P Ō 'AI PILI Kaupō Community Newsletter

Publisher: Kaupō Community Association, Inc.; Editor-in-Chief: Kamalama Mick; Copy Editors: Kalani Thompson, Georgia Pinsky, Tama Starr; Editor’s Assistant: Kauwila Hanchett; Graphic Designers: Kauwila Hanchett, Kamalama Mick; Contributors: Kaupō Community Association, Inc. (KCAI), Maui Nui Makai Network, Aldei Kawika Gregoire, Rachel Kingsley (‘Alalā Project), Tara Apo, Kau’i Kanaka‘ole (Ala Kukui), Sheila Mae Uluwehi Roback, Kamalama Mick, Jethro Canela, Aunty Dorothy Brewster and Smith ‘Ohana.

PŌ‘AI PILI SOLICITATION FOR CONTENT: If you have a story, letter, photograph, announcement, or article you’d like to see published in a future issue of Pō‘ai Pili, we’d love to hear from you! Content is due one month prior to our distribution date. For our next issue, please send submissions to poaipili@gmail.com no later than March 1, 2023.

The views and opinions expressed in this newsletter are those of the authors and contributors of the various articles, and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of KCAI, or the opinions of KCAI’s individual board members. All content is meant to be positive and is not intended to malign any religion, ethnic group, club, organization, company, or individual.

He Hulumamo: My Legacy

Cover Photo: Kauwila Hanchett. A Kaupō winter sunrise paints Haleakalā a rosy red.

Huliāmahi in Kaupō

Noenoe Nights

A Walk Through Kahakapao Dorothy Kauionamauna Keliikoa Brewster

He Hulumamo: My Legacy

Cover Photo: Kauwila Hanchett. A Kaupō winter sunrise paints Haleakalā a rosy red.

Huliāmahi in Kaupō

Noenoe Nights

A Walk Through Kahakapao Dorothy Kauionamauna Keliikoa Brewster

Kaupō is a breathtaking land of beauty, power, and wonder. Living here has taught me so much: there is a lesson to be learned in every swaying tree, every rustling blade of grass, every curving wave. Since my early childhood, I have watched the seasons turn, and felt my heart settle into the rhythm of nature.

Few people have the blessing of being close to nature in the way we are—of feeling the wild earth beneath their feet; of seeing the stars glitter above, the glare of city lights absent; of gazing down the windswept coastline where only nature dwells. We are lucky, and I am grateful every day that we can be here, surrounded by nature’s freedom.

I am proud to present 2023’s first issue of Pō‘ai Pili! As we enter our second year of publication, we are excited to share more cultural and historical articles; stories and writings from residents; updates from our community organizations; and so much more! As always, we’d love to hear from you; please reach out and let us know what you’d like to see in these pages!

Kamalama

Mick

“Kaupō is a breathtaking land of beauty, power, and wonder...I am grateful every day that we can be here, surrounded by nature’s freedom.”

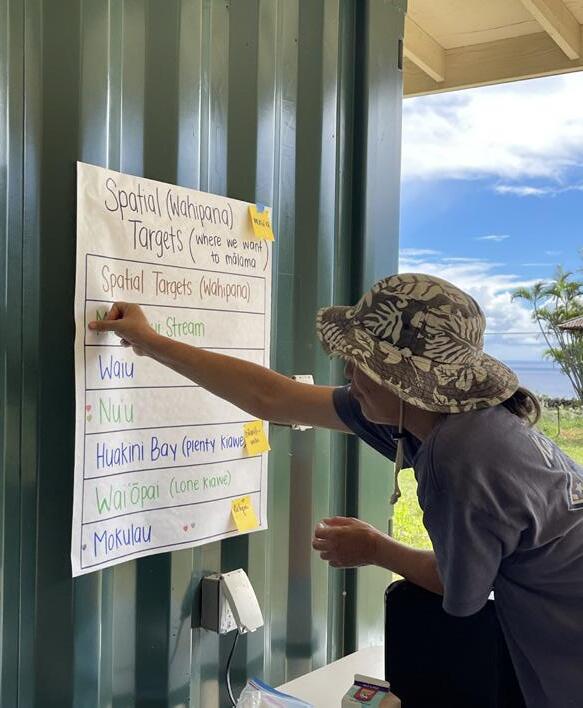

Smith. The plan outlines natural and cultural resources and places they wanted to mālama and their vision for a healthy Kaupō moku.

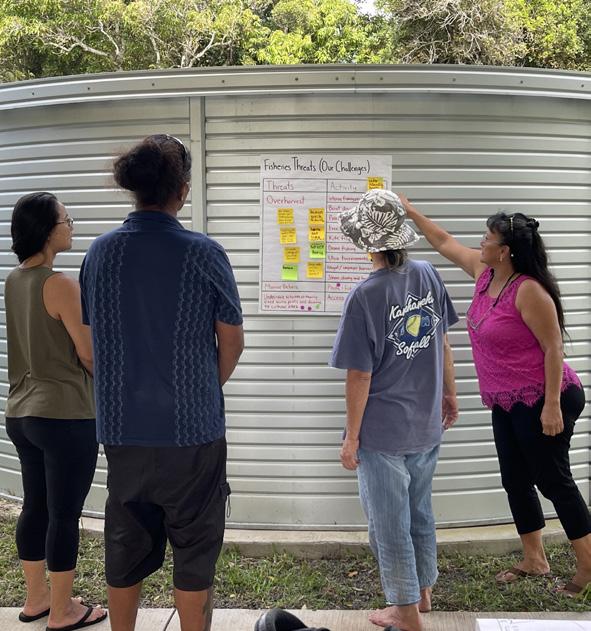

Kaupō gap was clear the morning when the ʻAha Moku O Kaupō-led group met in the Emergency Hub at the newly renovated Kaupō School campus on November 12, 2022. Hosted by the Kaupō Community Association Board, residents and descendants of Kaupō were led by Lyons Cabacungan and Maui Nui Makai Network partners as part of the Maui Hikina Huliāmahi Initiative.

The Maui Hikina Huliāmahi Initiative was created to unite the East Maui community around shared vision for their place and elevate the voices of East Maui lawaiʻa and residents in regional makai (marine) management planning across the four moku of East Maui – Kaupō, Kīpahulu, Hāna, and Koʻolau. The process began in 2019, when several East Maui communities committed to work together to manage their beloved places. Aha Moku O Kaupō was one of the community groups who developed a Mālama I Ke Kai Community Action Plan under the leadership of Alohalani

At the Kaupō meeting the group reviewed, edited, and recommitted to the Community Action Plan. They prioritized fishery species, like ʻopihi and moi, and threats to those species like overharvesting; learned about marine management frameworks; and began discussing ways to manage ʻopihi harvesting. At lunch the group heard from Maui Nui Makai Network community members about makai management in their respective moku.

Scott Crawford of Kīpahulu ʻOhana spoke about the Kīpahulu Moku Community-Based Subsistence Fishing Area proposal that is poised for public hearings this spring. Claudia Kalaola shared Nā Mamo O Mūʻolea’s efforts over the past 14 years to monitor and manage ʻopihi with a voluntary ʻopihi rest area. Jerome Kekiwi Jr. of Nā Moku Aupuni O Koʻolau Hui described his community’s efforts to develop a Community Action Plan and a fisheries management plan. All three groups are co-leading the Maui Hikina Huliāmahi Initiative.

The Network will continue to convene communities throughout early 2023 with the goal of bringing all East Maui participants together in early summer. Email coordinator@mauinui.net to join the effort.

In the recent general election, Maui Nui celebrated the passage of the historic Charter Amendment for the Maui County Community Water Authorities, voted in by an overwhelming majority. For East Maui residents, this is the next chapter in a decades-long battle to protect local streams and communities.

The original resolution, proposed by East Maui Council member Shane Sinenci, sought to establish an East Maui Community Water Authority to address many of the concerns raised by community members, not the least of which is the prospect of a Canadian Pension Fund acquiring the East Maui water leases for the next 3050 years.

With the encouragement of management staff in the Mayorʻs office, however, the resolution evolved into its current Countywide version. It creates the framework for communities across Maui Nui to establish regional community boards with regional directors to manage and/or acquire the water collection and delivery systems in their area, which have long been controlled by private corporations.

The Water Authorities fill a big gap, because currently the century-old water delivery systems Maui Nui depends upon are not being adequately maintained to promote water security. The Water Authorities would provide for the efficient management and public control of these old plantation systems; investment in aging, leaky infrastructure to reduce water waste; and adaptation of water delivery systems for the 21st century and a changing climate.

Regional community boards bring the people who are most familiar with their ‘āina into decisionmaking, incorporating place-based and generational knowledge into resource management. The board selects a regional director and reviews and approves a long-term watershed management plan and watershed-related programs and priorities, along with other environmental and operational reports. The Water Authorities will also have grant writers, community liaisons, water system technical analysts, and other necessary staff to manage water collection and delivery systems.

As a public entity, the Water Authorities are eligible to obtain significant private, state, and

federal funding to manage and upgrade the water delivery systems. Water delivery revenues will be used to maintain operations and infrastructure and implement watershed restoration programs.

The charter amendment also establishes the creation of an East Maui Community Board to pursue the acquisition of the East Maui water leases. Currently, the only applicant for the leases is Alexander & Baldwin (A&B) and its subsidiary, East Maui Irrigation (EMI), which Mahi Pono—owned and controlled by Public Sector Pension Investment Board (PSP), one of Canada’s largest pension funds—owns a 50% stake in.

Council will appoint members. Once established, the Board will begin recruitment efforts and hire a Regional Director. The Board and Director will need to work with the State to determine the requirements for an intergovernmental agreement granting the East Maui water licenses to the Authority. To assure that no interruption of service will occur, the Authority will also need to negotiate an agreement with A&B and EMI to access the portions of the system located on their privately owned land.

However, if that fails, the Authority can obtain use of the system through eminent domain. Within the next year, it is also feasible that the Nā Wai ʻEhā community may pursue the creation of a regional board for their area and seek to purchase the Wailuku Water System. The Authority will also work with DLNRʻs Division of Forestry and Wildlife to coordinate watershed management programs.

The East Maui Community Board will be comprised of eight residents who live in the East Maui water license areas - Huelo, Honomanū, Keʻanae, and Nāhiku; one domestic and one agricultural resident from the water service area (Upcountry); and a representative of the Hawaiian Homes Commission. The mayor will appoint four members— one from each lease area—and the County Council will appoint the rest. Other communities may establish regional boards by County Ordinance.

Now the real work begins. Applications for the East Maui Community Board seats are now open and the Mayor and County

It will likely be a few years before the East Maui Community Water Authority obtains the East Maui water licenses, but the process has begun and voters have expressed their desire for local control of our water resources.

Those interested in applying for seats on the East Maui Board may contact Councilmember Shane Sinenciʻs office at (808) 248-7513.

Tara Apo is a streams organizer with the Sierra Club Maui Group and studies Sustainable Science Management at UH Maui. She currently serves as Vice President for the Kaupō Community Association, Inc.

“Regional community boards bring the people who are most familiar with their ‘āina into decision-making, incorporating place-based and generational knowledge into resource management.”

By Aldei Kawika Gregoire

By Aldei Kawika Gregoire

In the mid-1800s, residents of East Maui actively explored opportunities for commercial agriculture. Letters to newspapers in the 1850s urged the construction of ship landings and roadways to transport produce, or described recommended crops for the region. In 1856, the Hāna Farmers Association (Ahahui Mahiai o Hana) was established and included members from Kaupō. The bylaws recommended crops such as taro, sweet potato, bananas, corn, beans, oranges and coffee. A few years later, in 1861, Kaupō settled on its first large-scale commercial crop. But it was not one of the recommended crops above. The plant was cotton.

its

Imported cotton had been grown in Hawaii for decades prior to the 1860s. A copper plate engraving from 1840 made at Lahainaluna school featured a cotton plant next to two banana trees.

But in 1861, the catalyst for cotton growing was a far-off event: the U.S. Civil War. By the summer of 1861, the North had effectively blockaded all Southern ports, severely restricting the South’s ability to export its high-quality “Sea Island” cotton. Prices soared.

Farmers throughout Hawai‘i took note of the economic potential, and on Sept. 13, 1861, the Cotton Farmers Association of Kaupō held its inaugural meeting, with 23 initial members. The minutes of that meeting were published later that month in Ka Hoku o ka Pakipika and included the following:

Hai mai o Manu i kona manao, pono i kela kanaka keia kanaka, e manao ana e hoao e mahi pulupulu, e hookupu mai i hapawalu kala pakahi, i mea e kuai ai i ka anoano a loaa mai ka anoano pulupulu alaila e mahele iwaena o kanaka.

Ku mai o H. Manase a hoike mai i kona manao, pono i keia komite ke hoike i ke kumukuai o ka paua pulupulu, a me ka lilo koke o ka pulupulu ke kanu ia, o poho auanei na kanaka.

Ku mai o T. C. Wilmington a wehewehe mai i ke ano o ke kanu ana ma Amerika, hai mai oia, he waiwai nui ka pulupulu i na manawa a pau. Aole manawa lilo ole o ka pulupulu ke mahiai maanei, no ka mea, aole like ka pulupulu me ke kalo, uala, a pela aku, ua lawe ia ka pulupulu i ka aina e, e like me ke ko, aole emi ke kumu kuai o ke ko, he waiwai nui ka pulupulu a me ke ko i na manawa a pau.

Manu spoke his opinion that everyone interested in trying cotton farming should each pay an eighth-dollar to purchase cotton seeds and, when they are acquired, to distribute them among the participants.

H. Manase stood and presented his opinion that this committee should report on the prices of cotton and the initial expenses of planting lest people be ruined.

T.C. Wilmington stood and explained the method of planting in America. He said that cotton is always valuable. It will never be unprofitable to cultivate here, because unlike taro, sweet potato, and so forth, cotton is exported to other lands. It is like sugar cane. The price of sugar cane never drops. Cotton and sugar cane are always highly valuable.

The members passed the resolution to each pay an eighth-dollar to purchase seeds, with the funds due by January 1862. By this time, a number of stores in Honolulu were offering seeds for sale.

A year later, in January 1863, there came an offer of a donation of seeds in Ka Nupepa Kuokoa:

Ua loaa mai ia’u ma ka la hope o Dekemaba iho nei, elua barela anoano pulupulu Aigupika, elua dala ke kuai pohoia mai no ka mea hookahi, a e hooili ana wau na ka ahahui mahi pulupulu ma Kaupo, ia Helekunihi, i ka Luna Hoomalu o ia ahahui i ka lua o ka barela, i mea haawi wale aku i ka poe hui kanu pulupulu. Aole no e haawi i ka mea i loaa ole ka eka, a mau eka paha. Aole no nae au e hooili wale ana ke loaa ole mai ka palapala a ka Luna Hoomalu, a me ke Kakauolelo oia aha paha.

On the last day of December, I bought two barrels of Egyptian cotton seeds for the dear price of $2 each. I will donate the second barrel to the cotton-farming association at Kaupo through Helekunihi, its chairman, to give to members. However, these seeds should not be given to those who do not have an acre or more. Moreover, the seeds will not be provided without a written request from the chairman or secretary.

The donor of these seeds was John Papa ʻĪʻī. Today he is best known for his government service and historical writings

“Farmers throughout Hawaii took note of the economic potential, and on Sept. 13, 1861, the Cotton Farmers Association of Kaupo held

inaugural meeting, with 23 initial members.”

“

published as the book Fragments of Hawaiian History. But in the 1860s, he also tried his hand at cotton farming. ʻĪʻī evidently was quite successful at growing cotton, at least according to a news brief in Ka Nupepa Kuokoa in August 1863:

Ua ike iho makou i ka mala pulupulu ma Mililani, a Ka Mea Hanohano Ioane Ii; a ua mahalo makou i ka maikai o ka ulu ana.

We have seen the Honorable John Ii’s cotton field at Mililani, and we are in admiration at how well it is growing.

This donation by ʻĪʻī was likely not purely altruistic and may have been connected to efforts by Henry Whitney, editor of Ka Nupepa Kuokoa, to distribute cotton seeds throughout Hawaii under a contractual arrangement. Whitney provided the following description of his arrangement:

1840 Lahainaluna engraving of a cotton plant & banana trees.

On the last day of December, I bought two barrels of Egyptian cotton seeds for the dear price of $2 each. I will donate the second barrel to the cotton-farming association at Kaupo through Helekunihi, its chairman, to give to members.”

John Papa ‘Ī’īNo ka halawai Ahahui mahini Pulupulu ma Kumunui Kaupo.

Sepatemaba 12, M. H. 1861

Halawai i ka hora 12 o ke awakea. Pule a pau; hookohoia o E. Helekunihi ma ka noho hoomalu. Ma ke oi o E. Helekunihi, ua kohoia o T. C. Wilmington i kakauolelo no keia Aha.

Ku mai o E. Helekunihi a wehewehe mai i ke ano o ke kanu ana o ka pulupulu, a me ka waiwai nui o keia hana.

Ku mai o H. Manase a noi mai i ka Aha e aeia kela mea keia mea e ku mai a e hoopuka i kona manao imua o keia Aha, no ka pono a me ka pono ole o keia hana, o ka mahiai pulupulu.

An article published in Ka Hoku o Ka Pakipika about the inaugural meeting of the Cotton Farmers Association of Kaupō, Sept. 13, 1861.

as reported in the Pacific Commercial Advertiser:

“The quality of the Hawaiian cotton was judged by experts to be superior to any in the Southern States, in fineness, length and strength. That shipped by Mr. Whitney was consumed chiefly by the manufacturers of sewing thread in Massachusetts and Connecticut, as it made the finest and strongest spool thread in the market. In length the staple of our best sea island cotton, grown from a plant less than a year old, measured from two to three inches.”

But Kaupō easily bested even this high bar set by Hawai‘i cotton in general. Another article in the Pacific Commercial Advertiser reported staple lengths for Kaupō cotton being double the already impressive Hawai‘i average:

“Seeing an opportunity for engaging in what promised to become a profitable business, I sent to Washington and also to New York, and procured at considerable expense several bags of genuine long-staple cotton seed, guaranteed to be from the best Georgia and South Carolina Sea islands. This seed was distributed without charge as called for by natives and foreigners living throughout the group, under a written contract with me to purchase at four cents per pound all the pure cotton in the seed that they would deliver in good condition in Honolulu.”

These terms were lucrative for Whitney. At the peak of Hawai‘i’s cotton period in the mid-1860s, Whitney earned $2.25 per pound for cotton shipped to New York. This was quite a premium over the $0.04 per pound paid to farmers for the raw cotton, though there were also costs to process the cotton before shipment.

For farmers who were willing to take payment in the form of issues of Ka Nupepa Kuokoa, Whitney offered a more generous $0.20 per pound, or a year’s subscription (a $2 value) for 10 pounds of cotton. As far as quality, the cotton grown in Hawaii was exceptional. A common measure of cotton quality is based on the length of the fiber (called the staple). A staple length of about 1.5 inches would fall into the highest ranking of extralong staple. Hawaii’s cotton easily passed this quality benchmark,

“[Whitney] had twelve or fifteen Sea-Island cotton gins at work preparing cotton grown on the four principal islands. … The best of this cotton, having a staple five inches long, and being wonderfully silky and fine, was grown in Kaupo, Maui, and Kona, Hawaii.”

While Kaupō’s cotton farmers were reaping the rewards of the Civil War blockade, they were also aware of those who were hurt by the effects. In April of 1863, H. Manase, pastor of Huialoha Church and a member of the Cotton Farmers Association of Kaupō, organized a church donation of $3.75 (about $90 in today’s money) to assist workers in England affected by the Lancashire Cotton Famine. This crisis involved a collapse in England’s fabric industry as a result of the blockade in the southern United States limiting cotton shipments to England.

“The quality of the Hawaiian cotton was judged by experts to be superior to any in the Southern States, in fineness, length and strength.”

The end of the U. S. Civil War marked the decline in Hawai‘i’s cotton industry. The global price of cotton plummeted, to $0.15 per pound from the high of over $2 per pound just a few years earlier. With the higher transportation costs of shipping cotton from Hawai‘i to the East Coast, it simply became unprofitable.

But Whitney also attributed the downfall of Hawaiian cotton to

a rattoon crop by cutting off the old trees and allowing the new growth to spring up from the roots, and starting new plants where the old were dead, that many of them resorted to this trick, which ultimately destroyed the cotton business, as it became extremely difficult to keep the good from the poor.... It was this deterioration in the quality, that led to the abandonment of the business, as it entailed a heavy loss on the

“[Whitney] had twelve or fifteen Sea-Island cotton gins at work preparing cotton grown on the four principal islands. … The best of this cotton, having a staple five inches long, and being wonderfully silky and fine, was grown in Kaupo, Maui, and Kona, Hawaii.”

poor crop management. Instead of continuously planting new cotton plants, farmers cut back and regrew the existing plants (called a “rattoon crop”), which reduced fiber quality.

“When the plants are cut down and a rattoon crop produced, the staple becomes weaker each crop, till finally it is worthless. The cotton growers found it so easy to raise

last few shipments. Had it not been for this deterioration in the quality of our long-staple cotton, the production of it might have continued to this day. A cotton plantation conducted by a skillful grower, and renewed every two or three years, by fresh planting and from the best imported seed, will probably pay, and we should like to see such an enterprise started.”

Throughout his childhood he spent weekends in Kaupō developing a deep connection to place. He has combined his passion for Kaupō’s physical landscape and its associated stories with his interest in photojournalism.

His website—www.kaupomaui. com—showcases an invaluable collection of Kaupō’s stories, photographs, place names, culture, and history. Please note that diacritical markings (‘okina and kahakō) have been omitted in certain places to remain consistent with original sources.

Aldei Kawika Gregoire is the grandson of Sam and Pauline Gregoire of Kaupō, Maui.

Aldei Kawika Gregoire is the grandson of Sam and Pauline Gregoire of Kaupō, Maui.

By Rachel Kingsley

By Rachel Kingsley

Standing under the canopy of a large hāpuʻu tree fern I pause, I am on the slopes of Mauna Loa on Hawaiʻi Island. I hear the distant wailing cry of the bird I am searching for, an ʻalalā. He is off in the distance and it is unlikely I will see him today. I have been told to hear the cry of an ʻalalā in a forest space means you should leave. That voice is providing a warning that something isnʻt pono or now is not a good time.

These birds, the ʻalalā, are often likened to forest guardians protecting their spaces and those that reside in them. Their voice, silenced in our native forests for many years, holds meaning. To hear it again in this space is a privilege afforded by a reintroduction project for which I am employed.

As the mist rolls in it brings in a cool breeze. I put on my rain gear and dial in the code for another bird on the radio receiver I hold in my hand. I wait to hear the familiar beeps getting stronger as I turn the antennae pointing me in the next

direction I need to hike. Setting off, I pick my way through the thick understory of native ferns and trees, smiling at the native berries I see along the way, food sources for the birds I am searching for.

These are images of special days I spent monitoring released ʻalalā in Puʻu Makaʻala Natural Area Reserve. We hope the people of East Maui will also have the privilege of hearing their voice in our forests someday soon, and this is the reason we reach out to the Kaupō ʻohana through Pōʻai Pili now as we consider where to next release ʻalalā.

ʻAlalā are a member of the Corvidae family of birds related to the American crow and common raven. Fossil remains indicate there were once five species of Corvids found across the Hawaiian islands, of which ʻalalā are unfortunately the last surviving members. ʻAlalā is historically known from Hawaiʻi Island, but it or a closely related Corvid was also present on Maui, indicated by remains found in a lava

tube on leeward Haleakalā. ʻAlalā eat a varied diet of fruit, insects, and other protein and in doing so provide a critical role of seed dispersal for many of our native plants. These birds, once abundant are now critically endangered and extinct in the wild due to a combination of threats including habitat loss, introduced predators, and introduced diseases.

birds, the ‘alalā, are often likened to forest guardians protecting their spaces and those that reside in them. Their voice, silenced in our native forests for many years, holds meaning.”

The last pair of ʻalalā were seen in the wild in 2002. Thanks to a conservation breeding program we still have ʻalalā today.

The story of ʻalalā has many twists and turns. In the 1990ʻs birds were released into habitat where the remaining wild population existed

“These

but were ultimately unsuccessful. After the captive population surpassed 100, The ʻAlalā Project, a partnership of the State of Hawaiʻi DLNR Division of Forestry and Wildlife, US Fish and Wildlife Service, San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, and others formed a new release strategy.

Starting in 2016, reintroductions of ʻalalā occurred in Puʻu Makaʻala Natural Area Reserve on Hawaiʻi Island. Each released bird was monitored via a radio transmitter in the wild. Survival was initially high and attempts at breeding were observed, but after three years an increase in mortalities of the released birds led to the return of the remaining five individuals to captivity. There were a variety of reasons for the increased mortality but one was the depredation of ʻalalā by their natural predator the ʻio, Hawaiian hawk. Before future releases on Hawaiʻi Island, more must be known about ʻio and ʻalalā’s complicated relationship.

As the remaining birds were brought back into the conservation breeding facilities, The ʻAlalā Project partners started to plan the next steps for this species. The overall goal of this program is to create a self-sustaining wild population of ʻalalā. In order to accomplish this goal it is necessary to understand how and what ʻalalā need in the Hawaiian forests of today.

The ʻAlalā Project is proposing to release ʻalalā on East Maui where there are no breeding populations of ʻio. A decision about whether or not to release on Maui is anticipated to be made in spring 2023 after a thorough analysis on potential impacts to the natural and cultural environment. Wild ʻalalā are likely to interact with the natural environment in a multitude

of ways, and we seek community guidance as to your concerns in this process. Overall, we are excited to see the health of mauka forests and watersheds benefit through their unique ability to disperse native seeds.

Guided by a structured decisionmaking process, community outreach, and field visits to six of the highest quality remaining habitat in Maui Nui, partners of the ʻAlalā Project have identified two potential release sites, Kīpahulu Forest Reserve and Koʻolau Forest Reserve, to analyze in an Environmental Assessment and Cultural Impact Assessment. The results of these assessments will frame the final decision.

The ʻAlalā Project wants to hear from the Kaupō community regarding their thoughts and concerns about the possibility for ʻalalā here. More information is available on The ʻAlalā Project website (www.alalaproject.org) and we encourage questions and comments to our email (info@ alalaproject.org) or by phone at 808-348-7898.

in an interview to be included in the Cultural Impact Assessment.

Community involvement and support are crucial for this species’ success and help determine whether East Maui is a suitable release site.

The story of ʻalalā has been complicated but is not over. We know the recovery of ʻalalā will take many years but will benefit other species and the overall health of the forest ecosystem by restoring the ecological services these birds can provide. We not only hope to one day hear the voice of ʻalalā protecting their forests again but provide the same opportunity for the next generation.

E hoʻolāʻau hou ka ʻalalā! May the ‘alala thrive in their forest home.

We expect completion of a draft Environmental Assessment this spring, and encourage comments to be submitted at that time as well. A great way to stay informed on the process is through our email list (ask us to add you). We are also seeking individuals who wish to share their ʻike and manaʻo with us

Rachel graduated from the University of Wisconsin Stevens Point with a B.S. in Wildlife Ecology: conservation and research. She went on to earn a Master’s degree in Zoology from Miami University through their Global Field Program. Rachel began working her professional career working with Hawaiian birds in 2006 as an intern at the Keauhou Bird Conservation Center on Hawai‘i Island. For nearly 10 years Rachel worked as a Research Associate as part of the conservation breeding program staff before becoming the Outreach and Education Associate for The ‘Alalā Project in 2017. Rachel continues to work with The ‘Alalā Project and in 2020 joined the team at The Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project. Rachel enjoys connecting audiences to the native forest and manu friends that make Hawai‘i so unique and special.

“The ‘Alalā Project wants to hear from the Kaupō community regarding their thoughts and concerns about the possibility for ‘alalā here.”

The Noenoe Ua Kea is a light misty rain that comes in on the Mālualua breeze and frequents Hāna, particularly the area in and around Ka’uiki. And it was said by L.K.N. Paahao of Mokaenui, Hāna, who wrote in Ka Lahui Hawaii Nupepa in January 1877, that “Ka Uakea” was the most famous rain of Hāna. This rain would arrive at around 9am or 10am, right after the dew from the night had all but dried up, and begin to saturate everything all over again. But Hāna people werenʻt ‘ōpili (cold, wet, numbed) by it, rather it gave the children a lovely appearance like no other“nohenohea lua.”

Because of Paahaoʻs detailed description of Ka Uakea in 1877 and our present-day continued pilina with Noenoe Ua Kea, we named our evening-time women gatherings Noenoe Nights. We gather in the evening time, after work is done, keiki are fed and we are able to fully receive, recharge and rejuvenate with our fellow titas, mamas, and hoa. The evening is from 5pm-9pm and we always learn something new, eat something delicious, and sip on some lively libations—but mostly we just spend time on ourselves and each other.

We have four Noenoe Nights planned for 2023 - February, May, September, and December. The cost is $50 per person and is allinclusive of the night’s activities, pupu and beverage. Spots are limited so to get on our Noenoe email list, contact us at (808)2487841, email us at contact@ alakukui.org or DM us on IG/ Facebook @alakukuihana

Ala Kukui’s Executive Director Kau‘i Kanaka‘ole is a kumu hula trained in the renowned Hālau o Kekuhi with more than 20 years of experience in cultural advocacy. She holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Education and has 14 years of teaching experience, including 11 years at Hāna School. She was born in Hilo, raised in Hāna and maintains extensive ties to the community. She is married to Fabian Ioane Park and is the mom of Nakaulakuhikuhi and Ho‘ola‘ika‘iwaalaimaka.

“Noenoe Ua Kea is a light misty rain that comes in on the Mālualua breeze and frequents Hāna, particularly the area in and around Ka‘uiki.”

Growing up in Hāna, I am surrounded by the incredible beauty that is my home. From beneath the shade and protection of the rising Ka‘uiki hill, in the warm healing salty waters of Kapueokahi and the caressing cool misty rain… Noenoeuakea. A sense of place; knowing where you come from, is buried deep in the sands of my birth…Kauakealaniha‘aha‘aohāna.

I’ve often pondered on what makes Hāna so rare and unique. The answer is on the winds that sweep across the land, sea, and sky bearing the stories of our ancestors. It is in the families who have lived here for generations; their connection to the ‘āina, each other and Akua. A sense of purpose; knowing who you are comes from the families who continue to grow where they are planted and bloom where they grow.

Families, who continue to work, play, pray, live and die on their ancestral lands…Families who hold fast to the traditions, values and skills which have been passed down from generation to generation…Families who continue to struggle and rise above the tides of change…Families who kept the essence and fullness of life claiming each day a blessing and making a difference in the lives of others.

E holomua kākou…Let us continue the journey…The knowledge and example that has been imparted to us is now our duty to share. The path has been laid down by those who walked before us, the trail has been cleared for us to follow. We must carry on the traditions and values for the next generation. It is now our turn to take the lead.

Sadly for the next generation, the path for them is filled with many

holes and part of the trail is being covered. Like us, some will fall in the holes and some will provide the means by which to fill them. Like us some will use tools to cut through the trail and open the way. Hope for the Hāna that was, and is, and will endure.

It is our kuleana… responsibility… to pass on to the next generation what we have learned from the generation before us. The course has been set by our Kūpuna before us; we must continue in their legacy of love for the next generation.

Will we be able to walk in their footsteps? Will we pass on what we have learned or what we did not try to learn? We are so blessed to know where we come from and who we are. We are the shade, protection, healing and caressing life force of the past, the present, and the future of Hāna.

To the families who were pillars in our life who left a legacy of love, touched the deepest part of our spirit, whose stories live on in the pages of our thoughts; words from their lips to our ears are engraved on our heart. They are families of faith, warriors with a passion to preserve the traditions, values and stories instilled in them from birth.

Mahalo ke Akua for blessing us with them in our life. They have stirred a fire burning in the core of our being to holomua! So here I write, with a kuleana to ‘My Legacy’ of Kānaka Maoli who have walked before me.

River water

darkening my paper beauty and smoothness

bringing out texture

yellowing my writing

blurring the letters a poem about the very thing that it is soaked in mixed with salt a memory of a day that will never come again

& Poems by Kamalama Mick Photos by Kamalama Mick & ‘OhanaLike glass you flow out to the sea

Meeting the ocean, together free Bending across the rain-spattered sand

Transposed against the rocky land

With my eyes upon you I can just be

Tendrils of water around the rocks

Secrets of nature again unlocked Tear the grass out from the mud

Undercut the cliffs with your mighty flood— Moving forever without thought

Lost in the place where you are found Sacred waters across the ground

You follow yourself, the only one Transformed to glass beneath the sun I am filled with peace from your gentle sound

Flowing down from many miles River, you make my heart smile

You don’t try—you simply do Oh, if we all could be like you In your waters I learn how to be a child

As Autumn begins to fade and winter bears nearer, signs of the aging year appear throughout the shoreline. Winter in Hawai‘i, and especially in Kaupō, is marked by the angle of the sun, the greening of foliage, the reappearance of seasonal insects and birds, the frequent presence of rainfall, and the consistent and soothing sound of the river—sometimes a bubble, sometimes a roar.

There is rarely a time in winter when the river is dry for a long period, except in the occasional drought. The heavy rainfall sends pools overflowing, waterfalls gushing, and rivers spilling out into the sea, where their clear, cold waters mix with the churning white and blue of the waves.

Just yesterday the river was swollen and muddy, scoring deep grooves along its banks and sending one of the many bank-side Christmasberry trees into the riverbed, roots dug from the soil. Despite being completely sideways, it still grows lush and green. The river eddies past it, over the stones and out to sea, to where it has carved a deep gully through the berm.

When the river is flowing, there is seldom a day where we do not manage to visit it at least for a little while, and sometimes for much longer than we ought to. Which is why this morning found my father and me surveying the receded waters beneath a gray-painted sky. Ripples crisscrossed the calm surface of the pool, the light foot

of the winds rushing it into chaotic disturbance. The banks were wrapped in a blanket of grainy mud and coated leaves, with the occasional liliko‘i nestled in the silty debris. I picked my way across scattered driftwood and over halfburied rocks towards where the river flowed out into the ocean.

As we stood on top of a high-cut bank, gazing down at the water that rushed past, the sun emerged from one of the thick horizon squalls and turned the water to a thousand twinkling diamonds of light. Transformed to moving glass, the river bubbled on, its voice making a wordless song through the crystallized sunshine.

Despite the mud in the river, the water itself was surprisingly clear, and the gray-hued river stones beneath the surface looked somehow close yet far away at the same moment. The strengthening wind caught a burst of spray and flung it upwards. On the mountain, the sun brushed the hills, turning them golden with its footprint.

As cloud shadows made fascinating patterns on the hills, a squall marched past on the distant horizon. Columns of rain in a dozen shades of gray poured from the heavy base of its cloud, their dark silhouettes against the light forming a brilliant picture of beauty. A ray of sun passed through the cloud, brightening a single rain column.

Another squall was passing mauka, and the sun painted a rainbow with millions of droplets. One rainbow, and then the double—a darker echo upon the rain.

A gentle wave rushed up the shore. Hints of blue sky appeared in the south. Scattered raindrops, the edge of the squall, darkened the stones and left tiny pieces of sunlight in my hair. I could taste salt on my lips, from the spray which forever comes from the sea.

Continued on page 24

“The heavy rainfall sends pools overflowing, waterfalls gushing, and rivers spilling out into the sea, where their clear, cold waters mix with the churning white and blue of the waves.”

“As we stood on top of a high-cut bank, gazing down at the water that rushed past, the sun emerged from one of the thick horizon squalls and turned the water to a thousand twinkling diamonds of light. ”

Tonight it is very still, the day’s wind having dropped to not even a whisper. All is silent but for the consistent chorus of crickets in the grass and the hollow clap of waves on the shoreline. The grass glitters as you walk, tiny gleams of dew appearing unexpectedly like little fallen stars.

Clouds temper the tapestry of the sky, hanging still in the momentary absence of wind. But the visible stars twinkle with bits of silver,

flickering like colorful candles and revealing the high winds above the clouds.

Orion rises above the tips of the hau, where bare twigs from summer still rise above the lush leaves, stark against the sky. Somewhere, an owl screeches.

And slowly but surely, step by step, winter creeps nearer through the unfolding of the seasons.

Golden in winter’s cold

Pale cream in spring and bold

In summer bright with flaring pink

Through the clouds the sunlight sinks

And orange, colors reaching higher

In autumn it sets the sky on fire

Like colors tuned to soft refrains

Of music: silent, joyous strains

Open your mind and heart and soul

To sunset colors, and be peaceful

Photos and Story by Jethro Canela

Photos and Story by Jethro Canela

The Kahakapao loop trail in the Makawao forest reserve is home to many native and nonnative plants and animals. The trail starts in a nonnative forest of eucalyptus and tropical ash. Both appear to be invasive. A few natives include Halapepe, ‘Ie ‘Ie, and Koa trees. What brought me here is the search for native snails and spiders.

Amakihi are heard all over the trail along with the Maui Endemic Alauahio and the Common Apapane, as well as nonnative leothrixes and white eyes.

Invasive Kahili gingers from the Himalayas are scattered in this nonnative forest. On my walk I saw a ravine filled with them. This ginger is affecting the fresh drinking water and soaking up the streams. Removal is a must!

I turned over a few gingers and found Nananana Makaki’i (happy-face spiders) and Kahuli (Hawai’i micro-snail). It was a great experience!

Seeing native snails and spiders is very interesting! Be sure to visit Kahakapao loop trail.

My name is Jethro and I live in Kīhei. I am a native bird enthusiast and care for Hawai’i’s fragile ecosystems. I am 12 years old as of January 2023 and I want people to understand that these islands have species of special concern. I am happy to share with people about the wonders of Haleakalā and how much it has to offer. Unfortunately these incredible habitats are being destroyed by deforestation and feral pigs. The birds are disappearing because of avian malaria spread by mosquitoes. I am trying to raise awareness about stopping these threats and saving our native ecosystems. With Pō’ai Pili I will start with a short article but will later write longer ones. It is truly a blessing that my close friend Kamalama Mick has started this great newspaper. I hope you enjoy my articles.

“The Kahakapao Loop Trail in Makawao is home to many native and nonnative species...What brought me here is the search for Native Snails and Spiders.”Left: A rare glimpse of the Hawaiian HappyFaced Spider, Nananana Makaki‘i. Endemic to the Hawaiian Archipelago. Below: Native ‘Ie ‘Ie continue to thrive amidst a non-native forest. Left: Native Kahuli on the underside of a leaf.

She was married in the 11th grade to Jerome Brewster, of Hāna—whose father was Reverend Brewster of Wananalua Church—and she graduated from Wai‘anae High School. From there she went to college with the intention to study law and follow in the footsteps of her grand uncle, Samuel “Webster” William Kaai who was a judge in Hāna in the early 1900s. Aunty Kaui left college after two years with a sense that she had a different calling on her life, or as she says, “I had something spiritual to do.”

When reflecting on her younger years, Aunty says, “I was bad, I would always fight; eh you start ‘um, I end ‘um, that is our style in Wai‘anae.” She recalls with gratitude the clean slate she received when her boss at Wailea petitioned to have her record expunged and admonished her to “behave!” Aunty shares with a laugh that, “ever since then I have behaved.”

Dorothy Kauionamauna Keliikoa Brewster resides in Kaupō with her daughter and son-in-law, Alohalani and Alika Smith. She was born in Honolulu and raised in the communities of Kaka‘ako, Wai‘anae, and Moloka‘i. Her dad, George Keliikoa, was a steel guitar musician and worked at Honolulu Ironworks, and her mom, Dorothy Koleka Kauilani Naoo, was very active with their church, Ka Makua Mau Loa.

When Aunty Kaui was young, she moved to Wai‘anae and lived near Pōka‘i Bay. Her childhood home was often filled with music, and she quickly learned to play the ukulele and sing by ear. Her parents were pure Hawaiian and her mother spoke fluent ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i. Her life was not always easy, and she shares that, “where I came from, we had to fight.”

During her childhood years, she spent time on Moloka‘i with her grandparents, Sarah Wahinekaapuni Kaai and David Kauilani Naoo, at their family home in Honouliwai. They lived on the beach and Aunty Kaui fondly recalls how they would “go right out the kitchen and dive into the ocean.”

She found her spiritual purpose and was ordained a deacon with her church where she dedicates her time in service to others. Now she is retired, after nearly 30 years of working in Wailea, and enjoys a peaceful life in Kaupō helping with the animals and spending time with her ‘ohana of 4 living children (she lost two sons), 21 grandchildren, and 17 great-grandchildren.

Aunty Kaui’s life reflects the deeper values and themes of forgiveness, resiliency, change, finding one’s true purpose, and aloha. She shares, “in my younger days, I put off certain things for my ‘old days.’ Now my old days are here and there is so much I want to do. I praise the Lord. He took me away from the things I am not supposed to do and helped me to grow. I want to do what I can while I am still here to do it. I am almost 80 and I just want to help others.”

CONTACT INFORMATION FOR THIS PUBLICATION

Makalapua Kanuha mekananiaokaupo61@gmail.com

Kauwila Hanchett kauwila3@gmail.com

Kamalama Mick poaipili@gmail.com