HISTORY MAGAZINE

Welcome, dearest reader, to the inaugural issue of Historica Sapientia.

In such early youth, one can only hope it will live up to its name, tongue-in-cheek as it may be. What we offer you within, is a wide range of articles, varied in depth, breadth, and era; content spans from 65B.C. to the twenty-first century. Hence, we hope there is something for everyone.

Without being too shameless in my praise of my colleagues, I must draw your attention to the considerable volume of work which has been made manifest in this magazine. I must thank our creative and literary engines- our writers, without whom we would have nothing at all; my fellow editors, who have combed articles for split infinitives, made light syntactical alterations, and perhaps most challengingly, tried to fact-check areas on which our expertise was far from guaranteed. The dynamic duo who have made up our design team have put hours into adapting articles of all fonts and formats into what you shall see before you today, not a task without its ardour, but, as you shall see, well worth the work.

It would be a gross injustice to only offer gratitude to our student members- my deepest thanks go to Mr Roberts and Miss Bellingan, whose toil and expertise have proved to be immensely helpful at every level- foundation to apex.

On a personal note, I must say what a pleasure it has been to work to make Historica Sapientia- research, writing, and editing have all been a wonderful outlet through which to pursue my own historical interests, and gain insight into the interests of my (again, talented and capable) colleagues.As such, I would like to extend to you an invitation. If you are besotted with a particular period or area of study; if you feel that we have missed a possible goldmine in terms of subject matter; or if you would like to discover a passion within the field, you would find yourself very welcome in our ranks.

Indeed, new members would be greatly appreciated.As much as I would love to make this publication forever, one’s time remaining at Hampton is limited– most of our cohort is leaving in 2024, and we have already collected some alumni. While we tend to focus on the past, this magazine has a future, and that future could be shaped by you.

I have robbed you of quite enough of your time already, so I shall bid you adieu, and hope that you find this issue as enjoyable to read as it was to make.

Charles Blagden Editor, Historica SapientiaContents

¨ The Catilinarian Conspiracies of 65-63BC - Charles Blagden (Page 4)

¨ The Renaissance – Jacques Huet (Page 8)

¨ Why has modern-day Russia never been conquered? - Finlay Milner (Page 10)

¨ Brazil: ACountry of Coups - Harry Pritchard (Page 12)

¨ Politics, Religion, Terror: How decades of instability gave rise toAl-Qaeda and culminated in The 9/11Attacks - Theo Webb (Page 14)

¨ Rocket Propelled Planes of WWII - James Greenfield (Page 21)

¨ The antagonism between collective leadership and personal dictatorship in Russia in the last 100 years - FedorArkhipov (Page 22)

¨ Just following orders? Examining the role of Radio Free Europe in The Hungarian Revolution - Piers Marchant (Page 29)

¨ Marchamont Nedham: Aguide to surviving Civil War- Henry Bramall (Page 32)

¨ America’s Intentions to Boycott The 1936 Olympics - Hal Leman (Page 34)

¨ Catacombs of Paris - Freddie McIntosh (Page 36)

¨ The Gentleman’s Pirate: The Greatest Midlife Crisis ofAll Time - Monty Fletcher (Page 39)

¨ Walter Tull - Dan Cubbon (Page 41)

¨ Pitt, Politics and Patriotism: The impact and legacy of the French Revolution in Britain - Ollie Lycett (Page 42)

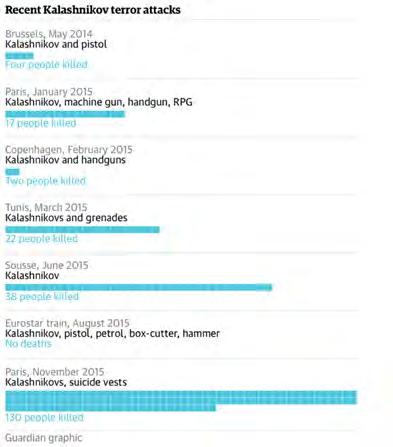

¨ Was the cultural influence the biggest impact of theAK-47 since its invention in 1947? -Aran Taheri Murphy (Page 46)

¨ Atatürk, Turkey’s benevolent dictator? - Finn Watton (Page 50)

¨ Portuguese Exploration to India - Jose Bouras Leao (Page 54)

The Catilinarian Conspiracies of 65-63BC

- Charles BlagdenFriends, Romans, countrymen; lend me your ears, to learn about one of the most significant threats to the Roman Republic in the first century BC (and trust me, there were plenty), and how it was thwarted by one of the best-known politicians and orators in history - Marcus Tullius Cicero.Aword of warning: the first few bits of this are a touch dense, but it gets far easier as you get through; good luck! Perhaps we are getting ahead of ourselves; some context may prove valuable. For three hundred years since it had expelled its last King in 509BC, Rome had been a Republic. No one man would hold absolute power, and when he did, it could only be for a maximum of six months, in times of great emergency. Instead, Rome was ruled by annually elected magistrates called consuls. In power for just a year, and with the ability to veto one another, they were the only individuals with the authority to raise an army. Legislative processes were controlled and voted on by the Roman Senate, comprised of members of noble families, some old, some new, with their seat in the Senate tenured once achieved. Senators were eager to advance their political careers as much as they could, up the rungs of the cursus honorum, the ‘course of honours’.

These were different the administrative and governmental roles in Rome, from quaestors, to aediles, to Praetors (in effect, everyone who’s anyone in a bureaucratic system, see the Glossary at the end for role descriptions), and finally to consuls, our aforementioned executive magistrates- the absolute culmination of a Senator’s career.After one’s term was finished, you had secured glory for your family for generations to come, and were given proconsular imperium (control as a governor, with authority of the Roman state) over a province of the Empire, going over there to govern, and to reap the rewards of doing so. Many proconsuls (the governors themselves) of the wealthy Macedonia and Greece returned after their terms with inexplicably heavy personal coffers- what a coincidence!

One such senator who desired the consulship in the mid-1st Century BC was one Lucius Sergius Catilina, often referred to as Catiline. Catiline traced his lineage back to the very founders of Rome, his first Roman ancestor having arrived withAeneas, Rome’s quasilegendary founder. Unfortunately, wealth falls faster than titles- many Senators were comparatively impoverished, being unable to conduct business since the lex Claudia (Claudian Law) of 218BC, they were only able to rely on the rent of their lands for money, which did not often make enough to cover the immense costs of bribery and political largesse (public spending and acts of generosity) to purchase support. The intricacies of this law are not relevant in an enduring sense, to this article, but it In 66BC, Catiline secured the patronage of one Marcus Licinius Crassus- later triumvir, (‘one of three’, in this context, one of three men with de facto control over Rome) someone who was owed money by half of Rome, and famed for saying that ‘no Roman could consider himself rich, unless he could raise and supply his own army’. Perhaps with such a strong financial backer, Catiline could secure the consulship, even if only as a puppet to a more influential man? Alas, it was not to be. As a propraetor (another type of regional governor), he had been accused of extortion, and was thus barred from standing for election. Eheu!

Our hero continues on, saddened and facing a charge of extortion. He is also alleged to have created a plot to kill the consuls of 65, but whether this was true can be called into question. Nonetheless, the consuls make it through their terms intact, and Catiline manages to bribe his way out of his extortion charge.Avaluable lesson to all: if ever in a pinch, try bribery. Moving on into the elections of 64, for the year 63 Catiline has not abandoned his consular ambitions, and runs as one of seven candidates, among whom are Cicero, andAntonius Hybrida, the two other most viable candidates. Julius Caesar and Crassus decide to sponsor Catiline and Hybrida for their elections, in order to keep Cicero out of office. ‘Why’, you might ask, ‘would they do that?’. This is largely due to Cicero’s position as a novus homo; a ‘new man.’Someone not born into the nobility, but raised into the Senatorial class by his actions, in Cicero’s case through an extraordinarily strong career as a barrister. The affront it would have been to the (even more) ancient houses of Rome for someone of ignoble stock to take the consulship was untenable. Surely, with the backing of possibly the most famous Roman ever, and a financial powerhouse, Catiline could have his dreams realised, and achieve the consulship- restoring to glory his impoverished family’s name, and with it, refill the coffers of the Sergii? True to form, he misses the mark, yet again. One could almost consider it a skill- many Romans of such esteemed stock could essentially have the consulship fall into their laps, simply by waiting for long enough, although the Sergii had not produced a consul for 300 years. Cicero had taken the day, topping the polls, with Antonius next, and Catiline trailing in third place.

Undeterred, he makes a third bid for the consulship, in spite of having now been unceremoniously ditched by Crassus. Say what you will about Catiline, the man is tenacious. His election campaign in the year 63BC runs on one main policy- novus tabulae, the general forgiving of debts. Understandably, this was immensely popular with groups of society who owed significant sums of money: farmers with mortgages on their farms, and rather interestingly, quite a few Senators. These senators had lived beyond their means, to such an extent that aid in financing their lifestyles and the debt incurred as such could drive them to support Crassus in the Senate, or Catiline at the booths. Promising, wouldn’t you say? Where the policy fails is in winning the votes of the Ordo Equester, the wealthy non-nobility, who had taken advantage of the vacuum created in trade by the aforementioned lex Claudia of 218, and as such become obscenely wealthy. What is there to do with such wealth, but lend it out in order to charge interest on it? The losses that the novus tabulae would incur for these wealthy creditors would be absolutely devastating. It was not all popular in the Senate either- Cicero, consul-incumbent, presiding over the election, called it tantamount to fraudulent debt evasion (devastating). To be perfectly frank, dear reader, I am running out of ways in which to tell you that Catiline fails to achieve the consulship. My lack of creativity cannot change history, and as in his every attempt to secure the consulship, he fails, not least due to Cicero’s condemnation of his primary vote-winning policy.

In theAutumn of 63, Catiline is fed up. ‘Sod it,’he thought (verbatim, I promise). He plans a coup de main with fellow ruined Senators, and some disgruntled veterans of the brutal and bloody civil war of the Eighties, hoping to march on Rome. This would not be the first time Rome was marched on by its own (that honour goes to Sulla, some of whose veterans were planning to do the same again), nor is it the most famous (of course being Caesar crossing the Rubicon, now common idiom), but it was still a worry and a threat which which the Republic must deal. To use an anachronistic term, there was a Judas in their midst. This informer had exposed the plan to Cicero, who swiftly declared a state of emergency, and added patrols of the vigiles, Rome’s urban police force around the city. Now, Catiline is apprehended and brought before the Senate, at which point Cicero delvers his first Catilinarian Oration (In Catilinam I). I shall not transcribe it here, but instead provide you with as concise a summary I can: Cicero eviscerates Catiline verbally, and Catiline is ostracised within the Senate house. Cicero, in his infinite respect for the Constitution, and not totally secure in his consulship as a novus homo, decides to leave Catiline at large, in order to procure more evidence. One concludes that this is because Cicero did not want to face accusations of overstretching the bounds of his power as consul- unlike other eminent politicians, his authority did not come from immense wealth, or an army more loyal to its general than the state, but the Roman constitution itself, and as such could not afford to bend or break it in any way. Catiline flees, of course, with a desire to rally various unhappy pockets of rebels behind him, and take Rome by force.

They say patience is a virtue, and the next stage of our story demonstrates that quite well. Catiline’s allies in Rome are impatient, as Catiline tries to convince people across Italy that their qualms and gripes are worth fighting and dying for. In waiting, his allies grow restless, and decide to reveal the truth of their plan to some Gallic envoys, hoping to gather support from their tribe. I’m sure you have realised, dear reader, that this story seems to repeat itself quite a bit: Catiline tries and fails to secure the consulship, Cicero berates Catiline, and now, Catiline’s plot is ruined by an informer for the second time too. The Gauls had told Cicero immediately, and the nobles who had sided with Catiline are tried in the Senate. This is particularly disastrous for them, since not only were they overtly guilty (one hears that this hurts your chances in court), but they were also being prosecuted by someone who had overcome regional and class-based prejudices to achieve the highest office in Rome, by dint of his skill as a barrister. Cicero sought capital punishment for these nobles, but was unsure whether it was legal to do so- they were not yet doing something worthy of capital punishment, though much of the Senate understood the draw of their executions. One Senator who spoke against the death penalty in this case was Caesar himself. Though not yet what he would be, he was a rising star within the Senate, and he made the case that the accused should be detained for life. Caesar had no great personal connection to them, it is more likely the case that he did not wish to return to the age of massacres and proscription lists (think of a state-sanctioned fatwa with monetary payout), out of which Rome had just escaped.Aprominent senator, and Caesar’s first political nemesis, Cato the Younger made the case in favour of execution, and ultimately won the day.

What happened next is best put by Max Cary, in his History of Rome; ‘While Catiline’s associates in Rome were engaged in cutting their own throats, his emissaries in Italy accomplished nothing more than to collect scattered groups of rebels.’Catiline’s efforts are leading to seemingly little, and so he resolves to do the honourable thing and flee. Unfortunately, he is halted by the army of Quintus Metellus Celer, a member of possibly the most powerful family in Rome, and is routed, fleeing again, but no longer on his own terms.

Catiline throws his own life and those of his supporters away in a doomed attempt at attacking a pursiuing force. Rome is safe, but was it ever in any real danger from the hapless, unscrupulous, yet infinitely ambitious Catiline? It seems that Italy was far too calm, and fatigued from civil war, to allow a second temporary monarchy, as it had endured under Sulla. If Catiline had taken sustained power, he would likely have been condemned to play second fiddle to Pompey the Great, who would have been able to make a return with a terrifyingly large force, and dislodge Catiline as the unconstitutional ruler.

Cicero is the man of the hour, in the wake of the Conspiracy. He is venerated by the Senate, and the senator Catulus (not the poet) suggests he be given the title of pater patriae (Father of the Fatherland), an incredible accolade which put him on par with Romulus himself, out of sheer gratitude to Cicero. Cicero had achieved not only the consulship, but am exceptional one too, one to be remembered for years to come. The weight his voice would carry in the Senate for the decades to come was gargantuan.As a result of Catiline’s ability to exploit popular discontent, the Senate supported a particularly generous bill increasing the amount of corn given to the plebeians (working classes and peasantry, primarily agrarian), to avoid other uprisings and populist demagogues from appealing to them.

Well, dear reader, I do hope you’ve enjoyed this rather long account of Catiline’s fifteen minutes of shame, failing, failing, and failing again to achieve his ambitions. One hopes too that you have an improved understanding of Roman politics in its Republic’s most tumultuous days, and more than anything, that this has developed any interest you may have had in the ancient world; at best, created one; and at minimum, not stamped it out.

Vale!

The Renaissance – Jacques Huet

The Renaissance was a cultural movement that originated in modern day Italy beginning in around 1300 and lasting till 1600. The Renaissance period marked the global transition from the Dark Ages into a period of cultural revival, with renewed interests in classical antiquities, the growth of Humanism, and increased patronage of artists and creatives. Most historians agree that Florence and the surrounding countryside was the birthplace of the Renaissance. It was the ideal area for the cultural movement to take shape; the lucrative wool trade that was central to Florence's economy had elevated many people to extreme wealth, and they used this wealth to commission the early writers and artists that came from the surrounding hills to make beautiful artworks and scriptures that are still so famous today.

This cultural revolution spread throughout Europe, with the new Humanist thinkers changing the ways people looked at religion, the most notable examples of this are through Erasmus and his influence in England and on the young prince Henry VIII. Furthermore, the artists and writers like Michelangelo and of course Leonardo da Vinci created pieces that changed history and influenced world leaders of the time to change their styles and ideals. For example, the gothic architecture and sculptures of the 'DarkAges' transitioned to free standing sculptures, and buildings that had increasing classical elements, including columns, pilasters, pediments, and entablatures. These buildings were often commissioned by the wealthy Florentines, most notably the Medici's, a family that is inextricably linked to the prospering Florentine economy and the propagation of the Renaissance throughout Europe.

Florence was a Republic, but not in the modern sense of the word. It had a constitution that limited the power of nobility, as well as the labourers, and thus ensured that no one person could have complete political control over the city state. However, a very small percentage of the population actually had the right to vote, and so elections were often very biased. This meant that power usually resided with the wealthy wool traders, or other powerful families, most notably the Medici's. The Medici family, starting with Giovanni Di Bicci Medici, made their fortune through providing financial services for most of the nobility and royalty in Europe.

This allowed them to amass a sizeable fortune that would allow them to effectively rule Florence and become the main drivers of the Renaissance through their investments into the city and through their patronage of the early writers and artists of the period. The Medici bank was created in 1397 and quickly became one of the most respected and prosperous institutions in Europe with branches in major cities like London, Lyon, Geneva, and Bruges. This - along with the bank having clients like the papacy and the Kingdom of France - propelled the House of Medici into being arguably the wealthiest family in Europe.

Along with the Medici bank and its long list of high profile, affluent clients; Florence was also a major trade hub, specifically in the trade of wool. Out of an estimated population of 80,000 in 1340, over 25,000 people where related in some way to the wool industry, and this elevated many Florentines into extreme wealth. These wealthy traders built huge mansions in the city as well as villas in the countryside and contributed to the building of cathedrals and experimental architecture, that boosted the physical and cultural rebirth of the city. Subsequently, competition arose quickly between the rich merchants as to who could build the biggest mansion or villa, or who could commission the most famous and beautiful work of art. This accelerated the effect of the Renaissance, with an increasing number of artworks being commissioned and grand houses being built, allowing this cultural revolution to spread rapidly throughout Europe in a few short years.

Why has modern-day Russia never been conquered? - Finlay Milner

Modern-day Russia dates from the 16th century from when the state of Russia was ruled over by an absolute monarch known as a Tsar (a word which derives from the Roman emperor Caesar). Russia’s enormous landmass, harsh winters and willingness to suffer huge casualties to achieve victory all contribute to its ability to defeat many invaders over the years.

Russia’s huge size meant that it was difficult to invade. For example, Napoleon ( emperor of France at the time) was a great military leader, along with many other things, he used speed to destroy his enemies in a quick, decisive battle while him and his soldiers would live off the land so that slow supply chains would not slow them down. However, Russia’s great size meant that their army could just retreat through their vast countryside and burn everything while retreating so that they would leave no supplies for the opposing army. This tactic, known as “scorched earth,” would work particularly well against Napoleon’s forces who would starve to death as they travelled over a 900km distance.An estimated 150,000 French soldiers out of the 600,000 strong invasion force died of starvation and the French invasion would soon end in an embarrassing defeat for Napoleon. The first use of the “scorched earth,” tactic was actually in 1707 when the Swedish empire invaded Russia and, yet again, was one of the causes of another Russian victory as they repelled the Swedes. Russia’s ability to keep retreating through their vast lands had proved key to their potential to defend their country.

Another important factor of the Russians inability to be conquered is the Russian winter. For instance, when the Swedish empire, under the rule of Charles XII, invaded the Russians spent months retreating to avoid confrontation. By then however, it was winter and by the end of it the “Great Frost of 1709,” had devastated the Swedish army and shrunk it from 40,000 men to 24,000 men. This lead to the Swedish invasion being a failiure and another Russian victory.Another example of the Russian winter playing a role in the outcome of an offensive is the German invasion of Russia on the 22nd of June 1941, named Operation Barbarossa.Again the Russians kept retreating using their “scorched earth,” tactic. When winter came the German advance stopped and a total of 100,000 men died of the cold with average temperatures of -12.8 degrees in December of 1941 in Moscow. Furthermore, Stalin then called men from Siberia who were specially trained to fight in the extreme cold to lead a successful Russian counter-offensive which saw the Russians push the German lines back 150km. The Russian winter played a huge role in warding off invaders.

Additionally, one more significant factor of Russia’s successful defending of their country is their willingness to suffer losses.As when the Russians were pushing the Germans back into Europe from 1943-1945 in WW2 they lost far more men than the Germans in battles like the Second Battle of Kiev, where the Russian’s casualties and losses were 118,042 men while the German’s were 16,992.Also in the battle of Kursk ,which is considered to be the largest tank battle in history, the Russian’s casualties and losses were 863,000 while the Germans were 203,000.

Overall, Russia’s willingness to suffer staggering human losses is why it has never been conquered. The inexhaustible supply of young Russian soldiers is what seems to always to lead to eventual victory.

Brazil: A Country of Coups - Harry Pritchard

Brazilian history has been shaped by coups and uprisings since 1889 with the last one occurring just this year. This report looks at the different coups which have influenced the country.

The 1889 Military Coup d’état, also known as the Proclamation of the Republic, led to the establishment of the First Brazilian Republic on the 15th of November 1889. The coup took place in the capital, Rio de Janeiro, and was led by Marshall Deodoro da Fonsea. The military coup overthrew the monarchy of the Empire of Brazil and also ended the reign of Emperor Pedro II. This led to the creation of a provisional government by Marshall Deodoro da Fonseca, on the 15th of November 1889.

So, what factors influenced this peaceful coup?

Firstly, Emperor Pedro II had no male heirs, and as his eldest daughter was married to a Frenchman, the elites were worried about potentially being ruled over by a foreigner. Secondly, the monarchy, via the Golden Law in 1888, had abolished slavery, which was incredibly unpopular with the elite as they weren’t compensate; this made many of them increasingly resent the monarchy. Finally, the army was becoming increasingly frustrated and resentful towards the monarchy. This was due to the ideas of positivism and modern ideas, which were spreading rapidly through the Brazilian army, and due to the fact that promotions within the army were difficult to gain (often coming through name and wealth, not through achievements), which ultimately led to the army becoming frustrated with the monarchy.

The combination of both the army and the agrarian elites led to the successful coup in 1889 against Emperor Pedro II, in which the emperor decided not to resist, shown by him saying, ‘If it is so, it will be my retirement. I have worked too hard, and I am tired. I will go rest then.’Emperor Pedro II was then exiled to Europe along with his family. The 1930 armed revolution within Brazil ended the Old Republic, by replacing the incumbent President Washington Luis, with Getulio Vargas. The states of Minas Gerais, Paraiba and Rio Grande do Sul formed the Liberal Alliance which backed Vargas against Julios Prestes who was backed by Sao Paulo and the incumbent President. When Prestes won, the Liberal Alliance declared the election as fraudulent, and therefore orchestrated an armed uprising which started on 30th October 1930. Luis had his power removed by military leaders, who eventually gave their powers to Vargas on the 3rd of November 1930. On the 11th of November 1930, Vargas issued a decree, that awarded himself dictatorial powers. In 1937 Vargas created a new constitution, the Estado Novo Constitution. This new constitution abolished legislative assembly and replaced the majority of state governors with men that Vargas approved of. This therefore increased his power by removing checks and balances on his power. This started the 3rd Brazilian Republic, Estado Novo, and led to Vargas becoming a dictator from 1937 to 1945.

The 1964 Brazilian Coup was a military coup which led to President Joao Goulart being overthrown by the Brazilian Armed Forces in a 48-hour period from 31st of March to the 1st ofApril. Goulart had poor relationships with both the Brazilian military, due to his handling over the Sailors’ revolt in 1964, and with America. Goulart publicly criticised theAmerican-led Bay of Pigs Invasion and was also threatened with economic pressure by the USA. The Brazilian Army also informed the US that there were suspicions of Goulart sympathising with communists, which led to the USAbeing against Goulart’s presidency. However, Goulart also failed to secure foreign investment and also failed to reduce domestic inflation, further reducing his support within his country. Goulart also had no military support outside of the South of Brazil, and had also alienated himself from Cuba by criticizing Castro’s regime.All of these factors led to Goulart being very vulnerable to rebellion and revolt within Brazil and lack of international support further weakened his position.

On the 2nd ofApril, Brazilian Congress came out in support for the coup, and later, on the 11th ofApril, Castello Blanco was elected President by National Congress, replacing Goulart.

The most recent Brazilian Coups happened very recently, on the 8th of January 2023, in which the incumbent president Jair Bolsonaro was defeated by Lula in the election, leading to a mob of Bolsonaro’s supporters invading government buildings in the capital, Brasilia. Bolsonaro’s supporters then vandalised the National Congress building, the Supreme Federal Court and the Planalto Presidential Palace. Bolsonaro’s supporters claimed election fraud which led to Lula being elected on the 1st of January, so this invasion of government buildings was to overthrow President Lula despite Lula being democratically elected. The rioters were predominantly armed with sticks and stones and the federal government estimated that around 5000 protestors had taken part.

However, this attempted coup failed, as it took security just five hours to clear the government buildings and the coup was condemned by governments around the world. The attempted coup also led to Lula signing a decree authorising a federal state of emergency in the Federal district which lasted until the end of January. At the time of writing it has only been just over a month since the attempted coup so given the fragility of Brazil and their history of coups within this country, there may be further developments in the months to come.

Politics, Religion, Terror: How decades of instability gave rise to Al-Qaeda and culminated in The 9/11 Attacks - Theo Webb

[September 11th, 2001] - Many remember the impact - 4 planes, 3000 dead, the world in disarray, drunk on the shock, the bewilderment - that something like this could even happen in a modern society. Many remember the response: the heroics of the 343 firefighters that died trying to save the lives of those trapped; a fiery, burning mess on the higher floors of the World Trade Centre. Many remember the vengeance: the steel ofAmerican resolve, George Bush, Operation Enduring Freedom, a 25 million dollar bounty on Bin Laden’s head. However, many overlook the causation - the decades of instability which lead to the resurgence ofAl-Qaeda and their protectors, the Taliban. This may be history, but it is ever-relevant following the US withdrawal from the country resulting in the fall of theAfghanistan government to Taliban forces inAugust 2021. Could we be seeing a repeat of the past?

One can judge this exponential rise in 3 phases - the Saur Revolution and the Soviet occupation, the transition from the GenevaAccords Into the Mujahidin’s Civil War, and the Taliban’s Conquest ofAfghanistan and the consequential rise ofAl-Qaeda.

Phase 1 - The Saur Revolution and the Soviet Occupation:

Before one asks the question of howAl-Qaeda came to power, it is important to understand the nature of the political Instability within Afghanistan, and how this created the environment for Islamic extremism to flourish. Before its civil war,Afghanistan was a monarchy under Muhammad Shah, who had been in power since 1933.After World War

Two, both the US and the Soviet Union used various forms of economic aid to jostle for influence. However, sinceAmerica had decided to side with Pakistan in 1954,Afghanistan increasingly turned to the Soviet Union for support. Whilst religion, or more specifically Islam, had not yet manifested itself fully inAfghanistan’s politics, we can see the roots of influence starting to form. In 1962, Zahir Shah convened a grand council of tribal leaders to proposed a constitution in draft form, which would in theory pave the way for a more democratic, representative government. Whilst this in theory seemed a positive change that would result in the unification of the different factions within Afghanistan, it did quite the opposite. Zahir Shah refused to relinquish any form of power - parties could organise elections, however they could never in reality contest them. Therefore,Afghanistan remained largely a monarchy - exceedingly prone to revolt and uprising in a country that contains such a diverse variety of ethnic groups. The largest of these are the Pashtuns - who are native to the Pashtunistan region of southern and north-western Afghanistan, and compromise 42% ofAfghanistan’s population, notably not a majority, indicative of the instability ofAfghanistan’s politics, both then and today. Other groups include the Tajiks, the Hazaras and the Uzbeks - in descending order of population TheAfghan Constitution (before 2021), mentioned only 14 individual ethnic groups, whilst in reality there are far more, re-

Asignificant observation to make from this is the harsh divide between those following the Sunni, and Shi’a practices of Islam. Shi’a Muslims are by a large margin, in the minority, constituting only 10-13% of the Muslims inAfghanistan - and are mainly Hazaras. The real difference between the two branches of Islam is their perception of the religion. Both branches are based on the teachings of the holy Quran- with the exemplary way of life for Muslims being defined by those teachings and the teachings of the Prophet Muhammed. The difference between the ideology of the 2 sects is that Shi’a Muslims consider Imams (Islamic worship leaders) to be divine and in possession of spiritual authority, a mediator betweenAllah and his followers. For Shi’a, Imams are not inferior to the Prophet Muhammed, but his representatives on Earth. In contrast, Sunni’s attach no reverence to Imams, and view them as simply religious leaders within the community. However, when one comes to consider how this difference becomes a catalyst for political instability, and the consequential Afghan civil war- there is a more nuanced difference to be examined. Whilst Sunni Muslims adhere to, and practice the 5 pillars of Islam- Shi’a Muslims, as well as practicing the 5 pillars (albeit subtly different), practice the 10 ancillaries. This includes Jihad, which composes of 2 elements: an inner struggle with oneself to maintain the way of God, and an outer struggle against Islam’s enemies, which can often be violent. Many simply hear the word Jihadis used to describe Muslims, and unconsciously associate this with religious conflict, or Terrorism. While partially true, it is important to understand the significance this had in creating the internal discord within Afghanistan and the ideal conditions in which civil war and power could be so readily waged - as it is backed by the fundamental beliefs of the combatants who had nothing to lose, with the promise of being rewarded byAllah in the afterlife regardless.

This revolt quickly materialised in the form of a coup, in which Shah was overthrown by his cousin, Daoud Kahn, who was represented by the peoples Democratic Party ofAfghanistan, or the PDPA. There were various political factions within this party, one, the Parchams, representing the educated people from the more urban areas of the country. The other, the Khalqs, (or masses in English), drew its support from the educated rural communities. These 2 factions collectively overthrew their leader, Daoud Kahn, killing him in 1978 and seizing power. They formed a new government, with a rather clever ranking system, carefully constructed to alternate positions of importance between the Parchamis and the Khalqs. This was the Saur Revolution in action. The PDPAgovernment embarked on a campaign of radical land reform, accompanied by mass repression in the countryside resulting in the arrest and execution of tens of thousands, as they forced their reforms on the traditional rural people. This distinct separation between the educated populace of the urban cities and the traditional masses, which resided in the countrysideis indeed another factor which contributed to the sheer instability withinAfghanistan at the time. It is important however to note that there were some positives that came from the reforms - the emancipation of women and the reduction of feudal practices, such as usuary (the practice of loaning out money and demanding repayment with especially high interest rates). Furthermore, forced marriage was discouraged, education for all was established, and sharia law was abolished.

From the lens of someone living in the western world today, you might assume that these reforms were automatically popular - however this program of rapid modernisation, centred on the separation of the Mosque and the state, was very unwelcome. It was considered a deviation from traditional Islamic values and a forced approach of western culture inAfghan society. One must realise here that these people have been living in this way for the entirety of their lives, and in a county that is 98% Islamic, western reforms were unlikely to be popular. This became a catalyst for the unification of the ethnically diverse tribal population against the the unpopular new government, and essentially the advent of Islamic participation inAfghan politics. Thus, this resulted in huge uprisings across the country - and exemplifies the new fusion of religion and politics in Afghan society and culture.

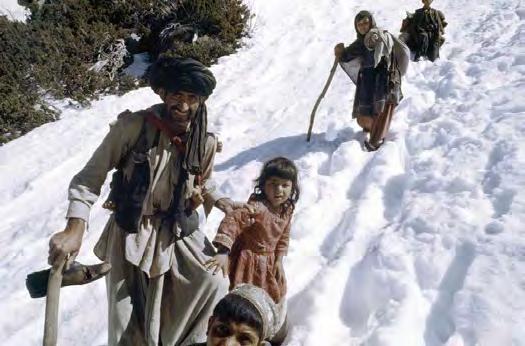

The Soviets were alarmed by this deteriorating situation, especially by the collapse of the army and indeed of total order. In 1979 the Soviet Union airlifted thousands of troops into Kabul.As such, the President of the government at the time, Hafizullah Amin, was also assassinated after Soviet intelligence forces took control of the government. The Soviet force subsequently embedded themselves within Afghan society - spreading the Communist doctrine from the ground up, starting from lower education.As a result of this pockets of rebellion immediately started to spring up, slowly escalating. The army of some 115,000 troops, as well as the new Soviet appointed government, sought to crush the uprisings with mass arrests, executions, and in some cases, even aerial bombardments. The estimated death toll throughout the period was over 1 million. As more and more people died - the resistance of the communist government only increased - deepening the political rifts and adding yet another dimension to the instability that was already present. This, in turn, fuelled a flow of refugees out of the country that reached 5 million out of a population of 16 million - a rate of over 30%. For reference - this is over half the total number of refugees during the entirely of World War One. Here we see the true beginning of established terror organisations within Afghanistan - as Islamic organisations became the heart of the resistance against the Soviets. These were known as jihad fighters, or the mujahidin.Amongst these was the young son of a millionaire construction magnatelater well known as Osama Bin Laden.

In 1980, the UN general assembly passed a resolution protesting against the Soviet intervention, and it was passed by 104 votes for to 18 votes against. The US saw this as an almost Cold War-like background, and provided masses of support for the resistance cause, funnelling nearly all of it through Pakistan – and was aided by UK, Saudi Arabia, and China. By contrast,Afghan insurgents began to receive massive amounts of support through aid, financing and military training in neighbouring Pakistan with significant help from the United States and United Kingdom. They were also heavily financed by China and the Arab monarchies in the Persian Gulf. One can see here how the US is locked up in an intense battle against the Soviet Union – and fails to notice that it is in actual fact financing future terrorist organisations. Joining the resistance forces were thousands of Muslim radicals from the Middle East, North Africa and other Muslim countries. Most fought with Pashtun factions that had the strongest support from Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, the Hizb-i Islami of Gulbuddin Hikmatyar and Ittihad-i Islami of Abdul Rasul Sayyaf. Among them was Osama bin Laden, who came to Pakistan in the early 1980s and built training facilities for these foreign recruits insideAfghanistan. He is now mot simply a religious fighter, but a leader - capable of managing men. Here we can see the advent ofAlQuaeda, and the emerging significance of Osama Bin Laden, who would later come to be the most wanted man of the planet, as the orchestrator of the 911 attacks.

The Second Phase: From the Geneva Accords to the Mujahidin’s Civil War: Negotiations to end the war culminated in the 1988 GenevaAccords, which contained an agreement made by the Soviet Union to orchestrate a complete withdrawal of all its troops by February 1989. In 1999 the UN Security Council adopted resolution 1267, creating the Taliban sanctions committee - illustrating the fact that terrorism within Afghanistan is now becoming a globally recognised threat. With Soviet assistance, the government held on to power through early 1992 whilst the UN attempted to assemble a transition process. The U.S. and its allies abandoned any further efforts towards a peace process until after the Taliban had come to power. Whilst one may argue that the Soviet Union had no right to exert undue influence on the people ofAfghanistan in establishing its regime - it provided a form of law and order, something that now has been reduced to aught but nothing. The UN effort continued. but suffered from the lack of international engagement in Afghanistan. Donor countries, including the U.S., continued to support the relief effort, but as the war dragged on, media attention onAfghanistan was reduced and the need to respond to other humanitarian crises left the assistance effort in Afghanistan falling short. This created the perfect environment forAfghanistan to become a country that is ruled by factions. In 1992 the Northern Alliance was established – made up of Tajiks, Uzbeks and Hazaras - the 3 largest ethnic groups within Afghanistan. Non-Pashtuns mutinied and took control of Kabul airport – preventing President Najibuillah from leaving the country – and soon after Northern Alliance factions reached a coalition government. Civil war thus ensured – in 1994 alone, an estimated 25,000 people were killed in Kabul, most of them civilians killed in rocket and artillery attacks. By 1995, one-third of the city had been reduced to rubble.

The Third Phase: The Taliban’s Conquest ofAfghanistan and Rise to Power:

Exiled by the Saudi regime, and later stripped of his citizenship in 1994, Bin Laden left Afghanistan and set up operations in Sudan, with the United States in his sights as Public Enemy No. 1.Al-Qaeda took credit for the attack on two Black Hawk helicopters during the Battle of Trans Mogadishu in Somalia in 1993, as well as the World Trade Center Bombing in New York in 1993, and a car bombing in 1995 that destroyed a U.S.-leased military building in Saudi Arabia. In 1998 the group claimed responsibility for attacks on U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania and, in 2000, for the suicide bombings against the U.S.S. Cole in Yemen, in which 17 American sailors were killed, and 39 injured. During this period of civil war, mujahidin commanders established themselves as local warlords, and were defectively the government at the time. Humanitarian agencies were fiercely persecuted, finding their offices stripped, their vehicles hijacked and their staff threatened - a coordinated intervention of Western powers was now sorely needed. Under this background the Taliban emerged yet even stronger.

Al-Quaeda was founded in 1988 by Osama Bin Laden, and means ‘the base’in Arabic. Former mujahidin who were disillusioned with the chaos that had followed their victory became the centre of a movement that coalesced around Mullah Mohammad Omar, a former mujahid from Qandahar province. The group, many of whom were madrasa (Islamic school) students, called themselves Taliban, meaning students. Many others who became core members of the group were commanders in other predominantly Pashtun parties, and former Khalqi PDPA members. Their stated aims were to restore stability and enforce (their interpretation of) Islamic law. They successfully attacked local warlords and soon gained a reputation for military prowess, and acquired an arsenal of captured weaponry. By October 1994 the movement attracted the support of Pakistan, which saw in the Taliban a way to secure routes to Central Asia and establish a government in Kabul that was friendly to its interests, and Pakistani traders who had long sought a secure route to send their goods across to CentralAsia quickly became some of the Taliban's strongest financial backers. In September 1995 the Taliban took control of Herat, cutting off the land route connecting the Islamic State ofAfghanistan with Iran. The Taliban's innovative use of mobile warfare appeared to indicate that Pakistan had provided vital assistance for the capture of Herat. In September 1996, the Taliban took control of Kabul after Massoud was forced to retreat to the north. Sometime after Massoud's loss of Kabul, he began to obtain military assistance from Russia as well as Iran. The NorthernAlliance was reconstituted in opposition to the Taliban.

Osama Bin Laden, who had left Afghanistan in 1990, returned in 1996 – and moved to Qandahar where he developed a close relationship to Mullah Muhammad Umar, the head of the Taliban. His fighters fought alongside Taliban troops. In 1997 – the Taliban turned their attention to enforcing Islamic rule, enacting policies prohibiting women from working outside the home in activities other than health care, and requiring corporal punishment for those convicted of certain crimes. They prohibited women from attending universities and closed girls' schools in Kabul and some other cities, although primary schools for girls continued to operate in many other areas of the country under Taliban control. The Taliban also enforced a strict dress code for women, and required men to have beards and to refrain from Western haircuts or dress. “In particular, al Qaeda opposed the continued presence ofAmerican military forces in SaudiArabia (and elsewhere on the SaudiArabian peninsula) following the Gulf War,” the Council reports, adding that “Al-Qaeda opposed the United States Government because of the arrest, conviction and imprisonment of persons belonging to al Qaeda or its affiliated terrorist groups or those with whom it worked. For these and other reasons, Bin Laden declared a jihad, or holy war, against the United States, which he has carried out through al Qaeda and its affiliated organisations.” – Council on Foreign Relations. “The U.S. today, as a result of the arrogant atmosphere, has set a double standard, calling whoever goes against its injustice a terrorist,” bin Laden said in a 1997 interview with CNN.

Through 1997 and 98, the Taliban made repeat attempts to extend their control to the North ofAfghanistan, where Dostum had carved out what amounted to a mini-state comprising five provinces which he administered from his headquarters in Shiberghan. Dostum’s forces centred in Mazar-i Sharif, howeverAbdul Malik Pahlawan (generally known as "Malik"), who had a grievance against Dostum, struck an agreement with the Taliban and arrested a number of Dostum’s commanders and as many as 5,000 of his soldiers.

This provided an opportunity for the Taliban to have control over the whole country - and Pakistan was quick to seize the opportunity to recognise the Taliban as the government of Afghanistan, as was SaudiArabia and the UnitedArab Emirates. The alliance with Malik disintegrated, fighting ensued, and 3000 were taken prisoner. Eventually in 1998 Taliban finally took control of Mazar-i Sharif and massacred at least 2,000 people, most of them Hazara civilians, after they took the city. In the aftermath, Dostum left Afghanistan for exile in Turkey; Malik also fled and has reportedly lived in exile in Iran since 1997. Now, the US response started, albeit too late. In August 1998, the United States launched air strikes against bin Laden’s reputed training camps near the Pakistan border. The strikes came in the wake of the bombings of the U.S. embassies in Nairobi and Dar es-Salaam. In October 1999 the U.N. imposed sanctions on the Taliban to turn over bin Laden, banning Talibancontrolled aircraft from takeoff and landing and freezing the Taliban's assets abroad. The Taliban's failure to hand over bin Laden led to an expansion of the sanctions regime on December 19, 2000, including an arms embargo on the Taliban, a ban on travel outsideAfghanistan by Taliban officials of deputy ministerial rank, and the closing of Taliban offices abroad. This, as you can imagine, angered bin Laden, and only set the precedent for what was about to happen.

On September the 11th, 2001, four passenger airplanes were hijacked by al-Qaeda terrorists, resulting in the mass murder of 2,977 victims in New York, Washington, D.C. and Somerset County, Pennsylvania. Bin Laden was named as the orchestrator and prime suspect.

9:03am - Hijackers crash United Airlines flight 175 into the South Tower of the World Trade Centre.

Rocket Propelled Planes of WWII - James

GreenfieldThroughout the Second World War, there were many weird and wonderful aircraft designs, many of which did not make it past the drawing board. However, of the few designs that were able to make it through the experimental phase, the Me 163 “Komet” stands out.

The concept was first devised and developed by Alexander Lippisch, and in 1939 the decision was made to use rocket engines for propulsion, as opposed to a single front propellor which had been a feature of contemporary designs. The Komet’s first flight on the 1st of September 1941 demonstrated unprecedented performance and, after being optimised for mass production, it became the first aircraft to ever travel over 1000km/h in level flight – with a maximum speed of 1,130km/h being achieved in July of 1944 by Heini Dittmar. The model entered service this same year and was used in minimal numbers to defend bomber formations.

By the end of the war, only approximately 370 had been produced due to a combination of production line failures and resource shortages. The Komet’s overall failure can be linked to the fact that it was a highly dangerous aircraft – on account of the rocket fuel it used, which was corrosive and highly explosive, killing test pilots on a number of occasions. The plane also had a skid instead of a front wheel – a design feature that meant that upon heavy landings, pilots could suffer significant spinal injuries. There is currently a surviving Komet exhibited in the Science Museum in London.

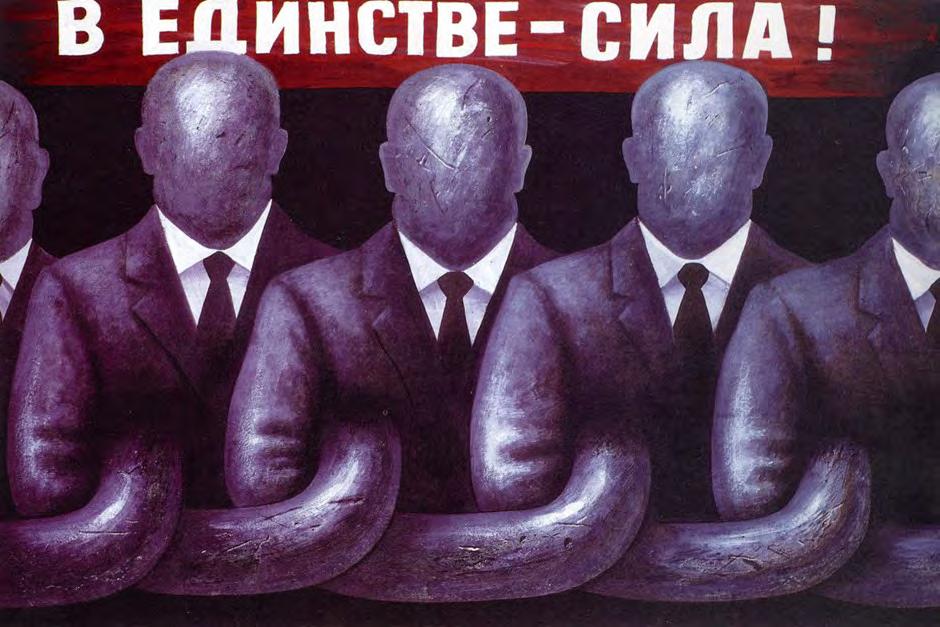

The antagonism between collective leadership and personal dictatorship in Russia in the last

100 years - Fedor Arkhipov

On 24 February 2022, the ground of Europe trembled for the first time in decades with the rumble of tanks and rocket attacks. The wars in Europe seemed to have ended on 8 May 1945, and conflicts were mostly on the periphery, with dictators trying to change the order of their countries by brute force, initially failing in their cause. The word dictator is mentioned for a reason.As the title suggests, the article is about Russia. Now, more than ever there is talk of a full-blown dictatorship in Russia, and the dictatorship in Russia is personal; the full extent of power belongs to Vladimir Putin personally. Until 20 years ago, there was a debate whether Putin's regime is an oligarchic dictatorship or a personalised dictatorship. On February 24th that debate was sealed.After all, a military venture is more a sign of a personal dictatorship than a dictatorship of any group.Andrey Pertsev, an expert at the Carnegie International Center, wrote this the day before the invasion: "Vladimir Putin is increasingly re-inventing himself in a new role. He's no longer a guarantor of stability, and now he's neither an arbiter nor the First. He is not the people's president, not the spokesman for the elite, and not even the intermediary between the elite and the people. He is now the sole boss".And this statement is crucial not only for Russia, but for all of Europe (as Moscow is still capable of influencing European security). Since the last time a sole commander sat in the Kremlin was in 1953, one can speak of a radical shift in the balance of power within Russia and throughout Eastern Europe. Since March 5, 1953, Soviet nomenklatura did everything to avoid personal dictatorship (Russian nomenklatura is just an extension of numerous Soviet bureaucrats) ... But as the morning of February showed, their 80-year-long efforts were in vain.... The struggle between personal dictatorship and collective leadership in the Russian power structure of the 20th and 21st centuries will be the focus of this article.

The roots of collective leadership: the Leninist system:

The very notion of collective leadership is inextricably linked with the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party of the Bolsheviks. In the future, the party would change names: it would become theAll-Union Communist Party and later the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. It has the most direct relevance to modern Russia, because most of the Russian elite was in the Communist Party, although it is important to note that the Communist Party in the ‘70s was strikingly different from the Party of the‘20s. But the path of the Party must be traced from the beginning, which will be done in the following paragraphs. The Leninist Party was created in conditions of struggle, and it operated in extreme conditions (the underground, repression, and then the civil war). However, long-awaited peace had come to Russia, which changed the function of the Party. It needed to concentrate on the urgent tasks of rebuilding the country. Here an important stage in the history of the Party was its centralization, which Lenin wrote about as early as 1917 in his book "The State and the Revolution".At that time, he coined the term "democratic centralism", which implied on the one hand an elective system,

In the centre of the photo (from left to right): Bukharin, Rykov and Stalin. The first two would be shot in 1938.

but the representatives of the people were strictly accountable to the centre - Lenin paid great attention to internal party discipline and its strengthening. Please disregard the word "democracy" in the usual Western sense of the word. The principle of separation of powers was de facto absent in the early years of Soviet power. The key similarity between the collective leadership and the personal dictatorship in the USSR was the total monopoly of power and violence. But it was difficult to reach unanimity on such important issues under the collective leadership, which may explain both the scale of repression under Stalin's personal dictatorship and its decline under the shift from personal dictatorship to collective leadership.

But was Lenin's rule in the twenties a personal dictatorship or was decision-making largely dependent on the party majority? And the problem here is primarily that the very notion of "collective leadership" emerged in the ‘50s, and the above text is an attempt to explain to the reader the premises of both systems. Lenin himself did not rule for long - he died in 1924. But the system that emerged during his time included both democratic principles and a heavy-handed authoritarian style. This was succinctly described by DmitryApalkov of the Department of History at MSU, who writes that although "Lenin was the undisputed leader of the party, it was a long way from establishing Lenin's sole authority. In addition to Lenin, there were other leaders - his closest associates and like-minded people - who possessed considerable political weight. The presence of major political figures in Lenin's entourage hindered the establishment of the Leninist dictatorship.” And hereApalkov gives the example of the confrontation between Lenin and the so-called workers' opposition led byAlexander Shliapnikov in 1921-1922. The fact is that Lenin was unable to expel his then-main rivals from the Party. Expulsion from the Party was a mortal sin for every self-respecting Communist, but Shliapnikov lost his position in the Central Committee of the Party. The workers' opposition was then completely defeated, and its leaders... simply continued to work in the Party, taking an active part in internal Party discussions. It is more likely, however, that intra-party democracy was not Lenin's desire, but rather an obstacle to it.Also, important here were the Bolsheviks, who played a key role in the victory of the cause of socialism in Russia. The most prominent and recognisable representative of this group is undoubtedly Lev (Leon) Trotsky. However, there were other charismatic and not so charismatic people who had influence on the politics of the early Union.

There were also influential military men such as Tukhachevsky. What all the above personalities had in common is that they played a major role in the so-called balance of power within the young revolutionary state.Although they might have fallen into disgrace, they were rarely deprived of their lives and voices. But with Comrade Stalin's rise to power the situation rarely changed.And this brings us elegantly to the next part of the article.

Stalin's dictatorship

Adecisive factor in Stalin’s victory in the intra-party struggle was his control over the party's cadre apparatus. In the ‘20s the Communist Party had finally transformed itself from a revolutionary cell into a huge structure. Since most of the new members came from the lower classes, it was easy for Stalin to establish contact with them and gain their trust. This is how Dzhugashvili gained a party majority, through which he legitimised the deposition of his party opponents. He skilfully manipulated some prominent party members through tactical union methods.

Stalin's total control of the party, coupled with his manic tyrannical nature, led the country to totalitarianism. The fate of millions now depended not on the Party but on the Leader. In the 30s the Leader was purging the army, the dictator's prejudice against the RedArmy was strong, for Trotsky and Tukhachevsky, though neutralised, were extremely important army figures, and their supporters could all wait for their turn. The Party, too, would soon be purged of unruly elements. In 1937.

The reader has already realised that by the second half of the thirties Stalin could do anything to the Party and the country. But what was the reason for such a mass repression? Russian historian Oleg Khlevnyiuk believes the reason could have been the impending war. The atmosphere in Europe by 1937 was already heated enough.And unlike conventional France, which was resting on its laurels of the First World War, the Soviet Union had a clear image of war before its eyes.At issue was the war scare of 1927, when Moscow found itself in a situation of possible conflict with Britain and an entire block of Eastern European states (dominated by Poland). With Stalin's departure from the World Revolution and the doctrine of building socialism in a particular country, the Soviet Union began to turn into a beleaguered camp, and propaganda drew pictures of an imminent war with capitalism.

By 1953 Stalin was too dangerous for the Soviet elite. The important fact was that most Soviet party members had been through a terrible war and felt much braver than in 1937. In addition, Stalin's attacks on his closest supporters and new rounds of repression increased tension in the ranks of the Communist Party. The spectre of a new Big Terror hovered over Moscow.

Therefore, after the extremely fortunate stroke of the Leader of the Party, the model of personal dictatorship was carried into the Mausoleum with Stalin's body. Ironically, when Stalin's body was removed from the Mausoleum (following the logic of the metaphor, personal dictatorship was once again possible), Khrushchev began again to consolidate his PERSONAL power. But there was a gap in between, in which collective leadership existed and acted. Before 1954, no claim to power could achieve parity. This could have been put down to an ordinary power struggle. However, the case of Beria is illustrative here. The all-powerful chief of the NKVD met an ignominious end, in part because he had tried on the sacred.

He tried to reshuffle the cadres in the party nomenclature in Lithuania and Ukraine.And this shows the radical break between the Stalinist and post-Stalinist era. If before March 5, 1953, the official wanted to succeed, he did everything to please Stalin, then after that the centre of his efforts was the Party, which was becoming increasingly all-powerful. Khrushchev played by its rules, did not touch Party privileges, and skillfully pitted the Party against the duumvirate of upstarts Beria and Malenkov. But then Khrushchev became a voluntarist, began to conduct an adventurous foreign policy, and tried to put his opinion above that of the Party members, for example, in questions of culture. So, Nikita Sergeevich was deposed peacefully in 1964. The conspiracy was astonishingly simple. Leonid Brezhnev just suggested that Khrushchev resign voluntarily.All members of the Presidium (members of the conspiracy) voted unanimously to "grant Khrushchev's request to retire".

British journalist Mark Frankland wrote in his 1966 biography of Khrushchev: "In a sense, this was his finest hour: 10 years earlier, no one would have imagined that Stalin's successor could be eliminated by such a simple and gentle method as a simple vote." Khrushchev himself, according to his son, said “I am already old and tired. Let them cope on their own now. I have done the main thing. The relationship between us, the style of leadership had changed fundamentally. Could anyone dream that we can tell Stalin that he does not suit us, and offer him to resign? There would have been nothing left of us. Now everything is different. The fear has disappeared, and the conversation is on an equal footing. That is my merit.And I will not fight.”

Further and further

Brezhnev became the leader of the country. He displayed the only talent necessary for a Party leader: the ability to lead: to give general instructions on all questions without being a specialist in any of them. Brezhnev suited many people by being a compromising figure. He was moderately progressive, but also moderately conservative.

Formally there was a triumvirate in power: Brezhnev led the party, Kosygin led the government, and the formal head of state was Podgorny. However, in the 1970s Brezhnev gradually removed his colleagues from the triumvirate and, at the same time, those who

posed potential danger to him. This is the proof of the triumph of the anti-Stalinist doctrine after 1953. The physical elimination of political opponents was out of the question. Provided, of course, that these political opponents were members of the Party.

Brezhnev, although he became a symbol of the 70s for Soviet citizens, could not concentrate all the power in his hands, even if he wanted to.Abalance of power had been reached. Cadres moved very carefully, the Party nomenklatura had almost become a new aristocracy. The role of the grey cardinal Suslov was also noticeable, the shadow management of the country was another fact which was impossible to imagine under Stalin. But these are all empty words. The real indicator of how decisions were made under Brezhnev is the war inAfghanistan.

Brezhnev himself hesitated for a long time; he was relatively peace-loving. The reformers, including part of the military, were strongly against the war, or rather against the insertion of a limited contingent of troops (80,000). There was an option of a full-scale invasion involving already 300,000+ troops, but Brezhnev did not want a big war. In the end the militarist views prevailed, but again the decision to invade was taken collectively. This is in great contrast to February 2022, when the new European war was headlined by Vladimir Putin personally, giving at least one aggressive speech a day (period of 20-25 Feb 2022).

The Kiev writerAnatoliy Kuznetsov called this process self-imposation. This policy logically led to mass terror, affecting hundreds of thousands whose loyalty was questioned by Joseph Vissarionovich. However, there were other reasons, economic over-centralisation (economic repression in the first half of the 1930s inevitably led to political repression), Stalin's fear of traitors within the Party, and finally, there is an opinion that the terror was the last link in creating a new type of man, Homo Sovieticus.

The key difference between the Stalinist terror of the second half of the 1930s was the physical destruction of the Soviet elite, or rather part of it. Previously, the repression had been axed against the kulaks, the former underdog aristocrats, the clergy and the old czarist officers... but suddenly the machine of terror turned against... against its own creators. Yes, the uniqueness of the 37th repressions is that the executioners shot the executioners. Yagoda was followed by Yezhov, Yezhov by Beria. Here the figure of Khrushchev is interesting. He was directly involved in terror, but after Stalin's death, when he was already in power, he loudly condemned it. Following Khrushchev, many still view the "Great Terror" as the extermination of the elites - Party workers, engineers, soldiers, writers, etc. The number of victims was frightening for the Soviet nomenklatura. Officials literally trembled at every night knock, because the sword of the NKVD (execution or imprisonment in a camp) hung over everyone. There are 383 lists for the arrest and execution of 40,000 Soviet officials approved by the master of the Kremlin. The pinnacle of the system of destruction of the "nomenklatura" and the old Bolsheviks were the famous Moscow open trials against some prominent party members. The second part of the "great terror" was the so-called "mass operations''. It was these, encompassing over a million people, that made the terror of 1937-1938. "big". But it was the fact that the Party suffered from Stalinist terror that made its condemnation possible.As cynical as it may sound, Stalin did to the Party what the Party did to the Russian people for a decade. And the Party learned this lesson. It understood that personal dictatorship always leads to arbitrariness from which no one can defend them. This was a factor in the Soviet bureaucracy's attempts to rid itself of personalist dogma and move towards that very collective leadership. However, this would happen after Stalin's death on 5-th of March 1953, which brings us to the next part.

Collective leadership

According to historian Yuri Zhukov, a great expert on the subject, as early as the evening of March 3, some agreement was reached among Stalin's comrades-in-arms regarding the occupation of key positions in the party and the government of the country. Moreover, Stalin's comrades-in-arms began to share power, when Stalin himself was still alive, but could not prevent them from doing so. When doctors reported the hopelessness of the sick leader, comrades-inarms began to share portfolios, as if he was no longer alive.

Afterword

However, the Soviet Union had about 10 years to live.Adetailed analysis of the first two Brezhnev successors is unlikely to be of interest to the reader. It should only be said that power was entirely in the hands of the Politburo, which chose the General Secretary in the 1980s. However, the reader is surely aware of Gorbachev. The Soviet reformer, however, was in a wholly dictatorial mood, trying to exert total control over the party. His personnel policy was described by Jack Matlock, the US ambassador to the USSR, who said: "He only felt comfortable next to silent or grey ones..." In 1988, Gorbachev began the "rejuvenation" of the Central Committee apparatus. "Gorbachev's" were put on all key posts. However, this did not prevent a fierce polemic within the party about reform between conservative communists and reformists. Gorbachev's idealism and commensurate ambition, coupled with the presence of opposition to him at the top, culminated in theAugust 1991 putsch. Ironically, the reformer was confronted by a collective council of reactionaries who dreamed of a return to the Brezhnev era. It was perhaps the last example of collective leadership in the USSR’s history.

We can, however, recall Yeltsin and his conflict with the collective opposition in parliament. It all ended in a small civil war and the shooting of a parliament building. Many liberal historians in today's Russia consider 1993 (the year parliament was shot down and Yeltsin himself established a super-presidential form of government) to be one of the roots of Putin's dictatorship, as the collective majority again lost out to the leader. However, Yeltsin was far more dependent on his entourage, above all the oligarchs, than Putin. Just as in the early years of Soviet Russia, there was no stable model of power in the early years of the Russian Federation (except officially, but paperwork in Russia has always made little sense). Putin, on the other hand, began his rule by destroying the disloyal oligarchs and forming a system of government built around the president alone. The process was slow but reached its climax on 24 February. The lives of millions now depended on one man alone. The last time this kind of autocracy, coupled with military hysteria, led to a huge repression. Whether Russia will see a new 37th year and a purge of the upper classes is an open question…

Just following orders?

Examining the role of Radio Free Europe in The Hungarian Revolution - Piers Marchant

When the Hungarian Revolution began in Budapest in autumn 1956, the US had a key decision to make on how it should proceed. Should it promote the liberation of Hungary and actively propagandise and support the revolutionaries’desires, or should it continue its passive policy of containment and leave the freedom of eastern Europe to the eventual collapse of the Soviet system? Promoting liberation risked aggravating the Soviet Union into intervention in Hungary and included the potential for nuclear conflict. Passivity, however, could have been seen as a wasted opportunity to unravel the Iron Curtain. This is where Radio Free Europe (RFE) enter the fray. The mission of this US-funded radio station was to spread anti-communist propaganda throughout the communist world and to promote the ideals and political positions of the United States and US allies. During the Revolution, RFE’s objective was to strike a balance between supporting the desire of the Hungarian people for freedom and avoiding inciting armed struggle against the Soviet army. However, its success in this task has been the subject of considerable historical debate, as many historians such as Granville and Kissinger consider RFE to have been a major factor in encouraging continuation of armed uprising, whilst Ross Johnson and Holt disagree with this due to lack of evidence. To determine an answer to the question of RFE’s involvement, it must be divided into two. What were the guidelines and orders that RFE should have followed and to what extent did RFE obey these orders? Ultimately it is clear that RFE implicitly encouraged the Revolution’s continuation and explicitly abandoned the position of the US government by doing so.

RFE was founded in 1950 by the National Committee for a Free Europe (NCFE), a CIAfunded organisation founded in 1949. Its stated aim was “to transmit uncensored news and information to audiences behind the Iron Curtain”. As a result, RFE was transmitted to Soviet satellite states and within the Soviet Union. The early years of the radio station saw huge rises in funding from the US government and by the second half of the Cold War, RFE listening audiences in some Eastern European countries had increased to between 40 and 60 percent of their population. However, the turning point in RFE’s history came during the Hungarian Revolution.After the conclusion of the Revolution, stricter guidelines were put in place and RFE was far more limited in what it could broadcast, suggesting that RFE went beyond its permitted CIAregulations and published content which abandoned normal standards of journalism, inciting further rebellion. On 25 October 1956, Egypt nationalised the canal and it became clear that France, Britain and Israel were set to invade.American diplomats had to both condemn and maintain their relations with the invaders whilst also disavowing the Egyptian and Soviet methods in the crisis. This created a thorough diplomatic headache, as the US could not condemn one invasion into a fully recognised UN member state whilst also actively supporting a rebellion against another.

Therefore, it is easy to see why the United States held back from allowing RFE to freely act to entice the Hungarians to subvert the Soviet Union, since they simply did not have the capacity to deal with the responsibility of a widespread Hungarian revolt. RFE was effectively ordered to play a supportive, but ultimately peaceful role in the Hungarian Revolution, subverting the wishes of the Dulles brothers and many Hungarian freedom fighters too.

Scholarship around the role of RFE in the Hungarian Revolution often refers to the claim that RFE urged the Hungarians in a broad appeal to fight and declare independence from the Soviet Union, in violation ofAmerican instruction. Kissinger claims RFE “took it upon itself to interpretAmerican attitudes, urging Hungarians to step up the pace of their revolution and reject any compromise.” Pelchat agrees, saying “Radio Free Europe went beyond the directives and policies issued to it by Washington D.C. These broadcasts violated their directives from Washington by informing their listeners how to effectively engage in partisan warfare and disable tanks with limited supplies.” The main example showcasing this abandonment of standards, is a broadcast from Zoltán Thury, who gave this commentary on November 4th, about an Observer article on the developing situation in Hungary.

“The reports from London, Paris, the United States, and other Western reports show that the world’s reaction to the Hungarian events surpasses every imagination. In the Western capitals a practical manifestation of Western sympathy is expected at any hour.”

Giving this commentary on the day when Soviet tanks rolled into Budapest violates any journalistic standards of impartiality, in that it gives hope to the diminishing numbers of freedom fighters desiring help from the West. It is also a flagrant falsehood for Thury to interpret American policy this way when the US Department of State had made it clear that a “practical manifestation of Western sympathy” was not forthcoming. In addition, this statement is a clear violation of the guidance to RFE given just the day before. It also weakened America’s diplomatic position laid out in Dulles’October 29th speech where he said “the US has no ulterior purpose in desiring the independence of the satellite countries. We do not look upon these nations as potential military allies” as Thury seemingly did the opposite and directly promised or at least predicted a military alliance.

Some believe this to be evidence that RFE incited further revolution and promised Western intervention throughout the uprising.ASüddeutsche Zeitung editorial claims exactly this by saying “[RFE] encouraged [the Hungarians] with promises that the U.S. military would rush to their aid.” However, those who believe RFE did little to promote Western armed intervention, such as Holt, point to this broadcast as “the result of clumsiness rather than intent”, and that “this one press review is hardly grounds for the claim that RFE promised the freedom fighters thatAmericans would come to their aid”. There is merit to this observation, as one is hard-pressed to find other examples of an RFE broadcast being so explicit about the probability of Western intervention. Combined with the fact that Thury’s broadcast was made towards the end of the Revolution on November 4th, no factual basis can be made for the claim that RFE consistently and directly promised Western aid. While RFE may still have indirectly encouraged the Revolution through its broadcasts, the claim that RFE explicitly and invariably promised Western intervention is not supported by available evidence.

Whether through clumsiness or genuine intent, Thury’s broadcast nonetheless still broke CIAguidelines. In addition, there are also some notable instances of RFE going so far as to give direct tactical advice. In his “Armed Forces Special #A1” of October 27th, Julian Borsanyi gave “detailed instructions as to how partisan forces should fight” and “advised local authorities to secure stores of arms for the use of Freedom Fighters”. Borsanyi’s broadcast effectively changed RFE from a supportive but ultimately unaffiliated radio station into a logistical tool for coordination amongst the freedom fighters. This would stir the ire of both Moscow and Washington, as the Kremlin could accuse theAmericans of abetting the rebels, which would force Washington into a difficult position. In this way it can be said that RFE in fact weakened America’s international position during the Hungarian Revolution.

The answer to the question posed at the beginning of this section is a nuanced one. Whilst not going so far as to seriously promote Western intervention, it is most convincing to argue that RFE seriously disobeyed CIAadvice and therefore abandoned the diplomatic line pushed by theAmericans in favour of a more idealistic and far-reaching viewpoint through its proselytization of tactical advice and inflammatory commentary.An internal review of RFE broadcasts on December 3rd, 1956, supports this conclusion saying:

“The present programs of Radio Free Europe … which are principally based on a concept of encouraging the people to make demands of the regime for change … should be carefully examined.”

To come to this conclusion so soon after the end of the Revolution suggests that RFE strayed from CIAguidelines to such an extent that the US government would wish to amend the use of RFE for future conflicts.