THINGS TO KNOW ABOUT OYSTERS AND MUSSELS

VOLUME 3 / ISSUE 1

Anybody who thinks mollusks are boring has not been paying attention. They come in smooth (think squids and octopuses) and crunchy (think snails and conchs), and also different flavored bivalves (such as clam, oyster, and mussel).1 Despite their mild-mannered appearance, they’ve caught the attention of lawmakers. In fact, some are outlaws. This article will explain laws and policies governing bivalves in coastal waters of the Gulf.

Background:WhentheOysterisYourWorld

Although mollusks might be on the small side, not counting giant squid, their role in the ecosystem is mighty. Most bivalves,2 for example, are filter feeders. This means they trap particles as they pump water through their gills. Our hero, the oyster, can clear 50 gallons of water a day under the right conditions. Nutrient removal is more and more important to the health of the coastal ecosystem as poorly maintained wastewater and agricultural runoff can pollute the water by adding too much nitrogen and phosphorous (aka “nutrients”). When water has surplus nutrients, large amounts of algae can form, which may smother existing wildlife and cause hypoxia (too little oxygen) when the dead algae decompose. Hypoxia is associated with mass die-offs in water systems, such as the dead zone that occurs in the Northern Gulf in late summer from the fertilizerheavy Mississippi River.

Salinity

Oysters grow in salty waters, but just how salty depends on where you get your information and where the oysters are. Waters are characterized by the amount of salt they contain, with freshwater having the least – less than 0.5 parts per thousand (ppt). The salinity of seawater, on the other hand, ranges between 33 and 37 ppt. Waters having salinity levels between fresh and sea are described as brackish. This is where oysters live.

The sweet spot for salt for oysters is said to be at about 19 ppt, but they can tolerate a range in salinity. Extremes, however, will affect their health and growth. According to a Florida conservation group, salinity above 25 ppt reduces oyster survival, but if salinity drops to 10 ppt, the oyster can close its

1 Note: This article was not written by a scientist.

2 “Bivalve” refers to the fact that there are two shells, which are hinged.

Credit: Pearson Scott Foresman

shell and wait it out. According to one publication, oysters in Louisiana have higher growth and survival rates at 5-15 ppt, whereas Chesapeake Bay oysters flourish at 15-22.5 ppt.3 The ability to survive in different levels of salinity is known as being euryhaline. Temperature can impact oysters’ ability to withstand changes in salinity.

Experience shows that the above information can be taken with a grain of salt. For example, Texas’s first commercial oyster farm, the Texas Oyster Ranch, is in Copano Bay where the salinity is 28.8 ppt on the day this was written. Yet the Texas Oyster Ranch is looking at its third year of oyster harvests. One source notes that higher salinity “results in an increase in the rate of growth and fattening of the oysters. In addition, the taste of the oyster is improved as the salt content increases.”4

ReeferMadness

Oysters are not social animals, but they do best in a crowd. Oyster reefs are formed by years and years of oysters piling on top of and next to each other. Reefs make it easy for oysters to reproduce, as the eggs and sperm released into the water can cross paths. Also, oysters need a hard surface to

reef. Credit: Harte Research Institute

Oyster reefs improve biodiversity in coastal waters, providing hard structures within the s generally soft-bottomed estuaries.6 Reefs create nooks and crannies in which crabs, shrimp, and fish can hide, eat, or be eaten. Over 300 marine species use oyster reefs. Also, the reefs slow wave energy to reduce coastal erosion. Because of their role in the ecosystem and economy, reefs are protected, defined as a “critical area” under Texas Natural Resource law. Even oil and gas development needs to take care to prevent destroying oyster reefs. Tex. Nat. Res. Code § 52.032.

Oyster reefs used to cover more area in Texas than they do now, and oyster harvests were big business. In fact, in 1943 the Texas Supreme Court had to consider whether 40-some years of discarded oyster shells at a Tres Palacios Bay oyster house added real estate for the oyster house’s owners. 7 There were so many oyster shells that they filled up the water along the 600-foot pier to the oyster

3 V.R. Vansickle, et al., Barataria Basin: Salinity Changes and Oyster Distribution, p.5 (Sea Grant Pub. No. LSU-T-76-002).

4 Id.

5. Lindsey Marie George, et al., Oyster reef restoration: effect of alternative substrates on oyster recruitment and nekton habitat use, Journal of Coastal Conservation: Planning and Management, Vol. 19, No. 1 (2015).

6 Patrick M. Graham, Terence A. Palmer, Jennifer Beseres Pollack, Oyster reef restoration: substrate suitability may depend on specific restoration goals, Restoration Ecology, Vol. 25, No. 3 (May 2017).

7 Lorino v. Crawford Packing Co., 142 Tex. 51 (1943).

Oyster

house – extending the land into the bay almost the length of two football fields. The Court held that just because the State-owned submerged land was now dry land did not mean that the State had given up ownership of that property.

Some oyster reefs are declining in size and productivity. According to the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department (TPWD), which manages oysters, Galveston Bay oysterers could catch 730 oysters per hour in 2000-2003, but from 2019-2022, caught only 221 oysters per hour. Ninety percent of public oyster reefs are in Galveston, Matagorda, or San Antonio bays, which TPWD says is because the bays have “good freshwater inflows,” i.e. the rivers bring enough water to keep the bays’ salinity at good levels.

The State closes oyster reefs to harvesting from time to time. Two agencies have the authority for different types of closures. For example, when the water contains bacteria or toxins due to harmful algal blooms, contaminant spills, or fecal pollution from water runoff due to storms, the Texas Department of State Health Services will close the area. Such closures only last for the time it takes the water to clear and the oysters to cycle out the contaminants. Other closures can be due to over harvesting or some other reason leading to a low abundance of legal-sized oysters. TPWD makes those closures. For example, Tres Palacio Bay, discussed above in the case with so many oyster shells, is now closed to oystering. In December 2024, TPWD announced it was closing all oystering in areas of Galveston and Matagorda bays based on having “low abundance of legal-sized oysters.” Oyster area closures typically are for two-year periods which is about the time it takes oyster larvae to latch on and grow to a harvestable size. Other areas, such as Christmas Bay and the Mesquite Bay Complex, are closed for longer time periods. It depends on the basis for the closure.

Other Gulf states close areas to oystering. One closure of note is Florida’s Apalachicola Bay which used to produce 10 percent of the nation’s oysters. Decreased freshwater inflows due to drought, as well as multi-state disputes over freshwater allocation, increased the bay’s salinity causing the oyster fishery to collapse, according to Florida in (unsuccessful) arguments to the U.S. Supreme Court.8 In

8 Florida v. Georgia, 592 U.S. 433 (2021). The Supreme Court held that Florida did not demonstrate that reduced freshwater flows were the cause of the oyster fishery collapse. Georgia argued that mismanagement was the cause, and the Court agreed: “while Florida was harvesting oysters at a record pace, it was simultaneously reshelling its oyster bars at a historically low rate.” According to the Court, an expert had recommended that Florida reshell 200 acres of reefs annually, but in the 10 years before the collapse, Florida had reshelled 180 acres in total.

2020 Florida suspended oyster harvests in Apalachicola Bay through 2025. A rebuilding plan is underway to create 1,000 acres of reef habitat.

One way to protect reefs is to limit oyster harvesting. There are all sorts of rules on when, who, and where for oyster harvests. Oyster season in Texas is from November 1 to April 30. Different licenses are required for recreational and commercial oyster harvesters, and oysters may be taken only from approved areas. Recreational harvesters are limited to using tongs and dredges no bigger than 14”, while licensed commercial harvesters may use other mechanical means.9 There’s a two-sack limit for recreational harvesting. A sack is the general size used to measure oyster harvests and weighs 110 lb in Texas. 31 TAC § 58.11(20). A sack volume to define a sack: 3225.63 cubic inches, so bring a ruler and a calculator.

Oyster dredge. Dredges can be a cost-effective way to harvest oysters, but can harm reefs, sometimes permanently, by scraping too much material off the reef.

Texas requires wholesale fish dealers to put at least 30 percent of the shells from the oysters they buy back into the water to help reefs. The Harte Research Institute also has a program, Sink Your ShucksTM, which gathers oyster shells from restaurants and others to build oyster reefs. The program is beginning its 16th year, having created over 45 acres of oyster reefs in the Aransas Bay area. TPWD also adds material, known as cultch, to build reefs, totaling 550 acres along the Texas coast. This year, the agency plans to grant $8.2 million to fund reef restoration using large boulders for reefs that will prevent harvesting oyster by dredges.

Mariculture:AquacultureintheSea

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) reports that sales of farm-raised oysters and clams has increased 30 percent since 2018. Oyster farms stock the eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica), a native species found along the Gulf and Atlantic coasts. Under Texas law, it is the only species of

9 Tex. Parks & Wild. Code § 76.101(a)-(b).

Hand-held oyster tongs, described as two rakes facing each other.

oyster that may be grown commercially. According to TPWD, there are 12 commercial oyster farms along the Texas coast.10 The state calls it “Cultivated Oyster Mariculture,” but some give it a more Texas name: Oyster Ranching.

Most oyster farming is done in floating cages, known as off-bottom cages, which are placed close to shore. Farmed oysters, like the naturally grown ones, filter their food from the water, and oyster farming is considered ecologically sound, aside from occasional debris from plastic ties and lost cages. Objections to oyster farming include that the cages interrupt the view, they can impede boating, and they attract birds which poop a lot, fouling the waters.

Texas was the last Gulf state to begin the practice, which was authorized by the legislature in 2019. Alabama, for example, set up its first off-bottom oyster farm in 2009.11 Some advantages to oyster farming include developing uniform sized oysters with a deeper “cup” resulting in meatier oysters. This allows those oysters to be sold at a higher price to restaurants for oyster bars instead of selling to canneries. Oyster farms are developing identities associated with the specific flavor profiles of their oysters, similar to how wines in France are based on location, or terroir. This can lead to even higher prices for those oysters.

While other types of shellfish farming occur around the Gulf, Texas authorizes only oyster mariculture; oysters are also the only farmed marine mollusk in Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi. In contrast, hard clam (Mercenaria mercenaria) farming is the largest shellfish mariculture industry in Florida. Just over half of Florida’s 336 shellfish farmers only raise hard clams, according to the USDA.

GulfShellfishMaricultureSales

Oyster 2018 Hard Clams 2018 Hard Clams 2018

Source: USDA, 2023 Census of Aquaculture. * D means the value was withheld “to avoid disclosing data for individual farms.”

The USDA reports that nationwide sales of oysters grew from $284,938,000 in 2018 to $326,980,000 in 2023.

10 TPWD Press Release, Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission Approves Proposed Oyster Mariculture Rule Revisions, Temporary Closures of Oyster Restoration Areas in Galveston Bay (Nov. 12, 2024).

11 William C. Walton, LaDon Swann, Role of Sea Grant in Establishing Commercial Oyster Aquaculture through Applied Research and Extension, Journal of Contemporary Water Research & Education, Vol. 174, No. 1 (Dec. 30, 2021).

12 The USDA reported no Texas oyster mariculture, but two farms of “other mollusks.” 2023 Census of Aquaculture, p. 5.

PickingUptheEmpties

It has been said that she sells seashells down by the seashore. If that seashore is the Padre Island National Seashore (PINS), however, she’s just broken the law. PINS allows visitors to keep one gallon of seashells before returning home, but those shells may not be sold. Also, only “unoccupied seashells” may be kept. 36 C.F.R. § 2.1(c).

Texas state beaches generally do not have a quantity restriction, although only the empty shells may be kept. A specific rule prohibits taking or killing “shell-bearing mollusks, hermit crabs, starfish, or sea urchins” around South Padre Island. The ban is in place from Nov. 1 through April 30, and extends seaward 1,000 yards. 31 Tex. Admin. Code § 57.972(g)(11). The low tides at winter meant the beaches were being picked bare, harming the ecosystem.

Mussels

Marine mussels are bivalves that are more closely related to oysters than they are to freshwater mussels, despite having the same last name. Apparently, some marine mussels evolved into freshwater ones 400 million years ago and never looked back. Mussels hang out in beds, rather than reefs. Once they are adults they move very little, but as larvae they can latch onto the gills or fins of fish and see the world before settling down to their mussel beds.

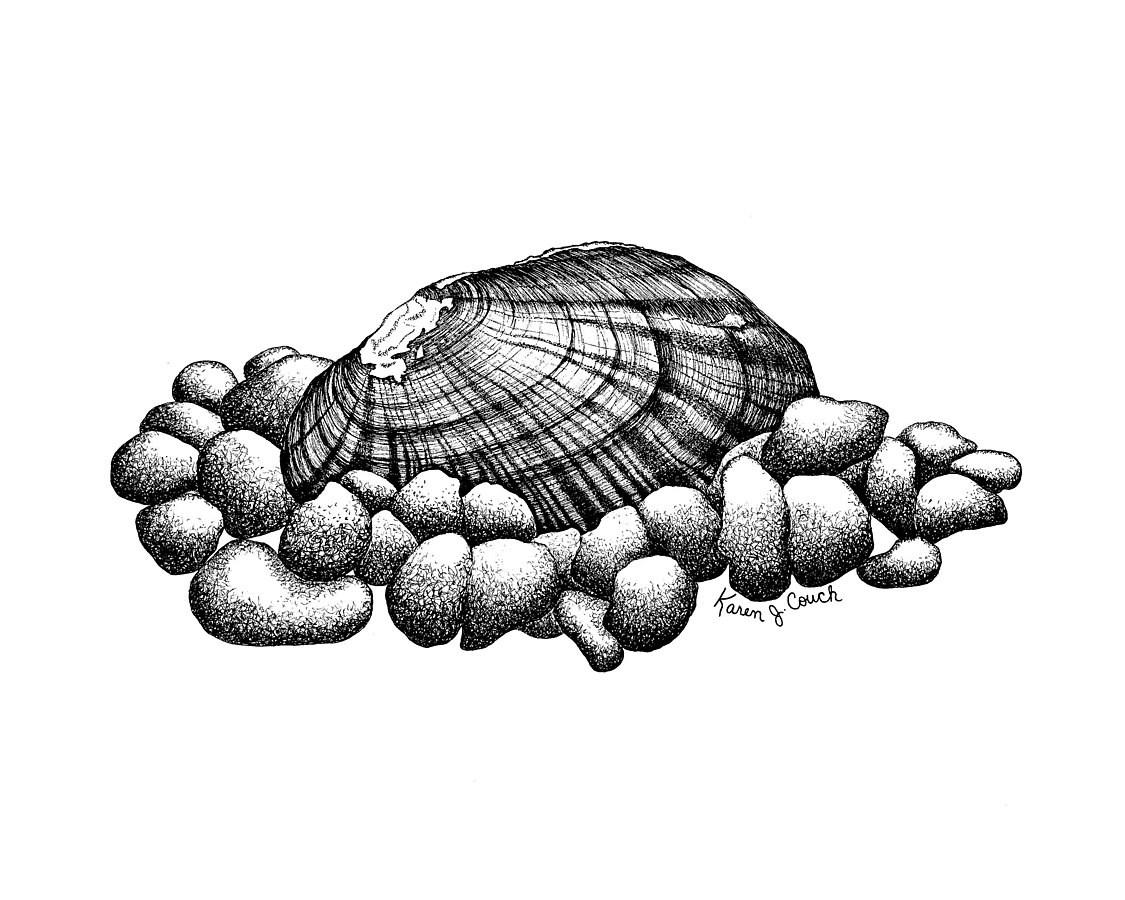

This bivalve rumspringa is just one surprising fact that may make freshwater mussels more interesting, if less edible, than oysters. Note that eating freshwater mussels is prohibited in Texas. That might not be a loss to diners. The Internet describes freshvery bland and much more rubbery” than saltwater mussels, “unpalatable to hu-

The newly-listed species are the Guadalupe Fatmucket, Texas Fatmucket, Guadalupe Orb, Texas Pimpleback, Balcones Spike, and False Spike (all endangered) and Texas Fawnsfoot (threatened). Freshwater mussels may be chewy, but you can’t beat the names. Find a better sounding insult than Texas Pimpleback or Guadalupe Fatmucket. They join the Ouachita Rock Pocketbook and Texas Hornshell as endangered species. Four more species are proposed for listing as endangered: Texas Heelsplitter, Freshwater mussel. Credit: Karen J. Couch, US FWS

There are 51 species of freshwater mussels in Texas. Almost 20 percent of them are considered at risk of extinction. As a matter of fact, six Texas species were identified as endangered species in 2024 under the federal Endangered Species Act (ESA), meaning they are at risk of extinction in the foreseeable future, and one species was listed as threatened, meaning it is at risk of becoming endangered. 89 Fed. Reg. 48034 (June 4, 2024).

Louisiana Pigtoe, Mexican Fawnsfoot, and Salina Mucket. Texas protects five more as threatened species: Brazos Heelsplitter, Sandbank Pocketbook, Southern Hickorynut, Texas Pigtoe, and Trinity Pigtoe. 31 Tex. Admin. Code § 65.175.

The primary threat to mussels is loss of freshwater habitat, exacerbated by effects of climate change, according the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. While the mussels can “tolerate dewatering” to some extent, according to the agency, the “increased frequency of low flow events (from groundwater extraction, instream surface flow diversions, and drought) combined with a decrease in cleansing flows (from reservoir management and drought)” as well as dams, adversely impact mussels. 89 Fed. Reg. at 48049-50. Poor water quality, such as increased fine sediment, also reduces mussel survival.

The 2024 ESA listing designated a total of 1,577.5 miles of critical habitat in several rivers for those mussels. The ESA makes it illegal to harm a listed species, which includes causing significant disruptions to a species’ breeding, eating, or sheltering. 50 C.F.R. § 17.3. Thus, because mussels depend on a certain quantity of water to live, intentionally reducing water in their critical habitat could be considered a violation of the ESA.

The State of Texas sued, challenging the ESA listing of Texas mussels as “infringing on Texas’s sovereign interests,” calling it the “latest attempt to undermine the Texas economy.”12 The State argued that its protection efforts were sufficient to protect the species, describing its laws and regulations as “robust.” For example, it is a crime to take a mussel listed by Texas as threatened or endangered. 31 Tex. Admin. Code § 57.157. But if you have a fishing license, you can take up to 25 lb of non-listed mussels a day from approved waters. Just don’t eat them.

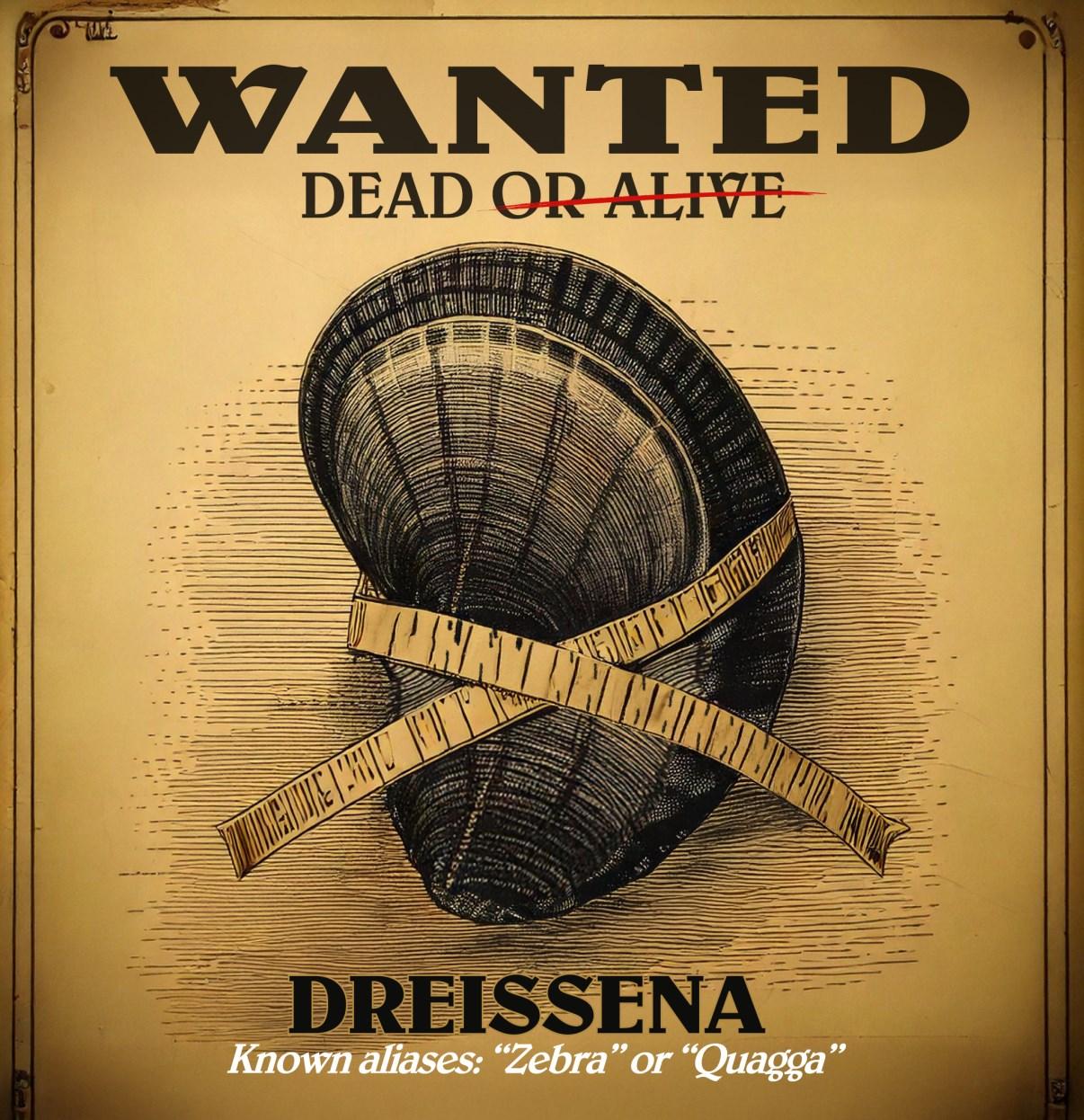

MusselOutlaws

It seems unlikely that an immobile, spineless creature with no detectable personality could be dangerous, yet zebra mussels and quagga mussels are. These small (1.5”) mussels come from the family Dreisennidae, and this crime family is responsible for billions of dollars in damages in freshwaters across the United States. They came into the country in the late 1980s, likely in ballast water.

They have thrived here, outcompeting indigenous mussel species and clogging water intake units and other submerged infrastructure. Zebra mussels are in 31 states; quagga mussels are in 18. So far.

12 See State of Texas v. U.S. Dep’t of the Interior, (N.D. Tex. Complaint filed Oct. 28, 2024); Attorney General of Texas Press Release, Attorney General Ken Paxton Sues Biden-Harris Administration Over Unlawful Weaponization of Environmental Law (Oct. 29, 2024), respectively.

Texas Pimpleback (Quadrula petrina). Credit: Joel Sartore

With these mussels having few predators in U.S. waters, it takes chemicals, physical scraping, or smothering to clear their beds from pipes, docks, and vessels. They grow fast and often are inadvertently transported from lake to lake, including on recreational boats.

The zebra and/or quagga are the targets of numerous federal and state laws which have failed to stop them. The laws prohibit their import or restrict their release or transport. When zebra mussels are found on a boat – dead or alive –Texas law says that the boat (and its unintended cargo) must go to a place to get the mussels removed before going anywhere else, and TPWD must get written notice from the boater identifying the body of water the boat was in when the mussels were discovered. Tex. Parks & Wild. Code § 57.113 (g). This information is used by the State and the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) to pinpoint the mussels’ spread. The better to target their removal.

Credit: Juan Canchola, Harte Research Institute

The USGS has newer tools to attack mussels and other invasives. It can identify the species’ presence in water samples using eDNA, which looks for traces of the animal, rather than the animal itself. Then the mussels’ genes are used to stop them.13 This could mean sending in “mutant” mussels that would halt reproduction of future generations, or wildlife managers could use modified treatment methods that target only a specific species of mussel based on its RNA. These techniques would reduce collateral damage from broadly applied chemical treatments and could be more effective, too.

Conclusion

While wildlife management strives to maintain sustainable levels of the creatures we need ecologically and economically, such as oysters and mussels, it is not easy. Competing interests such as demand for freshwater means the ideal result is not always possible. The more we know about bivalves and the roles they play in the ecosystem, the more likely conserving them may be an easier decision to make.

13 See USGS, Developing RNA Interference to Control Zebra Mussels (June 2019).