MAKING THINGS

FINDING USE, MEANING & SATISFACTION IN CRAFTING EVERYDAY OBJECTS

ERIN BOYLE & ROSE PEARLMAN

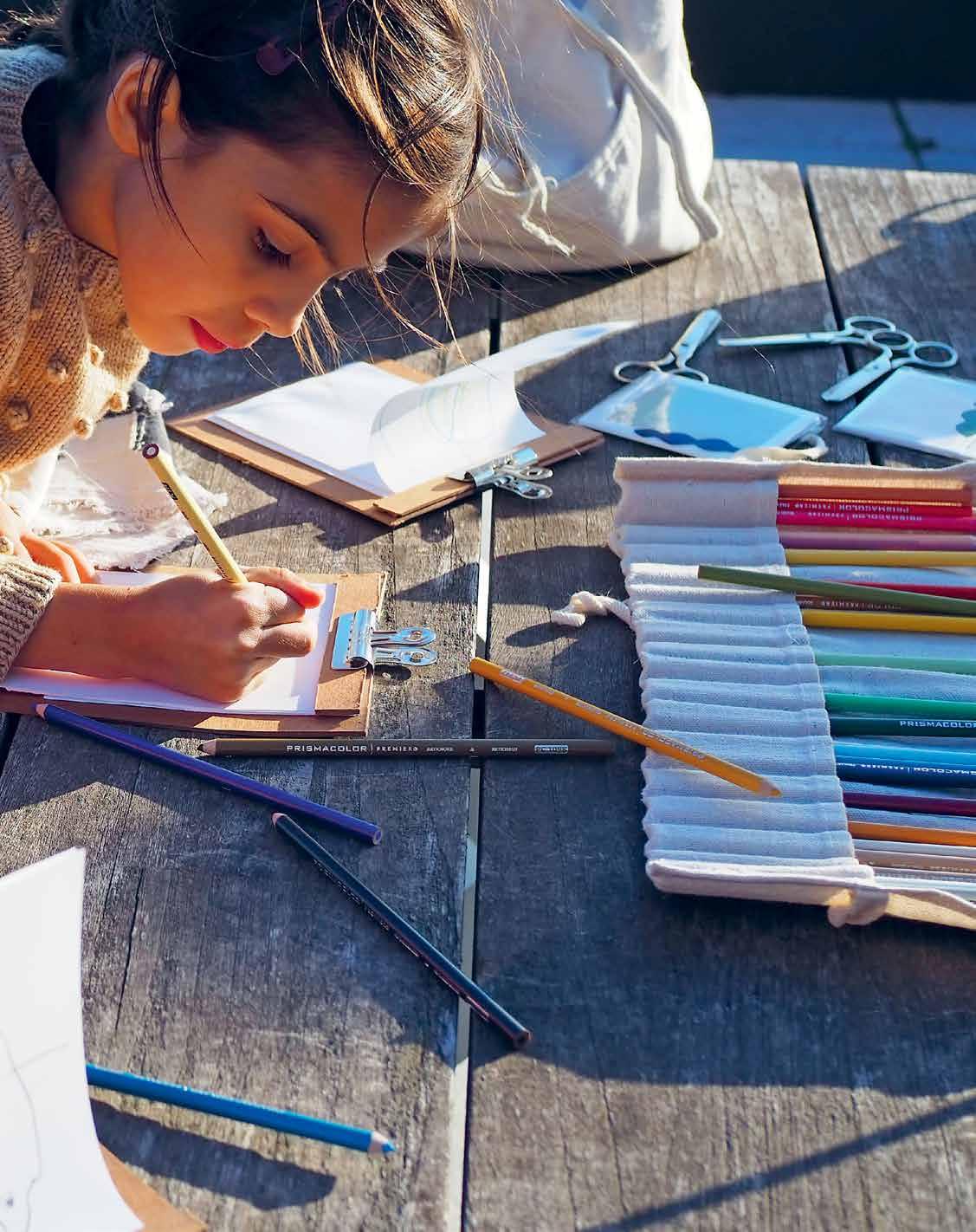

Rose Pearlman and Erin Boyle met in 2018 and immediately struck up a friendship, united by a reverence for everyday objects. Their approach to craft reflects a shared commitment to sustainability and accessibility—as they write in the introduction, “Craft can be exquisite and exacting, the result of formal training and years of practice, but it can also be experimental and messy and not quite perfect.”

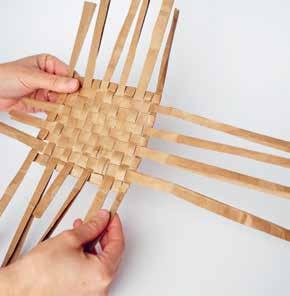

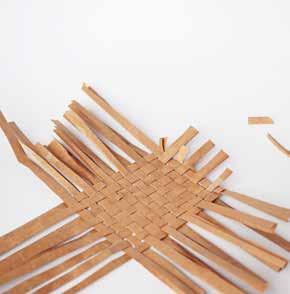

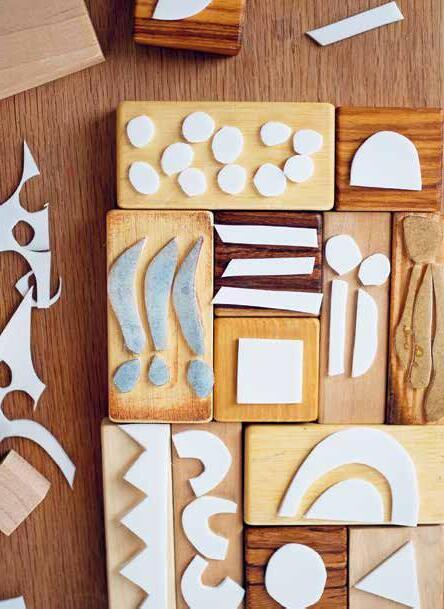

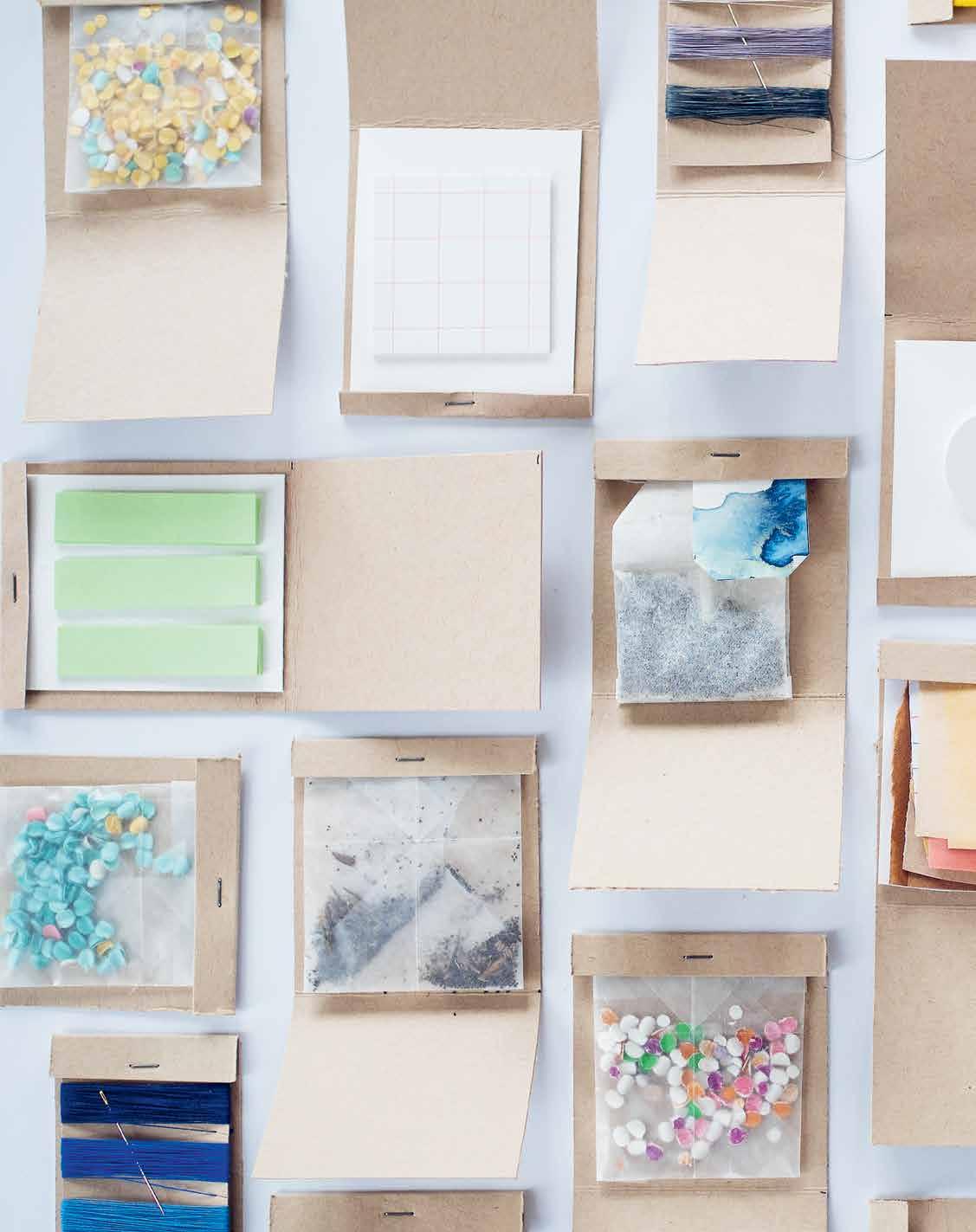

Scouring sidewalks, stoops, thrift stores, and their own recycling bins, the authors repurpose materials to create projects that range from the functional to the fun and even frivolous. Clay incense burners, boxes made from discarded magazines, pom-poms, and sewn cardboard toys are just a few of the over 100 projects included in this book, intended to bring a sense of playfulness and flair to the quotidian. Step-by-step guides make it simple to start and finish each project, while the book’s stunning photographs show how each craft can fit within an organized, thoughtfully curated home.

As Making Things demonstrates, relying on a limited range of supplies and repurposing the same materials can spur our creativity, encouraging us to look at a pile of junk on a stoop and see endless possibility.

“This dreamy book has my head spinning with future project possibilities! I am inspired and ready to create!”

LEANNE FORD, INTERIOR DESIGNER AND CREATOROF

FEEL FREE MAGAZINE“A magnum opus of fun, clever, aesthetically pleasing projects for home and family! Beautifully presented and bound to become a classic.”

—MELANIE FALICK, AUTHOR OF MAKING A LIFE: WORKING BY HAND AND DISCOVERING THE LIFE YOU ARE MEANT TO LIVE

“This is not your ordinary crafting book but a beautiful reminder of all the handy and practical things we can actually make ourselves— everything from pot holders to market totes to storage baskets & caddies—items that will help us organise our homes and simplify our busy lives. I am brimming with ideas after reading this.”

—COURTNEY ADAMO, WRITER“Armed with warmth, creativity, and know-how, Erin and Rose pack a one-two punch: They make me itch to create things, and they deliver on their promise to hand-hold me the whole way. Filled with projects you can do right now—using supplies and scraps you have lying around—this book turns making things into an everyday art form, fueled by Erin and Rose’s unmatched sense of calm and cool.”

—ERICA CERULO, CO-AUTHOR OF WORK WIFE AND CREATOR OF “A THING OR TWO”

“Making Things is a delightful book full of wonderful crafts and home projects. Erin and Rose have such a distinctive style, and I’m so happy to have some insight into their creative process. Their thoughtful approach to materials is accessible and broad, and they have kindly spelled out every step of each project with beautiful photography for those of us who are easily flummoxed!”

—SANDEEP SALTER,

OWNEROF SALTER HOUSE AND PICTURE ROOM

MAKING THINGS

Hardie Grant North America 2912 Telegraph Ave Berkeley, CA 94705 hardiegrantusa.com

Text © 2024 by Erin Boyle and Rose Pearlman

Photographs © 2024 by Erin Boyle and Rose Pearlman

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

Published in the United States by Hardie Grant North America, an imprint of Hardie Grant Publishing Pty Ltd.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-

Publication Data is available upon request.

ISBN: 9781958417270

ISBN (eBook): 9781958417386

Printed in CHINA

Design by Amanda Jane Jones

First Edition

MAKING THINGS

FINDING USE, MEANING & SATISFACTION IN CRAFTING EVERYDAY OBJECTS

ERIN BOYLE & ROSE PEARLMANcontents

introduction 08

tools & supplies 16

01

corral & display

Finger Cording 36

Curtain Tieback 42

Kitchen Hanger 45

Clothes Hanger 45

Paper Roll Hanger 46

All-Purpose Carrier 49

Herb Hanger 50

Wreath/Flower Crown/ Headband 50

Four-String Braid 52

Belt 55

Clip Storage 55

Lanyard 57

Pacifier Clip 57

Clay Vessels 58

Clay Incense Burner 62

Match Strike 62

Pincushion with Magnetic

Bottom 65

Clay Beads 66

Clothespin Knitting Loom 68

Simple String Bag 70

Floral Wire Basket 76

Flower Frog 80

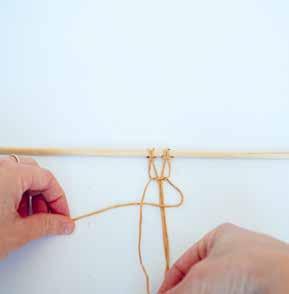

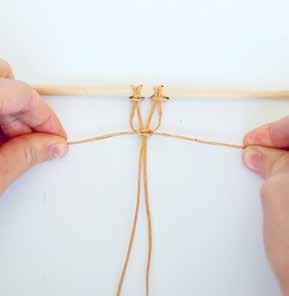

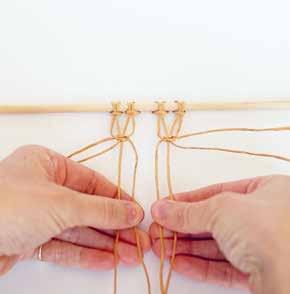

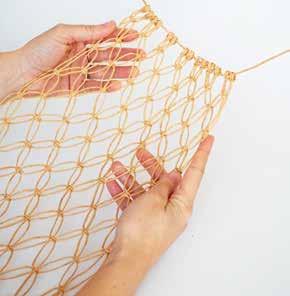

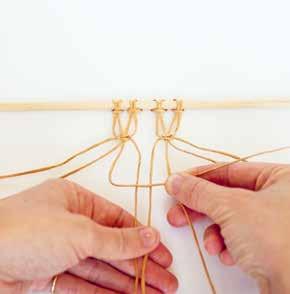

Macramé 82

Cow Hitch 84

Square Knot 85

Floral Wire Macramé Basket 86

Rope Bowls 90

Pinboard 98

02

conceal & hold

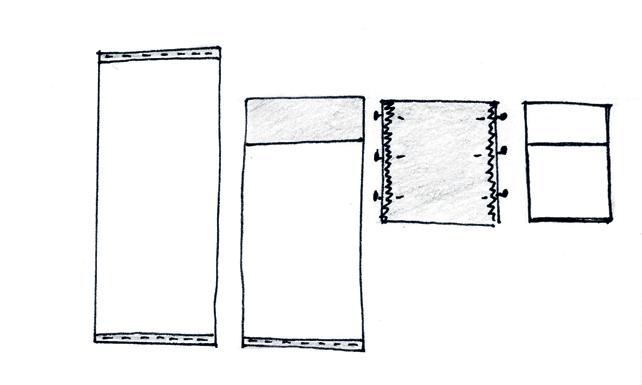

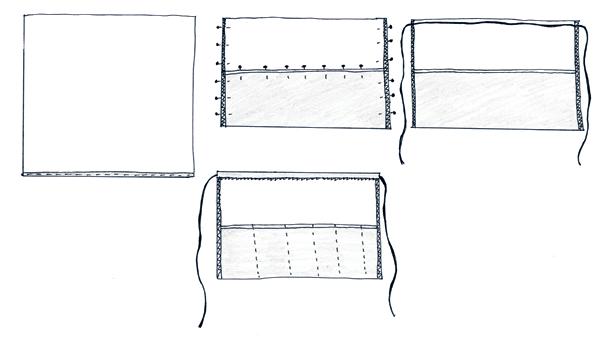

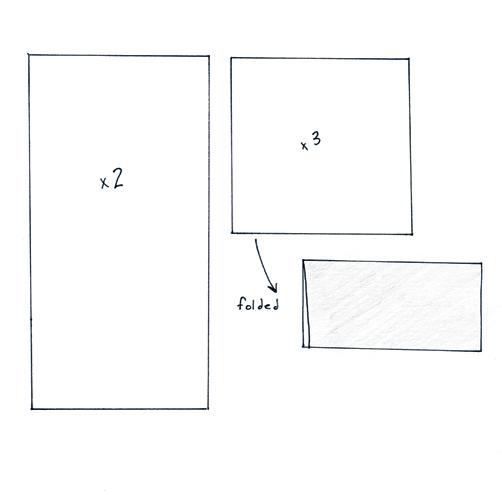

Sewing 104

Drop Cloth Satchels 106

Fold-over Pouches 108

Kit Case 112

Apron Tool Roll 115

Pencil Case 116

Canvas Wall Caddy 120

Tote Bag 124

Papier-mâché Fruit Bank 126

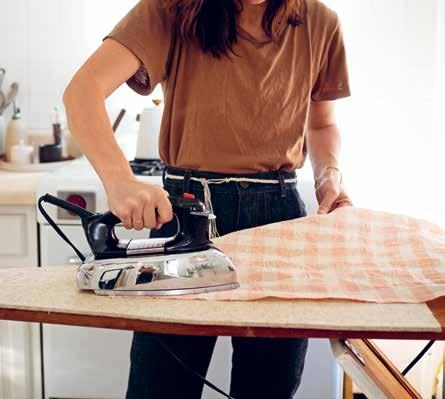

Starching Fabric 130

Canvas Tissue Box with Pockets 135

Paper Boxes 140

Masu Box 143

Magazine Box 146

04

comfort & carry

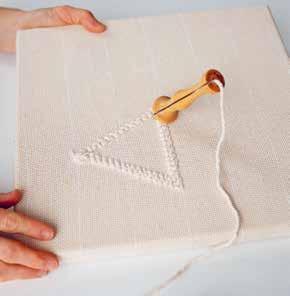

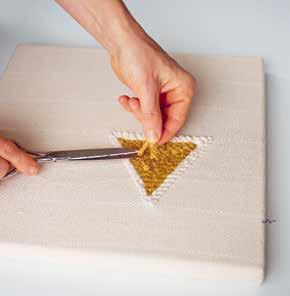

Punch Needle 200

Reversible Butcher’s Twine and Wool Punched Rug 208

Upcycled Fabric Punched Bag 212

Envelope Pillow Covers 214

Upcycled Jersey Punched Pillow 217

Wipes Cover 218

Hanging Lavender Sachet 219

Tea Leaves Dye Bath 220

Upcycled Hankie/Kerchief 222

Rolled Hem 222

Jogak-bo (Patchwork Bojagi) 226

Ssamsol Seams 228

Lampshade 230

Extra Large Lampshade 234

Night-light 236

05 play

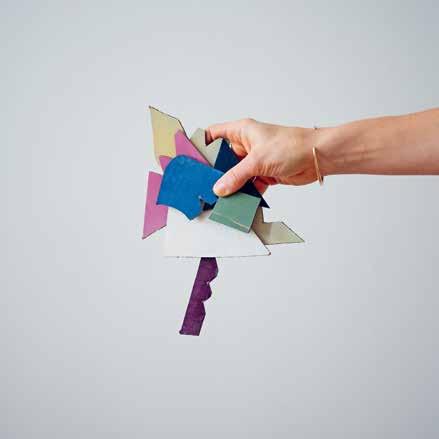

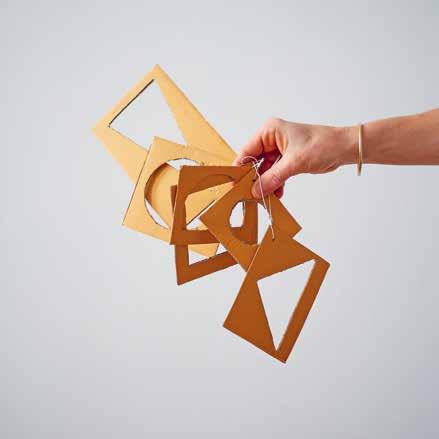

Cardboard Toys and Games 242

Cardboard Magnets 244

Time-telling Practice 244

3-D Cardboard Notch Puzzle 245

Sewing Boards 245

Papier-Mâché Bank 246

Bracelet Loom 247

Geometric Shape Stencils 248

Activity Spinner 248

Nail-painting Practice 249

06

give

Shoe

Weather

Bracelet

Lollipop

introduction

It was learning of each other’s enchantment with a small closet in the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art that first brought me and Rose Pearlman together. I’d made the trek by subway with an infant strapped to my chest to see the neatly appointed shelves of Sara Berman’s closet. Rose had stumbled across them en route to teach a class to schoolchildren visiting the museum.

Tucked in next to a display of Arabella Worsham’s grandiose nineteenth-century West 54th Street dressing room, the re-creation of a twentieth-century West Village studio apartment closet was a master class in order and simplicity. Berman, a Belarusian and Israeli emigrant (and the mother of beloved artist Maira Kalman, who mounted the exhibit with her son, Alex), had made art out of everyday objects. In the red pom-pom affixed to the end of the lightbulb pull cord, in the stacks of her starched and folded white T-shirts, in the potato grater kept on the high shelf and used for making latkes, we saw evidence of Sara’s delight and reverence for objects.

Rose and I met in person for the first time nearly a year after seeing that exhibit. We had discovered each other online. Neither of us had forgotten those perfect shelves or that fluffy red pom-pom. To that first meeting Rose came bearing craft supplies—as she always does—and a punch needle bag she’d made herself. A week later, she taught me how to make a pom-pom

using two clothespins and the cardboard center of a roll of tape.

For the past six years, we’ve delighted in each other’s company and in making things together. I live in a crumbly brownstone apartment with layers of paint and longtime rental quirks. Two miles away, Rose lives in a cookie-cutter rental seventeen floors up. Both of us make these places home in large part through a scrappy pursuit of useful beauty-making. In a moment when quick access to consumer goods is easier than ever, we’ve found use and meaning in a practice of making that provides a tactile and emotional reconnection to our belongings.

materials & supplies

We’ve purposefully pulled from a simple supply closet for this book, hoping to avoid highly specialized tools or materials in favor of those that are easy to come by.

In New York City, a place where most any specialty craft item can be found, we wanted to stick to materials on the shelves of our neighborhood hardware stores. We’re well aware that with a few keystrokes new materials can be sourced and ordered and delivered to our doorsteps, but in using what’s readily available, harvesting elements from what we already have, and rethinking the craft closet as something that’s stocked as much with upcycled materials as craftstore purchases, we’ve found

What you need is likely within easy reach and what you already have can be remade.

inspiration and abundance in constraint.

Relying on a limited range of supplies and repurposing the same few materials and techniques over and again are at the heart of this book. And that’s the message we want to offer readers: what you need is likely within easy reach and what you already have can be remade and given new life.

In his book Fewer, Better Things: The Hidden Wisdom of Objects, Glenn Adamson writes at length about material intelligence, which he describes as “a deep understanding of the material world around us, an ability to read that material environment, and the know-how required to give it new form.” As materials themselves have proliferated, he argues, our distance from understanding them has also grown. We’re hoping this book might be one small entry point for folks

We’ve found that a deeper understanding of materials makes room for thrift & resourcefulness.

we train our eyes to look closer, past the decay and the stains and the holes, we begin to find value in a shape, a material, a texture, a color.

yearning for a different kind of relationship to the materials at our fingertips.

In our own practice of making things, we’ve found that a deeper understanding of materials makes room for thrift and resourcefulness. It’s what enables us to stumble upon a collection of junk at a stoop sale or in a sidewalk free box and instead of seeing trash, to see opportunities.

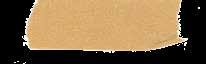

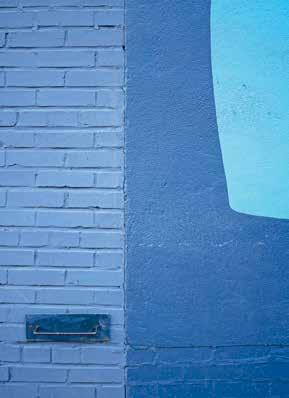

It’s a long stretch between our two apartments, forty-five minutes by foot and without many sensible public transit options. On busy or rainy days the distance has felt like a schlep, but mostly we’ve seen these walks as sources for finding inspiration. Along those city blocks, we pass rows of brownstones, boarded up construction sites, schools, shops, restaurants, and highrises. We pass places of worship, playgrounds, and chain-link fences. Pounding the pavement between our two apartments we’ve come to see the built environment as an object lesson in shapes, texture, and color. It’s not always easy to see beauty in crumbling concrete, but when

In the course of writing this book and putting into words and pictures these projects we’ve come to know by heart, it was important to us also to find new ways of seeing these projects. We wanted to challenge ourselves and our readers to find beauty and utility in materials we might not always remember to value. On our long walks between each other’s apartments, we’re scavengers: spotting the good black plastic garbage bags to turn into twine, the high-quality cardboard neighbors have put in their recycling bins, the flannel shirt someone left hanging on a wrought iron fence. As we rifle through the goodie bags that come home with our elementary schoolers, we train ourselves to glean what’s useful. A novelty keychain might not earn a spot in our permanent collection, but its hardware can be used to make one that does. A craft foam crown brought home from a children’s party might not be cherished, but the materials can be used to make a set of one-of-a-kind block stamps. The nice junk mail catalogs—with the matte pages and good colors—get sorted and saved for future projects. The moth-eaten sweater becomes a felted dust mitt and hot water bottle cover. The night-light with the broken shade can be made anew. The dress, the T-shirt, the old baby carrier become yardage or yarn for our next project.

The imperfections and quirks of the city we call home have found form in our crafts, and in

turn, we’ve come to see our crafts in the city: The fading brick that mimics a weave; the construction cone that’s the same shade of orange as the old Mets T-shirt we cut up to make a woven pouch; the rusted metal siding of old warehouses that mimic the corrugated folds inside a cardboard box. Maybe gritty sidewalk cracks aren’t in abundance near you. Yet there’s poetry and inspiration in the chainlink fence at the baseball field, the painted lines of a parking light, the angled shadows that streetlights cast at the end of a cul-de-sac. Point is, inspiration’s everywhere, even where we least expect it.

finding value

“It’s true that a farm family of the 1930s had to depend on their material intelligence for survival, while today’s city dwellers and office workers can get away with ignoring their physical environment and make a fine living. Maybe this feels like a sort of progress. But basic necessity is only one side of our relationship to materials. There are others, too: pleasure, discovery, inventiveness, and particularly important, responsibility. Our relationship to materials determines much about the way we live on Earth.”

–Glenn AdamsonIn writing this book we’ve asked ourselves how making things changes the way we see the objects in our home. How does the process of weaving a bag or basket or bowl from rope help us to pause and consider these objects from a different vantage point? How can making things—even remarkably simple things—get us to recon-

We’re hopeful our pared-down instructions will offer a comfortable starting place.

sider how everything else in our lives gets made—even those items we might never imagine endeavoring to make ourselves?

We’ve found the answers lie in the making itself. Getting out of our brains and into our bodies—getting lost in the rhythmic meditation of knitting or weaving or tying wire into knots—allows us the time and space to think more critically, to make more creatively, and to consume more thoughtfully.

In her 2020 book Fixation: How to Have Stuff without Breaking the Planet, Sandra Goldmark writes that the mystique of making things by hand is pervasive in American literature. She cites the romanticization of making things in popular children’s literature like the Little House on the Prairie series. And, while she takes care to note that these stories are often “incomplete at best and racist and sexist at worst,” she argues that they did emerge in part from a fundamental truth: Americans of all kinds—Native, African, and European— were makers. She goes on to write, “the challenge for us today is to take these frayed but still extant threads of

myth, and making, and mending in our culture, and weave them into our modern lives.”

In our experience, making things ourselves changes the way we value them. On a planet increasingly filled with the detritus and damage of a consumer culture, we find great value in becoming a maker. If making things engenders even a fraction of reverence for our belongings, for the materials at our fingertips, for our own ability to be resourceful and thrifty and creative, it’s a worthy pursuit.

experience, expertise & mastery

Beyond using simple supplies, we have also deliberately kept our techniques simple. If you are a master sewist or a lifelong knitter, the particulars of technique and method in this book will be familiar, but we’re hopeful that a new application of those skills will still be inspiring. And if you have never picked up a pair of knitting needles or sewn a stitch with thread, we’re hopeful our pared-down instructions will offer a comfortable starting place. Many of the projects in these pages piggyback off one another, building on the same sets of skills and supplies to yield different results.

As any crafter does, we’ve leaned heavily into tradition here. The methodology and techniques shown in these pages are in many cases millennia old. We owe a debt of gratitude to makers the world over who have come before us and who work alongside us. For many of these makers, crafting is the basis of

their lives and livelihoods.

In the writing of this book we spoke with many of our favorite artists and makers about the goals for this book. These folks, who inspire us daily with their creativity and their skill, all agree: mastery is an ongoing process. The most important step is to begin. We hope that this book encourages you to dive right in. Craft can be exquisite and exacting, the result of formal training and years of practice, but it can also be experimental and messy and not quite perfect. We hold master crafters in reverent esteem at the same time that we recognize in ourselves—and in our readers—an ability to craft the world around us, perfection be damned.

measurements & exactitudes

We’ve done our best to give the steps needed to get these projects made successfully, but that comes with the risk of having you think there’s only one way to make them. In our own quirky creative practice we feel free to experiment, to try things on for size, to try one material and then another and see how an idea that started out as one thing might develop into something else.

We confess, we are not the kind of crafters who swatch our fabric before embarking on knitting a bathmat from a threadbare sheet. This means that there have been times when we’ve started and stopped and begun again. We embrace this as part of the process and not something that should be shied away from. What a joy it is to get something right the first time, but through

Our fervent hope is that readers will see the ideas in this book and run with them.

failure we can shift and reshape our craft and our process and come out with something wholly different and surprising even to us. (Even as we sweat and swear.)

This book is filled with crafts we’ve made hundreds of times, but as with any craft that becomes built into the memories of muscles and fingertips, each time we make them we try something slightly different. We discover a new way of working, a different use, a variation in supplies, or dimensions that bring a whole new meaning to the process and product.

This, of course, is the point of making things. Whether it’s as simple as braiding together strands of hardware-store string or shaping a bowl from clay, we develop our own way of knowing those materials. Our fervent hope is that readers will see the ideas in this book and run with them—that these projects will be taken in directions that we haven’t yet thought of or didn’t have the room to describe in a finite number of pages.

In an interview with the podcast On Being’s Krista Tippett, music producer Rick Rubin said:

“Everything we make is the sum total of everything we’ve learned and done . . . our creativity doesn’t come from our ideas. All of everything in us comes from somewhere else. And we get to take those elements, and . . . re-present. We have this information, and we get it, and we get to mix it up and re-form it and re-present it back to the world. And sometimes we re-present it back to the world in a way that no one’s seen it before. And it’s exciting. And someone else can see the thing that we share that hadn’t occurred to them before in that form. And that inspires them to make something—it opens a door in them that allows them to see, ‘Oh, it doesn’t have to be the way I thought it was . . . ’”

Rose herself is a seasoned rug hooker and fiber artist whose deep knowledge of the craft she learned from her mother. Her vibrant geometric designs and use of upcycled fibers are just one example of the kind of inspiration we hope our readers feel empowered to channel. Where Rose takes a left turn with her punch needle, you can take a right. Where she incorporates yarn cut from a tea-dyed T-shirt, you can strip your tattered jersey maternity dress and put that to use instead. It doesn’t have to be the way we think it does.

inspiration

We offer our thanks to the people who have paved the way. In the course of our research for

this book, we folded ourselves into the deep, blue bookshelves of the Tatter Textile Library in Gowanus, Brooklyn. We were drawn over and over to the quirky paperback books of the 1970s stuffed in between shinier crafting tomes. From the vantage point of fifty years later, it’s impossible not to notice that they assume a certain amount of general material understanding. Instructions are often sparse, if present at all. Subject matter is wide-ranging and freewheeling and readers are enthusiastically invited to learn by doing.

The title of our book is a nod to Ann Sayre Wiseman’s 1973 classic, Making Things: The Handbook of Creative Discovery. From her experience as program director at the Boston Children’s Museum visitor’s center, Wiseman filled her paperback book with creative projects kids could craft at home. In the book’s introduction she directly encourages a hands-on approach:

“Learning by experience is profound knowledge, more deeply recorded in the memory than theory or speculation. The most direct, immediate and satisfying path to knowledge is visual and manual experience linked with the urgency of interest.”

Learning by doing connects products with ideas and history. It breeds creative thinking, self-expression, and originality, the confidence to experiment, and the courage to make mistakes, learn control, and perfect skills.

We’re hopeful that fifty years later, we can invite folks to join us in a similar tradition of making things and also of seeing things.

Craft gets denigrated as unserious or unnecessary. When put against the demands of a capitalist system that exploits labor and devalues time, it’s easy to be dismissive of things that take time and care to produce. As working parents with young mouths to feed, and a global pandemic to navigate, and bills to pay, there have been plenty of moments in the past few years when sitting down to make something has felt simply impossible. Would you like me to sit down and make my own twine from a plastic garbage bag before or after I make dinner? Am I to knit my own bath mitt while rinsing the shampoo from a screaming child’s hair or wait until the pre-bedtime temper tantrum? When my boss emails me, shall I leave an OOO reply letting them know I’ll be stripping some cotton sheets and cording my own dog leash for the foreseeable future? It can all sound downright laughable. And yet, we’re simultaneously guilty of spending an enormous amount of time lulled into the hypnotism of the cell phone screen. We might spend hours online shopping for a kitchen organizer that will never, ever bring us joy or satisfaction.

In making things, we find meaning and satisfaction but also solace. This is something crafters have always known: An elderly neighbor crochets to take her mind off her husband’s cancer diagnosis, a child passes a boring car ride making a friendship bracelet, a grandmother folds origami while she’s watching the evening news. There’s comfort in making things separate and apart from any monetary reward—or even the finished product itself. There’s

value in the process itself, value that with any luck is only amplified by the pride and intimacy embedded in the finished object.

May readers of this book be inspired to sit down and make something. The comfort we’ve found in making these simple crafts has been invaluable. In the face of a rising climate crisis, amidst the chaos of family life in a busy city, in between deadlines and in moments of anxiety or dread, we’ve found comfort and respite in turning to our own two hands and making things.

tools & supplies

In the pages that follow we’ll share the humble tools and supplies that make up the bulk of our craft closets and what you’ll need to make the projects in this book. You likely already have many of them, and we’ve done our best to ensure that what might still need to be gathered is easily sourced.

fabric

cotton weave

Cotton plant fiber that is woven rather than knit, resulting in fabric that has structure but no stretch. Muslin, organdy, and poplin are all examples of cotton weaves.

WHERE TO FIND IT: Cotton bedsheets, structured button-up shirts

WHAT TO MAKE WITH IT:

Envelope Pillow Covers 214

Masu Box 143

Patchwork Bojagi 226

Punch needle projects 200

Scrap Fabric Hair Bows 302

Scrunchie 304

Starched Fabric Bunting 298

Starched Fabric Cube 139

Upcycled Hankie/Kerchief 222

canvas

A woven cotton fabric that is very thick and durable. We prefer a lightweight canvas (4–6 oz.) when sewing it with a machine. Cotton canvas, especially in the form of hardware store dropcloths, does not typically come pre-washed; wash and dry before sewing to avoid the material seizing up when washed later.

WHERE TO FIND IT: Hardware store drop cloths, fabric stores, Canvas Etc. (www.canvasetc.com)

WHAT TO MAKE WITH IT:

Apron Tool Roll 115

Canvas Tissue Box with Pockets 135

Canvas Wall Caddy 120

Drop Cloth Satchels 106

Envelope Pillow Covers 214

Fold-over Pouches 108

Kit Case 112

Wipes Cover 218

jersey

Fabric that is knit rather than woven, resulting in material that has “give” or stretch to it. Jersey can be made up of a variety of fibers including cotton, cotton blends, and synthetic materials. It can be upcycled from old clothing and cut into a stretchy, soft yarn. (See page 168 for Upcycling Fabrics into Yarn.)

WHERE TO FIND IT: T-shirts, athletic wear, jersey bedsheets, jersey baby slings and wraps

WHAT TO MAKE WITH IT:

Finger cording projects 36

Kumihimo projects 266

Upcycled Fabric Punched Bag 212

Upcycled Jersey Punched Pillow 217

Woven Potholder 180

knit wool

An animal fiber that’s naturally antibacterial, antimicrobial, warm, and durable. When knit, wool naturally has give and stretch. Upcycling knit wool, whether in the form of a motheaten sweater or a beloved camp blanket shrunk in the washing machine, is a way to extend the life of this valuable fiber. Felt is wool that is matted together through a process of friction, heat, and moisture and is especially great for crafting and kids’ projects because the raw edges won’t fray. Felt can be purchased in yardage or sheets, but knit wool can easily be felted at home. When searching for knit wool for upcycling and making into felt, look for labels mentioning 100% wool, cashmere, merino, alpaca, mohair, llama, vicuña, or angora. Be wary of blends containing synthetic materials as they won’t felt up and do not contain the natural antibacterial properties of 100% wool.

WHERE TO FIND IT: Sweaters, blankets, coats, blazers, shawls

WHAT TO MAKE WITH IT:

Dust Mitt 191

Hot Water Bottle Cozy 192

linen & hemp weave

Linen and hemp weaves are usually heavier and thicker than cotton weaves. Unlike cotton, which tears relatively cleanly, linen and hemp are not a great fit for weaving and punch needle projects because of their thick, frayed edges. But we love both for projects that require a bit more heft and durability.

WHERE TO FIND IT: Structured shirts, pants, dresses, bed linens

WHAT TO MAKE WITH IT:

Envelope Pillow Covers 214

Fold-over Pouches 108

Hanging Lavender Sachet 219

Kit Case 112

Upcycled Hankie/Kerchief 222

monk’s cloth

Woven cotton fabric made specifically for rug hooking and punch needle projects. To ensure you are purchasing the right material, your monk’s cloth should have 10 to 12 holes per inch / 2.5 cm and be purchased only where rug hooking supplies are sold. Monk’s cloth should not be prewashed before using.

WHERE TO FIND IT: The Oxford Company (www.amyoxford.com); The Woolery (www.woolery.com)

WHAT TO MAKE WITH IT:

Punch needle projects 200

paper

Not all paper is interchangeable when making these projects. Because there is such a wide variety of paper types and thicknesses, we’ve divided them into three rough categories to give you an idea of which paper is best suited for which project. Keep in mind that something as common as cardstock can vary in thickness and range from medium weight to heavyweight depending on the manufacturer, and it’s always good to check a paper’s weight before purchasing. Of course, the very best papers are the ones you already have! Think of all the unwanted pages in an old notebook, children’s doodles, grocery lists, old folders, junk mail, letters, magazines, holiday cards, catalogs, calendars, posters, wrapping paper, sketch pads, flyers, and homework sheets. Gently bend a sheet of paper to get a better sense of its weight and how it will crease, tear, and fold. The more personal and colorful the better!

MATERIALS NOTE:

In paper-speak, the thickness of paper is described in pounds—as in the actual weight of a ream of that paper. The smaller the pound measurement, the thinner the paper.

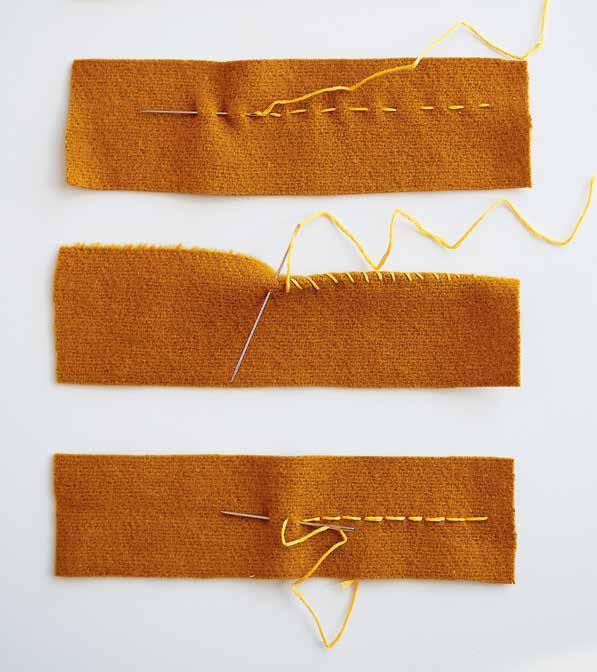

lightweight paper (20–55 pounds)

Paper as thin as newsprint and as thick as copy paper is considered lightweight paper. Tracing paper, some thinner kraft papers, origami paper, and wrapping papers are all also considered lightweight. These papers fold, crease, and tear very easily.

WHERE TO FIND IT : Kids’ easel pages, magazine and catalog pages, newspapers, and circulars

WHAT TO MAKE WITH IT:

Envelopes 296

Magazine Box 146

Masu Box 143

Papier-mâché Fruit Bank 126

medium-weight paper

(50–100 pounds)

Medium-weight paper has a bit of structure but is still easily cut and, with slightly more effort, folded. Many kraft papers, cardstocks, sketch papers, charcoal papers, and some mixed-media papers are medium weight.

WHERE TO FIND: Kids’ drawing papers, construction papers, paper grocery bags, matte catalog covers, posters

WHAT TO MAKE WITH IT:

Masu Box 143

Matchbook Notebook 288

Origami Folder with Closure 306

Paper Bag Woven Fly Swatter 184

heavyweight paper

(100 pounds and up)

Heavyweight paper is thick with lots of structure. It can be easily cut with scissors but is not easily torn. When folding heavyweight paper, a bone folder or the back of a butter knife is helpful to get a

smooth crease. It absorbs a wide range of drawing and painting mediums without tearing, buckling, or warping. Examples include watercolor paper, heavier cardstock, Bristol paper, acrylic paper, and heavier mixed-media papers.

WHERE TO FIND IT: Posters, cover stock

WHAT TO MAKE WITH IT:

Gift tags 295

Origami Folder with Closure 306

Matchbook Notebook 288

parchment paper & wax paper

These food-safe papers have different uses in the kitchen (parchment paper can go in the oven and wax paper can’t), but for our purposes they’re fairly interchangeable. Parchment paper has a more matte finish and wax paper tends to be shinier. Both are typically brown or white in color and semi-transparent.

WHERE TO FIND IT: Grocery stores

WHAT TO MAKE WITH IT:

Accordion Memento Book 284

Envelopes 296

freezer paper

A plastic-coated paper used to wrap meat for freezing. We avoid plastic products as much as possible, but a roll of freezer paper can be used so effectively in simple, low-cost, and small-space friendly printmaking operations that we’ve made an exception.

WHERE TO FIND IT: Grocery stores

WHAT TO MAKE WITH IT:

Freezer Paper Printing 260

cardboard

Cardboard is as versatile as it is common. In the United States alone, many billions of cardboard boxes are used each year. Once you begin to craft with cardboard, you’ll want to hoard the “good stuff.” We like to keep a bag in our craft closets stocked with salvaged, nondescript, unblemished cardboard in a variety of thicknesses for whenever a project strikes.

corrugated

The cardboard mostly associated with shipping boxes and packaging materials. While the thickness can vary greatly, by definition it is a packaging material consisting of a fluted corrugated sheet and one or two flat liner boards. Corrugated cardboard is lightweight and flexible enough to cut through and bend and can be used for a wide range of crafts. Not all corrugated cardboard is created equal, though, and you can easily notice the cardboard that arrives at your door ready to fall apart versus the higher-quality variety used to ship more delicate objects. Safeguard the special stuff!

WHERE TO FIND IT: Recycling bins! There’s never a need to buy new cardboard, just rifle through your (or your neighbor’s) recycling bins and pick out the best pieces.

WHAT TO MAKE WITH IT:

Cardboard Loom 182

Cardboard Toys and Games 242

Envelope and Gift Tag

Templates 295

chipboard

The most substantial and structured among the cardboard varieties and therefore more expensive and difficult to come by. This cardboard takes time and sharp tools (heavy-duty scissors or a craft knife) to cut, but the durability and strength of this material make it worth the effort.

WHERE TO FIND IT: The cardboard backing of drawing and watercolor pads, mat boards

WHAT TO MAKE WITH IT:

Accordion Memento Book 284

Cardboard Toys and Games 242 (especially Cardboard Clock, Weather Board)

Tear-off Scrap Paper Pad 292

paperboard

A single-layer cardboard. Paperboard is easily cut with sharp scissors and can double for medium- to heavyweight paper.

WHERE TO FIND IT: Cereal boxes, toilet paper rolls, and boxed grocery items

WHAT TO MAKE WITH IT:

Cardboard Loom 182

Cardboard Toys and Games 242 (especially Lollipop Lips and Mustaches, Activity Spinners, Binoculars)

Envelope and Gift Tag

Templates 295

Origami Folder with Closure 306

rope, string, thread & yarn

rope

Strong, thick cord made by twisting or braiding fiber strands together. Most commonly made of cotton, jute, and/or synthetic material. A wide variety of cotton rope can be used for these projects, but we like using 100% cotton rope in the 3/16-inch / 5.6 mm size—standard for most clotheslines. If you’re someone who wants to avoid synthetic materials, know that the rope stocked in hardware stores and sold as clothesline often comes with a reinforced nylon core. (Though we tend to avoid it, this heftier rope can be useful in applications like the Jump Rope, page 264, where a bit of added weight is helpful.) Beware of anything labeled cord sash. It can look like cotton clothesline at first glance, but it’s a much stiffer cord that will be very difficult to work around your fingers.

WHERE TO FIND IT: Hardware stores; Knot & Rope Supply (www.knotandrope.com); Ganxxett (www.ganxxet.com)

WHAT TO MAKE WITH IT: Finger cording projects 36 Kumihimo Rope Dog Toy 277 Rope Bowls 90

elastic cord

Composed of elastic and used for its ability to stretch. We generally use 1 mm round elastic cord sold in spools. Elastic also comes in the form of thick, wide, woven lengths commonly used and concealed inside garments.

WHERE TO FIND IT: Craft and sewing supply stores; Mandala Crafts (www.mandalacraftsinc.com)

WHAT TO MAKE WITH IT:

Accordion Memento Book 284 Origami Folder with Closure 306 Scrunchie 304

paper-wrapped

floral wire

Also called bind wire, paperwrapped wire is most commonly used in gardening or floristry and comes in a range of colors and thicknesses. We prefer the finer 26-gauge wire for most projects in this book.

WHERE TO FIND IT: Craft and floral supply stores

WHAT TO MAKE WITH IT:

Floral Wire Basket 76

Floral Wire Macramé Basket 86

Flower Frog 80

string, twine & cord

Common, economical, and versatile, string, twine, and cord are all created when thinner threads are twisted together. Twine and cord are generally understood to be thicker and stronger than string, but the three terms are often used interchangeably. They can be made from a variety of fibers and fiber blends such as cotton, jute, hemp, nylon, and other synthetic materials. For this book we used 24-ply cotton butcher’s twine, 3-ply jute twine,

and 1 mm hemp cord or twine (both unrefined and polished). For the Kumihimo Dog Leash project we found that a 4 mm single-strand cord works best. Remember, in most cases with these crafts, you can substitute the suggested materials with whatever you have on hand, including upcycled T-shirt yarn!

WHERE TO FIND IT: Cotton butcher’s twine and jute twine are both commonly found in hardware stores, while hemp cord and twine are more often found in craft stores. You can find 4 mm single-strand rope online at Knot & Rope Supply (www.knotandrope.com) and Ganxxett (www. ganxxet.com).

WHAT TO MAKE WITH IT:

Reversible Butcher’s Twine and Wool Punched Rug 208

Four-String Braid 52

Knit Cotton String Potholder 164

Knotted Jute Trivet 186

Kumihimo Corded Dog Leash 270

Simple String Bag 70

Upcycled Woven Pouch on a Cardboard Loom 254

twill tape

A flat woven tape used most commonly in finishing projects and as decoration. We like using 100% cotton heavyweight twill tape in the ⅜-inch / 9.5 mm size because it holds its shape without curling and holds up well to frequent use.

WHERE TO FIND IT: Sewing and craft supply stores; www.twilltape.com

WHAT TO MAKE WITH IT:

Kit Case 112

Pencil Case 116

thread

A fine, long strand of cotton, nylon, polyester, or other fiber. Most commonly used in sewing.

WHERE TO FIND IT: A diligent upcycler can harvest thread from old denim and other clothing, but we typically head to our local sewing supply or craft store to re-up our supply.

WHAT TO MAKE WITH IT:

Patchwork Bojagi 226

Rope Bowls 90

Upcycled Hankie/Kerchief 222

yarn

Spun and twisted fibers used for weaving, knitting, or crochet. It’s often used to make clothing, accessories, and soft goods. Yarn comes in a wide variety of fibers, including wool, cotton, and synthetic materials; it varies in size, thickness, and weight. For many projects in this book, we recommend making your own yarn out of upcycled clothing and fabric. For the Clothespin Loom Knit Hat, we suggest buying traditional bulky or super bulky yarn, and for the Scout Scarf, we recommend a lighter worsted-weight yarn.

WHERE TO FIND IT: Upcycled clothing; sewing and knitting supply shops

WHAT TO MAKE WITH IT:

Bulky Yarn Winter Hat 193

Pom-poms 300

Scout Scarf 194

rug yarn

Pre-boiled, 100% wool yarn made specifically for punch needle rug hooking. It’s durable and colorfast and comes in a large selection of colors and hues. This yarn usually comes in a bulky weight (perfectly suited for a punch needle rug) and is heirloom quality to ensure your rugs will last for years and years to come. We recommend Seal Harbor Rug Yarn, known for its expansive color options and exceptional quality.

WHERE TO FIND IT: Rug-making specialty shops like Seal Harbor Rug Yarn (www.sealharborrug.com)

WHAT TO MAKE WITH IT: Punch needle projects 200

tools

ALLIGATOR CLIP: A simple hinge clip commonly associated with hair accessories. We like the 2-inch / 5 cm ones for making small hair bows, but feel free to supersize the clip and the bow itself if desired.

ANNEALED WIRE: A flexible strong wire easily found at your local hardware store. We use it for the night-light project and prefer a 19-gauge wire for a sturdy hold with a still-delicate appearance.

AWL: A sharp needle-like tool with a handle that can pierce everything from paper to fabric and leather. An awl is useful because it can punch where traditional hole-punching tools cannot reach. The hole it pierces is generally small, and a protective craft mat or thick cardboard needs to be laid underneath to protect your work surface.

BULLDOG CLIP: A metal fastener with a spring clip that is most widely used for temporarily binding sheets of paper. We love these for holding down rolls of drawing paper and holding our Tear-off Scrap Paper Pad together.

BRADS: We use brads—metal stationery fasteners—for making all sorts of cardboard toys and games move, spin, and swing.

CHOPSTICKS: Common takeout restaurant chopsticks can be

sharpened to make knitting needles in a pinch. We also use them as handles on shadow puppets and fly swatters and to turn fabric tubes and poke out the corners of sewing projects.

CLOTHESPINS: Round wooden clothespins without springs are typically used for hanging laundry on a clothesline; however, projects in this book use old-school round clothespins because their open slot can easily be slipped on and off of an embroidery hoop and because their round shape makes pulling loops quick and easy. We also use them for making tassels and pom-poms and keeping our strings tidy when we take projects on the go.

CRAFT FOAM: We’re not huge fans of craft foam (found in craft stores or, even better, scavenged from preschool art projects), but a little bit can go a long way to make crisp, long-lasting stamps.

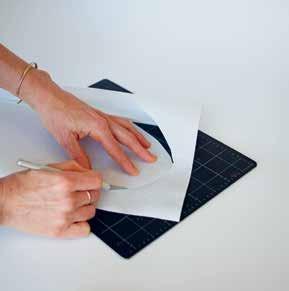

CRAFT KNIFE: A cutting tool with a small sharp blade, often retractable, best used for cutting paper, cardboard, and wood. A craft or hobby knife (X-Acto is the common brand name) has a fine point and pen like handle that is almost indispensable for cutting with precision, especially where scissors won’t reach and for thicker materials like cardboard.

DARNING NEEDLE: Also known as blunt point needles or tapestry needles, these large sewing

needles have a large eye and a rounded point, making them safe for kids to use. Darning needles are great for weaving projects and are also used for finishing techniques in punch needle and knitting techniques.

DOWELS: Wooden dowels come in a range of thickness, most typically from ¼-inch to 1-inch / 0.6 to 2.5 cm diameter, and can be found in both craft and hardware stores. When purchasing from a hardware store, dowels typically are 36 inches / 91 cm or 48 inches / 122 cm long and will need to be cut down to size with a small saw or knife and smoothed out with sandpaper.

EMBROIDERY HOOPS: Round wood frames used to keep fabric taut while creating needlework. Easily found in any craft store. The projects in this book use embroidery hoops in conjunction with clothespins to create a DIY version of a knitting loom. For this purpose, look for the less expensive and less thick varieties often sold in craft stores.

FABRIC CHALK: Used to make temporary lines and marks that act as a guide when cutting and sewing fabric. The chalk can easily be wiped clean once it’s no longer needed.

GLUE: Any craft or white glues can be used for the paper projects in this book. As an alternative to the store-bought variety, we make our own easy paste (page 129).

HOLE PUNCH: A tool to make clean, round holes in paper and other thin materials. Hole punches run the gamut in terms of size and strength. The hole punch used for the projects in this book is a single ⅛-inch / 3 mm, heavy-duty hole punch. It can pierce through everything from paper to cardboard and fabric. A typical handheld hole punch only has a reach of 2 inches / 5 cm. For punching places that are hard to reach with a hole punch, we use an awl.

KEY RINGS: When making our Belt, we often use common key rings as they come in many different sizes and metals. You probably have a few lying around in a junk drawer. If not, try your local hardware store. (If you’d like a round ring without a slotted opening, search online for solid O-rings.)

LOBSTER CLASP: A metal fastener that is held closed by a spring. They come in all sizes, shapes, and materials. They are widely found in the hardware store but can also be easily harvested off something you might already have.

POCKET MULTITOOL: A compact tool that combines several common tools in one unit. A good multitool can take the place of many common larger ones. While not used frequently in this book, a good set of tools (albeit mini and compact) always

comes in handy. Our multitools have pocketknives for whittling down our DIY knitting needles, a flathead screwdriver for pulling out staples, pliers for twisting wire, and a mini saw for trimming down dowels.

PAPER GUM TAPE: A paper tape that sticks to paper and cardboard surfaces when moistened. We like it because it has a wide surface area that’s great for drawing and labeling. Gum tape blends seamlessly into our cardboard projects and can also double to pack and ship boxes. Easily found online or in mail and shipping centers.

PAINTBRUSH: No need to get particular; to make the cardboard games and toys in this book, any medium-size paintbrush will work.

PUNCH NEEDLE: A punch needle is a manual tool used to make rugs with long lengths of yarn and other fiber material. While there are many different punch needle tools available on the market, investing in a well-made one makes all the difference in the ease and enjoyment of

this craft. Rose strongly recommends the Oxford Punch Needle for its efficiency, ergonomic design, and neat stitches. When purchasing, make sure you buy the regular size 10 punch needle. The term “regular” refers to the thick, bulky weight of the fiber used, and size 10 makes a ¼-inch / 6 mm loop or pile. This is also the only size punch needle that works efficiently with repurposed and alternative materials like clothing, bedsheets, and string.

RUBBER BANDS: While any type of rubber band can work to bundle things together, in the Kumihimo Eyeglass Cord project, we use tiny orthodontist bands as a delicate way to tie off the looped ends of our strings.

RULER: We use both a straightedge ruler for drawing and cutting straight lines and a measuring tape for measuring longer lengths.

SANDPAPER: A small square of fine-grit sandpaper is all you need for filing down your DIY knitting needles.

SCISSORS: Ideally, you should have two scissors for crafting: one for fabric and one for paper. While this might sound fussy, scissors will cut a lot better and last a lot longer if you use them for their specific use. A good pair of shears makes a huge difference in their ability to cut clean, sharp lines efficiently.

SEWING NEEDLES: For the average sewing projects found in this book, we recommend a generalpurpose needle.

SEWING PINS: When piecing two or more pieces of fabric together, we recommend simple sewing pins to secure material into place temporarily.

STAMP PADS: For our Block Stamp project, we recommend using water-based ink pads for printing on paper and fabric because water-based ink won’t clog the surface area of your stamp. Ink pads come in a huge selection of colors and sizes (and many can be refilled with ink from the craft store); however, if you’re in a pinch, a washable kids’ marker can be substituted because the water-soluble ink is also stamp-friendly.

STAPLER: To make the Matchbook Notebook project in this book, all you need is a common office supply stapler and staples to fit it.

STAPLE GUN: A heavy-duty stapler used to fasten together thick, porous material like wood stretcher bars or to secure fabric to wood when stretching a frame.

STRETCHER BARS: For punch needle projects, wooden bars with notched ends, called stretcher bars, can easily be assembled to create any size frame needed. Stretcher bar frames are sold in art supply stores in a large range of sizes. While easy to use, they do require a staple gun to secure the joint angles and to stretch with fabric. Look in art supply stores for medium-weight stretcher bars.

SQUEEZE BRUSH PENS: Squeeze brush pens are refillable brushes that store water inside a seethrough barrel. They release water when squeezed with light pressure. They’re perfect for kids and watercolor projects on the go.

TAPE: For most craft purposes, we recommend Japanese washi tape for its assortment of colors and patterns and because it can be removed from surfaces without damage. For sturdier jobs, “painter’s tape” is a masking tape that can also be used on delicate surfaces and removed without damage.

TEMPERA PAINT: We prefer tempera paint for adding color to our cardboard projects because it’s nontoxic and safe for kids. Basic primary colors, plus white, are easily mixed to create many shades. It also dries fast and has a nice matte finish when used on cardboard.

WATER BALLOONS: We use water balloons to help mold our Papier-mâché Fruit Bank and Clay Vessel. Even though latex water balloons will decompose with time, we are also mindful that they can still be harmful to birds and marine life. Please use sparingly and make sure to dispose of them properly.

WATERCOLOR TUBES: When making Travel Watercolor Kits, we like dabbing a little bit of liquid watercolor (sold in tubes)

on paper to make a portable paint palette. Once the colors have dried, a wet paintbrush can activate them just like in a watercolor cake.

WINE CORK: A wine cork can be cut with a pocketknife to make a block stamp handle or used as a handy-dandy way to keep your stitches from falling off your knitting needles.

WOODEN BLOCKS: For our Block Stamps, we recommend using any wooden block you have on hand, even—and especially—if it’s from that long-forgotten Jenga set.

pride intention practicality purpose

In his 1967 book about the art of Japanese packaging, How to Wrap Five Eggs: Traditional Japanese Packaging, Hideyuki Oka writes about the lineage of Japanese packaging as being “driven by two considerations: an aesthetic philosophy that said everything could and should be made beautiful and a value system in which all objects, large or small, expensive or cheap, were of real value.”

The projects in this chapter are suited for display, but they’re also imbued with purpose and practicality—a way to bring a bit of order to the objects we use every day. When we need to reach for a cup measure and there’s not a cabinet to put it in, let’s make the object that holds it also lovely to look at. When we’re looking for a place to store garlic and onions, why not have those items displayed as small works of art themselves? Keys on a hook, spare change in a bowl, scraps of ideas and inspiration; the stuff of life needs a place to live and sometimes, also, a place to be seen.

In our rental apartments, the particulars of which we might not have chosen or we might not prefer, we’ve found a sense of ownership and placemaking in the small, moveable objects we’ve crafted ourselves. Outdated countertops, bathroom medicine cabinets with paint ten layers deep, and closetless rooms are no match for a few hardworking objects made by hand.

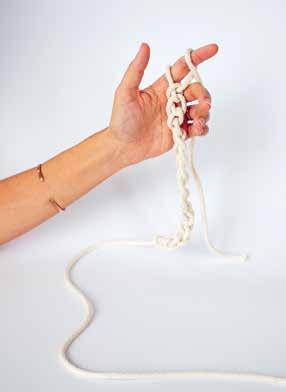

finger cording

If you’re familiar with finger knitting at all, it might be because you’ve witnessed crafty day-campers with yards of rainbow-colored yarn attached to their fingers. For parents of those kids, the craft might be associated with very long, looseknit cords that seem somewhat, dare we say it, lacking in purpose First, we’ll remind ourselves that there’s utility in practicing a craft, regardless of the final product. For kids and adults alike, the repetitive, methodical work of finger knitting is particularly soothing. It’s handwork that can reset the spirit, calm a worried mind, and otherwise occupy anxious hands. Happily for everyone, simple finger-knitting techniques can also be applied to make a number of decidedly practical home objects.

Here we use humble cotton clothesline to make functional, beautiful, finger-knit cords that we put to work in our own lives every single day.

For instructional purposes here, we’ll share the step-by-step process for the most robust cord of the bunch—the one using two fingers and three loops—but simply swapping the number of fingers and loops being used will result in cords of totally different styles. See variations on page 40.

two-finger/three-loop cording technique

1. Start by placing the rope between the pointer finger and middle finger, leaving an 8-inch / 20 cm tail hanging in front of your palm.

2. Working with the long end of the cord, make a figure eight around your pointer and middle fingers as follows: Wrap the cord around your middle finger (clockwise) to the front of your hand, then circle it back between your fingers at a diagonal and wrap counterclockwise around your pointer finger.

3. Complete the figure eight two more times. You should now have three loops on both your middle finger and your pointer finger. Leave the working cord hanging to the back of your hand between your two fingers.

4. Working with the three loops on your pointer finger first, carefully bring the bottom loop over the top two loops and off your finger. You will have two loops remaining on your pointer finger.

5. Repeat for the middle finger by again slipping the bottom loop over the top two loops and off that finger.

6. Continue to cord in this manner, making a figure eight around your two fingers, so you have three loops on each finger before sliding the bottom loop over the top two and off. Wiggling your fingers while you work will help create space. If the tension becomes too tight around your fingers, pull on the bottom loop to create some slack.

7. When you reach your desired length, cut a tail end from your working rope. Thread the cut end through the two remaining loops from the middle finger (from the inside out), releasing the loops from your finger. Then thread the tail end through both loops on the pointer finger (from the inside out) and off your finger. Carefully pull to cinch together.

technique variations

one finger/ two loops

To make this loose cord, wrap rope around your pointer finger twice and pass the bottom loop over the top loop and off the finger. Repeat, adding one wrap and then passing the bottom loop over the top loop until you achieve the desired length.

one finger/ three loops

For a thicker, flatter cord, try this variation. Wrap the rope around your pointer finger three times and pass the bottom loop over the top two loops and off your finger. Repeat, adding one additional loop until you achieve the desired length.

two fingers/ two loops

For a loose cord that’s still substantial enough to tuck hangers or hooks for kitchen utensils, wrap rope in a figure eight around your pointer and middle finger twice. Pass the bottom loop over the top loop and off each finger. Repeat the figure eight and pass the bottom loop over the top on each finger until you reach your desired length.

MATERIALS NOTE: 3/16-inch / 5.6 mm cotton rope is pictured here, but you can use a wide variety of cotton string or rope for these projects.

curtain tieback

A dramatic and chic curtain tieback is a quick and simple cording project with immediate practical use. Start with a long length of rope, approximately 5 ½ yards / 5 m. Leave a 3-inch / 7.6 cm tail between pointer and middle finger and cord for 5 inches / 13 cm using the two-finger/three-loop technique. Bind off the cording by pulling the long remaining length of rope through the four loops at the top. Leave approximately 20 inches / 50 cm of rope uncorded, then begin to cord again (the first corded section and uncorded midsection will be on the palm side of your hand). Cord another 5 inches / 13 cm of rope to match the first side. Bind off the second side of cord, leaving a matching 3-inch / 7.6 cm tail, and cut any extra rope. Try the one-finger three-loop cord for a different look.

TIPS:

For a bit of visual interest, add an oversize bead to the tail end of your rope and tassel out the ends. See page 66 for instructions on making air-dry clay beads yourself.

To create a tasseled fringe on the tail ends, use a darning needle or the sharp point of an open pair of scissors to fray the braided rope ends.

kitchen hanger

These corded hangers are so pretty you don’t need to tuck them away in cabinets. In kitchens short on storage, a vertical hanger creates the perfect spot for tucking in slender S-hooks and hanging kitchen items you reach for regularly, like measuring cups and potholders. Use string to tie on bundles of herbs or flowers for drying.

clothes hanger

Make custom closet organizers with help of finger cording. Whether you’re slipping S-hooks or clothes hangers through the loops of your cord, you can create a vertical hanger that will maximize limited space and offer a beautiful alternative to standard-fare closet organizers. A looser two-finger/two-loop cord will make inserting the hooks or hangers easiest, but any of the cord variations can work here. Cut a long tail and tie a loop on one end. Pass the whole cord through the loop to secure it around the closet rod.

paper roll hanger

If you have rolls of anything in your life that need hanging—toilet paper, paper towels, kraft paper—a corded rope hanger is a sturdy, inexpensive option that’s more interesting than whatever can be found in your average big-box home goods store, not to mention it’s totally customizable.

Start with an 8-inch / 20 cm tail between your middle and pointer fingers. Using any of the cording methods outlined on pages 39–40, work your cord until it’s one and a half times the length of your roll. If you’re hanging an 18-inch / 46 cm roll of kraft paper, for instance, you would cord 27 inches / 69 cm. When you reach your desired length, cut an 8-inch / 20 cm tail and cinch closed. Thread your corded rope through your paper roll and tie a knot. Adjust your cord so that the knot lies inside the tube of paper and only the cord is visible. Hang from any sturdy hook or knob.

TIP:

We’ve loved hanging kraft paper rolls on our steel apartment doors with a heavyduty magnet. If you don’t have a magnetic door, an off-duty wreath hook is another easy way to hang your paper roll without adding permanent hardware.

all-purpose carrier

A corded strap with two end loops is the ultimate low-profile helpmate for schlepping. We’ve used these simple carriers for our picnic blankets, yoga mats, bouquets of farmers’ market flowers, and beach umbrellas. (Our kids have tucked cardboard swords and quivers of cardboard arrows in theirs.) The two-finger/ three-loop cord is our preferred technique for this project because it creates a nice thick shoulder strap.

Begin by leaving a 30-inch / 76 cm tail in the front of your palm. Work your cord for roughly 18 inches / 46 cm. When you reach your desired length, cut a 30-inch / 76 cm tail end from your working rope and cinch closed. You can easily increase or decrease the length of the beginning and ending tails (and the corded section itself) to accommodate schleppers of all sizes. To create the slip-knots, tie 3-inch / 7.6 cm loops on either end. On each side, thread the knot through the loop and pull the rope to create a larger, self-adjusting loop. To use, widen the loops to slip over your blanket, spacing them evenly on either side. Pull the center of the strap upward to secure and tighten the strap closed. To open, pull apart either side of the loop to release the hold.

herb hanger

A one-finger/two-loop cord makes a great flat spot to hang drying flowers or herbs. Secure your bundles of herbs using a whipping knot (page 274) and tie the bundle directly into the finished cord. If you prefer a daintier hanger, use this same technique with the Four-String Braid (tutorial on page 52).

wreath/ flower crown/ headband

If you’re a plant enthusiast, finger cording makes a good base for botanical wreaths and swags. (This general technique can also be used to make a quick and easy flower crown!) Cord up a length of rope using any of the four cording methods and tuck in the stems of dried or fresh flowers or greenery.

four-string braid

It’s a braid, but made even lovelier by incorporating four strands instead of three. Once you get the hang of the technique, it’s no more difficult than standard three-strand braiding. We like to think of this braid as a good gateway craft for someone who thinks they’re not crafty. If your mind is headed back to long summers of your childhood and making friendship bracelets, well, excellent.

This technique results in a delicate yet sturdy braid—perfect for making into belts, lanyards, and daintier versions of the projects we finger-cord with cotton clothesline. We especially love the texture and weight of these braids when made from refined hemp cord. Easy adjustments can be made, creating your desired thickness by working with either four strings, doubling it up to four strands of two (eight strings; like we use here), or even going thicker with four strands of three (twelve strings!) depending on the fiber you are using and the desired use. As always, the material you decide to use is up to you. Feel free to experiment with embroidery floss or upcycled cotton or linen stripped into thin yarn. For something very special, we love the ⅛-inch / 3 mm woven organic cotton tape from Habu Textiles.

SUPPLIES AND TOOLS

+ 1 mm Polished hemp cord

+ Scissors

+ Safety pin (optional)

1. Start by cutting four equal lengths of hemp cord.

2. Fold the four lengths of cord in half to create four loops at one end and eight hanging strings at the other.

3. Pinch all the strands together ¾ inch / 2 cm down from the looped end.

4. Working with four sections, you will begin to braid. Each section contains two strings.

5. Starting at where you are pinching, bring the section on the far right across the middle two sections and pinch it in place.

6. Pass the section on the far left over the nearest section to the right.

7. Continue the same way, passing the far right section over the middle two sections, then crossing the far left section over the one on its right. Take care not to twist the strands while braiding. You can safety-pin the top of the braid to a cushion to stabilize the braid while you work.

8. Continue until you reach your desired length.

9. When finished braiding, tie a simple knot with all the ends together. Trim the ends and you are finished.

MATERIALS NOTE:

Since you’ll need to cut your fiber before beginning to braid, a good rule of thumb is that you’ll need your strands to be roughly one and a half times the length of your desired braid before you start braiding. This will depend somewhat on the particular size and structure of the fiber used and braiding technique applied, but we’ve found it to be a helpful guideline.

belt

With the small addition of two brass O-rings (or key rings), a four-string braid becomes an easy-to-make belt for keeping jeans hitched or dresses cinched. For a 30-inch / 76 cm belt, begin with four 90-inch / 229 cm long strings. Hitch all four loops to the O-rings to provide some nice structure and ensure that the top of your braid begins tightly. At the end of the braid, tie a simple knot and leave a few inches of unbraided string to tassel on the end.

clip storage

A four-string braid tacked into the inside of a cupboard door or closet is the perfect slender spot for clipping things like barrettes, clothespins, or other clips that might otherwise go missing. And if you’re a person who hangs Christmas cards or valentines to display, look no further than a four-string braid and a few clothespins. If you have hair bows that need wrangling, we’ve got you. No special technique needed here, just hang the loop at the top of the braid to a small nail or pushpin, clip, and carry on.

lanyard

Both of us are married to schoolteachers who, like all kinds of workers in service positions, are daily wearers of lanyards for wrangling keys, IDs, and MetroCards. We made these lanyards as an homage to our own beloved essential workers, but we’ve since become so enamored of wearing our keys around our neck, we’re regular wearers of them too.

pacifier clip

If you’ve ever offered a baby a pacifier, you’re familiar with how quickly that sterilized ounce of rubber can be jettisoned overboard and onto the floor. A four-string braid secured to a brass suspender clip makes the perfect foil for a pacifier with an escape plan. For a 6-inch / 15 cm braid, begin with four 18-inch / 46 cm long strings. Tie the end of the braid to the suspender clip and use the loop at the start of the braid to make an easy-on, easy-off hitch to secure the braid to the pacifier loop.

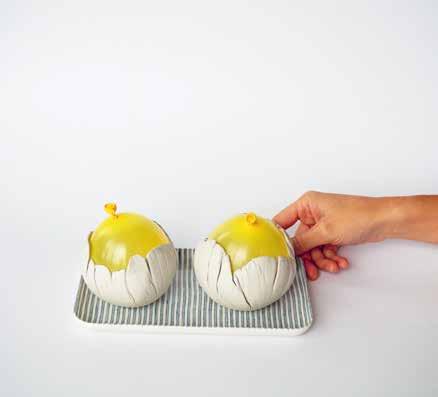

clay vessels

These clever clay catch-all vessels remind us of barnacles, and isn’t that fitting? On a dresser or shelf they can function in a similar way, filtering and safekeeping the good stuff—keys, coins, and bobby pins—that might otherwise get swept away with the tide of household activity. Our solution to all the missing earbuds, vanishing hair ties, and collected acorns of the world are to gather them in small shallow containers, preferably ones that are pretty enough to have on a counter, small enough to fit inside a dresser drawer, and durable enough to survive a toddler. Beyond their role as tiny-thing catchalls, these little vessels will glow beautifully with the addition of a small tealight. If you need a pincushion for any sewing projects, look no further than the pincushion tutorial on page 65.

SUPPLIES AND

+ DAS air-hardening modeling clay

+ Plastic wrap or film (a single sheet can be used multiple times)

+ Biodegradable latex water balloons

+ Rolling pin or wooden dowel (optional)

1. Soften a large handful of DAS clay, working it between two hands and forming into a ball.

2. Flatten the clay ball using the palm of your hands to form a disk. Continue to press the clay outward until the disk is 6–7 inches / 15–18 cm in diameter. You can use a rolling pin if desired but do not roll it out too thin.

3. Blow up a water balloon but not to its maximum capacity; leave at least one-quarter empty.

4. Place the clay disk in the center of a square of plastic wrap big enough to cover the balloon completely. Place the balloon in the center of the clay with the knot side of the balloon facing up.

5. Bring the sides of the plastic wrap up over the balloon and twist the plastic at the end over the balloon. Use your fingers to press the clay upward toward the tied end of the balloon, working around the balloon evenly.

6. Once you are happy with the size of the vessel, gently remove the plastic wrap and place the clay-wrapped balloon somewhere safe to dry. Depending on the sun exposure and the thickness of the clay, it can take a few days to become completely dry. The balloon will naturally deflate over time, so you can gently remove it when the clay becomes solid. Once the balloon is removed, turn your vessel upside-down to let the bottom dry out completely before using.

MATERIALS NOTE:

For this project, we’ve found DAS air-hardening modeling clay the best material for its all natural, nontoxic, biodegradable ingredients, as well as its natural color, texture, and durability. To keep the waste impact of this project low, reuse a single sheet of plastic wrap (or a square from a plastic grocery bag) to make all the vessels.

TIP:

If you’re hoping to go totally plastic free here, you can experiment with alternative materials and get similar, though not identical, results. A bundle of lentils can be gathered into a ball-like shape and used in place of the balloon. (This method worked best for the smallest bowls and it does result in a slightly flatter bottom and the kind of textured interior you might expect from pressing clay around a bundle of lentils. If you’d like a smoother look on the inside, try using flour or another fine-grained pantry staple.) You can also try cloth in place of plastic wrap. A textured linen dish cloth pressed around the clay leaves a pleasing, subtle texture on the exterior of the bowl. Overall, we concede that clear plastic and latex water balloons are the easiest materials to work with in terms of being able to see the shape the clay takes, working it into place, and achieving a rounded vessel shape with a tapered top.

clay incense burner

To turn a clay vessel into an incense burner, you’ll add a clay stand to the bottom.

1. Begin by rolling a lump of clay into a smooth ball the size of a Ping-Pong ball. (The key here is that the clay stand has a bit of heft so that the incense stands upright and the ash falls into the vessel below.)

2. Place the ball on your work surface and press down lightly to flatten out the bottom.

3. Insert a slim skewer (or the end of an incense stick) into the ball, stopping before puncturing the bottom. Widen the hole slightly by rotating the skewer. (The clay will naturally shrink when it dries, so make sure the hole is not too small for your incense sticks.)

4. Place your clay in a dry, warm spot until it hardens.

match strike

The easy addition of an adhesive match strike sticker (found online) to the bottom of your vessel turns it into a sweet little match striker for your bathroom vanity or bedside table.

pincushion with magnetic bottom

If you’re going to be sewing, you’re going to be pinning, so you might as well start with sewing a spot to wrangle your pins. This easy hand-sewn pincushion uses scrap fabric tucked into a clay vessel with a clever magnet hiding in the bottom.

SUPPLIES AND TOOLS

+ Clay Vessel (page 61)

+ Scrap fabric

+ Magnet

+ Pencil or marker

+ Scissors

+ Needle and thread

1. Begin by cutting two circles of fabric: one that’s twice as large as the diameter of your bowl and a second that’s roughly 1 ½ inches / 4 cm in diameter.

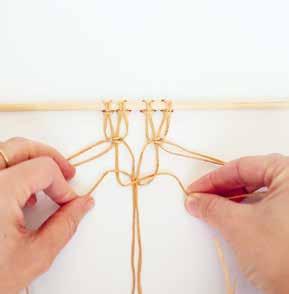

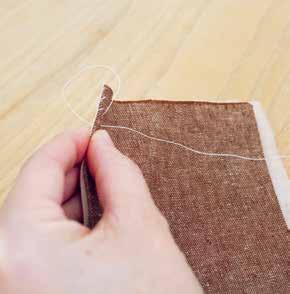

2. Using your needle and thread with a knot tied on one end, create a loose running stitch (page 105) around the outer edge of your larger circle.

3. Carefully cinch the fabric along the thread, drawing the fabric circle into a loose bowl shape.

4. Stuff the interior of the fabric bowl with additional fabric scraps.

5. Cinch the fabric bowl all the way closed and tie a second knot in the thread to keep it shut tight.

6. Whipstitch the smaller circle of scrap fabric over the cinched bottom.

7. Place a strong magnet in the bottom of your vessel and tuck the pincushion into the bowl over the top of the magnet. The magnet will be strong enough to pick up stray sewing pins through the clay.

clay beads

DAS clay dries out relatively quickly, so we like to use up a whole package once we’ve opened it. One of our favorite ways to use up extra clay is by rolling simple clay beads. We’ve used these beads to add to the ends of jump ropes and curtain ties, and they’re also appealing strung up in multiples to wear around your neck or hang as a bit of visual intrigue on a wall.

SUPPLIES AND TOOLS

+ DAS air-hardening modeling clay

+ Bamboo skewer

1. Begin by rolling small balls of clay between your palms.

2. Insert a skewer through the center of the first clay ball. Repeat, stacking all the balls on a skewer with a little space between each one.

3. With the palms of your hands, roll the skewer forward and back on your working surface. The round balls will lengthen outward, taking on a cylinder shape, and the center hole will grow wider.

4. Gently remove the beads and allow to dry.

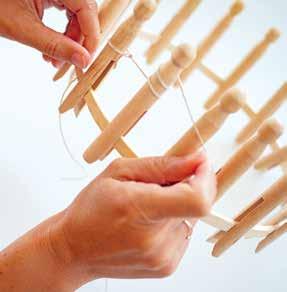

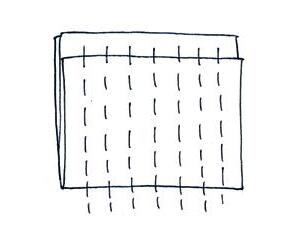

clothespin

knitting loom

This is our homespun answer to round plastic knitting looms. We’ll take knitting in whatever form it comes to us, but knitting on a round loom simplifies the process a bit and can feel more straightforward than needles for folks just getting started. Here you’ll make your own knitting loom from an embroidery hoop and wooden clothespins. Cheap, wooden embroidery hoops tend to work best here because they’re thin enough to accommodate the slit in the wooden clothespins. Look for old-school round wooden clothespins in craft and hardware stores and, of course, online. These looms are delightfully quick to make and can be taken apart and put back together for easy storage and reuse.

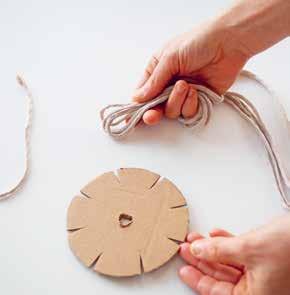

There’s no shortage of things you can make on a knitting loom, but our favorite entry project is a simple, loose-knit string bag made from polished hemp cord. On a knitting loom, the bag knits up quickly, doesn’t require any seaming, and finishes with a simple cinch. Even better, a quick change of material will get you a whole different kind of bag, or even a hat!

simple string bag

This simple string bag is one of the first projects we made together. Over the years, we’ve used these bags to bring home fruit from the farmers’ market, to wrap homemade gifts of bread and baked goods, to offer bottles of wine and whiskey, to cradle mason jars for hanging bouquets of flowers in winter windows, and to store all kinds of alliums for easy, airy access. (We also use them for less glamorous uses like stashing rolls of trash bin liners and dog poop bags.) These bags tend to take the shape of what’s in them, lending them a whimsical, sculptural quality while in use.

SUPPLIES AND TOOLS

+ 9-inch / 23 cm embroidery hoop (use the inner circle, without the tightening screw)

+ 18–20 round wooden clothespins (you might need a few extra if they crack while placing them on the hoop)

+ 1 mm polished hemp cord (roughly 120 yards / 110 m)

INSTRUCTIONS ON PAGE 72

to cast on

1. Evenly space clothespins around the embroidery hoop. Press down firmly, making sure each peg fits tightly.

2. To begin, place a 20-inch / 50 cm tail end of the string through the center of your frame. Wrap this string around the bottom of a peg so it doesn’t get in your way.

3. Begin by wrapping the working string twice around the first peg to the right of the peg where you’ve placed the tail end.

4. Pass the bottom loop over the top loop and off the peg. Repeat with the next peg to the right, looping twice and passing the bottom loop over the top and off the peg. Repeat for all remaining pegs until you are back to the first peg with a single loop on it.

to knit the bag

5. To begin knitting, bring the working string in front of the peg with one loop on it. Pass the bottom loop over the working string and off the peg. Repeat this technique on all the pegs, rotating the loom clockwise to the right. You will need to go around the circle many times to form the bag. Knit in the round for 4–6 inches / 10–15 cm, depending on the size you want your bag. The bag will stretch significantly once off the frame.

to finish the bag

6. Once you reach your desired length, you will begin the process of removing the bag from the loom. Cut the working string, leaving a 12-inch / 30.5 cm tail. Starting on the same peg where you began weaving, carefully slip the first loop off the peg and pass the tail you just cut through the loop. Repeat for all the loops and pegs.

7. Pull the tail end to cinch the bottom of the bag together. Tie a few secure knots through the adjacent loops and weave the tail end into the bag.

8. To make a handle, use the tail end of the string at the start of the bag. Connect it to the opposite side of the bag, weaving it through an available loop (or two). Bring the tail end back over to where it started and secure a knot.

9. Shape your bag and use it to package small gifts and treasures.

drawstring

To draw your bag closed, weave an additional piece of string in and out of the top edge of your bag, going in and out of the open knit weave.

OPTION 1: Weave once around with the two tail ends entering and exiting through the same side. The bag will cinch when you pull the string and push the loops together (see image to the right).

OPTION 2: You can weave once around the perimeter and continue to weave to the opposite side. (You are weaving around the top one and a half times.) One tail end of the string should enter at the opposite side where the tail end exists. When the two strings are pulled out in opposite directions the bag will cinch closed.

MATERIALS NOTE:

A wide variety of fibers can be used to construct these bags, ranging from thin cotton string to bulky yarn.

To make a larger bag, you can use a hoop that is wider or even the perimeter of a large cardboard box. (Indeed, if you don’t have an embroidery hoop handy, you can replace the embroidery hoop with a small corrugated cardboard box from the get-go!)

floral wire basket

With just a simple material switch—swapping paper-wrapped floral wire for the string—a string bag takes on the characteristics of a more structured basket. As you knit the thin wire on the clothespin loom, the stiff material forms a basket. Instead of cinching closed as with string, the wire naturally forms a small round opening where the bottom is pulled taut. We love to use these baskets for crafts and in kitchens since the opening acts as a perfect dispenser for a ball of string. Of course, don’t stop with string! All sorts of small items pair beautifully with these little baskets. Erin hangs one in her kitchen filled with hardneck garlic and another in the bathroom with extra hand soaps. Don’t be afraid to mold the finished basket around a favorite bottle or vase to create a hanging arrangement.

SUPPLIES AND TOOLS

+ 6-inch / 15 cm embroidery hoop (use the inner circle, without the tightening screw)

+ 9 round wooden clothespins

+ 26-gauge paper-wrapped floral wire (3 yards / 2.7 m should be enough for a small bag)

+ Scissors

1. Evenly space the clothespins around the embroidery hoop.

2. Cast on and knit (as in the Simple String Bag instructions, page 72) for 10 to 12 rotations, until the knitting reaches your desired length.

3. Cast off and cinch the bottom of the vessel closed.

4. Weave in any tail ends.

flower frog

These little wire flower frogs are perfect for arranging summer stems without the need for foam, florist tape, or heavy vintage flower frogs. This woven jar topper is made from the same paper-wrapped floral wire as the Floral Wire Basket (page 76). I’ve used one on the top of a cup of water to keep scallions upright on the counter, and Rose uses one to keep her parsley tidy in the fridge. They help make wide-mouthed mason jars and water glasses into the site of your next flower arranging masterpiece, and they can be used over and over again. To make a small wire flower frog, we scale down the size of the loom by using a cardboard tape roll core in place of an embroidery hoop. (See the Simple String Bag instructions on page 72 for how to cast on and knit using the loom.)

SUPPLIES AND TOOLS

+ Empty 3-inch / 7.6 cm cardboard tape roll core

+ 5 round wooden clothespins

+ 26-gauge paper-wrapped floral wire (you’ll only need 2–3 feet / 61–91 cm)

+ Scissors

1. Place the clothespins evenly spaced around the perimeter of the tape core.