5 minute read

Pyrenees formation

ENVIRONMENT

Advertisement

How the Pyrenees formed

Discover how an ancient European mountain range came back from the dead to form a high-altitude natural barrier between France and Spain

The Pyrenees stretch from the Mediterranean Sea to the Bay of Biscay in the Atlantic Ocean. This huge mountain chain has acted as a natural barrier throughout human history, separating Spain and Portugal from the rest of Europe. The Spanish and French slopes have different climates and are home to over 3,500 plant and animal species, including brown bears.

The story of the Pyrenees begins more than 500 million years ago when the ancient Hercynian mountains covered much of central Europe. This vast range was comprised of sedimentary rocks folded over granite bedrock.

Over millions of years, these mountains were worn down by rivers, wind, frost and ice. At the same time, the jigsaw of tectonic plates that make up the Earth’s crust were drifting across our planet’s surface. As a result, new oceans opened up. The region containing today’s Pyrenees became the Pyrenean basin – a low-lying area between France and Spain often submerged under the sea. Sediment gathered on the seafl oor above the old Hercynian range, eventually becoming new sedimentary rock. eventually becoming new sedimentary rock.

Around 85 million years ago – towards the Around 85 million years ago – towards the end of the age of the dinosaurs – the crustal end of the age of the dinosaurs – the crustal plate that carries Spain moved northwards. plate that carries Spain moved northwards. This closed the gap between the This closed the gap between the Mediterranean Sea and the Mediterranean Sea and the Bay of Biscay, compressed Bay of Biscay, compressed the Pyrenean basin sediments and fractured the sediments and fractured the Hercynian rocks. The younger sediments folded like younger sediments folded like modelling clay into new peaks modelling clay into new peaks and the Pyrenees emerged. and the Pyrenees emerged.

Since then, the young rocks Since then, the young rocks have worn away in places to reveal have worn away in places to reveal the ancient rocks beneath. During the last ice the ancient rocks beneath. During the last ice age – approximately 20,000 years ago – rivers age – approximately 20,000 years ago – rivers of ice fl owed down the mountain valleys. These of ice fl owed down the mountain valleys. These glaciers picked up rocks as they went, grinding glaciers picked up rocks as they went, grinding and scraping the surface below like sandpaper. and scraping the surface below like sandpaper. Over time, they carved out bowl-shaped Over time, they carved out bowl-shaped hollows called cirques and U-shaped valleys. hollows called cirques and U-shaped valleys. Today, the Pyrenees continue to be eroded by Today, the Pyrenees continue to be eroded by rivers and frost shatter at higher altitudes. rivers and frost shatter at higher altitudes.

Pyrenees in the making

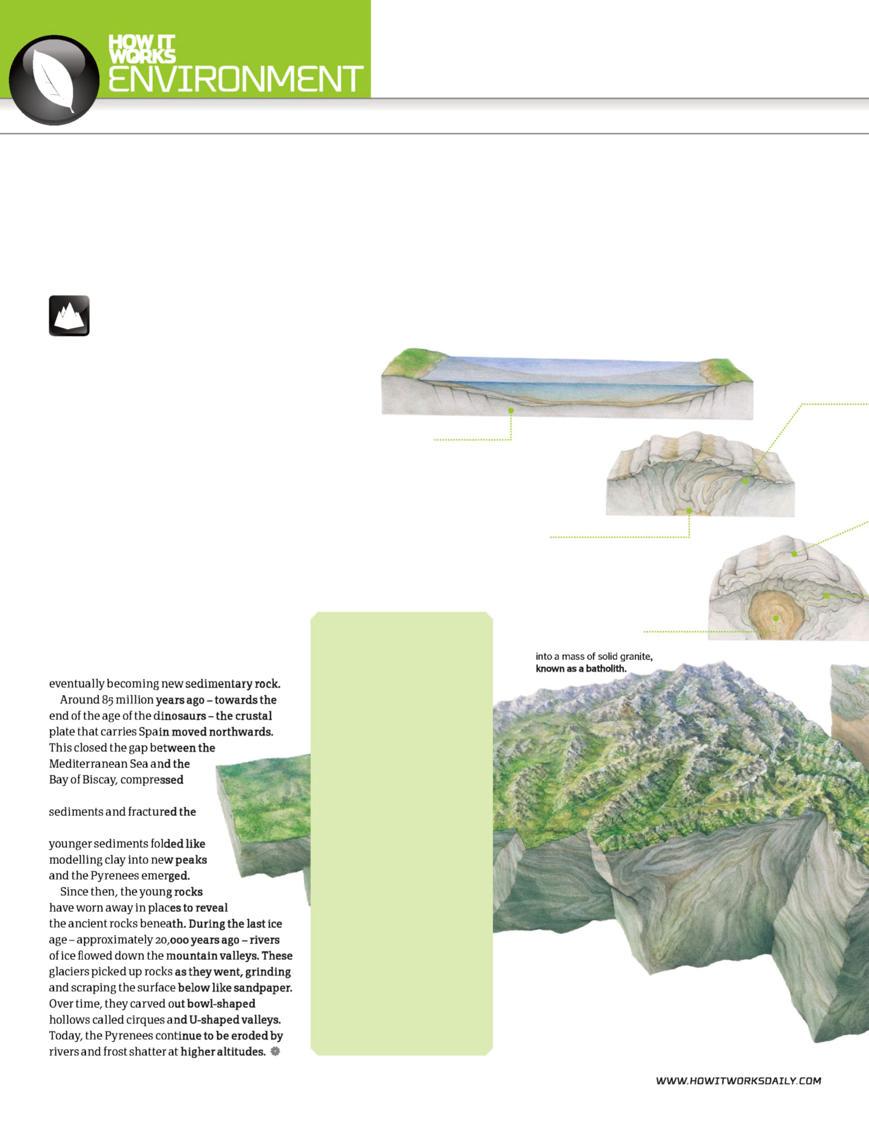

See how an ancient mountain range lurks within the foundations of today’s Pyrenees

1. Sediment buildup

Rock debris and animal skeletons fall to the seafl oor.

3. Magma rises

A bubble of molten rock rises towards the surface from deep within the Earth.

Hotspot for hot springs

In the days before antibiotics, the spa town of Barèges in the French Pyrenees was famous for the curative powers of its sulphurous hot springs. King Louis XIV sent wounded soldiers to the town, many hotels were built and – during its heyday – a fountain was commissioned from Louis Le Vau, the architect of the Palace of Versailles.

There are countless hot springs in the Pyrenees, reaching temperatures of around 37-40 degrees Celsius (99-104 degrees Fahrenheit). Their water comes from rain and snow falling on the mountains. This water migrates down through fractures in the rock over thousands of years. At depth, it’s heated by the volcanic rock that once lay beneath the Hercynian mountain range.

The faulted ancient Hercynian rock provides a convenient route for hot water to escape to the surface. It rises so quickly – ie within days or months – that it doesn’t have a chance to cool. Minerals dissolved in the warm water lend the springs their sulphurous and/or salty nature.

5. Batholith cools

The molten rock slowly cools into a mass of solid granite, known as a batholith.

DID YOU KNOW?

According to legend, the rectangular gap in the Gavarnie Cirque formed when a hero threw his sword at the cliffs

From geology to Jurassic Park

The Cirque de Gavarnie is the Pyrenees’ most famous geological feature. This gigantic amphitheatre was carved by rivers of ice tens of thousands of years ago. Its rock walls rise 1,500 metres (5,000 feet) from the valley fl oor in three terraces; that’s about the same as a stack of 350 doubledecker buses! One of the world’s major waterfalls, the Grande Cascade, plunges 425 metres (1,400 feet) over the cirque’s east side and above the cirque are Earth’s highest ice caves, hung with frozen stalactites.

Around fi ve per cent of the Pyrenees’ species exist nowhere else on Earth. One is the Pyrenean desman (pictured right). This aquatic rodent is hamster-sized and looks a mix between a rat and a platypus.

The Pyrenean ibex – a type of mountain goat with curved horns – turned real-life Jurassic Park in 2009 when it became the fi rst extinct species to be resurrected. Scientists used tissues from the last-known animal, which died in 2000, to create a baby ibex; sadly, it only survived a few minutes.

2. Sedimentary rocks develop

Over millions of years, the sediments are squashed into sedimentary rock by the weight of debris above.

6. Hercynian mountains

Together the granite and sediments form a huge mountain range called the Hercynian mountains in the location of today’s Pyrenees.

4. Metamorphosis

The intense pressure and heat (ie 650°C/1,200°F) of the molten rock transforms the sedimentary rocks, eg limestone turns into marble.

7. Sediment returns

After local tectonic activity causes the land to drop, new sedimentary rocks form on top of the old Hercynian mountain range. A close relative of moles, desmans live in mountain streams where they eat insect larvae and snails

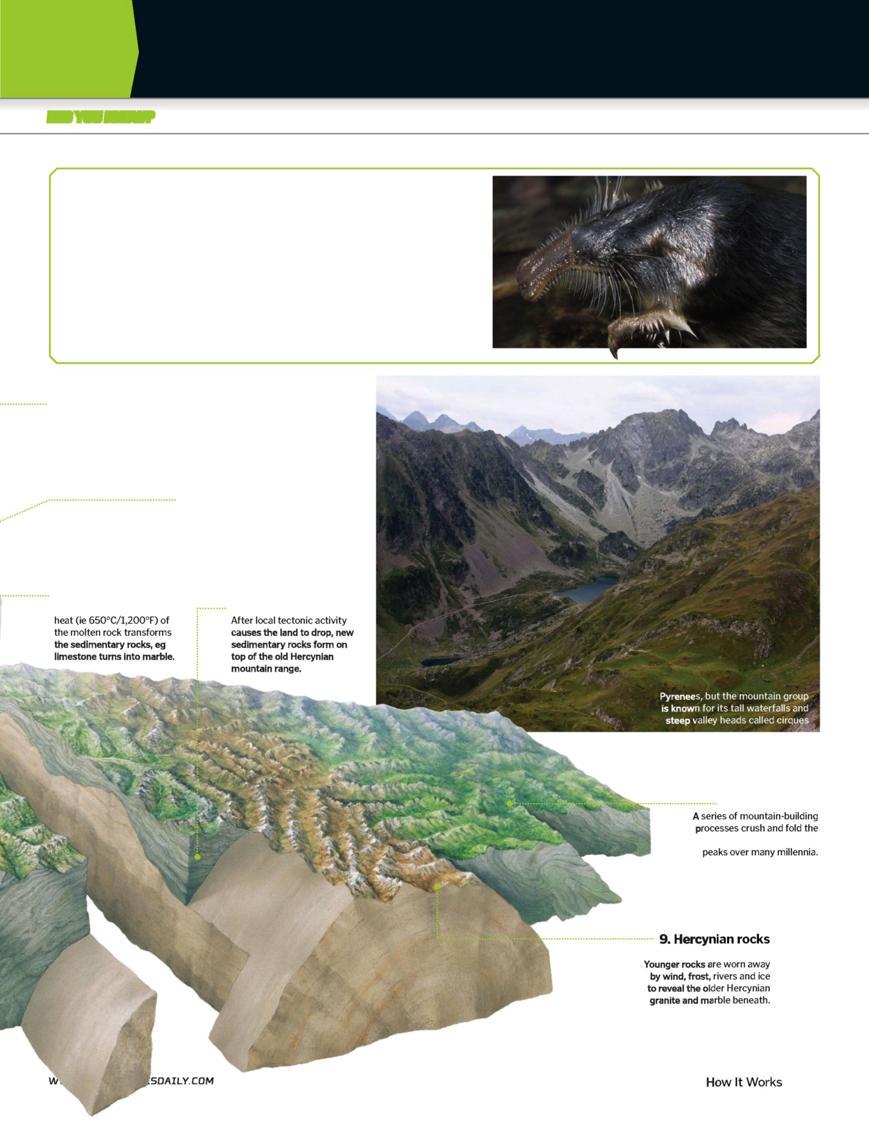

Large lakes are rare in the Pyrenees, but the mountain group is known for its tall waterfalls and is known for its tall waterfalls and steep valley heads called cirques steep valley heads called cirques

8. Pyrenees rise

A series of mountain-building processes crush and fold the processes crush and fold the rocks into a chain of new peaks over many millennia. peaks over many millennia.

9. Hercynian rocks revealed

Younger rocks are worn away by wind, frost, rivers and ice by wind, frost, rivers and ice to reveal the older Hercynian to reveal the older Hercynian granite and marble beneath. granite and marble beneath.