagamboula Mayamona, Jean-Christophe Boungou

and Quentin Wodon | 35 VOLUME 7 ISSUE 1 | WINTER 2022

Geneviève

Bazika,

they marry. But vice versa, a higher level of educational attainment reduces the likelihood of child marriage.13

Indeed, in terms of specific policies, the literature suggests that economic incentives to keep girls in schools may work better than other policies for delaying marriage.14 Could this also be the case in the DRC? To provide a tentative answer to this question, we conducted qualitative fieldwork in one urban and two rural areas. The aim was to understand perceptions of child marriage and girls’ education in these communities, and listen to the communities’ suggestions for programs and policies that could improve outcomes for girls, thus contributing to their empowerment in adulthood.15

Specifically, we considered four questions: (1) How much support is there in communities for girls’ education and women’s work? (2) What are the factors leading girls to drop out of school?16 (3) What are communities’ perceptions related to child marriage? And, given the focus of this journal, (4) Is there a role for faith leaders and faith-based schools in helping to end child marriage and promote girls’ education?

13 See for example Erika Field and Attila Ambrus, “Early Marriage, Age of Menarche, and Female Schooling Attainment in Bangladesh”, Journal of Political Economy 116, no. 5 (2008): 881-930. https://doi.org/10.1086/593333. For Africa, see Minh Cong Nguyen and Quentin Wodon, Impact of Child Marriage on Literacy and Educational Attainment in Africa, Background Paper for Fixing the Broken Promise of Education for All (Paris and New York: UNESCO Institute of Statistics and UNICEF, 2014).

14 For reviews of the literature, see Iona Botea et al., Interventions Improving Sexual and Reproductive Health Outcomes and Delaying Child Marriage and Childbearing for Adolescent Girls (Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2017). See also Amanda M. Kalamar, Susan Lee-Rife, and Michelle J. Hindin, “Interventions to Prevent Child Marriage among Young People in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review of the Published and Gray Literature,” Journal of Adolescent Health 59, no. 3 (2016): S16-S21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.015

15 On broader policies for women’s empowerment in the DRC, see World Bank, Women’s Economic Empowerment in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: Obstacles and Opportunities (Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2021).

16 For a discussion of some of the constraints to girls’ education in the DRC, see Laura Bolton, Barriers to Education for Girls in the Democratic Republic of Congo, K4D Helpdesk Report 750 (Brighton, UK: Institute of Development Studies, 2020). On some of the historical roots of low educational attainment for girls, see Marc Depaepe and Annette Lembagusala Kikumbi, “Educating Girls in Congo: An Unsolved Pedagogical Paradox since Colonial Times?” Policy Futures in Education 16, no. 8 (2018): 936–952. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210318767450.

JOURNAL OF GLOBAL CATHOLICISM

36 |

Girls’

Education and Child Marriage in Central Africa: Democratic Republic of Congo