Winter already and what a year we’ve had. It has been wonderful to welcome you to our properties once again and share a range of experiences and events.

September brought great sadness as we marked the passing of HM Queen Elizabeth. On page 4, we remember her strong links with our work and properties, and reflect on our role in paying tribute to her life.

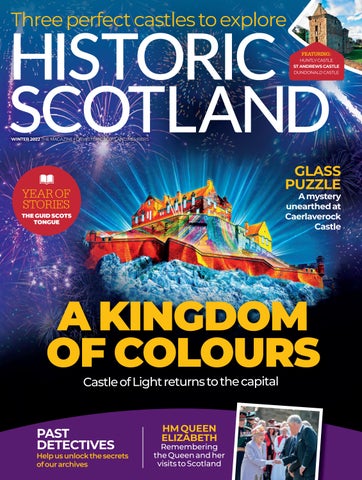

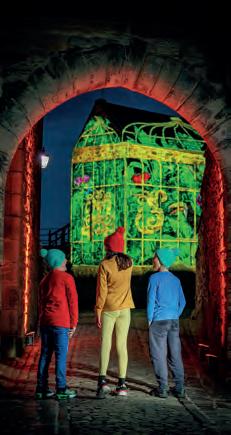

Bringing light to the darkness this season is our spectacular Castle of Light event at Edinburgh Castle, which promises to be more colourful than ever. You’ll find more details on page 52.

We also have a feast of fortresses for you to explore by daylight, including Dundonald Castle in the south west (page 26) and Huntly Castle in the north east (page 34).

As Scotland’s Year of Stories concludes, Ashley Douglas celebrates the Scots language on page 18, and we speak to Carnegie Medal-winning author Theresa Breslin about the historical figures and places that inspire her (page 6).

You can start your festive shopping early on page 48 then treat yourself to a very special Christmas lunch or afternoon tea – see our event listings on page 52.

Talking Scots (page 18)

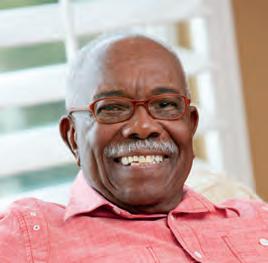

Ashley is a multilingual researcher, writer and translator specialising in Scots research, writing and translation

I’ve never been to … Huntly Castle (page 34)

Freelance journalist Joan writes regularly for The Guardian, The Telegraph, The Times and The Herald

Eternal enigma (page 42)

Award-winning freelance journalist

Susan is a columnist and arts writer for The Herald

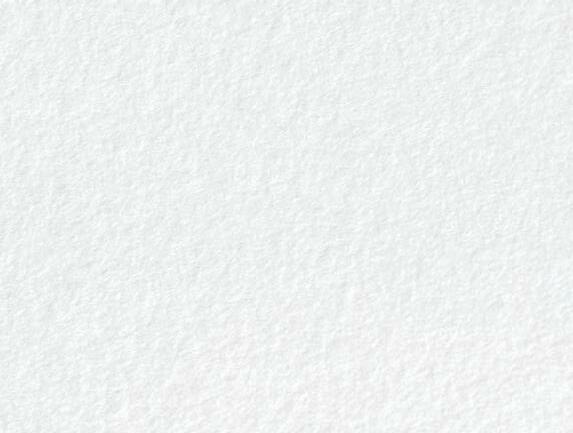

Vivid depictions of Scotland’s history can bring it to life in front of our eyes, for children and adults alike. Liza Tretyakova’s illustrations of legendary kings and queens do just that on page 6.

Historic

Historic

a

(HES)

Historic Scotland magazine is also available as an accessible PDF. Please log in to our website at historicenvironment.scot/member to download your copy, or contact the membership team on 0131 668 8999 and they will be happy to help.

Thousands of people visited St Giles’ Cathedral in Edinburgh to pay their final respects to HM Queen Elizabeth, following her death at Balmoral in September.

Before the Queen’s cortege arrived in the capital, our Collections Team was engaged in preparing the Crown of Scotland, which was placed on the Queen’s coffin while it lay at rest.

Kathy Richmond, Head of Collections

& Applied Conservation, says: “We were honoured to play a key role in the ongoing story of the Crown and its continuing significance in Scotland.”

The oak catafalque, or plinth, for the coffin was crafted by our joiner Adrian Ferguson at St Anne’s Maltings workshop near the Palace of Holyroodhouse.

David Storrar, Head of Edinburgh Region, says: “It was fitting that the team which serves the Palace and Edinburgh Castle provided the catafalque for the Queen’s coffin.

“We also built the steps used by the Duke of Hamilton to place the Crown on the coffin during the Thanksgiving Service. It has been a source of immense pride for everyone involved.”

HM Queen Elizabeth’s fondness for Scotland was well documented and she visited our historic properties many times during her 70-year reign

“It was fitting that the team which serves the Palace and Edinburgh Castle provided the catafalque for the Queen’s coffin”

Clockwise from left: Kathy Richmond, Head of Collections & Applied Conservation, with the Crown of Scotland, the centrepiece of the Honours of Scotland; HM Queen Elizabeth visits the Scottish National War Memorial at Edinburgh Castle in 2014; the Queen at

the official reopening of Stirling Castle’s refurbished royal palace apartments in 2011; a walkabout after the reopening; the Duke of Hamilton carries the Crown of Scotland during the Thanksgiving Service at St Giles’ Cathedral in September

Mary, Queen of Scots and her mother, Mary of Guise, in flight

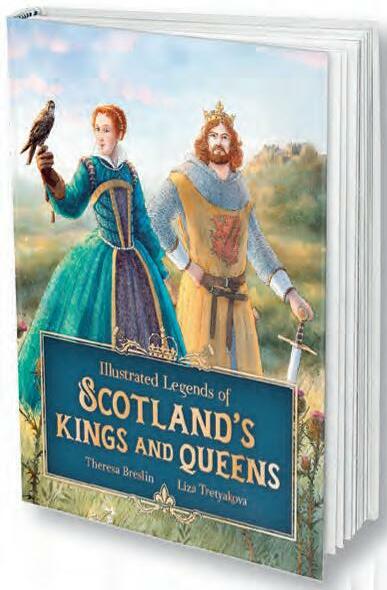

An impressively illustrated children’s anthology charts the remarkable stories of Scotland’s most revered royalty

Secret plots, fierce battles, and striking properties lie at the heart of a brand-new book, IllustratedLegendsofScotland’s KingsandQueens

Penned by Carnegie Award-winning children’s author Theresa Breslin OBE, it brings together the legacies of 10 of Scotland’s most significant kings and queens with Liza Tretyakova’s stunning illustrations.

Each of Breslin’s stories is inspired by historical sources and ancient lore, from rescuing the Stone of Destiny with Scotland’s first king, Kenneth MacAlpin, and battling at Bannockburn with Robert Bruce, to making friends with young Mary, Queen of Scots and braving a would-be assassin with Queen Victoria. This unique anthology brings the vibrant tales of these fascinating characters to life and offers vivid glimpses of Scotland emerging as a young nation.

Fancy curling up with a good book this winter? Then grab a copy for yourself or even as a present for a loved one this Christmas.

Visit stor.scot and enjoy a 20% member discount. See page 50 for the discount code

Below: King William in battle, one of the monarchs in Theresa Breslin’s new book (shown right)

Kenneth MacAlpin is credited as the first king to envisage the land of the Scots that would become Scotland. His actions, and those of the monarchs who came after, had huge influence over Scotland’s physical and cultural development.

Their achievements include the founding of such abbeys as Dunfermline and Arbroath, the establishment of an early parliament, the compilation of the Declaration of Arbroath, Edinburgh’s world-famous Royal College of Surgeons, a printing press, and a mint.

My husband and I have been members of Historic Scotland for many years and regularly visit the properties featured in Illustrated Legends of Scotland’s Kings and Queens that have connections to Scotland’s sovereignty.

Edinburgh Castle (James IV) is the jewel in Scotland’s crown and handy for a wander around Holyrood Abbey and Park. Stirling Castle (Robert I) is a favourite and every time I visit I find something new. I love visits to Dunfermline Abbey too (Mary, Queen of Scots).

In the book Robert I is so clever and dashing, and Mary, Queen of Scots is an utterly delightful child, so it’s really hard to choose my favourite featured royal. I’ve always admired James IV and am now a teeny bit in love with his sensitive, intelligent face as captured in Liza’s illustrations. His contribution to the improvement of surgical skills in Scotland cannot be overestimated.

Historic Scotland staff are always unfailingly pleasant and helpful. When visiting Dunfermline Abbey, they told me Queen Margaret’s original tomb wasn’t there as her body was exhumed centuries prior and parts of her sent abroad!

My research suggests that Iona Abbey may be the burial place of MacBeth. I also learned that Queen Gruoch, Lady MacBeth, and King MacBeth were good monarchs who ruled for 17 years.

Theresa is taking part in Tales from the Castle at Stirling Castle this November. See page 52 for more details

Theresa Breslin OBE reveals how Historic Scotland properties have given her insight and inspiration

Winter can be a tough season for wildlife, with freezing temperatures and reduced daylight making each day a challenge. Hibernation is a solution for some. Migration is the best plan for others.

One of my favourite winter visitors is the barnacle goose. Small and sociable, barnacles – or barnies – are very distinctive, with their creamy white face and belly setting off a predominantly black and grey body.

As autumn turns to winter, these geese arrive on British

Barnacle geese begin courting each other by leaping, flapping their wings and vocalising together.

shores. Their sudden reappearance was a mystery to our forebears, who coined some remarkable theories and myths to explain their summer absence.

As nobody had ever seen a barnacle goose nest, eggs or chicks, word spread in the 11th century that the birds hatched from goose barnacles. These crustaceans live attached to rocks, ships and driftwood, and occasionally wash up along the coast in large numbers. Their black and white colours match the geese, and some people even claimed to have witnessed the birds emerging from the barnacles!

Another popular explanation was that these geese grew as fruit on waterside trees. It was thought that this unusual tree could be found in Orkney, and, once ripe, the fruit would fall into the water, come to life and surface as a goose.

Both myths persisted for centuries in medieval Britain. So much so that barnacle geese were commonly eaten on Fridays and during Lent. Irish clergy believed the geese to be fruit or fish, allowing their consumption as they were not “born of the flesh”.

Mythology aside, we know today that the barnies undertake an impressive migration to Britain. After breeding in places such as Greenland and Svalbard,

Norway, they travel 2,000 miles to seek a milder winter than that offered by the Arctic islands. The oldest ever recorded barnacle goose was at least 30 years old, meaning it had flown over 120,000 miles in its lifetime.

The entire Svalbard population of barnacle geese return faithfully to the Solway Firth each year. During the 1940s this population was as low as 300. However, conservation efforts have allowed this number to grow to almost 40,000 today.

Situated on the Solway coast, Caerlaverock Castle is surrounded by wetlands, saltmarshes and fields –all ideal habitats for our Arctic visitors. If you’re in the area, make sure to listen out for the geese noisily barking or yapping as they fly over in large flocks, or ‘skeins’.

Gordon Smith is a Ranger at Holyrood Park

We have five copies of Theresa Breslin’s brand new book, Illustrated Legends of Scotland’s Kings and Queens, to give away. To be in with a chance of winning, just answer the following question correctly.

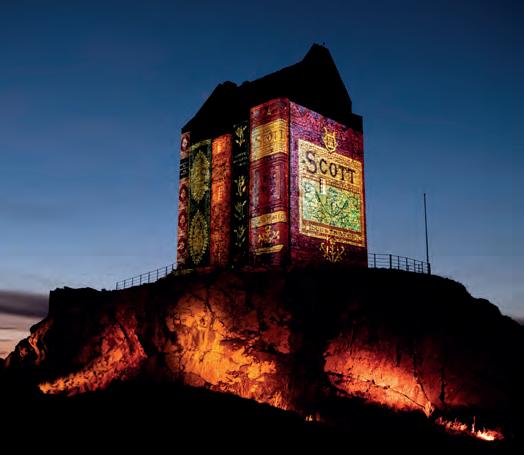

The jewel in Edinburgh’s skyline will sparkle this festive season as our popular Castle of Light event returns for its third year on select dates throughout November and December.

Castle of Light: A Kingdom of Colours –created by a talented team of video animators, composers, voiceover artists, choreographers and 3D artists – will divide Edinburgh Castle into colourful zones, each with something unique and engaging to experience.

Visitors can expect kaleidoscopic projections, seas of twinkling lights and video projections. They can also enjoy the return of the event’s mascot, Rex Rampant, to guide them from the castle’s lowest ward to Crown Square, while illuminating

fascinating stories from Scotland’s history.

As well as an array of tasty treats to tuck into, this year’s event boasts a host of new attractions to explore. From a larger video tunnel at the top of the castle and multicoloured aura lighting installations (ideal locations for snapping

See Edinburgh Castle transformed into an extravaganza of light and sound

selfies) to animations turning the Argyle Tower into a retro 8-bit video game, Castle of Light: A Kingdom of Colours will be a sight to behold.

“This year’s projections include a mix of organic designs depicting stories from Scotland’s past, which will transform the castle with light and sound like never before,” says Kingdom of Colours’ creative director, Andy McGregor.

“We’ve also capped our ticket prices in line with previous years so that as many people as possible can marvel at the wonder of the Castle of Light.”

Last year almost 40,000 people enjoyed this winter wonderland. Grab your tickets and wrap up warm for the perfect way to add that extra touch of magic to your yuletide celebrations.

For tickets, visit castleoflight.scot

Where was Mary, Queen of Scots born? A. Lochleven Castle B. Linlithgow Palace C. Dumbarton Castle

Five lucky winners will each receive a copy of the Illustrated Legends of Scotland’s Kings and Queens anthology, which has been beautifully illustrated throughout by Liza Tretyakova.

For your chance to win, visit hes.scot/membercomp by 9 December 2022 to enter your answer and for more information on terms and conditions. Open to UK residents only.

Last issue’s answer: The Scots word ‘fankle’ means to tangle or confuse.

Alexis McEwan shares her experience as a first-time event volunteer at Linlithgow Palace

I started volunteering at the Engine Shed in Stirling five years ago when looking to fill my free time after winding down at work.

I’ve been a Historic Scotland member for years, so volunteering let me learn more about how this public body works to protect our heritage for future generations.

This summer was my first time being an event volunteer at Linlithgow Palace’s Spectacular Jousting. What I enjoyed most was the chat and meeting new people. It was great seeing everyone enjoying themselves. You

never know the amazing things you’ll learn or see.

To those thinking about volunteering – just go for it!

Spending the day with folk who want to protect and promote our historic sites is really satisfying. Plus, getting involved in events is an easy way of experiencing volunteering if you’re not ready to commit to something regularly.

Our specialist teams have been making great progress surveying the high areas and stonework of 70 properties in our care and establishing how we can protect them against climate change.

The first phase of prioritised inspections is now complete and this has enabled us to reopen Dundonald Castle, Doune Castle and Inchcolm Abbey.

There is increased visitor access at other properties, including St Andrews Castle and Cathedral. The next group of sites is now being inspected, with work scheduled throughout winter. New activities, such as 3D animations, are providing alternative access while work is under way.

For project updates, visit historicenvironment.scot/ inspections

The ghost of Edinburgh Castle and Mary, Queen of Scots’ diary feature in our online exhibition showcasing the fantastic tales submitted by young storytellers to our If These Walls Could Talk project.

The challenge was created with the Scottish Book Trust and the Scottish Storytelling Forum to celebrate Scotland’s Year of Stories 2022.

Whether you’re hunting for your next must-read historical yarn or looking for ideas, visit our online exhibition for a world of inspiration for would-be writers.

See historicenvironment.scot/ young-storytellers

The intriguing ruins of Lincluden Collegiate Church near Dumfries feature some of the best Gothic architecture to be found in Scotland.

The church was established in 1389 by Archibald the Grim, 3rd Earl of Douglas, on the site of a Benedictine nunnery dating from the 1160s.

The nunnery had apparently fallen into disrepute, prompting Archibald to petition the

pope for a change of use. The church was probably designed by the Frenchborn Jean Morow, one of the finest master masons in Scotland.

The church’s choir, south transept and south nave aisle survive along with a range of domestic buildings.

The choir features a stone pulpitum, or screen, decorated with angels, cherubs and scenes from the life of Christ. From 1424

until 1450, Princess Margaret, the 4th Earl of Douglas’s widow, oversaw the church’s final construction phase, including her own tomb.

The Reformation of 1560 saw the church fall out of use. It was entrusted into state care in 1922 under a Guardianship Agreement.

● Lincluden Collegiate Church is open all year round. More details at historicenvironment.scot

LINCLUDEN COLLEGIATE CHURCH

LINCLUDEN COLLEGIATE CHURCH

As well as being keepers of Scotland’s rich past, our historic places often hold fond memories of family and friends. We have recently received several donations in remembrance of loved ones who have passed away.

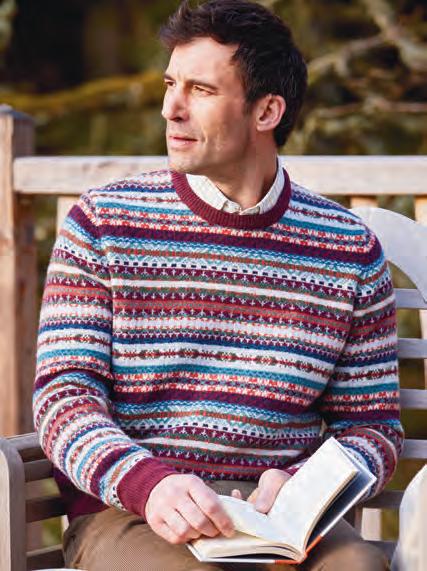

Spotlight on Scott’s connections to the nation’s buildings

The Sir Walter Scott exhibition at John Sinclair House in Edinburgh features drawings, photographs and sketches from our archives that depict the buildings and monuments associated with Scott and his writing.

Taking place as part of the 250th anniversary celebrations of the author’s birth, the exhibition details the homes and historic sites that were important to Scott, and which formed the backdrops to his poems and novels.

Learn more about Scott’s ancestral ties to Smailholm

Tower and Mousa Broch’s role as muse for his 1821 book, The Pirate.

You will also discover alternative designs for Edinburgh’s iconic Scott Monument.

The exhibition runs until Friday 31 March 2023 with free one-hour time slots available to book between 11am and 3pm.

To book email archives@hes.scot

Family and friends of the late Arlene BaronStuart of Aberdeenshire donated to mark her love of her local heritage sites – in particular, Deer Abbey, where her wedding photographs were taken in 2021.

his passion for Scottish history with friends across Scotland and America. Following his sudden passing, his friends were moved to make a donation in his memory. These touching gifts are a reminder of how important the properties in our care are to so many people.

Our heartfelt thanks to those who have generously supported our work as a continuation of their loved one’s passion for Scotland’s heritage.

Brian Maley was a regular visitor to our properties and shared

Keep an eye out for signs of erosion, water damage, vandalism or littering

We’re on the lookout for photographs taken during your trips to our heritage sites as part of the next stage of our conservation citizen science project, Monument Monitor.

Your submissions to Monument Monitor can provide us with important insights into the day-to-day conditions of

our properties in care, help to combat heritage crime and also record the impact of climate change.

Signs at participating sites have information on the type of pictures we’re looking for and how to submit them via email.

Visit historicenvironment.scot/ monument-monitor

A thank you for your donations in memory of loved onesSmailholm Tower –bound up with Sir Walter Scott The much-loved Deer Abbey

Our Archives team is embarking on an exciting project to create a flagship facility in Bonnyrigg for our archives.

At present our archive, which comprises extensive collections of materials, is stored and made available at various properties across Edinburgh and the Lothians.

Some premises fail to meet the standards now required for the care and preservation of historic archive material. It can also be a challenge to provide access for our many users.

With leases on some sites coming to an end, the time was right for creating specialised facilities for a 21st-century audience.

Lesley Ferguson, Head of Archives, explains: “Our collections illustrate and document Scotland’s archaeology, buildings, and maritime and industrial heritage. As an Accredited Archives Service, we’re responsible for keeping them safe to be used by audiences now and in the future.

“We’re transforming an existing building, helpfully already called Archive House. Over the next three years, it will be redeveloped to provide the facilities needed for a modern archive.”

Our archivists and other experts are working closely with a design, engineering and project management team from Oberlanders

Architects, Buro Happold, and Gleeds.

Together they will develop storage premises as well as essential operations, such as conservation, cataloguing and digitisation.

The building will be transformed to meet the highest standards of energy efficiency as part of wider efforts to deliver our Climate Action Plan.

Lesley says: “We’re aiming for ‘passivhaus’, a term referring to buildings with rigorous energy-efficient design

standards, which maintain an almost constant temperature.

“The project will use lowcarbon building materials and methods to create a sustainable building that can be certified under the Scottish Government’s Net Zero Public Sector Buildings Standard.”

Thanks to your eagle eyes, we’ve been able to pinpoint the buildings and locations featured in 2,293 previously unidentified photographs. These images have been added to our online archives, Canmore, as part of a mammoth 170,000image upload of photos documenting life in Scotland during the 1970s and 1980s. The photos were originally part of a Scottish Development Department collection and record rural and urban life in Scotland during these decades. However, we’ve yet to uncover the stories behind the remaining 2,000 photographs – the placenames and properties featured in them remain unnamed. Dust off your detective skills and help us discover the stories, spaces and places linked to these images so we can paint a clearer picture of these chapters in Scottish history.

Get image spotting at canmore.org.uk/ gallery/1096464

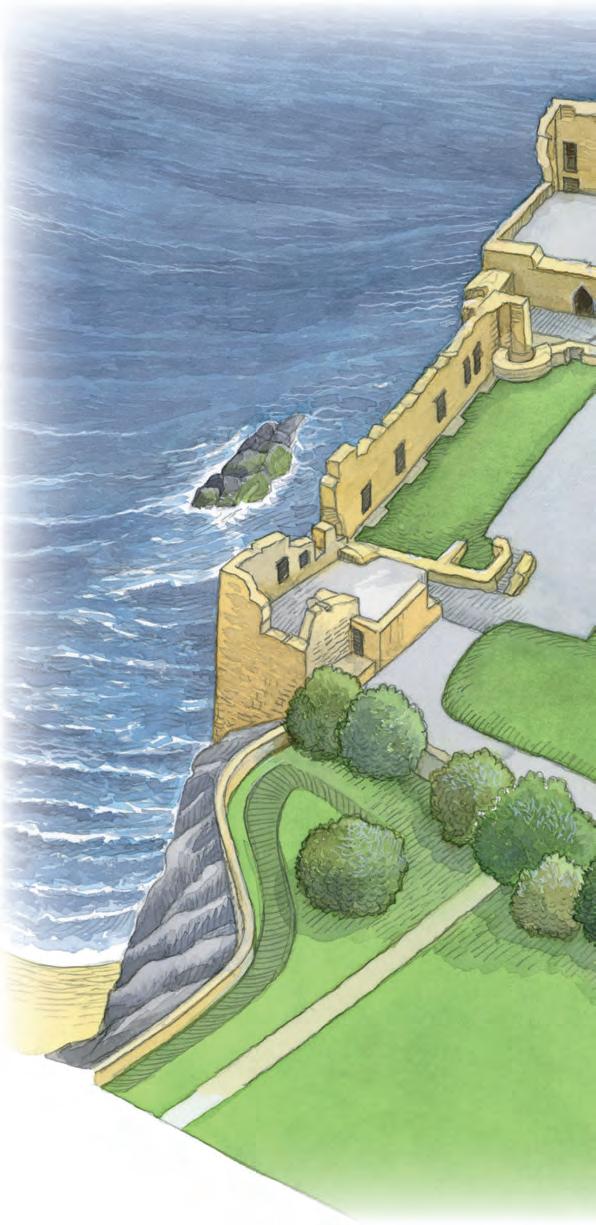

This fortress castle was once threatened by assassins and besieging forces, but today its remnants are at risk from storms and coastal erosion

For 450 years, St Andrews Castle served as a bishop’s palace, fortress and state prison while St Andrews was the hub of Scotland’s religious and academic life.

St Andrews Cathedral was begun around 1160 and the castle, possibly replacing a structure from the 1100s, is thought to have been started around the same time.

The royal burgh had strong links with Scotland’s monarchy and the castle played host to royalty on various occasions. In 1425, James I spent Christmas at the castle, and Mary of Guelders gave birth to James III here in 1452. While the bishops

entertained high-ranking guests from near and far, they also had to be ready to defend the church’s property. However, in 1546 Archbishop Beaton’s assassins managed to gain entry to the castle disguised as masons. They then occupied the castle and Regent Arran ordered his troops to lay siege.

Today, adventurous visitors can explore the mine and countermine dug by the attackers and defenders –a fascinating exemplar of medieval siege engineering.

After the Reformation, the castle remained in use, but by the late 1600s it had fallen into ruin.

SEA TOWER AND BOTTLE DUNGEON Prisoners of higher status were held in the sea tower while others were confined in the grim ‘bottle dungeon’.

The remains of a wide-throated gunhole from one of the two blockhouses added for Archbishop James Beaton in the 1520s.

Robert, Prior of Scone, is appointed Bishop of St Andrews and later establishes an Augustinian house. The first castle may date from his time.

During the Wars of Independence, Edward I of England stays at St Andrews Castle and holds a parliament in the cathedral priory.

The castle is again occupied by English forces but is recaptured by Sir Andrew Murray after a three-week siege (and helped by a siege engine called ‘Buster’).

Walter Traill becomes Bishop of St Andrews and has the castle rebuilt to a layout that changes little from this point.

The beautifully decorated reception room was swept away during a storm in 1801.

Little remains of the early 1500s chapel with its ground-level open arcade and traceried windows.

Two contrasting tunnels were dug by attackers and desperate defenders during the 1546-47 siege.

A state apartment with an impressive new entrance front was built for Archbishop Hamilton after the 1546-47 siege.

1546

Protestant George Wishart is burned at the stake outside St Andrews Castle on the orders of Archbishop David Beaton, himself murdered soon after in a revenge attack.

1546-47

Government forces and rebels dig opposing tunnels through solid rock during the siege of 1546-47.

This imposing tower featured the castle entrance, which moved to its present position around 1390.

1550

Archbishop Hamilton has new state apartments built in the south range and adds a decorative entrance front bearing his coat of arms.

1606

Parliament separates the castle from the archbishopric and grants it to the Earl of Dunbar, but it is returned to Archbishop Gledstanes in 1612.

At Stirling Castle the King’s Inner Hall ceiling features carved heads, which include a makar; and, inset, a manuscript of Robert Henryson’s poems

As Scotland’s Year of Stories concludes, Ashley Douglas describes the evolving role of the Scots language in our nation’s past, present and future

The story of Scots is, in many ways, the story of Scotland. The Scots language and the Scottish kingdom developed symbiotically, each shaped by the other over centuries.

The earliest meaningful starting point for what would become Scots is ‘Anglo-Saxon’ or ‘Old English’ – the Germanic language first brought to these shores by invading Germanic tribes in the early centuries CE.

Over time, a northern dialect of AngloSaxon would develop in Scotland into the Scots language. It is the modern form of this medieval Scots language that many people speak, hear and write in Scotland today. At the same time, hundreds of miles to the south, a southern dialect of the same Anglo-Saxon language was developing into English.

Linguistically, historical Scots became characterised by significant influence from Old Norse, as well as by contributions from Flemish, Gaelic, French and Latin. Its unique tapestry of syntax, grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation and idiom embodies the unique experience of Scotland the nation; its multilingual inhabitants, its cultural aspirations, its trade and diplomatic relationships, its conflicts and alliances. In medieval and early modern Scotland, growth in linguistic distinctiveness coincided with growth in national and institutional status. Burgeoning Scots established itself as

the language of state, displacing Gaelic as the dominant spoken language and Latin as the language of record.

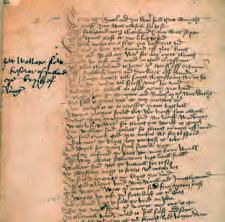

Scots begins to appear in formal documents from around the late 1300s. By 1424, it had replaced Latin in recording statutes of Parliament. Some Acts of the old Scottish Parliament, in Scots, are still in force and cited in Scottish courts today, such as the 1429 Lawburrows Act, which can be called upon by a person faced with violence: […]Itisstatuteandeordanitthatgifony ofthekingisliegishafonydoute ofhislifeouthirbededeormanance orviolentpresumpcioun…

[Itisstatuteandordainedthatifanyof theking’ssubjectshasanyfearforhis lifeeitherbydeedorthreatorviolent presumption…]

Scots became the medium of the Crown and the courts, law and politics, deeds and diplomacy, correspondence and commerce, national governance and local record keeping. It consolidated

this position through the 1400s, 1500s and 1600s.

It was also the day-to-day spoken tongue of thousands across the land. The sound of Scots echoed around burghs and towns, farms and fireplaces, as well as within castles and cathedrals.

Our national archives are bursting with primary records in Scots from these centuries. For this significant and prolonged period, Scotland’s tangible, written documentary history simply is Scots. There is no story of Scotland without it – and we cannot read the story of Scotland without knowing Scots.

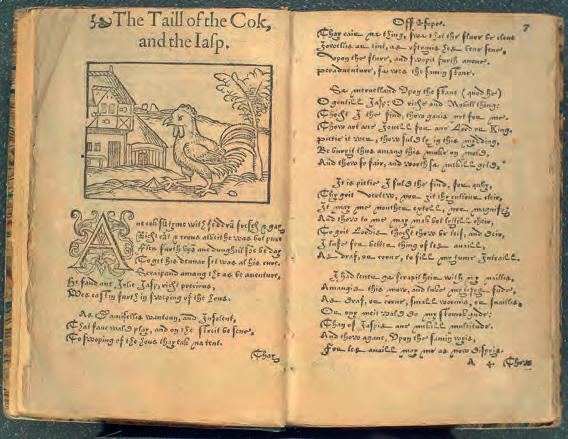

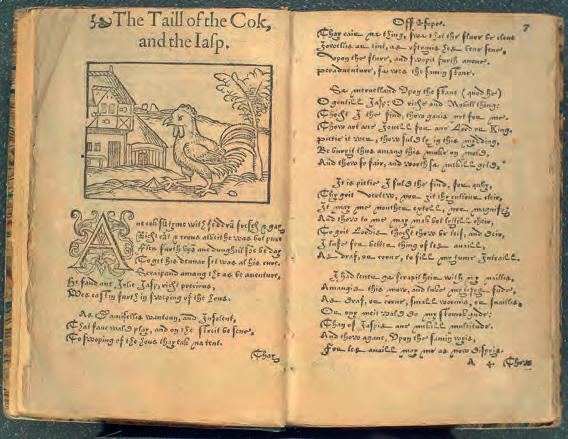

This era also brought forth a wealth of sophisticated literature in Scots, from historical chronicles and classical translations to political treatises, prose, plays and poetry.

The oldest recorded fragment of Scots takes the form of eight lines beginning “Qwhen Alexander our kynge was

During the 15th and early 16th centuries, great court poets such as Robert Henryson, William Dunbar, Gavin Douglas and Sir David Lyndsay wrote works of widespread renown, reflecting and shaping the cultural and political fabric of the Scotland in which they wrote.

This is also the time at which Scots first began to consciously term their language “Scottis” as distinct from

Court poets bring ‘Scottis’ to the fore

southern neighbour. In his prologue to The Eneados (1513), Gavin Douglas proudly asserts that his celebrated version of Virgil’s classic is “translatit furth of Latyn in our Scottis langage”.

Another famous Scottish monarch, Mary, Queen of Scots, spoke French, Scots and Latin. Many first-hand accounts, including from English envoys, testify to her speaking Scots, as do written records.

The Keeper of the Great Seal of Scotland under Mary was the statesman and judge Sir Richard Maitland of Lethington. He was also a significant Scots poet and much of his poetry is contained in the 1586 manuscript.

This early modern manuscript is also home to a remarkable lesbian love poem. Most likely written by Marie Maitland, a daughter of Sir Richard, this makes a Scots poem one of the earliest instances of sapphic poetry in Europe since Sappho herself –and a precious

dede”. Although believed to have been composed not long after the death of Alexander III in 1286, the earliest written source we have for them is TheOrygynaleCronykil of Andrew of Wyntoun in Scots, which dates from around 1420.

The earliest surviving work of Scots literature proper is TheBrus Penned by John Barbour in the 1370s, this 13,000-line epic poem tells the tale of Robert Bruce and the Battle of Bannockburn. It is a crucial source for one of the most iconic figures and events in Scottish history, and told in one of the languages Bruce would have spoken:

A!fredomeisanenobillthing, Fredomemaismantohafliking; Fredomeallsolastomangifis:

primary artefact of world LGBT+ history:

Thair is mair constancie in our sex

Then euer amang men hes bein no troubill, torment, greif, or tein nor erthlie thing sall ws disseuer

Sic constancie sall ws mantein

In perfyte amitie for euer.

[There is more constancy in our sex

Than ever among men has been No trouble, torment, grief, or suffering Nor earthly thing shall us sever Such constancy shall us maintain In perfect amity for ever.]

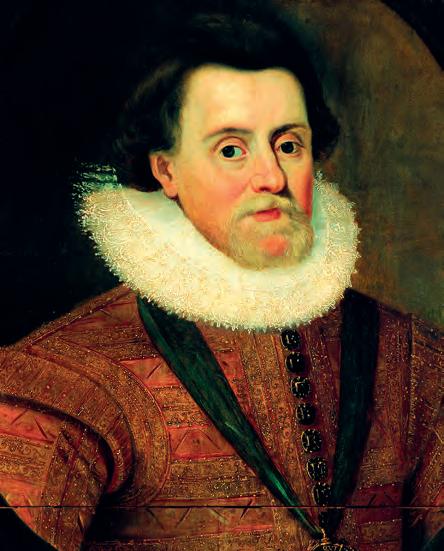

The oldest surviving work of Scots literature proper is The Brus. Penned in the 1370s, this epic poem tells the tale of Robert BruceJames VI, a prolific writer, and, inset, the only surviving manuscript of Blind Harry’s The Wallace William Dunbar Mannequin of Robert Henryson

In the early 15th century (1424), James I would become Scotland’s first, but not last, poet-king with his KingisQuair: a complex and elegant Scots love poem penned while he was in prison in England. Later that century (c.1470s), the poet Hary, also known as Blind Harry, wrote The Wallace, another famed epic poem in Scots about another of Scotland’s most famous sons, William Wallace.

Not only did the court of James VI – the son of Mary, Queen of Scots – nurture a rich Scots literary culture, he was also a prolific writer himself. Among his earliest works in Scots is AneSchortTreatise, ConteiningSomeReulisandCautelisto beObseruitandEschewitinScottis Poesie(1584). In the preface to his guide to writing poetry in Scots, James describes “Scottis” as “our language” and contrasts it to English, “quhilkislykestto ourlanguage”.

Another notable Scots work is his treatise on Dæmonologie, which was at the heart of the horrors of the Scottish ‘witch trials’. A poem by James VI also appears in The Maitland Quarto manuscript, as does poetry by John Maitland (a brother of Marie Maitland, who was likely also a poet herself), who served as the King’s Lord Chancellor.

In the last year of James’s reign in Scotland, Elizabeth Melville, Lady Culross, became the first Scottish woman to see her work in print with the publication of her Calvinist dream-vision in Scots, AneGodlieDreame: Into my dreame I thocht thair did appeir:

From this medieval and early modern heyday, a series of factors would contribute to the decline of Scots as a formal and institutional language for a time. Key among these were the dominance of English language bibles during the Reformation and following the 1603 Union of Crowns, when King James VI of Scotland became King James I of England following the death of Elizabeth I without an heir. The king and his court left Scotland for London, shifting the centre of elite cultural gravity firmly south. Just over a century

[Ah!freedomisanoblething, Freedommakesman[to]havehappiness; Freedomallsolacetomangives: Helivesateasethatfreelylives!]

Anesichtmaistsweit,quhilkmaid meweillcontent, AneAngellbrichtwithvisage schyningcleir, Withluifingluiksandwithane smylingcheir [IntomydreamIthoughtthere didappear: Asightmostsweet,whichmade mewellcontent, AnAngelbrightwithvisage

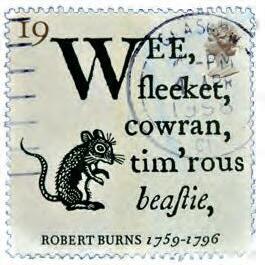

shiningclear, Withlovinglooksand withasmiling countenance]In the reign of James VI, Edinburgh Castle would have been alive with Scots culture Statue of Robert Fergusson (left); UK stamp from c.1996 featuring To a Mouse by Robert Burns (right)

Scots is once again being put to use as the medium of academic and formal prose, and … is being spoken in the Scottish Parliament

later, the 1707 Union of Parliaments would entail the loss of another centre of Scottish cultural and political power to London.

However, despite gradually conceding formal status to English, Scots was never displaced entirely. In fact, our language has proven remarkably resilient under the circumstances.

Scots has always continued to be spoken and sung by countless thousands of people across the country. It has also always continued to be written, albeit, until recently, limited largely to the realms of personal correspondence, poetry and literature.

The first major post-1700 literary landmark was the “18th century

vernacular revival”. Its best-known writer is one Robert Burns, whose celebrated verse put Scots firmly back on the map the world over.

This era also included poets, such as Allan Ramsay and Robert Fergusson, whose works inspired Burns and his contemporaries such as Isabel Pagan.

Many writers also used Scots to great effect in the dialogue of their novels, not least Sir Walter Scott.

Canongate Wall at Holyrood

Modern Scots writers such as Liz Lochhead and James Robertson continue the illustrious literary tradition of Scots – as do our series of Modern Makars. The incumbent Scots Makar, Kathleen Jamie, pictured above, writes beautifully and powerfully in both English and Scots: a direct link, in the Scots title she bears and the Scots words she writes, back to the Great Makars of the Middle Ages.

In the 2011 census, around a third of Scotland’s population reported that they could speak Scots. The words, sounds and grammatical forms still used by 1.5 to 2 million people today represent another unbroken link back to earlier ages of the Scots language.

features one quote from Scott’s Heart of Midlothian attributed to a Mrs Howden: Whenwehadaking,andachancellor, andparliament-menoourain,we couldayepeeblethemwistaneswhen theywerenagudebairns-But naebody’snailscanreachthelength o Lunnon.

The Scottish Renaissance of the early 20th century then saw a whole new flourishing of Scots poetry. Although defined by Hugh MacDiarmid, it embraced a wide range of poets, from Violet Jacob and Nan Shepherd to Lewis Spence and William Soutar. This was followed by the vibrant Scots folk revival of the mid1900s, driven in no small part by Hamish Henderson.

Recent years have also seen Scots begin to make a return to its old haunts of more formal spheres, after decades of dormancy in such spaces. For example, Scots is once again being put to use as the medium of academic and formal prose, and it is once again being spoken in the Scottish Parliament – our historical language of state, in modern form, in our new institution. It is reasserting itself and becoming renormalised in the higher register settings in which it first stretched its wings as a language and then held sway for centuries.

It is also being taught as part of the school curriculum as a language worth being literate in, with Scotsspeaking children learning that they are the inheritors of a proud tradition and (at least) bilingual in Scots and English.

The story of Scots is far from over. However, Scots today is recognised by UNESCO, the Council of Europe, and both the UK and Scottish Governments as a minoritised language in need of protection and promotion.

In the heritage context, by not only telling the story of Scots but telling it in Scots, we maintain an unbroken link to previous generations of Scottish history - who spoke an older version of the modern tongue that nearly two million of us, according to the 2011 census, still speak today. We also respect Scots and its speakers today and help to revitalise this rich language, ensuring its preservation far into the future. Lang may its lum reek.

Ashley Douglas is a researcher, writer and translator based in Edinburgh

Lang syne there wis a lassieDorothea wis her name She steyed at Huntintour in a castle she cried hame

This castle wis unusual and wis no quite aw it seemed fur it wisnae yin but twa tours wi a fearsome gap atween From The Maiden’s Leap by Fiona Davidson, HES Learning Officer

The legend of the Maiden’s Leap, set at Huntingtower Castle in Perthshire, has been retold as part of Scotland’s Year of Stories.

Fiona Davidson’s poem has been illustrated by Helen Wyllie and animated by Zoe Buyers. Advice was also provided by Dr Michael Dempster of the Scots Language Centre.

Pupils from Perth High School then used the poem to inspire their own versions in Scots.

The project won Scots Project of the Year at the Scots Language Awards in late September.

Fiona says: “We wir fair chuffed tae win whin thir wir sae mony ither guid projects nominatit. The bairns fae Perth High Schuill did awffy weel an noo caw thaimsels ‘published poets’.”

[Wewerereallypleasedtowin whenthereweresomanyother worthyprojectsnominated.The childrenfromPerthHighSchool didreallywellandnowcall themselvespublishedpoets.]

Search for ‘Maiden’s Leap story in Scots’ on YouTube

Join Lauren Welsh – Coordinator for Friends of Dundonald Castle –on a remarkable journey through 3,500 years of history

Dundonald Castle is one of Scotland’s gems, tucked away in the quiet rural landscape of South Ayrshire.

It was once home to King Robert II (1371-1390), grandson of Robert Bruce and founder of the Stewart dynasty.

The castle is the last of three strongholds built on this strategic spot for Robert II and his ancestors. Archaeologists have also found traces of occupation here reaching far back into prehistoric times.

Last year, the Friends of Dundonald Castle (FoDC) marked the 650th anniversary of the castle’s completion around the time of Robert II’s coronation in 1371.

FoDC also celebrated 25 years of this community charity, which is based at the visitor centre just down the hill from the castle. The existing castle, which stands guard over Dundonald village from its hilltop location, is one of the earliest and largest tower houses in Scotland.

Probably commissioned by Robert II himself, it was designed not primarily for defence but rather to make a bold show of his great wealth.

This is evident in the castle’s impressive barrel-vaulted ceilings and two grand halls – the Laigh Hall and the Great Hall – with their beautiful stonework and finishes.

The extant castle dates to the time of Robert II and was completed around 1371

These include two carved faces in the Laigh Hall, eight heraldic shields on the external north and west facing walls and, of course, the two mysterious Dundonald lions from which FoDC takes its logo.

Robert II’s castle had an inner and outer courtyard surrounded by a barmkin wall. Its foundations were formed from the remains of the west gatehouse of the previous castle, probably built for Robert’s great-grandfather, Alexander, the 4th High Steward of Scotland from 1241 to c.1282.

Prior to Alexander’s castle, you would have found a wooden motteand-bailey castle constructed around 1136 for the 1st High Steward of Scotland, Walter FitzAlan (d. 1177).

In Robert II’s time, the castle boasted a nearby deer park for hunting and would have afforded panoramic views over the Firth of Clyde. Even now, on clear days visitors can see Arran standing proudly to the west, the Paps of Jura to the north-west, Loudoun Hill to the east and sometimes even Ben Lomond to the north.

Robert II came from the Scottish nobility. He first appears in historical records at a parliament in Scone in December 1318 when, as the son of Robert Bruce’s daughter Marjorie, he was named as Bruce’s successor if the King of Scots should die without a legitimate heir.

In 1324, Robert’s chances of becoming king were reduced when Bruce and his

Many of the wonderful experiences that visitors to Dundonald Castle enjoy are delivered by a fantastic team of volunteers. From tours to events and everything in between, volunteers are kept busy and find the role rewarding.

Erik Bloodaxe (aka David Taylor, FoDC Tour Guide) says: “I started volunteering at Dundonald Castle in August 2015. I was fortunate to take early retirement and was looking for something to keep me busy. I also wanted to become more involved in village life.

“It soon became clear to me that this was no ordinary castle. Built for the founder of the Stewart/Stuart dynasty in the 14th century, this was the King of Scots’ favourite place. I love the fact that there have been three castles built on this same spot, not just the one visitors see today.

“I’m proud that our village has such a pivotal place in history and I get pleasure from telling everyone about it. I enjoy the look on visitors’ faces when they realise this isn’t any old castle but was once a spectacular royal palace dripping with history –literally dripping on rainy days!

“It is fascinating to meet people from all over the world, who often have their own interesting and sometimes hilarious stories to tell.

“When people tell me this was the best place they have visited, and the best tour, it makes my day.”

For more information about volunteering with FoDC, email info@dundonaldcastle.org.uk or visit dundonaldcastle.org.uk

second wife, Elizabeth de Burgh, had a son, David. Five years later, David succeeded his father to become David II. However, a parliament at Cambuskenneth in 1326 kept Robert’s hopes alive by recognising his place in the line of succession: the throne would pass to him if David should die without a direct heir.

There was an extensive Iron Age hillfort on what is now Castle Hill

Robert II was already a powerful figure in his own right, having inherited the role of high steward from his father Walter Stewart in 1326.

On 22 February 1371, he was at his castle in Rothesay on the Isle of Bute when news reached him of David II’s unexpected death at Edinburgh Castle.

Robert became the founder of a new dynasty for the nation’s royal family tree and his large family were to be major players in Scottish history.

Archaeologists carried out major excavations at Dundonald Castle between 1987 and 1994 and identified occupation of Castle Hill since 1500 BC. The archaeologists found evidence for the use of kilns or ovens dating back to the Bronze Age. This was followed by

Robert II became the founder of a new dynasty and his large family were to be major players in Scottish historyShakespeare’s Twelfth Night at the castle

A space for different groups to enjoy

The Friends of Dundonald Castle (FoDC) welcomed over 25,000 visitors to the site in 2019 – and things are now returning to this level of pre-Covid activity.

There are many events planned for next year and FoDC will continue to host regular community groups, including Knit N Natter, Scrabble, walking groups and the Write Here at Dundonald Castle writing group.

The visitor centre museum is a great place to explore the site’s long history. The castle itself has partially reopened to visitors with daily tours – pre-book tickets online or at the visitor centre.

The new coffee shop menu was launched in early spring, with compostable or biodegradable cups used for takeaways. There is also a small shop offering gift items by local suppliers, crafters and writers.

The Education Programme is now back on site and FoDC hope to welcome more than 100 education visits each year, with tailored sessions for different age groups that are tied to the Curriculum for Excellence.

For more details contact education@dundonaldcastle.org.uk

Dundonald Castle is open all year round, but opening times may vary. Pre-book your ticket at dundonaldcastle.org.uk. Free entry for Historic Scotland members.

● The HES region is Glasgow, Clyde & Ayrshire.

● The castle is in the village of Dundonald on the A71, five miles from Kilmarnock.

an extensive Iron Age or early medieval hillfort dating to around 500 BC-AD 1000. One of four such hillforts identified in the area – the site clearly chosen as a vantage point – it contained timber roundhouses.

This developed into a substantial dun-like complex consisting of a rectangular building enclosed by a drystone rampart. There is also evidence of vitrification – the use of fire to fuse the rampart rocks together.

The first castle was the motte-andbailey structure thought to have been built for Walter FitzAlan in the 12th century.

In turn, it was replaced by the stronghold probably built for Robert II’s great-grandfather, Alexander. An imposing defensive structure, it appears to have been destroyed and rebuilt on more than one occasion between 1300 and 1371.

The third and final castle is Robert II’s tower house, which was completed around 1371, the year he became King of Scots. When Robert died at his beloved castle in 1390, it was inherited by his son, John, who succeeded him as Robert III.

The castle then passed through a succession of families’ hands, including Kennedys, Wallaces, Boyds and Cochranes. Around 1560, it was left uninhabited and over time fell to

ruin. In recent years, archaeologists from the HES Cultural Resources Team have worked with FoDC and CFA Archaeology on further excavations.

In September, a one-week project focused on areas that had never been investigated for archaeology associated with the castle or the site’s earlier use.

A key objective was to engage the community in fieldwork and other processes. There was an enthusiastic response, and spaces for schoolchildren and other volunteers were quickly filled.

The project’s results will help to inform future interpretation and management of the property.

The latest chapter in the castle’s story began in 1953 when Dundonald Castle was given over to state care and work was carried out to make the site safe for visitors.

In the 1990s, FoDC was formed and took over the everyday running of the property, including the delivery of a dedicated visitor centre in 1998.

The visitor centre and a small area of adjacent land was purchased in February 2021 via a Community Asset Transfer from South Ayrshire Council, and the lively community hub continues to provide services and support.

Hopes for the future include a new centre to meet the changing needs of our community and visitors.

A visit to Dundonald Castle, museum and exhibition space is a great family day out. There is also plenty to enjoy in the surrounding area.

The castle is at one end of a popular walking route, The Smugglers’ Trail a 6.3-mile scenic route from Dundonald to Troon. Encounter ancient woodland, Sites of Special Scientific Interest, a loch and reservoir, and stunning views over the Firth of Clyde.

A shorter walk to Old Auchans house, just 1.3 miles from Dundonald Castle, provides another chapter in the castle’s expansive history.

Information leaflets are available from the castle’s visitor centre, which is fully accessible and has toilet facilities.

Only the third and final iteration of the castle can be seen today

In the 1990s, the Friends of Dundonald Castle was formed and took over the everyday running of the propertyOld Auchans House

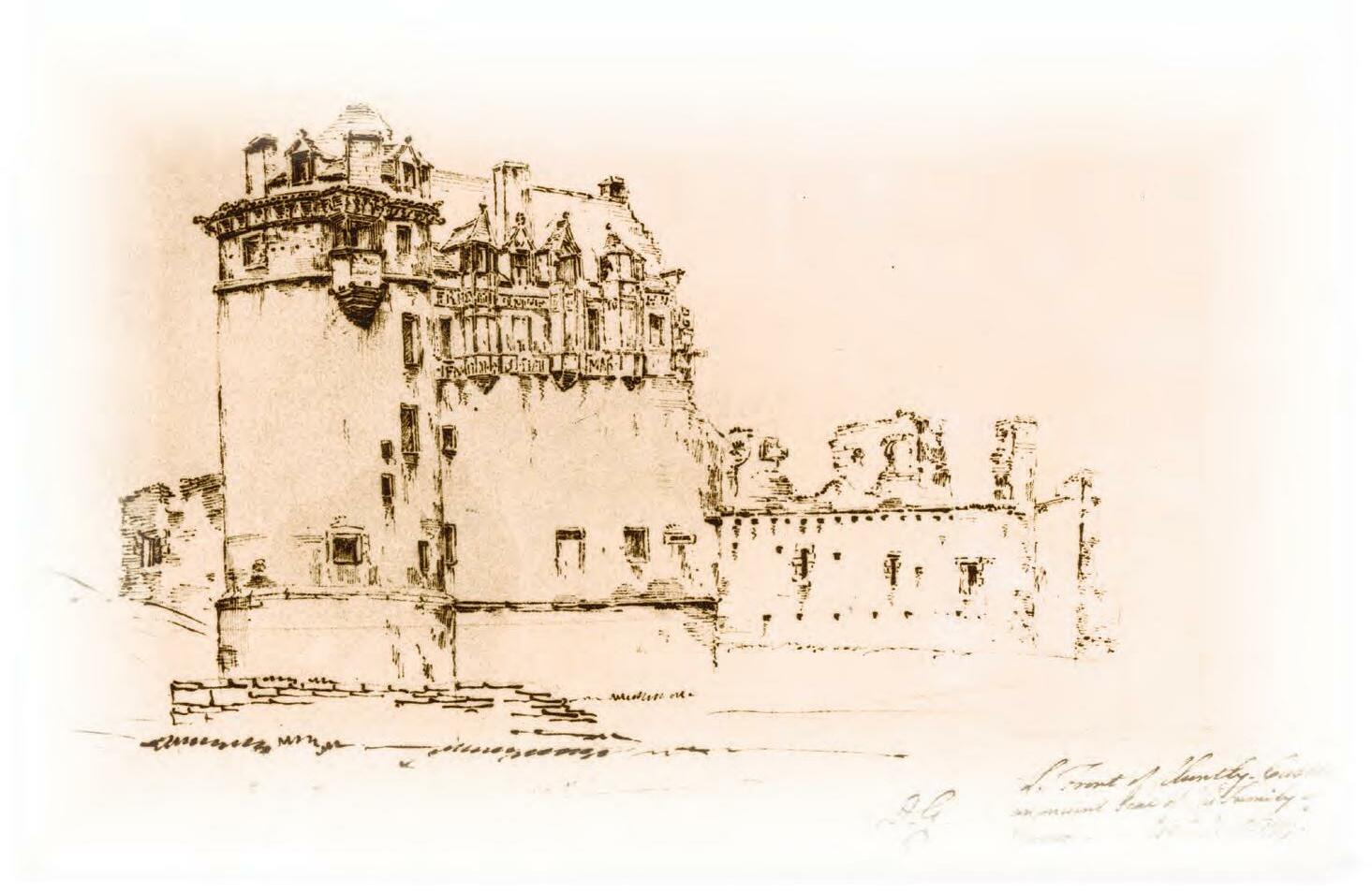

Huntly Castle surprised me. It’s nestled in beautiful trees, yet as a stronghold in the early 1200s it would have loomed large on the skyline and in public awareness. My first impression was of a magnificent ruin, but I quickly discovered there was much more to it, especially when talking to volunteer guide Gordon McKen.

His enthusiasm and encyclopaedic knowledge of Huntly Castle and its history detailed the importance of

the castle over the centuries and how it is still held in high regard locally.

Gordon started our tour in the courtyard, describing the three stages of the building’s development. A smooth grassy area is where the original castle stood, then known as Strathbogie, built of timber for an earl of Fife. It sat on a natural mound, overlooking an important crossing place where the rivers Bogie and Deveron meet.

NEVER BEEN TO…Volunteer Gordon McKen shows writer Joan around

The main elements were a motte (mound), where the lord’s residence was, and a bailey (an enclosure), which housed the great hall, chapel and stables. The timber building on the motte was then abandoned and replaced by a large stone L-plan tower house in the north-west corner of the bailey. Afterwards, a new stone-built great hall was constructed beside it.

The great hall was remodelled and enlarged in the second half of the 15th century. Its projecting round tower suggests French influence, as attached single towers were fashionable in France in late medieval times.

The castle was extended in the 1550s and, while the basement remained exactly as first constructed, the rest of it was raised by a storey and almost completely rebuilt to allow separate lodgings for the earl and his countess.

Work was done to the outside of the building, particularly the south front, around the early 1600s. The windows have a strong mix of French and Scottish styles. The aim seems to have been to create a classical building, with bold carved inscriptions in a style reminiscent of ancient Rome adding weight to this theory.

A series of sketches made by the artist John Claude Nattes in 1799 survives, including one, pictured right, showing the castle in detail – the highpitched roof, oriel windows rising through two storeys, the high conical

roof of the great round tower and fine dormer windows lighting the roof space. The loggia, a covered arcade, provided an open but sheltered place from which the family and guests might view the formal gardens and enjoy fresh air. As Gordon explained, the trees we see now did not exist then, so Huntly Castle had excellent views across the countryside in all directions.

The east range, with its projecting entrance porch, was the last major addition to the castle, probably in 1643, although it was never completed.

The courtyard has evidence of buildings that ensured both the sustenance and smooth running of

Huntly Castle had excellent views across the countryside in all directionsView from a south front dormer window

the castle. Some survive as foundations only, such as the stables, conveniently located to allow easy transfer of supplies to the cellars and kitchen.

The brewhouse, with the base of the vat still standing, and a bakehouse with two domed ovens, are in much better condition. These were vital to the castle, providing the household with its staple diet of bread and ale.

Huntly Castle is known as the ancient seat of the Gordons, having passed into the family’s possession in 1314. In a moment of exquisitely poor timing, the Strathbogie family, descendants of the earls of Fife, lost their lands and titles after choosing the losing side just before the Battle of Bannockburn.

Robert I then granted the lordship of Strathbogie to a loyal supporter, Sir Adam Gordon of Huntly in Berwickshire, beginning centuries of the north-east of Scotland being

known as ‘Gordon Country’. Around 1445, Alexander, 2nd Lord Gordon, was created Earl of Huntly and, in 1506, Alexander, the 3rd Earl, received a charter from James IV allowing him to change the name of his residence from Strathbogie to Huntly.

The loyalty of the Gordons and the grandeur of their castle resulted in continued royal favour, with James IV visiting frequently. In 1599, George, 6th Earl of Huntly, was elevated to become 1st Marquis of Huntly and, in 1684, George, the 4th Marquis, was created Duke of Gordon.

And so into the castle itself, through an elaborate Renaissance doorway. The lintel rests on slim classical pilasters and is decorated with grotesque animals and heraldry. Directly above is a panel bearing the arms of the 1st Marquis and Marchioness and, above that, the coat of arms of the sovereigns, James VI and Queen Anna of Denmark.

Two now empty panels – defaced when the Covenanters occupied the castle in the 1640s – once illustrated the Passion and Resurrection of Christ.

Everything is crowned by the figure of the warrior archangel Michael

triumphing over Satan, representing the victory of good over evil on the Day of the Last Judgement.

This was a bold statement by the marquis in an officially Protestant postReformation Scotland, proclaiming his Catholic faith along with his loyalty to the monarchy and to God. However, it also served to illustrate how powerful and well connected he was, and when the Covenanters removed all the religious imagery throughout the castle it was done without damaging the marquis’ heraldry.

We started on the first floor and, inside these walls, the people Gordon had already mentioned really came to life. This would have been the earl’s and later the marquis’ apartments, the most prestigious part of the castle, but also revealing some very ordinary details, such as the earl’s toilet seat in the closet. The great hall leads to an outer chamber and then an intimate inner bedchamber, which only those closest to the earl would have

Powerhouse of the bishops of Moray, Elgin Cathedral was attacked in 1390 by the ‘Wolf of Badenoch’.

been able to access. George, the 5th Earl, died here after suffering what appears to have been a stroke while playing football beside the castle. He was carried to his bedchamber and after his death there were apparently a number of supernatural incidents.

At first, the great space seems stark and echoing, but it is easy to visualise the sumptuous hangings and furnishings, and there are also some remaining parts of fine plaster cornices. The hall fireplace bears a mixture of heraldic devices and religious symbolism, with classical details, including pilasters and obelisks, framing the panels. The empty panel at the top doubtless once contained religious imagery considered idolatrous by the Covenanters.

The smaller back stair here served many purposes – the lord could easily visit the lady in her apartments above or slip away secretly

downstairs through the basement. That staircase could also provide a way for the lady to eavesdrop on the lord’s discussions, if she chose.

Holes for the pegs that kept wall hangings in place are clearly visible, as are the pistol holes below for firing at any would-be assassins creeping up the staircase.

Upstairs, the lady’s apartments have the same layout, including the toilet closet, which really was the height of sophistication at the time. There is a cosier air to these rooms and the fireplace in the lady’s great chamber is less ornate, with carved medallion portraits of the 1st Marquis and Marchioness, George Gordon and Henrietta Stewart, together with their arms and mottoes.

The basement has three large storage rooms preserved exactly as they were originally built in the 1400s, along with what was possibly a small prison at the

Duff House Designed by Scottish architect William Adam in the 18th century. Has a stunning collection of paintings and furniture.

Medieval stronghold of the Moray family and one of Scotland’s finest motte-and-bailey castles. It served as a fortress and home from the 1100s to the 1700s.

The back staircase provided a way for the lady to eavesdrop on the lord’s discussionsThe south front inscriptions

Football proved fatal for the 5th Earl of Huntly

After the 5th Earl’s death, a contemporary account by clergyman Richard Bannatyne described strange events.

With the earl’s body in the chapel awaiting burial, his empty bedchamber had been locked and the keys given to a trusted noble, John Hamilton. The earl’s brother Patrick was outside the chamber with a group of men when he heard loud noises within.

Patrick investigated and candles were brought. The noises returned and the candles flickered. Some claimed the earl had ‘risen again’ but Patrick demanded that no such rumours be spread.

Was this a true account?

Bannatyne, a staunch Protestant who was critical of the Gordon family, may have written it to pass judgement on the earl’s moral character.

bottom of the tower. Strangely enough, these storage rooms eventually brought disaster to the Gordons.

In 1556 Mary of Guise, the queenregent, visited Huntly and was entertained so splendidly that she was concerned about the financial impact on the 5th Earl. When he reassured her by displaying the castle’s huge vaults full of provisions, his conspicuous wealth prompted the French ambassador to say to Mary that “the wings of the Cock of the North should be clipped”.

It was her daughter, Mary, Queen of Scots, who did the clipping in 1562, when the royal army confronted the earl at Corrichie, 24 miles south-east of Huntly Castle. Gordon was captured but later fell from his horse and died.

His embalmed corpse was tried and found guilty of treason in Edinburgh, and his castle ransacked.

The family’s lands and titles were restored in 1565 to George Gordon, who became the 5th Earl and remained loyal to Mary during the civil war that followed her flight to England in 1568. The 5th Earl’s son George, although a favourite of James VI, put this to the test through various acts of treason, including communicating secretly with the Catholic king of Spain.

In 1594, James VI finally acted against Huntly and his fellow conspirators, the Earls of Errol and Angus, forfeiting their titles

and estates. In 1599, there was a reconciliation and the earl was created Marquis of Huntly. He began a major programme of repair and embellishment, continued by his son George, 2nd Marquis of Huntly.

The 2nd Marquis supported Charles I during various civil wars and lost his life on the scaffold in 1649. Charles II visited Huntly before his coronation at Scone in 1650. The castle was later occupied by government troops during the 1745-46 Jacobite Rising, but its days as a noble residence had long gone.

Huntly Castle remained important to the town, nurtured by Elizabeth Brodie, who married George, the 5th Duke of Gordon, in 1813. After his death in 1836, she lived in Huntly Lodge, now the Castle Hotel, and was known for her kindness to the people of the town.

Huntly Castle is open daily 10am to 4pm (last entry 3pm), except Thur and Fri, until 31 March 2023

● The castle is in Huntly off the A96.

● The HES region is North & Grampian.

● The Huntly Castle Explorer Quiz, in English or Doric, is a great way to turn your visit into a factfinding mission for all the family.

The castle remained important to the town, nurtured by Elizabeth Brodie, who was known for her kindnessThe prison in the tower basement

From the moment a trio of Islamic glass fragments were unearthed during excavations carried out at Caerlaverock Castle, near Dumfries, in the late 1990s, unravelling the story of their origins has proved a tantalising puzzle. The first and only glass of its kind to be found at an archaeological site in Scotland, it is thought to come from a drinking beaker made in the Middle East during the 12th or 13th centuries.

But how did it end up here? That’s where things get interesting. It is believed that the original vessel may have been made in modern-day Syria, Iraq or Egypt – all were important centres of Islamic glass-making during this period.

The pieces are inscribed with part of the Arabic word for ‘eternal’, likely used as one of the 99 names of Allah, which suggests that it could be an extract from the Qur’an. Although tiny in size – at 3.1cm x 2.8cm, the largest fragment is smaller than a ping-pong

ball – the glass could help shed light on Scotland’s contact with the wider world during the medieval period.

Theories posited include that the beaker may have come to Caerlaverock Castle through trade or could even have been brought back by returning crusaders.

The glass was discovered during investigations at the site of the old Caerlaverock Castle, in an area of woodland behind the surviving and better-known ‘new’ Caerlaverock Castle, a medieval fortress once caught up in bloody border conflicts.

According to Stefan Sagrott, archaeologist and Senior Cultural Resources Advisor, the glass fragments are an “absolutely astounding” find.

“There were excavations done in the Victorian period, with some digging into the castle mound and a few artefacts taken away, but unfortunately not much was written up afterwards,” he says.

Susan Swarbrick pieces together the story of some remarkable fragments of glass found on the site of the original Caerlaverock CastleThe ‘new’ Caerlaverock Castle, not far from where Islamic glass fragments were found

“In the intervening years, a lot of the visible stonework from the old castle was robbed and the site within Castle Wood became overgrown with vegetation – you wouldn’t have known the old castle was even there.

“The excavations carried out in 1998 and 1999 – when the glass fragments were found – were the first time the old castle was investigated in any modern sense. If you go today, you can see the wall footings and layout of the old castle with interpretation boards.”

Over time, explains Stefan, several conflicting theories about the origins of old Caerlaverock Castle have emerged. “It was known something was there, probably some sort of a castle or manor house,” he says.

“Back in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, people thought it might have been a Roman fort because it is quite rectangular in shape. What is actually the moat, they interpreted as big ditches. That theory was put to bed later in the 19th century by the antiquarians who found medieval remains.”

While it was hoped that the excavations in the late 1990s would reveal more about the site’s history, nothing could have prepared the investigating team for such a monumental discovery.

“It would have been absolutely astounding to find those pieces of glass,” says Stefan. “The castle dates from the 1220s up to the 1270s. In the 13th century, glass was quite a rare substance. It was used for stained glass windows in monasteries, cathedrals and some smaller churches and chapels.

“But it is very rare to find it being used for window glass in castles and tower houses at this time because, as a rule, that doesn’t come until a couple of hundred years later.

“You wouldn’t have many vessels or objects made from glass either. And, if people did have them, they don’t tend to survive today. The problem with glass is it degrades quickly when it is in acidic soil, found a lot in Scotland. So we’re always going to lose evidence.

“Pottery is more common because it survives well in the ground. And while there may well have been glass objects too, we don’t have any evidence of that at this time. So, to come across Islamic glass from the 13th century in a south west Scotland castle? That is the jewel in the crown.”

As for how the beaker might have ended up there?

“There are a number of different ideas,” says Stefan. “It could have been purchased from someone on the continent – Venice was often a trading point for bringing Middle Eastern glass in. Someone may have gone on a crusade. This is the right time for people to be going on early crusades to the Middle East and the Near East. However, we don’t have enough historical evidence currently to say whether those who lived at the castle were involved in the crusades.”

Another significant detail is the location where the glass fragments were discovered. “Within the old castle, the shards of the glass vessel were found within the chamber block – this was inside the building, rather than dropped outside,” Stefan says.

“The chamber blocks were where the bedrooms were, rather than being in the lord’s hall, for example. This would again suggest the beaker was such an important piece it was kept safe and secure in their private residence rather than in a room open to guests, although I’m sure it would have been brought out to show people.”

Now, almost a quarter of a century after the fragments were discovered at Caerlaverock Castle, they are back in the spotlight at the heart of a new project called Eternal Connections, one that aims to spark discussion and learning around the heritage of Scotland’s Muslim communities.

Working with 3D models, creative practitioners and community groups, Eternal Connections utilises cuttingedge scientific analysis and research data. Its goal is to forge new ways of understanding the contemporary and historic connections between Scotland and Islam. In doing so, the project has worked with community groups, including Muslim Scouts in Edinburgh and the Glasgow-based AMINA –Muslim Women’s Resource Centre,

The problem with glass is it degrades quickly when it is in acidic soilOld Caerlaverock Castle where the fragments were found during a 1990s excavation (below)

Above and centre:

Braid Salaam

Scouts visiting Stirling Castle as part of the project

Photogrammetry helps to create precise 3D models of the fragments

to provide a series of informative workshops centred on the story of the Islamic glass.

The first phase used state-of-the-art techniques to analyse the fragments and produce 3D data. Adam Frost, a Senior Digital Documentation Officer, was part of the team that worked on this stage.

“It was quite a challenging project,” he explains. “From a 3D digital documentation point of view, one of the biggest challenges can be the material and surface finish of an object.

“In this case, the objects are made from glass and have unique surface characteristics. Some parts of the glass are reflective, other parts are matt and not reflective. The techniques we use to capture three-dimensional data can struggle a little bit with surfaces that reflect light in different ways.

“For example, a matt object, such as a sandstone block or carved limestone, is traditionally quite easy to capture. A shiny object is the opposite, especially when it refracts light or is highly reflective like glass is.”

The technique used, Adam says, was photogrammetry – a process that involves taking overlapping photographs of an object, structure or space to extract 3D information. “On average we took about 700 photographs of

each fragment,” says Adam. “Imagine an object rotating on a turntable, while the camera moves to new positions relative to that object position. This gives a series of unique views and enables us to build a reliable, 3D representation of the object.”

In the second phase, Stirlingshirebased visual artist Alice Martin was tasked with using the gathered data to create a 3D-modelled digital reconstruction of the glass fragments, showing what the beaker may have looked like as a whole.

Alice, who has degrees in Archaeological Studies and Contemporary Art Practice, spent three months working on the project. She began her research by tracking down comparative examples of the beaker online, as well as sourcing books specific to Islamic glass.

“The books contained many similar beakers and confirmed the popularity of a range of features, such as applying blue enamel paint to fill large areas, red to outline and gold for inscriptions,” she says. “I also worked with professionals knowledgeable in Arabic to come up with a potential sentence for the band around the beaker.

“HES provided me with different 3D and analytical data, and this included three separate 3D models of the fragments and details of the XRF [X-ray fluorescence] analysis that was undertaken. Having the models allowed me to use them for scale and to overlay the pieces onto the reconstruction.

“The Heritage Science team applied a non-destructive technique to investigate the materials of the glass, determined with a handheld XRF analyser. The presence of several chemical elements helped in knowing where parts of the blue, white and red enamel paint and gold gilding were on the artefacts.”

There were some fascinating and unexpected moments too. “I was surprised through reading chapters on enamelled glass, then seeing images online and in print, that red was used to outline characters and imagery when combined with blue, white and gold,” says Alice.

“From the fragments themselves and the scientific analysis we can’t be certain this was the case for the ones in the collection, but the data did pick up on red touching the blue on one of the three fragments. I think it’s reasonable to assume that the red was used to outline.

“Another reason is that this type of Islamic glass was thought to be valuable; it’s very precise and delicate, also evident in the inclusion of gold. So, more embellishment seems likely, which is why I wanted to convey this possibility in the reconstruction.”

As part of her remit, Alice was involved in the community group sessions. “I ran two workshops, one with the Muslim Scouts in Edinburgh and another with AMINA at The Engine

Shed in Stirling to share my creative process and to kickstart conversations,” she recalls.

“Both the workshops focused on the beaker shape, decorative designs and calligraphy, using pipe cleaners with the younger children and acrylic paint onto individual 3D prints with the women.”

Aisha Qadar, Cub Section Leader for the 8th Braid Salaam Scouts in Edinburgh, describes the Eternal Connections project as a hugely worthwhile experience. Her group –with members aged six to 18 – took part in two workshops in May and visited Stirling Castle for a day trip. Among the activities was a calligraphy lesson, with participants learning to write some of the 99 names of Allah in Arabic script and Gaelic. Other elements focused on archaeology and demonstrated the technology used to analyse the glass fragments.

“Learning about the connection between Scottish heritage and their Islamic identity is something the children enjoyed and saw value in,” says Aisha. “The fact there is a connection that goes back 800 years here in Scotland gives us a real sense of belonging.”

3D printed vessels decorated by AMINA workshop participants

AMINA – Muslim Women’s Resource Centre – took part in six workshop sessions through July and August. Here, Creative Wellbeing Practitioner Vicky Mohieddeen shares why it felt important to her to be part of the Eternal Connections project: “As a woman of mixed Middle Eastern and Scottish heritage, who grew up in the rural south of Scotland, the story of the glass and where it was found immediately captured my imagination.

“Eternal Connections provoked very strong reactions within our group – more than I think anyone could have anticipated. These small pieces of glass held within them themes of separation, uncertainty, homeland and family – themes with a particular resonance for our group.

“Many of the women in our group are prevented from working and participating in society due to the UK asylum system, so giving them the opportunity to share their own extensive knowledge about history and culture with the HES team had a big impact.

“The women enjoyed the opportunity to travel to sites around Scotland and many commented that the ancient ruins reminded them of home.”

Islamic glass was thought to be valuable; it’s very precise and delicateSharing stories with AMINA

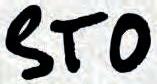

A popular character encountered at many of

has been busy creating

new babywear

This new selection of cute and colourful items includes a baby romper suit, hat, bib and, of course, the much-loved

Bear.

’Twas the night before Christmas… but don’t leave your gift buying that late!

Shop online for our collection of gift ideas from Scottish suppliers for cosy feet and tasty treats! From luxurious cashmere from Johnstons of Elgin to cufflinks and quaichs from the traditional crafters at Pewtermill, there’s something for everyone.

Christmas shopping all wrapped up? Treat yourself to a Highland Soap gift set and enjoy the scents of Scotland.

Immerse yourself in a twinkling festive season

Find out more at

Castle of Light: A Kingdom of Colours

CASTLE Various dates from Fri 18 Nov-Fri 30 Dec; 4.30pm-9pm (last entry between 7.30pm and 7.45pm).

Family tickets and

Listen to some remarkable tales at Stirling Castle

from

Sat

Nov;

for a

Castle of

from the

of

the

in a

the

Stirling Castle after

Encounter characters from the castle’s past and watch them bring the castle tales to life.

Christmas Shopping Fayre STIRLING CASTLE Tues 6 Dec; 6pm-9pm (last entry 8.15pm). Entry £6. 01786 450000 stirling.castle @hes.scot stirlingcastle.scot/ festive

The popular Shopping Fayre returns for 2022. Stock up for the festive season in the splendour of the Great Hall, with stalls showcasing the very

best of local Scottish brands, crafts, and fine foods and drink.

A Christmas Carol STIRLING CASTLE Fri 16-Sun 18 Dec; 7pm-9.30pm (doors open 6.15pm). BSL interpreted performance, Sun 18 Dec. Adults £17; concessions £15; children (including under fives) £13. Family tickets and 10% members discount available. 0131 668 8885 events@hes.scot stirlingcastle.scot/ festive

On Christmas Eve, the miserly Ebenezer Scrooge is taken on a terrifying journey through the past and into the future. Join the Chapterhouse Theatre Company for this family treat, as Scrooge’s frozen heart begins to melt and he finally embraces the festive spirit in this most Christmassy of Christmas tales.

Until Sun 15 Jan 2023, during site opening times. 01667 460232 historicenvironment. scot/events

This exhibition explores the stories of people who shaped and were shaped by Scotland.

RING OF BRODGAR

Until Mar 2023, every Thu (except 22, 29 Dec and 5 Jan); 1pm. 07920 450540 orkneyrangers @hes.scot historicenvironment. scot/ranger-service

Join the Rangers to learn more about the Ring of Brodgar.

STANDING STONES OF STENNESS AND BARNHOUSE VILLAGE

Until Mar 2023, every Wed (except 21, 28 Dec and 4 Jan); 10am. 07920 450540 orkneyrangers

@hes.scot historicenvironment. scot/ranger-service

Find out about the close connection between these sites and their part in the story of Neolithic life.

STIRLING CASTLE

Until Wed 7 Dec,

STIRLING CASTLE Wed 14 Dec-Sun 12 Mar 2023, during site opening times. 01786 450000 historicenvironment.scot/ events

Drawn from our archives and other sources, this exhibition

looks at the international context that shaped the mid-century modern architectural movement in Scotland. Displays explore the ways in which Scottish architects influenced and were influenced by the international movement.

STIRLING CASTLE

Thu 8-Sat 10 Dec, Tue 13-Thu 15 Dec, Wed 21-Fri 23 Dec; 1.30pm.

Adults £30, £35 with Prosecco (members £22.50, £28 with Prosecco); children £12.50 (child member £11.25).

01786 469491 stirlingcastleevents@benugo.com stirlingcastle.scot/ festive

Make Christmas special with afternoon tea in the Tearooms at Edinburgh Castle, or in the Great Hall at Stirling Castle.

EDINBURGH CASTLE Fri 9 Dec, Sat 10 Dec, Fri 16 Dec; 12pm.

during site opening times. 01786 450000 historicenvironment. scot/events

A new film exhibition pays homage to Scotland’s untold Black history at Stirling Castle.

DUFF HOUSE

Until Sun 26 Feb 2023, during site opening hours. 01261 818181 historicenvironment. scot/events

Presenting the best of contemporary portraiture from the prestigious 2022 Scottish Portrait Awards.

BLACKNESS CASTLE Sat 12 Nov-Sun 12 Feb 2023, during site opening hours. 01506 834807 historicenvironment. scot/events This exhibition, drawn from our archives, explores Scotland’s relationship with the sea and its impact on everyday life.

EDINBURGH CASTLE

Thu 1-Fri 2 Dec, Sun 4-Thu 8 Dec, Sun 11-Thu 15 Dec and Sun 18-Thu 22 Dec; 1pm, 1.30pm and 2pm. Adult £30, £35 with Prosecco or Edinburgh Castle Gin (members £22.50, £28 with drinks); children £12.50 (child member £11.25). 07469 350247

edinburghcastleqa @benugo.com edinburghcastle. scot/festive

Adults £45 (members £40); children £25 (child member £22.50).

07469 350247 edinburghcastleqa @benugo.com edinburghcastle. scot/festive

A very special threecourse lunch in the Queen Anne Room.

TRINITY HOUSE

Fri 9 Dec; 12pm-4pm. 0131 554 3289

trinityhouse @hes.scot historicenvironment. scot/events

A warm festive welcome awaits you at Trinity House.

History is calling this Christmas!

Surprise loved ones with adventures and great days out with a Historic Scotland membership. Our gift membership pack will be sent directly to the recipient and you can make their gift extra special by adding a personal message. If that wasn’t enough, as a member you will receive 20% discount when purchasing your gift membership. The quickest and

easiest way to purchase your Christmas gift is to go online. To get your 20% discount check you are registered and logged into the members’ website at historicenvironment.scot/member

For more information visit hsitoricenvironment.scot/member or call 0131 668 8999. Terms and conditions apply.

The origins of curling are uncertain but it is thought the game evolved in Scotland. Paisley Abbey archives from 1541 refer to a “contest with stones thrown upon the ice”.

The first stones were raw materials but by the late 18th century they were

more refined, with smooth, polished surfaces. Granite quarried from Ailsa Craig off the Ayrshire coast was –and still is – considered the best source.

The Royal Caledonian Curling Club formed around 1838 and the first Grand Match, or Bonspiel, was

played in 1847. The last outdoor Bonspiel was played in 1979 on Lake of Menteith.

World Championships have taken place for almost 50 years and curling featured at the Winter Olympics for the first time in 1988, in Canada. In 2002,

Scotland’s women curlers won Olympic gold in a nail-biting final in the US.