01 / introduction X methodology

01.1 / introduction

Serving others unconditionally and without expectation of compensation may seem a rare practice in today’s world. For most people, pondering on this form of selflessness conjures images of humanitarian aid and charitable action in response to physical disaster (Weiner 1992); this form of action only comes about in extreme circumstances where human systems are subverted beyond control. However, for others, serving others unconditionally is an embedded way of life, prescribed by socio-cultural pedagogy and ritual convictions. Sevā – in Sanskrit referring to selfless and sacrificial action for the benefit of others – is one of these ingrained ritual practices which millions of people across the world apply to their daily lives (Virdee 2005).

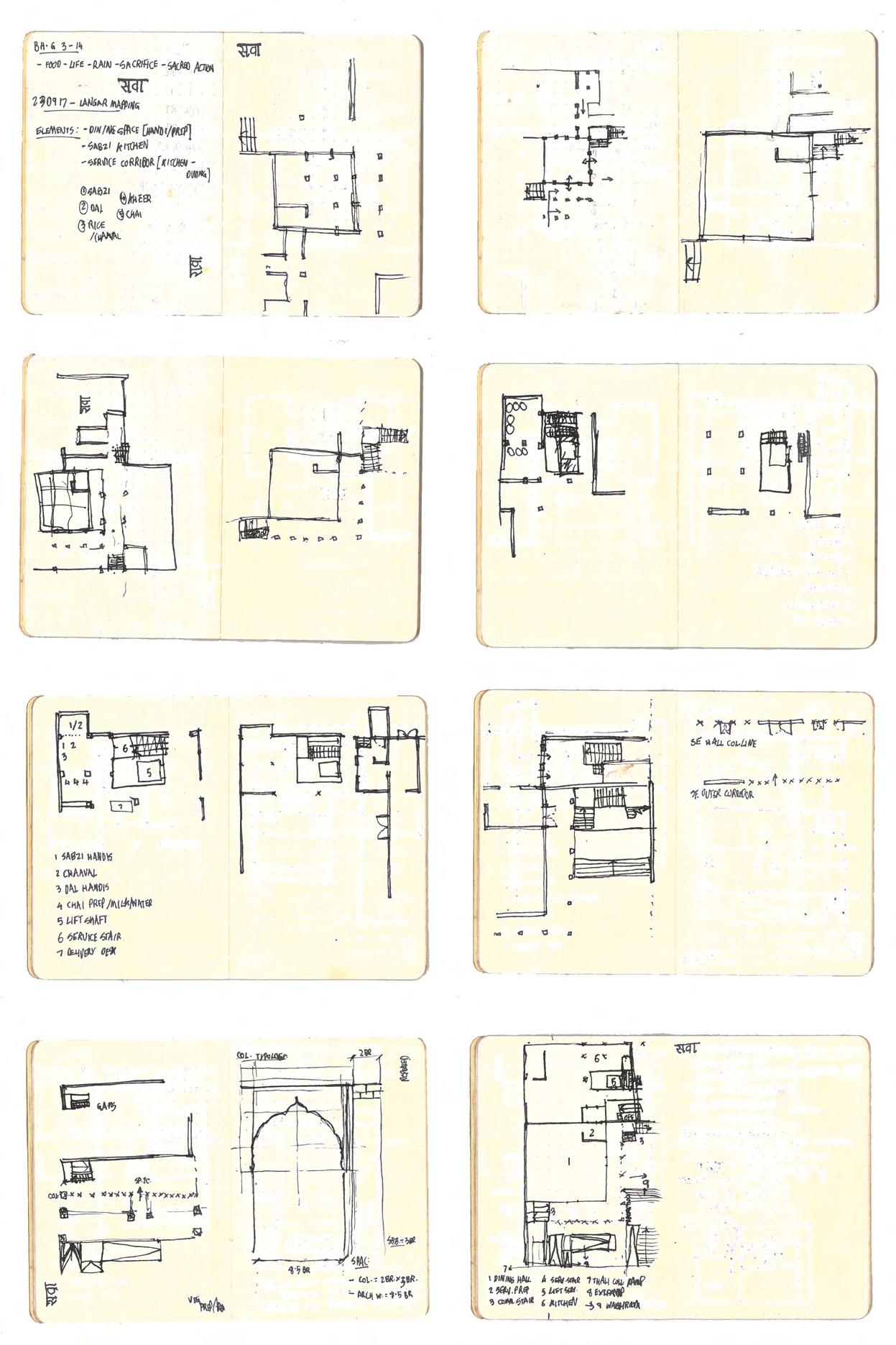

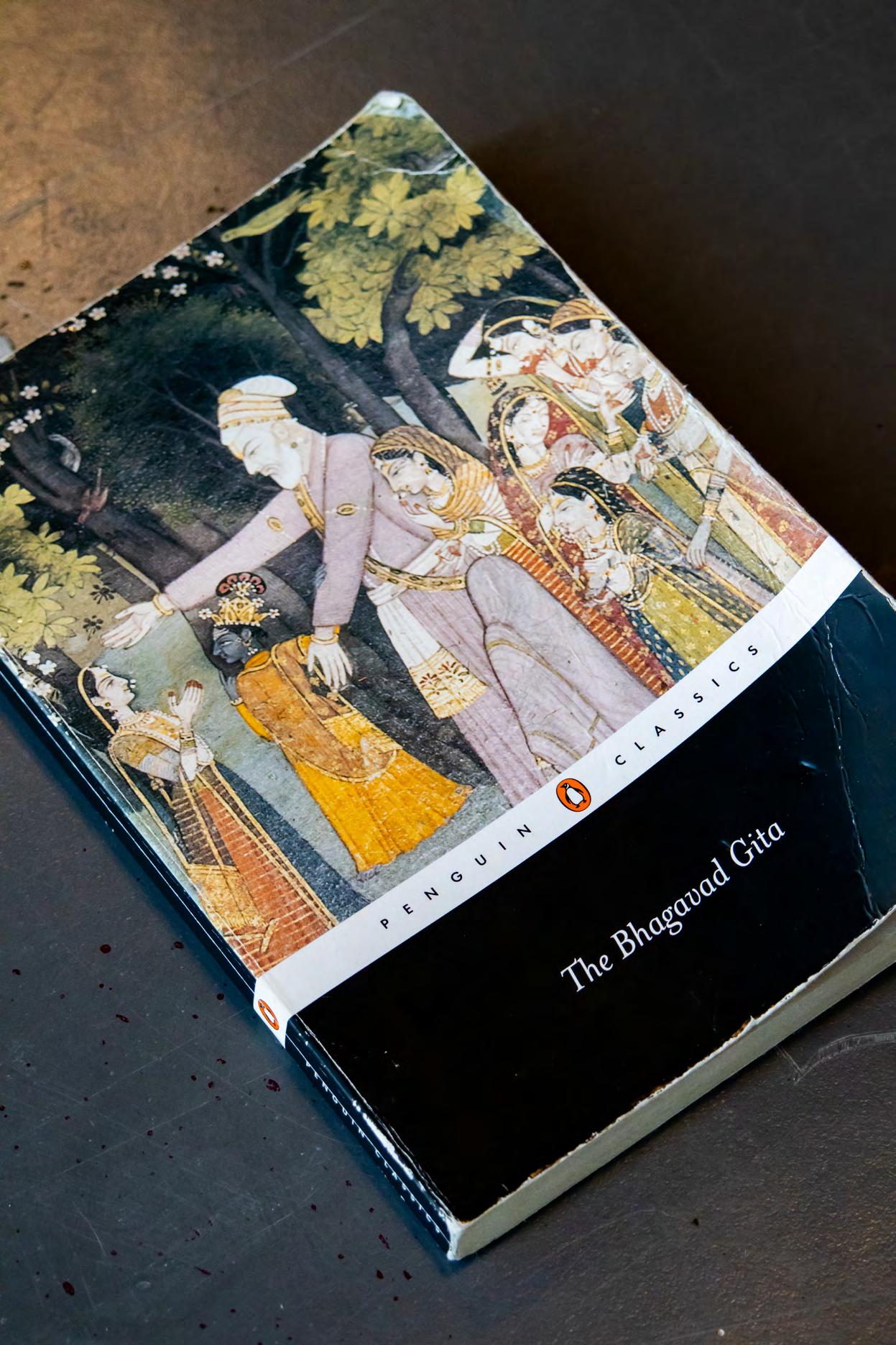

Intersecting religious and humanitarian modalities, sevā is a culture of social support that originated during imperial periods of development in north India (Schlecker and Fleisher 2013). Contemporary exercises of sevā may be witnessed in Sikh langar, which involves feeding any person of any status for no cost (P. Singh and Fenech 2014). The world’s largest continuing orchestration of sevā through langar occurs at the Golden Temple community kitchen in Amritsar (Punjab, North India) which feeds hundreds of thousands annually (A. Pandey et al. 2015). This socio-cultural infrastructure depends on prescribed duties of sevā to ritually distribute food resources to the local community and is primarily perpetuated by volunteerism and philanthropic contributions. This dissertation employs an autoethnographic methodology (Figures 3a & 3b), rooted in the personal and voluntary experiences of the author at the Golden Temple, to present the potentials of sevā-led society.

Sevā-based practices are rooted in theological commentaries; these scriptures often tie human ecologies of inter-communal care to wider environmental systems, attempting to outline the

sevā / the architecture of serving others 8

extended importance of sacrifice for both people and nature. Summarily, such eastern approaches position sevā at the crux of forging communal bonds and establishing conviviality and commensality. Selfless service, as opposed to operating within the bounds of transaction and capital, is often presented as an effective decolonial critique of modern systems of social support (Osella 2018). Sevā at the Golden Temple in Amritsar thus provides a contemporary methodology towards altering capital-driven community organisation, through the removal of profit and selfgain from resource provision. This dissertation selects literature which positions sevā as a central instrument in structural change, recognising that the interrogation of kitchens as a concept may alter its focus. Sevā provides a decolonial point of departure, where this culture of service actively opposes legacies of transactional and top-down community-making.

Collective culinary practices free of transactional reciprocity allow the Golden Temple community kitchen to exploit sevā as a method of strengthening community bonds (Sohi, Singh, and Bopanna 2018). Individual agency paired with a culture of sevā builds a critique of current welfare mechanisms; participatory ritual actions to serve others may allow everyday people to have a role in spatialising justice and improving urban equality (Cruz and Forman 2023). Simultaneously, this dissertation acknowledges that ideologies such as sevā inevitably face physical and political barriers. Conflictions between philanthropic action and individual ability, for instance, may demonstrate that adopting sevā-led society does not occur without encountering tribulation in realworld application. Utopian idealisation and declining outcomes in ISKCON (International Society for Krishna Consciousness) communities – driven by religious conceptions of sevā – perhaps exemplify the limits that sevā practices face (Gelberg 2011). Nevertheless, supported by established theology, sevā provides an alternative political lens for analysing linked socio-material and ecological structures.

9 01 / introduction X methodology

sevā / the architecture of serving others 10

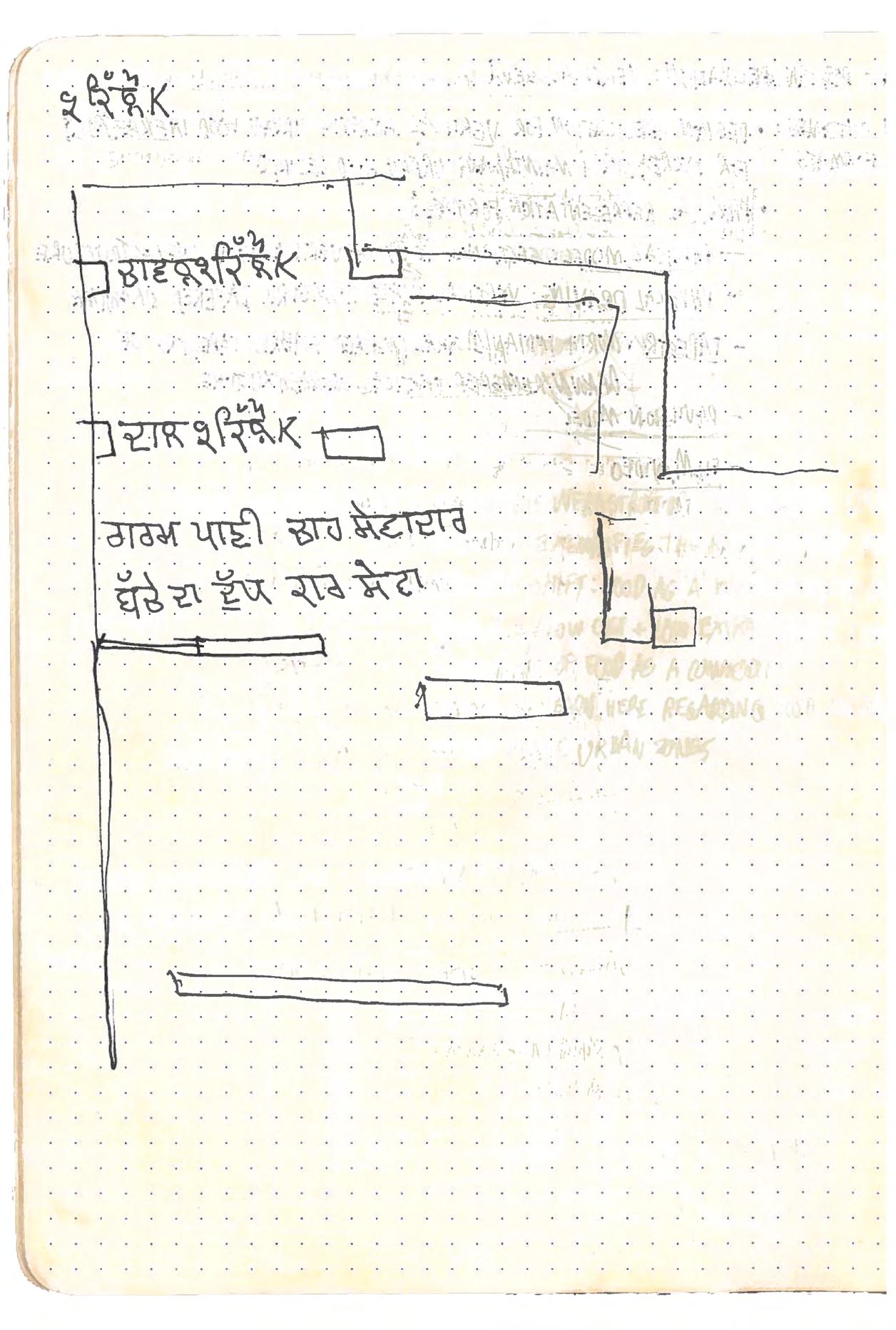

Figure 03a - author’s personal sketches documenting spatial experience

11

01 / introduction X methodology

Figure 03b - partial plan sketch by community kitchen dal chef

sevā / the architecture of serving others 12

Figure 04 - regular service volunteers at the community kitchen

01.2 / methodology

This dissertation expands from the author’s individual participatory experiences at the Golden Temple in Amritsar, connecting this autoethnographic approach to wider issues relating to social structure and communality. The primary research which informs commentary and analysis through the written discourse constitutes personal experiences, photographic evidence, and sited exchanges (Figure 04) during participation. Where the dissertation refers to qualitative aspects of the operation of sevā at the Golden Temple, autoethnographic participation forms the primary source and basis for the comments and is indicated by an in-text symbol (ॐ). This primary method is paired with academic references to form a wider analysis of the emerging issues, which in combination aim to holistically respond to the dissertation’s research question, ‘how can sevā-led spatial practices operating at Amritsar’s Golden Temple inform alternative mechanisms of social support?’

Allowing the discourse to employ autoethnography, through contributing personal commentary, impacts the argument in a number of ways. The blending of observation and participation in the gathering of evidence may particularly influence analysis, as service and participatory action are the key components in question. The positionality of the author both as witness of the observed mechanisms as well as participant within becomes a point of departure in itself. Nevertheless, integrated autoethnographic analysis is viewed by the dissertation as an effective lens through which the participatory practice of sevā may be deconstructed.

13 01 / introduction X methodology

ॐ

sevā / the architecture of serving others 14

Figure 05 - Sri Harmandir Sahib langar kitchen building

02 / individual सेवा X golden temple

02.1 / golden temple X langar

The Sri Harminder Sahib – more commonly known as the Golden Temple – is situated in Amritsar, a city in the north Indian state of Punjab. This temple is the most significant pilgrimage destination for Sikh devotees across the world as a revered shrine for worship (Virdee 2005). The central space for worshippers involves the famed Golden Temple, a two-storey, gold-plated building positioned at the centre of a square basin of holy water (the amrit sarovar). Pilgrims circulate around this pool, taking opportunities to prostrate and bathe at its banks as dictated by established ritual practices. A single bridge connects the marble-paved, circumambulatory route around the holy pool to the small island on which the Golden Temple sits. This bridge – which hundreds of pilgrims queue to cross at every moment of the day – serves as a spiritual connector between mortal humanity and the immortal significance of the Guru’s teachings (Sikhnet 2016). Many believers view the Golden Temple as a singular architectural space that truly brings heaven to earth; this spatial experience becomes an embodiment of serenity and harmony where one is given time and space to meditate on mortal life. Movement through the various spaces in and around the Temple, more often than not within large masses of other pilgrims, places the individual within wider, communal acts of prostration: an immensely humbling practice (ॐ).

A foundational pillar of this Sikh pilgrimage experience is langar – which refers to the ritual provision of food for both devotees in need and the wider community (P. Singh and Fenech 2014). At the Sri Harminder Sahib, langar is provided at an on-site community kitchen (operated by volunteers) which is located a few steps outside the entry gate to the Golden Temple space (Figures 05-07).

15 02 / individual सेवा X golden temple

sevā / the architecture of serving others 16

Figure 06 - users entering langar kitchen (video)

17

02 / individual सेवा X golden temple

Figure 07 - users exiting langar kitchen (video)

sevā / the architecture of serving others 18

Figure 08 - langar service at the community kitchen

Having circulated the central basin, visitors exit through the southern gate from which they entered, bringing them to a ramped entrance to an arched, red-brick building – the langar hall. Langar refers to ‘the main meal which is served all afternoon to every visitor, irrespective of their social standing or religious affiliation’ (A. P. Pandey and Pandey 2018). This meal represents Sikh action to provide unrestricted access to communal food resources in line with the principles of langar set out in the Guru Granth Sahib –‘may the iron pots of Langar be ever warm (in service)’ (M. Singh 2008). The provision of these food resources is seen as ritual duty for Sikhs, with the langar kitchen being the space in which this ritual practice of food service is hosted. The typical meal served to users of the community langar kitchen consists of two dals (lentil servings), rice, chapattis (unleavened flatbreads) and kheer (a sweet rice pudding) – portioned within a circular, subdivided steel plate or thali – and consumed on the floor whilst cross-legged in pangat (McWilliams 2014). The langar hall’s homogeneous service reflects its inclusive vision, serving all regardless of background or socio-economic status.

The orchestration of langar at the Sri Harminder Sahib remains a highly efficient and systematic distribution programme, serving more than one hundred thousand people daily (A. Pandey et al. 2015). Cycles of langar service tend to last only a few minutes: users in groups of one hundred are ushered into the central hall after receiving one thali, a bowl, and a spoon – in tightly compacted rows, devotees sit in pangat, ready to receive their share of the langar into their precisely portioned thalis (Figure 08). As soon as the first person is seated, service begins: kitchen volunteers rapidly pace the langar hall with baskets of chapattis and buckets of dal in hand, distributing and replenishing food directly into the compartments of thalis below. Within minutes, it is expected that people finish their meal and promptly depart the hall, placing their used utensils in the washing area located directly adjacent to the exit doors, where thalis and other metalware is ritually cleaned and circulated back to the hall entrance for the next cohort (ॐ). A highly planned efficiency lies in this serving system, enabling the kitchen to maximise the number of people it is able to serve on a daily basis, as well as operate in a strikingly rapid manner. This efficiency is grounded in the ritual and participatory actions taken by kitchen volunteers (ॐ), turning the cogs of langar service that many local people in Amritsar depend on.

19

/ individual सेवा

02

X golden temple

sevā / the architecture of serving others 20

Figure 09 - Volunteerism X vegetable preparation outside the langar hall

02.2 / langar X सेवा

The efficiency and rapid nature in which users of the langar kitchen are served is almost exclusively driven by volunteers’ individually held principles of [kar]sevā / सेवा. In this context, sevā refers to participatory action in attempts to improve communal wellbeing and serve others (Sohi, Singh, and Bopanna 2018). Langar food service therefore connects ritual Sikh duty to act for the welfare of others with the notion of community food provision, directly linking communal nutrition to voluntary action. Each individual volunteer bears an internalised obligation to participate in the operation of the langar hall and community kitchen, and thus contribute to the wider nutrition it provides to others. Sevā-led, participatory actions – ranging from the simple act of distributing chapattis into the hands of users to the cooking of large handis (pots) of dal for a day’s service – facilitate the operation of the langar kitchen as a whole. Sevā and the individual convictions of sevadars (volunteers) to serve others through langar drive the community kitchen’s efficiency and its ability to both provide food resources and support welfare (ॐ). There are of course limits to who can serve and participate in the kitchen space. The driving principle of karsevā also guides sevadars to act without expectation of reward (SikhiWiki 2015). Holding and operating on these beliefs, where returns for service are not necessarily tangible, illustrates the idea that ritual acts of serving others in the langar kitchen become the self-sustaining resource for its function.

One’s experience of the langar kitchen at the Golden Temple may instil belief in the power of accumulated individual action to mobilise social infrastructure (A. P. Pandey and Pandey 2018). Systems of individual culinary action proliferate the langar hall building; the two-storey brick structure hosts a series of interconnected spaces that allow sevā-led gestures of food preparation, cooking, and service which cumulatively allow the infrastructure to serve people. These interrelated, voluntary actions form chains which web through the sevā space, consolidating its capacity as a holistic community resource. Radhika Chakraborty (2022) references

21 02 / individual सेवा X golden temple

sevā / the architecture of serving others 22

Figure 10 - Utensil washing voluntary service outside langar hall

these connectivities whilst studying diasporic sevā-led action, commenting on the ability of ritual and communal acts of service to strengthen ties within cultural systems. This may clearly be witnessed within the Golden Temple langar kitchen (ॐ); in any given space, a plethora of individual acts of service combine to ensure the building may continue to thrive, despite the existence of resource constraints and consequent impacts. The effective function of this infrastructure is reinforced through contributory sevā actions carried out by users of the langar kitchen. Utensils and cutlery are exclusively washed by devotees (Figure 10) wishing to assist after their meal and vegetables are prepared by pilgrims whilst they take araam (post-langar rest). Consequently, continuous cycles of individual sevā perpetuate the langar kitchen’s social impact, and ensure its security as a local food resource both for urban residents and religious pilgrims. The collective power of these sacrificial actions drives the Golden Temple as a sociocultural infrastructure (ॐ).

At the Sri Harmandir Sahib langar kitchen, it becomes clear that individually initiated and orchestrated sevā practices form the basis of social harmony, food security and commensality. Sohi relates this individual ‘ritual participation’ in sevā-led action to Sikh community wellbeing (Sohi, Singh, and Bopanna 2018), outlining the positive impact that frequent participatory actions to serve others may have. This notion is evidently demonstrated at the Golden Temple langar kitchen: sevadars’ motivation to serve others is visibly self-perpetuating in the langar hall as they move with vigour and intensity to nourish every hungry pilgrim (ॐ). The historically ritual manner of food service here has led to the provision of meals becoming a harmonious practice that people take joy in. Sohi further highlights the importance of sevā for community solidarity and social cohesion; collective langar service of the same meal to groups of one hundred people, unified in pangat, facilitates communal feelings of nourishment and food security. Despite occasional disruptions to the flow of resources due to external factors, the generally cohesive, sevā-reinforced service of meals in the langar kitchen creates a commensality that permeates throughout the building, conjuring a tangible sense of harmony for those who enter (ॐ).

23

/ individual सेवा X golden temple

02

sevā / the architecture of serving others 24

Figure 11 - Volunteerism X chapatti making at the Golden Temple

03.1 / सेवा X theology

सेवा or sevā is derived from the Sanskrit root sev-, which loosely translates to the act of serving or sacrificing for (Virdee 2005).

Gurmit Virdee divides the Sanskrit sevā into separate theological and secular etymological roots; the meanings of these distinct roots combine to denote acts of service that are performed out of love. Thus, Virdee characterises sevā as a ‘labour of love’, devoted by those seeking to pass forward this internalised love to others in society. Markus Schlecker (2013) defines these sevā-led actions as a form of dedication – the engagement of sevā becomes a mechanism of social support sustained by the dedication of individuals, such as at the Golden Temple (Figure 11). In addition, serving others through sevā is ultimately a selfless endeavour; the sacrifice of time, energy or material wealth involved, as actions of self-loss, attempts to externalise individually held principles of dedication and service for the benefit of others. The removal of one’s own ego from the equation of service allows sevā to become a material transfer solely of goodwill and the intention to better the lives of others. On balance, partaking in sevā may be challenging for parts of society that require the support which service provides. Nevertheless, Chakraborty (2022) positions sevā-informed actions in this manner as a ‘socially sanctioned’ practice, perhaps positioning it as a duty – one which may augment both individual character and communal wellbeing. Sevā is foremost a human act of loving sacrifice: a non-reciprocal and devotional burden undertaken with happiness.

Sevā as a principle is theologically rooted in South Asian religious scripture, referred to repeatedly in Sikh and Hindu text passages. Both sets of scripture highlight sevā as an instrumental practice which is necessary for those seeking to reach heaven or paradise. On the one hand, Sikh texts such as the Guru Granth Sahib outline the notion of selflessness as an important part of religious life –

25 03 / सेवा : theology + ecology

03 / सेवा : theology + ecology

sevā / the architecture of serving others 26

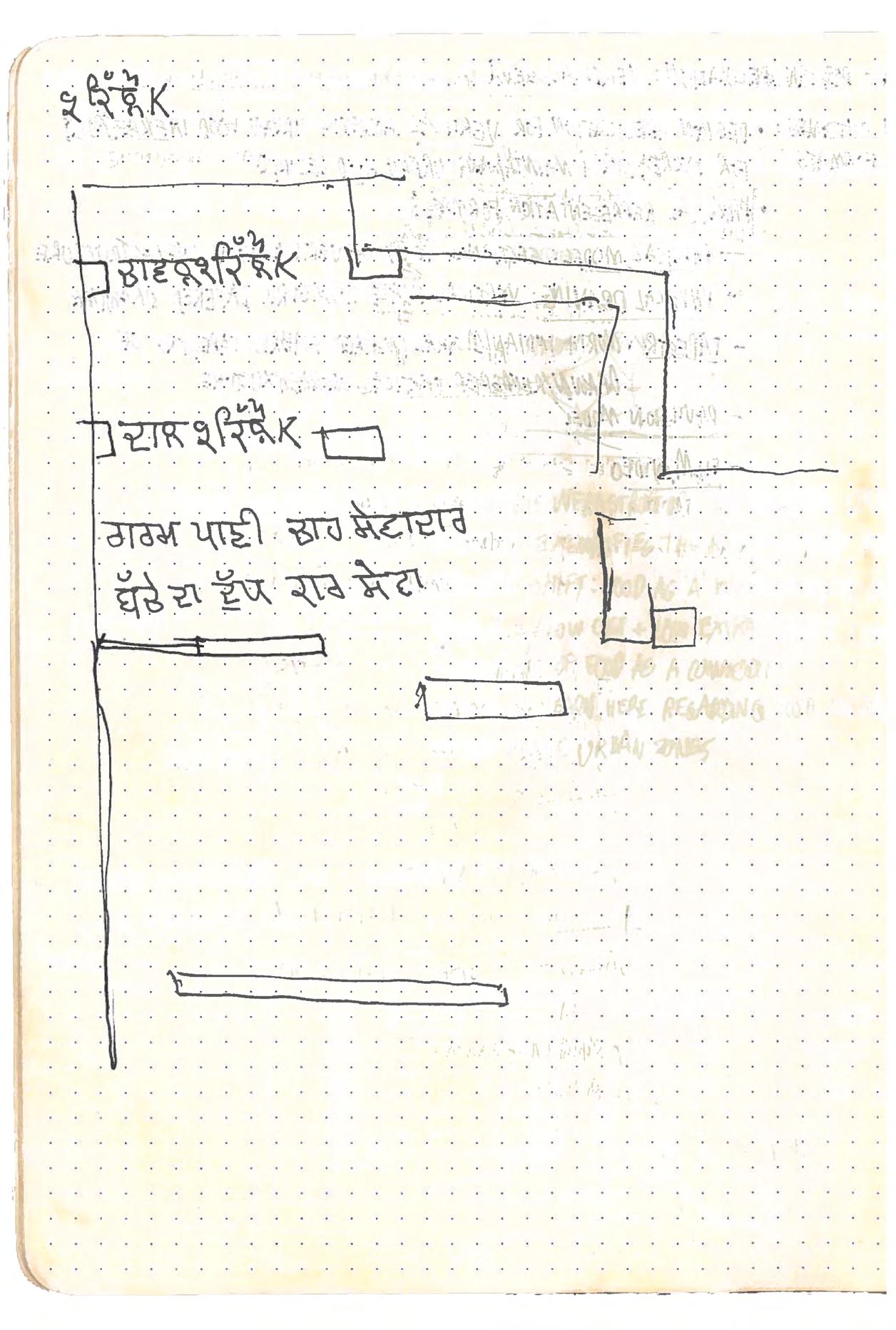

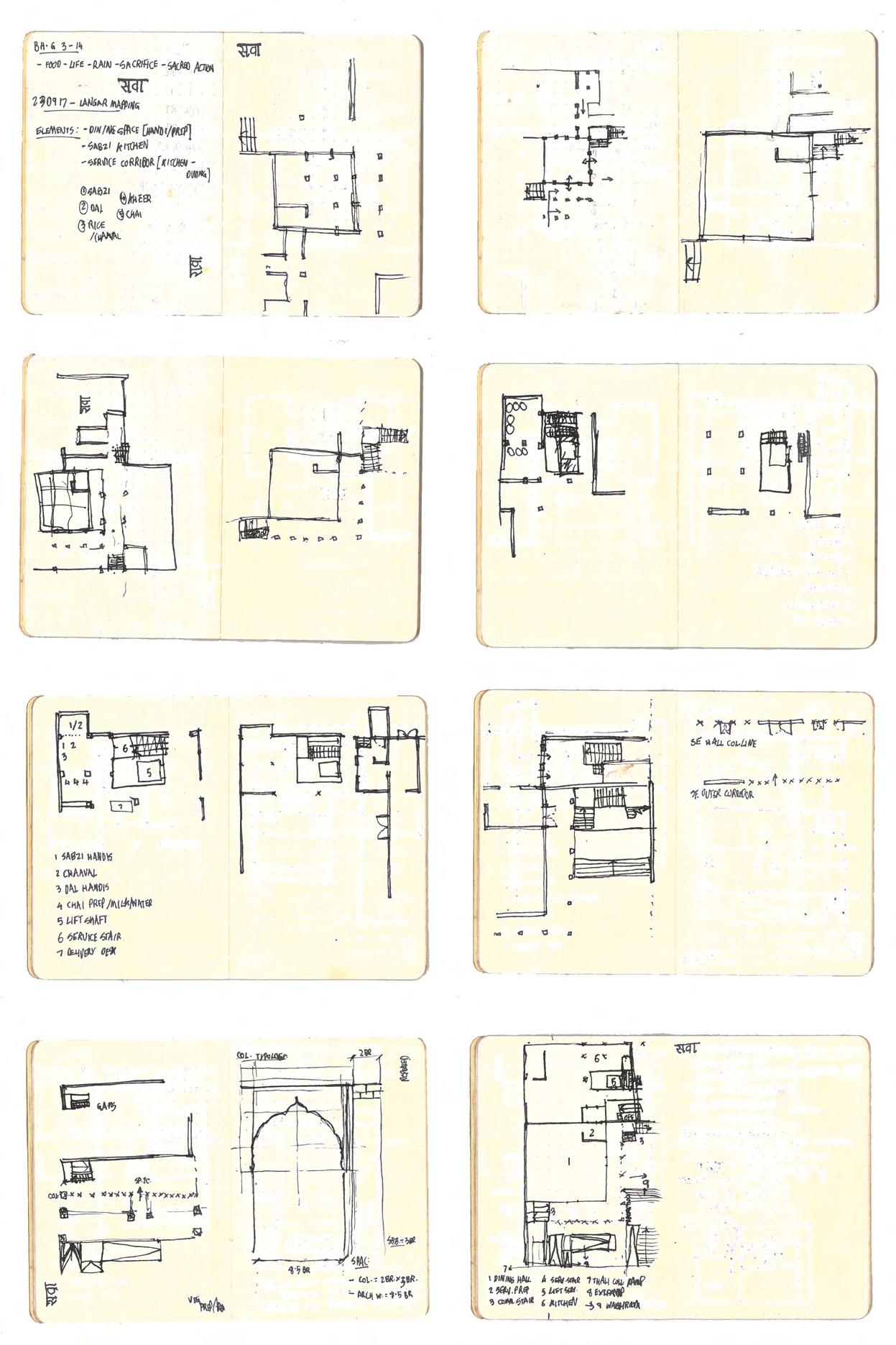

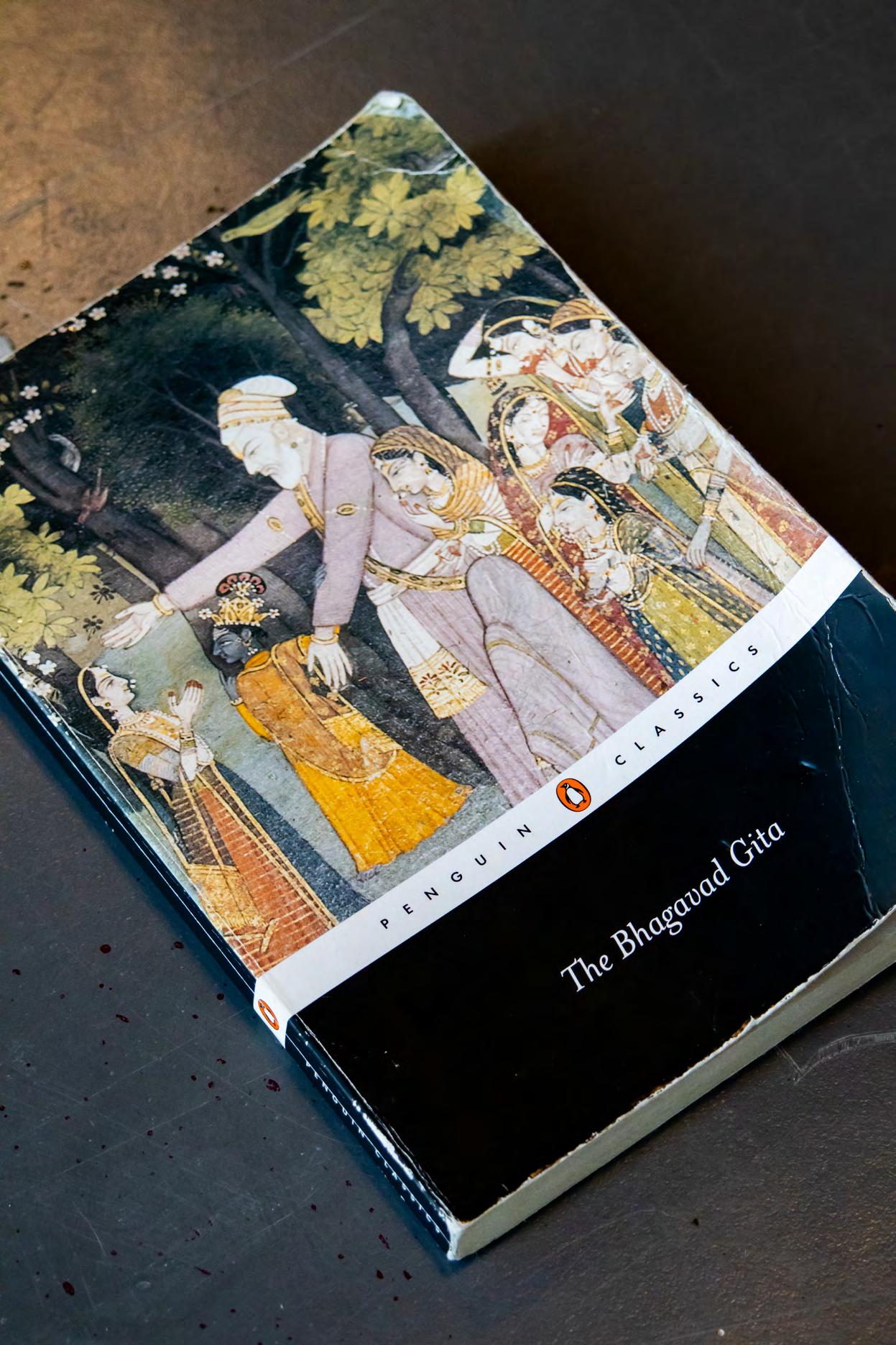

Figure 12 - author’s personal copy of the Bhagavad Gita

‘through selfless service, eternal peace is achieved’ (M. Singh 2008). On the other hand, the Hindu Bhagavad Gita (Figure 12) portrays service as prudent and holy action for the benefit of others; ‘let the wise man work unselfishly for the good of all the world’ (Bhaktivedanta 1972). Thus, religious views on sevā generally take an optimistic stance on serving others, stipulating the direct relationship between serving others and receiving eternal grace and reward. Theology, at this point, expresses sevā as the material bridge between mankind and its creator(s); it perhaps becomes clear that sacrificial action driven by sevā principles is a powerful force in bringing religious believers closer to the entity which they worship. Sevā allows the attainment of ‘supreme good’ in this manner, in stark contrast to only ‘selfish goods’ attainable on earth; selfless service is symbolic of a vessel via which believers may cross the threshold between mortal life and eternal, spiritual harmony. Purely religious interpretation in this manner, however, is limited in assessing the social applications of sevā.

27 03 / सेवा : theology + ecology

sevā / the architecture of serving others 28

Figure 13 - Sri Harmandir Sahib langar hall

03.2 / सेवा X ecology

South Asian theological commentaries on sevā attempt to relate selfless action and giving to the idea of maintaining socio-ecological harmony, where the altruistic nature of sevā-driven actions is seen as integral to wider environmental systems (Putra 2021). For instance, the Bhagavad Gita states that ‘all [selfless] actions take place in time by the interweaving of the forces of Nature’ (Bhaktivedanta 1972); this verse portrays the supposed interlinking of moral action and environmental phenomena. Actions constituting sevā perhaps build up a form of moral economy (Zavos 2015), one which underpins and reciprocally impacts the wider natural forces at play in the world. Often performed as acts of holy worship, serving others through philanthropic giving becomes a regulator for ecological systems which seemingly rely upon ritual bonds between humans and divinity. This idea is reinforced by Sikh scripture describing langar – sevā-led acts of abundant giving in the langar hall (Figure 13) are inevitably reciprocated by powers ‘transcendent’ of human society, rippling through surrounding natural ecology (N. G. K. Singh 2023). Furthermore, the Guru Granth Sahib illustrates a perhaps inextricable accountability between selfless human compassion and the harmonious operation of universal ecologies through references to ‘environmental ethics’ and morality (M. Singh 2008). The multifaceted act of serving others, therefore, is tied to socio-ecological endeavours aiming to establish a sense of harmony between and within Creator(s) and creation (Baig 2021). Practising sevā is believers’ opportunity to externally proliferate internalised compassion of others; the physical environment, as well as surrounding members of society, stand to benefit from this altruism. On balance, there may be difficulty for some to perceive sevā solely within this conceptual framework.

Eastern approaches further position sevā – specifically in the culinary context of food service – as an intermediary between human and non-human ecologies. This perhaps is most clearly demonstrated in the third chapter of the Bhagavad Gita: ‘Food is the life of all beings, and all food comes from rain above.

29 03 / सेवा : theology + ecology

Sacrifice brings the rain from heaven, and sacrifice is sacred action’ (Bhaktivedanta 1972). This verse defines sevā (‘sacrifice’) as part of a broader consequential system where human actions function interdependently with meteorological processes involved in climate and nutrition. A vivid and integrated cycle is illustrated here between the necessity of human sacrifices and the resulting nourishment which non-human ecologies provide. Hindu scripture effectively represents human sevā as an integral variable within a global socio-ecological model of community food security; philanthropic acts of serving others and ritual sacrifice are the perpetuating force that empowers natural systems and the agricultural production of food resources. Filippo Osella (2018) aptly labels this notion the ‘productive power of giving’, drawing parallels between the role of charitable service in human economies and the believed ecological ‘multiplier effect’ that sevāled sacrifices induce in terms of natural resource and yield. Hence, selfless action through sevā essentially mediates both human and non-human ecological cycles, securing food as a critical, communal amenity for stability. Sevā, of course, may act as one of multiple factors in modern, urban food provision.

From a decolonial lens, the eastern positionality of sevā as a foundation for socio-cultural stability questions established western narratives of social harmony. Katy Gardner (2018) describes a prioritisation of capital which Christian or western doctrines on philanthropy tend to have; charitable giving and aiding communal development is often transactional in nature, where there may be a desired accumulation of socio-economic credit in the process of serving others. Sevā, on the other hand, demonstrably opposes any expectation of material compensation for selfless actions. Carey Watt (2005) highlights a stark contrast between the operation of service in western and eastern spheres; whilst neoliberal and modernist forces attempt to sow economic dependencies through cross-regional philanthropy, sevā-led volunteerism on a local scale maintains existing, ritual practices of giving and social support.

Osella (2018) reiterates this aim of sevā – although post-colonial national politics in South Asia (particularly in post-partition India) ascribe corporate value to community development, ingrained

sevā / the architecture of serving others 30

and ritualised cultural practices of serving others are what provide community and resource stability for populations. Sevā and similar eastern cultural systems offer a novel perspective on community support, suggesting the existence of alternatives to ‘hegemonic’ practices of governance and policy (Gardner 2012). Annette Weiner (1992) echoes this sentiment of sevā, highlighting the way in which its systemic opposition to western approaches allows a critique of ‘neoliberal imperative[s] of self-help’ that dominate community organisation and discourage selfless compassion.

Sevā, nonetheless, does face ideological challenges due to its unfamiliarity as a conceptual practice for large sects of the global population.

It perhaps becomes clear at this point that sevā has the potential to be applied as a local and communal tool: one that collectively deconstructs existing narratives of social support and critiques contemporary systems of care (Sohi, Singh, and Bopanna 2018). Sevā differs from larger political systems in its approach to socioeconomic support – organised volunteerism through sevā is initiated from the bottom-up, with efforts to serve others driven by local communities and cultural practices (Schlecker and Fleisher 2013). On the other hand, Schlecker illustrates governmental authorities that are operationally limited in the face of local action, highlighting that policy and finance alone cannot sustain community structures of welfare. Chakraborty (2022) confirms the strengths of bottom-up sevā practices in both establishing and consolidating community; ritualised, communal actions taken to support the welfare of others are inherently beneficial to all. Advocates of sevā-backed social support emphasise the efficacy of group volunteerism, particularly in establishing the community bonds which then perpetuate ritual selfless service. Khushbeen Sohi (et al. 2018) exemplifies this concept of participatory and communal volunteerism through analysis of Sikh practices of langar – it perhaps becomes quite apparent that strong socio-cultural wellbeing is rooted within the ritual participation of the community itself, and not in routine fiscal contributions made by corporate or political players in the name of social support , even where visitors seek to gain personal ‘spiritual advantage’ (Weiner 1992). It is important to recognise, however, that a combined approach of top-down and bottom-up strategy is most appropriate in structural change.

31 03 / सेवा : theology + ecology

sevā / the architecture of serving others 32

Figure 14 - vegetable preparation at the Golden Temple

04 / collective सेवा X commensality

04.1 / सेवा X commensality

Ritualised culinary practices informed by sevā form the basis for community bonds at the Golden Temple langar kitchen (A. Pandey et al. 2015). The continuous acts of vegetable preparation (Figure 14), chapatti making, and dal production in the kitchen and service spaces are laced with communal coordination and participatory action (ॐ). Ahmad Zainuri (2021) relates the ritual nature of these community-led processes of culinary production to a sense of empowerment within participants; Sohi further confirms this relationship, linking communal actions and paired social motives to the building of strong public bonds and practice. Engagement in ritualistic practices of food preparation and service tie langar kitchen volunteers into a shared identity and motivation to meet the needs of others. Lisa Berkman (et al. 2000) describes the perpetual nature of this phenomenon – such actions in a context like the langar kitchen may ‘go on to further reinforce social participation’, providing the grounds to expand communality. Community bonds in the langar kitchen evidently sustain the service that it provides to local people (ॐ): from visiting pilgrims assisting chapatti handout to life-long Amritsar residents who have dedicated years to the largescale dal production occurring in the kitchen, selfless volunteerism strengthens the internally ‘shared emotional connections’ that underscore and perpetuate culinary sevā (Sohi, Singh, and Bopanna 2018). In a sense, ritualised sevā practices enable an almost utopian function within the infrastructure; hierarchies of emotionally and physically taxing labour drive commensal cultures in the langar kitchen. Within this idealised model of community, however, it is inevitable that limits appear for its seemingly perpetual nature; particularly, demographic change and alterations in wider ecological systems for resource provision may remain beyond the control of sevā-led society.

Collective sevā-led practices are perhaps the root of functional food security in the community kitchen; these actions jointly consolidate it as an assured food resource for local people. As many as one

33 04 / collective सेवा X commensality

sevā / the architecture of serving others 34

Figure 15 - kitchen volunteer approaching handi

hundred thousand people rely on the langar kitchen for meals on a daily basis (A. Pandey et al. 2015), in the secure knowledge that their nutritional needs will be met. The central reason that such vast amounts of people are able to entrust their nourishment to the langar kitchen may lie in the collection of sacrificial actions that permeate the building and ensure continuous food production and service. There is axiomatically a relationship between the daily sacrifice of sevadars acting to cook, move and serve food items and the security with which users may access resultant langar meals (ॐ). Noman Baig (2021) characterises spaces such as the Golden Temple langar kitchen, which depend on collective philanthropic action and volunteerism, as sites of reparative urbanism. The objective of culinary sevā becomes one of social justice and indiscriminate local food provision – despite collective efforts, external resource donation and state funding are inevitably required. Weiner (1992) thus connects these collective, religiouslysanctioned sevā practices to socio-political change and improving the welfare of urban populations – the multifaceted mission of culinary sevā therefore fulfils both cosmological and resource imperatives, binding collective ritual participation to reliable resource provision. Of course, perpetual dedication in this manner conflicts with practical sustainability, primarily where participants are expected to endure unceasing psychological burdens of service.

Between both kitchen and serving hall, the sacrificial actions of volunteers conglomerate to lay the foundations for commensality within the langar infrastructure (Chakraborty 2022). Kitchen sevadars immerse themselves in the co-cooking and transferal of dals, rice, and kheer from large-scale vessels (Figure 15) to buckets for service (ॐ); this process is highly coordinated and uses the spatial relationship between kitchen and hall within the langar building to facilitate volunteer involvement (ॐ). Volunteerism is quite possibly the core driver for the kitchen’s effective function – philanthropic actions by people through ingredient donations as well as food preparation and vessel movement facilitate the nutrition which is provisioned to kitchen users. Here, sevā mediates

35 04 / collective सेवा X commensality

sevā / the architecture of serving others 36

Figure 16 - ritual seva-led service within the langar hall

the complex bond between urban food production and communal service, through individual and voluntary devotion (Kanwarjeet 2022). Mass, ritual service within the langar hall (Figure 16) involves kitchen users being served in cohorts of more than a hundred at a time, further entrenching commensal practices and cultural commonality between people (A. Pandey et al. 2015). The human role of sevā in contributing to commensality is visually apparent within the langar hall (ॐ): teams of sevadars rapidly divide responsibilities of food service between kitchen and hall, circulating the large space to ensure all users are able to eat the same meal in unison. Embedded, habitual selfless service in the langar hall perpetuates commensality because users are able to undoubtedly place their trust in the food resources available as well as in the people that serve them. It is also pertinent to recognise the contributing role of space planning and design in continuing established commensal practices within this particular community kitchen building. (ॐ).

37 04 / collective सेवा X commensality

sevā / the architecture of serving others 38

Figure 17 - cultural practices of chapatti preparation

04.2 / agency X communal सेवा

Collective sevā and consequent commensality within the Golden Temple may be taken as a microcosm for community structure that is quite unfamiliar to contemporary urban frameworks (Schlecker and Fleisher 2013). Schlecker stipulates on the inward latency of sevā; compassionate practices of serving others, without expectation of reward, perhaps become self-perpetuating societal forces. The way in which the langar hall exploits these forces to relentlessly provide nutrition and food resources may thus be testament to the idea that sevā-led community frameworks internally drive themselves through ritual convictions. Sohi (et al. 2018) relates this collective and ritual service of others at the Golden Temple to the subsequent building of ‘we-feeling’ that underpins and reinforces existing community food infrastructure. The langar hall’s intrinsic treatment of food as a human resource as opposed to a commodity of economic value separates its methodology from capitalist approaches to social support (Weiner 1992). Whilst free-market economies commodify food within exhaustive, financial systems of transfer, sevā-informed approaches remove the element of transaction from community care and nutrition. Sevā at the Golden Temple prescribes a sociocultural structure which circumvents typical barriers of economics and top-down policy; food resources become the focal point (Figure 17) around which cultural practices of serving others and resulting commensal bonds accumulate. This method of social organisation may work to ensure that the participatory actions of the collective also benefit the collective, perhaps opposing unequal systems of support currently operating in neoliberal urban spaces (Rubin, Willis, and Ludwig 2019). Despite this view, it is important to acknowledge that these ‘western’ spaces are not homogenous in community-making approaches: Anna Puigjaner’s ‘kitchenless’ urban resistance (2018), for instance, demonstrates that other models do exist for instigating urban commensality.

39 04 / collective सेवा X commensality

The operation of sevā-backed communality at the Sri Harmandir Sahib langar kitchen demonstrates the potential of collective participatory urbanism in contributing to mechanisms of social support. Nishat Awan (2013) likens the conglomerated actions of individuals to ‘social capital’, stipulating that this forms the basis of bottom-up approaches of urban welfare. Participation in serving others, exemplified at the Golden Temple through culinary practices, builds social capital and strengthens mutual bonds of support through common conviction in ritual practice. Particularly, Teddy Cruz (2023) illustrates situational socio-economic resilience resulting from such sited volunteerism as evidence for the efficacy of civic action and organisation – empathy for others may be used as a political tool to both support others and alter conventional attitudes towards community care. Sohi (et al. 2018) echoes this sentiment: her ethnographic fieldwork revolving around Sikh sevā practices reveals frequent, selfless participation instils a ‘greater appreciation’ for service and community-led infrastructure. At the Golden Temple langar kitchen, an evident sense of ownership, devotion and satisfaction on participants’ faces must be seen to be believed (ॐ) as collective participation fuels the infrastructure and its ability to provide for local people. Mutuality in sevā practices, whilst working to provide for others, ultimately demonstrates the radical power of participation in fortifying shared socio-cultural bonds and expanding structures of communal support. Sevā, however, may face limits in other contexts where established practices do not exist for infrastructure to exploit in the same way – capital-driven organisation in these instances may be prudent in initially understanding resources and accumulation prior to sociocultural application.

Operating at the intersection between ritual practice and socioeconomic care, practising sevā may give people the spatial agency to alter capital-driven systems of resource provision (Cruz and Forman 2023). Volunteerism at the Golden Temple becomes the means by which people may physically express socio-cultural convictions for spatial justice (Zavos 2020). Since ‘social space is intractably political space’ (Awan, Schneider, and Till 2013), sevā

sevā / the architecture of serving others 40

at the langar kitchen manifests as an instrument for people to lobby for bottom-up resource redistribution, through ritual practices embedded within ritual spaces. A continuous trifecta of sociocultural conviction, humanitarian practice and architectural domain enables the Golden Temple community kitchen to exploit selfless service as a method of challenging conventions of urban resource provision. Collective expressions of agency in serving others through spatial participation at the Golden Temple are continually staggering (ॐ). Experience of and participation in this microcosmic system of collective sacrificial action may truly force introspection on the notion of individual agency, and its inextricable relation to communal welfare.

41 04 / collective सेवा X commensality

sevā / the architecture of serving others 42

Figure 18 - basic communal actions of chapatti production

05 / conclusion(s) + speculation(s)

In conclusion, ritually and unconditionally serving others forges community bonds. Sevā lays the foundations for everyday people to participate in spatialising justice from the bottom up, simply through ensuring the basic needs of others are met (Figure 18). Rooting the service of others in aspirations of perpetuating commensality allows sevā, namely at the Golden Temple langar kitchen, to become a method for people to participate in effecting structural change. Sevā, in essence, serves as a socio-cultural tool, available to people seeking ways to improve communal wellbeing and reconfigure mechanisms of social support. Bolstering communal feelings of mutuality and security, sevā’s ability to both impact internal convictions and external resource systems demonstrates its tactility as a viable option for redistributive change (Sohi, Singh, and Bopanna 2018).

Infrastructures founded upon volunteerism and selfless participation such as the Sri Harmandir Sahib community kitchen exemplify that alternative methods of resource provision and community organisation exist. It is perhaps possible to work both within and against currently unequal structures of community welfare, in order to maximise the service of others without consideration of economic or political implications (Weiner 1992). Sevā-informed service at the Golden Temple illustrates that people, en-masse, using their spatial agency to act selflessly may begin to deconstruct the transactional, capital-driven and primarily western ethnographies of social support dominating urban frameworks today (Schlecker and Fleisher 2013). The participatory and autoethnographic method employed in this dissertation to investigate sevā-led society may form an impactful point of departure in continuing critiques of community practices and offering alternative mechanisms of commensality and conviviality (ॐ).

43 05 / conclusion(s) + speculation(s)

Awan, Nishat, Tatjana Schneider, and Jeremy Till. 2013. Spatial Agency: Other Ways of Doing Architecture. Routledge.

Baig, Noman. 2021. ‘The Langar: People’s History of Hunger’. Pakistan Perspectives 26 (2): 5.

Berkman, Lisa F., Thomas Glass, Ian Brissette, and Teresa E. Seeman. 2000. ‘From Social Integration to Health: Durkheim in the New millennium. Adapted from Berkman, L.F., & Glass, T. Social Integration, Social Networks, Social Support and Health. In L. F. Berkman & I. Kawachi, Social Epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; and Brissette, I., Cohen S., Seeman, T. Measuring Social Integration and Social Networks. In S. Cohen, L. Underwood & B. Gottlieb, Social Support Measurements and Intervention. New York: Oxford University Press.’ Social Science & Medicine 51 (6): 843–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/S02779536(00)00065-4.

Bhaktivedanta, A. C. 1972. Bhagavad-Gītā as It Is / [Translated by] A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupāda. Complete ed / with original Sanskrit text, Roman transliteration, English equivalents, Translation and Elaborate purports. New York: Macmillan.

Chakraborty, Radhika Mathrani. 2022. ‘Serving and Sustaining Diasporic Connectivities: Hindu Sindhi Women’s Seva in Hong Kong’. Journal of Sindhi Studies 2 (2): 1–27. https://doi. org/10.1163/26670925-bja10009.

Cruz, Teddy, and Fonna Forman. 2023. Spatializing Justice: Building Blocks. Hatje Cantz Verlag.

Gardner, Katy. 2012. Discordant Development: Global Capitalism and the Struggle for Connection in Bangladesh. Edited by Vered Amit and Jon P. Mitchell. Pluto Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j. ctt183pb8g.

sevā / the architecture of serving others 44 06 / bibliography

Gardner, Katy. 2018. ‘“Our Own Poor”: Transnational Charity, Development Gifts, and the Politics of Suffering in Sylhet and the UK’. Modern Asian Studies 52 (1): 163–85. https://doi.org/10.1017/ S0026749X16000767.

Gelberg, Steven. 2011. ‘THE FADING OF UTOPIA ISKCON IN TRANSITION Subhananda’. 2011. http://www.prabhupada.de/eng/ iskcon-in-transition.html.

Kanwarjeet, Singh, Southcott, Jane, and Lyons, Damien. 2022. ‘Knowledge Meals, Research Relationships, and Postqualitative Offerings: Enacting Langar (a Sikh Tradition of a Shared Meal) as Pedagogy of Doctoral Supervision’. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 21 (April). https://doi. org/10.1177/16094069221097223.

McWilliams, Mark. 2014. Food & Material Culture: Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 2013. Oxford Symposium.

Osella, Filippo. 2018. ‘Charity and Philanthropy in South Asia: An Introduction’. Modern Asian Studies 52 (1): 4–34. https://doi. org/10.1017/S0026749X17000725.

Pandey, A. P., and M. Pandey. 2018. ‘Guru Ka Langar as Parsad Embracing “Sarve Dharm Sambhaw”’. In . https://www. semanticscholar.org/paper/Guru-ka-Langar-as-Parsad-Embracing%22Sarve-Dharm-Pandey-Pandey/57b8cb653d02278d359f3dec67 84297d831b5244.

Pandey, Anshumali, Priyadarshani Singh, Ihm Silvassa, and Ihm Gurdaspur. 2015. ‘Community Participation in Tourism: A Case Study on Golden Temple’. In . https://www.semanticscholar.org/ paper/Community-Participation-in-Tourism%3A-A-Case-Study-onPandey-Singh/56a31896d0bfee31e6934f86d3e7ac883a03ab30.

45 06 / bibliography

Puigjaner, Anna. 2018. ‘Beyond “Labor of Love”’. 2018. https:// www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S071769962018000100007&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en.

Putra, I Wayan Sunampan. 2021. ‘Realisasi Ajaran Teologi Sosial Melalui Tradisi Ngejot Di Masa Pandemi Covid-19’. Sphatika: Jurnal Teologi 12 (2): 159. https://doi.org/10.25078/sp.v12i2.3014.

Rubin, Zach, Don Willis, and Mayana Ludwig. 2019. ‘Measuring Success in Intentional Communities: A Critical Evaluation of Commitment and Longevity Theories’. Sociological Spectrum 39 (3): 181–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/02732173.2019.1645063.

Schlecker, Markus, and Friederike Fleisher. 2013. Ethnographies of Social Support. New York, NY : Palgrave Macmillan. http://archive. org/details/ethnographiesofs0000unse.

SikhiWiki. 2015. ‘Seva - SikhiWiki, Free Sikh Encyclopedia.’ 2015. https://www.sikhiwiki.org/index.php/Seva.

Sikhnet. 2016. ‘The Beauty and Experiences at the Golden Temple’. Sikh Dharma International. 20 July 2016. https://www. sikhdharma.org/beauty-experiences-golden-temple/.

Singh, Manmohan. 2008. Sri Guru Granth Sahib. 1st ed. Amritsar, Punjab.

Singh, Nikky-Guninder Kaur. 2023. Sikh Langar. Routledge Handbooks Online. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003058502-28.

Singh, Pashaura, and Louis E. Fenech. 2014. The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. OUP Oxford.

Sohi, Khushbeen Kaur, Purnima Singh, and Krutika Bopanna. 2018. ‘Ritual Participation, Sense of Community, and Social WellBeing: A Study of Seva in the Sikh Community’. Journal of Religion and Health 57 (6): 2066–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-0170424-y.

sevā / the architecture of serving others 46

Virdee, Gurmit Singh. 2005. ‘Labour of Love: Kar Seva at Darbar Sahib’s Amrit Sarover’. Sikh Formations 1 (1): 13–28. https://doi. org/10.1080/17448720500231409.

Watt, Carey Anthony. 2005. Serving the Nation: Cultures of Service, Association and Citizenship. Oxford University Press. https://doi. org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195668025.001.0001.

Weiner, Annette B. 1992. Inalienable Possessions: The Paradox of Keeping-While Giving. University of California Press. https://www. jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1ppcbw.

Zainuri, Ahmad. 2021. ‘Culinary in Petik Sari Tradition: Meanings and Values along Society Empowerment’. In Prosperity: Journal of Society and Empowerment, 1:15–29. https://doi.org/10.21580/ prosperity.2021.1.1.7843.

Zavos, John. 2015. ‘Small Acts, Big Society: Sewa and Hindu (Nationalist) Identity in Britain’. Ethnic and Racial Studies 38 (2): 243–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2013.858174.

Zavos, John. 2020. ‘The Aura of Chips: Material Engagements and the Production of Everyday Religious Difference in British Asian Street Kitchens’. Sociology of Religion 81 (1): 93–115. https://doi. org/10.1093/socrel/srz032.

47 06 / bibliography

07 / figure list

Figure 01 - Golden Temple / Sri Harmandir Sahib, Amritsar

Figure 02 - Golden Temple / Sri Harmandir Sahib, Amritsar

Figure 03a - author’s personal sketches documenting spatial experience

Figure 03b - partial plan sketch by community kitchen dal chef

Figure 04 - regular service volunteers at the community kitchen

Figure 05 - Sri Harmandir Sahib langar kitchen building

Figure 06 - users entering langar kitchen

Figure 07 - users exiting langar kitchen

Figure 08 - langar service at the community kitchen

Figure 09 - Volunteerism X vegetable preparation outside the langar hall

Figure 10 - Utensil washing voluntary service outside langar hall

Figure 11 - Volunteerism X chapatti making at the Golden Temple

Figure 12 - author’s personal copy of Bhagavad Gita

Figure 13 - Sri Harmandir Sahib langar hall

Figure 14 - vegetable preparation at the Golden Temple

Figure 15 - kitchen volunteer approaching handi

Figure 16 - ritual sevā-led service within the langar hall

Figure 17 - cultural practices of chapatti preparation

Figure 18 - basic communal actions of chapatti production

[all photographs + video content in this document is original and produced by author]

sevā / the architecture of serving others 48

49 07 / figure list

सेवा

सेवा / sevā

सेवा / sevā

सेवा / sevā

सेवा / sevā

सेवा / sevā

सेवा / sevā

सेवा / sevā

सेवा / sevā

सेवा / sevā

सेवा / sevā

सेवा / sevā

सेवा / sevā

सेवा / sevā

सेवा / sevā

harshal gulabchandre tutor / albert brenchat-aguilar date / 20.02.24 module / BARC0134 history + theory of architecture