ENCODING CULTURE II THE WORKS OF BARRY ACE

ENCODING CULTURE II THE WORKS OF BARRY ACE

P RE v IEW

By appointment

Heffel Gallery, Toronto

13 Hazelton Avenue

October 26 – November 9, 2022

All works can be viewed online at Heffel.com

For more information, please contact:

Tania Poggione tania@heffel.com 514-933-6615

We thank Leah Snyder, digital designer and writer, The L. Project, for contributing the following essays. Snyder writes about culture, technology and contemporary art, and is a con tributor to the National Gallery of Canada’s Gallery magazine and other Canadian art and architecture publications.

All works are accompanied by a letter of authenticity and provenance signed by the artist. All quotes are attributed to the artist unless otherwise noted.

Follow us @HeffelAuction:

L I X

THE WORKS OF BARRY ACE

Code C an mean many things. In the contemporary moment we understand code as the digital languages and protocols that program the applications and software we inter face with daily. Code is also a prescriptive set of rules and protocols that guide a culture and individuals within that culture on what is required to lead a good and sacred life, in Anishinaabemowin—Mino Bimaadiziwin.

“Encoding” simply means to convert something into a coded form. As Barry Ace’s work deals with the deep rooted aspects of Anishinaabe culture, as well as makes use of the dig ital refuse of our times, as an aesthetic iteration on Great Lakes material culture it is fitting to refer to what he does as “encoding culture.” Layers of cultural code are embedded into everything he creates.

In Ace’s work we see a trajectory of communication technology. From referencing traditional wiigwaasabakoon (birch bark scrolls) to digital tablets embedded into gashkibidaaganag (bandolier bags) Ace considers not only the negative impacts European technology has had on Indigenous people post-contact but also how it provides the capacity to innovate with agency, using new technologies as a form of cultural continuance.

ENCODING CULTURE II

IOGRAPHY

Barry aC e is a practicing visual artist and currently lives in Ottawa. He is a debendaagzijig (citizen) of M’Chigeeng First Nation, Odawa Mnis (Manitoulin Island), Ontario, Canada. Ace’s work embraces the impact of the digital age and how it exponen tially transforms and infuses Anishinaabeg culture (and other global cultures) with new technologies and new ways of communicating. His work attempts to harness and bridge the precipice between historical and contemporary knowledge, art and power, while maintain ing a distinct Anishinaabeg aesthetic connecting generations.

Ace has exhibited extensively, most recently in: Native Fashion Now: North American Native Style, Peabody Essex Museum (2016 – 2017: Salem, Massachusetts); Anishi naabeg Art and Power, Royal Ontario Museum (2017: Toronto, Ontario); Every. Now. Then. Reframing Nationhood, Art Gallery of Ontario (2017: Toronto, Ontario); 2017 Canadian Biennial, National Gallery of Canada (2017: Ottawa, Ontario); Àbadakone, National Gallery of Canada (2019: Ottawa, Ontario); Radical Stitch, MacKenzie Art Gallery (2022: Regina, Saskatchewan); wāwīndamaw—promise: Indigenous Art and Colonial Treaties in Canada, Nordamerika Native Museum (2022: Zurich, Switzerland); Art of Indigenous Fashion, Museum of Contemporary Native Arts (2022: Santa Fe, New Mexico); and Persistence/Resistance: Taiwan—Canada Indigenous Art Exhibition, Tainan Art Museum (2022: Tainan, Taiwan).

Ace’s work can be found in numerous public and private collections in Canada and abroad, most notably: National Gallery of Canada (Ottawa, Ontario); Art Gallery of Ontario (Toronto, Ontario); Canadian Museum of History (Gatineau, Quebec); Royal Ontario Museum (Toronto, Ontario); Ottawa Art Gallery (Ottawa, Ontario); Canada Council Art Bank (Ottawa, Ontario); Global Affairs Canada (Ottawa, Ontario); North American Native Museum (Zurich, Switzerland); Ojibwe Cultural Foundation (M’Chigeeng, Ontario); and the McMichael Canadian Art Collection (Kleinburg, Ontario).

A RTIST B

Barry Ace

1958 –

Traditional

Lokta Nepalese handmade paper, Pellon, capacitors, resistors, light-emitting diodes, inductor, glass beads, bias trim, circuit board and copper wire, on verso signed, 2021 67 3/4 × 38 7/8 in, 172 × 99 cm

P RO v ENANCE

Collection of the Artist

E x HIBITED

Central Art Garage, Ottawa, Material Matters—Materiality of Anishinaabeg-biimadiziwin, November 19, 2021 – March 19, 2022

a s a traditional dancer on the powwow circuit, Barry Ace has made many journeys across Canada and the United States to participate in competitions and ceremonial gather ings. During his travels, he has witnessed the cultural diversity of regalia that is unique to First Nation and Native Americans from the east to the west, north and south. The paper and textile regalia works, Traditional and Buckskin, are a man and a woman’s regalia, and reference patterns one might see worn on a dancer.

Traditional, the men’s regalia, is embellished with Ace’s contemporary iteration of the Woodland style motif of beaded flowers that evoke the healing energy of medicinal plants. As a dancer performs, the sacred medicine is evoked and transmitted to those pres ent. This concept of the transference of energy led Ace to make a connection between the bead, Manidoomin or “little spirit berry” in Anishinaabemowin, and electronic compo nents. Capacitors and resistors generously adorn the vest, cuffs, belt, apron, leggings and moccasins of the paper regalia. Integrated into the ornamentation are coiled inductors whose practical application is to store energy in a magnetic field created by the use of iron inside the coil. Aesthetically, the insulated copper wire wound around the coils calls to mind jewellery design. On the belt, Ace has inset an inductor within a circuit board to reference a buckle. Light-emitting diodes are sewn into the trim that outlines each section. The black paper and Pellon replicates black velvet, a material often used in Woodland style regalia. Animal hide and calico fabric are other materials that continue to be used for dancers’ rega lia. A cotton fabric that had its origins in India, calico was then introduced through trade with Britain and France post-contact and gifted as part of treaty negotiations. Ace has lined the inside of the shirt with the calico fabric referencing these treaty gifts. The handmade Lokta paper, tan in colour, recalls the texture of hide. The paper, sourced from Nepal, is pro duced using the inner bark of shrubs indigenous to the forests of the Himalayas. Its fibrous composition offers it a unique durability. As a material, it defies the types of damage paper often succumbs to—water, humidity and insect infestations. For this reason, it has been used to pass down knowledge in sacred Buddhist texts for thousands of years.

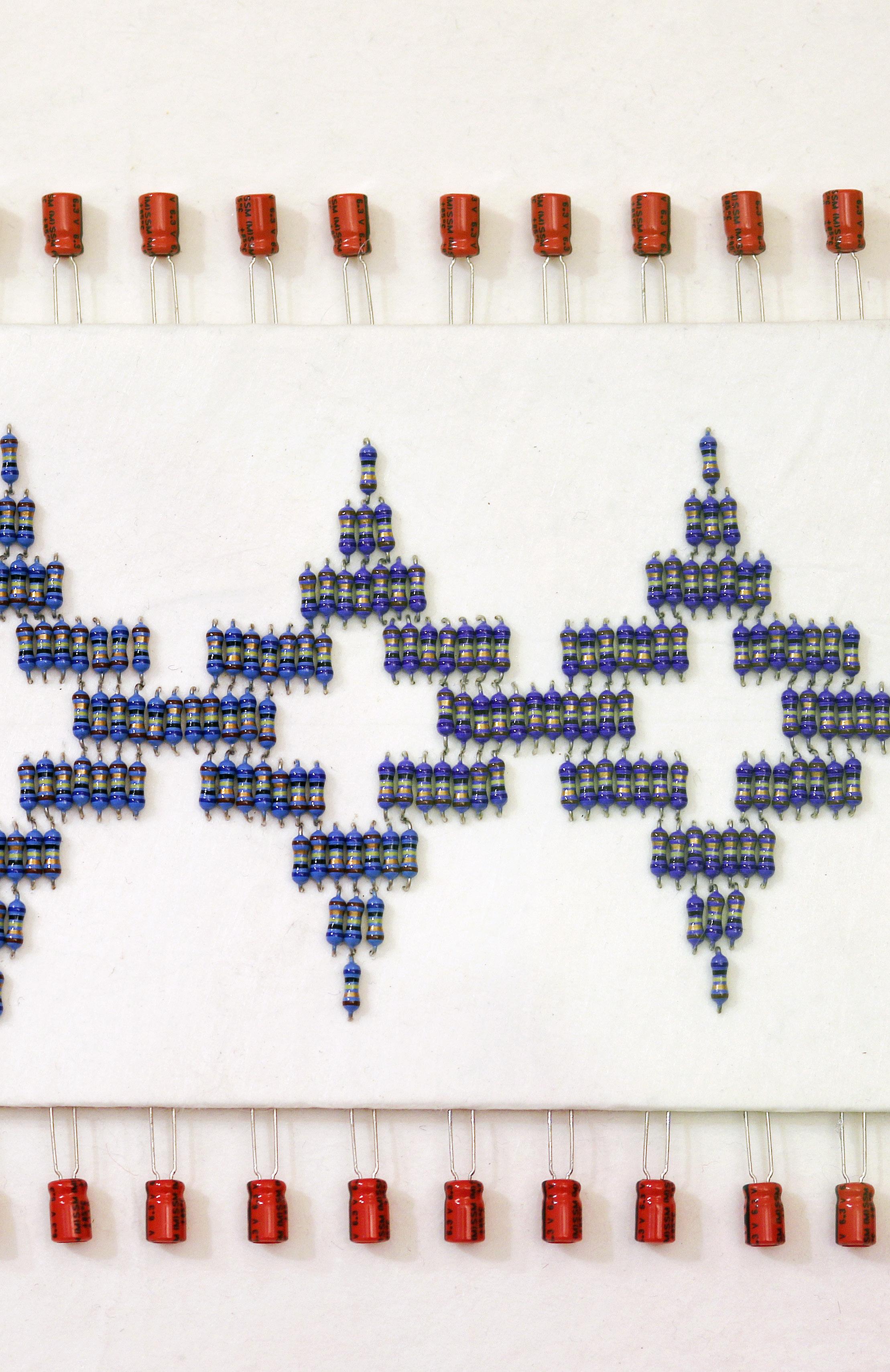

For Buckskin, Ace uses Pellon material as a semblance for buckskin hide often used in women’s traditional regalia. In the brain tanning process, hides turn white. This work refer ences women’s Plains style traditional regalia with fringes that extend off the arms to touch the ground, an embellishment that when moved in a controlled swaying motion references wind on prairie grasses. A horse hair trimmed beaded medallion with a Thunderbird hangs at heart level, a symbol of protection. Arranged at the top and bottom of the dress, ceramic

capacitors, like the Philips Mullard “tropical fish” capacitors with their striped patterns, are configured as morning stars; below the torso horse hair hangs from copper jingles; the diamond shape motifs with central morning stars represent a historical alliance between Anishinaabe communities. For Ace, the works are “autobiographical,” reminders of a specific time in his own personal history. “I was moved by the unique styles of regalia, all handmade, all works of art,” he states. Through the work he pays homage and respect to the men and women who continue to practice and maintain traditional knowledge and ceremony.

PRICE : $ 30,000

Barry Ace

–

Buckskin

Lokta Nepalese handmade paper, Pellon, capacitors, resistors, light-emitting diodes, porcupine quill, horse-hair, velvet, rope, glass beads and bias trim, on verso signed, 2021 67 3/4 × 38 7/8 in, 172 × 99 cm

P RO v ENANCE

Collection of the Artist

E x HIBITED

Central Art Garage, Ottawa, Material Matters—Materiality of Anishinaabeg-biimadiziwin, November 19, 2021 – March 19, 2022

PRICE : $ 30,000

1958

Barry Ace

1958 –

Study For Women’s Dance Regalia Yoke graphite, handmade Lokta paper and glass beads on paper, signed and dated, 2021 26 × 31 in, 66 × 78.7 cm

P RO v ENANCE

Collection of the Artist

E x HIBITED

Central Art Garage, Ottawa, Material Matters—Materiality of Anishinaabeg-biimadiziwin, November 19, 2021 – March 19, 2022

Study for Women’ S d ance r egalia y oke follows in the practice of Barry Ace using the technique of beading on paper as a way to work out and “test aesthetic concerns and motif relationships when creating intricate designs.” In the study, intentionally unfinished beadwork reveals the layers of progression from ideation to conclusion. Ace states, “People often don’t have an opportunity to see how an artist resolves problems through their artistic process.” In Study for Women’s Dance Regalia Yoke, Ace allows the viewer an occasion to see behind the process, to reveal how he works “to explore variations and aesthetic concerns in terms of figure/ground and texture/colour relationships in the preparatory works for my textile practice.”

The yoke is the part of the regalia that rests on the dancer’s shoulders extending on the back just above the shoulder blades. The left and right front pieces buckle together on the upper chest. Ace has produced other yokes, Women’s Woodland Jingle Cape (2014) as well as Healing Dance 2 (2015) which was acquired by the National Gallery of Canada and exhibited in the n GC ’s 2017 Canadian Biennial and now included in the exhibition Radical Stitch (Mackenzie Art Gallery). In Study for Women’s Dance Regalia Yoke, he abstracts the yoke’s form, splitting the assumed symmetry as a way to rupture the foregone conclusion of cultural stasis in the colonial perception. In the Woodland style flower and leaf motif, Ace flips the light and dark tones in the internal parts of the plant and their outline. Inside the leaf’s structure the beadwork swirls and eddies to create movement that replicates nature. The vibrant palette is set onto Lokta paper, wildcrafted and produced in Nepal by women’s cooperatives using traditional methods and the fibrous bark of a shrub Indigenous to the area. For Ace, the fragility of paper speaks to the precariousness of Indigenous culture since European contact. Also, the technique of beading onto paper is a painstakingly slow process. “Every second bead is stitched down, so the paper must be rolled each time from front to back to complete every stitch.” Study for Women’s Dance Regalia Yoke, demonstrates the level of care and precision Ace bestows on his work.

PRICE : $ 15,000

Barry Ace

1958 –

Biiskawaagan (Jacket) for Maungwudaus

handmade Lokta paper, calico fabric, capacitors, resistors, light-emitting diodes and glass beads on verso signed, 2020

27 × 48 1/2 in, 68.6 × 123.2 cm

P RO v ENANCE

Collection of the Artist

E x HIBITED

Central Art Garage, Ottawa, Material Matters—Materiality of Anishinaabeg-biimadiziwin, November 19, 2021 – March 19, 2022

a n important histori C al figure who has a recurring presence in Barry Ace’s work is that of Maungwudaus, meaning Great Hero. Born in 1811, in what was then Upper Canada, he was also known by his Christian name of George Henry and was an advocate, educator and translator. As well, he was a performer who travelled abroad, throughout the United

Kingdom and parts of Europe, entertaining royalty, aristocracy and artistic luminaries in George Catlin’s Indian Gallery. The performances were in the tableaux vivants style popular at the time. Translated from the French as “living pictures” the practice was to construct staged historical and “exotic” sets where people enacted scenes for the audiences.

Maungwudaus toured with several other Anishinaabe performers, including his wife. His children also accompanied them abroad. He self-published his travel journals under the title An Account of the Chippewa Indians, Who Have Been Travelling Among the Whites in the United States, England, Ireland, Scotland, France and Belgium. Such documentation was a rare phenomenon in its time, a reversal of the colonial gaze, written in the language of the colonizer and disseminated using the communication technologies that were available. The account records the death of his wife, some of his younger children as well as other per formers, who contracted smallpox and did not make it home. In 2010 Ace was invited by Anishinaabe artist Robert Houle, as part of Houle’s exhibition Paris/Ojibwa at the Canadian Cultural Centre in Paris, France, to perform an honouring for Maungwudaus’s troupe and for those who did not return. During the performance, titled A Reparative Act, Ace visited four locations in Paris to perform a traditional dance, calling out Maungwudaus’s name along with Noodinokay, Mishshemong and Saysaygon. A powwow dancer, in the Southern Straight style, Ace wore his own regalia for the performances; the regalia is now included in the work—Mino Bimaadiziwin.

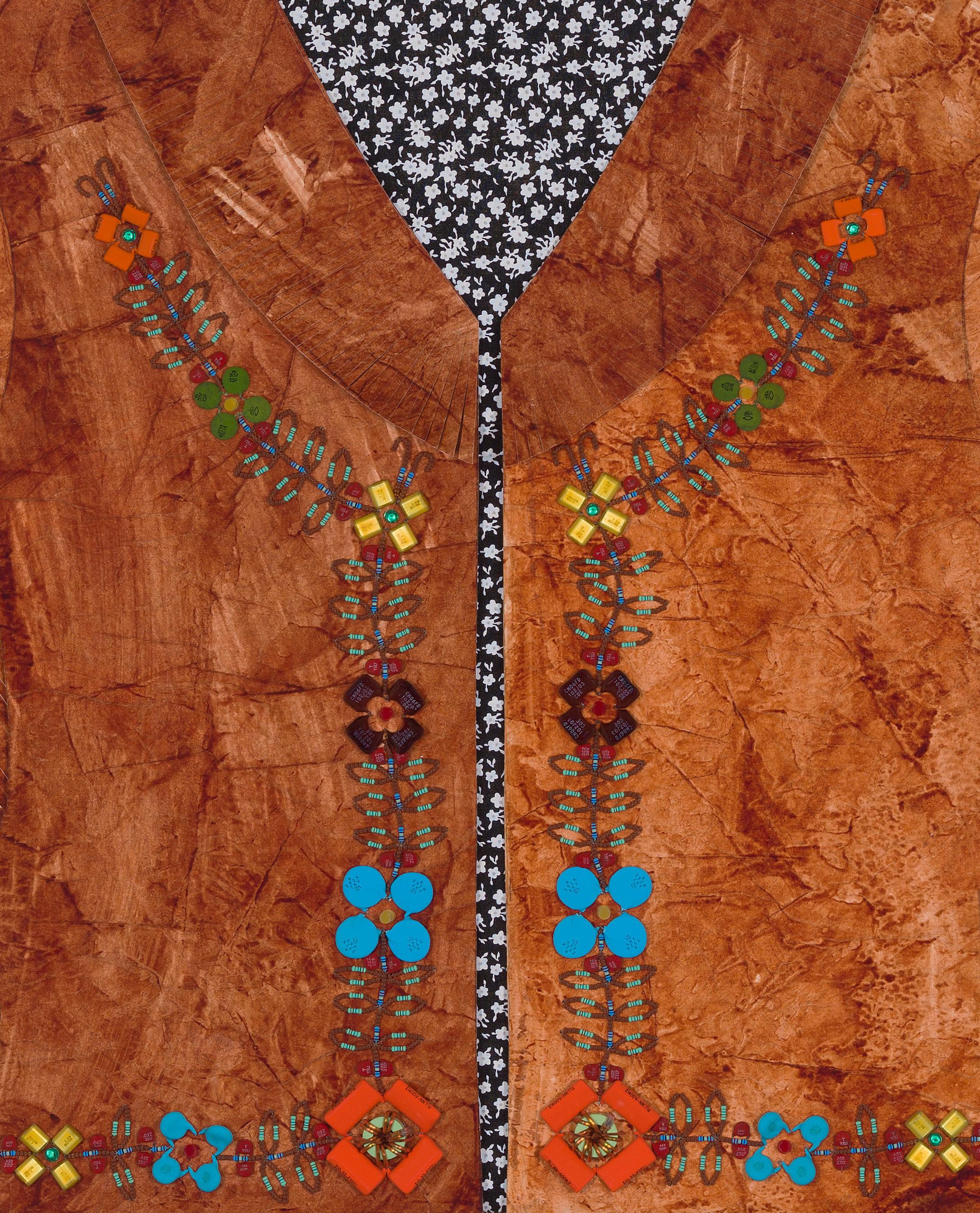

In Anishinaabe culture it is customary to bestow gifts to honour. With the Biiskwaagan (Jacket) for Maungwudaus, Ace has created another honouring for Maungwudaus, a gift for his legacy and his spirit. In the iconic archival photographic images of Maungwudaus he is seen wearing his own regalia, a coat fashioned in the style of the day yet embellished with Indigenous patterning and worn along with a bear claw necklace and headdress. This biisk waagan is embellished in Ace’s signature style using electronic components (capacitors, resistors and light-emitting diodes) to reference the medicinal floral motifs of Great Lakes material culture. Ace’s choice of wildcrafted Lokta paper, used in Nepal for thousands of years for sacred texts, is a visual likeness to tanned animal hide. Although a frontal ren dering of a coat, the fringes rise from the background, filling out the space in the deep-set walnut frame, providing more depth of form. Calico fabric, a material often used in danc er’s regalia, lines the inside of the jacket.

Spirit Mjikaawanak (Gauntlets) are a pair of gauntlets that can be considered as a companion piece to Biiskwaagan (Jacket) for Maungwudaus. As with the biiskwaagan, the mjikaawanak are made of the Lokta paper with similar electronic component ornamenta tion, including unique blue ceramic capacitors that resemble wild blueberries; the work is also set within a matching walnut frame. On the edge of the cuffs, Ace has added the fur of a nigig (otter), an animal important to the Anishinaabeg as a dodem (clan) as well as an inte gral animal in their migration and origin stories.

For Ace, the paper works are studies of material culture, an extension of his paper rega lia and bandolier bags. The inherent fragility of paper and the care required to work with its delicate quality are also an important component. As with all aspects of culture, and its continuance, the same level of care and attentiveness must be taken. The pieces symboli cally demonstrate this ethos, the jacket and gauntlets created “to keep the ancestors, both named and unnamed, warm in their journey.”

PRICE : $ 20,000

Barry Ace

1958 –

Study for Biiskawaagan (Jacket) for Maungwudaus

handmade Lokta paper, calico fabric, capacitors, resistors, light-emitting diodes and glass beads, on verso signed, 2020

7 1/2 × 13 in, 19.1 × 33 cm

P RO v ENANCE

Collection of the Artist

E x HIBITED

Central Art Garage, Ottawa, Material Matters—Materiality of Anishinaabeg-biimadiziwin, November 19, 2021 – March 19, 2022

PRICE : $ 2,500

Barry Ace

1958 –

Spirit Mjikaawanak (Gauntlets)

handmade Lokta paper, capacitors, resistors, light-emitting diodes, glass beads and otter fur, on verso signed, 2020

17 × 33 in, 43.2 × 83.8 cm

P RO

ENANCE

Collection of the Artist

E x HIBITED

Central Art Garage, Ottawa, Material Matters—Materiality of Anishinaabeg-biimadiziwin, November 19, 2021 – March 19, 2022

PRICE : $ 15,000

v

Barry Ace

1958 –

Mnemonic Code

direct digital print, glass beads, thread, porcupine quills, microchips, plastic on Somerset paper, signed and dated 2020 29 1/2 × 22 1/4 in, 74.9 × 56.5 cm

P RO v ENANCE

Collection of the Artist

m any of the titles of Barry Ace’s works reference terms employed in digital technology. In computer programming “mnemonic” is an abbreviation of a string of words used for a precise operation or instruction. Mnemonic also means a device—whether an object or other assistive aid—that is used to recount layers of associative meanings in order to convey a particular meaning and elucidation. “Code” is another word that implies communication and also has application in digital technology. Used to embed information that may be intentionally hidden or inadvertently latent, once put into effect by an activation, code has the potential to spark an event that can link to other events, providing a chain reaction.

Similar to the earlier work Manidoominens (Beaded) Landscape (2014), in Mnemonic Code Ace revisits the same foreboding image. Printed on archival Somerset paper, the image of the abstracted landscape was taken during his travels as a dancer on the powwow trail, giv ing it biographical meaning. On the horizon line that splits the composition, a string of train car boxes are linked together. A line of digital refuse intersects it. Ace states, “The vertical microchips reference the train. They carry information like the cars, with products, as they travel across the country.” In a market economy, the products we value speak to consump tive pathologies built on a colonial history of extraction and decimation, as with the bison that used to roam the Great Plains, now absent in Ace’s image. Above the train dark clouds pile, for Ace a signifier for what waits on the horizon. Three pointed quills jut out from the microchips, their outline like a warning flag. Although the strip of beadwork at the bottom recalls the palette of the landscape, it is severed from it, a gulf of white space like a terra nullius between cultural practice and the premonitory scene.

PRICE : $ 10,000

Barry Ace

1958 –

Erased

found cowboy boots, capacitors, resistors, light-emitting diodes, glass beads, tin cones, red heart trade beads, synthetic hair and coated wire, 2017

14 1/2 × 5 1/2 × 52 in, 36.8 × 14 × 132.1 cm

P RO v ENANCE

Collection of the Artist

E x HIBITED

John B. Aird Gallery, Toronto, Queer Landscapes/Queer Intersections, May 30 – June 23, 2017

Carleton University Art Gallery, Ottawa, To Be Continued: Troubling the Queer Archive at cuag, September 24 – December 12, 2020

Art Toronto, Metro Toronto Convention Centre, October 29 – 30, 2021

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, The Governor General’s Awards in Visual and Media Arts 2022 Exhibition curated by Gerald McMaster, October 13, 2022 – January 29, 2023

t hese attention G ra BB in G boots are a conversation starter. Painted with a celebra tory palette and baroque in their lavish ornamentation, they are embellished with digital bling painstakingly applied by the artist by piercing with an awl into the hard leather of the vintage boots. Ceramic capacitors, resistors and light-emitting diodes make up the design based on the traditional floral motifs of the Great Lakes material culture whose beadwork referenced the medicinal flowers and plants. Extended off of the calf of the boots are tele communication wires, referencing “traildusters,” moccasins that had animal fur, such as foxtails, attached to the back in order to sweep away traces of the wearer’s footsteps during enemy pursuit or during ceremonies.

Created in 2017, Erased builds on the footwear series that Barry Ace began in 2006. For the initial pair, he used his own patent leather Kenneth Cole Reaction dress shoes. Titled

Reaction, the shoes were exhibited as part of Changing Hands 3: Art Without Reservation at the Museum of Art and Design in New York City, then toured as part of the Native Fash ion Now exhibition, with locations that included the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian (nmai ). Nigik Makizinan (2015), in the collection of the National Gallery of Canada, was exhibited in Àbadakone/Continuous Fire/Feu continuel, the n GC ’s 2019 survey show of International and contemporary Indigenous art. Most recently, Fox Tail Moccasins (2016) was acquired by the McMichael Canadian Art Collection and Efface (2017) by a private collector.

As an Indigenous artist, Ace’s series of footwear assemblages demonstrate how cultural continuance is driven through material and aesthetic innovation. Their futuristic quality underscores the concept of Indigenous survivance, the portmanteau of survival and endur ance. Ace creates footwear fit for a journey that requires foresight, while also bringing along relevant and life sustaining knowledge from the past.

The cowboy boots were sourced at Housing Works, a second hand shop in Hell’s Kitchen, while Ace was in New York City for the opening of Native Fashion Now. Founded in the 1990s, Housing Works is an organization whose “mission is to end the dual crises of home lessness and aids through relentless advocacy, the provision of lifesaving services, and entrepreneurial businesses that sustain our efforts.” 1 Proceeds from the shop go directly to their programming and services. Another driver for Ace is aids/hi V advocacy. Like other gay men of the era, he witnessed the aids pandemic wipe out a generation of young men.

Governments failed to acknowledge the urgency. At the time, with regards to funding for effective treatment, public awareness, or support programs for those infected, there was no expediency as the gay community was stigmatized. Coming of age in the 1980s, Ace was living in Toronto during the time of the evolving Queen Street West art scene, and encoun tered Michael Snow, Joyce Weiland and others. The Toronto scene also included General Idea, whose iconic public art sculpture aidS (1987) reworked Robert Indiana’s 1964 loVe sculpture as a response to the pandemic. At a critical moment, Ace saw how art activism could be used as a strategy to promote dialogue around controversial issues.

The exhibition history of Erased includes John B. Aird Gallery in Toronto for Queer Landscapes/Queer Intersections in 2017, To Be Continued: Troubling the Queer Archive at Car leton University Art Gallery in Ottawa from 2019 – 2020, Art Toronto 2021, and will be included in the Governor General’s Award Media Arts Exhibition Fall 2022 at the National Gal lery of Canada, Ottawa. Curated by Gerald McMaster, this exhibition will position Erased in proximity to General Idea’s retrospective exhibition at the n GC ; Erased drives the point home that aids continues to be an important issue and that the gay community continues to be marginalized.

1. https://www.housingworks.org/about-us PRICE : $ 18,000

Barry Ace

1958 –

Bandolier for Pasapkedjinawong (The river that passes between the rocks) Rideau River motion sensor display monitor with movie, velvet fabric, cotton fabric, metal, coated wire, plastic, paper, coroplast, metal hardware, capacitors, resistors, light-emitting diodes, glass beads, vintage circuit boards, coated wire, glass beads, glass white heart beads, cotton thread, synthetic sinew, bronze screen and polyester edge bias, 2019 84 × 11 1/2 × 2 in, 213.4 × 29.2 × 5.1 cm

P RO v ENANCE Collection of the Artist

E x HIBITED

Central Art Garage, Ottawa, Material Matters—Materiality of Anishinaabeg-biimadiziwin, November 19, 2021 – March 19, 2022

t he C onfluen C e of three rivers meet in the area of what is now known as Ottawa and Gatineau, two urban centres that face each other across a divide of water. The Kichi-Sìbì (Ottawa River), is the largest, flowing from its source at Lake Capimitchigama in Northern Quebec, gaining a more intense flow as it moves through another lake, Timiskaming or Témiscamingue in French, a body of water politically split in half between the provinces of Ontario and Quebec. Other tributaries flow into the Kichi-Sìbì as it moves eastward, joining the waters of the St. Lawrence River towards the moment where all the waters will greet the sea.

This confluence is now known as the National Capital Region (n C r ) and encom passes the extended area around the municipalities of Ottawa, Ontario and Gatineau, Quebec. The local watershed includes marshes and extensive wetlands. Because of the fertile soil, farming plots, partitioned through centuries of European settlement, mark the landscape. From the North, on the provincial side of Quebec, the Tenàgàdino (Gatineau) flows into the Kichi, slipping into the river—zibi, sibi or sipi in the Algonquin dialect of Anishinaabemowin—quietly. Almost directly across, on the southern shoreline, the Pasapkedjinawong Zibi spills into the Kichi accompanied by the pounding sound of the Rideau Falls. As with all watersheds, everything is connected: what happens above the soil trickles into the groundwater; what is done downstream has implications upstream.

Embedded into the bandolier bag is a digital tablet that is activated by a hidden motion detector as the viewer approaches. Barry Ace uses the tablets to “articulate the con cept of animism” and to convey that a bandolier is understood as an animate object in Anishinaabemowin and is in relationship with the viewer who activates it through their presence. The digital footage programmed in the tablet documents the force by which one river cascades into another at the Rideau Falls. Filmed by Ace in October 2019, the autumn sunshine provided no indication of the isolation that would descend in the winter of 2020. The bandolier is part of a series of works by Ace honouring water, including Bandolier for Gichi-ziibi (Big River), Ottawa River and Bandolier for Water and Plant Life along with bags for the Great Lakes: Bandolier for Aanikegamaa-gichigami: Lake Erie (Chain of Lakes), Bandolier for Gichi-aazhoogami-gichigami: Lake Huron (Great Crosswaters Sea), Bandolier for Gichi-zaaga’igan: Lake Ontario (Big Lake). The bandoliers were created in 2019 and with the exception of Bandolier for Pasapkedjinawong, are all in private collections in Canada and the United States.

The particular waterway it honours has been made even more poignant by the C o V id -19 pandemic. During lockdowns, when places to publicly gather were limited, the site of the falls became a safe location to socially distance with loved ones. The view looks out towards the ancient hills gently rising from Gatineau Park. The sun slips below them making the Rideau Falls a preferred gathering spot to watch the setting sun. On any given night, many different languages can be heard spoken.

The colonial name of Canada’s capital city is derived from the Algonquin word for trade— adawe. Here on the unceded Anishinaabeg Algonquin aki (land), that the Algonquin have inhabited for thousands of years, the confluence of these waterways became a location for pluralistic cultural and resource exchange. First Nations from across Turtle Island passed through. Waterways were the superhighways before the advent of trains and automobiles, in which one tributary convened with another. They were places that became key for var ious transactions as well as for ceremony: to offer gratitude for safe arrival or prayers for a journey yet to come.

With the digital documentation of the Pasapkedijinawong the bandolier holds inside of it the spiritual traces of this site. The floral motifs reference the material culture of the Anishinaabeg, healing plants and flowers, some of which may grow at the water’s edge. As Odawa Anishinaabeg, in the practice of demonstrating respect, Ace has created a stunning tribute.

This work is mounted on a blue wooden wall mount plinth which measures 84 × 25 1/4 inches.

PRICE : $ 37,500

Barry Ace

1958 –

How Can You Expect Me to Reconcile, When I Know the Truth?

wood, hemp rope, metal, found vintage fabric doll, linen, organza, bronze screen, electronic components, glass beads, deer hide, cotton thread and vinyl, 2018 112 × 107 × 53 in, 284.5 × 271.8 × 134.6 cm

P RO v ENANCE

Collection of the Artist

E x HIBITED

o C ad University, Toronto, Nigig Visiting Artist Residency, Indigenous Visual Culture Program, January 9 – February 6, 2018

Galerie Saw and Supermarket Stockholm Independent Art Fair, Stockholm, Public Disturbance: Politics and Protest in Contemporary Indigenous Art from Canada, April 12 – 15, 2018

University of Windsor, School of Creative Arts Gallery, For As Long as the Sun Shines; the Grass Grows and the River Flows, November 19 – November 23, 2018

Art Toronto, Metro Toronto Convention Centre, October 29 – 30, 2021

Central Art Garage, Ottawa, Material Matters—Materiality of Anishinaabeg-biimadiziwin, November 19, 2021 – March 19, 2022

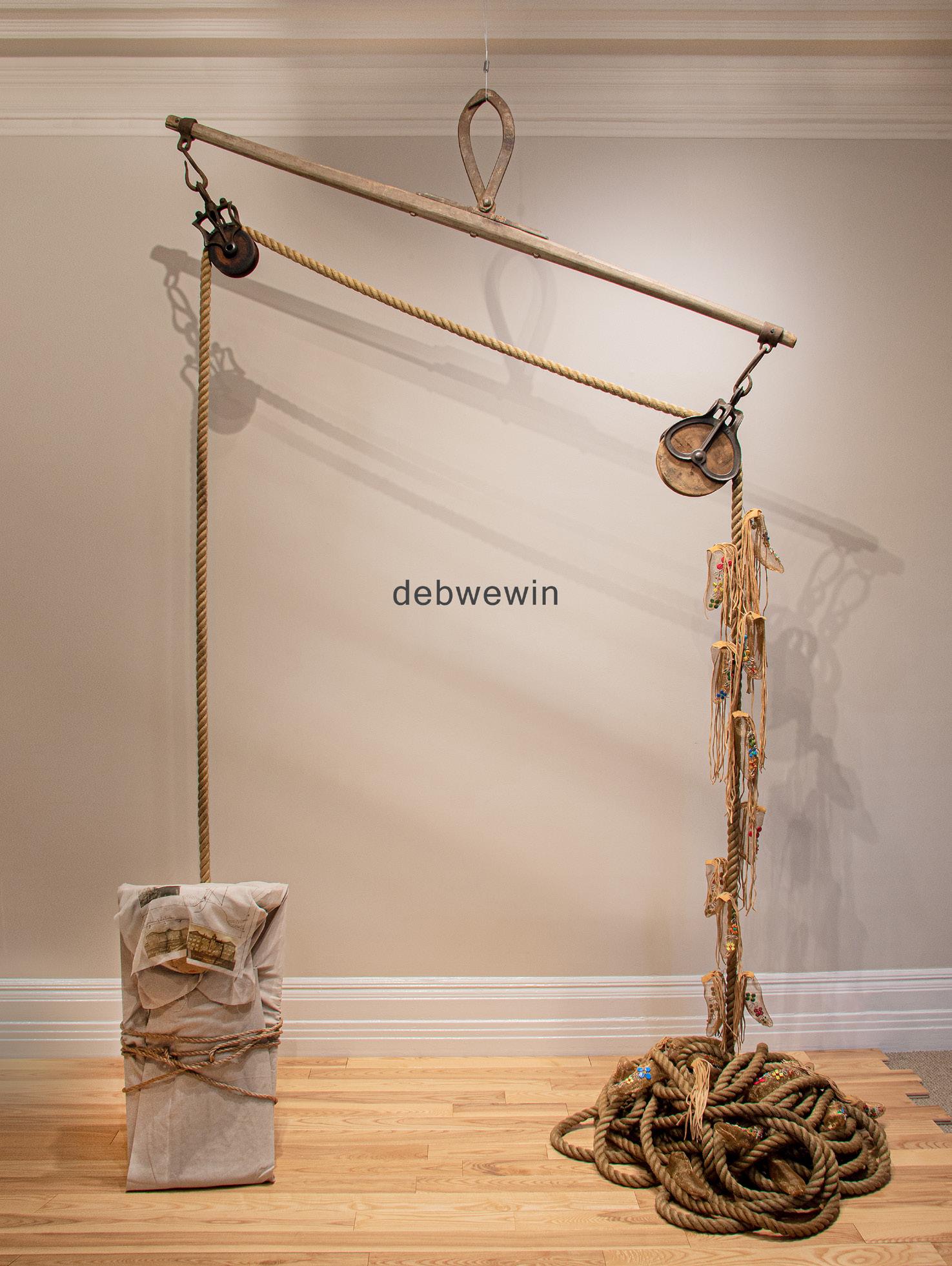

i n Ho W c an y ou e xpect m e t o r econcile, W H en i k no W tH e t rut H ? a work that grapples with the Canadian Indian residential school system, dry transfer letters spell out “debwewin.” The word, which means truth in Anishinaabemowin, is positioned slightly back from the installation, which is assembled from sourced antique apparatuses and materials, including what resembles a yoke, its lopsidedness connoting an unequal tethering. Barry Ace has added pulleys that could be viewed as “representing the scales of justice or injus tice.” Thick nautical hemp rope runs the length from one side to the other descending into a pile on the right, on the left knotting around a small form. The concealed shape underneath the gauze is a cradleboard, a vessel used in many First Nations to carry babies and called a tikinagan in Anishinaabemowin.

The work was created during a residency for Ontario College of Art & Design Univer sity’s (o C adu ) Nigig Residency in January 2018, an initiative of the Indigenous Visual Culture Program at o C adu. It travelled to Stockholm, Sweden as part of the group exhi bition puBlic diSturBance: Politics and Protest in Contemporary Indigenous Art from Canada. Curated by Ottawa’s Galerie saW Gallery for the Supermarket 2018 Stockholm Independent Art fair, the location where the work was installed was in a slaughterhouse in Slakthusområdet, the Meatpacking district of Stockholm. It was also exhibited as part of Art + Law Indigenous Artist in Residence Program, a partnership between the Arts Council Windsor & Region, the University of Windsor Faculty of Law and School of Creative Arts that coincided with the 2018 World Indigenous Law Conference—Waawiiatanong Ziibi: Where the River Bends, The Application of Indigenous Laws in Indigenous Communities and in the Courts.

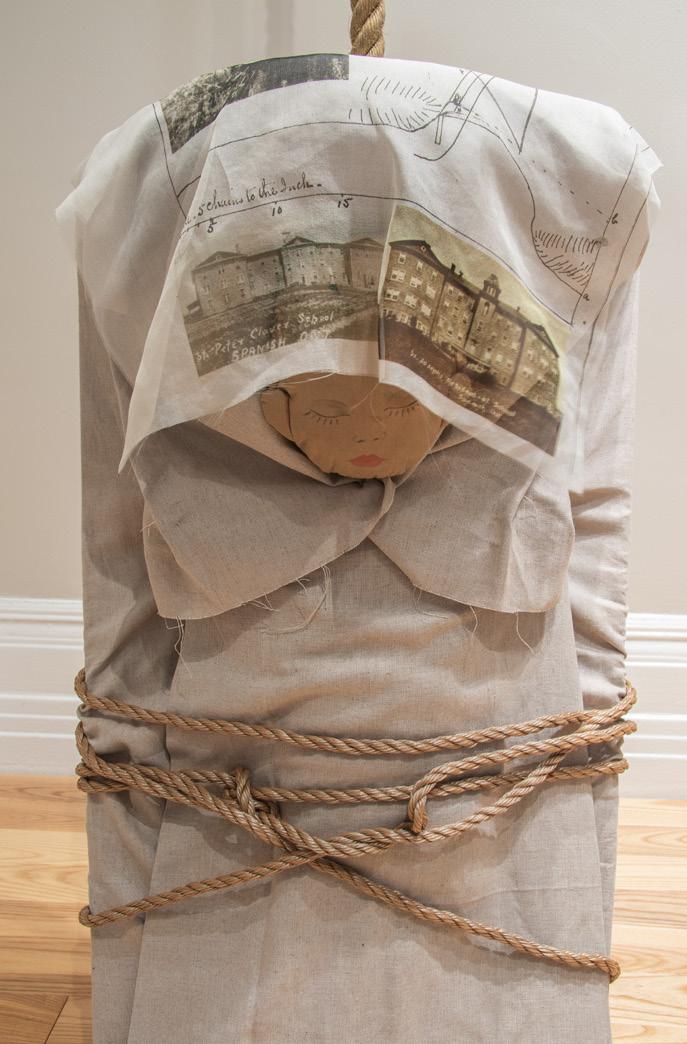

In the most recent install, the face of the cloth vintage doll secured inside the tikinagan is revealed. Previously, the fabric hid the object entirely. Without looking closely, its pres ence could be missed. For Ace, the work was a “presage” of the events of May 2021 when the Canadian media announced that the unmarked graves of 215 unnamed children were “discovered” by radar technology at Kamloops Indian Residential School. For Indigenous people, it was not a “discovering” but an “uncovering.”

On the piece of translucent and ghost-like organza that hangs over the doll’s head, Ace has printed archival images. As with much of Ace’s work there is a biographical underpin ning. Printed on the fabric is an image taken by his grandmother of his great-aunt as a child. In her arms, she is holding his father as a baby. Other images include a hand drawn map and vintage photographs of St. Peter Claver School for boys and St. Joseph’s School. Located in Spanish, Ontario, the two schools combined made up one of the largest Indian Residential Schools in Ontario. His great-aunt attended St. Joseph’s.

The hemp rope references the type used by the Garnier, a boat that towed a large open skip called the Red Bug. The skip transported the children from the reserve communities on Manitoulin Island to the Spanish Residential Schools on the mainland. Suspended from the cordage, spilling out onto the floor, are mesh forms resembling children’s footwear, perhaps European in style or moccasins or both, hybrid apparel for navigating through dis parate worlds. Some are covered with Ace’s signature embellishment of electronic resistors,

capacitors and light-emitting diodes, referencing the traditional knowledge and culture that survived the forced assimilation that occurred at the schools. Others have no embel lishment, rendered vacant and hollow to signify cultural loss or death. The motifs represent medicinal flowers and plants to transmit what is required to restore spiritual balance. Attached as an appendage to the back of the bronze mesh forms are long deer hide fringes which transform the footwear into “traildusters,” a type of moccasin that was worn with fur, like foxtail, extending from the ankle and heel. The function of the design implementation was to erase one’s tracks on a trail while being pursued by a potential enemy. The instal lation is moored on a piece of wooden floor, a material detail that recalls the Victorian era buildings that housed the Indigenous children. Uneven planks jut out on one end.

Ace’s continual circling back to previous aesthetic and design decisions is a way to revisit particular themes that shape his work from a slightly different perspective, building on prior iterations while incorporating uncovered information, whether from the archives or current issues. His practice is an examination of the legacy of historical trauma, countered with the questioning of what the strategies are that promote cultural continuity.

Please note: this work is comprised of multiple assembled elements and may vary in appearance following each installation.

PRICE : $ 120,000

Barry Ace

1958 –

Slipped Through the Net

vintage shoe lasts, bronze screen, capacitors, resistors, glass beads, metal pulley, copper, rope, twine and deer hide, 2021 40 × 6 × 3 in, 101.6 × 15.2 × 7.6 cm

P RO v ENANCE

Collection of the Artist

Slipped tH roug H t H e n et and Remnant are two auxiliary works connected to the larger installation of How Can You Expect Me to Reconcile, When I Know the Truth? (2018). In these smaller assemblages, Barry Ace has integrated the antique shoe lasts, or molds, he used to shape the bronze screen into child-sized footwear for the installation work. In How Can You Expect Me to Reconcile, When I Know the Truth? all of the moccasin forms are hollow, clinging and cascading down the nautical rope suspended by a pulley system that is positioned like an unbalanced yoke or scale of (in)justice. The rope pools onto the floor where more moc casins become intertwined within the mass. Collectively, these three works consider the impact of the Canadian Indian residential school system on generations of Indigenous chil dren, recognizing that it is a fragmented and entangled history.

In both Slipped Through the Net and Remnant, the bronze screen moccasins cover a solid wooden core that are partially embellished with floral motifs, referencing that some tradi tional knowledge and culture survived the adverse impact of colonization. In his signature style, Ace’s 21st Century iteration of the curvilinear beadwork of Great Lakes material culture references medicinal plants and flowers as healing, while his use of capacitors, resis tors, and light-emitting diodes are a simile for Great Lakes beadwork.

A common element to all three works are the deer hide fringes that are attached to the moccasin heels, referencing traildusters used by southwestern and northeastern tribes to erase the tracks left by their footprints. One different aspect in Ace’s positioning of these traildusters is that the fringe falls forward over the moccasins to symbolize that these sto ries must not be erased. In Remnant, hemp rope wraps around parts of a pulley mechanism from which the shoe last hangs from. In Slipped Through the Net Ace transforms the copper mesh into a rope that suspends the moccasin from a vintage metal pulley. A skirt of mesh encompasses the moccasin which appears to be freeing itself from the confines of the net. Both works are optimistic in their narrative that due to tenacity and perseverance, some of the remnants of culture slipped through; that despite being forced to assimilate to a Euro pean semblance, there has always been cultural continuance.

:

PRICE

$ 7,500

Barry Ace

Remnant

vintage shoe lasts, bronze screen, capacitors, resistors, glass beads, metal pulley, copper, rope, twine and deer hide, 2021 36 × 4 × 3 in, 91.4 × 10.2 × 7.6 cm

P RO v ENANCE

Collection of the Artist

PRICE : $ 7,500

1958 –

Barry Ace

1958 –

Transformer

vitrified clay, slip-paint, capacitors, light-emitting diodes, glass beads, circuit board and coated wire, 2018

9 1/2 × 8 × 21 in, 24.1 × 20.3 × 53.3 cm

P RO v ENANCE

Collection of the Artist

t ransformer B uilds on Barry Ace’s interest in acknowledging the material culture of the Anishinaabeg in his artistic practice. The work is part of a series Ace created during a 2018 residency with master potter David Migwans. It was an opportunity for Ace to return to his home community of M’Chigeeng First Nation on Manitoulin Island to work alongside him. Migwans’s own practice was informed by working with his cousin Carl Beam, during which he learned to perfect the technique of coiled handbuilding pottery, a process where the potter works without the aid of a wheel. Beam’s interest was refined during his time spent in Santa Fe, New Mexico, observing the Anasazi mimbres bowls in order to integrate traditional methods with his own contemporary Anishinaabe aesthetic. Ace’s clay work contains the artistic bequest of Beam as well as Migwans, coalescing their teachings into his vessels.

With Migwans, Ace gathered clay from local deposits in and around Manitoulin, combin ing it with sand and minerals to provide the clay with additional strength as well as texture, colour and refractive qualities. Ace experimented with colour gradations and surface paint ing, using mineral and slip based natural paints and hematite polished surfaces. On the

vessel, Ace has used slip to depict the figure of a horned shaman, a motif that recalls the pictographs found in various regions around the Great Lakes, spiritually important sites for the Anishinaabeg, a motif that also appears in the work of Migwans and Beam. The vessels were fired in an outdoor kiln under the direction of Migwans, during which Transformer went through a vitrification process. Under extreme heat, crystalline silicate compounds melt into a noncrystalline atomic structure transforming earthen clay to hardened glass.

Prior to firing, Ace embedded glass beads into clay, as well as imprinted holes in the areas where the capacitors and light-emitting diodes would be reintegrated after. A circuit board and coated wire, the digital refuse of our times, reaches out from within the material choice that connects the work to ancient traditions. During the residency, Ace was able to examine pottery shards uncovered on Manitoulin as part of the Providence Bay Bk-Hn-3 site, and housed in the Ojibwe Cultural Foundation collection in M’Chigeeng. The dig site, located in the southern tip of Manitoulin, is the “largest archaeological site in the Lake Huron region at over two acres, with three longhouses and a successful commercial fish ery.” 1 The site supports evidence that the material culture of the Anishinaabeg included clay vessels. In this piece Ace “transforms a utilitarian object into an abstracted contempo rary art work.” He states further, “what is profound is the literal connection as a maker with clay drawn directly from our traditional homeland and the shaping of the earth into some thing tangible and meaningful, as a sovereign act of being Anishinaabe.”

1. https://www.manitoulin.com/anishinaabe-archeology-project-open-now-ojibwe-

cultural-foundation/ PRICE : $ 7,500

Barry Ace

1958

Ampacity

copper, circuit-board, resistors, capacitors, light-emitting diode, beads, birchbark, porcupine quill, wood and metal

11 1/2 × 8 in, 29.2 × 20.3 cm

P RO v ENANCE

Collection of the Artist

a mpa C ity is an electrical term that applies to the measurement of current and the max imum load a conductor, like a wire, can carry. When the conductor is burdened with a load beyond its capacity, the system may malfunction or shutdown. Barry Ace uses these electri cal terms and objects as metaphors to think through the mechanism of colonization and the physical as well as spiritual burdens placed on Indigenous communities post-contact. In the work Ampacity, Ace has created an assemblage of objects and components that appear to be disparate: a quill, wire, a circuit board and the figure of a thunderbird cut out of metal. The conductive copper wire feeds into the top of the circuit board; extending from the bottom edge Ace uses electrical components to simulate traditional Anishinaabe floral bead work. Copper is a sacred element in Anishinaabe cosmology; the flora and fauna depicted in traditional beadwork represents plants with healing properties. The birch bark upon which the composition rests references wiigwaasabakoon, the birch bark scrolls used by the Anishinaabe for recording-keeping. As with Synthesis (2018), Ace considers the way cul ture is transmitted. As the interlocutor between the copper wire and floral motif, the circuit board, like the birchbark, has the capacity to relay instructions for cultural continuance, yet if the load travelling via the wire conductor is in excess it can “render a functioning circuit board inoperative but this does not mean it is beyond repair.” As with culture, there is the capacity to restore.

In Gaak (Porcupine) the minimalist composition includes an embossed porcupine pur chased in Paris during Ace’s trip for Robert Houle’s Paris/Ojibwa at the Canadian Cultural Centre and Ace’s accompanying site specific performance, A Reparative Act. The metal piece framing the porcupine is an electrical measurement gauge that reacts to fluctuations in ambient temperature, a metaphor for cultural flux. Below, Ace has stitched a porcupine quill to signify a “sharp and poignant point” regarding the abrupt disruption caused by con tact. Beyond the quill hangs a strand of trade beads, goods used in the service of colonial seduction. Each work’s composition is a visual haiku of objects, that when read together, are a critique of the impact of colonization—as Ace states, a “mnemonic device through which multilayers of meaning are expressed.”

–

PRICE : $ 2,500

Barry Ace

Gaak (Porcupine)

embossed paper, ink, birch bark, capacitors, copper, brass, vintage glass trade beads, raffia, porcupine quill and wood, on verso signed, titled and dated 2020 16 1/8 × 8 3/4 in, 41 × 22.2 cm

P RO v ENANCE Collection of the Artist

PRICE : $ 2,500

1958 –

Barry Ace

1958 –

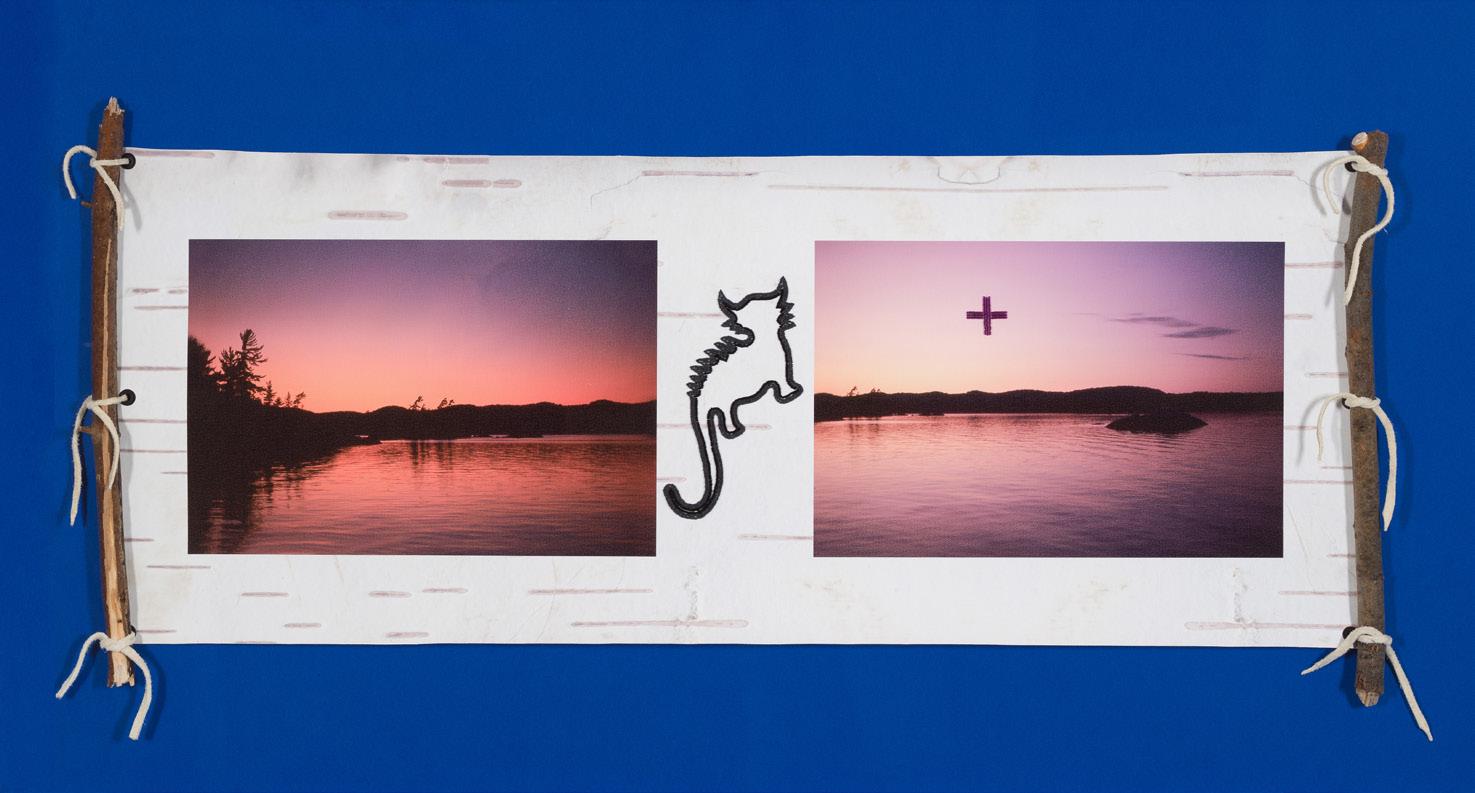

Mishibijiw and Morning Star (Memory Landscape II #9)

digital print on canvas, glass beads, thread, wood and deer hide on verso signed, titled, dated 2019 and inscribed #9 14 1/2 × 32 in, 36.8 × 81.3 cm

P RO v ENANCE

Collection of the Artist

i n Mishibijiw and Morning Star (Memory Landscape ii #9), two images form the panorama of a vivid sunset Barry Ace recalls witnessing in McGregor Bay, Manitoulin. After fishing in the bay, the sunset “became increasingly more powerful as dusk fell.” For Ace, the imagery becomes an “emotional sign-post” of a shared moment in time. In the divide between the two scenes, black beadwork forms the outline of the mishibijiw, the underwater panther of Anishinaabe mythology whose domain is the watery depths. On the right side, the dark silhouette of a rock rises out of the water resembling the curve of the mishibijiw’s back. Also on the right, Ace has beaded a niigaanaasnok (morning star), providing an ambiguous qual ity to the scene—is it dusk or is it biidaaban (dawn), a sacred time?

This work is part of a larger series, Memory Landscape I (2014) and ii (2014 – ongoing), that visually references the birchbark scrolls that the Anishinaabeg used for record-keeping. The images come from Ace’s own archive of digital scans of film slides from the 1980s taken during memorable journeys around Manitoulin Island and the surrounding areas. Memory Landscape I was created to honour the life of Ace’s close friend and was produced as a complete set. Memory Landscape ii continues with the imagery. Each scroll exists as a standalone work or can be lashed to another. Ace states, “These works reveal their dual ity and dichotomy through the diptych image.” The images suggest presence/absence, day/night or the earth, where the mishibijiw can be found, versus the skyworld, the domain of the Thunderbird, a sacred being who offers protection during journeys in life as well as into death. For Ace, the dualities present a “continuous personal narrative that is simultane ously rooted in the ancient and the contemporary.”

PRICE : $ 2,900

Barry Ace

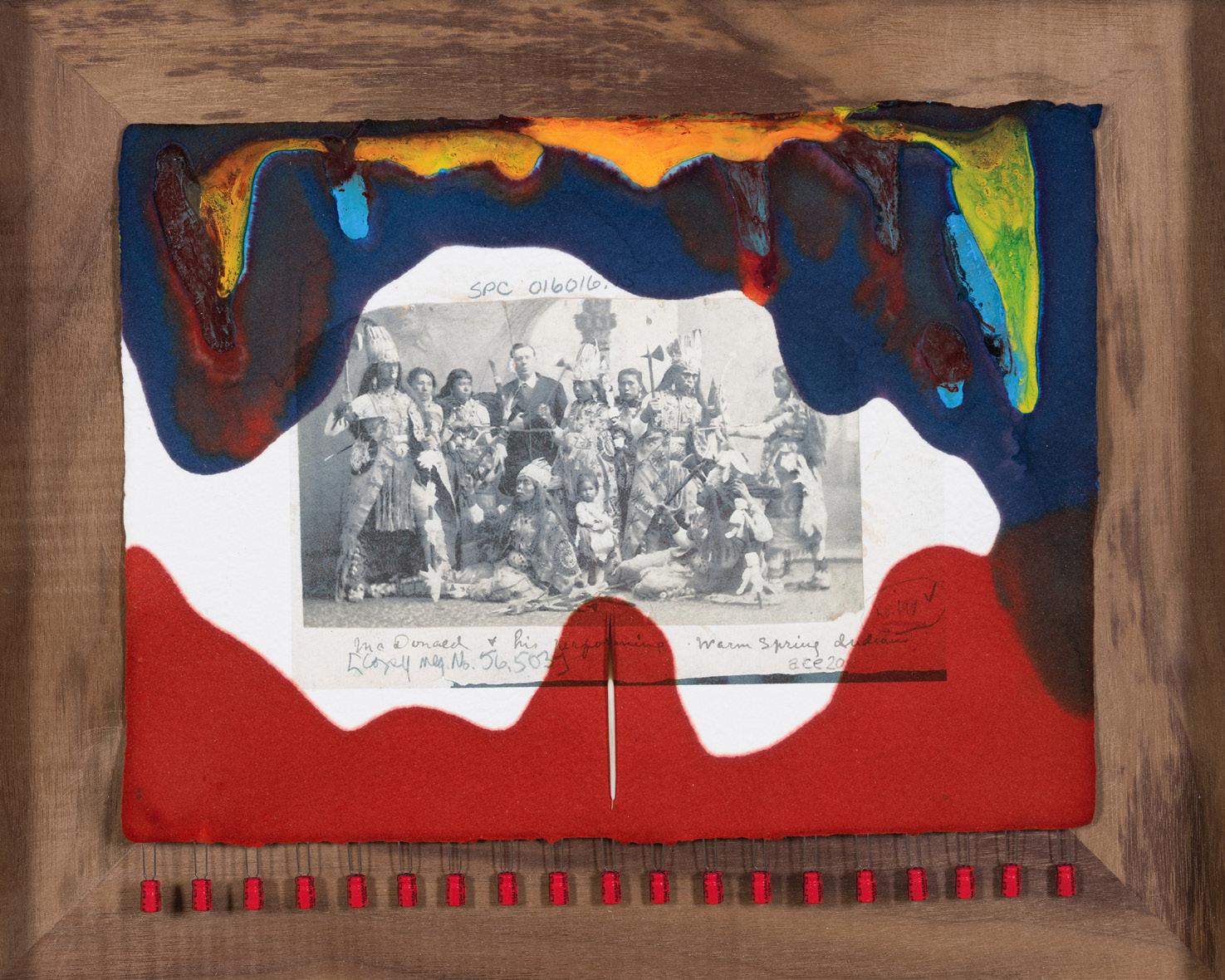

Enactment

direct digital print, acrylic, capacitors, porcupine quill on handmade paper, signed and dated 2020

7 1/2 × 9 1/2 in, 19.1 × 24.1 cm

P RO v ENANCE

Collection of the Artist

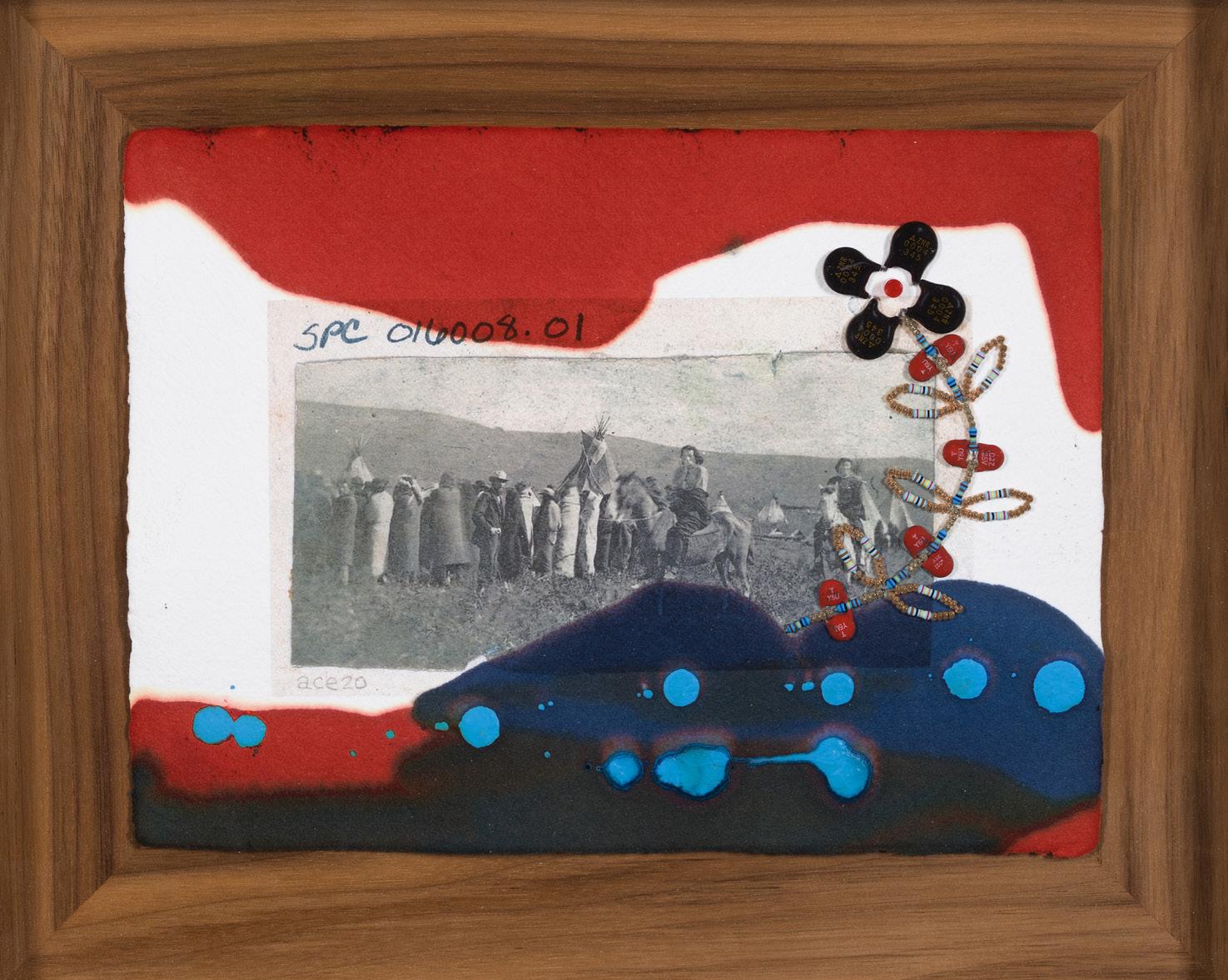

Barry aC e often uses images from digital repositories as a source material upon which to build his compositions for his smaller paper works. Archives, such as the Smithsonian Museum’s, provide scans of daguerreotypes, plates and photographic prints from the era of documenting what was termed “The Vanishing Race,” as colonial interests advanced west ward suppressing culture and overtaking Indigenous territory.

In Enactment, under the image of a dance troupe, the caption reads “McDonald & his performing Warm Spring Indians.” At that time, acts like Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show and George Catlin’s Indian Gallery would tour North America as well as Europe. At the same time as these performances were popular with white audiences in both the United States and Canada, ceremonial and other performances for and with the community, were outlawed. These types of performances were one of the few legal ways Indigenous people could enact their culture and retain, as well as transmit, knowledge.

Coadjute is a verb meaning to work together cooperatively. The image in the work titled Coadjute documents a community gathering, with most of the group positioned with their back to the camera. Ace perceives the configuration as “Indigenous people coming together to protect themselves against colonization that has pushed them to the cusp of cultural change.”

The archival image in Black Gold is marred by a dark aberration that migrates from the top to the bottom of the portrait of an Indigenous man. Possibly caused by a scrape in the emulsion on the glass plate negative, for Ace the mark resembles a smear of oil, signify ing the expropriation of Indigenous land for fossil fuel, a “premonitory image of things to come.”

The works are embellished with electronic components in Ace’s signature style. In Coadjute and Black Gold they form flowers that reference the traditional beadwork seen in Great Lakes material culture. In Enactment, the sharp end of a quill points to a small Indig enous child in the centre of the tableaux and to the future that lies ahead; the capacitors fixed to the bottom edge underscore the technology shift that child, in its lifetime, will wit ness. On all the works the dripping quality of the paint alludes to “a history that is becoming shrouded like a curtain falling on the scene.”

PRICE : $ 1,800

1958 –

Barry Ace 1958 –Coadjute direct digital print, acrylic, capacitors, resistors, light-emitting diode, glass beads on handmade paper, signed and dated 2020 7 × 9 1/2 in, 17.8 × 24.1 cm P RO v ENANCE Collection of the Artist PRICE : $ 1,800

Barry Ace 1958 –Black Gold direct digital print, acrylic, capacitors, resistors, light-emitting diode, glass beads on handmade paper, signed and dated 2020 9 1/2 × 7 in, 24.1 × 17.8 cm P RO v ENANCE Collection of the Artist PRICE : $ 1,800

Barry Ace

1958 –

Bloodline Triptych (#3, #4, #6)

digital output, capacitors, resistors, light-emitting diodes, beads and acrylic on paper, signed and dated 2020 7 × 15 in, 17.8 × 38.1 cm

P RO v ENANCE

Collection of the Artist

i n the Bloodline t riptyc H Barry Ace employs multiples as a strategy to alter assumed associations when viewing an historical image of an Indigenous man. Influenced by Andy Warhol’s merging of the aesthetics and tactics of advertising with modern art, Ace states, “I repeat the image to make it familiar, in effect, less threatening.” Composed of ceramic capacitors and a stem of resistors, the simulated beadwork of a flower motif remains the consistent embellishment on each part of the triptych. The other constant is a stroke of red paint on the right side of the image, an abstracted exclamation point that calls out for the viewer’s attention. In each repetition, the man in the portrait looks straight at the camera lens, challenging the colonial gaze.

The visual citation of the Pop Art aesthetic has been an ongoing strategy in Ace’s work. He developed the “Super Phat Nish” (spn ) persona as a trickster figure at once “humorous and ironic” yet with a “subversive subtext that levels cultural critique against dominant narratives.” Works from the 2005 solo exhibition Super Phat Nish (curator: Cathy Mattes) toured as part of Playing Tricks: Barry Ace and Maria Hupfield (curator: Ryan Rice) at the American Indian Community House, New York City. As well, works were acquired for national and international institutional collections including North American Native Museum (nonam ) in Zurich, Switzerland, Crown Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (C irna C ) and the Canada Council Art Bank. In the Art Bank’s 2022 exhi bition, Looking the World in the Face (curator: Amin Alsaden), the spn persona makes an appearance in the work Cashing In. With this work as well as with Bloodlines, Ace strategi cally appropriates Pop Art conventions to “indigenize normative settler imagery.” In doing this Ace aims to “reclaim stereo-typical representations” while pointing to the absence of Indigenous voice and positive representation in dominant popular culture and iconography.

Each work measures 7 × 5 inches.

PRICE : $ 2,000

Barry Ace

1958 –Bloodline Triptych (#1, #5, #8) digital output, capacitors, resistors, light-emitting diodes, beads and acrylic on paper, signed and dated 2020 7 × 15 in, 17.8 × 38.1 cm P RO v ENANCE Collection of the Artist Each work measures 7 × 5 inches. PRICE : $ 2,000

Barry Ace

1958 –

Bloodline #7 / Jiimaan (Canoe) / Tekahionwake (Pauline Johnson) Triptych

direct digital print, acrylic capacitors, resistors, light-emitting diodes, glass beads, electronic connector component on paper, signed and dated 2020 7 × 19 in, 17.8 × 48.3 cm

P RO v ENANCE

Collection of the Artist

a portrait of an unidentified Indigenous man is at the centre of this triptych that posi tions historical images in a dialogue with each other. His gaze is direct, his body anchored between the simulated beadwork of a flower motif and a dashed stroke of red paint. To the left is an iconic image of Tekahionwake, also known by her Christian name of E. Pauline Johnson, the renowned Canadian poet and entertainer of mixed Settler (English) and Indig enous (Kanien’kehá:ka: Mohawk) ancestry. Her mother immigrated from Britain, her father was a hereditary Chief. Born in the 19th century, she began her life at Six Nations reserve,

a tract of land near present day Brantford, Ontario that was given to the Haudenosaunee for their alliance with the British Empire during the American Revolutionary War. As an adult, she travelled across the newly formed Dominion of Canada many times to perform her poetry for white audiences. On the paperwork Ace has stitched a quill and feather to reference her role as a writer as well as make a visual node to her book, Flint and Feather, published in 1912. The image on the right is of a pair of Chippewa (Anishinaabe) women in a jiimaan (canoe). Between them sits a young child as well as a baby in a tikinagan, the cradleboard that Anishinaabe, as well as many other First Nations, carried their infants in. The jiimaan is made of wiigwaas (birch bark), the traditional material used to wrap around the wood frame of a canoe. The embellished flower, made of electronic components, as well as the paint stroke motif is echoed in all three paper works. The triptych speaks to how, in many archival images of Indigenous people, the sitter was unknown, remaining name less in the archive; yet if they had significance to European culture, and like Johnson could perform in both worlds, they could be known. Their names were deemed important and recorded for posterity.

Each work measures 5 × 7 inches and 7 × 5 inches.

PRICE : $ 2,000

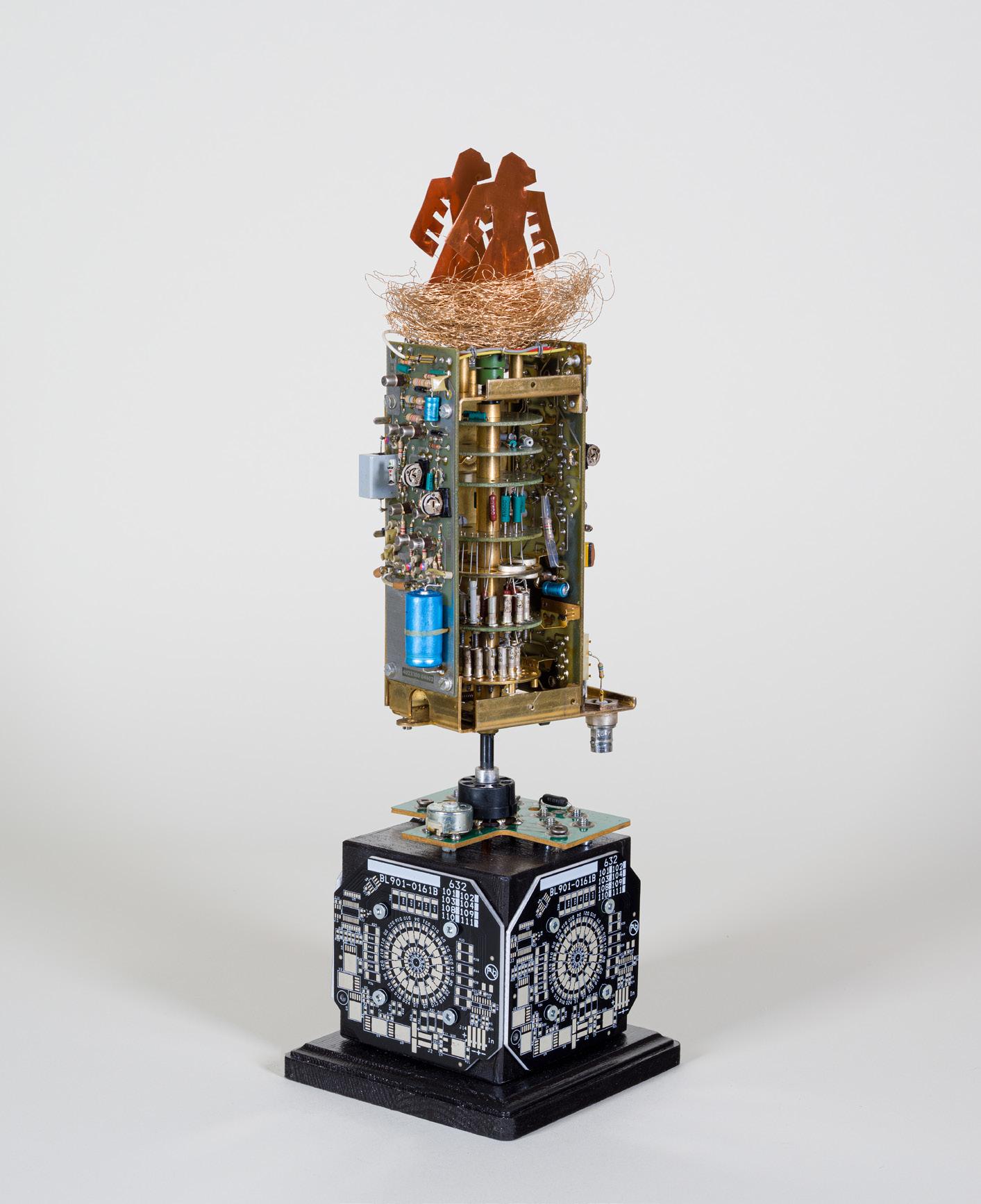

Barry Ace

Nesting Bneswak (Thunderbirds)

oscilloscope electronic component, copper, bronze wire, circuit boards, acrylic, wood, on verso signed and dated 2022 16 × 5 1/4 × 5 in, 40.6 × 13.3 × 12.7 cm

P RO v ENANCE

Collection of the Artist

t he t hunder B ird and the Eagle are birds that figure prominently in Anishinaabe cos mology. Each has an important role: the Thunderbird maintains the balance between the skyworld and underworld, the Eagle communicates with the Creator. Both are symbols for protection and prayers. In Nesting Bneswak (Thunderbirds) and Nesting Mgizwak (Eagles) the sacred birds rest as mating pairs in the nests made of bronze wire. Their outlines are cut from copper, a metal with spiritual importance as it is said to be the blood of sacred spirits for the Anishinaabeg.

In each work, the nest sits atop an attenuator component which is part of an oscilloscope, an instrument used to display, interpret and test electrical voltages. When testing a circuit board, the attenuator allows for the adjustment of sine waves from an incoming signal ensuring that an electrical current is moving through without obstruction or overwhelming the circuitry with too high a load. By using this instrument, a malfunction can be located. For Barry Ace, the assemblage of electronic components, with the circuit boards attached on the base, becomes a metaphor for measuring the functioning state of a culture. Coloni zation, as well as ongoing prejudicial policies and legislation, have negatively impacted First Nations people living both on and off the reserve, including those who live in urban environ ments. The works are “urban-like representations” of the nesting habits of these powerful birds. Ace states, “instead of mountain tops and tall trees, the nests are built on the vertical oscilloscope attenuator components that resemble skyscrapers where the thunderbird and eagle might rest.” With the increased Indigenous migration to city centres, maintaining a connection to one’s culture can be tenuous. The Nesting works “reimagine rural representations transporting the protective birds into an urban environment” to provide stability and cultural cohesion despite a changing landscape.

PRICE : $ 7,500

1958 –

Barry Ace

–

Nesting Mgizwak (Eagles)

oscilloscope electronic component, copper, bronze wire, circuit boards, acrylic, wood, on verso signed and dated 2022

16 × 5 1/4 × 5 in, 40.6 × 13.3 × 12.7 cm

P RO v ENANCE

Collection of the Artist

PRICE : $ 7,500

1958

ENCODING CULTURE II THE WORKS OF BARRY ACE