HERITAGE EXPLORE NEW MEXICO CHACO CANYON DISCOVER THE MYSTERY SHOP THE MARKETS ARTS & CRAFTS ON DISPLAY SAWMILL MARKET NEW MEXICO’S FOOD HALL HOTELS & RESORTS MAGAZINE 2023

visit the new concepts at New Mexico’s premier Food Hall Sun-ThU 8am-9pm Fri-Sat 8am-10pm | 1909 bellamah ave. NW, Albuquerque SaWmillmarket.com

Little Madrid

Flora Restaurant

West Cocktail & Wine Bar

Mercantile Cafe

JIM LONG Heritage Hotels

Publication Editor

MOLLY RYCKMAN

Heritage Hotels

Publication Art Director

SARAH FRIEDLAND

Contributing Writers

SUSANNAH ABBEY

ASHLEY M. BIGGERS

NICOLASA CHAVEZ

APRIL GOLTZ

MAYRA ERRIN JONES

KELLY KOEPKE

STEVE LARESE

DEBORAH MADISON

CHRIS WILSON

Contributing Photographers

JEFF CAVEN

STEVE LARESE

DOUGLAS MERRIAM

EMILY OKAMOTO

Dear Guest:

Thank you for selecting Heritage Hotels & Resorts for your stay in New Mexico. Our mission is to share the history and culture of our state with each visitor. When you choose to stay at a Heritage Hotel, you are greatly contributing to this noble purpose. Since a portion of your room stay is donated to our cultural partners to help ensure that New Mexico’s cultural legacy is preserved and advanced.

Currently, Heritage is overseeing the redevelopment of the Sawmill District in Albuquerque. Once home to a massive lumber business that operated in the early 1900s, the area holds great promise as one of the most unique urban districts in the country. It’s rapidly becoming one of Albuquerque’s most vibrant, eclectic neighborhoods, featuring artist studios and mixed-use buildings that are home to burgeoning businesses, entrepreneurial thinking, new attractions, and Sawmill Market, New Mexico’s first artisanal food hall, a 34,000-square-foot space featuring Little Madrid and more than thirty unique dining options.

Heritage Hotels & Resorts supports the artistic community that underscores New Mexico’s unmatched cultural community. The New Mexico Artisan Market, International Folk Art Market, Traditional Spanish Market & Contemporary Hispanic Market, and Indian Market all contribute to making New Mexico one of the strongest art destinations in the United States.

In nearly every village and city in New Mexico, you’ll find a plaza—a gathering

place that hosts religious ceremonies, ritual dances, festivals, and community life. Chris Wilson, a landscape architecture professor at the University of New Mexico, and photojournalist Miguel Gandert documented the state’s town centers and their importance to our culture, even in the 21st century.

Our teams are busy creating and supporting many cultural endeavors throughout New Mexico as well as working on exciting new offerings that will delight you in the future. None of this work would be possible without your visit to a Heritage Hotel. Thank you for your continued support of Heritage Hotels & Resorts.

Bienvenidos/Welcome

Jim Long Founder/CEO Heritage Hotels & Resorts, Inc.

HHANDR.COM 1

elcome 2023 Published by Heritage Hotels & Resorts, Inc. 201 Third St. NW, Ste. 1140 Albuquerque, New Mexico 87102 Phone: 505-314-5152 media@hhandr.com hhandr.com

W

Publisher/CEO

HOTELS & RESORTS MAGAZINE

HERITAGE

Features

6 12 36

THE SAWMILL MARKET EXPERIENCE

Discover New Mexico’s premier food hall.

HOTELS & RESORTS ACROSS NEW MEXICO

Plan your next New Mexico trip—explore Heritage Hotels in Taos, Santa Fe, and Albuquerque.

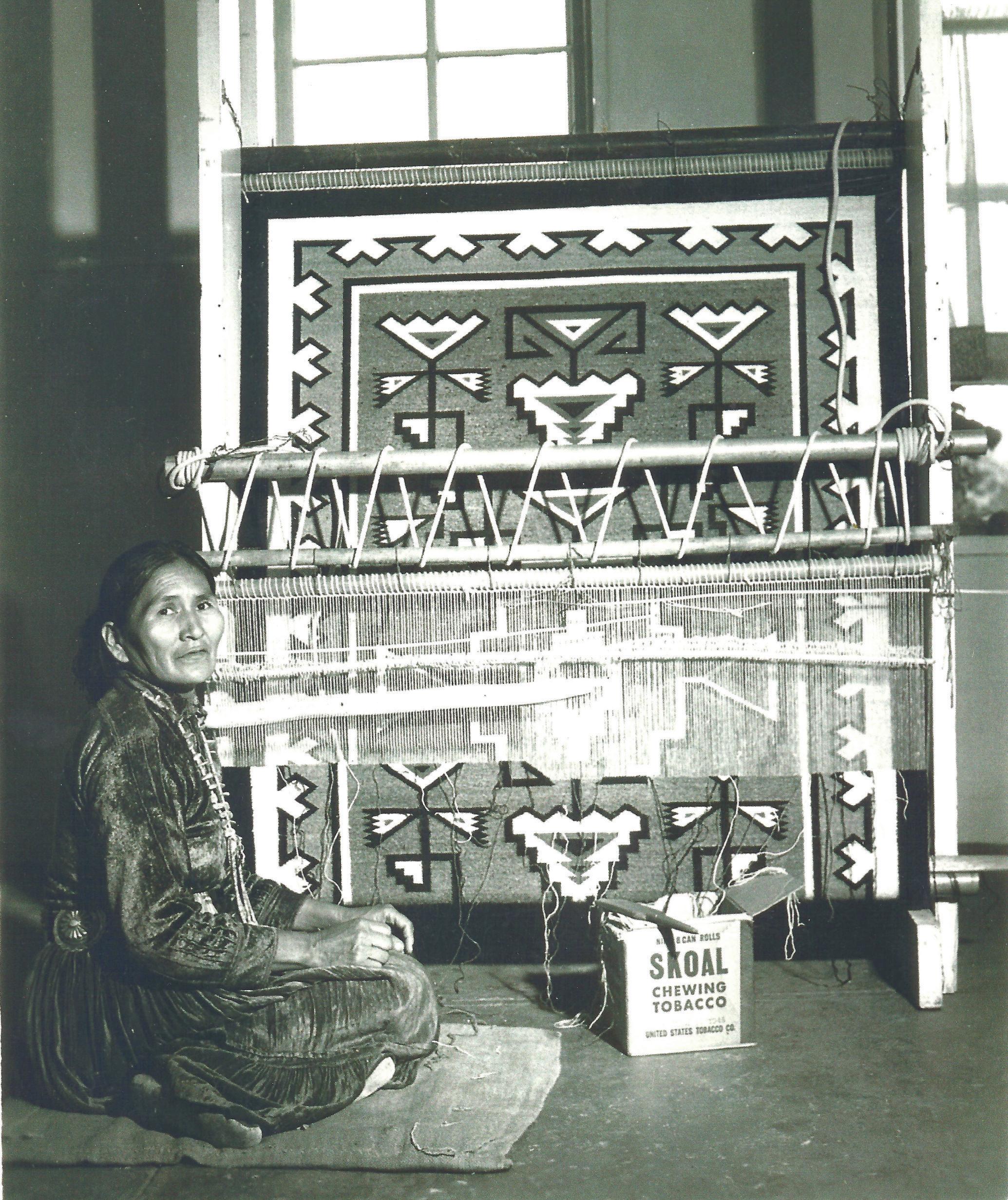

WEAVING HISTORY

by Susannah Abbey

One Navajo trading post honors the past, present, and future of an ancient art.

48 54 42

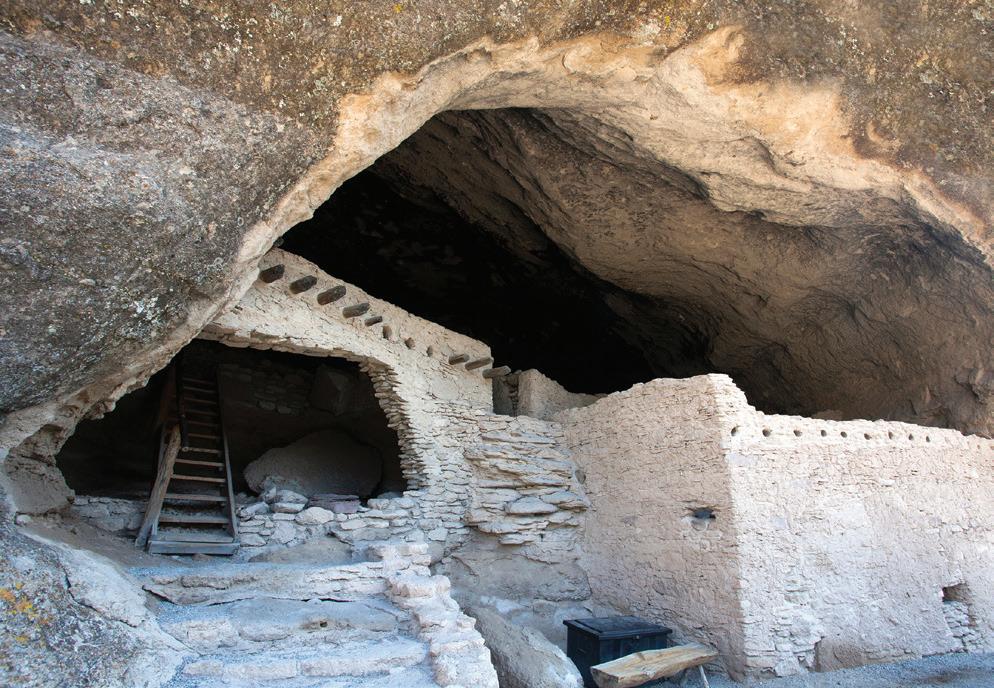

REDISCOVERING THE CENTER OF THE ANCIENT WORLD

by Ashley M. Biggers

Chaco Canyon’s vast complex of ruins provides a glimpse into the ancient people who lived there.

CHIMAYÓ’S CHILE CULTURE

By Deborah Madison

This northern New Mexico community grows a landrace chile with unmistakable character. Plus: In search of the perfect enchilada? Head to Estevan Restaurante.

GATHERING PLACES

By Chris Wilson

2 HHANDR.COM

6

Historic town centers are still New Mexico’s gathering places. PATRICK COULIE

Also in This Issue

1 WELCOME

4 TOURING NEW MEXICO

Heritage Inspirations offers authentically-curated guided tours.

10 ESSENTIAL FLAVORS OF LITTLE MADRID

A taste of Spain can be found at Sawmill Market Food Hall in Albuquerque.

18 THE MYSTERY OF LORETTO CHAPEL by Kelly Koepke

A Santa Fe landmark has a compelling and mysterious—history.

22 LA EMI by April Goltz

New Mexico–based dancer La Emi journeys through the state’s flamenco landscape.

24 ECHOES OF THE PAST

by Marya Errin Jones

New Mexico’s colorful mixture of cultures has a distinctly Spanish design flair.

28 AT THE ROOTS by Nicolasa Chavez

Chile, chocolate, and wine have long histories in North America

32 SHOP THE MARKETS by Steve Larese

Markets showcase Native American, Spanish Colonial, folk art, and New Mexico’s finest arts and crafts.

60 POOLSIDE PARADISE

Heritage Hotels & Resorts distinct collection of swimming pools.

62 NEW MEXICO DINING GUIDE

64 NEW MEXICO BUCKET LIST

HHANDR.COM 3

24 DOUGLAS MERRIAM 60 10 THINKSTOCK EMILY OKAMOTO

Touring New Mexico

Heritage Inspirations offers authentically-curated guided tours

HERITAGE INSPIRATIONS TOURS DIVE DEEP into the vibrant history, people, cultural sites and traditions, and awe-inspiring natural wonders of New Mexico. With more than twenty plus itineraries across Taos, Santa Fe, and Albuquerque regions and beyond, you can choose from active outdoor expeditions, E-Bike tours, walking tours, unique culinary experiences, glamping adventures, and more. These travel programs take you off the beaten path for a rich New Mexico experience. For tour details visit HeritageInspirations.com or call 1-888-344-TOUR (8687).

featured Taos Half Day Cultural Tour

MEETS

El Monte Sagrado

317 Kit Carson Road, Taos

TIMES OFFERED

April-Dec, Thurs-Sun, 9am-1pm

INCLUDES

Transportation, entry Taos Pueblo & museum, water, snacks & guide.

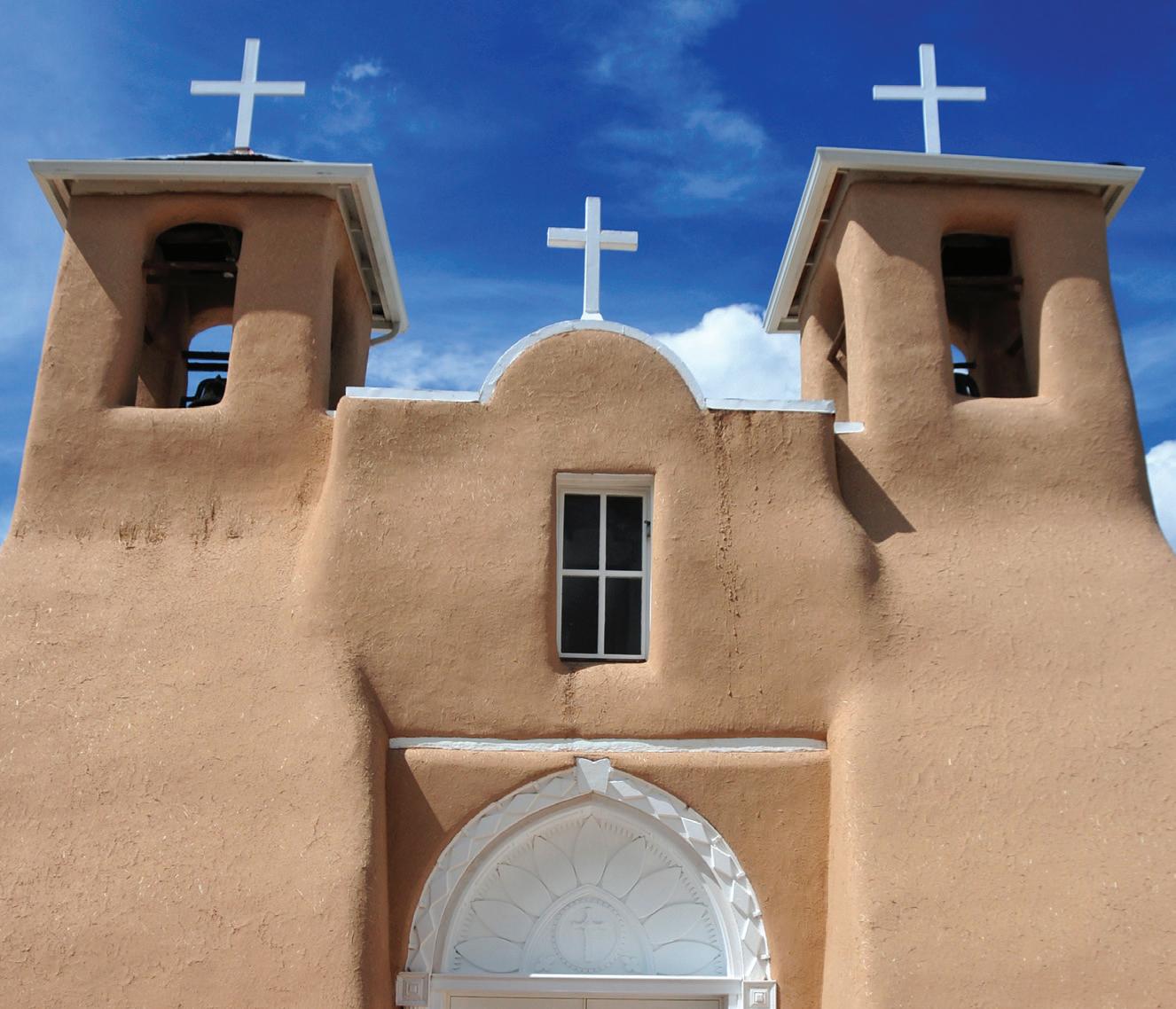

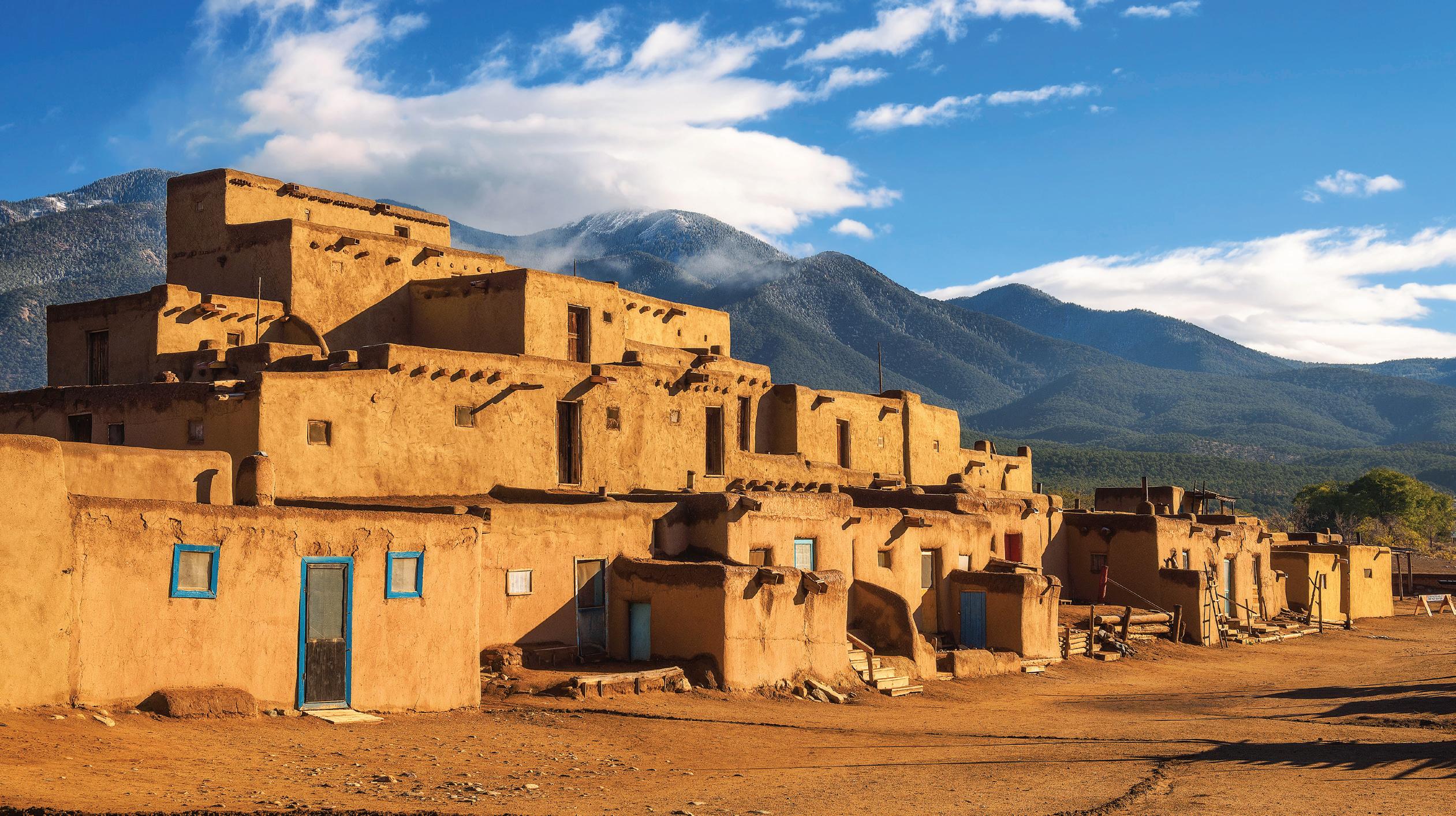

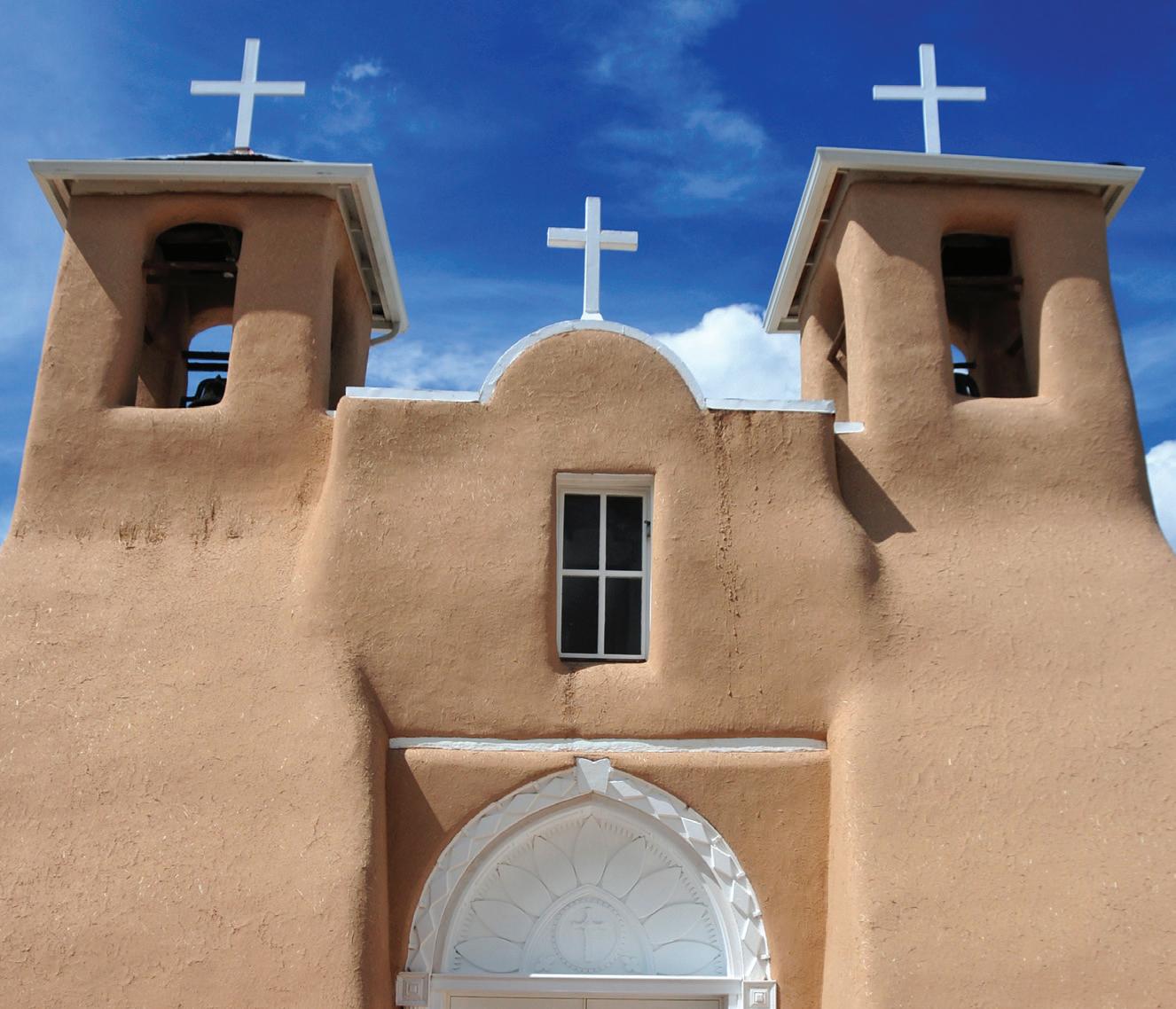

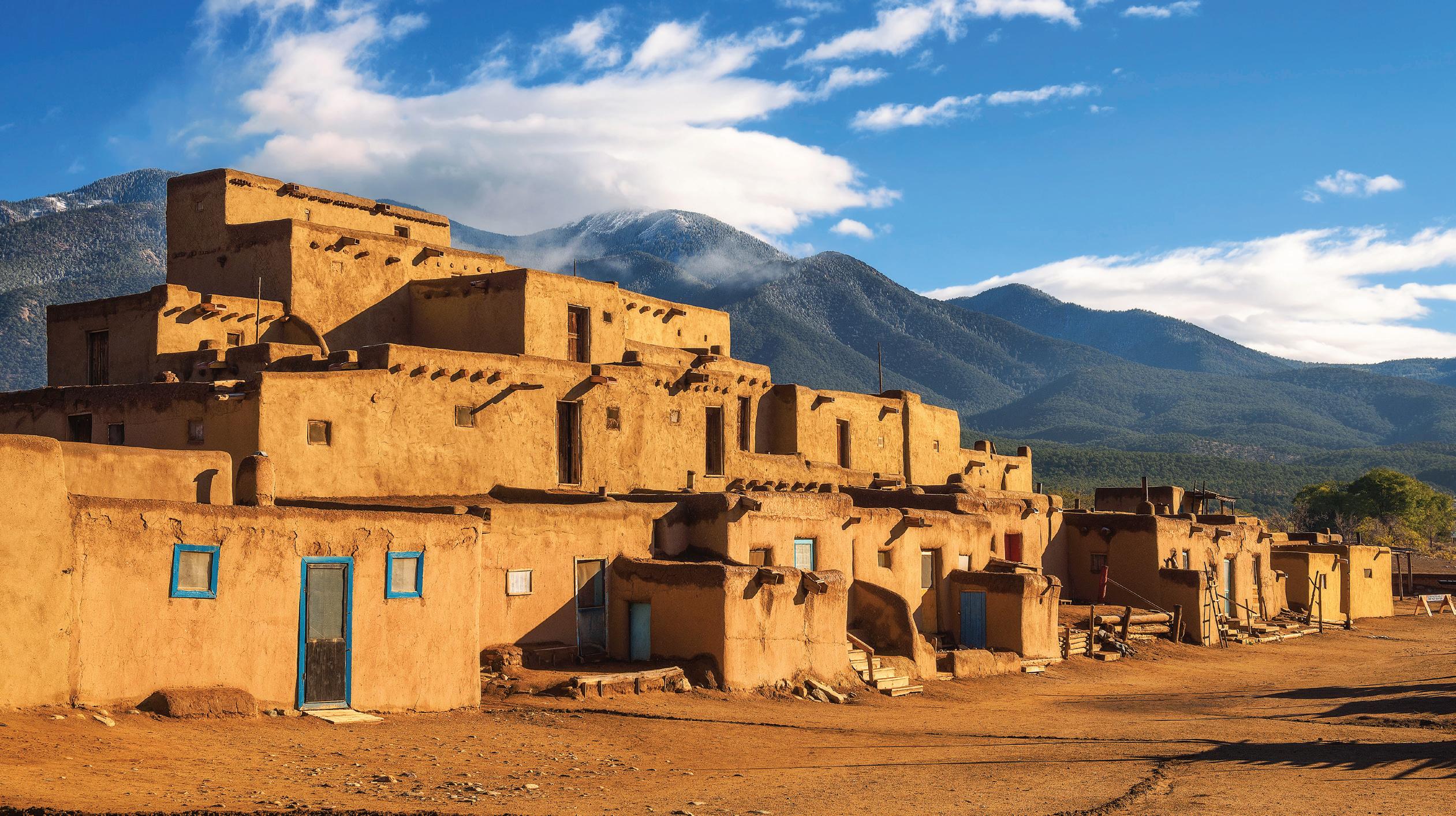

Experience a guided tour of Taos Pueblo, the UNESCO World Heritage Site. Journey also includes a trip to the majestic Taos Gorge, a stop at Hacienda de los Martinez, and a visit to the storied San Francisco de Asís Church.

4 HHANDR.COM

Taos Pubelo

ISTOCK

featured The City Different E-Bike Tour

MEETS

Inn and Spa at Loretto

211 Old Santa Fe Trail, Santa Fe

TIMES OFFERED

Mar-Nov, Tues-Sun, 8:30am-12pm

April-Oct, Tues-Sun, 2pm-5:30pm

INCLUDES

E-bike transportation and guided tour

Explore Santa Fe on an e-bike and explore hidden corners and cover more ground than you would on a walking tour. Stops include Cross of the Martyrs, historic downtown neighborhoods, Canyon Road, Museum Hill, and more.

featured

Chaco Canyon Day Tour

MEETS

Hotel Chaco, Equinox Bar 2000 Bellamah Ave. NW., Albuquerque

TIMES OFFERED

March-Nov, Saturdays, 7:15am-5:45pm

INCLUDES

Transportation, lunch, & guided tour

Visit this UNESCO World Heritage Site and National Park in Northwestern New Mexico and learn about the diverse culture that thrived here from 850 A.D. to 1250 A.D. Experience this major ancestral Puebloan center of migration, grand construction, and cultural integration to see why Chaco Canyon is a unique and fascinating place of mystery.

HHANDR.COM 5 THIS PAGE AMANDA POWELL FOR HERITAGE INSPIRATIONS

Chaco Canyon

Santa Fe E-Bike tour

6 HHANDR.COM DOUGLAS MERRIAM

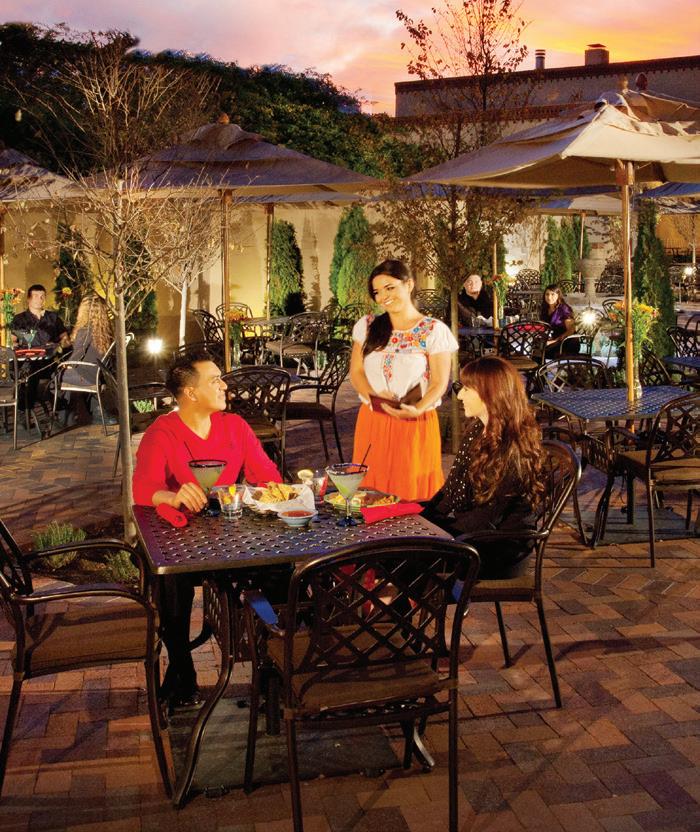

The Sawmill Market Experience

SAWMILL MARKET’S SETTING IS A LARGE PART of what makes it special. The vision was to create a citywide living room, where travelers and Albuquerqueans gather, and where residents from the neighboring apartments walk for breakfast, lunch, or dinner. At Sawmill Market, people can grab a meal, stay for entertainment in The Yard, and linger over desserts and cocktails. The communal seating areas foster this vibe, as does The Yard, an all-season outdoor dining and play space where fun is to be had throughout the year.

It’s all part of this former lumber and industrial hub’s redevelopment, as the Sawmill District evolves into a thriving center—with Sawmill Market leading the way. With thirty-two different concepts, Sawmill Market focuses on local experiences. You will not find any chain restaurants, only New Mexico owned businesses, each with a unique concept.

Wandering the market is like taking a homegrown, global culinary tour, from Hiro Sushi to Kulantro’s Vietnamese street fare to Roti’s rotisserie chicken to XO Waffle’s authentic Liége Belgian waffles with a New Mexican twist. The mercado section has authentic Mexican flavors from Flora, Churro y Corn, and the Paleta Project. Take your tastebuds on a tour of Spain by visiting Little Madrid, Sawmill Market’s homage to the famous Mercado San Miguel in Spain (see Essential Flavors of Little Madrid on page 10).

The family-owned Meso Grill brings Mediterranean cuisine to the market and Notorious P.O.K.E serves fresh poke bowls. If you need a pick-me-up, Plata Coffee features locally roasted coffee and hand-blended small-batch teas.

Local farm sourced ingredients are front-and-center at Mercantile Café, a farm-to-table restaurant, and West Cocktail & Wine Bar, which features house-made charcuterie and local wines. Over

HHANDR.COM 7

Mercantile Café EMILY OKAMOTO

thirty local beers are on tap at Paxton’s, as well as cocktails and craft root beer. Fresh ingredients are also at the forefront of Botanic Bar, a mini-bar within a greenhouse-like space in the center of the market. Mixologists create cocktails and mocktails with locally sourced herbs and botanicals, house-made shrubs, and other handcrafted ingredients. Red and Green is the market’s New Mexican restaurant featuring local favorites like green chile stew, huevos rancheros, Frito pie, and enchiladas.

Some restaurateurs launched their first brick-and-mortar locations at Sawmill Market. Two examples are Cacho’s Latin Flavor, which serves Venezuelan food, and Tulipani Pasta, offering small-batch, organic fresh pastas. HAWT Pizza Co. landed its mobile catering company at Sawmill Market. Using a massive, red-tiled, 100-percent woodfueled oven, HAWT dishes out artisan pizza and paninis.

Santa Fe hotspot Dr. Field Goods opened its first Albuquerque location at Sawmill Market with burgers, hot dogs, sausages, its signature patatas bravas, Chef Josh Gerwin’s version of red or green chile

cheese fries—as well as a butcher shop. “This location allows me to realize the concept of butcher shop and restaurant as one cohesive business while partnering with others in the market as a community to cultivate our collective success so we can offer an unprecedented customer experience,” says Gerwin.

Looking for something lighter? Head over to Rush of Prana to experience bright and flavorful vegan smoothies and açaí bowls or the market’s “grown up” lemonade stand, Lemon & Brine, serving the quirky combination of homemade lemonade and pickles.

Have some fun when you visit Neko Neko, serving Taiyaki, a Japanese fish-shaped cake, filled with soft-serve ice cream and topped with sweet treats. Try the adult soda fountain to satisfy your sweet tooth with boozy beverages and decadent sugary delights made to indulge in.

Sawmill Market is located in the emerging Sawmill District, across from Hotel Chaco and Hotel Albuquerque at Old Town. For more information visit SawmillMarket.com

8 HHANDR.COM

PATRICK COULIE

Outdoor Dining in The Yard at Sawmill Market

HHANDR.COM 9

A Salad from Mercantile Café

Hiro Sushi

Taiyaki from Neko Neko

Paxton’s Taproom

West Wine & Cocktail Bar

RIGHT, EMILY OKAMOTO, ALL OTHER PHOTOS THIS PAGE, DOUGLAS MERRIAM

Kulantro’s Noodle Bowl

Essential Flavors of Little Madrid

SINCE OPENING IN FEBRUARY OF 2023, Little Madrid has become a local favorite at Sawmill Market in Albuquerque. The menu includes a selection of authentic Spanish dishes like paella and tapas—all made in-house using recipes that include the long-standing traditions, cooking methods, and ingredients of true Spanish fare. The menu also includes expertly curated wines and beers that pair beautifully with each menu item.

Some essential items to try are the specialty paellas such as squid ink paella and New Mexican paella which features green chile. Not to be missed is the thinly sliced Jamón Ibérico (traditionally cured Spanish ham). Regional tapas, including pulpo of Galicia, a dish of perfectly cooked octopus, albondigas (meatballs), and a pintxos (small snack) of guindilla peppers and chorizo can also be found on the menu. Basque Cheesecake, famous for its creamy center and caramelized-burnt top and bottom is the perfect way to complete your tour of Spanish cuisine. The authentic flavors of Little Madrid will surely transport you to Spain for a memorable experience.

10 HHANDR.COM

ALL PHOTOS THIS SPREAD BY EMILY OKAMOTO EXCEPT LEFT BY JEY BERNAL

Paella Mar y Tierra

HHANDR.COM 11

Pulpo a la Gallega

Basque Cheesecake

New Mexican Paella Albondigas

Pintxos - Guindilla Peppers and Chorizo

HOTELS & RESORTS ACROSS NEW MEXICO

El Monte Sagrado

El Monte Sagrado

HERITAGE HOTELS & RESORTS, Inc. embodies the culture, spirit, and traditions of New Mexico. Explore New Mexico along the cultural corridor and discover what makes New Mexico the Land of Enchantment.

El Monte Sagrado, Taos

El Monte Sagrado means “The Sacred Mountain.” The name of this AAA Four-Diamond property reflects its lush sanctuary setting, which nurtures mind, body, and spirit. This resort features 84 uniquely designed guest rooms, an award-winning spa, restaurant, bar, indoor pool, and hot tub. The perfectly manicured grounds make this mountain

spa retreat an oasis only a few blocks away from the town of Taos’s historic plaza. ElMonteSagrado.com

Inn and spa at loretto, Santa Fe

This AAA Four-Diamond resort epitomizes the intrigue of northern New Mexico through artistic design and worldclass accommodations. It is the most photographed building in the state with a premier location in the heart of Santa Fe’s historic Plaza. This resort features 136 wellappointed suites and guest rooms, an award-winning spa, hair and nail salon, casual fine dining, and a heated garden pool, as well as many unique on-site galleries and boutiques. HotelLoretto.com

HHANDR.COM 13

Inn and Spa at Loretto

DOUGLAS MERRIAM

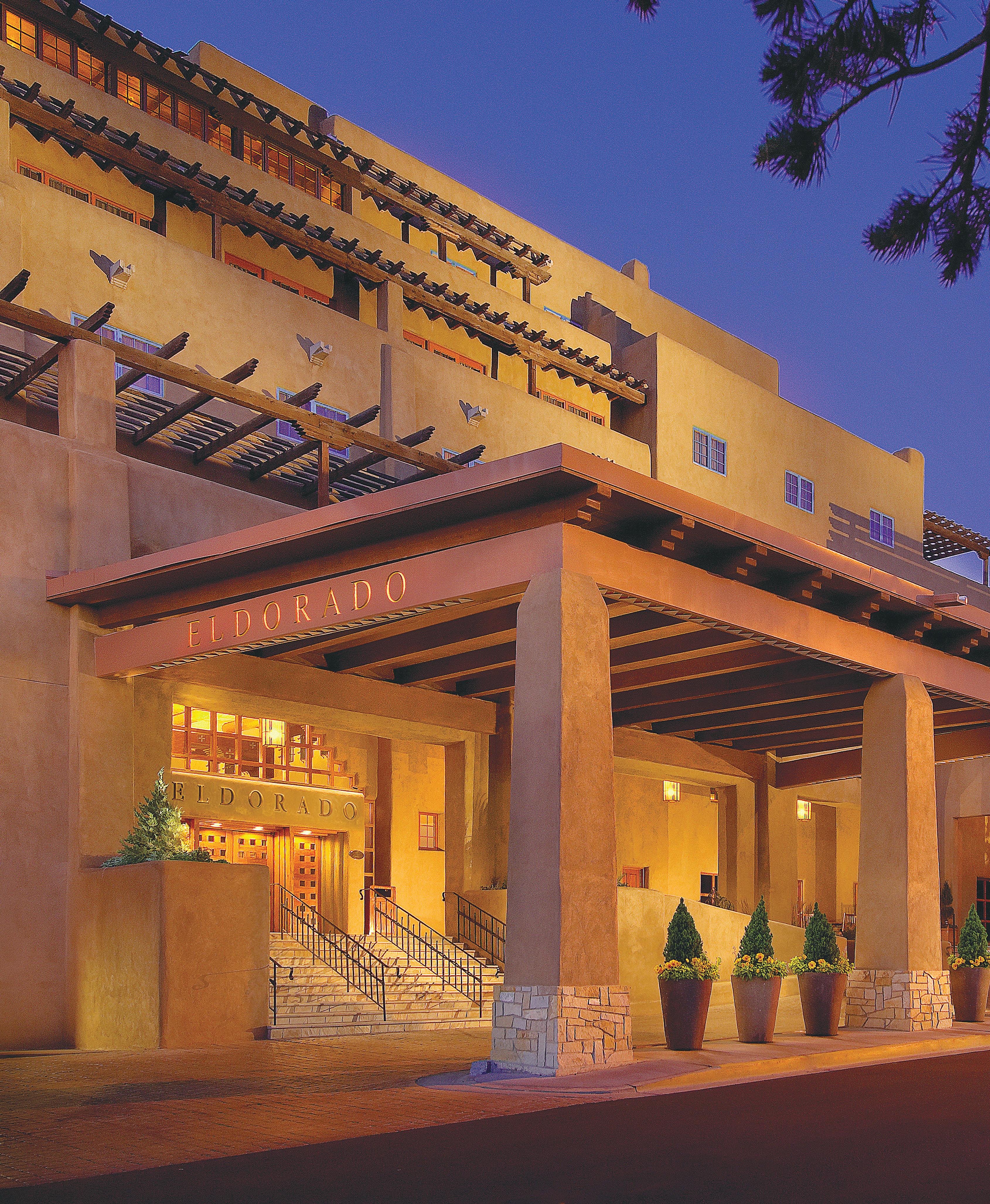

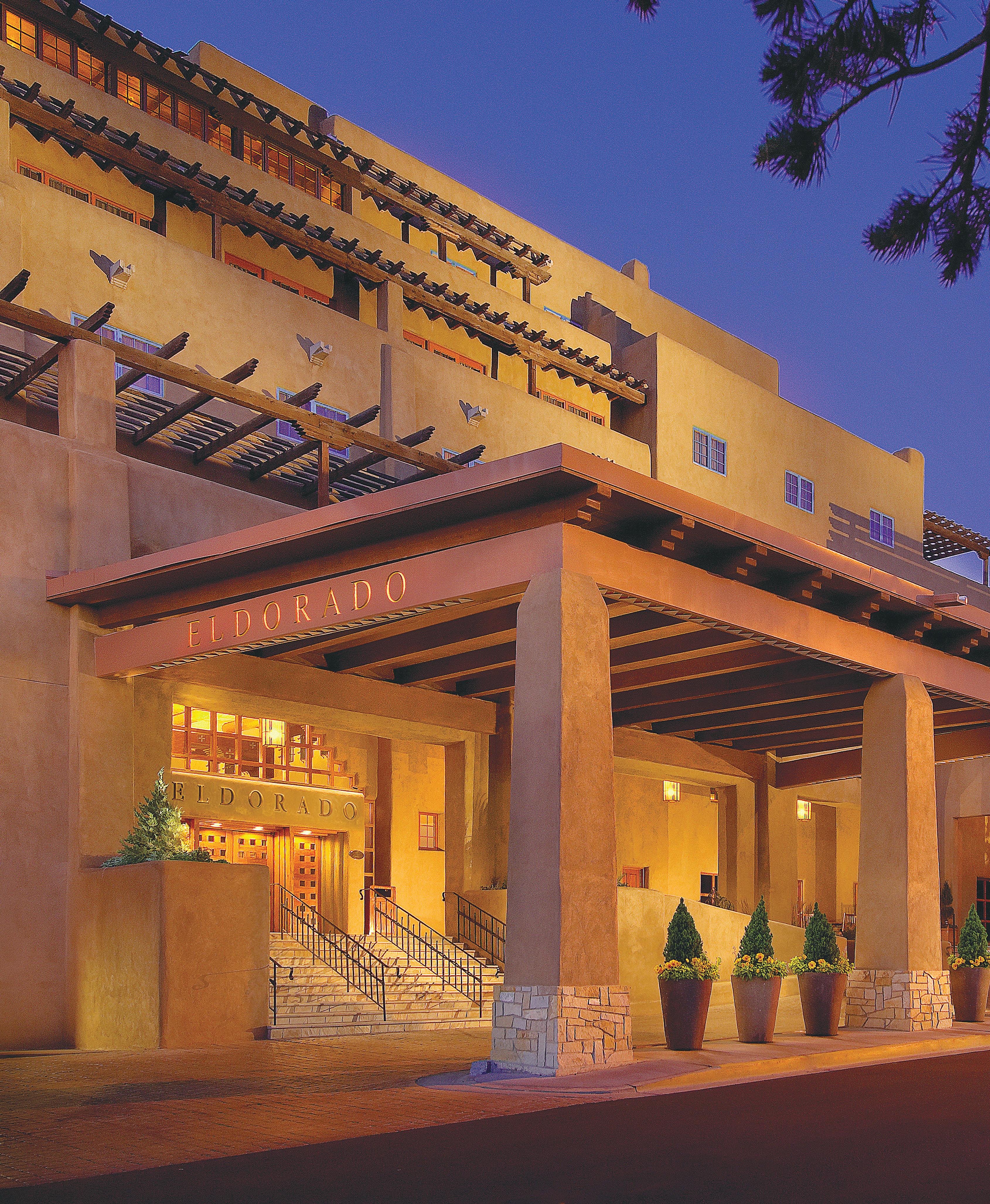

Eldorado Hotel & Spa, Santa Fe

Just steps away from the historic Santa Fe Plaza, this AAA Four-Diamond hotel and spa celebrates centuries of tradition and culture in a bold expression of design and creativity. Eldorado Hotel & Spa offers Santa Fe’s most exclusive rooftop pool, bar, event space, restaurant and spa. EldoradoHotel.com

Hotel St. Francis, Santa Fe

Named for the patron saint of Santa Fe, the historic Hotel St. Francis embodies the authentic spirit of old Santa Fe. The décor features handcrafted wood furniture by local artisans inspired by the Palace of the Governors and reflecting

the days of Santa Fe’s early Franciscan missionaries. It is the oldest hotel in Santa Fe and is located one block from the Plaza. This property features the award-winning Market Steer Steakhouse, Secreto Lounge, and the famous Gruet Tasting Room. HotelStFrancis.com

Hotel Chimayó de Santa Fe

Nestled in the heart of downtown Santa Fe, just steps from the historic Santa Fe Plaza, Hotel Chimayó de Santa Fe offers an authentic escape. Inspired by more than 400 years of artistic tradition, this hotel welcomes guests by celebrating the history of the Village of Chimayó. Featuring Low ‘n Slow Lowrider Bar with HAWT Pizza. HotelChimayo.com

14 HHANDR.COM

Hotel St. Francis

DOUGLAS MERRIAM

HHANDR.COM 15

Eldorado Hotel & Spa

16 HHANDR.COM

Hotel Chaco

Hotel Chaco, Albuquerque

Situated in the heart of Albuquerque in the Historic Old Town and new urban Sawmill District, Hotel Chaco is a AAA Four-Diamond boutique hotel that beckons luxury travelers seeking authentic experiences. The unique room layouts are designed by world-famous architecture firm Gensler and feature authentic interior design with the best collection of contemporary Native American art. Dine at Level 5, the city’s most exclusive restaurant with 360° views of the city. Stop by Crafted for wine and spirits tastings or visit the spa for a truly pampering experience. HotelChaco.com

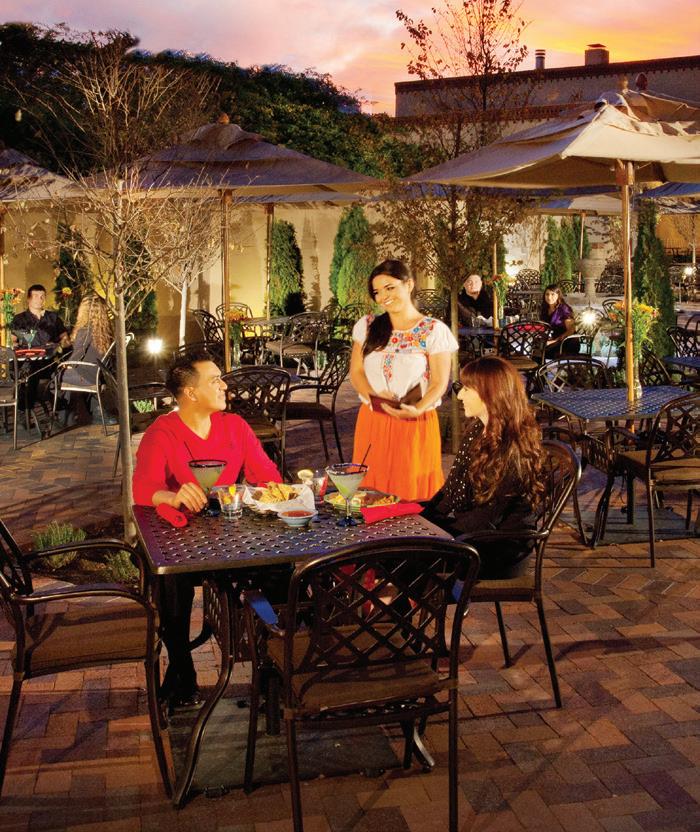

Hotel Albuquerque at Old Town

Hotel Albuquerque at Old Town welcomes guests with a distinctive blend of historic grandeur and contemporary comfort. Drawing inspiration in design from the region’s rich Hispanic heritage, Hotel Albuquerque at Old Town

is a destination that seamlessly blends cultural influence with modern amenities. Located in the heart of Old Town and Sawmill Districts, this property features the state’s most beloved New Mexican Restaurant, Garduño’s, and QBar Lounge. HotelAbq.com

The Clyde Hotel, Albuquerque

A 20-story landmark hotel in the heart of Albuquerque’s Civic Center offers business and leisure travelers a place of connection, comfort, and engagement. Guests are welcomed with a distinctive blend of Pueblo Deco design with a touch of western grittiness and eastern elegance. This property features Carrie’s Restaurant, 1922 Bar & Lounge, and a rooftop pool. The Clyde Hotel offers exceptional accommodations and immediate access to The Albuquerque Convention Center, Civic Center municipalities, restaurants and shops, all within walking distance of the hotel. ClydeHotel.com

HHANDR.COM 17

Hotel Albuquerque at Old Town

DOUGLAS MERRIAM

THINKSTOCK

The Loretto Chapel’s mysterious staircase seems suspended in space.

The Mystery of Loretto Chapel

Is it a builder’s genius or divine intervention?

EVERYONE LOVES A GOOD STORY. The Gothic-style Loretto Chapel in the heart of downtown Santa Fe is the source of three mysterious tales surrounding its spiral staircase. The staircase seems to hang unsupported, without a center post or other architectural structure holding it in place.

First, some history. In 1852, the Catholic Archbishop Jean-Baptiste Lamy, living in Santa Fe, sent out a plea for pilgrims and missionaries to spread the faith through the new territories. Consequently, a handful of nuns from the Sisters of Loretto made the arduous journey, arriving in Santa Fe to establish a girls’ school; the Academy of Our Lady of Loretto opened in 1853. The academy closed in 1968, and the property sold a few years later. Today, Heritage Hotels & Resorts’ Inn and Spa at Loretto is on the site of the old academy.

In the 1870s, as the construction of the Cathedral of St. Francis was winding down just a block away, Lamy suggested that the builder, French architect Antoine Mouly, also erect a chapel for the sisters. He modeled it after Sainte-Chapelle in Paris. The Loretto Chapel, completed in 1878, hews to the Gothic Revival style, complete with spires and buttresses. The colorful stained-glass windows were ordered from Paris, while the sandstone was quarried near the town of Lamy, about 20 miles from Santa Fe.

But there was a problem with the little chapel. Mouly’s plans neglected to include access to the choir loft, some 22 feet above the chapel floor. Then he died. The sisters sought a local carpenter to build them a staircase that would not take up

By Kelly Koepke

too much of the chapel’s small footprint, but they couldn’t find anyone. And they rejected the idea of using a ladder, preferring a less strenuous way to access the loft.

MYSTERY NUMBER ONE: WHO BUILT THE STAIRCASE?

Years later, or so legend recounts, the devout sisters prayed for nine days to St. Joseph, patron saint of carpenters, for a solution to their problem. Afterward, a mysterious, gray-haired stranger appeared on a burro. He had only one requirement: complete privacy to build the staircase. Stories differ as to how long the old man stayed—one night, three months, nine months—but they all end the same way: the stranger disappeared without being paid, leaving behind 33 beautiful, tightly spiraled steps that climb precipitously from floor to loft.

The mother superior claimed she didn’t know who built the staircase, and no mention of supplies or workers for the project exist in her meticulous records. Was the mysterious man St. Joseph himself, answering the sisters’ prayers? Was he simply an itinerant carpenter looking for work? Or, as local historian Mary Jean Straw Cook posits, was he

COURTESY PALACE OF THE GOVERNORS PHOTO ARCHIVES (NMHM/DCA), PA-MU-263.01

The Sisters of Loretto sought a carpenter to build a staircase that was forgotten in the architect’s original design.

COURTESY PALACE OF THE GOVERNORS PHOTO ARCHIVES (NMHM/DCA), PA-MU-263.01

The Sisters of Loretto sought a carpenter to build a staircase that was forgotten in the architect’s original design.

HHANDR.COM 19

Francois-Jean Rochas, an expert woodworker who had done other carpentry projects around Santa Fe? Straw Cook discovered a logbook entry from the mother superior to support the theory: “March 1881: Paid for wood Mr. Rochas, $150.00.”

MYSTERY NUMBER TWO: HOW DOES THE STAIRCASE STAY UP?

Mystery number two is how the staircase stands. When built, it had no visible means of support— no center pole and no attachment to the wall. (The current railing and a bracket fastening the staircase to a nearby pillar were added in 1887.) However,

the fact remains that the stairs stood unsupported for years, the sisters using them without incident.

The design is, even to this day, as innovative as it is beautiful. The carpenter used only square wooden pegs—no nails or glue—to fasten the pieces together. Theories abound, offered up by architects, engineers, and physicists, as to how the staircase previously stood without support. Some point to the double-helix shape, the small diameter of the inner spiral (which could act as a center pole) and the pegs, all of which give strength and stability, despite a disconcerting bounce when weight is placed on the steps.

A paper published recently in Physical Review Applied by David Tománek of Michigan State University and Arthur G. Every of the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, analyzed the helical coil structure of the staircase. The professors’ conclusion is that the very design of the spirals is what provides its stability.

But Every, in an email to Loretto Chapel curator Richard Lindsley, stated, “Being able to describe the physical origin of the rigidity of the staircase does not make it less miraculous. It makes it more miraculous in my mind, since the builder would have to be more ingenious than all civil engineers so far!”

MYSTERY NUMBER THREE: WHAT IS THE STAIRCASE MADE OF?

The last mystery of the miraculous Loretto Chapel staircase has to do with the kind of wood the stranger used to build it. The short answer is spruce. But the devil—or in this case, the miracle—is in the details.

In 1996, after analyzing a wood sample taken from the staircase, wood technologist Forrest N. Easly concluded that the density of the material does not match any kind of known spruce. In fact, the wood is so dense, it has the properties of a hardwood—but spruce is a softwood. So where did the wood come from?

A mystery, indeed. Whatever your take on the mysteries of the Loretto staircase, the structure is beautiful, elegant, and an intriguing part of the City Different.

The Gothic Revival–style chapel is modeled after Sainte-Chapelle in Paris.

THINKSTOCK

20 HHANDR.COM

New Mexico Weddings by Heritage Hotels & Resorts

TAOS El Monte Sagrado Living Resort & Spa

SANTA FE Eldorado Hotel & Spa, Inn and Spa at Loretto

ALBUQUERQUE Hotel Chaco, Hotel Albuquerque at Old Town, The Clyde Hotel

LAS CRUCES Hotel Encanto de Las Cruces HHandR.com/Weddings

Emily Okamoto

Blue Rose Photography Studios

Emily Okamoto

Tony Gambino Photography

La Emi

New Mexico’s Flamenco Star

By April Goltz

ALIFETIME DEVOTED TO THE ART of flamenco is bearing fruit for Santa Fe, New Mexico–based dancer La Emi. A prominent performer, teacher, and organizer in the city’s flamenco scene, the New Mexico native is experiencing one of life’s full circles, as she prepares for another residency on the same stage where she witnessed her first flamenco show as a child. La Emi recalls her formative impressions of local flamenco icon María Benítez and company, performing at The Benítez Cabaret at the Lodge in Santa Fe in the mid-1990s. The intense sights and sounds of flamenco consumed La Emi, and she was enrolled in María Benítez Institute for Spanish Arts by age four. Her father managed ticketing at the Lodge for Benítez’ shows throughout La Emi’s early childhood, and at ten, she performed there with the Institute’s youth company, Flamenco’s Next Generation. This year, will be the sixth year of her performing her show onstage at the Lodge.

in its recognized form emerged at the end of the nineteenth century. Most American audiences first saw it from touring companies of Carmen Amaya and Pilar Lopez, aided by Hollywood’s exotification of early global flamenco stars in the post-WWII American imagination. In central and northern New Mexico, the seeds of flamenco germinated in receptive soil, ultimately producing a vibrant, thriving, home-grown flamenco culture.

Like many of her colleagues, mentors, and predecessors, La Emi feels that flamenco expresses something intrinsic to New Mexican identity: “Flamenco is an expression of the people, for the people. In our culture in northern New Mexico, we can tell our story through this art form.”

La Emi performs througout the Summer, Fall, and Holiday Season at the Lodge at Santa Fe. For more information visit HHandR.com

La Emi has dedicated herself to an art form whose aesthetic, sound, and sensibility have found resonance and expression in New Mexico since at least the early 1940s. Originating in Gitano (Spanish Gypsy) communities in Andalucía, flamenco

Flamenco’s strong local presence highlights a profound kinship between Chicano and Gitano, Hispano and Spanish cultural and aesthetic values. And in keeping with the artform’s tradition in New Mexico, Spain, and beyond, La Emi’s relationship to flamenco is born from and reinforced by family, community, and landscape.

Even on the global scale, flamenco is a small, tightly knit world, and it is important to acknowledge upon whose shoulders one stands. La Emi comes out of a complex historical

22 HHANDR.COM

THIS PHOTO AND RIGHT PAGE BOTTOM, EMILY OKAMOTO

tangle of regional and global flamenco figures that, when unraveled, casts her personal and professional trajectory as something akin to fate.

Among the earliest flamenco artists in Santa Fe was a dancer named Vicente Romero, born in 1939. As a teenager, Romero was inspired by the film Sombrero featuring Italian-born, American flamenco dancer Jose Greco. Greco had gotten his start dancing with Pilar Lopez in the 1940s before forming his own company. Vicente Romero toured with Greco for several years before returning to Santa Fe in the 1960s, where he was part of a burgeoning scene that included La Emi’s future first teacher, María Benítez .

By the 1990s, Jose Greco’s son, Jose Greco II, had taken up the mantle, and was touring internationally with his own company. Vicente Griego, New Mexico’s now critically acclaimed cantaor (flamenco singer) and La Emi’s longtime mentor and collaborator, was just beginning his study of flamenco cante while stage managing for Greco II. Griego had grown up near La Emi’s family, and became her godfather when she was a baby. Twenty years later, when La Emi was ready for an extended period of study in Spain, Griego sent her to Jose Greco’s daughter, the celebrated dancer Carmela Greco. Carmela took La Emi on as her student, acting as her maestra ever since. On her relationship with Carmela, La Emi is reverent: “Carmela is amazing … She has taken me in, and not only is she teaching me about the dance, but she’s teaching me about my camino in life … She has such a big heart, and with every single student and audience member, she gives everything she has. I aspire to follow in that way.”

La Emi is thrilled and awed at what she sees as a divine plan for her, and she overflows with gratitude for her community that has provided vital support in manifesting it. In 2014, she launched her own dance company, EmiArteFlamenco, and in 2017 she founded both EmiArteFlamenco Academy, a school for students of all ages, and Flamenco Youth de Santa Fe, a children’s company that performs for communities all around New Mexico. La Emi glows when she speaks about her work with children. Giving back to the community is at the root of her life’s work, and her connection to home. For tickets to her shows at the Lodge at Santa Fe visit HHandR.com.

HHANDR.COM 23

La Emi’s work with children, including her Youth de Santa Fe performers, is central to her mission.

“Flamenco is an expression of the people, for the people.

In our culture in northern New Mexico, we can tell our story through this art form.”

Echoes of the PAst

by Marya Errin Jones

by Marya Errin Jones

New Mexico’s design ethos reflects the state’s cultural roots.

THINKSTOCK.COM

San Francisco de Asís Mission Church in Ranchos de Taos is an early example of Spanish Colonial architecture in the Southwest.

NEW MEXICO IS A RICH BRAID of ancient civilizations, modern cultural influences, and the spiritual life its citizens brought with them. And with the exception of the original 13 colonies in the east, there are few places in the United States so steeped in history carved from occupation, migration, and the enduring grace of artistic expression.

The march of Spanish conquistadors across the Americas left its mark on the Pueblo people who refused to be conquered. The culture of Mexico came with its own brand of resistance, and early communities such as Chaco Canyon and Taos Pueblo (both UNESCO World Heritage Sites) silently witnessed it all. The result is a cultural churning, evident in the architecture of New Mexico’s towns and cities, and in color palettes, textiles, and pottery that adorn our homes.

LIVING HISTORY

The year was 1598. That spring, the Edict of Nantes was signed by King Henry IV of France, astronomer Tycho Brahe published his catalog of 1004 stars, and the world-renowned sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini was born in Italy. That same year, Don Juan de Oñate, along with his expedition, stood along the south bank of the Rio Grande River, led his party in prayer, and then claimed

all of the territory across the river, bringing with them the unrelenting presence of the Spanish Crown and remnants of the papal Inquisition. The centuries to come were tumultuous to say the least. The founding of Santa Fe in 1610 brought wealth and commerce to the area, further establishing the strength of Spain. Much blood was spilt, culminating in the hard-fought battle for independence won by Mexico in 1821. The land was claimed from Spain, and the road of commerce we know as the Santa Fe Trail was established, bringing more wealth to the provinces, this time for Mexican landowners.

Over the course of the colonial years, myriad art forms were discovered and perfected, reflecting the Spanish Colo-

HHANDR.COM 25

The influence of ancient Taos Pueblo is evident in modern-day New Mexico architecture.

NEW MEXICO DEPARTMENT OF TOURISM NEW MEXICO DEPARTMENT OF TOURISM

Adobe bricks and vigas are still used in the design of many New Mexico buildings.

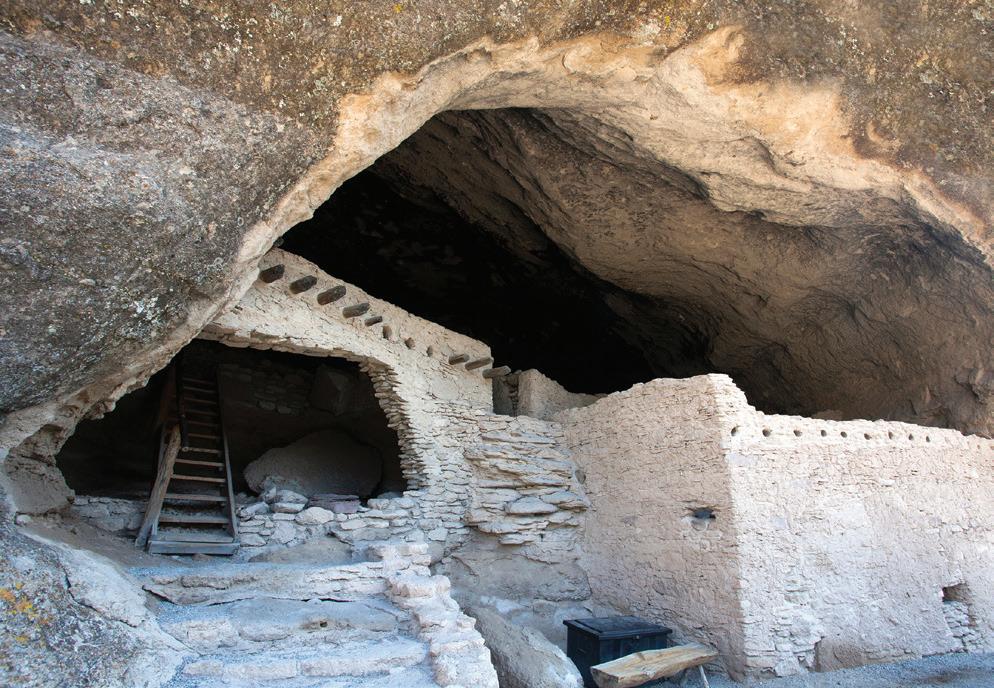

nial, Pueblo, and Mexican influences. The rough-hewn beams known as vigas, found in today’s traditional Pueblo Revival style, date back to the architecture of the ancient cliff dwellers at locales such as Bandelier National Monument and Mesa Verde National Park. The hacienda (Spanish for estate) is a colonial invention developed as a means to integrate market-based economy with the home and stronghold of the landowner, not unlike the plantations of the American South. The gilded, Spanish Baroque style of intricate tendrils, braids, and filigree can be seen throughout the delicate architectural touches through Southwestern design, married to the tinsmithing of Mexican milagros—the imprint of the past is everywhere present.

Let’s not forget the weaving: The fiber arts of northern New Mexico, once an art of the individual, were driven toward more commercial applications by the Spanish Crown itself. Today, the art of weaving continues to develop and evolve—it is the very definition of modern art.

By the time the modern age laid its railroad tracks through desert towns and along ancient trails bringing new settlers to the area in the 1880s, some of the most exquisite buildings were being constructed, and some of the finest craftspeople called New Mexico home. Today, Pueblo, Mexican, and Spanish colonial art is alive and well and available to tourists, collectors, and travelers alike.

FROM PAST TO PRESENT

Perhaps the finest examples of Southwestern design within public reach can be found at the Museum of Spanish Colonial Art in Santa Fe, the seasonal Spanish Market, and the locally owned Heritage Hotels & Resorts, Inc., which dedicates the design of each of its hotels to the vibrancy of New Mexican art across the state.

Simply stated, the Spanish Colonial Arts Society, founded in 1925 by author Mary Austin and artist/writer Frank G. Applegate, and its Museum of Spanish Colonial Art, is the only museum in the country dedicated to the exhibition and interpretation of art from the Spanish colonial period. From furniture to pottery, woodcarving to iron and tinwork, the Museum of Spanish Colonial Art in Santa Fe preserves the past, present, and future Southwestern art for all to behold.

As old as the Southwest itself is the act of weaving, a skill born of necessity that developed into a highly prized art form. Throughout the world, there are few places like the centuries-old village of Chimayó, known for its miracles of faith and of art. According to legend, some 5,000 churro sheep made the journey to New Mexico with the Coronado expedition in the 16th century, establishing an abundant supply of fiber needed for weaving that was already part of the daily life of those living from the land.

26 HHANDR.COM

Thick adobe walls and ladders can be seen in many New Mexican buildings.

MUSEUM OF SPANISH COLONIAL ART MUSEUM OF SPANISH COLONIAL ART NEW

BELOW: Tin light fixture, circa 1937, at Bandelier National Monument. RIGHT: A gallery at the Museum of Spanish Colonial Art in Santa Fe touches on the history of the Spanish in New Mexico and their influence on art, design, and architecture.

MEXICO DEPARTMENT OF TOURISM

Irvin Trujillo is a master weaver with Centinela Traditional Arts in the historic town of Chimayó. Trujillo is one of the art form’s most prolific artisans.

“[Weaving] is a part of life—it’s what I grew up with,” Trujillo says in a recent interview, “how life was in the old days.” Trujillo explains that due to Spanish Colonial influences, local weavers began to sell and trade blankets not only for survival during those high-desert winters, but for commercial gain.

Trujillo says that before the arrival of the Conquistadors and Spanish rule, weaving was a way of life and, as he says, “a path of discovery. Weaving has survived the changes in government—it’s still here—it has survived history and the many changes in history.”

The history of weaving in Trujillo’s family goes back seven generations. He learned to weave from his father and treasures the remnants of weaving his descendants left behind. “[The fragments] contain the old feeling,” he explains. “The spirit has stayed here—the weaving is a part of me; I grew up with the pieces from my grandmother and great-grandmother.”

Trujillo, also an engineer, explains that there is an art to interpreting the design of any piece. Unlike some weavers who repeat designs over and over, Trujillo never crosses the same river twice. He says that weaving, “is like playing jazz. I know all the scales. The overall appearance I don’t know. I have to be in the present. It’s a dynamic thing.” Each work comes from a unique inspiration. Trujillo adds that, “[each piece] has a piece of my spirit in it; where it goes from there, I don’t know. When I weave, I am putting my soul into it.”

Trujillo’s artwork, along with that of other craftspeople from the Centinela Chimayó Weavers, is part of the design and traditional beauty of the Heritage Hotels & Resort, Inc., property of Hotel Chimayó in Santa Fe.

From Pueblo Indian culture in Taos to the north, to the Spanish cultural and religious iconography in Santa Fe and Albuquerque, to the more Mexican-influenced Las Cruces to the south, the past reverberates through New Mexico.

Marya Errin Jones is an Albuquerque-based writer, social media strategist, traveler, curator, and creative nonfiction writer. You can find her at maryaerrinjones.com

HHANDR.COM 27 STEVE LARESE

Several hundred artists sell traditional Spanish Colonial art at Santa Fe’s Spanish Market.

Spanish Influence is seen throughout New Mexico in traditional woodworking techniques and crafts.

At the Roots

Chocolate, chile, and wine all have deep history in New Mexico

by Nicolasa Chavez

Chile was cultivated in Central America long before taking root in New Mexico. Now it is a staple of our cuisine.

WHEN SPANISH SAILORS FIRST ARRIVED on American shores in 1492, they caused one of the greatest revolutions in culinary history. Referred to as the Columbian Exchange, this instant cross-pollination of food coming both from and to Europe was perhaps the single most important influence on how we eat in New Mexico today. Such items as chile and chocolate from Central America were of great interest to the Spanish. A century later, these same items made the 1400-mile journey up the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro (the Royal Road of the Interior Lands), which connected Mexico City to just north of present day Santa Fe. Indeed, we owe New Mexico’s culinary traditions to the rich intermingling of foods and spices that occurred during the early colonial period.

In 1521, Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés instituted an aggressive agricultural policy, calling for every Spanish flotilla heading to Mexico to include fruit and vegetable seeds: apricot, peach, fig, quince, grapes and grapevine cuttings, garlic, onion, cabbage, and lettuce. The Spanish also import -

ed cattle, pigs, and chickens. These foods later traveled north with Juan de Oñate, who established the first colonial settlements on behalf of Spain in what is now New Mexico, and who happened to be married to Cortés’s granddaughter. The Oñate caravan carried 25 pounds of maize (American corn); 37 pounds of wheat; 846 goats; 198 oxen; 2,517 sheep; 383 rams; 799 full-grown cows, steers, and bulls; an unknown number of calves; and 53 hogs. Oñate made sure the caravan also had plenty of cooking supplies, carrying close to 25 pounds of olive oil, 56 pounds of sugar, and another 787 pounds of flour. In 1600, a mix of Old and New World food products were part of another caravan north: it contained 80 small boxes of Mexican chocolate.

Settlers at the time included Franciscan missionaries to minister to the Indians. They held Mass every day, and that required a ready supply of wine for the Holy Sacrament. Rather than voyage several months for supplies, the Mission, or Criolla, grapes reached New Mexican soil in 1629, nearly 150 years earlier than grapes arrived in what is now California. For

HHANDR.COM 29 NICOLASA CHAVEZ KITTY LEAKEN

nearly 300 years, these plump fruits were staples of New Mexican wine production. In fact, wine production in New Mexico, and parts of South America, was so prolific that growers in Andalucía, Spain, protested, and the Crown attempted to outlaw production in the Americas. But New Mexican production was never thwarted—and the area around present-day Socorro and south toward Las Cruces became one of the capitals of production until the end of the 19th century, when root rot all but killed the industry. It has since been rejuvenated, with more than 60 New Mexico wineries now producing close to a million gallons of wine a year.

Both chile and chocolate took root in New Mexican cuisine during this colonial period. Both were cultivated in Central America for thousands of years prior to the arrival of the Span-

Chile, chocolate, corn, beans, and squash are staples of the New Mexican cuisine and have been since the Spanish colonists arrived. Archaeologists have discovered ceremonial chocolate vessels at Chaco Canyon, dating to 900 CE.

ish, and Oñate and his settlers brought them north. During the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, in which the Pueblo Indians sought to expel the Spanish from their lands, the Puebloans decreed to get rid of not just the Spaniards, but all things Spanish. They planned to burn the chile seeds; however, chile had already become such a staple of the diet here, it claimed its righteous spot next to “the three sisters”: corn, beans, and squash. Today, chile remains integral to New Mexican cuisine—whether Spanish, Mexican, or Native American in origin.

THE FOOD OF THE GODS

There is evidence that chocolate came to New Mexico much earlier: The testing of broken pottery sherds found at Chaco Canyon, in northwestern New Mexico by University of

30 HHANDR.COM

BLAIR CLARK

NICOLASA CHAVEZ

KITTY LEAKEN

New Mexico anthropologist Patricia Crown, dates the use of cacao to as early as 900 CE. According to Crown’s study, chemical residues found on the iconic black-and-white pottery jar sherds reveal that the practice of drinking chocolate had spread at least as far north as Chaco Canyon, 400 years earlier than chocolate was thought to have reached what is now the United States. How that chocolate came to Chaco is something of a mystery: The closest cacao source may have been central Mexico, some 1,200 miles away. The evidence of both the vessels and the cacao residue, which were used in rituals in Mesoamerica, suggests that the Chaco people acquired the ingredients and the knowledge to perform similar rites at Chaco’s largest structure, Pueblo Bonito. Originally from Central America, the seeds of the cacao tree were first transformed into beverages some 3,000 years ago. Chocolate was used spiritually, medicinally, as monetary exchange, and for its nutritional value. Conquered Central American tribes paid “tribute” fees in cacao beans to the Aztecs.

Nearly 100 years after Oñate’s first voyage, Don Diego de Vargas re-colonized New Mexico after the Pueblo Revolt, bringing wedges of ground cacao for use in negotiations and as a gift to visiting dignitaries. His 1704 last will and testament specified that the chocolate in his personal possession was to be used to pay the friar who officiated at his funeral. According to notations in the will, chocolate in de Vargas’ personal supply weighed about 225 pounds and was stored in two large baskets. He also had sugar and chocolate-making accoutrements, including one case of ground cacao paste; two cases of sugar; 39 copper chocolate pots; and eight dozen molinillos (chocolate beaters or whisks), used to whip the drink until a froth formed on top, much like today’s latte.

By the 19th century, New Mexico was already famous for its regional cuisine. Visitors who traveled via the Santa Fe Trail were often greeted with a warm cup of the foaming chocolate drink. Ironically, it was the opening of the Santa Fe Trail and the introduction of food from the Eastern United States that eventually killed the daily ritual of drinking chocolate—coffee and tea were viewed as more refined than the thick, bitter beverage.

Today, those ancient foods are still a major part of New Mexico culinary tradition. Local fare is a mix of flavors for every palette, born from the fruits of the Columbian Exchange.

WHISPERS OF THE PAST

The pottery found at Pueblo Bonito, said to be ceremonial chocolate containers, are replicated today in the Hotel Chaco (Albuquerque) hallways. Lee and Flo Vallo from Acoma Pueblo, about 60 miles west of Albuquerque, make cylindrical clay pottery vessels with intricate black and white designs that are similar to those among the treasures found at Chaco Canyon. Working in the traditional pottery methods, the Vallos mine the clay from a sacred mountain, dry and prepare the clay, form the vessels using traditional methods and hand-paint them with a quill from a yucca plant using natural pigments. The Vallos frequently perform demonstrations at National Park sites and at the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center in Albuquerque.

HHANDR.COM 31

The fixtures at Hotel Chaco represent ancient Chacoan ceremonial pottery.

Lee and Flo Vallo, artisans from Acoma Pueblo.

MINH QUAN

32 HHANDR.COM

Randy Montoya’s jewelry has been featured at New Mexico Artisan Market at Hotel Albuquerque.

Jewelry by Hopi artisan Verma Nequate from Indian Market in Santa Fe.

Booth of Charlie Carrillo during the Spanish Market.

Shop the Markets

New Mexico’s markets showcase generations worth of cultural creations.

By Steve Larese

By Steve Larese

NEW MEXICO HAS BEEN AN ART CROSSROADS FOR MILLENNIA. The world-renowned skills of the region’s artists have been perfected through many lifetimes of work, with one generation passing techniques, experience, and spirit on to the next. Be it pottery, jewelry, weavings, flutes, drums, painting, carving, music, or sculpture, Native American and Spanish artists honor their ancestors and their cultures through their intricate creations.

Today, New Mexico’s large annual art markets draw tens of thousands of collectors from around the world to the state in search of one-of-a-kind art and opportunities to meet the artists. From traditional works made the way they have been for centuries, to contemporary art that pays homage to the past while incorporating new techniques and influences, New

Mexico’s artisan markets span eras and connect people from all walks of life.

PRESERVING NATIVE CULTURES

For every third weekend in August since 1922, Santa Fe Plaza has been the site of the world’s largest and most prestigious organized sale of Native American art. An estimated hundred thousand people peruse the booths of more than 1,100 Native artists from the United States and Canada whose work has been juried into this competitive market. New Mexico’s second largest event after the Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta, Indian Market brings tens of millions of dollars into the state. Many artists work all year creating pieces for Indian Market and make their year’s living during this single weekend.

In addition to artist booths, Santa Fe Indian Market has

HHANDR.COM 33

STEVE LARESE

MARKET DATES 2023

International Folk Art Market

July 6-July 9

(Santa Fe Railyard Park)

FolkArtMarket.org

Traditional Spanish Market & Contemporary Hispanic Market

July 29-July 30

(Santa Fe Plaza)

SpanishColonial.org

ContemporaryHispanicMarket.org

Santa Fe Indian Market

August 19-20

(Santa Fe Plaza)

Swaia.org

New Mexico Artisan Market

November 24-26

(Hotel Albuquerque at Old Town)

www.NMArtisanMarket.com

a Native American Clothing Contest in which children and adults model culturally representative clothing they have made.

Native American dance and music performances also take place throughout the weekend on the Plaza and its main stage, bringing a celebratory festival atmosphere to the market.

Native American art was originally utilitarian. Pottery was primarily created for cooking and food storage, jewelry for trading, and weaving for clothing, with artistic flourishes becoming more elaborate with each passing century. The arrival of American goods in the late 1800s via railroad and the increasing use of currency decreased the need for such items and put many indigenous art forms in jeopardy of being forgotten.

Concerned that these works of art and traditions would be lost, several people, including archeologist and first director of the Museum of New Mexico Edgar Lee Hewett and assistant director Kenneth Chapman, wanted to create an economic outlet for Native American artists. In 1922 they organized the Indian Fair as part of the Fiestas de Santa Fe to promote Native American art and create an incentive for the artisans to continue to create high quality work. Among the artists who benefited from the fair was famed San Ildefonso potter Maria Martinez, whose black-on-black pottery commands hundreds of thousands of dollars today. As the popularity of Native American art increased, more families rediscovered the art of their ancestors. The event grew to be so large that it was eventually separated from the Fies-

for Indian Arts (SWAIA).

PROMOTING TRADITIONAL SPANISH COLONIAL ART

With a similar mission as the Santa Fe Indian Market, the Traditional Spanish Market promotes colonial Spanish art. Also held on the Santa Fe Plaza, two hundred fifty juried New Mexico and Colorado artists demonstrate and sell their work that includes woodcarving, tinwork, weaving, straw appliqué, furniture making, ironwork, retablos, and other traditionally made Spanish art spanning utilitarian and religious needs.

The first Spanish Market was held in 1926 by a group of concerned Santa Feans including authors Mary Austin and Frank G. Applegate. This group would go on to establish the Spanish Colonial Arts Society in 1929 to preserve New Mexico’s mission churches and religious and colonial art and items. The group saved several rural adobe missions, including Chimayó’s famous Santuarío de Chimayó. The 2023 Traditional Spanish Market is July 29–30 on the Santa Fe Plaza.

MODERN INTERPRETATIONS OF HISPANIC ART

Coinciding with Traditional Spanish Market, Contemporary Hispanic Market showcases work by Hispanic artists whose

34 HHANDR.COM

tas de Santa Fe and today is a stand-alone event organized by the Southwest Association

New Mexico’s Large Annual Art Markets Draw Tens Of Thousands Of Collectors From Around The World

modern mediums include photography, painting, sculpture, printmaking, and other art forms. Celebrating its thirtyseventh year in July, the Contemporary Hispanic Market was created by a group of artists to complement Traditional Spanish Market by providing exposure for Hispanic artists whose work is not necessarily tied to the colonial creations of the 1600s and 1700s. The market is held on Lincoln Avenue just off the Santa Fe Plaza.

THE WORLD’S LARGEST FOLK ART MARKET

Hosted by the International Folk Art Museum since 2004, this July event is the largest folk art market in the world. More than 150 artists from sixty countries visit Santa Fe to sell their unique art and cultural crafts on Museum Hill. These master artists demonstrate their skill in weaving, pottery, beading, painting, carving, and all other manners of traditional art from around the world.

NEWEST ARTISAN MARKET IN NEW MEXICO

Heritage Hotels & Resorts—a hospitality organization dedicated to the preservation and advancement of the creative culture that has shaped the identity of New Mexico for centuries—introduced an exclusive artisan market created for New Mexican artists, trade and craftsmen in the Fall of 2018. The New Mexico Artisan Market promotes artisans while growing the state’s creative economy. The market is held Thanksgiving weekend at Hotel Albuquerque at Old Town––a landmark resort in Old Town Albuquerque, and a focal point for the artisan community of New Mexico. This three-day event features a select roster of curated vendors, many of whom are recognized internationally as experts in their craft. Prominent influencers from New Mexico’s artisan community have been charged with carefully selecting only the most authentic vendors to showcase their goods, and share with the world their dedication to New Mexico’s artistic heritage. Visit NMArtisanMarket. com for more information.

TIPS ON BUYING AUTHENTIC ART

Thanks to efforts of such groups as SWAIA, fake pottery and jewelry sold as Native American-made has drastically decreased in recent years. The skill, patience, talent, and time that go into a true piece of Pueblo pottery, Navajo weaving, or silver and turquoise jewelry are reflected in the price of the art. Some pots that are sold are molded in a factory, then painted by a skilled Pueblo artist. While these are still valid works of art, their price should be much less than a handmade piece. The dealer should also state up front when pieces are not hand coiled. Similarly, the artists should make clear that weavings and jewelry are handmade and whether turquoise stones are natural or immitation. It is not customary to negotiate the price of artwork unless the artist offers first. Artists know the time and skill that goes into the creation of their work, and don’t often want to part with less than they are asking. If the price of a piece of art is drastically reduced, it may not be handmade or authentic.

HHANDR.COM 35

Artisans from all over the world are featured at the International Folk Art Market.

THIS PHOTO & OPPOSITE PAGE, TOURISM SANTA FE

W EAVING HISTO R Y

A legendary trading post honors the past, present, and future of an ancient art.

By Susannah Abbey

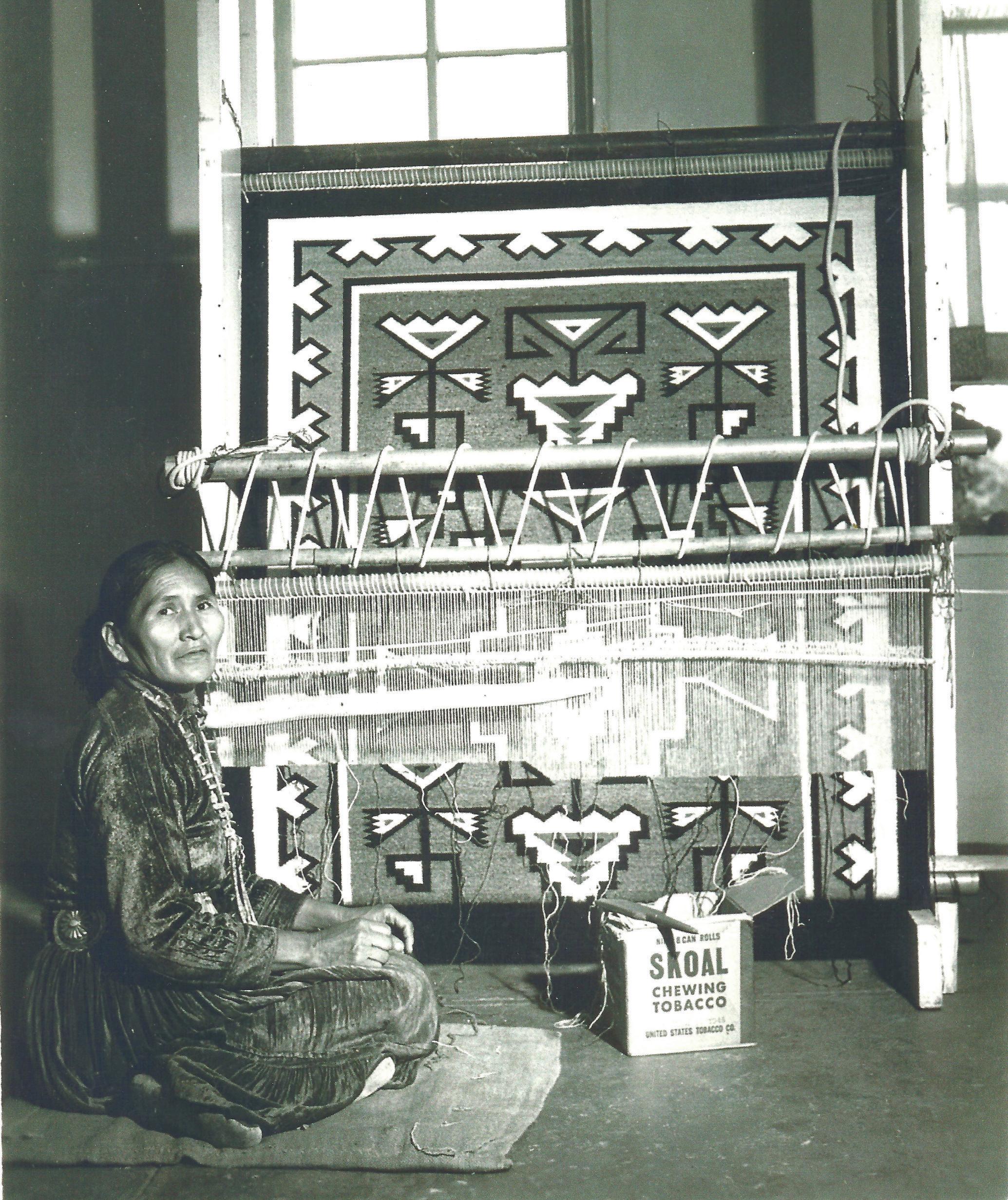

TOADLENA SITS AT THE FAR WESTERN EDGE OF NEW MEXICO, on the Navajo Reservation border with Arizona. To get there from Interstate 40 you cross a sequence of landscapes: from the red sandstone bluffs of Gallup, through dry scrubland along New Mexico State Road 666/491. Turn off the highway and ascend through open range where horses nibble sparse grass, past the Mormon church, the Navajo Fish Hatchery (public welcome) to the lush shade of a cottonwood grove. A spring trickles from the base of the Chuska Mountains and flows through the Tó’Háálí Community School grounds. Here the historic Toadlena Trading Post and Weaving Museum, one of the last remaining posts on the reservation, sells handmade textiles to dealers and individual buyers from all over the world. Fifteen miles northeast, Bennet Peak and Ford Butte rise from the valley floor. These are the two grey hills for which the regional weaving style was named, in a region with a tradition of producing the highest quality Navajo textiles in the land. The trading post guards that tradition.

In 1909, the same year that the Bureau of Indian Affairs opened a boarding school at Toadlena, brothers Merit and Bob Smith built a one-room adobe trading post across the road. A few years later the brothers sold the lease to George Bloomfield, who

more than doubled the size of the building and clad the adobe walls in quarry stone. It changed hands a few more times before finally ending up, in the late 1950s, under the management of R.B. Foutz, who also ran a store in Shiprock, New Mexico.

In 1997, Foutz talked Mark Winter into taking over the business, which was not a hard sell. Foutz had given up on Toadlena—it had been closed almost a year when Winter fell in love with the place and took over the lease (the post itself is owned by the Navajo Nation—the traders are simply leaseholders). Winter subsidizes post operations through antique rug sales.

“We never intended to make money...[but] to support the weaving tradition,” says Winter. “We support between 150 and 175 weavers within 12 miles. ... Our local region [is] still the most active weaving community left on the reservation and a lot of that is because of our efforts.”

Mark Winter has always been a collector. Growing up in San Bernardino, California, he collected bugs, stamps, comic books, and slot cars. Later it was Native American jewelry, bought at pawn shops and shows across the southwest and sold to wealthy musicians and actors in Los Angeles. One day a stranger offered him seven antique blankets. One, Winter recalls, was “a beautiful storm pattern.” The encounter, like any fairytale meeting with a magical stranger, changed his life. He began buying and selling

HHANDR.COM 37

OPPOSITE: A rug by master weaver Daisy Taugelchee, ca. 1948, 43”x70”

blankets and rugs and continues to do so today.

Winter soon developed an interest in the people behind the art. The traders of the ninteenth and early twentieth centuries didn’t see the need to give the weavers credit for their weavings; it simply wasn’t important for marketing purposes. Winter was curious about the artists: He began taking antique rugs to the reservation in the hopes of collecting background information about them. He brought one rug to renowned weaver Clara Sherman who was able to produce a photo of herself standing next to that very rug. Winter knew this was an important revelation; it would establish clear connections between the weavers and their work and help him identify the early and mid-century rugs he had. He began asking for and taking photographs. It was “a way for the weavers to reflect on their works,” he recalls. “They would scan a rug with their eyes and sometimes remember doing a specific thing in the weaving and associate it with a time in their lives.” Many of the weavers of those antiques were gone, but Winter interviewed everyone he could, finding out who was related to whom, who wove and who didn’t, and how the clans and families fit together. The result was a massive genealogy project that went into his 2011 book “The Master Weavers.”

SHEEP AND COLOR

Navajo country is sheep country, and about 6000 roam the desert plains north of Gallup today. It hasn’t always been this way. The Spanish conquistadors introduced the Churro, famed for its hardiness, long fibers, and soft fleece, to the Southwest some 400 years ago. But in the 1930s sheep all but disappeared from this area during a government mandated slaughter to reduce overgrazing in the arid desert landscape. Today, there has been a concerted effort by the Navajo and others to bring sheep, and the sustenance they provide, back to Navajo land.

On the large flagstone patio behind the trading post, where Winter and his wife, Linda, hold demonstrations and museum openings, weavers Irene Bennalley and Victoria John are busy restoring and mounting antique rugs for an upcoming show in Santa Fe. Bennalley is the Regional Shepherd Coordinator and Navajo Churro Sheep Association board member. She keeps a large flock which she selectively breeds for the colors of their wool.

Indeed, one of the main distinctions between the Two Grey

Hills weavings and others is the use of undyed wool. “Right now, I’m focused on nonfading black and brown,” Bennalley says. She explains that sheep’s wool lightens over time. “You’ve got to go to different breeders but you can’t really know until they age for two years. If they stay the same as their birth color you keep that ram. ... I keep the best ewes and get rid of the rest.”

Bennally is skeptical of the legendary Churro sheep. “What I was told when I first got into the Churro sheep—‘oh they’ve got a lot of sheen, they’ve got softness and luster.’ After working with them for a few seasons, I went ‘where the hell is the luster?’ When I was shearing my hands got cracked and dry.” Bennally prefers Navajo sheep, a hybrid of Merino, Churro, and Rambouillet. Recently some sheep breeders have attempted to bring back the Churros, but Winter maintains that the breeding program hasn’t resulted in the soft wool of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, which he attributes to “a magical moment in time.”

The Two Grey Hills style developed in the early twentieth century when traders convinced weavers to adopt Persian-type designs in keeping with Victorian tastes. The style features a central diamond pattern on a Grey background with a black border. Unlike those in other regions, weavers here eschew reds, preferring the natural black, white, grey, and brown hues of the sheep themselves. They card shades together to create sub-tones and because they spin the wool as fine as thread, their work tends to be tight and crisp. The number of wefts, or horizontal threads, is another distinguishing feature of Two Grey Hills. Where typical rugs average 30 wefts per inch, Two Grey Hills average 45. During her life the celebrated twentieth century weaver Daisy Taugelchee made tapestries of 115 wefts per inch.

MAINTAINING TRADITION

In the museum, Winter points out different rugs: “That’s Mrs. Police Boy,” he says. “She was born in Bosque Redondo in 1865 and lived 100 years.” We move to the next one. “And this is her daughter, Police Girl.” He points to a large, old rug. Propped at its base is a faded photograph of a young woman standing by her hogan with that same rug hanging behind her. “This was the very first rug whose weaver I was able to identify,” he says.

38 HHANDR.COM

Toadlena Trading Post in winter

TOADLENA TRADING POST

Linda Larouche was working in New York City’s garment industry and had started to collect East Coast Native American arts. She had heard about the art shows in New Mexico and in 2003 decided to see one for herself. She never went back to New York. At first, she helped Winter with antique sales in Santa Fe. Then she began accompanying him to Toadlena to help in the store.

“When I came out, I said ‘oh my God, I love this place and I want to be here.’” In 2011 Linda and Mark married at the trading

post, attended by “a thousand” friends, family, and members of the Two Grey Hills community.

“People ask me if I’m bored out here. I’m never bored because it’s so busy.” Linda describes a typical day—some people coming in to sell rugs, others to buy groceries (the store offers a selection of nonperishable foods, soft drinks, and cigarettes), sightseers and, of course, rug buyers. “If a couple walks through the door thinking they’re going to look at a few blankets and leave, three

HHANDR.COM 39

TOADLENA TRADING POST

hours later their plans have changed.” They receive visitors from the Heard Museum in Phoenix and the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian in Santa Fe, other weaving groups, and once—possibly because collectors like collections—a Model A car club. People come to admire the rugs, farming equipment, and other antiques that fill the store. Toadlena used to be on the mystery writer Tony Hillerman tourist map; two of Hillerman’s fictional characters, detectives Joe Leaphorn and Jim Chee, live in Toadlena and Two Grey Hills. Although the map is no longer published, Hillerman fans still drop by to look around.

Thelma Brown wasn’t raised on the reservation—her family had relocated from the Two Grey Hills area to Uravan, Colorado, a now-abandoned uranium mining town where her father worked and where children would get a good education. But in 1984, after the uranium industry failed, the family returned

to Toadlena. Brown says that was when she wove her first rug.

“My mom said, ‘you’re gonna weave’ and set up a rug for me. Most people start out with small rugs. My mom set up one that was 44x66 inches. It was a big rug.

“I used to think it was corny when the weavers would say [of their designs] ‘oh, it’s all in my head.’ I used to draw them out, I admit it.” She’s since learned to do the same. “I would walk back and forth in front of [the loom] and pretty soon I started saying ‘I know what I’m going to do’ ... things started falling into place.”

“Thelma comes from a great weaving family. Her great aunt was Clara Sherman, and her grandmother was Clara Sherman’s older sister,” says Winter. “It’s really magical that what Thelma’s great-great-grandmother did I’ll sell and it’ll help support Thelma and her daughter.”

40 HHANDR.COM

An installation view from The Weaving Museum’s 2020 exhibit, Eye on the Storm, Storm Pattern rugs from 1910 and 1940.

“And her daughter Jamie, who’s seven, is starting to weave. She can card wool,” Linda says.

“It’s pretty typical if they’re going to learn they start around seven or eight,” says Brown. “My daughter keeps seeing spiders—when she says ‘mommy, there’s a spider’ I say ‘they’re trying to tell you to weave.’” She’s referring to the Navajo deity, Spider Woman, who, in mythical stories, teaches weaving and agricultural practices to the people. Jamie now does carding demonstrations at the store like her mother and grandmother.

Brown enjoys working at the trading post, learning more about rug designs and being at the center of what has become a de facto community center. Locals come in to buy a soda or a bag of chips, stay to chat and pretty soon Brown knows who is looking for whom and where they can be found, about who has seen a bear and where (black bears are active in the Chuskas), and other important news, including reports of “bigfoot sightings.”

GIVING BACK

In 22 years, the Winters have bought and sold about 7800 rugs. Recently Jim Long, CEO of Heritage Hotels & Resorts, commis-

sioned 130 of them for Hotel Chaco guestrooms. In addition to supporting the artists, Winter found he had more to offer. It began during the recent drought when a master weaver in her 90s brought in a rug. Winter describes her standing silently in a corner, waiting for him to finish what he was doing.

“She finally asked me ‘are you going to buy my rug?’ and I said ‘yes, I just need to finish up here’ and she looked relieved and said ‘oh good, now we can eat.’” She explained that all their money was going to feed the sheep. The family hadn’t been able to afford food for a couple of days.

That was the start of Blessingway, a nonprofit organization that helps the community of Two Grey Hills. Blessingway takes donations from people all over the country to pay for necessities from sheep feed to school supplies. It might be one of the Winters’ enduring legacies.

“When this post closes this whole era is gone,” Mark says. From hundreds of trading posts in the early twentieth century, only a dozen or so remain.

“We have no plans to retire,” Linda says. “We’re here as long as they’ll have us.”

HHANDR.COM 41

Todalena commissioned rugs are featured prominently in Hotel Chaco’s guest rooms.

of the

R ediscovering A ncient

ON THE DESOLATE COLORADO PLATEAU of northwestern New Mexico, Fajada Butte exudes a stately presence straight out of a John Ford Western. High on its shoulder, three sandstone slabs bearing the handiwork of an ancestral Puebloan have quietly marked the passage of time for a millennium since this remote place may have formed the center of an ancient world. Each day at noon, sunlight shines through the slabs onto the cliff face and, precisely at noon on the summer solstice, bisects the larger of the two spiral petroglyphs carved there as two shafts bracket the spiral’s outer edges. At the spring and autumn equinoxes, a shaft of light pierces the smaller of the two spirals.

A vast complex of ruins on a remote plain holds the origins of modern Pueblo society.

the C enter W orld

By Ashley M. Biggers

FAJADA BUTTE ACTUALLY SERVES AS AN ENTRANCE GATE TO A COMPLEX OF 16 MASONRY STRUCTURES IN THE ARID CANYON BELOW.

The ancient architecture protected within Chaco Culture National Historical Park represents the culmination of a civilization as enduring as that of Stonehenge in England or Teotihuacan in Mexico. The buildings that today share the same frayed edges and timeworn hues of Fajada Butte once housed some 2,000 residents who built, farmed, and prayed here.

The multistory great houses they constructed between 850 and 1250 A.D. Archeologists estimate that the Ancestral Puebloans were among the most populous groups in North America until the 19th century. Yet the builders drifted away from their economically complex society, leaving behind as many questions as answers. They didn’t disappear, but evolved into the people of the 19 pueblos of New Mexico as well as the Hopi, who reside in Arizona. At ceremonial occasions and at the solstices and equinoxes, Pueblo people still return to Chaco as to an ancestral homeland.

Chaco was made into a national monument in 1907, and a national historical park with enlarged boundaries in 1980. In 1987, Chaco Culture National Historical Park was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site, joining other historical and natural marvels worldwide from Machu Picchu to the Great Barrier Reef. It has been speculated that Chaco’s astronomical alignments and pictographs reflect its residents’ efforts to connect the heavenly order with a tumultuous world in which they were vulnerable to extremes of heat and cold, drought and monsoon in this isolated landscape. As Phillip Tuwaletstiwa writes in The Mystery of Chaco Canyon, “If there was a way to transfer the orderly nature of the cosmos down onto what seems to be chaos

that exists here, then you begin to then integrate at this place both heaven and earth. And this would be ... the center place.”

The significant architecture of Chaco Canyon begins “downtown,” home to the great houses Chetro Ketl, Casa Rinconada, and Pueblo Bonito, accessible along a nine-mile scenic drive through the park. Pueblo Bonito is one of the canyon’s most beautiful as well as the grandest. The massive D-shaped structure once towered four to five stories, with a honeycomb of some 650 rooms cascading from the central plaza toward a cliff face at a scale that rivals Rome’s Coliseum; 33 kivas (ceremonial chambers) completed the structure. Common practice of the time was to add rooms to existing structures as families expanded, but these buildings were planned at the start — the original master-planned community.

Pueblo Bonito feels like a labyrinth, with one antechamber connecting to the next through a series of low doorways. Builders carefully considered the placement of the several-foot-thick walls, allowing sunlight to pass through unique corner and T-shaped doorways. Sight lines to surrounding buildings would have allowed the residents to communicate with each other from afar.

Casa Rinconada also hints at Chaco Canyon’s archaeo-astronomy. The structure is aligned precisely to celestial north. At the summer solstice, an opening on the northeastern wall casts a

44 HHANDR.COM

ROBERT RECK

Top right, Photographer Robert Reck captured the light reflecting on Pueblo Bonito. Right: The doors align along the path of the sun. Center: Kin Kletso, Navajo for “yellow house,” featured 65 rooms and five kivas. Far right, it is one of Chaco’s grandest structures, and once consisted of 650 rooms.

ROBERT RECK WILSILVER77 / 123RF STOCK PHOTO ALBERTO LOYO / 123RF STOCK PHOTO

beam onto an opposing kiva wall, which at sunrise hovers precisely over a niche, suggesting a sophisticated attunement to the seasons. This astronomical awareness can be observed throughout the canyon. For example, a pictograph near Penasco Blanco, one of the more remote structures, is thought to represent a supernova from the year 1054; it is depicted next to a crescent moon and a human handprint, asserting the human presence in the cosmos.

In its heyday, Chaco formed a center of civilization in multiple ways. Archeologists have traced the Chacoan organizational system far beyond the park boundaries, to related sites at Aztec Ruins National Monument in New Mexico, and to some 150 to 200 sites stretching across 20,000 to 40,000 square miles of the American Southwest. Roads not unlike the wide boulevards that radiate from the Capitol in Washington, D.C., cut swaths across the ancient landscape, connecting Chaco to the broader world. The Chacoans had no carts or beasts of burden, and few signs of trade have been found on these precisely straight, 35-foot-wide

“roads,” so their purpose remains a mystery.

The Puebloans who farmed in the high-desert environment, with its long winters, short growing season, and scant rainfall, subsisted on the “Three Sisters” of the Puebloan diet — corn, beans, and squash — hunting for rabbit and occasional large game, such as deer. Their resources grew from commerce. They amassed turquoise beads and crafted immense stores of blackon-white and red-ware pottery to trade with visitors from as far as Mesoamerica. A mysterious cache of 181 cylindrical vessels found in just a few rooms turned out to bear traces of cacao, and to mimic Mayan cacao-drinking vessels from 1,200 miles south, where the plant naturally grows. Archeologists have also unearthed copper bells, conch-shell horns, and macaw feathers at Chaco, further indications of the canyon’s role as a continental gathering place.

Some archaeologists theorize that Chaco was not designed to house large populations, but that its great houses overflowed seasonally with pilgrims traveling to this ceremonial center with the

46 HHANDR.COM

ROBERT RECK

Chaco Canyon is part of the Dark Sky Park initiative. Natural darkness and few artificial lights mean superior stargazing. The park offers star parties twice a year.

solar and lunar cycles. Rituals tied to planting, harvests, and rain would have taken place in the kivas (ceremonial chambers, usually round and underground), a prominent feature in Chaco’s architecture. The kivas would have had benches along the walls and in the center a sipapu — a covered hole on the floor that symbolizes the original place from which people emerged into the world.

Only its residents know whether visitors overtaxed the canyon’s fragile environment or whether drought struck, but the builders abandoned Chaco after a few centuries of vigorous development. The canyon went on to house other residents, such as Navajo settlements traced to the 1500s. By the late 1800s, it was archeologists who most frequented Chaco Canyon. The first major excavation began in 1896 with Richard Wetherill. Many of the artifacts he discovered were shipped to the American Museum of Natural History, where they remain.

Visitors today tour the canyon via its scenic drive, and hiking routes such as the Pueblo Alto Trail, which climbs a cliff face for spectacular views overlooking Pueblo Bonito and Chetro Ketl. The longest trail, Peñasco Blanco, includes a spur to numerous Pueblo and Navajo rock carvings and pictographs. Overnight camping at the park, particularly at the solstices and equinoxes, offers glimpses into the canyon’s subtle complexities.

Stargazing is world-renowned at Chaco Culture National Historical Park, recognized as an International Dark Sky Park, one of just a handful in the United States. The park reduces artificial lighting, which makes for prime star viewing. Throughout the year, rangers and volunteers from the Albuquerque Astronomical Society host programs to help visitors view nebula, planets, and other phenomena at the Chaco Observatory. Standing beneath the vast expanse of the Milky Way as it stretches across the inky heavens, you may feel at once grounded and diminutive, intrigued and awestruck — just like the Chacoans who once dwelled and worshipped here.

HERITAGE INSPIRATIONS, the partner tour company of Heritage Hotels & Resorts, leads day trips and overnight glamping tours to Chaco Culture National Historical Park departing from Hotel Chaco in Albuquerque. HeritageInspirations.com

Echoes of Chaco in Design

Modern-day descendants commissioned for hotel’s interior

The road to Chaco Canyon began in the 1990s for Heritage Hotels & Resorts designer Kris Lajeskie. She had moved to Santa Fe to pursue an interest in Indigenous cultures, and visited the park’s Puebloan great houses scattered across a remote wash in the San Juan Basin. Besides the architecture, building techniques, and art of a culture that inhabited the region from 800 to 1250, something about the place struck a deeper chord. “When I went there for the first time, I had this connection,” the New Jersey native says. “I felt part of it. It was a home center for me.”

Long before she worked on Hotel St. Francis and designed the interior for Hotel Chimayó in Santa Fe, Lajeskie had ventured into the archives of the American Museum of Natural History and seen an artifact pulled from an 1800s dig at Chaco Canyon — a jet-black frog with turquoise eyes — that would be incorporated into Hotel Chaco’s iconic logo.

HHANDR.COM 47

Hot days, cool nights, and family traditions give this legendary New Mexican pepper its unmistakable character.

CHIMAYÓ’S CHILE CULTURE

By Deborah madison

DRIVING NORTHEAST FROM SANTA FE TO CHIMAYÓ IN NORTHERN NEW MEXICO, you pass through grass-covered badlands scarred with erosion, scattered with red rocks formed into fantastic shapes, softened slightly by rabbitbrush and piñon and juniper trees. For a long time, there isn’t a dwelling in sight. The tail end of the Rockies slopes up to the east. To the west, across the Rio Grande, rising above blue mesas, are the Jemez Mountains.

Though Chimayó, which takes its name from the Tewa Indian word for flaking red stone, is only twenty-six miles from Santa Fe, it completely lacks that town’s stylishness and cosmopolitan flair. There is a quiet sweetness and calm about the place, enhanced by the broad shallow river that flows through it, keeping the landscape soft and green in the midst of Chimayó’s harsh surroundings.

Evidence of a way of life that has endured for generations can be seen in the old apple orchards and gardens, and in the small fields of chiles for which Chimayó is renowned. In autumn, the scents of apples and of piñon smoke, from fires used to roast the chiles, saturate the air.

Unlike larger, mass-produced chiles grown in other parts of the state—whose conformity makes them perfect in the way that iceberg lettuce is perfect—Chimayó chiles are unpredictable. A single plant might produce some chiles as long as six or seven inches and many more that are shorter; a few might be straightish and skinny, but most will be bent oddly into curlicues. Their irregularity seems to reflect the landscape, with its winding roads and dry-rock badlands juxtaposed with lush valleys and tiny fields.