4 minute read

Decay

Science

Advertisement

Why food decomposes

Take a closer look at the microscopic world of food spoilage now

Micro-organisms are one of the biggest culprits for the spoilage of food; they feed on the nutrients, breaking them down into small molecules that can be absorbed across their cell walls. This destroys the structure of the food and produces by-products that smell and taste unappetising and – eventually – makes the food unfit for human consumption.

Mould produces the most visible changes to food. The branching filaments of mould are called hyphae, and their growing tips make enzymes, which break down tough molecules like cellulose and starch, converting them to mushier material. This causes the spongy feeling of decaying fruit and vegetables. The spots of mould seen on food represent huge colonies of interconnected hyphae, which advance over the surface seeking nutrients.

Moulds are actually not that dangerous to human health, mainly because their large colonies make them very easy to spot and avoid. The real danger comes from bacteria, which replicate virtually unseen. Signs of bacterial infection of food include discolouration, odour and a surface slime, but even before these changes are detectable, harmful numbers of bacteria can be present.

Not all decomposition is down to microorganisms though. Foods contain natural enzymes used during the lifetime of the plant or animal to catalyse reactions. Even after death the enzymes are still functional and contribute to the gradual breakdown of the product. This is particularly obvious in fruit like apples and bananas, which go brown when cut surfaces are exposed to oxygen; this is the result of an enzymatic reaction that produces the brown pigment melanin.

Some foods are so hostile to microbial growth that they do not go off at all. This is often down to water content and osmosis. Microbes require relatively moist environments to thrive, so dried foods, or foods very high in salt or sugar, usually remain good for much longer periods of time. Indeed, honey that’s still technically edible has been retrieved from the tombs of Ancient Egyptian pharaohs buried around 5,000 years ago.

When food turns bad…

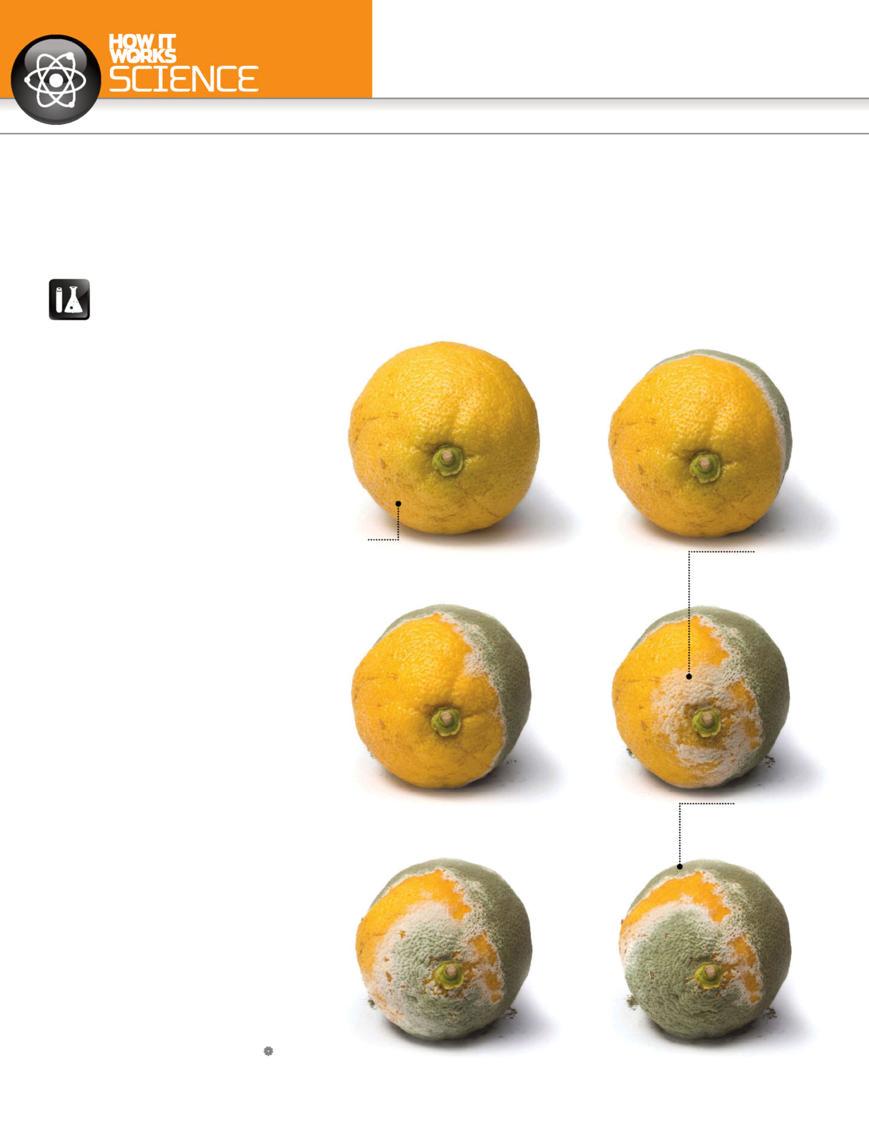

What happens to a lemon as it goes mouldy?

1. Waxed

The skin of lemons is often waxed to prevent evaporation. It provides a barrier that inhibits gas exchange and also helps to protect the fruit from mould.

3. Feeding

The tips of the mould hyphae secrete digestive enzymes, which break down the nutrients in the lemon.

5. Penicillium

Green moulds are usually of the Penicillium family – the moulds responsible for making the antibiotic penicillin.

dId YoU kNoW?

infected poultry meat glows under UV light due to the presence of fluorescent Pseudomonas bacteria

2. Colonisation

Moulds form a colony called a mycelium. The hyphae at the edges of the colony gradually advance across the food source.

4. spread

Moulds produce spores, which become airborne, enabling them to spread beyond the boundary of the colony.

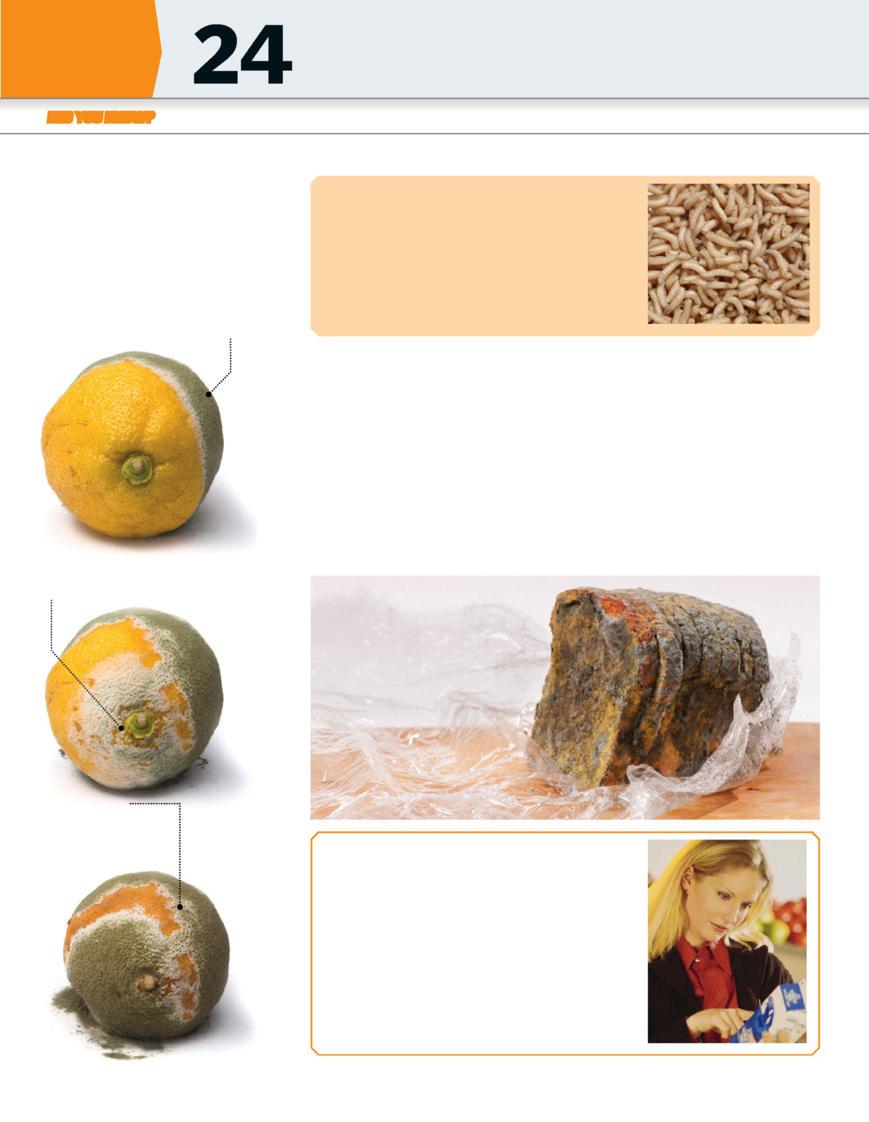

Meat and maggots

If meat is left exposed for too long it can become infested with maggots; these are most often blowfly larvae. Blowflies are extremely sensitive and can locate meat in minutes. A female will lay 150-200 eggs at a time on any exposed areas and these hatch into maggots within 24 hours. Maggots secrete digestive enzymes onto the flesh to break down complex macromolecules into smaller components. They also have mouth hooks, which they use to grind the tissue and rapidly destroy its structure. If left undisturbed, maggots will live on meat for around four days before they are ready to pupate and become adult blowflies.

How do preservatives work?

Preservatives are added to food to extend its shelf life. There are three main categories, tackling the biggest causes of food spoilage: microbes, oxygen and enzymes.

Foods can contain a range of antimicrobials, which interfere with the growth and replication of bacteria, mould and yeast. Salt has been used for centuries as a preservative; it draws water out of micro-organisms by osmosis, creating an incredibly hostile environment and preventing their survival. Oxidation is another big cause of food spoilage; the fatty acids present in butter and oils react with oxygen and then go rancid. As a result, antioxidant molecules are often added to mop up the oxygen radicals responsible for the reaction.

The final class of preservatives interferes with the function of enzymes. Enzymes are very sensitive to changes in pH, and acids like ascorbic acid (a form of vitamin C) and citric acid are often used as additives. Changes in pH alter the shape of enzymes so that they are no longer able to interact with their target molecules, essentially making them impotent.

6. shrivelling

As lemons start to decompose, water loss causes them to shrink and shrivel, producing a wrinkled, sunken texture.

best before and beyond

Food packaging often comes littered with dates which indicate the shelf life. This varies from country to country, and by food type, but there are three main categories.

The sell-by date is an instruction to the vendor, provided as guidance for stock control; this actually has very little to do with the quality, or safety, of the food. The best-before date is for the consumer; this is generally used on frozen, dried and tinned goods as an indicator of quality. It is a common misconception that food past its best-before date is unfit to eat; beyond this date the food is unlikely to be harmful, but the flavour and texture may have deteriorated. The use-by date is the most important and is included on fresh foods that go off rapidly, like meat and fish. Past the use-by date, some harmful bacteria may have reached dangerous levels and so the food shouldn’t be consumed.