The author of this thesis practices both architecture and dance.

Apart from the presentation of the design part of the thesis, this booklet includes also readings and thoughts, parallel to the creation process, which consisted the starting point, the design perspective, but also the essence of this project.

Dancing bodies

Dance Center and Park in the former Athens’ Municipal Slaughterhouse Student: Sofia Chionidou

Supervisor: I. Zachariadis

Consultant: C. Caradimas

Diploma thesis

School of Architecture NTUA

October 2019

Abstract

What is the relation between architecture and dance and how can the one discipline benefit from the other? For instance, how could a space be designed in order to host the choreographed or (even harder) the spontaneous movement of its visitors? The present diploma thesis was carried out in the quest for answers to such questions

The necessity of the creation of a Dance Center, that is, a public infrastructure to host dance creation in Greece, constitutes the practical basis of this project. This space concerns the daily reality of the backstage work of dancers, not the exceptional case of the show, providing thus the opportunity for the creation of an alternative setting for dance space design. This setting seeks to unify the daily reality of the dancer with the urban condition, the everyday life of non-dancers, attempting the fruitful merge of the two At the same time, a space, preferably public, which encourages the activation of the human body and the expansion of its everyday movement is also required, as varied everyday movement is a vital element that seems to be missing from life these days. Therefore, the creation of an environment where architecture would be designed with regard to the human body is attempted, providing the conditions and stimuli for the spontaneous movement of its visitor

Dance Centre

Dance is a very popular art1 in Greece today and is practiced extensively by amateurs as well as professionals. Twenty professional dance schools are in operation, while the number of amateur schools is very impressive. At the same time, there is a high technical and artistic level which can be detected both in the high percentage of Greek dancers in dance companies and productions globally, and in the substantial amount of internationally distinguished Greek artists (e.g. Papaioannou, Kapetanea, Laskarides).

In full contrast, the conditions for the profession make it very hard to practice. Indicatively, some of the essential issues dancers in Greece face today are those of labor rights (non-recognition of diploma, partial insurance, retirement issues, etc.), as well as the complete absence of state support for artistic endeavors. One of the main problems is also the lack of spatial infrastructures for the creation of a dance piece (and not for its presentation, as Greece, and Athens especially, is full of theatrical spaces).

ΣΕΧΩΧΟ, the Dance Worker’s Union, has been demanding the creation of a Dance Centre for years.

Every art in order to evolve has to be practiced, every artist has to practice his art to evolve. Before we even face the demons of creation, we dance artists face the enormous problem of finding the proper space, the unbearable cost of renting it, and the time pressure it entails. Both the preparation and the presentation of a dance project require space with a proper floor, sufficient dimensions, heating, the ability to use props. The above is not a luxury for an art that demands maximum body performance. And while no one can imagine that a musician, for example, could be abusing his musical instrument, it seems quite natural to expect dancers to abuse their own instruments, their bodies. Creating a choreography takes time for genuine artistic research, and this valuable time is spent on organizing production, promoting it, advertising it. A Dance Centre that would provide two stages, rehearsal space, support for residencies, production organization, the possibility of collaborating with other art groups, artists, lighting technicians, stage designers, would create the condition for the development and evolution of the dance and choreographic force of this country, which insists despite the conditions.

From ΣΕΧΩΧΟ’s website

1 Referring to the art and the profession of dance, I mainly, but not exclusively, mean ballet and contemporary dance, as they are the work subject of both the professional dance schools as well as ΣΕΧΩΧΟ, and they, among all dance genres, regard contemporary artistic creation the most.

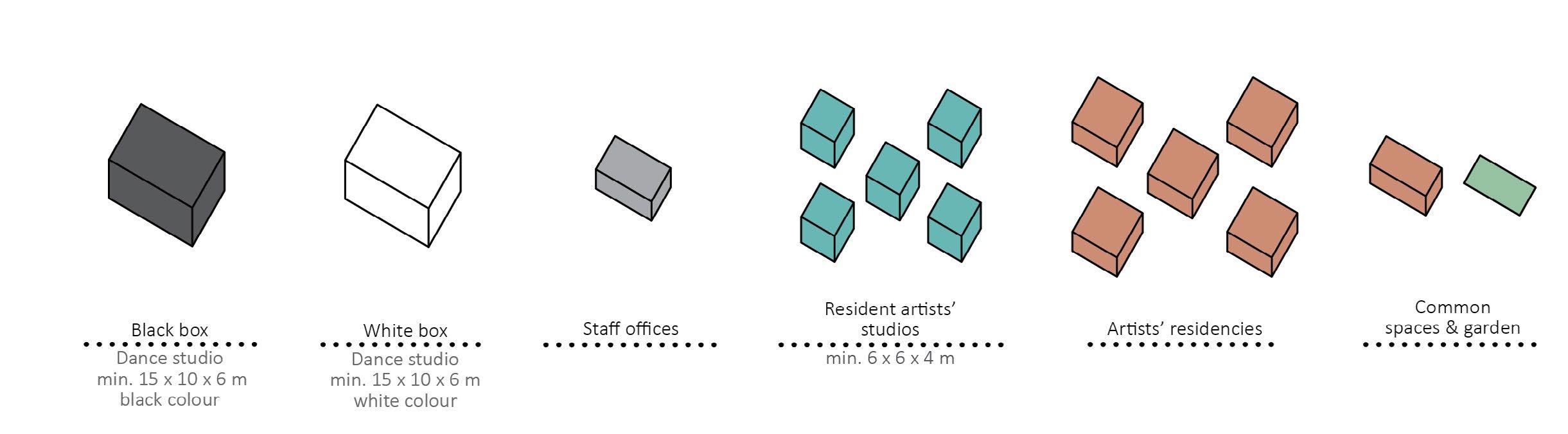

Building programme and operation requirements of the Dance Centre spaces by request of the dancers’ association to the Ministry of Culture

Artistic residency

Artists’ residencies provide artists and other creative professionals with time, space and resources to work, individually or collectively, on areas of their practice that require heightened reflection or focus.

This practice can be traced back to the patrons of Renaissance. Its modern form appeared for the first time in the end of the 19th – beginning of 20th century, when groups of artists started moving to the countryside for work and research. At the same time, art loving sponsors put the foundation for more hierarchical practices by providing residences to the artists.

By the 60’s, different types of artistic residencies started to be distinguished: artists’ withdrawal to nature for creation / social interaction with the greater public as means to creation / self-organised residency by artists, alternative to the conventional practices sponsored by galleries or patrons. After the 80’s, global communication and transport was made much easier. Today, more and more initiatives and networks are created all the time, enriching and widening the practice.

Arts Residencies are:

Organised and sufficient time, space and resources

Enablers of the creative process

Reflective of their lexical meaning as ‘an act of dwelling in a place’

Based on clear mutual responsibility, experimentation, exchange and dialogue

Engaged with context by connecting the local to the global

Crucial to the arts ecosystem

Bridging mechanisms between different arts disciplines and non-arts sectors

Tools for inter-cultural understanding and capacity building

Essential professional and personal development opportunities

Catalysts for global mobility

Encounters with the unknown

Profile-raising with immediate and ongoing artistic, social and economic impact

Important contributors to cultural policy and cultural diplomacy2

2 ‘Definition of Arts Residencies – Res Artis’ <https://resartis.org/global-network-arts-residency-centres/definition-arts-residencies/> [accessed 3 April 2020].

Artistic residencies suitable for dance in Greece

1 Kinitiras (nomadic structure)

2 Ionion Center for the Arts and Culture (Metaxata village, Kefalonia)

5 studios / fully equipped theatre / 11-16 artists / 2 weeks – 1 year

3 Living in the Garden (Paros) 4 studios / 4 artists / 1-3 months

4 Akropoditi Dance Centre (Hermoupolis, Syros)

2 studios / theatre (black box) / 2 artists / 1 week – 1 month

5 Sfakiotes Residency Programme (Lefkada) 1 studio / 4 artists / 2 weeks – 2 months

6 Mudhouse Residency (Agios Ioannis, Crete)

3 studios / 11 – 16 artists / 2 weeks

7 Between the Seas: Mediterranean Performing Arts (Monemvasia)

1 studio / 3 artists / 1 week

8 X-SALTIBAGOS (Patras) 1 studio / 5 artists / 2 weeks

Thus, the design of a Dance Centre is attempted; a unique, nationwide, structure for hosting the local dance creation. It would be an infrastructure for the dancers’ (both locals and guests) daily work, a field of work which remains behind closed doors normally, leaving out anyone not directly involved. This condition maintains the relationship of dancers and non-dancers in the dancer-audience scheme, keeping the proper distance among them. In the attempt to subvert this condition, the daily life of the Dance Centre shall be combined with the one of a public open space, for the creation of an organic, inseparable whole, a Dance Park. The park will be designed to blend the activities of these two different types of users (dancers and random park visitors), aiming to the demystification of the dancer but also the bodily activation of the visitor.

The dancer’s demystification is a concept that can be found in the contemporary dance world since the 80’s. It belongs to a line of thought that considers the spontaneous, everyday movement to be an important compositional element and subject of dance, thus introducing everyday life to the field of dance, but also dance in the field of daily life.

Simultaneously, the non-dancer’s contact with the choreographic process, and also the practice, lessons and rehearsals procedure, brings him closer to a reality based on a wide range of body movement, which is an element that tends to be neglected in this time and age. Nowadays, most people only barely move during their daily routine and, when that happens it is under specific circumstances, where movement is seen as an end in itself (gym, sports, dance classes etc). This disembodiment that can be detected more and more lately, is not a mere result of the technological development, but it also regards humanistic values. Such is the appraisal of the mind against the body, its senses and abilities.1 Therefore, the inducement of the visitor’s movement is set as an end for the design of this project. That is to be achieved through stimuli such as the visual and personal contact with dance professionals, as well as spatial installations that promote – suggest – receive body movement.

1 This phenomenon is not at all irrelevant to the architectural creation of our age, where the prevailing elements seem to be either the impressive imagery or the absolute functionality of the building, against its haptic and spatial qualities.

For the placement of the Dance Park, the following factors were taken under consideration.

Supralocal range

The Dance Centre infrastructure would be the only one of its kind in Greece. Its users consist of both the local dancers and the ones that would be hosted in the residencies, and it therefore has corresponding demands regarding its location. Free space, correlation with the ground and nature

As we are dealing with the design of a public park, enough free space is required so that the building infrastructure of the Dance Centre can be created, while leaving room for a substantial park to be developed; one that will be able to coexist equally with the Dance Centre. What is more, the correlation with the ground and nature concerns the body directly, therefore creating conducive conditions for its mobilization

Residential area

To the point that the blending of the everyday lives of dancers (through the Dance Centre) and non-dancers (through the public park) is pursued, the latter needs to be ensured. Placing the complex in a residential area would provide the overall area’s everyday life activity that is desired.

Building reuse

Putting aside the ethical aspect of reusing existent buildings in urban environments, the main reason why reuse is presented here as a desired design condition is the haptic value of aged buildings, as well as their most common construction materials’ (wood, stone etc).

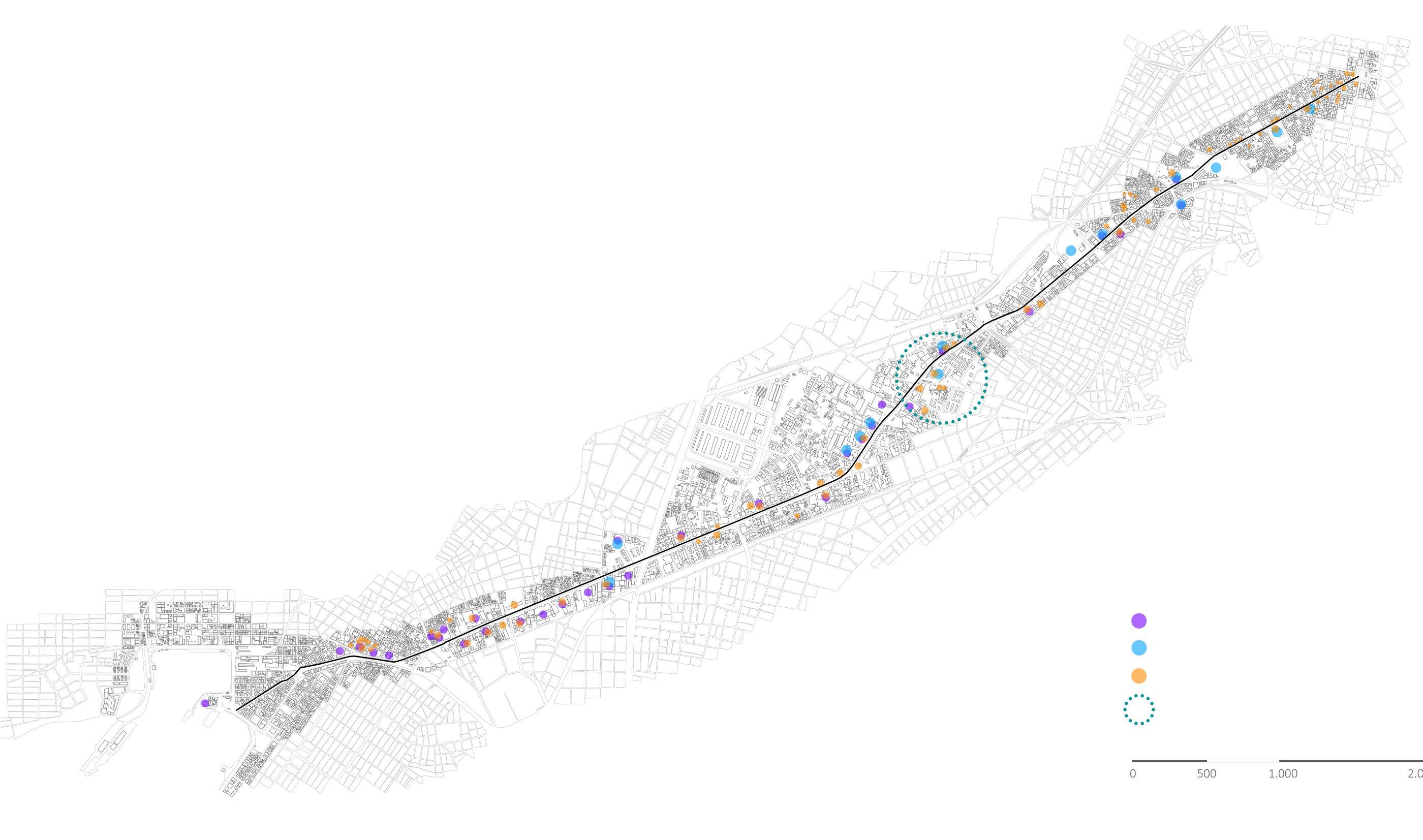

Piraeus street

The axis of Piraeus street provides a quite appropriate opportunity for the placement of the Dance Centre and Park, according to the parameters set previously. It is one of Athens’ major roads, thus attaining supralocal character. Due to its industrial past, it is also filled with listed buildings. During the past decades, Piraeus street’s transformation from an industrial to a cultural axis has been extensively studied, planned and is gradually being carried out. However, this character is up until today quite fragmentary, with poles of remaining industrial activity (e.g. Pavlidis chocolate factory), of commercial activity (e.g. Athens Heart), as well as of cultural activity (e.g. ASFA, Benaki Museum) scattered along it.

Despite this favorable condition, most listed buildings on Piraeus st. are not suitable for this project. The majority of former industrial buildings are characterized by introversion, as they are completely closed and unrelated to the city around them, while, at the same time, they exceed the human scale. What is more, the character of the fronts of the street resembles anything but a residential area. It consists mainly of impersonal former or current industrial buildings, large-scale commercial, sport, cultural facilities, none of which is related to the daily routine of a neighborhood.

In the area of Tavros, this changes. Green, open spaces begin to show, as the area of the social housing complexes expands on both sides of Piraeus st.. In accordance with the above, the former Municipal Slaughterhouse of Athens mark a clearance for breathing in the course of Piraeus st..

LEGEND

Industry

Culture

Listed buildings

Former Athens’ Municipal Slaughterhouse

The area

The former Athens’ Municipal Slaughterhouse is located in the social housing area of Tavros, built by OEK (Organization of Workers’ Housing) in the period from the’ 60s to the mid-’90s. These are multi-storey buildings that stand independently within the building blocks, creating abundant green intermediate spaces, in which networks of pedestrian alleys and squares are developed for the entrance the buildings. These spaces do not seem to be exclusively private or public. The everyday life of the inhabitants presents itself in them. This is what gives the area the human scale that is missing from the rest of the fronts of Piraeus.

This area is easily accessible, since, apart from the axis of Piraeus, it is served by many bus lines as well as the stations Tavros and Kallithea of ΗΣΑΠ. Nearby the former Slaughterhouse there are two important cultural centres, the Michael Cacoyannis Foundation and the complex of the School of Fine Arts, a bit further towards the south.

The Slaughterhouse

The Municipal Slaughterhouse was moved to this location in 1916, from Charokopou, in Illissos, where it was previously operating, and gave its name to the settlement of Tavros, which until 1972 was called «Nea Sfageia» (New Slaughterhouse). The complex was designed by the chief engineer of the Municipality of Athens, K. Zannos, and its construction was carried out from 1914 to 1917, during the tenure of Emm. Benaki, as indicated on the sign above the main gate of the complex. New buildings and additions to the existing ones were constantly being added to the complex, until the end of its operation, in the 80’s. In 1988, half of the triangular plot was turned into a park, which remains the same to this day, while in the same year some of the buildings of the Slaughterhouse, those of the original complex, were appointed of great importance. They are the ones that are still preserved today. In 1997 they became officially listed, along with 87 other buildings and 10 facades of buildings on Piraeus st., including the complex of stables with which they operated, in the adjacent building block. Today they belong to the Municipality of Athens.

The neoclassical buildings and the entrance gate to the complex, as well as one of the two main buildings of the Slaughterhouse have been restored. One of the two neoclassical buildings and the main, elongated building are managed by the Municipality of Tavros- Moschato, and used for its Cultural Center. There are daily art classes and events in these spaces, whereas other areas of the complex are often granted for the use of various other organizations. The outdoor area and the other buildings of the Slaughterhouse are in a state of abandonment and are sometimes used by the Municipality as temporary storage areas (for building materials, garbage trucks, seasonal decorations, etc.). The park’s facilities are now semi-destroyed, either due to the lack of maintenance or due to the subsidence that has appeared on several points on the ground. Its planting keeps growing uncontrollably and it does not seem to be used regularly by the locals.

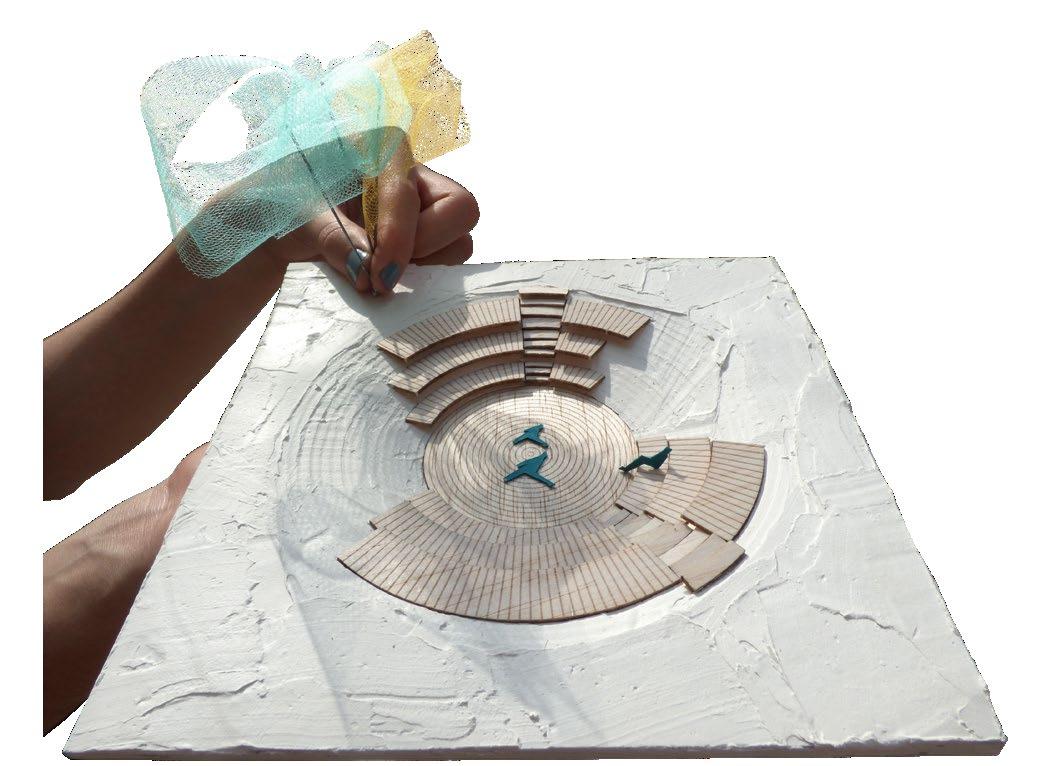

Functions Grouping and Connections

The functions that the Park will host are those of the Dance Centre (Black Box, White Box, dance studios and residences for guest artists, offices), those of the Cultural Centre, which mostly remain in their existing spaces (halls and offices), a coffee shop and various outdoor installations, which facilitate the meeting of different types of park users, while also being the background for their mobilization.

The whole plot is perceived as one single unit, a homogeneous field along which the different functions are scattered All activities taking place there are meant to be carried out simultaneously and in communication with each other However, for an organisation like this to be functional, there needs to be a hierarchy in their layout, regarding their privacy and intro/extroversion. Some are meant to assist the encounter of dancers and visitors of the park (visual or literal), while others need to be protected from the public eye and access in order to operate (e.g. residences).

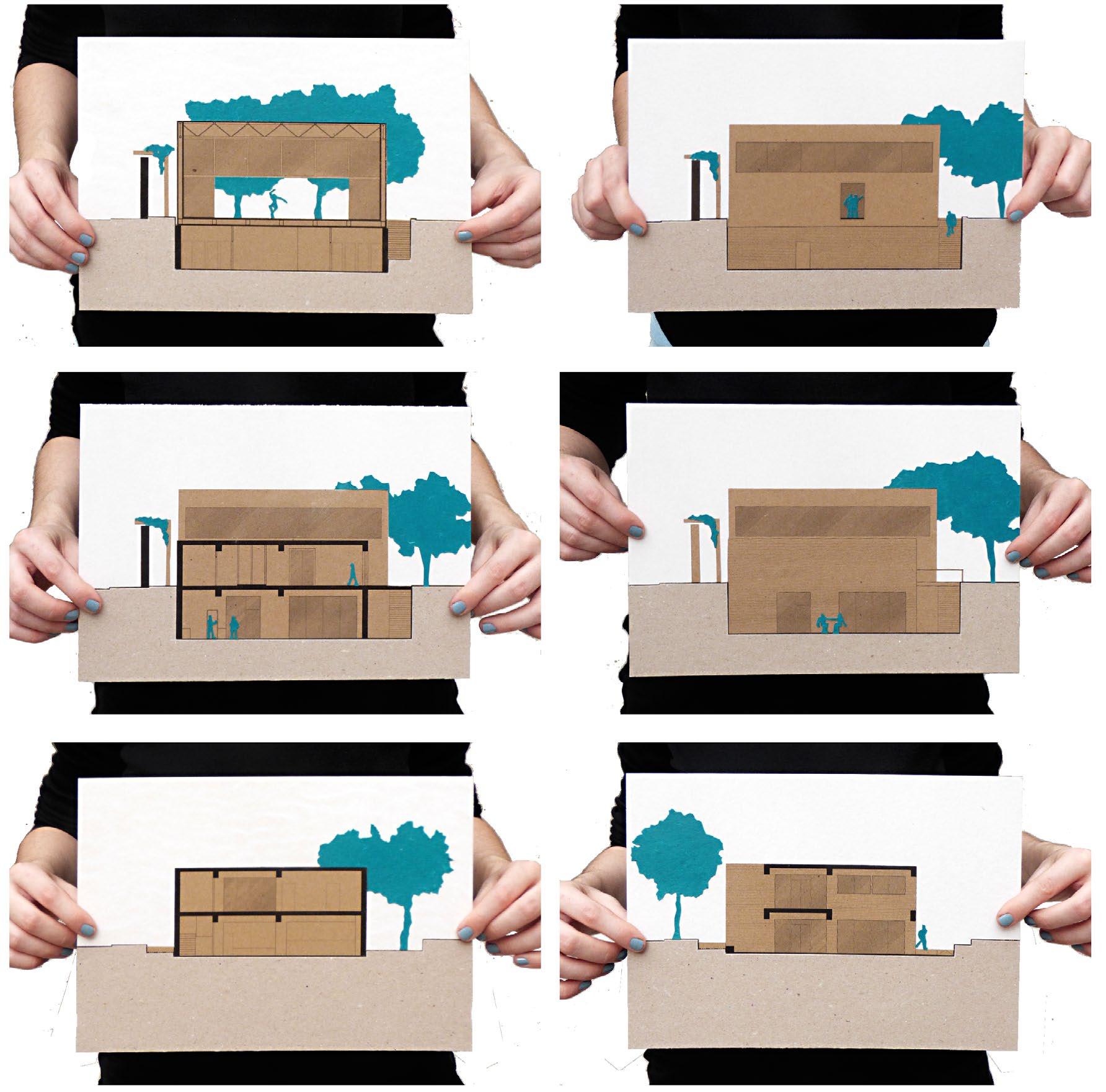

The Black Box and White Box spaces assume and, at the same time, exhibit these two opposite qualities in the form of dance infrastructure In this context, the Black Box is created as an outward directed space, meaning its interior is open to observation and can be expanded to the immediate outdoor space, allowing the public to get in touch with the activity it hosts On the other hand, the White Box is created to be an inward directed space, preventing the visual or literal access of the public to its interior This way, it provides its users with the isolation that is sometimes needed for the realisation of the creative process. These conditions are achieved with the proper handling of parameters such as the placement inside the plot, the position and size of the building’s openings, the relation to the ground, the access to the space e.t.c.

Variation of the intensity along the site

While examining the site we can note the gradual increase of intensity from the side of Tavros’ neighbourhood to the one of Piraeus’ street. The term intensity is here referring to multiple factors, such as noise, circulation, building scale, range and extroversion of activities and possibly more similar factors The layout of the different functions within the site should follow the same scheme

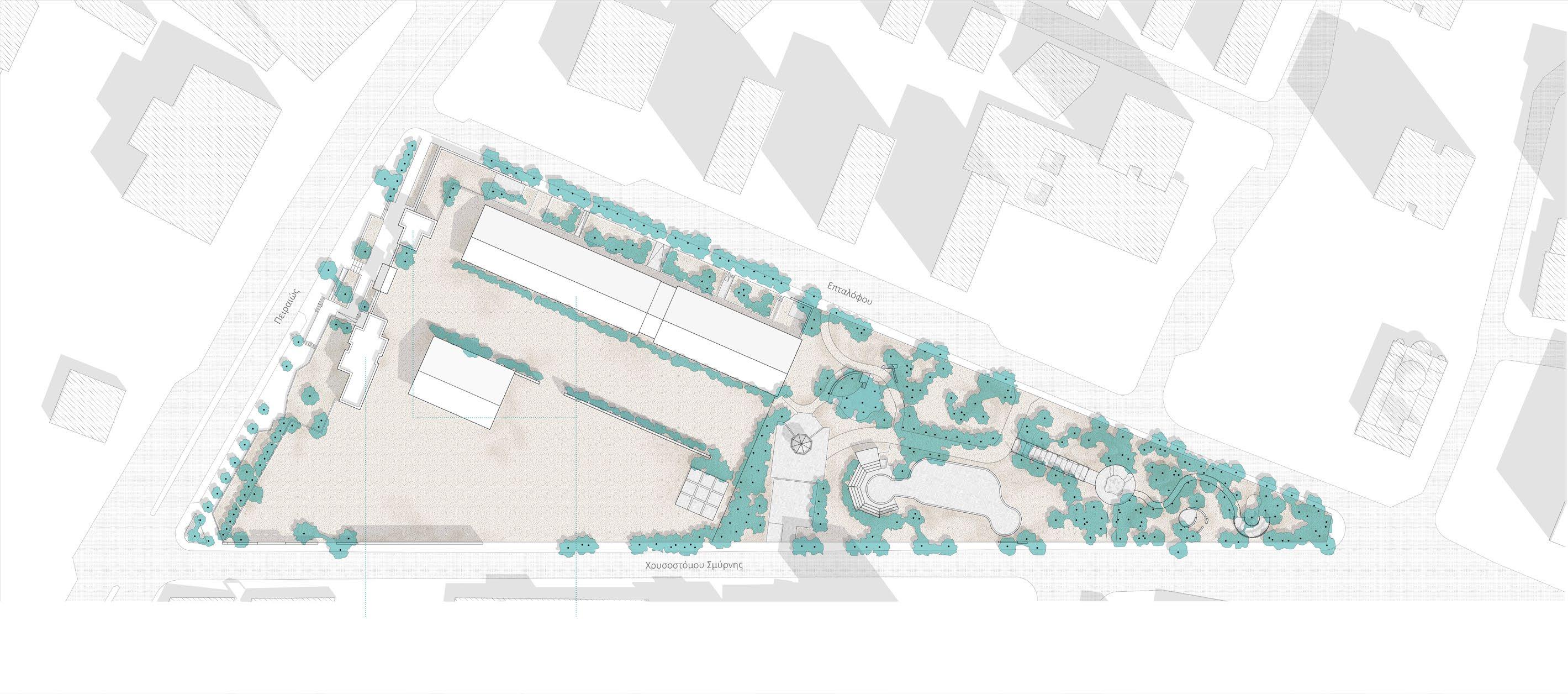

Axial systems

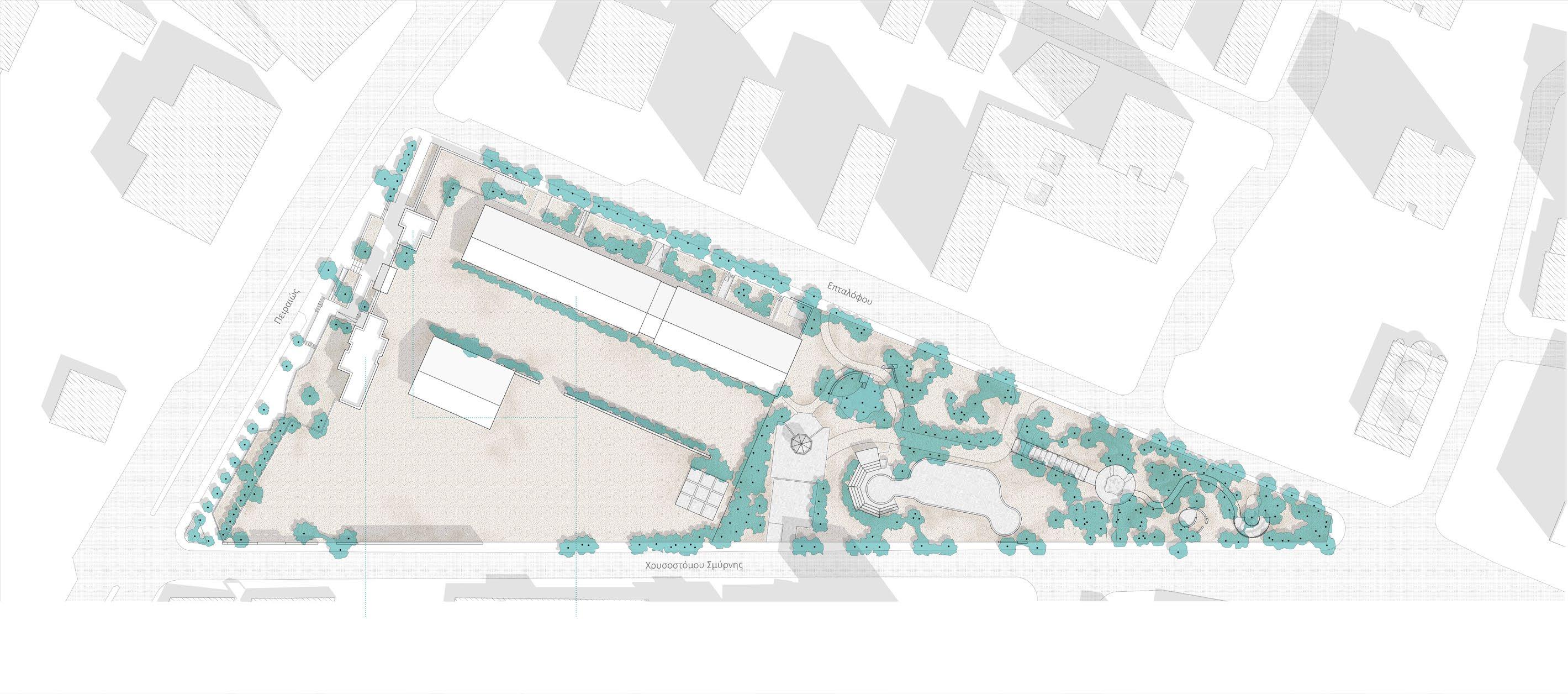

Another major parameter regarding the organization of the different functions within the site is its triangular shape. This almost right triangle creates two perpendicular axis systems˙ the one of its perpendicular sides and the one of its hypotenuse (Chrysostomou Smyrnis st ) The existing Slaughterhouse buildings are designed based on the first system

The Dance Centre’s new buildings are placed according to the second system, on a 17m wide strip, on the face of Chrysostomou Smyrnis street

Existing situation

The only spaces that are currently on operation are the facilities of the Cultural Centre. These include the oblong Slaughterhouse building and the smaller one of the neoclassical buildings. Entrance is granted exclusively from Eptalofou street, and the oblong building’s halls are closed on their side facing the interior of the plot There is no access for the public to the open space of this half of the plot, while the other half, the park, has two entrances, one on each street The plantation, which is left unattended on the part of the park, seems to be confined in it

Proposal

In the proposed plan, there are few interventions on the existing buildings, mainly on their interior. The Cultural Centre’s building maintains its function, while the neoclassical buildings’ interiors are remodeled to host its offices, as well as the ones of the Dance Centre The strip of the Dance Centre’s infrastructure is created, as well as the outdoor installations The entrance to the entire complex is through the old gate of the slaughterhouse on the side of Piraeus street, while the entire side of Eptalofou street is left open On Chrysostomou Smyrnis a point of access to the centre of the Park is created where there used to be the limit between the former park area and the rest of the slaughterhouse. The trees that need to be taken down for the implementation of the new design are replanted or replaced by new ones throughout the entire area of the plot.

Gravel is placed in several areas of the site in order to signify (in a bodily way) the entrance to the Park. For this reason, it is also placed on the ground of the semi-outdoor spaces that are created in the Cultural Centre’s building, as these spaces serve the direct connection of Eptalofou street to the interior of the complex.

Throughout the area of the site, stages (areas that allow for and imply motion in them) are created, as well as games (installations that suggest movement in – around – with them). The largest, most exposed and public stage, is the lower square which interrupts the Dance Centre’s strip. On a smaller scale, but also quite exposed are the pedestal stages (with their corresponding viewers’ benches) created along the main movement axis originating from the gate on Piraeus street. Finally, in the area of the former park, near Eptalofou street, few park clearings with small theatrical formations are created, serving as the most introvert of all the Park’s stages. They create environments more protected from the public eye, with greater freedom for movement. On the other hand, the remaining roof, bearing structure and single stone wall of the Culture Centre’s twin building, B2, can be seen as game formations. A game construction with multiple levels is formed on each side of this building’s (mostly free-standing) wall. Finally, the columns that are scattered among the trees on the Tavros’ end of the Park can also be considered as game installations.

The Dance Centre’s spaces are ordered in two levels throughout the entire length of the strip. Starting from Piraeus st. and moving towards the neighbourhood of Tavros, one encounters the functions of the Black Box, coffee shop, (followed after an intremission by the) common spaces of the residencies, their residences and studios, and finally the White Box. The entrance to each space is made independently, from the park or the sidewalk, except in the case of the residencies, in which the entrance to the spaces is gradually filtered.

The dance spaces are distinguished from the rest, through their structural system and generally their materials. They are, in fact, boxes made of a metal frame (capable of bridging the grand lengths required by the dance spaces’ standards) and cement board seathing. The rest of the spaces are made with concrete bearing structure and brick coating. Therefore, the two systems allow us to talk about structure (dance studios, metal frame) and substructure (rest of spaces, brick) in both a structural and a functional context. Brick is chosen for the substructure because of its material semblance to soil and, consequently, to the ground.

The construction system of the substructure is similar to the one of the pre-existent structures, as they both consist of natural materials (stone, brick, wood).

The Dance Centre’s strip correlates differently with the ground on each side of it throughout its length This way, it secures the degree of intro/extroversion and visibility required for each space’s function. For example, in the case of the Black Box, it is leveled with the exterior ground’s height, so that its interior space can be expanded there. In the White Box, the floor is elevated so that the interior and the exterior have no connection, while in the residencies it allows the dance studios to be visible, but also protects the living spaces of the residences.

Artistic residencies

All the spaces of the artistic residencies are gathered in one building unit, the entrance to which is made through a descend from the park. The common spaces (kitchen, living room, study and work spaces) are all gathered on one side, separated from the residences’ private spaces and dance studios with a semi-outdoor yard. The last ones are organised in pairs in a typical layout, with the residence spaces on the lower level and the dance studios on the upper one, and repeated three times. The communication of the different levels and the entrance to the individual spaces is made through semi-outdoor, common spaces, allowing for the independent access to both the residence and the studio spaces. This allows for flexibility in the distribution of the residence and studio spaces, as well as accessibility of nonresident-artists to the dance studios (audience, technicians, coworkers e.t.c.).

Residences

Dance studios

As for the layout of the spaces, the six dance studios have the possibility of being joint, in pairs, for the creation of three larger studios, in almost the same size as the Black/White Box. Also, the residences are organised in three units, each one with its own entrance and hygiene area. Each one has four bedroom – living room spaces, whose south side opens to a yard. The living room areas can also be joined in pairs, since they will most likely be assigned to artists on the same residency project. Overall, the residency building can host up to twenty four people at the same time.

Chrysostomou Smyrnis st. elevation

Section Α - Α’

Chrysostomou Smyrnis st. elevation

Section Α - Α’

The overall design of the Park aims to the merge of the dancers’ and visitors’ activities, their creative coexistence and interaction. Thus, distinguishable areas are created in its outdoor space, which allow and/or suggest the visitor’s mobilisation, while making sure that their activities, as well as the ones of the Dance Centre’s, are in constant correlation.

For that reason, the Park’s movement axes cross between the stages and pass by the games, the resident artists’ studios “watch over” and are “being watched” by the park clearings, while in the lower square, from the coffee shop’s outdoor space you can see the square-stage’s stands, with the wall and its game structure posing as their background

This coexistence that brings dancers and non-dancers closer on equal terms is the final desirable condition for the Park; a field of kinetic experimentation Ideally, people of all ages, abilities and backgrounds would be attempting to move – possibly dance – together.

The Park as seen by the visitor

The Park as seen by the visitor

and as seen by the dancer.