WELCOME MESSAGE

Despite the challenges posed by the global COVID-19 pandemic, HKU’s research has continued to grow. Our researchers have an impressive track record in securing funding through competitive funding schemes, publishing their findings, and translating their research for the benefit of the local and global community. In 2021, Clarivate named 31 HKU scholars among the world’s most highly cited researchers and 139 in the world’s top 1% of scientists. Outstanding researchers from across the globe have joined HKU. HKU researchers are garnering recognition from prestigious academies, with our scholars holding more than 90 memberships of about 25 academies around the world as well as in Hong Kong and Mainland China. Our researchers have also received a wide range of international, national and local honours and awards. Notable examples include the Porter Medal, the American Chemical Society National Award, State Natural Science Awards, Future Science Prizes, Excellent Young Scientist Fund awards and Changjiang Scholarships.

In this magazine, our researchers will share with us their significant research accomplishments and subsequent societal impacts upon successful downstream translation of their newly developed technologies. I am excited about our future and incredibly proud of the dedication and perseverance our research community has shown and their positive contributions. I wish everyone another successful year for research, grant application and publications!

Prof Max Zuojun Shen Vice-President and Pro-Vice-Chancellor (Research)

HKU Mathematics Professor Ngai-Ming MOK awarded the 2022 Future Science Prize in Mathematics and Computer Science

AWARDS RESEARCH GRANTS

HKU Mechanical Engineering Professor Xiaobo Yin wins Xplorer Prize 2022

276

RGC General Research Fund/Early Career Scheme 2022/23 projects, HK$248.8M

Health and Medical Research Fund 2022/23 projects, HK$94.9M

80

HKU and ASTRI join hands to expand R&D talent pool in Hong Kong to inject new impetus into development of innovation and technology

5

RGC Theme-based Research Scheme 2022/23 projects, HK$168.3M

NSFC Excellent Young Scientist Fund (Hong Kong and Macau) 2022 projects, RMB$20M 10

16

NSFC Young Scientist Fund 2022 projects, RMB$4.8M

HONOURED PATHOLOGIST MAKES HEADWAY AGAINST LIVER CANCER

The ground-breaking research on liver cancer by Professor Irene Ng Oi-lin, Loke Yew

Professor in Pathology and Chair Professor of Pathology, has earned her recognition as one of the top female scientists in the world by Research.com in its 2022 ranking of the top 1,000 female scientists.

rofessor Ng’s achievements, all homegrown at HKU, include identifying and characterising liver cancer stem cells, identifying biomarkers for liver cancer and, more recently, analysing treatment, in particular why immunotherapy works in some patients and not others. She and her team have also developed tools to identify genes, mutations, expressions and other features at the single cell level.

Her track record has also resulted in strong funding supporting, including not one but two Theme-based Research Scheme (TRS) grants, while her labs have been a breeding ground for rising talent.

This impactful body of work emerged rather humbly from Professor Ng’s days as an intern following graduation with an MBBS from HKU. One day she was sent to brief a pathologist on a patient who had just died and to observe the autopsy. It was routine work, but the result spurred her curiosity.

“The X-ray had shown a mass in the thorax that we thought was a tumour. However, the autopsy showed it was not cancer, but a bulge of the aorta. This made me interested in specialising in pathology because it can provide the final verdict of what is happening in the patient. It’s like a bridge between clinical medicine and basic understanding of disease,” she said.

Professor Ng was recruited to HKU shortly after her internship and initially did simple research – case report series – focused on the stomach and the gut. But her interest began to pivot to the liver, a hugely important organ because it detoxifies the blood and creates and stores nutrients.

“I became more interested in the liver for several reasons. It is a fascinating organ because it is the major factory of the body. Another issue is that liver disease is a major disease in Hong Kong due to Hepatitis B virus infection, and we also have a very high incidence of liver cancer here. And third, our department has a long and excellent history in liver research, particularly cancer research,” she said.

Her timing could not have been better. In the 1990s the government started to allocate more funding to research, enabling her to recruit staff and obtain quality materials to do more sophisticated work. Her work since has tackled liver cancer from three angles.

One angle is to investigate the underlying mechanistic reasons for why people develop liver cancer and identify possible molecular targets for drugs. Another is to identify biomarkers in the cancer tissue or blood, such as gene mutations, that can reveal why one person may respond better to treatment than another. And third is to look at treatments themselves, particularly immunotherapy drugs. Professor Ng and her team have also developed tools that

Cancer stem cells are like the general of the battle, while the other cancer cells are like soldiers. In order to win a battle, it’s important to capture the general.

can analyse a single cell to identify gene expressions, mutations, and other factors that contribute to the development of liver cancer.

The findings from these investigations have helped to advance understanding of the disease, especially cancer stem cells which can drive tumour formation and cause relapses. “Cancer stem cells are like the general of the battle, while the other cancer cells are like soldiers. In order to win a battle, it’s important to capture the general,” she said.

Professor Ng and her team have identified new biomarkers for cancer stem cells in the liver that were not reported before. For example, about a decade ago they identified the biomarker CD24+ for a subset of cancer stem cells that is responsible for chemoresistance, metastasis and tumour recurrence in liver cancer. The discovery provided new insight on tumour progression and showed a path for developing future treatments, since liver cancer patients whose tumours have high CD24+ expression are at significantly higher risk of tumour recurrence and metastasis and have a much lower survival rate. The study also showed how CD24+ cancer stem cells initiate tumour development and self-renewal.

Her use of single-cell analysis has also provided new insights on the interaction between tumour cells and immune cells in the tumour microenvironment. Through this method, the team were the first to identify the immune checkpoint pair, TIGIT and NECTIN2, in liver cancer, thereby revealing an important target for treating liver cancer.

Cancer stemness, which is separate from cancer stem cells, is another important focus of her research. Almost all cancer cells possess cancer stemness, which enables them to replicate and produce differentiated cells. Genetic mutations can empower stemness in cancer cells so identifying such mutations is important for developing treatments. Professor Ng showed that the tuberous

sclerosis genes, TSC1/2, are frequently mutated in patients with liver cancer and, significantly, can be easily detected in patients’ tissue.

The latter findings emerged from her 2016 TRS grant called “Understanding cancer stemness in liver cancer – From regulation to translational applications” and the success of that work led to the award of her second TRS in 2022 on “Delineating and translating the mechanistic determinants to improve the clinical management of liver cancer”, which is taking forward the findings, including those on immune checkpoint pairs, to establish the effectiveness of immune checkpoint inhibitors in improving diagnosis and treatment outcomes for patients.

Professor Ng credits the working environment at HKU, where she has established tissue and blood banks of vast numbers of samples, and strong support from the University and the medical faculty, as factors in her impact and success. She also applauds the input of her team members and her collaborators in Hong Kong and Mainland China through the State Key Laboratory of Liver Research, of which she has been Director since the lab was founded in 2010.

“I have been very lucky to have excellent team members to generate or find new data and produce novel findings. Some of them are now associate professors or even professors at HKU or other institutions. It’s very rewarding to see young people come here green and to watch them mature and develop with us. It makes me feel young, too,” she said.

Research.com announced its ranking of the top 1,000 female scientists in the world in November 2022 based on multiple factors including their h-index (productivity and citation impact of their publications), proportion of contributions within their given discipline and awards and achievements. Professor Ng ranked 8th in China and 517th in the world.

NEW DRUG COMBINATION OFFERS HOPE FOR LIVER CANCER OUTCOMES

Liver cancer is notoriously difficult to treat. Even when caught at an early stage, the fiveyear survival rate is only 35%. One of the main problems, as highlighted in ongoing research by Dr Stephanie Ma, Associate Professor in the School of Biomedical Sciences, is that treatments do not usually eradicate cancer stem cells, which are the progenitors of the bulk of cancerous tumour cells.

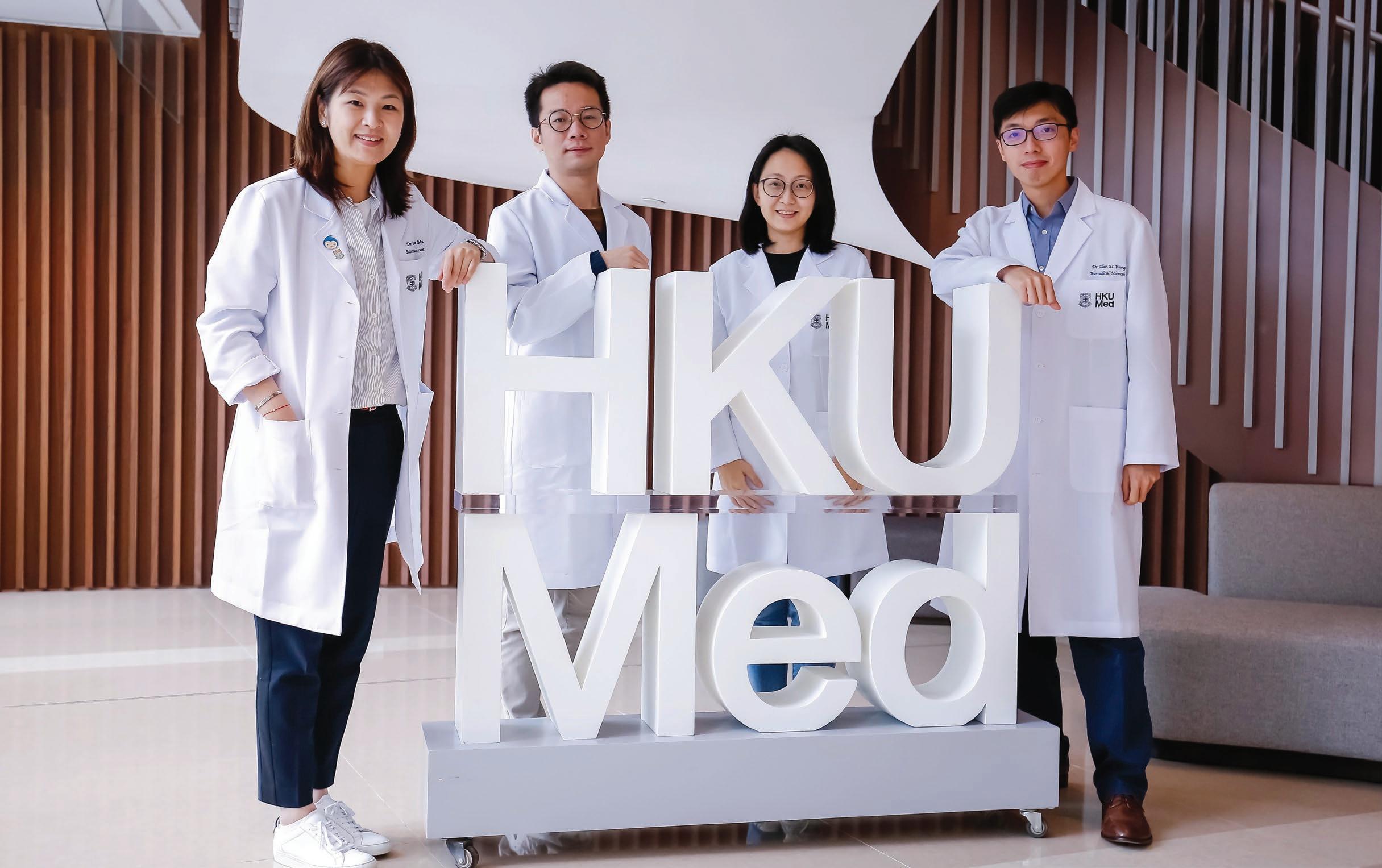

But now, a new discovery by Dr Ma and her colleague, Assistant Professor Dr Alan Wong Siu-lun, who is expert in applying technology to decode the genetic bases of human diseases, offers patients a glimmer of hope.

They have shown that two known drugs, sorafenib and ifenprodil, when used in combination, can target cancer stem cells and inhibit their activities. This is important because often, cancer treatments will kill off actively proliferating tumour cells but not the cancer stem cells. The latter can then self-renew and differentiate into different cell types and repopulate the tumour over time.

“We believe cancer stem cells are the root of tumour recurrence and therapy resistance,” Dr Ma said. “Repurposing drugs saves the cost and time otherwise needed to develop new therapeutic agents with uncertain efficacy and safety profile, and increases the chance of clinical translation of the findings from bench to bedside. Our work has identified a potentially useful combination of approved drugs to be further tested for treating liver cancer, which could possibly save or prolong a patient’s life.”

While Dr Ma provided the cancer expertise, it was Dr Wong’s technological expertise that made it possible to sift through mountains of data to pinpoint cancer gene targets and the drugs that could act on them. Note that the drugs he was investigating were not necessarily cancer drugs – they just happen to act on the gene targets.

Dr Wong used the CombiGEM-CRISPR v2.0 screening platform which marries CRISPR’s ability to scan the entire human genome of 20,000 or so genes and to knockout target genes, with CombiGEM’s ability to study multiple genes at the same time. The focus was on genes known to maintain cancer stem cells.

“In a lot of cases, genes work together. So we used a DNA barcoding strategy to look at combinations,” he said. “If we can knock out two or even three genes together and remove them in one shot, then maybe this could cause the liver cancer cells to die.”

They identified a handful of gene combinations and compared them with a catalogue of drugs, to see which drugs could inhibit them. The list of drug candidates was quicky narrowed down to sorafenib and ifenprodil after eliminating drugs that were toxic or still experimental.

“Alan did his magic with the CombiGEM-CRISPR and I helped to validate the results within multiple hepatocellular [liver] carcinoma cells, patient-derived organoids and patient-derived mouse models. We had two very different sets of expertise coming together,” Dr Ma said.

The dual-target approach was validated by the boost in performance to sorafenib, which is an FDA-approved molecular targeted therapy and widely used. When used on its own, sorafenib unfortunately has been found to enrich

HKUMed research team identifies new drug combo for liver cancer via CRISPR-Cas9 screen. The research team includes (from left): Dr Stephanie Ma, Associate Professor; Dr Xu Feng, Post-doctoral Fellow; Dr Carol Tong Man, Research Assistant Professor and Dr Alan Wong Siu-lun, Assistant Professor, School of Biomedical Sciences, HKUMed.the cancer stem cell sub-population. But when ifenprodil is added, cancer stem cell signalling decreases and the subset cannot tolerate the extra stress.

“The stress response activates cell cycle arrest and also decreases a very important pathway of self-renewal called WNT, which we know is important in driving cancer stemness,” Dr Ma said.

Interestingly, ifenprodil is not a cancer drug but a vasodilator used to improve blood flow to the brain in patients with cerebrovascular disease. It is not FDAapproved but has been used in some patients in Japan and France and is considered safe in humans.

Dr Ma said the mechanism that causes the two drugs to inhibit cancer stem cells is not clear, but understanding mechanisms is not the main goal here – what matters most is that the treatment works and is safe for patients.

The scientists have applied for a non-provisional patent in the US to signal their discovery, but they also point out there is more work to be done, such as tests of dosage and other drugs and clinical trials, before the treatment could get a green light for patients.

In the meantime, Dr Ma’s team is pursuing research on immune cells in the microenvironment around cancer stem cells. Immunotherapy to treat liver cancer can be highly effective – but only in about 15 per cent of patients. The rest do not respond. “We have evidence to show cancer stem cells can contribute to an altered immune landscape and lead to immune evasion, and we have separate projects to look at the interaction of cancer stem cells and immune cells,” she said.

Dr Wong, for his part, hopes to capitalise on the ability of the CombiGEM-CRISPR technology to identify druggable genes far more quickly than in the past, when it could take years to sift through possible combinations and also be costly.

“This platform has broadened our scope in searching for effective combinations of actionable targets and approved or repurposed drugs in a rapid and simple manner, and it could be extended to other cancers or diseases in future,” he said.

In a lot of cases, genes work together.

So we used a DNA barcoding strategy to look at combinations.

MIND YOUR LANGUAGE: FINDING BETTER WAYS TO TALK ABOUT HEALTH

A patient has cancer and their doctor suggests they talk to a priest. The doctor’s intention is for the patient to talk to someone experienced in counselling. But in popular Western culture, priests are often depicted coming to the scene to administer last rites. To the patient, the advice sounded as if death was imminent. (It was not.)

This case popped up in research led by Dr Olga Zayts. Associate Professor in the School of English, who specialises in health communications and recently received a Collaborative Research Fund (CRF) grant for a major project in this field. She has been looking not only at cancer cases, but communications relating to COVID-19, genetics, mental health and end-of-life care.

“Effective communication in any of these contexts is about how to communicate risk. You’re dealing with different kinds of people and different backgrounds, so we look at language and the cultural and socio-cultural issues related to it,” she said. “Of course, you can’t teach people how to speak, you can’t tell them to always use ‘x’ or ‘y’ approach because language is very much context specific. But you can make them aware of the different forms and functions of language and how they can use that.”

Dr Zayts began specialising in health communications more than 15 years ago when she raised the issue of genetic counselling with HKU’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Genetic counselling is a good example of how one approach does not fit all because counsellors can deal with everyone from a deeply religious pregnant Catholic domestic helper to a science-literate pregnant nurse.

The Department was immediately interested and they began a long-term collaboration to improve genetic counselling. Dr Zayts now teaches on the medical faculty’s Master of Medical Science (Genetic Counselling) programme and is currently writing a book funded under the Humanities and Social Sciences Prestigious Fellowship Scheme called Talking Genetics: Intersections of Language, Culture and Genetic Literacy in Intercultural Genetic Testing and Counselling Contexts.

About five years ago, she also started to branch into mental health communications after meeting with a new NGO, Mind HK, that wanted to support research, training, outreach and other activities to help improve mental health in Hong Kong. She initially advised them on their surveys and research and has since become a board member and collaborator – the charity has funded a PhD position under Dr Zayts to investigate mental health destigmatisation campaigns in the city, which have a strong linguistic component.

“The idea is that in the sociocultural context of Hong Kong, there needs to be a process of cultural adaptation,” she said. “From data and interviews with people employed in Hong Kong, we can see three levels of stigma – the societal, institutional and family levels. If people on the one hand are willing to open up about mental health problems but on the other hand are not seeking support because of these barriers, it can impact them in many ways.”

The CRF project also focuses on mental health. Working with colleagues from HKU, Chinese University of Hong Kong and City University, and the workplace mental health organisation City Mental Health Alliance, she is studying the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on university graduates transitioning to the workplace. Surveys and interviews are being undertaken with three cohorts of graduates, university administrators and companies to understand a range of issues, including the gap between how students are prepared and what employers expect, graduates’ mental health needs, and the most effective ways to prepare for workplace transition during crises. The outcome is expected to be a digital repository of information, tools and resources based on linguistics and psychology.

(from right to left): Dr. Olga Zayts Prof. Diana Slade, Australian National University Prof. KK Luke, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore Dr. Susan Bridges, Director of CETL, HKU“The transition from university to the workplace is a tricky time even when there is no pandemic or financial crisis; there is always a gap in skills between what universities provide and what workplaces require. We have been asking the graduates about their experiences and so far, a lot of them feel unprepared in terms of digital skills and team meetings – which are linguistic focused. For instance, how do you build relationships when the team only meets online?” she said.

The fallout from the pandemic also runs through a project analysing the mental health discourses of working women in an online support group, and on more wide-ranging studies about end-of-life communications, which she is overseeing with a post-doc fellow, Dr David Edmonds.

“COVID-19 has made end-oflife communication a lot more important. Normally you would not tell a patient they are dying over the phone, but that’s what has happened during the pandemic. And people you would not expect to die are dying, sometimes they are alone and they are saying goodbye to their families over tablet computers,” Dr Zayts said.

She and Dr Edmonds recently wrote a commentary about this for the journal Qualitative Health Communication with a young UK doctor, discussing such issues as moving from face-to-face to video-mediated communications, communicating inherent uncertainty in the prognosis for COVID-19 patients, and fasttracking medical graduates into the workforce, who often feel ill-prepared for the communication demands of their job.

They are also in the early stages of a project with Clinical Assistant Professor Dr Jacqueline Yuen Kwan-yuk from HKUMed, who specialises in geriatrics and palliative care, on the interactions between palliative care clinicians, patients and their family members. So far, the findings have shown that assumptions about the discussion of death in Chinese culture are misplaced.

“There is a perception that the topic of death is avoided because people are afraid it will touch them. But in looking at the interactional data, we find people do talk about death quite openly. They use explicit death talk to downplay the end of life and construct social relationships in disclosing a terminal prognosis. The language is more implicit when they talk about concerns and deal with familial conflict,” she said.

Dr Zayts has also been expanding HKU’s capabilities and collaborations on health communications, both locally and internationally. In 2019 she led the formation of the HKU Research and Impact Initiative on Communication in Healthcare (HKU RIICH), and also led HKU in being a founding member of the Interdisciplinary Initiative on Communication in Healthcare that includes Harvard Medical School, Australia National University, Nanyang Technological University, University College London, Lancaster University and Brisbane University of Technology.

“Our aim is to conduct evidence-based research and transform healthcare communication practices and education in Hong Kong and internationally. Collaboration is a very common model in social science and medicine but less common in linguistics. But our work is all about teamwork,” she said, and not just with scholars in her own field.

“Compared to other countries, the interest from medics in Hong Kong is absolutely amazing. People here understand that communication is important, that they face difficulties because they deal with a multicultural, multilingual patient population. And they are also very keen to learn. I’ve never struggled getting access to data and getting people interested on the medical side,” she added.

Our aim is to conduct evidencebased research and transform healthcare communication practices and education in Hong Kong and internationally.

CHARGING UP THE ELECTRIC VEHICLE MARKET

Electric vehicles (EVs) offer health and environmental benefits because they reduce roadside emissions. But getting consumers to switch away from combustion engines and adopt EVs has not been straightforward. Not only do EVs tend to cost more, but consumers worry there will not be sufficient charging stations to keep them on the road. Governments have responded by building charging stations themselves and incentivising automakers to do so with subsidies, but there has been little examination of the most cost-effective approach. Now, a new study by scholars at HKU, Fudan University, University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and Shanghai University offers clarity.

As it turns out, when the target for EV adoption is high, the best way to get more stations built is to subsidise consumers directly when they buy the vehicles. The underlying logic is that as the industry makes more money, it will invest in more stations to expand the market base further.

“Getting consumers to adopt innovative products such as EVs requires some nudging, Different countries have developed different EV purchasing incentives and subsidies for the construction and/or maintenance of EV charging stations. Currently, both automakers and governments are planning to build extra charging stations so there is a need to develop a coordinated plan to achieve adoption targets in the most cost-effective manner. This is the motivation of the study,” said HKU Vice-President (Research) Professor Zuo-Jun Max Shen, who collaborated on the paper with his former PhD student and postdoc fellow and lead author Dr Jiayi Joey Yu, as well as Professor Christopher S Tang of the UCLA Anderson School of Management and Dr Musen Kingsley Li of Shanghai University.

The researchers looked at various scenarios that factored in the aggressiveness of the EV target, the cost of construction, whether government and automaker construction costs were independent of each other, and the impacts of subsidies to automakers and to consumers.

They also drew inspiration from real-life examples. In China, for instance, the government has set a target of achieving 20

per cent EV penetration by the end of 2025. To do that, it is investing more in charging infrastructure and reducing EV purchase subsidies, which will be phased out in 2023. The government-owned State Grid Corporation of China has been building charging stations and by the end of 2019 had built 93,700 stations in 171 cities in 19 provinces.

In the US, federal and state governments offer different incentive programmes to consumers. The Biden administration has also proposed to build 500,000 new EV charging stations (compared to about 50,000 in 2022) and some automakers are also building or plan to build stations, such as Tesla and Volkswagen.

These targets require huge investment. By 2030, the EV industry in China, the US and Europe will need about US$50 billion in capital investment to construct 40 million EV chargers, according to a study by McKinsey.

“In the past, governments have focused on offering a per-unit purchase subsidy to entice consumers to buy EVs, while automakers have focused on building charging stations and arriving at an optimal selling price. These separate aims have not required explicit co-ordination,” the authors said.

“But when the government is committed to achieving a certain EV adoption target and plans to construct extra charging stations, it must co-ordinate with automakers to ensure the total number of charging stations is planned optimally.”

Left: EV Charging Stations Constructed by EV Automakers (e.g. Tesla)

Left: EV Charging Stations Constructed by EV Automakers (e.g. Tesla)

That co-ordination could involve subsidies – either to the private firms themselves or to consumers – depending on the EV adoption target and construction costs.

The no-subsidy option is best when both the EV adoption target and construction costs are low, in which case the government does not need to take action. Even if they rise to a moderate level, the government can simply react by building extra charging stations as needed.

However, if both the adoption target and construction costs are high, then the government’s best bet is to offer a per-station construction subsidy to the firm. Where firm and government construction costs are independent (meaning the cost of one party is unaffected by the number of stations built by the other), the government could also continue to build stations alongside the firm. Where they are dependent, the government’s best option is to simply offer a per-station subsidy and bow out of building any stations itself, leaving that work to the firm.

While these measures can help to increase the number of EV charging stations, the authors argue that a more powerful effects will result if the government subsidises consumers directly to encourage EV ownership. “This is more cost-effective for the government than offering a per-station subsidy to the automaker,” they said, although governments could also choose to offer both subsidies, particularly if construction costs incurred by firms are dependent on the number of government-built stations.

And there is icing on the cake because a subsidy to consumers both encourages EV adoption and improves consumer welfare.

Moving forward, the authors suggest that governments could further meet environmental and consumer welfare goals by using regulations to meet carbon emission goals, giving subsidies or incentives for the development of EV batteries with longer driving ranges, and improving coordination on the location of EV charging stations.

Dr Yu also notes that their findings could have implications beyond EV adoption.

she said. Dr Yu is now Associate Professor at Fudan University. The study was published in Production and Operations Management

More generally, when the government faces the issue of promoting a new technology to consumers, it can consider offering the combination of purchase subsidy and building infrastructure to achieve the adoption target with minimised cost,

RETHINKING THE REGULATION OF CRYPTOASSETS

[Note: it is written based on an interview with Syren Johnstone of the Faculty of Law conducted in May 2022.]

In April this year, Fabio Panetta, an executive board member of the European Central Bank, gave a speech about crypto-assets in which he compared them to the American Wild West of the 19th century, slammed their high electricity consumption, said they were as dangerous as the sub-prime mortgage crisis of 2007, and called for them to be tightly regulated.

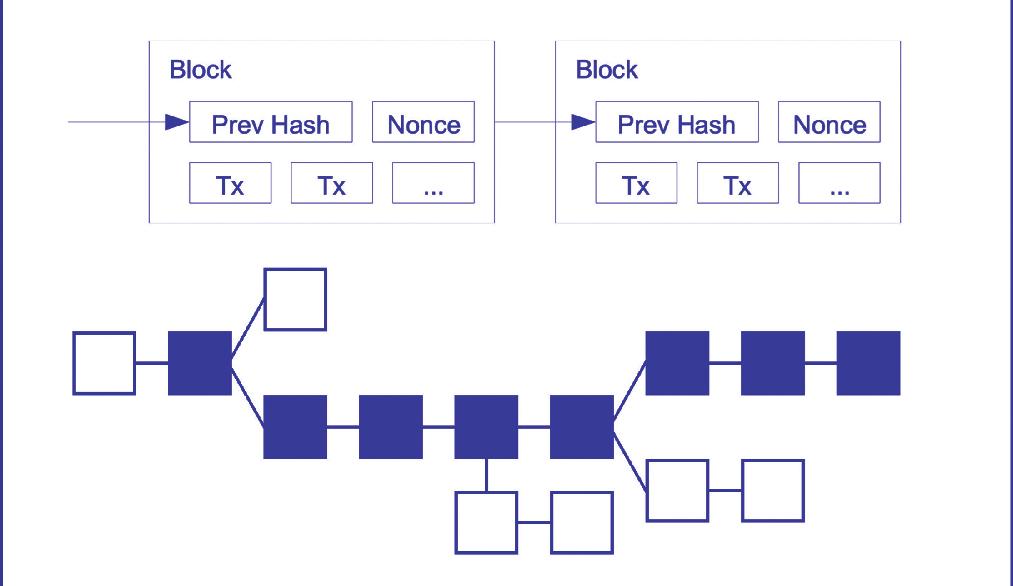

The harsh criticism was met with disbelief by Syren Johnstone of the Faculty of Law, whose recent book, Rethinking the Regulation of Cryptoassets: Cryptographic Consensus Technology and the New Prospect, challenges how we should regard and regulate crypto-assets and crypto-currencies, such as Bitcoin and Ethereum, and the blockchain technology that underpins them – in particular, that we need to think beyond their role in the financial sphere.

“When I heard those comments, I thought, hang on a minute, everything burns electricity. The mortgage crisis in the US happened in a heavily regulated banking sector. And the Wild West – well, what came out of that was California, the world’s fifth largest economy,” he said.

“This demonising language from a central banker is not rational. It only sees the world in one way, which is that central banks must exist. But I don’t see this as either/ or. We can have other things alongside central authorities that allow communities to take more ownership of the things they are invested in without being beholden to financial regulation.”

Blockchain technology is unlike financial instruments in that it can turn information into value that can be exchanged, and it enables users who do not know each other to make collective decisions about products or services based on factors that extend beyond accounting or finances.

To illustrate how this can work, Mr Johnstone gives an analogy with a favourite restaurant that faces difficult decisions, perhaps because the rent has been hiked up. Through blockchain, the restaurant owner could better connect with customers and suppliers cum stakeholders to help decide on its future.

“If the restaurant owner can connect to everybody and say, ‘the rent is now too high, do you want me to continue or not?’ it becomes a group-based decision. The group can decide whether to put money into the restaurant from time to time, whether it should move to another location, whether it should change the menu. Individual members of the community take part in something that is of value to the community,” he said.

“If you look at everything through the lens of finance, everything becomes a piece of finance. The restaurant stops being about good food, good service, pleasant music or ambient lighting – it just boils down to profit and loss.

“And that’s the problem with treating blockchain only as a financial or business product. You fail to see that it allows people to participate in shared interests in different ways. The technology is not just there to service what we are already doing, it’s there to change the way we do things. There are some very relevant opportunities here in relation to sustainable development goals.”

His book argues that while regulation of some sort is necessary to protect consumers, the focus should not be on the product – such as a particular token or crypto-

currency – but the underlying technology and what purpose it can serve.

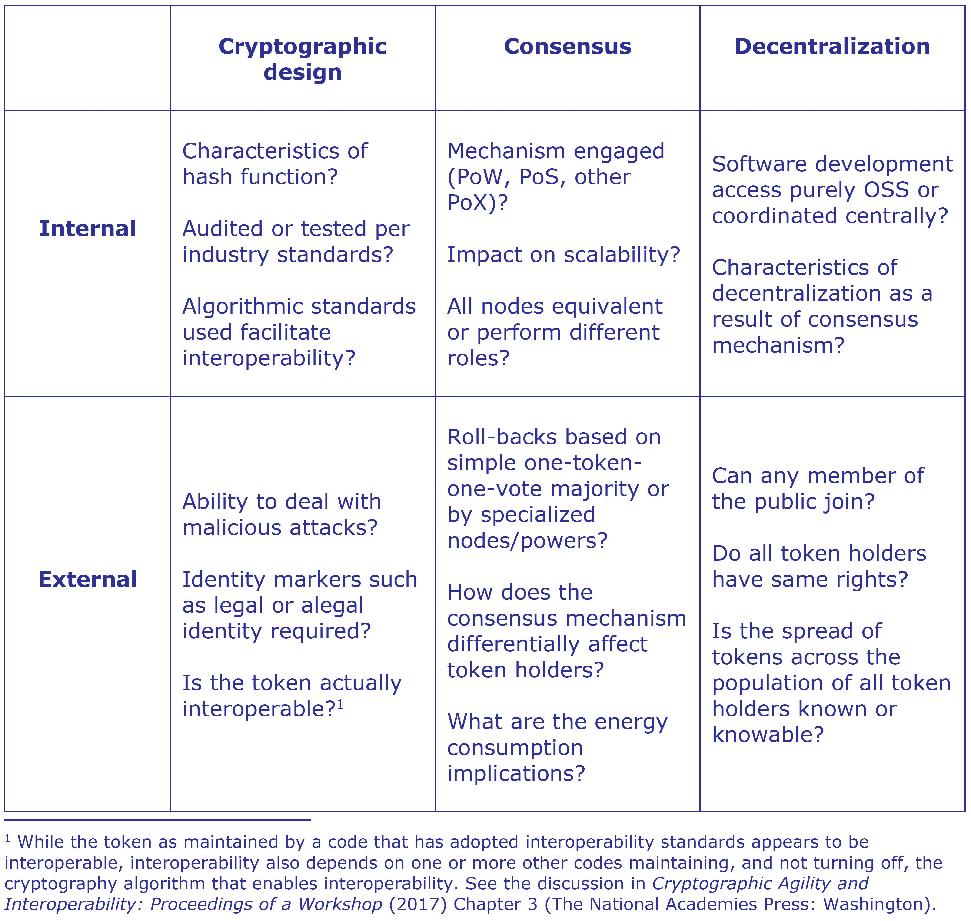

“If a blockchain regulator were to ask questions about how consensus is formed, we could get more sustainable answers about what kinds of mechanisms benefit what kinds of participants in a network,” he said. And from there, regulations could be made that would protect users.

“By imagining blockchain as a much more general purpose technology that goes well beyond the parameters of finance, we can then face the usual issues concerning consumer protection. When I think about regulation of the blockchain space, I think about it in the broadest minimalist sense. We need to stop consumer abuse and fraud and protect general values in society.”

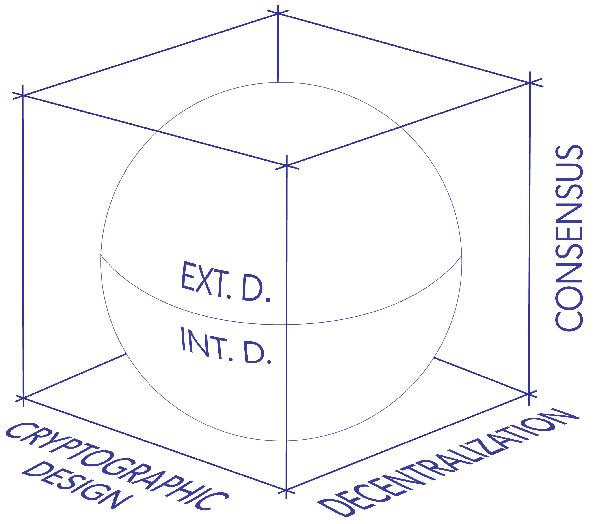

In his book, he adopts a regulatory model that operates along three axes of decentralisation, cryptography and consensus (which can be thought of as governance or voting methods). Different designs of these technical factors can lead to different outcomes – for instance, one method could benefit users who hold tokens for the longest period of time, while another could benefit those who hold more tokens for a shorter period.

He also argues for a global consensus on regulation, which is currently in a state of flux. Some jurisdictions are taking a wait-and-see approach towards blockchain, which Mr Johnstone said was reasonable given the technology is in an early stage of development. But others have handed it over to financial regulators, who are becoming more aggressive in applying existing laws to crypto-assets.

For example, rather than keeping watch and acting only against blatantly egregious cases, the Securities

and Exchange Commission in the US has gone after Telegram and Ripple, arguing their token offerings were unregistered securities. “There’s a continuous call from industry asking for clarity on the regulation of cryptoassets so they can comply. Otherwise, they worry that they may try something new and find after a year or two’s time that the SEC finds fault with what they did,” he said.

Mr Johnstone argues that individual financial regulators are not equipped to deal with blockchain, not only because of their limited focus on finance, but because the technology is borderless. Higher-order questions also need to be asked about the principles and aims in regulating blockchain.

“Ultimately, I think the only way we are going to find answers to those questions is if the G20 does something,” he said. “Different parts of the world are progressing at different rates and in slightly different ways, and I don’t think we are going to get where we need to be if each jurisdiction pursues its own path.”

There is precedence for this both in the modern day and in the past. After the 2008 global financial crisis, the regulation of credit rating agencies became more harmonised at the behest of the G20. Sustainable finance is also now on the G20’s agenda.

Further back in time, private enterprise and the corporate entity arose only in the waning years of the feudal system in Europe; laws were subsequently enacted to protect a new class of creditors and shareholders, he said.

Mr Johnstone also believes that society should consider blockchain as it does transport –“The evolution of transport has changed the way society works and connected towns and people and countries. I think of blockchain like a transport analogy. It can open up new areas of community and develop new economics around communities formed in the blockchain space,” he said.

“Blockchain can also definitely be used for finance – it’s great for finance. But we shouldn’t pigeonhole it there, and that’s what we are currently doing.”

Rethinking the Regulation of Cryptoassets: Cryptographic Consensus Technology and the New Prospect was published in autumn 2021 by Edward Elgar Publishing.

The technology is not just there to service what we are already doing, it’s there to change the way we do things.Determined-by-Architecture (DBA) model that proposes any blockchain iteration can be characterized by three axes and the internal (technical) and external (social/behavioural) attributes. Regulation based on an incrementalist financial narrative is not keeping up with the pace of technological possibilities.

LIGHTING PIONEER SEES A BRIGHT FUTURE AHEAD

Organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) are used to create digital displays in everything from televisions and computer monitors to mobile phones. One of the pioneers in this field is … Professor Che Chi-ming… who in 1998 was the first in the world to report that emitters made from phosphorescent metal complexes can greatly increase the efficiency of OLEDs.

The field since then has developed around emitters made from expensive metals, in particular iridium (which is now widely used) and platinum, which is starting to be adopted. But Professor Che’s vision has continued to widen and he is now on the cusp of a breakthrough using a much cheaper and more abundant metal – copper – that could make OLEDs more accessible and less subject to geopolitics.

Within the last year, he has developed a copper emitter that can perform with high efficiency and luminosity, and has the best device lifetime in the literature for such a device.

“The lifetime is still not as good as platinum and iridium, but the principle has been established. There is no reason why we cannot accomplish this,” he said. “I think within two or three years, copper could have a chance to share the market with iridium.”

This assessment, and his progress on copper emitters, is grounded in world-leading expertise that has brought top international firms knocking on Professor Che’s door.

Following his 1998 discovery – which unfortunately was not patented at the time but published in Nature – the display technology industry became dominated by iridium emitters developed by the American company UDC. However, this has been far from ideal for manufacturers because iridium is a rare metal and China has no iridium sources of its own.

“The iridium emitter is fairly expensive and there is a sustainability issue because iridium has low abundance on Earth. This also means China could be vulnerable in future if the supply becomes limited,” he said.

Given those factors, and his own predilection for experimenting with metal complexes, Professor Che began to explore the potential of other metals in OLEDs.

He developed a platinum emitter which he patented and licensed to Samsung, Merck and Aglaia Tech, a mainland Chinese company. Platinum has the advantage of being more abundant than iridium.

With Samsung, he subsequently entered an exclusive arrangement to work on platinum emitters based on his research, although the company later went its own way and has announced a patented platinum emitter that it says has better efficiency, lifetime and other qualities than iridium emitters.

“I have mixed feelings about this. They treated me well and we had a good collaboration. They are very good at device engineering, which is not my area of expertise. However, now they are strong competition for me – they follow my approach and they have more resources than me,” he said.

But Professor Che is still in the game. He has been honing his chances of advancing platinum emitters further by solidifying a partnership with Aglaia and Tsinghua University. Aglaia offers industry input while Tsinghua is strong in engineering. And there is room for innovation because the current platinum emitters mostly work in green.

Professor Che recently has developed red and infrared platinum emitters and is making strong progress on a blue emitter, the most difficult of all to achieve. His emitters have strong luminescence and efficiency and a good product lifetime. They are undergoing further fine-tuning to push their performance to be better than iridium in order to make them attractive to industry.

“In any case, the message now is that platinum OLEDs are no longer proof of concept. They have approached the level that they can be used in industry for green emitters,” he said.

In any case, the message now is that platinum OLEDs are no longer proof of concept. They have approached the level that they can be used in industry for green emitters.

Despite that promise, however, platinum is still an expensive raw material. Professor Che has also been trying for years to develop more abundant materials as metal emitters and with copper, he is on the cusp of a major breakthrough.

His copper emitters can produce blue, green and red, have high efficiency, strong luminescence and device stability. Their lifetime is still not as good as that of iridium and platinum devices, but he believes this hurdle can be overcome.

“A year ago, no one would say that that copper could be the future. Now I can say that it is possible. The principle has been established – there is no reason why we cannot accomplish this,” he said. “I think within two or three years, copper could have a chance to share the market with iridium.”

His collaborations will be central to this goal. Professor Che is working on setting up a company to develop his patents and hopes to concentrate this effort in the Greater Bay Area, in collaboration with his partners.

“I can invent new things but to make them a reality in industry is not just one man’s work. This will be important to the whole display technology industry of China,” he said.

It will also help to achieve a personal goal. Professor Che says working on metal emitters is a hobby that he does out of personal interest, alongside his major work investigating metal complexes in anti-cancer drugs. In both cases, he aspires to show the value of blue-sky research.

“I want people to know that basic science can make important contributions. The reason why big companies want to work with me is because I’m pretty good in basic science,” he said.

FROM DOING OUR DIRTY WORK TO MERGING WITH OUR CELLS: THE TRAJECTORY OF ROBOTICS

Professor Xi Ning, Chair Professor of Robotics and Automation and Director of the Emerging Technologies Institute, is a leading scientist in robotics who, over a quarter of a century, has advanced the field with new theoretical underpinnings and new applications, ranging from cleaning up nuclear waste to breast cancer diagnosis. He is now working on robots to guide stem cell growth, do drug discovery, help people with mobility issues and, in a new line of study, to merge robots with humans, for example, to provide new body parts.

“In the beginning, robots were developed to replace people in the three ‘d’ jobs – dirty, dangerous and dull. The robots sat behind cages or fences,” he said. “Then they became collaborative robots that can sit next to us and even be worn by us. Now, we want to develop what I call biosyncretic robots that merge the robot with the human body. We have projects happening in all these areas.”

The starting point for these advances was his work more than two decades ago as a graduate student at Washington University, where he helped to develop a theory that upended the traditional approach to robotics and opened the possibility of making robots more “intelligent” and human-like in their processing.

Previously, a robot’s actions were based around time –for example, it would be engineered to assemble an item or move across a room within a set number of seconds or minutes. But this meant the robot could not deal with obstacles. If debris blocked its way, errors would accumulate and the robot’s progress would be halted.

The innovation of Professor Xi and his collaborators was to replace time with events as the reference point, which is closer to how humans operate. When we go to pick up a phone, we are guided not by how long it takes our hand to reach the phone, but by completing the action. “That actually changed the concept of robotic control,” he said.

This insight has enabled robotics to flourish in the Internet age. Robots can be controlled from remote locations even though Internet transmission means that not all information reaches a destination at precisely the same time.

Professor Xi has used this insight as a jumping-off point to develop a number of robotics applications.

The nuclear waste robot, which he developed while he was a professor at Michigan State University in the 2000s, is in use at Oak Ridge National Laboratories in the US. It has been able to deal with unexpected obstacles such as chairs and tables that were thrown into the waste site over the past 50 years.

He also developed a robot that can help with remote diagnosis of breast cancer, by palpitating a woman’s breast and sending the readings to an experienced doctor for interpretation. This is still in development but could be especially helpful for women living in remote areas or requiring a check-up during a pandemic.

Currently, Professor Xi is working with Professor Pengtao Liu in the School of Biomedical Sciences, who has developed expanded potential stem cells (EPSCs), which are early-stage stem cells that have not yet differentiated. Tiny robots are being applied to try to get them to differentiate along certain paths, such as into bone, muscle or blood. “Because the EPSCs are so small, we need a special tool to touch them and sense then, to find out what the future of EPSCs will be,” Professor Xi said. Similarly, he is using robots to deliver and test drugs at the cellular scale.

He is also leading a Theme-based Research Scheme project to develop wearable robots for the elderly that will go beyond being simply assistive devices. Mobility is a major impediment for people as they age and for their families who must support them. But Professor Xi and his collaborators want to do more than help people move. They also want to help them to maintain their health for as long as possible.

“If the robot just helps you to move, you won’t use that muscle anymore and it will degenerate faster. We want a robot to assist the muscle, not replace it. It’s a combination of assistance and rehabilitation,” he said.

His multidisciplinary team includes researchers from sociology, medicine, mechanical engineering, computer science and biomedical engineering. They have adopted what they call a UC3 approach – for “user-centric cocreation” – that starts by asking subjects which areas of their daily lives are being hindered by mobility issues, then assessing related functions such as walking or lifting their arm, then going down to the physiological level to identify the affected muscles or other body parts. An individualised robot is then developed, tested by the subjects, sent back for improvement, tested again, and so forth, in an iterative

Disinfection robot working in an office.process. So far about 100 elderly have volunteered and Professor Xi said they are enthusiastic about the potential of the robots. The five-year project, which is in its second year, will develop five types of robots for the knee, ankle, hand, arm/shoulder and hip.

His other new area of research, biosyncretic robots, promises to be just as impactful because of the potential to fulfil a science fiction vision of humans having robotic parts, such as organs, nerves or limbs. This is not as farfetched as it sounds when one considers that the heart pacemaker is a machine that works inside the body.

“We want to merge the robot with our body at the cellular and molecular level, like growing the robot into your body,” he said. “This is different from biomimetic robots where you learn from biology to make a robot. Our research is still at the beginning, but we have made a small robot that is powered by muscle contractions.”

Professor Xi has also been applying his robotics expertise to help with wider societal concerns, including disinfection during the pandemic, 3D printing in the construction industry, and applications in education.

He received a Collaborative Research Fund grant that is applying robotics to help students carry out remote laboratory experiments with the University of Glasgow. This makes laboratory experimentation – which is fundamental in STEM subjects – accessible even when students cannot go to campus or even when the lab is in another country. His hope is that this application can be expanded so that students living in rural and underprivileged areas can have access to world-class experimentation tools.

“Once we have this technology, it provides opportunities for students and they don’t need to be bound by time or place. It could significantly increase access to education and make it a more level playing field,” he said.

We want to merge the robot with our body at the cellular and molecular level, like growing the robot into your body.Top: Developing assistive robot for elderly. Middle: Wearable robot assisting mobility.

VIRAL WEAPONS FOUND IN SEWAGE COULD HELP TARGET POLLUTION

Bacteria, like humans, animals and plants, can be infected by viruses, called phages, also known as prokaryotic viruses. For years, the medical field has been exploring how to weaponise phages to treat harmful bacterial infections in people. Now, a study by Professor Tong Zhang, Chair Professor of Water and Environmental Engineering in the Department of Civil Engineering, published recently in Nature Communications, is bringing that approach to the environment.

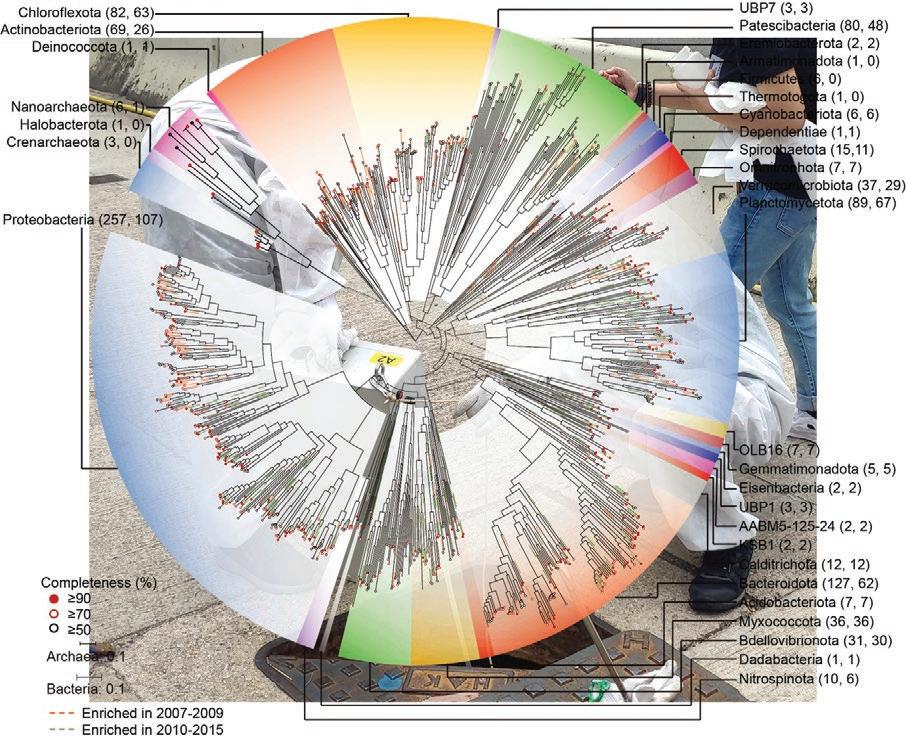

Professor Zhang and his team did a systematic study of activated sewage sludge from six wastewater treatment plants in Hong Kong to compile a catalogue of about 50,000 phages and investigate their connections with bacteria and other microorganisms in the wastewater –the first time this has been done in such an environment.

“This is a new field and we are just at the beginning, cataloguing and mapping these viruses and looking at very fundamental issues. There are still big challenges ahead, but the idea is that with this information, we could use different phages to control some of the microorganisms in the reactors of wastewater treatment plants to remove pollutants and help to protect the environment,” he said.

The inspiration for the study came from Professor Zhang’s ongoing work on the microbiome and his deep appreciation of the importance of “One Health” – the concept that the health of humans, animals and the environment are closely intertwined, which was formally endorsed by the World Health Organisation (WHO), Food and Agriculture Organisation and World Organisation for Animal Health in 2010.

Understanding the microbial community is essential to developing better reactors in wastewater treatment plants, which are essentially massive biotechnological projects where aeration and microorganisms are applied to break down pollutants in sewage before the wastewater is discharged into the environment.

“If we cannot understand the microbial community that will work best for us in the reactor, then we may not be able to design reactors with better performance. It would just be a black box,” he said.

While the advent of high-throughput DNA sequencing technology since 2007 has greatly enriched information about bacteria in reactors – there are now twice as many species known as there were 10 years ago – the challenge

has remained over how to target harmful types of bacteria without damaging the good types.

Phages provide an answer because of their ability to invade bacteria specifically. Phages are about 1,000 times smaller than bacteria and infect bacteria by hijacking their genetic system to reproduce themselves, before breaking through the cell wall to infect more bacteria. While that may sound nasty, the end result could be that, with the right tweaking, they could be used to attack only the specific harmful bacteria.

Professor Zhang’s study identified 50,000-odd types of phages from six wastewater treatment plants in Hong Kong using a systematic metagenomic pipeline to extract DNA from concentrated samples. This diversity greatly expands the knowledge base of phages in activated sludge and provides a platform for developing phage treatments.

One treatment target highlighted in the study was foaming bacteria in Hong Kong wastewater treatment plants during the transition from cool to warm weather. Professor Zhang’s study identified more than four phage types that infect bacteria related to foaming, opening a pathway towards a possible solution to this problem.

His next step will be to extract and grow phages. “This will be a more difficult challenge. We’re still at an early stage so we will take this step by step,” he said.

Professor Zhang has already pioneered wastewater surveillance methods to study antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in the environment, a field he has been studying for more than 15 years. A DNA sequencing technology he developed profiles resistant genes in environmental samples, and it has been used by scholars around the world, and is recommended on China’s Centre for Disease Control website. Researchers and others can either upload their data to his screening tool or download the tool itself to analyse environmental samples.

He also recently worked with HKU’s School of Public Health to develop a method of identifying and quantifying the presence of the COVID-19 virus and its variants in sewage. The method was subsequently adopted by the Hong Kong government for identifying outbreaks and issuing compulsory COVID-19 testing orders. “The sewage test is part of a larger field called wastewater-based epidemiology, shortened as WBE. WBE is not new, it began 20 years ago, but after COVID-19 it has become more and more popular, not only in the research field but also more accepted by the medical field,” he said.

Circling back to his study on AMR, Professor Zhang noted that there is growing urgency to get AMR under control because bacteria infected with AMR genes can transfer their resistance to other bacterial species, including human pathogens, and wastewater treatment plants provide ideal reservoirs for this to happen. Earlier, he showed that Hong Kong wastewater has a higher level of AMR genes than that of some other cities and countries.

“AMR, COVID-19 and prokaryotic viruses all come under the umbrella of the microbiome,” he said. “This is all One Health. If we cannot control the spread of pathogens in animals and the environment, then humans may eventually get infected by them. So these three elements are closely connected.”

Taking sample for COVID-19 virus sewage surveillance

Life tree of bacterial and archaeal genomes recovered from activated sludge of Sha Tin Sewage Treatment Work, Hong Kong, China.

Taking sample for COVID-19 virus sewage surveillance

Life tree of bacterial and archaeal genomes recovered from activated sludge of Sha Tin Sewage Treatment Work, Hong Kong, China.

This is all One Health. If we cannot control the spread of pathogens in animals and the environment, then humans may eventually get infected by them. So these three elements are closely connected.