Comprehensive and collaborative support for the disability community demands partnerships, coalitions and alliances.

The Founding Sponsors of HELEN: The Journal of Human Exceptionality are making it possible to provide valuable information to healthcare professionals, those living with disabilities, their families, and caregivers.

Steve Perlman, DDS, MScD, DHL (Hon.)

Steve Perlman, DDS, MScD, DHL (Hon.)

For information about becoming a Founding Sponsor of HELEN, please contact Vanessa Ira at vira@helenjournal.org.

To be disability competent, it starts by practices knowing what disability competence means, has actively made adjustments, and can show the improvements.

A discussion delving into the functions of sleep and why we need it.

By Samantha DiSalvo

By Stephanie Meredith By Sherry BurchardBy Ley Linder, MA, M.Ed, BCBA

Helen: The Journal of Human Exceptionality is where people with disabilities, families, clinicians, and caregivers intersect for inclusive health.

Editor in Chief

Senior Managing Editor

Senior Editor, Special Projects Publisher

Art Director

Rick Rader, MD, FAAIDD, FAADM

Vanessa B. Ira

Steve Perlman, DDS, MScD, DHL (Hon)

Allen Wong, DDS, EdD, DABSCD Alyse Knudsen

CONNECT WITH US! @HelenJournal_

American Academy of Developmental Medicine & Dentistry 3 Forester Avenue, #22 Warwick, NY 10990

All rights reserved. Copyright © 2022

American Academy of Developmental Medicine & Dentistry

Helen: The Journal of Human Exceptionality neither endorses nor guarantees any of the products or services mentioned in the publication. We strongly recommend that readers thoroughly investigate the companies and products or services being considered for purchase, and, where appropriate, we encourage them to consult a physician or other credentialed health professional before use and purchase.

HELEN’s Editorial Advisory Board is collaboration of distinguished health care professionals, advocates, policy makers, and educators. Each member brings knowledge, a unique perspective and valuable input to HELEN.

Marc Bernard Ackerman, DMD, MBA, FACD

Director of Orthodontics, Boston Children’s Hospital; Adjunct Assistant Professor, University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine, PA

Jean F. Campbell Principal, JF Campbell Consultants; Founding Board Member, Professional Patient Advocates in Life Sciences (PPALS)

Roberta Carlin, MA, MS, JD Executive Director, American Association on Health and Disability, Rockville, MD

Renee Dease

Specialist & Coordinator, Healthy Athletes Health Programs at Special Olympics International

Steven M. Eidelman

H. Rodney Sharp Professor of Human Services Policy & Leadership; Faculty Director, The National Leadership Consortium on Developmental Disabilities, University of Delaware

David Ervin, BSc, MA, FAAIDD Chief Executive Officer, MAKOM, Rockville, MD

David Fray, DDS, MBA

Professor, Department of General Practice and Dental Public Health, University of Texas School of Dentistry, Houston, TX Rick Guidotti

Founder and Director of Positive Exposure, New York, NY

Matthew Holder, MD, MBA, FAADM

CEO, Kramer Davis Health; Co-founder, AADMD; Co-founder, ABDM; Co-founder, Lee Specialty Clinic

Emily Johnson, MD

Medical Director, Developmental Disabilities Health Center, Peak Vista Community Health Centers, Colorado Springs, CO

Seth Keller, MD

Neurologist, Co-president, National Task Group on Intellectual Disabilities and Dementia Practices

Gary Liguori, PhD, FACSM Dean, College of Health Sciences, URI Academic Health Collaborative, Kingston, RI

Joseph M. Macbeth

President/Chief Executive Officer, National Alliance for Direct Support Professionals, Inc.

Susan L. Parish, PhD, MSW

Dean and Professor, College of Health Professions, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA

Hoangmai H. Pham, MD, MPH President and CEO, Institute for Exceptional Care

Hon. Neil Romano

Former Assistant Secretary, United States, Department of Labor, Office of Disability Employment Policy, Chairman Emeritus, National Council on Disability, President, TRG-16

Vincent Siasoco, MD, MBA

Assistant Professor, Albert Einstein College of Medicine; Director of Primary Care, Rose F. Kennedy CERC, Montefiore; Med Director, ADAPT Community Network, New York, N.Y.

JoAnn Simons, MSW

Chief Executive Officer, The Northeast Arc, Danvers, MA

Michael Ashley Stein, JD, PhD

Co-founder & Executive Director, Harvard Law School Project on Disability, Cambridge, MA

Justin Steinberg

Special Olympics Northern California Athlete Member, AADMD Board of Directors

Stephen B. Sulkes, MD

Pediatrician, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY

Carl Tyler, MD

Gerontologist, Research Director, Lakewood Family Health Center, Cleveland Clinic, OH

Barbie Vartanian

Parent Advocate; Director, Oral Health Advocacy & Policy Initiatives NYU Executive Committee, Project Accessible Oral Health

H. Barry Waldman, DDS

State University of New York Distinguished Teaching Professor, School of Dental Medicine, Stony Brook University, NY

Dina Zuckerberg Director of Family Programs, MyFace, New York, NY

Helen: The Journal of Exceptionality is proud to be endorsed by the nation’s leading organizations that advocate for people with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (IDD).

To assist in reforming the current system of healthcare so that no person with IDD is left without access to quality health services.

To prepare clinicians to face the unique challenges in caring for people with IDD.

To provide curriculum to newly established IDD training programs in professional schools across the nation.

To increase the body and quality of patient-centered research regarding those with IDD and to involve parents and caregivers in this process.

To create a forum in which healthcare professionals, families and caregivers may exchange experiences and ideas with regard to caring for patients with IDD.

To disseminate specialized information to families in language that is easy to understand.

To establish alliances between visionary advocacy and healthcare organizations for the primary purpose of achieving better healthcare.

It is the purpose of the American Academy of Developmental Dentistry (AADD) to establish postdoctoral curriculum standards for training dental clinicians in the care of patients with IDD, to establish clinical and didactic training materials and programs to promulgate these standards, and through its certifying entity – the American Board of Developmental Dentistry – to grant board-certification to those dentists who have successfully completed these training programs.

The American Academy of Developmental Medicine (AADM) is a medical society dedicated to addressing the complex medical needs of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities across the lifespan. It incorporates clinician training and awareness, teaching, advocacy, research, board certification, health equity, interdisciplinary collaboration, inclusive care delivery models and shared decision making.

AAHD is dedicated to ensuring health equity for children and adults with disabilities through policy, research, education and dissemination at the federal, state and community level.

AAHD strives to advance health promotion and wellness initiatives for people with disabilities.

AAHD’s goal are to reduce health disparities between people with disabilities and the general population, and to support full community inclusion and accessibility.

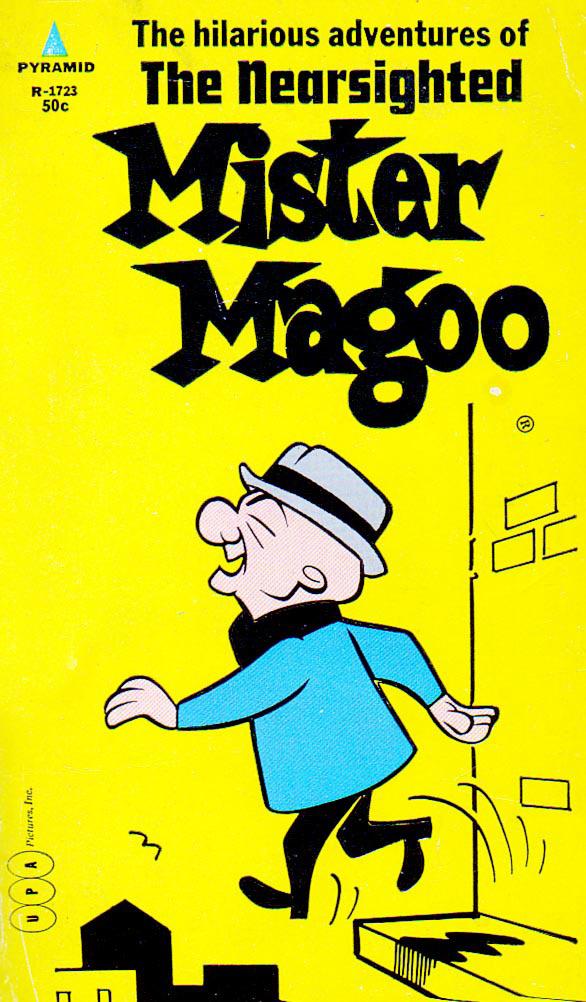

Disabilities Are Disabling.

This vital lesson was demonstrated and evidenced by Mr. Magoo.

Short Film three times and received the award twice. TV Guide ranked Mr. Magoo number 29 on its “50 Greatest Cartoon Characters of All time” list.

Without apologies I confess I grew up reading comic books and watching cartoons. Our favorite childhood cartoon characters didn’t just entertain us on Saturday mornings, they taught us valuable life lessons.

Kristen Sollee in Bustle points out “Ten Life Lessons We’ve Learned From Cartoons”: Conflict is A Given. Cartoon Clothes Aren’t Like Real World Clothes. Your Work Attitude Matters. Successful Relationships Aren’t Easy. Rejection And Failure Are a Part of Life. Caring For Nature Is Important. Our Reality Isn’t Cartoon Reality. Villains Aren’t Always Who You Think. Success Requires Work and Pizza Rules.

While I think she nailed it, I would add another lesson to the list. Not All

The Wikipedia reference to Mr. Magoo sets the stage for the lesson. Mr. Magoo (known by his full name, J. Quincy Magoo) is a fictional cartoon character created at the UPA animation studio in 1949. Voiced by Jim Backus, Mr. Magoo is an elderly, wealthy, short-statured retiree who gets into a series of comical situations as a result of his extreme nearsightedness, compounded by his stubborn refusal to admit the problem. However, through uncanny streaks of luck, the situation always seems to work itself out for him, leaving him no worse than before. Bystanders consequently tend to think that he is a lunatic, rather than just being nearsighted.

Mr. Magoo was no slouch. Mr. Magoo episodes were nominated for the Academy Award for Best Animated

Following his escapades which often brought him close to disaster, his ending catchphrase was “Oh Magoo, you’ve done it again.”

The tribulations of Mr. Magoo remind me of the immortal words of famed baseball player Satchel Paige. Satchel played in both Negro Baseball and Major League Baseball. He claimed they were never able to locate his birth certificate and was unsure of his birthday. ‘’I don’t know how old I am because a goat ate the Bible that had my birth certificate in it.

The goat lived to be twenty-seven.” This situation prompted him to ponder the significance of age. “How old would you be if you didn’t know how old you are?”

And it’s a point well taken.

It reflects back to Mr. Magoo and

“If you didn’t think you had a disability, could you be considered being disabled?”

“

the

of

begs the question, “If you didn’t think you had a disability, could you be considered being disabled?” And that is exactly where we find Mr. Magoo and how he endeared himself to others. Of course, he was confused, frustrated, and distanced himself from others as well.

Without him knowing it, Mr. Magoo has had a life changing impact on one of our country’s most respected disability advocates. Catherine J. Kudlick is a Professor of History and director of the Paul. K. Longmore

writing in the Boston Globe, “The National Federal of the Blind adopted a resolution slamming Magoo as offensive to the visually impaired. The Federation’s chairman berated Disney for thinking “it’s funny to watch an ill-tempered and incompetent blind man stumble into things and misunderstand his surroundings.”

Disney fought back and moved forward with the film. As a concession, they added a message to the end of the film. “The preceding film is not intended as an accurate portray of blindness or poor eyesight. Blindness or poor eyesight does not imply an impairment of one’s ability to be employed in a wide range of jobs, raise a family, perform important civic duties, or engage in a well-rounded life. All people with disabilities deserve a fair chance to live and work without impeded by prejudice.”

potential for damage to a child’s developing self-esteem is very real, and it’s a rare parent indeed who doesn’t agonize with and for the child when – not if, but when – such incidents occur.”

If Magoo served and strived to educate people about the need to respect, understand and support people with visual impairment, or any other disability, I would certainly consider him worthy to become a member of the HELEN Advisory Board. But until we see that in revised and future episodes, we will continue to say, “Oh Magoo, you’ve done it again.”

Alone we can do so little; together we can do so much.

Institute on Disability at San Francisco State University. The disability field has been shaped by her essay “Disability History: Why We Need Another ‘Other’” Kudlick has also published personal thought-pieces “Black Bike, White Cane: Timely Confessions of a Special Self.”

Being a child with a disability (vision impairment) proved to be challenging for Kudlick. She described growing up with cartoons, such as Mr. Magoo. “Many know Mr. Magoo to be about an elderly man, who had nearsightedness. This cartoon mocks the disability of visual impairment when Mr. Magoo would walk off cliffs and portray him as a person who could not care for himself. In regards, to this story, I knew I didn’t want to be that person, just no way.” It’s evident that she did not become a Ms. Magoo.

In 1997, the Disney corporation considered reviving Mr. Magoo as a live action movie. Disney did not understand the power of the disability community. According to Jeff Jacoby

Bryant Gumbel, a news announcer at the time remarked, “These days, no matter what the joke may be, it is harder and harder to make it to the punch line without offending someone. All of which has left us wondering about how thick skinned the society would become.”

Wonder if Gumbel suffered from lichenification and hyperkeratosis if he would watch cartoons ridiculing thickskinned people.

At that time, the newsletter of the Colorado Parents of Blind Children published an editorial that was in my opinion a clear vision. “By far one of the most painful tasks of a parent of a blind child is that of trying to help the child cope with others – especially other children’s – attitudes about their blindness. There isn’t a blind child –including and sometimes especially those with partial vision – who hasn’t experienced some level of teasing about their eyes and vision. Sometimes it is relatively mild, arising out of ignorance and thoughtlessness. But it can too often turn into painfully cruel teasing and taunting. But whether thoughtless, or deliberately cruel, the

HELEN: The Journal of Human Exceptionality pays tribute to Helen Keller. Ms. Keller is perhaps the most iconic disability rights advocate and an example of how an individual with complex disabilities found and used her stamina, perseverance, resilience and determination to accomplish great things.

Helen personifies the spirit, mission and vision of The Journal of Human Exceptionality. Her remarkable life is a reflection of her determination; she inspired us with her words, “What I’m looking for is not out there, it is in me.”

This quote from T.E. Lawrence implies that nothing is inevitable, life consists of choices, and how the individual can make an impact on his/her destiny. The disability community continues to reinforce and remind me of this; hence the name for my monthly musings. - Dr. Rick Rader

Lois Curtis was one of two people who sued for their rights in an important disability rights case called Olmstead v. L.C. She recently died at age 55.

As a child, Lois Curtis was put in an institution. Later in her life, she remembered that she used to pray at night to get out of the institution. As a young adult, Lois started calling an organization called Atlanta Legal Aid. She asked Atlanta Legal Aid to help her get out of the institution and move into the community. Atlanta Legal Aid decided to work with Lois. They helped her and another woman, Elaine Wilson, sue for their rights. The case went all the way to the Supreme Court. In 1999, the Supreme Court decided that the Americans with Disabilities Act gave disabled people the right to receive services in the community, not just in an institution.

After getting out of the institution, Lois eventually moved to her own home in Atlanta. Her community loved her, and she made beautiful art. Lois used a kind of supported decision-making called a “microboard.” This was a small group of people who had regular meetings to talk about Lois’ life. They helped make sure she had what she needed and achieved her goals. Lois’ microboard helped her get a self-directed services waiver from Medicaid. They also helped her show her artwork in galleries. In 2011, Lois visited the White House for a celebration of the anniversary of Olmstead. In 2015, a friend asked Lois, “What do you wish for all the people you’ve helped move out of the institution to live in their communities?”

Lois answered: “I hope they live long lives and have their own place. I hope they make money. I hope they learn every day. I hope they meet new people, celebrate their birthdays, write letters, clean up, go to friends’ houses and drink coffee. I hope they have a good breakfast every day, call people on the phone, feel safe.”

Because of Lois, people with disabilities have the right to receive services in the community. The Olmstead decision has led the government to make more opportunities for people with disabilities to get services outside of institutions. Advocates and the government use the Olmstead decision to fight for disabled students’ rights to learn in the same classroom as non-disabled students. Advocates and the government use Olmstead to fight for disabled workers’ rights to work in the same workplace as non-disabled workers, and earn a competitive wage.

Autistic Self Advocacy Network (ASAN) remembers Lois Curtis’ amazing life, and honors her in their work by:

• Working to make sure that everyone has the rights that the Olmstead decision promises them.

• Making sure that more people can use supported decision-making and alternatives to guardianship.

• Following the leadership of Black disabled advocates and advocates with intellectual disabilities.

Lois Curtis was given no option but to live in an institution, but she refused to accept that and created a different path to follow - for herself and for many other people with disabilities.

Rest in Power, Lois Curtis.

Because of Lois, people with disabilities have the right to receive services in the community.

“Photo courtesy of Robin Rayne/ZUMA

(From Military OneSource)

Family-to-Family Health Information Centers are nonprofit organizations familiar with the issues facing families with special needs. In addition to the services for military families that are available here at Military OneSource or at your local family support center, Family-to-Family Health Information Centers can connect you to resources that can provide and finance health care for your children, help locate assistance, and explain legislation. Each center has staff — many are parents of children with special needs — who understand available services and programs.

Your local Family-to-Family center can help you find answers to a variety of health care issues. Along with other services, center staff can help you:

• Learn eligibility requirements for Medicaid

• Find answers to questions about Social Security and

Supplemental Security Income

• Write a health care plan for teachers and therapists

• Locate resources to pay for medications

• Find support groups

• Understand Title V and other programs that can help your family member

• Transition between insurance plans

Tap into useful resources

Get the help you need from your Family-to-Family center through:

• Support and referrals by telephone, email or in-person contact

• Training workshops

• Helpful websites

• Newsletters and other publications

• Guidance on health programs and policy

• Evaluation and outcome assessments

Family-to-Family Health Information Centers can help you navigate the waters of health care and find the personalized tools you need for your family. Learn more about Family-to-Family Information Centers and find a link to locate the one in your state at familyvoices.org. For more information on resources for finding access to medical services for families with special needs, read the Exceptional Family Member Program fact sheet on Medicaid and Medicare (https://www.militaryonesource.mil/ products/public-benefits-resources-medicaid-and-medicare-fact-sheet-962/).

These were all said to me throughout my clinical rotations when I asked to follow different patients who had an intellectual and/or developmental disability (I/DD). These statements sound harsh when written alone, but I do not believe that these words were ill intentioned. Rather, I believe the problem lies in the system. The system in which medical schools are not required to teach future physicians how best to care for individuals with disabilities; and this often leaves health care professionals hesitant when providing care. In my eyes, these patients were the perfect learning opportunity and yet, I was being discouraged from it. Why was that their gut reaction?

In medical school, we have specific courses dedicated to learning how to communicate with our patients. We learn the right questions to ask to obtain a thorough history. We learn that if a patient has pain, you should go through the “OPQRST” questions to further evaluate it. When was the Onset? What Provokes or Palliates it? What is the Quality of the pain? And so on. But what do we do when our patients do not communicate directly with words? You cannot bring in a translator to help you in these situations. Rather, the physicians themselves must know that there is more to communication than just speaking words. There are communication boards or devices, facial expressions, gestures, and so much more to help you obtain a thorough history. This is not covered in my medical school curriculum, nor most other medical schools around the country. It is this lack of education, lack of knowledge, and ultimately,

the lack of comfort that leads to those statements you read at the beginning of this article.

And it is those same phrases that were the motivation behind one of our recent Einstein American Academy of Developmental Medicine and Dentistry (AADMD) Student Chapter webinars where we focused on improving communication skills amongst future physicians and individuals with I/DD. This was a very special event for me because I was able to bring in two experts on the topic who also happen to be family—my brother Anthony, who has cerebral palsy, and my mom, who is his primary caregiver and retired physical education teacher for children with disabilities.

My brother and I have worked on countless projects together, from the annual Christmas raffle to selling Superbowl boxes, but this past September we added this new project, creating a presentation to teach my fellow medical students. In preparation for this event, we met with Dr. Seth Keller, a board-certified neurologist with years of experience caring for and advocating alongside individuals with I/DD, to help bring this presentation to fruition. Together we brainstormed the main objectives of our presentation, using Anthony’s perspective as a patient, my

“You won’t learn much.”

“It’ll be a difficult patient.”

“There’s not much for you to do or see.”

mother’s perspective as a caregiver, Dr. Keller’s perspective as a physician, and mine as a medical student currently in training. Ultimately, our goal of the presentation was to:

1. Identify the different modes of communication used by individuals with I/DD

2.Discuss diagnostic overshadowing and other bias’ individuals with I/DD often face in the healthcare setting

3.Show ways of implementing the communication strategies discussed in the presentation within the clinical setting

From the very first planning meeting we had, my brother was filled with excitement and extremely motivated to share his story with my classmates. He Facetimed me almost every night to discuss details of the presentation and finalize the major points that he wanted to get across. Anthony, being the computer-wiz that he is, worked to create PowerPoint slides to introduce himself at the beginning of the presentation, recording his programmed screen-reader to read each of the slides out loud. This would not only allow Anthony to introduce himself to the group, but would also highlight the use of communication devices as a form of communication for some individuals.

My mom, my brother, and I continued to meet to discuss the details, and with each meeting, we were able to uncover more and more physician encounters that really highlighted the importance of communication, both the good and the bad. We sifted through countless physician encounters they have had through the years and identified which ones they liked more and then took it a step further to question why those encounters were more positive for Anthony and my mom.

Ultimately, it came down to communication. Physicians who spoke directly to Anthony and did not assume that he does not understand were often ones that provided better care in their eyes. Physicians who asked Anthony

about his life outside of the chief complaint that brought him to the doctor formed a stronger physician-patient relationship with Anthony. Physicians who explained why they were ordering a certain test or what a certain result meant gave Anthony more control and knowledge in his healthcare.

Ultimately, with the help of Dr. Keller, we were able to create a presentation that highlighted all of Anthony and my mom’s experiences within the health care system, with a focus on what future physicians can do better. We incorporated a case presentation and mock interview between Anthony and Dr. Keller to demonstrate key communication strategies in real-time and really allow Anthony to share his perspective of navigating the health care system as an adult with cerebral palsy and intellectual disability.

The statements that I heard on my clinical rotations are unacceptable and there needs to be a change. At Albert Einstein College of Medicine, we are working to change this. Our school is fortunate enough to be members of the Rose F. Kennedy University Centers for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities (UCEDD) which has allowed passionate faculty, such as Dr. Vincent Siasoco and Joanne Siegel, to instill educational lectures and panel presentations into the required medical school curriculum. But there is still more that needs to be done.

During the past two years, the formation of the Einstein student chapter of the AADMD has allowed us to provide extracurricular opportunities for medical students to learn more about treating this underserved population as well as participate in volunteer events to get to know these patients outside of the clinic setting. But there is still more that needs to be done. I hope that this lecture made a small change in how some of my classmates

treat individuals with disabilities, but one lecture is not enough. There needs to be a system-wide change, allowing all physicians-in-training access to the education necessary to provide quality care for patients with I/DD.

Sam DiSalvo is an M.D. Candidate, Class of 2023, Albert Einstein College of Medicine. She is a member of Einstein’s American Academy of Developmental Medicine and Dentistry (AADMD) Student Chapter.

If I had to be a “traditional” behavior analyst (BA), I would be a terrible one. The repetitive nature of discrete trial training would have me reading the Geneva Conventions and conferring with geopolitical legal experts on the lunch break of my first day of employment. I’m not here to say my colleagues who live in the world of tacts and mands, in addition to possessing a fluency in all the types of differential reinforcement, are somehow better (or worse) BAs. To me, they are most impressive and admirable, given the totality and complete command of the science of behavior analysis they possess. However, this is not my experience as a behavior analyst and, to be honest, I have never conducted one minute of discrete trial training. My experience? Here are a few examples from a Tuesday morning in September.

“Ley, do you need to write in behavior programs that the residents can’t carry guns?” After several seconds of audibly laughing and then returning to reviewing a behavior graph, I noticed an awkward silence. This was a question awaiting a response.

“We need to remember the psychiatrist will treat the person, not the level” was my response to an astute direct support professional (DSP) who was inquiring about blood work for a person taking valproic acid who was “tearing the joint down.” This gem of information came from sitting in countless interdisciplinary team meetings led by psychiatrists.

“I told the doctor what you said and tried to show him what you wrote. They said they don’t believe any of that, didn’t order anything, and said it is behavioral. We spent 45 minutes

in the waiting room and 2 minutes in the back.” The only thing missing from this nursing report was mention of the exasperated tone and dismissive eye roll from the doctor. You know the one! What I had prepared was a half-page psychobehavioral summary, along with behavioral data, to illustrate a possible correlation between unintentional weight loss, decrease in appetite, periodic abdominal selfabuse and H-pylori. The information and data were textbook – if one existed about the behavioral presentations of undiagnosed medical conditions in people with ID/RD. This was diagnostic overshadowing and, these days, is an intoxicating fight always worth having.

You may be thinking, “this guy cherry-picked three anecdotes from the last six months to illustrate his

point and grab my attention. Also, why is he telling me this?” Regarding the former, you are not wrong, but these three issues arose in a 90-minute period during a routine site visit in September 2022. To answer the latter, because the most common question I hear is, “You say you’re a behavior analyst, but what do you actually do?!”

What we are trained to do and what we “produce” are behavior assessments and behavior programs, tabulate and analyze data, write progress notes, and ensure fidelity of plan implementation. Peel back a layer and you will find we are educators, as we train staff and caregivers on the “how and why” of behavioral presentations, which is done within the framework of the evidenced-based field of applied behavior analysis. Also, we write – a lot. For a profession fundamentally rooted in interacting with people, I spend a shocking amount of time alone, in front of a computer, typing.

Admittedly, this is not a particularly enchanting and engaging description of a behavior analyst. Perhaps the question is not “what does a behavior analyst do?”, but rather “what makes a behavior analyst?” This question would best be answered by discussing the approach of a BA. What if I said a BA examines a person’s behavior with the notion “everything is possible”? Thus, eliminating the constructs of the setting event-antecedent-behavior-consequence model that inherently limits the scope and reach of effective behavior analysis. Sure, most any BA can tell you a medical condition is a setting event (and/or antecedent) and say, “make sure you always think medical first!” However, what “makes us” is what lies beyond the identification of the components of behavior.

For example, if Jane has a history of urinary tract infections (UTI), a BA can identify and incorporate into the behavior program her individualized UTI symptoms. Through this, the BA can then educate staff/caregivers of what Jane’s UTI symptoms are likely to be and, if observed, could advise to consult a medical professional, present the symptoms (which are likely acute onset behaviors!) in the context of her medical history, and perhaps a urinalysis is completed to rule out a UTI. A non-invasive, relatively quick diagnostic procedure can resolve an acute, treatable medical condition,

medical issue off to a nurse or primary care physician. It is critical for BAs to have a working knowledge of how the treatment strategies and approaches to care of other disciplines impact the lives of the people we serve. Additionally, by incorporating the strategies and expertise of other disciplines into our assessments, programs, and own approach to care, we can increase the desired and positive outcomes of the people we serve. This is what makes a behavior analyst.

while avoiding consult with a psychiatrist because the (possible) behavioral characteristics of the untreated UTI were cognitive changes and increased problem behaviors. Additionally, and perhaps most importantly, the BA could help Jane recognize her UTI symptoms and teach her to communicate she is experiencing discomfort and needs assistance. This is what makes a behavior analyst.

Are we medical doctors? Most of us, no. Are we nurses? SLPs, OTs, PTs, pharmacists? Probably not. The majority of us are simply behavior analysts. What makes us BAs, beyond credentials, is our willingness to be inclusive of all disciplines by recognizing their necessity in helping us be more robust and complete analysts of behavior. In the aforementioned example, it is not enough for BAs to identify the setting event and pass the

I have pondered what being a behavior analyst means to a DSP, other professional disciplines, or to persons who do not work in the ID/RD human services field. The answer, I have come to realize, differs dramatically depending on why a person may have an interaction with a BA. My belief, as a BA, is we have a responsibility to not tell people what we do, but to explain what makes us behavior analysts. For me, this means telling people that a behavior analyst has the ability to examine all behavior (not just maladaptive or aberrant) by incorporating the totality of a person, in an inclusive, interdisciplinary fashion focusing on the individual needs of the person, which is what makes a behavior analyst.

Ley Linder, MA, M.Ed, BCBA is a Board-Certified Behavior Analyst with an academic and professional background in gerontology and applied behavior analysis. Ley’s specialties include behavioral gerontology and the behavioral presentations of neurocognitive disorders, in addition to working with high-management behavioral needs for dually diagnosed persons with intellectual disabilities and mental illness. He is an officer on the Board of Directors for the National Task Group on Intellectual Disabilities and Dementia Practices, works closely with national organizations such as the National Down Syndrome Society, and is the owner/operator of Crescent Behavioral Health Services based in Columbia, SC.

helenjournal.org

“

I hear, “You say you’re a behavior analyst, but what do you actually do?!” What if I said a BA examines a person’s behavior with the notion “everything is possible”?

In this article, we will delve into the possible functions of sleep, and why we sleep. Along the way, we will bring in the history of sleep, including Shakespeare, Proverbs, and Philosophers. We will focus, not only on what clinical sleep experts consider to be sleep’s functions, but humanists as well. Why we sleep remains a mystery, although there are myriad benefits of sleep on our health and well-being.

Let’s start with why we sleep. The short answer – we don’t know! There have been several theories put forth, however.

The first is the Inactivity Theory: animals that can stay still and quiet are less apt to be targets for predators. So, we have evolved to be still at night and quiet. Although one would think being awake, still, and quiet would be better when dealing with tigers and other predators.

In fact, some animals sleep with one half of their brain at a time, such as dolphins, so they can still be awake to ward off predators. So, the Inactivity Theory has fallen out of favor.

The second theory to consider for why we sleep is the Energy Theory. In a setting where food is limited and

needs to be searched for, sleep allows us to reduce our demand for energy, especially when it is harder to search for food, such as at night. However, as any of us who have gotten the munchies at 2 am know, this theory may not relate to modern times. However, since antiquity, sleep has captivated the imaginations of ancient healers, scribes, poets, philosophers and scientists, as evidenced by mythologies, books, plays and art.1 The ancient Egyptians, as far back as 4000 B.C., used sleep as therapy, and had treatment for sleep disorders, such as insomnia. The medicine of ancient Egypt is one of the oldest documented scientific disciplines. The Egyptians were the first to mention the use of opium for the treatment of insomnia. Egyptian medical writings stated that thyme was beneficial in reducing snoring. They also investigated the nature of sleep and dreaming and interpreted dreams using “dream books.” 2

The Ancient Greeks and Romans furthered dream interpretation but in addition, their philosophers and physicians stepped away from the mystical and began to postulate on how sleep and the human body functioned together. The Greco-Roman time period is where you first find documentation of accounts of sleep and dreaming based on reason, rather than mystical knowledge.3 Circa 450 BC, Alcmaeon provided the first reason-based theory of sleep. He believed that lack of circulation (blood carrying veins) to the brain caused sleep, a spell of unconsciousness. Following him, there were multiple other philosophers with non-mystical theories of the process of sleep. However, Aristotle is the first of the Greek philosophers to provide the most comprehensive, written, reason-based account of sleep and dreaming. He wrote three full essays on the subject.4 Aristotle believed the process of sleep commenced with the consumption of food which thickened and

heated the blood. The food, which he termed “solid matter” would then rise to the head where it was cooled by the brain, and the subsequent reverse flow back downward caused a “seizure” in the heart which caused sleep. Wakefulness occurred when digestion was completed with a separation between the “solid matter” and more pure blood. He also rightly believed that sleep kept living beings alive.5 Hippocrates, the most famous physician in Western civilization, wrote that sleep

Shakespeare writes, “Sleep that knits up the ravell’d sleave of care, The death of each day’s life, sore labour’s bath, Balm of hurt minds, great nature’s second course, Chief nourisher in life’s feast.” He is exhorting the restorative nature of sleep.

disturbance was something to take note of and use in the diagnosis and prognosis of disease. In Regimen in Acute Diseases, he offers advice for insomnia, “if sleep should not come, a slow prolonged stroll, with no stops, should be taken.” Throughout his multiple texts he discussed the importance of sleep and even prescribed sleep as a treatment for a variety of conditions, along with diet and exercise.6

In our ever-divided world, we agree on a few things, but most people would agree that sleep is important. Over one-third of adults in the United States report insufficient sleep. However, often, sleep is the first thing that gets sacrificed in order to accomplish all our obligations. In Macbeth,

Which leads us to discuss our favorite theory of “why we sleep,” the Restorative Theory: Sleep “restores” and repairs what is lost in the body when we are awake. Think of sleep as a reset button, similar to restarting our computers so they work better. This restoration can occur for both physical and mental conditions. For example, one theory of how sleep prevents Alzheimer’s disease stems from sleep getting rid of waste products that accumulate in our brains overnight, as described below. We also feel less stressed and more rejuvenated – ready to take on the day – once we have slept.

To summarize, while WHY we sleep is still a mystery, the importance of sleep has become clear. In future articles, we will dive more into how sleep is affected by genes and other factors, and what you can do to make sure you get your best night’s sleep.

This article is included in the upcoming monograph “Sleep and Sleep Disorders in People with Disabilities” published by HELEN: The Journal of Human Exceptionality.

Dr. Althea Shelton’s research and clinical practice is focused on sleep disorders in children and adolescents with neurodevelopmental disorders.

Dr. Beth Malow’s research and clinical practice is focused on sleep in autism across the lifespan, including treatments with behavioral approaches and medications.

“It is a common experience that a problem difficult at night is resolved in the morning after the committee of sleep has worked on it.”

- John Steinbeck

We cannot overstate the importance of sleep. Getting enough sleep makes it easier to prevent and manage disease. Too little sleep and poor sleep quality have been associated with severe health outcomes. So, let us briefly delve into some of these health outcomes. In future articles, we will discuss these more in depth.

Poor sleep, and chronic sleep loss, have been linked to heart disease13 and high blood pressure.6 Not sleeping enough hours increased a person’s chances of high blood pressure by 20%.14

As sleep neurologists, problems with memory and focusing are something that we often see, and we work with psychologists to help diagnose these problems. Paying attention is one of the most studied problems.7 The fewer hours that we sleep, the more lapses in attention we have. In addition, research shows that short sleep duration causes problems with our memory, decision making, and processing speed.8 Poor sleep is linked to the buildup in the brain of a chemical called beta amyloid, which results in Alzheimer’s disease.9 Beta-amyloid buildup also occurs in Down syndrome, and has been connected with Alzheimer’s disease symptoms as individuals with Down syndrome age.10

Type 2 diabetes has become an increasingly common chronic condition in the United States. Not getting enough sleep results in a 33% incrveased risk of developing diabetes.14 When people sleep too few hours, they are more likely to eat unhealthy foods.6

Seizures are common in some intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD), such as autism spectrum disorder and Down syndrome, and are more common in those with more severe forms of IDD.11 Seizures have a reciprocal relationship with sleep, with disrupted sleep making seizures more likely. In turn, seizures can disrupt sleep. Treating sleep problems can improve seizure control.12

Sleep and mood have a reciprocal relationship. Mood disorders, such as anxiety, can often make sleep worse, but chronic sleep loss can also worsen mood. Shortened sleep can make depression less likely.16 In children with developmental disabilities, like autism spectrum disorder, sleeping less can go along with depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder.17 The promising news is that it’s possible that depression symptoms may improve with sleeping more.18

Weight gain, including obesity, often results when people are not getting enough sleep, especially young adults.15 With chronic sleep loss, there are changes in leptin and ghrelin which are two hormones that regulate how hungry or satisfied we feel after we have eaten. On the bright side, getting more sleep can help with weight loss.6

1. Borbely A. (1984). Secrets of sleep. New York: Basic Books.

2. Asaad T. (2015) Sleep in Ancient Egypt. In: Chokroverty S., Billiard M. (eds.) Sleep Medicine. Springer, New York, NY.

3. Barbera J. (2008). Sleep and dreaming in Greek and Roman philosophy. Sleep Med.;9(8):906–10.

4. Gallop D. (1996) Aristotle on sleep and dreams. Warminster: Aris and Phillips.

5. Barbera J. (2015) The Greco-Roman Period. In: Chokroverty S., Billiard M. (eds.) Sleep Medicine. Springer, New York, NY.

6. Grandner MA. (2017) Sleep, Health, and Society. Sleep Med Clin.; 12(1):1-22.

7. Goel N, Rao H, Durmer JS, et al. (2009) Neurocognitive consequences of sleep deprivation. Semin Neurol ;29(4):320–39.

8. Winer JR, Mander BA, Kumar S, Reed M, Baker SL, Jagust WJ, Walker MP. (2020). Sleep Disturbance Forecasts β-Amyloid Accumulation across Subsequent Years. Curr Biol. 2;30(21):4291-4298.

9. Carmona-Iragui M, Videla L, Lleó A, Fortea J. (2019). Down syndrome, Alzheimer disease, and cerebral amyloid angiopathy: The complex triangle of brain amyloidosis. Dev Neurobiol. 79(7):716-737.

10. Devinsky, O., Asato, M., Camfield, P., Geller, E., Kanner, A. M., Keller, S., Kerr, M., Kossoff, E. H., Lau, H., Kothare, S., Singh, B. K., & Wirrell, E. (2015). Delivery of epilepsy care to adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Neurology, 85(17), 1512–1521.

11. Malow BA. Sleep, epilepsy, and autism. (2004). Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews 10: 122–125.

12. Amagai Y, Ishikawa S, Gotoh T, et al. (2010). Sleep duration and incidence of cardiovascular events in a Japanese population: the Jichi Medical School cohort study. J Epidemiol.;20(2):106-10.

13. Meng L, Zheng Y, Hui R. (2013) The relationship of sleep duration and insomnia to risk of hypertension incidence: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Hypertens Res. 36(11):985-95.

14. Shan Z, Ma H, Xie M, et al. (2015) Sleep duration and risk of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Diabetes Care 38(3):529–37.

15. Grandner MA, Chakravorty S, Perlis ML, et al. (2014). Habitual sleep duration associated with self-reported and objectively determined cardiometabolic risk factors. Sleep Med 15(1):42–50.

16. Liu X (2004). Sleep and adolescent suicidal behavior. Sleep. 27(7:1351–135.

17. Veatch et al. (2017). Shorter sleep duration is associated with social impairment and comorbidities in ASD. Autism Research. 10(7):12211238.

18. Dewald-Kaufmann et al. (2014). The effects of sleep extension and sleep hygiene advice on sleep and depressive symptoms in adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 55(3):273–283.

Getting enough sleep makes it easier to prevent and manage disease.

The Chanda Center for Health has been a staple in the Denver community for the last 17 years. The Center provides integrative therapies and other complementary services to improve health outcomes and reduce health care costs for people with long-term physical disabilities, such as spinal cord injuries, brain injuries, cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis, and spina bifida.

In February 2022, the Chanda Center partnered with the Colorado Academy of Family Physicians to develop a new AAFP-accredited online course designed to fill the knowledge gap for health care providers. The course, “Disability-Competence Curriculum for Healthcare Providers,” funded by the Colorado Health Foundation and developed with many stakeholders in 2020, was designed to provide an indepth look at ways individual health

care professionals, their medical teams, and administrative staff can better serve individuals with disabilities as members within the system of care.

In addition to providing integrative services at The Center, founder Chanda Hinton has been advocating for her community and successfully getting Medicaid to cover acupuncture, massage, and chiropractic care to bring preventative methods for individuals with disabilities to the forefront. However, the fight is long from over. Though some positive change has happened to benefit those with physical disabilities, there is still a stigma around equitable health care for this population, and why it’s important. And that needs to change. Chanda and the Center are actively working to effect change through education, but more importantly on a systematic level to truly make an impact.

In the world of health care, physicians and support staff are required by law (below) to be disability competent. But many health care providers are unaware of what this means exactly and, more important, why it’s necessary. Individuals with physical disabilities are entitled to independently access health care from the parking lot with designated signage, to accessible entrances, and a receptionist that is educated about a patient’s accommodations. Factors that health care providers are required to offer in order to be considered “disability competent” are proper equipment and training, communication skills, accessibility, and more.

To be disability competent, its starts by practices knowing what disability competence means, has actively made adjustments, and can show the

improvements, which demonstrates their understanding around the needs of the community. And while the need for equitable health care grows, so does the health disparity of patients with long-term physical disabilities because of the lack of compliance.

Persons with disabilities are considered a health disparity group, in that they are subject to avoidable inequities in access, and in the quality of, health services. While concerns around transportation, communication, and insurance are contributing factors, the knowledge gap amongst physicians in serving individuals with disabilities is the primary contributor to this inequity. In 2009, a report by the National Council on Disability noted “the absence of professional training on disability competency issues for health practitioners is one of the most significant barriers to preventing people with disabilities from receiving appropriate and effective health care.”

When you look into the face of Chanda Hinton, you see vitality and radiant health; you see a young woman with passion and determination; you see a person of strength and purpose. If you glance down from her face, you will see her wheelchair, and you realize that the goals of the nonprofit organization she founded 17 years ago. You will see that her role is rooted in her own personal story.

Chanda is the Executive Director of the Chanda Center for Health and Chanda Plan Foundation (https://chandacenter. org/who-we-are/), which provides access to holistic, collaborative, access and disability competent healthcare programs to individuals with physical disabilities. In 2009, she led the movement to pass Colorado House Bill 1047, which created the Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) Waiver, offering acupuncture, massage, and chiropractic care through Medicaid to evaluate cost-effectiveness and improve quality of life for persons with spinal cord injuries in the Denver metro area. In 2021, she expanded these services legislatively to other diagnosis and to be a statewide benefit.

In addition to her work (passion), Chanda presents extensively to diverse audiences about wellness and disability. Her previous honors include the 2008 Unsung Hero Award from Mayor Hickenlooper in honor of Denver’s 150th anniversary, 2010 Health & Wellness Award from the Commission for People with Disabilities, 2015 Kathy Vincent award from the Colorado Cross Disability Coalition, 2015 Diversity Award from Mayor Hancock, 2017 Denver Business Journal 2017 40 under 40 honoree, 2019 Linda Andre Lifetime Trailblazer Award from the Colorado Fund for People with Disabilities and 2019 AMTA National Government Relations Activist Award, Colorado Women’s Chamber 2020 Top 25 Powerful Women

In 2022, individuals with disabilities are still facing barriers that prevent access to quality and equitable healthcare. As The Chanda Center for Health set out to share their new curriculum with health care providers, the same dead ends individuals with disabilities advocated for a quarter of a century ago, continue to be dismissed, even now.

Feedback from physicians has varied. Some express not knowing where or not having access to curriculum, in order to comply. One of the reasons behind the creation of the curriculum. Some have completed dismissed the issue and shared responses such as “why does health care need to adjust for this community,” “I don’t have patients who are disabled,” and “why should I care?” Some health care clinics going as far as turning down free education and possible funding for equipment needed to serve people with disabilities. Based on this feedback, Chanda has shifted her focus to systematic change and addressing the issues that continue to create barriers.

Disability competency is currently not, nor has been a core curriculum requirement for academia or continued education for practicing health care professionals. Health care professionals are serving the health care needs of humanity every day with little to no understanding of the structural, or cultural needs of persons with disabilities. People with disabilities are humans too, and yes…

• There is the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), a civil rights law that prohibits discrimination against individuals with disabilities in all areas of public life, including employment, schools, transportation, and all public and private places that are open to the public.

• There is Section 510 of the Rehabilitation Act, which includes a provision to amend the original Rehabilitation Act to “address access to medical diagnostic equipment, including examination tables and chairs, weight scales, x-ray machines and other radiological equipment, and mammography equipment... The standards are to address independent access

to, and use of, equipment by people with disabilities to the maximum extent possible.”

• OSAH has reported that one major source of injury to health care workers is musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs). In 2017, nursing assistants had the second-highest number of cases of MSDs, with an incidence rate more than five times the average for all industries because of proper equipment not being available to perform health care to those with disabilities.

Advocates and lawmakers have made disability competency required by law, but to date, and despite “breaking the law,” some of the largest health care delivery methods and facilities do not offer true disability competent care. Although realistically, who can blame them? There is no state or federal body that officially assesses and enforces them to demonstrate their disability competency. So, as a health care community, we will continue to reinforce to our health care professionals that skirting the law is okay because there is no enforcement, which comes at the disparity of those with disabilities.

The creation of the “Disability-Competence Curriculum for Healthcare Providers” course is just one component aimed at reducing health disparities for individuals with disabilities. However true change needs to start with systematic change—to ensure that physicians are meeting expectations and, more important, patients are receiving the health care they are entitled to, there needs to be:

• Improved guidance on what is determined as disability competent care outside what is currently in law. Health care providers should know

exactly what it is.

• Increased enforcement on guidance and penalized when not in compliance. Just like compliance in other areas, when audited, they will know exactly what is being evaluated. With continued failure to comply, there is no record and no penalizations.

• Increased reimbursement for service to LTSS. In a recent New York Times article, physicians expressed what limited time they have with patients. And providers in our own

experience in some capacity. That time will come, so advocate for your own health care now. If you are a provider that doesn’t want to wait for these system changes, reach out so that we can help you. If you’re a lobbyist on the federal level and want to help make this right, please reach out! If you’re an employer of any national advocate organization or government entity working on this issue, please reach out!

community shared that the complexity and paperwork that accompanies this population is not billable. With the system set up with these barriers for the providers, it only has one place to trickle down… patients with disabilities who need healthcare.

The Chanda Center for health will be advocating locally with potential legislation to make changes in their backyard, but of course this issue is far more expansive and those involved want to ensure that this is being addressed on the federal level. With conversations with the Office of Civil Rights Diversity and Inclusion at HRSA, and the U.S. Justice Department, there is hope for change.

Let’s stop this from happening, together. After all, there is no one individual that is immune to disability. Regardless of our age, color of our skin or sexual orientation, we all will experience disability at some level, whether it be temporary and severe, it will be something that you personally

“Barrie Cohen founded BCPR on three principles: creativity, customization, and collaboration. After years of working for agencies in Philadelphia, Owner and CEO Barrie Cohen saw the overwhelming need for a more attentive public relations firm dedicated to supporting and strengthening a client’s business goals. Unlike larger firms, Barrie has the ability to work one-on-one with clients to not only provide unprecedented, personalized services but to create a comfortable and trusting working relationship.

Always keeping the clients’ best interest in mind, Barrie utilizes her long-standing media relationships, innovative marketing strategies, and professional writing skills to successfully promote and position clients in a variety of industries across the country—and internationally. Her passion for positive publicity and storytelling has created countless opportunities for her clients.

1. Gloria L. Krahn, Deborah Klein Walker, and Rosaly Correa-De-Araujo, 2015. Persons With Disabilities as an Unrecognized Health Disparity Population, American Journal of Public Health 105, S198_S206.

Regardless of our age, color of our skin or sexual orientation, we all will experience disability at some level, whether it be temporary and severe, it will be something that you personally experience in some capacity.

By Stephanie Meredith, MA, Kara Ayers, PhD, Marsha Michie, PhD, Mark W. Leach, JD, MA, and Robert D. Dinerstein, JD

By Stephanie Meredith, MA, Kara Ayers, PhD, Marsha Michie, PhD, Mark W. Leach, JD, MA, and Robert D. Dinerstein, JD

Many high-profile articles over the past 15 years, including Sarah Zhang’s recent Atlantic article, “The Last Children of Down Syndrome” in 2020, have considered the ethical implications of prenatal testing leading to the potential eradication of people with prenatally-diagnosed conditions. The theory was that if the information were presented in a biased manner regarding a historically marginalized population, the outcome could lead to de facto eugenics. Some of the more nuanced arguments weaving together reproductive choice and disability rights asserted the following:

• Patients undergoing prenatal testing should have the opportunity to make reproductive decisions that reflect their own values as was guaranteed under the law during the era of Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey.

Patient Education: We have known for years that many patients say their informational and support needs are not adequately met after receiving prenatal screening results suggesting a possible diagnosis.1 Further, many of these patients experience lasting trauma based on how the information is presented—particularly when they perceive bias against people with disabilities.2 One concern following the Dobbs decision is that in states that limit reproductive rights, lawmakers will need to urgently prioritize funding the provision of support and informa-

likely to perpetuate stereotypes about disabilities, ranging between evangelizing and catastrophizing disability to score political points.3 - Stephanie Meredith, MA, Director of the National Center for Prenatal and Postnatal Resources at the University of Kentucky’s Human Development Institute

The Dobbs decision weakened constitutional protections for people with disabilities to lead self-determined lives.4

• Those decisions should be based on accurate, up-to-date information about those conditions since many preconceptions about disability are broadly based on stigma and outdated stereotypes.

• Medical providers should present the information free from bias. So, how could this new era under the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision, with its accompanying patchwork of reproductive laws across a divided nation, affect these complex ethical arguments and the patients who receive the results of the prenatal tests? Five experts from different disciplines—legal, bioethics, patient education, and disability studies—share their thoughts moving forward.

tion right away for families who learn of a possible prenatal diagnosis to make sure the baby and family have optimal health and life outcomes. Importantly, the need for lifespan support will be even more critical for families who may be in financial or situational distress and who no longer have the option of terminating the pregnancy. Another concern is that clinicians in states that protect reproductive rights will over-emphasize the option of termination in an effort to convey the availability of options, but patients have also said that repeated offers of termination traumatize them and convey bias when they are planning to continue the pregnancy.2 Moreover, in states where the constituency is divided, lawmakers and the media are

“Disability Studies: The United States of America has a dark past and present in oppressing the reproductive rights and freedoms of people with disabilities. According to a recent report from the National Women’s Law Center, 31 states and the District of Columbia have laws that allow forced sterilization. Like abortion restrictions, these laws assume that other people, often parents, guardians, and government officials, are better equipped to make decisions for disabled people than the people with disabilities themselves. The Dobbs decision weakened constitutional protections for people with disabilities to lead self-determined lives.4 The decision has resulted in further devaluing of disabled lives as seen in a Declaration of Emergency by Louisiana Department of Health, which describes infants born with certain disabilities as “medically futile.” While medical futility is considered an absolute, the literature includes documented cases of survival for most of the conditions listed in the emergency rule.5 The termination of pregnancies where a fetus is thought to have these disabilities is not considered an abortion in Louisiana and its emergency rule is described as “necessary to prevent imminent peril to public health, safety, and welfare.” Parents who learn their child has or may have one of the diagnoses

on Louisiana’s list will face an even more challenging path to receive accurate information or pursue treatment. Rather than rectifying our history of eugenics, the Dobbs decision and other restrictions on reproductive freedoms only further marginalize people with disabilities and their right to bodily autonomy. - Kara Ayers, PhD, Associate Professor and Associate Director, University of Cincinnati Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities (UCCEDD), Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Division of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics

Bioethics: One particular challenge of prenatal disability education and support is its short time frame to make major decisions about pregnancy continuation, interventions (as available), and health care. This time crunch leaves little space for taking in the results of prenatal testing and learning about genetic conditions. Making informed decisions about health and health care means getting clarity about the facts of the situation and your values about the options, and then reconciling these.6 Many pregnant people know very little about disability, and many health care providers harbor the kinds of implicit bias against disability that are common throughout society.7 This situation makes it crucial to have opportunities for human connection and thoughtful deliberation, such as meeting other families in similar situations and considering what life might be like. But people who feel pushed to make a decision quickly are less likely to have these opportunities. In addition, no amount of information and resources can support informed choices if pregnancy is not a choice

at all. Research shows that for people who seek abortion care, being forced to continue the pregnancy results in worse pregnancy and life outcomes for them and their children.8 Finally, one very hopeful development of the past

few decades has been a steady increase in treatments that can take place during pregnancy to improve outcomes for babies and children. Pregnancy interventions like these, when they are available for certain conditions, are one of the strongest possible benefits of a prenatal diagnosis. But an increase in abortion limits and bans will have a chilling effect on research and experimental treatments, ultimately harming families by limiting the access to these interventions in many states. - Marsha Michie, PhD, Associate Professor of Bioethics, Department of Bioethics at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine

Bioethics: Prenatal genetic testing has been argued to be ethically obligatory

out of respect for the patient’s autonomy. For a patient to exercise control over her health, testing provides medically relevant information. Leaping from this premise, the principle of justice is cited as requiring the availability of testing for all, not just for those with means. The result is subsidization of testing by private and public insurers. Post-Dobbs, the provision of testing creates a “moral hazard”: providing information that cannot be acted upon, at least not without travel to another state.

Additionally, surveys of patients’ experiences with prenatal genetic testing overwhelmingly conclude it does not respect their autonomy for failing to provide proper counseling, understanding of the testing, and provision of equally-recommended relevant information about the tested-for condition and available supports for individuals with those conditions.9 Therefore, if the main justification has not been achieved despite decades of

Many pregnant people know very little about disability, and many health care providers harbor the kinds of implicit bias against disability that are common throughout society.7

“

practice, the justice argument should be to not subsidize prenatal genetic testing, since it does not empower the patient’s autonomy, and thereby avoid the moral hazard. In practice, the most justified course is if prenatal testing is subsidized, then so must the other recommended condition-specific information so as to provide the best chance of respecting the patient’s autonomy. - Mark W. Leach, JD, MA (Bioethics)

Legal: That Dobbs will result in fewer reproductive choices for pregnant people, including people with disabilities, is clear. Historically, some people with disabilities were forced to have abortions because of a belief that their child would have a disability or that, even if the child were born without a disability, the disabled parent would not be able to care for the child. As is true for people without disabilities, some people will want abortions, and some will not. However, for some pregnant people with disabilities, carrying a fetus to term may put their own health at risk.10 In states that adopt laws that do not provide an exception to an abortion ban to preserve the health of the mother, a full-term pregnancy can have dire consequences for them. Women with disabilities are much more likely to be the victims of violence, including sexual violence, than women without disabilities.11 If the disabled woman becomes pregnant because of rape, she may be forced to bear the child that is the result of that rape in states that do not provide for a rape exception to an abortion ban. In some rare cases, the severely disabled woman who has been impregnated may have little understanding of the gestational and birth process—and may be traumatized by having to experience changes in her body that she does not understand. - Robert D. Dinerstein, JD, Professor of Law and Director, Disability Rights Law Clinic, American University Washington College of Law (for identification purposes only)

To address these additional complications, possible solutions proposed by medical professionals, bioethicists, and disability advocates include the following: 1. Fully fund The Prenatally and Postnatally Diagnosed Awareness Act to ensure that patients get the support and information they need following a diagnosis. 2. Fully fund Medicaid waiting lists and disability services in their states to care for the families in need who will inevitably be having more children with disabilities. If states are going to require patients to continue a pregnancy, then they must also have the social safety nets in place to support families of children with disabilities to truly preserve the lives and welfare of those children. 3. Replace laws that allow forced sterilization of people with disabilities with policies that support bodily

autonomy and are directly informed by the voices of people with disabilities. 4. Mandate the training of health professionals in all states to ensure that information about disabilities is presented without conscious or unconscious bias.12

1. Nelson Goff BS, Springer N, Foote LC, et al. Receiving the Initial Down Syndrome Diagnosis: A Comparison of Prenatal and Postnatal Parent Group Experiences. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2013;51(6):446-457. doi:10.1352/1934-9556-51.6.446

2. May CP, Dein A, Ford J. New insights into the formation and duration of flashbulb memories: Evidence from medical diagnosis memories. Appl Cogn Psychol. 2020;34(5):1154-1165. doi:10.1002/acp.3704

3. Reardon S. Genetic Screening Results Just Got Harder to Handle Under New Abortion Rules. Kaiser Health News. Published June 27, 2022. Accessed August 25, 2022. https://khn.org/news/article/genetic-screening-results-just-got-harder-to-handle-under-new-abortion-rules/ 4. ASAN, et al. Memorandum: Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization and Its Implications for Reproductive, Civil, and Disability Rights. :10.

5. Wilkinson D, de Crespigny L, Xafis V. Corrigendum to “Ethical language and decision-making for prenatally diagnosed lethal malformations” [Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 19 (5) (2014) 306-311]. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;20(1):64. doi:10.1016/j.siny.2014.10.007

6. Petrova M, Dale J, Fulford BKWM. Values-based practice in primary care: easing the tensions between individual values, ethical principles and best evidence. Br J Gen Pract J R Coll Gen Pract. 2006;56(530):703709.

7. Iezzoni LI, Rao SR, Ressalam J, et al. Physicians’ Perceptions Of People With Disability And Their Health Care: Study reports the results of a survey of physicians’ perceptions of people with disability. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(2):297-306. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01452

8. Coleman S. Abortion, Science, and Morality in the Turnaway Study : New Perspectives for the Helping Professions: The Turnaway Study: Ten Years, a Thousand Women, and the Consequences of Having–or Being Denied–an Abortion , by Diana Greene Foster, New York NY, Simon & Schuster/Scribner, 2020, 360 pp. Hardback, $27.00, ISBN 9781982141561; Paperback $18.00, ISBN-13 978982141578. J Progress Hum Serv. 2022;33(1):96-105. doi:10.1080/10428232.2022.2037821

9. Bryant AS, Norton ME, Nakagawa S, et al. Variation in Women’s Understanding of Prenatal Testing. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(6):13061312. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000843

10. Rajkumar S. With Roe v. Wade overturned, disabled people reflect on how it will impact them. NPR. https://www.npr. org/2022/06/25/1107151162/abortion-roe-v-wade-overturned-disabledpeople-reflect-how-it-will-impact-them. Published June 25, 2022. Accessed November 17, 2022.

11. Shapiro J. The Sexual Assault Epidemic No One Talks About. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2018/01/08/570224090/the-sexual-assault-epidemicno-one-talks-about. Published January 8, 2018. Accessed November 17, 2022.

12. Meredith S. Prenatal Disability Education Summit Full Report –The Prenatal Disability Education Summit. In: University of Kentucky Human Development Institute; 2022. Accessed September 20, 2022. https://prenatalsummit.lettercase.org/prenatal-disability-education-summit-full-report/

“Disabled people are estimated at 10 percent of the general African population, but possibly as high as 20 percent in the poorer regions. (For example) the vast majority of Africans with disabilities are excluded from schools and opportunities to work, virtually guaranteeing that they will live out their lives as the poorest of the poor. School enrollment for the disabled is estimated at no more than 5-10 percent. For many, begging becomes a sole means of survival.” 3

According to an estimate by the WHO, 15 percent of the world’s population live with some form of disability, with over 80 percent of them living in Low and Middle-Income Countries.4

All too often we view these mega numbers as “just numbers,” not individuals with disabilities who live their lives under conditions far different than those experienced by the general population in our country. How people with disabilities in large countries are treated provides an opportunity to compare the efforts in our nation to ensure services, for the young and not-so-young people with disabilities in our communities.

with disabilities have received their condition as a punishment or are victims of bad luck or evil spirits.4

China is home to the world’s largest number of people with disabilities. There are 83 million people with disabilities in China, with a million in Beijing alone.

• 60 percent are illiterate.

• 40 percent are unemployed and nearly half cannot find a spouse.

• There are only 250 schools for children with disabilities having a total enrollment of only 100,000 students.

• There are 4.2 million children with congenital disabilities.

• The average salary of a worker with a disability is less than half of that of a worker who is not disabled.

• Only one-third of people with disabilities who need rehabilitative services have access to it.

• There are around 12 million people who are blind or visually impaired in China. Only about 5 percent of them receive any kind of formal schooling.

• Professionals trained to aid people with disabilities are desperately scarce. Europe has 185 times as many physiotherapists per person as China.

• People with disabilities are routinely denied jobs, driver licenses and places in universities because there aren’t any laws on the books that are supposed to prevent such practices.

• Students with a difference in leg length of more than 5 centimeters or a spinal curve of more than four centimeters are not allowed to major in subjects such as geology, civil engineering, veterinary science, main science or forensic medicine.

• Many Chinese believe that people

“Still, some indicators are improving. The number of people with disabilities receiving low-income benefits jumped to more than seven million in 2008 from fewer than four million in 2005. Nearly three in four children with disabilities attended school in 2008, compared with about three in five just two years earlier. The number of students with disabilities in universities and technical colleges in 2008 increased by 50 percent over 2006. Still, they amounted to a mere handful, just one out of every 5,000 students.”4

residents. Over 2.2% of this population (26.8 million individuals) experience some form of severe mental or physical disability.6

In 2011, 26.8 million out of 1.21 billion people in India have or had a disability, accounting for around 2.21 percent of the total population. Among people with disabilities, males comprised a larger share in comparison to females, at respectively 54 percent and 44 percent or 2.41 percent of males versus 2.01 percent of females.7

Women and girls with disabilities are forced into mental hospitals and institutions where they face unsanitary conditions, and are at risk of physical and sexual violence and experience involuntary treatment. “(They) are placed in institutions by their family members or police because the government fails to provide appropriate support and services.”8

“By 2050, 68 percent of the world’s population will live in urban areas, up from today’s 55 percent. One third of this increase is projected to happen in just three countries — China, Nigeria and India. (emphasis added) Yet, as urban populations grow, a big part of society continues to be marginalized and excluded — people with disabilities.”5

India is home to over 1.36 billion

In India, a majority of people with disabilities reside in rural areas where accessibility, availability, and utilization of rehabilitation services are not cost-effectiveness and major issues need to be considered. Research on the burden of disability, appropriate intervention strategies and their implementation to the present context in India is a big challenge.9

In addition, India is also experiencing a rapid increase in its elderly population; about 8% of the overall population were aged 60+ in 2011 and this figure is expected to grow to 11.1% by 2025. Over one-third of the country’s population is living below the poverty level In addition, health care quality is inadequate in poorer regions.10

“Around 15 percent of the world’s population, or estimated 1 billion people, live with disabilities. They are the world’s largest minority.” 2

“

“Segregation of Persons with Disabilities to the extent that they are not visible in public space is a norm in Russia. The overall attitude towards disability is negative as disability is considered shameful. The culture dates back to the Soviet era. An anecdote regarding the culture of seeing disability as shameful is very popular. A western reporter who asked whether Russia will be participating in the first Paralympic games got a flat reply from the Soviet representative – There are no Invalids in the USSR.” (sic)11

The largest country in the world is Russia with a total area of (6,601,665 square miles) equivalent to 11% of the total world’s landmass.12 In 2021, 11.6 million people were reported to have a disability.13

According to Human Rights Watch, Russian orphanages, where many children with disabilities grow up, often transition them to state institutions for adults when they reach 18 without their consent. Those who do move into the community often do not receive the support they need to live independently.14