EDITOR: CADE ENGLAND

MANAGING EDITOR: KATE JACKSON

COPY EDITOR: SYDNEY GREENE

LAYOUT EDITOR: SARAH STARNES

WRITER: OWEN EDGINGTON

WRITER: GIANNA MICELI

WRITER: MADISON TURNER

WRITER: OLIVIA BARRETT

WRITER: SIERRA LUBETKIN

WRITER: KATIE MCCLURE

WRITER: KATHERINE SCALZO

WRITER: SYDNEY GREENE

WRITER: EDEN ROBBINS

ADVISOR: DR. J.D. GANTZ

MISSION STATEMENT

HENDRIX SCIENTIFIC’S PURPOSE IS TO IMPROVE OUR ABILITIES TO COMMUNICATE SCIENCE IN A WAY THAT IS ACCESSIBLE TO ALL AUDIENCES. AS WE LEARN TO SYNTHESIZE SCIENTIFIC DISCUSSIONS, NEWS, AND RESEARCH AT HENDRIX AND BEYOND, WE WILL GRASP A BETTER UNDERSTANDING OF SCIENCE OURSELVES.

INTERESTED IN SUBMITTING? GO TO OUR INSTAGRAM OR SCAN THE QR CODE BELOW! FOLLOW

2 | HENDRIX SCIENTIFIC Volume II: The Emergent Issue 4. NATURE: A WORLD OF COMPETITION OR COOPERATION? 6. THE RACE FOR SPACE 8. A MEDICINE CABINET IN YOUR BACKYARD 11. ANTEATERS 101 13. FERTILITY’S CHARM: ENHANCED FACIAL AND ODOR ATTRACTIVENESS IN THE MENSTRUAL CYCLE’S PEAK 15. DOES MELATONIN ACTUALLY IMPROVE SLEEP? THE SCIENCE OF SUPPLEMENTS 18. SEEING SOUNDS, TASTING SHAPES, AND COLOR CODING THE ALPHABET 19. THE SACRED SPECIES 21. JITTERBUG: A LOOK AT THREE SUPERFICIALLY SIMILAR CAUSES OF MOVEMENT DISORDER

US ON INSTAGRAM! @HENDRIXSCIENTIFIC

NOTE FROM THE EDITOR

CADE ENGLAND

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

I find Hendrix Scientific special because it is a place for students across all academic disciplines to share their passion for scientific ideas. This issue in particular features many works from students of the Hendrix-In Costa Rica 2023 study abroad group. These students took ideas that excited them from their time in Costa Rica and turned them into engaging stories to practice the art of science communication. This issue of Hendrix Scientific features articles describing a broad array of scientific ideas. The articles showcases Hendrix Students’ diverse interests and different styles of science communication. Part of Hendrix Scientific’s Mission is to give students a space to try out different methods of science communication and you will discover them as you read this issue. Hendrix’s liberal arts curriculum gives each student a background in a variety of subjects, and I believe you will be able to pick up on that as you read. I am beyond excited to introduce you to the second issue of Hendrix Scientific. We are incredibly thankful for our readers for giving us an audience to share our joys of science with. We hope that you enjoy this issue just as much as we have.

Have any questions or want to get involved in Hendrix Scientific? Reach out at hendrixscientific@gmail.com.

SPRING 2024 | 3

NATURE: A WORLD OF COMPETITION

OR COOPERATION?

OWEN EDGINGTON

Imagine the HMS Beagle rounding the coast of the Galapagos Islands. Charles Darwin is perched in the bow, sketching finches with charcoal and parchment. We’re taught that his singular genius allowed him to transcend the thinking of his time and chart science on a new course.

What we lack is context

Darwin did not exist in a vacuum. Like all pioneers, he was influenced by the frameworks of his time. As Darwin departed on his first voyage in 1831, he brought with him ideas from the tight-knit circles of the English intellectual elite. This is the golden age of classical liberalism, a political philosophy that argues for free market economics and the rights of the individual. Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, John Locke’s obsession with individual property rights, and the resource scarcity economics of Thomas Malthus were just part of a wave of cultural thinking that saw competition as the driving force behind much of the world’s success. It was almost inevitable that, as Darwin laid eyes on the wildlife of the Galapagos Islands, competition would be close to mind. In his book, On the Origin of Species, Darwin writes that “[natural selection] is the doctrine of Malthus applied with manifold force to the whole animal and vegetable kingdoms.” And funnily enough, he wasn’t alone in his discovery. Around the same time, another English naturalist by the name of Alfred Russel Wallace was exploring the Malay Archipelago in search of the famed birds-of-paradise. During his eight-year voyage, Wallace collected thousands of specimens of birds, insects, and other wildlife to be shipped home to museums in England. But in 1858, caught in the grip of a malarial fever, Wallace had a breakthrough. What if these vibrantly colored birds were competing for mates in each successive generation? Could this reproductive pressure — multiplied by millions of years — be the mechanism of evolution? Wallace immediately began writing a letter to his contemporary, Charles Darwin. Opening the letter a world away, Darwin was shocked that the theory he had spent the better part of two decades constructing was in the hands of someone else. He rushed to publish On the Origin of Species, spelling out the role of natural selection in evolution. Both men

independently came to the idea, but Darwin received the lion’s share of the credit. But you already knew that: we don’t learn Wallace’s name in school. Both men envision a world of scarcity. A world inhabited by species fighting tooth and nail to survive. Increasingly however, new discoveries are pointing to an undiscovered chapter in the story of evolution: cooperation. Think back to high school biology for a second. Remember the symbiosis unit? If your school was anything like mine, you might have collected a decent handful of examples of different species working together in unexpected ways. Maybe you know about sharks and pilot fish. Pilot fish swim into a shark’s mouth to pick out chunks of decomposing food stuck between its teeth. The shark gets a free dental check-up and the fish get a free meal. Or maybe you’ve heard one of the other half-dozen examples the biology textbooks trot out. Crocodiles and birds, sea anemones and clownfish. Algae and coral. We are taught that symbiosis is some rare and exciting event in nature. But cooperation is everywhere.

Let’s look at the forest

Trrees and fungi share a partnership called mycorrhizal symbiosis. Thousands of species of fungi establish connections with the root systems of different trees, creating a vast network of thread-like structures called hyphae. This network expands each tree’s access to water and nutrients, increases an individual tree’s immunity to disease, and supports the growth of seedlings. Imagine a sprawling city underneath the soil. Bustling trade centers shuttle energy in all directions. Come to think of it, a city might not be a large enough unit: the fungal connections in the top ten centimeters of Earth’s soil stretch approximately 450 quadrillion kilometers, roughly half the width of our galaxy! Belowground, the idea of a single tree — or even a single species of tree — making its own way in the forest quickly falls apart. Such bewildering interconnectedness has led some scientists to redefine forests as superorganisms. Another name that has infiltrated the scientific literature — The Wood-Wide Web — nods to the similarities between this natural network and the Internet. There’s even research showing

| NATURE

4 | HENDRIX SCIENTIFIC

that dying trees release their resources to other plants. Such altruism is hard to reckon against the traditional narrative of nature’s fierce competition. Okay, I can feel your eyes rolling. So plants are little communists. Big deal.

Let’s look at our own bodies

Our digestive systems allow us to… well… digest our food. But we don’t do that alone. More than 10,000 species of microorganisms work within what is known as the human ecosystem, allowing our bodies to function. This fact shines an examining light on theories of individualism — not to mention the idea of humanity as somehow separate from nature. By zooming out our scientific lens from the individual to the ecosystem, we can see that nature is also selecting partnerships — collaborations. Whether we choose to believe it or not, we rely on cooperation to survive. Without microbes, we couldn’t digest our food. Without mycorrhizal fungi — which bond with roughly 90% of the world’s plant species — we wouldn’t have food to eat. A tendency emerges in the sciences toward the binary and the specific. The binarity perhaps springs from a devotion to observation. There are things we can perceive and there are things that defy perception: the seen and the unseen. Does a tree stand alone or do its roots stretch to encompass an entire forest? Does the human body function as an autonomous unit or is it involved in an ecosystem of thousands of microbes? Our answers to these questions — and indeed the questions themselves — need not exist in binary space. In terms of specificity, notice the ever-increasing specialization of scientific inquiry — the inclination towards the narrow and the niche over a generalist’s interdisciplinarity. When our collective knowledge exists in fragmented isolation, problems emerge. How do we access knowledge? How do we apply it? How do we share and combine ideas? How do we challenge our biases? Nature is not a story of competition or cooperation. It’s a story of both. In our total acceptance

of competition, we forget we are constantly reframing the limits of our knowledge. We forget knowledge is infinite only when shared. We forget we live in an interdisciplinary universe. And we allow ourselves to buy into our greatest mistake: the belief that we’ll ever reach some final answer.

References:

Darwin, Charles. 1859. On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. London. Murray.

van der Heijden, M.G.A., Martin, F.M., Selosse, M.-A. and Sanders, I.R. (2015), “Mycorrhizal Ecology and Evolution: The Past, The Present, And The Future.” New Phytol. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.13288

Society for the Protection of Underground Networks (n.d.) Underground Networks. https://spun.earth/networks

Higgins, Nick, and Jennifer Frazer. 2015. “Dying Trees Can Send Food to Neighbors of Different Species.” Scientific American Blog Network.

“NIH Human Microbiome Project Defines Normal Bacterial Makeup of the Body.” 2012. National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Filotas, E., L. Parrott, P. J. Burton, R. L. Chazdon, K. D. Coates, L. Coll, S. Haeussler, K. Martin, S. Nocentini, K. J. Puettmann, F. E. Putz, S. W. Simard, and C. Messier. 2014. “Viewing Forests Through the Lens of Complex Systems Science.” Ecosphere 5(1):1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/ ES13-00182.1

Feijen, F.A.A., Vos, R.A., Nuytinck, J. et al. Evolutionary dynamics of mycorrhizal symbiosis in land plant diversification. Sci Rep 8, 10698 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-28920-x

SPRING 2024 | 5 © Lukas Droz / Adobe Stock

THE RACE FOR SPACE

WHAT ARE BROMELIADS?

GIANNA MICELI

Bromeliads are epiphytes, a type of plant that grows on top of another plant, typically trees. They gain their water and nutrients from moisture in the air (humidity in the atmosphere), rain, and their surroundings. Their roots do not touch the ground, so they are not considered parasitic. More specifically, bromeliads can be identified by their cupped leaves that hold water and look like they are reaching out to you for a gentle tickle on the walk by. They also produce beautiful large flowers that last for weeks at a time and grow at a rapid rate. Epiphytes thrive in the cloud forest region of Costa Rica due to the excessive moisture in the air from humidity and the abundance of surrounding nutrients from the density of life in this environment. Bromeliads specifically are C3 plants (along with almost all other trees), meaning that when they carry out normal photorespiration, “plant metabolism”, and do not have any special adaptations to conserve water. After dark they completely stop their metabolism because doing so allows them to store and retain more water. Bromeliads hold small water pools in their leaves that provide habitats for frogs, invertebrates, and microorganisms alike.

Why is there a race for space?

Because the rain forest is already so dense, there is a limited amount of sunlight that reaches its floor. The next step for plants is to move upwards. By growing on trees, bromeliads can gain access to the sunlight that they need while also avoiding crowding by competing plants. As previously mentioned, the cupped appearance of their

leaves allows them to house microorganisms, frogs, and invertebrates, and allow for pollinators to spread their pollen. Without the help of pollinators, bromeliads can be naturally pollinated, letting the wind, rain, and other natural forces carry their seeds. Bromeliad seeds have small barbs on them, which allows the seeds to latch on to bark and other surfaces to remain high up on trees. However, with deforestation, urbanization, and an increase in competition due to climate change, bromeliads are finding new homes on more urban surfaces such as bridges, telephone poles, wires, houses, and more.

The Future of epiphytes?

Deforestation not only increases competition for all epiphytes, but it also decreases the number of these plants that are able to survive. If the seed does not land in a spot where the bromeliad can get proper amounts of sun, water, and nutrients, then the bromeliad seeds will never have the opportunity to sprout. If another epiphyte starts growing on top of the bromeliad it causes a significant decrease in the bromeliad’s sunlight intake. This can then lead to a rapid decline in health for the bromeliad. Climate change is also a growing concern in regard to the future of epiphytes. Because of rising temperatures and their effects, animals and plants alike are migrating upward in elevation to find cooler temperatures. What does this mean for the animals and plants already living at higher elevations? Animals and plants will start moving upward as a chain reaction. Those who can move upward fast enough will ultimately survive and adapt, whereas those who migrate too slowly may be out-competed and go extinct. As for those who are already at the

| NATURE

6 | HENDRIX SCIENTIFIC

top and have nowhere else to go, they will also eventually die due to the other plants moving up and out competing them for the space at the top, creating a vicious cycle. Not only will climate change affect one level at a time but eventually with no solution, we will start to witness extinctions of plant species and potentially animal species that rely on the plants that are going extinct due to the decline in the integrity of ecosystems in Costa Rica. As for urbanization, most human communities and societies are continuously growing and developing, which can be a good thing. But we must consider the potential ramifications if we urbanize without considering nature and the life surrounding us. If we practice sustainable and controlled growth, then we give a chance for both life and nature itself to live alongside us in a harmonious manner.

What we can do to Help

We have created a world in which nature adapts to survive us: a world which some would argue is unnatural. However, hope is not lost. We may be able to create a new narrative; one that tells a story of us working with and living harmoniously in nature. As mentioned by Daniela Quesada Cruz from Mi Ocotea, a conservation group dedicated towards education and conservation of Ocotea Monteverdensis, if we push a tree to extinction, its ecosystem will feel the effect and

slowly start to lose its integrity. The loss of one tree could result in the loss of whole ecosystems. To help, we can start practicing conservation efforts— but not just for the bromeliads. We must look at their habitats, like the cloud forest, and work to keep them intact, strong, and diverse. The cloud forest is starting to get smaller due to climate change and deforestation. Progress can be made by working with, volunteering for, or donating to local conservation foundations and organizations such as the Monteverde Institute or the Children’s Eternal Rainforest. The Monteverde Institute, carries out projects based on education and research within a sustainable and peaceful community. Some of their initiatives, including the Mi Ocotea project, have been a step in the right direction in trying to adopt more sustainable living practices and in working to educate others about the problems at hand. The Monteverde Institute is also working to teach people about how to help and give back to the environment in a meaningful, long-lasting way.

References

References

“Children’s Eternal Rainforest, Costa Rica’s Largest Private Reserve.” ACMCR, 10 Mar. 2022, acmcr.org/content/. Menesses, Walter. “Personal Communication.” Monteverde Institute, 4 July 2023, monteverde-institute.org/. Russ, Karen, et al. “Bromeliads.” Home & Garden Information Center | Clemson University, South Carolina, 15 Apr. 2020, hgic. clemson.edu/factsheet/bromeliads/.

“Children’s Eternal Rainforest, Costa Rica’s Largest Private Reserve.” ACMCR, 10 Mar. 2022, acmcr.org/content/. Menesses, Walter. “Personal Communication.” Monteverde Institute, 4 July 2023, monteverde-institute.org/. Russ, Karen, et al. “Bromeliads.” Home & Garden Information Center | Clemson University, South Carolina, 15 Apr. 2020, hgic.clemson.edu/ factsheet/bromeliads/.

White, Jason. “What Are Epiphytes? All About Epiphytic Plants And Their Care.” All About Gardening, 15 Mar. 2023, www. allaboutgardening.com/epiphytes/.

White, Jason. “What Are Epiphytes? All About Epiphytic Plants And Their Care.” All About Gardening, 15 Mar. 2023, www.allaboutgardening.com/ epiphytes/.

SPRING 2024 | 7

© Elder / Adobe Stock

A MEDICINE CABINET IN YOUR BACKYARD

GIANNA MICELI

Imagine being able to walk into your backyard and finding a plant that can cure almost any ailment or that can act as a supplement for your diet. It is so easy for Americans to go to the store, go to a medicine aisle, and find a pill to make us better. Not everyone has access to an abundance of reliable medications, and it isn’t always as easy as walking to a convenience store. While in Costa Rica I was lucky enough to learn about medicinal plants native to this country. The lush rainforest accounts for some geographical inaccessibility, making it difficult to access clinics, doctors, medicines, or even first aid supplies. Coupling this with high medication costs it makes it even harder for people to get medical help and treatment. Medicine, however, didn’t always come in the form of pills and liquid chemicals. It started in nature, with natural remedies for a plethora of ailments and injuries. With the knowledge that has been passed down from their ancestors, it is common for the people of Costa

Rica to head into their backyard or into the rainforest to get the medicine they are looking for. Surprisingly, some don’t even trust the medications from pharmacies and instead visit the doctor to get a diagnosis before going home and finding the plant they need to get better. In this article I will be focusing on the plants I was lucky enough to learn about when I visited San Luis.

Coffee

Coffee beans act as a natural stimulant that wakes up the central nervous system, which receives, processes, and responds to sensory information. Coffee can improve heart health, manage Parkinson’s disease symptoms, protect from type two diabetes, slow the progression of dementia, and safeguard the liver (Frankhart). However, people with high metabolic rates should be careful, as coffee could potentially increase levels of anxiety (Jose and Lucas, 2023).

Not only do these benefits syou a boost

8 | HENDRIX SCIENTIFIC | MEDICINE

© Picture of the view from the Casitas De Montanya Cabuya in San Lusi, Costa Rice. Taken by Gianna Miceli

add-ins such as sugar, milk, creamer may disrupt the chemical composition of caffeine rendering it less effective.

Madero Negro

Madero negro, aka quick stick, is a plant in the legume family and is commonly used as a natural fence in Costa Rica due to the privacy produced by its dense foliage and the strength of its wood. People also use it to safely remove bats from their house because bats are repulsed by the smell of it. Additionally, if you place smaller branches from this tree under your bed, it can act as an insect repellent. While it may be toxic when fermented or cooked, Madero negro can also be used as a natural remedy for colds, cough, fever, headache, burns, rheumatism, ulcers, and wounds (Plants for A Future, 2023). Because remedies have been passed down for many generations, it is still unclear exactly how Costa Ricans utilize the positive properties of this plant without succumbing to its toxicity.

Guayaba

The guayaba tree, or the guava tree in English, has incredible medicinal properties. One of these properties includes the tree containing high amounts of antioxidants which prevent cell damage from oxidation, which slows down cell aging. The entire tree from the bark all the way to the leaves and fruit can be used for medicinal purposes. Some common uses include as an anti-diarrheal (by boiling its leaves to make tea), to improve coordination, as pain relief, and to remove blockages within the body (Naseer et al., 2018).

While the fruit from this tree is delicious right off the branch, you can also find it in candies, jams, and jellies. This makes it a tasty and easy “medicine” to consume compared to some of the more processed and synthetic alternatives that we are used to.

Targua

Targua is a member of the poinsettia family. It is fast growing and belongs to the secondary forest (the new forest that is growing after the mass deforestation in Costa Rica). This plant releases white latex from its bark that can be used as natural sunblock and for other cosmetic uses. Some people harvest the latex from this tree and put it on their faces like cream because

they believe that it makes them look younger

and that it reduces the appearance of wrinkles. This plant, however, is not just used for beauty and skincare. You can drink small amounts of it mixed in with water to treat ulcers, clean your teeth, and relieve cavity pain.

Imagine clear, blemish, and wrinkle free skin alongside clean teeth. What more could a person ask for, especially, from a tree? Many Costa Ricans believe that it is imperative to ask and thank the plant for the services and materials that it gives you. There is a balance of both giving and taking which we must remember when taking from nature. This balance and all ecological relationships that Costa Ricans have are filled with love and the personification of nature because why not say please and thank you to things, other than people, that can give you so much?

Ortega

The Ortega plant is less friendly in appearance. It is a part of the Nettle family meaning that if touched, it can sting. This plant is also covered in tiny hairs that can irritate your skin. To avoid getting an irritating rash, this plant should be handled gently by the stem. Although this plant may seem scary, those with medicinal knowhow can turn the Ortega into a mature shrub that produces berry-like vegetables. However, different parts of the plant can be used as a remedy for headaches, fever, indigestion, asthma, diabetes, and ulcers (Islam et al., 2018).

SPRING 2024 | 9

©Gianna Miceli

Cecropia/ Guarumo

Cecropia is a plant that we know was used by the indigenous peoples of Costa Rica, and is still used today in the same fashion as it was in the past. Tea from its leaves has been used to induce contractions in women and has typically been used by farmers to help cows release their placenta after giving birth. Similarly to humans, after giving birth, an organ called the placenta (which grows in the uterus providing nutrients and oxygen to the baby) must also be passed. Also, with the correct dosage, this plant can be used in another form of tea that can treat insomnia.

Additionally, this tree has a bark that is hollow and can be used as a natural pipe. However, ants tend to live inside these trunks, so use caution. The bark not only gives the ants a home, but it also protects the living portion of the tree from ant damage.

Wild Chiles

While this does seem like a vast category, chiles can be used for a variety of medicinal purposes (Figure 1.7). They are good for preventing and treating parasites, gastritis, and gastrointestinal cancer. Not to mention they also taste delicious and can enhance the flavor of foods while also containing high amounts of alkaloids which are good for potentially reducing the risk of cancer. Wild chiles are rich in both vitamins and minerals and have preventative and therapeutic properties for rheumatism, stiff joints, bronchitis, chest colds (with a cough and headache), arthritis, heart arrhythmias and more (Saleh eat al., 2018). Now imagine the potential health benefits if you just add a little spice to your coffee.

An Entire Cabinet

While I did narrow the focus of this paper down to the few species that I learned about while in San Luis, just imagine what other secrets are hidden within nature. Just think how many other plants there are, and the possible benefits they offer. With the plants that I have discussed in this paper alone the plants could potentially offer: preventative and therapeutic properties for rheumatism, chest colds, arthritis, heart arrhythmias (wild chiles), can induce contractions in women (cecropia), manage Parkinson’s disease symptoms, protect from type two diabetes, slow the progression of dementia, safeguard the liver (coffee), and more. While there may not be a cure for everything, medicinal uses of plants pose potentially positive and effective alternatives to synthetic medications that can be costly and inaccessible.

References

Britannia, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Nitrogen fixation”. Encyclopedia Britannia, 30 Mar. 2023. Frankhart, Colleen. “Health Benefits of Coffee.” Rush University System for Health, RUSH.

Islam, Baharul, and Muhammad Torequl Islam. “Solanum Violaceum Ortega, a Promising Medicinal Plant - ResearchGate.” ResearchGate, May 2018.

Jacq., and Walp. “Gliricidia Septum.” Pfaf Plant Search, Plants for a Future.

Jose and Lucas, “Personal communication”. 12 July. 2023. Naseer, Sumra, et al. “The Phytochemistry and Medicinal Value of Psidium Guajava (Guava).” Clinical Phytoscience, vol. 4, no. 1, 12 Dec. 2018. Saleh, Brhan Khiar, et al. “Medicinal Uses and Health Benefits of Chili Pepper (Capsicum Spp.): A Review.” MOJ Food Processing & Technology, MedCrave Publishing, 5 July 2018.

That, Lauren, et al. “The NCBI Handbook - NCBI Bookshelf - National Center for Biotechnology ...” Anatomy, Central Nervous System, 10 Oct. 2022.

10 | HENDRIX SCIENTIFIC

© Simon Dannhauer / Adobe Stock

ANTEATERS 101

MADISON TURNER

You look up into the canopy of Costa Rica’s lush jungle, where vibrant biodiversity thrives in every corner. From the mesmerizing melodies of tropical birds to the dense canopy of towering trees, these jungles are a loving tapestry of life waiting to be explored. Your eyes spot something rustling among the leaves. It doesn’t look like a monkey and has a huge bushy tail with an enormous tongue snaking its way along a branch. It’s not a mythical creature, it’s an anteater! As one delves deeper into Costa Rica’s jungles, the focus shifts from a personal experience to a broader perspective. In the heart of this vibrant ecosystem, anteaters become the protagonists of a fascinating narrative, navigating their way through the dense jungle as the story of these remarkable creatures unfolds. The two most common species of anteaters found in Costa Rica are the giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla) and the tamandua (Tamandua Mexicana) (Anteater, n.d.).

Physical Characteristics of Anteaters

Anteaters have unique physical characteristics that make them instantly recognizable. Their long and slender bodies covered in coarse fur are just the sideshow compared to their most distinctive feature: an elongated snout. The anteater’s snout tapers into a tube-like structure and is home to their long, sticky tongue. An anteater’s tongue can reach up to two feet in length and is painted with extremely sticky saliva that allows them to capture insects with laser-like precision. The head of the anteater is relatively small compared to the rest of its

body, with little eyes and rounded ears. Due to their small eyes, their eyesight is generally poor, but they possess a secret superpower: an expert sense of smell. Anteater’s keen sense of smell helps them to locate their prey and sniff out predators from miles away. Anteaters have no teeth, so they rely completely on their stomach acid to digest their food. These amazing creatures also have powerful forelimbs with huge claws that are perfectly suited for digging (Giant Anteater | Smithsonian’s National Zoo, 2016).

Giant Anteaters

The giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla) is found in northern and central regions of Costa Rica among grasslands, savannas, and tropical forests. In terms of size, the giant anteater is the largest among the species, reaching up to 7 feet in length and weighing in at a whopping 90 pounds. Giant Anteaters have a specialized diet consisting almost entirely of ants and termites. They have a special feeding habit to obtain their prey, using their powerful front claws. They tear open termite mounds or ants nests. They then insert their long snout into the openings and flick their long, sticky tongue in and out rapidly to capture the insects. Using this method, A single giant anteater can consume thousands of ants or termites in a single day (Giant Anteater, Facts and Photos, n.d.).

Tamanduas

Within the rich biodiversity of Costa Rica, Tamanduas, close relatives of the iconic giant anteaters, share a similar ecological role while offering a unique perspective on these vibrant ecosystems. There are two types of Tamanduas that can be spotted throughout the southern and northern parts of Costa Rica: the southern tamandua (Tamandua tetradactyla)

SPRING 2024 | 11 | WILDLIFE

and the tamandua (Tamandua Mexicana). They are arboreal creatures, meaning they prefer to spend most of their time in trees. Tamanduas can be spotted throughout the country’s forests, including both the rainforest and the dry forests (Anteaters, n.d.). Tamanduas are normally about half the size of giant anteaters and even vary in appearance depending on which region they are from The southern tamandua has a black coat with a distinctive white ‘V’ marking on its back, while the northern tamandua has a similar coat but with a bigger band of white across its back. Tamanduas have a similar diet to giant anteaters, but they also incorporate other small insects into their meals. While tamanduas’ primary food source remains ants and termites, they have been known to snack on other invertebrates such as beetles and bees. They use their long snouts and sticky tongues to extract these insects from tree bark or other hiding places (Giant Anteater, Facts and Photos, n.d.).

Role in Nature

Anteaters play an important role in nature and the balance of Costa Rican ecosystems, where they are highly specialized insectivores, or “mother nature’s insect control”. By consuming large quantities of ants and termites , anteaters help control insect populations. Ants and termites are considered pests in some cases, but anteaters act as natural pest controllers, keeping insect populations in check. This contributes to maintaining ecological balance and preventing outbreaks of these insect species (Giant Anteater Conservation, n.d.). Anteaters, especially giant anteaters, cause major modifications to their habitat. When they use their powerful claws to dig into termite mounds and ant nests, anteaters create openings and reshape the soil landscape. These openings can create new microhabitats, which benefit other organisms like smaller animals or plant species (Giant Anteater | Smithsonian’s National Zoo, 2016). Additionally, when anteaters move through their habitats, they disperse seeds through the forest. Seeds get stuck in the anteater’s fur and fall off as their fur rubs against trees and other plants. This mechanism of seed dispersal helps plant species reach new areas, contributing to forest regeneration and biodiversity (Anteater, n.d.).

Conversation Efforts

Anteaters are extremely important to Costa

Rica, but their population is decreasing at an alarming rate. Only about 5,000 anteaters remain in the wild. The International Union of Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists them as vulnerable due to habitat loss and climate change (Giant Anteater Conservation, n.d.). Deforestation and agricultural expansion shrink the forest, grasslands, and other ecosystems where anteaters reside. As their habitats shrink, anteaters face challenges in finding sufficient food resources and suitable territories. The impacts of climate change, such as altered rain patterns and habitat shifts, can affect the availability of the ant and termite populations that anteaters rely upon for food. Changes in temperature and rainfall patterns disrupt the timing and abundance of insect colonies, impacting anteaters’ success of finding food (Giant Anteater Conservation, n.d.). Conservation efforts are crucial to addressing these challenges and protecting anteaters. Collaboration between governments, conservation organizations, local communities, and stakeholders is vital to ensure the long-term survival of anteaters and their habitats. Donating to organizations, such as Grow Jungles: Giant Anteater project, and the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, allows for people to support conservation efforts in Costa Rica from hundreds of miles away (Giant Anteater | San Diego Zoo Animals & Plants, n.d.). Anteaters are remarkable creatures with their specialized adaptations and crucial ecological roles. Unfortunately, they remain vulnerable to various threats. Conservation efforts aimed at protecting their habitats are essential for ensuring the survival of these fascinating animals for future generations to appreciate and learn from.

References anteater. (n.d.). Encyclopædia Britannica; Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved July 6, 2023, from https://www.britannica.com/animal/anteater Anteaters. (n.d.). Costa Rica; https://www.costarica.com. Retrieved July 6, 2023, from https://www.costarica.com/wildlife/anteaters

Giant Anteater | San Diego Zoo Animals & Plants. (n.d.). Home | San Diego Zoo Animals & Plants. Retrieved July 6, 2023, from https://animals. sandiegozoo.org/animals/giant-anteater

Giant anteater | Smithsonian’s National Zoo. (2016, April 25). Smithsonian’s National Zoo. https://nationalzoo.si.edu/animals/giantanteater

Giant Anteater Conservation. (n.d.). Nashville Zoo at Grassmere | Nashville, TN. Retrieved July 6, 2023, from https://www.nashvillezoo.org/ anteater-conservation

Giant anteater, facts and photos. (n.d.). Animals. Retrieved July 6, 2023, from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/mammals/facts/giantanteater

12 | HENDRIX SCIENTIFIC

FERTILITY’S CHARM: ENHANCED FACIAL AND ODOR ATTRACTIVENESS

IN THE MENSTRUAL CYCLE’S PEAK

OLIVIA BARRETT, SIERRA LUBETKIN

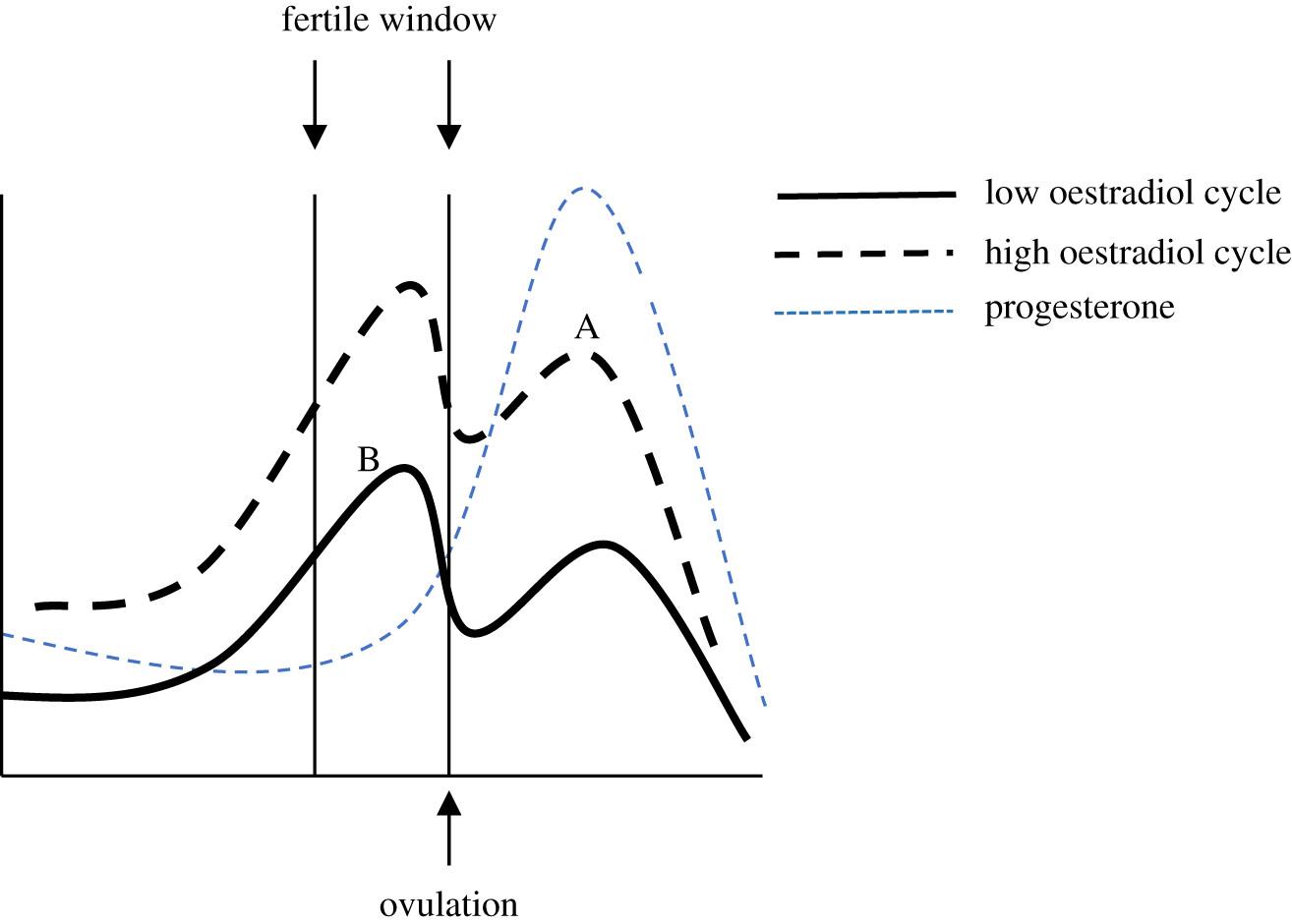

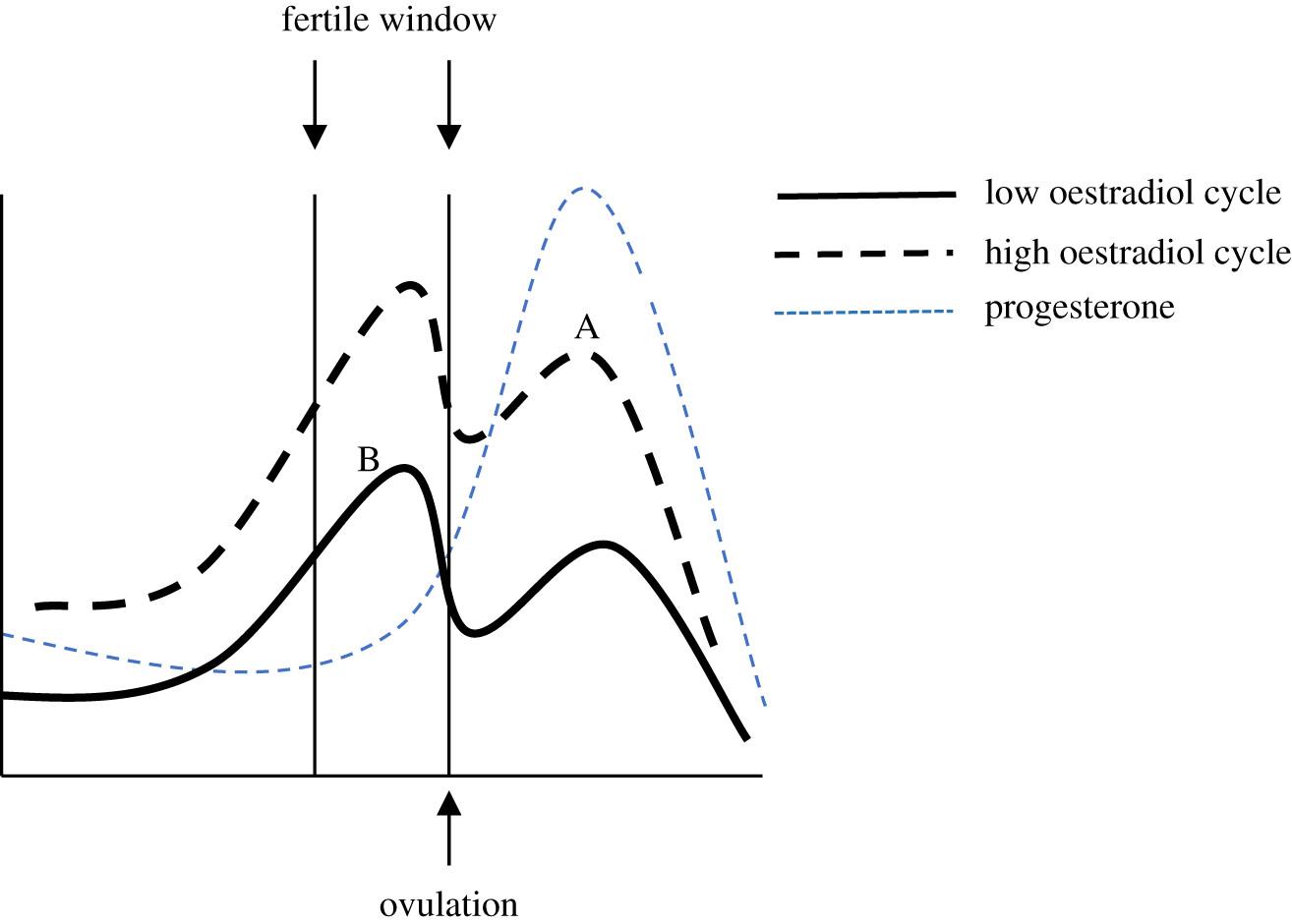

Agrowing body of research suggests that fluctuating hormone levels across one’s menstrual cycle could be responsible for changes in one’s perceived attractiveness. Specifically, ovulating people are rated as more attractive during their fertile window, or when they can conceive a fetus. This has been studied in non-human primates and other animals; recently, research has indicated that ovulating humans may be perceived as more attractive during this window—both in their facial features and odor attractiveness. Research done in Prague and the United Kingdom conducted in 2004 shows that people who experience menstruation appear more attractive during their fertile window compared to their luteal phase (Roberts et al.). The fertile window spans the five days before ovulation and the day of ovulation, the time in which getting pregnant is most viable. The luteal phase occurs right before menstruation and is characterized by the thickening of the uterine lining to prepare for shedding. This theory was tested by asking male and female identifying people to first look at pictures of people during their fertile window and luteal phase, and to then identify which photo they found more attractive. This study discovered that participants found images of people in their fertile window to be significantly more attractive than during their luteal phase (Roberts et al., 270). This continues to be true even when the images were digitally masked to change the hair and ears in the images. The images below are an example of the unmasked images used; (i) was taken during their fertile window and (ii) was taken during their luteal phase. Although these differences are subtle, this information tells us much more about humans’ biological efforts

to reproduce. Increased attractiveness during ovulation could increase the mating pool and signal fertility to possible partners. An additional fascinating finding was that these differences in appearance were recognized more by women, which suggests that women are more aware of and able to distinguish these differences. One then may wonder if this ability arose because of the pressure society has put on women to value their own appearance, thereby leading them to be more aware of the appearances of others. A different study suggests that another aspect of attractiveness is enhanced by ovulation: one’s scent. In this study done in 2022, Roney et al. examined the difference in odor attractiveness throughout an individual’s menstrual cycle. For this research, people who ovulate provided scent and saliva samples throughout their menstrual cycle. Their scent samples were then rated by people who did not know their menstrual status. The researchers found that people who were ovulating were rated as more attractive compared to those who were not ovulating; additionally, the same women were rated as smelling more attractive when they were ovulating than when they were not. Findings from the saliva samples indicated a correlation between oestradiol and odor attractiveness, which may indicate that

SPRING 2023 | 13 | HUMAN PHYSIOLOGY

© Stockbusters / Adobe Stock

this hormone is responsible for the difference in odor attractiveness (interestingly, in nonhuman primates, dosages of oestradiol is shown to restore odor attractiveness, providing precedence to the idea that oestradiol may do the same in humans enhances human attractiveness). However, more research is necessary to affirm or deny a causal relationship in humans. These new findings reinforce prior research that suggests that people are viewed as more attractive in the menstrual cycle, when they can conceive, than in other times (Singh, et. Al; Scutt, et. al). The window around one’s ovulation time was associated with higher ratings of attractiveness in their facial features and odor attractiveness. This research can provide an empowering message: that while the menstrual cycle is largely stigmatized, changes across the menstrual cycle are normal and can even accentuate one’s inherent beauty.

References:

Mei, Mei, et al. “Does Scent Attractiveness Reveal Women’s Ovulatory Timing? Evidence from Signal Detection Analyses and Endocrine Predictors of Odour Attractiveness.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, vol. 289, no. 1970, Mar. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2022.0026. Accessed 20 Apr. 2022.

Roberts, S. C., Havlicek, J., Flegr, J., Hruskova, M., Little, A. C., Jones, B. C., Perrett, D. I., & Petrie, M. (2004, August 7). Female facial attractiveness increases during the fertile phase of the menstrual cycle. PubMed. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/ articles/PMC1810066/

Penton-Voak IS, Perrett DI, Castles DL, Kobayashi T, Burt DM, Murray LK, Minamisawa R. Menstrual cycle alters face preference. Nature. 1999 Jun 24;399(6738):741–742.

Scutt D, Manning JT. Symmetry and ovulation in women. Hum Reprod. 1996 Nov;11(11):2477-80. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019142. PMID: 8981138. Singh, D. & Bronstad, P. M. 2001 Female body odour is a potential cue to ovulation. Proc. R. Soc. Long. B268, 797-801. (DOI 10.1098/rspb.2001.1589.)

Hormonal changes across a menstrual cycle. The fertile window refers to the time right before ovulation when the menstruating person can conceive. Research suggests that people are rated as more attractive during this window and the

Mei et al.

14 | HENDRIX SCIENTIFIC

©

DOES MELATONIN

ACTUALLY IMPROVE SLEEP? THE SCIENCE OF SUPPLEMENTS

KATHERINE SCALZO

Sleep is one of the few things that all humans (and most animals!) have in common. In fact, we need sleep to survive and thrive. Scientists define sleep by marked behavioral and physiological changes, including reduced responsiveness to external stimuli, reversible unconsciousness, and reduced mobility (Chokroverty, 2010). Some of these distinct physiological changes can be measured via electroencephalography (EEG), electrooculography (EOG), and electromyography (EMG), which assess brain activity, eye movement, and muscle activity, respectively. If sleep is so important, then what happens when it goes awry? Clinical sleep disorders are common; 50-70 million Americans have them (American Sleep Apnea Association, 2022). These disorders and other sleep complaints are also varied; for example, sufferers of insomnia might struggle to fall and stay asleep and experience nonrestorative sleep, along with other disruptive symptoms (Chokroverty, 2009). Sleep deprivation is related to short and long-term consequences like impaired attention and concentration as well as increased risk for health problems like obesity (Chokroverty, 2009). Current popular treatments

for insomnia and other sleep disorders include medication and cognitive behavioral therapy, but these methods can cause side effects and be expensive. Does melatonin supplementation offer a safe and effective alternative?

What is Melatonin?

Melatonin is a hormone that plays a central role in the sleep-wake cycle. The pineal gland in the human brain naturally produces melatonin, but people also often take it as a supplement. Endogenous melatonin refers to melatonin produced within the body, whereas exogenous melatonin is made synthetically and might be taken via a capsule, pill, or liquid. These supplements promise to improve sleep, but (like all dietary supplements) synthetic melatonin is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for any conditions or purposes (Cleveland Clinic, 2022). Melatonin promotes sleep by regulating the timing of the body’s circadian rhythm, signaling to the body what time of day it is so the brain knows when to sleep or be awake. Levels of melatonin peak at night in response to darkness and are lower during the day when the body is exposed to more light (Hardeland et al., 2006).

| MEDICINE

SPRING 2024 | 15 ©Designpics / Adobe Stock

Impact of Melatonin on Sleep

Various studies have explored whether melatonin improves different sleep quality variables in different populations. Farahmand et al. (2018) studied sleep in 21 emergency medicine residents, who were randomly assigned to either a placebo group or a group that would take melatonin. The groups were switched throughout the study such that each participant was in each group twice. Participants in the melatonin group received two 3mg tablets of melatonin at the end of a night shift, and those in the placebo group got two placebo pills. All participants answered a questionnaire about sleep onset, nightmares, sleep length, and other sleep variables. They also took the Karolinska Sleep Scale and the Profile of Mood States survey, which assess drowsiness and mood, respectively. Overall, this study found that the melatonin and placebo groups did not differ significantly in sleep quality (sleep hours, drowsiness, sleep disturbances) or mood. These results suggest that melatonin might not improve sleep, daytime sleepiness, or mood in individuals working night shifts

Wade et al. (2010) studied melatonin as a treatment for insomnia. They were interested in whether the efficacy of prolonged release melatonin (PRM), melatonin that releases gradually, differed depending on age and natural melatonin production. Historically, PRM has been successful in treating insomnia in older adults, but this study explored the treatment in a diverse age range, including 791 participants with insomnia from 18-80 years old. After baseline screening, participants were randomly assigned to take PRM or a placebo orally every night for 29 weeks. Participants filled out a sleep diary every night that included variables like sleep quality, sleep time, and alertness. Additionally, participants underwent physical screens to measure safety variables, vital signs, and natural melatonin production. This study found that PRM helped participants 65-80 years old fall asleep faster, regardless of their natural melatonin production; however, the same effect did not emerge for younger participants. Long term, PRM increased total sleep time in all participants with low natural melatonin levels. Thus, these results suggest that melatonin may only affect older adults and individuals with low natural melatonin production.

Zhdanova et al. (1996) explored whether low doses of melatonin affected objective and subjective measures of sleep in young adult males without sleep disorder diagnoses. Over three sessions in a controlled laboratory setting, 12 participants received melatonin (0.3mg or 1.0mg) or a placebo orally. Treatment nights were followed by an adaptation night in which participants received neither melatonin nor a placebo. On each test day, participants took questionnaires to assess sleep onset, bedtime, and sleep quality. EEG data measured brain activity and different stages of sleep as well as the time it took to fall asleep, the number of awakenings throughout the night, total sleep time, and the ratio of time in bed to time spent asleep (sleep efficiency). Both doses of melatonin significantly decreased the time it took participants to fall asleep and increased sleep efficiency compared to the placebo group, but the supplements did not affect sleep architecture (stages of sleep). Thus, according to these findings, melatonin may be better suited specifically to helping people fall asleep faster rather than improving overall sleep architecture.

Neuroscience of Melatonin: How Does it Affect Sleep?

Melatonin is created in and released from the pineal gland in the middle of the brain. Melatonin affects the brain’s suprachiasmatic nucleus, a structure in the brain that acts as the body’s internal clock, via two types of receptors. Melatonin supplements act as agonists at these receptors, which means that they mimic and

16 | HENDRIX SCIENTIFIC

©Designpics / Adobe Stock

increase the behavior of natural melatonin. Melatonin promotes sleep and can shift one’s circadian rhythm. The activation of melatonin receptors (called MT1 and MT2 receptors) regulates the body’s circadian rhythm and helps synchronize the sleep-wake cycle with night and day so that the body wants to sleep at the appropriate times. Besides melatonin supplements, other melatonin receptor agonists, such as ramelteon (Rozerem) are prescribed to treat insomnia (Liu et al., 2016).

Other Melatonin Information

Individuals can find melatonin readily available in a variety of forms over the counter at drug stores, grocery stores, and the like. Because melatonin is sold as a dietary supplement in the United States, the FDA does not directly regulate it. Thus, individuals should exercise caution when researching and choosing a melatonin supplement. There is little consensus regarding the ideal melatonin dosage, but extremely high doses should generally be avoided (Cleveland Clinic, 2022). Medical professionals suggest starting with the lowest possible dose and changing it as necessary; appropriate dosages will look different for everyone. In studies by Farahmand et al. (2018), Zhdanova et al. (1996), and Wade et al. (2018), researchers used doses of 0.1 mg, 1 mg, 2 mg, and 3 mg respectively. Melatonin is generally well-tolerated when used short-term, but the most common side effects include drowsiness, headaches, nausea, and dizziness (Andersen et al., 2016). Experiencing excessive daytime sleepiness with melatonin supplementation could point to a high dose that should be adjusted. There is a lack of scientific data on the side effects of melatonin in pregnant or breastfeeding women. Limited clinical trials suggest that long-term use of melatonin is safe for healthy adults, but the research is also lacking for children and adolescents (Andersen et al., 2016). It is always wise to consult with a medical professional before starting any new supplement. It is also important to note that there are many simple changes one can make to optimize their sleep that do not involve supplementation, including but not limited to: following a schedule, avoiding caffeine late in the day, and limiting screen use before bed (National Institute for Neurological

Disorders and Stroke, 2023). We as sleepers have the power to make informed decisions about our sleep, and these decisions can be EXTREMELY consequential. After all, research suggests that we spend around one third of our life asleep (National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke, 2023). Make the most of it!

References:

Andersen, L. P. H., Gögenur, I., Rosenberg, J., & Reiter, R. J. (2016). The safety of melatonin in humans. Clinical Drug Investigation, 36(3), 169-175. https://doi-org.hendrix.idm.oclc.org/10.1007/s40261-015-0368-5. American Sleep Apnea Association. (2022, July 27). The state of sleep health in America in 2022. Sleep Health. Retrieved March 5, 2023, from https://www.sleephealth.org/sleep-health/the-state-of-sleephealth-in-america.

Chokroverty, S. (2010). Overview of sleep & sleep disorders. Indian Journal of Medical Research, 131(2), 126-140.

Chokroverty, S. (2009). Sleep disorders medicine: Basic science, technical considerations, and clinical aspects. (3rd ed.) Saunders/Elsevier via Google Books.

Farahmand, S., Vafaeian, M., Vahidi, E., Abdollahi, A., Bagheri-Hariri, S., & Dehpour, A. R. (2018). Comparison of exogenous melatonin versus placebo on sleep efficacy in emergency medicine residents working night shifts: A randomized trial. World Journal of Emergency Medicine, 9(4), 282-287. https://doi.org/10.5847%2Fwjem.j.1920-8642.2018.04.008.

Hardeland, R., Pandi-Perumal, S. R., & Cardinali, D. P. (2006). Molecules in focus: Melatonin. The International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, 38(3), 313-316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocel.2005.08.020.

Liu, J., Clough, S. J., Hutchinson, A. J., Adamah-Biasso, Popovska-Gorevski, M., & Dubocovich, M. L. (2016). MT1 and MT2 melatonin receptors: A therapeutic perspective. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology, 56, 361-383. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010814-124742. National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (2023, July 19). Brain basics: Understanding sleep. Retrieved January 25, 2024, from https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/public-education/brain-basics/brain-basics-understanding-sleep.

Suni, E. (2022). Melatonin: What it is & function. Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved March 4, 2023, from https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/23411-melatonin.

Wade, A. G., Ford, I., Crawford, G., McConnachie, A., Nir, T., Laudon, M., & Zisapel, N. (2010). Nightly treatment of primary insomnia with prolonged release melatonin for 6 months: A randomized placebo controlled trial on age and endogenous melatonin as predictors of efficacy and safety. BMC Medicine, 8(51). https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-8-51.

Zhdanova, I. V., Wurtman, W. J., Morabito, C., Piotrovska, V. R., & Lynch, H. J. (1996). Effects of low oral doses of melatonin given 2-4 hours before habitual bedtime, on sleep in normal young humans. Sleep, 19(5), 423-431. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/19.5.423.

SPRING 2024 | 17

SEEING SOUNDS, TASTING SHAPES, AND COLOR CODING THE ALPHABET

SYDNEY GREENE

ImImagine this: from darkness, you see flashes of vibrant colors. Bright green. Dark red. Electric blue. Then a soft purple before the color-show fades back to black. But you’re not at a concert or watching a movie. You’re listening to music. This far-fetched phenomenon is called chromesthesia, or the ability to visualize colors from external stimuli not directly related to vision, such as listening to music. Chromesthesia is a subset of a larger category of perception conditions called synesthesia, which more broadly refers to the experience of multiple senses from one stimulus (for example, auditory sense input to an experienced visual output, or smell and taste input to various texture outputs, etc.). The word “synesthesia” has Greek origins, with “syn-” meaning “union” and “-aesthesis” meaning “sensation” (Allen-Hermanson and Matey). Synesthesia can be experienced in numerous combinations of the five senses: touch, taste, sight, sound, and smell. Depending on the individual, each of these episodes will occur in the brain via one of two mechanisms: projective synesthesia or associative synesthesia. Projective synesthesia relies on an abnormal neural connection between two brain areas responsible for perceiving different sensory stimuli. Alternatively, associative synesthesia involves unusual feedback from one area of the brain to another, rather than an uncommon physical connection (Gregoire, 2016). Though synesthesia is only experienced by ~2-4% of the general population, there are many renowned artists who experience synesthesia including Van Gogh, Ella Marija Lani Yelich-O’Connor (also known as Lorde), Duke Ellington, and Pharrell Williams (Watson, 2018; Brang, D., & Ramachandran, 2011). However, if you feel like you’re missing out on a fascinating sensory experience, fret not! Some studies have shown that an individual can intentionally train their brain and hone the skills that enable multi-sensory experiences even if they don’t occur naturally. Through practice of associating colors with sounds, certain tastes with textures, or any other blending of sensations with one another, anyone can train their brains to elicit synesthetic events. By doing this, one forges new neural pathways and associations which can have lasting effects on

how the brain synthesizes and recalls information (Gregoire, 2016). Aside from being an intriguing way to experience the surrounding world, synesthesia poses quite a few positive implications for brain health and cognitive function. This phenomenon has been shown to reduce cognitive decline and improve creativity, learning processes, and memory recall. Think of synesthesia as a way for the brain to add more handles onto a memory: the more senses associated with a given memory, the more interconnected its pathways are, thereby creating more opportunity for the brain to recall it. As for the social implications of this phenomenon, individuals with synesthesia should not be held in any higher regard than the other 96% of the general population (Watson, 2018). They simply have more intense manifestations of the same stimuli perceived by those without synesthesia. If anything, research of their heightened perceptions could provide a more accessible way for researchers to study and better understand sensory experiences and neural pathways in the brain. Now, go forth and hear colors, taste shapes, and enhance your experience of the world around you!

References:

Allen-Hermanson, Sean, and Jennifer Matey. “Synesthesia.” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, iep.utm.edu/synesthe/. Accessed 19 Feb. 2024 from https://iep.utm.edu/synesthe/

Brang, D., & Ramachandran, V. S. (2011, November). Survival of the synesthesia gene: Why do people hear colors and taste words? PLoS biology. Retrieved April 2, 2023, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/ PMC3222625/

Gregoire, C. (2016, July 22). Yes, you can teach yourself synesthesia (and here’s why you should). HuffPost. Retrieved April 2, 2023, from https:// www.huffpost.com/entry/a-neuroscientists-guide-to-developing-synesthesia_n_55e4b004e4b0aec9f35429c9

Watson, K. (2018, October 24). Synesthesia: Definition, examples, causes, symptoms, and treatment. Healthline. Retrieved April 2, 2023, from https:// www.healthline.com/health/synesthesia

18 | HENDRIX SCIENTIFIC | MEDICINE

THE SACRED SPECIES

KATIE MCCLURE

Beauty is an abstract concept bringing value to even the most unlikely of things. It is something that is heavily valued in our society- it is how we decide where to live, what to love, and who we want to be. Beauty starts with the eyes, but quickly becomes more. As I stand in the middle of the Costa Rican rainforest, colors of green, red, and blue catch

my eye. I am instantly in awe of the majestic creature before me: the Resplendent quetzal. Its long, bright tail glides through the air, creating an intense experience of utter beauty. And yet, I can’t help but wonder: is beauty the only extent of the quetzal’s value? Quetzals are a part of the Trogon family. Known for their iridescent feathers and bright colors, quetzal habitats range from Mexico to Panama in mountainous regions, making Costa Rica a perfect home (Skutch, 215). Their diet consists of small-seeded fruits, specifically twelve to eighteen species of fruits consistently throughout the year (Wheelwright, 286). That’s why quetzals are often referred to fondly as “fruit specialists” (Ibid). Quetzals rely heavily on Lauraceae, a plant that belongs to the Laurel family (Ibid). The “habitat distributions of the Lauraceae [even] appear to dictate…” the movement of

the quetzal (Ibid). They are the gardeners that distribute seeds and aid the birth of new generations of plants and animals. Because quetzals only thrive in niche, healthy climates and environments, they are a great indicator species, meaning that their presence (or absence) can provide valuable information indicative of the overall health of the local ecosystem. Along with the quetzal’s biological importance, the quetzal holds a significant spiritual presence. The resplendent quetzal is seen as many things: a symbol of goodness and light, as precious, and sacred (American Bird Conservancy, 2023).

The Quetzalcoatl, for example, is the “plumed serpent” God of Mesoamerica, a mythological creature that was inspired by the quetzal (Figure 2). The Quetzalcoatl was said to be involved in the creation of the world (Ibid). Mesoamerican rulers made extravagant headdresses from the feathers of these sacred birds in the hopes that it would connect them with the gods. Many Aztecs and Mayans viewed the quetzal as a “god of the air” (Ibid.). Quetzals signified freedom and wealth, and their feathers were as valuable as money (Ibid). Even today, Guatemala claims the Quetzal as its national bird, and has used its name for their currency (Ibid). Many people in Costa Rica rely on the rainforest and these beautiful birds for their livelihood. In fact, over thirty percent of tourism in Monteverde is to see bellbirds and quetzals (Cruz). Costa Rica works hard to protect the habitats of these beautiful creatures through reforestation projects spread throughout the country. But it wasn’t always this way. Costa Ricans rely heavily on cattle farming as a primary means of income. This requires clearing land and cutting down the rainforest to create fields for grazing. Many cloud forest habitats, full of amazing wildlife and biodiversity, were destroyed, leaving most feeling hopeless about conservation efforts and the national reforestation project. However, one thing I’ve noticed most about Costa Ricans is the value they place in community. In Costa Rica, the people I met had a genuine love and concern for others, as much as they do

sssssSPRIsdNG 2023 | 15 | NATURE

SPRING

©Designpics / Adobe Stock

for their land; they respect the land, and they understand its value and its importance. Costa Rican families have grown up relying on their land for food, water, culture, and even ecotourism. Their land is more than grass and trees, it’s their livelihood. I believe this fueled the new conservation mentality leading the country to focus more on ecotourism as a way of income. The community was able to come together and, eventually, the area covered by rainforest doubled in just forty years (Cruz). Their conservation efforts were vital, but the quetzal still faces many problems. Climate change continues to create obstacles for many animals all around the world, quetzals included. The quetzal comfortably lives in cooler climates, between 5,000 and 9,000 feet above sea level (Skutch, 215). However, as climates are starting to warm, quetzals are forced to migrate to higher elevations in order to find these cooler climates. This migration introduces new problems, such as new predators and diseases, and it further begs the question: what will happen once the quetzals reach the top? Climate change puts us at risk of losing this species forever, along with many other animals who depend on cooler climates for survival. Climate change is a complicated problem that cannot be fixed overnight. One struggle that conservationists face is the pessimistic view most people hold towards conservation efforts. People believe that humans have already dug a hole so deep that we can never make a substantial impact on our environment and in our communities. I believe that this is false. The future of our world is in the hands of people willing to care. Conservation education is vital in combating climate change and other environmental factors. The hardest part about conservation is getting people to care and to feel like they are creating a meaningful impact. There was this story that I heard back in Costa Rica. It’s about this fire that breaks out in the forest and this jaguar sees a hummingbird flying again and again, from the river to the fire. The jaguar asked the hummingbird what he was doing, and he replied that he was getting water from the river to put out the fire. The Jaguar was in awe of how the little hummingbird, not able to carry much water at all, was still doing his part to help with the fire. This story shows that no action is too small. Everything we do makes an impact in this world. “People protect what they love, and love what they know well” (Cruz). Passion for life and the world, and truly being in love with nature is how real conservation happens. Nature impacts everything around us; we all work together. Beauty is what draws people into caring, but people cement their interest due to the way nature makes them feel. There is a connection between humankind and nature, and that is worth fighting for. To not only help save the quetzals but to aid in reforestation, and further conservation in Costa Rica, people can donate to organizations creating real change. The Monteverde

institute is an organization that provides conservation and sustainability education, while also conducting research to further understand our environment so we can learn how to better protect it. Reserves are also a vital piece in the conservation process. In Costa Rica, there are many reservations that are actively protecting land from commercial use and working to maintain the forest land they have. Donating to reserves such as the Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve helps the organization conduct research and maintain trails. It is places like these that spark curiosity and love for amazing animals like the quetzal. They instill a passion to create change. It’s not too late to fight climate change and save the environment that we love so dearly.

References:

Cruz, Daniela. “Ocotea Trees.” Monteverde Institute. Monteverde Institute, 11 June 2023, Monteverde, Costa Rica.

“Resplendent Quetzal.” American Bird Conservancy, 3 Feb. 2023, abcbirds.org/bird/resplendent-quetzal/.

Skutch, Alexander F. “Life History of the Quetzal.” The Condor, vol. 46, no. 5, 1944, pp. 213–235, https://doi.org/10.2307/1364045.

Wheelwright, Nathaniel T. “Fruits and the Ecology of Resplendent Quetzals.” The Auk, vol. 100, no. 2, 1983, pp. 286–301, https://doi. org/10.1093/auk/100.2.286.

Pictures:

“Quetzalcoatl Mexican Aztec.” Freepik, https://www.freepik.com/premiumvector/quetzalcoatl-mexican-aztec_20050272.htm. Accessed 5 July 2023.

“REFORESTATION PROGRAM AT THE MONTEVERDE INSTITUTE.” Monteverde Institute, 30 Oct. 2018, http://monteverde-institute-blog.org/ environmental/reforestation-program-at-the-mvi. Accessed 5 July 2023.

Shuttershock. “Flying Resplendent Quetzal.” Insight Guide, 15 Aug. 2013, https://www.insightguides.com/inspire-me/blog/cute-bird-theresplendent-quetzal-and-viewing-wildlife-in-costa-rica. Accessed 5 July 2023.

20 | HENDRIX SCIENTIFIC

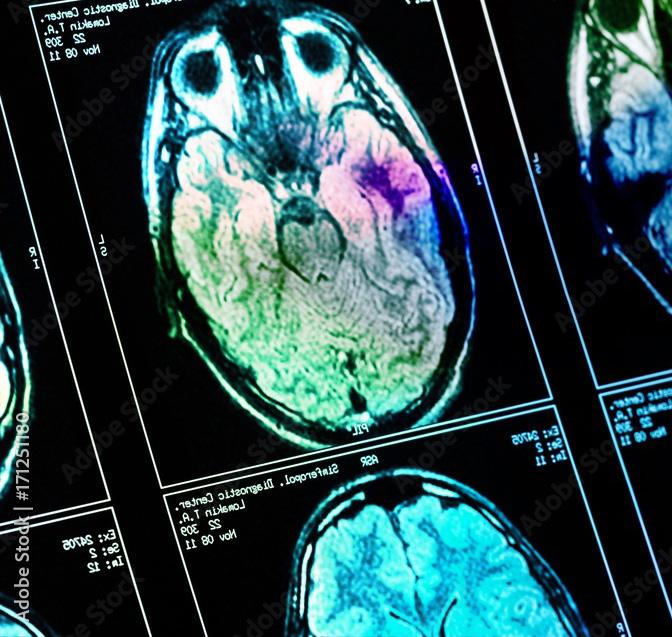

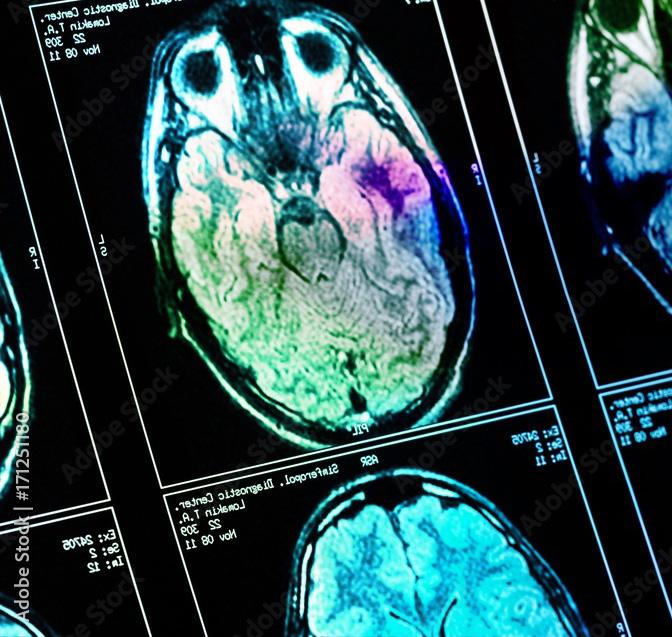

JITTERBUG: A LOOK AT THREE SUPERFICIALLY SIMILAR CAUSES OF MOVEMENT DISORDER

EDEN ROBBINS

Ry When one hears the word “movement disorder,” they might think about someone in a wheelchair, or otherwise lacking the ability to move some part of their body. Despite what the name might sound like, movement disorders actually refer to something more complicated: either the presence of an excess of unintended motion or the slowing of intended motion (Mayo Clinic, 2022). Human beings naturally lose some control of their fine motor skills when in a state of heightened emotion (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke); however, there are several less benign causes of disordered movement. One could write a whole book simply filled with descriptions of different movement disorders, but a few of the most noteworthy ones are Huntington’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and essential tremor. The first two are diseases you may already be familiar with: Parkinson’s is not uncommon, and Huntington’s is among the more famous deadly genetic disorders. The third one, essential tremor, despite its lack of notoriety, is the single most common movement disorder (Anwar et al., 2014). If you were to put these disorders side by side, you could be forgiven for thinking they were all one disease at varying levels of severity: three diseases involving a progressive deterioration of motor function with an impairment of mental processes, primarily seen in older populations and with a genetic component. Huntington’s disease is widely known to be lethal, essential tremor may appear to be naught but an inconvenience, and Parkinson’s disease may seem to be somewhere in the middle. Of course, things are hardly so simple, and the three disorders have no actual relation to each other in genetic cause, mechanism of degeneration, or any other pathological category beyond what has already been outlined. Let’s take a look at these diseases and see what makes them tick

Huntington’s Disease

Huntington’s disease is what is known as an autosomal dominant genetic disorder (Jimenez-Sanchez et al., 2017). This occurs due to a mutation in one of the 22 sets of chromosomes that do not determine sex (the autosomes), and that only one chromosome out of the pair needs to have the mutation for symptoms to occur. It is the only one of the three conditions that has a confirmed place of mutation on a gene. Essentially, the gene that is supposed to code for a vital neuron supporting protein (both named Huntingtin after its role in the development of the disease) is too long to be properly made by the body. More specifically, there is a portion of the gene that is supposed to have a specific number of repeats, but the mutation results in far too many. The resulting Huntingtin protein cannot be properly used by the body. The age of onset of the disorder is influenced in part by how many extra repeats of the gene fragment there are, with more repeats resulting in an earlier start of the disease (Jimenez-Sanchez et al., 2017). With the mutation, there isn’t enough healthy protein, directly resulting in neurodegeneration. The disease starts to take effect with the onset of what is known as “chorea,” involuntary jerking motions. In Huntington’s disease, these motions start in the fingers, toes, and face, and move inwards towards the torso as the condition progresses (Roos, 2010). As time goes on, voluntary motion becomes slowed, as well as more effortful, and the muscles become more rigid. Eventually, the patient loses the ability to take care of themselves as even walking becomes perilous in the later stages of the disease. In addition to the physical symptoms, mental ones are commonly seen as well; cognitive decline can even precede the first noticeable bouts of chorea. Depression and anxiety are also common, as is irritability, and some cases develop symptomology similar to that of

SPRING 2024 | 21 | MEDICINE

schizophrenia, with notable auditory hallucinations and paranoid ideation. Symptoms typically start between the ages of 30 to 50, but in extreme cases can begin before the age of 20. The disease typically continues to progress for around 20 years before death, and there is no known cure (Roos, 2010)

Parkinson’s Disease

Parkinson’s disease has no known genes confirmed to be responsible for its development, but it is thought to be caused primarily by the degradation of dopaminergic nerves (nerves that use dopamine as their neurotransmitter of choice) in a portion of the midbrain known as the substantia nigra (Dauer et al., 2003). Most cases are sporadic, meaning that the affected have no close relatives with the disease, but some cases are inherited, suggesting that there is some genetic component. Another main hypothesis is that, particularly in sporadic cases, degeneration may be the result of an environmental toxin (Dauer et al., 2003).

In many ways, Parkinson’s disease looks a lot like Huntington’s disease. They both share the slowing and deterioration of voluntary movement as they progress, and result in increased muscle rigidity. However, rather than chorea, Parkinson’s disease features what is known as a “resting tremor” (Beitz, 2014). While chorea describes random jerking motions, a resting tremor is a rhythmic involuntary movement that mainly happens while the affected area isn’t being voluntarily moved or resisting gravity (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke). Much like Huntington’s, Parkinson’s causes walking to become harder as symptoms become more severe and the patient begins to have trouble maintaining posture (Beitz, 2014). Furthermore, cognitive decline, depression, and anxiety are common. Symptoms of psychosis are not infrequent, although in Parkinson’s the most common manifestations of such are visual hallucinations. Sleep issues are nearly unanimous among sufferers. Perhaps most notably, unlike Huntington’s disease, Parkinson’s isn’t a lethal disorder, although some symptoms do raise the risk of dying of other causes, such as falling, or pneumonia caused by the inhalation of food or drink. Parkinson’s doesn’t reach as severe a state as Huntington’s in the vast majority of cases, and symptoms usually respond well to medication and specialized therapies. The typical age of onset is between 50 and 70 years (Beitz, 2014).

Essential Tremor

Essential tremor is believed to be caused by degeneration of the cerebellum (the part of the brain responsible for fine motor control.) There are a few theories as to what causes this degradation, such as

alkaloid exposure, the deficiency of a neurotransmitter known as GABA, or a lack of certain synaptic fibers. There is uncertainty if the cerebellum is even involved at all by some researchers (Pan et al., 2022). The consensus is these are all potential causes, and that distinct causes are associated with the different symptom profiles. A lot is still unknown. An interesting note, however, is that people who have family histories of the disease typically develop it earlier in life than those who do not, further indicating that there are many possible causes of the disease (Pan et al., 2022) Huntington’s disease is characterized by chorea, Parkinson’s disease is characterized by resting tremor, and essential tremor is characterized by a third category of involuntary movement called “action tremor”. Action tremor is the opposite of resting tremor: it is an involuntary rhythmic movement that occurs during voluntary motion (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke). This tremor is most commonly found in the hands, but as the disease progresses, it can spread to the arms, head, vocal cords, and legs. Formally, essential tremor is defined as persistent action tremor with no other symptoms, but as the disease progresses, it is common to develop symptoms such as a loss of coordination and a set of symptoms somewhat confusingly called parkinsonism (Pan et al., 2022). Parkinsonism is simply the presence of slowed movement, tremors, and stiffness similar to that found in Parkinson’s disease (Shrimanker et al., 2022). The term’s similar name to Parkinson’s disease and commonality in essential tremor often results in further confusion between the two. Much like both Huntington’s and Parkinson’s disease, essential tremor is known to cause cognitive decline, particularly amongst people with an older age of onset. Essential tremor also confers an increased risk of depression and anxiety amongst sufferers of all ages, even before physical symptoms manifest; however, it is not known to be correlated with psychosis (Janicki et al., 2013). As the disease progresses and the action tremor becomes more severe, it can, in some cases, cause significant disability. Medicine can be used to help quell the tremor in earlier and milder cases, and surgical interventions can be very effective in more advanced ones (Pan et al., 2022). In both familial and sporadic cases, the age of onset is typically after the age of 40. However, the familial variety develops earlier in a little under half of all cases (Louis, 2019).

Conclusion

Huntington’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and essential tremor all appear very similar to the untrained eye. They’re all progressive neurodegenerative conditions featuring uncontrolled motion and psychiatric

22 | HENDRIX SCIENTIFIC

symptoms. Although they are distinct from one another, real life can blur the boundaries between the diseases. The symptom profiles of each are often more complicated than the standout symptoms listed above, and any of these conditions can occur alongside the other. Parkinson’s disease and essential tremor in particular can be tough to differentiate, as they have no definitive test like Huntington’s disease. Despite this haziness, there is a great deal of difference between what can be done for these diseases as well as the expected outcomes. That is why it is so important to be able to distinguish between these three conditions; they can affect anyone, and everyone is affected differently. If you develop one of these disorders, or if someone you love does, you will want to know what to expect so you can live the rest of your life as happily and healthily as possible, however jittery it may be.

References:

Ahmed A, Patrick S. Tremors, Cleveland Clinic Center for Continuing Education, July 2014, https://www.clevelandclinicmeded.com/ medicalpubs/diseasemanagement/neurology/tremors/.

Beitz JM. Parkinson’s disease: a review. Front Biosci (Schol Ed). 2014 Jan 1;6(1):65-74. doi: 10.2741/s415. PMID: 24389262.

Dauer W, Przedborski S. Parkinson’s disease: mechanisms and models. Neuron. 2003 Sep 11;39(6):889-909. doi: 10.1016/s08966273(03)00568-3. PMID: 12971891.

Janicki SC, Cosentino S, Louis ED. The cognitive side of essential tremor: what are the therapeutic implications? Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2013 Nov;6(6):353-68. doi: 10.1177/1756285613489591. PMID: 24228071; PMCID: PMC3825113.

Jimenez-Sanchez M, Licitra F, Underwood BR, Rubinsztein DC. Huntington’s Disease: Mechanisms of Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Strategies. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2017 Jul 5;7(7):a024240. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a024240. PMID: 27940602; PMCID: PMC5495055

Louis ED. The Roles of Age and Aging in Essential Tremor: An Epidemiological Perspective. Neuroepidemiology. 2019;52(1-2):111-118. doi: 10.1159/000492831. Epub 2019 Jan 9. PMID: 30625472.

“Movement Disorders.” Mayo Clinic, Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 24 May 2022, https://www.mayoclinic.org/ diseases-conditions/movement- disorders/symptoms-causes/syc20363893#:~:text=The%20term%20movement%20disorders%20 refers,Ataxia.

Pan MK, Kuo SH. Essential tremor: Clinical perspectives and pathophysiology. J Neurol Sci. 2022 Apr 15;435:120198. doi: 10.1016/j. jns.2022.120198. Epub 2022 Feb 23. PMID: 35299120.

Roos RA. Huntington’s disease: a clinical review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010 Dec 20;5:40. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-5-40. PMID: 21171977; PMCID: PMC3022767.

Shrimanker I, Tadi P, Sánchez-Manso JC. Parkinsonism. [Updated 2022 Jun 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/ NBK542224/

SPRING 2024 | 23

1600 Washington Avenue Conway, AR 72032