historic NEw england

From the President

One of the joys of our work at Historic New England are the endless opportunities to learn and discover new stories. This issue of the magazine is no exception. Whether it’s delving into the history of a pair of fabulous yet practical late nineteenth-century winter boots, discovering why the state flag of Hawaii flies outside of Phillips House in Salem, Massachusetts, or the deep importance of shining light on the life of Caesar, an enslaved man who lived at the Sarah Orne Jewett House in South Berwick, Maine, new information is constantly being brought forward and shared across a variety of channels and at our thirty-eight exceptional museums across the region. The work never ceases, which we love, and it’s a delight to be on this journey of discovery together.

In November, the second annual Historic New England Summit provided the setting to learn from some of the leading voices in the fields of inclusive design, placemaking, education, housing equity, diverse landscapes, and many more. Over 630 participants, both in person and Livestream, took part in these conversations, bringing their voices, experiences, and insights to the table. Recordings of each session from the two-day convening are now available to view on our website, and I encourage you to discover, or revisit, these thought-provoking and inspiring discussions online and in this issue.

On the following pages, you’ll also find an exciting preview of the upcoming exhibition opening this June at the Eustis Estate. In The Importance of Being Furnished: Four Bachelors at Home, curator R. Tripp Evans shares his research on four homes and their creators. We can’t wait for you to learn about these extraordinary individuals, designers, and tastemakers.

It is a privilege to be surrounded by so many incredible voices and resources, and we are grateful for your contributions to this shared knowledge and your enthusiasm for the rich mission of our organization. As we learn, we adapt, and as we adapt, our horizons expand. We hope this issue inspires further exploration into the work Historic New England is engaged in across the region and beyond.

With gratitude,

Vin Cipolla President and CEO

HISTORIC NEW ENGLAND magazine is a benefit of membership. To become a member, visit HistoricNewEngland.org or call 617-994-5910. Comments? Email Info@HistoricNewEngland.org. Historic New England is funded in part by the Massachusetts Cultural Council.

President and CEO: Vin Cipolla Interim Editor: Laura Sullivan Editorial Review Team: Alissa Butler, Study Center Manager; Lorna Condon, Senior Curator of Library and Archives; Erica Lome, Curator Design: Julie Kelly Design

TAKEAWAYS

from the Historic New England Summit

by KATHERINE POMPLUN Institutional Giving Officer for Preservation at Historic New England

The second annual Historic New England Summit, held November 2 and 3, 2023, attracted more than 630 participants via Livestream and in person in Providence, Rhode Island. The audience represented more than 200 organizations with a shared passion for preservation and improving the communities they serve. Here are takeaways from some of the outstanding leading voices who took the Summit stage.

Susan D. Whiting

Susan D. Whiting

Be Local, Think Bigger: A Call to Action

Reflecting on decades of leadership in the corporate and nonprofit worlds, Susan D. Whiting, chair of the National Women’s History Museum, opened the Summit with a discussion of the rapid technological changes that have impacted how cultural institutions deliver on their missions, engage with their audiences, and build communities of support. “The shift from place-based things – things you do in a physical location – to a more virtual world has been very significant,” she said, describing her work with the National Women’s History Museum – an online museum that honors women’s contributions to American history by partnering with other organizations to host virtual and physical exhibitions and public programs. Whiting challenged the audience to envision their own organizations as conduits for ideas that can resonate beyond traditional boundaries.

Meaningful Approaches to Access

Betty Siegel, director of the Office of Accessibility and VSA at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, engaged a dynamic panel in exploring the transformative potential of inclusive design. “We’ve been thinking about accessibility through the wrong lens,” she said, urging attendees to understand that universal design principles seek to address inherent problems within our society and our built environment – not within individuals who are disabled.

“The goal is to find things that facilitate not just getting in the door, but experience,” said Valerie Fletcher, executive director of the Institute for Human Centered Design. “We need to

preserve our historic built environment… it nurtures our souls. But it’s got to work for everyone. It is just not okay if that element of delight in our lives is lost to people who can’t get in.”

Heidi Swevens, director of community partnerships at Inclusive Arts Vermont, described her experience as a legally blind person engaging with an inclusively designed arts exhibit for the first time as transformative, “because I was so used to spending energy making sure that my access needs were met so I could participate in the world.” The feeling of being free to enjoy the experience inspired her to create spaces “where people can come as they are, where disability and access are ordinary.”

Charles G. Baldwin, access and inclusion program officer at the Mass Cultural Council, emphasized the idea of budgets as a moral compass. “If you haven’t budgeted intentionally for inclusion, then you’re intentionally leaving people out.”

The Summit also explored themes of access to shared and public landscapes. Thomas Woltz, principal and owner of Nelson Byrd Woltz Landscape Architects, argued that cultural landscapes contribute to a sense of identity and belonging. He introduced research-driven design practices that reveal the stories of a landscape and enable individuals to make personal connections to a shared space. Woltz urged attendees to "eliminate from our collective vocabulary words like open space, empty space, green space" and recognize that the "land is full" of stories of people and cultures responding to "ecosystems over time.”

Institutions, Trust, and the Future of Cities

Elected officials, cultural leaders, and university presidents all took to the Summit stage to reflect on their work to address the urgent challenges facing cities across New England and beyond.

Memphis River Parks Partnership CEO Carol Coletta and City of Providence Mayor Brett P. Smiley discussed livability and quality of place through the lens

of opportunities and accomplishments in the Summit’s host city. In Providence, city leaders are working to maintain the delicate balance between safeguarding the city's character and fostering its growth while implementing a nationally recognized climate justice plan, incorporating neighborhood voices, and advocating for housing and innovative transit solutions.

Providence’s strong sense of place “includes and is intricately linked to our historic building stock,” said Smiley, but it also extends beyond the built environment “to the intangibles of interconnectedness.” He identified the city’s arts and cultural institutions as essential assets that make Providence a place people want to live. But supporting the arts is not only about facilitating shared experiences and strengthening community pride. “There is an equally compelling case,” he argued, “from a purely economic standpoint, that the arts and the humanities are critical to the workforce of tomorrow.” Introducing students to theater, music, and literature can spark their curiosity, “and it’s how we broaden their lens to become the problem-solvers of tomorrow.”

Smiley’s impassioned support of the arts and humanities paralleled ideas shared earlier in the day by David Leonard, president of the Boston Public Library, in his keynote address on the evolving concept – and relevance – of the public library.

Leonard described today’s “loud library” as an institution that connects to history but provides a modern approach to the information needs of our population. This mission is reflected in both the library’s

architecture and its initiatives, and the emphasis throughout is on access – to welcoming spaces, to opportunities for civic engagement, to technology, and to the world of ideas. The library’s collection of almost 23 million items provides incredible opportunities to glean modern insights from historical perspectives, and “must not only be preserved but activated and brought to life for today’s population.”

Boston Public Library has taken innovative steps to ensure that contemporary challenges do not limit free access to knowledge. As a partner in the Books Unbanned initiative, the library grants digital access to students affected by book bans, regardless of their geographical location. “We can be at the same time contemporary and historical, and we must not squander the trust that libraries engender and that the public has in our institutions.”

Dr. David Fithian, president of Clark University, and Dr. Joanne Berger-Sweeney, president of Trinity College, echoed the importance of trust in their conversation about strategies and partnerships higher education institutions can pursue to strengthen their communities and create educational opportunities. Berger-Sweeney emphasized that “what we do is supposed to make society better,” and building trust between communities and institutions hinges on an institution’s ability to demonstrate that value.

Fithian described a growing commitment at Clark University to offering tuition-free scholarships to academically qualified Worcester residents. Trinity College has developed partnerships with neighboring institutions to convert a vacant bus depot into the “Learning Corridor” – an educational complex adjacent to Trinity’s Hartford campus that serves more than 1,000 students in preschool through Grade 12.

Affordable Housing and Historic Preservation

Communities of all sizes and demographics are confronted with extreme housing shortages and the need to address historic patterns of housing inequity.

Angela D. Brooks, director of the Illinois Office of the Corporation for Supportive Housing and president of the American Planning Association, moderated a panel on inclusive development and opened with a pointed question: “Can the preservation community, instead of being viewed as a hindrance to affordable housing, be seen as a partner in providing solutions?”

Rosanne Haggerty, president and CEO of Community Solutions, reflected on the accomplishments of the Built for Zero campaign, a comprehensive, community-based approach to end homelessness. “The preservation community is needed at that community table, in this community process.” She called for the restoration and revival of historically important forms of housing, “because we need more ways of using the infrastructure we have, of densifying neighborhoods, [and] of creating a variety of housing types so that more people’s housing needs can be met.”

Carrie Zaslow, executive director of the Providence Revolving Fund, described the success and continued evolution of her organization’s Neighborhood Loan Fund, a long-standing program that provides property owners in Providence historic districts with lowinterest home repair loans. “What we are finding more and more is that there are homeowners who are on tremendously fixed incomes,” who struggle to maintain their historic homes or rental units but are unable to take on the cost of a loan. The Providence Revolving Fund worked with other community partners

to develop a program that offers grants – not loans – to homeowners in exchange for placing affordable housing deed restrictions on their rental units. “It’s creating affordable housing in historic homes,” Zaslow noted, “and it’s helping that homeowner create household wealth for their family.”

Sarah Marchant, the New Hampshire Community Loan Fund's chief of staff and vice president of ROC-NH, shared examples from the Granite State, including a Nashua project that converted a vacant historic school building into a shelter, apartments, and a community center. The project raised $9 million in donations and leveraged federal and state tax credit and grant opportunities – but the catalyst for the project was the Nashua Soup Kitchen & Shelter’s successful effort to obtain a 100-year lease for the building at $1 dollar per year. “I think the story for all [of these examples] is these are all community projects, and none of them would have happened without partnerships. That’s the only way we get affordable housing done.”

Cultural Leadership and Climate Action

Miranda Massie, director and founder of the Climate Museum, spoke about her organization’s mission to harness the power of arts and culture to expedite a cultural shift toward meaningful climate dialogue and action. The need to do so, she advised, “could not possibly be more urgent,” as the climate crisis threatens our safety and exacerbates existing social inequities. A summer day in New York City provides startling evidence of this: in historically redlined neighborhoods, where a lack of shade trees is indicative of decades of disinvestment, the temperature of the sidewalk can be thirty degrees hotter than it is only ten blocks away.

Massie explained that our cultural reticence to engage in conversations about the climate stems from a widely held misperception that most Americans don’t support aggressive climate action. "A bipartisan supermajority of adults supports very, very ambitious action for climate justice and for clean energy,” she said, and “museums and other cultural sector institutions have an incredible power to invite people into taking action together.”

Discover More

You can engage with Summit content year-round. Visit summit.historicnewengland.org for 2022 and 2023 session recordings and information on the 2024 Summit.

PRESERVING the Ingredients of Boston's Culinary History

by DR. MICHELLE TOLINI FINAMOREMichelle Tolini Finamore is a fashion and design historian, author and curator, and exhibition and programming consultant.

In 1935, a festive dinner was held at Boston’s Copley Plaza to celebrate renowned baseball player and Red Sox Manager Joe Cronin. For the evening, Chef de Cuisine Carlo Tolini devised a menu that included a martini cocktail, mock turtle soup English style, filet mignon au Madère, olivette potatoes, new peas au beurre, and a fresh strawberry bombe for dessert. The elaborate multicourse meal was standard fare for special occasions at one of the fanciest hotels in town. The whimsical menu, printed locally by the Washington Press on Dover Street, was in the shape of a baseball and featured a separate paper baseball bat with the “batting order” for the evening’s speakers.

This menu is part of a culinary archive that resided for decades in Carlo’s son Romeo’s basement in Quincy, Massachusetts. The collection of menus,

photographs, and culinary organization ephemera interweaves narratives related to Italian immigration, French gastronomy, and the history of Boston’s Copley Plaza hotel, which hosted famous meals and culinary expositions throughout the twentieth century. The Tolini Family Culinary Archive was recently donated to Historic New England’s Library and Archives.

The contents of Romeo’s cellar stretched across four generations of Italian family chefs and was literally crammed with almost a century’s worth of culinary memorabilia. The walls were covered with framed black and white photographs of towering and fantastical creations crafted by family members for culinary competitions between the 1930s and 1970s. Drawers held large collections of chocolate and ice cream molds and countless menus from the Epicurean Club of Boston and Les Amis d’Escoffier Society gatherings. It appears that Carlo saved almost every menu from his thirty-five years as chef at the Copley Plaza, both the everyday service as well as the special occasion meals such as the Red Sox dinner. Reading through the menus is a trip through food history with dishes that range from nineteenth-century holdovers like terrapin soup and green turtle Amontillado to the more familiar lobster salad and baked halibut steak.

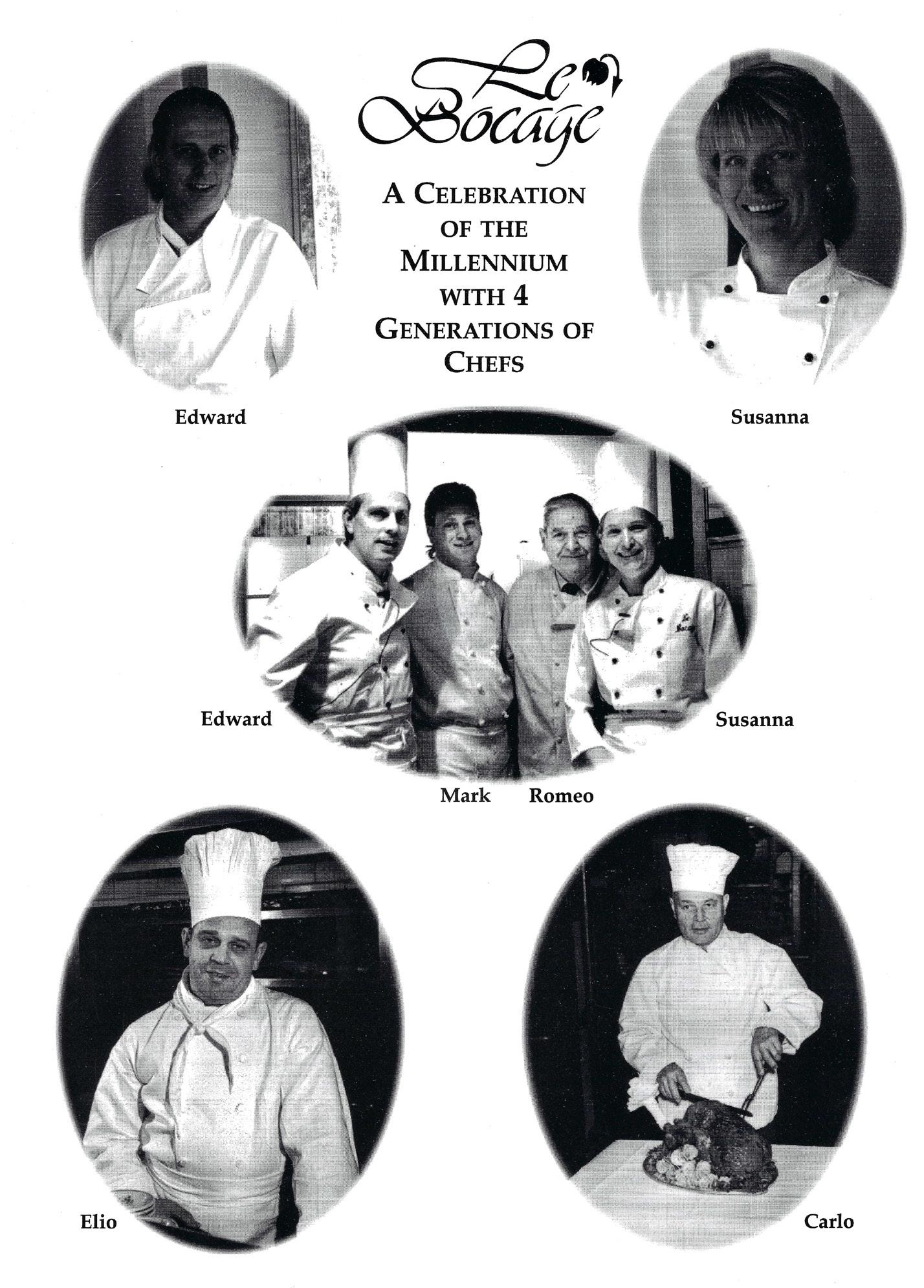

The story of the archive begins with Carlo Tolini, a seventeen-year-old immigrant who came to America in 1904 from Cardana di Besozzo in northern Italy. Carlo settled in Roxbury, Massachusetts, and married Ida Gazzola in 1913. Although trained as a bricklayer, Carlo found his calling in the culinary world, initially working at the Dreyfus Hotel in Boston and then at the Copley Plaza, where he trained as the assistant to chef de cuisine, Jean Jeton. Carlo eventually took over as head chef and his tenure at the Copley Plaza profoundly affected the lives of his sons, grandsons, and great-grandson. As is typical of immigrant families (and at a time when professional culinary education was not the norm), Carlo’s sons Romeo and Elio started their chef training with their father at the Copley Plaza. Romeo’s son Edward went on to study at Newbury College, and he and his wife, Susanna Harwell, headed the Watertown, Massachusetts, French restaurant Le Bocage for nine years; his son

Mark still works in the food industry. This culinary lineage also impacted the rest of the extended family, many of whom are passionate cooks, and who have fond memories of Romeo’s elaborate multicourse meals created for the holiday gatherings in his and his wife, Eva’s, Quincy home.

Menus

The vast menu collection ranges from the 1920s through the 1980s and documents graphic design history, captures seminal moments in local and global history, and traces gastronomic trends. On a local level, the archive includes New England-oriented menus for dinners commemorating events such as Harvard/Yale football games and dinners attended by the long-serving Boston mayor and Massachusetts governor James Michael Curley, whose name appears on countless programs. On a national level, one of the earliest menus in the collection is from the 1927/28 New Year’s celebration at the Copley Plaza, which noted guests would enjoy “dancing until midnight” but, in the midst of Prohibition, requested that they “refrain from violating the 18th amendment.”

World War II’s food restrictions had a marked impact, even in such a high-end hotel, with menus typically including notes regarding the butter shortage as well as specifying that the amount of butter fat could not exceed nineteen percent. All hotels in Boston stopped serving butter after 11 a.m. on weekdays and noon on the weekends and no rationed meats were served on Friday and Sunday. The Copley Plaza kitchen also made it clear that they did not tolerate “any dealings with the black market.”

In addition to the everyday menus and special holiday meals, business gatherings and banquets regularly occurred at the Copley Plaza, including the Jeweler’s Association, the Hotel Association, and a special seventieth anniversary meeting of the New England Shoe and Leather Association. In 1939, more than 150 attendees representing shoe manufacturers, tanning and leather companies, and machinery companies enjoyed pineapple surprise, puree St. Germain, filet of lemon sole, and mignardises (bitesized desserts). Many of the menus were specially designed to reflect the gathering; this one is modest in size but has a faux animal hide cover. Not surprisingly, the vast number of shoe-related businesses in attendance were Massachusetts firms, with Haverhill especially well-represented, and the listing provides a snapshot of the industry at that moment in time.

Not all the gatherings, however, served fancy French meals, nor were they all sober affairs. The Boston Hotel Association’s 1930s circus-themed meetings included homestyle food such as fish stew, kidney pie, ice cream, hot dogs, hamburgers, lemonade,

peanuts, and popcorn. For the 1939 “Big Top” meeting, the hotel group hired equestrians, aerialists, ground tumblers, and clowns from Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus to entertain the crowd.

Culinary Competitions

Ephemera and photographs related to the culinary organizations to which all the family members belonged make up a large part of the archive. The Epicurean Club of Boston and Vicinity, incorporated in 1894, is the oldest professional chef organization in the country. Carlo was a board member of the Epicurean Club as well as a charter member of Les Amis d’Escoffier. The Epicurean Club held its grander affairs at the Copley Plaza, but its smaller gatherings took place all over the city, including at the Harvard Club, the MIT Club, Parker House, and in the North End’s Polcari’s and The European, where the club members dined on pizza and tripe.

The club’s annual culinary expositions were an important part of their mission and the meetings featured elaborate feasts as well as competitions that allowed members to show off their culinary prowess and their artistic skill. Carlo, Elio, and Romeo always participated in these competitions and were often the creators of prizewinning entries. In 1935, Carlo was awarded a first prize for a display called La Tonnelle des Roses. Typically, the work was titled in French, and the rose arbor with wax flowers was suspended over an equally ornate display of tallow bowls in the shape of stylized artichokes, surmounted by (edible) towers of artfully arranged langoustines, crayfish, asparagus, and other foodstuffs. All of the dishes were shiny with the requisite aspic covering. The creation was described in one newspaper as “A Triumph in Culinary Art” that was “so magnificently carried out one would almost believe Mother Nature was the originator, not the chef at the Copley Plaza.”

These displays entailed months of preparation time, and Romeo involved all of his sons, including Charles, Richard, and Edward. All three have vivid memories of the vast amount of work required to get ready for the competitions and even after months of preparation, holding all-nighters before the event. Looking at the photographs of these submissions, it is clear they were labors of love. The sculptural and architectural (and inedible) tallow centerpieces were constructed with

one-of-a-kind plaster of Paris molds created and sometimes carved by Romeo, and the intricate surface decoration consisted of delicately sliced and artfully arranged truffles and elegant chocolate and olive oil tracery. Many of these displays featured New England subjects and landmarks, including the Gloucester Fisherman’s Memorial and the Bunker Hill Monument. There is one intriguing photograph of a sugar “painting” of the now defunct NECCO candy factory in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Romeo’s father, Carlo, was a twenty-time award winner at the Culinary Arts Salon in Boston, and in 1963, Romeo was awarded first prize for the sixth time. Edward was the recipient of numerous awards, as well,

once for a striking display featuring an impressive three-foot-tall sugar model of his Coast Guard training ship Eagle when he was still in the service. The grand displays were on the wane by the late 1960s. Much like the terrapin and turtle dealers that appeared in Epicurean Club program books in the early twentieth century, the tallow distributors start to disappear at the same time.

The competition displays were meant to last only a few days, after which time they would start to melt and smell, even with the addition of peppermint oil to offset the stench.

Other cultural and social changes are represented in the archive, notably the increased participation of women in the culinary world. In 1959, a movement was afoot to form a women’s chapter of Les Amis d’Escoffier. Romeo, as secretary of the Boston group, sent numerous letters in the early 1960s to the New York headquarters advocating for this change. The New York director wrote that they were “happy Boston has taken such an initiative” and Les Dames des Ami d’Escoffier, the first professional women’s association of chefs, was eventually officially sanctioned and continues to exist today.

The photographs in the Tolini Family Culinary Archive capture a passing moment in culinary history, just as the countless menus document one fleeting meal. But they were preserved, and obviously valued, by these chefs. With Historic New England’s acquisition of the archive, what was once ephemeral will now enter into the historic record.

William Sumner Appleton first worked on Jackson House, in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and its eighteenth and nineteenth century additions in the 1930s.

Adapting Preservation for the Future

by BENJAMIN HAAVIK Team Leader for Property CareThe Historic New England Preservation Philosophy – our overall approach to the care of landscapes, buildings, and objects – has been a cornerstone of the organization since its 1910 establishment. Founder William Sumner Appleton is widely recognized as the first professional preservationist in the United States and his approach continues to shape how we think about our work today. In Appleton’s time, preservation of the resource was the ultimate goal. Today, we are equally concerned with making sites accessible to all and addressing climate change – ideas that would have had little purchase when Appleton was alive.

Several of the preservation approaches Appleton developed for the physical care of our historic buildings are still in use today. One is the importance of respecting change over time. In the early twentieth century, it was a common practice to treat a building’s initial construction phase as the most precious and historic. The usual approach was to strip the later layers off a structure so they didn’t interfere with the interpretation of those earlier times. Appleton, while no stranger to this approach early in his career, realized that buildings did indeed evolve, and that change was not inherently in conflict with preserving and presenting the properties.

In 1930, when Appleton was asked why he left later additions on buildings, he said of Jackson House (c. 1644) in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, “The house is one of those best left showing the course of its evolution.” Appleton understood that the authenticity of the site was more about the layers of change than the original build. Similarly, in 1924, when Appleton was resisting a recommendation to remove the later addition of a beehive oven to the great stone chimney mass at Arnold House (c. 1693), in Lincoln, Rhode Island, he promoted a “thoroughly conservative” approach, saying, “What is left today can be changed tomorrow, whereas what is removed today can perhaps never be put back.” Once you remove something like a beehive oven from a building, it is very difficult to replace it authentically.

Appleton appreciated the value of maintenance and took a conservative approach to repair over restoration. When referring to work done on the Coffin House (c. 1654), in Newbury, Massachusetts, in 1930, he noted, “The more I work on these old houses the more I feel that the less of W. S. Appleton I put into them, the better it is.” In other words, the less we repair or intervene in a building the more authentic it remains.

Replacing materials in kind is another widelyheld tenet of historic preservation that has roots in Appleton’s philosophy. “If you take out a piece of wood that was 6x6, let’s put back a piece that is the same; and if it should be hemlock, let’s use hemlock over again, or white pine, or oak, or whatever the case may be…,” Appleton wrote in 1942 of work underway

at Arnold House. “It’s the idea of continuing the original work as closely as possible in reconstruction and repair.” Today, when making a repair at Historic New England, we think about matching materials, dimensions of the material, colors, distinguishing marks, and many other categories depending on the feature being repaired.

Appleton valued the pure preservation of the resources over adaptation, so he was not particularly interested in altering historic houses for modern use. He hesitantly introduced new services, such as electrical and plumbing, with the understanding that they could be invasive to the building. The caretakers who lived in Boardman House (c. 1692) in Saugus, Massachusetts, for example, used an outhouse until the 1950s when the decision was made, after Appleton’s death, that perhaps the caretakers deserved some level of modern convenience. In several circumstances auxiliary structures were modified or even brought to sites for caretaker use rather than making an intervention on primary structures.

Appleton’s resistance to permanent change influenced the preservation concept of reversibility – any upgrades or repairs we make to buildings should be able to be easily undone in the future. While reversibility wasn’t a term Appleton used, the idea certainly grew from seeds he sowed. Changes to servants’ quarters and work areas such as kitchens are classic examples. The history of house museums is filled with stories of renovations to these back-ofhouse operations on the assumption that no one would be interested in them.

Today, Historic New England visitors appreciate our light touch over the years. The reversibility of our interventions allows many of our spaces to be interpreted with a high level of authenticity. For example, Historic New England added a visitor center to Gropius House (1938) in Lincoln, Massachusetts, in the 1990s. Housed within the historic Walter Gropiusdesigned two-car garage, the visitor center is what we call a “box-within-a-box,” a free-standing structure that can be dismantled and removed in the future without damage to the historic garage.

Over the years we have been faced with myriad issues that Appleton never had to grapple with. We

now know that once-ubiquitous materials such as lead paint and asbestos are health hazards – including the siding we removed from Pierce House (1683) in Dorchester, Massachusetts, in the early 2000s. More recently, climate change has led us to reevaluate our preservation approaches at our historic sites. While maintenance is still our preferred option for retaining historic material, we know many of our gutter systems cannot handle the high volume of water they are now forced to manage in intense storms. If we don’t change the gutter size, we place the buildings at higher risk for water damage. Therefore, replacing gutters or other building and landscape features in kind is no longer the default preservation approach it used to be. To ensure historic resources survive for future generations, we must change our thinking.

The effort to make our sites inclusive and available to all also challenges aspects of traditional preservation philosophy. We want to preserve and share our resources and we are adapting our preservation approaches to allow for changes in how to access the sites. Adding ramps, chair lifts, railings, and widening

door frames is necessary for accessibility, even if it involves the loss of historic material or changes to the aesthetics of a site. One of the major criteria when evaluating these changes is the reversibility of the intervention, and we try to find a middle ground that balances unprecedented access with historic and aesthetic considerations.

The work we do today to make our sites more inclusive, accessible, and resilient takes time and thought. Preservation needs to evolve and change to fit the times. We must ensure we are preserving for the right reasons. We look carefully at each intervention to determine the impact to the resource from the preservation and aesthetic perspectives, consider its reversibility, and assess the positive impact we might have on the resource by making a change. At Historic New England, our preservation philosophy will continue to evolve to better protect and share our important resources.

left The visitor center at Gropius House in Lincoln, Massachusetts, is a purpose-built structure within the historic Gropius two-car garage. This “box-within-a-box” can be removed if we ever want to re-interpret the garage in the future. right As part of the Save America’s Treasures exterior preservation and resiliency project for Hamilton House in South Berwick, Maine, copper gutters were upsized to increase their carrying capacity during intense rain storms.

Partnering in Trades Training

to Build a Foundation for the Future

by JANINA PEPPERS Senior Manager for Historic Preservationat the Student Conservation Association, with contributions from 2023 Massachusetts Historic Preservation Corps members Sierra Baker and Thomas Bray

Historic preservation projects often require an intricate web of relationships to be successful. The training program Historic New England and the Massachusetts Historic Preservation Corps run together is no exception. What began as a request from Historic Preservation Corps to Historic New England for a preservation carpenter to facilitate a training in 2021 has blossomed into a partnership from which both organizations benefit. The Campaign for Historic Trades has identified the lack of skilled preservation trades practitioners as one of the most pressing issues for the field. Historic New England and the Massachusetts Historic Preservation Corps are working together to address the need to train skilled tradespeople to do preservation work.

Each year, Historic Preservation Corps trains a cohort of young adults in carpentry, masonry, window restoration, and other preservation trades. Historic Preservation Corps began as a partnership between the Student Conservation Association and AmeriCorps in 2017 and has grown into a sixteen-person program offering paid training throughout the commonwealth. Through AmeriCorps, crew members work on projects with Boston National Historical Park, the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation, Historic New England, and the National Park Service. Historic Preservation Corps also contracts directly with non-profits and government agencies to provide services for hire.

During the 2023 Historic Preservation Corps training season, Historic New England’s preservation staff provided two weeks of window restoration training that covered the entire process from sash removal to installation. Trainees also worked on a masonry restoration project at the oldest surviving greenhouse in North America, the Bark Pit Greenhouse (c. 1796) at the Lyman Estate in Waltham, Massachusetts. Historic New England and Historic Preservation Corps engaged masonry and lime mortar experts Fabio Bardini and Blaise Davi to teach the corps members. Bardini led trainings on lime mortar mixes and application techniques. To prepare them for their time with Bardini, Davi taught the crew the basics of historic brick masonry and mortar mixing. Historic Preservation Corps Project Leader Thomas Bray was thrilled to be assigned such a complex project and to learn from well-known experts, noting “the team trained alongside Historic New England’s preservationists to understand the nuances of lime mortar, the place of contemporary materials, and the importance of matching historic mortar to historic brick.”

can within your means are skills needed for any job. I know these lessons will take me far when this program is over.” Other corps members agreed. “Historic New England preservationists hold themselves to a high level and encouraged us to do the same. We set up a clear plan of work and executed it without setbacks,” Bray said. “Even as the crews changed over, the expertise of Historic New England staff and their willingness to work with us aided us in finishing the project on schedule.”

Historic New England benefits from the partnership as much as the corps members. “We’re really excited about our ongoing partnership with the Historic Preservation Corps,” said Team Leader for Property Care Benjamin Haavik. “We not only were able to get much needed preservation work completed on the Bark Pit Greenhouse, but the ability to share our work and potentially inspire the next generation of tradespeople is critical to the future of preservation.”

Working with talented instructors in the field contributed to a successful crew member experience. “What was invaluable was working alongside professionals in historic carpentry and learning what they do on a daily basis,” said corps member Sierra Baker. “Creative problem-solving and doing the best work you

Left page Massachusetts Historic Preservation Corps members try their hands at removing failing lime mortar from the Bark Pit at the Lyman Estate. Removing mortar by hand is an arduous task but ensures clean and precise joints for the next step in the process. Above Crew members pose for a picture with Fabio Bardini, lime masonry expert and trainer, after a successful day of learning about the lime mortar repointing process. Bottom, L-R: Charlie Sykes, Maggie McCormack, Karina Cardenas, Sierra Baker, Fabio Bardini Top, L-R: Ben Lee, Naomi Ingbur, Shealagh Crowley, Thomas Bray

and the BACHELOR Beauty

by R. TRIPP EVANSTripp Evans is a Professor of Art History at Wheaton College in Norton, Massachusetts, where he specializes in American material culture and historic preservation. He is the guest curator of the upcoming exhibition The Importance of Being Furnished: Four Bachelors at Home at the Eustis Estate in Milton, Massachusetts.

This summer Historic New England will invite visitors into the private world of four captivating bachelors – men whose homes defined American style from the Gilded to the Jazz Age, yet whose personal lives have until recently remained mostly in shadow. Opening June 21 at the Eustis Estate in Milton, Massachusetts, The Importance of Being Furnished: Four Bachelors at Home exhibition will examine the foundational role these “bachelor aesthetes” played in early twentiethcentury preservation and interior design, showcasing an extraordinary range of furnishings, design work, and personal artifacts drawn from the men’s own homes.

Spanning the Aesthetic Movement and Colonial Revival periods, these homes – today all public museums – include Pendleton House (1906) at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) Museum in Providence, built to replicate the Federal-era home of gambler-collector-dealer Charles Leonard Pendleton (1846-1904); Historic New England’s Codman Estate (c. 1741) in Lincoln, Massachusetts, home to five generations of the Codman family and redecorated in its final stage by renowned designer Ogden Codman Jr. (1863-1951); Gibson House in Boston’s Back Bay,

an 1860 townhouse preserved by its final occupant, writer Charles Hammond Gibson, Jr. (1874-1954); and Historic New England’s Beauport, the SleeperMcCann House (1907) in Gloucester, Massachusetts, the eclectic masterpiece of interior decorator Henry Davis Sleeper (1878-1934).

Each of these New England designer-collectors came of age when, for the first time in the modern era, the bachelor household had become an aspirational domestic model – a marked shift from the previous generation, which had believed the American home’s highest and even exclusive goal was to support family life. This development not only introduced a wider range of possibilities for non-traditional households, but it also led to a newfound fascination with interior design and individual expression in their own right – a phenomenon clearly seen in the wide range of styles these men adopted, both in their own homes and in others’. All four practiced professional interior decoration, and two in particular – Codman and Sleeper – shaped the emerging field in important ways.

The elevation of the bachelor household may be directly traced to Oscar Wilde. During his extraordinarily popular, year-long American lecture

Page 16 [Maker unknown], Jabot, France (1824). Silk (76” x 63 1/4”). One of a set of curtains and matching seating upholstery ordered by Charles Russell Codman from Paris in 1824. Museum Purchase with funds provided by a friend of Historic New England. Below Portrait of Charles Leonard Pendleton (c. 1861). Ambrotype with hand tinting (1 7/8” x 1 3/8”). Gift of Fred Stewart Greene, 04.1466. Courtesy RISD Museum, Providence, Rhode Island. top right China, Qing Dynasty (1636-1911). Vase, 1700s. Porcelain (12 ½ inches, height). Bequest of Mr. Charles L. Pendleton (04.370). RISD Museum, Providence, Rhode Island.

bottom right Edmund Willson, preliminary sketch for Pendleton House at the Rhode Island School of Design Museum (c. 1904). Watercolor and pencil on paper. RISD Museum Archives, Providence, Rhode Island.

tour in 1882, the writer professed the Aesthetic Movement’s “art-for-art’s-sake” credo, a message that profoundly reshaped the world that Pendleton, Codman, Gibson, and Sleeper later inherited. Insisting that artistic creativity should be divorced from moral purpose, Wilde claimed that beauty constituted an end unto itself. Translated to the realm of domestic design (Wilde’s most frequently delivered lecture in 1882 was “The House Beautiful”), this message sought to replace

the home’s traditional aims – to nurture children and inculcate Christian virtue – with the presumably higher calling of individual artistic expression.

Addressing “the youth of the land,” a constituency that included neither women nor married men, Wilde proclaimed, “The passion for beauty engendered by the decorative arts will be to them more satisfying than any political or religious enthusiasm, any enthusiasm for humanity, any ecstasy or sorrow for love.” Not

only was marriage non-essential to domestic style, Wilde’s argument ran, but it might even present an impediment. Homemaking, it appeared, was better suited to the single man of means, a figure who could collect, design, and entertain unencumbered by the demands of family life. Addressing both its married and unmarried readership, the popular Munsey’s magazine declared in 1899 that “the bachelor… has become master of the comforts and luxuries of a home of his own, with all the resources of capital and science to minister to his every need.”

Pendleton, Codman, Gibson, and Sleeper were the very men Wilde had in mind: acolytes of beauty whose collections, homes, and even whose very persons exemplified his decree that “the secret of life is art.”

In assembling his unparalleled collection of

7/8” x 66 1/4” x 2 1/4”). Gift of Stephen Sleeper. top right Mourning scene (1825-1835). Felt, silk, watercolor, printed paper, and hairwork (6 1/4” x 7 1/4” x 3/4”). Gift of Constance McCann Betts, Helena Woolworth Guest, and Frasier W. McCann. bottom William Ellis Ranken, Painting of the Octagon Room at Beauport. Watercolor (25” x 33 1/2” x 7/8”). Gift of Constance McCann Betts, Helena Woolworth Guest, and Frasier W. McCann.

eighteenth-century Chippendale furniture, the reclusive Pendleton lived for visual perfection not only at the cost of his “enthusiasm for humanity,” to use Wilde’s phrase, but even sometimes at the expense of the works’ authenticity. Visitors to the exhibition will see examples of Pendleton’s extraordinary Chippendale collection alongside reproductions the dealer passed off as the genuine article, and even a monumental combination of both – a piece that served, appropriately enough, as the head of Pendleton’s deathbed. By recreating a tableau of Pendleton’s now-vanished private interiors, moreover, this exhibition will consider their translation to the “period rooms” of Pendleton House, a curatorial practice first introduced when this wing opened in 1906. By presenting these museum rooms as the fictional home of an eighteenth-century gentleman avatar, the collector managed to erase his own murky past as a high-stakes gambler and sometimes dubious dealer.

Codman was himself so enamored of eighteenthcentury style, beginning with his ancestral Lincoln

home, that he codified its principles in the authoritative 1897 treatise he co-authored with Edith Wharton, The Decoration of Houses. Drawn both to Yankee simplicity and Continental excess, Codman developed his successful decorating style by reconciling these seemingly opposing approaches; though generally conservative in his approach, he insisted that any false element in decoration (a faux finish, a dummy window) was acceptable as long as it provided visual pleasure. Through a wide collection of furnishings, plans, and personal materials from the Codman Estate and Historic New England’s Codman Family Papers, visitors to the exhibition will learn how the renowned designer’s family home served as his first design laboratory, emotional touchstone, and primary legacy and also how the opposing figures of his patrician and rakish ancestors informed his signature style.

For Gibson, no beauty matched his own gilded youth and poetic voice, and so he arrested these forever in his family’s Back Bay home, oblivious to his own aging body and the vicissitudes of literary and decorating taste. Beginning in 1936, when he formalized the scheme for his house-museum, Gibson

created a kind of installation piece with himself as its primary exhibit. Until his death in 1954 he faithfully preserved the interiors of 137 Beacon Street, last decorated by his mother in the 1890s; he wrote countless unpublished sonnets in a romantic, Victorian mode; and when he received visitors, he dressed like a Boston “Brahmin” of the late nineteenth century. Using letters, manuscripts, furnishings, and the home’s ubiquitous examples of Gibson’s own youthful image, the exhibition will reveal the man as a kind of historical manifestation of Wilde’s Dorian Gray.

At Beauport, one of the best known of Historic New England’s properties – and certainly, one of the most widely published houses in America –Sleeper orchestrated beauty in a surprising range of forms. Using color, line, scale, pattern, and visual humor, he disregarded historical accuracy to achieve powerful visual effects. At the Eustis Estate galleries the nature of these strategies will be distilled to a dazzling collection of Beauport artifacts; even those familiar with the house will see new juxtapositions that illuminate Sleeper’s decorating strategies, and important objects that, given the house’s wonderfully

distracting variety, have sometimes been overlooked. Here, too, visitors will consider the personal connections that drove Beauport’s development, a circle that included collector Isabella Stewart Gardner, painter Cecilia Beaux, and the dashing financial scholar and politician, A. Piatt Andrew, Beauport’s primary muse.

The Importance of Being Furnished: Four Bachelors at Home presents a unique opportunity to see the New England home in a new context. Many of the Historic New England artifacts on display have never been seen outside their properties or the Historic New England archives, and none of the loan objects from RISD or the Gibson House Museum have traveled before. Together, this constellation of works will illuminate an underexamined story in the history of American interior design, all within the walls of a historic home that is, itself, an important example of Aesthetic Movement design. Wilde himself could not have chosen a more appropriate venue.

Historic New England’s exhibition The Importance of Being Furnished: Four Bachelors at Home is drawn from R. Tripp Evans’s book of the same title, a fullcolor examination of the four homes and their creators that publisher Rowman and Littlefield will release in June 2024. Please consider supporting this captivating exhibition which will be free to members. The public can enjoy the exhibition with admission to the Eustis Estate. Special related programs and tours also will be available. Large exhibitions are not possible without support from members and friends. To learn more and make a gift, visit www.HistoricNewEngland.org/Furnished or send your gift to The Development Office, Historic New England, 151 Essex Street, Haverhill, MA 01832

The Red Study at 137 Beacon Street (The Gibson House Museum). Photograph by John Woolf. Courtesy Gibson House Museum, Boston, Massachusetts.

A Prolific New England Architect: Explore the New Online Catalogue of William Ralph Emerson’s Works

This winter we introduce a new interactive feature on our website centered on the work of renowned New England architect William Ralph Emerson (1833-1917). The online database is searchable and includes information on all of Emerson’s known commissions, including those that are no longer standing and those that were never constructed. Visitors can browse or search these commissions by date, city, street, building type, or client and see a range of materials from photographs of extant buildings, to archival images from late nineteenth-century magazines, to original architectural designs. Accompanying the database is a web app with images and biographical essays celebrating the many facets of Emerson, who also was an accomplished artist, poet, lecturer, and writer. Emerson (cousin of philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson) was a prominent and highly sought-after architect who had hundreds of commissions during

his lifetime. He designed a variety of buildings from government facilities to country estates, but is bestknown for his Shingle style residential architecture. His style became popular with the monied elite in the late 1800s, including renowned landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted.

The database and web app result from years of meticulous research conducted by architectural historians Cynthia Zaitzevsky, Roger Reed, and particularly 2021-22 Historic New England Research Fellow David W. Granston III. Granston’s fellowship research documented close to five hundred Emerson commissions, including four hundred previously undocumented commissions that Granston uncovered. The material these researchers assembled, along with their understanding of Emerson’s life and work, has made it possible for Historic New England to share this collection for exploration and enjoyment.

Shoe

by NORA ELLEN CARLESON Associate Curator of CollectionsStories “

To walk a mile in someone else’s shoes.

I wouldn’t want to be in their shoes.

Waiting for the other shoe to drop.

If the shoe fits.

How many times have you heard these phrases? Have you ever wondered why the English language has so many shoe-related idioms? Whether you give them much thought or none at all, in the United States, shoes are central to our daily activities. They are both personal and universal. They shape to our feet as we wear them, becoming an extension of our bodies. Many of us appreciate the beauty and pleasure of a good shoe. Shoes protect us, help us perform everything from walking a dog to breaking an Olympic record, and provide clues about our jobs, tastes, hobbies, and styles.

At Historic New England, we collect and share stories of New Englanders’ lives through places, documents, photographs, and objects. Often, the items that comprise our collection reveal unexpected stories. With more than five hundred pairs of shoes in our collection, Historic New England has a lot of shoe stories to share.

Cobbling Together a New Country

When Winthrop Gray decided to follow in the footsteps of his father and brothers and become a shoemaker in the Massachusetts Colony, it is unlikely he imagined his work would be in a museum nearly 250 years later. A pair of Gray’s stunning shoes provide a window into a story with a surprising twist. Gray was part of the growing shoemaking industry in the colonies which, by the 1760s, rivaled producers in England and France in terms of quality of material and craftsmanship. The label affixed to the sole of one of Gray’s shoes signals the level of professionalization of the Massachusetts shoe industry in the eighteenth century and places Gray’s shop in Boston on the eve of war.

Created at some point between 1765 and 1775, these shoes might be one of the last pairs the talented shoemaker made. In 1775, Gray shuttered his shop to join the Continental Army, never to return. But that is not where his story ends. Unlike many of his peers tragically lost to war, Gray never returned to shoemaking seemingly because he didn’t want to. After a public falling out with Paul Revere and coming into an inheritance, Gray left the army and lived out his remaining days as a tavern owner – a surprising twist on the familiar tale of a heroic artisan turned American revolutionary.

The DIY “Dupe”

Many of us can relate to wanting something we cannot afford. Sometimes we save up to purchase our heart’s desire. Other times we make do, retrofitting something we already have or making our own. People in the past also turned to what we now call DIY to achieve style on a budget. A pair of ladies’ winter boots from the late nineteenth century tells us a story of someone who wanted a pair of stylish winter overshoes but did not have the means to purchase such a luxury.

The maker likely hoped these boots would be a proxy for the popular, lush carriage boots made of velvet, silk ribbons, and fur over a hard rubber overshoe – which also are represented in Historic New England’s collection. To make the boots, the crafty DIY-er took some Wale Goodyear Shoe Company bottoms, also known as “rubbers,” hand knitted a top, added some ribbon closures, and secured the top to the rubber with glue. While the final product didn’t quite replicate the desired carriage boot, to modern eyes the rubber-bottomed boot with a light brown upper resembles the L.L. Bean duck boot or the “Bean boot.” And though the Bean boot is now quintessentially New England, Historic New England’s DIY carriage boot “dupe” was made at least twenty years before Leon Leonwood Bean got his feet wet while hunting in Maine and created his namesake boot.

Shoes Fit for a Flapper

Picture it: the roaring twenties. A tuxedoed band plays the latest jazz hit. Young couples take to the dance floor and kick up their feet. Women are bedecked head to toe in sparkle and shine to catch the lights as they move their bodies to the beat. One woman wears a loosefitting, knee-length flapper dress - showing off not just her legs but a beautiful pair of cream floral brocade heels with metallic thread and rhinestone buckles. As the newest dance craze, the Charleston, begins to play, the young woman doesn’t fear losing her shoes because she is wearing the fashionable and secure “t-strap” style of the day.

Even though shoes help us navigate the world, we may not think about how shoe styles change to reflect new ways our bodies may move. In the 1920s, as women were liberated from their corsets, long gowns, and the slow motions of the waltz, they began to show off their legs and new dance moves. The evening slippers and heels of decades past were now accidents waiting to happen. Without a strap to secure a shoe to a woman’s foot, popular dance moves might cause her shoes to fly off her feet. Shoes needed to fit the times and the “t-strap” was invented. Shoes like these in Historic New England’s collection help us tell stories about women finding liberation by moving their bodies in new ways and the fashion industry responding with new designs.

Beguiling Bronze Booties

Once a decorative staple in many American homes, the bronzed baby shoe has become an item of curiosity, fading fast from our collective memory. Personal

belongings like a 1940s bronzed baby shoe help us tell the stories of New Englanders through the family heirlooms with which they decorated their homes.

Humans have known how to bronze objects for more than five thousand years, but bronzing baby shoes didn’t become popular in the United States until the 1930s. Violet Shinbach’s Ohio-based American Bronzing Company was not the first to bronze baby shoes, but it deserves credit for successfully marketing them as the ultimate keepsake. Some sources claim that by the 1970s, Shinbach’s company was bronzing upward of 2,000 shoes a day – more than 500,000 shoes a year. By the 1990s, with the onset of the digital age and a wider variety of childhood mementos, fewer and fewer baby shoes were bronzed. The American Bronzing Company closed its doors in 2018. Preserved in our collection as a piece of cultural history and not just as a family keepsake, the bronzed bootie prompts us to consider how everyday items become cherished possessions.

Introducing Loio Kuhina of Salem

by ABIGAIL STEWART with AMI MULLIGANAbigail Stewart is the North Shore Regional Site Administrator at Historic New England. Ami Mulligan is a PhD student in the History Department at the University of Hawai'i at Manoa.

When Phillips House in Salem, Massachusetts, is open to visitors, above the front door flies a flag that at first glance is often mistaken for an American flag or the Union Jack. It is, instead, the state flag of Hawaii. Upon entering the house visitors encounter objects from Hawaii and other Pacific islands. These items don’t seem to fit within the Colonial Revival backdrop of the rooms and the belongings of five generations of the Phillips family. However, looking into the Phillips family history reveals a connection to the Pacific Islands that began in the middle of the nineteenth century.

Stephen Henry Phillips, father of the last owner of the house, held the role of loio kuhina, or attorney general, to King Kamehameha V. This connection is always mentioned on tours as an interesting side note, but has never been fully explored. Historic New England turned to Ami Mulligan, a historian of Hawaii, who researched Stephen Phillips’s role in the Hawaiian government and the Phillips family’s connection to Hawaii. Mulligan’s research provided a clearer picture of Phillips’s responsibilities and a deeper understanding of the family’s connection to the fiftieth state.

Stephen Henry Phillips was born in Salem in 1823, the eldest son of a privileged New England family. After studying law at Harvard, he served as a district

attorney in Essex County, Massachusetts, and as Attorney General of Massachusetts from 1858 to 1861. He arrived in Honolulu on September 12, 1866, at the invitation of King Kamehameha V, to take up his post as loio kuhina.

But why Phillips? He had not previously been to Hawaii, nor did he have a family connection. However, his close friend and Harvard Law School classmate, William Little Lee, had been tapped by the Hawaiian government to work on the newly instituted judicial system for the Governor of Oahu. This system adopted a number of positions and processes from the Massachusetts court system, which tied the commonwealth’s law practices to the Kanaka Maoli (Native Hawaiian) judicial system. Lee held many important positions within the Hawaiian government and helped to establish laws under kings Kamehameha III and Kamehameha IV. Phillips’s friendship with Lee led to his eventual invitation to join the Hawaiian government under their new king. In an article about his appointment in The New York Times, Phillips was

characterized as being “firm in his convictions, but conciliatory in his deportment [while] striv[ing] to harmonize differences while maintaining the honor and dignity of the State.”

Phillips joined the government at a turbulent time for Hawaii’s monarchy. Between 1820 and 1848, the Boston-headquartered American Board of Commissioners of Foreign Missions (ABCFM) sent twelve companies of Protestant missionaries to Hawaii to preach the gospel. Over nearly three decades, the ali’i (Hawaiian chiefs) and the missionaries became increasingly intertwined

in their public and private lives as advisors, business associates, neighbors, and even friends. A number of Kanaka Maoli, including ali’i like Kamehameha V and his predecessor, felt that some of the missionaries and a number of their American associates had gained too much power in the Hawaiian government.

Upon his ascension to the throne, Kamehameha V did not hold a public coronation and refused to uphold the Constitution of 1852, which he felt deprived the monarchy of its power. He instead sought to restore the monarchy’s position by holding a Constitutional Convention in 1864 to institute the monarchy as the central authority. The new constitution strengthened the monarchy, promoted Hawaiian commercial interests, and encouraged Kanaka

Maoli culture and practices.

It was in this environment that Phillips began his tenure as loio kuhina. Kamehameha V’s primary concern was to strengthen Kanaka Maoli governance and cultural structures, so it was imperative to select someone who would commit themselves to the same. Phillips acted as an agent of the king’s new government. He appeared on behalf of the Crown in criminal and civil cases, was “vigilant and active in detecting offenders against the laws,” and enforced all “bonds or other obligations in favor of the government.” These terms were set out by “An Act Defining the Duties of the Attorney General,” which were written under Kamehameha V’s new constitution from 1866 to 1867. Phillips was called upon to give his legal opinions to the government

and became a member of the king’s cabinet. Phillips also filled a number of interim positions, including Kuhina Waiwai (Minister of Finance), Kuhina o Na Aina E (Minster of Foreign Affairs), and was a member of the Papa Ee Moku (Board of Immigration). It was also during this time that he returned to Massachusetts to marry Margaret Duncan. The couple returned to Hawaii and had their first son, Stephen Willard Phillips, in 1873.

The month before the Phillipses’ baby arrived, Kamehameha V died without appointing an heir, and a new monarch, William Charles Lunalilo, ascended to the Hawaiian throne via election. Phillips resigned his post the next day, after which he relocated to San Francisco where he practiced law for the Equitable Life Insurance Company and the California state board of railroad commissioners. In 1881, he moved back to his

home state of Massachusetts. While Stephen Henry Phillips spent less than a decade in Hawaii, his work helped to strengthen the Hawaiian government in the face of rapidly expanding pressure from American influences. He served his post dutifully and was held in high regard by the king. Hawaii’s monarchy would eventually fall to external forces, with the Bayonet Constitution in 1887, annexation by the United States the following year, and eventual statehood in 1959.

Stephen Willard Phillips spent an even briefer time in Hawaii as an infant, but filled his Chestnut Street home with objects that reflected his affinity for his birthplace and the Pacific Islands. He amassed his own “Hawaiian library” and worked closely with what would become the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem and the Bishop Museum in Honolulu to refine their Pacific Islands collections. Ami Mulligan’s work has brought a deeper understanding of the family’s connection to Hawaii and we are excited to bring these stories to our visitors.

CAESAR’S Stories

by SCOT MCFARLANEScot McFarlane is a researcher for the American Historical Association’s Mapping the Landscape of Secondary Education project and founder of the Oxbow History Company. He is a former Historic New England Recovering New England’s Voices research scholar.

In the late 1700s, an enslaved man named Caesar labored and lived at what is now called Sarah Orne Jewett House in South Berwick, Maine. Built in 1774, the house is named after the author who called it home for most of her life from 1849 to 1909. But for Caesar, who predated Jewett by more than half a century, it was a site of labor rather than a home. Like many people who were enslaved, what little we know about him comes from just a few documents. In Tilly Haggens’s 1777 will, he left his son John, the original owner of Jewett House, some tracts of land, a mill and mill privileges, and “also that negro Boy he now has with him, Caesar by name.” There also is evidence that Caesar may have stayed in the house long after the Revolution, maybe into the nineteenth century. Two documents point to this possibility: the 1790 and 1800 censuses, in which the Haggens household lists one person under the “all other persons” category used to categorize non-white, free people.

During the year I worked as a Historic New England Recovering New England’s Voices scholar, I focused in large part on the stories of enslaved people like Caesar. A network of researchers has learned so much about the history of slavery in Maine, including a number of people enslaved in Berwick where Jewett House is located (the area became South Berwick in 1814). Recovering the stories of enslaved people is very challenging; details of their lives were rarely recorded or saved. In my own research I have seen how evidence related to the history of slavery has been purposefully destroyed, making it even more difficult and requiring

us to consider different approaches that move beyond archives to recover more of Caesar’s story.

In contrast with Caesar, Sarah Orne Jewett’s life is well documented. Sarah’s grandfather Captain Theodore F. Jewett, a merchant and ship owner, moved his family from Portsmouth, New Hampshire, to the Haggens house in the 1820s. It appears that the Jewett family rented the house for a number of years, finally purchasing it in 1839. In 1848, Captain Jewett’s son, Dr. Theodore Herman Jewett, his wife Caroline, and their baby daughter Mary moved into the house. Sarah was born in 1849 and the young family continued to live with Captain Jewett until 1854, when a Greek Revival house was built next door for their use.

Sarah’s life in the house and Caesar’s life there were separated by only one generation. Sarah wrote fiction, but first she listened to other people’s stories. It is likely that she heard Caesar’s story and shared a part of his history with her readers.

Sarah built her stories from her lived experience and

her awareness of local history. When she described her novels Deephaven and The Tory Lover, she said they “hold all my knowledge, real knowledge, and all my dreams about my dear Berwick.” In particular, The Tory Lover relies on real historical characters set in the time of the Revolution. Several historically accurate names of local Berwick characters are included — Tilly Haggens, the father of the first owner of Jewett House, is named in the book, and so is Caesar. This suggests Sarah must have at least known his name, but it begs the question of what else did she know?

In The Tory Lover she places Caesar in the nearby Hamilton House rather than her own home. Yet one other detail suggests that Sarah may have carried over more than his name in this novel. Near the beginning of the book she writes: “Caesar, who had been born a Guinea prince, drank in silence, stepped back to his place behind his master, and stood there like a king.”

Members of West African royalty did become ensnared in the slave trade in this period. For example, Randy J. Sparks’s The Two Princes of Calabar: An Eighteenth-Century Atlantic Odyssey describes the true story of how the Robin John brothers, themselves slave traders, became enslaved in North America. Thanks to the research of Patricia Wall, who studied slavery in Berwick and Kittery, Maine, in her book Lives of Consequence, we also know a more specific fact related to Sarah’s description of Caesar. The year before Tilly Haggens willed Caesar to his son John, he placed a runaway advertisement for one of his enslaved men named Newport. The ad included this description: “is scar’d in his temples which was done in Guinea.”

This detail about the Haggens family’s ownership of at least one enslaved man born in Guinea suggests that Sarah’s specific presentation of Caesar as a real historical figure went beyond his name.

Sarah Orne Jewett did not tell her readers when her fiction derived from history and thus far none of her letters tell us what she did know about the history of slavery in Berwick. These mysteries also serve as a reminder of the limitations of history. We cannot rely on primary sources alone to understand the history of slavery in New England.

Literature can help to fill in some of the gaps of records right up to our present moment. Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved addresses these omissions directly. She wrote the novel in part because she “was keenly aware of erasures and absences and silences in the written history available to me — silences that I took for censure… To me the enforced or chosen silence, the way history was written, controlled and shaped the national discourse.” As Morrison wrote, in order to learn from the past, sometimes it must be imagined. To be clear, Sarah Orne Jewett’s descriptions of Caesar lack the depth and agency that Morrison used to correct both the historical record and a literature of either flatness or caricature.

Scholarly historical monographs cannot fill in the holes with the imaginary, and historians such as Harvard University professor Tiya Miles also publish works of historical fiction. Their deep knowledge of historical context allows them to create an accurate world in which they can explore how their characters might have felt and acted. We know Caesar labored as an enslaved man at Jewett House in the 1770s. He might have been born in Guinea before surviving the Middle Passage, and after he obtained, or perhaps regained, his freedom he may have continued to work at Jewett House into the early 1800s. The recorded history of slavery in New England often preserved only the first names of enslaved people such as Ceasar, and historically-informed literary treatments offer another way to consider the stories we cannot recover through archival research alone.

SET APART: The Carr Family at Casey Farm

by JANE HENNEDY, Site Manager for Southern Rhode IslandHenry Carr and his wife, whose name has yet to be recovered, were free African Americans employed at Casey Farm in North Kingstown, Rhode Island, in the early nineteenth century. Between 1804 and 1810 –during an economic depression, and in period where even free Blacks did not have equal rights under the law – the Carrs were tenant farmers. The Carrs lived roughly a half mile from the core of the farm, but their story is now central to our interpretation of farm life thanks to a new exhibition in the Casey farmhouse museum gallery.

Over three centuries, the Caseys employed indentured servants, paid laborers, renters, tenant farmers, and at least fourteen enslaved people to keep their farm and other properties profitable. Most of these workers lived near the family, who kept careful records of their workers and enterprises. From Silas Casey’s records, we know that in 1804, Carr’s yearly compensation was $80 ($2,000 today), plus an acre likely for a garden, pastureland for two hogs and one cow, corn, and use of the “small house.” Casey noted tasks performed by hired hands, likely including Carr— animal care, pressing cider, breaking flax, growing grain, and making cheese, an activity that probably involved Mrs. Carr.

Prior to 1775, Rhode Island had the largest percentage of enslaved people in any northern colony. Some of its residents participated in the kidnap and sale of Indigenous and African people, and others benefited from an economy based on forced labor. Slavery became less economically advantageous in the North after the American Revolution, and Rhode Island passed a gradual emancipation act in 1784. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, most Black people in Rhode Island were legally free. As Christy Clark-Pujara writes in Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island, however, “free was a terribly relative term.”

Among the recovered archaeological fragments from the tenant house at Casey Farm were ceramic shards reflecting the diversity of utilitarian and decorative wares used by the Carr family. Selected fragments, coupled with other materials such as glass and bone, provide a rare glimpse into the life of an African American household in early nineteenth-century Rhode Island.

Even in such a difficult social and political climate, Black Rhode Islanders forged community bonds. Carr, for example, took part in Negro Election Day, a day each summer when enslaved and free Black people gathered to socialize and elect community leaders in an era when most were denied voting rights. Carr participated even though his white employer attempted to control him by docking his pay and isolating him from the farm and his neighbors.

Documents can only tell us so much. No mention of the Carr family or the small house in which they lived appears in records after Silas Casey’s death in 1814, when his son leased the Casey family’s house to white tenants. In the mid-1990s, a field school through Rhode Island College conducted an archaeological dig near the small house at Casey Farm under the direction of Boston University graduate student Ann-Eliza Lewis. It was not the easiest dig; in the 1970s, the Navy Seabees bulldozed fire breaks across the property, and they jumbled the site of the small house. Nevertheless, Lewis and her team recovered, identified, and stored fragmented household objects. Small items such as chalk, combs, thimbles, and a teapot and cups showed that the Carrs purchased non-essential items and engaged in leisure activities.

More than two centuries after the Carr family left Casey Farm, archival, archaeological, and curatorial research has brought their family’s story back to the property. Their former homesite is now part of a conserved woodland with walking trails.

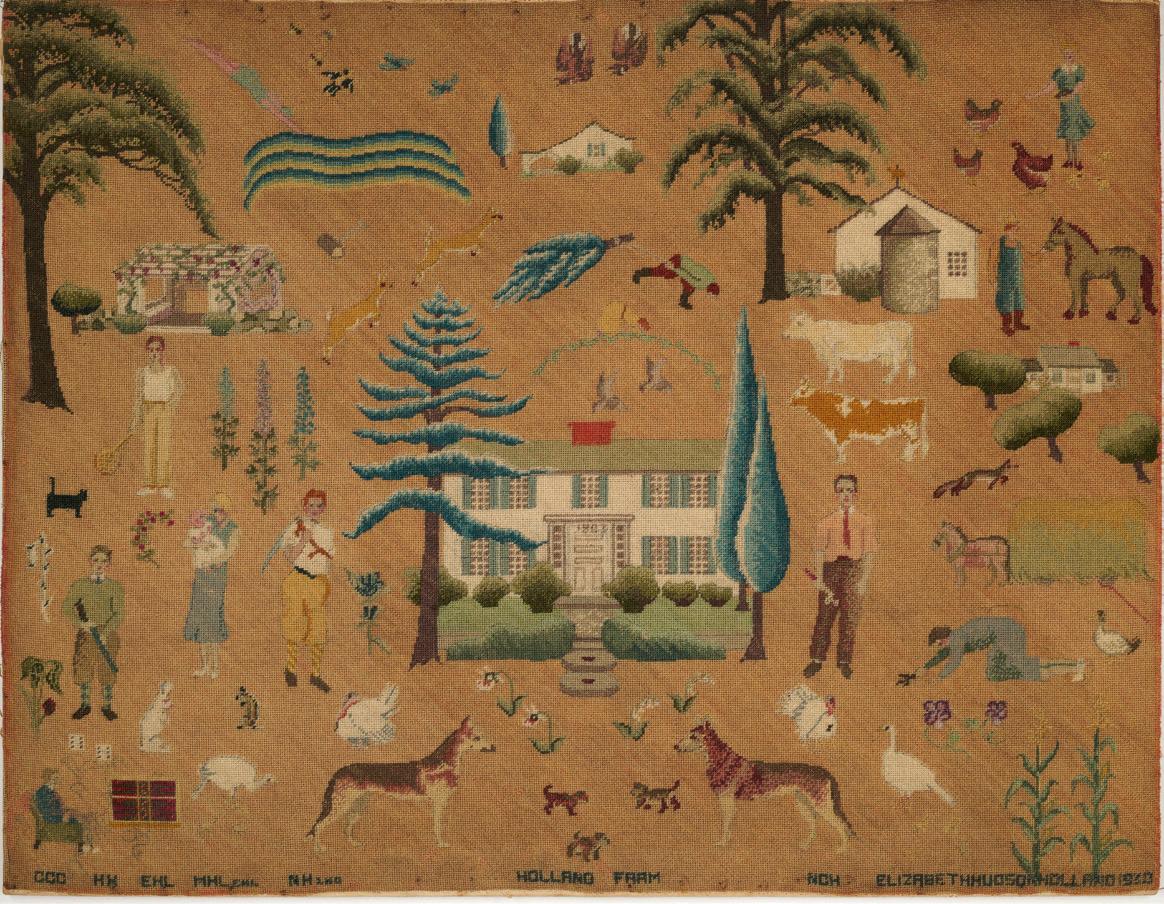

Remembering the Family Farm in Needlepoint

by ERICA LOME, CuratorIn 1930, Elizabeth Hudson Holland (1878-1954) created a large needlepoint picture featuring three generations of her family at Holland Farm, their country home in Belchertown, Massachusetts. Some members are shown hunting and gardening, others play tennis and golf. A woman in a blue dress feeds the chickens while farm workers tend to horses and cattle. The 200-acre farm is alive with birds, rabbits, deer, and family pets, who – along with the human inhabitants – are placed against an empty background, appearing as whimsical vignettes drawn from Elizabeth’s memories of long summer days and cozy winter nights.

The Holland Farm was built in 1802 by an ancestor and stayed in the family with the exception of one generation. Nelson Clarke Holland and Elizabeth Hudson Holland bought the farm back in the early twentieth century and split their time between Belchertown and New York City. By 1930, the family made several additions to the property, such as extensive flower and vegetable gardens, a putting green, tennis court, and swimming pool with pool house. The family sold the farm in the late 1970s.

Much like the farm itself, Elizabeth’s needlepoint picture is a blend of tradition and expansion, with a modern sensibility informed by its lively cast of characters. Its unique charm and storytelling potential make it a fabulous addition to Historic New England’s collection.