Understanding and Responding to Self-Harm

A guide for education staff and schools in Havering

Content warning: The content of this needs assessment may be emotionally challenging as it discusses suicidality and self-harm. Support is available:

• Samaritans – a listening service which is open 24/7 for anyone who needs to talk.

• Shout – a free confidential 24/7 text service offering support if you're in crisis and need immediate help.

For queries about this toolkit, please email publichealth@havering.gov.uk

Introduction

Purpose of document

• This guide is designed to provide a shared understanding of self-harm, including its warning signs, underlying causes and effective strategies for support and prevention.

• It should be used alongside existing school safeguarding policies.

• When in doubt about how to respond to a young person’s self-harm, always seek advice including from mental health professionals where necessary.

Understanding self-harm

What is self-harm?

Self-harm is any act of intentional self-injury or self-poisoning (e.g., cutting, burning, hair pulling); it is anything that intentionally causes pain or harm to oneself.

Self-harm affects at least 10% of people. It is more common among females than males, particularly in early adolescence. In children under 11, self-harm is less frequent but more common among boys and may present differently (e.g. scratching, picking scabs, headbanging, reckless behaviour).

Recognising signs of self-harm

Young people often hide self-harming behaviours, but possible indicators include:

• Unexplained cuts, burns, bruises or scars

• Consistently covering up (e.g. long sleeves in hot weather) or avoiding activities like swimming or P.E. lessons

• Frequent bandages

• Unusual objects that could be used to injure (razors, lighters, microblading tools etc.)

• Withdrawal, low mood or sudden behavioural changes (irritability, aggression)

• Excessive self-blame, hopelessness or loss of interest in usual activities

Many staff worry about asking young people about self-harm or suicidal thoughts. Research shows that asking does not put the idea into a person's head.

Sometimes negative terms are used for self-harm, such as ‘attention-seeking’ or ‘manipulative’.

This language is unhelpful and may make it harder for young people to open up or ask for help. Some young people do need attention but aren’t able to find a positive way to get it.

Some injuries may be attributed to implausible explanations (“the cat scratched me”), and signs can overlap with those of physical abuse. Always keep the door open for conversation, without pushing: “Okay, well if you ever want to talk about anything, I’m here.”

The link between self-harm and suicide

• Both self-harm and suicide often arise from similar underlying issues, such as depression, trauma or overwhelming stress.

• Many young people self-harm to cope with emotional pain rather than to end their life. However, a history of self-harm is one of the strongest predictors of future suicide attempts, especially if suicidal thoughts are present.

• Repeated self-harm can desensitise individuals to pain or death, increasing future suicide risk.

• Early identification and mental health support can reduce both immediate harm and long-term suicide risk.

Which young people are most vulnerable to self-harm?

Individual Factors

• Depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, hopelessness

• Impulsivity

• Poor problem-solving

• Drug/alcohol misuse

• Neurodivergence (e.g. autism, ADHD)

• Eating disorders

Family Factors

• Parental mental health difficulties

• Family conflict, neglect or abuse

• Substance misuse within the household

• Family history of self-harm

• Change to family dynamic

Social Factors

• Bullying or peer rejection (including cyberbullying)

• Friends who self-harm or influence from social media

• Exposure to suicide or self-harm by public figures

• Easy access to means of self-harm

Whilst the above factors are known to increase the risk of self-harm, it is not the case that a person must have experienced one or more of these risk factors to then engage in self-harm.

Why do young people self-harm?

Self-harm serves different functions for different people, including:

• Coping with emotional distress

• Reducing tension or overwhelming feelings

• Distracting from emotional pain through physical pain

• Expressing anger, frustration or self-punishment

• Regaining a sense of control

• Seeking care or identifying with a peer group

In some cases, self-harm can be a suicide attempt, but often it is a way of avoiding suicide by coping with intense emotions.

Events that may trigger a self-harm episode

• Family difficulties, particularly common in younger adolescents

• Difficulties with peer relationships, e.g. break-up of a relationship (the most common trigger for older adolescents)

• Bullying

• Significant trauma (e.g. bereavement, abuse)

• Self-harm behaviour in other students (contagion effect)

• Self-harm portrayed or reported in the media

• Difficult times of the year (e.g. anniversaries)

• Getting into trouble in school or with the police

• Feeling under pressure from families, school or peers to conform/achieve

• Exam pressure

• Times of change or transition (e.g. parental separation/divorce, relocation)

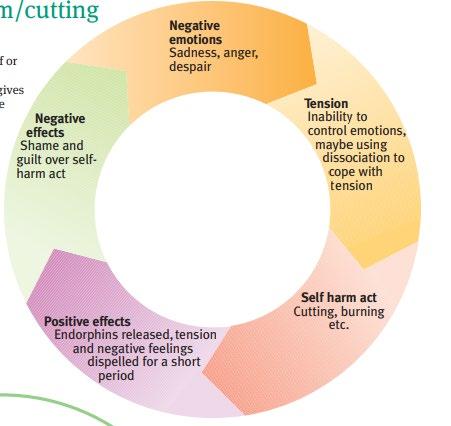

The cycle of self-harm

Self-harm may temporarily reduce distress through endorphin release. This can create an addictive cycle, making self-harm difficult to stop without healthier coping strategies (Figure 1: The Cycle of Self-Harm).

Common myths debunked

“Only females selfharm.”

“Self-harm is a suicide attempt.”

“Only teenagers selfharm.”

“People who self-harm are dangerous.”

“Self-harm is just attention-seeking.”

“Self-harm can’t be treated.”

“All people who selfharm have Borderline Personality Disorder.”

“People who self-harm enjoy the pain or they can’t feel it.”

“There’s nothing I can do to help.”

“They can stop if they really want to.”

30–40% of people who self-harm are male.

Most self-harm is a coping strategy, not a suicide attempt. Although self-harm is a risk factor for future suicide.

People of all ages self-harm, including children and adults, and can come from all backgrounds, cultures, and social groups.

Self-harm is usually a private coping mechanism, not a sign of violence towards others.

Most people hide their injuries. If injuries are seen this can signal a need for help, and that a person might be seeking connection with/from others.

With the right support (e.g. safety plans, therapy, medication), many people recover or find safer ways to cope

People who self-harm may have a range of mental health conditions (or none).

Most people who self-harm feel pain but use it to cope, externalise or actualise emotions, or to feel something.

Listening without judgment, staying supportive and offering resources can make a difference.

Self-harm can be addictive due to endorphin release and may require support to stop.

Hear from young people in Havering

1. What are the most effective ways to communicate to young people about sensitive topics like suicide and mental health?

“I think the best way to communicate to young people about sensitive topics is by talking ... in a comforting and enthusiastic manner. Young people may feel undermined or told off when being asked to speak about these topics, and shouldn’t feel pressured when speaking about how they feel”

"I think trying to destigmatise mental health with the language we use to describe it is very important. e.g. ensuring young people don’t feel they are abnormal when they are going through something"

"Sometimes you may need to stress the severity of the situation as some young people may not take it seriously enough"

"Education on these topics from a younger age"

"Educate people through school. [Self-harm] can be spoke about more frequently so people are more aware and can feel comfortable talking and speaking out if ever struggling, as they will then know support is there."

"The most effective way to communicate to young people about sensitive subjects is being direct as sugarcoating may lead to them misunderstanding the seriousness of the situation."

2. Where do you think young people feel most comfortable in seeking help if having thoughts of selfharm or suicide?

"Friends they trust"

"Talking to close family/friends. Young people would find it easier to get professional help from a wellbeing team at school"

"Their friends. Maybe would also seek help from family or the school dependent on the person or the situation"

"Online because they do not feel as exposed as it can be more anonymous"

"Conversations through a screen –message –calls –Zoom –etc"

"Friends about mental health as they do not feel judged"

"I think we would feel most comfortable talking to our friends or trusted adult"

"online resources are good...because it removes the aspect of fear and possible shame that comes along with talking about your situation"

3. What can schools do better to educate and communicate with young people about the risks of selfharm/suicide and the importance of seeking help?

"Speaking to young people before parents"

"Advertising mental health services"

"Teachers should be less strict and more welcoming. Reminding children that they are humans too and are willing to support and be there for them"

"Having a way to anonymously seek help"

"Speak more about mental health, making it more important"

"Educate parents on mental health. Show statistics to children to highlight the reality of it. Have a support system in place. Have conversations about these topics"

"Maybe they could volunteer to lend an ear"

"Emphasise to us that they are not alone and they should not suffer in silence"

"Schools should have interactive sessions with students about self-harm and suicide to engage them in learning how to deal and support those struggling in these situations"

"Schools can acknowledge how academic stress can lead to worse mental heath as feeling seen helps a lot "

"Speak more about mental health, making it more important"

"Schools could treat students a bit more like adults as how can a young person be expected to talk about grown up issues in an environment where they’re treated like a child?"

"Parents should be informed on how to encounter such situations, whether it is though a workshop or open discussion at school. As our parent’s generation may have a stigma, or especially from when they grew up, they may have been taught little knowledge about mental health"

How to approach a young person about self-harm

As a staff member, you may be the first to notice signs that a young person is self-harming. This can be emotionally challenging for staff, and it’s normal to feel uncertain about what to do. It is important not to dismiss your concerns. Young people are more likely to open up if you approach them with calmness, empathy and without judgment.

Starting the conversation

Begin by gently sharing your observations and showing concern for their wellbeing:

“I’ve noticed that you’ve seemed more withdrawn/irritable/angry lately, and I’m wondering if things are difficult for you at the moment?”

If you have specific concerns about self-harm, it’s okay to ask directly:

“I’ve noticed [e.g. scars/covering up with long sleeves], and sometimes that can be a sign of selfharm. Can I ask if you’ve been hurting yourself? I want to support you.”

Being direct and compassionate helps the young person feel safe.

Helpful questions and statements

The aim is to encourage the young person to explain what self-harm means for them. Showing that you understand some of the reasons people self-harm can help reduce stigma and build trust.

Examples you could use:

“Can you tell me what was happening before you self-harmed?”

“Sometimes people self-harm as a way of coping with really strong feelings. Do you think that might be the case for you?”

“I know people self-harm for lots of different reasons and emotions. Can you help me understand what it means for you?”

Other supportive statements:

“You must be feeling very upset about something. I’d like to help if I can…would it help to talk about what’s troubling you?”

“It can feel like self-harm is the only way to cope, but there are other strategies too. Would you like me to show you some leaflets or websites with ideas that others have found helpful?”

“Before you go, I’d like to give you some information about people you can contact if you feel like self-harming again.”

Using “I” statements

Framing your concern through “I” statements helps avoid judgment and makes the conversation feel personal and supportive:

“I’m concerned about you and want to be sure you have the support you need.”

“I’m worried about you. I’ve seen these scars on your arms and I think you might be hurting yourself. If you are, I want you to know you can talk to me. If not me, I hope you can find someone you trust to talk to.”

This approach demonstrates care while leaving space for the student to respond in their own time. Avoid “we” as it signals that conversations have been had about them without their knowledge and input. It’s also important to ensure the message doesn’t shift the focus onto your feelings (e.g., “I get sad too, sometimes”). Instead, keep focused on the young person’s feelings and what they’re saying

Responding to self-harm in young people

Understanding circumstances and levels of concern

All self-harm should be taken seriously. It is important to try to understand the context and reasons behind the behaviour, while remembering there are no strict rules. When in doubt, always seek guidance from mental health professionals.

• Trust your instincts. If you worried about a student or even start notice concerning changes, share your concerns the safeguarding lead.

• Seek professional input. If you are unsure about the level of concern, consult Havering Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS). (www.nelft.nhs.uk/havering-camhs/)

• Safeguarding considerations. Self-harm can sometimes arise as a response to abuse or exploitation. If this is suspected, treat it as a safeguarding concern and refer to children’s social care as per local safeguarding processes.

Indicators that a student may need more immediate support

If a student has self-harmed and any of the following are present, they may require more urgent or intensive support to ensure their safety and wellbeing:

• Low mood, particularly if this is a recent change in mood.

• Behaviour change; becoming withdrawn, isolated, disruptive, or unusually animated. The change itself may signal a problem.

• Expressing hopelessness e.g., “I can’t see a future” or “What’s the point?”

• Low self-worth or self-hatred e.g., “I’m useless” or “Nobody cares about me.”

• Lack of family support or distant family relationships. This may need gentle questioning to uncover.

• Expressing suicidal feelings. This can be explicit (“I want to die”) or indirect (“I can’t go on,” “I don’t want to be here”). It is safe to ask directly about suicide, and doing so does not put the idea into their head.

• Previous self-harm. Always ask if they have harmed themselves before.

• Signs of abuse or sexual exploitation.

• Bullying including cyberbullying

• Use of websites encouraging/advocating for suicide or self-harm.

• Gender or sexuality identity difficulties.

• Excessive use of drugs or alcohol

• Recent history of self-harm or suicide in a friend or family member

• Bereavement; especially a recent or significant loss.

Responding when there are indicators of greater concern

If there are indicators of higher concern:

• Explain you are concerned and want to help them access support. Be open about seeking advice from Havering CAMHS and keep them informed of actions taken.

• Share concerns with the school nurse, head of year, counsellor or designated safeguarding lead.

• Continue offering consistent support and listening.

• Involve parents/carers, for example by arranging a meeting in school.

• Be mindful of the student’s peer group, as they may also need support once the immediate crisis has been addressed.

• Ensure that you take care of yourself, treating yourself with the same kindness and patience you’ve offer to the student.

Responding when concerns appear less immediate

Even when situations feel less acute, a response is still required. “Less immediate concern” does not mean “no concern.” Steps include:

• Support and listen to the student, exploring ways to help them feel safe and understood in school.

• Encourage the student to reflect on what emotions or situations led to self-harm (e.g. anger, sadness, fear, overwhelm, disconnection).

• Explore possible alternatives to self-harm that might help them cope more safely (see Support and Resources section of this guide).

• Discuss with the student the idea of involving their parents/carers. Young people may be reluctant to tell their family, so encourage them to consider the benefits and think through how to have that conversation.

• Involve parents/carers directly, especially for younger children, to coordinate support at home and in school.

• Provide information about other sources of support (see Support and Resources section of this guide).

• Continuing to check in with the student over time. A young person’s needs can change, and ongoing monitoring is important.

Managing the immediate effects of self-harm

Physical injuries:

• Remain calm and follow first aid procedures for cuts, burns or wounds.

• Call emergency services if there are serious injuries or if an overdose is suspected; if an overdose is suspected, the student must be taken to hospital for tests and treatment.

• Always ask the student if they are in pain. While they may have sought pain at the point of selfharm, they may not wish to remain in pain afterward.

• Involve the school nurse where possible to provide appropriate care and pain relief.

Emotional Care:

• Identify a key member of staff the young person trusts and is willing to talk to, recognising that this may be you and if so, do not seek to “pass the person on” to someone else. Ask if you can involve another person to help support and if the person has a preference for who else can be included

• Acknowledge that self-harm often communicates distress; validate their feelings and let them know support is available.

• Reassure the student that while self-harm may help them cope now, safer alternatives exist.

• Signpost to other sources of help, such as helplines, GPs, school counselling or trusted family members (see Support and Resources section of this guide).

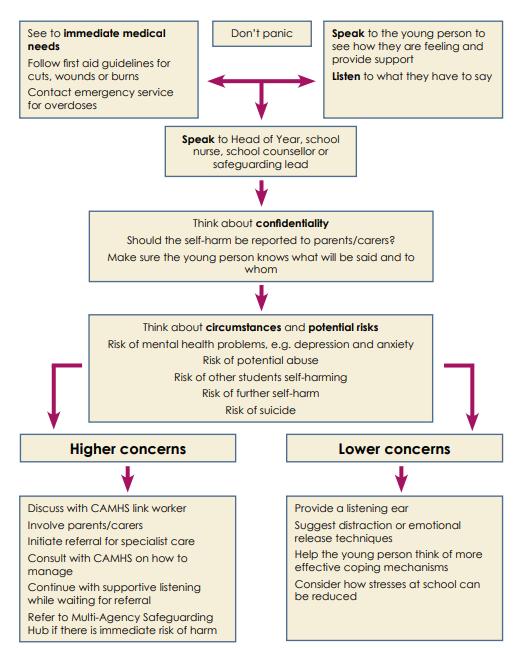

Self-harm at school: what to do?

To be used in conjunction with the school’s safeguarding policy

Figure 2: Self-harm at school - what to do.

Source: young-people-who-self-harm-a-guide-for-school-staff.pdf

Confidentiality and communicating with parents

Confidentiality is important, but staff must remember they cannot promise total secrecy, in line with safeguarding responsibilities. Any disclosure of self-harm must be shared with the Designated Safeguarding Lead (DSL). Information will usually also be shared with parents/carers, unless doing so would increase the risk of harm (e.g. in cases of possible abuse at home).

• Discuss the need to involve parents with the student first. Listen to their concerns and explain clearly why involvement is important.

• Always inform the student before contacting parents/carers. Excluding them from the process can increase feelings of distress or loss of control.

• Consider inviting parents/carers into school to meet with staff and the young person together, to understand the behaviour and plan support.

• Parents/carers also need information for themselves so that they can access help if needed.

Important: Never promise confidentiality you cannot keep.

Working with parents and carers

Parents may react in a wide variety of ways. Some will respond calmly and seek support, while others may struggle with shock, denial, guilt, anger or distress.

It is important to talk about what you can and can’t keep confidential

Don’t make promises of confidentiality that you can’t keep Work on a need-toknow basis

Involve parents wherever possible

• If parents feel guilty: They may believe their child’s self-harm is their fault. Gently remind them they can also seek support or counselling for themselves.

o ‘I recognise that this conversation can bring up a lot of feelings. Your wellbeing is also important and there are support services you can get in touch with to help. Would you like to find out more? Feel free to have a think about it and let us know and we can point you in the right direction if this is something you would like to explore.’

• If parents are dismissive: Encourage them to recognise and respond to their child’s needs.

o ‘I can see that this a big thing to digest, and it can take some time to process it. However, this is about ______’s wellbeing and their needs and they need you to acknowledge how they are feeling and be open to them getting the support they need.’

• If parents are angry or hostile: Emphasise that their child is struggling and needs understanding and compassion.

o ‘I understand that hearing something like can bring up a lot of different emotions, and you may need some time to explore why you feel the way you do about ______ self-harming. Right now, ______ needs you to put that aside and give them the space to be met with some understanding and compassion even if it may initially be difficult for you to do’

• If reactions are extreme: Suggest outside counselling or professional support for the parents themselves.

• If parents are absent, unable or unwilling to engage: The school must step in as advocate, seeking additional resources or crisis support for the young person. In some cases, financial barriers may need to be addressed with external help.

While parental reactions should be validated, it is important to recognise that certain parental attitudes (e.g. minimising, dismissing, or shaming) can worsen or maintain self-harming behaviour. Staff should remain vigilant and seek further support if this occurs.

Impact of self-harm on school staff and the wider school community

Emotional impact on staff

Discovering that a student is self-harming can be deeply distressing. Staff may feel sadness, shock, anger, fear, disgust, frustration or helplessness. These emotions are normal, and because the harm is selfinflicted, some staff may find it harder to empathise than with accidental injuries. Helpful strategies for staff include:

• Be honest with yourself about your emotional responses.

• Talk through your feelings with trusted colleagues, supervisors or managers.

• Seek appropriate support (professional or peer).

• Prioritise your own health and wellbeing.

• Recognise the important role staff can play in supporting students who self-harm.

Contagion and peer groups

Social contagion refers to behaviours like self-injury spreading within a group once members become aware of it. Some behaviours are particularly prone to contagion because they communicate distress powerfully while also carrying stigma. Unintentional reinforcement, even from adults, can contribute.

One student’s self-harming behaviour can sometimes influence others. This is more common with selfcutting and more frequently seen among girls.

Preventing social contagion in schools

• Minimise detailed communication about self-injury among students.

• Discourage explicit discussion of self-harm behaviours between peers.

• Support students in managing scars and wounds discreetly to reduce visibility.

• Avoid giving explicit details about self-harm in school-wide settings. Assemblies on self-harm are not appropriate.

• Instead, educate students about recognising distress, supporting one another and developing positive coping skills.

• Treatment and support for self-injury should always be provided on an individual basis, never through group therapy.

If a student approaches you about a friend’s self-harm:

• Reassure them that speaking to staff was the right thing to do.

• Acknowledge their concern and let them know they have been a good friend.

• Offer them access to the school counsellor if available.

If more than one student has self-harmed:

• Remain calm and do not panic.

• Monitor the situation closely and raise awareness of support options.

• Provide support individually, not in large group settings like assemblies.

Supporting peers and friends:

• Normalise strong emotions. Let them know it is okay to feel deeply at times.

• Encourage mutual care and remind them to share concerns with staff.

• Promote positive ways of coping with stress or distress.

• Highlight sources of support within and beyond the school.

• Share useful resources where appropriate (see Support and Resources section of this guide)

Note: If a student dies by suicide, the likelihood of self-harm or suicidal behaviour among peers can increase. It is vital to protect the wellbeing of other students. Public Health England guidance for schools is available: Suicide Prevention: Identifying and Responding to Suicide Clusters

Support and resources

Practical

strategies

Building support networks

Help young people identify trusted supporters (e.g., friends, family, staff, crisis lines). Ensure they know how to access immediate help in a crisis.

Distraction activities

• Encourage safer activities to replace self-harm, tailored to the student’s interests

• Physical activity: walking, running, sport

• Going out: cinema, library, shops

• Creative outlets: reading, writing, drawing, music

• Caring for pets

• Relaxation: warm bath, soothing routines

Managing physical stress

Strategies to ease tension and reduce urges include:

• Clenching ice cubes in the hand until they melt

• Hitting a pillow or soft object

• Paced breathing (extending the breathing):

o Sit comfortably

o Breathe in to the count of 4

o Breathe out to the count of 6

o Notice your stomach moving out as you breathe in

• Counting (allows the body to slow down) e.g. count 10 films, 10 animals, 10 flowers, etc.

• Engaging in physical exercise

• Relaxation exercises

Expressing difficult emotions

Encourage safe expression of feelings:

• Writing, drawing or talking about feelings

• Writing a letter expressing feelings (which need not be sent)

• Trying to describe feelings

• Keeping a diary

• Talking to others about feelings

Making the environment safe

Work with the student and family to reduce access to harmful items (e.g. razors, medications).

Safety plans

A safety plan is a tool for helping someone navigate feelings and urges to self-harm. It can also be a way for you and the person you’re supporting to plan how to communicate and check in with each other going forwards. It takes around 20-40 minutes to complete. The most successful safety plans are made with the person, not for the person.

A safety plan includes positive self-talk, calming techniques, crisis contacts, safe places and restriction of harmful items. Ask: “Do you have a safety plan?” “Would you like help putting it into action?”

Please see Havering’s Safety Plan tab for more information, including a downloadable template.

Or Download the Stay Alive App that includes a safety plan with customisable reasons for living, a LifeBox where you can store photos and memories that are important to you, strategies for staying safe and tips on how to stay grounded when you're feeling overwhelmed, guided-breathing exercises and an interactive Wellness Plan

You can also encourage students to create a “hope box”, which is a physical or digital collection of positive reminders (photos, affirmations, favourite songs, kind messages, happy memories).

Local

and national support

Information and support for young people:

• Childline: Tel: 0800 1111

• Papyrus: www.papyrus-uk.org

• Young Minds: www.youngminds.org.uk

• Samaritans: www.samaritans.org Tel: 116 123

• Harmless: www.harmless.org.uk

• National self-harm network: www.nshn.co.uk

For children and young people engaging in self-harm

• Alumina: A free 7-week online course for young people struggling with self-harm with trained counsellors and youth workers. Anonymous participation via chat box.

• The Mix: Support for young people. Connects young people to experts and peers to talk everything from money to mental health.

• Kooth: Free online mental health support, including counselling, articles, discussion boards and goal-setting tools.

• Asking for help mental health resource for young people: Practical guidance on taking the first steps towards support.

• Calm Harm: Designed to help individuals resist or manage the urge to self-harm. Recommended for ages 13-19.

• DistrACT App: Provides quick, easy and discreet access to information and advice on self-harm and suicidal thoughts. Recommended for ages 11+.

• Tellmi: Fully moderated app offering resources and a supportive community where users can share their problems, seek help and support others. Recommended for ages 11+.

• Discovery Journal: Free self-harm management workbook for 10-17 year-olds.

For parents of children engaging in self-harm

• Coping with self-harm: advice for parents and carers

• Parents A-Z Mental Health Guide

• HealthTalk: Real stories from parents of young people who self-harm.

• Charlie Waller Trust videos: Video guidance for parents of self-harming children.

For education staff of pupils engaging in self-harm

• Young People Who Self-Harm: A Guide for School Staff

• Mentally Healthy Schools: An online hub with resources on self-harm awareness and student support.

Resources for Havering schools

• This guide

• Building suicide-safer schools and colleges: a guide for teachers and staff: www.papyrusuk.org/repository/documents/editorfiles/toolkitfinal.pdf

• Hub of Hope Service Directory for Havering

• See Local and National Support for suicide prevention

• See Leaflets and Practical Resources for list of full support:

o For adults engaging in self-harm

o For children and young people engaging in self-harm

o For parents of children engaging in self-harm

o For education staff of pupils engaging in self-harm

o Support and wellbeing resources for people from racialised communities

o Safety Plans

• See Training Opportunities training session across North East London, including in Havering.

Document references

This guide was made using information from the following documents:

1. young-people-who-self-harm-a-guide-for-school-staff.pdf

2. https://www.oxfordhealth.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/self-harm-guidelines-for-schoolstaff.pdf

3. Recommendations | Self-harm: assessment, management and preventing recurrence | Guidance | NICE

4. Schools Fact Sheet

5. Findings from the Havering Youth Council Focus Group on Suicide Prevention and Self-Harm.

6. Self-Injury Awareness – A Guide for Parents and Caregivers - Effective School Solutions

7. Helping Self-Harming Students

8. young-people-and-self-harm-guidance-for-schools-10-17.pdf

9. young-people-and-self-harm-guidance-for-schools-10-17.pdf