Havering Suicide Prevention Toolkit

For anyone living, working, volunteering or spending time in Havering

Content warning: The content of this needs assessment may be emotionally challenging as it discusses suicidality and self-harm. Support is available:

Samaritans: a listening service which is open 24/7 for anyone who needs to talk.

Shout: a free confidential 24/7 text service offering support if you're in crisis and need immediate help.

• You can find our easy-read information sheet on preventing suicide here

• We also offer an overview of suicide prevention in multiple languages here, and an overview of selfharm prevention in multiple languages here. Please remember to use the accessibility tools located at the top of the page.

For queries about this toolkit, please email publichealth@havering.gov.uk

Purpose of document

Introduction

This toolkit provides a shared understanding of suicide and suicide prevention. It includes a background overview of suicide and suicide prevention, stigma (what it is and how to reduce it) and practical tools to build confidence to help prevent suicide in Havering

Why suicide prevention matters

• Suicide can often be prevented, and everyone in the community has a role in helping to keep people safe.

• On average, one Havering resident dies every three weeks.

• Research shows that each death by suicide affects around 135 people, including family, friends, colleagues and the wider community 1 .

• Research shows about 1 in 5 people in the UK will experience suicidal thoughts at some point in their life, and about 1 in 20 will make a suicide attempt during their lifetime 2

• People bereaved by suicide may face intense emotions, stigma and isolation, and research shows they may be more vulnerable to suicidal thoughts themselves 3 .

Looking back at my lowest moments, at that time I wanted to end my life …. I just wanted to stop how I was feeling, and that is how I now define the difference between stop (final), and pause.

-Anna, Havering Lived Experience Advisory Group (LEAG) Member

Understanding

suicide

Some important definitions

Suicide; when someone intentionally ends their own life.

Non-fatal suicide attempt; when someone tries to end their own life but does not die.

Suicidal ideation; thinking about ending your life, ranging from fleeting thoughts to detailed planning.

Suicide prevention; actions that help reduce the chance someone will try to take their own life.

Stigma; a negative label or attitude that makes people feel ashamed or excluded. This can include stigma experienced from others (external) and stigma held by the person themselves (internal).

Suicide attempt survivor; someone who has survived a previous suicide attempt.

Suicide loss survivor / bereaved by suicide; family or friends who have lost someone to suicide.

Postvention; support provided to anyone affected after a suicide.

Inequality and understanding cultural barriers and stigma 4

• People living in more deprived areas are 2–3 times more likely to attempt suicide.

• People from disadvantaged backgrounds may experience more stressful life events (e.g., job loss, bereavement or relationship breakdown) and often face greater barriers in accessing mental health care.

1 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9790485/

2 Understanding Suicide - Grassroots Suicide Prevention

3 https://www.ucl.ac.uk/news/2016/jan/1-10-suicide-attempt-risk-among-friends-and-relatives-people-who-die-suicide

4 Samaritans_Dying_from_inequality_report_-_summary.pdf

• Poverty fuels feelings of shame, hopelessness, entrapment or being a burden.

• Environmental factors such as poor-quality housing, limited green space and unreliable transport can increase stress and contribute to social isolation.

• Coping with adverse situations often involves harmful behaviours (alcohol and substance use, smoking, poor diet) which worsen physical and mental health and add to suicide risk.

Suicide is Not Evenly Distributed –Inequality Shapes Risk

Stigma

e.g. Some people are taught through faith or culture that feeling suicidal is a sin, making it harder to talk openly.

Barriers to Care

e.g. Refugees and asylum seekers may face language barriers, making it harder to access mental health care.

Wider Determinants

e.g. Disabled people may face discrimination, poverty or exclusion, all of which increase risk.

See Inequalities section of Havering All-age Suicide Prevention Strategy 2025-2030 for more information.

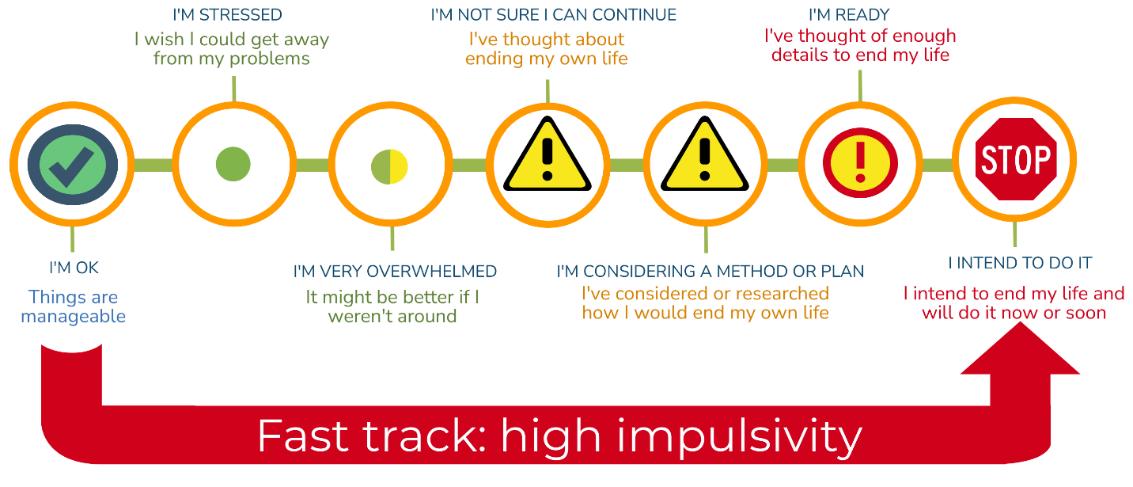

People can experience suicidal thoughts in different ways. These thoughts can vary in clarity, intensity and immediacy. Instead of categorising people as “low” or “medium” or “high” risk, it is more helpful to understand what the thoughts involve and what support the person needs right now. Examples of how suicidal thinking can present include:

1. Vague thoughts of escape: a wish to disappear or stop emotional pain, without thoughts of death.

2. Passive suicidal thoughts: thoughts that life may not be worth living or that death might be preferable, with no intention or plans.

3. Active suicidal thoughts: thinking about ending one’s life but without a specific method or plan.

4. Thoughts involving preparation: considering methods, imagining how it might happen or taking preparatory steps.

5. Thoughts with intent and planning: having a clear method, plan or intention. This situation requires immediate support from emergency or urgent mental health services.

Helpful questions to understand how someone is feeling include things like, “Do you have a method?”, “Have you made a plan?”, or “Do you intend to act?” These questions help to understand the person’s immediate needs. Some factors may contribute to someone having higher impulsivity, including:

• Substance use

• Bipolar disorder

• ADHD

• Traumatic brain injury

• Significant history of trauma

• Young age (i.e. pre-adolescence)

• Intellectual disability

The link between self-harm and suicide

• Self-harm and suicide can arise from similar underlying difficulties, such as overwhelming distress, trauma or mental health problems.

• Many people who self-harm do so to cope with emotional pain rather than to end their life, however a history of self-harm is one of the strongest predictors of future suicide attempts, especially if combined with suicidal thoughts.

• Repeated self-harm can desensitise individuals to pain or death, increasing the likelihood of a suicide attempt.

• Early support, including mental health intervention, can reduce harm and improve long-term outcomes.

Postvention

Postvention is the support provided to anyone affected after a suicide. It is important to have a clear and supportive postvention plan in place in workplaces and all other environments where people are in close contact, such as schools and colleges. Effective postvention:

• Ensures timely and appropriate care.

• Helps people grieve and recover.

• Helps prevent additional suicides.

• Supports organisational recovery (e.g., reduces staff sick leave).

See the Havering webpage, Strategies and Guidelines, for links to postvention toolkits including a toolkit for the general workplace and specific guidance for schools, the NHS and Police

The nature of suicide bereavement

• Bereavement after suicide can involve intense and conflicting emotions, such as guilt, anger or confusion; those with lived experience often call this “grief with the volume turned up.”

• Those bereaved may face societal stigma or feel isolated, which can make open discussion about the death more difficult.

• Those bereaved by suicide have a higher likelihood of experiencing mental health challenges or suicidal thoughts compared to people bereaved by sudden natural causes.

• Many people bereaved by suicide find that specialist support groups or counselling can be more helpful than general grief support.

• There is no single “correct” way to respond; each individual’s grief is unique and may change over time.

Breaking down stigma

Stigma can make people feel ashamed or judged for experiencing suicidal thoughts, which can prevent them from seeking help. It shapes how people are perceived and treated, and how they view themselves. Stigma is often reflected in our language and behaviour 5 Types of stigma include:

1. Public/personal stigma: negative stereotypes and labels (e.g., “selfish,” “took the easy way out”).

2. Self-stigma: when individuals internalise negative beliefs, leading to thoughts such as “I should just snap out of this.”

I thought no one could understand how lost I felt. But then someone did—and it changed everything. It felt like I was drowning in silence. But slowly, words came and so did relief. -Sandeep, Havering Lived Experience Advisory Group (LEAG) Member

Language matters

• Use respectful, clear, and non-blaming or neutral language:

o Say “died by suicide” instead of “committed suicide.”

o Say “survived a suicide attempt” instead of “failed attempt.”

o Describe someone as “experiencing suicidal thoughts/ideation” rather than “is suicidal.”

o Avoid alarmist terms like epidemic or skyrocketing; instead, use neutral words like rising or increasing.

• Be direct and compassionate: asking about suicide doesn’t cause it, rather it can reduce isolation. Encourage seeking help from professionals or trusted people.

5 StandBy Support, Managing social stigma after suicide https://standbysupport.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/8.-Managing-social-stigma-after-suicide-support-pack.pdf

“People will always find a way.”

“Suicide can’t be prevented.”

“It happens without warning.”

“Asking about suicide encourages it.”

“Only people with mental illnesses can feel suicidal.”

“Suicide is selfish.”

“Talking about suicide is attention-seeking.”

“Once someone feels suicidal, they will always feel suicidal.”

“Self-harm is always linked to suicide.”

“If someone is serious, there’s nothing you can do.”

“Bereaved people don’t want to talk.”

Making it harder to access to means lowers suicide rates 6

Early support, awareness, and safety steps can save lives 7

Most people show warning signs or tell someone first.

Asking directly shows you care and can bring a lot of relief and open conversation.

Many who struggle are undiagnosed or facing other problems.

It usually comes from pain, hopelessness or feeling like a burden.

It’s a serious cry for help that needs support.

Thoughts and feelings can change, especially with proper support.

Many engage in self-harm to cope with no intention to end their life; but always check gently.

Staying, listening and getting help can make a real difference.

Many want to share memories and keep loved ones remembered.

“Only professionals can help.” Anyone can help someone who is feeling suicidal.

Risk factors

Personal risk factors

• Previous suicide attempt

• History of depression, anxiety, mood disorders or other mental illness

• Substance misuse

• Serious/chronic physical illness or chronic pain

• Living with a neurodevelopmental or intellectual condition (e.g., autism, intellectual disability)

• Adverse childhood experiences

• Young age (pre-adolescence)

• Impulsivity (can be linked to substance use, neurodivergence, bipolar disorder)

• Trouble with the police / legal problems

• Job/financial problems or family financial stress

Relationship and Family Risk Factors

• Bereavement (including suicide in the family)

• Family breakdown or instability

• Parents/carers with mental health issues or substance misuse

• Exposure to domestic violence

• Care experienced / living apart from primary caregivers

• Young carer responsibilities

• Previous suicide in family or close circle

• High-conflict or violent relationships

Community risk factors

• Lack of access to healthcare, mental-health services or school support

• Suicide cluster in the community

• Community violence

• Stress of acculturation (migration/adjustment)

Societal and structural risk factors

• Stigma around help-seeking and mental illness

• Easy access to lethal means (in the home or community)

• Discrimination (e.g. racial, sexual orientation)

• Historical or community trauma

• Unsafe/irresponsible media reporting of suicide

Peer, school and social risk factors

• Bullying and cyberbullying/trolling

• Social isolation or friendship breakdown

• Academic pressure (e.g., exams, results stress)

• Feeling disconnected from school/community

• Identifying as LGBTQIA+ and/or experiencing stigma, discrimination or rejection

• Seeing suicide-related content on social media

Protective factors 8

Individual Protective Factors

• Effective coping and problem-solving skills

• Reasons for living (e.g., family, friends, pets)

• Strong sense of cultural identity

Relationship Protective Factors

• Support from partners, friends and family

• Feeling connected to others

Community and Societal Protective Factors

• Feeling connected to community, and other social institutions

• Reduced access to lethal means of suicide among people at risk

• Cultural, religious or moral objections to suicide 9

Recognise 10

Anyone can experience suicidal thoughts. Most people with contributing factors do not attempt suicide, but warning signs should always be taken seriously, especially if multiple stresses are happening at once (e.g., loss, bullying, financial pressure, relationship issues). People often show signs through their words, behaviours or changes in functioning. You do not need to diagnose or interpret; the priority is noticing changes, checking in and seeking appropriate support.

I was that typical man, former soldier and police officer. Supervising friends and colleagues who looked up to me in their time of need, something I never did for myself, to reach out and talk. I had not planned to take my life by suicide, never thought about it, never wrote a suicide note. Having dropped my youngest kids off to school and our youngest to his grandparents, I got in my car and was overwhelmed with emotions I had never experienced ever before, guilt, shame and absolute despair

-Gary, Havering Lived Experience Advisory Group (LEAG) Member

Warning Signs

Key indicators of concern:

• History of self-harm or suicide attempt(s)

• Talking about suicide methods

• Feeling overwhelmed by problems outside their control

• Making final arrangements (e.g., giving away prized possession, writing letters, asking them not to be opened)

• Hints that “I won’t be around” or “I won’t cause you any more trouble”

• Unresolved feelings of guilt following the loss of an important person

• Looking for a way to end their lives

Behavioural warning signs

• Change in eating or sleeping habits

• Withdrawal from friends, family, interests

• Violent or rebellious behaviour

• Isolating themselves

• Increased use of alcohol or drugs

• Failing to take care of personal appearance or health

• Becoming cheerful after a time of depression

• Physical signs, for example weight loss or gain or muscular aches and pains

• Preoccupation with death

• Recklessness, self-destructiveness

• Poor performance at school, work

• Sleeping too much or too little

Verbal warning signs

• Talking about suicide

• Feeling hopeless

• No one cares

• Having nobody or nothing to love

• Having no reason to live

10 Understanding suicide and suicidal behaviours | NHS Fife

• Being a burden or bothering others

• Feeling trapped

• Hating their life

• Feeling like a failure

• Unbearable pain

• Wanting the pain or exhaustion to end

• Things would be better when they are gone/dead

• Problems will be over soon

• Lack of interest in the future

• Talking about physical symptoms (pain, headaches)

Mood-related warning signs

• Depression or anxiety

• Loss of interest in things

• Frequent irritability, aggression, rage

• Feelings of humiliation and/or shame

• Feelings of boredom, restlessness, self-hatred

• Outbursts of agitation and/or anger

• Unexplained crying

• Self-loathing or self-hatred

• Relief or sudden elation

• Extreme fatigue

Ask and listen

Talking to someone you’re worried about:

• Choose a private, calm moment where you won’t be interrupted.

• Use gentle, open statements: “I’ve noticed you seem down lately. How can I help?”

• Practice active and empathetic listening: listen with full attention. Be non-judgmental, calm and patient. Let them talk; reflect back what you hear.

• It’s important to speak plainly and directly, for example asking, “Have you ever thought about ending your life?”

• If they let you know they have been feeling suicidal, thank them for trusting you with this information. Avoid judgment, assumptions, or trying to fix things.

• Stay calm and focus on listening rather than giving advice or trying to change their feelings. Avoid saying things like “You’ll be fine” or “Think positively.”

• Avoid rushing to solutions or guilt-tripping, such as “think of your family”

• Ask if they have a plan: “Do you have a plan? When would you do it?”

There were days I didn’t want to keep going—but I’m so glad I stayed. I didn’t need someone to fix me. I just needed someone to listen.

-Sandeep, Havering Lived Experience Advisory Group (LEAG) Member

o “I want to keep you safe…can we make a plan together and get some help?”

o “Would you let me call someone who can help right now?”

Help

If you or someone else is in immediate danger

In an emergency, call 999 if you or someone you know experiences a life-threatening medical or mental health emergency. Stay with the person and continue to talk to them if you can.

If you or the person you are with can keep themselves safe for a short while but is still in need of urgent help:

• Dial 111 and speak to the NHS Mental Health Triage Service. It is free and open 24/7.

• For d/Deaf people or people with hearing loss, use your textphone and call 18001 111. If you use British Sign Language (BSL), you can also use the NHS 111 BSL interpreter service.

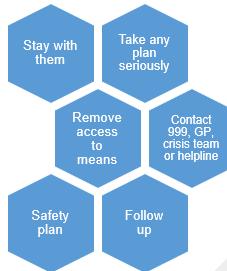

Immediate actions, if you or someone you know is thinking about suicide

1. Stay with them (or make sure they’re not alone) if there is an immediate risk.

2. Take any plan seriously. If they have a detailed plan and intent, call emergency services now.

3. Remove or limit access to means (medication, sharp objects, etc.) if it’s safe to do so. Ask a trusted person or professional to help.

4. Help them get professional support: encourage contacting their GP, mental health crisis team, local emergency department or a crisis line. Offer to contact them together or go with them.

5. Make or use their existing safety plan (download a template here or download the Stay Alive app for a ready-made digital safety plan) and agree on immediate steps and contacts.

6. Follow up afterwards. Check in regularly; simple contact reduces isolation and risk. Try to establish at least one other trusted individual to share in this follow up, so it is not solely reliant on one person to be available.

7. If they refuse help but are at immediate risk, call emergency services. You can do so even if the person objects. An immediate threat to a person’s safety can override confidentiality.

Safety plans

A safety plan is a simple, practical guide that helps someone stay safe during moments of crisis. It can also be a way for you and the person you’re supporting to plan how to communicate and check in with each other going forward. The most successful safety plans are made with the person, not for the person.

A good safety plan includes warning signs, coping strategies, supportive people, crisis contacts and steps to stay safe. Ask: “Do you have a safety plan?” “Would you like help putting it into action?”

Please see Havering’s Safety Plan tab for more information, including a downloadable template.

Or Download the Stay Alive App that includes a safety plan with customisable reasons for living, a LifeBox where you can store photos and memories that are important to you, strategies for staying safe and tips on how to stay grounded when you're feeling overwhelmed, guided-breathing exercises and an interactive Wellness Plan.

Local and national support

• Hub of Hope Service Directory for Havering

• See Local and National Support for

o 24/7 Suicide and mental health support

o Local mental health support

o Financial support

o Bereavement support, including suicide bereavement

o LGBTQIA+ support

o Alcohol, drugs and gambling support

o Domestic abuse support

o Support for carers, veterans and neurodivergent individuals

• See Leaflets and Practical Resources for:

o Anyone experiencing suicidal thoughts

o Anyone supporting someone experiencing suicidal thoughts

o Anyone who has witnessed a suicide

o Anyone experiencing suicide bereavement

o Anyone experiencing bereavement

o Adults engaging in self-harm

o Children and young people engaging in self-harm

o Parents of children engaging in self-harm

o Education staff of pupils engaging in self-harm

Accept your feelings and please reach out, you are so much more important than the destructive and negative thoughts that often blind us in our darkest hours. Help is out there, you are not alone.

-Gary, Havering Lived Experience Advisory Group (LEAG) Member

o Support and wellbeing resources for people from racially minoritised communities

o Safety Plans

• See Training Opportunities training session across North East London, including in Havering.