· Appendix ·

· Introduction ·

· Body and perception ·

· The body in architecture·

· Perception and design tools ·

Consider a person with two different areas of activity; the one being architecture and the other dance. On a daily basis, it would consider both fields and its interpretation of reality would happen through both these perspectives at the same time. What is more, it would probably see the one art filtered through the other. The person will wonder: How are these two disciplines correlated? How can their works interact? And eventually, how could one discipline benefit from the other?

The arts are always the same, they always have the same principles. Architecture is a matter of space, music is a matter of sound, sculpture is a matter of volume, painting is a matter of colour.

Nikos Eggonopoulos1What follows is an attempt on finding a relation, reciprocal and of essence, among the disciplines of dance and architecture. The fundamental elements that can be found in both fields are the ones of movement, body and space. An interesting point where these disciplines overlap is the practice of site-specific choreography. Site-specific dance consists of the choice of a (usually non-theatrical) space, its recognition and interpretation of the choreographer or dancer and, finally, the transcription of this interpretation into movement, dance, for the creation of the artwork. This practice can be considered a successful example of essential correlation of dance and architecture, as it follows the scheme described above. It distinguishes the characteristics of space, that is, its expressive architectural elements, it reads into them and re-expresses them or reacts to them through movement (that is, the expressive element of dance). However, this correlation process, despite being essential, is unidirectional. Here, dance uses the analysis of an architecture expression as its composition tool, but its final result leaves the space unaffected. Similar examples can be found on the opposite direction, where an architect could be using the interpretation of a dance work as its composition tool for the creation of a space. Another limitation of the site-specific dance practice is the context in which it is inscribed. The fact that it is always about a work that is consciously created, presented and received by the audience as a work of art does not allow it to be considered as an all-encompassing way of relating the two disciplines. What is more, it rids the experience and movement rendition of it of the elements of honesty and spontaneity.

This raises some reasonable questions.

What would happen if we were to remove this practice from its artistic context? For a start, the aim of creating a choreographic work would cease to exist. This time, the moving bodies would not belong to dancers, trained in complex movement, but to people of all characteristics and abilities. It seems likely that we would have people interacting with different special arrangements, unprejudiced, and responding to them spontaneously. This venture would be characterized by the context of everyday life.

Finally, the question concerning the architect also arises. How could the architect (if possible) affect, foreshadow or even encourage bodily movement through the design of space?

Methodology

In order to reach the point of determining principles for bodily – oriented space design, it is essential to study the ways in which someone perceives space with his/her body. Here, the ways of embodied perception that regard the shape/ position and the movement of the human body will be examined, aiming to the proposal of specific methods for its “mobilisation”2, through space design.

The method of initially detecting tools of (embodied) space perception and, afterwards, utilising them for space design, is vaguely referring to Kevin Lynch’s method on the analysis of urban space perception as presented in his book “The Image of the City”. After his analysis of the well known five elements that comprise one’s image of a city, Lynch goes on to encourage the architects and city planners to use these elements as composition tools for their design. 3

Correspondingly, we will first examine theoretical views on embodied space perception and, generally, the correlation of body, movement and space. We will address the subject from the focal point of architectural theory and practice, but also through some theories of philosophy, psychology and neuroscience. Then, tools of embodied space perception will be distinguished and, finally, will be put into use for the design of a space, on the premise that it will contribute to its visitors’ mobility.

2 The term “mobilization” is used here in brackets, as, in the course of this project, it became apparent that a person’s body can be kinetically activated without necessarily moving. This kind of activation is also pursued throughout this project. Altogether, the activation of the body, in terms of movement, will be referred to as mobility.

3 Kevin Lynch, ‘The Method as the Basis for Design’, in The Image of the City (Cambridge, London: The M.I.T. Press, 1960).

· Body and perception ·

Since the age of the Enlightenment and with the flourishing of science, the perception of the body and the mind as two independent entities of the human condition was established. Knowledge and truth attained an objective character and were attributed to the mind, while the body became a mere receiver of exterior data, through its sense organs. This scheme which presents the clear separation of the interior and exterior world, presented here in a simplistic way, has also contributed to the value superiority of the mind to the body, which seems to prevail in this day and age (at least) in the western world. Different philosophical views on the matter of the perception of the world were developed based on this idea, which focused sometimes on the exterior, material world (empiricism) and sometimes on the inner world (intellectualism), but always maintaining the separation of the body and mind. This distinction was questioned in the beginning of the 20th century by the French phenomenologist, Maurice Merleau-Ponty.

Merlaeu-Ponty saw perception holistically. He argued that the human body cannot be seen as only as material (existing as a thing), nor as purely immaterial (existing as a conscience), but is both at once. Consequently, in the process of perception, we cannot separate the sensory imprints of things from the meaning we attribute to them. Perception relies on both of them, which are conceived simultaneously. But the necessary condition for perception is the physical presence of a person. The understanding of the world and matters is shaped through the person’s body.

What I know of the world, even scientifically, I know from my own perspective, or an experience of the world, without which the symbols of science would mean nothing.

So, the concept of lived body is introduced; a major concept in his philosophy. Supporting that the existence of the object of perception presupposes the existence of an embodied subject that perceives it, he renders perception as a bodily phenomenon. And, since the body and its capacities are finite, so is perception. Thus, he reaches the conclusion that the world is what we perceive (contrary to the previous beliefs which argued that the world exists regardless of the person), so, the subject and the world cannot be separated; the one does not exist without the other.

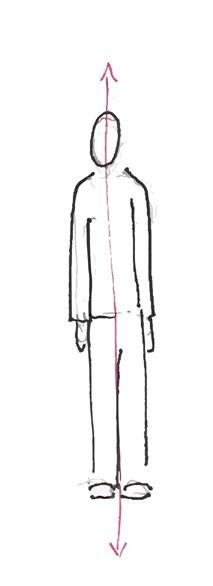

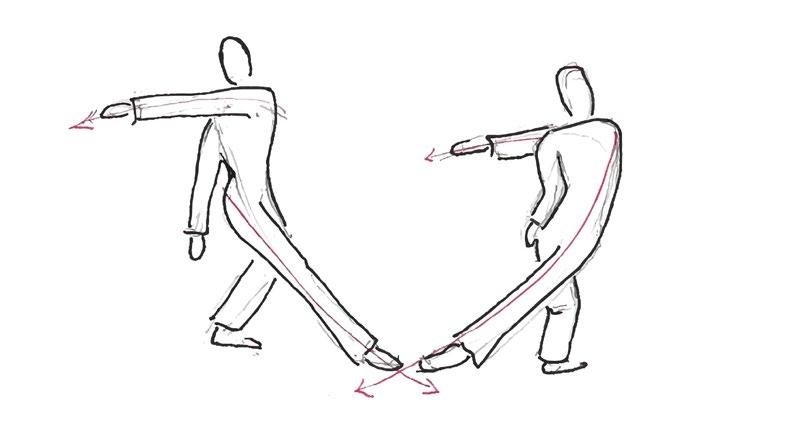

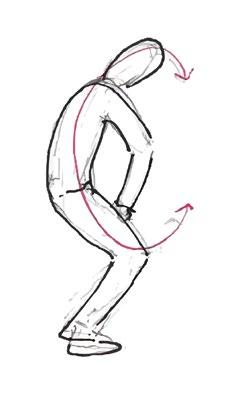

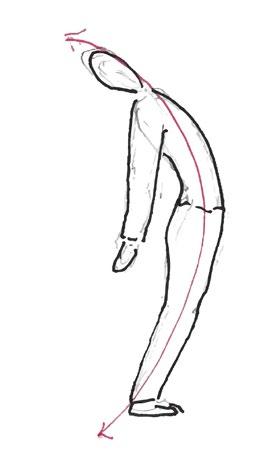

As for the way the body perceives space, Merlaeu-Ponty introduces the concept of body schema. Body schema is a pre-conscientious system of body movements and their spatial equivalence which renders kinesthetic consciousness possible1. This way, objective space forms a single system with personal body space, since the second expands to the first through movement, or event through the intention of it. That would mean that mobility is our way of approaching the world, as it allows for the perception of our surroundings. What is more, the dimensions in which we “measure” the world around us, are always defined around and in relation to our body.

Depth is the link between object and subject, width is the link among objects, while height is their vertical relation. 2

These are only few of Merlau-Ponty’s ideas regarding the perceptual process and the body’s part in it. They (or their variations) have set the foundations to further research in embodied perception, beyond the boundaries of philosophy, in fields such as psychology, epistemology, architecture and more.

One similar line of thought regarding the embodied space perception is the psychoanalytic theory of Body-Image.

The body-image is defined as the complete feeling, or three-dimensional Gestalt (sense of form) that an individual carries at any moment in time of his spatial intentions, values, and his knowledge of a personal, experienced body. It should be considered a psychical rather than a physical model. 3

This model’s most basic characteristic is that the person unconsciously puts its body inside a three-dimensional boundary. This boundary distinguishes the “interior” personal space from the “exterior” extrapersonal, which still depend on each other for their existence. The boundary’s shape and size are affected both by psychological factors, as well as from surrounding elements. The person’s acquaintance with its interior and exterior space takes place simultaneously, since they form an inseparable entity, during its infancy, even before the ability of expression is developed. In fact, these two types of spaces are primarily perceived as one, and go on to be distinguished as separate later on. With this acquaintance, which happens through the bodily senses, takes place the primary perception of three-dimensional space. The person, aware of its body-image and, consequently, of its personal space, expands its space perception to the rest of the world accordingly. The understanding of the world throughout its life will always be traced back to these primary bodily experiences that are collected mostly during the new-born and infancy age.

Indicatively, an outcome of this process is the notional transference of body “landmarks” to spatial or other elements (e.g. we refer to the heart of a building, a city, a matter, attributing to that bodily perceived traits of our own heart, as is centrality). Apart from the landmarks, we also define directions in space according to the body. Front/back and right/ left are based on the orientation of our body and face (as we unconsciously and constantly are aware of them through our body-image), while up/down are based on the direction of gravity (as we are aware of it through our bodily sense of balance). In fact, these psychophysical coordinates are not neutral, like the ones of the cartesian system, but bear meanings, closely related to the primary bodily experiences.

The sum of these experiences, held and regularly recalled through our memory, allows us to read into our surroundings through vision (e.g. we know that ice is slippery just by looking, without needing to step on it). Thus, images rely on previous body experience for their interpretation.

Piaget delved further into the study of the development of perception and its importance for the intellectual and kinetic development of children. He also argued that children’s first experience with perception is through their body, and specifically, through touch. By touching, a child is allowed to get to know, not only the shape of objects, but also their essential character. It realizes their texture, the volatility of their form, their size, their colour etc. According to Piaget, for a child to be able to remember and understand the perceived forms, it needs to analyze them to their fundamental components, which can later be recalled and recomposed. He named these fundamental forms schemas. This is the first stage in the development of human intelligence. In the next stage, these audiovisual responses are transformed to personal symbols, a personal expression of reality. They later surpass the personal experience and tend towards the higher, collective level, as they evolve into social symbols of general social approval. Thus, we reach Collins and Quillian’s theory, which argues that objects are represented in the visual and kinesthetic memory as models (a collection of their characteristic renditions or the concept’s best example), along with a collection of their possible variations. 4

However, the sensorimotor perception system does not only concern the person’s interior and exterior space perception, but extends in the field of knowledge development and use. Cognitive science attempts to study the nature, components and sources of knowledge, based on experience. It argues that knowledge is not limited to the input and output of the nervous system, but consists an interaction with the world. By stating knowledge’s embodied character, cognitive science does not separate sensorimotor from ideational perception, but claims that the latter borrows the organising formations of the first. One of the cognitive mechanisms with an embodied character is the one of imageschema, according to Lakoff and Nunez. Image-schemas are primary, universal, bodily grounded schemes, of preconceptual and pre-linguistic character. (e.g. The scheme of confinement; it is a spatial scheme which is implemented also in abstract disciplines, such as Maths.)

So, we see that the body with its senses, but mainly with its own conscience, is the starting point for the perception of the world. The individual’s bodily experiences, especially the ones acquired during infancy, gradually shape its perceptual abilities, regarding both the space and abstract concepts. Therefore, the embodied senses become of great substance. But which exactly are they and how can they be related to the well-known five basic senses?

The notion of the five basic senses (sight – hearing – smell – taste – touch) became widely established during the Enlightenment era, even though it has existed since the age of antiquity, established by Aristotle. In fact, they have been classified according to their ascribed value, with sight being the highest of all (which is why light symbolizes truth and knowledge), hearing being next to it, while the remaining three are considered inferior, suited more likely to animals rather than humans, since they entail the subject’s direct contact to the perceived object. Even in our age that this notion has been disputed through various scopes (of art, philosophy, neuroscience etc.), public demonstrations of these senses are frowned upon.

The attempts of the 19th century’s scientists to study the human body’s sensory organs and their function resulted in great confusion, as, according to the traditional notion of senses, various organs with different functions would need to be attributed to one single sense, especially in the case of touch. J.J. Gibson’s work was crucial to the clarification and further research in this field. Examining the subject from the scope of environmental psychology, Gibson categorized senses in five perceptual systems, according to the type of information each one perceives. These are the visual system, the auditory, the taste-smell, the basic-orienting and the haptic systems. The last two are more relevant to embodied perception as it is presented here, considering they have to do with space, body and its movement. The basic-orienting system regards our perception of the directions up/down, according to gravity, and therefore, our awareness of the horizontal ground plane. It is directly related to our sense of balance. The haptic system regards our sense of touch throughout our entire bodyscape, interior and exterior, in relation to alien objects or parts of the body itself. 5 The concept of interaction is inherent in this system, in contrast to the visual and auditory systems. Gibson’s work did not replace Aristotle’s senses, nor the ones established later. What it did was to untangle the subject of touch and provide a holistic view on the categorisation of sensory function.

In the study of sensory perception today, neuroscience deals with the somatosensory system as well. This is the equivalent of Gibson’s two last perceptual systems and consists mainly of somato-aesthesia (sensations originating from the surface of the body) and proprioception (sensations originating from the interior of the body). Some types of information that are perceived through somato-aesthesia are texture, pressure and temperature, while some that are perceived through proprioception are the muscles’ range of movement, the position and movement of the body in relation to the ground etc. One characteristic example of a sense in the category of proprioception is kinesthesia, which is the perception of movement of the body parts, through its muscles, tendons and joints.6 If we were to broaden our scope to all of vertebrates, we would find that there are researches that name a considerably larger variety of senses, like, for example, rheoception (the sensation of water flow according to which aquatic beasts calculate their movement) or chronoception (flow of daily time, biological clock), which do not necessarily fit the categories named so far. 7 It is, however, made apparent that science has progressed greatly since the age when five senses were considered to be enough. Regardless of the classification and the number of senses, what is crucial is that we regard them as a single perceptual system, since the one sense’s function cannot be isolated from another’s.

Nevertheless, the perception of the environment through the body is not limited to the collection of haptic input. The philosopher R. Vischer introduced the term empathy in order to describe the emotional connection to an object, through the projection of the person’s feelings on it. Initially it was used in the context of aesthetic theory and it later came to be used in psychology. Through empathy we can understand the structure and characteristics of an object while, most of the times, we unconsciously tend to imitate it.8

Weight, pressure, and resistance are part of our habitual body experience, and our unconscious mimetic instinct impels us to identify ourselves with apparent weight, pressure, and resistance in the forms we see.

Geoffrey Scott· The body in architecture ·

The Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa has dealt extensively with the subject of embodied perception. In the world of contemporary architecture, he is the main adherent of the critical role of the human body in the design and experience of space, an opinion expressed distinctly through his theoretical work, which is still inseparable from his realised architecture projects. He places the body and its senses in the epicentre of architecture, a discipline which he regards sometimes as the environment in which and in dependence to, subjectivity is defined (according to Merleau-Ponty’s theory), and other times as an art whose works transfer the architect’s metaphysical, existential thought to the visitor.

All works of art cause bodily interaction, a type of dialogue between the work of art and its receiver. Upon our meeting with a work of art we project our thoughts and emotions and, eventually, we recognise ourselves in it. That is how we measure, hear, know, possess the world, with our entire bodily existence. This is the notion of empathy, in its aesthetic theory context, as we came upon it in the previous section. Beyond the aesthetic quality of architecture, we can also perceive its scale through empathy. By projecting the body, its members or potential movement on the parts of an object or building, we “measure” its dimensions. In fact, when the body recognises itself in elements of space, this results in a sensation of pleasure and security. Similarly, through empathy we can comprehend the structure of a building, by its unconscious imitation and the sensory impact on our muscles and bones this creates.

Unknowingly, we perform the task of the column or the vault with our body. 1

The same process takes place in the architect’s body during the design. The site’s parameters, the project’s requirements, but also the principles of the designer’s ideas work as stimuli for his body. He can feel in his muscles, bones and tendons the potential space. After its construction, when the visitor experiences the built space, this sense is mirrored directly from the architect’s body to the visitor’s.

This experience regards the totality of the visitor’s embodied perception, meaning it engages all of his senses at once. According to Pallasmaa, a work of architecture is perceived, not as a collection of images and sensory information, but in its entire material and mental presence, through the cooperation of the senses. Most of the times, when a piece of information is perceived through a sense it is accompanied by a corresponding one that is received or retracted from the memory or phantasy from another sense, simultaneously. Art works this way, too. Each form of art causes sensory activation through its characteristic medium (painting – image, music – sound, architecture – space), which then incites abstract thought.

Architecture, through the manipulation of space, materials, light and shadow, can address the rest of the senses, too; not merely sight. For example, many times, a sound gives away the shape of a space. You can feel the size of a big, marble hall by listening to the reverberation of the sound of your footsteps as you enter it. Other times, a certain scent is linked with a specific place, or rather its memory. Then again, sometimes the image of materials tingles your sense of taste, as in the case of shiny, colourful surfaces of tiles which invite you to taste them. Finally, touch, by reading into the texture and shape of objects, gets to know the process of their creation, the events that shaped them, their degeneration etc.

Buildings are not meant to be seen; buildings are encountered. They are created to be approached, touched, moved through, used. They attain their meaning and characteristics from these actions and the way the body knows and remembers. The ancestral qualities of comfort, protection and intimacy that we often seek in our built environment are deeply grounded in our embodied memory through the experience of countless generations. Thus, we see that the building does not exist independently; it frames, structures, correlates and encourages behaviours and movements. 2

There is an inherent suggestion of action in images of architecture, the moment of active encounter, or a ‘promise of function’ and purpose. […] Consequently, basic architectural experiences have a verb form rather than being nouns.

If we only consider children’s play, like walking next to a metal railing and running a stick or your hand along it’s rhythmic parts, or balancing on the edge of the sidewalk, we understand that anything can work as a mobility stimulus. However, some buildings are more efficient mobility incentives than others. According to R. Yudell, the buildings in which the human body can be recognized (its size, structure or potential actions) are the ones that function the best as stimuli for movement. In other cases, buildings direct movement within them, by clearly pointing out their movement infrastructure (such as stairs, corridors) and by designing their impression; they function as stages for movement. Finally, there are also buildings that create a dialogue among themselves and the visitor, implying his behaviour or movement

2 August Schmarshow introduced the concept of space in architectural thought in the end of the 19th century, based on the idea of movement as means for the perception of architecture. By proclaiming architecture as the art of space he opposed the art theorists of his time, who advocated its visual character. Schmarshow proposed a space organization that referred to human physiology, with its vertical stance realising the height dimension and its extension and symmetry realising the width. The third dimension, the one of depth demands movement in order to be perceived. That is why the only art that allows us to experience space is architecture, since it includes movement. Some of his oeuvre’s outcomes were the establishment of space as the object of architectural creation and the gradual introduction of movement as a compositional element for architects. The latter was exalted in modern architecture, particularly in the work of Le Corbusier. In his buildings, he was particularly concerned with issues such as the organisation of movement in plan, the classification and appropriate design of pathways that define movement, dealing with parameters such as visibility, accessibility and theatricality. This diligent arrangement of movement axes in a building is responsible for the experience of visiting a built space, which the architect named promenade architecturale.

inside them. A dark niche allows for isolation, a sequence of arcs for movement, while a wooden surface on the proper height allows for sitting. The body recognises the potentials for movement provided by such an environment.It is true that the human body has in fact greater movement potentials than the ones that a person performs daily. In societies in which man was still in harmony with his body, movement played an important part in personal and social life; the quality and range of movement possessed great value.

In our advanced and specialized age of information and technology […] the innate reflex of our bodies to respond to rhythms and emotions has become suppressed and consequently, the movement of our bodies are subordinated and relegated to an instrument of control and work. Whereas the celebration of movement for primitive man was an essential part of his life, we now separate expressive and creative movement from everyday life through trivializing the grace of human movement and coordination in daily routines. 3

Today, the majority of our daily motion is limited to the horizontal plane (two-dimensional movement) and serves our transportation. One-dimensional movement, such as sinking into a pool, or three-dimensional, such as a lay-up in basketball, are rendered useless in everyday life and are limited to space and time conditions meant specifically for movement as an end in itself (e.g. gym, dance, sports). At the same time, due to the technological progress, we encounter the following paradox: while people travel further (by car, train etc.) and higher (on top floors of office buildings) to get to work, the actual body movement they perform is drastically less than the one of commuting during the past decades.4 A factor that greatly contributes to this state of decline and supersedure of wide daily motion is our built environment, the spaces we construct and inhabit and the possibilities for action they entail.

The possibilities for action that an environment provides to its inhabitants is the subject of the E. Rietveld and J. Kiverstein’s publication, ‘A Rich Landscape of Affordances’. It discusses the term affordances, which was defined by J. J. Gibson as the possibilities for action provided to an animal by the environment – by the substances, surfaces, objects and other living creatures that surround it. 5 They argue that it is a more complex concept, as the affordances provided to a particular animal species by an environment depend also on this species’ way of life. This is especially true of humans, in whose case by way of living one refers to the human nature, but also the social and cultural practices of each society and the personal abilities and preferences of each person. Thus, we can claim that the mobility affordances of a built environment are equally dependent on the environment itself and on the social practices and personal abilities of its visitors.

3 Rai-pi Huang, ‘BODY IN SPACE : The Sensual Experience of Architecture and Dance’, 1991.

4 Bloomer and Moore.

5 Erik Rietveld and Julian Kiverstein, ‘A Rich Landscape of Affordances’, Ecological Psychology, 26.4 (2014), 325–52 <https://doi.org/10 .1080/10407413.2014.958035>.

On the same basis, the ability of some elements of the environment to incite, and not merely afford, movement is also dependent on all three parameters. Particularly in the case of the personal parameter, it is a fact that, as a person develops a specific ability, it changes his perspective of the environment and its affordances.6 Someone who has conquered a wide range of body movement through an activity (like play, dance, sports, etc) is more likely to detect opportunities and incentives for movement in his environment, compared to someone who has not.

Similarly, an architect who has conquered a high level of body motion ability and has detected stimuli for movement in the environment, is prone to experience them in his potential space and, as a consequence, to design this stimulating space. Nonetheless, it is essential to point out that the architect can only affect the parameter of the environment, while the two others (social and cultural practices, personal abilities) remain imponderable.

· Perception and design tools ·

From the above research, two ways of embodied perception were considered the most suited for use as architectural compositional tools. These were empathy and kinesthesia.

Empathy:

(psychology) The emotional identification with the psychological state of another person and the understanding of his behaviour and motives. 1

(aesthetic theory) The projection of a human – subject’s emotions on the aesthetic object, leading to a kind of union among the two.

In our age, the term is mostly known within the context of psychology. However, as architects, we are more concerned with its initial meaning, as it was coined by R. Vischer in 1873, in the theory of aesthetics. It expressed a contradiction to the main line of though of that era, which considered aesthetics to be a purely visual field. He placed the viewer in the centre of the aesthetic experience, not the image of the work of art. It is worth noting that, even though it has been argued from time to time, empathy does not coincide with imitation, as through the first we can also grasp actions that we cannot perform. It has also been claimed, during the history of the term, that we can also project emotions in space or time (recognising various potential points of view).

Physical forms possess a character only because we ourselves possess a body.

H. WölfflinIn the field of contemporary architecture, the main adherent of empathy is J. Pallasmaa. His holistic approach to the experience of (designed) space, as well as the major role he attributes to the human body and its senses in design, are direct references to the notion of empathy. In the book ‘Mind in Architecture’ that he coedited with S. Robinson, they delve further into the subject of empathy in architecture, and go on to analyse its relation to the function of mirror neurons. They are parts of the brain which are activated, not only when our own body performs a movement, but also when we watch another body act (or even when we watch inanimate objects). This neuroscience discovery came to confirm the theory of empathy and its relation to the experience of space. According to Pallasmaa, it leads the way to the use of neuroscience to highlight unrecognized aspects of design that are currently considered impractical due to their subjectivity or are considered “weak” because they are based on intuition. 2

Kinesthesia:

The perception of movement of body parts through its muscles, tendons and joints. 3

Kinesthesia belongs to the general category of somato-aesthesia, in the area of proprioception. The latter regards a person’s awareness of his body’s position, shape and movement, without the interference of vision. The person senses quantitative gradations of the forces and tensions developed in the body, through receptors in his musculoskeletal system. While proprioception is generally concerned with the awareness of someone’s self and personal space (meaning his body-schema), kinesthesia in particular is concerned with the person’s recognition of the surrounding environment, as it entails interaction with it.

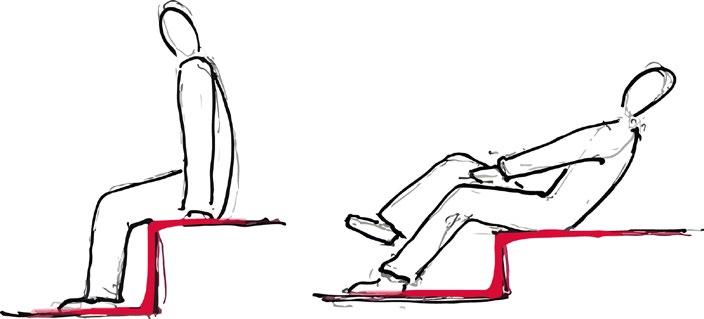

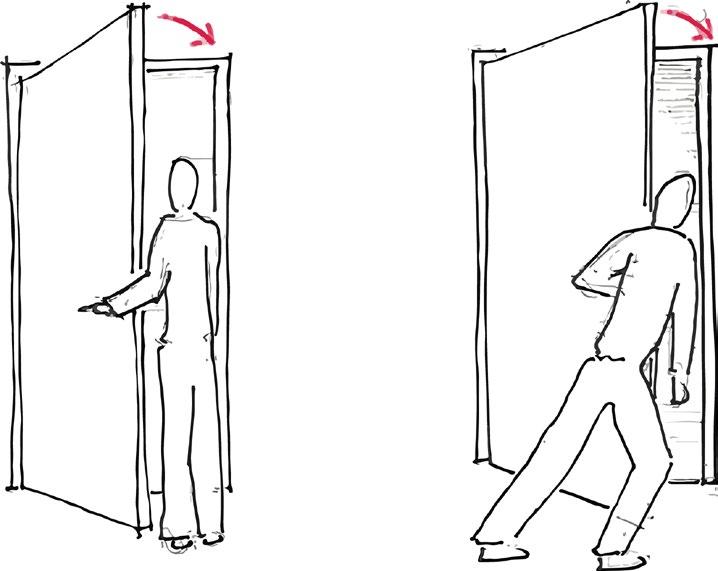

The body perceives its environment kinesthetically by interacting with it. It measures the height of a seat when it sits, it meets the weight of a door when it closes it.

These two concepts can be utilised by architects in the design of a space aiming to the mobilisation of its visitor. It is, however, of substance that an architect is aware that, while space can provide its visitor with opportunities and incentives for mobility, there are still more parameters that determine the users’ final behaviour.

This is exactly what was pursued in this thesis’ design part; the design of a space that will contribute to the mobilisation of its visitors. With this in mind, installations and spatial conditions referring to the human body through empathy and kinesthesia were designed. The intention was to encourage the visitor to move beyond his usual daily motion range, without forcing him to do so. The activity of dance was also integrated in the proposal, in order to function as an incentive for the visitors’ empathy (identification of person with person-dancer), as well as a way of obtaining the skill of extended body movement, which would enhance these peoples’ predisposition to mobility. On the other hand, factors like the gradation of privacy, appropriability, delineation of areas of activity, all integral parts of architectural creation, were determined to ensure the most favorable functional and psychological conditions for the desired mobilisation.

· Bibliography ·

Bloomer, Kent, and Charles Moore, Body, Memory, and Architecture (Westford, Massachusetts: Yale University Press, 1977)

Huang, Rai-pi, ‘BODY IN SPACE : The Sensual Experience of Architecture and Dance’, 1991

Lynch, Kevin, ‘The Method as the Basis for Design’, in The Image of the City (Cambridge, London: The M.I.T. Press, 1960)

Pallasmaa, Juhani, The Eyes of the Skin (Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley and Sons, 2012)

Rietveld, Erik, and Julian Kiverstein, ‘A Rich Landscape of Affordances’, Ecological Psychology, 26 4 (2014), 325–52 <https://doi org/10 1080/10407413 2014 958035>

Rodriguez, Ludmila, ‘The Body of the Audience’ (KABK, 2013) <https://doi org/10 4324/9781315054643-4>

Βισκαδουράκης, Ελευθέριος, ‘Μια Προσέγγιση Στη Φαινομενολογία Του Maurice Merleau-Ponty’ (Ε.Κ.Π.Α. - Ε.Μ.Π., 2017)

Γενιάς, Κώστας Ορφέας, ‘Η Διαλεκτική Των Σωμάτων Κατά Την Εμπειρία Του Χώρου’ (Σχολή Αρχιτεκτόνων Μηχανικών, ΕΜΠ, 2017)

‘Διάλεξη Στο Ελληνικό Αθηναϊκό Ινστιτούτο, 1963’, in Στην Κοιλάδα Με Τους Ροδώνες (Αθήνα: Εκδόσεις Ίκαρος, 2007)

Λαρεντζάκη, Κατερίνα, ‘Η Έννοια Της Ενσυναίσθησης & η Σύνδεσή Της Με Την Έννοια Του Εαυτού’ <https://www. academia.edu/40473457/Η έννοια της ενσυναίσθηση> [accessed 27 March 2020]

Παπαθεοδωρόπουλος, Κώστας, Αισθητικότητα, 2013

Χολή, Ερατώ, ‘Η Κίνηση Των Σωμάτων Και η Τοπολογία Του Αρχιτεκτονικού Χώρου’ (Σχολή Αρχιτεκτόνων Μηχανικών, ΕΜΠ, 2014)