Founded in 1988, the original Harvard Art Journal published five issues of undergraduate, graduate, and faculty work, with a twenty-fifth reunion edition published in 2018 spearheaded by Paula Hornbostel (AB ‘93). This year, the journal returns adapted, expanded, and refashioned, beginning again with Volume I. The publication now focuses on undergraduate work, including contributions in the visual arts as well as art history

As such, the theme of this issue is “Looking Back; Looking Forward:” We look to the history of this journal as we revive and revise it for the future, and we seek to elevate art historical voices of the future by publishing quality undergraduate work In addition, this issue includes a conversation with Professor Felipe Pereda about the history and future of Harvard’s Department of History of Art and Architecture ahead of its 150th anniversary. The cover image a stylized elevation of the Harvard Art Museums courtyard was selected to represent the past, present, and future of art at Harvard in the original 1927 Fogg Museum design with the twenty-first-century Renzo Piano Building Workshop’s forward-looking renovation and expansion

This issue contains student work on modern conservation practice based in original artist ideas, Christ and the body in a medical anthology manuscript, notions of subjectivity in a work by Monet, sacred symbolism in Armenian liturgical textiles, and five exceptional works of visual art

I would like to extend sincere thanks to Marcus Mayo, for serving as our staff advisor and an invaluable support at every step of the process; Tom Batchelder, for encouraging and advising this project since its inception; to Paula Hornbostel, for sharing wisdom from the first and second iterations of the journal; and to our faculty advisory committee and the Harvard Department of History of Art and Architecture, for making the revival of the Harvard Art Journal possible

On behalf of the 2024 team, thank you for reading this issue of the Harvard Undergraduate Art Journal

Marin Gray, Editor-in-Chief

Artist Piet Mondrian’s distinctive style and artistic vocabulary expand beyond the stark blocks of white and harsh black lines that mark his canvases His spiritual philosophy is reflected in the material painting itself, but also the frames he created to encase his work Mondrian’s approach to painting combined with his philosophical beliefs influenced the role of art in society under the Neoplasticism movement of the 1910s and 1920s. One such Neoplastic painting from 1922, “Composition with Blue, Black, Red and Yellow,” found a home in the Harvard Art Museums at the beginning of this century The framing and materiality of this painting in particular prompt questions regarding the importance of art presentation and how contemporary art conservators ought to preserve Mondrian’s original vision

The composition of this work is simultaneously visually contained and expansive: it consists of a large central white (non-colored) plane surrounded by rectangles of blue, red, and yellow of varying sizes Thick, glossy black lines harshly delineate the colored planes, but stop short of the canvas ’ s edge. The canvas is mounted to a wooden set-back strip frame that projects the canvas forward into space, a departure from the traditional diagonal bevel frame typically used for ‘fine art ’ It is a rare example of a completely unrestored Mondrian complete with cracking and discoloration in the central white plane and a buildup of residue coating the surface thus making it an ideal object of technical study for conservators and scholars Many other Mondrian paintings were treated with harsh chemicals and reframed in the 1960s and 1970s in the name of preservation, but this ultimately damaged the canvas surface and often involved removing the original frame I will examine the current literature on Mondrian’s use of the picture frame and how his use of framing aligns with his idea of art as a means of reinforcing moral values and moving society towards a utopia Examining the framing and materiality of “Composition with Blue, Black, Yellow, and Red” through the lens of Mondrian’s philosophy and theoretical writing reveals the importance of situating paintings in their ideological context when making conservation decisions and the danger of not doing so

Early in his career, Mondrian worked in the midst and aftermath of the First

which are contained within the harsh black lines (such as the blue rectangle) and some of which encroach on the lines (such as the yellow rectangle). This creates a sense of conflict and push and pull between the lines and the colored planes, which removes stillness from the composition and erases any static balance The lack of symmetry and repetition in the composition also contributes to this idea of dynamic equilibrium, as emphasized in Mondrian’s fifth principle of Neoplasticism

Another embodiment of his thinking in this painting is the fact that the black lines do not reach the edges of the canvas. The lines stop just short of the edges next to the red and blue rectangles, giving the impression that the red and blue colored

planes extend past the borders of the artwork This idea of an artwork extending past the borders of the canvas connects to Mondrian’s concept of art as a way to create social change past the canvas ’ s physical constraints

Mondrian sought the expansion of the painting past the borders of the canvas during this period of his career, made clear by the thick black lines that allow the blue and red colored planes to escape and spill over onto the sides. But the framing of this painting is also key to reinforcing his philosophy of expansion in art The set-back strip frame used for this painting allows the canvas to end on its own terms without the artificial borders of a traditional frame. It introduces and welcomes the painting into our physical world, making the painting more material and real Mondrian chased after the idea of giving his paintings

the most “real existence” possible because he wanted them to inflict social change on the real world The set-back frame also removes the shadow and artificial depth that light and traditional frames create The artificial threedimensionality of the painting in the traditional frame moves the painting even further from our existence and makes it part of an illusion world instead of our current reality To push back against this creation of an illusion world, Mondrian sought planarity in his work He achieved this through the set-back strip frame that thrusts the artwork forward into realness

Comparing “Composition with Blue, Black, Yellow, and Red” in the Harvard Art Museums to “Composition No. III” in the Phillips Collection in Washington D C illustrates the importance of framing in Mondrian’s mission of spiritual progress and ‘real’ art It also demonstrates the key role that curators and museums play in prolonging and honoring

Mondrian’s thinking The former painting is displayed to viewers in its original frame with no barriers between the painting and the onlooker. On the other hand, “Composition No III” is displayed with an additional pane of glass and a wooden box surrounding it (Fig 2) Though the Phillips Collection attempted to maintain the integrity of the work by displaying it in its original frame, they still disturbed Mondrian’s mission by encasing the painting behind a layer of glass and surrounding it with a wooden frame that comes out of the painting This layer of glass traps the composition in an artificially created boundary and does not let the planes of color extend out into the space around them It limits the ‘realness’ of the painting’s existence by relegating it to an illusion world of art that is protected and shut behind glass The Harvard Art Museums’ approach allows the Mondrian painting to extend into the viewer’s world and space by not implementing additional layers of protection The glass on top of “Composition No III” also disrupts the planarity and two-dimensionality of the work, with the shadow of the glass on the painting creating the artificial threedimensionality and depth that Mondrian was vehemently against Juxtaposing these paintings reveals the importance of display decisions and curation in ensuring that Mondrian's philosophy is carried on through his artwork past his death

experience, but also whether they are compatible with the artist’s original intention. In the case of Mondrian, it may initially appear that visual imperfections are incompatible with his framework demanding a limited color palette and geometrically simple compositions However, considering his Neoplastic idea of dynamic equilibrium and hatred of static art, conservators may view Mondrian’s original intentions differently. The purpose of the composition of this painting and many of his other works is to achieve dynamism and constant movement He did not want his works to stand still in time, which is why he crafted off-balance and asymmetrical compositions. Conserving the work and attempting to restore it to its original appearance would be an erasure of the life of the work and the movement happening in it Conservators trying to ‘fix’ the painting to restore it to a past

“Curation and display decisions are more complex than selecting the display case for an object.” [15]

Curation and display decisions are more complex than selecting the display case for an object Whether to conserve the Mondrian painting in the Harvard Art Museums similarly raises questions of preserving Mondrian’s original philosophy or prioritizing the viewer experience. “Composition with Blue, Black, Yellow, and Red” remains completely untouched by conservators, meaning it has aged with time since its creation This is visually evident through the areas of discoloration and many cracks weaving across the surface of the central white plane.In cases such as this painting, conservators must consider the impact that these clear imperfections have on the viewer's

iteration of what it looked like would betray Mondrian’s concept of dynamism While preserving artwork means treating it as a static object that has a ‘correct’ form, Mondrian’s philosophy and rules of Neoplasticism would not condone fixing or restoring his artwork This is precisely why the Mondrian painting in the Harvard Art Museums is unique: it is a true embodiment of his philosophy and intentions. Its original frame, form of display, and lack of conservation align with the principles and aesthetics of Neoplasticism

Using Mondrian’s philosophical writings and art theory as a lens through which to analyze the conservation and display decisions reveals the best way to honor Mondrian’s original intentions for his work

Art conservation is an ever-evolving field with a framework that is constantly changing on a case-by-case basis in this case, Mondrian’s theoretical writing can inform the conservation process and allow for the most holistic and informed decisions. More broadly, conservators ought to consider both the historical and philosophical context when deciding how or if to conserve a work These philosophical conditions have the power to fundamentally change how a work of art such as “Composition with Blue, Black, Yellow, and Red” is studied

Sachi is a sophomore in Winthrop House concentrating in the History of Art and Architecture She is especially interested in how art history can integrate with other disciplines, such as neuroscience and philosophy In her spare time, she enjoys photography and practicing yoga

“Mondrian Painting Is First for Busch-Reisinger,” Harvard Gazette, January 20, 2000, https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2000/01/mondrian-painting-is-firstfor-busch-reisinger/.

Ibid

TANG Ke-bing, “The Lack of the Frame and Transformations of the Concept of Art,” Sino-US English Teaching 12, no 7 (2015), https://doi.org/10.17265/1539-8072/2015.07.004.

Gregory Schufreider, “Iconoclastic Images,” The Yearbook of Comparative Literature 56, no 1 (2010): 24–63, https://doi org/10 1353/cgl 2010 0005

Ali Fallahzadeh and Geneviève Gamache, “Equilibrium and Rhythm in Piet Mondrian’s Neo-Plastic Compositions,” Cogent Arts & Humanities 5, no 1 (2018), https://doi org/10 1080/23311983 2018 1525858

Schufreider, “Iconoclastic

Schufreider, “Iconoclastic Images ”

Fallahzadeh and Gamache, “Equilibrium ”

Ke-bing, “The Lack of the Frame.”

Andre Masson et al , “Eleven Europeans in America,” The Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art 13, no 4/5 (1946): 2, https://doi org/10 2307/4058114

The concept of the body held great importance in medieval religious culture. The first and most important of all bodies was the one belonging to God when the Word became flesh In the tradition of the imago dei, all human bodies point first toward Adam and Eve, and then to the Creator Himself. In the New Testament, the mystical body of Christ further symbolizes the Eucharist itself, which by extension encapsulates the entire Catholic Church

In similar fashion, medical illustration

historically has centered around the topic of the human body These images of the human body, however, did not explicitly encourage religious or moral messages Rather, religious and moral themes could be superimposed onto the scientific information already displayed in the images. There did not exist an absolute mapping from the illustrated human body in medicine to the religious practices of the time For example, images of skeletons could symbolize memento mori, and the standard male and female bodies could be seen as those of Adam and Eve. In broader medieval culture, the topic of the body was viewed as a bounded system or a construction like society Reading and understanding the human body, in fact, consisted of multiple methods and frameworks beyond religious contexts, including viewing it as a textual grid or even as a microcosm of the macrocosm itself For example, when the cosmos emerged as the most all-encompassing body in later medieval culture, the human body linked anatomy to celestial entities planets in inner circles ruled internal organs while surgeons leveraged these diagrams and linkages practically to execute operations successfully The medieval human body could thus be viewed and represented through many facets; these views materialized as illustrations.

Yet medical practitioners themselves historically questioned the status and authority of medical images of the human body Aristotelian and Galenic ideals emphasized the importance of first-hand visual experience when it came to matters of anatomy images could not be trusted as truthful substitutes for direct sensory impressions On the other hand, fourteenth-century physician Guido da Vigevano defended images in his teachings and practice, claiming that images could still enhance knowledge of anatomy. The reader, he claimed, would have a clearer understanding of organs through the viewing of surgical images Overall, the argument against the use of medical images in practice centered on the claim

that flat images could not capture threedimensional objects and spaces

Nevertheless, some scholars like Charles Etienne argued that images served better than verbal descriptions Thus, the overall usefulness in medical practice continued to be widely disputed, as they remained an integral but also a controversial component of medical practice and culture

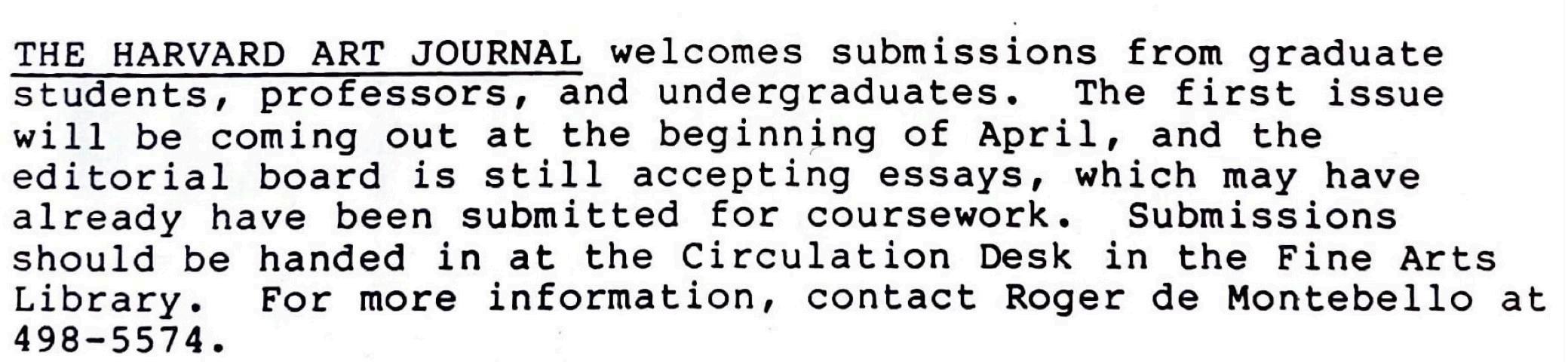

Sloane MS 1977, a medical anthology manuscript in the British Library created around 1300, follows the visual language found in other medieval medical documents by depicting numerous medical images addressing surgical procedures like cranial operations. The longest text in this anthology is a French translation of the Lombard surgeon Roger Frugard of Salerno’s Chirurgia, written in the late twelfth century Surprisingly, these forty-six folios of manuscript dedicated to surgery deviate from their expected illustrations through the inclusion of forty-eight images portraying Christ’s life cycle As a result, Sloane MS 1977 exists as an exceptional, but also curious, pairing of medieval and medical imagery and narration How can we understand this manuscript’s unique juxtaposition of medicinal practice and the life of Jesus Christ? Though connections from folio to folio between the life of Christ and the surgeon ’ s teachings do not materialize when looking closely at folios or specific scenes, the leitmotifs of these two registers portray the complementary nature of Christ as patient and doctor. In this paper, I aim to detail these parallel roles of Christ in Sloane MS 1977 and briefly explore their implications in broader medieval culture

In Sloane MS 1977, each of the pages from f.2r to f.9v follows the same broad organizational structure: a three-by-three grid of vertically oriented rectangles creates a framed rectangular space centered on the page Each of the nine sub-rectangles or cells, divided and surrounded by architectural columns or bars, depicts an individual image or scene The images on each folio are painted with

an alternating scheme of red and blue, with both the outside architectural frames alternating adjacently and the individual cells alternating in a checkerboard pattern.

This checkerboard organization of images is particularly reminiscent of the thirteenthcentury French manuscript tradition Found in Gothic manuscript illumination, the pattern was a decorative element often used to create visually intricate designs. Possible symbolic functions include representing opposing forces and states, such as the spiritual and material worlds Ornate pointed arches painted in orange and gold, coupled with alternating gold and patterned blue backgrounds, establish the architecture of stained-glass windows These windows frame each rectangle on the upper register to invite the viewer into a fictitious space of religious contemplation

And indeed, the scenes portrayed within the windows reveal Christ’s life Yet the life of Christ is not the only narrative unraveling on the page; illustrations of surgical operations lie in the two rows beneath

Folio f.2r (Fig. 1) identifies the beginning of the life cycle of Christ, presenting scenes of

pregnancies. The last scene in the top row of the folio finally shows the birth of Christ, as Mary can be seen resting while a baby Jesus is identified through his halo

elements. In all these medical scenes, a surgeon stands on the left, while a patient adopts different positions: standing, kneeling, or sitting cross-legged. The surgeon, clothed in a long sleeveless outer robe and coif, wields numerous tools while operating on a patient in a cranial surgery. The setting of a treatment facility is lightly suggested through the shelves in the middleleft cell on the page The emphasis on tools is part and parcel of medieval medical illustration: as an example, the bottom left image on the next page, f 2v (Fig 3), depicts the medication of a fractured cranium. Following procedures found in texts of the time, the surgeon here applies a healing ointment, called apostolicon chirurgicon, to the patient’s cranial wound Other medical images found in the bottom two registers of the remaining folios depict manual operations like the setting of fractures, treatment of tumors, and other forms of wound surgery Through an examination of the initial images found on the first couple of illustrated folios in the manuscript, it becomes clear that the numerous scenes belonging to two separate classes of images the religious and the medicinal exemplify their

In contrast, the six images below are formatted relatively plainly with respect to their backgrounds and lack of architectural the Annunciation, Visitation, and Nativity on the upper register of the rectangle In the top left scene, the angel Gabriel, easily identified through orange halo and wings, unravels the Word of God to tell the Virgin Mary that she would be the mother of the savior Christ The iconography of this scene is in line with preceding manuscript traditions While the pointed arches framing the scene differ from the use of round arches found in other manuscript depictions of the Annunciation, such as the thirteenthcentury Psalter of Ham of Fecamp, the image still follows standard readings of a theatrical revealing of the beginning Christ’s life Furthermore, Mary can be seen reading the Book of Isaiah’s prophecy decreeing that the Virgin will conceive of the savior This visual motif, present in the Psalter of Ham of Fecamp and the Aix-en-Provence, Bibliothèque municipal, MS 15 (Fig. 2), became an important symbol in visualizing Mary’s role in the Annunciation The subsequent scene on the top register of folio f 2r portrays a pregnant Mary, recognizable through her red, white, and green garb, rejoicing with a pregnant Elizabeth. The vegetal motifs allude to prosperity and fertility, echoing the two women ’ s blessed

respective visual and historical traditions. As demonstrated by those found on folio f 2r and f 2v, the religious scenes locate themselves in traditions of other French medieval manuscripts and speak to this manuscript’s quality, while the medical illustrations accurately detail surgical operations practiced in the time.

With the nature and quality of illustrations in the manuscript established, the next question entails understanding why these two traditions of the Christ cycle and surgical operations were placed together. A natural reading of the relationship between these two narratives declares that they are somehow paired folio by folio and even scene by scene, given the grid-like structure of the images This view would neatly provide commentary on the relationship between Christ and medicine. Two prominent examples of such a literal and tightly connected dynamic between Christ’s life and surgical operations can be found in folios f 5r and f 7r (Fig 4) On the top right scene in folio f 5r, familiar ornate pointed arches reveal Judas’ suicide in front of a shimmering golden background.

A tall tree to the right of the scene, with two groupings of leaves paired with the arches, buckles under the weight of Judas’ body The rope wraps from the top of the tree and around his neck as he grabs on with his left hand The wrinkling of the eyebrows and protruding tongue depict Judas’ demise as his feet hang above the ground. Looking directly under this scene, the reader finds a patient visiting a doctor with a dislocated neck, illustrating a clear tie between the adjacent cells Another example can be found on the top right image of folio f.7r, where Christ is pictured crucified on the upper register of scenes Christ, pinned to the cross with blood spurting from the nails in his body, is stabbed with a spear by a soldier below In the surgical images below, namely the middle one, the patient can be seen requesting the removal of missile weapons from his torso.

While these two examples closely link the medicine and religion portrayed in adjacent cells, there are plenty of counterexamples in the manuscript where the images of Christ have no connection to the medical

explicitly point toward or illustrate Christ as surgeon and patient, the juxtaposition of Christological and surgical scenes in the grids on all sixteen folios generates a significant contextual backdrop to see Christ in these parallel roles

The Sloane MS implicitly portrays Christ as a surgeon or doctor As noted by Valls, the preface of the “Chirurgia” states:

Cil souverains mires volt a soi retenir la cure de la partie pardurable, c ’est de l'ame, et nos deguerpi et nos laissa la cure de la chetiveté terrienne, c ’est du cors, a curer, sicomme sont des plaies et des autres enfermetés

the first place point toward Christ as a divine surgeon

[9]

Here, God is viewed as a physician who cares for the soul while man cares for the body. While the preface clearly separates the spiritual from the material, there remains a parallel drawn between Christ and the surgeon in their roles as healers Christ himself also does not strictly adhere to this boundary. As God in human flesh, Christ is shown to have performed many miracles directly curing people’s physical illnesses in addition to spiritual cures For example, when a leper approached Jesus and pleaded to be made clean, Jesus cleansed him of his leprosy with the touch of a hand and the words “Be clean!” This tactile nature of Christ’s healing can be compared to that of a surgeon, who works primarily on exterior wounds with handheld tools

Still, Christ is no human doctor, as he succeeds in curing conditions like blindness from birth that would be incurable by medical methods of the past and even methods today The surgeon in the Sloane manuscript performs medical feats requiring a great deal of skill Within this framework, the hierarchical grid of the manuscript images is explained as physical representations of this separation between divine healing and human healing, while their alignment and placement together in [8]

The issues raised by the Sloane MS regarding the relationship between physical and spiritual healing enter a comprehensive discourse around the concept of Christus medicus: Christ the Divine Physician. Preachers and medical practitioners called upon this model in their works and imagery to invoke Christ’s mission of preaching and healing The Christian tradition espousing this model saw spiritual care of the soul as a process interconnected with the body in terms of health, illness, sin, and absolution One of the main voices concerned with the rhetoric of Christus medicus, Augustine, constructed a logic-based approach to the health of the body that extended to spiritual health. He believed that the body and soul functioned together not only for the individual but also for collectives of individuals like the Church He also maintained that the Church functioned like a body it could be in perfect health and function as intended, or break down under the corruption of sin. Augustine’s views connecting the Church and individual illness and suffering reveal the complexity surrounding the dynamics between physical and spiritual illness as well as the extension from a single body to a community such as the Church. The relationship latent within the illustrations of the Sloane MS connects the narratives of Christ’s life and surgery in “Chirurgia” to the much broader topic of Christus medicus The Sloane manuscript exemplifies this whole cleansing of the individual that Jesus can perform. In the tradition of Christus medicus, the reader learns about healing patients from a variety of bodily wounds on the bottom rows while simultaneously tending to their spiritual health by reading about the life of Christ

[10]

As suggested by the topos of Christus medicus, one also cannot ignore the commitment to pedagogy in Christ’s life when comparing Christ to healer Christ not only performed divine miracles to heal others but also took on the role of teacher in many forms. This emphasis on teaching

Figure 5: Folio f 7v in Sloane MS 1977, late thirteenth century to early fourteenth century

on medical education In Sermones medicinales of the fifteenth century, Niccolo Falcucci explained the pedagogical responsibility of physicians: the exemplar physician became a doctus and expertus together, gaining both theoretical and doctrinal competence In medicine and especially surgery, the ability to know and do are clearly integrated closely and valued The medical illustrations in the Sloane MS detail various procedures but remain limited in their educational scope as discussed earlier, as they were not meant to introduce the reader to surgery and were instead intended for more practiced surgeons However, the images themselves reveal that the surgeon takes on an instructional role while the patient learns. In nearly all medical scenes, the surgeon engages in animated conversation with the patient as seen from various hand gestures Although typical images of masters or teachers involve the master carrying text of some sort, the receptivity of learning displayed by the patient is expressed through his or her hand gestures For example, the middle section of folio f 7v (Fig 5) shows the surgeon pointing his finger or gesturing with an open palm, while the patient raises an unoccupied hand while looking directly at the surgeon, sometimes even turning their head Despite the poor physical condition of the patient, this communication remains apparent in the images, conveying the importance of teaching in these medical

scenes These themes in medical education overlap significantly with the broader educational views on the importance of moral traits like

docility, filial affection, and respect for the teacher

One goal of medical education states that the goal of the master is to reproduce himself in the pupil Just as the doctor teaches the pupil to master medicine, Christ fulfills this role with his disciples. In Luke 10, he sends seventy-two disciples to enter a town to heal the sick and to say “The kingdom of God is at hand for you, ” thereby establishing his role as mentor and teacher The disciples fulfill their role as discipuli in the medical sense, ingesting Christ’s teachings and then assuming the role of doctors as they cure physical sickness and spread the gospel

The coexistence of the Christ cycle and surgical operations does not solely point toward Christ as surgeon, it also evokes Christ himself as patient Although the surgeon is a key figure throughout the illustrated folios, the patient is the other constant character present in the medical procedures Typically, in medieval surgery scenes, “patients are shown either held or tied down; and the accompanying texts sometimes recommended that the patient ‘be held in chains’ ” In contrast, the patients in the Sloane MS can be seen enduring seemingly agonizing illnesses and treatments without being held down or restrained in any way. Rather, the patient freely stands, kneels, or sits while showing the surgeon their cause for treatment with an expression devoid of pain This notable deviation in the medical illustrations of “Chirurgia” connects the patient to Christ Christ is seen without an expression of pain or suffering amidst scenes of flagellation (f 6r, Fig 6) and crucifixion (f 7r) While the wounds covering his body and blood gushing out illustrate the severity of the physical torment he is subjected to, his emotional state seems unaffected In this way, Christ and the patient converge in these images.

As a patient, Christ provides a model for how to endure suffering and pain Not only is Christ unwavering and stoic in reactions to pain, but he also willingly experiences pain by taking on human flesh for the sake of humanity’s salvation Christ’s suffering becomes integral to the culture of pain and suffering. One manifestation of this

One manifestation of this phenomenon is the emergence of devotional image-types like the Man of Sorrows, which shows Christ’s bodily suffering. The Man of Sorrows depicts Christ in a state of suffering and sorrow from his life, which includes Christ wearing a crown of thorns, with wounds on his hands and feet, or with his head bowed In the Book of Hours’ Man of Sorrows (Fig 7), Christ points toward his wound as blood runs down his side, acutely emphasizing his bodily experience of suffering This iconography resonates with viewers as a reminder of Christ’s sacrifice and love. Another crucial component of this culture of suffering is the stigmata, a replication of the sacred wounds of Christ on a believer. These wounds emulate the suffering of Christ for the salvation of humanity as an imitatio Christi Scholarship has historically identified examples of stigmatization, with some prominent examples including Saint Francis Saint Francis was the emblematic saint of late medieval Christianity who attributed spiritual significance to his experience of illness:

“The experience of suffering from illness –an experience Saint Francis really knew –was not seen by him as divine punishment for personal sins (he refers nowhere to such supporting Old Testament quotes), but rather as a spiritual exercise for participating in the suffering of Christ.”

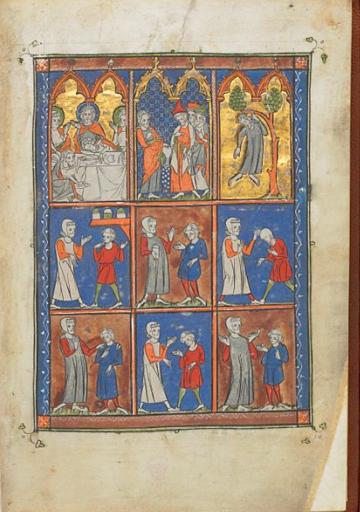

This concept of imitatio Christi emerges as an important motif in the culture of pain even in later medieval art and beyond, as exemplified in Piero della Francesca’s “The Flagellation” (Fig 8) This painting depicts the flagellation of Christ in the background while a trio of figures of quattrocento Italy remain removed from the situation Two of the historical figures are powerful Renaissance men recently struck by the loss of their sons. An angelic son brings the two together These men parallel the flagellation due to shared loss and pain: Jesus’ expressionless face as he accepts God’s will provides a model for the two in

handling grief Christ’s endurance of suffering as suggested in the Sloane MS continues this rich tradition. Because Christ’s suffering resulted in the ultimate healing for humanity, the pain of Christ as patient is inextricably also tied with healing Patients must bear suffering to be healed through salvation in a similar manner to how Christ suffered in a human body to save mankind itself. This healing aspect of Christ’s suffering as a patient transforms this experience into more than just the reciprocal of Christ as surgeon: the roles of patient and surgeon are not solely

The Sloane MS 1977 juxtaposes images depicting Christ’s life with images of surgical procedures Though these illustrations follow visual traditions found in the corpus of thirteenth-century manuscript illumination, the pairing of the two cycles is puzzling Though it is difficult to consistently match moments from the life of Christ to medical operations, one explanation for the combination of these two image groups involves arguments of practicality and luxury. Including wellknown and gold-adorned Christological images likely increased the status of the medical manuscript But this explanation does not seem satisfactory Abstracting away from connections between specific medical and religious scenes reveals a significant connection between the two parallel cycles The overlapping of these two cycles at the nexus of physical and spiritual healing and suffering culminates in Christ as surgeon and patient The concept of Christ in these two roles is contained in the manuscript images, thrusting the Sloane MS into existing discourse regarding the intersection of medieval medicine and religion

In this interpretation of the images, the versatile scenes of the Sloane MS gain further instructional value. As a resource for surgeons, the images of Christ’s life serve as more than a symbol of luxury and status: the surgeon must look toward the example set by the divine physician Christ He has the indispensable duty of healing the patient of physical illnesses and must fulfill his role as teacher for other students of medicine But Christ as patient is also an exemplar for the surgeon in the endurance of suffering for sacrifice and salvation The Sloane MS curates a unique experience contemplating pain, suffering, and healing both spiritually and materially. Each folio perhaps serves as a reminder that physical health and spiritual devotion come aligned as a pair

Erik is an senior in Adams House studying History of Art & Architecture and Statistics Growing up in Lexington, Massachusetts, he has always enjoyed creating and viewing visual art

“Michael Camille, “The image and the self: unwriting late medieval bodies” in Framing Medieval Bodies, ed. Sarah Kay and Miri Rubin, United Kingdom: Manchester University Press, 1996, 74.

Ibid , 64

Pantin, Isabelle, "Analogy and Difference " In Observing the World through Images, (Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2014) doi: https://doi org/10 1163/9789004263857 003

Alison Stones, “Gothic Manuscripts: 1260-1320 ” (London, Harvey Miller /Turnhout, Brepols, 2013, 2 vols , A Survey of Manuscripts Illuminated in France)

Loren Carey MacKinney, “Medical Illustrations in Medieval Manuscripts.” London, 1965, 68.

Helen Elizabeth Valls, “Studies on Roger Frugardi's ‘Chirurgia.’” University of Toronto (Canada), 1996, 15

Whittington, Karl “Picturing Christ as Surgeon and Patient in British Library MS Sloane 1977 ” Mediaevalia 35 (2014), 86 doi:10 1353/mdi 2014 0009

Sloane MS 1977, “A medical anthology including Roger Frugardi's ’Chirurgia ’” F 10r

Matthew 8:1–4; Mark 1:40–45; Luke 5:12–16

Patrick Outhwaite, “Christus Medicus and Religious Controversy in Late-Medieval Europe: Dissidence, Authority, and Regulation.” McGill University (Canada), 2021, 3.

Chiara Crisciani, “Teachers and learners in scholastic medicine: some images and metaphors ” (1997 - 1999) In History of Universities vol 15 (1997/99), 75

Luke 10:9

Loren Carey MacKinney, Medical Illustrations in Medieval Manuscripts London, 1965, 63

Camile, “The image,” 74.

Gábor Klaniczay, “Illness, self-inflicted body pain and supernatural stigmata: three ways of identification with the suffering body of Christ.” 2015. In Infirmity in Antiquity and the Middle Ages, 126

David B Morris, “The Culture of Pain ” United States: University of California Press, 1991, 272 Valls, “Studies,” 136

It’s a snowy scene in late winter. A road, barren, paves its way through a dense forest Two weary travelers trudge through the spring ice and slush their faded clothes blend in with the blurry blue and gray surroundings. A triangular mound, nestled in the background of the work, symbolizes the end of the road the destination: the Farm Saint-Siméon Yet the travelers still have a long way to go Long, pointed trees reach up to the sky on the right of the scene; rounded, old trees form bulbous shadows on the left. The only signs of human contact are the wooden rails that line the sides of the road, the plank of wood in the right bank of snow,

and the farm in the distance Monet’s painting, “Road Toward the Farm SaintSiméon, Honfleur” (Fig 1), is a work on the brink It represents not only rapidly changing artistic styles, norms, and traditions, but also transcendentalist, romantic, and metaphoric ideologies. Vague and applicable to almost any viewer’s life, Monet’s painting is a commentary on human existence, on humankind’s relationship with nature, and a metaphor for a life’s journey. In the following investigation, I will situate Monet within the evolution of art and society in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, establish his relationship with rurality and urbanity, and study his peculiar use of a nonspecific, raw technique and vague figural depictions, such as those present in

susceptible to the deep and contemplative emotional experience that the work evokes Monet’s painting succeeds in what many try to achieve but ultimately fall short of: transporting the viewers into another world

While Monet spearheaded the Impressionist movement, winter scenes by Impressionist artists have been historically overlooked In his essay, “Effet de Neige: ‘Claude Monet and a few others , ’” Charles Moffet writes that, “Most collectors, curators, and dealers have always preferred paintings with blue skies, sun, gardens, and fields of flowers, but the snowscapes of the Impressionists especially those by Monet, Sisley, and Pissarro are among their greatest accomplishments,” continuing by saying that such scenes evoke “ a sense of peace, stillness, and quiet beauty that is unique in the history of modern art ” With the emergence of the Impressionists, viewers were encouraged to reconsider the subject hierarchy that, in many regards, dictated Western Europe’s classification of art, shifting the focus from a historical subject to emotion and light. “Road Toward the Farm Saint-Siméon, Honfleur” is, of course, a landscape, suggesting that Monet, in painting such a scene, discarded the norms that ruled his predecessors even in his most seemingly elementary study, he was challenging the notion of what art should be at the time So why, then, did Monet, when choosing to incorporate human and even animal subjects within

culture of contemporary France. Notably, the Industrial Revolution occurred in France in the first half of the nineteenth century, causing major developments in both the industrial economy and culture of France It was against this backdrop of French modernization that Monet decided to venture out into the Norman country to produce “Road Toward the Farm SaintSiméon, Honfleur” and other works It is possible that Monet sought refuge and natural beauty in the snow-covered countryside of Normandy, providing a physical escape from the growing pains of industrialization both for himself and for his paintings’ viewers

Comparing Monet’s “Road Toward the Farm Saint-Siméon, Honfleur” to another of his paintings, “The Gare Saint-Lazare: Arrival of a Train” (Fig. 2), painted ten years after “Road Toward the Farm Saint-Siméon” in 1877, it is clear that Monet was fascinated by both urban and rural scenes as lenses for the industrializing period in which he worked “The Gare Saint-Lazare: Arrival of a Train” depicts a train entering an industrial, large, and busy station. There is an essence of innovation, production, and progression, amplified

“So why, then, did Monet, when choosing to incorporate human — and even animal — subjects within his work, follow the strict style of obscure and shadow-esque imagery?”

his work, follow the strict style of obscure and shadow-esque imagery?

To answer this question, it is important to note the changing social and political

by the light blues and purples of the work and the apparent movement provided by the incoming train, people, and fumes a stark contrast to the “Road Toward the Farm SaintSiméon, Honfleur ” However, even with the swirling smoke and machines present in “The Gare Saint-Lazare,” Monet’s bravura technique and vagueness are maintained; the human figures depicted retain their lack of specificity.

Like in the “Road Toward the Farm,”

Monet’s emphasis is placed on the natural phenomena, not the people The orbs of smoke exuded from the incoming train are more defined than anything else in the painting Why would Monet, when portraying human progress and development, continue to decenter the faces of the human depictions? He is, like in his earlier paintings, transporting the viewers into the world of his painting through the seeming emptiness of each human depicted; yet there is something different about this transportation.

In the “Road Toward the Farm SaintSiméon, Honfleur,” Monet conveys an overwhelming sense of open-endedness and, most importantly, vagueness not just in the figural depictions but also in the setting. In “The Gare Saint-Lazare: Arrival of a Train,” on the other hand, viewers can almost hear the loud whistle and screeching of the incoming trains, the rancid smell of the burning coal from the engine, and the constant, yet prominent, chatter of the people in the background This painting depicts a recognizable place: the Gare Saint-Lazare station in Paris. Ultimately, while Monet is once again using his artistic capabilities to transport the viewers, he now uses this technique of an undefined nature to achieve a very different goal– to evoke an emotional and specifically artistdetermined response. “The Gare SaintLazare: Arrival of a Train,” unlike the “Road Toward the Farm Saint-Siméon, Honfleur,” brings viewers to a specific place, rather than letting the viewers choose their destination instead

“Road Toward the Farm Saint-Siméon, Honfleur” is a work that thus focuses on a surprising subject: a road itself The two human figures, which are located in the left middle ground of the work, do not take a dominating position within the work’s composition. The painting features raw brushstrokes that aid in conveying the overarching emotion and atmosphere so important to the artist’s work Furthermore, Monet is able to convey a sense of rawness and vitality qualities that bring the work

to life. This technique is quite important for this painting, in particular, as its subject is a snowy road within a hushed atmosphere Even the natural beauty of the scene is, in some ways, lacking, as the scene depicts winter a time when natural life is in a state of nonexistence. Monet’s deliberately exposed brushstrokes further imbue the work with a sense of motion amidst the landscape’s subdued stillness

As mentioned earlier, this work is undistinguished in its composition meaning that it does not have a recognizable or defining characteristic Regarding the painting itself, many people who encounter the “Road Toward the Farm Saint-Siméon, Honfleur” in the Harvard Art Museums will not be able to recognize the scene ’ s particular location without the aid of the title. In this respect, it is possible that viewers of the painting at the time of its creation in the nineteenth century likewise would not have connected the work to a specific recognizable site, but rather would have associated its generic features with a recognizable feeling personal to their experience of such scenes The snowy road and the undistinguished building in the background do not mark a universally recognizable place, like Paris or Marseilles Yet, this lack of specificity gives the painting an important ability, allowing

spectators to appreciate a remarkably individual viewing experience It is the painting’s individual and personal qualities stemming from its lack of specificity that allow it to provide not just one specific image, but infinitely many, as it relies on the viewers to provide their interpretation, understanding, and feeling of the work. Ultimately, it is Monet’s nondescript figural depictions in the work that allow spectators to live in the scene vicariously and experience this natural and peaceful world

Additionally, the road, in its prominence, serves as a metaphor for life’s journey Travelers follow the path though neither they nor the viewer know not what they may encounter along the way, nor will they understand the full extent of the journey until they arrive at the destination. Monet portrays how life is predetermined, and all one has to do is march onward, forward, always “Road Toward the Farm SaintSiméon,” in all its simplicity, is an incredibly evocative, beautiful, and emotional painting The nondescript nature of the

ThomasFerro‘26

ThomasisarisingjuniorinWinthropHousepursuing ajointconcentrationinEnglishandClassics,witha particularemphasisonseventeenth-centuryEnglish literatureandGreco-Romanartandarchaeology ThomasisaCultureEditorforTheHarvardCrimson andco-leadsaweeklyseminarteachingnewwriters howtowriteforTheHarvardCrimson'sArtsBoard

figural depictions and scene itself allows viewers to be transported into another world: not a world of the artist’s choosing, but a world that belongs to the individual In this sense, the painting differs from others, like “The Gare Saint-Lazare: Arrival of a Train,” as it serves as an open template that rids the viewers of any comfort of certainty, definition, and tradition its subtleties only make Monet’s message stronger In the “Road Toward the Farm Saint-Siméon, Honfleur,” blue sky peeks out behind the large gray, overcast clouds. Blades of grass emerge from under the snow. There is a sense of hope and of light at the end of the tunnel among the undeniable heaviness of winter For the travelers, that light could be the Farm Saint-Siméon For us, only time will tell

John Hollander, “Effet de Neige: Claude Monet La Route de la Ferme St-Siméon, Honfleur, about 1867,” Grand Street, Spring, 4, no 3 (Spring 1985): 35, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25006726.

Sylvia Patin, “Argenteuil, The High Noon of Impressionism,” in Monet: The Ultimate Impressionist, trans Anthony Roberts (New York: Discoveries: Harry N Abrams, Inc , Publishers, 1993), 38

Charles Moffet, “Effet de Neige: ‘Claude Monet and a few others ’ , ” in Impressionists in Winter (London: Philip Wilson Publishers Limited, 1998), 14

Ibid Ibid., 15.

Arthur Louis Dunham, “Conclusion,” in The industrial revolution in France, 1815-1848, (New York: Exposition Press, 1955), 424 1 3 4 5 2

The Armenian Orthodox Church, also known as the Armenian Apostolic Church, stands as one of the oldest Christian denominations, tracing its roots back to the apostolic age Founded by two of Jesus' apostles, Thaddaeus and Bartholomew, it has maintained a continuous presence since the first century AD. Officially adopting Christianity as the state religion in 301 AD under the reign of King Tiridates III, Armenia became the first nation to do so, setting a precedent for the integration of Christian faith into a nation's identity. The Church has since been a cornerstone of Armenian cultural identity, surviving periods of persecution and flourishing during times of independence and thereby embedding itself deeply into the historical narrative of the Armenian people

Textile art in liturgical tradition is not merely a medium of aesthetic expression but a vessel of storytelling and doctrinal teaching The Armenian Orthodox Church, in particular, has a venerable tradition of incorporating intricate textile art into its worship, with garments and altar cloths serving as didactic tools as well as sacred ornaments The luxurious fabrics, threads, and pearls used in these textiles are more than symbols of opulence; they are part of a visual language that communicates theological truths and biblical narratives. Through the richness of their textures and the depth of their iconography, these textiles connect the congregation with the divine, weaving a tapestry of faith that is both tangible and transcendent

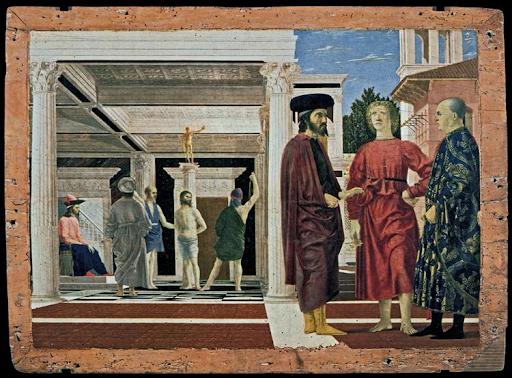

This paper investigates the artistry and symbolism of a remarkable set of liturgical garments from the Armenian Orthodox tradition: a mitre and amice, with an accompanying pair of infulae (Fig 1), from the mid to late eighteenth century, located in the Holy Mother of God Church. These matching vestments (hereafter referred to collectively as “the set”), replete with embroidered narratives and symbols, serves as a testament to the spiritual and artistic legacy of the Armenian Church The paper will also explore the ways in which these garments articulate the intricate relationship between Christ and the Trinity it will echo the connections between the Old and New Testaments and showcase the superb craftsmanship and interpretive skill of the artist The examination of this set will not only offer insights into the liturgical practices of the Armenian Orthodox Church but will also reveal the profound layers of meaning woven into the fabric of these sacred items

The historical period of the mid to late eighteenth century was a time of artistic flourishing and religious affirmation for the Armenian community, particularly within the Ottoman Empire, where a significant Armenian population resided

This era, while fraught with the complexities of living under Ottoman rule, allowed for the expression of Armenian cultural and religious identity through the arts

The conceptualization of Armenian communities as skilled tradesmen and merchants was solidified through various segments of European visual culture; Johannes Lingelbach’s 1656 painting, “Gezicht op de Dam” (Fig 2), showcases a group of Armenian merchants in the lower right corner, easily identifiable through their clothing and headwear. Since the sixteenth century and well into the eighteenth [5]

and nineteenth centuries, Armenian merchants traveled to Amsterdam to sell valuable goods like pearls and jewels this is what is captured so intently in Lingelbach’s depiction of Amsterdam as an international trading hub The presence of these Armenian communities in art coming out of the Dutch Golden Age serves as a preliminary testament to the longstanding familiarity with textiles, pearls, fabrics, and jewels that Armenian communities successfully maintained for centuries they were known internationally for their particular way of dress and unique cultural practices Folio 35 (Fig 3) in seventeenthcentury German engraver Christoph Weigel’s “Orientalische Kostüme, 100 Bl Aus Weigel’s Verlag” is visual supporting testimony for this idea the engraving showcases an explicitly Armenian priest in vestments noted for their Christological adornment

Ecclesiastical textiles in particular from this time are embodiments of Armenian cultural and religious expression The eighteenth-century liturgical set will serve as a case study through which the devotion, craftsmanship, and theological mastery of the Armenian religious community can be

better understood Crafted during a period when the Armenian Apostolic Church sought to preserve its traditions amidst external pressures, these garments ultimately represent a confluence of faith and resilience.

The creation of such garments was not simply an act of aesthetic labor but a profound manifestation of devotion In the liturgical context, these garments served functions that went beyond the ornamental. They were integral to the ceremonial vestments worn by the clergy during divine services,marking the sacredness of the occasion and the solemnity of the rituals performed The mitre, worn on the head of a bishop, symbolizes authority and the divine grace bestowed upon the clergy The amice (or vakas), a decorative collar or band, is a visual accent that frames the celebrant, often adorned with iconography central to the theological messages being conveyed during the service. Finally, the infulae long strips of adorned fabric typically complete the set, providing a visual harmony and thematic continuity with the rest of the vestments

[7]

[8]

The set resides in the Holy Mother of God

Church in Turkey, also known as Surp Asdvadzadzin Patriarchal Church The significance of these garments being housed across (and within) the Armenian Patriarchate in Istanbul cannot be overstated. The Patriarchate, being the spiritual center of the Armenian community in Istanbul, serves as a custodian of Armenian heritage Garments like the mitre set are treasured not only for their beauty and craftsmanship but also as part of the living history of the Armenian Church. Their preservation and proximity, along with the variety of similar objects treasured in nearby sacred spaces, signifies a continuous thread of tradition, linking the past to the present and carrying with them the stories and the prayers of generations.

[9]

The Patriarchate’s role in safeguarding such artifacts ensures that the artistic and spiritual legacy of the Armenian Orthodox Church is honored and remembered Furthermore, the presence of these garments in Istanbul, a city that has been a crossroads of civilizations and a melting pot of cultures for hundreds of years, reflects the historical interactions between the Armenians and their neighboring communities

The central theme of Christ in these garments is profoundly represented, with detailed embroidery showcasing His role as the Second Adam This title is rooted in Christian theology, wherein Adam, the first man in the Old Testament, is seen as having brought sin into the world, while Christ, by his sacrifice, redeems humanity and restores the relationship between God and man This theme is vividly illustrated through the depiction of Christ triumphant (Fig 4), resurrected, and holding a staff with a banner a symbol of His victory over death and His role in the new creation, just as Adam was pivotal in the old creation Mary's depiction above the snake holding an apple in its mouth (Fig 5) symbolizes her triumph over the original sin, correcting the error of Eve Just as Eve is considered the mother of all living in the Old Testament, Mary, in giving birth to Christ, ushers in new life for all through

salvation. Her portrayal above the serpent, a symbol of evil and sin, with the apple in its mouth, is a direct reference to the Genesis narrative and underscores her part in God's redemptive plan Mary's victory over the serpent symbolizes the undoing of Eve's temptation and fall, offering a path of redemption and hope. This is not just artistic preference it is a theology and doctrine embroidered into the physical identity of the vestments Similarly, the portrayal of Christ holding a staff with a banner represents His victory over death and His role as a shepherd to the faithful. These symbolic parallels are further elevated when one considers how the miniature woven portraits essentially mirror one another on opposite sides of the mitre surrounded by an identical curving border of pearls. The resurrection of Christ as the Second Adam and Mary as the Second Eve directly connects to the redemptive narrative of Christianity

The surrounding motifs are equally symbolic The vines of grapes and leaves, for instance, reference the Eucharist, with the rich wine-red color of the primary background fabric representing the blood of Christ, and the grains of wheat reminding viewers of the source of the bread of life His body

The depiction of the Trinity on the mitre is a masterful work of theological artistry as well The dove, representing the Holy Spirit, is positioned at the apex, with a radiating sunburst emanating from behind, a common symbol of divine glory and enlightenment. Below, the resurrected Christ is central, connecting directly to the Holy Spirit above The Father's presence, while not depicted in form, is symbolized by the triangular halo at the center of the radiating sunburst, a nod to the doctrine of the Trinity one God in three persons. This iconography is mirrored on the reverse panel with Mary, reinforcing the unity and equality of the Trinity, with the Holy Spirit's emblazoned sunburst and the triangular halo once again making an appearance

The iconography embroidered into the fabric of the set is richly imbued with biblical references, serving to reinforce and illuminate the liturgical and doctrinal messages of the Armenian Church These garments are narrative canvases, where each thread is a stroke in the portrayal of scriptural truths made physical. A reference to John 19:34 is particularly poignant in the previously mentioned imagery of the crucified Christ on the amice (Fig 7) The Gospel recounts, "Instead, one of the soldiers pierced Jesus' side with a spear, bringing a sudden flow of blood and water." This moment, captured in the fine details of the embroidery, is a powerful expression of the belief in Christ's sacrifice as a source of spiritual cleansing and redemption The precision with which the blood is rendered, flowing from Christ's side with each stitch reflecting a drop, serves as a visual exegesis reminding the beholder of the moment when the Church, symbolized by the blood and water, was born from the side of Christ It visually communicates the doctrine of atonement that Christ, through His death and resurrection, has removed the sins of humanity. The presence of this imagery on the vestments worn during the Divine Liturgy serves to deepen the worship experience, connecting the liturgical present with the salvific events of the past

Through the artistic representation of these deep theological themes, the garments weave a narrative that connects the creation and the fall of man with the redemption and resurrection offered by Christ, highlighting the fulfillment of Old Testament prophecies and figures in the New Testament's revelations. The set thus becomes a silent yet eloquent preacher, articulating through threads and pearls the profound mysteries of the Christian faith The theological symbolism in these Armenian liturgical garments is a testament to the deep devotion and rich theological understanding of the Armenian Orthodox Church Every stitch carries meaning, and every motif tells a part of the grand story of Christianity, from creation and fall to redemption and glory These garments are not only worn for their beauty

but are also donned as a declaration of faith, a catechism in silk and gold that educates and inspires the faithful through the power of sacred art

“Every stitch carries meaning, and every motif tells a part of the grand story of Christianity, from creation and fall to redemption and glory.”

These garments, steeped in biblical references, function sincerely as didactic tools The visual elements are not only decorative; they are laden with doctrinal significance They are designed to edify, to inspire reflection, and to educate the faithful about the foundational events of their faith The iconography serves as a bridge between the written Word of God and the visual representation of that Word, allowing the congregation to " see " the biblical stories unfold before them in the liturgical setting. Moreover, the specific selection of these passages for inclusion in the garments' design is deliberate They were chosen because they encapsulate key aspects of Christian doctrine: sacrifice, redemption, and the recognition of Christ as the fulfillment of Old Testament prophecy. In the Armenian Orthodox tradition, where liturgy is a sensory experience that involves not just hearing the Word but also seeing and even tasting (in the Eucharist), these garments serve a sacramental function, making the invisible grace of God visible and tangible to the faithful. In summary, the iconography and biblical references within these liturgical garments are integral to their function within the Armenian Orthodox Church They encapsulate and present the core messages of the Christian faith, not only enhancing the beauty of the vestments but also enriching the liturgical and doctrinal understanding of all who gaze upon them Through these images, the garments speak silently but powerfully, conveying the eternal truths of the Gospel in a form that is both accessible and profound.

The works stand as testaments to the Armenian Orthodox Church's rich heritage of religious artistry, embodying a profound expression of faith and serving as a bridge between the divine and the faithful They showcase the unique ability of liturgical vestments to convey complex theological concepts and scriptural stories, enriching the worship experience and the spiritual life of the church community In the grand tapestry of Armenian art history, liturgical garments like this examined set are distinguished threads that highlight the enduring legacy of the Armenian Orthodox Church They are sacred vestments that have been carried through time, bearing witness to the unbroken continuity of a tradition that has been a cornerstone of Armenian identity and spirituality

Debbie is a senior in Kirkland House studying the History of Art & Architecture with a focus in Baroque/Rococo artistry, and a secondary in Medieval Studies. She is an outspoken advocate for the protection of antiquities and ancient sites that risk destruction and permanent damage at the hands of looters, vandals, the black market, and mismanaged cultural institutions around the world Outside of the academic world, Debbie enjoys collecting antique jewelry and books, visiting museums, and going on impromptu weekend trips

“Armenian Apostolic Church,” Encyclopædia Britannica, November 23, 2023, https://www britannica com/topic/Armenian-Apostolic-Church

Ian Gillman and Hans-Joachim Klimkeit, “Christians in Asia before 1500 ” (London: Routledge, 1999)

Michael Scott, “Ancient Worlds: A Global History of Antiquity ” (New York, NY: Basic Books, 2016)

Ronald T Marchese and Marlene R Breu, “Splendor and Pageantry: Textile Treasures from the Armenian Orthodox Churches of Istanbul.” (Istanbul: Çitlembik Publications, 2011).

Ibid

Henry R. Shapiro, “The Great Armenian Flight: Migration and Cultural Change in the SeventeenthCentury Ottoman Empire,” Journal of Early Modern History 23, no 1 (2019): 67–89, https://doi org/10 1163/15700658-12342606

Roberta R. Ervine and Hans-Jürgen Feulner, “On the ‘Preparatory Rites’ of the Armenian Divine Liturgy,” essay, in Worship Traditions in Armenia and the Neighboring Christian East (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2006), 93–118

Tiran Nersoyan, “Divine Liturgy of the Armenian Apostolic Orthodox Church: With Variables, Complete Rubrics and Commentary ” (London: Saint Sarkis Church, 1984)

Arman Andrikyan, “The Role of the Religious Heritage of the Armenian Diaspora in the History of National Pedagogy (Using the Example of Turkey and Iran),” Main Issues Of Pedagogy And Psychology 22, no 2 (2022): 66–81, https://doi org/10 24234/miopap v22i2 448

Adolphe Napoléon Didron, “Christian Iconography; or, the History of Christian Art in the Middle Ages ” (London: H G Bohn, 1851)

Ibid

Juan B Córtes and Florence M Gatti, “The Son of Man or The Son of Adam,” Biblica 49, no 4 (1968): 457–502, https://doi org/http://www jstor org/stable/42618333

Leslie Ducatt Baynes, “Eve, the Evolution of a Character from Genesis through the Pastorals” (thesis, University of Dayton Graduate Theses and Dissertations, 1995)

Marchese and Breu, “Splendor and Pageantry ”

Didron, “Christian Iconography ”

Jordan Ryan, “Golgotha and the Burial of Adam between Jewish and Christian Tradition,” Scandinavian Jewish Studies 32, no. 1 (2021): 3–29, https://doi.org/10.30752/nj.100583.

John 1:29-32

Lilly Nortjé-Meyer, “Ancient Art, Rhetoric and the Lamb of God Metaphor in John 1:29 and 1:36,” HTS Teologiese Studies / Theological Studies 71, no 1 (2015), https://doi org/10 4102/hts v71i1 2889

John 19:34

HUAJ: Has anything surprised you during your research?

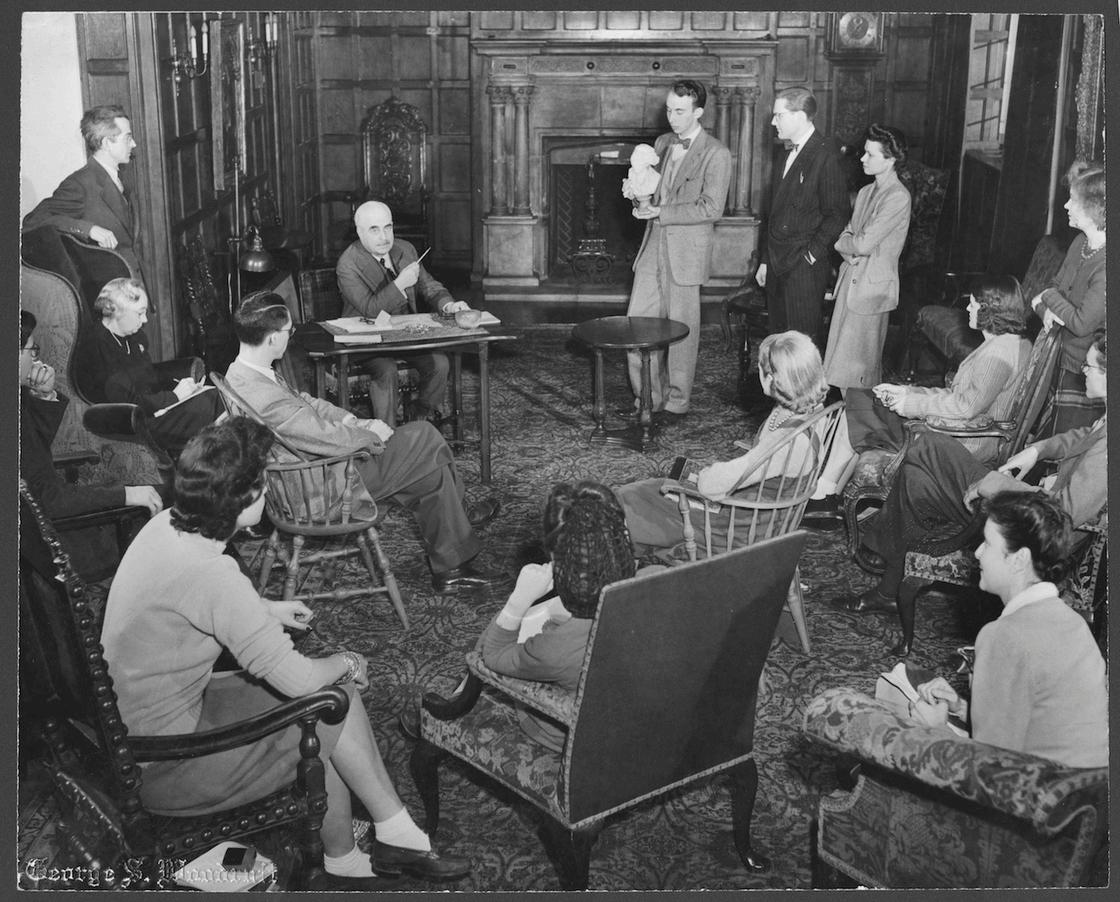

FP: So far, the most surprising thing that I found maybe is that how strong the connection between the two elements of theory and practice was And that was really unique Since the early twentieth century onwards, the importance of things like techniques, the history of techniques, but also technology, conservation, and collecting were really fundamental parts of the program. And the thing that has surprised me the most is that these were made into an incredible collection of drawings used for the teaching The collection of drawings of the museum is just outstanding, but also, many drawings were produced during the classes and for the classes themselves And those documents exist Most people just don't know about them It’s not only that these dialogues existed, but also that they produced some very interesting art The other thing, of course, is that because of these interests, much of the collections of the Harvard Art Museums were responding to the interests of the faculty. So in a way, you could say the collections of the museum reflect or mirror the interests of the department, and that is kind of unique It’s truly incredible

HUAJ: What are your hopes for the future of art history at Harvard and beyond?

FP: I think that we live in a moment nowadays in which some very important questions are being raised in recent art historical debates that resonate strongly with things that had been discussed in the past So I think this idea of bringing intellectual history down to the analysis of the art object in itself I think that it is something that we now see across the field in very different subfields that does resonate to me with the legacy inherited from the past

FELIPE

During the COVID-19 pandemic, I turned away from painting outdoor scenes containing landscapes and architecture and toward capturing interior surroundings. The pandemic, by placing me indoors, encouraged me to contend with and re-familiarize myself with the daily objects now relevant to my family’s daily lives This stifling collapse of external and social freedom pushed me to find interest and curiosity in life indoors, through foodstuffs around the house. Many items in this painting, like the jar of lemons in honey water or the jar of garlic cloves, depict fermentations or long processes transforming traditional food items. Others, like the canned fish or Shin Ramen, reflect some of the long shelf-life items that became popular during the pandemic In deliberately arranging these everyday items in still-life formats, I uncovered the sheer variety of color and vibrancy often hidden and unnoticed in them. These paintings hope to locate and illuminate the beauty of such objects.

Acrylic on panel, 18 x 18 in

“Beach Day” is a painting that examines the intersection between the abstract and the representational I developed the painting in layers, which were overseen by my painting professor, Kianja Strobert. I began the piece in half-scale studies, with multimedia and an express focus on mark making The abstract and graphic forms which occupy the majority of the piece especially the top left and bottom right of the composition are drawn from a collage I formed out of various charcoal and ink marks I then copied the collage onto panel using acrylic to use its nonrepresentational composition as a kickstart for my own painting This painting gets its name from a family beach photograph which I worked into the painting in its final stage. The stripes of the mother’s shirt mimic the graphic marks throughout the abstraction, and the shirt’s dark neckline parallels the oblong oval to its left. The baby’s gaze adds a direct address to the viewer that I felt contrasted nicely with the painting’s abstract base. This poses the question of how we view the non-representational, and how a piece can view us back from beyond the marks on the surface. With “Beach Day,” I hope to use both images and automatic mark making to create an engaging interaction between drastically different sources. I found the clash between these sources to be useful for exploring the tension between technique and the instinctive.

elevation. Although the current state of many of the remaining species is grim, drawing them every day gave me a deep appreciation for these beautiful creatures and allowed me to feel closer to the nature of Hawai‘i than I ever had before, despite being 5,000 miles away from home. I hope to play a small part in preserving the beauty of these birds and in spreading the message of their existence and importance.

Pen on paper, 16.5 x 12 in.

Psychology, Art, Film, and Visual Studies

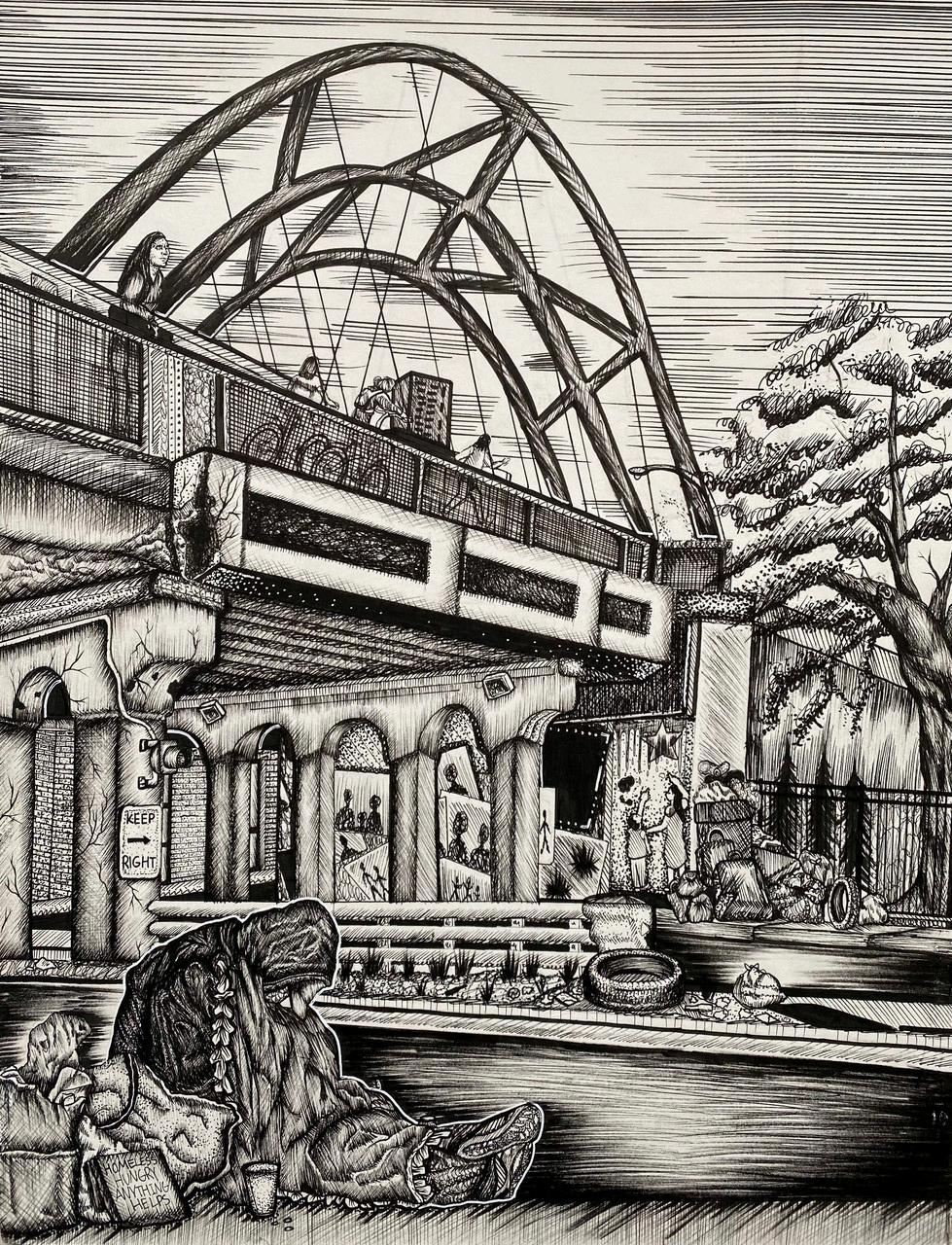

Formally an abandoned rail line, now a popular walking trail, the 606 is a greenway project that runs through Chicago's most notable northwest side neighborhoods. But, in actuality, it and other urban “beautification projects” are much more problematic than they seem. When the city invests in new amenities rather than work on fixing critical issues of poverty and crime, property values rise, and residents and business owners are displaced in exchange for wealthier counterparts (also known as gentrification) This piece captures an

piece captures an instance of this frustrating reality that I encountered when walking to my friend's house in Humboldt Park this past summer. Happy, predominantly white children and families ran along the trail as excessive trash, graffitied murals, overgrown weeds, crime, cracked support pillars, and homelessness raged below. The title references both the removal of residents and the movie of the same name, drawing connections in similar levels of chaos.

Eileen Ye ‘26

Computer Science, Mathematics

G I R L I N P A R K

Eileen Ye is a New York-based photographer currently studying at Harvard University. She is primarily focused on exploring themes of memory, place, and structure through film.

“Some things you forget. Other things you never do. But it’s not. Places, places are still there.”

- Toni Morrison, Beloved

Girl in Park is about nostalgia Girl in Park was taken on a cool early June day in New Windsor, NY, capturing the artist’s fascination with happiness in childhood.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

MARCUS MAYO

SUZANNE PRESTON BLIER

THOMAS CUMMINS

PATRICIO DEL REAL

SETH ESTRIN

SHAWON KINEW

YUKIO LIPPIT

CHRISTINA MARANCI

JENNIFER ROBERTS

HARVARD DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY OF ART AND ARCHITECTURE

(Unfinished painting on the reverse of) Franz Marc, Grazing Horses IV, 1911 Oil on canvas, 121 x 183 cm (47 5/8 x 72 1/16 in), framed: 1365 x 1981 x 51 cm (53 3/4 x 78 x 2 in) Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, Cambridge Bequest in memory of Paul E and Gabriele B Geier, 2014301