1 SCROLL 2024

Cover Artwork

Front Cover •

Britt Nordquist | Azure Escape, digital photograph

Back Cover •

Britt Nordquist | Lazuline Dreams, digital photograph

Inside Front •

Phoebe Cohen | Oil and water, digital photograph

Inside Back (left to right) •

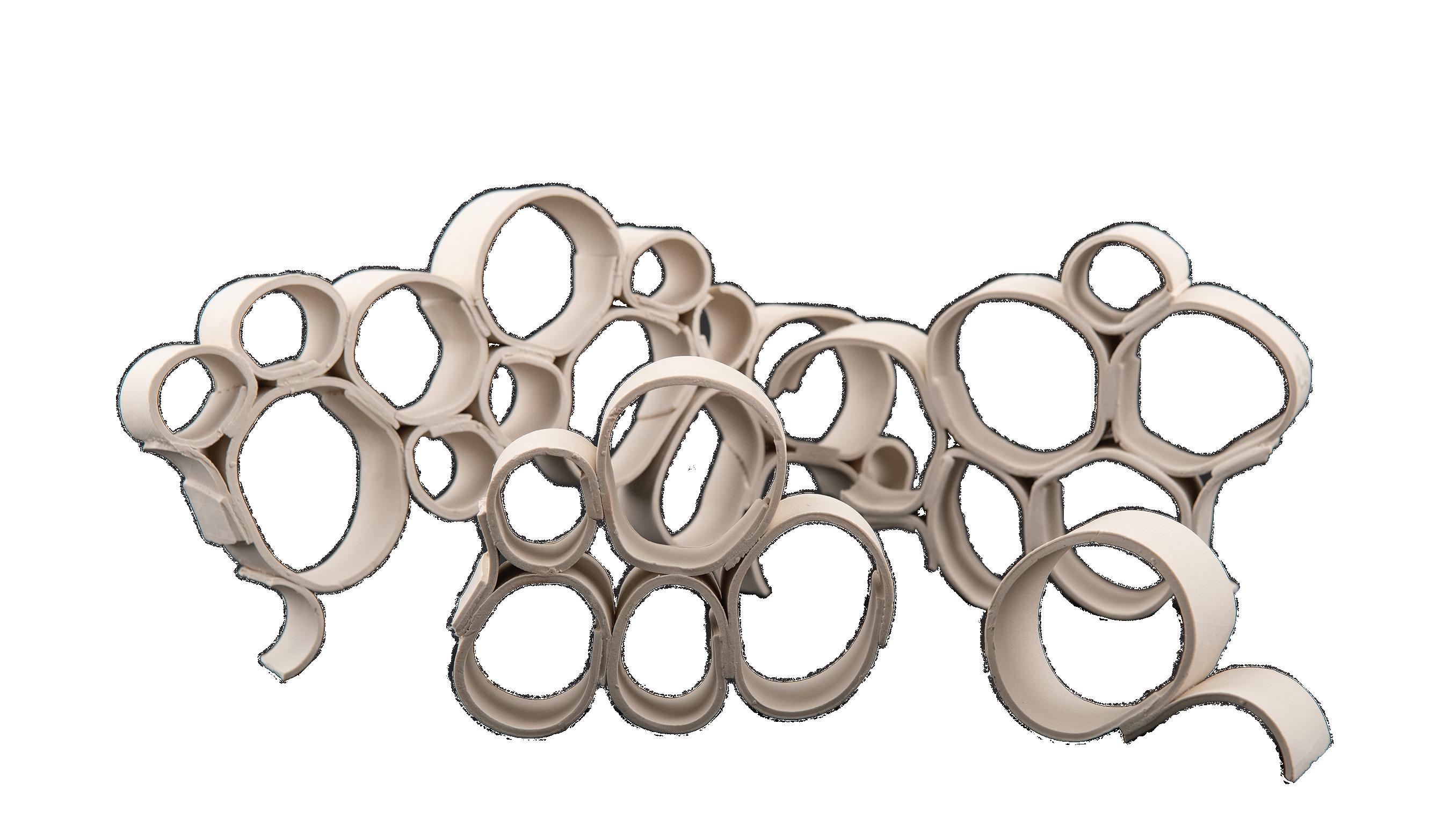

Nell Choi | Cerulean Currents,terra cotta

Marjan McNulty | Lapis Dreams, stoneware

Kira Bardin | Warped Reality, stoneware

Mission Statement

The mission of the Holton-Arms School is to cultivate the unique potential of young women through the “education not only of the mind, but of the soul and spirit.”

Philosophy

Scroll features writings by students of the Holton-Arms School. Many pieces come from classroom assignments across grades 9-12; others come from writing assignments at Scroll Club meetings. In making final selections for the magazine, the editorial staff looks for original, powerful, insightful work as well as a range of genres. They choose artwork that exemplifies the best work of the artists and that also speaks to the ideas or images of the written pieces.

Scroll was produced in the Student Publications Room of the Holton-Arms School. © 2024

2

SCROLL 2024

Volume LXX

editors-in-chief

Alicja Mazurkiewicz • Claire Buchanan

assistant editors

Eliza Dorton • Phoebe Cohen

• Leela Cohen • Betty Rose Bean

• Audrey O’Beirne

photo editor

Britt Nordquist

club presidents

Audrey Meierhoefer • Margaret Sussmann

adviser

Ms. Melinda Salata

Isabelle Evans | Unfurling Vase, earthenware

The Holton-Arms School 7303 River Road • Bethesda, Maryland 20817

3

Authors haikus & tankas Lila Brody ................. 63 Claire Buchanan (3) ....... 62, 63 Mia Gyening ............... 62 Audrey O’Beirne ............ 62 Julia Ryan (3) 62, 63 Natalie Tan ................ 63 fiction Janey Rollenhagen 44 Julia Ryan ................. 73 personal narrative Sophia King ................ 8 Sascha Rhein ............... 12 Sascha Rhein ............... 19 Ella Moore................. 22 Emme Poole 28 Safiya Kurbanova ........... 31 Claire Buchanan ............ 34 Astro Getahun .............. 40 Kendall Adams ............. 47 Charlotte Lipman ........... 53 Sophia King ............... 59 Lucy Berry ................ 65 Charlotte Lipman ........... 71 Caroline Serenyi 73 Lucia Noto ................ Caroline Serenyi ............ poetry Julia Ryan .................. 7 Elise Gledhill ............... 14 Josie Wenchel .............. 15 Lucy Berry ................ 16 Leela Cohen 21 Madison Javdan ............. 26 Phoebe Cohen .............. 27 Avery Phillips .............. 32 Laila Clarke ................ 38 Astro Getahun .............. 42 Anneka Zimmermann ....... 43 Mary Claire Gilbert ......... 50 Julia Ryan ................. 56 Erin Guven 57 Caroline Goldstein .......... 61 Julia Ryan ................. 67 Cecily Brooks .............. 69 Charlotte Lipman ........... 70 Lucia Noto ................ 77 Kayin Bejide ............... 80 Sophia Lekeufack ........... 82 4

Armeeta Moghisi | Study in White and Brown, earthenware

Cecilia Holdo ............. 6-7

Helen Binner ................ 9

Lilly Jamshidi .............. 17

Lilly Jamshidi .............. 18

Cecilia Holdo 29

Sophia Burton .............. 33

Kennedy Kittrell ............ 34

Kennedy Hall .............. 39

Averill Simone........... 44-45

Lana Cvijetnovic ............ 46

Cecilia Holdo ........... 50-51

Angela Mastrostefano ........ 52

Ava Barber ................. 56

Mary Claire Gilbert 57

Cecilia Holdo ........... 64-65

Ella Ross .................. 70 ceramics

Isabelle Evans ............... 3

Armeeta Moghisi .......... 4, 5

Audrey Meierhoefer ......... 10

Sabine Rana ............... 11

Jincheng Zhao 15

Reese Udler ............. 28, 30

Safiya Kurbanova ........... 31

Zahra Rasheed ............. 37

Lucy Hagen ................ 41

Kayin Bejide ............... 49

Sedona Hawkins ............ 54

Grace Westerberg 55

Jincheng Zhao .............. 60

Sophia Royer .............. 61

Leela Cohen ............ 62-63

Ashley Federowicz 66

Leela Cohen ............... 81

Nell Choi ................. 83

Marjan McNulty ............ 83

Kira Bardin ................ 83 collage

Mary Claire Gilbert 21

Armeeta Moghisi | Study in White and Brown, stoneware

Artists photography Britt Nordquist .............. 1 Emme Poole ............... 11 Lily Wexler ................ 13 Addison Burakiewicz ........ 14 Melinda Salata 20 Zoe Nash .................. 22 Addison Burakiewicz ........ 25 Samantha Coulman .......... 26 Samantha Coulman .......... 27 Genevieve Graham .......... 40 Alina Ahmad ............ 42-43 Samantha Coulman .......... 58 Britt Nordquist ............. 67 Addison Burakiewicz 68 Rose Sussmann .......... 72-73 Rose Sussmann .......... 74-75 Sunshine Mitchell ........... 76 Alina Ahmad ............ 78-79 Rose Sussmann ............. 80 Addison Burakiewicz ........ 82 Britt Nordquist ............. 84 drawing

painting

&

5

A Vivid Place

6

Cecilia Holdo | Booze Creek, oil on canvas

The night is simple, my dream is not

I stare endlessly at a wooded grotto

Until I wake and find that

It has encroached my mind

Sought soil, taken root

And become grown, seemingly overnight

Now, I bear a forest in my mind

Its roots are my veins, its dew my blood

Deep in my lungs, I feel the comfort of a long-gone rain

I see trees crowded around a flat-grass clearing

They bow low to the wind in prayer

Grasping branches, soft-touched leaves

Peering over fresh red-top, white-stalk mushrooms

Gathered in a fairy circle atop sleepily bundled earth

All is lit by sunbeams filtered through treetops.

When I sleep at night the forest rises thick,

Yet never breaches the hilltop ring

And though the forest hides itself from my senses

I have faith in the soft scent of earthy loam

The winds strip the warm air off my skin.

The bones of the forest rattle as it draws in breath.

The air tastes of salt.

My forest never conceals itself from me

Even in my waking moments

Its simple scene rises clean from the swamp of my mind

Now, I roam the earth in ceaseless search

For such a place that I am sure exists

If not, how would I know its image?

So clearly I can see it,

How can it be anything but real?

Julia Ryan

Julia Ryan

7

Title of Piece

The Price of a Playground Heist

Sophia King

author

InFirst para text

second grade, I went to the Barrie School. Like most second graders, I spent most of my time on “nature walks” and learning long-division or double-digit multiplication. (It was a Montessori school.) Going to an elementary school where I was encouraged to learn at my own pace meant that I was always able to ask my teacher whatever questions piqued my curiosity.

Patty was my homeroom teacher. She was old as dirt and tried to hide it by dyeing her short bob — which ended right around her bony, protruding cheekbones — blonde. She wore huge, cat-eyed, tortoise-shell glasses that only magnified her wrinkly face and made her look vaguely like a beetle. Her fingers were skinny and would sometimes start to tremble when she got too excited. She was way tall, so her clothes (black tunic tops and loose, flowy pants) always seemed to hang from her withering frame. Compared to the other three homeroom teachers, Patty was the best. Not just because I was her favorite student (she said so herself), either. But because Trish was boring. Her room smelled stale, and it was always sort of dark because her windows faced away from the mid-day sunlight. Unlike Patty, who taught us big, important things like density and geography, Trish read books like Sarah, Plain and Tall or Skylark that made everyone in her class fall asleep. The ones who didn’t were boring people, too, so they don’t even count.

Paula, the third homeroom teacher, was extra nice but in a suspicious way. Her permanent smile

made her cheeks turn a bright, cherry red, and it eventually faded into a grimace by pick-up time. Patty, on the other hand, only smiled when you said or did something really profound like correctly locating the Indian Ocean or remembering to put a tall, purple triangle over a pronoun in a sentence. Paula had a bearded dragon, which I am still convinced was stuffed because it never moved, and an assistant teacher named Jonathan. All the boys liked to play in Paula’s room because Jonathan, one of the few male teachers, would join in their silly games. But for me, that meant that Paula’s room was off-limits. Who would want to waste precious recess time playing with lizards and boys?

Instead, I spent my recess playing with Zakia and Naomi under the huge trees on the fringes of the woods behind the elementary playground. We put on concerts, gossiped, and pretended to be characters in our favorite TV show, The Saddle Club. True to its name, the show followed three girls, the so-called “club,” and their adventures at Pine Hollow Stables, where they rode horses despite the meddling of their spoiled nemesis, Veronica, and the occasional emotional baggage that popped up every few episodes. Since both Zakia and I rode and Naomi wanted to, we liked to pretend that we were acting out scenes from the show.

One spring day, when the ground had just started sprouting patches of grass in between the piles of mulch, the maintenance team had trimmed down a few of the bigger trees as they regrew

8

their thick layer of leaves and blocked too much sunlight. At recess, my class flooded the playground and stumbled upon a discarded pile of three logs, waiting for disposal. At first, no one wanted to move them and risk getting in trouble, but eventually, our curiosity got the better of us and we started making plans of what we would use them for.

Naomi, Zakia, and I wanted to use them as trot poles in our game. Another group wanted to make a gym and use the logs as made-up equipment. This clique was led by Grace Johnson-Scroggins, whom I had known since we were three and three and a half. (She was older). I knew Grace wanted to make a gym because, being sort of close friends, she excitedly told

9

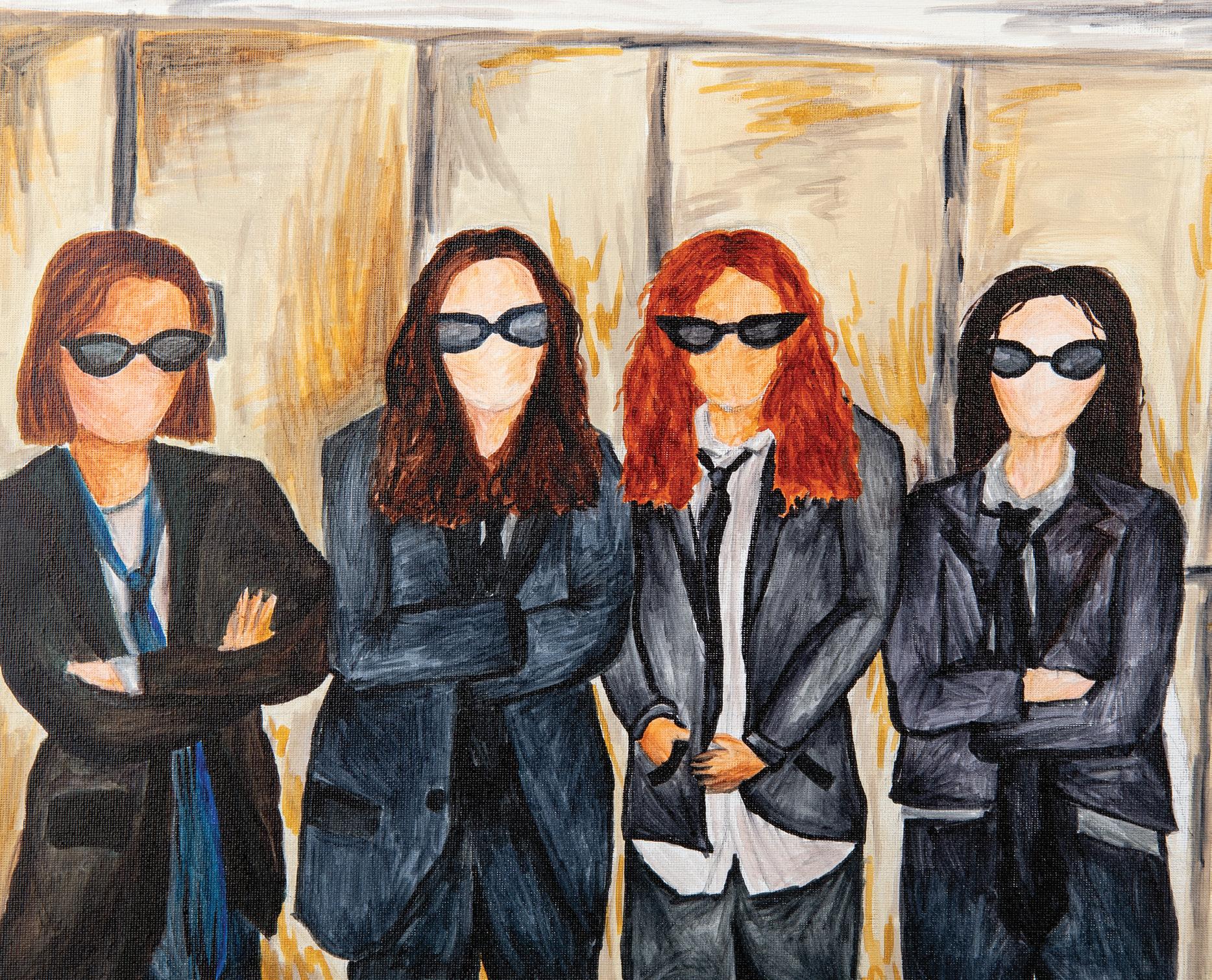

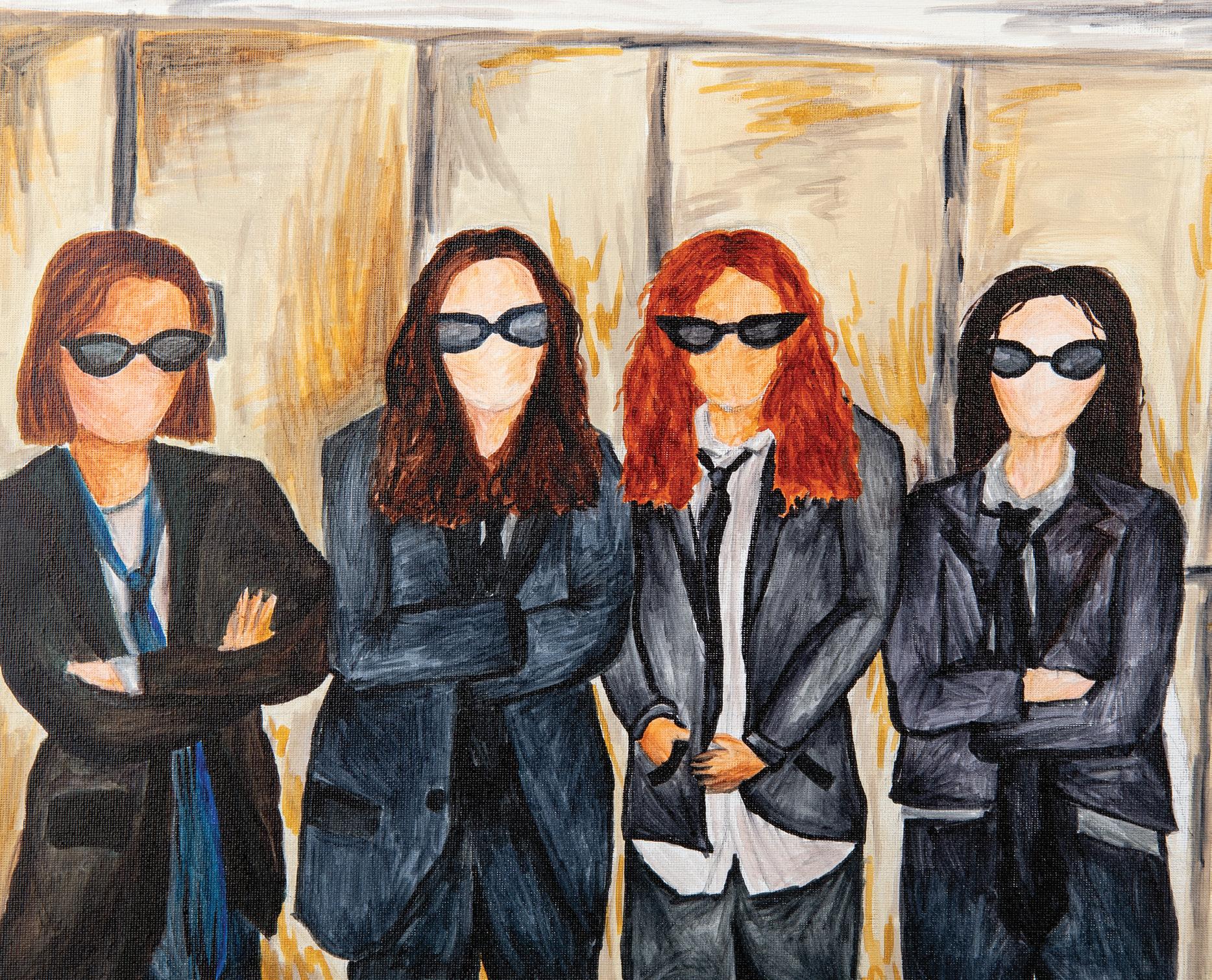

Helen Binner | Women in Black, oil on canvas

me her plan. She even suggested that she could use them with her friends during recess on one day and we could have them on the next.

I didn’t trust her. I had no reason not to, really, but I didn’t. For all I knew, the maintenance team might whisk them away later that evening. This could be our only opportunity to play with these coveted tree logs. And, of course, knowing that there were three logs that someone else wanted, I only wanted to play with them more.

So, I gathered Naomi and Zakia, and we made a plan to take just one for our game. I should note that on reflection, I am aware that we were hatching mischievous plans over discarded branches for a madeup game, and that my willingness to steal from a close friend for the sole reason of wanting what someone else has should be unpacked at a later date.

Nevertheless, just as Grace had finished setting up her “gym,” we tiptoed

to carry the huge log together, and stole away in the noontime sun.

Uproar ensued.

Grace demanded reparations. She marched right up to Patty and tattled right on top of the big hill above the playground, where Patty usually sat and watched with her beetle eyes. Within minutes, Grace, Naomi, Zakia, and I had been asked back into the classroom to talk. We sat on the usual “circle-time” rug with Patty on a stool before us. She asked us what happened. Grace, naturally, spoke first.

To be honest, she told the truth and nothing but the truth. She might as well have sworn on the Bible. She recounted exactly what happened. Sure, there was a tinge of hurt dripping from her words, and betrayal gurgled on her tongue, but she had presented her case and she had done it well.

I shouldn’t have been surprised. I liked Grace because of her matter-of-fact, no-nonsense attitude. She was all short, curly hair and hands perpetually on her hips. She really serious.

Now, as I watched her retell her story from the corner of my eye, her arms folded, and I knew I had lost. There was no talking my way out of this one. No matter how much I liked Patty and she liked me, I could taste the disappointment she would have. So, I did the only It started as a sniffle.

I had never been good at crying on command like Veronica could The Saddle Club. I didn’t even cry

10

when I watched Lilo and Stitch 2: Stitch Has a Glitch when Stitch dies in the plane crash but Lilo revives him with magic of sorts. And that was really sad. But now, my eyes started to get wet, and I knew I had to commit. I covered my face and tried not to make it obvious that I was peeking out from between my fingers to see if it was working.

Grace exclaimed, “Why is she even crying?! She took my stuff!” But Patty put her hand on my shoulder, and that was it. Game, set, match.

I was told to apologize to Grace, which I did eagerly and remorsefully, but the look she gave me was one that haunts me now. She had such an expression of disgust and anger that I had never seen. Gone was the friend that I had made in our blue cots as we learned “sight words” and how to count on our chubby fingers. Gone was the Grace that I had called my best friend at one point.

In that moment, we had become strangers, and my apology was for so many other things besides those silly logs. Now, the tears were real. They were warm and regretful as they dripped down my cheeks. The tears sank into the carpet beneath my criss-crossed legs, and my heart sank with them. But it was too late. I had done irreparable damage, and like the no-nonsense person she was, Grace was having none of it.

It was the first time I felt the weight that the consequences of my own actions had caused outside of simple things with my parents. The first time I realized that an apology wasn’t always enough. To this day, I wish for nothing more than to speak to her. To say anything after years spent in grudging silence. And if I saw her tomorrow, all I would say is, “I’m sorry.”

Emme Poole | Perry the Platypus, digital photograph

Emme Poole | Perry the Platypus, digital photograph

11

Sabine Rana | Perry the Platypus, terra cotta

S

W I N G S

Whatis it about swings? What is it about the little seats, hanging there swaying in the breeze that always pull me to them. Any other attraction at a park is immediately overshadowed by the presence of swings. The strong urge to jump on one, pump my legs, and end up in the sky. Palo Alto, California, was just another place that held a park that held my favorite attraction. Swings. At the ripe age of four, I was already starting my journey to become a swing fanatic, an average lover of, and participant in, the activity of swinging.

I ran ahead of my dad, feet mashing against the mulch. I had just braved the see-saw, another fan favorite. My sister Charlie had beat me down the slide, but I completely forgot the competition as soon as my eyes set upon the far corner of the playground, just touching the fence surrounding the area. The swingset, a hulking figure in the distance, beckoned me. The tall, black metal looked cold even from where I stood. The seats, long plastic things, seemed impossibly high off the ground.

As I rounded the corner of the swing set, hitting the straightaway towards the seat I wanted, a group of kids appeared in the corner of my eye. Three boys. Heads taller than me. A gasp of disappointment sounded from my mouth as I realized that they were headed in the same direction as I was.

My plans will not be hampered by this group of heathens! I thought to myself, picking up my pace.

Two of the three kids were already in the air, feet pushing them higher and higher. I stopped straight in my tracks as, at the peak moment of height, they let go. Flying through the air, they let out a whoop heard all across the playground. Finishing the performance

with delicate style, one of the two landed with a roll, following through to his feet, while the other bashed to the ground, allowing his sneakers to take the brunt of the drop. The first boy, the one with the roll, came back for seconds. I knew this was my time to shine.

Clambering up onto the seat, I flipped off of my stomach and pushed myself into the seated position. The structure seemed bigger than before, the top looming high above my head. The boy had already begun to swing, slowly gaining traction. My tiny legs pumped uselessly against the wind. My dad’s leisurely pace only prompted me to gesture even more vehemently. Finally, a push from behind set me into motion. I was off. I worked my legs back and forth as if it would help me go any faster even though it was out of my hands altogether.

By now, the boy was sky-high, touching the edges of the clouds with his toes. Then he was off, flying through the air. To me, he was Superman. But. But. But I would not be topped. I was the queen of this playground. My territory. I was here first. And it looked like fun. So as my toes reached towards the sky, as the metal chains slid between my fingers, as my breath matched the wind . . . I let go.

Weightlessness is a funny feeling. Nothing holds you, nothing from any direction. Then gravity hits you again, coming back in full force. A split second, and it all comes rushing back. I flew. The sky was endless, but I was not. I had no plan for my fall, no position in which to land that would hamper the blow. So I embraced the ground, accepting my fate. Face first.

12

Sascha Rhein

13 Lily

| Joy ,

Wexler

digital photograph

Ode to Spring

To the freshly green grass; the dappled sunlight

Glistening off the old spire swirling atop the ancient church;

To the bunches of happy daffodils

Sprouting from their bulbs with glee,

Their first glance of the world around them;

To the songs of fierce gales and baby robins, The whistles and chirps of new life;

To the cherry blossom trees

Blooming oh so fast but oh so beautifully, Their delicate flowers as soft as a mother’s touch;

To the breath of sweet, nostalgic air, The memories of past joys and The exciting possibility of new ones;

To spring,

You incredible force of change;

To all that you create and all that you destroy;

To the promise of difference, no matter how extreme, Thank you.

Thank you for gifting our feeble eyes,

Insufficient to appreciate your true power, A reminder of why we breathe.

Elise Gledhill

Addison Burakiewicz| Pink Flowers, digital photograph

Elise Gledhill

Addison Burakiewicz| Pink Flowers, digital photograph

14

Ode to Journaling

Title

I wandered quietly as a question unasked, That lingers at the back of minds and the tip of tongues,

When all at once I saw a pen, A paper lying below.

I seized the pen and clicked it on

As ink dispersed beneath my fingertips

Flowing like the endless ocean

Writing ideas to set into motion

author of poem

Words came to me like wildflowers blooming, Each period was a seed planted,

Paragraphs like fields growing flowers of introspection

Away from everyday dejection

If, because of my writing, my last dollar was spent, I know I would still be content.

poetry poetry poetry poetry poetry

Josie Wenchel

15

Jincheng Zhao| Stories Are Windows into Other Worlds, white earthenware

A Woman’s Greatest Consequence

Women were born to want more.

What a shame.

Women were born to want.

An awful shame.

Women were born.

What an awful, awful shame.

Bosoms and bods, shaped by Guilt, and shame.

Starvation of the soul; Nutrience desired but denied. The price one pays for acceptance is a hefty one.

A woman’s greatest consequence is a collective.

Pent up in layers. Pent up and Pressurized.

With a simple tap along our edges causing us to burst.

Then, when furious eyes swell and coarse throats burn, Will we succumb to the flaws

Of our own expectations.

Years of decrepit moans, and Sickeningly endless rolls of retired baby fat and Shameful chub, and anything but silence Come spilling out and spoiled.

Anger from desire spirals, and hate is spewed.

Venom spilled, blood showered.

The greatest consequence is our fury:

A stick of ruby red dynamite next to a champagnecolored sparkler.

A woman’s greatest consequence is generational. It is uniquely hereditary — Intertwined not by ancestry, but by a common theme:

Suffocation of the womanly spirit.

A greater sense of sisterhood found not in blood, but in The experience.

A story.

Lost, but found

Decades later in an old shoe box;

A picture of your grandmother and some handwritten notes;

Antiques found, maybe an old recipe, maybe a diary —

Anything to make you look in the mirror

And see herself in your eyes.

The greatest consequence:

The silent storytelling of past generations of women.

We share the same nose, but not the same story.

So,

Search, clue by clue.

Creep, and wipe away the dust.

Take a look at your grandmother:

Reddish-purple fingertips tease the years lived,

Smile lines show for time well spent.

Each morning, manicuring thick, yellowing nails

And brushing frail silver hairs ‘till curls go straight and still.

Then, a gentle peek at your mother.

Eye bags like luggage: She bores the weight of many more Before and beside and beyond.

A touch of concealer covers her burden. You see it, though:

How her shade gets

Paler and paler as each day passes by.

To surrender the truth:

Give up the peony-pink nail polish and the Shade-14C concealer.

To reject this reality:

Add an extra glossy coat to finish and splurge on the extra-coverage formula.

16

The greatest consequence:

Erasure of the past, and a longing to do so. To rid oneself of The girl one once was. Maybe.

A woman’s greatest consequence Maybe. Is never knowing Maybe.

What exactly it is

In our brain chemistry or the curves of our tender muscles

Or the curl of our eyelashes or the trajectory of the freckles and moles

Speckled across our bodies

That made us feel in such a Womanly way. Maybe. Maybe. Maybe.

It is strange, isn’t it. From countless faults of womankind should come an answer.

From trials and tribulations should come glistening horizons

Of enlightenment.

The question, still: Where did satisfaction become enough? Why?

The answer, still:

A faceless woman with trembling hands, Worn down, rusty even. Before, beyond and beside. Her. Her. Her. You. Me.

The real question, now: Was satisfaction ever there? Really, there?

The greatest consequence: A thought. The thought: Women were born to want more. What a shame. Women were born to want. An awful shame. Women were born.

What an awful, awful shame.

A woman’s greatest consequence: To want. To want. To want. Beyond, Before, & Beside. Forevermore.

Lucy Berry

17

Lily Jamshidi| Femme en Rouge, oil on canvas

18

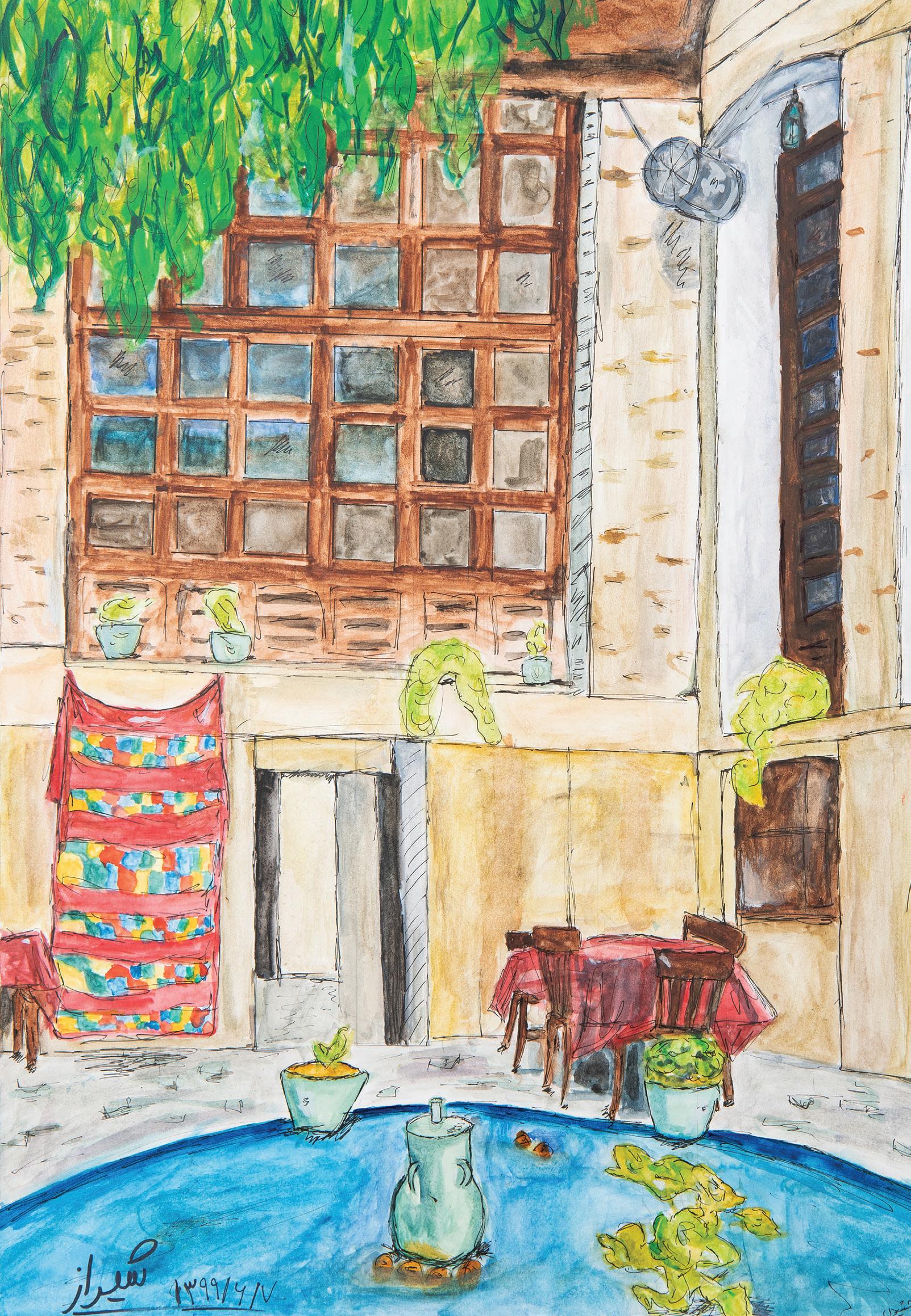

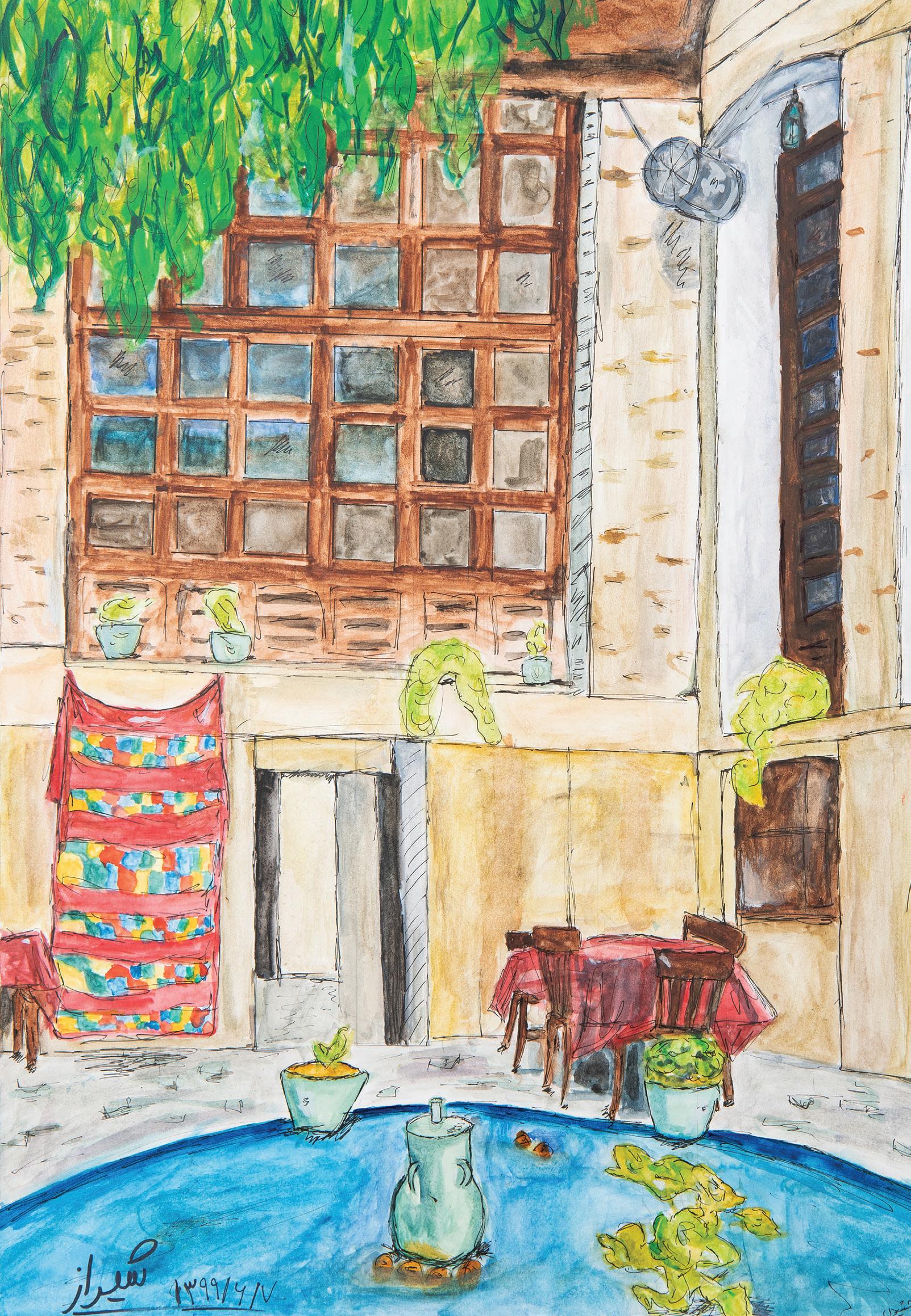

Lilly Jamshidi| Cafe Shiraz, watercolor on paper

War and Laundry

Sascha Rhein

Thebunk room. It was my night off. Having SAT class that evening, I couldn’t go out with the rest of the staff on my night off, so I was stuck back at camp doing laundry.

With class finally over, I slam my computer closed and fall back onto my pillow with a deep sigh. Rolling over onto my side, I open my phone. The screen lights up with a text. “I saved you a plate. Mach Schnell!” He was supposed to be on his night off as well. What is he still doing here? I’m not complaining, though — I would appreciate the company. I let one leg fall off the bed, resting my foot on the floor. Another text comes through, “Hurry up or we are going to eat your dinner.” I let my other leg drift off the side so both my feet rest on the ground. Progress. My pile of laundry in the corner beckons me, but I shake my head at it, daring it to grow any bigger. It can wait. I take my time, pausing to look out over the lake and catch the light of the moon reflecting off the surface, specifically because I have been told to hurry.

The dining hall. The expanse of the room has been cleared to mop and sweep the day’s mess away. Dishpit is bopping, I can hear the music reverberating, carrying through the empty room to envelope me. I’m pulled forward towards the sound, heavy beats thumping against my heart. But it’s my night off, I remind myself, and I don’t have to work there tonight. I instead turn to the left, through the main kitchen, past the knives and ice machine, and into the tiny break room, filled with a table that touches three of the four corners of the room. Blocked into a corner, there he is, and there is

what I have come for. My dinner. A bowl of spaghetti and two meatballs later, I push back the chair as best I can and stand. He has refused to tell me why he didn’t go with everyone else, but I appreciate his presence nonetheless. We parkour over the chairs and above the corner of the table to get out of the tight space, then stack the dishes to be cleaned.

Dishpit. Beats pump over the roar of the industrial washer. Fumes of detergent hit you full in the face as you get closer, the sauna-like air completely surrounding you as soon as you step over the threshold. Heat pushes at the edges, trying to escape. One misstep and you’ll find yourself ankle deep in water of questionable cleanliness. Mist enveloping everything in a crust of stickiness, fogging glasses and matting hair. The aprons, which hang uselessly by the doorway, have never moved off of their hooks. They wouldn’t protect you anyway from the main hazards of dishpit: Owen and David. Learning my lesson the hard way, I have walked away many a night with surprising amounts of Dawn dish soap in my shoes courtesy of David or sopping wet from a jet spray from Owen’s hand on the hose that happened to be aimed my way.

Tonight, I avoid the initial interaction and call to them from a safe distance to inquire how the night is going. As the conversation progresses, I move closer, assuming a truce has been called for the night. Rookie mistake. I glance around trying to find where my night-off buddy has gone, and then I feel it. A stream of water hitting my side. And on my night off, too.

Oh, it is so on.

19

A quick look down confirms it, a giant wet spot apparent in the dark blue sweatshirt I am wearing. Making eye contact with Owen, I smile, very casual. Inside, a flame ignites.

He turns back to his work, satisfied. My eyes remain on his back, hand groping to the side until my fingers find my water cup. I slowly wrap my hand around the cup, feeling its potential. I lift it, testing how it feels in my grip. It’s only three quarters full. That will do.

Owen and I square up face to face, a standoff. He wears a shocked expression, his gray shirt streaked with the remains of my drink. It’s like he’s stuck in a boomerang, head swinging up and down to look at his shirt, then back at me. The silence explodes. A jet of water fires from somewhere behind me.

David.

I gather the rest of my common sense, duck, and run. This is the kind of scene in a movie where a kid stands up at his lunch table and yells, “FOOD FIGHT!”

My night-off buddy appears again, this time against me. Water begins to fly around the room like it’s monsooning. I somehow remember the cup in my hand; its sturdy plastic fits perfectly in my fingers. My feet propel me through the kitchen. A quick pause to refuel, and I realize more cups have been located, but they belong to the enemy.

More water flies.

Laughter, screams.

I refuel again, feet pounding against the linoleum. The bass mimics my heartbeat, its thud reverberating down my spine. Sneak attack and my cup empties again, my only defense gone. The four of us saturate the atmosphere with intense focus, passion proven through airborne liquid. The empty dining hall echoes with

shouts as we slip and slide over the freshly mopped floor and glide back to the kitchen.

outside, plotting my revenge. It drizzles, warm and safe. A spigot appears, my savior. Cup full and heavy in my fist, I am creep around the side ing. If they come out them from the side, cape. I can wait. I one of the large over and in. bucket of my head. with cold my back. to the done yet.

across lines clog of op

a stop, giving in, and turn to face them, daring them to do it again. In Owen’s hand, one last cup of water. I am left to wonder how it has survived this whole time. He raises it, taking his time. It dribbles down over my head, my chin, down my neck, mixing with the rain. I guess I’ll have to do laundry after all. Cups empty, we laugh. Truce.

20

Melinda Salata | Spill, digital photograph

Sleepy

Moon as the

I wandered sleepy as the moon.

Amidst the night, in dreams’ soft tune. Through fields of stars I fled, A journey in the realm of my head.

As shadows dance upon the ground I drift in dreams where I am bound.

Into the distance, I fly, Beneath the bright, starlit sky.

Under the beauty of the starry night, I wander beneath the light. For love, like the moon, waxes and wanes, But, in its glow, its beauty reigns.

Leela Cohen

21

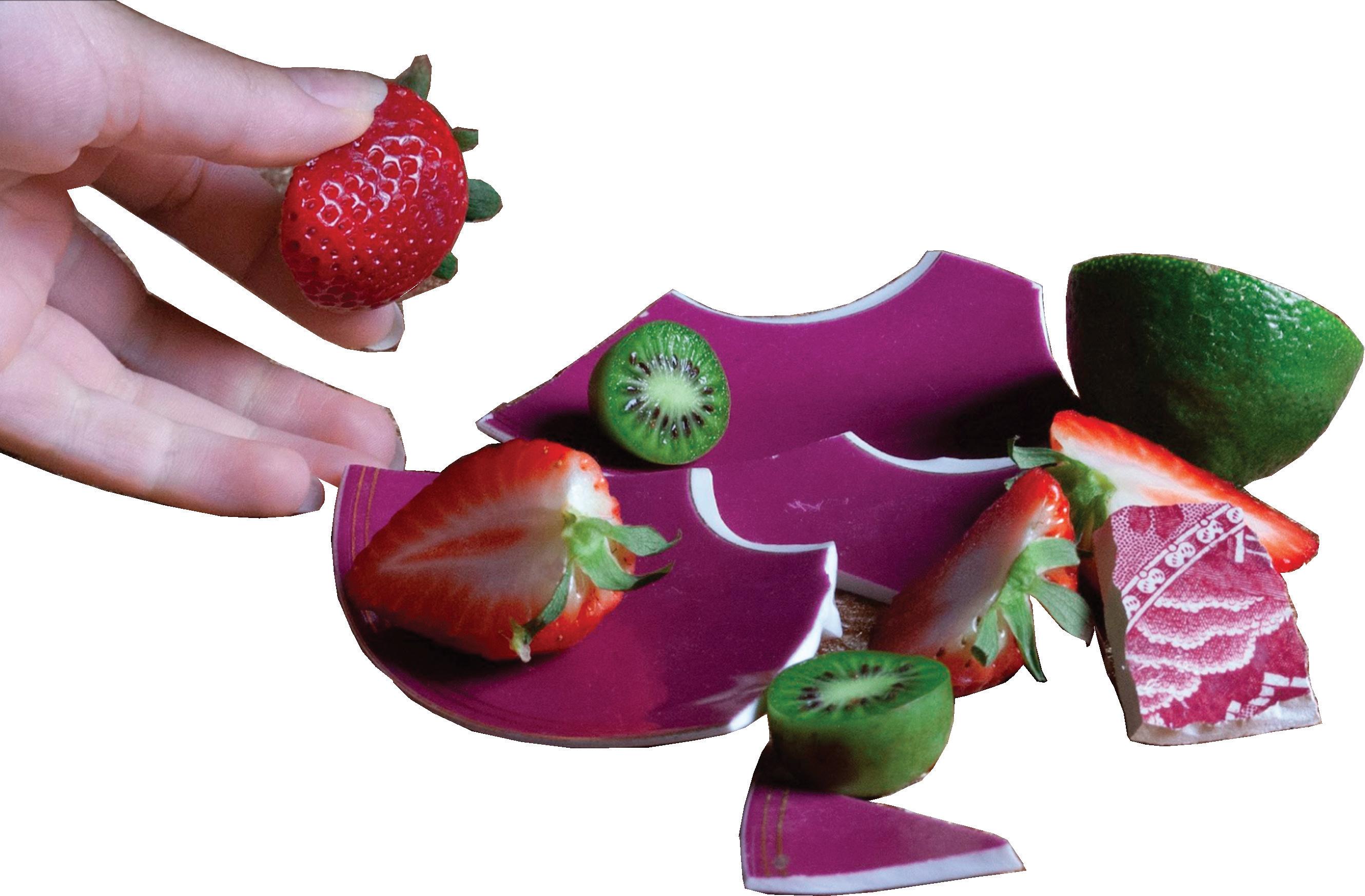

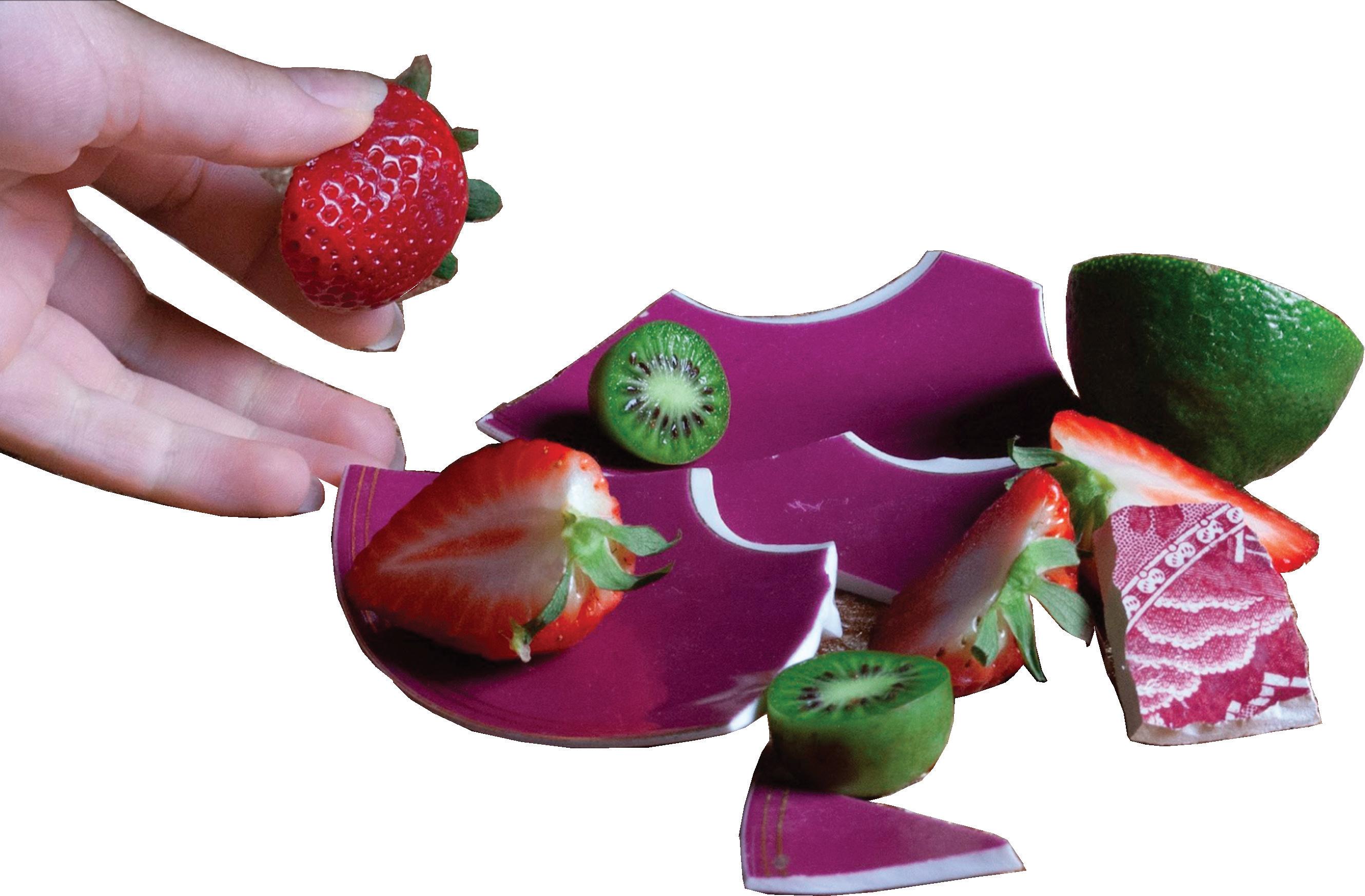

Mary Claire Gilbert | Cruel Summer, oil and paper on canvas

$8.99 Watermelon

Ella Moore

From July through August, Lewis Orchards sells six different types of watermelons. First are sugar babies, $8.99, recognized by their rich dark green color, the most popular watermelon due to their sweet taste. The second is regular seedless watermelon, the classic, also $8.99. Third is another watermelon — I honestly cannot describe to you what makes it so special — but I can inform you that it’ll cost you $10.99. Fourth is seeded watermelon, my least favorite due to its obnoxiously wide cylinder shape that makes it look like it came straight out of a genetic food factory. Those monstrosities also set you back $10.99. Then, there are two types of $8.99 watermelon that are yellow on the inside;

Cinda swears that they have the best taste, but they look unappealing to me. The final watermelons are the baby ones, baby ocelots, which are $7.99, though some are so big that it’s easy to mix them up with the regular watermelons. The watermelons are confusing, and the signs are unfortunately too far for the cashiers, making it easy to cheat. Often I’ll have to ask a customer, “Which bin did you get it from?” or “Is it a baby ocelot?”

22

Zoe Nash | Broken Assortment, digital photograph

Or if I want a tip, I’ll say, “Yum, sugar baby is my favorite.”

I don’t much like talking about watermelon, especially as a Black cashier. You never know what these Poolesvillians are thinking. But talking about watermelon proved to be quite important, particularly on August 18 at 2:30 PM. According to the credit receipts, I was on my 164th customer, not counting cash exchanges, of course. I was trying to weigh a customer’s potatoes when I heard to the side of me a slightly more aggressive exchange than usual.

Laynie said, “Sir, this is $10.99.”

I figured it was just some customer being a jackass about the prices — the rate of our encounter with this particular species of customer is about 10 per 30 minutes.

Laynie said again, “Sir, this is $10.99.”

I turned. As an older employee, I often try to back the less experienced workers.

Customers tend to sense newer prey. I looked at the stuff on the counter: voila, a watermelon. The guy pointed at the watermelon and said, “This is $8.99.”

I looked at the fruit; there were two types of watermelon that everyone mixed up nearly every time. They both had a similar green color, so no one could make out the difference. But when a customer is annoying, I usually just go with the higher price, so I said to him, “This watermelon is $10.99.”

Riley, who had worked here for four years, came over. In her hand, she held her favorite emergency snack of sliced tomatoes covered with a packet of mayo scrounged from the kitchen. She said in her best nasty cashier voice, “Sir, that’s $10.99. Take it or leave it.”

He went silent and just glared. I figured he would accept his fate, so I turned back to putting the price of the potatoes into the register. Then again I heard, “This is $8.99. The sign says $8.99. You cheat! This is $8.99.”

The accusation was repeated over and over and over until it turned into yelling. I looked over: the man’s face was bright red, and his sausage of a finger was out and shaking intensely at Laynie.

Alaira quietly yelled, “Lindaaaaaa,” in an extremely high-pitched voice. Next time we need to summon Linda, we are not leaving it to Alaira.

Riley and I yelled, “Linda!” and she came over.

When Linda’s pissed, you do not want her walking in your general direction. It’s like a bulldog racing towards you, teeth gritted and eyes small. Linda told the man, “You can leave now.”

Damn, Linda was not in the mood. Usually, she would pretend to negotiate, and then she would kick you out. Nope, not today. The man’s words became garbled into what I can only assume were curse words. I made out a “F@#*!” and “Cheats!”

He threw the watermelon across the counter. Travis, one of the four big farmer men that you don’t want to mess with at the store said, “Whhhoooaaaa.”

Linda repeated, “You can leave now.”

The man yelled, “You are cheats! You are all cheats, it is only two dollars difference!”

He held up three fingers. He picked up the watermelon and carried it over to the watermelon section and threw it into one of the wooden crates.

This throw summoned the all-powerful Robert, Linda’s husband. You don’t wanna f@#* with Robert. That man is as sweet as can be, but if you piss him off,

23

you will never again see the light of day. Robert got up in the guy’s face and said, “Now, you can’t do that. I know you are not throwing watermelons in my store.”

I thought he was gonna swing, but Travis held him back. He eventually calmed down, but the guy would not back down to a challenge. He ran over to Robert, shaking his fist, and yelled, “I will fight you, I can fight you.”

An important detail is that this man was probably 5 feet, 8 inches if I’m being generous and maybe 150 pounds soaking wet. Robert could be an offensive lineman if he wasn’t in his 70s. I admire the customer’s boldness, but honestly, he was lucky Billy wasn’t there. Billy is the biggest farmer, and he would’ve absolutely rocked his shit.

Linda said to me, “Press the button.”

The button was hidden under the register attached to the side of the wooden slats. It was supposed to notify the police. The guy gave up on battling Robert and ran back to the watermelon section, pointing to the signs, “It’s $8.99! You cheats. F@#* you!!”

His gesticulations were a beautiful mix of awkward and aggressive, and his arm motions didn’t follow all the way through; he just sharply jutted his arm toward the various watermelons. “Cheats! You are all cheats!”

Arianna yelled back, “Dude, just shut up!”

The guy stormed towards her, and Linda yelled, “Arianna, no!”

Of course, the wall of Travis and Robert stood in the way. I started giggling until Alaira and Laynie looked at me with wide eyes. I suppose this was a serious moment. A guy awkwardly running around a store

pointing at things and flipping off everyone else is a no-laughing matter.

As reassurance, I said to them, “Guys, don’t worry. We have weapons — look at all these canes that old people left behind under the counter.”

One of them had a wooden handle and a metal hawk welded to the top that could do some serious damage. Cinda, who was filming, got right up in the customer’s face, and he flipped her off right in the camera. Customers started making their way towards us, all of them resembling deer in headlights. An old lady said to me, “Can you hurry up? He could have a gun.”

Ma’am, if you really believe your life is at risk, then leave your damn okra and green beans!

The next customer edged gingerly towards my register, despite its being more than twenty feet away from the scene.

“Does this happen often?” she asked.

“Well, one guy called my boss an asshole for not having tomatoes, and another ran around the store after being told that he had to wear a mask, so I guess it’s a relatively frequent occurrence.”

She just said, “Oh.”

The prime customer, seeing that we were continuing our transactions, decided that if he couldn’t save himself from our cheating ways, he would save others. He ran outside and started yelling at people in their cars.

“These people are cheats! Do not come here.”

He stopped a guy who was wheeling his cart in, “They are cheats! Don’t come.”

Travis walked behind him and looped his finger in a circle near his head. The customer with the cart just

24

said, “Ok, thank you!” He then proceeded to make his way over to the bell peppers.

The valiant hero did a few laps around the store, then seemed to tire himself out. Cinda was still faithfully filming. He eventually sat on the watermelon wooden pallet and crossed his arms, smirking, a job well done. Travis, Robert, Cinda, and Linda stood around him. The police had been called, and we couldn’t let him escape. I don’t know what I expected from the police, but they took their sweet time. And when they did finally arrive, they didn’t add anything to the situation. They just wrote up an arrest warrant if the guy came back. He then drove off in a convertible.

Alaira said, “He probably thinks he’s so eff-ing cool in his fifteen-year-old Mercedes.”

I would like to thank that customer for speeding up the rest of our day. I got to leave at 5:50 when normally I leave at 6:30.

The next morning, Linda came up to us and said, “All the watermelons are now $8.99.”

Addison Burakiewicz | Caged Flowers, digital photograph

Addison Burakiewicz | Caged Flowers, digital photograph

25

Beneath the Sun

Beneath the sun’s warm kiss, where waters gleam, Rhythmic waves, an eternal symphony.

The ocean whispers tales of old, In waves that dance, in stories untold.

The fragrance of summer in full bloom, A fragrant spell that banishes all gloom.

The melody of birds chirping in the air,

A chorus that transcends all worldly care.

Cobblestone streets wind through hills of green, And vineyards grace the countryside scene.

Ancient ruins stand amidst the light, Echoes of a past both bold and bright.

Among timeless remains and lush greenery,

Vibrant cities and energetic seas, One cannot remain melancholy

In this breathtaking sanctuary.

Madison Javdan

Samantha Coulman | Radiant Roller, digital photograph

26

April Showers

She felt so calm

On forgotten late April mornings.

Slow Sundays, tea and toast,

She sat on her parents’ porch and listened to the raindrops poke the gutters

As they together washed everything away . . . turned the earth anew.

She was home, and it sure felt like it

When the rain around her was deafening, heard like her own heartbeat.

Sounds like the white noise she used to play

To force herself to sleep, back when this house was just unfamiliar rooms.

Now the sky had paled like faded jeans but she saw the grass gleam greener, brighter than ever before. How unreal.

She was surrounded by wildflowers. Also glowing, a joyful shade of yellow.

She heard the mourning dove hoot in the distance and thought,

How she had never seen her own backyard look more alive.

Phoebe Cohen

Samantha Coulman| Washed Away , digital photograph

Emme Poole

Title of Piece author

First para text

175Carbondale Road is the best place on earth. The little hills and valleys that make up the braids in the rug feel soft as I run my fingers over them, but the warmth barely registers. The light is soft too, filtering through the gauzy drapes lining the wall to my right and the glass doors to my left, dull from the clouds overhead. Yellowed light shines out from the stained-glass lampshade that overlooks the fraying beige couch, now just too small to fit my mom’s three younger brothers and me. Light also spills from the door to the kitchen in front of me, whiter, accompanied by my grandmother and her sister’s grainy voices and the ting sound of copper pots kissing a marble countertop.

The light bounces off the short yellow curls floating a foot above the carpet next to me as Annabelle grips a red and blue clump of clay with her pudgy fingers. When she tilts her head up to look at me, the light slides down her olive forehead and gathers between the layer of blue surrounding her pupils and the glassy curve of her retinas.

“Can we go for a walk?”

Annabelle’s voice pulls me back to the moment.

Her little feet pad on the taupe carpet in the living room, then squish down against the wood in the entranceway, over the thin, patterned rug in our grandmother’s store, then press against the gray stones lining

the floor of the mudroom. The floors here are heated but no match for the late-fall chill that’s settled into Waverly, and they sting our toes. Annabelle pulls on her puffy yellow jacket (she struggles a bit with the zipper, but Montessori is big in our family, so I fight the impulse to do it for her), black gloves, and pink hat, while I determine which of various coats hanging in the mud rack to steal.

The chimes hanging above the door hum when the wind first nips at our noses, and I struggle to squeeze myself into her tiny shoes: what would interest a four-yearold? At her age, I toddled after Bernese dogs like giants, begging my uncles to toss me around the trampoline at the edge of the property for hours. But when I look across the front yard, there’s only a grayish circle of grass and two empty doghouses. The trees alongside the pavement scrutinize us with clay eyes.

We stomp down the steep driveway, stopping to climb atop stone walls, kneel down to delicate clay cottages, and peer at the pottery studio and water tower settled on the plateau halfway down the hill. Finally, when we veer toward the road, I find direction. Thin, jagged stones pierce the ground to our right, outlining a path through the dead leaves, toward the tented greenhouses.

“Come on! Come on! I want to show you something!”

Fluffy blonde eyebrows furrow up at me, and I laugh a little. Light glitters off the fog blanketing Lackawanna.

28

The trees gaze down on us as we bound up the hill, sneakers scuffing over dewy variations of crimson, sienna, and chestnut. Through her eyes, I rediscover how I love the smell of damp bark, the pattern light paints on wooded ground, and the cool air on my skin. I slip in the dirt and accidentally drive a woodpecker off its branch with a squeal. Annabelle runs a cottony finger through the ends of my hair, then pulls out an unreasonable amount of leaves. We meander along the short path this way for minutes.

Halfway up, we follow the detour branching off further into the pines and stop with the pathway at five gray-topped white steps. Annabelle grasps my finger while we crea-eak! up onto the square porch. From up here, the forest stretches out all around us, echoing its symphony of owls, harriers, and sparrows. I lift the tiny body in front of me up and over the railing, so Annabelle can sit at my eye level and watch bucks tiptoe around the uncovered plant beds resting at the

29

Cecilia Holdo | What are You Talking About?, oil on canvas

bottom of the steep steps leading from the compost bins to the glass at the end of the kitchen.

After the deer dart back behind the treeline, and the birdsong fades into the background, I wrap my hands around each of Annabelle’s ankles and swing her around to face me, then around her waist to lift her to stand. She doesn’t speak, but she does smile.

“You wanna jump? I gotcha, I pinky swear.”

She giggles as I catch her and continues for all the time it takes to step across the tiny porch and open the screen door. I’ve always thought about this place as a time capsule, since neither of my grandparents has touched it much since they bought this place in ‘98, and before that, the author living here hadn’t come down to write in years.

A box-and-antenna TV, flowery wallpaper, and dusty desk crowd the small room. I bend down to ignite the heating oven, then settle into the couch with my cousin for a nap.

I’m not sure if we say anything during the post-nap trudge downstairs, and up toward the stone porch hugging the family room, kitchen, and greenhouse-pantry. The chirping and chiming of the woods make way for my family’s chatter and clanging in the kitchen. Corey grabs the handle, then warm air smelling of turkey, pumpkin, and cranberry envelops us.

“You’re back!”

“Did you both have a good time?”

“Come here, Anna.”

“Emerson, grab the ghee for me, would you? Wendy said you would help with potatoes.”

“Oh! You must be so cold, come here, come here!”

I must look in about eight different directions during the second it takes to catch up with the speed of time. When my fingers brush against and tie my old apron around Annabelle, my chest feels warm in a way entirely contradictory to the last few hours I spent outside.

Reese Udler | Harmony in Multiples: A Mosaic of Honeycombs,

Reese Udler | Harmony in Multiples: A Mosaic of Honeycombs,

30

porcelain

The Three Bobos

Safiya Kurbanova

Bobo means “grandpa” in English, but it’s more than just a word for me. It’s a connection to my Uzbek heritage. Growing up in the U.S., I often explained my cultural identity to others. Despite its rich history and vibrant traditions, though, Uzbekistan has remained largely unknown to many. But I’m a hypocrite to say that because I’ve always felt like an imposter with my background.

Even having been born there and taking yearly trips to Uzbekistan, I always felt “different” and “too American.”

This disconnect became prevalent at the beginning of my sophomore year. So like any other normal person, I embarked on a personal journey to share and learn about my heritage through art, leading to the creation of “The Triumph of the Three Bobos.” These clay figurines are symbols of resilience, each capturing a piece of my identity and Uzbek identity that has endured the test of time — a set of three showcasing Uzbek music, cuisine, and memories.

The first bobo, with weathered hands hovering over a traditional Uzbeth Gidjak, symbolizes the enduring melodies that echo through the years. The second bobo proudly cradles a dish of plov, the iconic Uzbek rice and beef delicacy, a symbol of communal gatherings. The third bobo, short in stature like a beloved grandfather, delicately holds a cup of tea — tea, a constant companion

in the Uzbek cultural narrative, a refuge for connection, conversation, and a shared moment of respite, especially from the challenges faced during the Soviet era. Together the three bobos encapsulate the indomitable spirit of the Uzbek people.

In Uzbekistan, you can find these figures almost anywhere, whether displayed on a shelf or in the hands of a kid who will likely break them. So I set out to recreate my own bobos. Crafting these figurines was a deeply personal journey, for I also made them with my late grandpa in mind. With each stroke of paint and curve, I kept in mind my loved ones and all the past bobos before me. So I invite you to join me in celebrating the beauty and strength of Uzbek culture, a legacy my late grandpa cherished.

31

Safiya Kurbanova

|

The Three Bobos, terra cotta

animals with insomnia do not survive in the wild it is not meant for them; it is not meant for us

text text

text text.

text text.

text text.

text text. text text.

Sample poem

would you still believe in me? my dark circles and my rusty jeans

if i had insomnia would i be like you?

last night you got up at 3 am and made bunnies out of boxed cinnamon rolls you claim it was the time covering your hands that gave you your genius that everything is better in the night my father, he disagrees he says he heard the door creak and i imagine he stared at the ceiling until he heard your footsteps down the stairs i wonder if he wondered where you are going he probably knows if you were an animal, would you still wake at 3?

would the time still coat your hand like glue shaking off in droplets like water would you still believe in cinnamon roll bunnies? in rom-coms and mediocrity

text

i am your spitting image; your little girl sometimes i wonder if night is as blind as it renders sense if it would tangle my face into yours and refuse to let go until morning

would i wake up at 3 am and go downstairs to make rabbit-shaped cinnamon rolls?

would my father still stare at the ceiling as my feet pad by?

if we were animals in the wild i’d still love you anyways the night tangling our faces like shuffled cards suits blurring together ‘til they are one and the same

author

Avery Phillips

text text.. text text.

text. text text. text. text text. text text. text text text text text. text text

w y 32

33

Sophia Burton | Fear, oil on canvas

34

Kennedy Kittrell | Road, oil on canvas

Title of Piece

In the Driver’s Seat

author

Claire Buchanan

First para text

I’ve gotten the question a couple times now: Do you drive? Most people ask after they see me hopping out of my mom’s car in the morning despite the fact that I’ve had my license for a while now. I always answer that yes, I drive, but my parents always need both cars for some reason. I’ve asked about getting my own car dozens of times, but the answer never changes: No. You don’t need one.

I tell people it’s so annoying, so embarrassing, so inconvenient. And yes, I’ve felt annoyed and embarrassed and inconvenienced about my driving situation, but to tell the truth, as I sit in the passenger seat of my mom’s car each morning and afternoon, I know deep down I wouldn’t have it any other way.

When I was little, my mom was naturally present for everything — my first steps, my first playdates, my first day of school. As an only child, a companion my own age wasn’t exactly an option; instead, I relied on my mother for anything and everything. She took me everywhere, strapped to her chest like a babbling, drooling handbag.

And then, I had to disentangle and go off to school.

At Beauvoir Elementary School, I could either get dropped off in the carpool line and walk into school by myself or have my mom park in the lot and walk me to my classroom. Naturally, I insisted on having her walk me in every single day. When I was in kindergarten, most kids walked in with their moms, but by the time I hit third grade, I was the only kid

in my grade who didn’t go through the carpool line. Instead, two brunette heads walked through the double doors each morning, one tall for her age and one just plain tall.

Sometimes my classmates teased me, and my first grade teacher expressed her concern about potential attachment issues more than once, but I stubbornly refused to enter the school without my mom in tow. What should I have done, brave the walk from my car to my classroom alone? When I had the option of my mom’s company? Ridiculous.

Of course, things changed as I got older. By the time I entered fourth grade at my new school, Holton-Arms, walking in wasn’t really an option. Plus, I had finally gotten old enough to feel embarrassed, a development that proved both a blessing and a curse. As I hit upper elementary and middle school, everything suddenly felt horribly awkward. I couldn’t possibly be seen or associated with my mom in public despite the fact she still had to drive me everywhere. I would hop out of the car without so much as a goodbye or a thank-you, desperate to seem older than I was to my fellow eleven-yearolds. Walking alongside her felt mildly humiliating, especially when we went to a middle school hotspot location (so, to Bethesda or the mall), especially when I happened to run into someone I knew, especially when my mom insisted on saying hi to that person.

Nevertheless, when I hated my clothes or my friends or my classes, I went to our kitchen table

35

every time. Sitting with my knees pulled up to my chest while my mom typed away at her adjacent desk, I’d take her through everything ruining my life at that particular moment. I was in a friend group, but I didn’t like half the people. Striking out on my own was impossible (obviously), but I had to clench my fists under the table when I heard certain voices at the lunch table. Oh, and someone had a crush on me — maybe. I didn’t like him back — well, maybe I didn’t. If he liked me, then I’d like him back, but if he didn’t, I didn’t like him either.

She listened, offered sage advice taken from the exact same experiences in her own middle school days and watched me confidently reject it with the assumption that she had no idea what she was talking about. I was positive she couldn’t possibly understand what life was really like for a thirteenyear-old girl.

And then, when COVID hit during the end of my eighth grade year, my family suddenly found ourselves together . . . All. The. Time. Despite all the horror stories I’ve heard, my time in quarantine was somehow semi-enjoyable. My door certainly slammed more than once (I recall a fight about scrambled eggs that somehow turned into a discussion of my rapidly increasing screen time), but I always exited an hour or two later, wanting to know what was for dinner or hoping to go on a walk with her before the sun set. I wanted to go back to school, sure, and see all my friends again, and maybe even go on a trip somewhere, but I didn’t feel rushed about it. The pandemic would end when it ended, but for now, my mom and

I had to finish Parks and Recreation and bake our weekly banana bread.

Of course, quarantine did end eventually, and our daily time together returned to car rides and dinners that I increasingly skipped because I “really needed to study.” Back in an in-person environment, the daily trials and tribulations of my life returned as well, and I firmly believed that no one, let alone a parent, could possibly understand me. I still don’t quite comprehend the instinct that convinces me I always know better than my mom, but it soared to an all-time high during my freshman year.

Still, she was always there. The day shit really hit the fan, my mom was in Rochester visiting a friend. The day my middle school friend group had disintegrated. We had been inseparable for years. Our latest fight, though, would be our last.

When I got home, instead of telling my dad, who probably would’ve suggested we just punch each other in the face and move on, I called my mom crying from our basement. She wasn’t just in Rochester for a fun visit — she was there visiting her college best friend, Pam, who had been battling cancer and slowly losing for the past seven years.

We didn’t know it then, but it would only be a few more months until Pam passed away after fighting her disease for far longer than any doctor had predicted. And yet, my mom still picked up and talked me through my tears for nearly three hours. Even through the phone, I could tell she understood.

It’s been a few years since then, and I thankfully haven’t cried in my basement since. I still call my

36

mom after any inconvenience though, no matter how minor. In fact, I just texted her, asking to pick me up early from school because I’m tired and I think I’m getting sick. If I drove myself, I could’ve left already, but I’m secretly looking forward to seeing her in the driver’s seat; I feel too sick for the idea of driving myself to sound appealing.

Even though I complain pretty frequently about those car rides, and even though I’d love to just leave school when I want to go instead of waiting for my mom to get to the front of the carpool line, the truth is that I treasure those moments with her. If my mom didn’t drive me to and from

just us, that I value so much. If I couldn’t tell her about my day or complain about everything that annoys me in the world or see her throw back her head laughing at my stories or beg her for parental gossip, I would probably go insane. I’ve come a long way from the days of forcing her to walk me in each day (take that, Ms. Gillick — I didn’t end up with debilitating attachment issues after all), but I don’t just jump out of the car without a goodbye anymore either. My mom sits in the passenger seat while I drive a lot of the time, but there’s still something comforting about letting her take over and steer for a little bit.

Maybe I don’t need a car of my own after all.

37

Zahra Rasheed | Tightly Wrapped, porcelain

Sunday evening

Sun still bright

Mama says grab the towels

And I know I’m in for a night

For some, hair day is a hop in the shower

But in my house, it’s a family affair

Sample poem

Wafts of coconut, shea butter, and floral suds

With stray curls and coils around the sink

Like a painter with her brush

My mom uses her comb to create style

Slicing her comb to create diverse shaped parts

And using her fingers to make braids of all sorts

Some skinnier than others

And some flat to my head

Either way, I can’t wait till she finishes

So I can see

My crown

After what seems like days of sitting

I feel the end is near

Impatient tears roll down my cheeks like raindrops

While R&B plays on a loop in my ear

She secures the last bead and my energy grows

I run to the bathroom to see my image unfold

Beads with every color imaginable hang on my ends

I swing my hair back and forth to hear the clicks and clacks again and again

My eyes glued to the mirror

I swear I grow two inches from the boost of confidence

My smile grows with each of my mom’s affirmations

Excited to strut into school

Already thinking about my vision for next week

Laila Clarke

text text text text. text text. text text. text text. text text. text text.. text text. text text. text text. text. text text. text text. text text text text text. text text author

38

Reflections,

39

Kennedy Hall

|

charcoal on paper

WhenISaw the Stars

AstroGetahun

40

Genevieve Graham | Solar Eclipse, digital photograph

FirstIrememberpara text

the first time I saw the stars. It was the summer before fourth grade, and I was on my own for the first time, at a Girl Scout camp in Virginia. On the last night, we were walking at night to the dining hall, flashlights in hand, guided by the camp counselors. One of the counselors pointed out the North Star, and I looked up. I had never seen something so beautiful in my entire life. A sky riddled with light, so close I could touch it. I saw graceful Venus sitting among the stars, I saw the waning moon shine so brightly despite barely showing itself, and I saw constellations I’d only heard stories about. I stood there and watched until I had to be called to join the group. At that moment, I felt I understood why people have always looked at the stars. How it feels to experience something larger than yourself, to let it fill you. To let the stars map the way, to find answers in the sky. I had never felt so whole.

Title of Piece author

to let it fill you. To make way together, to find answers within each other. I had felt so whole one other time.

Now, I see the stars all the time, in chorus class, when holding the door, in laughing together. To experience something larger than yourself, to let it fill you. I don't know why it took scientists so long to discover we were made of the same stuff as stars. Both are a part of something bigger, relying on each other. Like the planets, our gravity attracts other people, building our solar system. No constellation is made of a single star, no change is made by a single person

The second time I saw the stars was in the rain. At camp, my cabin plans were canceled because of the weather. Undeterred, my friends and I went in the rain to dance. It went from three people to five, to our entire cabin. Counselors brought their phones to play music, we were so loud other cabins across the camp heard us and joined in. I had never felt so beautiful before, seeing others dancing and everyone’s first instinct to join in. I danced with people I had never met and held hands with strangers to sing together. At that moment, I under stood why humans have always lived in groups. How it feels to experience something larger than yourself,

41

Lucy Hagen| Lucky, porcelain

to be a poet

Poets are not proud, Of hiding between rhymes. Concealing feelings between syllables

Tucked inside the lines.

Poets are not artists, With paintings clear to see. To hide is to be a poet, to conceal is poetry.

So, here I sit. Writing meaning between lines. Waiting here for it to be found. Like I once did find mine.

Astro Getahun

AS

42

Alina Ahmad | Oil on Water, digital photograph

keening

how will your grief become you? who will you be?

how will you hold on to what you had? they shot me into space the earth died beneath me no matter how i rage and cry, i cannot go back so in my breath, i keep a pocket of air cold for you deep in my chest, i grow tendrils spreading aimlessly across realities in some universe, we were together in another, we can be again i only see you in the corners of my vision and in the footnotes of my dreams keep my body warm for me, and i’ll freefall home

Anneka Zimmermann

43

Janey Rollenhagen

Janey Rollenhagen

Thelittle humans never look up at me. They never watch the ants crawl up my intertwining bark, or the blue jay build her nest in my branches, or how my leaves shrivel up in anticipation of the sharp autumn air, clinging on as long as they can, but never long enough. The little humans don’t look because they don’t see what I see. They don’t see the birds fly by in their triangular pack, never leaving one behind. They don’t see the sun rise and set, painting the sky with motley pinks and blues and yellows and purples. They don’t see the speckled stars illuminating the darkened night. They don’t see the shapes of the clouds: sometimes an elephant, or a dinosaur, or a little human, or a tree.

But I think they might look up if they saw all of this.

I miss when I was a little tree. When my bark had grown all but to the length of two arms. Two little human arms wrapping around me. Or a little human back leaning on me, hiding from the eye of the glaring sun. Or a little human hand reaching for a branch as they nimbly ascend my trunk. Because even from their winged air-mobiles with the tiny windows, they don’t look out. I know they don’t. The little humans don’t see the tops of their heads looking down at the world from the ground, or barely noticing it at all. They don’t see the monotonous continuity of their lives that I see from above. They don’t see my world that they aren’t a part of.

I miss the quiet girl who climbed my branches,

whose breath slowed when she saw the blue jay’s nest as the setting sun enlivened the sky. I miss when she would name the clouds and my leaves or the ladybug crawling up her finger. I miss when she refused to close her eyes, terrified that even in a blink something beautiful would escape her. I miss when she would fall asleep, nestled in my branches. I miss when she would tell me about lying in a lavender field and squinting up at the sun — I don’t think she knew I was listening. I miss her smile when she saw the world from my view. I miss when she came everyday until she tried to touch a star and stepped where there were no branches. She had never looked so small.

And then the humans made the talking rectangles that live for them. They watch the blinking lights and stare into another world, but it isn’t a real one. And I wish they would just look up. Because I want to stretch out my leaves to shade and I want to sturdy my branches for climbing and I want to feel two little arms wrap around my trunk in embrace. And I want them to see what I see because they walk and talk and cry and laugh, but they never see. I stand tall and still, except when the soft summer breezes tickle my leaves and the harsh winter gusts fight against my roots. I am forced into idle observation, and yet I’ve seen everything.

Except I haven’t seen Today. Today, a little human drove up in a maroon pickup truck with paint chipping on the edges. He got out and he looked up at me. I had forgotten the stare of a human eye.

L O O K U P

I had forgotten what it was like for a little human to look up. I outstretched my leaves to shade. I steadied my branches for climbing. He extended his hand and ran his calloused fingers along my bark and he smiled. But it wasn’t like how the little girl used to smile. And then more little humans came with their big trucks, and they looked up at me and they laughed. My roots tightened their hold in the soil because these little humans didn’t seem like the girl who once climbed my branches. They hauled sharp machines with grinning teeth from their big trucks. I wondered why they brought their big machines, I wondered why their eyes scoured up and down my trunk. And I thought that perhaps there are some things I don't know.

And then I did.

I knew their loud machines would rumble and tear into my flesh, I knew the grinning teeth would splinter my rough bark with every cut. I knew my branches would shake from the force and my roots would struggle to hold on. I knew that as the cut grew deeper my balance would grow weaker. And I hoped the grass was soft.

There are no more crawling ants or the blue jay who builds her nest. I can’t see the bright colors overwhelm the sky as sunset approaches or the flock of birds cawing by. My roots lay detached and lifeless below the soil.

The humans look down now. They don’t seem so little anymore.

45

| The

Averill Simonc

Last Birch, oil on canvas

From FEAR to FRIENDSHIP

Lana Cvijetnovic | Anxiety, oil on canvas

46

Kendall Adams

“What if I don’t like the food?” and other questions filled my mind as I berated my mother with my concerns. Walking across the street from school, I would look up at my mom, my face filled with fear. Without missing a beat, she would respond in a level tone to soothe my worries centered around the approach of my first year at summer sleepaway camp. And yet, my apprehension for the summer to come only worsened with each question she answered.

And, then, the day arrived. Before my big adventure, my family and I had stayed for two weeks in the Adirondacks in upstate New York as we always did. Maybe the familiar sight of the vast lake and the bright reflection of the sun across its glassy surface as my twin sister, Charlotte, and I jumped in and ruined its perfection, calmed my nerves before my great adventure. Or perhaps the overwhelming scent of pine trees at every moment relaxed my senses. Regardless, my dread for summer camp seemed like a fleeting memory. Or at least it felt like that during those two weeks.

But when we boarded the plane from New York to Maine, all my unease came flooding back. With each step I took, more butterflies filled my stomach, and my legs almost went numb. I had never stayed apart from my parents for more than a single night, so three and a half weeks at camp seemed like it would stretch on for eternity. We landed in Augusta, Maine, and then began the 45-minute drive to camp. All the while, I silently prayed in the back seat that the drive would last forever. I heard only the sound of the car as it glided down the smooth pavement.

I tuned out the music, and I tuned out my parents’ mindless chatter. For those moments, I felt alone in the car even sitting just inches from Charlotte as I sped toward my greatest fear.

Along the way, we stopped at a small roadside store. Typical Maine corner store, made of gray wood, lobster everything covering the walls inside. We picked up a few travel games, decks of cards, and other small trinkets, my parents likely hoping Charlotte and I would be able to share these toys with any new friends we made.

My mind focused elsewhere. Making friends, while important to me, seemed meaningless compared to the fact that I sped toward certain death.

When we turned down the driveway, my final pleas to turn around and save myself were met with deaf ears. My parents reminded me that if anything this would be a good experience and I might have the time of my life. I rolled my eyes, certain they were incorrect.

We drove up to the drop-off area. Cheering counselors in bright red shirts started knocking on the clean glass windows of the rental car. They shouted welcomes and held big colorful signs in the air. I slouched down as far as I could in the seat, hiding from the five pairs of eyes peering into the car, and begged my parents to roll up their windows and speed away.

Ellie and Sierra, the counselors assigned to me and my sister, rushed out with a decorative red sign with the names of our cabin mates and me on it. Their high energy only made me more nervous, still in disbelief about being abandoned in an unknown

47

place. Ellie led Charlotte and me down the long gravel driveway to our cabin. My parents trailed behind, carrying our many bags filled with camp tshirts and our newly purchased games. Ellie’s neverending questions scrambled in my mind: “Where are you from? Isn’t Maine just beautiful? What are you most looking forward to? Have you ever been to summer camp? You’re going to have such a great time!” Our one-word answers did not slow her down. When we got to the cabin, the slamming of the screen door behind us made reality set in.

Ellie showed both of us to our beds. Mine was a top bunk right next to the fireplace, making me smile for the first time since we had set foot in Maine. Ellie’s beginning to help me unpack overshadowed my excitement. That’s when I realized I would have to live out of a small wooden cubby at the foot of my bed for nearly a month. This fact had not yet made it to my list of worries, but suddenly it shot to the top. My parents smiled at me by the door, and Ellie began to usher Charlotte and me toward them for our goodbyes. This bug-, heat-, and sunburn-filled nightmare would be my home for the next month.

Rather than say goodbye, I latched onto my mother’s leg, wrapping all my limbs around her so she wouldn’t leave me behind. After several failed attempts at persuasion, Ellie finally peeled me from my mother. Once Charlotte and I said our final farewells, we watched with longing as our parents walked back up the long driveway we had just come down. Ellie encouraged us to continue unpacking, but we just stared.

When more of our bunk-mates arrived, the small wooden cabin moved closer and closer to chaos. Shoes littered the floor, towels hung on rafters, and t-shirts covered beds. The shouts of fourteen homesick eight-year-olds fill the air, screams for a forgotten hairbrush, cries for an absent mother, and pleas for the comforting embrace of their own beds at home echoed through the dimly lit cabin.

Against all odds, however, Sierra and Ellie managed to wrangle us all and get us to flagpole on time. They explained to us that flagpole was an event that occurred before every meal, where each cabin lined up in front of the flagpole and listened to the announcements. We trekked up the hill, which already felt like a mountain. We lined up toward the far end of the flagpole as the youngest cabin. The smiling faces of teenage girls intimidated me as did seeing the warm embrace of friends who had reunited after a year of separation. Despite the happy scene, my certainty of my misery remained.

We walked up yet another hill to the lodge, a large, wooden structure with a steep stone staircase leading up to the double screen doors. Everyone squeezed through and rushed to get to their table first. I escaped nearly getting trampled by several thirteen-year-olds and reached my own table. Holding back tears, I allowed Sierra to put a piece of pizza on my plate. Charlotte and I exchanged knowing glances of terror, devastation, and worry. I only nibbled at my pizza. I heard laughter, but it seemed distant and disconnected from the whirlwind of emotions engulfing me.

48

That first night, we had an evening activity during which we met our camp sisters. The camp had three divisions, separated by age, and one girl from each division was paired together in a trio of ‘sisters.’ I waited, sitting on the cold concrete floor to hear my name called. When it was, I stood up and walked away from the big group still awaiting the calling of their own names. I sat crisscrossed in a small awkward circle with my two other camp sisters, silently staring at a leaf in front of me and too intimidated to talk to new people so much older than I was. I met their introductory ice breakers and other feeble attempts to talk to me with small nods or headshakes.

Back at the cabin, the counselors announced lights out. We got fifteen minutes of “flashlight time,” where people could read a book, write a letter, or go to sleep. I chose the unspoken fourth option: to cry silently in my bed. I missed my parents, I missed my own bed, I missed my friends, I missed everything. I wanted nothing more than to go home.

Looking back on this memory of the first day of my first summer at camp, I am surprised at how many vivid moments appear in my mind. I thought I would never have to go back there, but I returned for seven more summers after that one, and I even became the smiling teenage girl warmly embracing friends as we reunited after each year of separation.

49

Winter's Night

In the cold of a winter’s night

The moon drapes itself

In a dark velvet cloak

The breeze sings hymns

Of ancient warriors and paladins

Whose bones rest far beneath my feet

The barren trees resemble

The final reminisce of past heroes

With no legacy proceeding

What is a hero; a man at its core

But ash and hollowed, ivory skulls?

I sit in solitude surrounded by saints;

The stars above whisper,

“Look! Look what your kind has become!

The birds no longer chirp, they screech

The rivers no longer flow, they lurch

Man ravages the soil then demands from us ‘more, more!’

How much longer will you leech?”

50

The echoing voice stings my soul

While my icy hands burn like coal

The void of sky silences my calls

Nothingness surrounds me

Except for the vast caps of blizzard peaks

Without a moonlit path

I have no way home.

I am writing

In hope that you may find

My captured soul

For what has replaced it

Festers and molds

And my heart withers in whole

However the voice of the gods

Still rings in my bones

Demanding justice for our sacrilege

Crying out, “Our glory may have been stolen

But our fury never gone.

May in beauty you find our terror

And fear our looming song.

Your king’s crown holds now power to the flame

Of the power used on land nature comes to claim

Mary Claire Gilbert

51

Cecilia Holdo | Nature's Soul, oil on canvas

past vs present Charlotte Lipman

52

Angela Mastrostefano| Ballet Class, oil on canvas

“Girl,

you look like a trainwreck!” Amanda’s voice cut through the free program music playing over Skate Frederick’s crackly loudspeakers as I slowly skated up to her.

Title of Piece author

First para text Past vs. Present Charlotte Lipman

“Gee, thanks.” I rolled my eyes and set my water, keys, phone, and guards on the boards in front of her seated figure, a full Lululemon outfit covered in a giant Vera Bradley blanket with a mini space heater close by.

“You’re only five minutes late today. I’m proud! Take a couple laps, and then you can tell me about practice.”

Mondays at 3:30 — one of my two weekly lesson times with Amanda — were usually when the rink started to get crowded. Even long before rush hour, Rte. 495 was a complete mess (per usual). By the time I peeled into the parking lot and grabbed my skate bag, I had a whopping 60 seconds to lace up both of my boots.

I reached into my vest pockets to grab a pair of gloves. Looking down, I saw a Ziploc bag on top of Amanda’s overflowing purse. Craning my neck to see its contents, I discovered it was full of sliced cucumbers and green grapes. “Can I have some? Just one of each and then I’ll go!”

Amanda looked up from her phone to raise an eyebrow at me. I responded by opening my mouth and looking at her expectantly. She scoffed and reached into the bag to grab two pieces of produce in her manicured fingers, putting them on my tongue. I smiled at her with a full mouth and took off to start my typical warm-up. Half a lap of forward slaloms, then switch to backward, then do the same for powerpulls and crossrolls. After the basics were done, I stretched my hips until I heard a sickly crack on each side. A quick arch to shake out my back after an hour of driving, and I was finished. My favorite and least favorite part of the lesson was here.

Having Amanda on Monday afternoons meant that the two of us could debrief my weekend practice, which I had barely thought about since getting off the ice the day before. I typically spent 35 percent of the hour talking about random things, 40 percent discussing synchro, and 25 percent actually letting Amanda coach me through drills. Six years of working together meant we had established a rhythm.