When We All

© 2023 Hofstra University Museum of Art

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the Hofstra University Museum of Art.

Cover image: Michele Pred (Swedish-American, born 1966), Love as Activism, 2021, neon on plexi, Edition 2 of 3, 26 x 26 x 5 inches, courtesy of Nancy Hoffman GalleryJanuary 31-July 28, 2023

Emily Lowe Gallery

The Hofstra University Museum of Art’s programs are made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of the Office of the Governor and the New York State Legislature.

Long before Hofstra was founded, indeed before there was “Long Island,” the Indigenous peoples called this region Sewanhacky, Wamponomon, and Paumanake – sacred territory inhabited by the Carnarsie, Rockaway, Matinecock, Merricks, Massapequa, Nissequoge, Secatoag, Seatauket, Patchoag, Corchaug, Shinnecock, Manhasset, and Montauk. Each tribe had its own territory, whose boundaries were respected by the others, and all inhabitants were united in their shared desire for peace. The land that surrounds Hofstra University is part of that history. We want to protect its legacy and honor the Indigenous peoples who have made untold contributions to our region.

The mission of the Hofstra University Museum of Art is to “advance knowledge and understanding through experiences with authentic works of art from the world’s diverse cultures.” One way the Museum accomplishes this mission is by presenting exhibitions and programs that encourage dialogue and inquiry and prompt visitors to consider an alternate point of view or see an issue from another perspective.

The exhibition When We All Stand was inspired by a White House briefing that took place on May 12, 2009, where over 60 artists and creative organizers met with Obama administration officials to discuss the collective power of the arts to build community, create change, and chart a pathway for national recovery in the areas of social justice, civic participation, and activism.

Based on the idea that artists have a civic responsibility, Alexandra Giordano, assistant director of exhibition and collection, has curated an insightful and thoughtful exhibition. She spent time researching artists and reaching out to organizations to select the works of art on view. We all benefit from her careful and considered curation, where each work of art adds to the story. I am confident that When We All Stand will provide inspiration for thought, conversation, and an open exchange of ideas.

We extend our thanks to the lenders to the exhibition. Their generosity and enthusiasm for this exhibition has made this project possible.

The Bishop Gallery, Brooklyn, NY

Molly Crabapple

Equal Justice Initiative

The Estate of Emma Amos For Freedoms

Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, NY

Miguel Luciano

Nancy Hoffman Gallery, New York, NY

Michele Pred

RYAN LEE Gallery, New York, NY

Hank Willis Thomas Sophia Victor

Museum exhibitions are a collaborative process, from the initial idea to the opening reception. I am extremely grateful for the continuing support, assistance, and contributions of the Museum staff.

Karen T. Albert Director, Hofstra University Museum of ArtArt reveals the details of humanity. It illustrates the desires, needs, and challenges of society. It can be a powerful ally in the fight for social justice by giving a voice to the unheard and visibility to those unseen and can offer solutions by making connections. Artists as activists create work that helps us better see each other. Theirs is a unique responsibility that presents a clear way to understand our diverse world and history. In 1962, civil rights activist James Baldwin penned the essay The Creative Process, where he explained artists’ civic participation and influence. He wrote, “The precise role of the artist, then, is to illuminate darkness, blaze roads through that vast forest, so that we will not, in all our doing, lose sight of its purpose, which is, after all, to make the world a more human dwelling place.” Baldwin passed the torch to artists of the 21st century, who continue to work with this effort in mind.

The exhibition When We All Stand focuses on the collective power of the arts to address complex issues in society and demonstrates the ability of art and artists to chart a path for social change. Artists often lead the charge and expose truths that may otherwise be ignored. The artists in this exhibition take a stand and call out injustices through their art and activism on issues such as immigration, gender, reproductive rights, mass incarceration, voting rights, racial bias, gun violence, and promises unfulfilled. They act by creating national campaigns for justice, organizing public art protests, connecting with their local community, or joining forces with national organizations. Some make demands on government, politicians, policies, or institutions, while others make demands on society and individuals to join them in the fight for justice; still others focus on cultural development as a process that cultivates democracy and unity. All combine the making of art with public service that has a grassroots approach, with the hope of mobilizing their communities and the nation to ignite movement, create awareness, and inspire others to stand with them. Artists included in the exhibition are Emma Amos, Molly Crabapple and the Equal Justice Initiative, For Freedoms, Miguel Luciano, Michele Pred, Hank Willis Thomas, and Sophia Victor.

The artists, artwork, and methodologies in the exhibition explore how art can tackle important social issues for a country in crisis. This exhibition does not attempt to address every issue but instead lays the foundation for what can follow by demonstrating how artists encourage citizens to get involved, offer alternative ways to combat social injustices, and activate democratic values that promise equality and freedom.

Art and artists have long been in the business of making inequities visible. For example, realism, the European art movement of the 19th century, took the viewer to rural and urban settings that showed the brutal realities of the working class as opposed to the lavish lifestyles lived by some. Artists such as Gustave Courbet, Jean-François Millet, and Honoré-Victorin Daumier rejected the sugary sweet scenes presented previously. Instead, they used a neutral palette with direct images that tore the viewer away from whitewashed, pastoral landscapes and replaced them with labor and living conditions that were harsh and uncomfortable. Twentieth-century American artists such as Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine used photography and social realism to challenge the romanticized American dream for immigrants, women, and children. Hine’s photographs awakened Americans’ consciousness and proved that the camera and art can promote social change. His searing images influenced policy reforms in the workplace and the nation’s labor laws. Other movements such as ashcan art, informally led by Robert Henri, “wanted art to be akin to journalism ... he wanted paint to be as real as mud, as the clods of horse-shit and snow, that froze on Broadway in the winter.”1 Their art was anti-elite and committed to showing the worthiness of the immigrant and working class. Artists such as Jacob Lawrence and Aaron Douglas explored themes of mass migration, race, segregation, and institutional persecution. Lawrence’s art was a direct protest to the unjust Jim Crow laws of the South that codified racial inequality. Later in the 20th century, artists continued to respond to marginalized groups and supported the civil rights movement and the women’s rights movement. Benny Andrews, Romare Bearden, Elizabeth Catlett, and Danny Lyon used their art to fight for individual freedoms, often becoming a voice that spoke against oppression. This short list makes no attempt to cover the pantheon of artists who have, throughout history, made art in the service of social justice and communicated truths that benefit greater humanity. It provides a jumping-off point for artists of the 21st century who continue to fuse social issues, creative problem solving, and activism with their art.

1 Hughes, Robert. American Visions: The Epic History of Art in America. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2014, p. 325. Hughes, Robert. The Wave from the Atlantic, American Visions. BBC, February 5, 2002, Episode 5 of 8.

It is fitting to begin the exhibition with Emma Amos. She was, at once, a passionate, political humanitarian and an artist, who used her methods and materials to illuminate challenges for Black Americans and women. For over six decades, she dedicated her work and life to addressing obstacles faced by those disregarded by society, and she created art that clearly depicted those obstructions. Through her use of color and materials, not only did she challenge white masculinity, but she also addressed her personal and political experience as a Black woman. In an interview conducted by critic and curator Lucy Lippard in 1991, Amos explained, “Every time I think about color it’s a political statement. It would be a luxury to be white and never have to think about it.”

Early in her career, Amos sought opportunities that were socially charged. She became the only woman and youngest person invited to join Spiral, a New York City-based collective of Black artists active in the 1960s and 1970s. Here, she and her counterparts discussed their role in the country’s rapidly changing political and cultural landscape. Among her peers were the co-founder of the group, Romare Bearden, as well as members Hale Woodruff, Norman Lewis, and Charles Alston. The formation of the group in 1963 was inspired by the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedoms. Amos also contributed to the feminist-political art journal Heresies in the 1970s and participated in the Guerrilla Girls, anonymous artist activists who protested injustices through the 1980s and remain active today. Other contributions for the betterment of society can be seen in her illustrations done for the children’s PBS program Sesame Street. She gained attention in recent years, appearing in the major touring exhibitions Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power (Tate Modern, London) and We Want a Revolution: Black Radical Woman (Brooklyn Museum). Both exhibitions opened in 2017. A major retrospective, Emma Amos: Color Odyssey, was presented at the Georgia Museum of Art in 2021. Emma Amos passed away in 2020 after a long battle with Alzheimer’s disease. Beyond her activism, she leaves behind a body of work that is meant to inform, dislodge, question, and tweak prejudice, as well as challenge rules and display her distaste for the notion that there is “art” and “Black art.”

The painting on fabric of the hunter Orion included in this exhibition is a culmination of her intentions. Amos’ Orion (2012) stands as a proud Black man who looks boldly at the viewer, clothed in modern-day athletic gear and not the traditional garb of the giant huntsman and demigod son of Poseidon. He is the embodiment of strength, reimagined in darker skin, and breaks the paradigm of Western white power. In addition to his warrior attributes, Orion’s mythology explains that he was placed in the sky by Zeus as the most recognizable constellation and that his name means “rising in the sky.” Amos was very interested in Greek mythology and often incorporated references in her work to comment on and interfere with the history of art that has been dominated by European men. Other examples of Amos’ exploration of Greek mythology can be seen in the prints Billie Holiday as Leda and Zeus as Football Player (both 1984). Paintings such as Models (1995) and Bell Jar (1996) depict her use of Greek iconography. The former includes the Greek sculpture Kritios Boy, and the latter shows bell hooks juxtaposed with an iconic Greco-Roman jar. Like Orion (2012), they are both painted on fabric and demonstrate how Amos disrupts Western imagery to address issues of gender and race.

Her use of colors, cloth, and imagery also connects with her identity as a woman and her African American heritage. She deliberately used bold colors and often commented that these colors were attributed to “male work.” This use of color contrasted with her choice of material – textiles – which is quintessentially considered within the realm of “women’s work.” Early in her career, she trained with textile designer Dorothy Liebes as a weaver and designer. This experience had a profound influence on her and sparked her love for fabric and African textiles. The border on Orion (2012) is a combination of African kente and kanga cloth, fabrics she collected during her travels. Integrating these materials is a tribute to both women and the African continent. In addition to the use of fabric for its ancestral connotations, Amos paints hands on the surrounding border of Orion (2012), imagery she has used repeatedly in previous artwork. Both serve as cultural threads within the painting. The multicolored hands holding coins or seeds is a popular motif found on African fabrics sold in the West and may harken back to prehistoric cave paintings that were reexamined by modern artists, who, like Amos, looked for inspiration beyond the European art historical canon.

Emma Amos (American, 1937-2020)

Orion, 2012

Acrylic on canvas with collaged African fabric borders 77.25 x 62 inches

© Emma Amos

Courtesy of the Estate of the Artist and RYAN LEE Gallery, New York

Where Emma Amos’ art and activism addressed sweeping issues facing Black Americans and women, the artist Michele Pred focuses on matters that are more specific to women, such as equal rights, equal pay, access to birth control, bodily autonomy, abortion, and reproductive rights. Amos and Pred, however, share a connection to the 1960s, 1970s, and the women’s rights movement that is a sisterhood of sorts. While Amos was active during this period, Pred uses a variety of materials as a time machine to transport the viewer to an era in American history when women were still very much under the control of men and to confront the current oppressive threats to women’s reproductive freedom.

Michele Pred

(Swedish-American, born 1966)

Freedom is for Everybody, 2022 Vintage purse with electroluminescent wire 13.5 x 14 x 3 inches

Courtesy of Nancy Hoffman Gallery

Michele Pred is a Swedish-American conceptual artist whose sense of justice is deeply influenced by her father, Allan Pred, an internationally recognized professor at the University of California, Berkeley. He wrote extensively about race, capitalism, and social justice. Her mother’s Swedish heritage inspired her desire to see greater support for mothers and better child care and public education. Growing up in the tumultuous 1970s in Berkeley, California, Pred was exposed to the nation’s growing struggle for equal rights. From an early age, she participated in family conversations about the emerging women’s movement during the ’70s and the importance of taking action and being politically invested. Most importantly, she learned the value of examining and discussing political events and understanding different perspectives; she realized that conversations start locally, in homes, in neighborhoods, and in communities. These small, civil discussions about change can grow into movements that can take on a national or global scale. She saw that art could be the impetus for this dialogue.

Michele Pred

(Swedish-American, born 1966)

Pro Choice, 2022 Vintage purse with electroluminescent wire

11 x 13 x 5 inches

Courtesy of Nancy Hoffman Gallery

Pred’s practice includes sculpture, assemblage, and performance. Much of her art combines everyday found objects to address gender and racial equity issues. By using shoes, hats, T-shirts, vintage purses, and other discarded objects (e.g., birth control pills), she uncovers the cultural and political meaning behind these items. Unlike other politically active artists, her work is not confined to a gallery; instead, it is portable or wearable and acts as a minibillboard that promotes her messaging in public spaces. As an original member of the artist-led civic organization For Freedoms, her work has been featured in large-scale, country-wide billboard campaigns such as For Freedoms’ 50 State Initiative (2018). In the fall of 2022, she launched her own national Vote for Abortion Rights billboard exhibition with Save Art Space and Kickstarter in conjunction with a solo exhibition titled Equality of Rights at Nancy Hoffman Gallery in New York City. Pred’s contribution to the public art project was on view in New York City at West 46th Street and 12th Avenue. The billboard featured a black, vintage purse with the gleaming numbers 1973 across the side of the bag, the year the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in the case of Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113, ruled that the Constitution of the United States protected the right to have an abortion and personal privacy. Her recent work stresses that abortion is health care, and the need for action is critical. Billboards from various artists will be hung in 14 cities across 12 states where abortion rights and women’s health are under siege. The 1973 purse displayed on Pred’s billboard is included in this exhibition.

Another important aspect of Pred’s work is her ability to motivate people to march. On October 8, 2022, she sounded the alarm and invited all to join in her Vote for Abortion Rights parade in New York City. People rallied at Washington Square Park with wearable art that addressed the many issues under attack and served as a reminder of the power of voting. Both the parade and billboard campaign demonstrate Pred’s swift response to the Supreme Court’s conservative majority’s 6-3 vote in the case Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, No. 19-1392, 597 U.S._(2022), which overturned Roe v. Wade and paved the way for states to immediately ban abortions. Her previous Kickstarter campaign, We Vote parade in 2018, is another example of her overtly political art actions. For this parade, she collaborated with social justice organizations such as the Center for Reproductive Rights, Gun X Gun, and Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition. Pred and the (Re)Sistxrs collective, a group of artists who began organizing in 2016, have staged 10 feminist parades in New York, Miami, San Francisco, Oakland, and Stockholm. She continues to support Planned Parenthood, NARAL Pro-Choice America, and other organizations that advocate for reproductive freedom by donating proceeds from the sales of her electroluminescent-wire purses. In 2019, she participated in the 100 Years/100 Women initiative that celebrated the centennial of the 19th Amendment, which granted women the right to vote. She continues to actively participate with For Freedoms’ civic art projects such as Wide Awakes (2020) and For Freedoms’ news channel, which was launched at the Brooklyn Museum in 2022.

The artwork on view, Freedom of Choice #2 (from the 2015 exhibition titled Choice at Nancy Hoffman Gallery in New York City), a collection of vintage handbags from the 1950s and 1960s, and a neon sculpture, Love as Activism, are all representative of the work Pred creates. Her art and activism are a counter-offensive to the mounting legislation and decisions made by the Supreme Court that have severely impinged upon the rights of women in the United States. Some purses included in the exhibition are from an earlier body of work titled Power of the Purse (2017), which was created in response to a 2017 Republican tax reform. Others are inspired by the Pred-à-Porter (2015) series, which is now part of the permanent collection at the Berkeley Art Museum. Pred-à-Porter is a play on words. Instead of Prêt-à-Porter, she inserted her last name, which modernized the reference to the 1959 readyto-wear movement that transitioned from high-end, exclusive haute couture fashion to clothing that was more accessible, affordable, and liberating for women. In addition to addressing gender, health, and financial concerns, the group of purses in the exhibition creates a road map for the future of women’s rights and offers suggestions on how to activate change. It is the artist’s intention for the beaming letters to light a path for women, who in her opinion should be moving forward, but instead tread dangerously backward toward darker times, like the era that created the bags she uses. Her use of modified vintage handbags is particularly wise. It calls to mind the female body, asks what is carried inside, and says something about wealth, status, and personal power.

I Am a Voter, 2022

Vintage purse with electroluminescent wire 11 x 14 x 3 inches

Courtesy of Nancy Hoffman Gallery

Love as Activism (2022) is Michele Pred’s call to arms and is a synthesis of her early upbringing, where she was exposed to civil protest and discourse, with a reminder of how modern-day dilemmas can be confronted. The combination of a raised fist and a neon, glowing heart illuminates a more peaceful and humane approach. Pred’s work avoids name calling, derogatory terms, or references to back-alley abortions. Amid the violent and angry rhetoric, the sculpture stands as a beacon of hope that references a time when nonviolent protest was the action of choice. Love as Activism shines brightly and forges a path less traveled in recent years, one that emphasizes dialogue, especially with those of opposing views, with the goal of finding a middle ground, commonality, and perhaps even love.

Michele Pred (Swedish-American, born 1966) Freedom of Choice #2, 2015 American flags on wood 12 x 62 x 1.5 inches

Courtesy of Nancy Hoffman Gallery

Michele Pred (Swedish-American, born 1966)

Equality, 2019

Vintage purse with electroluminescent wire 11.25 x 4 x 12 inches

Courtesy of Nancy Hoffman Gallery

Michele Pred (Swedish-American, born 1966)

Me Too, 2022

Vintage purse with electroluminescent wire 15 x 11 x 3 inches

Courtesy of Nancy Hoffman Gallery

Michele Pred

(Swedish-American, born 1966)

Vote for Change, 2022

Vintage purse with electroluminescent wire 14 x 11 x 4 inches

Courtesy of Nancy Hoffman Gallery

Michele Pred (Swedish-American, born 1966)

Vote Feminist, 2022

Vintage purse with electroluminescent wire 12 x 7 x 1 inches

Courtesy of Nancy Hoffman Gallery

Miguel Luciano is a Brooklyn-based artist who was born in Puerto Rico and grew up in a family that was politically and social engaged. His art directly interacts with community members in thoughtful, meaningful ways as he aims to create universal experiences that underscore humanity’s desire for freedom and the pressing need for change. Luciano’s work combines the artist’s commitment to themes of history, popular culture, social justice, civic engagement, and migration with public art projects, paintings, and sculpture that activate youth groups and communities. Both the DREAMer Kites (2012) and Health, Food, Housing, Education (after the Young Lords) (2015) allow the viewer to envision an America where young people, undocumented immigrants, immigrants, and people of color can soar to the potential promised by the American dream, a dream that has yet to be delivered to all.

Like Emma Amos’ fabric painting of Orion (2012), Luciano’s public art project DREAMer Kites (2012) asks viewers to lift their eyes once again to the sky for inspiration and possibilities. The DREAMer Kites (2012) were part of The Ripple Effect: Currents of Socially Engaged Art, curated by Raquel de Anda. The exhibition was on view at the Art Museum of the Americas of the Organization of American States in Washington, D.C., and was co-sponsored by the Washington Project for the Arts. Additional support came from CultureStrike and United We Dream. Undocumented youth activists and allies were invited from New York and Washington, D.C., to create a handmade kite with a life-size self-portrait. After participating in a workshop with the artist, the participants flew their kites on the National Mall to raise awareness and support for the DREAM Act (Development Relief and Education for Alien Minors), which seeks not only to end the deportation of students who desire a college education but also to enact comprehensive immigration reform. Like primary source documents, the humble, paper kites record their highest aspirations: to stay in the country they love, to continue their education, and to address immigration issues that deeply affect them and their families. They capture a historic moment of protest by young people at the nation’s capital and give flight to their dreams of a better life. Juxtaposed with the timeless monuments, the kites are ephemeral – easily swept away like the people themselves. But unlike the temporary nature of undocumented immigrants and the materials used, the kites will be preserved in the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C., where they will serve as a reminder of the protest and of promises unfulfilled.

The DREAMer Kite included in the exhibition, Francisco (2012), displays the portrait of Francisco Gutierrez, who was a student at Georgetown University at the time. In this photo, Gutierrez’s hands are raised to his mouth, emphasizing the message “Listen to me!” and his floral shirt was worn as a personal LGBTQ+ statement. He flew his kite on November 4, 2012, two days before the presidential election, as part of the larger protest. Gutierrez and his peers were joined by additional groups of undocumented youths as they rallied on the National Mall. Luciano’s project created a forum to address the inadequate provisions made by the government’s immigration policies and the students’ right to be free. The enormous self-portraits that flew above the city made a powerful statement: that legislation affects real people who have hopes and dreams and who make meaningful contributions to their communities.

Inspiration for the DREAMer Kites (2012) public art project came from Luciano’s art protest Chiringas de Paz para Vieques (“Vieques Peace Kites”) (2002), which supported the civil disobedience movement in Vieques, Puerto Rico, that protested the U.S. military’s use of the island as a weapons testing ground. Luciano revisited the kite format again in 2012 for a public art project titled Amani Kites (Peace Kites) in Nairobi, Kenya, created through the smARTpower program – an initiative of the Bronx Museum of the Arts and the Bureau of Education and Cultural Affairs of the U.S. Department of State. Continuing through 2014 with support from Art Matters and the Lambent Foundation, the Amani Kites (Peace Kites) public art project expanded the conversations about flying and freedom.

Luciano’s dedication to community organizing and his use of art as a vehicle for change are evident in the sculpture Health, Food, Housing, Education (after the Young Lords). This piece was commissioned for the exhibition ¡Presente! The Young Lords in New York, at the Bronx Museum of the Arts, El Museo del Barrio, and Loisaida Inc. in 2015. The Young Lords were a socially motivated, revolutionary group of Puerto Rican youth activists.

(American, born in San Juan, 1972)

Health, Food, Housing, Education (after the Young Lords), 2015 Wood, urethane, enamel, vinyl 72 x 34 x 3 inches

Commissioned for the exhibition ¡Presente! The Young Lords in New York, El Museo del Barrio Courtesy of Miguel Luciano

They promoted the liberation of all oppressed peoples and fought racism and injustices with an emphasis on health, food, housing, and education. Inspired by the Black Panthers, the Young Lords were active during the late 1960s and 1970s in East Harlem and throughout New York City neighborhoods, demanding civil rights and reform. Luciano’s work is a sculptural interpretation of the iconic poster used by the Young Lords to promote their political platform and mission. The large, wood cutouts are painted with glossy, purple car paint that plays to the Young Lords’ savvy design sensibilities and understanding of consumerism in the mid-20th century. Each AK-47 features a word that symbolizes an aspect of their activism and is emphasized with the word “struggle.” Luciano’s three-dimensional version gives the message new life. By re-creating the poster, Luciano extends the narrative of the Young Lords and brings their radical activism to the current generation of young people with the hope of awakening their political consciousness.

His recent public art project, Mapping Resistance: The Young Lords in El Barrio (2019), commemorated the activist history of the Young Lords in East Harlem. It featured the photography of Hiram Maristany, who was the official photographer of the Young Lords and a founding member of the New York City chapter. Large photographs of the Young Lords were installed throughout East Harlem, at the same locations where protest events had taken place over 50 years earlier. This project was featured in MetFridays at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through their Civic Practice Partnership (CPP). Miguel Luciano was one of two inaugural artists invited to the CPP artist-in-residence program from 2017 to 2021.

Who wants to walk when they can fly? In 2012, I felt like I was on top of the world. I was a few months away from graduating from Georgetown University, my biggest accomplishment to date, at least on paper. That same year, I participated in Miguel Luciano’s DREAMer Kites project to break my silence. I wanted to be seen and heard hundreds of feet above ground, despite my parents’ advice to shrivel.

For years, I was outspoken and I leaned into my identity as a “Dreamer,” a derivative term from the highly politicized proposal, Development Relief and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Act. Had the DREAM Act passed through legislation more than 20 years ago (2001), it would have granted other undocumented people (“Dreamers”) and me a pathway to citizenship.

“Dreamer” was an identity that I owned, to my detriment, and one that politicians and the media exploited to segment the deserving immigrant population from the undeserving one: my parents, my community, and many others I could not name, but who, like me, were stuck in limbo. It took years of unlearning to understand that I was more than a political pawn or token character, and that my narrative could be about more than just survival and hardship. The freedom I so desperately sought was right in front of me. More than 10 years after this kite project, with a still unresolved legal status, I continue to be resourceful and innovative in order to lead a deserving life.

While President Obama’s prosecutorial discretion program, DACA or Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (2012), provides some of us with a form of protection, it also remains fickle and does not help us establish residency in the United States. Worse, it doesn’t address the other 11.4 million undocumented people living here.

Miguel Luciano

(American, born in San Juan, 1972) Francisco, DREAMer Kites, 2012 Paper, wood, string, photo vinyl 48 x 48 x 3 inches

Courtesy of Miguel Luciano

With a fury to report, Molly Crabapple’s art fights for the highest ideals of humankind. She is devoted to representing those struggling and underrepresented in society. The primal desire to communicate and record is seen in her drawings. Her use of line and language intertwines to create images that are a commentary on current events, often making connections to historical or past events that set social and political precedent. Crabapple is a New York-based artist and writer of Puerto Rican and Jewish descent whose writing includes Brothers of the Gun, an illustrated collaboration with Syrian war journalist Marwan Hisham, and her memoir, Drawing Blood. Her reportage has been published in The New York Times, Review of Books, The Paris Review, Vanity Fair, The Guardian, VICE, The New Yorker, and Rolling Stone, and her artwork is in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art, the Library of Congress, and the New-York Historical Society. She received a Yale Poynter Fellowship, a Front Page Award, and a Gold Rush Award, and was shortlisted for a Frontline Print Journalism Award. In 2011, she began to modify her drawing with journalistic sketching during the Occupy Wall Street protest, a movement that, among other things, addressed class conflict. With intensity and truth, her drawings continued to depict scenes of Lebanese snipers, labor struggles in Abu Dhabi, Guantanamo Bay, the U.S. border, American prisoners, Greek refugee camps, the ravages of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico, the 2016 U.S. presidential election, and issues of race. Her coverage of these topics and events solidified her journalistic approach and illustrative drawing.

As an award-winning animator, Crabapple combined these techniques and pioneered a new genre of live-illustrated explainer journalism that is seen in the video Slavery to Mass Incarceration (2015). She collaborated with the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) for this project. EJI was founded in 1989 by Bryan Stevenson, an acclaimed public interest lawyer and bestselling author of Just Mercy. As a private, nonprofit organization, EJI provides legal representation to people who have been illegally convicted, unfairly sentenced, or abused in state jails and prisons. The organization works with communities that are marginalized by poverty and treated unfairly, and it is determined to change the narrative about race in America. In 2018, the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration opened in Montgomery, Alabama. Crabapple’s animations, including the one seen here, are on permanent display at the museum.

The short film, animated by Crabapple and narrated by Bryan Stevenson, explores the premise that “Slavery did not end in America. It evolved.” In image after image, the viewer is confronted with drawings that unpack the elaborate mythology of racial difference that was created to justify and sustain enslavement – which continues today, particularly in the criminal justice system and in the South. An alternate narrative has emerged in many Southern communities where the era of slavery is still celebrated. In rapid succession, the video details the horror of the domestic slave trade to the longstanding efforts that support racial hierarchy. The video culminates with Stevenson plainly stating that a solution to racial bias and discrimination is possible through understanding its role in history and ultimately working together to end the cycle that started in 1619. Crabapple’s drawings included in the exhibition are from the video Slavery to Mass Incarceration (2015) and a video produced with EJI, Reconstruction in America 1865-1876 (2015). This short film shows how the promises of the Emancipation Proclamation and the Reconstruction Act failed to deliver racial equality to former slaves. Instead, racial violence prevailed: Black political participation was blocked, Black voting was nullified, and Jim Crow laws created a future of white supremacy and inequality. The drawings included from Reconstruction in America 1865-1876 (2015) illustrate the systemic hate that manifests itself, for example, at the ballot box where citizens are denied their most important and basic right: the right to vote. Her videos can be viewed on social media, which increases accessibility, and her animations have been nominated for three Emmys and won an Edward R. Murrow Award.

Crabapple’s black lines weave together stories of people who are brave and fearless. Her work confronts deep societal and political issues that question how justice and liberty are valued and exposes the most egregious abuses against humanity. Her limited color palette conjures the black of newsprint – she is reporting the past and present in her artwork. Through her activism and art, she attempts to enlist those who are strong of heart, willing to roll up their sleeves and push against the forces that repress and suppress the people illustrated in her work. The artist continues to use her medium to report. She recently returned from Ukraine, where she used her sketchbook to document “daily existence in the shadow of the Russian invasion.”

Molly Crabapple (American, born 1983)

Six drawings from Slavery to Mass Incarceration, 2015 Ink and gouache on Arches paper 12.25 x 16 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Brooklyn-born artist Sophia Victor aims to dismantle inequality and oppression by humanizing social justice issues. In contrast to Molly Crabapple’s drawings from the video Slavery to Mass Incarceration (2015), which expose history’s established relationship to racial hierarchy and its lasting effects, Sophia Victor makes it personal by creating artwork that focuses on individual biographies. The figures that appear in her paintings are real people whose stories have either never been told or have had brief media attention only to be overshadowed by the next big news event.

In the mural and series titled Every Mother’s Son (2014), portraits of mothers from both the past and present are painted to remind the viewer that these young men and their families are not just tragic symbols of American racism, but are human beings. Their struggles are real and the pain of losing a loved one remains for the families left behind. She poetically attacks the devastating consequences of police brutality through portraits of mothers who have lost their sons to gun violence. Instead of confronting violence with anger, Victor uses the universal language of maternal love to tackle overwhelming feelings of loss. The mural painted outside the art collective venue Ideal Glass in the East Village of New York City and the paintings in the series are a tribute to Black and Latino mothers who have endured the loss of a child through a violent act. Inspired by a documentary of the same title by Tami Gold, Victor includes in the mural the faces of Kadiatou Diallo, Mamie Till, Constance Malcolm, Margarita Rosario, Gwen Carr, Lesley McSpadden, and Iris Baez.

Two paintings from the series are in the exhibition. Both are intimate portraits that capture the pain and anguish of family members in grayscale. Gwen Carr and Lisha Garner (mother and sister, respectively, of Eric Garner) are painted in Every Mother’s Son #4 (2014), and Emmett Till’s mother and uncle (top) and Ramarley Graham’s parents, Frank Graham and Constance Malcolm (bottom), are seen in Every Mother’s Son #2 (2013). Black and white imagery, truncated views of the figures, and intense body language amplify their sorrow. In the painting Every Mother’s Son #4 (2014), the SMPTE (Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers) color bars pressing down on Eric Garner’s mother and sister have a specific meaning for the artist. It is her way of communicating to the viewer that the conversation about police brutality and gun violence cannot stop. It cannot be fleeting. There was a time in television history (circa 1970) when programming would end and the color bar test strip would appear on the TV screen. For Victor, the use of these bars is a symbol of how the discussion about gun violence ceases; the media’s attention is diverted until the next unnecessary death occurs.

Another powerful connection to the repetitive nature of violence and police brutality against young men of color can be seen in the painting Every Mother’s Son #2 (2013). Here, Victor stacks a double portrait of Emmett Till’s mother and uncle above Ramarley Graham’s parents. All are dressed in formal clothing and their bodies are compressed in the space. The cropped boxes give the illusion of a photograph or Polaroid, but Victor’s brushwork and texture contrast that of a printed image. Color is used sparingly. Their pain is palpable – and it is timeless. Therein lies Victor’s challenge: How many portraits will follow this sequence? How many mothers will continue to seek justice for their sons long after they have been lost, criminalized, and forgotten by mainstream society? Her artwork stands as a testament to end this vicious cycle.

Earlier in her career, Victor discovered the power of art as advocacy and initiated her To Be Free project in 2010. Through her activism, she championed political prisoners of the 1960s and 1970s. Many are still incarcerated, and some are largely unknown. Unlike other artists who choose to spotlight the Black liberation movement, Victor doesn’t show the history but instead focuses on a generation of activists, primarily from the Black Panther movement. The painting Brother Mondo II (2015) is representative of the activist Mondo we Langa, who was charged and convicted of the murder of an Omaha police officer in 1970. [Much controversy surrounded the case; Amnesty International recommended a retrial, and the Nebraska state parole board recommended his release. Mondo we Langa died in prison in 2016.] While the painting is not a traditional portrait, it captures the essence of the movement. The upturned, open hand is painted on a backdrop of printed pages from The Black Panther newspaper, which

strove to enlighten and inform. In addition to making portraits, Victor also created a book of her correspondence with many still serving time. Letters to and from members of the Black liberation movement were included, and proceeds from sales have gone to help those returning to society. Since the beginning of the series To Be Free (2010), some activists have been released.

Victor’s art and activism include her work with organizations such as Amnesty International to create murals that focused on political prisoners in conjunction with the Write for Rights event, which encourages members to write letters in support of those imprisoned. As a part of the Artistic Noise team, she worked with teens who were transitioning out of the juvenile justice system and used collaborative art projects to develop personal growth and build community. Her paintings were included in ¡Presente! The Young Lords in New York at the Bronx Museum of the Arts, El Museo del Barrio, and Loisaida Inc. in 2015, where she highlighted the presence of women in the movement. In 2019, she was commissioned to make a sculpture of poets, writers, and activists for the Vera Institute for Justice in New York. Victor was a PAIR Fellow (Public Artists in Residence) working with the NYC Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice in 2020. Currently, she facilities art workshops at Rikers Island through her company, I Am Wet Paint. Sophia Victor is represented by The Bishop Gallery in Bedford Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, where gallery owners Stevenson Dunn and Erwin John’s business ethos is one of inclusivity, as they challenge and disrupt the norms presented by the status quo and the often-intimidating art industry.

Sophia Victor (American, born 1988) Brother Mondo II, 2015 From the series To Be Free Oil and collage on canvas 48 x 48 inches

Courtesy of The Bishop Gallery

Sophia Victor (American, born 1988)

Every Mother’s Son #2, 2013 From the series Every Mother’s Son Acrylic and Ankara cloth on canvas 48 x 72 inches

Courtesy of The Bishop Gallery

Sophia Victor (American, born 1988)

Every Mother’s Son #4, 2014

From the series Every Mother’s Son Acrylic on wood 36 x 48 inches

Courtesy of The Bishop Gallery

Leading up to the 2016 U.S. presidential election, artists Hank Willis Thomas, Eric Gottesman, Michelle Woo, and Wyatt Gallery founded the artist-led organization For Freedoms. Motivated by some of the most urgent social issues of the time, the group produces public art projects, exhibitions, public programming, and nationwide campaigns that spark conversation and promote engagement. Committed to the belief that art engages citizens, elevates thinking, creates connections, promotes discourse, and can reimagine problems into solutions, the group continues to grow. It is now the largest artist-led community for creative civic engagement in the United States that is dedicated to bringing people together, where multiple perspectives are present. For Freedoms expands ideas about democracy, freedom, and civic purpose and presents a platform for the future. The artist organization was inspired by the Four Freedoms speech given by Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

In January 1941, then president of the United States Franklin Delano Roosevelt in his Annual Message to Congress (State of the Union Address) presented his reasons for American involvement in aiding Britain during World War II – a time when fascist, totalitarian regimes were violently toppling democratic governments. It was not until the fourth draft that FDR had an idea for a peroration (the closing of a speech). To emphasize the critical nature of what was being threatened and the direness of the moment, FDR amended the speech to clearly include the universal freedoms that all people possess: freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear. The powerful ideas articulated at the end of the address became the foundational principles for the Atlantic Charter declared by Winston Churchill and FDR in 1941, the United Nations Declaration of January 1, 1942, and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted by the United Nations in 1948 through the work of Eleanor Roosevelt. When FDR recited these newly added “four freedoms” slowly and with purpose to his advisors, Samuel I. Rosenman, one his speechwriters, recorded the dictated words on his yellow notepad. A facsimile of his handwritten note is included in the exhibition.

After hearing FDR’s speech, Norman Rockwell, an American illustrator, immortalized the words into paintings, which were then printed in The Saturday Evening Post in 1943. Soon after, representatives from the Post and the U.S. Department of the Treasury announced a joint campaign to sell war bonds and stamps to support the war effort. Each person who purchased a war bond received a set of prints of the four paintings. The mass distribution helped make the Rockwell images iconic and tethered them to the hopeful nature of FDR’s vision.

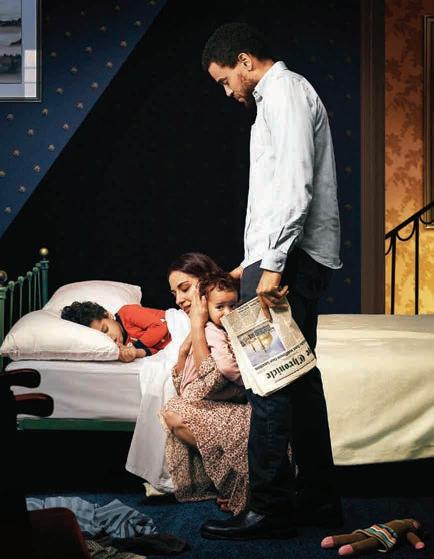

The four photographs included in the exhibition titled Four Freedoms: Freedom of Speech, Freedom from Want, Freedom from Fear, and Freedom of Worship (2018) are almost exact replicas of Rockwell’s 1943 originals, except for an important and distinct update. These new images are populated with figures of varying races, religions, cultures, and sexualities and present an accurate representation of diversity in the nation. Over 100 different models and 80-plus reproductions of Rockwell’s works were made for political advocates across the country. They were created to motivate voters in anticipation of the 2018 U.S. midterm elections. With a similar aim as the originals, these images are a call to action by the artists to maximize democratic participation by inviting all voters to defend these essential human rights 75 years later. The images spread across social media, prompting Americans to consider the value of their vote. Some of the photographs were used in For Freedoms’ 50 State Initiative (2018), a national campaign that encouraged political discourse via artist-designed billboards, public art projects, and artist-led town hall events. The billboards were nonpartisan and did not support specific candidates, but instead used the power of art to communicate some of the most pressing social issues to voters with the intention to inform, encourage critical analysis, and stimulate conversation. It brought art and issues to viewers’ hometowns and local roads, literally to their own backyards.

For Freedoms continues to create new initiatives that are designed to empower everyday citizens and challenge the current state of affairs. In its firm belief that artists can unleash the potential of American democracy and return it to the people, the group launched Wide Awakes in 2020. Inspiration came from the Lincoln-era youth movement of 1860. As the country careened toward civil war, a group of young abolitionists, donned in capes, military caps, lanterns, and banners decorated with eyeballs, organized and rallied around the presidential hopeful from Illinois, Abraham Lincoln. They proclaimed themselves the newfound voice of younger voters who rallied against slavery and are credited with assisting in Lincoln’s campaign and success. For Freedoms’ modern-day Wide Awakes (2020) public art campaign infused civic participation with celebration and joy despite the COVID-19 pandemic, the oversaturation of disinformation, and political division. Building on their previous successes, they continue to develop novel ways to reignite democratic participation, and to maximize engagement and inclusion. Their current art campaigns are Another Justice: By Any Means Necessary, Hear Her Here, AAPI Solidarity, and Landback. In every venture, For Freedoms considers ways that art and artists can transform American culture to the full embodiment of a democratic society, where citizenship is seen as participation, not ideology, and the words “all are created equal” ring true.

For Freedoms

(established in the United States, 2016)

Freedom of Speech, 2018

Archival pigment print 44 x 55 inches

Courtesy of For Freedoms

For Freedoms

(established in the United States, 2016)

Freedom from Fea r, 2018

Archival pigment print 44 x 55 inches

Courtesy of For Freedoms

For Freedoms

(established in the United States, 2016) Freedom from Want, 2018

Archival pigment print 44 x 55 inches

Courtesy of For Freedoms

For Freedoms

(established in the United States, 2016) Freedom of Worship, 2018 Archival pigment print 44 x 55 inches

Courtesy of For Freedoms

In the Punctum series, Hank Willis Thomas, acclaimed photographer, conceptual artist, and co-founder of For Freedoms, questions the social function of archival images that depict past struggles from the Holocaust to the civil rights movement to apartheid and how they can be reexamined with a contemporary context. Using historical photographs surrounding race, gender, identity, and popular culture as the foundation of his work, Thomas transforms two-dimensional scenes of protest or persecution into compelling three-dimensional sculptures. Thomas isolates a portion of a photograph and presents a limb or limbs that extend beyond the planar frame and offers a hyper-focused, cropped view. The viewer is challenged to contemplate the framing and consider what isn’t being shown and to ask why. The Punctum series of sculptures highlights universally recognizable hand and body gestures to illuminate oppression, resistance, and resilience. The gesture-focused sculptures memorialize specific moments and communicate ideas about perseverance and collective identity. By making the past present, Thomas allows for a reinterpretation of previous social struggles to better understand current conflicts and explores history as a gateway to the future.

The sculpture Lives of Others (2014) is part of the Punctum series, which is derived from French philosopher Roland Barthe’s photographic theory of punctum. In Barthe’s book Camera Lucida, the author examines studium and punctum and the distinction between the two when viewing a photograph. Studium, as the initial intention of the photographer, is used to draw the viewer in, as opposed to punctum, which is the deeper element that punctuates or penetrates the viewer in an emotional way. Another way to understand punctum is the compelling detail that pierces the viewer emotionally, cannot be described easily with words, and lasts long after the visual experience has expired.

Lives of Others (2014) allows for physical interaction with the sculpture. The viewer circles the work, obtaining different vantage points, and can revisit an earlier angle after an alternate view has been observed. Thomas capitalizes on this type of experience and presents incomplete forms that require active participation by the viewer because the narrative is unfinished. Instead of being presented with something complete, Lives of Others (2014) is a scene interrupted, an instant frozen in time of two hands connecting in space. Who is holding the hand that comes from above? Where is the person situated whose hand rises upward? What is needed and what is given? Thomas captures the decisive moment when two humans decide to grasp for each other. It is in that visceral moment that the viewer is given a complete understanding of the power of their unity and its lasting effects. Lives of Others (2014) was inspired by a photograph that was taken on the day the Berlin Wall fell in 1989.

Other hand gestures used in the Punctumseries include the raised fist or open hands with arms reaching upward. The raised fist has been a symbol of oppression and protest connected to civil rights incidents in the 1960s and was used as an antiapartheid rally cry and recently by artist Michele Pred in her sculpture Love as Activism (2022) to address inequality of pay for women and reproductive rights. It signifies self-affirmation, subjecthood, defiance, and strength. Both of Thomas’ sculptures, Amandla (2013) and A Luta Continua (2013) (the title is a pan-African slogan, and refers to “ongoing struggle”), depict upward jutting fists that represent those captured from a demonstration in Johannesburg in 1992. In the sculpture Raise Up (2014), 10 sets of arms extend above heads viewed from the back from the mid-shoulders up. The sculpture was based on South African photographer Ernest Cole’s image During group medical examination, the nude men are herded through a string of doctor’s offices (1958-66). Thomas was moved to create a sculpture that returned dignity to the bodies that were humiliated and subjugated in the photograph. Raise Up (2014) was made a few months before Michael Brown, an unarmed Black teenager, was killed in Ferguson, Missouri. After his death, the words “hands up, don’t shoot” became a powerful chant for the Black Lives Matter movement and gave new meaning to Thomas’ sculpture and further demonstrated the power of gestures to communicate and connect. The piece is permanently installed on the grounds of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama.

Hank Willis Thomas’ tireless efforts to underscore democratic values, encourage civic duty, create unity, and reframe narratives around race, history, and popular culture in American society have been recognized nationally and internationally. Thomas’ work is in numerous museum collections. His many collaborations include Question Bridge: Black Males, In Search of the Truth (The Truth Booth), and For Freedoms, which invites members of the public who do not consider themselves artists to think creatively, so they too can act as civic leaders. For Freedoms has received multiple recognitions, including the 2017 ICP Infinity Award for Online Platform and New Media. In 2021, Question Bridge: Black Males debuted at the Sundance Film Festival and was selected for the New Media grant from the Tribeca Film Institute. Hank Willis Thomas has been awarded many prestigious fellowships and is represented by Jack Shainman Gallery in New York.

In 2022, Thomas was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, a learned society founded in 1780. Members include George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Martin Luther King Jr., Nelson Mandela, Albert Einstein, El Anatsui, and many other champions for change, whose creativity, courage, and insight have propelled humanity forward.

Alexandra Giordano Assistant Director of Exhibition and Collection, Hofstra University Museum of ArtHank Willis Thomas (American, born 1976) Lives of Others, 2014 Black urethane resin 57 x 5 inches © Hank Willis Thomas Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Throughout history, constellations have helped guide those looking for direction. Like Emma Amos’ Orion (2012), the art and artists in this exhibition chart a path that leads to greater equality. They are freedom’s north star. If justice were blind, it would know not the color, creed, or gender of the hand it holds as it embarks on the future. This destination can only be discovered when we all stand together.

The following list of organizations is a starting point to discover ways to take a stand, think creatively, and become a civic leader:

Big Brothers Big Sisters of Long Island https://bbbsli.org/ CARECEN (Central American Refugee Center) https://www.carecenny.org/ Immigrant Defense Project https://www.immigrantdefenseproject.org/

League of Women Voters of New York https://lwvny.org/ LGBT Network https://lgbtnetwork.org/

Long Island Alliance for Peaceful Alternatives https://www.longislandpeace.org/

Long Island Cares https://www.licares.org/

Long Island National Organization for Women (Nassau Chapter) https://now.org/chapter/ny0428-nassau-now/ Long Island Together https://www.longislandtogether.org/

Nassau NYCLU Regional Office https://www.nyclu.org/en/chapters/nassau-county Nassau County Board of Elections https://www.nassaucountyny.gov/566/Board-of-Elections S.T.R.O.N.G. Youth https://www.strongyouth.com/

Urban League of Long Island www.urbanleaguelongisland.org

National Resources

Advocates for Youth https://www.advocatesforyouth.org Alliance for Youth Action https://allianceforyouthaction.org/ American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) https://www.aclu.org/ Brennan Center for Justice https://www.brennancenter.org/ Center for Reproductive Rights https://reproductiverights.org/ Fair Fight (Voting Rights) https://fairfight.com/join-our-fight/ Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America https://momsdemandaction.org/ https://momsdemandaction.org/tag/new-york-chapter/ National Immigrant Justice Center (NIJC) https://immigrantjustice.org/ National Organization for Women (NOW) https://now.org/ Planned Parenthood https://www.plannedparenthood.org/ https://www.plannedparenthood.org/planned-parenthoodgreater-new-york Rise First https://risefirst.org/ Vera Institute for Justice www.vera.org

American University Museum. It Takes a Nation: Art for Social Justice with Emory Douglas and the Black Panther Party, Africobra, and Contemporary Washington Artists. Washington, D.C.: Alper Initiative for Washington Art, 2016. Bronx Museum of the Arts. ¡Presente! The Young Lords in New York. New York: The Bronx Museum of the Arts, 2015. David Winton Bell Gallery. Hank Willis Thomas, Primary Resources. Providence, RI: Brown University, 2015.

FDR Library and Museum, Hyde Park, New York, www.fdrlibrary.org/four-freedoms

Four Freedoms Park, Roosevelt Island, New York, www.fdrfourfreedomspark.org/learn/the-four-freedoms-speech/ Gonzales, Elena. Exhibitions for Social Justice. London and New York: Routledge, 2020. Harris, Shawnya L. Emma Amos: Color Odyssey. Georgia: Georgia University Museum of Art, University of Georgia, 2021. Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School, Ithaca, New York, www.Law.cornell.edu/wex/roe_v_wade_(1973) Supreme Court of the United States, www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/21pdf/19-1392_6j37.pdf

Emma Amos (American, 1937-2020)

Orion, 2012

Acrylic on canvas with collaged African fabric borders 77.25 x 62 inches

© Emma Amos

Courtesy of the Estate of the Artist and RYAN LEE Gallery, New York

Molly Crabapple (American, born 1983)

Equal Justice Initiative (established in the United States, 1989) Three drawings from Reconstruction in America 1865-1876, 2020 Ink and gouache on Arches paper 12.25 x 16 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Six drawings from Slavery to Mass Incarceration, 2015 Ink and gouache on Arches paper 12.25 x 16 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Equal Justice Initiative presents Slavery to Mass Incarceration, 2015

Narrated by Bryan Stevenson Illustrated by Molly Crabapple

Written by Bryan Stevenson and Kim Boekbinder

Directed by Jim Batt and Kim Boekbinder Video 5:51

Courtesy of the Equal Justice Initiative

For Freedoms (established in the United States, 2016) Hank Willis Thomas (American, born 1976) and Emily Shur (American, born 1976) in collaboration with Eric Gottesman (American, born 1976) and Wyatt Gallery (American, born 1976)

Freedom from Fea r, 2018 Archival pigment print 44 x 55 inches

Courtesy of For Freedoms

Freedom of Speech, 2018 Archival pigment print 44 x 55 inches

Courtesy of For Freedoms

Freedom from Want, 2018 Archival pigment print 44 x 55 inches

Courtesy of For Freedoms

Freedom of Worship, 2018 Archival pigment print 44 x 55 inches

Courtesy of For Freedoms

Miguel Luciano (American, born in San Juan, 1972) Francisco, DREAMer Kites, 2012 Paper, wood, string, photo vinyl 48 x 48 x 3 inches

Courtesy of Miguel Luciano

Health, Food, Housing, Education (after the Young Lords), 2015 Wood, urethane, enamel, vinyl 72 x 34 x 3 inches

Commissioned for the exhibition ¡Presente! The Young Lords in New York, El Museo del Barrio Courtesy of Miguel Luciano

Newspaper article from The Washington Post of DREAMer Kites event on the National Mall, 2012 16 x 20 inches

Courtesy of Miguel Luciano

Michele Pred (Swedish-American, born 1966) 1973, 2022 Vintage purse with electroluminescent wire, Edition 2 of 3 7.5 x 13.5 x 2 inches

Courtesy of Nancy Hoffman Gallery

Bans Off Our Bodies, 2022 Vintage purse with electroluminescent wire Edition 3 of 25 10.5 x 10.5 x 3.5 inches

Courtesy of Nancy Hoffman Gallery

Believe Women, 2018 Vintage purse with electroluminescent wire 11 x 9 x 3 inches

Courtesy of Nancy Hoffman Gallery

Equality, 2019 Vintage purse with electroluminescent wire 11.25 x 4 x 12 inches

Courtesy of Nancy Hoffman Gallery

Equal Rights, 2022 Vintage purse with electroluminescent wire 10 x 14 x 3 inches

Courtesy of Nancy Hoffman Gallery

Freedom is for Everybody, 2022 Vintage purse with electroluminescent wire 13.5 x 14 x 3 inches

Courtesy of Nancy Hoffman Gallery

Freedom of Choice #2, 2015 American flags on wood 12 x 62 x 1.5 inches

Courtesy of Nancy Hoffman Gallery

I Am a Voter, 2022 Vintage purse with electroluminescent wire 11 x 14 x 3 inches

Courtesy of Nancy Hoffman Gallery

Love as Activism, 2021 Neon on plexi, Edition 2 of 3 26 x 26 x 5 inches

Courtesy of Nancy Hoffman Gallery

Me Too, 2022 Vintage purse with electroluminescent wire 15 x 11 x 3 inches

Courtesy of Nancy Hoffman Gallery

Power of the Purse: Equal Pay, 2018 Vintage purse with electroluminescent wire, Edition 6 of 10 13.5 x 10.5 x 3 inches

Courtesy of Nancy Hoffman Gallery

Power of the Purse: Vote/Feminist, 2018 Vintage purse with electroluminescent wire, Edition 1 of 10 7 x 12 x 1 inches

Courtesy of Nancy Hoffman Gallery

Pro Choice, 2022 Vintage purse with electroluminescent wire 11 x 13 x 5 inches

Courtesy of Nancy Hoffman Gallery

Resist, 2018 Vintage purse with electroluminescent wire, Edition 2 of 10 12 x 15 x 4 inches

Courtesy of Nancy Hoffman Gallery

Sisterhood is Powerful, 2022 Vintage purse with electroluminescent wire 15 x 8 x 2 inches

Courtesy of Nancy Hoffman Gallery

VOTE, 2018 Vintage purse with electroluminescent wire, Edition 5 of 10 10 x 9 x 4 inches

Courtesy of Nancy Hoffman Gallery

Vote Feminist, 2022 Vintage purse with electroluminescent wire 12 x 7 x 1 inches

Courtesy of Nancy Hoffman Gallery

Vote for Change, 2022 Vintage purse with electroluminescent wire 14 x 11 x 4 inches

Courtesy of Nancy Hoffman Gallery

Hank Willis Thomas

(American, born 1976)

Lives of Others, 2014 Black urethane resin 57 x 5 inches

© Hank Willis Thomas Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Sophia Victor (American, born 1988)

Brother Mondo II, 2015

From the series To Be Free Oil and collage on canvas 48 x 48 inches

Courtesy of The Bishop Gallery

Every Mother’s Son #2, 2013

From the series Every Mother’s Son Acrylic and Ankara cloth on canvas 48 x 72 inches

Courtesy of The Bishop Gallery

Every Mother’s Son #4, 2014

From the series Every Mother’s Son Acrylic on wood 36 x 48 inches

Courtesy of The Bishop Gallery

SUSAN POSER President

CHARLES G. RIORDAN Provost and Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs

COMILA SHAHANI-DENNING Interim Senior Vice Provost

HOFSTRA UNIVERSITY MUSEUM OF ART

KAREN T. ALBERT Director

KRISTEN DORATA Collection Manager

JESSICA DISIBIO Museum Educator

JACKIE GEIS Senior Assistant to Director

ALEXANDRA GIORDANO Assistant Director of Exhibition and Collection

STEPHANIE MCGEE Museum Educator

EILEEN MCKENNA Museum Educator

SARA SCHAEFER Museum Educator

AMY G. SOLOMON Director of Education

GRADUATE ASSISTANTS

Samrath Kaur Batra, Margarita Lopez

GRADUATE ASSISTANTSHIP Mary Conroy

Christianne Binondo, Makayla Egolf, Corinne Hemmer, Angelina Olivo, Bella Palaia, Josie Racette, Paxton Splittorff, Caitlin Treacy