DESIGNED T O LA S T

REIMAGINING THE FUTURE OF STATE HOSPITALS

Brian Giebink

AIA, NCARB, LEED AP BD+C, EDAC Behavioral Health Practice Leader

Brian Giebink leads HDR’s behavioral health design studio, bringing a deep understanding of current research and trends to inform the design of innovative, research-based mental health facilities that enhance the patient experience. Giebink’s projects span the world, holding roles in planning, design, and consulting for inpatient, outpatient, community, and educational facilities.

A frequent guest speaker, Giebink has been invited to events and conferences across the country, including the Institute for PatientCentered Design Innovation Summit where he presented his team’s award-winning behavioral health patient room design. Giebink also works with manufacturers to design and evaluate furniture and accessories for behavioral health environments. He is a member of the FGI 2026 Health Guidelines Revision Committee focused on behavioral health design and has been recognized nationally for his contributions to the field.

Senior Medical and Forensic Advisor, National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors

Michigan Department of Health and Human Services Medical Director for Behavioral Health and Forensic Programs

Adjunct Clinical Professor of Psychiatry, University of Michigan Medical School

Debra A. Pinals, M.D. serves as the director of the Program in Psychiatry, Law, and Ethics, as an adjunct clinical professor of psychiatry at the University of Michigan Medical School and is a clinical adjunct professor at the University of Michigan Law School. Dr. Pinals is board certified in psychiatry and forensic psychiatry, and is a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine.

Dr. Pinals has served as the assistant commissioner of forensic services, and the interim state medical director for the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health.

Dr. Pinals has worked as a forensic psychiatrist and public mental health policy advisor for approximately two decades, working and consulting across state hospitals and community systems, including architectural projects for improved spaces that promote recovery and safety.

Kyle Bauman-Burr AIA, NCARB Architect

As a behavioral health architect, Kyle develops imaginative and insightful solutions for highly complex problems requiring deep analysis and technical consideration. Specializing in medical & mental health environments, he is responsible for designing, planning and constructing projects across diverse care settings, scales and complexity. Leveraging a strong understanding of people and space, with a deep knowledge of healthcare trends, he integrates evidence-based practices into the design of therapeutic environments, enhancing the quality of patient care and well-being.

Former patients, care providers, staff, and others gathered at the historic Northampton State Hospital in Massachusetts in 2000 as artist Anna Schuleit Haber played J.S. Bach’s “Magnificat” throughout the old hospital — a work she called, “Habeas Corpus.” Three years later, in response to her work at Northampton, Schuleit Haber was asked to commemorate the closing of the Massachusetts Mental Health Center. While researching the location, she noticed how few psychiatric patients received flowers, while so many visitors were carrying flowers into the community hospital next door. Her installation, “BLOOM,” blanketed the floors of the Mental Health Center with 28,000 live flowers and filled the halls with recorded ambiance of the hospital's past life. Schuleit Haber's work in these decommissioned hospitals at the turn of the millennium marked a significant shift in perspective.

We are moving in a direction that is shuttering old perceptions of mental health and opening new doors towards recovery, life, and positive energy.

Our new approach is one of acceptance and resilience.

Many changes have occurred throughout the history of state hospitals in terms of treatment approaches, care models, community perception, and available research.1 2 However, the design of state hospitals has remained largely unchanged for the past half-century. We’ve learned a great deal in the past decade alone, with new research and technology to improve safety, promote better patient outcomes, and empower a more satisfied workforce. The built environment should embrace these advancements to improve outcomes and a state’s fiscal bottom line.

This publication examines several topics related to behavioral health, mental health, and state hospital systems to uncover new approaches to state hospital design and reimagine the standard approach. We consider national policy and funding while drawing upon inspiration from international design approaches that support better outcomes. In addition, we have incorporated insights from people with lived experience, including service users, frontline staff, and department leadership.

By reimagining state hospital design, we aim to inform solutions and inspire conversations that change perspectives regarding the delivery of better outcomes while balancing efficient use of state resources.

The care for people with serious mental illness has a checkered and interesting history. Although people with mental illness were historically cared for primarily by families or turned away from their homes for poor houses and jails, in the 1700s, psychiatric hospital care became more specific to large institutions—which sometimes held thousands of patients at a time. Advocacy for better conditions led to refined settings, with the 1800s seeing architectural design geared toward efficiently housing large populations in facilities on large farms outside of cities, where psychiatric patients could work the land. 3 Over time, even these locations became fraught with scandal for warehousing, unsanitary conditions, and overuse of restraint to manage people with complex behaviors. Exposés and other challenges led to the closure of several institutions around the U.S. and the world. 4

Patient populations in these hospitals have also evolved. Medications for psychotic disorders became available in the early 1950s, and separation of some populations into different types of care settings became more common. For example, during the early 1900s, in a state psychiatric setting, populations would have included people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, neurological movement disorders, medical conditions such as syphilis (that, at the time, had no treatments and resulted in neurological and psychiatric symptoms), seizure disorders and people who were developing dementias as they aged, as well as people with mental illnesses like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

In addition, the state-managed psychiatric hospitals have also long held “forensic populations” caught between criminal and juvenile justice systems and mental health services, for whom safe community settings were not available. 5

In the U.S., many events have shifted the role of the state psychiatric hospital, including the development of a complex system of short-term acute psychiatric hospital care built into general medical hospitals or freestanding private psychiatric hospital settings. State hospitals significantly downsized between the 1950s and 1970s in an era of de-institutionalization, both due to the ability to treat people with medications and efforts at the federal level to transition to smaller community mental health centers rather than large institutions. Other policies, laws, court cases, and political drivers also created these shifts, including recognition of the rights of people with mental illness to live in their communities unless there was a compelling government interest for them to be involuntarily hospitalized and the availability of community resources to help support their community living through social security and other means.

Today, state psychiatric hospitals house a more complex population that has typically experienced other aspects of the psychiatric system before ending up in a longer-term hospital stay. The people in these facilities typically have serious mental illnesses like schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder withand without-psychosis, borderline personality disorder, antisocial personality disorder, and co-occurring substance use disorders and/or intellectual and developmental disability disorders, traumatic brain injury, dementias (or the neurocognitive disorders), post-traumatic stress disorder and other conditions. Very often, state hospitals are the place where the forensic population continues to be committed by courts, either related to competence to stand trial or findings of not guilty by reason of insanity. Increasingly in the U.S., beds within state hospitals are housing these forensic populations. Because of the nature of their conditions, legal backgrounds and the evolving use of the space in these facilities, there is a need for hospitals to have design that is both clinically informed and flexible. Additionally, there is a robust body of research showing that people in state hospitals typically have long and complex trauma histories, and thus their care needs to be trauma-informed and sensitive to these issues. 6 7

Because people in state hospitals are typically admitted under some court commitment order, 8 their length of stay may relate more to their legal status than to their actual clinical needs. Courts often send people to state hospitals who may not need a full hospital level of care. Because of the legal overlay, some individuals need to be discharged when their legal status shifts or a criminal case outcome creates a change in the basis for their commitment. People may be committed, for example, for evaluations that are time limited in nature, or for restoration to competence to stand trial if involved with a criminal court.

In most instances, there is an option to have someone stay in a state hospital for longer periods through what is known as a civil commitment mechanism. That involves generally proving in court that the hospital is necessary for treatment and safety purposes. Individuals with complex presentations sometimes remain in state hospitals for years. Although the average length of stay has shortened since the time of institutional-only care, there are generally cohorts that stay six months or less, and then there are, within any state, a not insignificant number of patients who remain in state hospitals for more than a decade.

State hospitals need access to pharmacy and pharmacy services to help take access to medications seriously and eliminate any barriers to delays. Technology such as pyxis machines and strategies for medication accountability including that of controlled substances will continue to be important in hospital design.

Hospitals have learned more about managing COVID-19 outbreaks and are better prepared for similar challenges in the future. One lesson is that diverse patient groups may require separation from larger groups.19 Large wards of 24-28 beds with limited staff support increases the challenges of sub-dividing or isolating patients safely and effectively while still preserving dignity and connection. Newer facility designs carefully consider flexible unit sizes and the ability to subdivide units, but overall large unit sizes and low staff-topatient ratios remain common practice to maximize funding and operational efficiencies.

One of the challenges of our time is the gap in needed community-based services, which can make it difficult to discharge people from state hospitals.9 Although many people in a state hospital could live in a community setting, there may be no setting for them to transfer into, thus creating a bottleneck on the hospital units.

Community settings can be difficult to develop for populations of people who have been institutionalized. While community integration has been successful in various parts of the world, such as the Geel program in Belgium, many communities in the U.S. struggle with reintegration. There is often a great deal of unwarranted stigma and fear about people with mental illness. It creates a pattern of “NIMBYism,” or the phenomenon of “not in my backyard,” making it difficult to develop sufficient places for people to live in their communities.

Because lengths of stay can be extended in a state hospital, and discharge to a community setting can be challenging for people who have become more dependent on institutional staff support, it is imperative that state hospital patients do not lose their skills of managing themselves in a community setting. Programming designed to foster a parallel to community living can be helpful in rehabilitation services for people with serious mental illness. This type of programming also requires the right type of physical spaces to make this work best.

State hospitals are constantly under pressure to comply with regulatory requirements. Rightfully so, hospitals are required to be in compliance with the federal requirements set forth in the Medicare Conditions of Participation (CoP) in order to receive Medicare/Medicaid payment. Site surveys by regulatory bodies such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and The Joint Commission are used to assess compliance with federal health, safety, and quality standards that will assure that the beneficiary receives safe, quality care and services.10

While compliance is essential to meet quality standards and protect patient and staff safety, facilities often struggle to maintain a current standard of care in a rapidly evolving industry with limited funding available to make improvements. Many state hospitals operate on razor-thin operating margins due to undercompensated or uncompensated care and limited state funding. In recent years, states have allocated more funding for capital projects to improve or replace existing state facilities; however, the long term success of these new facilities relies on continued funding to support ongoing operations and maintenance for the facility lifecycle. Many states are dependent on biannual state budget cycles with frequent shifts in political agendas, making it difficult to align long-term operating expenses with current funding mechanisms. Design elements shouldfactor in sustainable features that require efficiencies to assist with operational budgeting.

Many state hospitals have increased the number and percentage of patients who are committed by courts for forensic purposes, such as those found not guilty by reason of insanity of incompetent to stand trial. Because this population flows often from jails to the hospital, the environment must make the transitions easy. Access to vehicles from law enforcement as well as access to ambulances for transport, and local connections to medical hospitals are important. Movement within the facility must also be driven by protocols and may have limitations for some patients whose legal status or clinical presentation limits full access and autonomy. Thus activities may need to take place on units and in centralized spaces in local areas of the hospital or in centralized larger areas for people across units.

As we look toward the future of state psychiatric hospitals, we consider the challenges and societal idiosyncrasies of the past while embracing new treatment methodologies, best practices, and emerging technology to reimagine state hospital design. We consider improved longevity, necessary flexibility, increased efficiency, embedded technology and improved safety within state hospitals. We reconsider the centuries-old de-facto location of state hospitals and new expectations for the quality of the environment. The future of state hospitals looks different than the state hospital design of today. A new and evolving approach to state hospital design will increase efficiency, improve staff satisfaction, improve patient outcomes, and ultimately help shift the paradigm for the care of people with mental illness in our communities.

Technology is transforming the way service users engage in care. Through the use of tried-and-true technology and emerging technology, patients, caregivers, and staff can engage in the recovery process in new and meaningful ways.

Direct line of sight, continuous observation, and frequent checks on patients have been used for centuries to ensure safety of all users in the care environment. While safety is paramount, these considerations have driven the planning and design of state hospitals: How can staff see as many patients as possible from one location? How can we locate patient bedrooms as close as possible to the nurse station to reduce steps? How can we design to remove visual barriers to see patients constantly?

These questions often lead to solutions that locate staff in the center with a panopticon-like feel. As we start to embrace new technology embedded in concepts of relational security, we can start to see a shift in the way units are designed and care teams operate that promotes more person-to-person interaction, a sense of trust and respect, and ultimately a safer and more therapeutic environment.

Many modern technologies increase patient safety and influence the design of the built environment. Data rich, digital technology allows staff to identify behavioral health risk early, enabling care teams to make smarter and more efficient decisions.

Real-time patient location and movement technology allows staff to know the location of each patient, where they are going, and how fast they are moving. Staff can be alerted when readings are outside of the normal range.

Contactless, non-wearable biometric monitoring allows staff to remotely monitor patients without entering bedrooms, giving a heightened sense of autonomy and empowerment to patients.

Artificial intelligence can be used to identify and alert care team staff to minor variations in biometrics, movement, habits, and other behavior. When these variations are detected early, staff can engage the patient with appropriate therapeutic interventions to prevent escalation, elopement, or harm.

AI can also improve clinical efficiency. Some studies claim more than six minutes of clinical time is saved per patient by embracing AI.

It is well recognized the people within state hospitals most often have complex histories of trauma, either as adults or as children during critical developmental years, or both. Care environments must therefore be “traumainformed”21 that help maximize a sense of safety, security, predictability and respect as well as foster autonomy and personal choice. This can be incorporated into design elements (e.g., individual room choice of temperature or lighting, welcoming imagery and art and signage, safe and quiet spaces for relaxation and self-calming for staff and patients, minimal noise pollution).

Emerging technology can be integrated throughout care settings in many ways to promote empowerment and reduce stress.

Studies have shown that poor sleep is a common complaint in behavioral health facilities. Poor acoustics and lighting significantly influence sleep. In a 2022 study, researchers found that sleeping with even a tiny amount of light can have health consequences.11 Poor sleep leads to fatigue and increased feelings of distress and disturbance. Similarly, lighting conditions impact well-being, task performance, and motivation.

Several hospitals across the U.S. and Europe use lighting systems that mirror circadian rhythms to improve sleep among patients. Lighting systems focused on improving sleep can positively impact a patient’s mood, behavior, and response to treatment.

Circadian lighting that mimics the time of day can improve sleep cycles, improve patient wellbeing, shorten recovery time, and improve staff performance.12 13 14

Interactive technology allows service users to engage in meaningful activities in a safe way, bringing a sense of purpose and accomplishment to their day.

Interactive projection technology allows users to play an instrument, play a game by themselves or with others, or encourage movement and positive distraction.

Interactive touch screens give patients safe access to therapeutic activities such as drawing, coloring, listening to music, viewing artwork or scenes of nature, and playing games to build social connection. Staff controls allow each facility to customize the technology as appropriate for each patient.

Sensory rooms are commonplace in most mental health settings. Multi-sensory environments stimulate senses through light, sound, touch, and smell and can present stimuli in passive and active interaction.15 Integration of technology can aid in the sensory experience by providing integrated sensory input that can be customized to each user.

All of these technologies discussed aid in the recovery process by promoting patient empowerment, autonomy, a sense of ownership, and opportunities for safe self-expression. Thoughtful integration of technology will improve care facilities and influence the fundamental planning and design considerations of state hospitals.

Due to their complexity and constraints, we often see over-prescriptive spacial design facilities, planning for only the initial use of the space. Without greater consideration to how spaces can flex and adapt over time, they may eventually become underutilized or unutilized once it can no longer serve its initial function. In many cases, these spaces with quality real estate within the building are abandoned due to unsafe conditions or begin serving trivial purposes such as bulk storage, placing a costly burden on facilities to maintain unused space

Designing facilities with flexibility in mind is essential for adapting to changes in treatment, staffing, and operations without requiring significant renovations. Effective space optimization and flow are critical. Planning multiple program communities in a state hospital affords greater flexibility in sub-dividing patient populations and increases long-term flexibility as patient needs change. Colocating frequently used spaces, such as bringing treatment and therapeutic spaces closer to patient units, or adding decentralized staff respite areas close to patient units, can aid in minimizing travel time and enhancing operational efficiency. Multi-purpose spaces can serve various functions, accommodating changing program requirements. Exploring a more vertical design, where expansion upwards is symbiotic with expansion outwards, makes efficient use of space by reducing extremities of the building, helping minimize sprawl, and allows greater choices in site location. Additionally, designing patient areas that allow access to fresh air and foster self-navigation, both horizontally and vertically, reduces the reliance on staff for escorting patients.

Adaptable rooms and functionalities are vital components of flexible design. Multi-use rooms with adaptable layouts and utilities allow for easy conversion between different functions as needs evolve. Employing a modular design with universal room infrastructure and features enables them to support multiple uses.

Treatment spaces must include space for individual therapies, group therapies, activity therapies and possible biological treatments, including induction or infusion centers for administration of newer medication treatments such as safe spaces for treatment of depression, trauma or substance use disorders.

Patient bedrooms themselves requires an increased level of flexibility. In many instances, bedroom units are designed to accommodate sub-clusters of two to four beds to occasionally separate patients from the general milieu. However, these four-bed sub-clusters frequently end up serving only a single patient with complex needs resulting in bed blocking. Providing bedrooms in a highacuity sub-cluster, each with a dedicated living space, allows greater flexibility and prevents blocking beds. The living space can be designed to convert into additional bedrooms to increase flexibility in the future.

The building's infrastructure must also be designed to support these adaptable rooms. This includes HVAC systems such as Variable Refrigerant Flow (VRF) that allow for individual room temperature control, accessible utility access above ceilings for easy maintenance and future modifications without disrupting patient activities, and service columns with strategically located access panels for shutting off utilities to individual rooms. Future technology integration should be considered by incorporating oversized data and electrical capacity. Technology components that can be easily added or removed, such as telehealth equipment for virtual consultations, ceiling-mounted sensors, and tamper-resistant fixtures, should be utilized.

Integration of technology can further enhance spatial flexibility. Utilizing telehealth technology connects patients with providers remotely, which is especially useful when on-site staffing is reduced. Automating patient monitoring through the use of AI-powered camera systems or wearable technology for vitals and location tracking reduces reliance on visual monitoring by staff.

Increased flexibility allows rooms to be easily converted to different uses. This adaptability reduces the need for major renovations or rebuilding, thereby minimizing long term costs. Additionally, adjustable room features can enhance patient comfort and well-being, and the facility can accommodate future advancements in technology and healthcare delivery models, ensuring a future-proof design. Consideration should be given to the initial capital cost for adaptable features and infrastructure. Security and privacy must also be carefully managed through thoughtful design and protocols to ensure patient safety.

Universal room features should include adjustable lighting to control brightness and color temperature, moveable wall systems with high sound attenuation for easy reconfiguration, and privacy controls for views and visibility. Individual climate control systems and access to natural light with controllable blinds are essential for creating a comfortable environment. Safe doorways with two-way egress and visibility managed by patients and staff can help with safety and privacy.

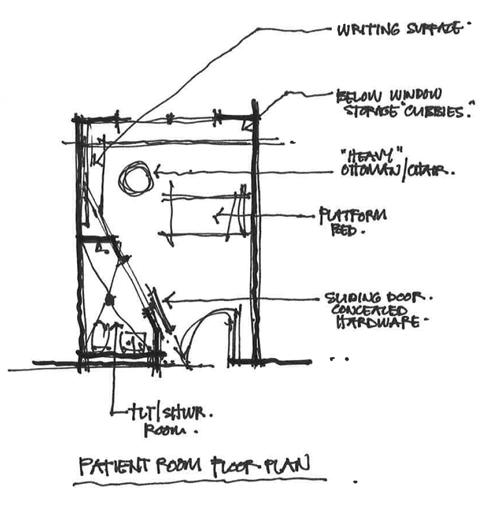

We explored a new design for a patient room that takes into account many of the criteria that together, create a place for healing, for a design competition sponsored by the Institute of PatientCentered Design. Our solution, One Haven, is an uplifting, restorative environment that empowers patients to take active ownership of their behavioral health wellness journey while maintaining a safe and secure environment for all users.

Peer-reviewed journals, case studies of existing behavioral health facilities, behavioral health experts, and family members of past behavioral health inpatients were interviewed to gain important perspectives, and inform the design.

We incorporated strategies to promote safety for all in every facet of the design –from fixtures, to furniture, to finishes–and to prevent harmful behaviors.

Creating connections to nature was emphasized through a large window, as well as a patient-controlled digital artwork display containing multiple views of natural landscapes. Further, a 4-inch opening complying with FGI guidelines allows patient-controlled access to fresh air.

Providing patients an appropriate level of control and autonomy is essential to empowering them in their rehabilitation journey and conveying a sense of respect.

Designing for minimal staff necessitates creating systems and environments that support operations with fewer personnel. Leveraging advanced technology and AI to provide patient monitoring and tracking could be one such way to alleviate this strain on staff. Wearable technology, such as smartwatches or wristbands, are utilized to monitor patient location within the facility, track vital signs like heart rate, blood pressure, and oxygen levels, and detect falls to alert staff to potential injuries. These same wearables could provide automated reminders and notifications to help patients manage appointments, medication schedules, and other important activities. AI-powered camera systems could further enhance monitoring by recognizing harmful activities, facilitating secure building access through facial recognition, and monitoring room occupancy using infrared heat signatures to maintain privacy where cameras are not appropriate. Integrating

these systems could provide real-time alerts to staff when a patient needs assistance or intervention. They could additionally allow patients increased autonomy and freedom of movement through integration with secure building access systems, allowing patients to self-navigate. Lastly, virtual telehealth technologies and robotics that transport telehealth devices can facilitate virtual consultations with healthcare providers, reducing the need for in-person visits and further easing the burden on staff.

Operational efficiency can be achieved by designing staff workflows that allow for adjustable staffing models, enabling tasks such as food service and cleaning to be outsourced when necessary. Implementing standardized processes across all hospital locations facilitates staff performance consistency and reduces variation in the quality of care.

Staff- and technology-based design considerations improve staff efficiency by automating tasks and providing real-time data, allowing staff to focus on providing a higher-level care. Enhanced patient safety can be achieved through continuous monitoring, helping identify potential health risks and provide alerts to staff when a patient is unable. Increased patient autonomy empowers patients to manage their care and navigate the facility more freely, while reduced staffing costs result from improved efficiency and automation.

While technology has its benefits, privacy concerns must be mitigated through robust security measures and clear communication with patients regarding data collection and usage. Technology dependence necessitates reliable backup systems and comprehensive staff training for troubleshooting. Accessibility options should be provided for patients who may not be comfortable or able to use wearable technology. Ethical considerations are also crucial, ensuring a balance between patient autonomy and safety, and that technology is used responsibly and ethically.

Prioritizing positive work spaces and staff needs in state hospitals is essential for fostering a supportive and productive work environment, particularly when designing for minimal staff. To achieve this, it is crucial to replicate home-like environments within the facility. Staff break rooms and respite spaces should be comfortable and familiar, featuring varied seating options like high-top tables, couches, and comfortable chairs. Using calming color palettes and natural materials, ensuring access to daylight and nature views, and providing soundproofed private spaces for relaxation, phone calls, or small group discussions can significantly enhance staff wellbeing. Additionally, well-equipped kitchen facilities for meal preparation that go beyond the basic microwave contribute to a more pleasant and home-like atmosphere.

Offering a range of break rooms and respite areas in convenient locations throughout the hospital is important for accommodating staff needs. Smaller break rooms near units can provide quick breaks and decompression, while larger, centralized break rooms with comfortable seating, dining areas, and potentially media or entertainment options can serve as main hubs. Additional amenities often found desirable in workplaces should also be considered: on-call rooms with hotel-like comfort for staff needing to stay overnight, fitness facilities for cardio, weight training/exercise, on-site or subsidized childcare services for staff with children, and dedicated educational and collaborative spaces for training, meetings, and team discussions. When staff amenities cannot be located on site due to financial or space constraints, consideration should be given to the facility’s proximity to nearby amenities. While some amenities are better when provided on site, numerous amenities may be provided through partnerships with nearby fitness centers, restaurants, hotels, and other community resources.

Connecting staff with nature is another vital aspect in design. Easy access to outdoor spaces such as landscaped courtyards, gardens, patios with seating, and walking paths through park areas can offer restorative benefits. Incorporating biophilic design elements into the building like abundant natural light through windows and skylights, views of nature from break rooms and work areas, and the use of natural materials like wood and stone further supports staff well-being.

A supportive and comfortable work environment can improve staff morale and well-being, reduce stress and burnout, and lead to happier and more engaged employees. High-quality amenities can also increase staff retention, making state hospitals more competitive employers. Additionally, a well-rested and supported staff is better equipped to provide compassionate and effective patient care. Investing in staff well-being can yield long-term cost savings by reducing turnover and burnout-related issues.

While improved staff amenities may pose challenges such as ongoing maintenance of outdoor space or identifying space within existing hospitals, prioritizing staff needs through thoughtful design and amenities is crucial for creating a resilient and efficient environment.

When considering future solutions for state hospitals, location plays a critical role in determining workforce availability, recruitment, and transportation time to the facility. Urban centers and rural locations offer distinct advantages and challenges that directly impact the facility design and operation.

Urban locations have the benefit of population density. Generally, a greater number of qualified professionals live in urban settings, making it easier to attract and retain a qualified workforce. Fewer patients and families are required to travel long distances to reach a state hospital or step-up, step-down care, which can greatly enhance a patient’s response to treatment, family involvement in care, and likelihood of follow-up care. While urban locations generally have higher land value compared to rural settings, facilities in urban areas are likely closer to amenities and utilities, which may offset costs associated with land acquisition and reduce initial capital cost.

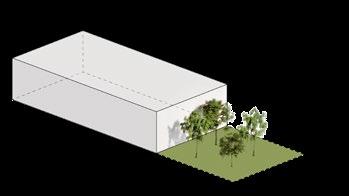

Conversely, rural locations often have the advantage of space. Facilities may benefit from large expanses of outdoor space with unobstructed views of the countryside and offer more personal space per patient. They may also provide a more therapeutic atmosphere removed from negative external stimulation that can often be distracting and increase stress. Rural locations more commonly offer therapeutic external stimulation such as views of nature, birdsong, and a more intimate connection to natural weather events such as wind and rain.

One consideration is to locate larger facilities in urban areas where patients and qualified professionals are proximate and locate smaller facilities in rural locations that require fewer staff. Mirroring facility size with population balances supply and demand of resources, which strengthens the state’s long-term investment in a new facility. Because states may have more than one facility,

providing opportunities for interconnected systems and spaces can help facilitate connectedness and efficiencies.

Accessibility is crucial for facilities in both urban and rural areas. They should be easily reachable for patients and their families, with careful consideration given to travel times and transportation options. Proximity to the workforce is another important factor, especially in urban areas where facilities can be located near professional populations and colleges to facilitate recruitment and retention. Proximity to local amenities can both support facility staff and attract workforce.

Designing patient spaces to reflect the typical living environments of the local population helps create a more familiar and comfortable atmosphere. Additionally, incorporating staff amenities such as on-site childcare and housing options in rural areas can address recruitment challenges.

The benefits of strategic location choices and thoughtful facility design include improved staff recruitment and retention, enhanced patient care, and a move away from large, remote facilities. A network of smaller, strategically located facilities can provide more efficient care in rural areas and reduce transportation burdens on patients, families, and staff. Larger facilities should be situated in urban areas to maximize accessibility and staffing advantages.

However, there are challenges to consider. The cost of urban land can be high, making land acquisition and construction more expensive. Rural locations may require additional investment in infrastructure to support new facilities. Balancing the need for familiar, comfortable environments with the need for efficient, centralized services is essential to creating effective state hospitals that meet the diverse needs of urban and rural populations.

Creating quality therapeutic environments involves designing spaces that transition away from institutional cues to those that embody salutogenic principles reinforcing wellbeing, social connection, restoration, connection to nature, and normalization. Exterior design should avoid large, flat facades typical of institutional buildings, instead drawing inspiration from residential architectural design. Varying textures and materials with subtle detailing can help to break up large expanses of exterior wall façade. Strategic use of windows for natural light—drawing cues from buildings built prior to the widespread use of artificial lighting such as Kirkbride hospital designs—not only improves aesthetics, but also creates a far more welcoming and less intimidating atmosphere.

With interiors, designers and facilities should consider greater use of familiar, aesthetically pleasing materials to mitigate the sterile feel of traditional healthcare settings. Historically, cleanable, durable, safe, and sanitary finishes have had a distinct, artificial look and feel, with many originally made for correctional settings. While many durable finishes and fixtures have improved, the next evolution is a residential appearance that maintains the same durability and safety. With extensive material sciences innovation coming to market over the last decade, notably within fabrics and textiles, more highquality options are available. Natural materials like wood and stone, along with soft fabrics can make patient rooms and common areas feel more comfortable. Spatial layouts should resemble social and living spaces found in community centers, apartments, and homes. Common areas should be designed to resemble living rooms, open-concept kitchens and dining areas, and approachable patios to encourage social interactions and provide a sense of normalcy. Flexibility and adaptability are key considerations. Modular construction techniques can be utilized to allow for future expansion, contraction, and renovation of the facility as needs change. Many

individuals' first few weeks of therapy may be spent not addressing their primary symptoms, but instead coping with the stress of a new and unfamiliar environment, delaying effective treatment. Mimicking home-like environments will aid relaxation and support an earlier start to effective treatment.

Benefits of such a design approach include a reduction in the institutional stigma often associated with state hospitals, improved patient comfort and well-being through familiar and welcoming surroundings, and enhanced staff morale due to a more comfortable environment. Furthermore, a flexible and adaptable design ensures that the facility can meet evolving healthcare needs.

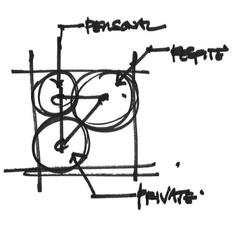

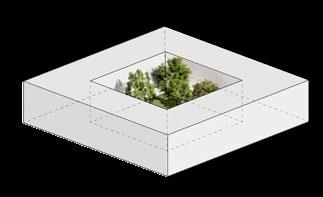

Relational security is a fundamental tenet of increased safety in mental health settings. It affords a greater sense of trust and respect between patients and staff and offers patients a greater level of autonomy by enabling freedom of movement. Increasing freedom of movement and privacy is crucial for improving patient experiences and outcomes in mental health settings. Moving away from traditional institutional layouts where patients feel constantly watched can significantly enhance patient comfort, increase patient engagement, and reduce stress. Removing barriers such as dedicated care team stations reinforces patient-staff interaction and has demonstrated efficacy without sacrificing safety. Alternative layouts such as those that feature central courtyards with patient rooms wrapping the perimeter can provide a more welcoming and less intrusive environment while permitting patients frequent and direct access to the outdoors. Spaces must offer various levels of privacy, ranging from individual bedrooms to semi-private common areas and public outdoor spaces, to accommodate the unique needs of the patient. To aid staff in maintaining safety without reducing freedom of movement, technology such as location tracking wearables and AI-powered camera systems monitor patient safety throughout the facility.

Increasing patient autonomy is another vital component of this design philosophy. Allowing patients safe yet independent access to amenities like kitchens, activity rooms, group therapy rooms and outdoor spaces empowers them to control their daily routines. Creating opportunities for supporting positive levels of engagement in an activity can be done with design, such as front porch concepts at bedroom alcoves and softening transition thresholds between spaces. These elements not only foster a sense of ownership and independence, but also encourage participation in therapeutic activities. Similarly, encouraging patients to personalize their living spaces can create a sense of ownership and belonging and help in rehabilitation goals of community living.

led g Dock

One of the biggest operational challenges for state hospitals is providing patients safe and secure access to the outdoors. The therapeutic benefits of being connected to the outdoors cannot be overstated.

Research tells us time and time again that access to the outdoors improves patients reduces stress and improves patients' response to treatment.

While many solutions offer access to the outdoors, patients are often limited due to physical constraints and staffing. Inspired by international approaches to mental health design, it is evident that frequent, self-regulated access to the outdoors is possible and a key goal for state psychiatric hospital care in the future.

As patient autonomy is increased, we also need to consider the integration of intuitive wayfinding. As HDR’s Wayfinding Principal Jeff Zoll notes, “When visual and sensory cues lack strategic thought and integration in design, it can lead to disorientation and confusion. It's not simply about signs; it's about understanding how people interact with the space and designing it to facilitate their movement.” 16 He suggests to first consider how different individuals experience a building and imagine what it would be like to experience it for the first time. We must understand human behavior and human factors to anticipate the physical and cognitive challenges users may face as they navigate this environment, while understanding the complex histories patients may have and their own visual and cognitive processing differences. Secondly, utilizing unique, recognizable, and memorable colors and patterns that repeat throughout a building creates a sense of familiarity and comfort for people in unfamiliar environments. Landmarks, such as art and sculptures, reinforce intuitive direction and add elements of positive distraction to the user experience. Lastly, universal symbols for words and phrases, or pictograms, ensures an equitable user experience regardless of linguistic and cognitive ability. Using consistent colors, patterns, shapes and forms provide wayfinding cues that are not reliant on any one feature or written language and literacy. When text is necessary, utilize highly legible fonts with sufficient contrast and appropriate sizing for viewing at a distance.17

These interventions can help improve patient well-being, as increased freedom of movement, privacy, autonomy, and ease of wayfinding contribute to a more positive healing experience. The need for staff supervision can be reduced, allowing them to focus on more meaningful interactions rather than routine monitoring tasks. That said, balancing patient safety and autonomy requires careful planning and operational buy-in to ensure security is not compromised as a result of increasing access to movement in various spaces. Utilizing technology requires robust data protection and clear communication with patients about how the data is used. Staff may require additional training, ensuring that they are equipped to handle changes in patient care dynamics.

When a patient has progressed in their treatment journey and is prepared for a return to the community, they must be met with a network of well-planned step-down care and support services. Too often, this crucial component is missing from the continuum of care. In the reverse, a patient in need of a higher level of service may experience gaps in steps between levels of treatment that can be too large or to be effective, placing a burden on the individual, their family, and the state’s mental health system.

Building out a robust continuum of care within each state is essential and can be accomplished in a number of ways. One method for states to strengthen connections between step-down services is to combine and expand their treatment services, offering a full spectrum of care through a coordinated care network. This approach encompasses a step-up, step-down model of care and a comprehensive network that includes families and supportive care systems who can move easily between the community system and the state hospital. Community systems increasingly will encompass crisis care through a dedicated psychiatric emergency room or a local crisis stabilization unit. Residential programs are another natural fit, providing supervised living environments for patients transitioning back to the community. Many patients will have been supported through these community placements prior to

hospitalization and return to them upon discharge. Utilizing state hospital space may include expanding into outpatient treatment and providing resource space for the greater community. Partial Hospitalization Programs (PHP) and other day treatment programs help provide an appropriate step between residential and outpatient treatment and some state hospitals will have spaces for these types of programs or some means of accessing them during passes to the community. Providing outpatient individual and group therapy services as well as community social programming at the state hospital site will bring more traffic to the hospital, allowing the public to become familiar with the site and reducing stigma attached to the state hospital. Including wellness spaces for public use, such as a recreation center, private and group quiet rooms for study and relaxation, training centers and other community social gathering spaces can change the narrative of the hospital to a comprehensive center for wellness, for all levels of need. This allows facilities to become the community champion of mental health and wellness and establish themselves as an integral part of the communities’ daily life.

Leveraging community partnerships and private organizations' ability to provide quality care at all levels of the continuum of care is another solution for a state.18 State hospitals are often an essential component to the integrity of a state's mental health program, yet they cannot be

the end-all, be-all, nor should states be expected to own and operate all facilities and services within continuum. 5

Establishing a network of providers in the community and incentivizing collaboration from community partners can lead to a robust continuum of care that is accessible and available to all patients and families at any step of their journey.

The benefits of an integrated care continuum are significant. Patients can seamlessly transition between different levels of care based on their needs, ensuring continuity of treatment. This robust support system can help reduce readmissions by providing continuous care and support, thus preventing patients from returning to the hospital after discharge. Furthermore, wellness centers can play a crucial role in improving public health by promoting mental health awareness and reducing the stigma associated with seeking help.

Expanding spaces to offer services along the continuum of care at state hospitals through integrated services and community engagement not only ensures seamless patient transitions and reduces hospital readmissions, but also promotes public wellness and the facility’s financial stability.

Subsidizing less profitable services with revenue from services with higher profit margins can position a state with a financially viable solution.

Engaging the community by offering lower acuity outpatient services, promoting volunteering opportunities for the community in residential programs, and conducting educational outreach programs can foster community support and integration of expanded mental health services.

Long-term success of state hospitals requires allocating funding strategically. State mental health programs are frequently faced with the paradox of capital expense versus long-term operational funding. There is no onesize-fits-all approach as funding cycles differ by state— some state facilities and capital improvements operate on a two-year budget cycle, while others have long-term commitments. Some state hospitals operate under the state behavioral health authority while other states have a separate building and facilities division, which can complicate budget allocation.

Longevity and long-term financial alignment is crucial for the success of state hospitals. Many of the state hospitals in the U.S. are nearly or more than a century old and are struggling to remain operational and provide safe, therapeutic treatment to some of the most vulnerable in our communities.

Varying strategies for funding have been tried, including allocation of legislatively appropriated capital funds during a major political push for improvement, to a few examples of for-profit organizations partnering with states to overcome the longevity challenge many hospitals face. In one instance, a state provided the capital to build a new hospital with an agreement from a private organization to provide ongoing operations. In other examples, states bear the cost of a new facility and privatize some of the operations afterwards. Each operational approach has its challenges, but states aim for financial stability for management of its state hospitals while recognizing that costs generally increase even when population numbers have decreased. This is in part related to the complexity of patient populations shifting and the increasingly monitored and regulated landscape of inpatient state psychiatric hospital care.

We live in a rapidly changing world. The facilities we design for some of our most vulnerable members of society with serious mental illness and emotional disorders must align with current treatment methodologies yet be flexible to withstand the test of time. State hospitals built today will be caring for patients and serve as a workplace for many staff for the better part of the 21st century. A whole person approach to health will be commonplace—mental health, physical health, and social determinants of health will be seen as equal and undifferentiated. Similarly, communities will embrace mental healthcare the same way we have embraced caring for those with cancer and physical disabilities. We must embrace change by rigorously understanding the shifting paradigms in mental health perception, acceptance, treatment, and demand so that state hospitals will be built to last.

Each state is in a unique position with their mental health programs. While the path forward is not a one-size-fits-all solution, most of the considerations are applicable to all states in one form or another. Many opportunities exist to improve state hospital design and much needs to be done on many different levels to achieve this vision for the future.

Change is hard to embrace. Communities often resist change, and new mental health facilities often impart a major change to a neighborhood, community, and region. Strategic communication has a tremendous role to play in community education, awareness, acceptance, and ultimately ownership of a new state hospital.

Funding is limited for state hospitals. State hospital outcomes rely heavily on mental health services outside of the hospital, whether it be transitional housing, step-up and step-down programs, justice diversion programs, or community support — and state funding alone cannot provide a full continuum of services. Leveraging community partnerships and private sector support is essential to maintaining a robust continuum of care in the community. Building that support through advocacy groups, private sector, and non-profit organizations can supplement care provided in state hospitals.

Aligning state hospital solutions with demand is crucial. States must truly understand the demographics intended to be served in a new facility, as well as the makeup of staff to support operations, maintenance, and clinical care. This requires each state to develop a deep understanding of the population and the specific health and mental health needs of each county to inform changes to the state hospital program. Services at a state hospital will likely cover a range of ages of patients, some will incorporate care for children, but all will serve adults ranging in age from 18 years old to older adults. A thorough market demand analysis, facility needs assessment, and comprehensive statewide master plan will paint a clear picture of the specific population, location, and gaps in the continuum of care that need to be addressed.

Every community and patient is unique and therefore requires a unique solution. Programs, treatment models, operational demands, funding, and facility design must push boundaries beyond current thinking. It’s time to move beyond antiquated models and challenge the status quo on each new state hospital endeavor. Doing so requires commitment from a diverse group of stakeholders and thought leaders with unique perspectives and backgrounds. Legislators, clinicians, advocates, policy makers, regulatory agencies, payors, operators, architects, people with lived experience and facilities teams must work together to define the future of state hospitals.

Shifting the perception of mental illness has been an ongoing challenge for decades. Deinstitutionalization of the mid-20th century led to a great divide between mental health supply and demand that left many stranded without appropriate care and a growing stigma around those suffering with no place to go.

We must stand up for the most vulnerable to pave a brighter future in mental health. Raising awareness, building partnerships, challenging the status quo, and promoting new approaches to treatment can influence change in mental health and it has been done at small scales throughout the world. Together, we can influence a new approach to state hospitals that will have a lasting impact for generations.

1 Geller J. L. (2000). The last half-century of psychiatric services as reflected in psychiatric services. Psychiatric services (Washington, D.C.), 51(1), 41 – 67. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.51.1.41

2 Pinals DA, Hepburn BM, Lutterman T. The State Hospital. In, Trivedi HK, Sharfstein SS. Textbook of Hospital Psychiatry, Second Ed. APA Publishing, Washington D.C. 2023

3 Parry MS. Dorothea Dix (1802–1887). Am J Public Health. 2006 Apr;96(4):624 –5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.079152. PMCID: PMC1470530.

4 The Rise and Demise of America’s Psychiatric Hospitals: a Tale of Dollars Trumping Sense; Jeffrey Geller, M.D., M.P.H. https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2019.3b29

5 The Vital Role of State Psychiatric Hospitals; Joe Parks, M.D., Alan Q. Radke, M.D., M.P.H. www.nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/The%20Vital%20Role%20of%20 State%20Psychiatric%20HospitalsTechnical%20Report_July_2014(2).pdf

6 Koolschijn, M., Janković, M., & Bogaerts, S. (2023). The impact of childhood maltreatment on aggression, criminal risk factors, and treatment trajectories in forensic psychiatric patients. Frontiers in psychiatry, 14, 1128020. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1128020

7 Stinson, J. D., Quinn, M. A., & Levenson, J. S. (2016). The impact of trauma on the onset of mental health symptoms, aggression, and criminal behavior in an inpatient psychiatric sample. Child abuse & neglect, 61, 13 –22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. chiabu.2016.09.005

8 Trend In Psychiatric Inpatient Capacity, United States and Each State, 1970 to 2018 (nasmhpd.org); www.nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/2023-01/Trends-inPsychiatric-Inpatient-Capacity_United-States%20_1970-2018_NASMHPD-2.pdf

9 https://archive.ada.gov/olmstead/olmstead_about.htm

10 State Operations Manual SOM Appendix A (cms.gov); www.cms.gov/regulations-and-guidance/guidance/manuals/downloads/ som107ap_a_hospitals.pdf

11 Light exposure during sleep impairs cardiometabolic function | PNAS; www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2113290119

12 Shine a Healing Light: Circadian-Based Lighting in Hospitals (medscape.com) www.medscape.com/viewarticle/893225#:~:text=Almost%2050%20patients%20 have%20been,better%20sleep%20and%20reduced%20fatigue

13 Lighting's critical role in healthcare - CIBSE Journal; www.cibsejournal.com/technical/lightings-critical-role-in-healthcare

14 Lighting and Human Wellbeing, S. Higuchi; https://shorturl.at/ylmj6

15 Fava, L., & Strauss, K. (2010). Multi-sensory rooms: Comparing effects of the Snoezelen and the Stimulus Preference environment on the behavior of adults with profound mental retardation; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2009.08.006

16 3 Principles of Intuitive Wayfinding for Inclusive Space | HDR (hdrinc.com); ww.hdrinc.com/insights/3-principles-intuitive-wayfinding-inclusive-space

17 A. J. Paron-Wildes; Interior Design for Autism from Adulthood to Geriatrics; https://www.wiley.com/en-us/ Interior+Design+for+Autism+from+Adulthood+to+Geriatrics-p-9781118680254

18 Pinals, D. A., & Fuller, D. A. (2020). The Vital Role of a Full Continuum of Psychiatric Care Beyond Beds. Psychiatric services (Washington, D.C.), 71(7), 713 –721. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201900516

19 Pinals, D. A., Hepburn, B., Parks, J., & Stephenson, A. H. (2020). The Behavioral Health System and Its Response to COVID-19: A Snapshot Perspective. Psychiatric Services, 71(10), 1070 –1074. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.202000264

20 Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services; Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 57; Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (US); https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207201

21 Saunders KRK, McGuinness E, Barnett P, Foye U, Sears J, Carlisle S, Allman F, Tzouvara V, Schlief M, Vera San Juan N, Stuart R, Griffiths J, Appleton R, McCrone P, Rowan Olive R, Nyikavaranda P, Jeynes T, K T, Mitchell L, Simpson A, Johnson S, Trevillion K. A scoping review of trauma informed approaches in acute, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care. BMC Psychiatry. 2023 Aug 7;23(1):567. doi: 10.1186/s12888-023-05016-z. PMID: 37550650; PMCID: PMC10405430.