BAR JOURNAL BAR JOURNAL

The 2024 HSBA Directory is coming out shortly with new addresses, phone numbers and photos. Every active attorney in Hawaii (who requested)will get a copy. The Directory is a quick and easy reference tool for attorneys and their support staffs. You can show your staff that you value their time and efforts by providing them with the

Name of Individual or Firm

most current Directory, instead of an outdated hand-me-down. This year there will be a limited number of extra directories available. Last year we sold out so place your pre-order for extra Bar Directories on or before September 20th to ensure that your firm receives enough copies of the 2024 Bar Directory.

Cost Per Directory $41.88Number of Extra Directories Ordered

❏ Will pick up at publishers office

❏ Please mail ($9.90 Per Directory for Postage & Handling)

❏ Payment by check (Grass Shack Productions)

❏ Will contact Publisher with credit card Information

Please mail or Email your order form

BOARD OF EDITORS

Christine Daleiden

Joseph Dane

Susan Gochros

Ryan Hamaguchi

Cynthia Johiro

Edward Kemper

Laurel Loo

Melvin M M Masuda

Eaton O'Neill

Lennes Omuro

Brett Tobin

HSBA OFFICERS

President

Jesse Souki

President-Elect

Mark M Murakami

Vice President

Mark K Murakami

Secretary

Kristin Izumi-Nitao

Treasurer

Lanson Kupau

YLD OFFICERS

President

Kelcie Nagata

Vice President/President-Elect

Chad Au

Secretary

Danica Swenson

Treasurer Amberlynn Alualu

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Catherine Betts

GRASS

Publisher

Brett Pruitt

Art Direction

Debra Castro

Production

Beryl Bloom

Advertising inquiries should be directed to:

brett@g rassshack net

On the Cover: Raindrops on Summer Snowflakes by Kelly Miyuki Kimura. A lifelong resident of Oahu, Kelly’s artwork has earned awards and recognition in exhibitions held by various Hawaii art organizations and has been accepted into the Women in Watercolor 2023 International Juried Exhibition You can find more of her work at http://miyuki-kimura pixels com or on Instagram: @miyuki arts

Notices and articles should be sent to Edward C Kemper at edracers@aol com, Cynthia M Johiro at cynthia m johiro@hawaii gov, or Carol K Muranaka at carol k muranaka@gmail com All submitted articles should be of significance to and of interest or concern to members of the Hawaii legal community The Hawaii Bar Jour nal reserves the right to edit or not publish submitted material Statements or expressions of opinion appearing herein are those of the authors and not necessarily the views of the publisher, editorial staff, or officials of the Hawaii State Bar Association Publication of advertising herein does not imply endorsement of any product, service, or opinion advertised The HSBA and the publisher disclaim any liability arising from reliance upon infor mation contained herein This publication is designed to provide general infor mation only, with regard to the subject matter covered It is not a substitute for legal, accounting, or other professional services or advice This publication is intended for educational and infor mational purposes only Nothing contained in this publication is to be considered as the rendering of legal advice

Introduction

Hawai‘i has a proud tradition of laws codifying the value of pretrial liberty, stretching back to the 1860s, and currently ref lected in its statutes and constitution. This tradition centers on the right to pretrial release for individuals accused, yet not convicted, of committing any crime. These laws also state that pretrial liberty should not depend on wealth. In 2019, the Hawai‘i legislature passed significant bail refor m legislation intended to strengthen this right and align common practice with these values On the five-year anniversary of the 2019 law, this article compares the law’s impetus with available data and bail practices Such analysis shows that pretrial detention continues to be the nor m, and there is still much room for improvement in making pretrial liberty a reality

Mass Incarceration and Pretrial Detention

The criminal legal system incarcerates thousands of people across Hawai‘i in what Justice Sabrina McKenna has called “ an over-incarceration epidemic.”2

According to the Prison Policy Initiative, nearly 24,000 Hawai‘i residents are behind bars or under community supervision as of 2023, and Hawai‘i “locks up a higher percentage of its people than almost any democratic country on earth.”3

T h e s c a l e o f

Criminal Justice Deep Dive: A Closer Look at Hawai‘i Bail Statutes and Practices

by Jongwook “Wookie” Kim and Samantha McNichols1

incarceration has increased dramatically within the span of a lifetime, with “Hawaii’s combined jail and prison population . . . increas[ing] 670%” in just the past four decades, as a recent task force observed.4

Multiple jails in Hawai‘i far exceed design capacity and even in late 2023, detained individuals were sleeping on the f loor due to overcrowding 5 The unsustainable levels of overcrowding and failing physical infrastructure have created dangerous conditions of confinement. This overcrowding persists even after the decades-long contracts to ship incarcerated people to private, for-profit prisons on the continental United States thousands of miles from home People have been subject to many tragedies, controversies, and crises in Hawai‘i p r

by

COVID-19 pandemic 6

Importantly, the effects of mass incarceration are not felt equally across the board For example, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders experience g ross overrepresentation in the incarcerated population 7 About 38% of individuals in Hawai‘i jails are homeless,8 a figure that has increased in the last decade 9 The practice of pretrial detention is one critical dimension of this ongoing crisis of mass incarceration According to the Prison Policy Initiative, at least 15,000 different people are admitted into Hawai‘i jails each year 10

Q Q

Ralph, tell us why Ralph Rosenberg Court Reporters is Hawaii’s largest court reporting firm?

It’s because of our loyal clients who say they appreciate our professional court reporters and friendly office staff who work hard to exceed their expectations.

Anything else?

Yes. For over 50 years we have adapted to the demands of pre-trial challenges and scheduling. With resident notaries and reporters on all major islands, backed by a statewide litigation support team we will work to make all aspects of the discovery process run smoothly.

These individuals, detained in Hawai‘i jails before being tried for their charge, constitute a significant percentage of the incarcerated population At the end of July 2024, 61 7% of the population detained at the Oahu Community Correctional Center (“OCCC”) were pretrial detainees At the same time, pretrial detainees accounted for 35.1% of the total incarcerated population at the eight active jails and prisons located in Hawai‘i 11 Confronting the volume the sheer number of lives impacted by pretrial detention is one way of making sense of available data In addition, the amount of time spent in pretrial detention is an important marker of how the system is operating According to a recent report by the Hawai‘i Correctional System Oversight Commission after a July 2024 tour, 220 people in the OCCC population or about 35% of its pretrial population have been held for more than 6 months in pretrial detention.12

This staggering pretrial detention is a problem, but it is not a new problem in Hawai‘i For example, the Intake Services Center received federal funding in the 1980s to “reduce the number of individuals incarcerated in the pretrial, pre-sentence, or sentenced categories” yet the jail and prison population exploded between 1978 and 1997, multiplying to over six times in size 13

The vast majority of people who enter the jails and prisons here will eventually be released back into the community A key question is when, and under what circumstances: will their release be preceded by a period of pretrial detention and separation from family, employment, and responsibilities? The administration of pretrial detention is a critical part of larger incarceration trends and public safety outcomes, which is why Hawai‘i bail laws are so important

For their part, both the bench and the bar in Hawai‘i have spent time evaluating pretrial detention This article builds on that work.

Defining Bail

By way of primer: what exactly is bail, and what is the pur pose of bail?

Bail refers to the conditions of release for a person charged with crime(s), pending trial In the United States, and in Hawai‘i, the most common condition of release is the arrestee’s payment of money or some for m of security (typically a secured bond) guaranteeing that the person will show up in court.14

The bail process is intended to ensure an individual’s appearance in court, consistent with the presumption of innocence that is foundational to our criminal legal system Indeed, as the Hawai‘i Supreme Court has stated, “the primary pur pose of bail is . . . to secure the presence of the defendant to answer the charges against him or her ” State v

Camara, 81 Hawai‘i 324, 332, 916 P.2d 1225, 1233 (1996).

S t a t e s v. Ryd e r , 1 1 0 U. S. 7 2 9 , 7 3 6

c e n t u r i

Layered on top of this “primary pur pose ” is the gover nment’s interest in public safety, which is most often raised by the prosecution The Hawai‘i Supreme Court has recognized that the “state has a legitimate interest in protecting its communities from those who threaten their welfare, and that this interest may be taken into account in the setting of pretrial bail,” so long as the incor poration of that interest is “ reasonable” and “satisfy[ies] the minimal demands of procedural due process. ” Huihui v. Shimoda, 64 Haw. 527, 542, 644 P.2d 968, 978 (1982); see also Hawaii Revised Statutes § 804-4

Bail is not intended to be used as punishment. As the Hawai‘i Supreme Court has stated, the point of bail “is not to punish a defendant or surety, nor to increase the revenue of the State, but rather to honor the presumption of innocence, by allowing a defendant to prepare his [or her] case ” without being held behind bars State v. Diaz, 128 Hawai‘i 215, 224, 286 P 3d 824, 833 (2012) 15

Further, contrary to popular belief, the bail process does not automatically require that money exchange hands. Courts can impose other conditions These alter natives include release on own recognizance (ROR), where the arrestee is released based on a written promise to appear in court without any financial obligation Another option is the unsecured bond, which does not require upfront payment but holds the arrestee liable for the bond amount if they fail to appear in court for their case Hawaii Revised Statutes § 804-9 5 Courts may also impose conditions such as pretrial supervision (supervised release), where the arrestee must regularly check in with a pretrial officer, or travel restrictions that prevent a person from leaving or entering a geog raphic area These alternatives are intended to ensure the individual’s appearance in court without imposing financial conditions for freedom

The Impact of Financial Conditions of Release

In 2015, the national median bail amount set by courts for a person facing a felony charge was $10,000 while the median annual income for a person in pretrial detention was $15,109 16 What is more, at least 37% of adults in the U S cannot cover a $400 emergency expense.17 These are troubling indications that many arrestees cannot afford money bail

There are reasons to suggest that this phenomenon also holds true in Hawai‘i In 2020, about 43% of oneadult households in Hawai‘i had an income below the state self-sufficiency level.18 Further more, approximately 3 in 4 households in Hawai‘i are carrying debt, with Native Hawaiians and Filipinos being more likely to have income below the basic cost of living or living below the federal poverty line.19

And yet, both in the United States and in Hawai‘i, the most common condition of pretrial release is requiring payment in exchange for release, as a guarantee to appear in court. T his is commonly refer red to as the “ money bail” system For example, a 2018 analysis showed that circuit courts across Hawai‘i set money bail in 88% of cases.20 T he practical outcome of such a system is that, when the police ar rest someone, the accused can purchase their release from pretrial detention if they possess enough money But someone who is unable to af ford that bail amount remains incarcerated while they wait for trial

Research shows the devastating impact of pretrial detention on not only the person detained, but also on family members and the broader community Starting with the individual charged with a crime, a few days in jail can initiate a domino effect causing loss of job, housing, and even child custody 21 Jail keeps individuals from showing up for work, which can lead to ter mination and loss of essential income. Similarly, when someone is locked up, they can miss school, rental payments, medical appointments, fall behind on life obligations, and cannot provide care for children and family members in their household

When it comes to their actual criminal case, a person who is detained prior to trial has a g reater chance of being convicted, either by being found guilty at trial or by pleading guilty to the

Resolving

Experienced in mediating and deciding complex family law, wills, trusts and probate cases including family business disputes. Also experienced in commercial, corporate, personal injury, HR and business mediations and arbitrations.

Michael A. Town

charges.22 Pretrial detention jeopardizes an individual’s ability to prepare for trial because they are detained and subject to jail restrictions that limit when and how they can participate in their defense Pretrial detention is also connected to harsher overall case outcomes One study found that, all else being equal, individuals detained pretrial were over four times more likely to be sentenced to jail, and three times more likely to be sentenced to prison in both cases, with longer sentences than individuals who were not detained pretrial.23 In tur n, there are many collateral consequences that result from criminal convictions 420 possible consequences in Hawai‘i, according to the National Inventory of Collateral Consequences of Conviction 24 Thus, if someone is detained pretrial, their exposure to negative collateral consequences increases Being jailed can be a matter of life or death. Kalief Browder, who was arrested at 16 years old for stealing a backpack, could not afford the $3,000 bail set by the judge, and spent three years at Rikers Island jail in New York before prosecutors dismissed the charges.25 Browder was scarred by his experiences in jail and died of suicide at age 22 26 Tragedies stemming from the pretrial detention system are happening here in Hawai‘i too. In 2013, a 76-year-old man named Cyrl Chung was in a “special holding unit” at OCCC for cigarette possession He had been detained for two years on a robbery charge, awaiting trial. Because the jail was overcrowded, jail staff placed Chung in a shared cell with a person who had threatened jail staf f, and who beat Chung to death 27 In A pril 2023, Jimuel Gatioan, who was detained pretrial at OCCC, died of suicide mere weeks after ar riving at the jail despite multiple war nings that he was suicidal 28 In May 2024, Artrina De Lima died of suicide less than a month after she was detained pretrial in the Maui jail for petty misdemeanor tres-

passing, a contempt charge, and a probation violation 29

The impacts of pretrial detention also ripple out to family members and loved ones, who experience the trauma of worrying about a jailed relative. Family members may try to cover for an individual’s financial and personal obligations, if they are able, including emergency childcare or home healthcare If money bail is an option, the family of a detainee may incur serious financial hardship trying to scrounge together emergency funds to get their loved one back home pending trial.

Finally, another impact of the pretrial detention system is that it imposes an extremely heavy burden on the public’s fiscal resources, diverting substantial taxpayer dollars to maintain jails and support the carceral system. For those motivated by financial impact, reducing the number of pretrial detainees by half would save the state gover nment $45,000 per day, or $16 million per year, according to the HCR 85 Task Force on Prison Refor m.30

Some people have concer ns about the impact of pretrial detention on public safety, but reducing pretrial detention does not jeopardize public safety This is a particularly important consideration, because the vast majority of people who are arrested will eventually be released. Objective, evidence-based research shows that pretrial detention does not improve community safety For example, one comprehensive Kentucky study which examined over a million individuals booked into jails over a decade found that longer times in pretrial detention did not have “deterrent effects” and were actually linked with increased re-arrest rates 31 Another study that analyzed eleven bail refor m jurisdictions concluded that “neither violent nor nonviolent crimes or charges increased markedly immediately after jurisdictions implemented bail refor m.”32

The History of Bail in Hawai‘i

Several sources of law operate in tandem to gover n and constrain pretrial bail practices in Hawai‘i. These sources include the United States Constitution, the Hawai‘i Constitution, Hawai‘i statutory law, and both federal and state decisional law inter preting these various legal provisions. Because the federal constitution-based principles regarding bail have already been extensively explored elsewhere,33 this article focuses exclusively on Hawai‘i law

The right to pretrial liberty has existed in Hawai‘i since at least 1869, but it stands in stark contrast to the current system of expansive pretrial detention

This section provides an early history of bail laws in Hawai‘i across a century, beginning in the mid-1800s and tracking changes through the late 1900s. This section then tur ns to an overview of bail refor m efforts in recent decades, which culminated with Act 179 in 2019.

An Early History of Hawai‘i Bail Laws: 1869 to 1980s

The right to pretrial release in Hawai‘i predates statehood, with jurisprudential roots in the Hawaiian Kingdom

The Penal Code of Hawai‘i of 1869 set out eighteen relevant provisions, including those defining bail, specifying “in what cases ” bail applied, outlining “by whom” bail could be allowed, and gover ning how judges deter mined bail amounts 34

Critically, this early instantiation of Hawai‘i bail law expressed three foundational principles that have carried through to the present day

First, rich and poor individuals should be treated equally. The 1869 provision on “Amount of bail” stated that the bail amount “should be so determined as not to suffer the wealthy to escape by the payment of a pecuniary penalty, nor to render the privilege useless to the poor ”35 In other words, to

ensure fair ness, the bail process should prevent rich people from simply paying a relatively insignificant sum to obtain their freedom while similarly situated indigent people remain imprisoned

Second, and relatedly, the bail-setting process must evaluate an individual’s ability to pay Specifically, section 6 stated that, “[i]n all cases, the of ficer letting to bail should consider the pecuniar y circumstances of the party accused ”36

Third, pretrial liberty is the nor m Specifically, in 1869 this meant that the “accused shall be bailable” in “all cases ” with the exception of those involving crimes “punishable with death, imprisonment for life, or for a ter m of years exceeding ten.”37 Thus, the intention was for the vast majority of individuals charged with crime to benefit from pretrial release on bail

Since the 1869 enactment, Hawai‘i bail laws have been revised over a dozen times, but these three core principles have remained in each iteration For example, Queen Lili‘uokalani re-affir med these foundational legal principles in an 1892 act “to better define the right of defendants in criminal cases to bail ”38 Section 1 of that act again reiterated that “All persons charged with criminal offenses shall be bailable by sufficient sureties, unless for capital offenses” and provided that, when a defendant was eligible, that defendant could be “admitted to bail before conviction as a matter of right ”

Following annexation, the bail laws were changed several more times. A significant change to the laws gover ning bail occurred in the middle of the 20th century, via the adoption of the Hawai‘i Constitution and subsequent amendments. T he 1950 Hawai‘i Constitution included a provision addressing “ excessive bail ” T his section was subsequently amended twice, in 1968 and 1978 T he Hawai‘i Constitutional Convention Studies 1978 which the legislature commissioned to “present in

under standable for m many of the possible issues and arguments” regarding the provisions being considered clarified that “[t]he primary pur poses of bail in a criminal case are to insure the defendant’s appearance in court whenever the defendant’s presence is required, to relieve the defendant of imprisonment, and to relieve the state of the burden of keeping a defendant pending the trial ”39

Article I, Section 12 of the Hawai‘i Constitution now provides: “Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel or unusual punishment inf licted T he court may dispense with bail if reasonably satisfied that the defendant or witness will appear when directed, exce pt for a defendant charged with an of fense punishable by life imprisonment ”40

Aside from the applicable constitutional amendments, the legislature made statutory amendments to Hawai‘i bail laws. Significant substantive statutory amendments were made in 1980, 1987, and, most recently, in 2019.

With the 1980 amendments, the legislature narrowed the scope of the statutory right to bail. For example, the amendments precluded the automatic right to bail for individuals charged with a “serious crime,” which in tur n was defined to mean most class A and B felonies.xli Further, as to the right to bail post-conviction, the amendments reduced the number of charges for which individuals were automatically entitled to bail, from “all

cases other than those wherein a sentence of at least twenty years ’ imprisonment may be imposed” (in other words, all but the most serious felonies) to only non-felonies The legislative history shows that the motivation behind these changes was the belief that “there ha[d] been g reat abuse of the privilege of bail by persons who have been previously convicted of felonies ”42

But this narrowing of the right to bail did not go completely unchallenged Notably, then-senator (and later-Governor) Neil Abercrombie vehemently opposed the measure He argued that the “ g reat abuses” cited by the legislature had not in fact been substantiated, and expressed concer n that the presumption of innocence would be under mined by the change 43 In his view, the measure did “offense to the whole concept of bail” and did “violence to the conceptualization of bail [as it had been developed] over many centuries of struggle and effort in the cause of communities and societies becoming free.”44

Later that decade, the 1987

amendments expanded the right to post-conviction bail pending appeal, thus softening some of the harshness of the 1980 amendments. At that time, only individuals convicted of non-felonies were eligible to

be released on bail during the pendency of their appeal, and, in critics’ view, this gave rise to serious injustice As the testimony of the Hawaii Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers observed, “this dilemma results in jail time before [appellate] review by the courts” such that individuals who eventually successfully appealed and overtur ned their convictions would have been forced to spend “time [that] is lost forever with no recourse ”45 The 1987 amendments ultimately allowed bail pending appeal, but only if the court found that the individual “[wa]s not likely to f lee or pose a danger to the safety of any other person or the community if released ”46 Notably, the legislative history reveals that the intent behind the change was to adopt “the federal standards for determining bail pending appeal.”47

A Mandate to Safely Maximize Pretrial Release: Recent History of Bail Refor m

In recent years, both the bench and the bar in Hawai‘i have examined the role that pretrial detention has played in high incarceration rates and public safety outcomes Beginning in the 2010s, stakeholders have increasingly spoken out about problems with the existing system and taken steps to change the Hawai‘i bail system

In 2010, the Office of Hawaiian Affairs issued a report emphasizing the disproportionate impact of the criminal legal system on Native Hawaiians Among the findings was that, although Native

general population, they constituted 33% of people in pretrial detention and 39% of the incarcerated population 48

In 2011, various Hawai‘i stakeholders, including then-Gover nor Neil Abercrombie and Chief Justice Mark Recktenwald, requested assistance from the Council of State Gover nments Justice Center to analyze how the pretrial system was functioning, as part of a “justice reinvestment” strateg y.49 The Justice Center made a key finding that “extensive and increasing delays in the pretrial process ” led to “the pretrial population increas[ing] 117 percent from FY2006 to FY2011, which contributed to a 47 percent increase in the [overall] jail population ”50 The report also documented that pretrial releases took an average of three months in Hawai‘i 51 The report stated that, compared to 39 large counties in the United States, the county of Honolulu had the longest average length of detention for those ultimately released during the pretrial stage 52

Based on this “justice reinvestment” analysis, the legislature passed two bills, one of which required “timely risk assessments of pretrial defendants to lessen the costly delays in the pretrial process ”53

In 2016, the Bench-Bar Criminal Law Forum also focused on justice refor m and pretrial release.54 Specifically, it tried to answer the question: “Should Hawaii’s policies and procedures be reexamined to ensure that defendants are af forded the least restrictive release ter ms consistent with statutor y considerations reg arding f light risk and danger?”55 One of the Forum’s conclusions was that “[t]he cur rent pretrial release procedures appear to be inadequate due to the lack of timely bail studies and re ports, lack of alter nate release conditions for those who cannot af ford money bail, and lengthy pretrial incarceration for those who have not been provided hearings.”56

The next year, the 2017 Bench-Bar

Conference revisited the issue of bail refor m and came to similar conclusions about the inconsistency and arbitrariness of the existing system.57 Among other things, participants noted the “inconsistency in bail” across courts and circuits as to “what materials or infor mation the court considered when setting bail,” sharing that “[g]enerally, on Oahu, bail is arbitrarily set based on the class of the felony,” and that “the setting and purpose of bail hearings are inconsistent and confusing ”58

Separately, as an outg rowth of the 2016 Criminal Forum, the Hawai‘i State Legislature asked the Judiciary to create a Criminal Pretrial Task Force to recommend legislation to “increase public safety while maximizing pretrial release of those who do not pose a danger or a f light risk.”59 The resulting comprehensive report, submitted to the legislature in December 2018, made 25 targeted recommendations to improve pretrial release practices These tailored legislative proposals spanned from prophylactic, front-end enforcement recommendations (e g emphasizing police officer discretion to issue citations instead of arrests for certain charges; and expanding alter natives to pretrial detention),60 to robust procedural recommendations (e g creating a rebuttable presumption of pretrial release for non-violent class B or C felonies and misdemeanors) 61

2019 Amendments (Act 179)

In 2019, following this decade of scrutiny of the Hawai‘i pretrial system and guided by the recommendations of the Criminal Pretrial Task Force, the legislature passed what some commentators described as a “landmark” bail refor m bill, H.B. 1552 H.D. 2 S.D. 2 C.D. 1 (Act 179). This law made changes to the bail statutes gover ning eligibility for and conditions of pretrial release in at least three significant respects

First, the act requires that courts impose the “least restrictive conditions” of

pretrial release. Arrestees who have a right to bail must be released “under the least restrictive conditions required to ensure the defendant’s appearance and to protect the public ”62 As a representative of the Hawai‘i State Judiciary testified, this change would help ensure that “pretrial defendants, who are presumed innocent, should not face ‘over-conditioning’ by the imposition of unnecessary and burdensome conditions.”63

Second, as to the amount of bail, Act 179 does not disturb judges’ discretion to set bail amounts, but clarifies that judges need to consider the individual’s ability to pay in doing so. Specifically, Act 179 replaces archaic language about considering the “pecuniary circumstances of the party accused” with language that the bail amount “shall be set in a reasonable amount based upon all available infor mation, including the defendant’s financial ability to afford bail.”64 The Hawai‘i State Judiciary testified to the legislature that, as of 2019, “little, if any, inquiry is made concer ning the defendant’s financial circumstances” a practice that was inconsistent with “federal courts [that] have held that a defendant’s financial circumstances must be considered prior to ordering bail and detention ”65

Third, Act 179 specifies a handful of procedural requirements for a “prompt hearing” regarding bail 66 This hearing must be held after an arrestee is for mally charged and detained, either at the time of arraignment or as soon as practicable.67 This hearing allows for a judge to deter mine whether an arrestee, who has the right to be represented by counsel, should be released or detained prior to trial

Act 179 also made several other administrative changes regarding bail For example, it imposed a three-day deadline by which Intake Services Center staff must prepare and file risk assessments and bail reports with the court. It also established a statewide prog ram

to per mit the posting of money bail twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week

Finally, Act 179 created the Hawaii Correctional System Oversight Commission, which is responsible for providing “independent oversight of the State’s correctional system,” and the Criminal Justice Research Institute (CJRI), which is supposed to be the “centralized statewide criminal pretrial justice data reporting and collection system ”68

Current Practices and Reality

Although Act 179 was intended to improve the Hawai‘i pretrial system, our empirical observations and publicly available data show that, five years after its enactment, there has been no appreciable change in the rates of pretrial detention. This raises questions about whether and how the 2019 bail refor ms changed actual practices within the Hawai‘i criminal legal system.

Empirical Observations

In 2023 and 2024, the authors attended both district court and circuit court proceedings to observe how judges were making bail deter minations in a post-Act 179 world

As a general matter, bail was being confir med in the context of very brief hearings. Some were under a minute. The majority were mere minutes long Few lasted 10 minutes It is hard to imagine how any meaningful inquiry into someone ’ s ability to pay and the consideration of the various alter natives for conditions of release could be completed in such a short time span

The observations matched that common-sense concer n Bail was often mechanically confir med at apparently unaffordable amounts For those individuals already in pretrial custody, bail tended to be confir med with amounts in the four- to five-figure range, even for lifelong Hawai‘i residents for whom the gover nment provided no evidence of

f light risk.

Bail was often confir med at the initial set amount without further explanation. Even when defense counsel moved for less-restrictive conditions (such as supervised release, reduced money bail amounts, or release on recognizance) these requests were regularly denied, usually without explaining why each lessrestrictive condition was not appropriate, or explaining how the confir med bail amount was the “least restrictive” condition that was appropriate under the circumstances. It was observed that no judge ever g ranted unsecured money bail, even though a separate 2019 law amended the Hawai‘i bail statutes to clarify that judges should consider such “unsecured financial bond,” which is a less-restrictive condition than secured money bail.69

A person ’ s ability to pay was not assessed on the record Generally, individuals were not asked about their assets, liabilities, net worth, income, employment status, dependents, living expenses, or ability to borrow money The absence of such inquiry was particularly noticeable in cases involving arrestees who clearly would appear to have limited ability to pay, such as individuals who were houseless

These observations align with the judiciary’s own observations about bail practices in recent forums and task forces, as well as the limited case law addressing these issues For example, in an Inter mediate Court of A ppeals case this year, the court stated the First Circuit Court had made “ no findings” analyzing the accused’s ability to afford bail, nor why the $3 3 million bail amount was “reasonable” based upon the available infor mation showing income of $861 per month and monthly debt of $543

See State v Carter, 154 Hawai‘i 96, 104, 546 P 3d 1210, 1218 (A pp 2024) These errors in procedures and analysis occurred in a case with a serious charge and an unusually high bail amount

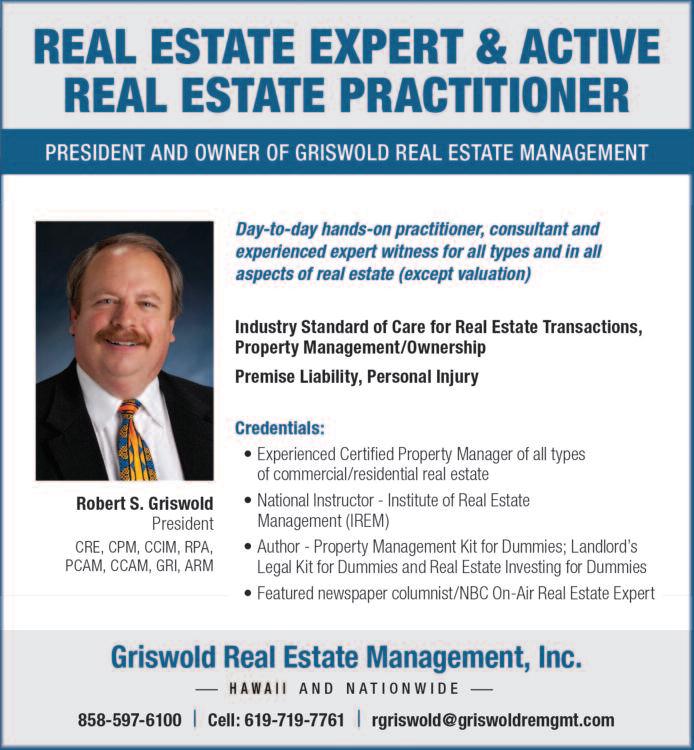

Industry Standard of Care for Ownership/Property Management, maintenance, AOAOs, Hotels, and RE Transactions

Premises Liability, personal injury, mold, habitability

Experienced Certified Property Manager of all types of commercial, retail, hospitality and residential real estate

Mediation & Arbitration

An experienced and even-handed approach

Torts and Personal Injury, including Medical Malpractice, Business Disputes and Contracts; HR and Employment Claims

Over 30 years experience in practice in Honolulu

10 years in litigation, including jury trials to verdict and many arbitrations

20 years in-house counsel with extensive experience in contracts, business transactions, medical malpractice and tort claims and HR and Employment matters

HI 96813 Tel: 1 (808) 523-1234

(808) 599-9100

The authors recognize that it may seem easy to simply critique or defend any given individual bail deter mination The stakes are high. But it is the collective impact of these individual cases viewed objectively within their procedural context that constitutes the pretrial system While the observations were by no means exhaustive, they suggest that the 2019 statutory requirements regarding the use of least restrictive means and consideration of an individual’s ability to pay are not being robustly applied.

Pretrial Data

The available data supports these empirical observations In short, even though Act 179 was enacted to reduce the scale and scope of the pretrial detention system, the Hawai‘i pretrial population has seen no significant reduction since 2019 in fact, the number of people locked up pretrial today is almost exactly the same as it was five years ago

The authors manually reviewed the limited publicly available data, including data about jail and prison populations collected from the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (DCR70) DCR is the administrator for the unified system of jails and prisons in Hawai‘i As of August 2024, DCR operates all the institutions that hold detained individuals in Hawai‘i, including the four jails and four prisons across the islands DCR publishes populations reports disclosing the number of people in each facility on a given date.71

The data reveal several key takeaways about the Hawai‘i pretrial system

First, pretrial detainees today constitute a large share of the overall incarcerated population. According to DCR’s most recent population report, as of July 31, 2024, there were 989 individuals being detained pretrial for felony and misdemeanor charges, out of a total of 3,816 people incarcerated systemwide.72 This means that over a quarter of the

people locked up in Hawai‘i have not yet been convicted of committing the crime they are being detained for The vast majority of these individuals being detained pretrial (663 people) were incarcerated at OCCC, the main jail in Hawai‘i

Second, over the last decade, with the exception of 2020-2021 (when Hawai‘i was dealing with the COVID19 pandemic), the total number of pretrial detainees remained relatively constant An analysis of data from DCR annual reports and end-of-month population reports, showing the number of individuals detained pretrial at the end of a given month (June) from 2012 to 2024, is ref lected in Figure 1 (see page 16).73

Except for decreases in 2020 and 2021 (attributable to emergency measures that the Judiciary took to address the COVID-19 outbreak in DCR facilities), the number of individuals in pretrial detention has remained roughly the same for over a decade At the end of June 2012, there were 924 pretrial detainees At the end of June 2024, there were 1,047 pretrial detainees. Importantly, these numbers do not include individuals charged with probation violations (as the Justice Reinvestment analysis in the 2010s did), which would mean that the pretrial population is an even larger share of the total incarcerated population

Third, pretrial detainees have constituted an increasingly larger share of the overall carceral system in recent years

Figure 2 (see page 16) shows that the number of total individuals held in the Hawai‘i carceral system has decreased in the last decade or so, from 5,669 in 2015 to 3,828 in 2024 However, given that the number of individuals in pretrial detention has remained relatively constant over this same period (see Figure 1), this means that pretrial detainees have constituted a proportionally larger share of

the entire system over the last decade. Whereas pretrial detainees constituted 19 19% of the Hawai‘i incarcerated population in 2015, they now constitute 27 35% in 2024 This is ref lected in Figure 3 (see page 16).

Fourth, OCCC (the facility that incarcerates the majority of pretrial detainees) is consistently and significantly over both its design and operating capacities. The DCR data regarding OCCC’s head count over time, compared to the facility’s “design capacity” and its “operating capacity,” is ref lected in Figure 4 (see page 16)

This g raph shows that the incarcerated population at OCCC is substantially above design bed capacity sometimes almost double that design capacity and almost always above operational bed capacity as well. Again, an exception is that in 2021, OCCC’s population dipped just under operational bed capacity in light of the Hawai‘i Supreme Court’s emergency measures implemented to address the COVID-19 outbreak in Hawai‘i jails and prisons

Fifth, and finally, total pretrial detention numbers now are virtually the same as the pre-Act 179 numbers, five years after the enactment of Act 179 (see Figure 5 on page 16)

In May 2019, before Act 179 was signed into law, 1,048 individuals were detained pretrial in DCR custody at the end of the month In June 2024, 1,047 individuals were detained pretrial in DCR custody From this perspective, there has been no significant, sustained decrease of the pretrial population since 2019

Conclusion

On the fifth anniversary of Act 179, the legal community is well-positioned to take stock of the history of bail laws in Hawai‘i and whether current practices vindicate the foundational right to pretrial liberty. This much is clear from the statutory history: people should not be in

(Continued on pa ge 16)

C O U R T B R I E F S

New Court Appointed Special Advocates Sworn-In

The Hawai‘i State Judiciary cong ratulates the newly trained Court A ppointed Special Advocates (CASA) who were swor n in as officers of the court by the Honorable Natasha R Shaw on July 19 at the Ronald T.Y. Moon Judiciary Complex. The new CASAs are now ready to advocate for children in the First Circuit (O‘ahu)

The CASA Prog ram (for merly known as the Volunteer Guardian Ad Litem Prog ram) empowers everyday citizens to serve as the “ eyes and ears ” of the court, to help provide accurate and objective infor mation so that decisions in family court cases can be made in the best interest of the child

In an overburdened social welfare system, abused and neglected children often slip through the cracks among hundreds of current cases. CASA volunteers change that.

After successful completion of an intensive 40-hour training and criminal backg round checks, CASA volunteers are appointed by family court judges to represent and advocate for a child both in and out of court CASAs typically handle one case at a time and commit to staying on that case until the child is placed in a safe, per manent home

For more infor mation on becoming a CASA volunteer, visit: https://casahawaii org, or call:

• O‘ahu: 808-954-8124

• Maui, Moloka‘i, Lana‘i: 808-244-2729

• Kaua‘i: 808-482-2570

• Hawai‘i island (Hilo): 808-961-7672 (Kona): 808-443-2105

CASA volunteers must be able to spend between four and 15 hours a month serving as fact-finders, advocates, and monitors for children in need The Judiciary provides free training and staff support for all volunteers.

Per Diem Judge Announcements

Renee N C Schoen was recently appointed as per diem judge of the District Family Court of the Third Circuit. Her ter m is effective August 1, 2024 to July 31, 2025

Dalilah E Schlueter was appointed as a per diem judge of the District Family Court of the Third Circuit. Her ter m is effective August 5, 2024 to August 4, 2025

Judiciary History Center Launches New Digital Archive

In July, the King Kamehameha V Judiciary History Center (Center) launched a new digital archive providing free public access to resources from its historic collections. This collections portal is made possible through a partnership with the Per manent Legacy Foundation, a nonprofit that provides long-ter m digital storage for historic records to individuals and nonprofit organizations

The Center stewards historical material dating to the Hawaiian Kingdom, the republic and territorial periods, through statehood In addition to court-related art, objects, and artifacts, the Center’s archives hold a range of physical and digital resources, unique to the institution, that carry significant educational and historical importance for current and future generations

The newly digitized resources are just a fraction of the total holdings from the Center’s archives at Ali‘iolani Hale. In the coming months and years, many more legal records, photog raphs, maps and blueprints, manuscripts, and newspaper articles will be digitized and added to the online portal One upcoming digitization project includes processing the papers of for mer Hawai‘i Chief Justices, including the late Chief Justice William S Richardson

Number of individuals in pretrial detention at the end of June, 2012 to present

1: Line g raph depicting the number of individuals in pretrial detention in Hawai‘i at the end of June from 2012 to 2024 Source: Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, State of Hawai‘i, https://dcr hawaii gov/about/divisions/cor rections/ (DCR population reports) and https://dcr hawaii gov/about /divisions/cor rections/ (PSD annual reports)

to present

Percentage of pretrial detainees in total incarcerated population,

4: Line g

depicting the number of individuals detained at OCCC from 2014 to 2023 at the end of the month in December of each year Source: Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, State of Hawai‘i

While Act 179 was intended to effect significant change in our pretrial system, significant aspects of the act are not being implemented, which is resulting in a system where pretrial detention rather than liberty is the nor m.

1 Thank you to Taylor Brack, Emily Sarasa, and Carrie Ann Shirota for their contributions to this article

2 In the Matter of Individuals in Custody of the State of Hawaii, 2021 WL 4762901, *12 (Haw. 2021) (McKenna, J , concurring and dissenting)

3 Prison Policy Initiative, Hawaii profile, pretrial detention due to poverty

Figure

Figure 2: Line g raph depicting the number of individuals incarcerated systemwide at a point in time (June of each year) from 2012 to present Source: Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, State of Hawai‘i

Figure 3: Line g raph depicting the percentage of individuals detained pretrial as part of the total incarcerated population systemwide from 2012 to present Source: Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, State of Hawai‘i

Figure

raph

Figure 5: Line g raph depicting the number of individuals detained pretrial at OCCC from 2019 to present Source: Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, State of Hawai‘i

https://www prisonpolicy org/profiles/HI html (last visited Jul 22, 2024)

4 HCR 85 Task Force, Creating Better Outcomes, Safer Communities: Final Re port of the House Concurrent Resolution 85 Task Force on Prison Refor m to the Hawai‘i Le gislature 2019 Re gular Session, (Dec. 2018) at xiii (hereinafter HCR 85 Task Force Report).

5 See, e g , Arielle Argel, Hawaii Community Cor rectional Center way over capacity, KITV Island News (Oct 5, 2023)

6 See, e g , The Correctional Refor m Working Group, Getting it Right: Recommendations and Action Plan for a Better Jail at 4-6 (Dec 2021); see also HCR 85 Task Force Report at xiii; see also Gabriel Thompson, Prisoners in Hawaii Are Being Sent to Die In Private Prisons in Arizona, VICE (March 13, 2017)

7 Prison Policy Initiative, Hawai‘i profile, https://www prisonpolicy org/profiles/HI html (last visited Jul 22, 2024)

8 Carrie Ann Shirota, Jamee Miller, Liam Chinn, Green Has Historic Opportunity to Build Community Safety, Honolulu Civil Beat (July 8, 2024); see also Gavin Thor nton, James Koshiba, and Joyce Lee-Ibarra, Touchpoints of Homelessness: Institutional Discharge as a Windo w of Opportunity for Hawai‘i’s Homeless (Sept. 2017).

9 See Mileka Lincoln, DPS: Estimated one in three at OCCC is homeless, Hawaii News Now (Aug 26, 2014)

10 Prison Policy Initiative, Hawai‘i profile, https://www prisonpolicy org/profiles/HI html (last visited Jul 22, 2024)

11 Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation: Correctional Institutions Division, End of Month Population Re port – 7-31-2024, available at: https://dcr hawaii gov/wpcontent/uploads/2024/08/Pop-Re ports-EOM2024-07-31 pdf

12 Hawaii Correctional System Oversight Commission, Oahu Community Cor rectional Center (OCCC) Jul y 2024 Site Tour Obser vations, at 2 (Aug 22, 2024)

13 See State of Hawai‘i, Intake Service Center, Jail Overcro wding Project Final Re port (A pr 15, 1981) https://www ojp gov/ncjrs/virtual-librar y/abstracts/hawaii-intake-ser vice-center-jail-overcro wdingproject-final-re port; HCR 85 Task Force Report at 1

14 ACLU of Hawai‘i, As Much Justice as You Can Af ford: Hawaii’s Accused Face an Unequal Bail System (Jan 2018) at 23 (hereinafter ACLU Report)

15 U S Commission on Civil Rights, T he Civil Rights Implications of Cash Bail (Jan 2022) at 7

16 Nicole Zayas Manzano, T he High Price of Cash Bail, 48 ABA Human Rights Magazine 3 (A pr 12, 2023)

17 Federal Reserve, Economic Well-Being of U S Households in 2022 (May 2023) at 32

18 The State of Hawai‘i Data Book 2021, Annual Self-Suf ficiency Famil y Budgets For Selected Famil y Types: 2020, https://files hawaii gov/dbedt/economic/databook/2021-individual/13/132621 pdf

19 Aloha United Way, ALICE in Hawai‘i: 2022 Facts and Figures (Nov 2022), https://www auw org/sites/default/files/pictures/ALI CE%20in%20Hawaii%20%202022%20Facts%20and%20Figures%20Full% 20Re port pdf

20 ACLU Report at 24

21 U S Commission on Civil Rights, T he Civil Rights Implications of Cash Bail (Jan 2022) at 7

22 Anita H S Hurlburt, Building Constr uctive Prison Refor m On Norway’s Five Pillars, Cemented With Aloha, 19 APLPJ 2 at 243 (May 2017) (“There are two problematic legal implications created by pre-trial detention: 1) a detained individual has an inferior bargaining position compared to a released individual; and 2) a detained individual’s lawyer exerts much more time and resources and on securing the individual’s pretrial release, which takes time away from building an effective defense ”)

23 Timothy R Schnacke, Fundamentals of Bail: A Resource Guide for Pretrial Practitioners and a Framework for American Pretrial Refor m (Sept 2014) at 15 (citing a 2013 study of over 150,000 individuals by the Laura and John Ar nold Foundation)

24 National Inventory of Collateral Consequences of Conviction, Collateral Consequences Inventor y (last visited Aug 30, 2024), https://niccc nationalreentr yresourcecenter org/consequences

25 Alysia Santo, No Bail, Less Hope: T he Death of Kalief Bro wder, The Marshall Project (June 9, 2015)

26 Id

27 Staff, OCCC inmate indicted in beating death of fello w prisoner, Honolulu Star-Advertiser (Mar 14, 2013)

28 Kevin Dayton, Oahu Inmate Kills Himself After Jail Staf f Fails to Put Him on Suicide Watch, Honolulu Civil Beat (A pr 12, 2023)

29 Kevin Dayton, Another Suicide At T he Maui Jail Leaves a Grieving Famil y to Conclude ‘Something Is Wrong’, Honolulu Civil Beat (July 1, 2024)

30 HCR 85 Task Force Report, at xvi

31 Christopher T Lowenkamp, T he Hidden Costs of Pretrial Detention Revisited, (Jan 2022)

32 Don Stemen and David Olson, Is Bail Refor m Causing an Increase in Crime?, Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation (Jan 2023)

33 See, e g , Kellen Funk, T he Present Crisis in American Bail, 128 Yale L J Forum 1098 (2019)

34 Penal Code of Hawai‘i 1869

35 Penal Code of Hawai‘i 1869 §6

36 Penal Code of Hawai‘i 1869 §6

37 Penal Code of Hawai‘i 1869 §2

38 1892 Haw. Sess. Laws, Chapter XXXII (signed Aug. 25, 1892).

39 Richard F Kahle, Jr , ed , Hawai‘i Constitutional Convention Studies 1978: Introduction and Article Summaries, Legislative Reference Bureau (A pr 1978) at 18-20

40 Haw Const art I, sec 12

41 1980 Haw Sess Laws Act 242, § 3 at 427-28

42 1980 Senate Jour nal, at 1366-67 (S Stand Comm Rep No 756-80 (Judiciary on H B No 2558-80))

43 1980 Senate Jour nal, at 526-30 (statement of Rep Abercrombie on H B No 2558-80, H D 1, S D 1)

44 1980 Senate Jour nal, at 810 (statement of Rep Abercrombie on H B No 2558-80, H D 1, S D 1, C D 1)

45 H Stand Comm Rep No 1038 (Judiciary on S B No 800), in 1987 House Jour nal, at 1602-03

46 1987 Haw. Sess. Laws Act 139, § 8 at 314-15.

47 H. Stand. Comm. Rep. No. 1038 (Judiciary on S.B. No. 800), in 1987 House Jour nal, at 1603 (stating, after noting the concer ns of the Hawaii Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, that “Your Committee has therefore amended this bill to include the federal standards for deter mining bail pending appeal ”)

48 Office of Hawaiian Affairs, T he Disparate Treatment of Native Hawaiians in the Criminal Justice System (2010), at 8

49 Justice Center, The Council of State Gover nments, “Justice Reinvestment in Hawaii: Analyses & Policy Options to Reduce Spending on Corrections & Reinvest in Strategies to Increase Public Safety,” (Aug 2014) Available at: https://csgjusticecenter org/wpcontent/uploads/2020/02/JR-in-HI-Anal yses-andPolicy-Options pdf (hereinafter Justice Reinvestment Report)

50 Justice Reinvestment Report at 2

51 Id. at 4.

52 Id.

53 See Criminal Pretrial Task Force, Hawai‘i Criminal Pretrial Refor m: Recommendations of the Criminal Pretrial Task Force to the T hirtieth Le gislature of the State of Hawai‘i (Dec 2018), https://www courts state hi us/wpcontent/uploads/2018/12/POST 12-1418 HCR134TF REPORT pdf at 31 (hereinafter HCR 134 Task Force Report)

54 Hawai‘i State Bar Association Committee on Judicial Administration, 2016 Criminal Law For um (Sept 2016), https://hsba org/ima ges/hsba/HSBA%20Special%2 0Events%20and%20Prog rams/Bench%20Bar/2016 %20Bench-Bar%20For um%20Re port pdf; see also

Hawaii Bar Jour nal (A pr 2017)

55 Id at 7

56 Id. at 15.

57 Hawai‘i State Bar Association Committee on Judicial Administration, Re port of the 2017 BenchBar Conference (A pr 17, 2018) at 3-6, https://hsba org/ima ges/hsba/HSBA%20Special%2 0Events%20and%20Prog rams/Bench%20Bar/2016 %20Bench-Bar%20For um%20Re port pdf

58 Id at 3-4, 11-13

59 Hawai‘i State Judiciary, House Concurrent Resolution 134 (2017) Criminal Pretrial Task Force, https://www courts state hi us/house-concurrent-resolution-134-2017-criminal-pretrial-task-force

60 HCR 134 Task Force Report at 2

61 Id at 91-92

62 2019 Haw Sess Laws Act 149, § 16 at 58283

63 Testimony submitted to Senate Committee on Ways and Means on H B No 1552, S D 1, Proposed S D 2 , at page 7

64 2019 Haw Sess Laws Act 149, § 20 at 585

65 Testimony submitted to Senate Committee on Ways and Means on H.B. No. 1552, S.D. 1, Proposed S.D. 2., at page 4.

66 See HRS § 804-7 5

67 See id

68 H B 1552 C D 1 (2019); https://www courts state hi us/criminal-justice-research-institute-cjri

69 S B 192 C D 1 (Act 277, 2019), https://www capitol hawaii gov/sessions/session2019 /bills/SB192 CD1 htm

70 DCR was, until 2024, called the Department of Public Safety (DPS)

71 See https://dcr hawaii gov/about/divisions/cor rections/ (“Corrections Population Reports”)

72 Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, State of Hawai‘i De partment of Public Safety End of Month Population Re port (July 31, 2024)

73 Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, State of Hawai‘i, https://dcr hawaii gov/ about/divisions/cor rections/ ((DCR population reports and annual reports).

Wookie Kim is the le gal director at the ACLU of Hawai‘i Samantha McNichols is a le gal fello w at the ACLU of Hawai‘i

H S B A H A P P E N I N G S

Member Benefits Spotlight

HSBA Ne wsstand

Get free timely updates from around the U.S. and the world about subjects that matter to your practice. Newsstand is powered by innovative newsfeed service Lexolog y, which utilizes its global legal knowledge base to deliver essential know-how and market intelligence in concise digestible for m to keep you infor med across legal issues in your area

Activate your account with Lexolog y at https://bit.l y/417oJWa to select the work areas and/or jurisdictions you would like to be kept up to date on

Change your settings (receive the newsfeed weekly or daily) or cancel your subscription at any time Your personal details will remain confidential at all times

Coastal Wealth

Coastal Wealth, a MassMutual fir m, is proud to partner with the Hawaii State Bar Association

Their mission is to help Hawaii’s lawyers navigate insurance service opportunities and redefine member benefit possibilities with exclusive discounts and free industry-trending personal and business plan analyses.

Here are some commonly asked questions:

• What are my risks?

• How do I protect against these risks?

• How do I leverage the marketplace?

• How much income will I have in retirement?

• How long will my income last in retirement?

• What key employee benefits should I consider?

• Do I need a buy-sell ag reement?

If you have other questions, please

schedule an appointment at https://mycoastal wealth.com to meet with Coastal Wealth representatives

Coastal Wealth also offers Health, Dental, Vision, and 401k g roup benefits

Hawaii State Federal Credit Union

HSBA members are eligible for membership with Hawaii State Federal Credit Union. Hawaii State FCU offers low rates on business loans and lines of credit, mortgages, home equity lines of credit, auto loans, and personal loans Additional services include free EChecking accounts, surcharge free access to over 400 ATMs statewide, free online and mobile banking, and much more. Call (808) 587-2700 or (888) 5861056 (toll free).

Honolulu Payroll

Honolulu Payroll LLC was founded to provide simple, effective and affordable payroll with a high level of customer service for local small businesses They will make sure your employer taxes are done on time the right way. They offer direct deposit free of charge and provide a level of human resources support to cover all bases They are excited to team up with HSBA to provide our service to even more fir ms across the state New clients will receive a 10% discount from the monthly fee. Please contact Nick Salisbury, Manager, at (808) 499-9651. You can inquire at info@honolulupayroll com and read more infor mation at www payrollhonolulu com

HSBA Conference Rooms

HSBA conference rooms are available at the Hawaii State Bar Association offices at 1100 Alakea Street, Suite 1000, for HSBA members at $25 per

hour (small) and $50 per hour (large), including telephone and wireless service. Call (808) 537-1868 for availability and see our guidelines located on our website accessible via this link at https://bit l y/3TRtRtf

ADP

Save on payroll, tax and HR solutions for small to mid-sized businesses from ADP. Enroll with National Purchasing Partners (NPP) today to start saving at https://mynpp com/association/ hsba

American Express

American Express has business cards for companies of all sizes. Get built in tools, perks, and rewards for businesses like yours – backed by the award-winning customer service and support of American Express Choose the right solutions for your business Enroll with NPP today at https://mynpp com/association/hsba

Microsoft

Reimagine the way you work Shop for computers, Microsoft 365, software and more for your business Even your employees can access laptops, Xbox and accessories Sign up with NPP for free today at https://mynpp.com/association/hsba and save on a portfolio of brands for your business and employees.

Visit https://hsba org/memberbenefits for more exclusive benefits

Chief Justice Mark E. Recktenwald’s Response to Report of the 2023 Bench-Bar Conference

The report has also been shared with all our judges.

As I do every year, it is my privilege to support the important work of the JAC and provide this response to the conference report

COMMON TOPICS

The common topics this past year focused on key areas that are fundamental to the practice of law and administration of justice: civility, training and continuing education, and communication

INTRODUCTION

On behalf of the Hawai‘i State Judiciary, I want to thank all those who participated in the 2023 Bench-Bar Conference In addition, I express my appreciation to the Hawai‘i State Bar Association (“HSBA”) Committee on Judicial Administration (“JAC”), in particular co-chairs Associate Justice Simeon R Acoba (ret ) and Associate Justice Vladimir Devens, for organizing the conference and preparing the resulting report

The Bench-Bar Conference always provides an invaluable opportunity for the Judiciary to engage in robust discussions with the bar to improve the administration of justice This year, nearly 250 people attended the conference, which was held remotely through the Zoom meeting platfor m on September 29, 2023 Participants included 190 attor neys, over 50 justices and judges, and a number of court administrators. We particularly appreciate those from Maui who participated despite the tragic wildfires, which occurred less than two months before. The Judiciary is committed to carefully considering all of the feedback and comments raised at the conference. As in past years, the suggestions from the report of the 2023 BenchBar Conference were reviewed and considered by me, our Chief Judges, and the Administrative Director of the Courts.

Civility is a core underlying principle of professionalism that contributes to effective advocacy and the integ rity of the justice system I was encouraged to hear that the consensus among most of the g roups was that both the bench and bar are respectful to one another and have embraced the aspirational tenets set forth by the Guidelines of Professional Courtesy and Civility for Hawai‘i Lawyers The discussion around this topic served as a reminder to everyone that we must all work to uphold these values. In the past, a joint Hawai‘i State Trial Judges Association (“HSTJA”) and the HSBA Committee served as a productive forum to resolve these types of concer ns about judges and attor neys in a confidential manner. In her role as President of the HSTJA, Judge Kirstin Hamman has been in communication with HSBA President Jesse Souki about reinvigorating the work of HSTJA-HSBA Committee. I truly appreciate their efforts to pursue this as an option to improve the profession on an ongoing basis.

Over the past few years, the courts have evolved with the integ ration of remote hearings into operations across the state, and accordingly it was an opportune time to discuss how to promote civility in this new environment In August 2023, the Judiciary in partnership with the HSBA co-sponsored a continuing legal education (“CLE”) presentation entitled: “A View from the Bench: Decorum, Ethics and Civility During the Age of Remote and Hybrid Court,” which also touched upon similar issues The panel was led by Judge Melanie May together with Judge Brian Costa, Judge M Kanani Laubach, and Judge James Rouse They discussed courtroom decorum, ethics, and

professionalism, as well as the benefits and challenges of remote hearings, including the expectations for attor neys appearing remotely. The tur nout for this event was excellent, with almost 100 attor neys attending the event live and receiving their mandatory ethics credit. For those of you who were not able to join, a recording of the event is available on the HSBA CLE Webcast Recordings Library

Ongoing training and continuing education are essential to professional development for both the bench and the bar We are committed to providing the judges with training opportunities and convene judicial education conferences twice a year on a diverse range of topics There is a Judicial Education Committee (“JEC”) in place that plans the prog ramming for these judicial conferences held over two days in the fall and in the spring I am g rateful to the JEC for all their efforts throughout the year to ensure these events are infor mative and productive My thanks go out to Judge Gary Chang (ret ) for his longstanding leadership of the JEC over the past 15 years, and to Judge Kevin Morikone who will carry on this work as the current Chair, as well as Supreme Court liaison Justice Todd Eddins.

One of the suggestions from the Circuit Court Civil Groups was that judges should receive unifor m training on the handling of settlement conferences. Following the Bench-Bar Conference last year, I referred this recommendation to the JEC for consideration I am pleased to report that as a result, a two-hour session conducted by the Mediation Center of the Pacific on this issue was included as part of the Spring Judicial Conference held in A pril of this year

Another topic that was recommended as an area ripe for additional training for judges was artificial intelligence (“AI”) At the past two judicial conferences, there were presentations about generative AI, which included a demonstration of the tools being marketed commercially to the public and to

the legal profession, as well as discussion of new rules and court orders from across the country concer ning the use of AI in court proceedings. As interest and widespread use of AI g rows, we must be prepared to respond. In light of this, I established the Committee on Artificial Intelligence and the Courts (“CAIC”) to carefully research and consider how this emerging technolog y might be used effectively in the courts Among other things, the CAIC will: identify AI capabilities, limitations, and risks; explore how to appropriately implement AI into court operations; provide guidance and recommend policies on AI; consider how AI can be used to increase access to justice; and address the legal and ethical issues around using AI in the practice of law I want to express my appreciation to all the members of the CAIC for their collaborative efforts I am especially g rateful to Justice Devens and Judge John Tonaki for taking the lead as co-chairs, and to HSBA President Jesse Souki for ensuring that the interests of the bar are represented I look forward to seeing the Committee’s recommendations on how we can use AI to make the court system more effective and accessible.

Communication was another common topic that was discussed and identified as critically important to the judicial process. As the nature of how we do business has shifted, the way that the court communicates with attor neys and makes infor mation available to the public must also evolve I would like to share a few areas where we have begun to make some improvements based on your feedback

As we shifted to convening both inperson and remote proceedings, there was a request to make court calendars publicly available online at the 2021 Bench-Bar Conference and the same suggestion came up again this year It is something that we have been actively pursuing and in August 2023 we launched a new function on eCourt Kokua, which allows the public to search for infor mation about upcoming hearings

up to two weeks in advance. This new feature provides this infor mation on all case types, except those that are confidential, such as Family Court cases involving minors. To find scheduled hearings by either case identification number or location, navigate to the “Upcoming Court Hearings Search” tab after entering the eCourt Kokua system on the Judciary website If you search by case number, you can view all upcoming hearings associated with that specific case within the next two weeks Alter natively, you can also search by courtroom/division, date, and time to view all cases on the calendar for that specific courtroom The infor mation on the site is updated in real time as hearing dates are entered into the system In addition to the ability to look up a court calendar online, we will continue to have printouts of court dockets posted outside of courtrooms, as has been the prior customary practice Improving communication and operational efficiency is a priority for the Judiciary and we are pleased to offer these added capabilities for attor neys, court users, and the general public. Now that our Judiciary Electronic Filing and Service system (“JEFS”) has been established in all public case types statewide, we are committed to continuing to make improvements to JEFS and moder nize our court system further. One of the most highly requested changes that has consistently been raised by the bar is the desire to have a hyperlink to filed documents through the JEFS system when a Notice of Electronic Filing is sent out I am pleased to report that this project has been funded and we are currently in the early stages of planning to implement this enhancement in the next year We will keep JEFS users infor med of the prog ress as it develops

ISSUES RELATED TO CIVIL PRACTICE

One of the specific topics in the Circuit Court Civil Groups was an update on the implementation of the new civil r u l e s A l t h o u g h t h e n e w c i v i l r u l e s

became effective on January 1, 2022, it has taken some time to see the effects that these changes have had on civil practice. With the tremendous collaborative effort invested in working towards the goal of reducing costs and delay, and streamlining the civil litigation process in Hawai‘i’s circuit courts since 2018, I was pleased to hear the positive feedback shared in the report In particular, it was encouraging to lear n that the revised rules have led to earlier settlement of cases and improvements in trial process However, it was observed that the expedited trial track has been underutilized, so we remain open to further input from the bar on how to increase use of this option and more broadly, how we can continue to make the civil justice system more fair, efficient, and accessible I am deeply g rateful to Chief Judge Jeannette Castagnetti for her steadfast commitment to this work over the years as Chair of the Committee on the Implementation of Rules Promulgated for Civil Justice Improvements

Another topic of discussion in the Circuit Court Civil Groups was motions for summary judgment and Rule 56 of the Hawai‘i Rules of Civil Procedure (“HCRP”). It was noted that HRCP Rule 56 has not been amended in many years and suggested that changes to the rule to extend the filing deadlines for memoranda in oppositions and replies should be explored. I have referred this recommendation and the 2023 BenchBar Conference Report to the Committee on Rules of Civil Procedure and Circuit Court Civil Rules for their review and consideration My appreciation goes out to Judge James Ashford for his strong leadership as Chair of the Committee and as Deputy Chief Judge of the Civil Division in the First Circuit

The District Court Civil Group devoted time to address the benefits and challenges of remote proceedings Since the pandemic, remote proceedings have been implemented statewide and have transfor med the way the courts operate As such, it is critical that we assess what

works and what doesn’t on a regular basis to ensure we continue to administer justice in an impartial, efficient, and accessible manner in accordance with the law, for both attor neys and court users. The consensus was that remote proceedings appear to increase participation, however, practitioners raised that there can be issues with the quality of the equipment in certain courtrooms and suggested that litigants would benefit from additional infor mation and education on appearing remotely The Judiciary has made every effort to keep our website updated, organized and user-friendly, including by having a dedicated page for infor mation about remote hearings We are also mindful that self-represented litigants may need additional assistance, so we have created a page on the Judiciary’s website that conveniently puts together links to key resources all in one place: https://www courts state hi us/self-representedlitigants-srl On this page, you will find a link for “Tips on Going to Court” and the materials provided include a link to a short YouTube video we created last year on the “Do’s and Don’ts of Remote Zoom Hearings,” which was one of the specific suggestions from the bar. You can find the video on our website here: https://www.courts.state.hi.us/selfhelp/tips/tips on going to court and on the Judiciary’s YouTube channel. Some judges even provide this video for litigants to view in the waiting room when they first join a Zoom hearing

In addition, the Judiciary has been working on two new resources to help those navigating the court process on their own, both of which will launch later this year The first is a Fines and Fees Calculator, which is a free online tool that can help anyone figure out the fines and fees owed on certain citations This tool will help educate the individual on the various fines and fees and assess their ability to pay, help anticipate what is expected prior to attending court, and may empower them to request a reduction in the amount owed or request community service if eligible The other is a

chatbot on the Judiciary website that will allow users to ask questions and be directed to specific links and infor mation. This will streamline inquiries from the public and improve access to court information. A court patron will no longer need to wait until the next business day to call the court, when their question could be answered much quicker through the chatbot function, freeing up court staff time so they can address other pressing needs

Another one of the specific topics that was discussed in the District Court Civil Group were settlement conferences and other methods of dispute resolution Practitioners shared that it would be beneficial to have a settlement judge available during retur n hearings to facilitate settlement early in a case Since there are logistical considerations and resource limitations that curtail our ability to have settlement judges standing by at all hearings, we have been working to provide other alter native dispute resolution options In the Second Circuit, mediators are regularly available on site for the small claims and summary possession calendar in Wailuku on Mondays, and these services can also be offered for the same calendars in Lahaina on Thursdays, depending upon caseload. In the Third Circuit, there are in-person mediation services offered at the Waimea courthouse during the Thursday civil calendars held twice a month, and at the Kona courthouse every Tuesday in partnership with the West Hawai‘i Mediation Center In the Fifth Circuit, there are inperson mediators available on answer and retur n hearing dates In addition, the First Circuit has been working with the Mediation Center of the Pacific (“MCP”) to make onsite mediation available at the courthouse, and is also supportive of efforts by the MCP to expand its early eviction mediation prog ram for landlord-tenant cases

ISSUES RELATED TO FAMILY PRACTICE

One of the recurring themes that

surfaced in the Family Law Groups was the essential role that clear and effective communication has on resolving these disputes, whether it be during discovery or before and after court hearings. Moreover, when working with self-represented litigants thoughtful communication becomes even more vital to facilitating cooperation While the consensus was that everyone should uphold the principles of professionalism and civility in all communications, we must also recognize that our family courts are tasked with resolving some of the most sensitive and contentious cases, and should be mindful that many of the parties may have experienced some type of trauma that led them into the justice system in the first place

It is well documented that chronic exposure to trauma can impact the way a person perceives others and responds to the world around them So, what appears as incivility may instead be a reaction g rounded in a person ’ s past experiences, and triggered by what is happening at present Our family court judges and staff have received regular training on trauma over the years, through resources from the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges and the Department of Human Services’ Office of Youth Services and are well equipped to address these issues when they arise. Most recently, traumainfor med care training was provided to all juvenile probation staff in A pril 2024, and included a separate session for supervisors and managers on how trauma-infor med care applies in their role as leaders We continue to explore ways we can implement a trauma-infor med framework, which acknowledges the prevalence of trauma and promotes practices to reduce har m in family court and throughout our institution My thanks go out to Senior Family Court Judge Matthew Viola for his initiative to respond to trauma in our family courts, and to Prog ram Specialist Adriane Abe for her dedication to these issues and eng agement on a statewide level as a

Grief Support Group

Grief is a universal experience and we all struggle with it. By sharing our stories in a safe, confidential, and caring environment, we can find strength and additional resources to deal with our loss. On February 21, 2024, the Attorneys and Judges Assistance Program is starting a new support group for Hawaii's attorneys led by a licensed psychologist. This mental health & grief support group hybrid Zoom meeting will be held every 3rd Wednesday of the month from 12:00-1:00 p.m. Attendees can participate in person, in the AAP office conference room, or virtually through Zoom.

member of the Hawai‘i Trauma-Infor med Care Task Force.

It was also suggested that mandatory initial disclosures could also improve communication and encourage ag reements to occur earlier in the process. These comments have been shared with the Per manent Committee on Family Court Rules for further consideration Thank you to Judge Dyan Medeiros for serving in the role of the Chair of this Committee and for her years of self less service on the Family Court bench

The Judiciary continues to expand services for children and families to ensure that family court can also be a place of transfor mation and healing In the First Circuit, we recently launched Ho‘okanaka, a cultural diversion pilot prog ram to equip youth with the knowledge and skills needed to g row into the best versions of themselves The prog ram was developed in collaboration with the Partners in Development Foundation and additional support from the Lili‘uokalani Trust, Native Hawaiian Legal Cor poration, and the Consuelo Foundation. The concept for the prog ram is to reconnect the youth with the ‘aina, to care for the land, and in tur n lear n about themselves and reconnect with their families. So far, four cohorts have completed the prog ram and I look forward to seeing the Ho‘okanaka prog ram reach even more children in the years to come. Many thanks to Judge Jessi Hall and the juvenile diversion staff for working with our community partners to establish this prog ram