artifact & edifice

Hunter Courtney

recontextualizing the found

Thesis Documentation

Hunter Luke Courtney

To, Mom and Dad, thank you for driving me to pursue my passions above all else, and the assiduous and steadfast support you have given me for the last 5 years and my entire life. I love you!

To, KatieScarlett, This degree, and this thesis would not be possible without your inexhaustable love and support. Thank you, and I love you!

To, Gran Jan, thank you for introducing me to the world of design as a child, and nurturing that love for the past 23 years!

To, Hilary, your guidance and critique has been invaluable to my development as a designer. From learning to draw plans in 2nd year, to the conceptual underpinnings of my thesis, Your holistic and thoughful teachings are something I’ll take into every aspect of life. Thank you!

To, CJ, thank you for your mentorship and truly introducing me to the world of practice. I appreciate not only the educaiton and training, but the many conversations we shared and time I spent in the studio with you and Matias.

In partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Bachelor of Architecture

Undergraduate Thesis Fall 2021 - Spring 2022

Faculty Advisor: Hilary Bryon

Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University

College of Architecture and Urban Studies

School of Architecture + Design

“Whether Mr Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, and placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view – created a new thought for that object.”

- Marcel Duchamp“Objects are kind of imbued with a certain power in themselves, in their very actuality. When we surround ourselves with them there is a certain osmosis, it’s a complex and complicated relationship.”

- Mike NelsonArtifacts, within this thesis inquiry, are found manmade, industrial objects. These discarded objects are no longer used for their intended purpose, but exist in a limbo between decrepitness and usefulness. Marcel Duchamp coined the term readymade in the early twentieth century when referring to extant manufactured objects that he used in his work. Similar to Duchamp’s approach, each of the found artifacts studied in this thesis exists as a readymade yet formerly functioning object. Duchamp also frequently used ordinary and functional objects in his sculptural constructions. He argued that the ordinary is elevated when it is re-programmed, re-contextualized, or modified. Thus, artifacts in context can be vehicles for something greater than pure functionality or raw material value. The concept of juxtaposing extant specific artifacts into new contexts and functions than those for which they were designed is a powerful device for unveiling valuable latent qualities in items classified as waste. This concept can also serve as critique on our consumerist culture. The life of an object should not be considered as concluded when it can no longer perform its prescribed function.

Jean Tinguely, Santana, painted black iron, wood and electric motor, 1966

Marcel Duchamp, Bicycle Wheel New York, 1951

Jean Tinguely, Santana, painted black iron, wood and electric motor, 1966

Marcel Duchamp, Bicycle Wheel New York, 1951

Assemblage is the act of bringing disparate elements together to form a coherent, integrated whole. Assemblage artists often use found or readymade objects to construct their compositions. In these assemblages, the unique material, formal, and structural qualities of each element form a complex, layered organization or arrangement that is greater than the sum of its parts.

Kitbashing is a technique related to scale model making, in which one scavenges parts from existing commercial model kits to construct a novel model. Scavenged parts are also combined with scratch built parts to form new constructs.

Kitbashing and assemblage don’t need to be limited to models or sculptures. These forms of making are effective in the way that they draw interesting juxtapositions between objects, and in doing so subvert expectations. Disparate forms (of objects) joined in a new way create novel combinations that would not exist otherwise. These new compositions elevate objects, especially found ones, to a new plane of existence.

Assemblage and kitbashing reveal the multivalent nature of the adopted components. By placing specialized elements in a new context, or by modifying them in some way, different qualities are revealed. The quintessential example is Picasso’s Bull’s Head, where a conjoined bicycle saddle and handlebars simultaneously read as a bull’s head. Identifiable bike parts, and their original material qualities, are carefully juxtaposed and create another reading. Kitbashing takes this idea one step further by incorporating scratch built components to either further unify the whole or draw a larger juxtaposition.

Pablo Picasso, Bull’s Head, 1942

kitbashed model parts on orignal Millenium Falcon model: Star Wars, 1977

Pablo Picasso, Bull’s Head, 1942

kitbashed model parts on orignal Millenium Falcon model: Star Wars, 1977

Browsing government surplus and scrap auction websites, one can purchase highly specialized industrial artifacts. These objects range from mountains of scrap metal to vehicles, construction equipment to small goods, and even bomb disposal robots. Each listing effectively transitions an artifact into a new stage of life. I assert that these artifacts could exist in the plane of Duchamp’s readymade objects. Each artifact is rife with unexpected and subversive possibility relative to a novel context, form, and function. These aging industrial artifacts can find new futures outside their explicit functional utility within an assembled, kitbashed architecture.

Originally, these artifacts existed in a highly specialized and functional state. I aim to subvert expectations by juxtaposing an artifact’s forms within a new architecture, and elevate its function from pure utilitarianism to a new functionalism. My thesis substantiates that found, post-industrial artifacts have overlooked and latent tectonic, syntactic, structural, and spatial qualities. These discoverable qualities initiate new and complex part-to-whole relationships through their juxtaposition with new construction, program, site, and relation to natural systems. As well, juxtaposing extant artifacts with natural environments highlights the significant contrasting qualities of each. Thus, artifacts and nature can work together to elevate each other. Through these explorations, I seek a cohesive whole between artifact and architecture.

The nature of the objects is uncovered through an adulturative process of framing and incorporation into a new multivalent architecture. The objects are re-thought relative to functional and spatial characteristics. By removing the objects from their original context, and performing form-preserving modifications, each object is refocused in its negotiation between the manmade and nature using each artifact’s special characteristics. This thesis investigates a number of artifacts, their inherent qualities, and their adaptation. Thus, the thesis engages and questions the relationship between the architecture, industrial artifacts, and the natural environment.

The first study of kitbashed architecture looked toward found objects in a valley inhabited by the aqueducts that give Los Angeles life. The surrounding water management infrastructure includes nearby large industrial objects that could be repurposed – instead of bringing new materials into the remote area. The proposed kitbashed house sits above Rose Valley and the South

Haiwee Reservoir west of Death Valley. This first study uses found artifacts, specifically a culvert and water tower to jumpstart an assembled architecture of found artifacts and new building construction. The spatial potential of these extant artifacts is investigated as they are modified and placed into a new built context.

vast and remote

Rose Valley is a vast piece of land bordered by mountains that run north and south. The vistas are wide in every direction. The climate is dry and unforgiving. A house within the inhospitable climate is an unexpected

juxtaposition. Using locally found materials can help to justify construction in such a remote location.

California: site located between the Sierra Nevadas and Mojave Desert

California: site located between the Sierra Nevadas and Mojave Desert

Rose Valley: a meeting point for the two aqueducts that feed Los Angeles

kitbashd house perched above the desert floor

Rose Valley: a meeting point for the two aqueducts that feed Los Angeles

kitbashd house perched above the desert floor

The house is principally composed of a concrete culvert cut in half laterally and pulled apart to form the upper and lower boundaries of the house’s volume. A tubular structure, partially made of an abandoned water tower, hangs off the side. These industrial artifacts were chosen for their form, proximity to the local water management infrastructure, and a curiosity about the spatial characteristics of these large objects. When one enters the building, they must pass through the less conventional space, a tube made of the water tower. The floor inside is grated and lit to reveal that one is in an unconventional tubular space. A decommissioned convex optical lens taken from a nearby observatory distorts the desert landscape and focuses the sun for a concentrated solar-power

system, thus offering a new visual perspective of nature as mediated by found artifacts. Heading into the main living space, one passes outside through a trussed bridge into the living room, capped by onehalf of the found concrete culvert. Although culverts may look like nothing else in a normal home, bisecting the cylinder and positioning the halves at a distance defines a relatively normal living space. The small diameter of the culvert delineates the width of the building, so the building expands upward vertically. Each culvert is also a large source of thermal mass. The bottom culvert warms during the daytime and the warmth radiates upward during the cold desert night, while the roof culvert inverts this process during the night, cooling the building through the hot desert day.

abandonded water tower revealing the scale of massive aqueduct culverts

water tower and culvert: a kitbashed house

abandonded water tower revealing the scale of massive aqueduct culverts

water tower and culvert: a kitbashed house

panoramic desert view (above) juxtaposed with a focused, flipped, and distorted view (below)

panoramic desert view (above) juxtaposed with a focused, flipped, and distorted view (below)

focusing and distorting

The house seeks to subvert the typical visual experience of the desert. The desert is normally viewed in vast panoramas that extend to the horizontal edges of vision. The cylindrical forms of the local artifacts lend themselves to framing and focusing this panorama. When a cylinder is inhabited, the viewer’s sight is compressed.

Entering and leaving the home is punctuated by a semicircular room, partially made of the water tower that also compresses one’s view. The focused view into the desert is then distorted by the large optical lens, letting one examine an otherworldly perspective before carrying on with the conventional parts of their day.

north elevation: tectonic assembly of house

south elevation: observatory lens and trussed bridge structure

north elevation: tectonic assembly of house

south elevation: observatory lens and trussed bridge structure

The second study of kitbashed architecture looked to government surplus auction websites to source materials. Looking through the heavy machinery categories, one can find many large disused objects for sale. A mining load hauler bucket, essentially a huge steel scoop, was selected and studied in relation to meditation spaces. Questions arose including: what is the

nature of the space between the former earth mover and the earth, and how might artifacts of industry create spaces that reflect opposite values to the object’s original function?

This massive steel bucket was removed from a decommissioned mining vehicle, and my interest in the bucket was piqued specifically by the large cavity where rock normally sits. The nature of the cavity can be transformed by a simple spatial translation. Flipping the bucket and then suspending it from above creates sheltered space.

A meditation room for one sits between the bucket and a carved space within the earth. The bucket becomes the roof of the room, providing shelter, but also a space between the earth and itself. Thus, the space between the machine tool and the earth is recontextualized and now an occupant is held gently in this liminal space.

sketch illustrating the relationship between earth, bucket, and room loader bucket cavity

between the earth and the machine

sketch illustrating the relationship between earth, bucket, and room loader bucket cavity

between the earth and the machine

load haul dumper for sale on govplanet.com, used to move mining rubble and ore to the surface

load haul dumper for sale on govplanet.com, used to move mining rubble and ore to the surface

axonometric drawing: descent into the earth before entering the space of the load hauler bucket

axonometric drawing: descent into the earth before entering the space of the load hauler bucket

Merriam-Webster defines meditation as “to engage in mental exercise (such as concentration on one’s breathing or repetition of a mantra) for the purpose of reaching a heightened level of spiritual awareness.” Thus, meditation is a tool to navigate the interstitial space in the mind between a normal state of awareness and a heightened one. In this room for one, a glass

volume is held within earthen retaining walls, while the suspended loader bucket provides shelter and shade. The glass allows the occupant to feel cocooned within nature while also being protected from above by the manmade shield. The room occupies the interstitial space of the earth, while the occupant accesses the interstitial space of their mind.

a room, defined by the shelter of the bucket, sits inside carved earth protected from above, steel and glass allow one connection to the outdoors

between the earth and the machine

a room, defined by the shelter of the bucket, sits inside carved earth protected from above, steel and glass allow one connection to the outdoors

between the earth and the machine

The two previous studies led to a more in depth exploration of kitbashed architecture. In Southern California, where industrial infrastructure is commonplace, a yoga studio rests above Malibu. The studio is an articulated mass, tectonically activated by extant artifacts: rebar, HVAC duct, grader blades, diesel

fuel tanks, oil drilling pipe, and crane trusses. This thesis investigates a number of artifacts, their evolution, and the relationship between the architecture, industrial artifacts, and the natural environment.

The yoga studio is sited in Malibu, California. Malibu is a city along the pacific coast, spanning the length between Los Angeles to the east, and Ventura to the west. Although Southern California appears to be quite conscious of the environment, there is still a large amount of heavy industry in the region. Even though Malibu is naturally beautiful and well protected, there are still visible oil pumps on land, oil rigs in the water, and highway infrastructure elements everywhere. The formal and material nature of these industrial objects and buildings create an underlying fabric that feels familiar to anyone who has spent time in the region. Therefore, a proposed yoga studio, composed of industrial

artifacts integrated with new construction would not feel out of place. However, Malibu can be perceived as a place of excess. The average Malibu resident is extremely wealthy, and hundreds of extravagant homes populate the slowly degrading oceanside cliffs; no expense is spared for structure, materials, or design. These homes are some of the most egregious examples of lavish consumption in the country. The proposed yoga studio, sited on a bluff near Pepperdine University, off of Malibu Canyon Road directly contrasts these values. The studio presents the residents of this region with the idea that luxury and quality of space can be found through other means.

Malibu California, northwest of Los Angeles site: near Pepperdine University off of Malibu Canyon Road

an industrial playground

Malibu California, northwest of Los Angeles site: near Pepperdine University off of Malibu Canyon Road

an industrial playground

building site: hillside off of Malibu Canyon Road

building site: hillside off of Malibu Canyon Road

yoga studio: first floor plan

yoga studio: east-northeast corner

yoga studio: east-southeast corner

yoga studio: east-northeast corner

yoga studio: east-southeast corner

rebar latticework screening and filtering light around the yoga studio entrance

rebar latticework screening and filtering light around the yoga studio entrance

approach and entry

After arriving at the site, one follows an elevated steel walkway up the hillside. Ascending the hill, each footstep reverberates until the building is reached. The visitor approaches the entryway to the yoga studio by transitioning into a volumetric, lattice-like scaffold of rebar that creates an interstitial circulation

space between the building and the footpath. Similar transitions through delicate networks of steel articulate the yoga studio’s other circulatory areas as well. Here, the footpath extends through the lace-like field of steel to a cantilevered platform overlooking Malibu or an elevator that rises to the studio.

northwest corner: path cuts into the site to receive studio entrance path first floor planAs the elevator doors part, distant sounds of dripping water are heard and soft rays of sunlight penetrate a repurposed HVAC duct--both of which draw one toward the end of the gently curving entrance corridor. The floor slowly ramps upward and as one turns the corner, a reception space--conceived as a desert garden-opens up before them. Directly to the right, the repurposed HVAC duct offers a place to sit within its channeled light and also observe the interior garden panorama. To the center, a wooden floor deck floats above native succulents, cacti, and grasses. One can

now see the source of the splashing sound. Water flows down from hidden spigots onto a series of reused, steel grader blades and then into a large reflecting pool, adding a pleasant sonic dimension to the space devoted to contemplation.

To the left of the water feature is a service corridor housing storage, washrooms, and mechanical functions. At the far right end of the room, a series of parallel walls provide storage compartments and benches in support of visitor preparations for an upstairs yoga class.

first floor plan light draws one toward the main reception space

reception garden

first floor plan light draws one toward the main reception space

reception garden

section: first floor interior garden where one can look out over malibu while they prepare for yoga class

section: first floor interior garden where one can look out over malibu while they prepare for yoga class

After getting ready for their yoga session, the visitor exits the reception garden and the building to ascend the southern staircase. The interstitial space of the stair is encased in a rebar lattice and the steel grid acts as a screen between one and nature. Wind whispers gently through

the space and patches of sunlight warm the muscles in preparation for yoga practice. Moving through the volume, one is embraced simultaneously by the building components and natural elements. After ascending through the field, one arrives at the main yoga studio.

soutwest corner: showing the relatoinship between rebar grid and HVAC duct second floor plan

soutwest corner: showing the relatoinship between rebar grid and HVAC duct second floor plan

after preparing in the reception space, one climbs through this delicate rebar grid to enter the main

studio space

studio space

yoga studio: second floor plan

section: second floor studio space is framed by a collection of artifacts deployed as filters and aperatures

section: second floor studio space is framed by a collection of artifacts deployed as filters and aperatures

soft light and warm materials come together to promote relaxation in muscle and mind

A temple for mind and body connection, the studio aims to remove distractions in a thoughtful manner. Light is screened and diffused through found objects, natural elements offer a tactile engagement with nature, and warm materials promote a sense of relaxation. Walking through a corridor and into the studio, one sees four skylights projecting from the ceiling. The skylights are made of modified military fuel tanks that form part of a light well assembly in the ceiling. The deep walls of this shaft are painted white so that sunlight reflects inside the shaft, creating an indirect and

diffused light that fills the studio. On the roof, towers constructed from crane truss pieces hold fog nets. Water from sea fog condensates onto the nets then collects in pipes where it can then be fed into the skylight shaft. The water then drips onto glistening boulders positioned below. At the end of the room, a screen wall composed of a dense grid of former oil drilling pipes filters the outside world, providing light and connection to the outside without distraction.

a deep lightwell difuses light, while fog nets from above collect and drip water

second floor plan

yoga studio

a deep lightwell difuses light, while fog nets from above collect and drip water

second floor plan

yoga studio

rebar

HVAC duct grader blades

rebar

HVAC duct grader blades

oil drill pipes diesel fuel tank crane truss

oil drill pipes diesel fuel tank crane truss

the intersticial spaces of the rebar bind the north and south sides of the studio

the intersticial spaces of the rebar bind the north and south sides of the studio

Reinforcing bar grids are embedded within concrete walls and slabs, forming a unified structural system between the tensile strength of steel and the compressive strength of concrete. Before concrete is cast, the rebar grid has a unique and delicate tectonic expression. During construction, these hidden grids express spatial relations on their own, which is taken advantage

of in this architecture. Thin and light steel rods are used to define volumes where light and air can still permeate. In the yoga studio, the fleeting nature of rebar is called forth analogically in order to articulate in their use in transient nature entry and exit sequences. Moving through the latticework temporarily – one is neither inside nor outside.

the rebar grid is perforated by the stairs

the rebar grid is perforated by the stairs

When one enters the garden-like first floor of the studio, a wall is perforated by a former Heating Ventilation and Cooling duct (HVAC. This specific duct would normally be used in a massive air handling unit for a large building. It is nearly a room in itself, and the reflective nature of the aluminum raises questions about materiality and interaction with light within this ‘room’. Can one have a moment of stillness inside an object

originally designed for moving mass quantities of air? By cutting into the sides of the duct, the aluminum duct walls are folded down into legs, and a wood plank attached to these legs forms a bench. Sunlight entering from the top of the duct then spills from the newly cut sides, supplying light to native plants that cover the reception garden floor. One can now inhabit this unusual artifact and reflect on the interior garden.

sitting inside the HVAC duct room first floor plan

HVAC duct: respite in the garden

sitting inside the HVAC duct room first floor plan

HVAC duct: respite in the garden

section through HVAC duct light spills in though the top of the elbow

duct sides are cut and folded to become a bench

section through HVAC duct light spills in though the top of the elbow

duct sides are cut and folded to become a bench

As one walks further into the main reception area, there is an array of forty re-purposed grader blades mounted on the central wall. The original function of these blades was to level the ground before construction. Seeking to re-contextualize the blades through a new interaction with nature, the design intends to promote healing and reflection rather than destruction. Re-framing the blades’ interaction with nature, they no longer move solid earth. Water now flows gently down them, dripping into the small

koi pool below, sonically activating the space. As well, the thin steel blades are mounted vertically and arrayed against a mirror, yet the blades are angled so one cannot see themselves reflected when entering the reception space. One must ambulate around the room in order to catch a glimpse of their body reflected in the garden-like environment, thus creating a bodily awareness in preparation for yoga practice in which such awareness is paramount

water flows down found grader blades into a shallow pool stocked with koi first floor plan

grader blades: vision and sound

water flows down found grader blades into a shallow pool stocked with koi first floor plan

grader blades: vision and sound

section through grader water wall only after moving further into the reception space can one see their reflection

soft light and warm materials come together to promote relaxation in muscle and mind

oil drill pipe: screening and filtering

Steel, oil drill pipes extract the fluid resources of our earth every day across the world. The pipes exist as a device that allows us to take from underground places that we cannot touch with our feet. The destructive context of these pipes is shifted by reclaiming the pipes as lenses as tools for appreciating nature. Within the main yoga studio room, oil drilling pipes are modified by simply

cutting the pipes into two foot long sections and installing within the tube a small glass pane. The tubular windows are arranged in a grid pattern within the main studio wall, filtering a yoga practitioner’s experience with Malibu. The grid of windows diffuses light and perforates the view, connecting one to the outside world but without the distraction of an expansive panorama.

a small stage sits under the oil pipes for an instructor

a small stage sits under the oil pipes for an instructor

yoga practicioners stretch and pose in the soft and warm light of the studio

yoga practicioners stretch and pose in the soft and warm light of the studio

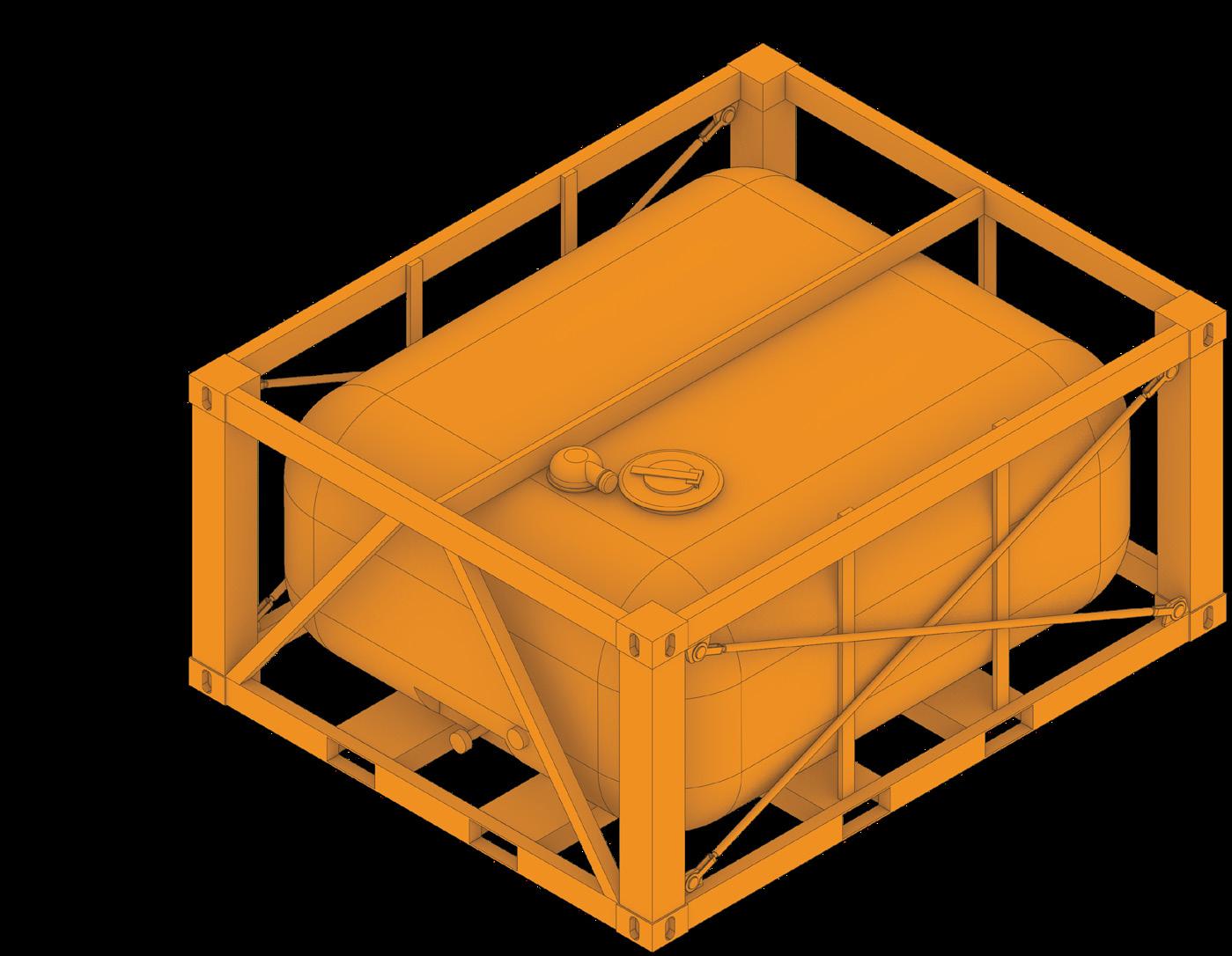

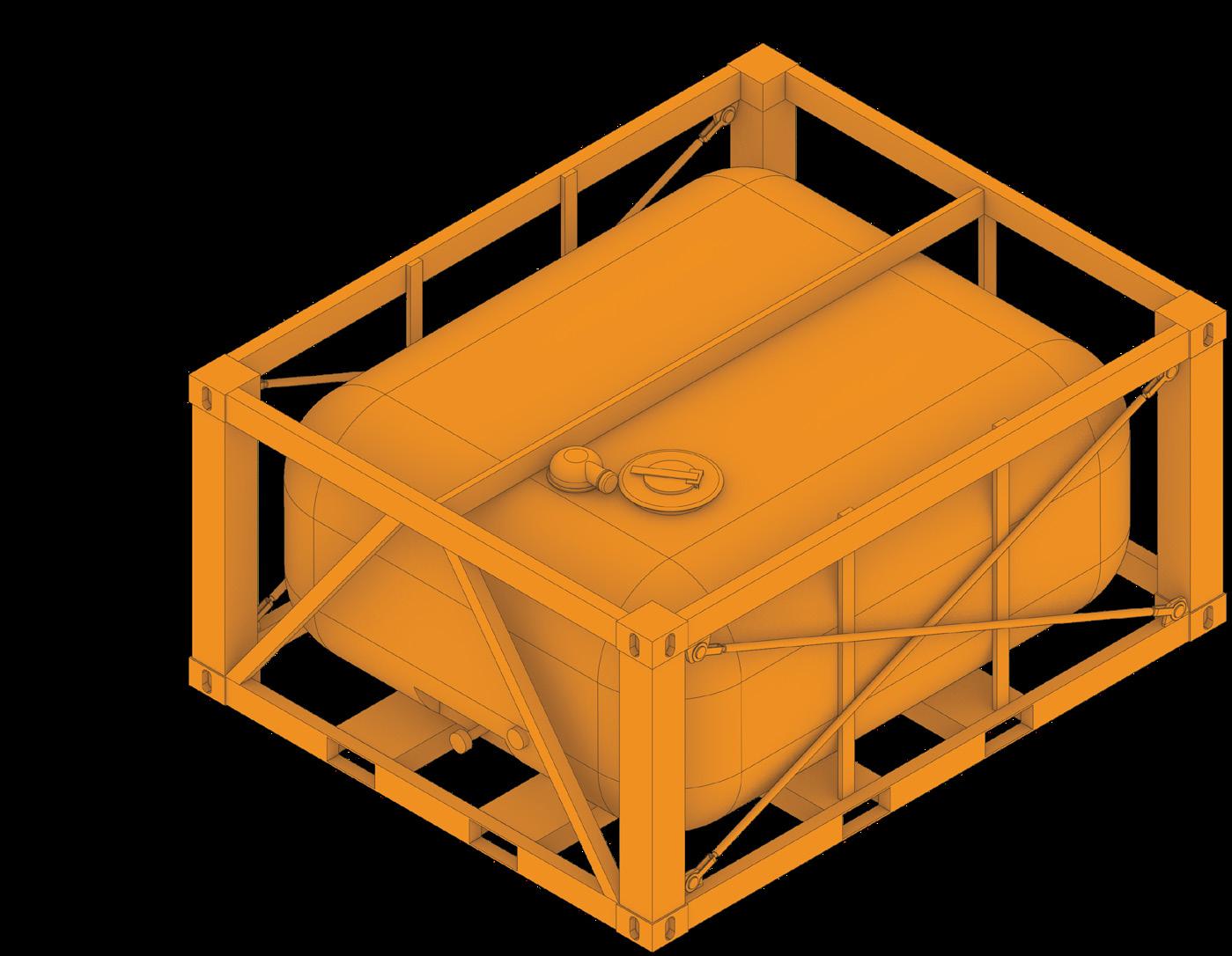

diesel fuel tank: diffusing from above

Across war zones and military bases around the world, pressurized steel diesel fuel tanks fuel machines of war. These tanks are composed of a skeletonized steel frame that protects a pressurized center tank. What if life-giving light and water could flow through this instrument of war instead of diesel fuel?

In the yoga studio, four fuel tanks are perched atop structural steel columns, elevating them for a more noble purpose. After depressurizing and cleaning the tanks, the center top and bottom of

the pressurized center section are cut away, leaving a void for light and water to pass through. The inside is painted white to aid in reflecting light from a skylight directly above. The former tank now bathes boulders and native grasses, and adjacent yogis in a soft sunlight. Water collected from fog nets on the skylight roof shaft trusses drips onto boulders found on the site during construction. These fuel tanks are now re-contextualized and elevated to be vessels for illuminating nature and sparking human motion.

west elevation: the modified crane truss towers contrast the mass-like form of the studio, drawing a juxtaposition between the found artifacts and the new

west elevation: the modified crane truss towers contrast the mass-like form of the studio, drawing a juxtaposition between the found artifacts and the new

crane truss: icon from near and far

A crane is an icon. When viewed from afar, the crane’s trussed form symbolizes that something is under construction-being put together piece by piece. This tectonic reading of assembly is central to the thesis of this project and can be capitalized on by recontextualizing these iconic truss structures. Upon the roof of the studio, truss elements from aged cranes are

re-fabricated into towers. Now symbolizing and expressing the tectonic and assembled nature of the yoga studio. These towers practically function as skeleton frames for fog nets, harvesting water from Malibu’s Pacific Ocean fogs for the interior garden. From outside the building, the cranes function as an icon of assembly, hinting at the assembled nature of the project from near and far.

by peeking through the skylight, one can observe the fog net towers.This thesis has shaped my thoughts around making as much as I have shaped it. A fascination with industrial and mechanical objects has led me to a deeper understanding of what it means to reuse, assemble, and kitbash. So often today, architects, designers, and makers look toward new techniques and emerging processes for making novel objects. If more people addressed evaluating extant resources as described in this thesis, we could make a small societal step towards less consumption and production. Kitbashed design holds weight with environmental concerns. These methods by their very nature preserve objects that already have high amounts of embodied carbon, and keep others from degrading in landfills or poisoning water.

Such projects require a certain amount of custom fabrication and one-off work, yet each fabrication job could support a local economy; fabricators and craftsmen, as well as materials sourced from local industry and infrastructure can diminish our reliance on outside resourcing. In the future, I hope to reengage these ideas through furniture design. Making furniture would allow for me to address the methods at a human scale, with techniques already familiar to me and with a discrete final function for the piece.

The ideas explored in the thesis are evident and inspired by the projects of others before me. In architecture, some of these ideas have been explored before. In Thom Mayne’s 6th Street House, he brings industrial artifacts into an existing home. The re-contextualizaion of these artifacts, and their contrast with the context of a domestic space, creates an interesting tension between man and the artifact. In film, Mad Max depicts a dystopian future where vehicles and buildings are cobbled together from the remnants of an industrialized society. While the film is dystopian, the novel assemblages carry a tectonic, material, and functional nature similar to my work. Forgotten relics of an older age are repurposed, taken out of context, and combined in new ways.

I hope to continue working with found artifacts far into the future, and maybe others will as well.

Sixth Street House, Morphosis

Mad Max: Fury Road Concept Art, Brendan McCarthy

Sixth Street House, Morphosis

Mad Max: Fury Road Concept Art, Brendan McCarthy

This final section of the book contains a collection of process sheets and models. These works are presented non-chronologically. Sketching by hand and three-dimensional digital modeling are the primary methods by which I explore ideas. The following collection is a network of drawings and models that reflect my thinking through the thesis.

Author: Adobe Stock

Scrap recycling plant

Author: MOMA

Bicycle Wheel Marcel Duchamp, 1951

Author: Hunter Courtney

Santana Jean Tinguely, 1966

Author: MOMA

Bull’s Head Pablo Picasso, 1942

Author: Lucasfilm

Millenium Falcon model, 1977

Author: Adobe Stock

Scrap Steel Pile

Author: Adobe Stock

Abandoned Water Tower

Author: Ricardo Gomez Angel

Steel Man at Work, 2020

Author: Adobe Stock

Sierra Nevada Landscape

Author: GovPlanet

Rahm 30 HD Load Haul Dumper, Runner

Author: M&M Manufacturing

Large HVAC Elbow

Author: GovPlanet

Steel grader blades

Author: GovPlanet

Truss Crane`

Author: Adobe Stock

Steel Oil Drilling Pipe

Author: GovPlanet

Isometrics MFT-205 Sixcon Fuel Tank

Author: Morphosis

Sixth Street Residence 1992

Author: artbrendan.com

Brendan McCarthy Mad Max Fury Road, 2015