HISTORICAL NOVELS REVIEW

AUGUST 2025 ISSUE 113

GREECE & ROME

Mythology, Legends, and Novels | More on page 8

FEATURED IN THIS ISSUE

...

Hope & the Happy Land

Two New Post-Civil War Historical Novels

Page 10

For Queen & Country

The Espionage Fiction of C.P. Giuliani

Page 12

Late Bloomer

Karen Cushman's HF for Children & YA

Page 12

The Girl from Greenwich Street

Lauren Willig on the Manhattan Well Murder

Page 14

An Overlooked Story

Linda McQuaig's The Road to Goderich

Page 15

Historical Fiction Market News

Page 1

New Voices

Page 4

History & Film

Page 6

HISTORICAL NOVELS REVIEW

ISSN 1471-7492

Issue 113, August 2025 | © 2025 The Historical Novel Society

PUBLISHER

Richard Lee

Marine Cottage, The Strand, Starcross, Devon EX6 8NY UK <richard@historicalnovelsociety.org>

EDITORIAL BOARD

Managing Editor: Bethany Latham

Houston Cole Library, Jacksonville State University 700 Pelham Road North, Jacksonville, AL 36265-1602 USA <blatham@jsu.edu>

Book Review Editor: Sarah Johnson

Booth Library, Eastern Illinois University, 600 Lincoln Avenue, Charleston, IL 61920 USA <sljohnson2@eiu.edu>

Publisher Coverage: Bethany House; Bookouture; HarperCollins, IPG; Penguin Random House US; Severn House; Australian presses; university presses

Features Editor: Lucinda Byatt

13 Park Road, Edinburgh, EH6 4LE UK <textline13@gmail.com>

New Voices Column Editor: Myfanwy Cook

47 Old Exeter Road, Tavistock, Devon PL19 OJE UK <myfanwyc@btinternet.com>

REVIEWS EDITORS, UK

Ben Bergonzi

<bergonziben@gmail.com>

Publisher Coverage: Birlinn/Polygon; Bloomsbury UK; Duckworth Overlook; Faber & Faber; Granta; HarperCollins UK; Head of Zeus; Orenda; Pan Macmillan; Simon & Schuster UK; Storm; Swift Press

Alan Fisk

<alan.fisk@alanfisk.com>

Publisher Coverage: Aardvark Bureau; Black and White; Bonnier Zaffre; Crooked Cat; Freight; Gallic; Honno; Karnac; Legend; Pushkin; Oldcastle; Quartet; Saraband; Seren; Serpent’s Tail

Ann Lazim

<annlazim@googlemail.com>

Publisher Coverage: All UK children’s historicals

Aidan Morrissey

<aidankmorrissey@gmail.com>

Publisher Coverage: Allison & Busby; Canelo; Penguin Random House UK; Quercus

Adele Wills

<adele.wills@btinternet.com>

Publisher Coverage: Alma; Atlantic; Canongate; Glagoslav; Hachette UK; Pen & Sword; The History Press

REVIEWS EDITORS, USA

Tracy Barrett

<tracy.t.barrett@gmail.com>

Publisher Coverage: All North American children's historicals

Kate Braithwaite

<kate.braithwaite@gmail.com>

Publisher Coverage: Poisoned Pen Press; Skyhorse; Sourcebooks; and Soho

Bonnie DeMoss

<bonnie@historicalnovelsociety.org>

Publisher Coverage: North American small presses

Peggy Kurkowski

<pegkurkowski@gmail.com>

Publisher Coverage: Bellevue; Blackstone; Bloomsbury; Casemate; Macmillan (all imprints); Grove/Atlantic; and Simon & Schuster (all imprints)

Janice Ottersberg

<jkottersberg@gmail.com>

Publisher Coverage: Amazon Publishing; Europa; Guernica; Hachette; Kensington; Pegasus; and W.W. Norton

REVIEWS EDITORS, INDIE

Karen Bordonaro

<kbordonaro@historicalnovelsociety.org>

Publisher Coverage: all self- and subsidy-published novels

EDITORIAL POLICY & COPYRIGHT

Reviews, articles, and letters may be edited for reasons of space, clarity, and grammatical correctness. We will endeavour to reflect the authors’ intent as closely as possible, and will contact the authors for approval of any major change. We welcome ideas for articles, but have specific requirements to consider. Before submitting material, please contact the editor to discuss whether the proposed article is appropriate for Historical Novels Review

In all cases, the copyright remains with the authors of the articles. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without the written permission of the authors concerned.

MEMBERSHIP DETAILS

THE HISTORICAL NOVEL SOCIETY was formed in 1997 to help promote historical fiction. We are an open society — if you want to get involved, get in touch.

MEMBERSHIP in the Historical Novel Society entitles members to all the year’s publications: four issues of Historical Novels Review, as well as exclusive membership benefits through the Society website. Back issues of Society magazines are also available. For current rates, please see: https://historicalnovelsociety.org/members/join/

Brigitte Dale, Martha Jean

& Emma Pei

HISTORICAL FICTION MARKET NEWS

HNS UPDATES

Indie reviews editor J. Lynn Else is stepping down after four years in the role; HNS extends thanks for her work coordinating the reviews of hundreds of indie-published historical novels and bringing them to readers’ attention. We’re also welcoming Karen Bordonaro as the incoming reviews editor for indie titles. Karen is Librarian Emeritus at Brock University in Canada and has written three nonfiction books and numerous articles. She has been reviewing for HNR since 2023 and has great interest in supporting indie-published historical fiction.

NEW BOOKS BY HNS MEMBERS

Congrats to everyone who sent in details on their new books! If you’ve written a historical novel or nonfiction work published (or to be published) in April 2025 or after, send the following details to me at sljohnson2@eiu.edu by October 7: author, title, publisher, release date, and a blurb of one sentence or less. Please shorten your blurbs down to one sentence, as space is limited. Details will appear in the November 2025 issue of HNR. Submissions may be edited.

Despite its mean title, White Hell by Sean Tyler (Level Best/Historia, Jan. 21) is a love story at heart... though one loosely based on the Donner Party.

In Julie L. Brown’s Bend, Don’t Break (JAB Press, Feb. 4), drawing strength from the memory of their ancestor, Aisha, a slave born free on the west coast of Africa, seven generations of Black women across the sweep of American history will do anything to succeed—and will do even more to protect their daughters.

In The Price of Eyes (Scotland Street Press, Feb. 14), fourth and final book in Janet McGiffin’s historically accurate series about the 8thcentury Byzantine Empress Irini of Athens, the powerful empress tricks her emperor son into releasing her from house arrest and returning her to the throne of Constantinople, where she manipulates him into divorcing and exiling his wife and daughters, leading to civil war and war between mother and son where neither can survive.

Born to Trouble (Independently published, Feb. 27), book 4 in Regan Walker’s The Clan Donald Saga, tells the story of Alexander of Islay, Lord of the Isles and Earl of Ross, who triumphed over a deceitful king to become one of Scotland’s ruling lords in the 15th century.

House of Farrell by Robert M. O’Brien (Amazon, Feb. 27) is a powerful historical novel telling the story of four generations of the Farrell family, from the horrors of the Irish Potato Famine to the violence and corruption of the Greenwich Village waterfront and into the reaches, high and low, of Tammany Hall.

Charlotte Whitney’s A Tiny Piece of Blue (She Writes Press, Feb. 18) is a heartwarming novel following a homeless girl as she struggles to survive during the Great Depression while setting the traditions of rural Michigan against a backdrop of thievery, bribery, and child trafficking—a suspenseful yet tender tale.

Pawnee Prisoner: The Story of Jane Gotcher Crawford (Booklocker. com, Feb. 20) by Vivian McCullough is based on the true story of courage, determination and survival in 1830s Texas when the widow of an Alamo defender is taken captive along with three children.

In 1904 London, as unrest brews and a lord mysteriously vanishes from a gentleman’s club, young Prime Minister Felix Grey must confront buried secrets and mounting conspiracy to save a nation on the brink in Mario Theodorou’s Felix Grey and the Descendant (Neem Tree Press, Mar. 6).

A war-torn country lies between Eloise of Dahlquin, and Roland, the Lord of Ashbury At-March, as they try to make their way back to each other, navigating a political landscape fraught with intrigue and betrayal; one threat is vanquished, but others loom in the shadows in Anne M. Beggs’ By Arrow and Sword, Book Two of the Dahlquin Series (Self-published, Mar. 21).

Lady of the Quay by Amanda Roberts (Independently published, Apr. 22), first in the Isabella Gillhespy Series, takes place in 1560, in Berwick-upon-Tweed, northern England; after the unexpected death of her father, Isabella Gillhespy finds herself facing financial ruin and trying to prove she is innocent of crimes that would threaten her freedom, if not her life.

In his quest to make gold, an alchemist in 1352 London seeks the Key to the Philosopher’s Stone and, ultimately, divinity—a pursuit considered to be blasphemy in the eyes of the Church, in Through the Lion’s Gate, A Medieval Tale of Intrigue and Transmutation by Stuart Balcomb (Amphora Editions, May 1).

Unfamiliar Territory (mks publishing, May 3) by Mary Smathers is the gripping story of one woman’s journey through Gold Rush California to find her son, and herself.

At once an intimate love story and a multigenerational family drama inspired by a trove of politically charged, passionate love letters sent to his mother, Robert Kehlmann’s The Rabbi’s Suitcase (Koëhlerbooks, May 6) recounts his family’s 50-year migration odyssey from 1880s Lithuania to Ottoman, then Mandatory Palestine, to Depression-era America.

Jane Loeb Rubin’s Over There (Level Best/Historia, May 27), the third installment of the Gilded City trilogy, immerses readers in the gripping journey of four family members from Threadbare and In the Hands of Women, all dedicated doctors and nurses facing the daunting realities of The Great War.

Roger Hunt’s first novel, Vindicta (Troubadour, May 28), based closely on events of 1808/9, tells the remarkable story of a Scottish Benedictine monk who is sent on a secret mission to Germany.

A Tiger in the Garden by India Edghill (Talitho Press, June 1) is a sweeping tale of romance and politics set in the splendor of Victorian India.

In December 1971, as the Bangladesh War of Liberation faces its critical final battles, Doctor Meena struggles against the forces that threaten to undermine her commitment to the people she serves, as the full force of an army is unleashed against her and her community in the novel Niramaya: A Female Medic’s War Journey by Sean C. Ward (Troubador, June).

Enter the world of the 16th-century “Border Reivers” and ride with Fingerless Will Nixon as he carves his legend into the hills of

Scotland’s Borderlands in The Legend of Fingerless Will Nixon: The Scottish Borderlands 1508-1509 by Richard Nixon (Amazon KDP, June 5).

In Daughter of Mercia by Julia Ibbotson (Archbury Books, June 6), medievalist Dr Anna Petersen is called to an archaeological dig to investigate mysterious runes on a seax hilt, but becomes fascinated by the strange burial of a 6th-century body alongside that of modern remains, setting off a chain of events where past and present collide.

Set against the backdrop of the French & Indian War, Passion’s Duty (Wheel Horse Press, June 17), by RWA Historical Romance Diamond Heart finalist, Lizzie Jenks, is a tale of duty and desire on New York’s wild frontier.

A Cruel Corpse (Holand Press, June 26), the first published novel of Reviews Editor Ben Bergonzi, takes place in Carlisle, northern England in 1747; a rebellion has been put down, but trouble persists for two soldiers in the government army: Jasper Greatheed is a man with a secret – as a ‘molly’ he could be hanged for sodomy; his friend is also living a lie – and Private Hayden Gray is in fact a woman, Grace Hayden. Their secrets unsuspected until now, they are part of the city garrison; when a vicious sergeant is murdered, Hayden comes under sharp suspicion, for her only alibi will wreck her masquerade, and if she is exposed, as her ‘dresser’ Jasper will also soon be unmasked. They set out to find the sergeant’s real murderer before time runs out – after all, the officer who is leading the official investigation has reason to hate Hayden.

Set in 1957 and 2018 Hollywood and Carmel-by-the-Sea, Meg Waite Clayton’s Typewriter Beach (Harper, July 1) is the story of an unlikely friendship between Leo and Iz—an Oscar-nominated screenwriter and a young actress whose studio intends to make her the new Grace Kelly if she can toe the line—and, sixty years later, a mysterious manuscript Leo’s granddaughter finds in a hidden safe in his Carmel cottage.

In Cathie Hartigan’s The Luthier’s Promise (Independently published, July 9), it’s 1595; Will promises to bring the celebrated, but wayward musician, John Dowland, safely home from Italy, but when love delays them, it is not only Will’s promise that’s in jeopardy, but also their lives.

In Catherine Kullmann’s latest Regency novel, Lord Frederick’s Return (Willow Books, July 22), after 18 years in India, Lord Frederick Danlow returns to England, where his plans to find a wife and make a home for himself and his motherless daughter are disrupted by a huge family scandal.

In Secretary to the Socialite by Amanda McCabe (Oliver Heber Books, July 22), set in the glittering world of mid-century America, Millicent Rogers is a woman ahead of her time—Standard Oil heiress, fashion icon, patron of the arts, wife, mother, lover—but behind the scenes, she harbors secrets of ill health and loneliness that only one person knows: her secretary Violet Redfield.

There’s comedy and tragedy in The Players Act 1: All the World’s a Stage by NYT bestselling author Amy Sparkes (Sword and Fiddle Publishing, July 29), in which a down-on-their-luck troupe of strolling players have one last chance to save their failing theatre company.

In When the Blues Come Calling (Level Best/Historia, Sept.), the fifth in Skye Alexander’s Lizzie Crane Jazz Age mystery series, it’s June 1926 in New York City; jazz singer Lizzie Crane is about to make her first record when the head of the recording company is poisoned by a drug used to treat syphilis, trapping her in a tangled web of music

industry chicanery and hidden agendas.

Julie A. Swanson’s North of Tomboy (SparkPress, Sept. 2) is a middlegrade novel set in 1973 about a child who feels more boy than girl and is frustrated that people act blind to that when—except for her stupid hair and clothes—it should be obvious!

The Nightingale of Bath by Thomas Messel (Aëdon, Sept. 8), set in late 18th-century England, follows the true life of celebrated singer Elizabeth Linley, who scandalises society by eloping with Richard Brinsley Sheridan, but manages to survive a turbulent marriage by championing the radical politics of the Whig party and the Prince of Wales’s Regency bid, before escaping to find love with the Irish revolutionary Lord Edward FitzGerald.

Angela Shupe’s In the Light of the Sun (WaterBrook, Oct. 7) is WWIIera historical fiction that follows the stories of two sisters, one in the Philippines and one in Italy, who find themselves caught up in the secrets, devastation, and intrigues of war – inspired by the true wartime experiences of the author’s mother and aunt, and by the life of her great-grandmother, who performed with Gran Compania de Opera Italiana.

From backstage to centre stage and theatres of war, Dance of the Earth by Anna M. Holmes (The Book Guild, Oct.) is a sweeping family saga set against the backdrops of London’s gilded Alhambra music hall, Diaghilev’s dazzling Ballets Russes, and the upheavals of the First World War, as Rose and her children, Nina and Walter, pursue their ambitions, loves, and dreams.

The Great Forgotten by K. L. Murphy (CamCat Books, Nov. 4) is the gripping tale of a little-known American disaster, the five men whose lives became intertwined that fateful day, and the woman who knew them all.

In Winterfylleth War: The Song of Artemis Book Two by Laura Gwendolyn Hill (Otterbeck Press, Dec.), Artemis is oath sworn to protect a princess; can she keep her safe when conflict between two kings turns their world upside down?

NEW PUBLISHING DEALS

Sources include authors and publishers, Publishers Weekly, Publishers Marketplace, The Bookseller, and more. Email me at sljohnson2@eiu. edu to have your publishing deal included. You may also submit news via the Contact Us form on the HNS website.

Author of Light to the Hills Bonnie Blaylock’s The Water Women, about mothers passing down to their daughters not only the skills of the ancient art of weaving sea silk in Sardinia, but generous love, deep pain of loss, and the freedom to be oneself, sold to Nancy Holmes at Lake Union Publishing for publication in summer 2026.

Songs of the Dead Road by Carolyn Newton, a sweeping saga that takes a shy piano prodigy, Ján Balik, from Polish high society in 1939 to the deprivations of Soviet prisons and the frozen outreaches of Siberia, and who, over decades of loss, composes elegant melodies to heal others’ pain while keeping his own trauma a secret, sold to Bloodhound Books (UK) for publication in February 2026.

The Cleopatra Code by Michelle Moran, a dual-timeline story set in the early 20th century and ancient Egypt, in which a brilliant female codebreaker and archaeologist discovers that Cleopatra’s sister’s writings are key to cracking enemy ciphers nearly 2000 years later, changing the course of World War I, sold to Susanna Porter at

Ballantine by Kevan Lyon at Marsal Lyon Literary Agency.

Shreya Ila Anasuya’s debut novel The Poison Palace, which looks at the myth of Alexander the Great through a feminist, Indian, queer lens, in which a young woman trained as a poisoner travels from India with her childhood friend to destroy the man threatening her homeland, sold to Tilda Key, fiction publisher at Sphere.

Rose & Renzo by Carolyn O’Brien, following a genteel and creativeminded young woman in the interwar era who finds herself living in Little Italy in Manchester, England, and gets involved in the antifascist movement there, sold to James Keane at Northodox Press for spring 2026 publication.

Manpreet Grewal, publisher at Juniper, HarperCollins UK’s new literary fiction imprint, acquired UK/Commonwealth (excluding Canada) rights to Fauzia Musa’s The Strangling Fig, a multigenerational saga and ghost story about Partition’s longlasting impact on one Muslim family in India, Pakistan, and the US, via agent Laurie Robertson at PFD.

American Nightmare, post-WWI-set fiction by Kelly McWilliams, about a young Black man, haunted by his best friend’s ghost, and hired by the NAACP to investigate lynchings in the South by passing as a white man, inspired by the life of civil rights activist Walter White, sold to Shannon Criss at Crown for fall 2026 publication by Michael Bourret at Dystel, Goderich & Bourret.

North American rights to Paula McLain’s next novel, Skylark, the intertwined stories of a young female artist seeking independence in 17th-century Paris and a medical student in WWII-era occupied Paris, sold to Peter Borland at Atria via Julie Barer at The Book Group, for publication in 2026.

Sofia Robleda’s The Other Moctezuma Girls, revealing the comingof-age love story about the last Aztec empress’s daughter, who undertakes a journey with two siblings after their mother’s death to discover her true will, sold to Alexandra Torrealba at Amazon Crossing via Johanna Castillo at Writers House.

OTHER NEW & FORTHCOMING TITLES

For forthcoming novels through mid-2026, please see our guides, compiled by Fiona Sheppard:

https://historicalnovelsociety.org/guides/forthcoming-historicalnovels/

COMPILED BY SARAH JOHNSON

Sarah Johnson is Book Review Editor of HNR, a librarian, readers’ advisor, and author of reference books. She reviews for Booklist and CHOICE and blogs about historical novels at readingthepast.com. Her latest book is Historical Fiction II: A Guide to the Genre

NEW VOICES

Debut novelists Brigitte Dale, Martha Jean Johnson, Sarah Landenwich, and Emma Pei Yin introduce readers to mysterious and intriguing characters and moments in history.

Brigitte Dale, author of The Good Daughters (Pegasus, 2025), first saw suffragette leader Emmeline Pankhurst’s name on a list of historical figures her high school teacher provided for an optional research presentation.

Dale explains: “In a crammed AP curriculum that focused almost exclusively on male figures in European history, Pankhurst was one of the few non-royal, regular women I had the chance to learn about. I soon discovered, though, that she was anything but ordinary. A woman who led marches of 250,000 suffragettes through London! Who traveled the world and went to jail and put her life on the line for the right to vote!

“I was so excited to present my research on Pankhurst to my classmates, until a blizzard blew in and school was cancelled. When we returned, the research projects were abandoned; we were racing to finish the AP curriculum, and unfortunately, Emmeline Pankhurst and the suffragettes were among the many women and people of color deemed not a priority by the test-makers. I never got to tell my classmates all I’d learned, and I felt the injustice of this erasure.”

It was a few years later, she says, that “my college class on women’s history reintroduced me to Pankhurst and her Women’s Social and Political Union. By then, I was fascinated with the suffragettes whose motto, ‘Deeds Not Words,’ exemplified their commitment to breaching the traditional bounds of Victorian propriety in order to make their bodies the site of their activism, engaging in public marches, protests, prison sentences, and hunger strikes in their efforts to win the right to vote.”

Dale was in graduate school when she first considered transforming her historical research into fiction. “In prison, women often endured

terrible conditions, lacking the rights of political prisoners, and suffering hunger strikes and forced feedings. I found it compelling that there were women on both sides of the bars—not just the incarcerated suffragettes, but also the women working in the notorious Holloway Prison. I realized I wanted to tell the story of both those groups of women, and how their lives would intersect. This felt like my chance, finally, to tell the suffragettes’ story to a wider audience.”

As Dale points out, “There was significant stigma associated with the word ‘suffragette,’ which was originally an insult to belittle women activists, though later reclaimed as a term of pride. I wanted to explore the lives of women from all different backgrounds for whom associating with the suffragette campaign represented a great risk and also, ultimately, meaningful freedom and empowerment. My characters are aristocrats and working class, ex-pats and students. They represent the real diversity of the movement, and the different kinds of sacrifices these women had to make.”

The academic research she carried out helped her to populate the world of 1910s London with accuracy. “But ultimately, writing this as fiction helped me understand the suffragettes on an emotional level. Their story is not just political—and more relevant than ever— but it’s about friendship, chosen family, and incredible perseverance. Women’s stories should never be relegated to the footnotes of history, and I’m gratified that through fiction, I am able to shine a light on the story of the suffragettes.”

The idea for Sarah Landenwich’s The Fire Concerto (Union Square, 2025) started several years ago. “I had the idea to write a story about three female pianists—one in the 19th century, one in the early 20th, and one in modern times—connected by their pedagogical lineage. I have a background in classical piano. This idea of ‘musical ancestry,’ tracing the line of teachers from which you descend, was familiar to me from the musical world, but I had never seen it explored in literature.”

At its first conception, Landenwich “thought the novel would be a braided narrative,” she relates. However, she “quickly realized that a book with three different time periods and three separate stories would be too long to ever get published. So, I started searching for a different way to tell the story. One of my favorite books is A. S. Byatt’s masterful novel Possession.” She studied Byatt’s structure—the scholars in the present investigating a thrilling mystery of the past through texts and historic artifacts and thought she would write the Possession of classical music.

“I began working on The Fire Concerto in earnest at a time of incredible personal upheaval. I had just become a mother and had also developed some concerning neurological symptoms that led to a difficult year of doctor’s visits and an anxious search for a diagnosis. Holding the desperate love I had for my baby alongside the fear that there may be a future when I couldn’t care for her was heartbreaking. I’m happy to say that I am now completely recovered, but it was an existential time, to say the least. I wrote all of those feelings into the lives of my characters, many of whom suffer from an injury or condition that prevents them from pursuing the life they wish to live.”

For Landenwich there is “an aphorism in writing that you must write the novel only you can write. I don’t know if I necessarily believe in it. But I do think this book is a unique outgrowth of me. I bear no resemblance to the characters or their experiences, but my own passions, interests, heartbreak, and hope are on every page.”

Brigitte Dale

Sarah Landenwich Emma Pei Yin

Martha Jean Johnson

Photo credit: Callalily Studios

Photo credit: Chelsea Mazur

Photo credit: Chelsea Mazur © 2024 Kannika Afonso

Like countless others, Martha Jean Johnson, author of The Queen’s Musician (SparkPress, 2025), has been fascinated by Anne Boleyn since she was young. “Henry VIII adored her, and then, incredibly, she ousted the reigning queen. A few years later—after she ‘fails’ to give birth to a son—the king decides to have her killed.” These events, Johnson stresses, “changed history,” but adds, “There’s also a human mystery here. How did the king’s love turn into hate? Was any other ending possible? Historians and Anne Boleyn’s considerable fan base still wrestle with these questions.”

The Anne Boleyn story is, for Johnson, “one of kings and queens, dynastic families, international rivalries, and powerful, titled individuals. But at the center of the drama was a young man from a poor family, a popular musician but nothing more.

“Mark Smeaton was one of Henry VIII’s favorite players. Historical records document the gifts and honors he received from the king. Anne Boleyn’s brother gave him a book, and the musician wrote his name in it ... Suddenly, he was taken to Thomas Cromwell’s house and accused of being Anne Boleyn’s lover. He confessed—a confession that was almost certainly coerced. Two days before Anne Boleyn’s execution, he was beheaded, probably at the age of twentythree or twenty-four.”

This handful of facts prompted both Johnson’s curiosity and sympathy, “How did this young musician rise to what must have been the height of success in his day? What was he like? How did he become entangled in Henry VIII’s machinations? What is it like to be falsely accused and have no means to defend yourself? What is it like to lose all you have worked for in the space of a single night and day?”

Johnson feels that “compared to others in this saga, Mark Smeaton seems more like most of us.” She explains: “He’s the commoner, the employee, the one who tried to better himself. He wasn’t powerful. No one addressed him as ‘sir’ or ‘my lord’. He was only talented. I wanted to imagine and tell his story.”

When Sleeping Women Wake (Ballantine/Quercus, 2025) by Emma Pei Yin, “began the same way a low tide pulls back before a storm,” says the author. “It started with my grandfather’s voice, matter-offact and unadorned, recounting his childhood during the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong. I was a child myself then, sitting beside him in the courtyard of our ancestral home in Tai Wo, half-listening as he spoke of soldiers and scarcity, of hunger and hiding, of neighbours who disappeared. I listened, not because I understood, but because I loved him. It wasn’t until much later that I realised the

grief braided into his stories.

“I lived in Hong Kong during high school, and I moved through the city like it was any other modern place—past the pillboxes hidden across the New Territories, past military tunnels half-swallowed by banyan roots. I rode buses through Wanchai, not knowing the same roads once rumbled with army convoys. I walked through Kowloon and Central, past colonial buildings that had once held prisoners. These places, that were folded into daily life, were so ordinary to me then, unremarkable almost.”

But when Yin began writing this novel, “the past came to life. Every street corner became charged with historical memory, and I saw it all differently. I saw what had been endured.

"My grandfather is Hakka and always spoke with pride about the East River Column, where many resistance fighters emerged from villages like ours. But it was the silence of my grandmother that stayed with me. She was a baby during the war, too young to remember, yet she lived in its long shadow. She never told stories, and I began to wonder what her silence held.” It was at that point that, for Yin, “that wondering became a novel.”

When Sleeping Women Wake is Yin’s “attempt to give voice to those who endured quietly,” she says, “especially women whose histories were rarely recorded. I wanted to honour their survival—not through spectacle, but through care, through persistence, through love held amidst fear. Writing this book was not just an act of imagination. It was a homecoming. And a long overdue listening and acknowledging of family stories.”

WRITTEN BY MYFANWY COOK

Myfanwy Cook is an Associate University Fellow. She creates HF writing workshops and is currently engaged in highlighting the 200th anniversary of passenger rail transport in the UK. Contact (myfanwyc@btinternet.com) if you uncover debut novelists you would like to see showcased

HISTORY & FILM

The Devil You (Might) Know: Sinners

I love horror movies, especially the classic Hammer or Universal horror films featuring the likes of Christopher Lee and Bela Lugosi. My Saturday evenings are usually spent watching campy flicks like Dracula’s Daughter or Curse of the Werewolf. For me, the best ones have great origin stories explaining the monster’s motivations.

Horror is such an intriguing genre! Monsters drive the exploration of taboo topics. Vampires serve as a metaphor for sex. Frankenstein deals with science gone awry. Mummies and ghosts speculate on life after death. Werewolves are all about the wild and untamed beasts dwelling within us all. Horror is a safe space to experience these things, which is why I love Ryan Coogler’s Sinners. The movie’s horror flows organically from the historical context in which it is set. Neither overshadows the other. And with a variation of the monster’s motivation, a fresh new take on vampire films emerges.

Horror flicks written, directed, produced, and/or featuring Black actors are gaining traction. Though I’m not a fan of the blaxploitation films of the 1970s, Blackula, starring the late Willam Marshall (who also happens to hail from my hometown of Gary, Indiana) is a horror favorite. Aside from the awe of seeing a Black vampire, the origin story was different: Mamuwalde, an African prince, and his bride visit Count Dracula to stop the slave trade in the 1700s. Dracula, of course, refuses, and turns Mamuwalde into a vampire. The rest of the story takes place in then-contemporary Los Angeles, following the same premise of the vampire eating his way through the populace while seeking to reunite with the reincarnation of his lost love.

Black horror also tends to skew a bit to societal issues affecting Black people that are almost as terrifying as the monsters shown on the screen. Count Dracula in Blackula is not only a vampire, he’s also a slave trader. Sinners uses the vampire genre as the canvas to address both fictional and societal horrors.

Sinners is the story of Elijah and Elias Moore, infamously known as the Smokestack Twins (one is called Smoke; the other is Stack) in their hometown of Clarksdale, Mississippi. It is set in 1932 during Prohibition, the Great Depression, and the Great Migration, the time when many Black Americans left the Jim Crow South to find opportunities in the north and west. My grandparents did the same,

leaving for midwestern steel mills. The Clarksdale depicted in the film, according to friends, is just as their grand- and great-grandparents described: barefoot and pregnant sharecroppers picking cotton under a blazing sun. Blues music and attending church, salves for the farmers’ souls and spirits. Automobiles and horse-drawn wagons crowd the wide dusty road in town. And of course, there’s the Klan. The Smokestack Twins did the opposite, returning south after a stint in Chicago, and laden with a suspiciously large supply of money and booze. Better to be around the devil you know, the twins offer, as the reason why they came back. Their goal: make money using liquor stolen from the Mob to open a juke joint. With a suitcase full of money, the twins purchase a sawmill from a white man (with a promise to shoot any of his Klansmen friends who cross onto their property). Then Smoke and Stack get to work. They employ an ensemble of friends and family to assist with the set up, including their cousin, Preacher Boy, who longs to leave the South for a chance to play the blues on a guitar he believes belonged to the twins’ deceased father.

Both Smoke and Stack are played by Michael B. Jordan (Creed, Black Panther) who successfully delineates the two on the screen through costuming (one is accessorized in red while the other dons blue), demeanor, and speech. Smoke presents as the leader and older brother whose mind is set on business and protecting his foolhardy twin. When some of the sharecroppers in the juke can only pay with wooden nickels, Smoke insists on cold hard cash. Stack, on the other hand, is the slick-talking one with a smile on his face and a ready quip on his lips. He tempers his brother’s anger about the wooden nickels, reminding him that the farmers need this brief respite from the cotton fields.

The twins’ disparate personalities are defined by their interactions with the people they collect for the juke. Smoke demonstrates his business savvy when he teaches a young girl to negotiate over how much he should pay her for watching his truckload of booze. He haggles over prices with the Chows, a Chinese-American family who run a couple of general stores in town. Without a second thought and in full view of onlookers, Smoke shoots two men attempting to steal his truck. His tough exterior cracks just a bit when he reunites with Annie, a Hoodoo practitioner and the mother of his deceased child, who agrees to fry fish at the juke.

In a different part of town, Stack and Preacher Boy secure the labor for transforming the mill. Veteran actor Delroy Lindo plays Delta Slim, a hard-drinking blues musician who agrees to join them in exchange for a bottle of ice cold beer and a promise of more. Stack’s jocular personality and dirty innuendos scare up a few more hands from the fields to clean and set up the place. Stack is also avoiding heartbroken Mary, a married white woman whose half-Black mother cared for the twins after their mother died. Just like with Smoke, Stack’s interaction with Mary shows the audience a different, more serious side of him: he struggles with shunning the woman he loves in order to protect her from those violently opposed to interracial relationships at the time.

A brief interlude between the preparation and opening of the juke joint introduces the audience to Remmick the vampire. As the sun begins to set, his smoldering body drops from the sky like a lead balloon in front of a cabin in the middle of nowhere. He begs the cabin’s inhabitants to save him from a group of Choctaw vampire hunters. When the hunters subsequently arrive at the cabin, their warning to not let the stranger in is too late. With this, some vampire lore

is retained. The vampires can’t be in sunlight. They must be invited inside. Their bite/saliva turns their victims into vampires. The difference in this iteration is that blood is not what draws Remmick and his two new converts to the juke. It’s Preacher Boy.

In what I believe to be the most mesmerizing part of the film, the blues Preacher Boy plays summons the spirits of musical ancestors. Shadows of African drummers, old school hip-hop artists, Chinese folk and Native American tribal dancers appear among the juke’s patrons. But Preacher Boy’s power also summons the vampires. Remmick is a collector of memories and talents. His desire to possess Preacher Boy’s musical gift is a nod to the historical appropriation, and at times outright theft, of Black music. When the twins heed Annie’s warning and refuse entry to the vampires, Remmick uses his Irish background (though there are some hints that he is a much older vampire) to try and convince everyone they are on the same side when it comes to American oppression: the enemy of my enemy is my friend, so to speak. Yet it is one twin’s weakness that ushers the monsters inside.

rubbed elbows with the Chicago Outfit, alluding to the provenance of their suitcase full of money and truckload of quality booze, not the cheap stuff brewed in bathtubs at the time. Their devilish reputation precedes them. But there are reasons for their actions, and the audience feels justified in rooting for their redemption and/ or success, even before the vampires arrive. Much like the George Clooney character from Robert Rodriguez’s From Dusk Til Dawn, the Smokestack Twins come into the movie with heavy baggage and then become the heroes needed to fight off the actual evil in the movie. Whether or not that evil is solely the vampires is debatable.

Surprisingly– or maybe not– the title of the movie applies to more than just the vampires and the Klan, who make their expected appearance near the end of the film. Preacher Boy eschews joining his father in the pulpit (hence his nickname) for a chance to play at the juke. Delta Slim is an affable alcoholic. Pearline, who caught Preacher Boy’s eye, and Mary cheat on their husbands in the back rooms of the juke. Bo Chow is insinuated as a gambler.

With all that, can the term antihero can be applied to the Smokestack Twins? Antiheroes are deeply flawed main characters we’re supposed to root for. They straddle the line between right and wrong. In their minds, the ends justify the wicked means they are engaged in to accomplish their goal. But the dirt the twins are known for happens off-screen and in their past. The audience is led to believe the twins are bad, that there is an ulterior motive to opening the juke joint. But without spoiling the movie, I wonder whether the ending makes them good or still bad, but justified.

The Smokestack Twins aren’t completely bad, though. The pair served in World War I. Given their actions near the end of the movie, they couldn’t have been cooks or truck drivers, roles Black soldiers were mostly relegated to. Though it’s not mentioned in the film, I like to think the twins were Harlem Hellfighters, the 369th Infantry Regiment of the New York National Guard who spent more time on the front lines than any other American regiment during the war. Henry Johnson, a real-life Harlem Hellfighter, was one of the first African-Americans to earn France’s highest award for valor, and was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor. I wonder if Smoke’s confrontation with the Klan is an homage to Johnson and the Hellfighters. Or maybe I’m trying to impute some goodness onto them.

But that’s just one bright spot. The twins killed their father. They

Given the time period and setting of Sinners, there is a lot of history and themes to unpack that can’t fit in this space. Even the lyrics in the two musical portions– one by Preacher Boy and the other by Remmick– are metaphors for something much deeper than what’s presented on the screen. This horror movie is not solely a vampire flick touching on the usual vampire tropes and themes. Contrast this to the long-awaited (third?) remake of Nosferatu, which was visually stunning, but basically the same story as its predecessors. One viewing of Sinners isn’t enough to catch everything the film slips to the audience. Though the movie is still fairly new, it should be added to the canon of excellent horror storytelling.

WRITTEN BY MICHELLE MCGILLVARGAS

Michelle serves as the Registration Chair for the HNS North American Conference and is a Board member of Midwest Writers Workshop. Her debut novel, American Ghoul, was released in 2024 by Blackstone Publishing.

GREECE & ROME

Mythology, Legends, and Novels

Why are we so fascinated by the ancient world? Over eight million people climb up to the Parthenon in Athens every year, so many that the Greek government plans to cap visitor numbers. Five and a half million come to stare at the exhibits in the British Museum, where just over half the galleries are devoted to Ancient Greece and Rome, most notably the Elgin Marbles.

Novels about ancient Greece and Rome currently attract considerable attention, perhaps because of the richness and variety that these cultures present. The history of Greece and Rome was recorded by contemporary writers from Herodotus to Tacitus. The ancient world also created its tales and legends, from the Trojan War to the Golden Fleece or the love of Dido and Aeneas. In addition, there is a complex and interlinked mythology that includes stories of gods, goddesses, Titans and heroes from the creation of the world to the love affairs of Zeus, the journey to the underworld, the Labours of Hercules and the founding of Rome. They also provide an important literature that reinterprets and occasionally makes fun of those legends and myths: from the Odyssey to Euripides’ Medea to the Lysistrata of Aristophanes.

All this has been further reinterpreted in our own culture in the works of Shakespeare (Coriolanus, Troilus and Cressida), Marlowe, BulwerLytton, and many others. It now forms the basis for a new round of reimagining.

One tradition draws on history and seeks to engage the reader with the reality of the ancient world, so far as we can access it. A leading author is Conn Iggulden, whose novel Tyrant (Michael Joseph/ Pegasus, 2025), the successor to Nero (2024) was published in June this year. In a recent interview, he compares the timeline of history to the bones of Richard III dug up in a Leicestershire car park in 2013. That is just a starting point; his readers need to engage with the history he recounts, to “feel the breeze in their hair, hear the promises they know will be broken” and grasp what it felt like to see Rome burn. The defining characteristic of people, he believes, is empathy. Modern readers will participate in the experience of real people from the past finding their way in a world alive to them but history to us, and that is what he provides. In his series on the Persian wars against Athens he seeks to make the reader understand what it was like to fight, to be a refugee, to win and to lose in that war.

Marguerite Yourcenar’s Memoirs of Hadrian (1954) takes a major historical figure, the emperor who held to Roman Empire together through some of its most bloody confrontations, and helps us understand what duty meant to him and how his tragic and controversial love affair with Antinous shaped his life.

These novels place us in the world of the Greeks and Romans, assuming that they were people rather like us and had the same beliefs and values, that they would react in the same way as we would if transported to Nero’s court. A different approach imagines the events of the past from the point of view of those directly involved, from the perspective of men who believed that duty and the endless quest for glory should govern men’s lives, while women were incapable of making the choices that men did, and slaves were, as Aristotle puts it, no more than a kind of intelligent animal.

The consciousness of Greeks and Romans was shaped by legends and myths very different from our traditions. What if you believed that your world was inextricably enmeshed with the supernatural, your life was ordered by gods and goddesses with overwhelming power but the lusts and desires of squabbling teenagers, or that you owed it to your parents or your city to revenge yourself on another people who had never done you any harm?

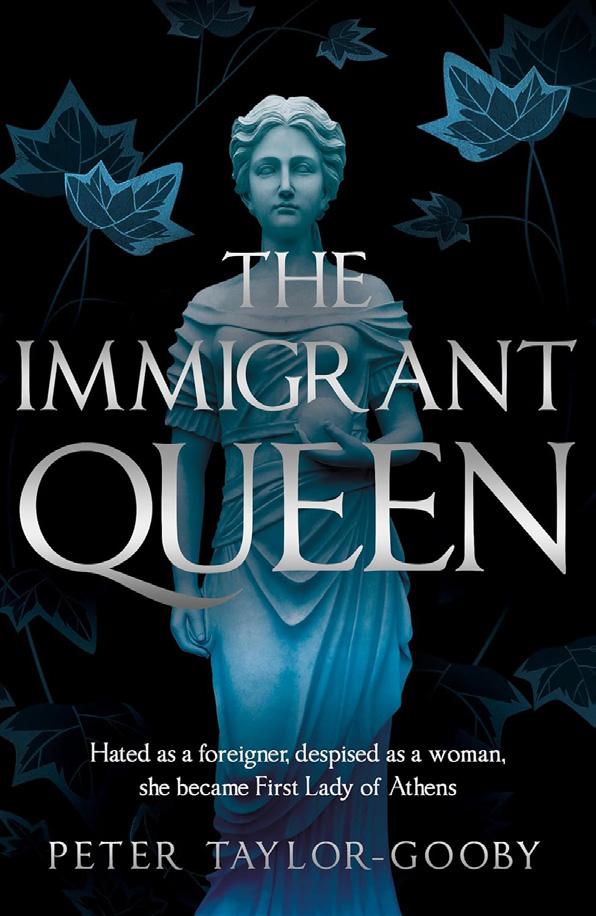

This is the world of Mary Renault, who wrote pioneering novels telling, for example, the tale of Theseus and his rise to the throne of Athens (The King Must Die, 1958 and The Bull from the Sea, 1962). Similarly, Pat Barker’s powerful retelling of the Trojan Wars from the point of view of the women who are bit players in the originals imagines how Briseis, sex-slave of Achilles; Electra; Clytemnestra; Cassandra; and her servant Ritsa (The Silence of the Girls, The Women of Troy and The Voyage Home, Hamish Hamilton, 2019-2024) might have understood their role in a war started by men, how they were victims in that war but succeeded in changing the outcomes in radical ways. My novel The Immigrant Queen (Troubador, 2024) portrays the rise of Aspasia, lover of Pericles, from her inferior status as a woman and an immigrant, to her triumph as the only woman invited to join Socrates’ circle, the founder of the first academy for women in the

WHAT DID these people value and fear? When we engage with voices from the past, we connect to our shared human history.

city, a respected and widely-quoted author and as a celebrated wit.

A third approach takes mythology seriously as more than legend and uses it as a resource, alongside history to include goddesses and gods among the characters and as central to the plot. This enables the author to use the supernatural to involve the reader in what might have been the experience of people in that world so close to and so very different from ours.

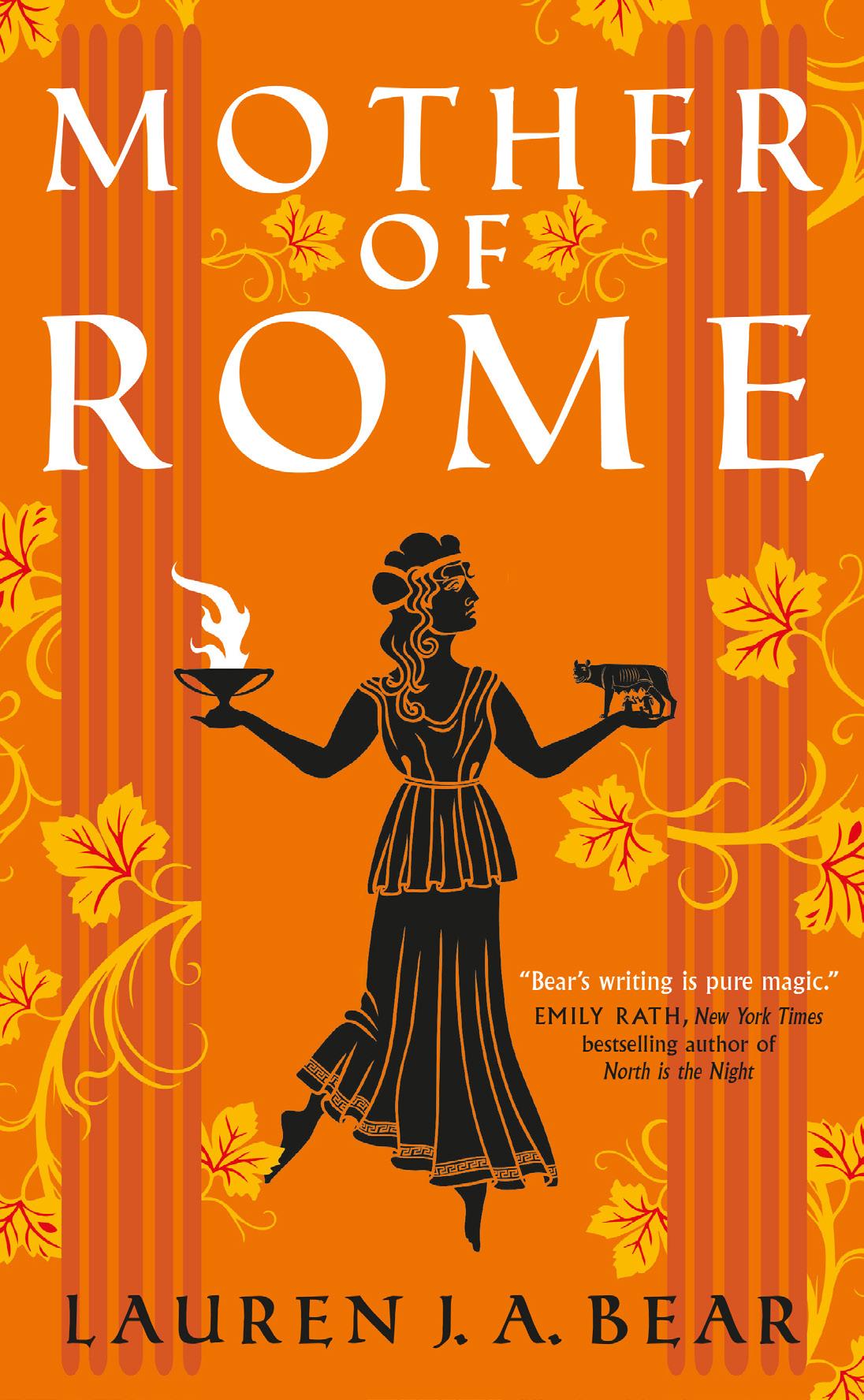

One example is Lauren J. A. Bear’s recent second novel, Mother of Rome (Titan/Ace, 2025), which tells the story of the foundation of Rome from the viewpoint of Rhea Silvia, the mother of Romulus and Remus, but imagines that Rhea survives when her father is forced from the throne. She becomes half-spiritual herself, watching over her children and the creation of a great city with the help of her cousin Antho. The novel interweaves mythology (is it really the god Mars whom Rhea makes love to in defiance when her uncle compels her to become a Vestal Virgin? Is the god of the Tiber ever-present in her life?).

Lauren explains how she understands the importance of the stories of former civilisations: “Of course, they entertain, and that’s important, and sometimes they teach a moral, but perhaps most essentially, they also reveal the soul of our ancestors. What did these people value and fear? When we engage with voices from the past, we connect to our shared human history. We get this magnificent opportunity to commune over time and place.”

This is an opportunity she takes up with great success. But she and many of the authors who write about the ancient world seek to do more: She agrees with Conn Iggulden: “Any time a reader can connect to what a fictional woman feels thousands of years ago is a good thing. The ultimate goal of fiction, after all, is to foster empathy across humanity.”

The problem lies in creating “a character for a modern reader that still feels authentic to the novel’s setting ... There’s a scene early in the book in which Numitor invites Rhea into his room, but she must stand to the side while the men discuss business. Every woman can relate to that feeling of not being invited to the table. Antho is forced into a marriage she does not want out of filial duty. I think many modern readers can relate to a life under oppressive parental expectations.”

“The magic of retellings … lies in the manipulation of point of view. Modern readers care about perspective. They want to know what women did, how the enslaved felt, what the villains thought, etc… Writers today get to subvert the tales we have been told, to fill in the gaps and cracks.”

It is this subversion of the dominant traditions in the culture of the ancient world that is at the heart of what many of those who seek to reimagine the ancient world are doing. In Mother of Rome, Lauren wanted to give the women character and agency, but to do so in ways that felt authentic. She wanted to “honour the setting…” For example, “neither of these women are trained in warfare, so how can they demonstrate their strength? ... They utilize what they have available. For Antho, it’s her docile reputation. She performs her Latin duties perfectly as a cover for her rebellion. Rhea embraces her primal, essential energy – the animal within. Neither of them

has to deny their femininity to achieve their goals; instead, they expand the definition of what it means to be a woman. I find that more compelling than just giving them a sword.”

And then there are the universal experiences: love and death. “Rhea mourns. She lusts and longs. She struggles against a patriarchal system that would tell her what she can and cannot do with her body. These are ancient struggles; they are modern struggles.”

The ancient world offers a richness to reader and writer because we know that it embraces mythology and legend alongside history. Different authors approach the challenge of connecting the reader with people who lived by different rules in a different time from several directions: an immediate engagement with the choices and experiences that are contained in history as Conn Iggulden and others pursue; an enriching of that world with myth and legend from the character’s point of view as Mary Renault and I have; or a full-blown interweaving of myth, legend and history as in the world created by Lauren Bear. The past is a distant country and people lived differently then, but there are many ways in which it can inform and enhance our own reality.

REFERENCES

1. Conn Iggulden

Q&A Facebook Interview, 30 April 2025.

WRITTEN

BY PETER TAYLORGOOBY

Peter is an academic, social commentator and author of The Immigrant Queen (Troubador, 2024), the true story of Aspasia ,who rose to become the only woman in Socrates’ circle, the founder of Athens’ first academy for women, a philosopher in her own right and the lover of Pericles.

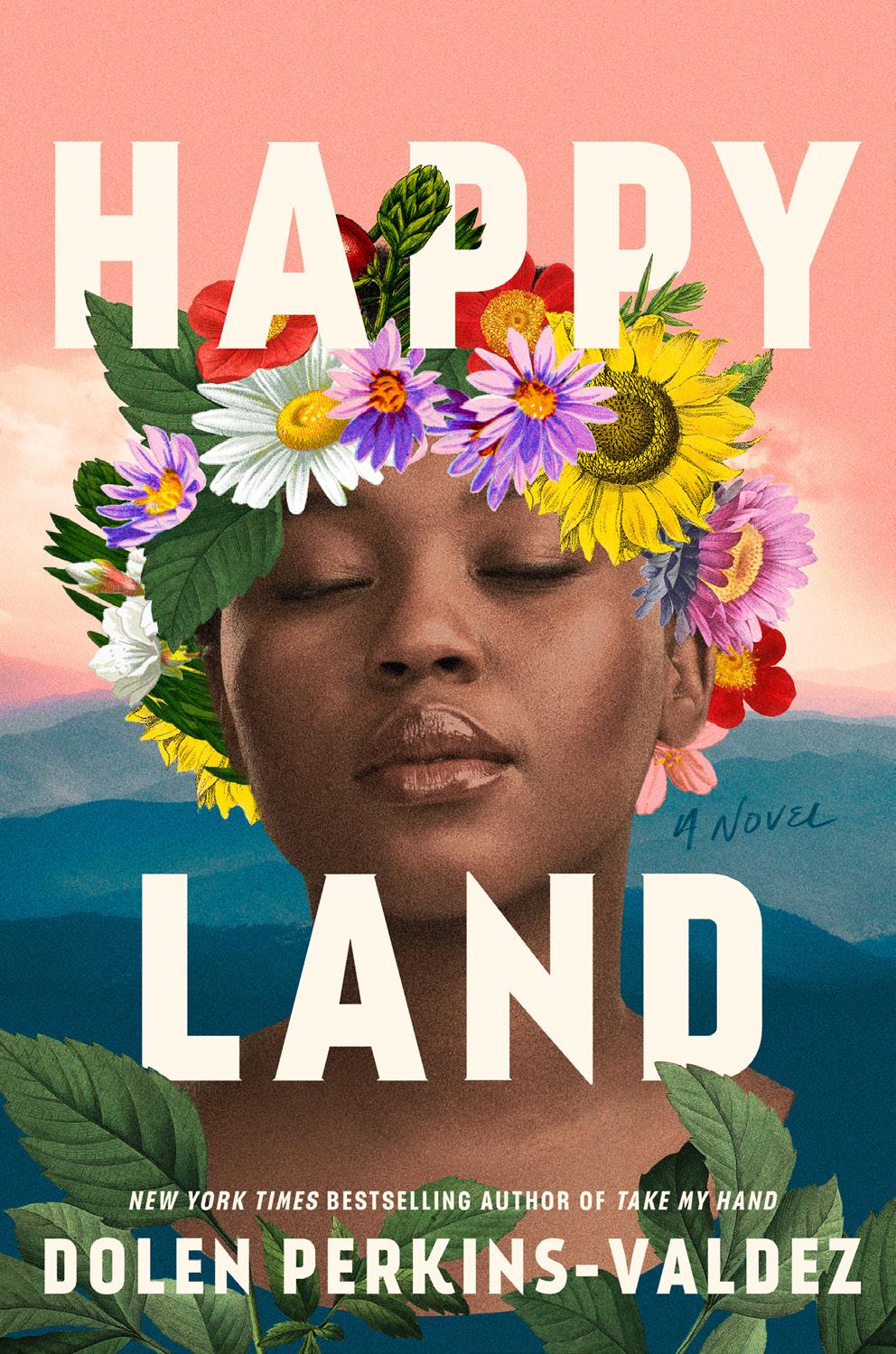

HOPE & THE HAPPY LAND

Two novels have recently been published which highlight an important event in history that has been lost and forgotten with time: The American Queen by Vanessa Miller (Thomas Nelson, 2024) and Happy Land by Dolen Perkins-Valdez (Berkley, 2025). Both novels tell of a group of former slaves who established their own kingdom – the Kingdom of the Happy Land. These remarkable people had dreams of a life of peace and happiness away from the violence and upheaval brought on by Reconstruction following the American Civil War. Much like Moses leading his people to the promised land in the Bible, William Montgomery, a freed man with a vision, led the group into the Appalachian Mountains of North and South Carolina to establish a community with a motto of “one for all, and all for one,” one modeled after their African tribal heritage. This kingdom was also distinguished in their choice to designate a king and queen as their rulers.1

Historians differ in opinions as to where these freed people originated – Mississippi or South Carolina – with each origin represented in each novel. In Miller’s The American Queen , the group of about 50 set out from the Montgomery family plantation

in Mississippi, with their number swelling to 150-200 by the time they settled on land in Henderson County on the North and South Carolina border.2 The group had no set destination in mind in which to settle; by faith they would find their home. In PerkinsValdez’s Happy Land , a handful leave South Carolina to make the shorter journey of about 60 miles to their promised land. William Montgomery apparently had knowledge of where they were headed since he seemed familiar with the area, possibly from his days as a drover.3

In The American Queen the Montgomery Plantation owner, William’s father, moved his household and slaves from South Carolina to Mississippi before the war, so the freed men left from Mississippi. Miller states, “I do believe they once lived in South Carolina. The evidence for that is that we know Robert Montgomery’s daughter, Elmira, was born in South Carolina. However, the Happy Landers themselves informed the community around them that they had arrived from Mississippi.” Sadie Smathers Patton, a local historian, provides the first written account in 1957 in a pamphlet, The Kingdom of the Happy Land, where she interviewed Happy Land descendants. Patton asserts they were from Mississippi.1

Perkins-Valdez addresses this origin discrepancy. Sadie Smathers Patton’s account “went largely uncontested for over sixty years. Some of her assertions were well-researched. She interviewed kingdom descendants and those who remembered the settlement. Other assertions in her pamphlet were imaginative, such as her insistence that the Kingdom folk traveled to North Carolina from Mississippi. I was surprised that for decades no one checked the archives to verify her account. Working collaboratively with Hendersonville residents Suzanne Hale and Ronnie Pepper, we found the archival documents that clearly confirm the early Kingdom inhabitants originated in Spartanburg County, South Carolina.”

Whether they came from Mississippi or South Carolina, they had one goal in mind – to find a place where they were welcome and they could live in relative peace, safety, and obscurity – a refuge from the Reconstruction Era violence and persecution. Miller says, “When I drove into the Appalachian Mountains to see this land… we had to drive on this one lane, unpaved road. On either side there was nothing but trees for a mile or more… Then there was this whole expanse of land before our eyes. So, I think the Happy Landers intentionally left that plot of land as you drive into their land undeveloped so they could stay safe in their hidden gem.”

Both novels portray the kingdom around the core historical facts. William and Louella were appointed king and queen; later Robert steps in as king after William’s death. The group settled on the lands of Oakland Plantation owned by Colonel John Davis, who died in 1859. Following the war, John’s widow, Serepta, was left with a deserted plantation, derelict slave quarters, a crumbling mansion, and a struggling stagecoach inn. When the group arrived, they made an agreement with the penniless widow to provide the manpower to restore and maintain her buildings and property, and help operate the inn in exchange for land to set up their community. They also cleared the trees on Serepta’s land, and were allowed to sell and use that lumber in the building of their homes. Each member was assigned a plot of land to build their own home; meanwhile, they lived in the former slave quarters. Some of the members worked for wages in the local area, while many had

I WAS FASCINATED by the fact that after being enslaved, William could still see the king in himself and a Queen in his wife, Louella.

specialized skills such as shoe making, masonry, carpentry, sewing, etc., that provided services and products inside and outside the community. Their popular Happy Land Liniment was produced and sold. Everyone contributed to the good of all in this socialistic society. The earnings of everyone were deposited in a treasury and distributed according to the needs of each of the Happy Landers, even saving enough money to eventually buy the land they settled on from Serepta.1

Miller and Perkins-Valdez each build their own fictional stories to fill in the missing pieces and flesh out characters lost to time. They imagine the roles differently that the Montgomery brothers play in Louella’s/Luella’s life, but Queen Louella/Luella is the one who exerts a defining influence. This is her story of her vision for her people, and her leadership stands out as instrumental and invaluable in building and leading her community.

The American Queen begins in 1864 after Emancipation. Through Louella’s eyes, Miller lays a foundation for the story, showing the violence, hardships, and the obstacles they faced in Mississippi and what instigates their odyssey. Louella’s father, Samual Bobo, instilled in her his vision of freedom. She still feels the smothering bonds of slavery and wants desperately to make a new life beyond the plantation. She marries Reverend William Montgomery. William, although the son of the plantation owner and his slave, was fortunate to receive an education. William’s brother Robert could pass as white. He lived as a free man and owned his own land, including slaves; he joins the Happy Landers. William and Louella are the driving force in leaving Mississippi and establishing the Happy Land.

Happy Land is told in a dual timeline in which Nikki, a 40-year-old woman, is the main character in the contemporary storyline. She is summoned to visit her grandmother, Mama Rita, who lives on the land of the former Happy Land Kingdom and wants to impart that legacy to Nikki before she dies. Perkins-Valdez says she wanted the contemporary story to show why this story matters now and how it impacts Nikki’s life today. Nikki is the descendant of a queen, and knowing the story of where she came from changes her.3 In answer to why Perkins-Valdez chose a dual timeline to tell her story, she says, “I wanted to ask this question: why is it important that we know about this little-known history? Why does the kingdom matter in 2025? I created a contemporary storyline to probe that question, to understand the significance of this lineage and history. Once I started writing Nikki’s story, I fell in love with her. She reminded me so much of myself.”

Researching Black history is challenging because it was primarily oral tradition that kept their histories alive. The only documentation during this time was through various public records. When I asked Vanessa Miller her barriers to research, she said, “anyone who understands history in America knows that Black people were not thought of as whole humans during slavery, and therefore most of the information you would traditionally find on other people, is not readily available for most enslaved people. So, I was not able to trace down certain information on the people who lived in the Happy Land before slavery ended.” Miller goes on to say, “I was fascinated by the fact that after being enslaved, William could still see the king in himself and a Queen in his wife, Louella. The simple fact that they thought to build a kingdom rather than a community was beautiful to me.” Also, she was surprised by “the amount of

tragedy Queen Louella Bobo Montgomery dealt with in her lifetime, but still was able to lead a group who needed her to be everything she was for them.”

Dolen Perkins-Valdez “was fascinated by the audacity and sheer ambition of the kingdomfolk,” she says. “They walked up that mountain and boldly proclaimed themselves royalty while building a new life. Louella was especially remarkable because she led at a time when it was uncommon for women to lead, own land, and develop a successful product, the Happy Land Liniment.” It was important to her to show the positive aspects of their story. “In my work, I tried to focus less on the violence they encountered and more on the brilliance of their communal strategizing and desire for land ownership… This is about a community of people intent on rebuilding their families, accumulating wealth, educating their children and creating a space of safety and refuge. When we think of the lives of Black folks during Reconstruction and post-Reconstruction, we often only see them through the lens of white mob violence… But there was so much more to the story than that.”

The Kingdom of the Happy Land survived until the turn of the 20th century, and today very little physical evidence remains. It has been local historians who have worked to keep the Happy Land story alive, and now we have the remarkable novels The American Queen and Happy Land to spread the word through fiction.

REFERENCES

1. Izard, M. Craver (2021, February 6). African-American history in Henderson County, Part One.

2. Brown Girl Collective. (2024, March 4). Interview with Vanessa Miller [video]. YouTube.

3. Brown Girl Collective. (2024, May 19). Interview with Dolen Perkins-Valdez [video]. YouTube.

WRITTEN BY JANICE OTTERSBERG

Janice Ottersberg is an HNR Reviews Editor and a long-time reviewer for the magazine.

FOR QUEEN & COUNTRY

BY DOUGLAS KEMP

The espionage fiction of C.P. Giuliani

Clara Giuliani, or C.P., is very much the Renaissance woman, which is perhaps appropriate as she is Italian, living in the delightful city of Mantova. In addition to being a writer of historical fiction, she is a playwright, teacher, translator, editor and longstanding reviewer for the HNS. Her latest novel in the Tom Walsingham series, A Matter of Blood, was published earlier this year (Sapere, 2025). They are set in 1580s England and mainland Europe. Tom is cousin to Sir Francis Walsingham, principal secretary and spymaster to Queen Elizabeth, and acts as his confidential investigator.

Clara spoke about how she became fascinated with the arcane world of espionage in the Elizabethan court: “I think I can lay the blame at Christopher Marlowe’s door. Some twenty-five years ago I became the tiniest bit obsessed with Marlowe’s work and discovered what an interesting life he had (perhaps) led before coming to a gruesome end at the age of twenty-nine. I read a good deal about him – both fiction and non-fiction – and two books in particular made me want to fictionally explore his life and world. One was Anthony Burgess’s A Dead Man in Deptford, with its gorgeous language and vivid telling. That is where I first came across Sir Francis’s young cousin, Thomas. The other was Charles Nicholl’s The Reckoning, an intricate, detailed study following Marlowe’s traces in the espionage world. I can’t say that I agree with all of Nicholl’s conclusions, but he sparked off my fascination with Sir Francis and his work. I find the field [of espionage] fascinating, with its combination of painstaking work, deceit, happenstance and danger. Rather like chess with frightfully high stakes, a certain amount of cheating, and a sense that the rules can change at any moment – or, at least, this is the impression of 16th century intelligence I gathered from reading authors like Nicholl, Stephen Alford, John Bossy.”

Clara 's novels contain a wealth of research and have a reliable sense of authenticity for the reader, with a sound historical background. She spoke about her research, sources, and methods: “All I can say is, blessed be the Internet! I started writing Tom’s books right before the pandemic happened. At first I relied on the rather extensive research I had done for another novel set in Elizabethan London. By the time I was ready to delve into more specific espionage-related research, the world had all but shut down. Fortunately, the Internet offers a wealth of resources. As I started to dig, I was overjoyed to discover how much digitized material is available. Sites like British History Online, JSTOR, and the Map of Early Modern London are a few of the more obvious mines –but there is much more! It was an unexpected joy to delve into almost anything, from the Calendar of State Papers to parish records. And if something is missing, there is always the possibility of reaching out and asking. Historians, archivists, museum curators, librarians, experts in several fields… I’ve got in touch with knowledgeable and generous people all over the UK and the US, happy to share their knowledge. As for print books, the Biblioteca Baratta in Mantova has grown used to my outlandish requests. And finally, there is the more practical side of research, like pestering medical friends for gruesome detail, or enlisting the help of a provost-at-arms specializing in historical fencing.”

One of the perennial issues facing the historical novelist is the degree to which the writer maintains fidelity to the historical record whilst creating a narrative that satisfies the reader. Clara spoke about how

she approaches the matter. “Thomas Walsingham was an ideal choice as a character in many ways: enough is known about him to place him firmly in Sir Francis’s network of spies and at the courts of both Elizabeth and James, on the one hand; on the other, what is known leaves ample leeway for me to insert fictional murders, events, and people. I like to think that, when telling a story, the historical novelist’s job is to imagine what we don’t know on the ground, and within the bounds of what we do. My primary rule is that I try very hard to avoid contradicting documented facts, and I’ll put a good deal of effort in the research. When there are holes in the facts, I’ll make up what my story needs through guesswork or extrapolation, trying to stay true to what is known, and to the mindset of the time; when there are contradicting versions, I’ll choose the one that better serves my story. After all, these holes and contradictions are the bread and butter of historical fiction, the spaces where the novelist can work. That said, I’m not always entirely rigorous. Take Book Four [A Deadly Complot, 2024], for example, and the Babington Plot: we do know, from another agent’s report, that young Thomas was present at a certain house just before a certain important arrest –and this is all we have about his involvement in the operation. Out of this I’ve spun a whole novel.”

Clara told us about the Tudor period historical fiction that has inspired her and her favourite historical fiction writers. “The early days of my Marlowe obsession, Anthony Burgess pushed me down the fictional rabbit-hole. Then there was Rodney Bolt’s History Play, a rather hard-to-describe novel, half-academic parody, halfuchronia. I loved Patricia Finney’s Becket and Ames series, and her Carey Mysteries under the name of P. F. Chisholm. Other favourites are Bryher’s melancholy The Player’s Boy; that strange, scintillating book that is George Garrett’s Entered from the Sun, Robin Chapman’s Christoferus, and Ros Barber’s The Marlowe Papers. When it comes to other periods, Dumas Père and Walter Scott presided over my childhood, making me an avid reader of historical fiction very early. In their wake, here is a handful of favourites in no particular order: Ronald Blythe, Barry Unsworth, Rudyard Kipling’s historical short stories, Rosemary Sutcliff, Ellis Peters, James Atcheson, Robin Blake.”

Happily, Clara has signed on with Sapere Books for three more instalments, bringing Tom to 1590, with ideas for more stories bubbling away in her fertile mind.

Douglas Kemp was an HNS reviews editor from 2008 to 2024.

LATE BLOOMER

BY TRACY BARRETT

Karen Cushman's historical fiction for children and young adults

Known for her portrayals of spunky girls (and one boy) from the past who forge their own paths in defiance of convention, Karen Cushman came late to writing historical fiction. As a child, she churned out poems, plays, and stories, but as is the case with many enthusiastic young readers, it didn’t occur to her that she could actually be a writer herself one day. Her interest in the past, too, was evident early in her life. She majored in Greek and English at Stanford University and holds two master’s degrees, in Museum Studies and Human Behavior. She taught Museum Studies at John F. Kennedy University for eleven years. But despite her interest in history and writing, Cushman’s first novel wasn’t published until she was 52 years old.

It started after she began researching the material culture of children

from the past. She woke one morning hearing a child calling her. She listened, and that child’s story turned into her first novel, Catherine, Called Birdy. She doesn’t consider the years she spent in other pursuits wasted time, however. She wasn’t ready to write until she had experienced more of life, she says, and by the time that child called to her, Cushman had developed the necessary confidence. She explains, “I got old enough to realize there were things I wanted to say, despite fear or reluctance.”

And she started off with a bang—Catherine, Called Birdy, published in 1994, was awarded a Newbery Honor and also a Golden Kite Award from the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators, among other accolades. Soon after the novel’s publication, Cushman resigned from teaching to become a full-time writer.

Her second novel, The Midwife’s Apprentice, won the 1996 Newbery Medal, and both Catherine, Called Birdy and Cushman’s third book, The Ballad of Lucy Whipple, have been made into films. She has since published a regular stream of well-received and popular historical fiction for younger readers, leading to a total (for now, anyway!) of eleven books, most recently When Sally O’Malley Discovered the Sea (Knopf Books for Young Readers, 2025), reviewed in this issue.

This latest novel is an odyssey of sorts. An orphan with no friends, who has been “chucked out” of her job at a mineral springs hotel, Sally is intrigued by what she has overheard people say about the sea. She decides to walk west from central Oregon to see it for herself. Encounters with wild animals, sometimes wild people, and the elements threaten to cut her trip—if not her life—short. Then Sally meets up with a woman called Major, an itinerant peddler who seems just fine traveling alone, with only a dog and a mule for company. When Major is tasked with transporting another orphan—this one a bratty little boy—to relatives further west, she asks Sally to join them and help out. Seizing this opportunity for companionship and shelter on her quest, Sally accepts the invitation. Along the way, not only does she learn to trust others, but she discovers that she herself is worthy of trust, and even love. Despite the grim situations the characters frequently find themselves in, the text is full of humor and warmth.

Cushman credits much of her success to her late husband, Philip. When she started writing Catherine, Called Birdy, she recalls, he “encouraged and supported me, but he wouldn’t listen to [Catherine’s] story. He would read it, he said, if I wrote it down. So I did. Once I had words on paper, I was committed.” She and Philip continued to encourage other later-in-life aspiring authors. In 2013 they established the Karen and Philip Cushman Late Bloomer Award in conjunction with the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators, which annually awards a

prize to “authors over the age of fifty who have not been traditionally published in the children’s literature field.”

She doesn’t regret her own late debut, saying, “I couldn’t have written the books I wrote any sooner. I didn’t know enough about the world or myself. What I write comes from who I am, what I’ve seen, and what I’ve experienced.”

Regarding her creative process, Cushman says that she starts with a short first draft—typically under 80 pages—and then gets to work adding text: “I have to add details like a sculptor adds clay to a wire armature to bring a statue to life. It’s my favorite part of the writing process.” Working this way allows her to create whole new scenes as well as to enrich existing text, around material she uncovers. Some dramatic episodes in When Sally O’Malley Discovered the Sea, for example, were a result of Cushman’s coming across newspaper accounts of a disastrous 1861 flood in Portland.

From her vantage point of more than thirty years of writing for publication, Cushman reflects on the state of the publishing industry today. She says, “I think publishing has changed both for the better and not. Positive changes in society as a whole means more voices, more experiences, more viewpoints are welcome. The internet and social media introduced new ways to reach readers. New technologies have brought us ebooks, audio books, and print on demand.

“Not positive changes include the fact that so very many books are published each year. It’s easy for books and writers to get lost in the crowd. Over-busy editors and agents are hard to reach and need extra time to respond. Plus there is a major influence of marketing departments on what is published, how it’s publicized, what it looks like. I’ve had disagreements about book jackets and covers, only to be told ‘marketing likes it’ and they win.”

Readers are fortunate that despite these challenges, Karen Cushman continues to write beautifully crafted accounts of young people standing up for themselves and finding their inner courage. Sally O’Malley is a worthy descendant of Birdy, Brat, Lucy Whipple, and Cushman’s other brave and compassionate characters.

Tracy Barrett is an HNR US Reviews Editor and author of numerous books for young readers, both historical fiction and other genres.

References:

1. https://cynthialeitichsmith.com/2021/05/author-interview-karencushman-on-what-sparks-her-inspiration/

2. https://www.hbook.com/story/karen-cushman-talks-with-

roger-2025

3. https://voiceofvashon.org/episode/realtalk-karencushman-on-writing/

4. https://www.scbwi.org/awards-and-grants/for-writers/karencushman-late-bloomer-award

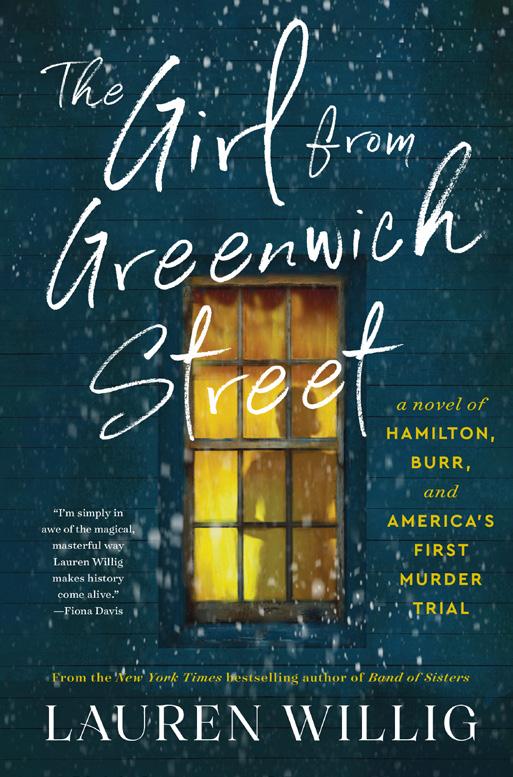

GIRL FROM GREENWICH ST

BY ILYSA MAGNUS

Admired creator of the Pink Carnation series, collaborative historicals and stand-alones – and NYC litigator turned career novelist – Willig has focused her talent on the 1800 Manhattan Well Murder trial. I had the great pleasure of reading The Girl from Greenwich Street (William Morrow, 2025) and interviewing Willig about her process in recreating this historic event.

When did you first learn about the Manhattan Well Murder? What drew you to the story? Seven years ago, I was scrolling through social media and stopped short at a post about the Manhattan Well Murder of 1800, an unsolved true crime in which a young woman was found dead—and Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton teamed up to defend the young carpenter accused of her murder.

Like most people, I was drawn to this case for the wrong reasons: Hamilton and Burr. How wonderful and strange, I thought, the two of them joining forces to save a man from the gallows just four years before the fatal duel and mere weeks before the hotly contested New York elections of 1800. It turned out that wasn’t wonderful at all; they were frequently co-counsel.

But you know what is wonderful about this case? The trial transcript. The Levi Weeks case is America’s first fully recorded murder trial. The clerk of the court took down the testimony verbatim through two electrifying days of trial that played out the way trials often do on television, but seldom in real life. Lies, secrets, adultery, unexpected twists…. Once I read that transcript, I was hooked. It was Law and Order: 1800!

How long did it take from inception to publication? What was the most difficult thing about writing the book? The thing about being a career author is that no matter how exciting an idea is, it has to wait in the queue behind the books you’re already contracted to write. I stumbled on the Manhattan Well Murder when I was researching Band of Sisters. It wasn’t until January 2022, when I’d finished that book, its sequel, and two Team W books [co-authored with Karen White and Beatriz Williams], that I was finally able to start digging into the research on the Manhattan Well Murder—and discovered that nothing was what it seemed.

That was the hardest thing about writing this book: untangling fact from myth. So much of what “everyone knows” about this case turned out to be wrong. Instead of the six months of research I had envisioned, I wound up on a two-year archival deep dive ranging from letters in the New-York Historical Society to the collections of the New York Law Institute to census records in Cornwall, New York to biographies of obscure Quaker preachers. I felt like I was back in my history grad school days!

How did you make the transition from “romantic” historicals to one featuring Hamilton and Burr? Believe it or not, it’s been a decade since the last Pink Carnation book was published! I’ve written eight standalone historicals and five Team W books since those Pink days, so it’s been a long, gradual transition. Having grown up on M. M. Kaye and Karleen Koen, I’d always wanted to write sweeping historical sagas set in all sorts of places, and those stand alones let me wander from 1920s Kenya to Colonial Barbados to Gilded Age New York.

But it was really Band of Sisters that made this book possible. Until then, my books had involved fictional characters living out fictional stories in the context of real events. Band of Sisters was based on thousands of letters written by Smith College alumnae who went to the front in World War I. That archival deep dive, building up a book based on the real experiences of real people, paved the way for researching and writing The Girl from Greenwich Street

Is there one character who you believe is focal to how GFGS evolves? The most important—and the most elusive— character in this case is Elma Sands, the woman in the well. She gets trampled over by authors in their eagerness to get to Hamilton and Burr, used as a pretext to get them into the courtroom, flattened into an innocent woman seduced or a melancholy nymphomaniac laudanum addict, Madonna or whore, with no attempt to get to the real woman underneath. I don’t believe you can understand this case without trying to understand Elma Sands. It is her actions and relationships, and, ultimately, her character, which are crucial to making sense of what happened the night she left the boarding house at 208 Greenwich Street and never came back.