March 2023 hayandforage.com

Horse owners have their say on hay pg 10

Time for interseeding pg 12

Self-fed ensiled forage reduces labor costs pg 14

Cocktail forage mixes: What do dairy cows think? pg 20

Published by W.D. Hoard & Sons Co.

SAVE ON QUALITY HAY AND

3.9% FOR 36 MONTHS OR 5% CASH

ON KRONE DISC MOWERS, TEDDERS, ROTARY RAKES, AND ROUND BALERS

EQUIPMENT!

FORAGE

Find your Krone Dealer

DISCOUNT!

He started with busted bales and five cows

Not growing up on a farm, Bill Stevens has built a 20,000-acre hay operation in Washington’s Columbia Basin. The business consists of several vertically integrated entities.

MANAGING EDITOR Michael C. Rankin

ART DIRECTOR Todd Garrett

EDITORIAL COORDINATOR Jennifer L. Yurs

ONLINE MANAGER Patti J. Hurtgen

DIRECTOR OF MARKETING John R. Mansavage

ADVERTISING SALES

Kim E. Zilverberg kzilverberg@hayandforage.com

Jenna Zilverberg jzilverberg@hayandforage.com

ADVERTISING COORDINATOR

Patti J. Kressin pkressin@hayandforage.com

W.D. HOARD & SONS

PRESIDENT Brian V. Knox

EDITORIAL OFFICE

28 Milwaukee Ave. West, Fort Atkinson, WI, 53538

WEBSITE www.hayandforage.com

EMAIL info@hayandforage.com

PHONE 920-563-5551

DEPARTMENTS

4

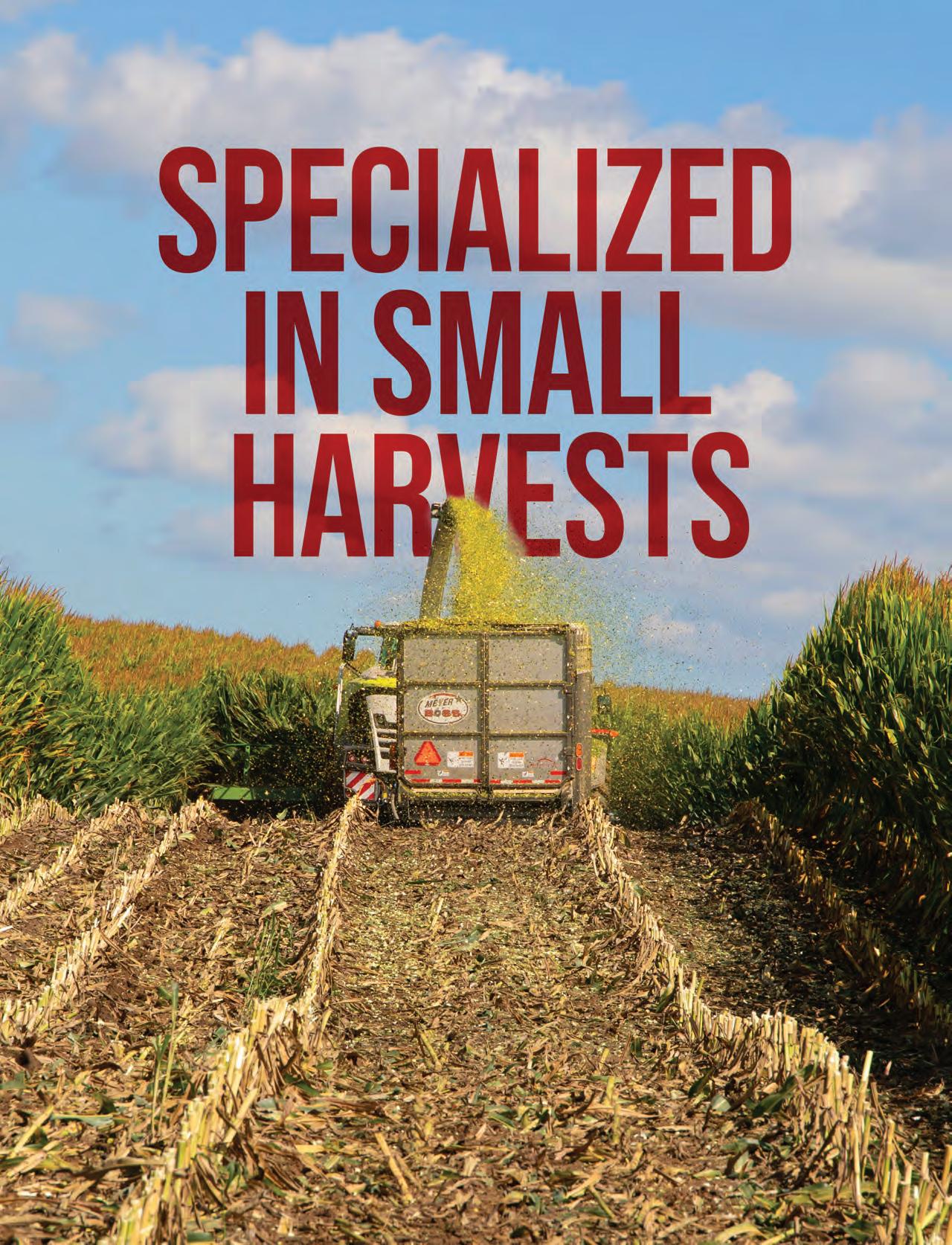

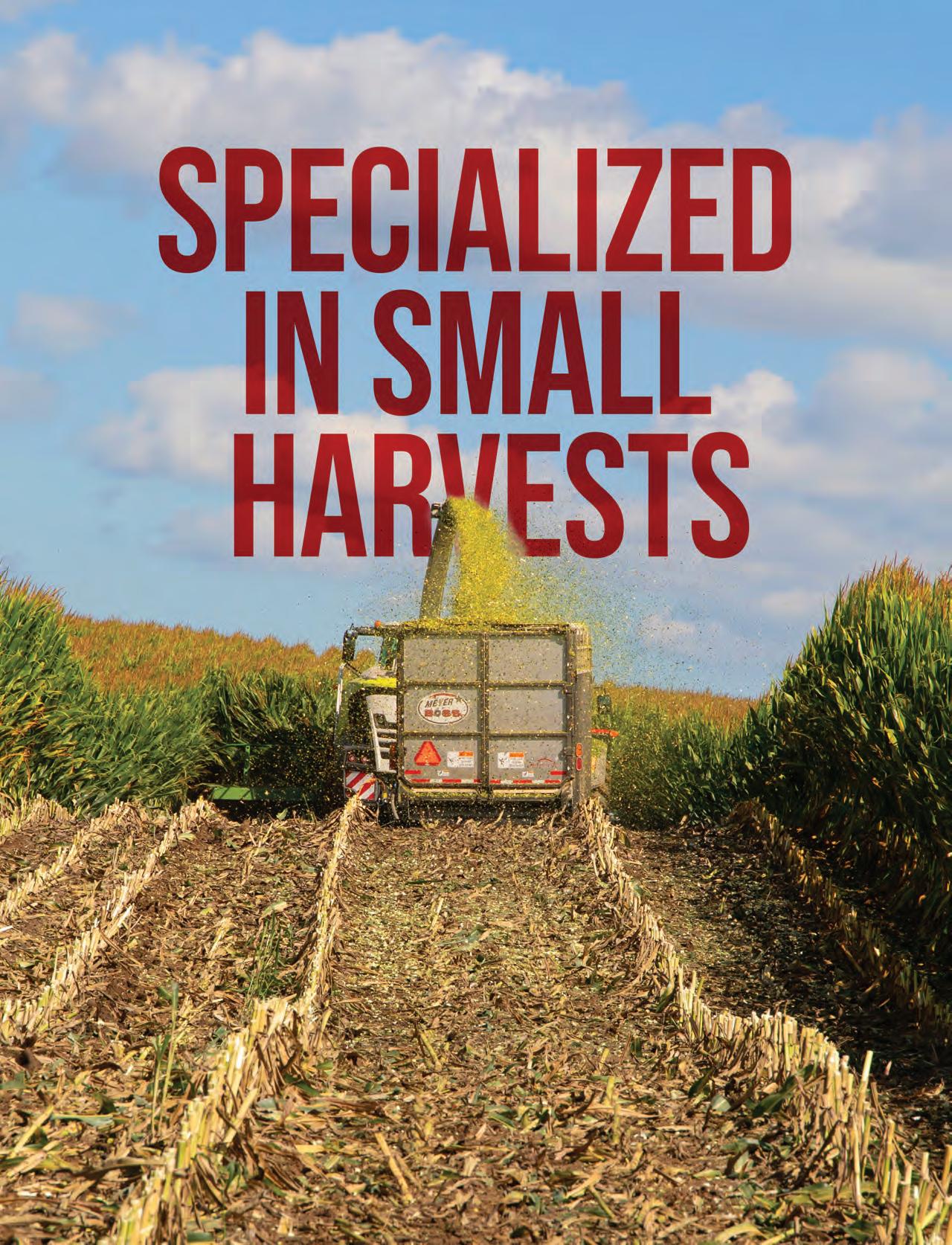

Specialized in small harvests

Silver Streak Ag Services serves nearly 50 clients in northwestern Illinois. The business chops about 5,000 acres and makes up to 6,000 large square bales each year.

Multispecies grazing helps pastures and

Adding sheep or goats to a cattle grazing operation can help control undesirable weeds and adds a new profit center.

25

A red barn, blue skies, and wilting hay. It was a perfect haymaking day for the field demonstrations held last fall at the National Hay Association’s Annual Convention, where the machinery was humming at John Russell’s farm near Pemberville, Ohio. The patriotic barn belongs to Paul Brueggemeier, a neighbor of the Russells.

HAY & FORAGE GROWER (ISSN 0891-5946) copyright © 2023 W. D. Hoard & Sons Company. All rights reserved. Published six times annually in January, February, March, April/May, August/September and November by W. D. Hoard & Sons Co., 28 Milwaukee Ave., W., Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin 53538 USA. Tel: 920-563-5551. Fax: 920-563-7298. Email: info@hayandforage.com. Website: www.hayandforage.com. Periodicals Postage paid at Fort Atkinson, Wis., and additional mail offices. SUBSCRIPTION RATES: Free and controlled circulation to qualified subscribers. Non-qualified subscribers may subscribe at: USA: 1 year $20 U.S.; Outside USA: Canada & Mexico, 1 year $80 U.S.; All other countries, 1 year $120 U.S. For Subscriber Services contact: Hay & Forage Grower, PO Box 801, Fort Atkinson, WI 53538 USA; call: 920-563-5551, email: info@hayandforage.com or visit: www.hayandforage.com. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to HAY & FORAGE GROWER, 28 Milwaukee Ave., W., Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin 53538 USA. Subscribers who have provided a valid email address may receive the Hay & Forage Grower email newsletter eHay Weekly. March 2023 · VOL. 38 · No. 3

6

22

cows

26

4 WEATHERING THE WEATHER 9 SOIL HEALTH’S BIOLOGICAL BASIS 10 HORSE OWNERS HAVE THEIR SAY ON HAY 12 TIME FOR INTERSEEDING

SELF-FED ENSILED FORAGE REDUCES LABOR COSTS 16 CONTROL HAY HEATING BY WRAPPING LOWER MOISTURE BALES 18 FEWER COWS BUT MORE NET INCOME 19

COCKTAIL

MIXES:

DAIRY

DIGESTION ON THE COVER

Photo by Mike Rankin

14

ARE YOU READY? 20

FORAGE

WHAT DO

COWS THINK? 25 THE NEXT FRONTIER: PROTEIN AND STARCH

First Cut

On

The Pasture Walk

Alfalfa Checkoff

Beef Feedbunk

Forage Gearhead

Dairy Feedbunk

9 Sunrise

Soil 12

16

18

19

20

Feed Analysis

Forage IQ

Hay Market Update

34

34

March 2023 | hayandforage.com | 3

Weathering the weather

FOR those in the business of food production, extreme weather events seem to stick to our brains like a tick on a longhaired dog. We just don’t forget . . . ever.

When I think of drought, the years 1988 and 2012 immediately come to mind. The former was the year I finished graduate school and proceeded to job hunt. The growing season began dry and remained that way for weeks, then months. It was a long, hot, and widespread drought. At one point, 45% of the continental U.S. was categorized as extreme drought, and 11 states declared all of their counties disaster areas. The average U.S. corn yield that year didn’t break 85 bushels per acre. Hayfields and pastures were crispy by mid-summer.

I started my career as an extension agent in mid-August of 1988. The crops looked brutal and were starved for moisture. Then, soon after my first day on the job, it started to rain. From that point forward, I was known as the droughtbreaker in my area. Unfortunately, the damage had been done, and there would soon be the typical drought fallout.

In 2012, I was unable to muster any moisture relief, and my reputation waned.

As we head into the 2023 growing season, many growers in the Great Plains and western Corn Belt are praying the year will provide more rainfall than the past few have. The recent dryness has hit cattle and hay country hard.

Even if you don’t farm or ranch in those parched regions, you’ve still been impacted. Hay stocks are at their lowest level since the early 1950s. The nation’s beef cow herd numbers the fewest head since the early 1960s. Replacement heifers are also in short supply, with many more than usual ending their productive lives in the feedlot because grass was short.

By now, if you haven’t got the message that any grazing plan isn’t complete without a drought component, then you’re not paying attention. Having a plan in place that identifies preemptive triggers for action can mean the difference between suffering a paper cut or an amputation.

Cloudier skies ahead?

Governing our weather patterns from year to year is the surface temperature of a relatively small portion of the ocean. We can attribute the recent drought — and many before — to La Niña, which is the name given to a condition when the ocean surface is cool.

“We’ve been locked into a La Niña weather pattern since 2020, and it has been historically long in duration and strength, but she’s just about done,” asserted Matt Makens during the CattleFax Outlook Seminar at the recent Cattle Industry Convention in New Orleans. Makens is a meteorologist and atmospheric scientist with Makens Weather LLC based in Colorado.

The ocean is warming up, he noted. Moisture conditions have already started to improve this winter in previously drought-stricken areas. “By spring, our models suggest that a La Niña will only be about 14% likely, down from the current 60%,” Makens said.

The reverse situation from La Niña is El Niño, which occurs when the ocean surface warms. Both of these dominant patterns are cause for extreme weather in localized regions around the world. The shift from one to another can take months or seasons for the atmosphere to adjust, and there is often a period of neutrality.

Once La Niña bids adieu sometime in late spring, weather conditions will begin to change. “I expect a more neutral-based forecast as the atmosphere begins to catch up with the ocean conditions,” Makens said. “This means we begin to eliminate the extremes of an El Niño or La Niña. Overall, it should be a more favorable summer for moisture compared to the past several years. Other than the Southwest, temperatures are expected to be neutral to cooler than average in pockets,” he added.

Makens’ weather models suggest that there is only a 52% probability that we’ll have an El Niño weather pattern by next fall. He said that if El Niño does get into high gear, expect a lot more rainfall than what a neutral fall might look like.

“I think this is not likely to happen; it’s too quick of a transition,” the meteorologist stated. “El Niño will kick in, but give it some time.”

The overriding theme to Makens’ weather message was one of mid-term optimism, which is a trait inherent in most farmers and ranchers; it has to be for the sake of mental survival. This doesn’t look like a year that will likely be etched in our weather gray matter, but just in case, have a drought plan. •

Happy foraging,

FIRST CUT

Write Managing Editor Mike Rankin, 28 Milwaukee Ave., P.O. Box 801, Fort Atkinson, WI 53538 call: 920-563-5551 or email: mrankin@hayandforage.com

Mike Rankin Managing Editor

4 | Hay & Forage Grower | March 2023

John Deere Dairy Solutions & Support Your animals. Our solutions. Keeping your herd healthy and productive is your top priority. Helping you do it is ours. From tractors, balers and unrivaled dealer support, John Deere has the solutions and support for every need on a dairy farm. Contact your dealer or learn more at JohnDeere.com/Dairy.

HE STARTED WITH BUSTED BALES AND FIVE COWS

by Mike Rankin

SOAP Lake borders Highway 17 to the east and a town by the same name to its south. Basalt cliffs define the lake with water that is said to contain 23 different minerals. Going back to when Native American tribes inhabited this area of Washington’s Columbia Basin, people have come to soak in the healing waters and lather themselves in the lake’s mud to cure what ails them.

About seven miles northeast of Soap Lake on Highway 28, the focus shifts from high-quality water to high-quality hay, which is made possible by the nonhealing irrigation waters of the Columbia River. It’s here that Bill Stevens manages a bevy of businesses that are vertically integrated to make Stevens Hay Farms Inc. successful. The 20,000acre operation and related entities are supported by family members, about 60 fulltime employees, and 20 to 25 seasonal workers.

Stevens’ life story doesn’t include inheritance. He’s a first-generation hay farmer.

“I didn’t grow up around farming at all,” Stevens noted. “I did do some farming work for my uncle. After high school, I went to tech school for electronics, but after I got out, I came back to work at my uncle’s farm for $1,000 a month. After a few years of that, it made me hungry to do something on my own.”

Stevens continued his early life tale, “I made a deal to buy broken bales from my uncle and purchased five beef cows. From those five cows, I just kept growing. My uncle provided me with an education that was irreplaceable,” he added.

Stevens broke away from his uncle’s employment when he was 28 years old and started leasing hay ground. With help from a kind-natured banker, Stevens bought a used tractor, baler, and swather — all with borrowed money. He eventually purchased a used bale wagon, or “harrow bed” as they’re referred to in that region. “I did custom work for other people and any other work I could find to stay solvent,” Stevens said of those early years. “I then started buying some land and eventually bought this farm in the early 1990s, which at that time had about 100 acres, but it wasn’t all irrigated. My cow herd was still growing, too.” Stevens had about 120 brood cows before he decided to sell the cattle to help buy more hay acres. He preferred making hay to caring for livestock. Ever since, the number of owned and leased hay acres have just kept mounting. “I never had a cosigner on a loan, but I got a lot of

6 | Hay & Forage Grower | March 2023

A second cutting of timothy is cut last August. Stevens Hay Farms harvests about 10,000 acres of timothy each year.

help and advice from neighbors along the way,” Stevens said with a tone of appreciation. “I couldn’t have got to this point without them.”

Family and then some

Stevens’ children have all been involved in the operation while growing up and as adults. Kye, his oldest son, heads up Stevens Domestic Hay Sales. He and his wife, Lindsey, who also helps on the farm, recently became new parents. Hay sales within the U.S. include retail feed stores and dairies.

Steven’s oldest daughter, Brynna, oversees the hay harvesting operation. Her husband, Teddy, works on the hay export marketing side of the business. Another daughter, Berlyn, operates equipment when she can but is currently studying to be a veterinarian. “She’s the best machine operator we have,” said Stevens, who also has two younger children, Dezi and Brady, who are just starting to help out.

The base of operations is a 3-year-old office building that’s located among the plethora of machine sheds and haystacks located at the farmstead. To the east of the office is a building that houses Stevens Hay Exports LLC. Stevens is a 50% partner in the 4-year-old export business venture. Jason Gunderson, who has many years of hay export experience, serves as the CEO for the export business but is also involved in all facets of the farming operation. With many moving parts, Stevens emphasized that although there are designated responsibilities, everyone pitches in wherever needed. “Sometimes, our secretaries are out running the balers,” he chuckled.

Clean and green

Stevens Hay Farms will harvest about 10,000 acres of alfalfa and 10,000 acres of timothy in 2023. The region receives about 7 inches of rain per year, so irrigation is a must. Hay is harvested within about a 50-mile radius of home base.

Alfalfa is generally seeded in the late summer with a target to have all new seedings in the ground by September 1. The soil is lightly tilled — more like scratched — before seeding and then planted with a Great Plains no-till drill or an air seeder at a rate of 20 pounds of seed per acre.

Raptor herbicide is applied to new seedings around October 1 to control any weed issues. When asked about the need for a fall herbicide treatment, Gunderson said, “There are so many exporters out here that it becomes a beauty contest. Your hay has to be clean and green to have a chance at competing.”

Generally, alfalfa is cut three to four times per year. In a normal year, cutting begins around the middle of May. Stevens likes to cut alfalfa about every 32 days and finish by the end of August. Stands are kept for four years and then are rotated out of alfalfa for at least three years before being reseeded back to alfalfa. Timothy is used as the primary rotation crop, although sometimes potatoes or dry beans are planted either by Stevens or another vegetable grower.

Timothy establishment is similar to

alfalfa — in the late summer after a marginal stand of alfalfa is sprayed out. Three cuttings are taken the first production year with the final cutting harvested the last half of September or early October. “I like an aggressive cutting schedule for our timothy to achieve high quality and to get it off before leaf diseases become a problem,” Stevens noted.

Timothy stands are kept two to four years, depending on when other weedy grasses begin to infiltrate stands and how long the field had been out of timothy before the new seeding was established.

To keep phosphorus and potassium soil fertility in line, Stevens’ preference is to use dry, composted manure, which he purchases from a local distributor. He will also use manure from a nearby feedlot. For alfalfa, the compost is applied at the time of seeding and after the final cutting each year. Commercial nitrogen fertilizer appli-

continued on following page >>>

March 2023 | hayandforage.com | 7

Jason Gunderson (left) is the CEO for Stevens Hay Exports. Bill Stevens (center) has grown his business to a 20,000-acre, vertically integrated operation. Kye Stevens (right) oversees Stevens Domestic Hay Sales.

Composted manure is sourced from a local provider and is Stevens’ preferred product for maintaining phosphorus and potassium fertility.

All photos Mike Rankin

cations are made on the timothy acres. The farm does all of its own fertilizer and chemical applications.

As one might imagine, the equipment line to harvest Stevens’ volume of acreage is extensive and includes seven John Deere 16-foot self-propelled mower-conditioners; nine Twinstar basket rakes; eight New Holland large square balers, which are traded every year; eight Hesston inline 3-tie balers; and 23 semitrucks. Stingers and New Holland bale wagons are used to pick up bales. Stevens also often calls on custom operators to help with baling and bale transport from the field.

“I like the adjustment options on the basket rakes,” Stevens said. “We can manipulate windrows in a variety of ways.” Hay is usually raked twice, always early in the mornings when there’s still dew.

Vertically integrated

The large pole building that houses Stevens Hay Exports is equipped with two Hunterwood bale presses. The business also has a USDA-certified fumigation facility. A lot of Stevens Hay Farms’ timothy goes to South Korea and Japan. China is their main export partner for alfalfa. “Stevens Hay is the largest organic alfalfa producer for China in Washington,” Gunderson noted. “We produce about 5,000 acres of organic hay each year.”

Gunderson said that being a totally integrated operation has many advantages. “Our export customers like that we grow our own crop,” he said. “It’s also more profitable for us. We have trucks going to the Seattle-Tacoma port every day of the year. The shipping container situation is getting better.”

The knowledgeable hay exporter

“China is a growing alfalfa market,” he said. “West Coast alfalfa is the best in the world. Exports have been strong, but what scares me is that high prices push these countries to look for other options. We may have hit the ceiling on hay prices.”

In addition to export and domestic hay sales, the operation also utilizes a nearby feedlot to take chaff generated from the hay presses and the lower quality hay that sometimes gets made.

A bright future

The growth curve for Bill Stevens’ hay businesses continues on an upward trajectory, although he’s starting to step back and let his trusted family members and employees take the reins. “I look at things more from the 60,000foot level now,” he said.

And why shouldn’t he? It’s been a long road from five cows and paying a discount price for his uncle’s broken bales.

continued, “It’s important to have as many outlets as possible for our hay.

Traditional markets like Japan and South Korea are shrinking. For Japan, the timothy goes to the dairies and beef operations. The really high-end timothy goes to the horse farms. The company also exports some grass straw.

Stevens has a well-positioned management team in place with lifelong experience in the business of making and selling hay. He also has dedicated employees. “I say it every year at our Christmas party,” Gunderson said, “When there’s work to be done, everyone around here just jumps in and goes. That’s the kind of environment Bill has built around here.”

It could also be that there’s something in the water. •

8 | Hay & Forage Grower | March 2023

Trucks take compressed hay bales to the Seattle-Tacoma port every day. Stevens Hay grows and exports about 5,000 acres of organic alfalfa.

Two Hunterwood bale presses operate in the building that is home base for Stevens Hay Exports. There is also a USDA-certified fumigation facility on site.

Bill Stevens is quick to give credit to his uncle and neighbors for providing help and education as he built his business over the years.

Soil health’s biological basis

CAN soil really be considered healthy or unhealthy? Wouldn’t that require soil to be a living entity? How could this be if soil is made up of sand, silt, and clay particles and simply holds water and air as a medium for anchoring plants to the earth?

Well, soil could be considered unhealthy if it no longer performs the essential functions of absorbing water, filtering water to give us clean groundwater, providing nutrients to allow plants to thrive, or decomposing organic materials applied to the land. Indeed, soil can be considered healthy only if it can perform these essential functions that we expect from it. How we manage soil, therefore, allows us personal control for the health of our land. This is a great responsibility that can be rewarding for us and our neighbors.

Measured breathing

When we consider soil a living entity, we can understand that it breathes much like we do. Although soil may be truly living only in the bacteria, fungi, and small animals that reside within the mineral matrix, it acts as a living entity through the multiple functions it performs for the benefit of the earth’s inhabitants. Therefore, the more soil breathes, the more it needs to be fed. The more soil is fed, the more work it can do. We can measure this breathing through soil respiration, which is the exhaling of carbon dioxide (CO 2) from the soil surface.

To standardize this measurement as a soil testing approach, soil is collected, dried, and then rewetted to optimize the balance of water and air for soil microorganisms. Placing the moist soil in a chamber with constant temperature is important, as cold soil doesn’t respire as much as warm soil if all other factors are the same. After only a few days, the amount of CO2 respired can tell us how biologically active a soil sample might be.

Some soils are more biologically active than others. Those samples that are more biologically active can be considered well-fed, highly functioning soils. These soils might be considered health-

ier than those having little biological activity. When a soil has very low biological activity, can it really be considered healthy enough to support a robust plant community that provides us sufficient food, fiber, and ecosystem services?

Standard measures

Because of the sensitivity of soil biological activity to temperature, moisture, and length of time, a standard laboratory approach is needed. With years of experience as a foundational basis, soil-test biological activity (STBA) has become the standard to which other laboratory protocols should be compared. These technical details become important when making recommendations for nutrient management or interpreting the effects of soil management on other ecosystem services.

Soil-test biological activity was recently categorized into a gradient of low and high levels to make nitrogen fertilizer recommendations (see figure above; https://bit.ly/HFG-Nrec).

This gradient of STBA allows producers to make immediate decisions on nitrogen application rate, as well as providing a useful indicator to assess long-term changes in soil health condition when sampled periodically. Since the inherent ability of soil to provide

nitrogen to growing plants is a function of a small portion of soil organic matter turnover, STBA, expresses this vital soil process effectively.

Grass enhancement

Soil-test biological activity has been shown to improve with pasture age. This is due to the accumulation of organic matter near the soil surface with input of roots and their partial decomposition over time.

Return of plant residues or livestock feces also feeds soil microorganisms. Type of soil and environmental conditions can also affect STBA. Therefore, different types of management can either increase or decrease STBA, depending on landscape setting.

Evidence is becoming clear that routine soil testing for inorganic nutrients may need to be supplemented with soil biological testing. •

SUNRISE ON SOIL by Alan Franzluebbers

ALAN FRANZLUEBBERS

80 60 40 20 0 Nitrogen factor (lb N ton -1

The author is a soil scientist with the USDA Agricultural Research Service in Raleigh, N.C. Soil-test biological activity (mg CO2-C kg -1 soil 3 d -1) 0-4” depth

Soil biological activity impacts need for nitrogen 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 Frazluebbers et al., 2022

forage) VL L M H VH March 2023 | hayandforage.com | 9

HORSE OWNERS HAVE THEIR SAY ON HAY

by Krista Lea

IN A recent survey of horse owners, 48% said alfalfa hay was an excellent source of nutrition while 73% said it was too high in protein or overall nutrients (Figures 1 and 2). These results represent conflicting opinions.

Hay producers across the U.S. have experienced a similar disconnect when marketing to the horse industry. As a horse owner and a forage agronomist at the University of Kentucky, I’d like to shed some light on how to market hay to horse owners and tap into this lucrative but fickle market. The truth is that horses come in a variety of sizes, shapes, and uses, and with this much variation comes differences in

nutritional needs as well as owner expectations. To successfully reach this clientele, you have to satisfy both. From a forage quality perspective, horses aren’t all that different than cattle. Energy is typically the most limiting factor, and we need to try to target higher energy hay with horses that require a higher energy diet. Similar to a lactating cow, a lactating horse or a horse doing heavy work is going to require energy and nutrient-dense hay such as alfalfa. But a mature, idle horse will require far less energy.

Gain can mean pain

One significant difference in cattle and horses is the ease at which horses can become over-conditioned. Overfeeding horses can lead to obesity and a

slew of metabolic disorders that can be career- or life-ending. So, horse owners are just as concerned with meeting nutritional needs as they are exceeding nutritional needs.

Unlike most other agricultural species, gain is not always a good thing, and appropriate hay will, in most cases, maintain body condition instead of increase it. For horses, high-quality hay is considered to be free of weeds, dust, and mold, and when fed at sufficient amounts to match intake requirements (usually 1.5% to 2.5% of body weight), meets the nutritional needs of the horse without exceeding it.

The idea of an “idle” animal is also somewhat unique to horses. Most cattle farmers are encouraged to cull any animals that aren’t being productive. But

10 | Hay & Forage Grower | March 2023

Jimmy Henning

Alfalfa hay has its place in a horse diet, just not all horse diets.

because a horses’ value isn’t in their pound of flesh, bigger isn’t better. A horses value is in their genetics, their performance or the work they do. And in some cases, their value is intrinsic; the joy and friendship they bring far outweigh any monetary value they might have.

Beyond nutritional needs, how do horse owners select hay? The same survey that found the conflicting data presented earlier also revealed a few other things that might be beneficial in answering this question. The survey study, which was funded by National Alfalfa and Forage Alliance checkoff dollars, was conducted by researchers at the University of Kentucky in the Departments of Animal and Food Sciences and Plant and Soil Sciences with the goal of better understanding hay-buying preferences of horse owners.

The first group of questions asked whether or not horse owners like to feed alfalfa (or alfalfa mixed hay) and why. Many said they both liked to feed it and didn’t like to feed it, which was probably due to different needs for different horses. For example, I currently have four horses in my barn consuming alfalfa hay: two yearling fillies actively growing, one broodmare near parturition, and one old, very picky retired mare. The rest of my barn, consisting of mostly retired geldings, maintain their body weight quite well on what most hay producers would call low-quality hay — straight grass, slightly over mature, and stemmy. I, too, would be one to answer: Yes, I prefer to feed alfalfa hay, and no, I don’t prefer to feed it. It depends on the horse.

More than price

In another question, horse owners were asked to rank what factors are most important to them when purchasing hay. The factors listed included bale size, quality analysis, cost, dealer reputation, and availability of delivery. Cost ranked first, which was not surprising. But the second most important factor was dealer reputation. It was important to know that friends were satisfied with their hay purchase. Horse owners want to be sure that price reflects the quality of the product, and that the seller is willing to stand behind their hay if there is a problem. All of these were more important factors than a guaran-

teed analysis of the hay. Like many aspects of agriculture, word of mouth is the ultimate advertisement. Every hay supplier that I purchase from simply says, “If they don’t eat it, I’ll come back and get it.” And they have.

Small bales preferred

The third most important factor was bale size. While many hay producers are moving to larger bales for handling and trucking ease, they also need to remember that the end horse user could be a small woman, feeding one or two horses, who would prefer a 40-pound bale she can pick up over a more economical 75-pound bale. Often, there isn’t the space or equipment to even consider 3x4x8-foot large square bale. Horse owners were also asked where they get their hay-buying information. Of the 10 choices they were given, university personnel ranked first. Second was the hay supplier, which was somewhat surprising. This means that horse owners value the hay supplier’s guidance more than most other sources of information, including extension publications, their veterinarian, and the internet. Understanding the needs of the clients and their horses gives hay suppliers a tremendous advantage

because horse owners clearly value their knowledge and guidance. It’s advantageous for hay suppliers to get to know their clients, which is an easy task because horse owners love to talk about their horses.

Most horse owners aren’t nutritionists, agronomists, or money managers. They know their horses and desire the correct feed for them. If hay suppliers and producers take the time to get to know their horse clients (human and horse alike), provide them with the quality of hay they require in a package they can handle, and stand by that product, they will be rewarded with a loyal clientele willing to pay a premium for hay that suits their needs.

March 2023 | hayandforage.com | 11

•

KRISTA LEA

The author is a research analyst and horse pasture evaluation program coordinator with the University of Kentucky.

60% 40% 20% 0% Responses Good source of nutrients Good palatability Excellent value Have always fed it 48% 32% 12% 9%

50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% Responses Nutrient content too high Protein is too high Mold and dust concerns Blister beetle worries 40% 33% 17% 10%

Figure 1. Why do you feed alfalfa hay?

Figure 2. Why do you not feed alfalfa hay?

The author wishes to thank Bob Coleman, an extension equine specialist at the University of Kentucky, for his role in helping develop and distribute the survey.

Time for interseeding

THE Year of the Great Inflation is how many people will remember 2022. Among the numerous things that inflated in 2022 was the price of nitrogen fertilizer. It seems every time the nitrogen price goes up, there is a surge of interest in interseeding legumes in pastures and hayfields. Should times of high fertilizer prices be the only time we think about legumes as a nitrogen source for our pastures?

My experience has been that nitrogen fertilizer hasn’t been economically competitive with legumes in a pasture for at least 40 years. I have already made this point in this column a few years ago. In the 23 years we were on our farm in Missouri, there were only three occasions that we ever used nitrogen fertilizer on a pasture. We are approaching 19 years on the ranch in Idaho, and it has been nine years since any kind of fertilizer has been applied to these pastures. The only time nitrogen has been applied had been as a tag-along with phosphorus being applied as 11-52-0 every three or four years.

Always a benefit

Whether fertilizer is expensive or not, it makes sense to grow legumes in your pastures wherever and whenever it is feasible. A mixed grass-legume pasture provides better balanced nutrition than either a grass or a legume monoculture. Numerous studies have shown superior animal performance with mixtures compared to monocultures. Aboveground plant diversity increases belowground biodiversity to the benefit

of soil health. Many pollinators enjoy legume blooms. Oh, and there is the nitrogen-fixation benefit as well.

Since most pastures around the country are deficient in legume content, it is time to think about how and when to interseed them to gain all those benefits. We have a few options that we have found to be successful in different environments.

Frost seeding is a broadcast seeding method that works well for most smallseeded legumes in regions that have regular freeze-thaw cycles in late winter or early spring. There is often concern about seed-soil contact with this method. If a pasture has been stockpiled for winter grazing and then is strip-grazed, seed-soil contact is usually adequate. If a pasture has all of its fall residual left intact, then dragging the pasture can help get seed down to the soil.

Reliable spring moisture is also a necessity. That can either be as natural precipitation or through irrigation. In an irrigated environment, it is important to make sure to keep the newly seeded area moist. We have seen many overseedings germinate on the natural moisture but then wilt when irrigation is not begun in timely manner.

Go with late snow

Another broadcast method that we have had good success with is seeding on top of a late snow. We don’t like seeding over the long winter snow cover. That type of snow often melts off the top, and broadcast seed can be washed away

with snow melt water flowing across the crusted snow or ice sheet below.

Once the winter snow cover has melted off and the ground has thawed somewhat, that’s when it’s time to be ready for your spring legume overseeding. When you get a new snow cover, get out there and start broadcasting seed. One big advantage of broadcast seeding in this situation is that you can actually see your wheel tracks and do a more uniform seeding job. The darker legume seed absorbs heat and “burrows” down into the snow. Most of these later snows melt from the bottom up. In the process, the melt water typically infiltrates and doesn’t run off. The seed can literally be sucked into the soil surface.

There are some situations where a no-till drill actually makes more sense than broadcast seeding. We generally budget broadcast seeding at $4 to $6 per acre while no-till drilling may range from about $15 to $28 per acre. That is a big cost difference for getting your seed out there, but there are some legumes that establish more consistently when drilled compared to broadcast seeded. Those legumes needing special seeding attention in many environments include both alfalfa and birdsfoot trefoil. I have seeded both of those legumes successfully by the broadcast method but less consistently than most clovers have established over the years.

We also find a no-till drill to be more consistent for irrigated pastures with very low natural rainfall. In this situation, we generally plan to drill the seed within a few days of beginning irrigation. This works very well with any sprinkler system. Broadcast seeding often performs poorly on flood-irrigated ground as seed may wash away with the first surge of flood water.

Legumes are valuable components in almost every pasture situation. In a good part of the U.S., late winter and spring is the seeding season. Get your seed early and get it in the ground in timely manner. •

JIM GERRISH

The author is a rancher, author, speaker, and consultant with over 40 years of experience in grazing management research, outreach, and practice. He has lived and grazed livestock in hot, humid Missouri and cold, dry Idaho.

THE PASTURE WALK by Jim Gerrish

12 | Hay & Forage Grower | March 2023

Mike Rankin

By Paul Schneider Jr., AG-USA (This is a paid advertisement)

We have been fearfully and wonderfully made! When given perfect conditions, our bodies can be quite healthy, yet we know they are able to exist in less than optimal conditions.

Plants are the same way. They are able to survive in far less than optimal conditions, but the resulting biological and nutritional deficiencies greatly compromise a plant’s ability to defend itself against parasitic bacteria, harmful fungi, and insect invasion.

When plants are given optimum living conditions - when they have extra resources to work with, they go from just surviving to thriving.

The fact is, it takes a healthy plant to create a healthy soil. When a plant is barely surviving, its resources are very precious. It must retain most of its resources for building plant structure; little can be spared to feed its microbial partners in the soil.

Health Level One

Mycorrhizal fungi have a vested interest in keeping the plant alive. The very existence of these fungi depends on a symbiotic relationship with the plant, where the plant secretes sugars to feed them, and they, in turn, provide nutrients to the plant.

There is a vast amount of phosphorus in most soils. When phosphorus is not available, plants will sequester sugars to feed mycorrhizal fungi, and they, in turn, are highly effective at making tied-up phosphorus in the soil available, and carrying it to the plant. When it is given water-soluble phosphorus, the plant no longer needs mycorrhizal fungi to make phosphorus available. The plant becomes far less motivated to feed the mycorrhizal fungi, resulting in primary mycorrhizal structures never being established.

Sequestered sugars result in higher carbohydrate levels in the soil. These carbohydrates will help a plant protect itself against soil borne pathogens.

Mycorrhizal fungi also help transport moisture back to the plant. This helps the plant stay green during dry spells. This means more photosynthesis and more manufactured sugars.

Health Level Two

As mycorrhizal fungi increase, they build fungi networks in the soil. The fungi share plant sugars with beneficial bacteria. The fungi actually colonize the bacteria.

The bacteria then help break down nitrogen, making it available to the plant. They “weather” bedrock to extract minerals, which the fungi then transport to the plant. Through all of their functions, these bacteria help increase the immunity of the plant.

Mycorrhizal fungi are all too happy to work together with beneficial bacteria, because by working together they can do more to ensure the survival of the plant, and thus, their own survival.

As fungi partner together with bacteria, the plant is able to build extra proteins on the surface of the leaf, giving the plant much greater protection against sucking and chewing insects

MycorrPlus provides trace minerals that play a key role in protein synthesis. It also helps establish healthy soil conditions that help establish greater mycorrhizal fungi networks in the soil.

Health Level Three

Amino acids are the building blocks of proteins. At level three, mycorrhizal fungi create a mucous layer, a type of sheath, that surrounds fungal hyphae. This provides a

means for bacteria to move around in the soil.

At this level of complexity, the microbes in the sheath are able to digest amino acids, turning them into proteins, saving the plant the need to create these proteins.

Without the mycorrhizal sheath around roots, the plant finds it hard to properly use amino acids to create proteins, resulting in an excess of soluble amino acids in plant sap. This draws sapping insects and pathogenic fungi.

When mycorrhizal fungi help with the work of building proteins, the plant is able to conserve a lot of energy. It uses this energy to produce greater amounts of resistance metabolites. These result in an even greater level of fungal infiltration into the soil.

At level three, nitrogen combines with plant sugars to create fatty lipids. This results in secondary plant metabolites that provide increased immune function against air-borne pathogens

A primary sign that a plant has reached level three of health is that the lipids and proteins create a waxy surface on the leaves, making them glossy.

Numerous MycorrPlus customers have commented that within 6 to 12 months, the leaves of their plants have become glossy. Please call toll-free today and ask for a free information packet or contact our West Coast office!

Conquer Nature by Cooperating with it

Like a center pivot for dryland farmers! Reduces the need for LIME and other fertilizers

MycorrPlus is a liquid bio-stimulant that helps to remove compaction by highly structuring the soil. It creates something like an aerobic net in the soil that retains nutrients and moisture. It contains sea minerals, 70+ aerobic bacteria, 4 strains of mycorrhizal fungi, fish, kelp, humic acid and molasses. $20 to $40/acre.

To learn more, call (888) 588-3139 Mon. - Sat. from 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. EST. Request a free information packet or visit: www.AG-USA.net Organic? Use MycorrPlus-O.

TM

Plus

National office: AG-USA, PO Box 73019, Newnan, GA 30271. (888) 588-3139 info@ag-usa.net West Coast office: Global Restoration LLC, 1513 NW Jackpine Ave., Redmond, OR 97756. (541) 788-8918 wcoast@ag-usa.net

SELF-FED ENSILED FORAGE REDUCES LABOR COSTS

by Nicolas DiLorenzo, Federico Podversich, and Federico Tarnonsky

by Nicolas DiLorenzo, Federico Podversich, and Federico Tarnonsky

THE development of forage harvesting equipment and silage bags has improved and facilitated the preservation of forages as silage. This technique allows us to preserve the excess forage production of the summer to bridge the gap during forage shortages. Additionally, ensiling forages offers a reduced weather risk and allows for greater quality feed compared to dry hay. However, labor and equipment costs can mount as larger volumes of silage are preserved and fed.

Farm labor availability has been on a long-term decline while wages and other input costs continue to rise. This situation pressures ranchers to come up with alternative solutions to keep up with production and profitability. Therefore, cattle producers continue to implement strategies that require less workforce while main-

taining productivity.

One option being explored at the North Florida Research and Education Center (NFREC) is the use of “self-feeding” silage bags. The use of self-fed ensiled forages is a suitable alternative for producers who want to reduce input costs such as equipment use and labor. This is a low-cost approach in which cattle are allowed to eat silage free choice from a silage bag.

The bag is opened on one end with electrified wires running across the opened face of the silage bag. The sides of the bag are also fenced off. This approach can be implemented on a small or large scale and can be used for both growing and mature cattle. While there is no individual control of the silage intake, this free-choice approach system reduces the need for tractors, feed wagons, or diesel fuel. In today’s economy, such savings can be appealing. Nonetheless, there are different aspects to consider when deciding to use a self-feeding silage bag, as farm

situations differ and the feeding operation must be tailored to fit.

Pick a dry site

Silage bags should be located in a well-drained location to avoid excessive mud accumulation. Normally, the location of the silage bag would be dictated by the layout of existing facilities such as feeding yards, but if no infrastructure exists, the preferred area would be an elevated terrain to take advantage of the natural water drainage. In such cases, we recommend to position the silage bag on the slope. Feed animals downslope from the bag so that urine, rainwater, and feces run off away from the face of the silage.

Ideally, the bag should be opened facing south, as this will provide maximal sunlight exposure and keep the ensiled material and the soil surface dry. It is advisable not to place the silage bag under trees. It is also important to fence off the sides to prevent cattle access to the bag. This can be done with

14 | Hay & Forage Grower | March 2023

Researchers at the University of Florida are fine-tuning ways to feed silage directly from a bag. These cows were self-fed during calving season.

an electric fence, taking advantage, whenever possible, of existing perimeter fences to reduce costs.

Maintain adequate feedout

Once the bag is opened, oxygen penetrates the ensiled forage, and this allows yeasts to grow and cause spoilage. Therefore, allow cattle to consume enough material every day so it does not spoil and waste. This is called the face removal rate or daily frontal advance. As a rule of thumb, it is recommended to remove at least 1 foot off the silage face per day in the winter and 1.5 feet during summer so that fresh silage is always being fed.

This rule of thumb may be flexible depending on location and climate. The face removal rate goes hand-in-hand with the number of animals stocked with the self-feeding silage bag. Additionally, the use of heterofermentative inoculants during the ensiling process can delay the growth of yeast once the feed is exposed to oxygen, extending the aerobic stability of the silage.

The easiest way to control cattle’s frontal advance into the bag is with the use of electric fence. Cattle learn quickly how to eat silage from the front of the bag while respecting the hot wire. There are also other more sophisticated options to restrict access to cattle such as hurdles or feeding gates, but those require a greater investment and are harder to manage. However, these options could reduce waste. The gates should be easy to move (many farmers use wheels attached to the structure to push the gates), keeping in mind that cattle should be allowed a fresh portion of silage every day as it is being consumed.

Each day, remove a “slice” of the plastic bag and move the hot wire closer to the face, allowing cattle access to new feed. This can quickly be done by one person, and the tools needed for the daily care are a pocketknife and a pitchfork (to pile up any loose silage in the bottom and push it behind the wire). The savings in time, diesel fuel, and tractor use can compensate for any feed waste generated with this feeding strategy.

Stock appropriately

The ideal stocking rate will depend on the size of the bag, moisture content,

packing density, and face removal rate. Roughly, stocking rate can vary from 50 to 100 head per bag, depending on the animal category being fed. Our experience with the 12-foot bagger used at the NFREC has shown a packing density of around 2 to 2.1 tons per linear foot of bag for corn and sorghum. With that packing density, we have been able to feed at least 45 mature cows. We can remove the previously mentioned 1 foot off the frontal face of the bag to minimize spoilage due to oxygen exposure and continuously offer fresh silage to the animals.

therefore, protein supplementation is required. Without enough protein in the diet, cattle will waste some of the fibrous portion of the feed because the rumen bacteria cannot fully degrade it. The exception can be ensiled winter annuals or legumes; these forages can have adequate levels of protein, but this needs to be confirmed with a feed nutrient analysis. In a study conducted recently at the NFREC, a reduction of 40% in body weight gain was observed in growing heifers self-fed corn silage without protein supplementation compared with heifers fed corn silage plus 10% cottonseed meal on a dry matter basis (2.5 pounds per day).

The most common forages ensiled in our area are corn and sorghum (forage or grain hybrids). These silages provide high energy due to their starch content when harvested at the right maturity. Perennial warm-season grasses and winter annuals can also be ensiled but require wilting to reduce moisture.

If a greater “slice” is offered, for example 2 linear feet per day, more animals can be fed. However, if we exceed this number of animals accessing the silo, some animals will become competitive and keep others from maintaining adequate feed consumption. To ensure that all animals have access to the silage bag, and that competition is minimized, it is recommended to have homogeneous groups of animals eating from the same bag. Therefore, avoid mixing, for example, weaned calves with mature cattle. A good, practical indicator of a correct stocking density is to see all cattle in the paddock resting at the same time with no anxious feeding behavior. Weighing the animals every few weeks or monthly can help determine if the target gains are being achieved.

Ensure nutritional needs

If intending to utilize silages for growing cattle, remember that most ensiled forages (with the exception perhaps of winter annuals or legumes) are typically deficient in protein;

In the case of cow-calf operations, self-feeding silage bags of warm-season perennials like limpograss or bermudagrass can be utilized to feed mature cows during periods of grass shortage, avoiding the need to feed round bales. Another interesting strategy is to allow cattle some hours of grazing of winter grasses during the day and placing them at night in a pasture with a self-feeding silage (corn or sorghum) bag. With this management, the winter grass provides high levels of protein that helps utilize the energy from the silage.

In summary, self-feeding ensiled forages can be a useful strategy for cattle operations, mainly due to reduced costs in labor and equipment. Different forages can be utilized, and nutrient deficiencies should be corrected depending on the requirements of the animals to be fed. If managed properly, minimal losses can be expected from this feeding system. •

March 2023 | hayandforage.com | 15

NICOLAS DILORENZO DiLorenzo (pictured) is a professor and extension beef specialist with the University of Florida and based in Marianna. Tarnonsky and Podversich are graduate research assistants.

Mature cows learned to respect the electric wire and were self-fed sorghum silage from the frontal bag face.

Control hay heating by wrapping lower moisture bales

Hay & Forage Grower is featuring results of research projects funded through the Alfalfa Checkoff, officially named the U.S. Alfalfa Farmer Research Initiative, administered by National Alfalfa & Forage Alliance (NAFA). The checkoff program facilitates farmer-funded research.

FARMERS attempting to bale dry hay while fighting weather that is too wet and/or too cool for drying to 15% to 17% moisture may have another option.

Alfalfa Checkoff-funded research found that wrapping relatively dry mixed-forage round bales with plastic film cuts off the crop’s oxygen supply, stops respiration, and preserves the forage as minimally fermented baled hay. “The large hay packages commonly used today are particularly prone to spontaneous heating, resulting in dry matter losses, poorer nutritive value, and, in extreme cases, spontaneous combustion,” said former USDA-ARS research dairy scientist Wayne Coblentz.

“It was striking the heating control we got in those bales with the elimination of respiration by simply restricting air access with plastic,” he added. Coblentz, recently retired as research leader at the U.S. Dairy Forage Research Center based at Marshfield, Wis., conducted the experiment with Matt Akins, who now holds that position, and Burney Kieke, a biostatistician with the Marshfield Clinic Research Institute.

PROJECT RESULTS

Wrapping relatively dry mixed-species forages with plastic film proved extremely effective in reducing spontaneous heating during storage and minimizing nutrient losses. This approach offers considerable promise as an alternative management option for preserving forages when uncooperative weather prevents baling at a moisture level suitable for safe storage as dry hay.

The colleagues compared alfalfa-orchardgrass forage baled in 5-foot diameter round bales at 25% moisture under four scenarios. Bales were wrapped with seven layers of plastic, treated with a propionic acid-based preservative and wrapped in plastic, left unwrapped but treated with propionic acid, or left unwrapped without preservative.

Each bale was weighed, core-sampled, and stored for 84 days before plastic was removed from wrapped bales. All were then again weighed and core-sampled. Moisture concentrations, pH, and nutritional values were measured, as well as the fermentation within wrapped bales evaluated.

“People still would like to bale dry hay for all kinds of different reasons, but it’s often difficult to get material as dry as it needs to be before baling in the North Central region,” Coblentz explained. “With hay packages larger in size, the problem of spontaneous heating and associated losses of dry matter and nutritive value have increased.”

The researchers had noticed a recent trend toward baling silages drier than 50% to 60% moisture, and some of

their other experiments had successfully baled forage crops at fairly low moisture concentrations (30% to 35%). Coblentz added, “With this specific experiment, we asked: ‘If we can get this hay down to 25% moisture, what happens if we just wrap it in plastic? How effective would that be?’

“It turns out it was very effective,” Coblentz said.

Less heating

Wrapped bales, whether treated with preservative or not, reduced heating and minimized nutrient losses. “Because there was little moisture in these bales, they didn’t ferment very much, which means basically you’re preserving them by excluding air,” he added.

Unwrapped bales accumulated considerably more heating units throughout storage, regardless of whether they were treated with a preservative or not. However, acid-treated unwrapped bales accumulated fewer heating units at 30 and 45 days post-baling, and dry matter recovery was improved significantly compared to unwrapped bales without preservative.

16 | Hay & Forage Grower | March 2023

YOUR CHECKOFF DOLLARS AT WORK

Effect of wrapping on bale heating 800 700 600 500 400 300 200 100 0 Heating degree days > 30 o C Wrapped Unwrapped 30 days45 days84 days30 days45 days84 days WAYNE COBLENTZ Funding: $13,335

After 84 days of storage, the wrapped bales had plastic removed and were monitored for another 33 days for aerobic stability. “This is where propionic acid has really shown a lot of benefit. The exposed, fermented bales that were treated with preservative exhibited characteristics that were consistent with improved

SUPPORT THE ALFALFA CHECKOFF!

Buy your seed from these facilitating marketers:

Alfalfa Partners - S&W

Alforex Seeds

America’s Alfalfa

Channel

CROPLAN

DEKALB

Dyna-Gro

Fontanelle Hybrids

Forage First

FS Brand Alfalfa

Gold Country Seed

Hubner Seed

Innvictis Seed Solutions

Jung Seed Genetics

Kruger Seeds

Latham Hi-Tech Seeds

Legacy Seeds

Lewis Hybrids

NEXGROW

Pioneer

Prairie Creek Seed

Rea Hybrids

Specialty

Stewart

Stone Seed

W-L Alfalfas

aerobic stability, and that’s similar with what we found in other experiments,” Coblentz said.

Farmers whose bales will stay uncovered for a time before being fed, or who plan to market those bales, may want to consider the dual application of acid with plastic to improve aerobic stability. But this also needs

to be weighed against cost, Coblentz explained. He suggested that preservatives and plastic wrap be considered, particularly when weather conditions are less than optimal for haymaking.

The experiment was conducted just before Coblentz retired. He’d like to see someone repeat it for consistency’s sake and possibly with grass hays. •

March 2023 | hayandforage.com | 17

Fewer cows but more net income

WHEN it comes to cow-calf production, it’s important to think about the big picture and how all decisions impact the operation. Is the goal to create a primary income for someone, generate supplementary income, or just for enjoyment with minimal losses? While it is tempting to look at gross income, the focus should be on net income and risk management.

The strategy that generates the highest net return may not be the same every year. So, it is important to consider what strategies will work best for the operation and people over several years. Not maximizing potential income one year may be the best decision for the operation and may help generate more net income over multiple years.

Net income is a function of both gross income and expenses. Net income can be increased by:

• Improving gross income while also controlling expenses

• Decreasing gross income while significantly lowering expenses

The long-term stocking rate for a property is one of the biggest factors impacting net income. In an effort to boost gross income, pastures are often overstocked, which leads to significantly higher expenses, lower weaning weights, and often reduced pregnancy rates. If properties are stocked to use all of the forage during good times, that means they are overstocked when forage is short. Having some forage left ungrazed can be beneficial for stand health and future forage potential.

It may be tempting to acquire more cow numbers in anticipation of the higher cattle prices that are expected in the coming years, but it is critical not to overstock the property. Additionally, for those producers who have recently experienced drought, be aware that forage production will likely be reduced after drought conditions.

How does stocking rate affect weaning weights and pregnancy rates?

Stocking rates impact both the quantity and quality of forage available for grazing. Forage quality varies throughout the plant. As a general rule, quality

is highest in the top third of growth and lowest in the bottom third.

Falling dominoes

When forage quantity is reduced, cattle are not able to be as selective in what they graze and end up consuming a lower-quality diet. This leads to reduced milk production and cow body condition score. Less milk production leads to lower weaning weights. Weaning weights are also inhibited because calves are consuming lower-quality forage. Cow body condition score is the main factor impacting pregnancy rates most of the time.

had 25 cows. If expenses could be reduced by more than $5,350 per year, then the net return would be greater by only running 25 cows compared with 33 cows. In addition, running fewer cows would also reduce risk during times of drought or higher input costs.

Opportunities for savings

With fewer cows, less hay would need to be fed. Supplementation would also be reduced by running fewer cows because cows could select a higher-quality diet and stay in better body condition. Fewer cows may also mean lower spraying costs (reduced frequency and amount) because the additional forage would help shade out a lot of weeds.

The following example illustrates how fewer cows may generate more net income for an operation. Consider a property with 100 grazeable acres that, under the best conditions, may be stocked with 33 cow-calf pairs (three acres per pair) compared to that same property stocked with 25 pairs (four acres per pair) or even 20 pairs (five acres per pair). Assuming a weaned calf crop of 78% to 80%, an estimated gross income per year can be calculated for each situation. Calf prices have been adjusted slightly to account for higher weaning weights as stocking rates are decreased.

• 33 cows x 78.8% = 26 calves x $975 per calf = $25,350

• 25 cows x 80% = 20 calves x $1,000 per calf = $20,000

• 20 cows x 80% = 16 calves x $1,025 per calf = $16,400

Without considering expenses, it looks like stocking the property with 33 cows is the way to go, as it creates the most gross income. However, the question that must be asked is how much can expenses (for example, fertilizer, feed, spraying, and so forth) be reduced if the operation only

For the example above, reducing costs by $5,350 only means lowering costs by $53.50 per acre. Assuming a cost of 82 cents per pound of nitrogen, just reducing nitrogen fertilizer by 70 pounds per acre would save $57.40 per acre. This reduction would be both realistic and appropriate in this situation, and a larger reduction in nitrogen fertilizer would be possible in some cases. Reducing nitrogen fertilizer can be a good strategy, but cow numbers should be trimmed accordingly to prevent overgrazing. Additional savings from reduced hay and supplementation needs would result in even greater net income in this example.

For those producers whose primary goal is enjoyment, then just running 20 cows would be a great choice. It would minimize hay and supplementation feeding the most and provide the greatest risk management to prevent herd reductions during times of drought.

The strategies to generate the greatest net return will vary, but for many operations, reducing cow numbers can be a good approach, and it also helps reduce risk. •

18| Hay & Forage Grower | March 2023

BEEF FEEDBUNK

by Jason Banta

JASON BANTA

The author is a beef cattle specialist for Texas A&M AgriLife Extension based in Overton, Texas.

Are you ready?

MOST of the country is on the downhill side of what has been a pretty tough winter for the West, although the moisture was welcomed in many areas. It’s almost time to put the planters in the dirt and get the mowers ready to lay down that first cutting, which usually provides our highest yield of the year. We can’t always bank on summer rains these days, so the first cutting that comes from winter moisture is crucial.

Now is the time to go over your equipment from head to toe to make sure it is ready to go when the time comes. Most people have a plan for servicing their equipment themselves and others rely on help from their dealers. Some manufacturers even offer incentives to bring your machines to a local dealer for service. Take advantage of these dealer maintenance opportunities and have an experienced mechanic look over your machine with a fine-toothed comb. There are many dealers that offer parts discounts on the shop work they complete and for the parts you order to stock your farm’s shelves.

A 20-page checklist

One of the most extensive winter checks that we perform is on forage

harvesters and heads. This inspection can take a few days, depending on the chopper. Our tech goes over each machine with a 20-page checklist, looking for loose and worn parts along the way. The list is almost too involved for most farmers, but we encourage the chopper owners who want to help with the inspection to do so. This way, the operator can become more familiar with their cutter. This may not be a process that will work for everyone and every machine, but we have several customers who prefer to be there and help while the inspection is being completed. Dealers around the country offer different options when it comes to completing winter service. Most dealerships find that their mechanics are far more productive in their own shops rather than on the farm with the customer. So, some dealers have offered to split the payment or completely pay for the hauling of the machine to and from the dealership. The cost of shipping the unit can usually be a wash if you pay for a couple service calls to your farm to complete the work.

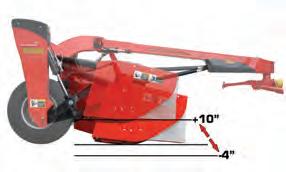

If you want to complete this off-season inspection yourself, I’ll give you a few guidelines to follow that can get you started in the right direction. On a pull-

type machine, baler, or mower, I suggest starting at the front with the hitch and drivelines. Inspect for any loose bolts and excess play in the yokes on the power takeoff (PTO). Go ahead and grease all the fittings to make sure they each accept grease. They are a lot easier to change in the shop than on a day when you are trying to get to the fields.

Working toward the rear of the machine, you should use a pry bar to check for any play or movement in bearings and ensure they are lubricated properly. Make sure hydraulic cylinders are holding pressure and not leaking internally.

Gears and chains

When you get to the main working components, cutterbar gears and chains on a baler require the closest inspection. There are some manufacturers that don’t require you to change the cutterbar oil in your mowers. I disagree with this recommendation. Would you drive your car for 50,000 miles without changing your oil? By draining the oil in your cutterbar, this offers a chance to inspect it for metal shavings and to examine it for any off-color, potentially allowing you to prevent a future problem.

Remove the chains on your baler and inspect them for play in the links. Once a chain is stretched too far, it doesn’t set properly and can start premature wear on the sprocket. It’s a lot easier to replace a chain or remove a link than it is to replace sprockets.

Spending some hours in the shop with your equipment in the off season will lead to more up time during harvest. Another benefit will be that you can troubleshoot the problems faster with your machines and have an educated conversation with your dealership’s mechanics to get you back up and running. Take advantage of maintenance incentive programs and parts savings. This is a good way to keep machine costs in check given the rising costs of production. •

ADAM VERNER

ADAM VERNER

FORAGE GEARHEAD by Adam Verner March 2023 | hayandforage.com | 19

The author is a managing partner in Elite Ag LLC, Leesburg, Ga. He also is active in the family farm in Rutledge.

Mike Rankin

Cocktail forage mixes: WHAT DO DAIRY COWS THINK?

S DAIRY producers have been growing more corn silage and feeding it in lactating cow rations, there has also been a rise in the use of other annual forages. This has been driven by expanding interest in planting cereal grains after corn silage is chopped and harvesting forage the following spring.

The use of various annual forages are also becoming common after the cereal grain forage harvest. One popular option is to use annual forage mixtures that contain cool-season (Italian ryegrass) and/or warm-season (brown midrib sorghum-sudangrass) annual grasses and legumes such as clovers and hairy vetch. Often these are called “cocktail” forage mixes.

The grass type included in the mix is likely the most important consideration and depends on the soil conditions and manure management. Sorghum-sudangrass does not tolerate wet soils or can be damaged by in-season manure applications; however, Italian ryegrass will not tolerate dry soil conditions, so the two are sometimes mixed to provide some insurance for what Mother Nature may provide.

In our work with cocktail mixes in 2021 and 2022, we have focused on a mix with sorghum-sudangrass, Italian ryegrass, and legumes. As part of a project funded by the University of Wisconsin Dairy Innovation Hub, we evaluated on a field-scale the yield and quality of cocktail forage mixes on four farms, including the University of Wisconsin’s Marshfield Agricultural Research Station. Those results are in the March 2022 issue of Hay & Forage Grower

Forage quality differed

The project also included feeding the forage from the second harvest, as it contained a blend of the two grasses, while the first harvest was primarily sorghum-sudangrass and the third harvest was primarily ryegrass. We harvested the forage in mid-September with cutting and wilting for one day and then chopping for silage. The silage

was allowed to ferment for four weeks before feeding. Ideally, the silage would have been allowed to ferment longer as it was not yet stable and had aerobic stability issues (yeast growth) due to a slow feedout rate during the study.

The diets included a mixture of corn silage (29% of diet dry matter [DM]) and either an alfalfa-grass silage or the cocktail mix silage (18% of diet DM) in addition to concentrate ingredients (Table 1). The treatment rations were fed to 16 first-lactation cows that were on each diet for eight weeks. The cocktail mix silage was higher in fiber (51.6% neutral detergent fiber [NDFom]), but the fiber was much more digestible (68% NDFD30) compared to the alfalfa-grass silage (40.4% NDFom; 52.2% NDFD30). Soybean meal was used to help balance protein since the cocktail mix silage was lower in protein content.

Diet nutrients mainly differed in starch and fiber with the cocktail mix diet having less starch (26.8% starch) and more fiber (26.2% NDFom) than

the control diet (28.4% starch; 22.3% NDFom). The NDFD30 of the cocktail mix diet was higher (68% of NDF) than the control (61.9% of NDF), which helped make the diets more similar in energy. The cows on each diet ate similar amounts of feed (57.2 pounds of DM), with the cows fed the cocktail mix diet eating more NDF (14.9 pounds of NDF) than the control diet (12.8 pounds of NDF), so fiber level did not result in reduced intakes, which was likely due to the fiber levels being fairly low (22% to 26% NDF). As mentioned earlier, the cocktail mix silage had poor stability after opening due to a slow feedout rate, and the farm staff discarded spoiled silage to reduce the effects on intakes. Feed intakes for both treatment diets increased during the study, so the impact was likely minimal.

Milk and components offset

Looking at milk production, cows fed the control diet produced more milk (83.7 versus 81.4 pounds per

DAIRY FEEDBUNK by Matt Akins and Hidir Gumus 20 | Hay & Forage Grower |March 2023

Die t Forage Ingredient, % of DM Control Cocktail Corn silage Alfalfa/grass silage Cocktail mix silage Corn silage 29.229.2 Alfalfa/grass silage 18.3 Cocktail mix silage 18.3 Dry ground corn 19.3 17.5 Soybean meal 1.8 Protein mix 23.523.5 Liquid whey permeate 9.29.2 Mineral/urea 0.50.5 Nutrients, % of DM CP 16.8 17.0 6.43 18.5 12.9 NDFom 22.3 26.2 40.4 40.4 51.6 NDFD 30h, % of NDF 61.9 68.0 51.4 52.2 68.7 Starch 28.4 26.8 34.6 1.38 1.77 TDN 73.7 70.8 71.0 58.6 57.8 NEL, Mcal/kg DM 0.77 0.740.74 0.60 0.59

Table 1. Diet and forage nutrient composition

day). However, milk components were higher for cows fed the cocktail mix diet, with higher milk protein (3.45% versus 3.38% protein) and slightly higher milkfat (4.83% versus 4.74% fat). When considering both milk yield and components, the energy-corrected milk yields were similar between diets (89.2 pounds per day for the control and 88.2 pounds per day for the cocktail). The difference in components also resulted in similar fat and protein yields for cows fed either diet.

Total-tract digestibility of NDF was similar to in vitro estimates with the cocktail mix diet having 66.2% NDFD and the control diet having 63.8% NDFD. However, dry matter and starch digestibility were greater for the control diet (81.5% DM and 99.2% starch digestibilities) than the cocktail mix diet (78.7% DM and 98.7% starch digestibilities).

Interestingly, when we measured the greenhouse gas emissions from the

cows’ eructated gases, the cows fed the cocktail mix diet released about 9% less methane (411 grams of methane [g CH4] per day) than the control diet (450 g CH4 per day). The reason for the reduction in methane released is potentially due to lower overall diet digestibility; however, methane typically comes from fiber fermentation and the cocktail mix diet had higher fiber levels. This was an unexpected outcome, so the specific reason for differences in methane emission needs further investigation.

Account for variability

The take-home message from this study is that cocktail forage mixes can be used in lactating cow diets as a substitute for other hay-crop silages. Ration formulation should consider differences in protein, NDF, and NDF digestibility between the forages to maintain similar protein and energy

intakes. Based on this work, having a forage with higher fiber digestibility helped offset the difference in energy content due to higher fiber content and maintained similar milk component yields.

With the use of new or different forages, sampling for nutrient analysis and working with a nutritionist is crucial for proper balancing of diets. That’s because the nutrient contents will be different depending on the forage types, fertility, and especially between harvests of cocktail forage mixes. •

March 2023 | hayandforage.com | 21 FOR DECADES The headline says it all. With a long legacy of reliable & consistent performance, we are confident that Rozol will be YOUR rodent brand. New to Rozol? Start a legacy of your own and visit our website or contact a sales rep today. SOLVING YOUR RODENT PROBLEMS liphatech.com • 888-331-7900 PROTECTING YOUR LAND Always read and follow label instructions. Rozol Vole Bait, Rozol Pocket Gopher Bait Burrow Builder Formula, Rozol Prairie Dog Bait and Rozol Ground Squirrel Bait are Restricted Use Pesticides. LEARN MORE

MATT AKINS AND HIDIR GUMUS Akins (pictured) is a dairy scientist at the U.S. Dairy Forage Research Center in Marshfield, Wis. Gumus is a visiting scientist with the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

22 | Hay & Forage Grower | March 2023

by Amber Friedrichsen

WHEN the summer sun sets over northwest Illinois, the crew members of Silver Streak Ag Services LLC cut their engines and climb down from their tractor cabs. Their job might not be done — in fact, it may have just been getting started — but they submit to their growling stomachs and pause for a paper plate meal in the middle of the field. This is a nightly tradition for John and Monica Osterhaus, owners of the custom forage harvesting business near Chadwick, Ill.

Silver Streak Ag Services’ customer base spans from the Mississippi River to the outskirts of Aurora, and from the Wisconsin border to a half an hour south of Interstate 80. While their current radius paints a broad stripe across the top of the Prairie State, it started out as a dot on the map.

John grew up on a farm in southwest Wisconsin and entered the workforce as a mechanic. He and Monica moved west when he pursued a job in the oil and gas industry and later relocated their family of five to Chadwick when John got a job on a pipeline. As they settled into their new life, the Osterhaus’ children attended a new school, made new friends, and got new jobs on a local dairy farm. Then one day, the farm’s owner asked for John’s help as well.

“He approached me and said, ‘You need to buy a round baler so you can bale my hay,’” John recalled. “I thought about it, talked to a few other people nearby, and realized there was a need for more custom work. We officially started Silver Streak Ag Services in 2011, bought our first tractor and round baler, and I started baling hay part time.”

After a couple of years, business was on a steady ascent. John sold the round baler and purchased a large square baler to meet customer demands, and he started receiving requests for custom chopping, too. He and Monica created a three-year plan to expand, but they didn’t want to move too fast. That is, until an irresistible opportunity fell into their laps.

“In the winter of 2014, our biggest competition sold out. We decided this was our chance, and our three-year plan became a three-week plan. We bought a chopper, rented silage wagons, and hired out all of our hauling,” said the self-made businessman. “The next summer, we chopped about 700 acres of rye, hay, corn for silage, and corn earlage for eight or nine customers, and we thought we were really

busy,” he laughed.

Today, Silver Streak Ag Services has nearly 50 clients. John chops approximately 5,000 acres and makes up to 6,000 large square bales each year with the help of three full-time employees: Tim Schwank, Coby Snider, and Cody VanDyke. While they manage operations by day, Monica organizes harvest schedules, runs the business’ social media, and delivers dinner to their crew and their customers every night.

Small-scale service

Many of John’s clients are grain farmers who also raise beef cattle. The region’s rolling topography prevents them from growing row crops in some areas, so they plant forages and seed cover crops on hillsides and slopes to harvest for livestock feed.

“The majority of our clientele are beef finishers or cow-calf producers,” John said. “A lot of the beef finishers want silage in their rations, but the cow-calf guys are our bread and butter. We chop more haylage and corn silage for cowcalf producers than anybody else in a given year.”

Of the total acres John chops annually, about 1,000 are alfalfa haylage. Another 1,250 acres account for small grains like wheat, barley, and triticale, and the remaining acreage is an almost even split between corn silage and earlage. Despite these numbers, though, each job is relatively small.

“Most of our chopping jobs are only 25to 50-acre fields, but we do a lot of them,” John explained. “It’s not uncommon for us to be at three or four customers in one day. We start out at one place, chop 25 acres, move down the road and chop another 50 acres, and so on.”

Because of this, communicating with clients is key to efficiency — especially when it comes to corn silage season. Some customers notify John when their corn is ready chop, whereas others trust him to scout their fields himself. One con-

versation about harvest sparks a chain reaction of calls.

“It’s not uncommon for me to be on 40 to 50 phone calls a day during corn silage season, talking to clients about the maturity of their corn, determining when they are ready to chop, and figuring out our route,” John said. “We try not to jump all over the place. If I have one customer who calls saying they are ready to chop, I make three more phone calls to his neighbors to see if they are ready, too.”

For full-service haylage jobs, the team runs a Pottinger triple mower, an Oxbo merger, and a Claas Jaguar 960. John owns several pull-type carts, and he regularly recruits some of his clients to haul silage. He also hires some of his customers who have pack tractors to help fill bunkers.

“We have a laundry list of people we can contact, and if we are in a bind, I know I can call them to see if they can help,” he said. “Some of them might help one day a year, and some will help us for three weeks straight, but if we didn’t have them, we wouldn’t be able to do this.”