Fighting It Again: Gettysburg 1988 Architects Race for the Clouds Where Baseball Bats Are Born Underground Railroad Bike Trail Her War Abigail Adams Recounts the Revolution’s Tumultuous Opening Days Toys, Maps, Patents NEW DEPARTMENTS INSIDE! Plus HISTORYNET.com Spring 2023 AMHP-230400-COVER-DIGITAL.indd 1 1/9/23 10:29 AM

Each one of our 1/30 scale metal figures is painstakingly researched for historical accuracy and detail. The originals are hand sculpted by our talented artists before being cast in metal and hand painted – making each figure a gem of handcrafted history.

Please visit wbritain.com to seeall these figures and more from many other historical eras.

matte finish Hand-Painted Pewter Figures 56/58 mm-1/30 Scale Call W.Britain and mention thisad for a FREE CATALOG Also recieve a MINI BACKDROP with your first purchase! WBMH SPRING23 ©2023 W.Britain Model Figures W.Britain, and are registered trademarks of the W.Britain Model Figures, Chillicothe, OH Follow us on Facebook: W-Britain-Toy-SoldierModel-Figure-Company Subscribe to us on YouTube: W.Britain Model Figures

Recreate history with our many figures, scenic accessories, and backdrops. Here we see Washington and his Bodyguard (soldiers, NCO, and drummer), along with Marquis de Lafayette and Alexander Hamilton.

Tel: U.S. 740-702-1803 • wbritain.com • Tel: U.K. (0)800 086 9123 See these and more W.Britain 1/30 scale historical metal figures at:

AMHP-230214-08 WBritian Model Figures.indd 1 12/30/2022 10:41:29 AM

10093

Mark Twain, American Author $45.00

AMHP-230214-03 Pursuit of History.indd 1 12/30/2022 10:18:43 AM

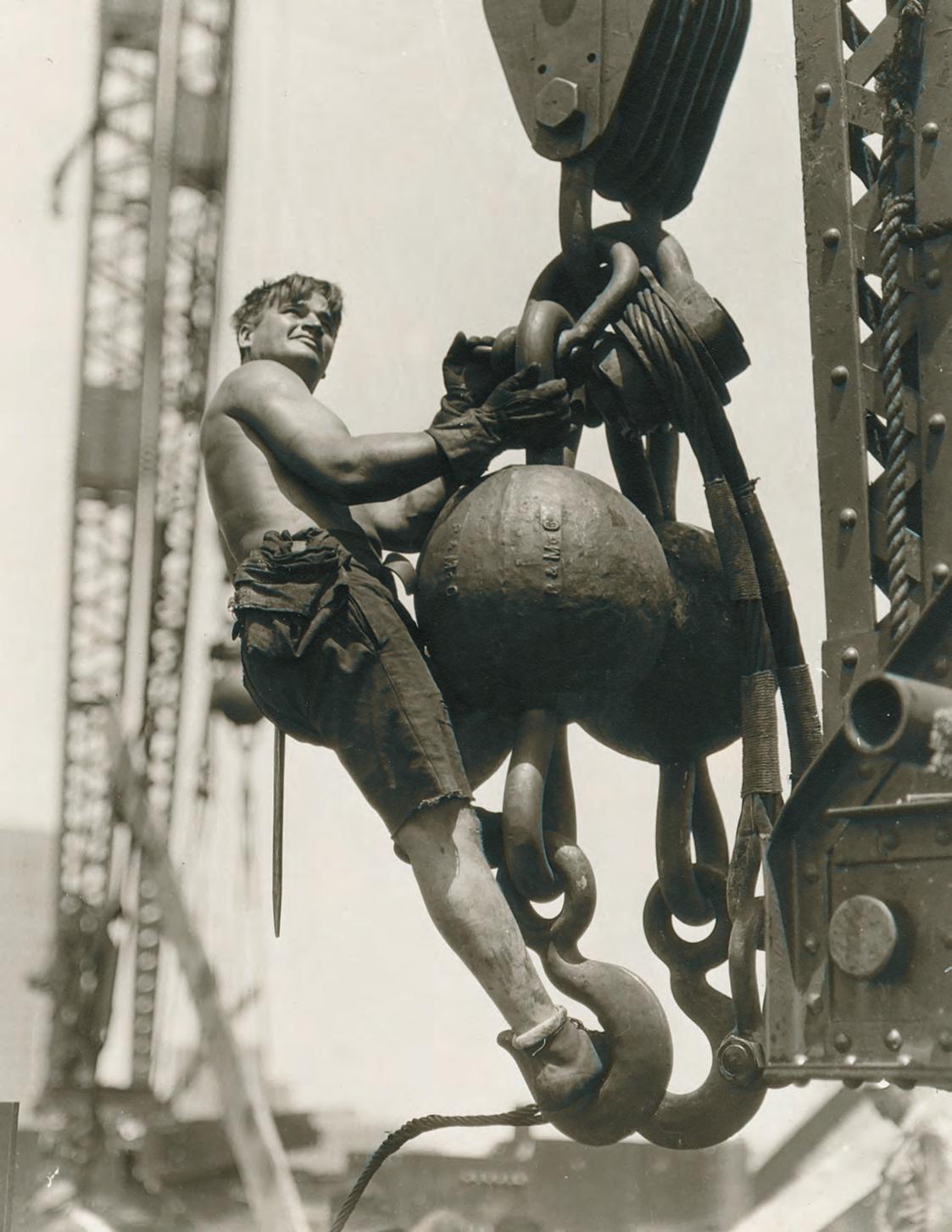

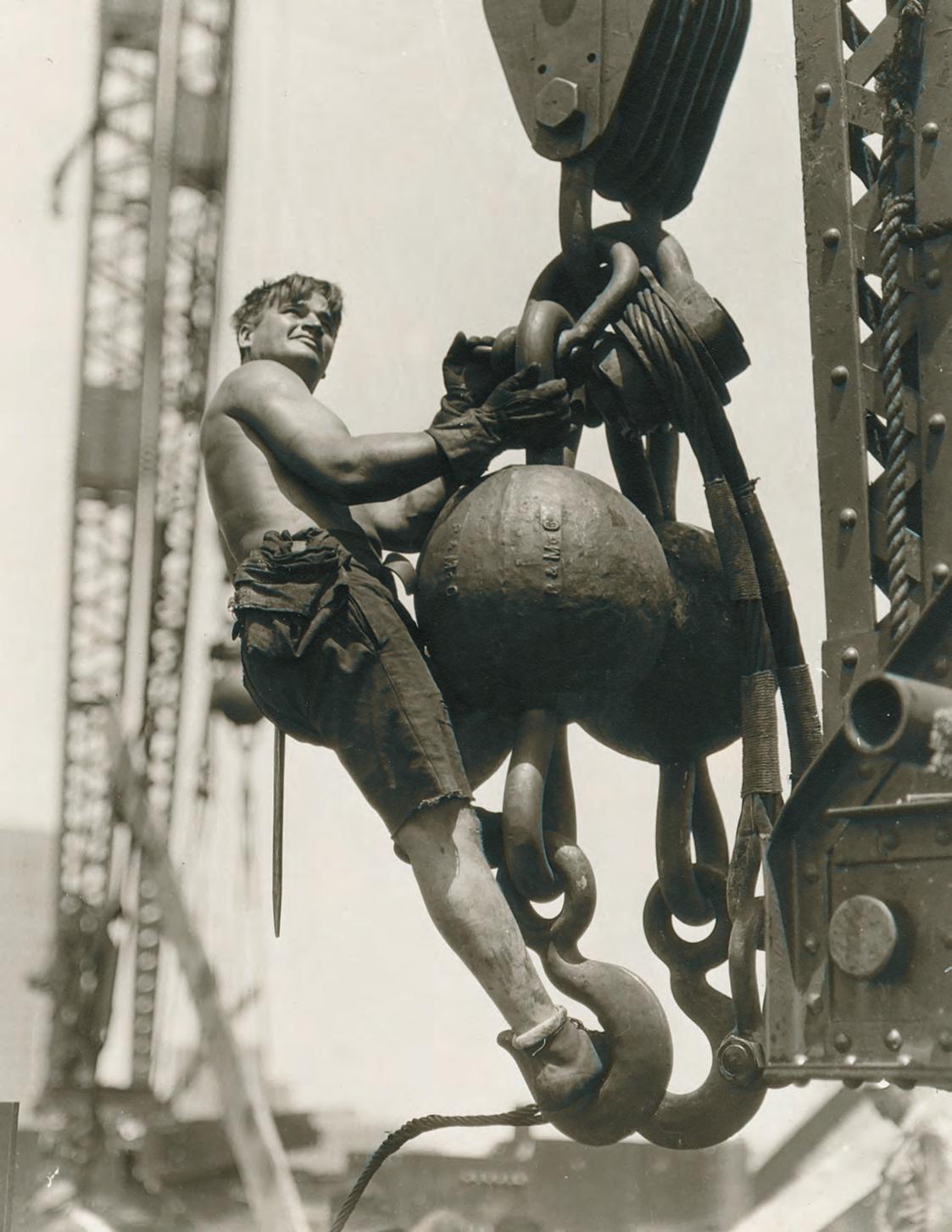

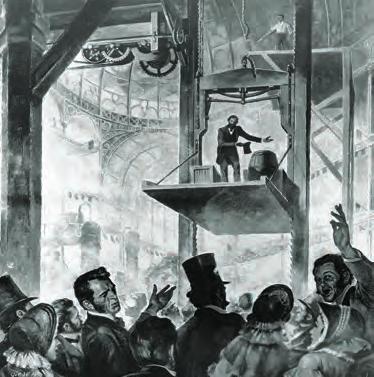

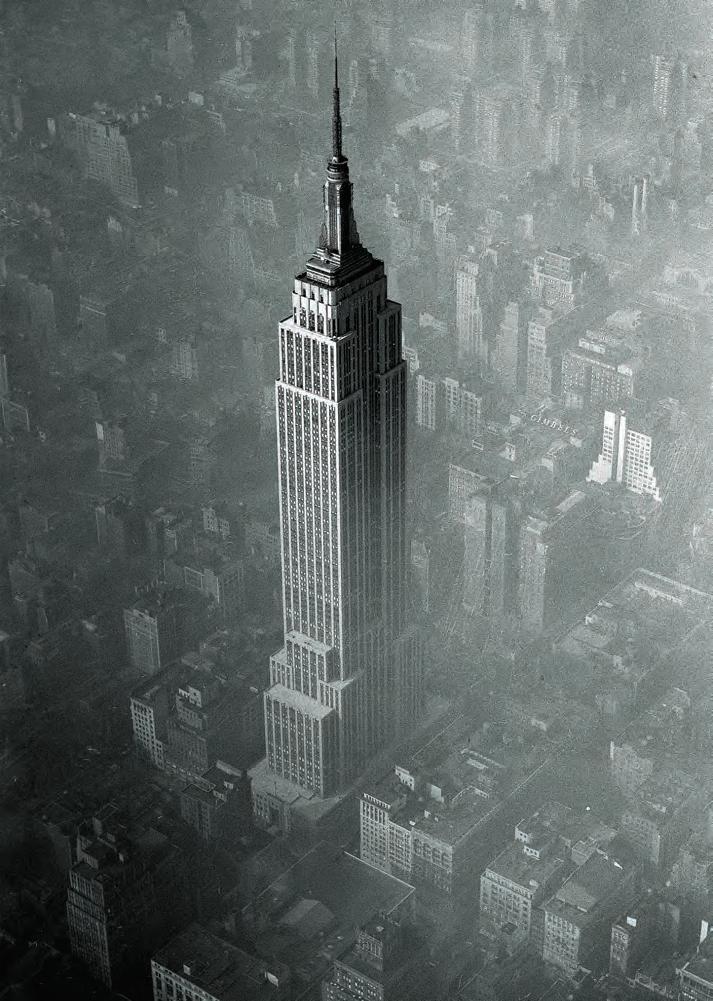

No need for a workout at the gym when your workday requires you to climb and hang high above the sidewalk.

36

AMHP-230400-CONTENTS.indd 2 1/9/23 8:22 AM

Spring

2023

Abigail Adams endured British occupation, a smallpox epidemic, and her husband’s indifference. By Jon Mael

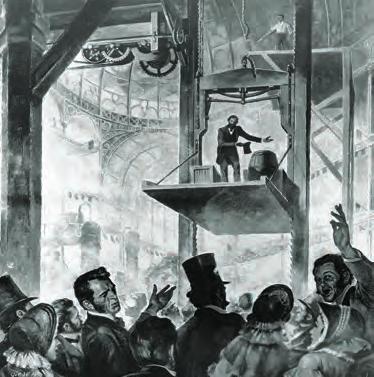

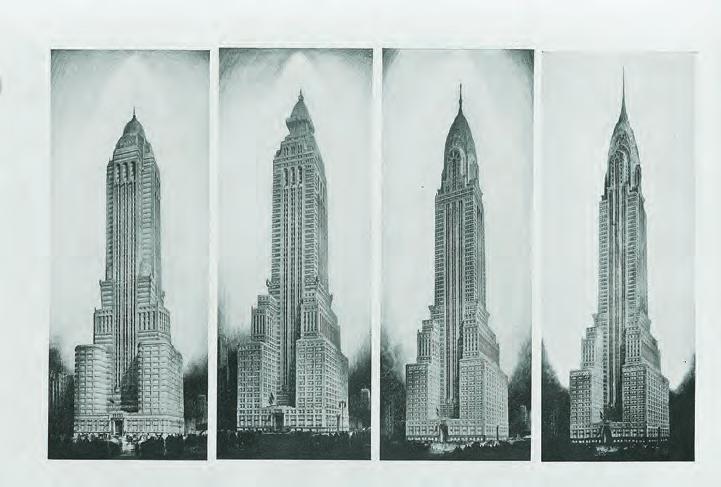

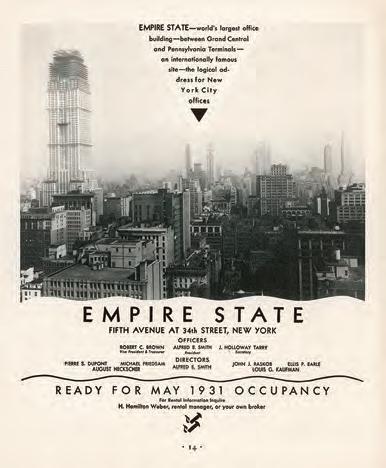

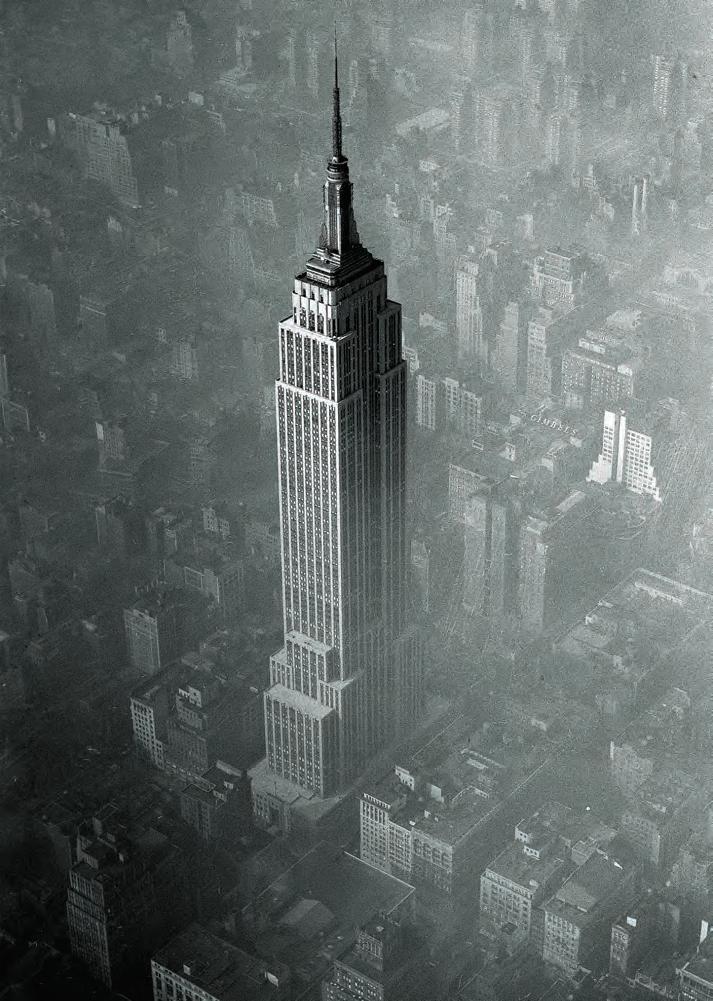

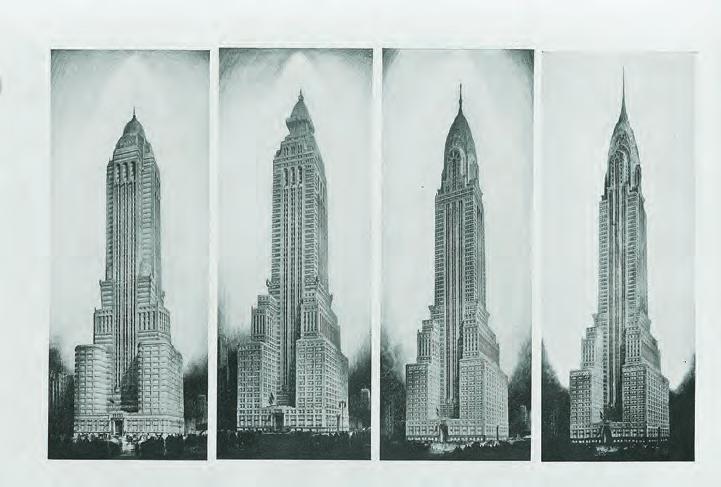

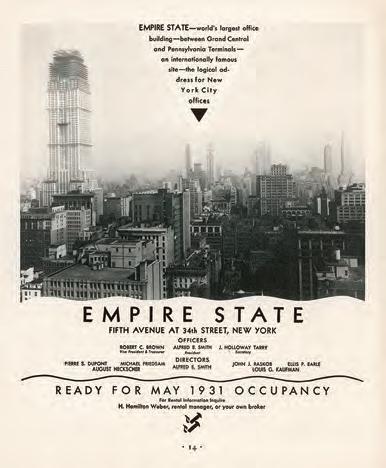

Steel skeletons and elevators allowed architects to build higher and higher. By Dennis Goodwin

Musketry crackled and cannons thundered at the 1988 Gettysburg reenactment. By John Banks

—see page 46

SPRING 2023 3 FEATURES 28 L ife During Wartime

Sky High

36

46 ‘A Real Powder Burner’

Stalking

54

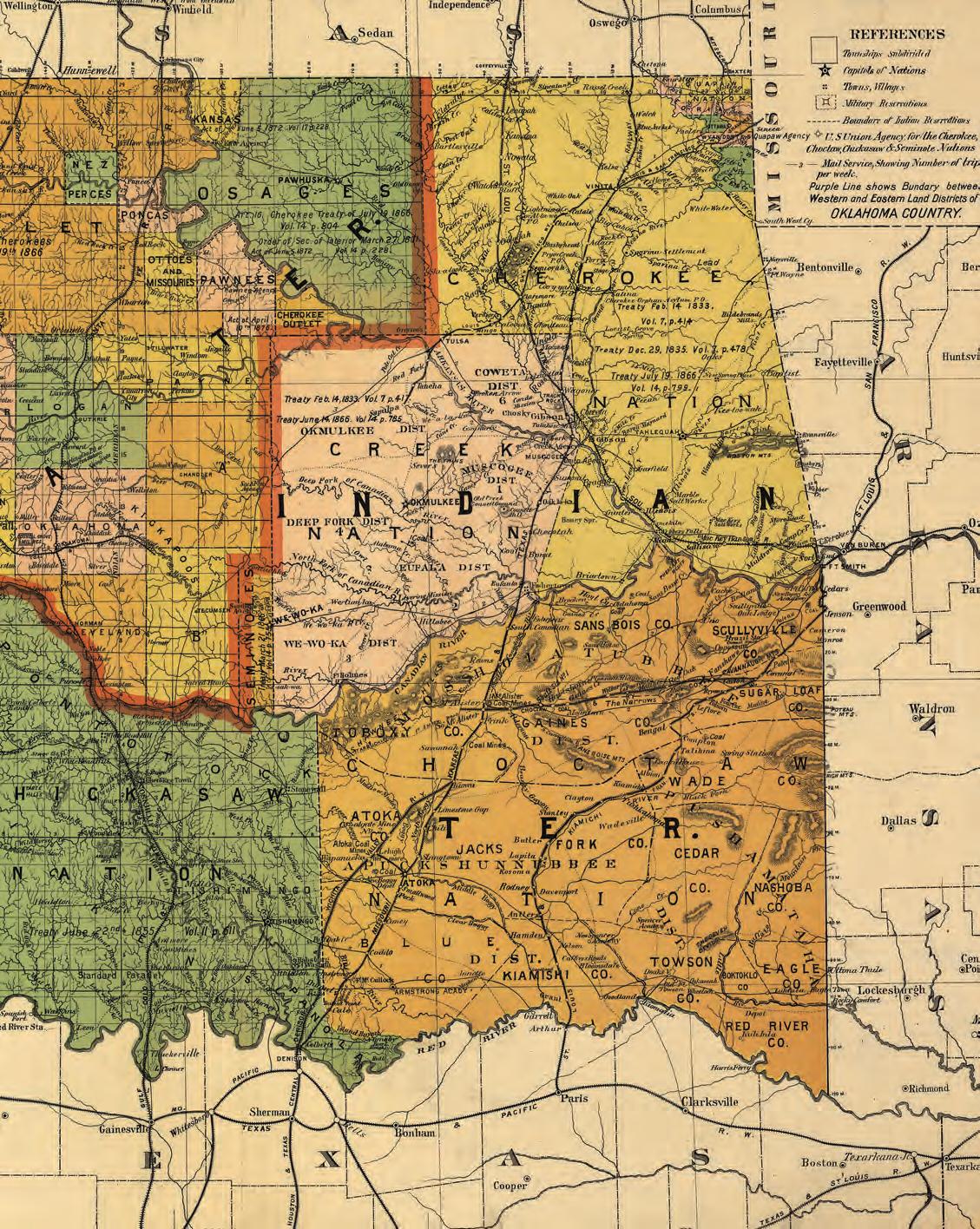

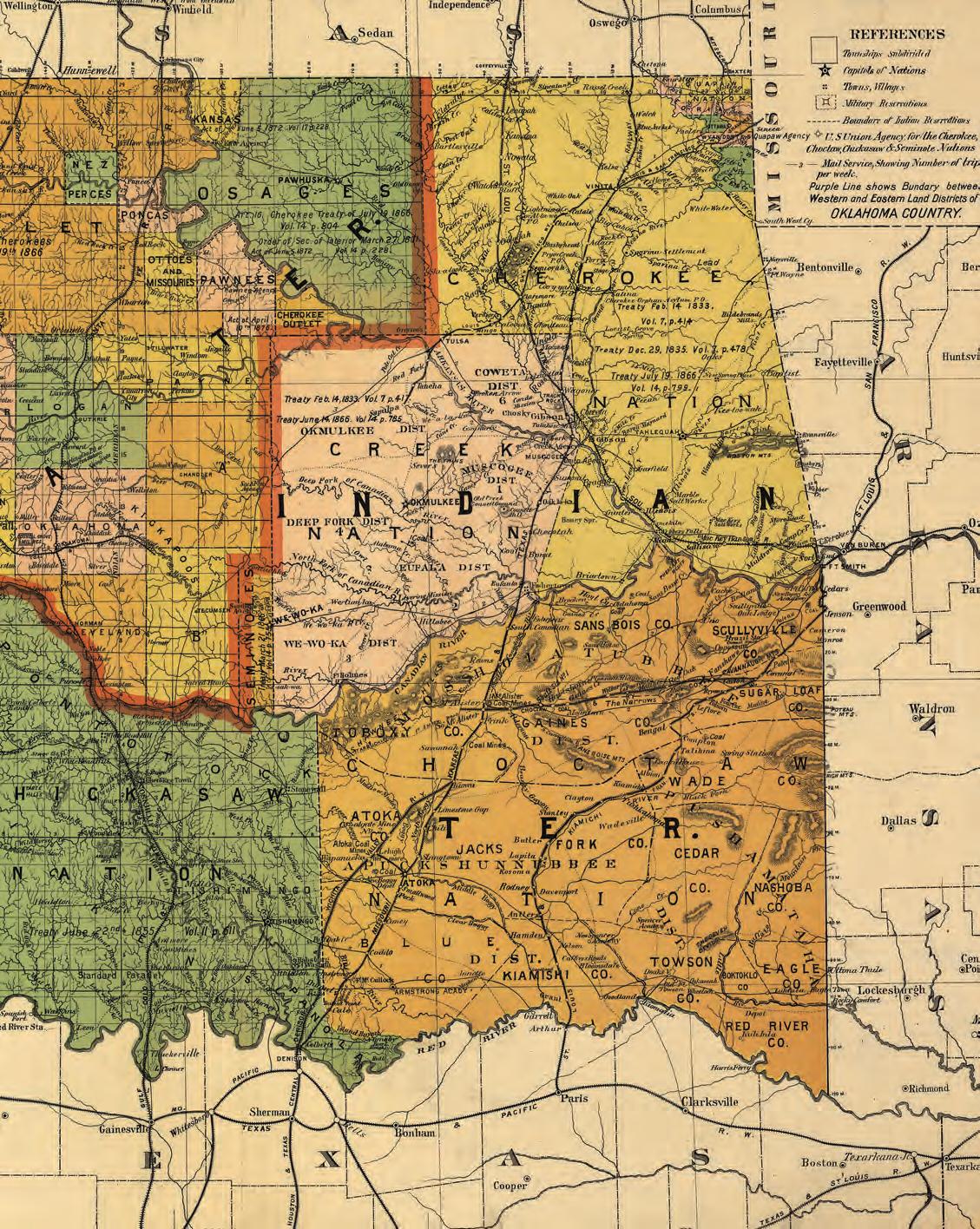

the Decisive Moment

24 54 28 DEPARTMENTS 6 Letters Talk to us! 8 Mosaic History in the headlines. 14 A merican Schemers Pray for money. 16 Innovations A close shave. 18 Déjà Vu Illness and the campaign trail. 22 Interview Biking a path to freedom. 24 A merican Place W here baseball bats are born. 27 Editorial Remodeling Project. 62 Terra Firma Indian Territory. 64 Reviews The life of Charlton Heston. 72 Toy Box Elephant on wheels! ON THE COVER: From her

Mass., Abigail

could hear the Battle of

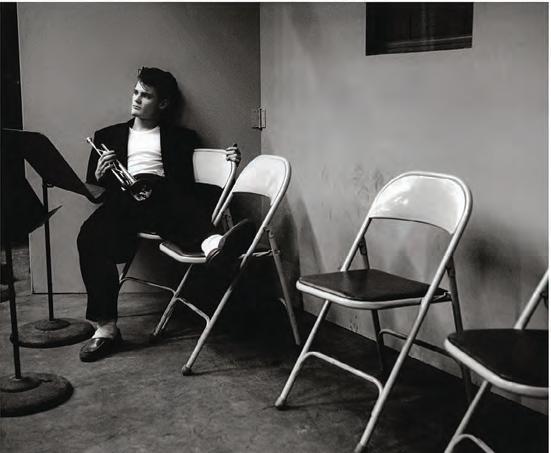

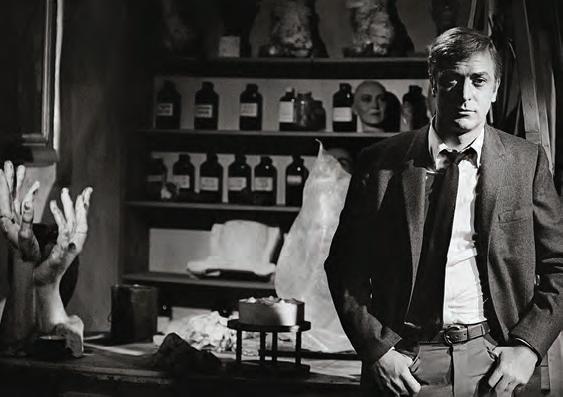

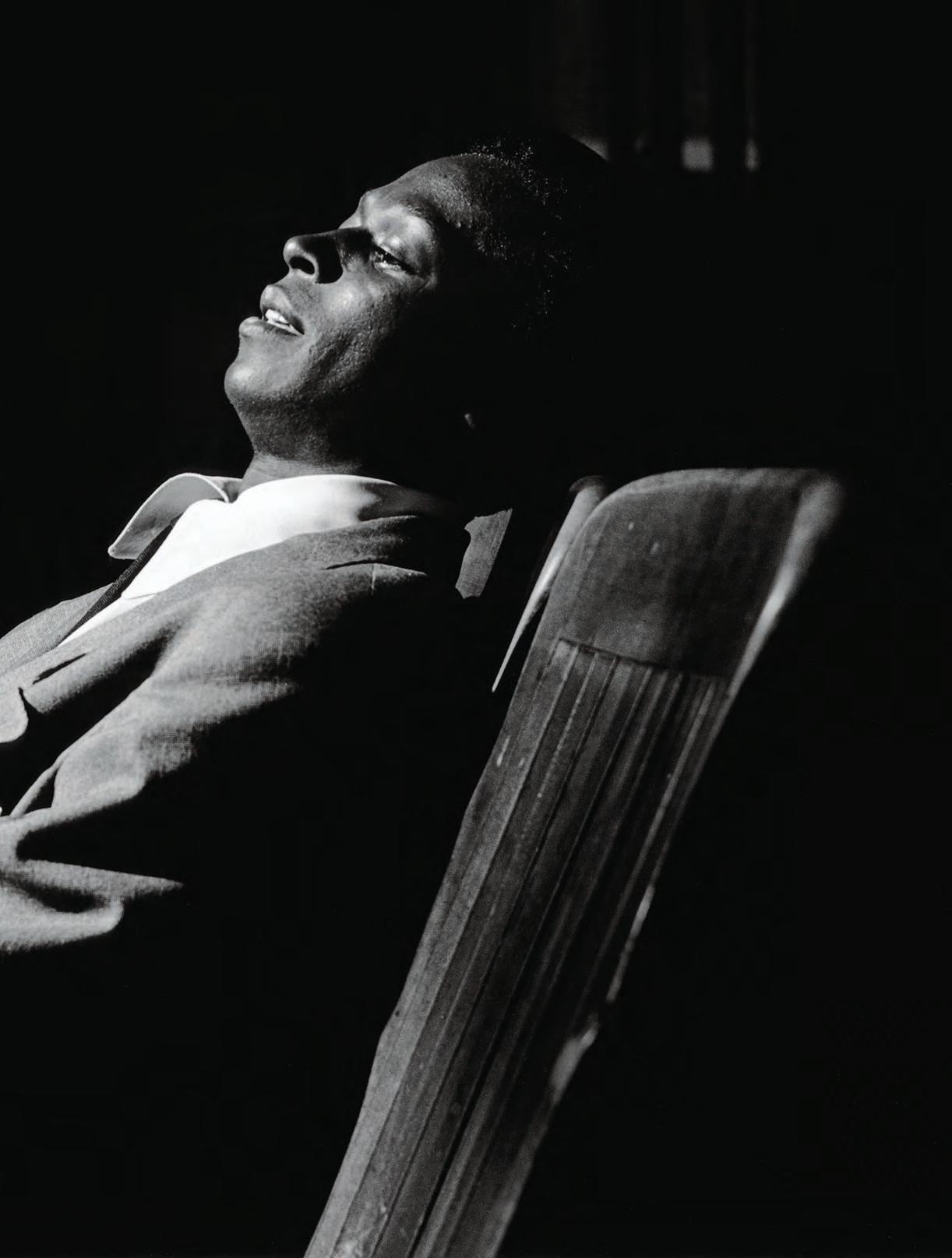

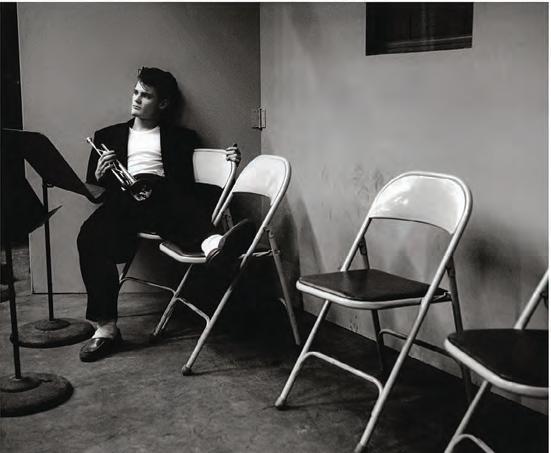

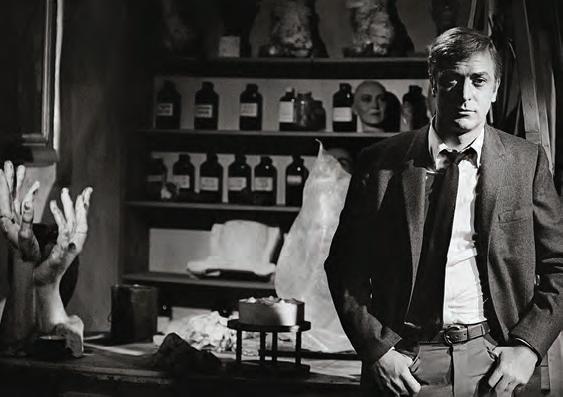

Bob Willoughby’s lush photography captured Hollywood stars on set. By Michael Dolan Hill. CLOCKWISE FROM LEFT: NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY; NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART; COURTESY OF THE LOUISVILLE SLUGGER MUSEUM & FACTORY; © THE BOB WILLOUGHBY PHOTO ARCHIVE; COVER: BOSTON MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS; ALBERT KNAPP/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO/PHOTO ILLUSTRATION: BRIAN WALKER

home near Boston,

Adams

Bunker

the years.

New New New AMHP-230400-CONTENTS.indd 3 1/9/23 8:22 AM

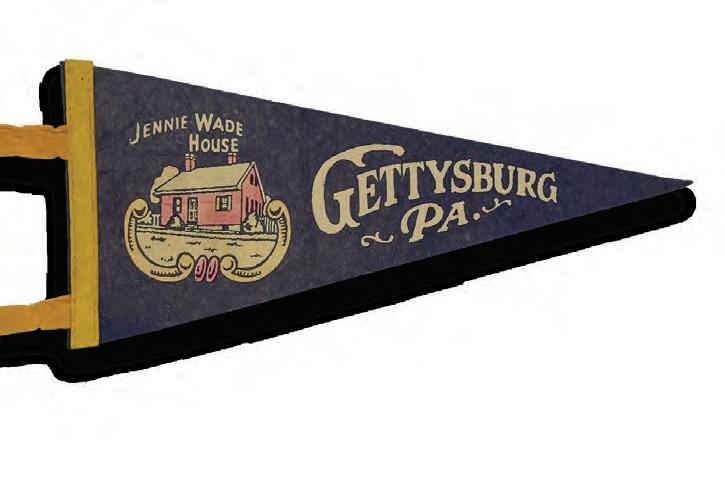

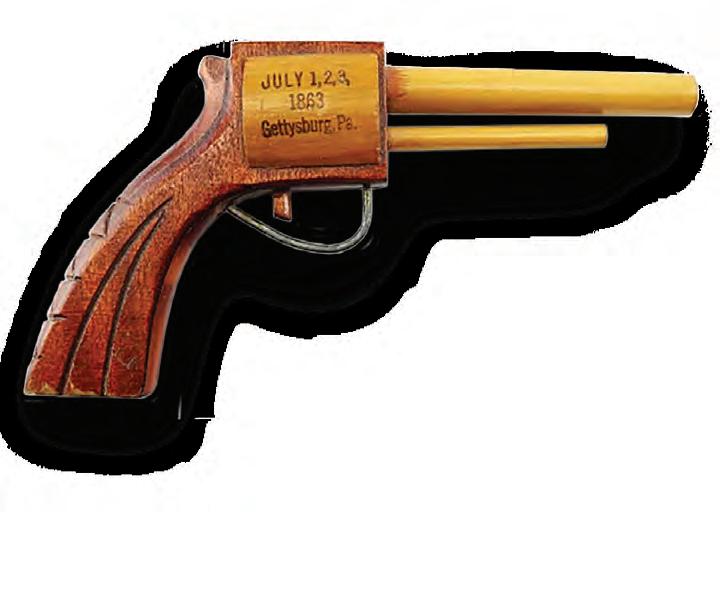

From pot-metal shoes, to ribbon badges, to whiskey shot glasses, Gettysburg souvenirs through

By Tom Straka and Bob Wynn historynet.com/piedmont-ghost-town

Weapons

The

DANA B. SHOAF EDITOR IN CHIEF CHRIS K. HOWLAND SENIOR EDITOR

BRIAN WALKER GROUP DESIGN DIRECTOR MELISSA A. WINN DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY JON C. BOCK ART DIRECTOR

CLAIRE BARRETT NEWS AND SOCIAL EDITOR

CORPORATE

KELLY FACER SVP REVENUE OPERATIONS

MATT GROSS VP DIGITAL INITIATIVES

ROB WILKINS DIRECTOR OF PARTNERSHIP MARKETING JAMIE ELLIOTT SENIOR DIRECTOR, PRODUCTION

ADVERTISING

MORTON GREENBERG SVP Advertising Sales mgreenberg@mco.com

TERRY JENKINS Regional Sales Manager tjenkins@historynet.com

DIRECT RESPONSE ADVERTISING

NANCY FORMAN / MEDIA PEOPLE nforman@mediapeople.com

SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION: SHOP.HISTORYNET.COM or 800-435-0715

American History (ISSN 1076-8866) is published quarterly by HistoryNet, LLC, 901 North Glebe Road, Fifth Floor, Arlington, VA 22203 Periodical postage paid at Vienna, VA and additional mailing offices.

POSTMASTER, send address changes to American History, P.O. Box 900, Lincolnshire, IL 60069-0900

List Rental Inquiries: Belkys Reyes, Lake Group Media, Inc. 914-925-2406; belkys.reyes@lakegroupmedia.com Canada Publications Mail Agreement No. 41342519, Canadian GST No. 821371408RT0001

© 2023 HistoryNet, LLC

The contents of this magazine may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the written consent of HistoryNet LLC.

PROUDLY MADE IN THE USA

PHOTO BY DOUG PAGE

MICHAEL A. REINSTEIN CHAIRMAN & PUBLISHER

SPRING 2023 VOL. 58, NO. 1

Sign up for our FREE weekly e-newsletter at historynet.com/newsletters HISTORYNET VISIT HISTORYNET.COM PLUS! Today in History What happened today, yesterday or any day you care to search. Daily Quiz Test your historical acumen every day! What If? Consider the fallout of historical events had they gone the ‘other’ way.

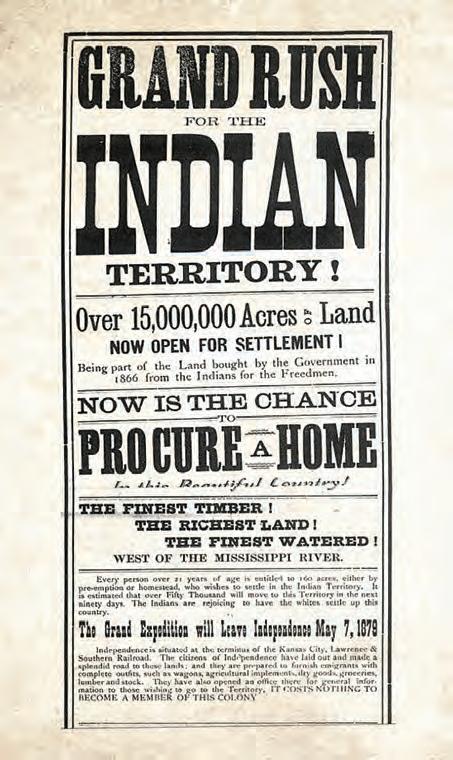

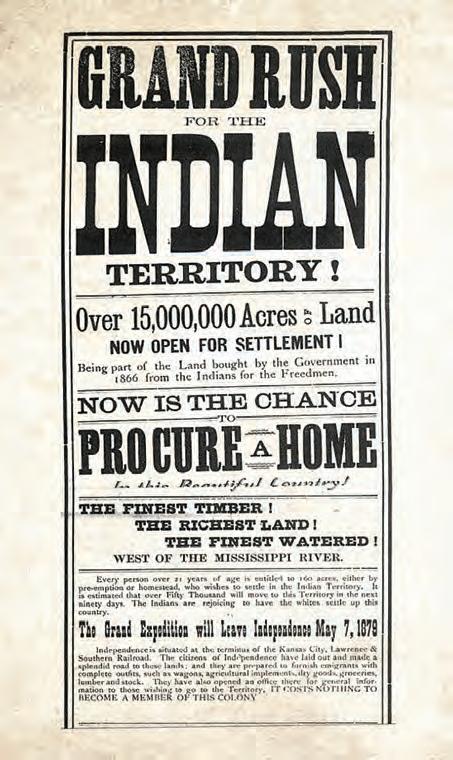

& Gear

gadgetry of war—new and old, effective and not so effective. TRENDING NOW

In 1869 Mormon pioneer Moses Byrne built six large beehive kilns along the western side of the Union Pacific Railroad. Why?

Ghost Town: Piedmont, Wyo. AMHP-230400-MASTONLINE.indd 4 1/19/23 4:07 PM

Upper Class Just Got Lower Priced

UntilStauer came along, you needed an inheritance to buy a timepiece with class and re nement. Not any more. e Stauer Magni cat II embodies the impeccable quality and engineering once found only in the watch collections of the idle rich. Today, it can be on your wrist.

e Magni cat II has the kind of thoughtful design that harkens back to those rare, 150-year-old moon phases that once could only be found under glass in a collector’s trophy room.

Powered by 27 jewels, the Magni cat II is wound by the movement of your body. An exhibition back reveals the genius of the engineering and lets you witness the automatic rotor that enables you to wind the watch with a simple ick of your wrist. It took three years of development and $26 million in advanced Swiss-built watchmaking machinery to create the Magnificat II.When we took the watch to renowned watchmaker and watch historian George Thomas, he disassembled it and studied the escapement, balance wheel and the rotor. He remarked on the detailed guilloche face, gilt winding crown, and the crocodile-embossed leather band. He was intrigued by the three interior dials for day, date, and 24-hour moon phases. He estimated that this fine timepiece would cost over $2,500. We all smiled and told him that the Stauer price was less than $100. A truly magnificent watch at a truly magnificent price! Try the Magnificat II for 30 days and if you are not receiving compliments, please return the watch for a full refund of the purchase price. The precision-built movement carries a 2 year warranty against defect. If you trust your own good taste, the Magnificat II is built for you.

Stauer Magnificat II Timepiece $399*

Offer Code Price $99 + S&P SAVE $300!

You must use the offer code to get our special price. 1-800-333-2045

Your Offer Code: MAG653-08

Rating of A+

•Luxurious

•

•

•Water-resistant

gold-finished case with exposition back

27-jeweled automatic movement

Croc-embossed band fits wrists 6¾"–8½"

to

ATM

3

155,

653-08

14101 Southcross Drive W., Ste

Dept. MAG

Burnsville, Minnesota 55337 www.stauer.com Stauer ®

Special price only for customers using the offer code versus the price on Stauer.com without

Afford the Extraordinary . ® The Stauer Magnificat II is powered by your own movement

†

your offer code. Stauer…

AMHP-230214-07 Stauer Magnificat Watch.indd 1 12/30/2022 10:35:50 AM

Finally, luxury built for value— not for false status

Write Us!

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU! For future issues, we want to fill this section with our devoted readers’ thoughts and opinions, so please write us at americanhistory@historynet.com. In the meantime, here is the famous “Remember the Ladies” letter Abigail Adams wrote to her husband on March 31, 1776, and enjoy the story about her on P. 28.

Braintree March 31 1776

Letters

I wish you would ever write me a Letter half as long as I write you; and tell me if you may where your Fleet are gone? What sort of Defence Virginia can make against our common Enemy? Whether it is so situated as to make an able Defence? Are not the Gentery Lords and the common people vassals, are they not like the uncivilized Natives Brittain represents us to be? I hope their Riffel Men who have shewen themselves very savage and even Blood thirsty; are not a specimen of the Generality of the people.

I am willing to allow the Colony great merrit for having produced a Washington but they have been shamefully duped by a Dunmore.

I have sometimes been ready to think that the passion for Liberty cannot be Eaquelly Strong in the Breasts of those who have been accustomed to deprive their fellow Creatures of theirs. Of this I am certain that it is not founded upon that generous and christian principal of doing to others as we would that others should do unto us.

Do not you want to see Boston; I am fearfull of the small pox, or I should have been in before this time. I got Mr. Crane to go to our House and see what state it was in. I find it has been occupied by one of the Doctors of a Regiment, very dirty, but no other damage has been done to it. The few things which were left in it are all gone. Cranch1 has the key which he never deliverd up. I have wrote to him for it and am determined to get it cleand as soon as possible and shut it up. I look upon it a new acquisition of property, a property which one month ago I did not value at a single Shilling, and could with pleasure have seen it in flames.

The Town in General is left in a better state than we expected, more oweing to a percipitate flight than any Regard to the inhabitants, tho some individuals discoverd a sense of honour and justice and have left the rent of the Houses in which they were, for the owners and the

furniture unhurt, or if damaged sufficent to make it good.

Others have committed abominable Ravages. The Mansion House of your President2 is safe and the furniture unhurt whilst both the House and Furniture of the Solisiter General3 have fallen a prey to their own merciless party. Surely the very Fiends feel a Reverential awe for Virtue and patriotism, whilst they Detest the paricide and traitor.

I feel very differently at the approach of spring to what I did a month ago. We knew not then whether we could plant or sow with safety, whether when we had toild we could reap the fruits of our own industery, whether we could rest in our own Cottages, or whether we should not be driven from the sea coasts to seek shelter in the wilderness, but now we feel as if we might sit under our own vine and eat the good of the land.

I feel a gaieti de Coar [sic] to which before I was a stranger. I think the Sun looks brighter, the Birds sing more melodiously, and Nature puts on a more chearfull countanance. We feel a temporary peace, and the poor fugitives are returning to their deserted habitations

Tho we felicitate ourselves, we sympathize with those who are trembling least the Lot of Boston should be theirs. But they cannot be in similar circumstances unless pusilanimity and cowardise should take possession of them. They have time and warning given them to see the Evil and shun it.—I long to hear that you have declared an independancy—and by the way in the new Code of Laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make I desire you would Remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favourable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands. Remember all Men would be tyrants if they could. If perticuliar care and attention is not paid to the Laidies we are determined to foment a Rebelion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have no voice, or Representation.

That your Sex are Naturally Tyrannical is a Truth so thoroughly established as to admit of no dispute, but such of you as wish to be happy willingly give up the harsh title of Master for the more tender and endearing one of Friend. Why then, not put it out of the power of the vicious and the Lawless to use us with cruelty and indignity with impunity. Men of Sense in all Ages abhor those customs which treat us only as the vassals of your Sex. Regard us then as Beings placed by providence under your protection and in immitation of the Supreem Being make use of that power only for our happiness. H

American History readers wanting to pillory, praise, or query the publication: write to us at americanhistory@historynet.com

COURTESY OF THE MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL SOCIETY

AMERICAN HISTORY 6 AMHP-230400-LETTERS.indd 6 1/9/23 5:57 PM

nation Pl Town of PLYMOUTH Plymouth County Convention & Visitors Bureau visitma.com ti nat ion Plymouth SeePlymouth.com Did You Know? Pilgrim Hall Museum is The Oldest Continuously Operating Public Museum in America Plym out h See Plymouth and See For Yourself! History.net v2 copy.indd 1 12/20/22 11:55 AM AMHP-230214-02 See Plymouth CVB.indd 1 12/30/2022 10:25:08 AM

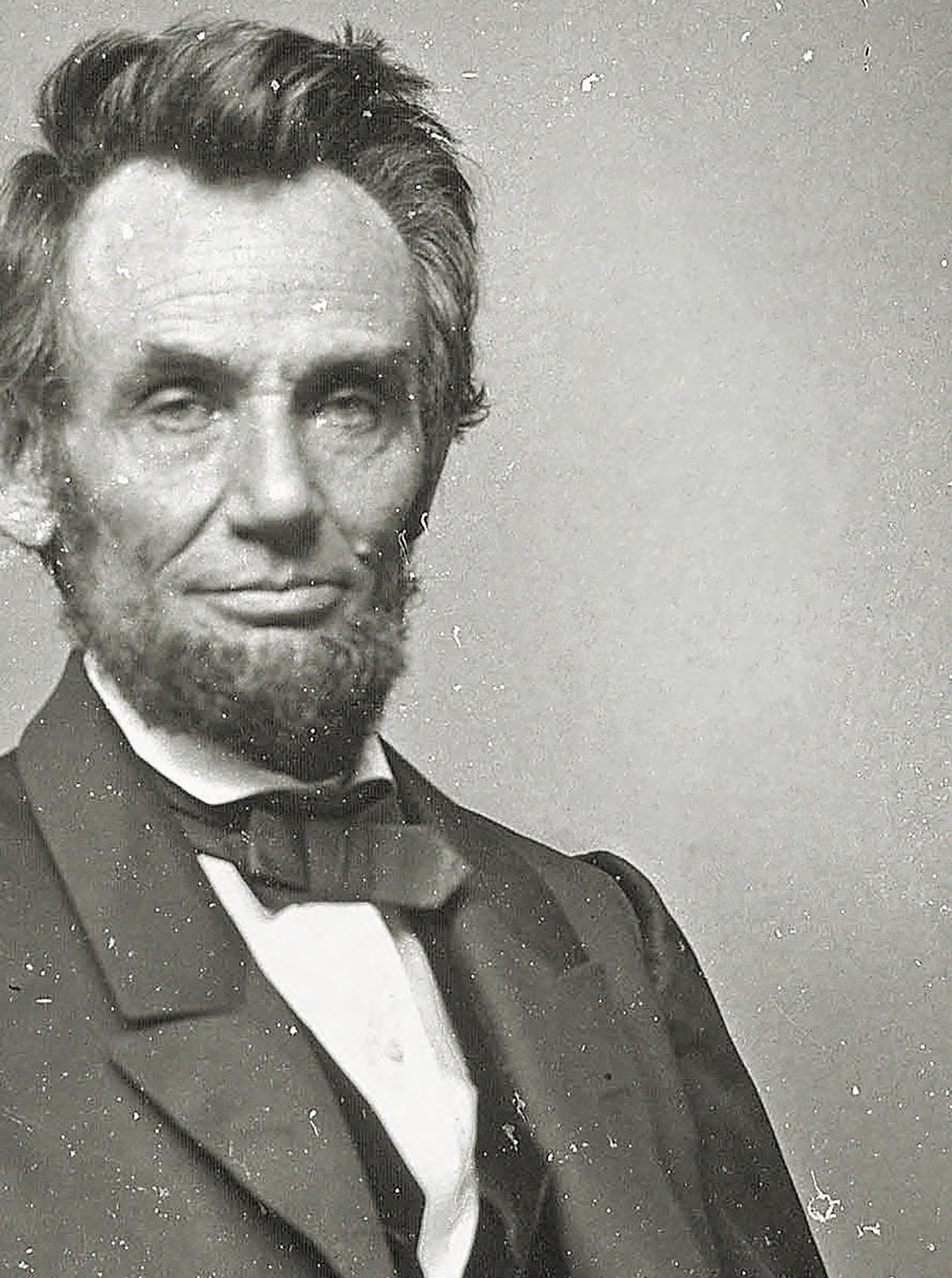

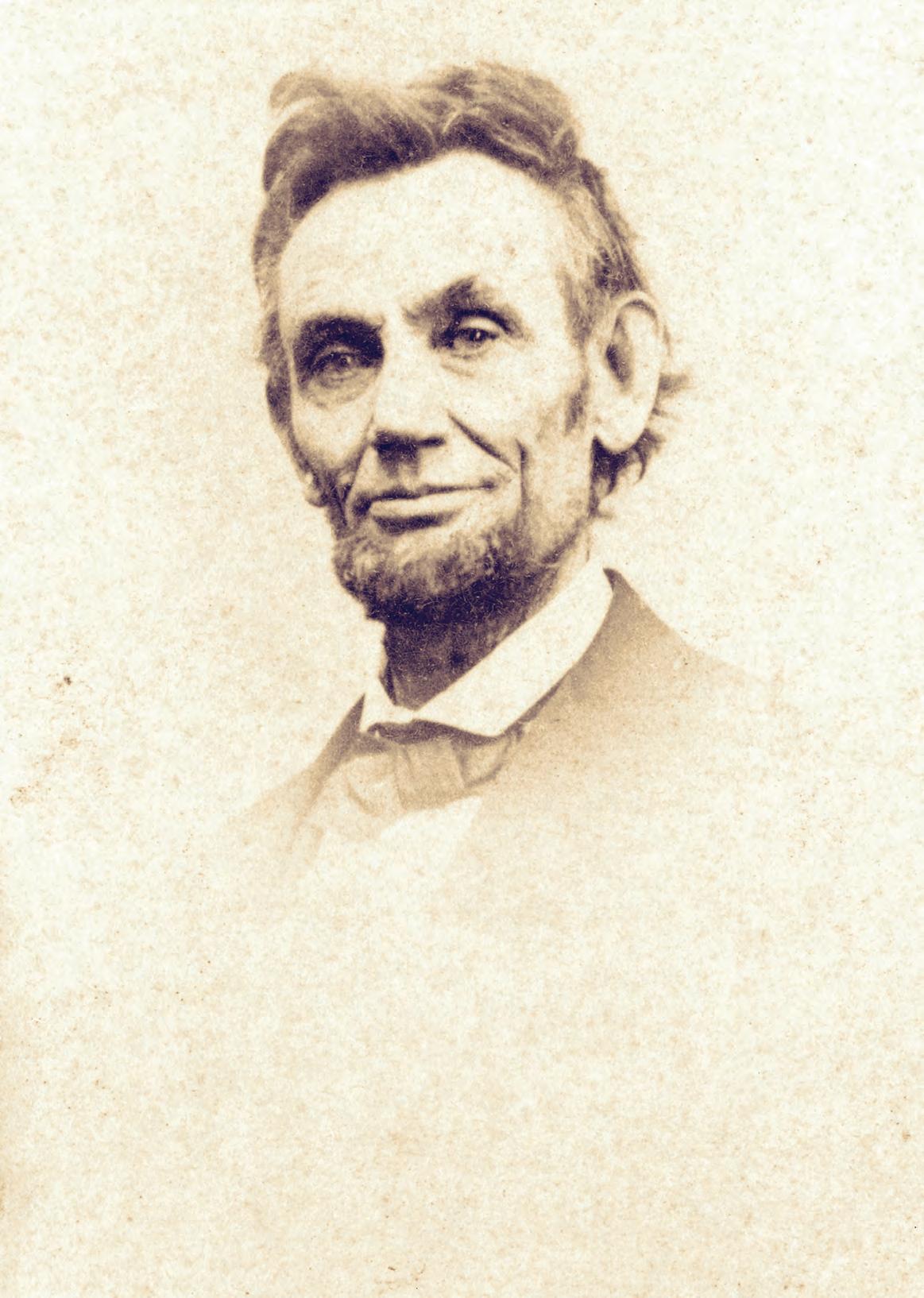

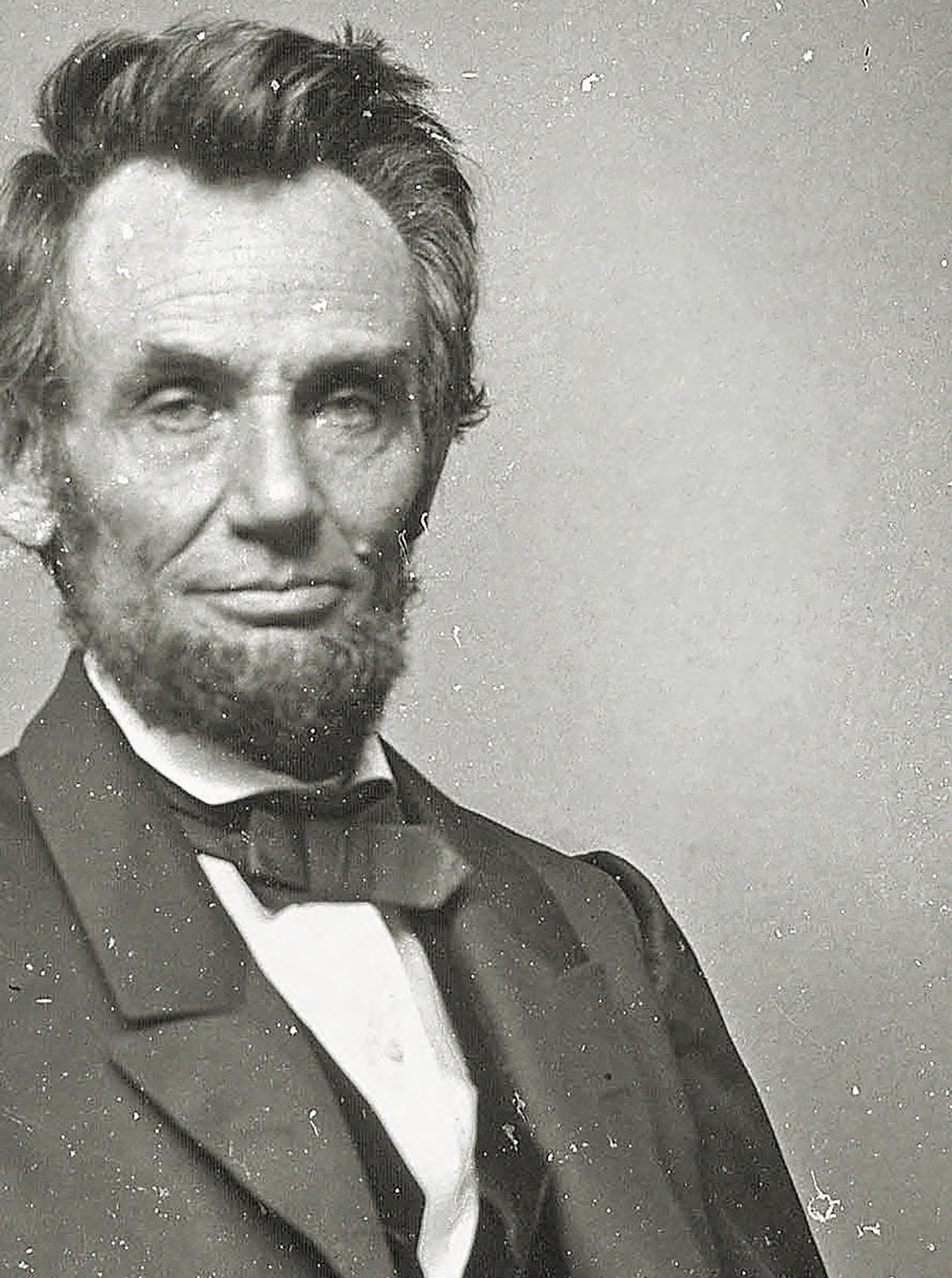

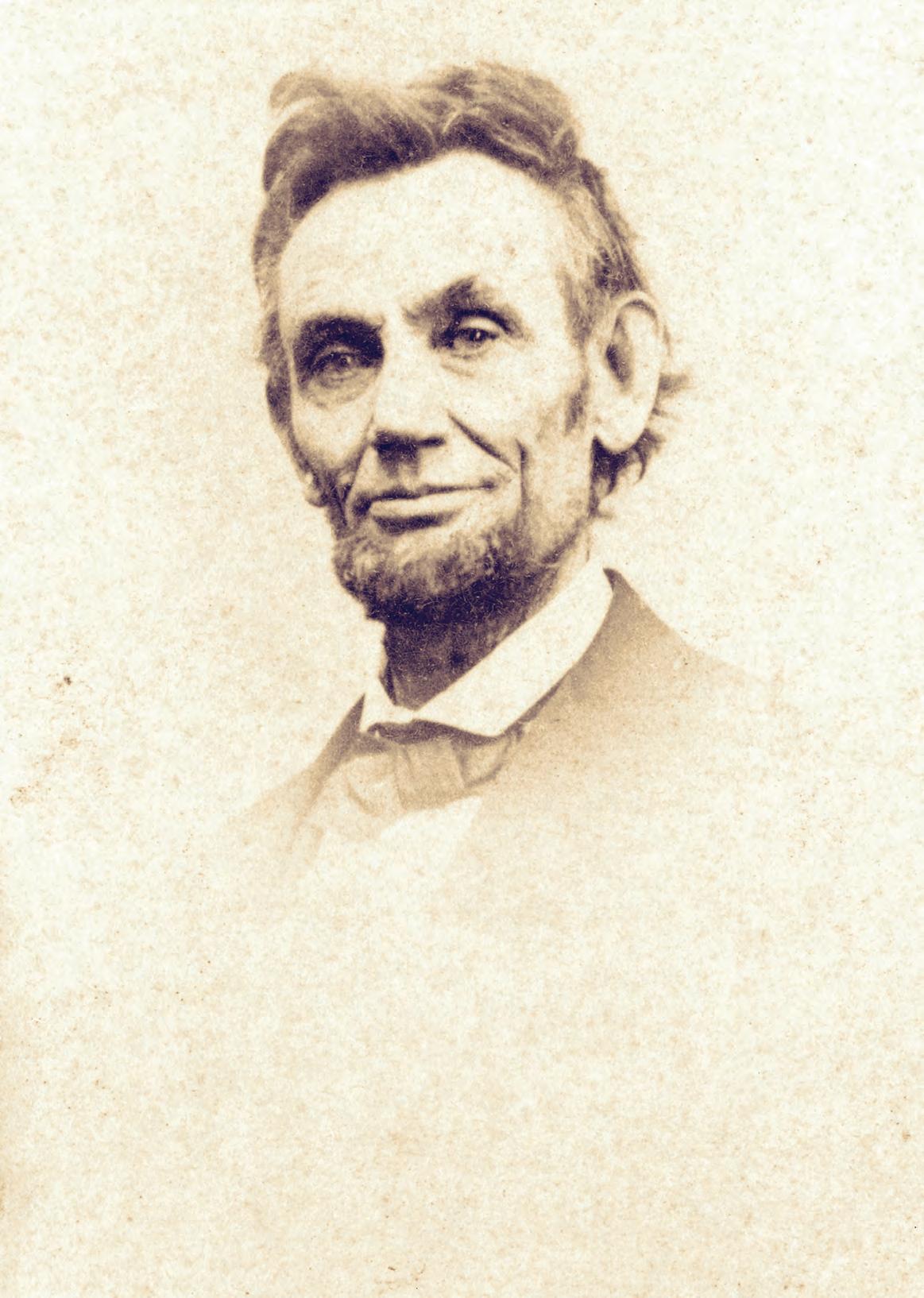

Lincoln’s Legacy

The Lincoln Group of the District of Columbia won the prestigious Wendy Allen Award in November.

From left: Lincoln Group President David J. Kent, artist Wendy Allen, Lincoln Forum Vice Chairman Jonathan White, and Chairman Harold

For Old Abe!

In November, the Lincoln Forum hosted its 27th annual symposium in Gettysburg. The event featured two cable news stars: John Avlon, who spoke on “How Lincoln Helped Win the Peace After World War II,” and Jon Meacham, who delivered an address on Lincoln as a moral leader.

Three biographers discussed their recent books: Walter Stahr on Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase; Elizabeth D. Leonard on Union Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler; and John Rhodehamel on John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln assassination.

Mosaic

Historian and Lincoln Forum Vice Chairman Jonathan White discussed his recent books about Lincoln and African Americans; Roger Lowenstein and Frank J. Williams conferred on how the North financed the Civil War; and Christopher Oakley received a standing ovation for showing how historic photographs and computer technology could pinpoint the location of the platform from which Lincoln gave his epochal “Gettysburg Address.”

Attendees at the symposium enjoyed the all-author book signing, a battlefield tour by Carol Reardon, a concert of Civil War music featuring Jari Villanueva and the Federal City Brass Band. Breakout sessions and panels featured Forum favorites such as Harold Holzer, John Marszalek, Craig Symonds, Edna Green Medford, Christian McWhirter, Edward Steers, J. Matthew Gallman, Michael Green, and Andrew F. Lang.

The Forum’s 2022 Richard N. Current Award of Achievement went to Meacham; the Harold Holzer Book Award went to Lowenstein; and the Wendy Allen Award went to the Lincoln Group of the District of Columbia.

For more information on the Forum, or to join, visit www.thelincolnforum.org.

COURTESY OF SOHO; LIBRARY OF CONGRESS NATIONAL ARCHIVES; PHOTO BY MELISSA A. WINN

AMERICAN HISTORY 8 AMHP-230400-MOSAIC.MAW.CKH.indd 8 1/9/23 6:08 PM

Holzer.

West Coast Preservation

The coastlines and backcountry of San Diego are under threat, and the city’s Save Our Heritage Organization (SOHO), works to prevent major heritage losses through advocacy, preemptive negotiations, public awareness, and education. In November 2022, SOHO released its annual “Most Endangered List,” that includes seven endangered sites. Check out sohosandiego.org for more details.

The California Theatre (1927) at 1122 Fourth Ave., tops the list, as its beautiful Deco ornamentation and Caliente racetrack mural are crumbling. SOHO’s other “most endangered” sites are: Barrett Ranch House (1891) in Jamul, a two-story Victorian farmhouse with distinctive architectural features from the era. Big Stone Lodge (circa 1930) in Poway, a 1930sera resort near the route of a San DiegoEscondido stagecoach line. Granger Music Hall (1898) on East Fourth St. in National City, designed by architect Irving Gill. Presidio Park in Old Town, with rich cross-cultural history related to conflicting cultures and values. The San Diego History Center has restored the Serra Museum and added interpretive video displays, but much work remains to preserve artifacts and historical topography amid proposals for new pedestrian pathways and ADA access. 100-year-old pepper trees in Kensington, which the city had planned to remove because their roots could push up through sidewalks. Several trees have already been cut down. Red Rest and Red Roost Cottages (1894) at La Jolla Cove. A design by architects Alcorn & Benton calls for a new four-story condominium building and reconstruction of the cottages for commercial use. The design is likely to be in the spirit of the architects’ nearby Coast Boulevard Cottages, where two new stories were added behind a shingled 1909 bungalow. Plans have been submitted to the city of San Diego and California Coastal Commission, review is due for completion next year.

Enlist now! Join the volunteer army transcribing the papers and correspondence of notable figures in the collections of the Library of Congress. Launched in 2018, the Library’s “By the People” crowdsourcing campaign has several active projects in progress. Volunteers are helping transcribe, review, and tag digitized pages in the collections of Walt Whitman, Clara Barton, James Garfield, Theodore Roosevelt, and more. As of December 2022, the Library has released more than 831,000 pages for transcription, and about 591,000 have been transcribed. For more information visit: https://crowd.loc.gov

COURTESY OF SOHO; LIBRARY OF CONGRESS NATIONAL ARCHIVES; PHOTO BY MELISSA A. WINN

Call for Volunteers!

SPRING 2023 9 AMHP-230400-MOSAIC.MAW.CKH.indd 9 1/9/23 6:08 PM

Barrett Ranch House

California Theatre

Rev War Soldiers Found at Camden

The Revolutionary War in the South was a mean, snarling affair. It might even be considered our first civil war, pitting Loyalist Americans against those who sought independence.

More than 200 engagements occurred in South Carolina alone, including the August 16, 1780, Battle of Camden. The fight pitted British Lt. Gen. Lord Cornwallis against American Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates, the hero of Saratoga. At Camden, however, despite having numeric superiority, Gates suffered a sound defeat.

In fall 2022, Archaeologists made a significant discovery just a few inches below the battlefield’s surface, the remains of 14 casualties of the fight. The South Carolina Battleground Preservation Trust announced the excavation and South Carolina Institute for Archaeology and Anthropology archaeologist James Legg led the onsite field team.

Some human remains and artifacts were found less than six inches below the surface in several locations across the battlefield. Twelve of the bodies found are Patriot Continental soldiers, one is possibly a North Carolina Loyalist, and one fought for the British 71st Regiment of Foot, Fraser’s Highlanders.

South Carolina Battleground Preservation Trust CEO Doug Bostick put the dig into perspective. “When these young men marched into the darkness on that summer night in 1780, they did so out of love for their country despite the consequences that may befall them. Our intent is to lay them to rest with the respect and honor they earned more than two centuries ago.”

The excavations began September 2022 and lasted eight weeks. Researchers say they hope to compile information about the soldier’s health and diet, age, gender, and race to tell the personal stories of the soldiers and compare the data to historical records. Forensic anthropologists from the Richland County Coroner’s Office are participating in the project to study the remains. To keep abreast of the project, go to scbattlegroundtrust.org.

TOP BID

Helping Hands $6,875

These Gemini G-2C high pressure spacesuit training gloves were part of a second suit produced by the David Clark company for NASA’s Gemini program. They sold in December 2022 on Heritage Auctions for $6,875. When NASA was seeking a suit manufacturer for their upcoming Gemini program, it carried out design level evaluations with B.F. Goodrich and Arrowhead. The David Clark company came in with its own company-funded prototype using its Link-net technology that had been developed for the X-15 program. NASA considered it the superior suit and the contract was awarded to David Clark in 1962 to manufacture the Gemini spacesuits. The early Gemini gloves, such as these ones, used a lace-up restraint on the back of the hand that inhibited manual mobility while pressurized. Later versions of the Gemini gloves used adjustable straps and adjustable palm restraint bars to retain the shape of the pressurized glove on the hand.

COURTESY OF THE SOUTH CAROLINA BATTLEGROUND PRESERVATION TRUST; HERITAGE AUCTIONS, DALLAS PHOTOS BY TOM HUNTINGTON (4)

AMERICAN HISTORY 10 AMHP-230400-MOSAIC.MAW.CKH.indd 10 1/9/23 6:08 PM

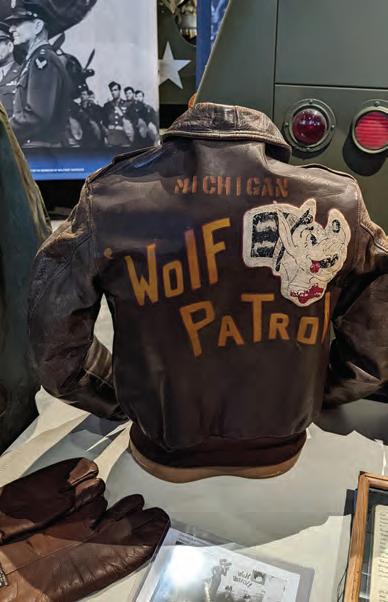

Wide Array

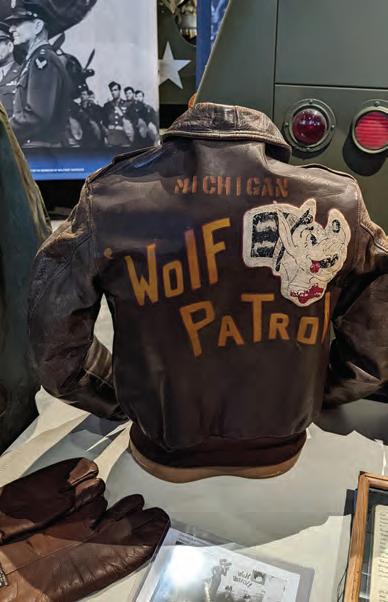

The artifacts in the World War II Experience Museum range from heavy tanks to the personal effects of soldiers. Tank rides are available on certain days.

Naturally, Gettysburg, Pa., is full of places to visit and sites to see related to the Civil War (see page 46), but a new attraction focuses on Gettysburg’s involvement with World War II. The World War II American Experience Museum, just a 10-minute drive from Gettysburg’s Lincoln Square, had a soft opening on June 18 and opened to the public in October. The museum is the work of Frank Buck—a retired Peterbilt truck dealer and long-time collector of World War II memorabilia—and his wife, Loni.

Gettysburg’s Greatest Generation

The Bucks invested $7 million to put up three 12,000-squarefoot buildings on 30 acres of farmland near their home about five miles northwest of Gettysburg. Frank has spent decades collecting nearly 80 World War II vehicles, uniforms, and other memorabilia.

Overshadowed by its Civil War connections, the town of Gettysburg has several ties to World War II, as well. D-Day commander and later President Dwight D. Eisenhower maintained a home in Gettysburg. The town was also the site of a secret U.S. Navy mapmaking office, an army psychological warfare training camp, and a POW camp on the Civil War battlefield where German prisoners were held. The town has applied for American World War II Heritage City status from the National Park Service.

Tickets to the museum are $14 with discounts for veterans, seniors, children, and groups.

COURTESY OF THE SOUTH CAROLINA BATTLEGROUND PRESERVATION TRUST; HERITAGE AUCTIONS, DALLAS

PHOTOS BY TOM HUNTINGTON (4)

SPRING 2023 11 AMHP-230400-MOSAIC.MAW.CKH.indd 11 1/9/23 6:08 PM

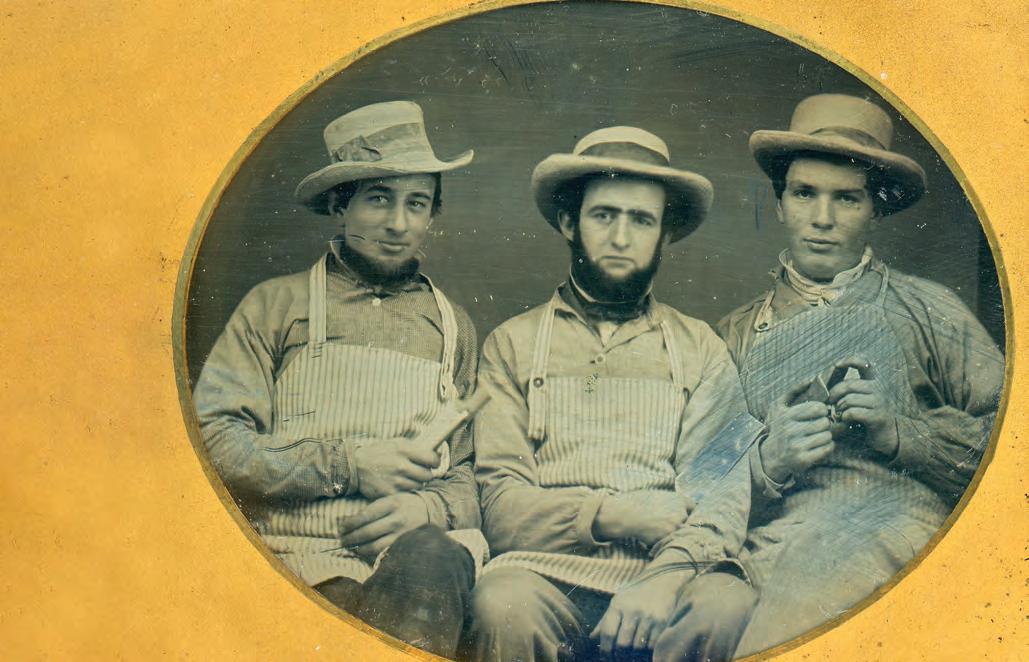

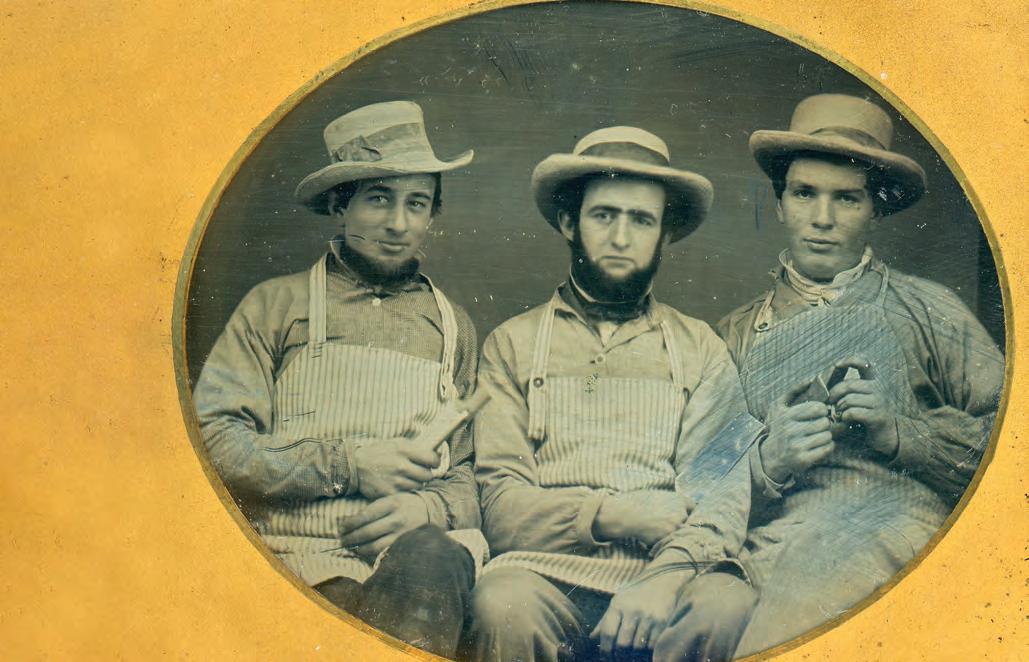

Picture Perfect

Three American workmen pose for an 1850s image holding the tools of their woodworking trade. From left, a spoke shave and a large chisel, while the man on the right uses a sharpening stone to put an edge on a hand plane blade. Evident emotion is uncommon in images taken in the 19th century, but the quiet smiles and shining eyes of these craftsmen indicate pride in their vocation.

What is It?

What was the purpose of this metal marker?

Remember the Alamo

On March 3, 2023, amid anniversary observations for the 1836 Battle of the Alamo, the historic site in San Antonio, Texas, will open a two-story exhibition hall and collections building that will be directly behind the iconic mission. Its 10,000 square feet of gallery space will center on the 430-item collection of Alamo and Texana artifacts donated by British rock star Phil Collins and the recently purchased collection of Spanish colonial artifacts from acclaimed Alamo artist Don Yena and wife Louise.

The latter includes more than 400 items used by South western indigenous people and settlers, from swords and can nons to kitchen utensils, farming implements and ranching gear. Yena also donated six of his large paintings.

The ongoing $388 million overhaul of Alamo Plaza—a part nership between the city, Texas’ General Land Office, and the Alamo Trust—will include a new visitor center and museum in which the collections will ultimately be housed. “When people leave the Alamo,” said trust executive director Kate Rogers, “We don’t want them to say, ‘Is that it?’”

Be the first to email the correct answer to dshoaf@historynet.com, subject heading “Fireman,” and your name will be posted with the description of the item.

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP: DANA B. SHOAF COLLECTION; SMITHSONIAN NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY COURTESY OF THE ALAMO

AMERICAN HISTORY 12 AMHP-230400-MOSAIC.MAW.CKH.indd 12 1/9/23 6:08 PM

Made It Out Alive

It was a perfect late autumn day in the northern Rockies. Not a cloud in the sky, and just enough cool in the air to stir up nostalgic memories of my trip into the backwoods. is year, though, was di erent. I was going it solo. My two buddies, pleading work responsibilities, backed out at the last minute. So, armed with my trusty knife, I set out for adventure.

Well, what I found was a whole lot of trouble. As in 8 feet and 800-pounds of trouble in the form of a grizzly bear. Seems this grumpy fella was out looking for some adventure too. Mr. Grizzly saw me, stood up to his entire 8 feet of ferocity and let out a roar that made my blood turn to ice and my hair stand up. Unsnapping my leather sheath, I felt for my hefty, trusty knife and felt emboldened. I then showed the massive grizzly over 6 inches of 420 surgical grade stainless steel, raised my hands and yelled, “Whoa bear! Whoa bear!” I must have made my point, as he gave me an almost admiring grunt before turning tail and heading back into the woods.

But we don’t stop there. While supplies last, we’ll include a pair of $99 8x21 power compact binoculars FREE when you purchase the Grizzly Hunting Knife.

Make sure to act quickly. The Grizzly Hunting Knife has been such a hit that we’re having trouble keeping it in stock. Our first release of more than 1,200 SOLD OUT in TWO DAYS! After months of waiting on our artisans, we've finally gotten some knives back in stock. Only 1,337 are available at this price, and half of them have already sold!

Knife Speci cations:

• Stick tang 420 surgical stainless steel blade; 7 ¼" blade; 12" overall

• Hand carved natural brown and yellow bone handle

• Brass hand guard, spacers and end cap

I was pretty shaken, but otherwise ne. Once the adrenaline high subsided, I decided I had some work to do back home too. at was more than enough adventure for one day.

Our Grizzly Hunting Knife pays tribute to the call of the wild. Featuring stick-tang construction, you can feel con dent in the strength and durability of this knife. And the hand carved, natural bone handle ensures you won’t lose your grip even in the most dire of circumstances. I also made certain to give it a great price. After all, you should be able to get your point across without getting stuck with a high price.

• FREE genuine tooled leather sheath included (a $49 value!)

The Grizzly Hunting Knife $249 $79* + S&P Save $170

California residents please call 1-800-333-2045 regarding Proposition 65 regulations before purchasing this product.

*Special price only for customers using the offer code. 1-800-333-2045

Your Insider Offer Code: GHK216-02

Stauer, 14101 Southcross Drive W., Ste 155, Dept. GHK216-02, Burnsville, MN 55337 www.stauer.com Stauer® | AFFORD THE EXTRAORDINARY ® A 12-inch stainless steel knife for only $79

‘Bearly’

Stauer Clients

About Our Knives “The feel of this knife is unbelievable... this is an incredibly fine instrument.” — H., Arvada, CO “This knife is beautiful!” — J., La Crescent, MN 79 Stauer®Impossible Price ONLY Join more than 322,000 sharp people who collect stauer knives EXCLUSIVE FREE Stauer 8x21 Compact Binoculars -a $99 valuewith your purchase of the Grizzly Hunting Knife AMHP-230214-06 Stauer Grizzly Hunting Knife.indd 1 12/30/2022 10:32:24 AM

I

What

Are Saying

Swing Low, Sweet Brinks Truck

by Peter Carlson

“SAY THIS AFTER ME,” Reverend Ike urged his flock: “I have no fear of money.”

“I have no fear of money,” the congregation repeated.

American Schemers

“Money is not against my religion,” Reverend Ike said.“Money is not against my religion,” the crowd echoed. Money certainly didn’t violate the gospel of Reverend Ike. He loved money with a religious zeal, and he urged his followers to love lucre, too. “If thy religion cannot stand money, thy religion is bad, not money,” he said. “I never understood preachers who get up and talk about how terrible money is, then, before they sit down, they ask for some.”

The audience laughed, and Reverend Ike proclaimed that he had no theological qualms about enjoying the riches his devotees donated. “Do you know how much I love the precious Lord when I sit in my Rolls Royce limousine?”

The United States was the first nation on earth to establish freedom of religion, and that freedom spawned a class of preachers who create their own churches and preach their own theologies. Among the most entertaining was Reverend Ike. He was born Frederick Joseph Eikerenkoetter II in South Carolina in 1935, son of a Baptist minister of Dutch and Indonesian heritage and an African American schoolteacher.

At 14, he became assistant pastor to his father’s congregation, later earning a theology degree at Chicago’s American Bible College. After a stint as a U.S. Air Force chaplain, he moved to Boston in 1964 and founded the Miracle Temple, where he practiced the art of faith healing.

COURTESY OF WINSTON VARGAS AP PHOTO/BEBETO MATTHEWS

AMERICAN HISTORY 14

AMHP-230400-SCHEMERS.indd 14 1/9/23 11:32 AM

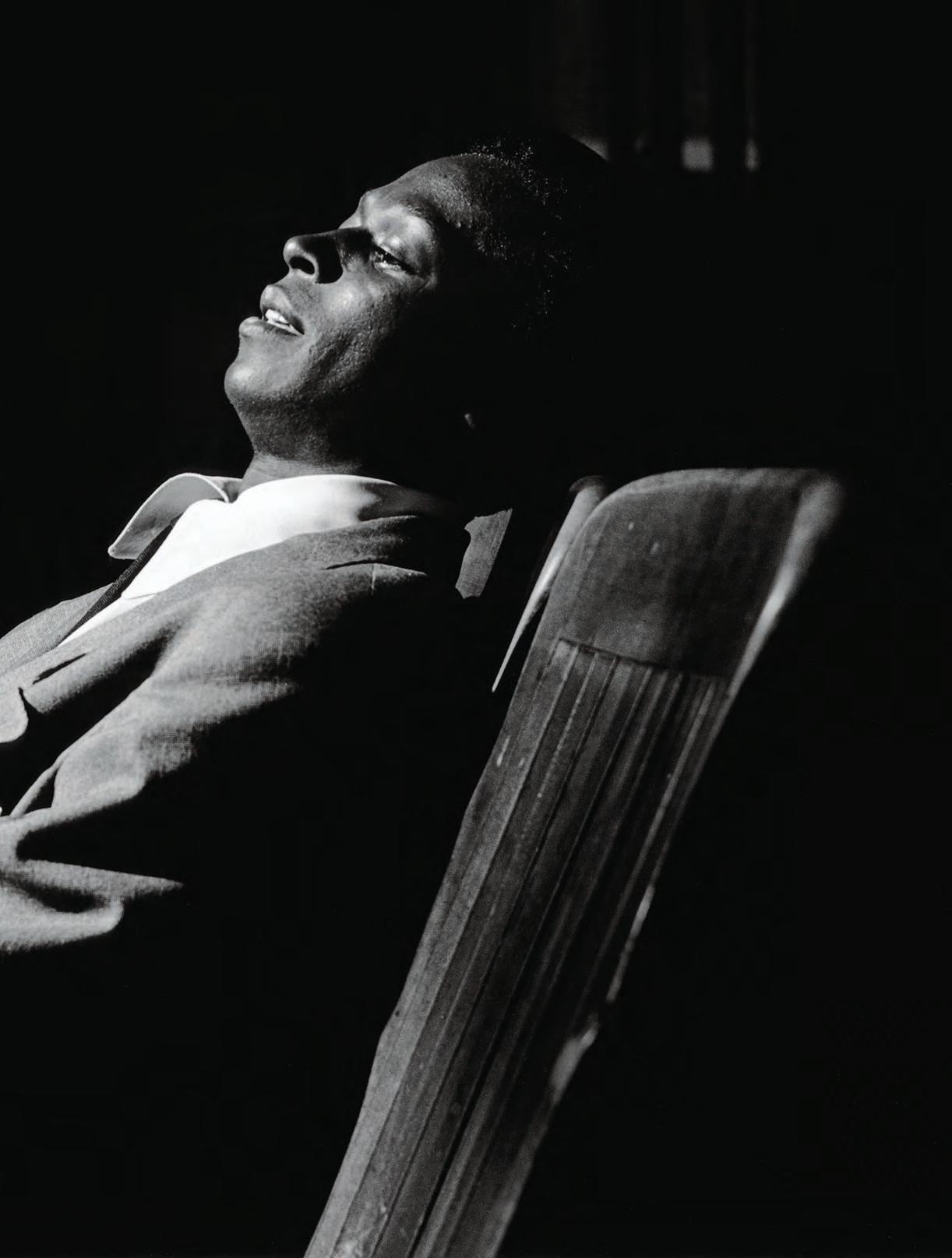

Prosperity Gospel Reverend Ike relaxes, surrounded by riches that exemplify his religious creed to “see green—money up to your armpits.”

“I was just about the best in Boston,” he told an interviewer. “Snatching people out of wheelchairs and off their crutches, pouring some oil over them while I commanded them to walk or see or hear.”

Healing the sick is noble work, but it doesn’t pay the bills, especially if you’re not a physician and can’t charge for the service. After two years, the Rev. Eikerenkoetter fled to Manhattan to preach what he dubbed “Prosperity Now.” He rented a Harlem theater, billed himself on the marquee as “Rev. Ike,” and trademarked the nickname. His materialist gospel and theatrical exhortations attracted a large, mostly Black, following and soon hundreds of radio stations were broadcasting his sermons. In 1969, he paid $500,000 for a 5,000-seat movie theater at Broadway and West 175th that he christened the Palace Cathedral. By the mid-1970s, his over-the-top sermons were airing on TV across America. “Along with Jim Bakker, Jimmy Swaggart and Pat Robertson,” The New York Times noted, “he was one of the first evangelists to grasp the power of television.”

Preaching before huge enlargements of $1,000 bills and attired in expensive suits—some funereal black, others flamboyant orange or pink— Ike informed followers that the first step to getting rich was to visualize the cash they craved: “Close your eyes and see green—money up to your armpits, a roomful of money and there you are, just tossing around in it like a swimming pool.”

He encouraged disciples to write him letters detailing their problems— and to be sure to include a generous donation. In return, he’d send a prayer cloth capable of working “miracles of healing, blessing and deliverance,” plus advice on how to solve problems. His replies, he admitted, were all identical. “Most people think there are separate answers to each problem,” he told an interviewer in 1972. “There’s not but one problem. If I can get a person to believe in himself, that’s my whole ministry, simply to inspire.”

Norman wrote. “Rev. Ike was its Little Richard.”

Like Little Richard, the reverend loved to sing, and while preaching he’d spontaneously burst into song. “Lots and lots of money ready for my use,” he crooned during one 1972 sermon. “Oh, yes, it’s ready for my use.” And he sang about his favorite possession: “Swing low, sweet Rolls Royce, coming for to carry me home.” He claimed to own “10 or 12” Rolls cars: “My garage runneth over.” Driving a Rolls advertises your wealth, he said. “Therefore I boldly declare: I am rich! I am rich in health, happiness, success, prosperity and moneeeeeeeeey!”

Some preachers insist that every word of the Bible is literally true. Reverend Ike disagreed. He freely interpreted the Good Book. Sure, St. Paul said, “Love of money is the root of all evil” but, Ike explained, what Paul really meant was that “lack of money is the root of all evil.”

Sure, Jesus said, “It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God,” but Ike appended a comic addendum: “Think how terrible it must be for a poor man to get in—he doesn’t even have a bribe for the gatekeeper.”

Put Your Wig on Straight

Reverend Ike didn’t invent the idea of creating a religion that married two American fixations—God and money. That’s an old tradition, known to religious scholars as the “prosperity gospel.” In the late 1800s, Russell Conwell, the Baptist minister who founded Temple University, delivered his famous “Acres of Diamonds” sermon 6,152 times, each time preaching that “it is your duty to get rich.” In 1925, Bruce Barton, an advertising executive and future congressman, published The Man Nobody Knows, which identified Jesus as “the Founder of Modern Business.” In 1952, Methodist minister Norman Vincent Peale published The Power of Positive Thinking, a mega-bestseller that combined religion with self-help pep talks. Peale touted a vacuum cleaner salesman who got rich by repeating a mantra: “If God be for me, then I know that with God’s help I can sell vacuum cleaners.”

The reverend’s brilliant innovation was to combine the “prosperity gospel” with the exuberant flair of African American entertainers. “Norman Vincent Peale would be the movement’s Hank Williams,” journalist Tony

In the 1980s and ’90s, Ike’s oratory evolved, sounding less like Christian sermonizing and more like New Age self-help lectures. “I interpret the Bible psychologically rather than theologically,” he said. He moved to Los Angeles and discoursed on “mental reconditioning” and “The Science of Living ” and “The Power of Fascination.” Of course, he still loved money, evidenced by lectures with titles such as “The Excitement of Money” and “How to Make Money While You Are Sleeping.”

“Money is just like a woman,” he wrote. “Money has emotions. Money has feelings, and if you hurt the feelings of money she is going to stay away from you, or give you trouble.”

Reverend Ike never hurt money’s feelings, and she never left him. When he died at 74 in 2009, he left an estate worth several million dollars—certainly more than enough to bribe heaven’s gatekeeper. Upon his death, Rev. Ike Ministries issued a statement that captured the essence of the founder’s creed: “In lieu of flowers, Rev. Ike would ask that tributes and/or offerings be sent to Rev. Ike Ministries.” H

COURTESY OF WINSTON VARGAS AP PHOTO/BEBETO MATTHEWS SPRING 2023 15

AMHP-230400-SCHEMERS.indd 15 1/9/23 11:32 AM

A 1977 image shows a large flock of Rev. Ike’s followers at his New York City “Palace Cathedral.”

Razor’s Edge

Innovations

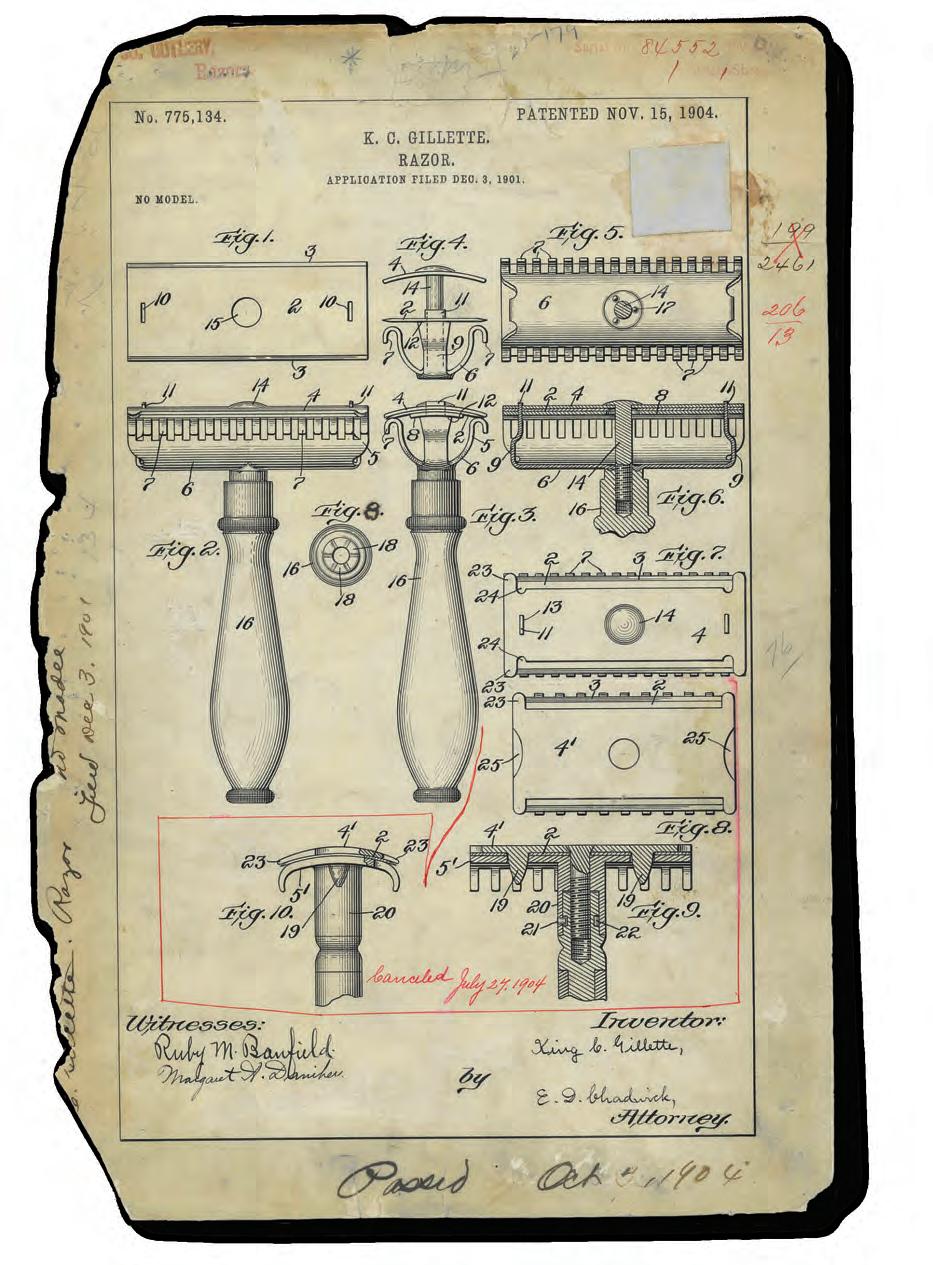

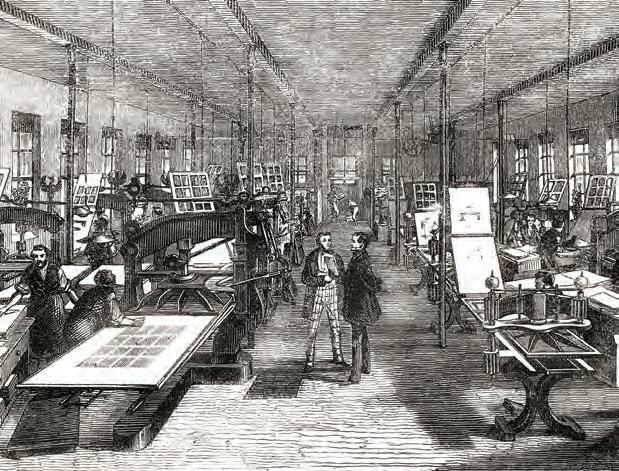

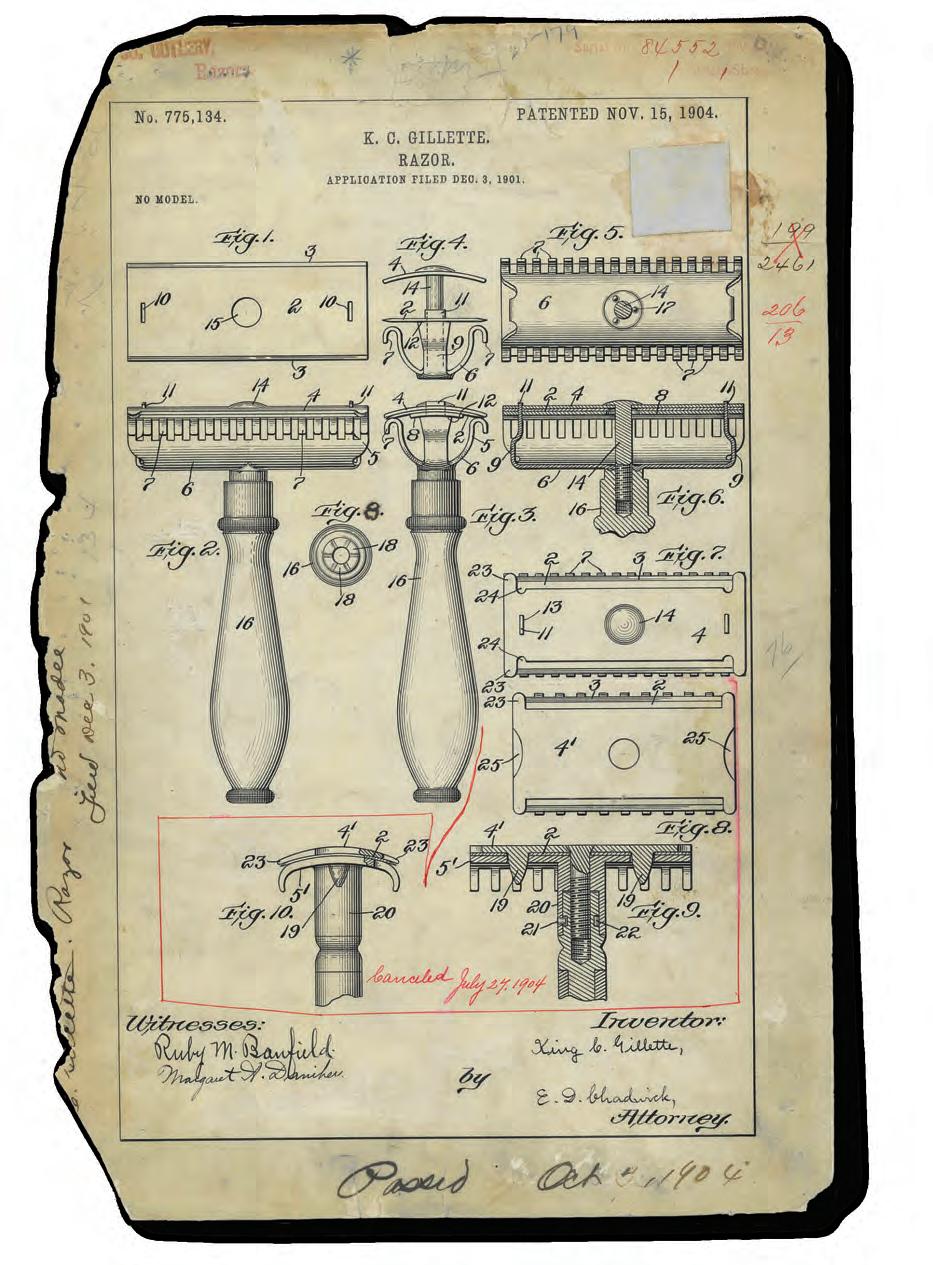

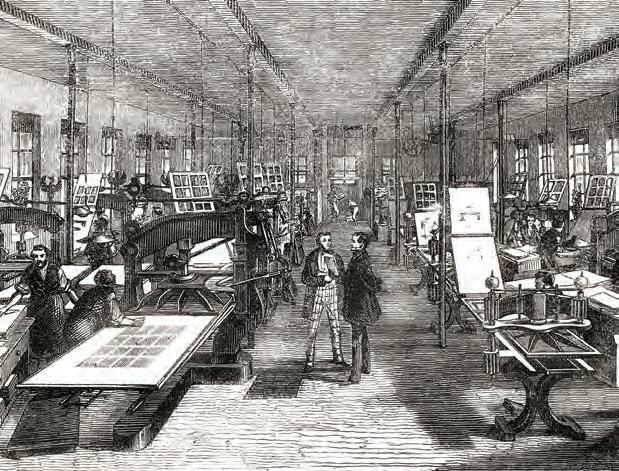

AS A YOUNG INVENTOR, King C. Gillette was inspired by disposable bottle caps to create another disposable item that would integrate itself into everyday use and, thus, be a profitable business venture. In 1895, Gillette worked out the idea for a razor blade that fit into a holder and could be replaced when dull. Engineer William E. Nickerson produced the thin, sharpened steel blades. In 1901, Gillette formed the American Safety

Razor Company, renamed Gillette in 1902. Production began in 1903, and Gillette was granted his patent on November 15, 1904. In 1903, Gillette sold 51 razors and 168 blades. By 1915, he had sold 450,000 razors and more than 70 million blades. Today, the disposable razor is an indispensable item in nearly every home. —Melissa A. Winn

AMERICAN HISTORY 16 NATIONAL ARCHIVES

AMHP-230400-INNOVATIONS.indd 16 1/9/23 11:19 AM

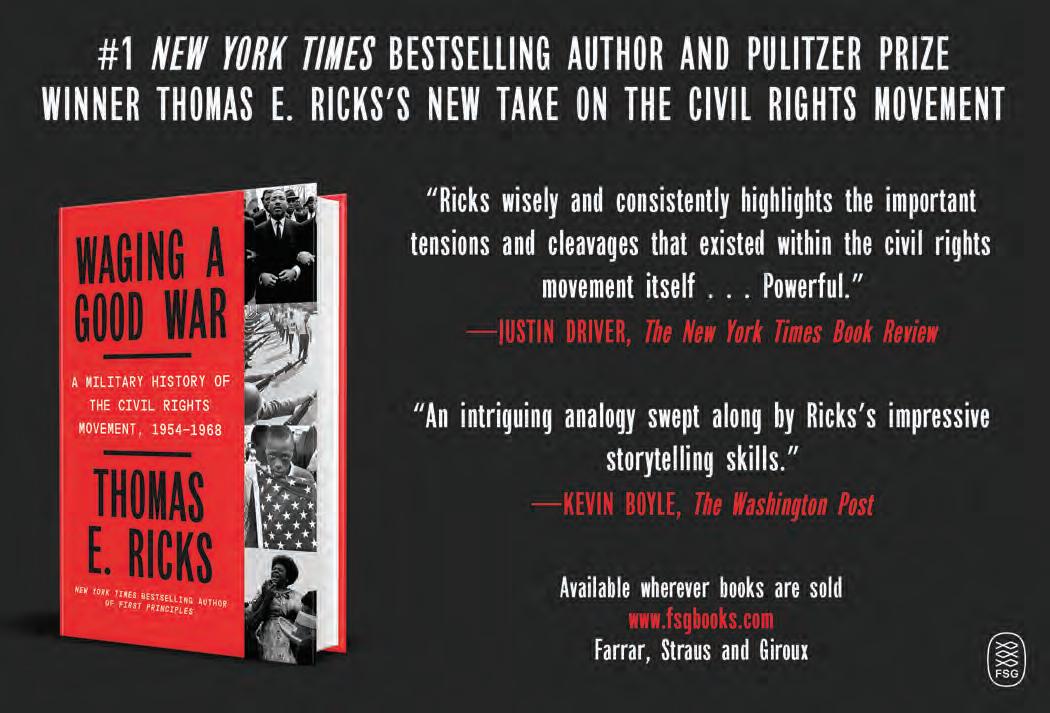

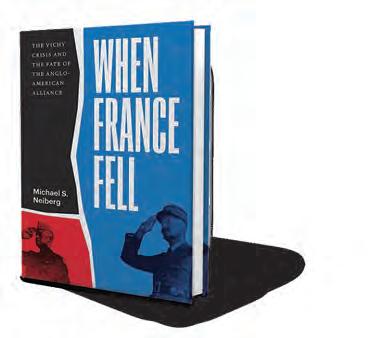

The Day the War Was Lost It might not be the one you think Security Breach Intercepts of U.S. radio chatter threatened lives 50 th ANNIVERSARY LINEBACKER II AMERICA’S LAST SHOT AT THE ENEMY First Woman to Die Tragic Death of CIA’s Barbara Robbins HOMEFRONT the Super Bowl era WINTER 2023 WINTER 2023 Vicksburg Chaos Former teacher tastes combat for the first time Elmer Ellsworth A fresh look at his shocking death Plus! Stalled at the Susquehanna Prelude to Gettysburg Gen. John Brown Gordon’s grand plans go up in flames MAY 2022 In 1775 the Continental Army needed weapons— and fast World War II’s Can-Do City Witness to the White War ARMS RACE THE QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF MILITARY HISTORY WINTER 2022 H H STOR .COM JUDGMENT COMES FOR THE BUTCHER OF BATAAN THE STAR BOXERS WHO FOUGHT A PROXY WAR BETWEEN AMERICA AND GERMANY PATTON’S EDGE THE MEN OF HIS 1ST RANGER BATTALION ENRAGED HIM UNTIL THEY SAVED THE DAY JUNE 2022 JULY 3, 1863: FIRSTHAND ACCOUNT OF CONFEDERATE ASSAULT ON CULP’S HILL H In one week, Robert E. Lee, with James Longstreet and Stonewall Jackson, drove the Army of the Potomac away from Richmond. H THE WAR’S LAST WIDOW TELLS HER STORY H LEE TAKES COMMAND CRUCIAL DECISIONS OF THE 1862 SEVEN DAYS CAMPAIGN 16 April 2021 Ending Slavery for Seafarers Pauli Murray’s Remarkable Life Final Photos of William McKinley An Artist’s Take on Jim Crow “He was more unfortunate than criminal,” George Washington wrote of Benedict Arnold’s co-conspirator. No MercyWashington’s tough call on convicted spy John André HISTORYNET.com February 2022 CHOOSE FROM NINE AWARD - WINNING TITLES Your print subscription includes access to 25,000+ stories on historynet.com—and more! Subscribe Now! HOUSE-9-SUBS AD-11.22.indd 1 12/21/22 9:34 AM

Bad Medicine

Rising political star William Crawford’s life was upended when medicine he took for a skin ailment brought on a debilitating stroke.

If You Have Your Health…

by Richard Brookhiser

On May 13, four days before the 2022 Pennsylvania primaries, John Fetterman, the lieutenant governor running for the Democratic Party’s senatorial nomination, suffered a stroke. Fetterman won his primary by a huge margin, and took a lead in the polls against the GOP winner, Mehmet Oz. But he did not appear in public to campaign until October, and when he did, his speech was choppy and halting. Even a friendly review of Fetterman’s performance in his lone debate with Oz conceded that “while his overall points were intelligible, it was at times genuinely difficult to understand some of his sentences.”

Fetterman was not the first American with a disability to run for office. A candidate’s ailment can be the thing that sinks him, or a mark of his gumption, as shown by the sudden onsets of paralysis that afflicted two presidential candidates, one in the 19th century, and one in the 20th.

As James Monroe, last of the “Founding Fathers” presidents, neared the end of his administration (1817-25), a pack of younger men, all belonging, like him, to the first Republican Party, panted to succeed him: John Quincy Adams, his Secretary of State; John Calhoun, his Secretary of War; Henry Clay, Speaker of the House; and Andrew Jackson,

the hero of New Orleans during the War of 1812. The favorite of the field, though, was William Crawford. Handsome, tall, with a receding hairline that gave him gravitas, Crawford had served as a senator from Georgia and as a diplomat. In 1816, he had challenged Monroe for the Republican nomination, standing down at the last minute and accepting the job of Treasury Secretary instead on the grounds that he was young enough to wait. He spent the Monroe years scheming to undermine his rivals. Adams, in a sour diary entry, called Crawford “a worm preying upon the vitals of the administration within its own body.” Ex-presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Madison liked the worm, however, welcoming him on visits to Monticello and Montpelier as if anointing the heir apparent.

Then, in the fall of 1823, disaster struck. Medicine that Crawford took to cure a skin condition instead brought on a stroke. At first he could not

COURTESY OF THE DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY

AMERICAN HISTORY 18 AMHP-230400-DEJAVU.indd 18 1/9/23 10:33 AM

Déjà Vu

H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H

Veteran PIN-UPS FOR VETS Gina Elise’s visit: pinupsforvets.com Supporting Hospitalized Veterans & Deployed Troops Since 2006 Pin-Ups For Vets raises funds to better the lives and boost morale for the entire military community! When you make a purchase at our online store or make a donation, you’ll contribute to Veterans’ healthcare, helping provide VA hospitals across the U.S. with funds for medical equipment and programs. We support volunteerism at VA hospitals, including personal bedside visits to deliver gifts, and we provide makeovers and new clothing for military wives and female Veterans. All that plus we send care packages to our deployed troops. H H PINUPSFORVETS-nocal.indd 22 8/5/21 7:02 AM

Alicia, Army

Adapt and Overcome

After Franklin Roosevelt lost the use of his legs to polio, his mother wanted him to give up public life. Roosevelt instead worked even harder to win office.

speak, see, or move his limbs; Cabinet-level discussions of what would become known as the Monroe Doctrine proceeded without his input. Over time, Crawford’s condition improved, but progress was slow. In the new year, his supporters called for a caucus in Washington, D.C., of Republican senators and representatives to pick their party’s next presidential candidate. This was the system that had been used to select nominees for a generation. But Crawford’s rivals, sensing his vulnerability, stayed away and denounced the custom as “king caucus.” Crawford won the poll of the rump that showed up, but it was a hollow victory.

A century later, Franklin Roosevelt was considering his own White House run. His fifth cousin (and wife’s uncle) Theodore had brought the office into the family. Franklin himself, after a term in the New York Senate and eight years as undersecretary of the Navy, filled the veep slot on a Democratic ticket swamped by the GOP tsunami of 1920. Even this loss earned Roosevelt points as a show of party loyalty in hard times. But his rise was halted the following summer when, during a vacation cruise in the Bay of Fundy, he suddenly lost sensation in his legs. Decades before the Salk vaccine, he had contracted polio.

Roosevelt found that by using upper body strength he could swing himself across short distances on crutches, and stand with the help of leg braces to give a speech. But despite years of physical therapy and hot spring baths, he never recovered control of his limbs. His mother, Sara, wanted him to retire to the family estate at New York’s Hyde Park and live the life of a permanent patient. But his advisers, his wife Eleanor, and Roosevelt himself were determined he stay in public life. At the 1924 Democratic Convention, he nominated New York Governor Al Smith for president, hailing him as “the Happy Warrior of the political battlefield.” His game hobble to the mic and his gallant smile made the nickname apply to himself. When he ran to succeed Smith as governor four years later, Smith dismissed concerns about his health by saying “a governor does not have to be an acrobat. We do not elect him for his ability to do a double back flip.”

In the 1824 cycle, Crawford’s support slipped as the election approached. With the Republican Party unable to agree on a candidate, it was every man for himself. Since none of the contestants won a majority in the Electoral College, the House of Representatives picked the winner from among the top three finishers. Crawford made the cut, behind Jackson and Adams. But on

the eve of the House vote a friendly kibitzer wrote that even Crawford’s supporters were concerned by the state of his health. He could walk and talk again, and see well enough to play cards without spectacles. Yet his liabilities were “but too evident….I will not express a confidence which I do not feel.”

The tension wore Crawford to the breaking point. One winter day, he went to the White House to discuss with lame-duck Monroe the appointment of customs collectors. When he and the president disagreed, Crawford, cracking, swung up his cane and called Monroe a “damned infernal old scoundrel.” Monroe grabbed the fireplace tongs to defend himself and threatened to ring for the servants to throw Crawford out. Crawford blurted an apology, and left, never to see Monroe again.

When the House met to pick Monroe’s successor in February 1825, Adams won on the first ballot.

Roosevelt won the New York governor’s race in 1928, and was re-elected two years later. In 1932, in the depth of the Depression, he won the Democratic nomination for president, and carried 42 of 48 states. He would go on to win the White House three more times.

Why did Roosevelt succeed where Crawford failed? Crawford had strong rivals able to take advantage of his travails, while Roosevelt faced a GOP blasted by economic catastrophe. But the key difference was their differing disabilities. Crawford’s stroke left him blind and mute as well as immobile, and while he recovered in great part, he was never again 100 percent. As a sympathetic biographer admitted, his “intellect never regained its full tone and power.”

Roosevelt’s paralysis was total, but his mouth, his mind, and his charm were unaffected. A forgiving press never showed him wheelchair bound; eloquence, savvy and will did the rest.

John Fetterman won his senate race, 51 percent to 46.5 percent. Like Roosevelt, he was lucky in his opponent—Mehmet Oz was a TV doctor making his maiden political race. Unlike Crawford or Roosevelt, Fetterman was running for the Senate, not the White House. There are 100 senators, whose job is to vote and advise. There is only one president, who must govern and lead. Voters are more forgiving of would-be solons than candidates for Mount Rushmore. Fetterman also had 21st century science to his advantage: He used voice recognition technology to make up for his impaired hearing, and enough voters were assured by his conviction that he could, and therefore would, recover.

Medical tech can win offices, but office-holding is not for the weak. Young presidents—Carter, Clinton, George W. Bush, Obama—all step down with gray hairs. Good luck to Sen. Fetterman. H

PHOTOQUEST/GETTY IMAGES

AMERICAN HISTORY 20 AMHP-230400-DEJAVU.indd 20 1/9/23 10:34 AM

A HOME AWAY FROM HOME

For Service members, Veterans, and their families.

On any given night, up to 1,300 service members, veterans, and their families can call Fisher House home. These comfort homes are free of charge while a loved one is receiving care at military and VA hospitals. ALL VETERANS. ALL ERAS.

FREE LODGING | HERO MILES | HOTEL FOR HEROES

FISHERHOUSE.ORG

VISIT

AMHP-230214-04 SMG Donation Page.indd 1 12/30/2022 10:28:30 AM

Hidden in Plain Sight

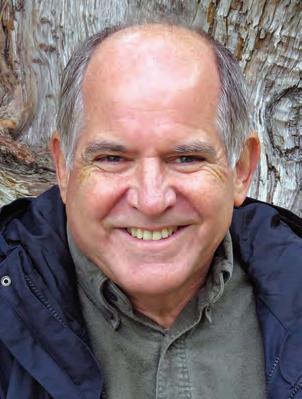

David Goodrich uncovered stories in familiar places on the road

Interview by Melissa A. Winn

The traces of the Underground Railroad hide in the open: a great church in Philadelphia; a humble old house backing up to the New Jersey Turnpike; an industrial outbuilding in Ohio. Over the course of four years, retired climate scientist and author David Goodrich rode his bicycle 3,000 miles to travel the routes of the Underground Railroad. On Freedom Road: Bicycle Explorations and Reckonings on the Underground Railroad covers his odyssey. It’s a comprehensive and engaging look at the history of the places he stopped at along the way, but it’s also a personal journal, documenting the journey of self-discovery both physical and emotional that happens on a bike ride of a lifetime.

What inspired you to write a book about the Underground Railroad?

I am a climate scientist and have written two books about that. I also like to ride my bike. While riding through the small town of Vandalia, Ill., I stopped at a museum and a woman there handed me a heavy brass ring and asked, “Do you know what this is? It’s a slave collar.” She said Vandalia had been a stop on the Underground Railroad, and that’s what got my curiosity going, the idea that I was crossing this invisible river where people on the run were coming up from the South. The book is

based on a couple of rides over a few years. On the Eastern ride I followed Harriet Tubman’s route. She was enslaved in Cambridge, Md., and ultimately took her family to a little chapel in the town of St. Catharines, Ontario. That route took me through all kinds of familiar places that were not really very familiar to me—New York and Philadelphia. Almost like the undersides of cities, and where these formerly enslaved people were on the run.

The second part of the book is about riding from New Orleans, which was the predominant center of the slave trading market, to Lake Erie and a lot of the western routes of the Underground Railroad.

How was riding the route on a bike different than traveling it by car?

I thought that I could get closer to the experience of formerly enslaved people by being on a bike. A bike gives you the sense for the terrain. When I

PHOTO COURTESY OF DAVID GOODRICH PHOTO COURTESY OF DAVID GOODRICH

AMERICAN HISTORY 22

Uphill Climb

From left: Author David Goodrich and friends Rick Sullivan and Lynn Salvo, heading north as they bike the Underground Railroad.

AMHP-230400-INTERVIEW.indd 22 1/9/23 11:26 AM

was riding along the Ohio River, I got the sense of how scary it could be for the formerly enslaved people, because the slave hunters were on both banks. But once you get up in the hills above the Ohio, there was shelter. There were Quaker towns, safe houses, and Underground Railroad houses. Being on a bike can give you some kind of a feeling of what these people were going through. Of course, I was also riding during the daytime, in safety, with Gore-Tex and nice gears and spokes. You also bump into people on the bike and conversations happen. There was once when I was coming up a real steep hill in Kentucky and I was watching a squall come across a field. A guy from a nearby house says to me, “Come on inside quick!” And he gave me a whole story about working in coal mines in Kentucky. Those kind of things happen.

What was it like for you to tackle the history of somebody so mythologized as Harriet Tubman?

What’s interesting is that Harriet Tubman is very well-known now. She’s going to be on the $20 bill! But at the time, she was a wraith. Quite intentionally she made herself as close to invisible as she could. She’s a very tiny woman, but prodigiously strong. In one of her more famed escapes in Troy, N.Y., she disguises herself as the mother of the man she is trying to free. She gets into the marshall’s office and grabs him and yells to this mob outside, “Come on! Let’s get him!” And they manage to free him. At the time, the other conductors are amazed by her. She shows up in Philadelphia with another half dozen people that she’s brought up through Maryland and Delaware. She has all kinds of ingenious escapes along the way, including one in Wilmington, Del., where she smuggles freedom seekers out past slave hunters in a wagon of bricks. It was very easy to find her route in Maryland and Delaware, but after Philadelphia it took a lot of research. And she took many routes. We have all these digital footprints today, and you can’t go anywhere that somebody can’t track you. But even now people in places that are known Underground Railroad safehouses may say, “We think she was here, but we don’t know.” There’s this element even now that one of the most famous Americans is a ghost.

Did you have specific stories or sites you wanted to cover?

One of the references I found was a book in the Library of Congress by Charles Blockson, one of the eminent scholars of Black history. His book had a driving tour of Harriet Tubman sites. So, I thought, “Okay. This is where I need to go.” Then there were particular places along the way,

especially in upstate New York, Albany, the Myers Residence. We know that Harriet Tubman stayed there. In Peterboro, N.Y., there’s the National Abolition Hall of Fame built around Gerrit Smith, a prominent sponsor of the Underground Railroad and of John Brown’s Harpers Ferry raid. It was fascinating to talk to the people who are keeping that history alive.

What was it like to tackle such a difficult subject matter as slavery?

You have to approach it with a certain amount of humility, especially from an old white guy looking at this subject. You have to be careful talking about the Underground Railroad. Best estimates are about 20,000 people traveled it to freedom, but when you compare it with the number of enslaved who were moved in the forced transport from the Upper South of Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina, the old tobacco plantations, to the cotton industry in the Deep South, there is a huge migration that takes place, on the order of a million people. There are places right around Washington, D.C., that are the center of this—for example in Alexandria, Va., the Franklin and Armfield firm, which some refer to as the Amazon of slave trading. People would be marched down the Shenandoah Valley, through Tennessee and onto the Natchez Trace and you can still see the signs of that.

One of the visuals we picked for the cover of the book is a photograph of the Old Trace from Nashville, Tenn., to Natchez, Miss., and it’s like a U-cut through the forest. There were thousands and thousands of chained feet that made that trek. I was riding the Natchez Trace Parkway, which is a beautiful road, and off to the side you see stretches of the Old Trace and you realize that those were people’s chained feet that formed that cut. So, the history bumps right up against you.

It’s not just a history book. It’s a travel journal. Tell us a little about the journey.

Well, I’ve done a lot of long-distance bike rides, and you get into a certain rhythm. People say it must be really hard, and because we have all our gear on the bike, it’s a pretty heavy load. I tell people, I have a job where I only have to work five hours a day. If I do 12 miles an hour and I ride for five hours, I have my 60 miles for the day. I would try to map out those days and end up someplace interesting.

A day’s ride is almost independent of the weather. Big electrical storms, yes, you need to get out of those. But otherwise, big winds, and heat, you have to ride through it. Some of the most interesting riding is in urban areas you know pretty well. Coming out of Philadelphia into New Jersey, there’s a huge suspension bridge. Bridges are windy and that was a lot different to ride on a bike than in a car. Also—the places you hear bad things about, you find out they’re not necessarily true. I had heard all kinds of bad things about Camden, N.J. It had a high murder rate, but it has changed a bit. It may not have fancy bike paths and such, but once again, we met people along the way, that wanted to help us on our way. H

PHOTO COURTESY OF DAVID GOODRICH PHOTO COURTESY OF DAVID GOODRICH SPRING 2023 23

AMHP-230400-INTERVIEW.indd 23 1/9/23 11:26 AM

A Second Wind Climate scientist David Goodrich was inspired by a museum visit to bike the Underground Railroad.

A Splendid Twig

The world’s “largest baseball bat”—120 feet tall and 68,000 pounds—helps make the Louisville Slugger Museum & Factory a can’t-miss destination in downtown Louisville. Opened in July 1996, this is more than a museum. Legendary Hillerich & Bradsby Co. baseball bats are still manufactured here.

IL KY

LEXINGTON LOUISVILLE COURTESY OF THE LOUISVILLE SLUGGER MUSEUM & FACTORY COURTESY OF THE LOUISVILLE SLUGGER MUSEUM & FACTORY (2) AMERICAN HISTORY 24 AMHP-230400-AMERICAN-PLACE.indd 24 1/9/23 8:53 AM

LOUISVILLE SLUGGER MUSEUM & FACTORY

Old Hickory Slugger

American Place

ON A BALMY AFTERNOON in July 1884, John “Bud” Hillerich of Louisville, Ky., did what many other teenage boys might have done in his place: He skipped work to catch a major league baseball game at the city’s Eclipse Park. That seemingly innocuous act of truancy would prove historic not only for Hillerich but also for Louisville and baseball itself, as you’ll have a chance to learn at the Louisville Slugger Museum & Factory here in the heart of the Falls City’s “Museum District.” Just 17, Bud worked at the woodworking shop his father, J.F. Hillerich, had opened in 1855. The younger Hillerich had a passion for America’s budding pastime, and one of the Louisville Eclipse’s stars he ventured to see play was infielder Pete Browning, the so-called “Louisville Slugger.” Known for his hitting efficiency and power, Browning had been struggling at the plate, however—a slide that would continue that day. After Browning broke his bat, Hillerich offered to have his dad personally craft a replacement to the player’s specifications. Browning eagerly accepted, and the next game, his new weapon in hand, immediately broke out of his slump. Partial to more traditional and practical woodworking options, the elder Hillerich had no desire for bat making to become a fulltime endeavor, it should be noted. But by the time Bud assumed the company’s reins in 1894, that— and the manufacturing of sports equipment in general—would be its destiny. Bud patented the “Louisville Slugger” name in 1894, and in 1905 signed the famed Honus Wagner as a promotional spokesman. In 1916, he joined forces with Frank Bradsby to form the Hillerich & Bradsby Co. Among stars to wield Louisville Sluggers over the years were Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb, Stan Musial, and, pictured at right, Hank Aaron, Eddie Mathews, and Joe Adcock of the Milwaukee Braves. –Chris K. Howland

’Round the Horn

H The museum’s current location, 800 W. Main Street, is the fourth site at which the company has manufactured its sports equipment. Nearby museums of note include the Frazier History Museum, the Muhammad Ali Center, and the Kentucky Science Center.

H Prominent in the museum’s foyer is a wall featuring the signatures of every player to have signed a Louisville Slugger contract. Factory tours are available, as are batting cages where you can swing replica bats. To experience what it’s like to face a 90-mph fastball, check out the “Feel the Heat” exhibit.

H Since 2006, the company has proudly manufactured distinctive pink bats for use on Mother’s Day.

SPRING 2023 25 COURTESY OF THE LOUISVILLE SLUGGER MUSEUM & FACTORY COURTESY OF THE LOUISVILLE SLUGGER MUSEUM & FACTORY (2) AMHP-230400-AMERICAN-PLACE.indd 25 1/9/23 8:53 AM

TODAY IN HISTORY

FEBRUARY 14, 1929

KNOWN AS THE ST. VALENTINE’S DAY MASSACRE, SEVEN MEN WERE SLAIN DURING A FAUX POLICE RAID LIKELY STAGED BY AL CAPONE’S CHICAGO OUTFIT. THE VICTIMS, MEMBERS AND ASSOCIATES OF THE RIVAL “NORTH SIDE GANG,” WERE LINED UP AGAINST A BRICK WALL INSIDE A COMMERCIAL TRUCKING GARAGE AND SHOT. BRICKS FROM THE INFAMOUS WALL WERE LATER PURCHASED BY COLLECTORS. MANY ARE ON DISPLAY AT THE MOB MUSEUM IN LAS VEGAS.

For more, visit HISTORYNET.COM/ TODAY-IN-HISTORY

TODAY-CAPONE.indd 22 5/31/22 2:05 PM

Eyeing the Competition

A Small Remodel

by Dana B. Shoaf

Editorial

I AM AN ARCHITECTURE BUFF. My favorite buildings are those built in the late-18th century through the 1860s, from vernacular log structures to whimsical Gothic cottages like Washington Irving’s “Sunnyside on the Hudson.” I even live in a sort-of-fixed-up 1790s stone house. But when this country mouse goes to the big city, I’m just agog at the Brutalist, Beaux Arts, and Richardson Romanesque buildings around me. As for skyscrapers (P. 36), the Chrysler Building in New York City is my favorite. I turn into full tourist mode when I’m there, and stand and gawk at its marvelous summit when it comes into view. Ever take a Chicago River Architecture Cruise? It’s another opportunity to admire the towering built environment of a great city.

In one small way, magazines are like buildings in that their

structure allows them to be remodeled every once in a while, refreshed and updated, just as those architects tinkered with the tops of their skyscrapers. You’ll notice some changes in this edition of American History. For the near future, I’ll be the acting editor of the magazine, and some new departments are being introduced in this issue. A bit of a remodel if you will.

Our hope is that, like me when I see the Chrysler Building, you’ll stare at AHI’s pages and enjoy what you see. Please let us know what you think! And even though we are well on our way into 2023, Happy New Year! H

SHUTTERSTOCK SPRING 2023 27

AMHP-230400-EDITORIAL.indd 27 1/9/23 5:55 PM

One of the iconic eagles on the Chrysler Building seems to glare at a skyscraper under construction..

PHOTO CREDIT

The Roar She Heard

AMERICAN HISTORY 28 AMHP-230400-ABIGAIL.indd 28 1/9/23 8:36 AM

This depiction of the Battle of Bunker Hill was painted during the Revolutionary War. British warships surround the Charlestown Peninsula.

Life DuringWartime

Abigail Adams survived siege and smallpox, and kept her husband’s spirits up during dark times

By Jon Mael

By Jon Mael

PHOTO CREDIT

AMHP-230400-ABIGAIL.indd 29 1/9/23 8:36 AM

On June 17, 1775, a vicious battle rocked Bunker Hill in Charlestown, Mass. That first major engagement of the Revolution saw British Commander in Chief William Howe lead around 2,000 Regulars in what Howe expected to be a quick victory over 1,200 colonists commanded by Colonel William Prescott. Howe guessed wrong. The fierce, bloody fighting raged through the night. From a hillside miles away, Abigail Adams, 30, and son John Quincy, 7, watched with excitement and anxiety.

The Adams family lived in Braintree, a small coastal town 12 miles south of Boston. Abigail’s husband, John, a lawyer and key figure in the insurrection, had been gone since April, when he left on a meandering journey, eventually arriving in Philadelphia to attend the Second Continental Congress that convened May 10. John’s departure began a long separation that left Abigail Adams and their four children in one of the most dangerous places on earth—a city under siege—for nearly two years. She would have to run the family farm, keep her children safe, and husband the family’s finances. Abigail’s letters to John during this time, some of the most reliable accounts of significant early events in the Revolution, influenced decisions being made in Philadelphia that shaped the nation.

John Adams and Abigail Smith met in 1759. He was 25, living with his parents in Braintree; she was 15, also at living at home in Weymouth, just to the south. Writing was the easiest way to communicate, and when they began courting in 1764, the two established themselves as exuberant letter writers. Honest, poetic, tragic, joyful, and deeply thoughtful letters flew back and forth between the young romantics. He nicknamed her “Portia,”

for the independent-minded heroine of The Merchant of Venice, and that was how she signed some letters. The couple married on October 25, 1764, when John was 29 and Abigail 19. They welcomed their first child, Abigail—nicknamed “Nabby”—the following year. By the time John left for Philadelphia in April 1775, John Quincy, Thomas, and Charles had arrived.

Like her husband, Abigail firmly believed in the American experiment and staunchly opposed slavery. She relished the Boston Tea Party. After Lexington and Concord in April 1775, she wrote to John and many friends and acquaintances, expressing joy and anxiety. In a letter to rebellious Plymouth playwright Mercy Otis Warren, Abigail described her emotions following the fighting. “What a scene has opened upon us since I had the favor of your last!” she wrote May 2. “Such a scene as we never before experienced, and could scarcely form an idea of. If we look back we are amazed at what is past, if we look forward we must shudder at the view.”

Rebel Bostonians, having stepped collectively into the unknown, feared for their future. Abigail found a tonic for unease in her excitement at seeing the patriotism she had long advocated taking

AMERICAN HISTORY 30 EVERETT COLLECTION/BRIDGEMAN IMAGES PREVIOUS SPREAD: BOSTON MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS; THIS PAGE: © DON TROIANI (B.1949), ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 2022/BRIDGEMAN IMAGES

AMHP-230400-ABIGAIL.indd 30 1/9/23 8:37 AM

The Whites of Their Eyes Colonel William Prescott, in red waistcoat, readies his patriot militia for approaching British troops during the Battle of Bunker Hill.

root and spreading. “Our only comfort lies in the justice of our cause,” she wrote. She urged Mercy not to leave Plymouth for relative safety inland, adding, with the characteristic vehemence that often outdid her husband’s: “Britain Britain how is thy glory vanished—how are thy annals stained with the Blood of thy children.”

AS ABIGAIL WAS WRITING to Mercy, John, now in Hartford, Conn., was writing to Abigail. He knew that in wartime even agrarian Braintree was bound to suffer. “Our hearts are bleeding for the poor People of Boston,” he wrote May 2. “What will, or can be done for them I can't conceive. God preserve them.”

In that letter, John told Abigail he had purchased books on military strategy and said that if his brothers were interested, he’d be able to train them to be officers. “Pray [sic] write to me, and get all my friends to write and let me be informed of every thing that occurs,” he wrote.

Abigail took his request seriously. In a lengthy May 24 letter, she recounted an incident in Weymouth the previous Sunday morning. She awoke at 6:00 and learned the Weymouth bell had been ringing, that cannoneers there had fired three shots to sound an alarm, and that drums had been beating. Abigail hurried the three miles to her hometown and found everyone, even physician Cotton Tufts, “in confusion.” She described a wild scene, the result of four British boats anchoring within sight of Weymouth Harbor.

According to Abigail, a rumor had spread that 300 Redcoats had landed and were about to march through town. Residents began scrambling to fight or run. Abigail’s family fled. “My father’s family flying, the Dr. in great distress, as you may well imagine,” she wrote, “for my aunt had her bed thrown into a cart, into which she got herself, and ordered the boy to drive her off to Bridgewater which he did.”

Abigail was describing the “Grape Island Incident.” According to her letter, 2,000 local men gathered to fight, but the British never sent troops ashore. Instead, on Grape Island, a minor land mass in Boston Harbor, they stocked a barn with hay. The Weymouth men procured a small boat, intending to torch barn and contents. “We expect soon to be in continual alarms, till something decisive takes place,” Abigail wrote.

THOUGH NOT DECISIVE, Bunker Hill was a British victory, earned at

great human cost and a boost to patriot morale because neophyte freedom fighters had stood their ground and were not overrun. The battle personally touched Abigail and John. Their good friend and physician Joseph Warren (no relation to Mercy) had died in action. “God is a refuge for us.—Charlestown is laid in ashes,” Abigail wrote to John on June 18. “The Battle began upon our intrenchments upon Bunkers [sic] Hill, a Saturday morning about 3 o'clock and has not ceased yet and tis now 3 o'clock Sabbeth [sic] afternoon.”

In a passage of the same letter written June 20, Abigail lamented her inability to gather quality intelligence for John about the battle. “I have been so much agitated that I have not been able to write since Sabbeth day,” she wrote. “When I say that ten thousand reports are passing vague and uncertain as the wind I believe I speak the Truth. I am not able to give you any authentic account of last Saturday, but you will not be destitute of intelligence.”

In reality, Abigail had a knack for threshing fact from fiction—over the years she heard many rumors of John’s death by all manners, including poisoning, but never believed any. Regarding Bunker Hill, she was able to assemble and recount a reasonably detailed narrative of events there, and she assured John that news of Warren’s death was true.

On the same day as the battle, George Washington was named commander in chief of the Continental Army. He rushed to Boston, intent on forcing the British to evacuate. Abigail first met him July 15, 1775, less than a month after Bunker Hill, with the city still under massive financial and military stress. The next day, she wrote that the appointments of Washington and

SPRING 2023 31

EVERETT COLLECTION/BRIDGEMAN IMAGES PREVIOUS SPREAD: BOSTON MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS; THIS PAGE: © DON TROIANI (B.1949), ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 2022/BRIDGEMAN IMAGES

Where She Wrote Her Letters

An 1849 painting shows, on the left, the home of John and Abigail Adams. John Quincy Adams was born in the house on the right. Both properties are now maintained by the National Park Service.

AMHP-230400-ABIGAIL.indd 31 1/9/23 8:37 AM

Abigail lamented her inability to gather intelligence about the Battle of Bunker Hill for John.

Portraits of American Destiny

This British map shows the Americans’ approach to the Battle of Bunker Hill, their earthworks, and British troops in red. At right, John Adams as he appeared during the Revolutionary War.

General Charles Lee to positions of command had given locals “universal satisfaction,” but she also pointed out that the people would support leaders only as long as they were delivering “favorable events.” Washington displayed “dignity with ease, and complacency, the gentleman and soldier look agreeably blended in him,” Abigail wrote. “Modesty marks every line and feature of his face.” By the time that note would have reached John, he was going through a grave embarrassment—one threatening both his budding political career and worldwide geopolitics.

IN THE SUMMER OF 1775, many members of Congress believed war with Britain was still avoidable. On July 8, Congress signed the “Olive Branch Petition.” Written by John Dickinson, a Pennsylvania delegate, the document was a final reach for peace. That outcome was a long shot, but the British intercepted an inflammatory July 24 letter from John Adams to Colonel James Warren, Mercy’s husband. In that communique, Adams suggested to Warren that by now the colonists should have “completely modeled a constitution,” “raised a naval power and opened all our ports wide,” and “have arrested every friend to government on the continent and held them as hostages for the poor victims in Boston.”

Circulation by the enemy of these statements sank all hopes of diplomacy. After that episode, Abigail resumed signing letters “Portia.”

Through eight months of siege, Abigail’s updates became steadier and her commentary

sharper. “Tis only in my night visions that I know anything about you,” she wrote October 21, needling John for his laggard epistolary ways but also reporting a wide range of goings-on around Boston. A wood shortage meant bakers would only be able to work for a fortnight. Biscuits had shrunk in size by half. The British were constructing a fort near the docks, and the Continental Army was short on provisions.

In that letter, Abigail also commented on Dr. Benjamin Church, a supposed patriot who had been caught passing coded information about the forces surrounding Boston to the British. Locked up by Washington’s men, Church had been dumped as the Continental Army’s “Director General” of medicine and was awaiting arraignment. “It is a matter of great speculation what will be [Church’s] punishment,” Abigail wrote. “The people are much enraged against him. If he is set at liberty, even after he has received a severe punishment I do not think he will be safe.”

Abigail was in mourning. Her mother, Elizabeth Quincy Smith, had died in Weymouth October 1. In his grief, Abigail’s father, Parson William Smith, had lost “as much flesh as if he had been sick,” she wrote, adding that her sister Betsy looked “broke and worn with grief.” She lamented John’s chronic absences, estimating that in 12 years of marriage, they had only actually been together six.

WASHINGTON’S TROOPS quietly ringed Boston in a martial noose, placing cannons on high ground that forced the British to depart by sea at the end of March 1776. The warships and transports that carried the enemy away, Abigail wrote on March 17, amounted to the “largest fleet ever seen in America;” she likened the bristle of masts and billows of sails to a forest. Washington allowed Howe’s men to leave unmolested on the proviso that the Redcoats not burn the city. The foe was as good as his word, though some Britons looted like pirates on holiday. Dirty tactics notwithstanding, though, their exit thrilled locals, Loyalists excepted.

Abigail told John she felt the burden of the British presence merely to be changing location but admitted to being happy that Boston had not been

AMERICAN HISTORY 32 NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART; © SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION BRIDGEMAN IMAGES EVERETT COLLECTION/BRIDGEMAN IMAGES; WORLD HISTORY ARCHIVE/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

Abigail lamented John's chronic absences, estimating they had only been together six years out of a 12-year marriage.

AMHP-230400-ABIGAIL.indd 32 1/9/23 8:37 AM

totally destroyed. The city’s escape exhilarated John, a fiend for independence. On March 29, he wrote to Abigail about his joy at learning Boston was free, even as he moped that he knew few details and so awaited her accounts with “great impatience.” He wanted Boston Harbor made impregnable. Abigail had neither the ability nor the desire to command troops, but John often discussed strategic ideas with her and greatly valued her opinion of them.

Most of the time.

The most famous look into Abigail’s politics arose from Patriot celebrations of the British retreat. Abigail only reminded John that he “Remember the Ladies'' after she had unleashed a condemnation of Virginia. “I have sometimes been ready to think that the passion for liberty cannot be equally strong in the breasts of those who have been accustomed to deprive their fellow creatures of theirs,” she wrote March 31, 1776. “Of this I am certain that it is not founded upon that generous and Christian principle of doing to others as we would that others should do unto us.”

The letter gained fame because in it Abigail forcefully characterizes women’s second-class status in the colonies. Law and custom barred women from owning property and assigned any wages they earned legally to their husbands. “All men would be tyrants if they could,” and if a Declaration of Independence was coming, it would be shrewd not to put all of the power in the hands of one sex, Abigail argued.

She dusted her broadside with drollery. “The ladies,” she said, were prepared “to mount a rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws

Abigail Adams, left, loved her husband, but found irritating his dismissive attitude toward the roles of women, and was not shy about telling him so. The above fan belonged to her.

in which we have no voice, or representation.” The letter also conveyed notes of optimism, originating as it did in one finally assured she could plant seeds on her farm or go for a walk without hearing cannonades.

But that optimism evaporated. John dismissed his wife’s adjuration to “Remember the Ladies.” In an April 14 note, he pooh-poohed Abigail’s thoughts as “saucy”—implying that she was straying from her designated societal role and venturing into arenas she should eschew. John’s shrugging response irked his wife. She wrote to Mercy Otis Warren asking if they should compose another appeal to Congress. Frustrated with John’s lackadaisical mien, she and the family faced a stout new challenge just as the absent man of the house was taking on unprecedented responsibilities in Philadelphia.

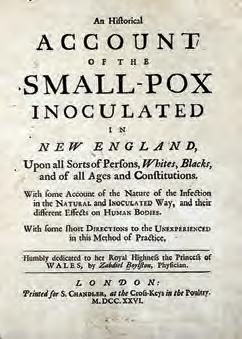

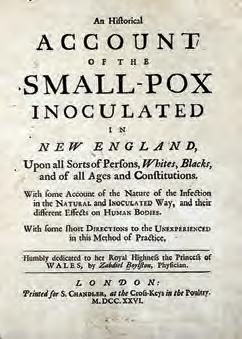

SMALLPOX HAD BEEN BLISTERING indigenes and colonizers in disfiguring, deadly waves around North America since the Europeans first arrived. In 1775-76, British occupiers and Continental Army soldiers besieging them loosed a particularly severe outbreak. Abigail first mentioned the pox in her March 17, 1776, letter to John celebrating the city’s survival. As the British were withdrawing, the port was still battling the latest epidemic. Only the previously infected were even being allowed into town, a category that would have included John Adams, who in 1764 had undergone a controversial procedure— inoculation.

To inoculate against the pox, a doctor opened a small wound and into that cut or scrape inserted matter intentionally tainted with exudate from a person with smallpox. The idea was to trigger a mild case of pox from which the recipient emerged in a few weeks enjoying lifelong immunity, as occurred with survivors of full-on cases

SPRING 2023 33

NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART; © SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION BRIDGEMAN IMAGES EVERETT COLLECTION/BRIDGEMAN IMAGES; WORLD HISTORY ARCHIVE/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

AMHP-230400-ABIGAIL.indd 33 1/9/23 8:38 AM

like George Washington. By summer 1776, inoculation had become en vogue. The “Spirit of Inoculation,” as Abigail labeled it, finally achieved such critical mass that city authorities legalized the procedure.