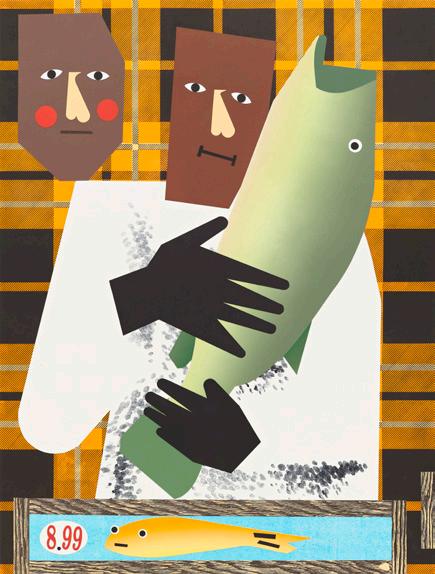

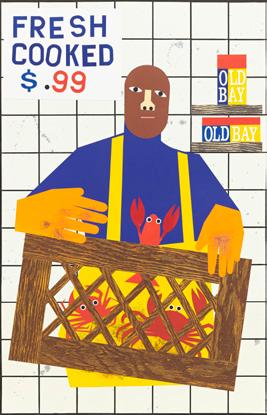

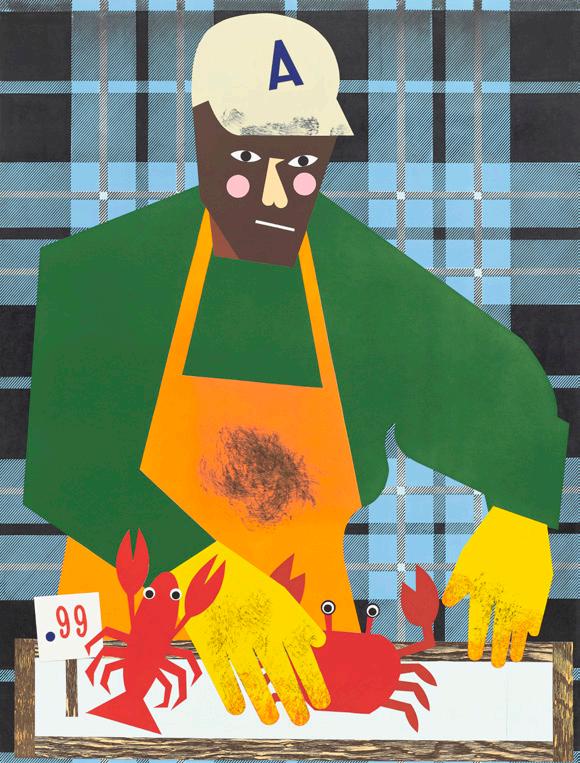

Cover: Captain F.M., 2022. Collage on panel. © Nina Chanel Abney. Photo courtesy of the artist and Pace Prints.

Below: Installation view of exterior mural, 2022. Inkjet print on vinyl. Photo: Jueqian Fang.

Cover: Captain F.M., 2022. Collage on panel. © Nina Chanel Abney. Photo courtesy of the artist and Pace Prints.

Below: Installation view of exterior mural, 2022. Inkjet print on vinyl. Photo: Jueqian Fang.

Cover: Captain F.M., 2022. Collage on panel. © Nina Chanel Abney. Photo courtesy of the artist and Pace Prints.

Below: Installation view of exterior mural, 2022. Inkjet print on vinyl. Photo: Jueqian Fang.

Cover: Captain F.M., 2022. Collage on panel. © Nina Chanel Abney. Photo courtesy of the artist and Pace Prints.

Below: Installation view of exterior mural, 2022. Inkjet print on vinyl. Photo: Jueqian Fang.

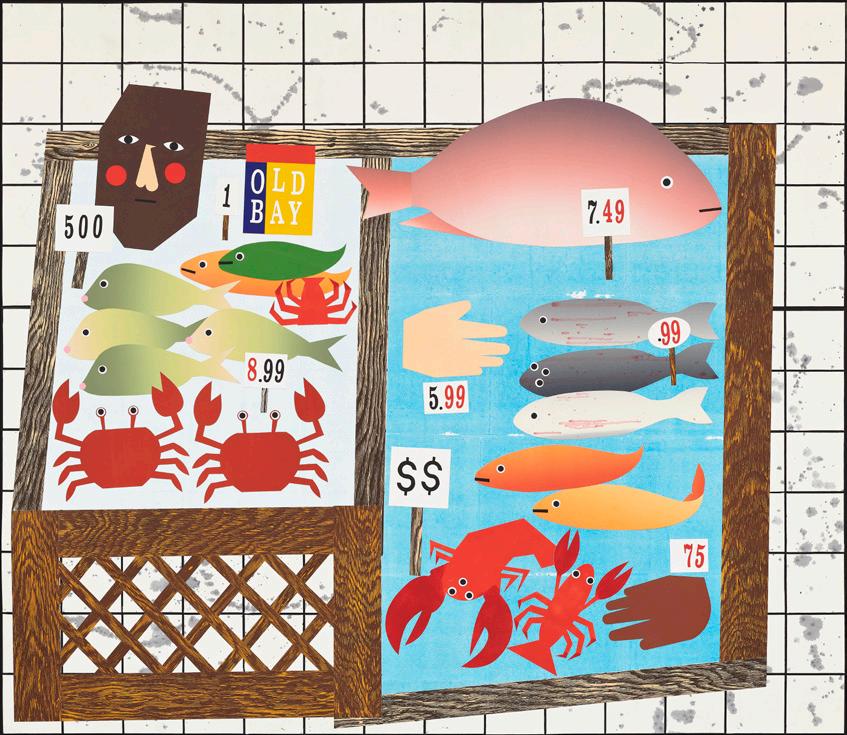

Working across painting, printmaking, and large-scale murals, Nina Chanel Abney (b. 1982, Chicago) creates dynamic compositions that engage potent themes including race and gender, power and desire. Vibrant and animated with geometric symbols and shapes, Abney’s work has a disarming visual allure that reveals a matrix of social and cultural currents affecting contemporary life. Abney’s recent collages and new paintings in the exhibition Fishing Was His Life center the rich culture and commerce of fishing within the African American community. The work celebrates a long legacy of identity and self-determination intimately entangled with coastal fisheries while also conjuring the structural inequities that threaten Black life and livelihoods within the industry.

Abney addresses such racial inequities in her 2022 triptych Black People (BP), which references the catastrophic 2010 BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico that disproportionately affected communities of color in the region. Suffused with tender humanity, the work evokes the conjoined and enduring violence of environmental and racial dispossession in the United States and the way Black life persists despite forces that attempt to foreclose it.

The work in Fishing Was His Life emerged from Abney’s encounter with photographs made by pioneering African American photographer Gordon Parks while on assignment for the Office of War Information as part of a government project to convey American fortitude during World War II. Between 1943 and 1944, Parks documented the fishing industry along the Atlantic coast through images of white fishing crews in and around Gloucester, Massachusetts and the Fulton Fish Market in New York City. Abney’s work is a response to those whose labor and resilience is missing from this documentation, and the history and culture obscured in the process. The resulting artworks, many monumental in scale, address the gap Abney identified in the visual record, creating images that honor African American inheritance within the fishing industry.

Abney made the resulting collage artworks in collaboration with master printers at Pace Prints using an array of techniques that generate rich surface textures. That suggestive tactility complements the representation of hands within Abney’s collages, a recurring motif across the exhibition that evokes the embodied labor and intimacy of both fishing and art making.

Abney’s exhibition extends outdoors, with an exterior mural on the façade of the museum. That mural is a companion to two collages in the galleries that provocatively stage the seafood market, evoking relationships between racialized bodies, commodities, and consumption.

Remember when we all thought it was going to be okay?

I asked a friend and fellow writer this question recently, as we took in the ongoing changes to a rapidly gentrifying street in the Uptown section of New Orleans. We laughed the kind of laugh that ended in a deep sigh. At that moment we were standing outside an art gallery owned by a Black New Orleanian, but we were aware now that at any moment things could change.

The 2010 Deepwater Horizon explosion, commonly referred to as the BP oil spill, killed eleven workers and shattered whatever remaining illusions we had that New Orleans or southern Louisiana at large would ever be the same. In the intervening years between Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and the blast, there had been a quiet sense of hope in some who had managed to return to southern Louisiana. The explosion, however, resulted in the largest marine oil spill in the history of the petroleum industry. I’ve often thought about the way gentrification in New Orleans accelerated in the years that followed. The abrupt changes to our natural landscape occurring parallel with our disappearing Black neighborhoods now filled with white newcomers to the city.

Throughout my early adulthood I worked, like many people in New Orleans, in various aspects of the hospitality and tourism economy. The year of the BP spill, I found myself employed in the sales office of one of the older, family-owned and operated restaurants in the French Quarter. The buildings that house these restaurants are afflicted with beauty and history. Tourists from all over the world come to eat in lush center courtyards, once home to the colonial governors of Louisiana. Men who drained the swamps and marshes that surrounded their new possession to impose their idea of what a city should be atop the complex network of Native nations already trading at the mouth of the Mississippi. Many times, on smoke breaks, I would read the restaurant’s history of itself. Praise for those who had created petit Paris and absent any mention of the enslaved men and women, who had also been resident on its grounds, or who had constructed the building itself, and its intricate ironwork. Nor any mention of these enslaved Africans and Native peoples’ direct culinary influence on most of the dishes it served. Restaurants like these are complex microcosms of the race, gender, and class dynamics that shaped the framework of American society. Both their owners and often their employees were multi-generational. I learned later from other people who had worked at the restaurant long term that there had never been any Black person hired to work in their sales office before I was hired. The post-Katrina landscape was forcing adjustments on even those at the top of New Orleans food chain.

The office handled larger bookings for tour groups, corporations, and private events. The aftermath of the spill was a time of panic. The same tourists and conventions that were just returning to the city were now canceling their parties daily. I was new to the network of bus operators, tour guides, transportation companies, and convention planners that all fed into and off of what constituted our city’s only

industry. Once functioning as the sleeping quarters for a residential home, the third-floor office space itself was divided into multiple boxy rooms with no hallway. Its walls were densely decorated with framed news clippings, religious paintings of saints, and historic photographs of the restaurant. The cornerstone of which was the floor-to-ceiling illustrated map-drawing of Louisiana and every functioning plantation in 1858.

One morning soon after the spill I came into the space I shared with the owner’s daughter and one other sales agent, who had worked there over two decades. The owner’s daughter was not in yet, but the other agent was, and she was crying.

“They’ll be fine,” she said, waving her hand around the room. “The oysters,” she said, “will never be the same.”

Next door to the restaurant was a coffee shop that also had a courtyard. It was my closest getaway from the office. Before going into work, I would sit there and read, wondering about who had sat in its space over time. Those are thoughts you can’t get away from in New Orleans. The coffee shop was also inevitably jammed with tourists and its own racist memorabilia. Among the calcified pralines that only out of towners would buy were also the postcards featuring Ol’ Man River Cane Syrup, ShoNuff Molasses, Old Mammy’s Yams. Advertisements with Black men’s faces at the center of sunflowers. Back at the office, we were getting emails from our city’s tourism board on how to answer tourists and locals' concerned questions about seafood. Among the more outrageous scripted responses: it's probably safer now than ever!

Triptychs were often traditionally created as altarpieces. I see Nina Chanel Abney’s Black People (BP), in one sense, as such. There is a steadfastness evoked by the figures, as they do as they have always done. An alternative iconography to the kind that surrounded me all those years ago in that stuffy French Quarter office, whose saving grace was its third-story view of the Mississippi River. The waters just about an hour south of New Orleans were at one time home to some of the richest oyster beds in the world. Black people lived and worked on this water for centuries both before and after emancipation. A life on the water afforded a modicum of freedom in a country determined to deprive Black people of its most basic attributes. Here the water was the ultimate provider. Knowledge of its patterns were the blueprint for a life outside the typical confines of white society. Communities could eat and live unto themselves and still have a product to sell to the

restaurants in New Orleans and other parts of the country and world. Always those with the biggest boats and leases made the most. But the natural abundance of the water allowed for sustenance.

Following the eighty-seven day BP spill, dispersants were used to bring the oil to the surface. Freshwater from the Mississippi River was then redirected into oil-covered waterways killing many of the oyster beds that depend on the brackish mixture of salt and fresh. Redirections of freshwater in the years since, aimed at fighting coastal erosion, have also severely impacted the Black fisherman, oysterman, and shrimpers in Plaquemine Parish. Years of discriminatory policies around leasing, profits, and post-disaster recovery processes leave many wary of what’s to come. Since the spill, oyster production has decreased by as much as half. However, despite the incessant losses on the water, Black people in southern Louisiana remain its caretakers. As the economics and logistics of climate change push many out of the fishing waters, some still remain—determined to see whatever becomes of their way of life through to the end. While the water rushes in, cultivation and practice remain sacred, and must continue, sometimes even as we lose the very land we stand on and those to leave it to.

Anthony, 2022

Collage on panel

Paper: 46 3/4 x 35 1/2 in. (118.74 x 90.17 cm); 48

7/16 x 36 7/16 x 1 3/8 in. (92.53 x 121.92 x 3.5 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and Pace Prints.

Black People (BP), 2022

Triptych collage on panel

Paper: 72 x 84 in., each (182.88 x 213.36 cm, each);

frame: 73 1/4 x 85 1/4 x 1 3/8 in., each

(186.05 x 216.53 x 3.5 cm, each)

Courtesy of the artist and Pace Prints.

#Bruthas Who #fish, 2022

Collage on panel

Paper: 67 1/2 x 78 1/4 in. (171.45 x 198.12);

frame: 68 3/8 x 79 1/2 x 1 3/8 in.

(172.72 x 200.66 x 2.54 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and Pace Prints.

Captain F.M., 2022

Collage on panel

Paper: 60 x 60 in. (152.4 x 152.4 cm);

frame: 61 1/4 x 61 1/4 x 1 3/8 in.

(155.57 x 155.75 x 2.54 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and Pace Prints.

Fish Head, 2022

Collage on panel

Paper: 35 1/4 x 47 1/8 in. (89.53 x 119.7 cm);

frame: 36 7/16 x 48 7/16 x 1 3/8 in.

(92.55 x 123.03 x 3.5 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and Pace Prints.

Fish Tales, 2022

Collage on panel

Paper: 46 3/4 x 35 1/2 in. (118.74 x 90.17 cm);

frame: 48 x 36 11/16 x 1 3/8 in.

(121.92 x 93.16 x 3.5 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and Pace Prints.

Johnny X, 2022

Collage on panel

Paper: 78 x 66 3/4 in (198.12 x 167.64);

frame: 79 1/4 x 68 x 1 3/8 in.

(200.66 x 172.72 x 2.54 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and Pace Prints.

My Old Bae, 2022

Collage on panel

Paper: 56 1/2 x 36 ¼ in. (143.5 x 92.07 cm);

frame 57 3/4 x 37 1/2 x 1 3/8 in.

(146.68 x 95.25 x 3.5 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and Pace Prints.

Sea & Seize, 2022

Collage on panel

Paper: 62 1/8 x 71 1/2 in. (157.8 x 181.61 cm);

frame: 63 3/8 x 72 3/4 x 1 3/8 in. (160.96 x 184.78 x 2.54 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and Pace Prints.

Sistas Who Fish (1 Fish), 2022

Acrylic and spray paint on canvas

60 x 60 in. (23.62 x 23.62 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Sistas Who Fish (2 Fish), 2022

Acrylic and spray paint on canvas

60 x 60 in. (23.62 x 23.62 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

untitled [exterior mural], 2022

Inkjet print on vinyl

Two parts: left panel, 71 1/2 x 51 1/2 in (181.61 x 130.81 cm); right panel, 71 1/2 x 478 1/2 in (181.61 x 1215.39 cm)

Nina Chanel Abney earned her BFA from Augustana College and her MFA from the Parsons School of Design. Abney’s solo museum exhibition Royal Flush (2017) at the Nasher Museum of Art, North Carolina, traveled to the Chicago Cultural Center; Institute of Contemporary Art and the California African American Museum in Los Angeles; and the Neuberger Museum of Art, Purchase College, State University of New York. Abney has exhibited widely in additional solo presentations and group shows at venues including the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston; the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia; and the Palais de Tokyo, Paris, France. Abney has created multiple site-specific, public commissions, including most recently a commissioned mural for the High Line, New York, a major project for the World Center, Miami and another at the David Geffen Hall at Lincoln Center, New York. Her work is held in numerous public and private collections, including the Bronx Museum; the Brooklyn Museum; the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Rubell Family Collection; the Whitney Museum of American Art; and the Burger Collection, Hong Kong.

Maisea Bailey

Erin Baldner

Tanja Baumann

Max Beback

Emily Blanche

Nina Bozicnik

Margarita Burnett-Thomas

Emily Canning

Kat Carter

Harold Churchill III

Fiona Clark

Hannah Hunt Corpuz

Madeleine Craig

Jeff Deveaux

Stephanie Eistetter

Stephanie Fink

Orlando Francisco

Nan Garrison

Trevor Goosen

Claire Kenny

Rachel Ann Kessler

Danielle Khleang

Laura Kinney

JeeSook Kutz

Tony Lasley

Summer Li

CJ McCarrick

Mita Mahato

Sophia Marciniak

Markie Mickelson

Shamim M. Momin

Adam Monohon

Erica Montine

Tricia Pearson

Nick Pironio

Rubina Postma

Ann Poulson

Bob Rini

Ian Siporin

David Smith

Sage Sommer

Phil Steyh

Tiffany Turpin

Lena Whittle

Sylvia Wolf

Eric Zimmerman

DESIGNER

Summer Li

Nina Chanel Abney: Fishing Was His Life is organized by Nina Bozicnik. The collages on view in the exhibition are the culmination of Abney’s 2020 Gordon Parks Foundation Fellowship. Media sponsorship generously provided by KEXP.

© 2023 Henry Art Gallery