Hamilton Historical

An Undergraduate Journal est. 2020

Volume III Issue II: Spring 2024

Peer-reviewed by Undergraduates for Undergraduates

Based out of Hamilton College, Clinton NY.

Volume III Issue II: Spring 2024

Peer-reviewed by Undergraduates for Undergraduates

Based out of Hamilton College, Clinton NY.

Volume III, Issue II

Spring 2024

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Quinn Brown

ASSISTANT EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Lara Barreira

Layout Czar

Jack Ritzenberg

Layout Czarevich

Mika Tortusa

Peer Editors

Miko Newman Nicole Mcdonough

Kloe Shkane John Sheets

Nick Fluty Katie Rao

Readers

Sam Minzter Ben Ingram

Helen Ziobrowski Allen Cao

Peter Hinkle Bennett Hauck Tim Murray

Dear Readers,

Welcome to our second issue of volume III of the Hamilton Historical. This issue will be my last as Editor-in-Chief of the journal but I am pleased to announce that Lara Barreira will be taking over as Editor-in-Chief for our next volume after serving as Assistant Editor-in-Chief this semester. Joining Lara in leadership will be Mika Tortusa who will take over for our esteemed Layout Czar Jack Ritzenberg. I want to give a special thank you to all of our Readers and Peer Editors who have worked prodigiously to create our issue.

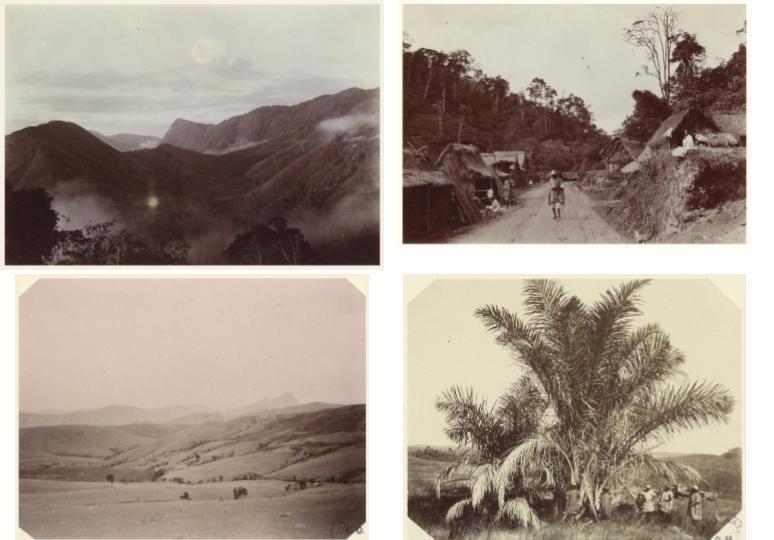

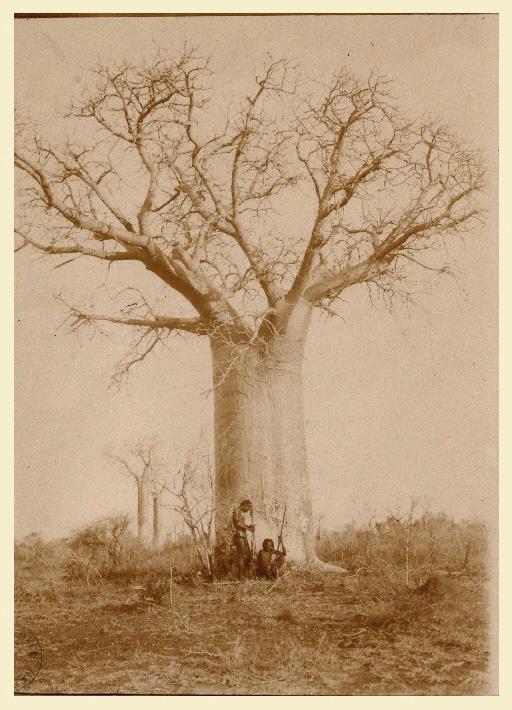

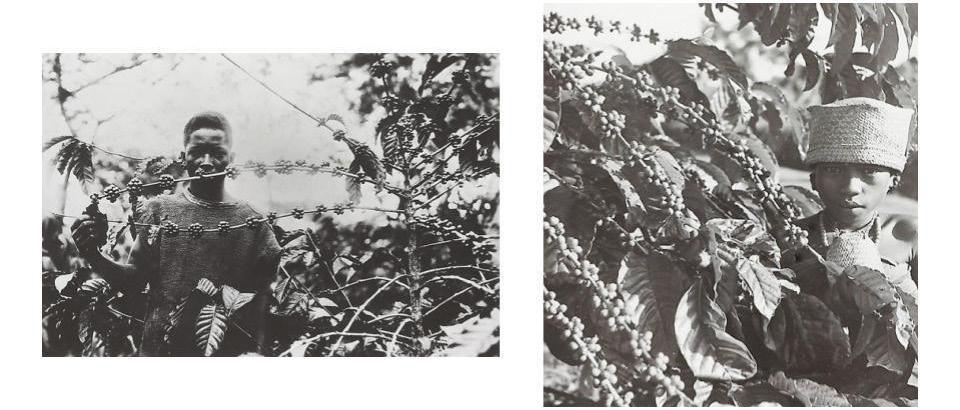

Since our establishment in 2020 we have made an effort to include a wide variety of historical scholarship from a range of our peer institutions as well as from our own Hamilton College. This issue is no different as our published pieces include research and historiography pieces ranging temporally from the Middle Ages to modernity. This issue will begin with an investigation of John Locke’s influence on English colonization in America from Meg Shelburne of Middlebury College. Next, Lara Barreira, our Assistant Editor-in-Chief, provides an analysis of Obeah magic. After that, we will turn to a historiographical discussion of race in theories of nationalism by Hamilton’s Jacob Piazza. A survey of the Animals of the Hereford Mappamundi by Alex Wilson of Carleton College will follow that. Our penultimate piece is an interrogation of French Photography in Madagascar by John Sheets of Hamilton. And wrapping up our issue is a discussion of the historiography of the Soldier-Symbol in America by Sumiko Newman also of Hamilton.

Thank you for continued readership and support of the Hamilton Historical.

Sincerely,

Quinn Editor-in-Chief, 2023-2024

John Locke’s Account of Property and 17th-Century English “New World” Colonialism

Meg Shelburne Middlebury College - Class of 2024

In his classic of Western political theory, Two Treatises of Government (1689), John Locke constructed an account of the origin and ends of government that centered above all on the protection of private property. The English historian Peter Laslett contends that the Two Treatises are most innovative in Locke’s justification of private property, in which individual labor provides the basis for the appropriation of common goods for private use.1 This grounding of private property in individual labor and the rights extending from self-ownership has traditionally encouraged scholars to situate Locke’s theory of property as a foundational idea of modern individualist capitalism. This idea has surfaced among 20th-century scholars as politically distinct as C.B. Macpherson, who indicted Locke’s “possessive individualism” as a foundation of the contemporary ills of capitalism, and Robert Nozick, whose Anarchy, State, and Utopia praised Locke’s account of property to advocate for a limited state and unfettered free market economy.2 Their more recent interpretations are the children of a long scholarly history that reads Locke’s property-centric liberalism within the natural law tradition, evaluating Locke’s theory of property as the product of 17th-century English philosophical contests over absolutism and monarchy. Over the last several decades, another powerful angle of scholarship has emerged that places Locke’s doctrine of property within another 17th-century context: English colonization in the Americas and the

1 Peter Laslett, “Introduction” in Two Treatises of Government, ed. Peter Laslett, Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1960), 101107.

2 C.B. Macpherson, The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1962); Robert Nozick, Anarchy, State, and Utopia (New York: Basic Books, 1974).

mercantilist world system. As European monarchies— the already-established Spanish, Portuguese, Danish, Dutch, and French, as well as the more late-coming English—attempted to assert their claims to “New World” territories throughout the 17th-century, justifications for property and land appropriation became increasingly contested.3 Locke himself stood in the middle of this contest: Locke’s extensive personal involvement in English colonial projects in the Americas has become evident over the last thirty years. Drawing on a wealth of previously overlooked biographical evidence, James Tully and Barbara Arneil make powerful cases for taking Locke’s numerous references to the Americas in the Two Treatises seriously as a defining feature of his theory of property rights. By foregrounding Locke’s personal involvement in English colonialism in the Americas, Tully and Arneil demonstrate how Locke’s account of property rights in the Second Treatise, which makes agricultural labor the basis for land rights and construes American lands as “vacant” or “waste,” can be read as a justification for the English seizure of Native American lands.4

This essay will extend Tully and Arneil’s reading of Locke as an essentially colonial and mercantilist thinker, closely examining how the need to legitimize English claims to Native American lands shaped Locke’s account of property. In particular, it will build

3 David Armitage, “Introduction” in Theories of Empire 14501800, (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1998); Anthony Pagden, Lords of All the World: Ideologies of Empire in Spain, Britain, and France c. 1500-1800 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995).

4 James Tully, “Rediscovering America: The Two Treatises and Aboriginal Rights,” in An Approach to Political Philosophy: John Locke in Contexts (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 137-76; Barbara Arneil, John Locke and America: The Defence of English Colonialism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996).

on Tully and Arneil by emphasizing the way that the competitive mercantilist context incentivized Locke to construct his definition of property in order to position the English colonial project as a preferable or admirable alternative to other forms of European colonialism in the New World, particularly the Spanish. Locke constructs his philosophical justification of property rights in a manner that exalts noninvasive English yeoman agriculture while invalidating Spanish “just war” or conquest-based forms of land appropriation. However, rather than accept Locke’s differentiation of English practices at face value, this essay will examine the inconsistencies between the vision of benign English occupation of “vacant” American lands that Locke lays out in the Two Treatises and the actual colonial practices in which he was involved. In this light, it becomes clear that Locke’s treatment of property endorses a vision of colonialism that fails to be fundamentally different from the Spanish vision. For one, Locke and the Spanish alike used the religiously defined “uncivilized” nature of the indigenous populations as a justification for seizing their lands and overwriting their ways of life. As such, Locke’s account of property should be recognized as broadly continuous with patterns of European justifications for American colonialism and implicated in that world-altering historical process.

As Tully and Arneil bring to light, Locke played a central role in the English colonization of North America, an experience which strongly shaped his work on property in the Second Treatise. Locke sat at vantage point from which he could observe nearly every facet of the American colonial project—David Armitage concludes that “by the time [Locke] resigned from the Board of Trade in 1700, he had become one of the two-best informed observers of the English Atlantic world of the late seventeenth century.”5 Locke was introduced to colonial matters in the late 1660s through the patronage of the highly influential Lord Shaftesbury, the leading proprietor of the colony of Carolina, an association which changed the course of Locke’s life and gave him the political expertise to write the Two Treatises. 6 As the secretary to Shaftesbury, to the Lord Proprietors of Carolina (1668-1671), and to the Council of Trade and Plantations (1673-1674) he helped draft the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina and attained enormous knowledge of the workings of the

5 David Armitage, “John Locke: Theorist of Empire?,” in Empire and Political Thought, ed. Sankar Muthu (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 90.

6 Laslett, Introduction to Two Treatises of Government, 26-27.

various English colonial projects.7 Later progressing to become a member of the Board of Trade (1696-1700), a Landgrave of the Carolina colony, and a stockholder in the slave-trading Royal Africa Company (1671) and Company of Merchant Adventurers to Trade with the Bahamas (1672), Locke made a number of significant contributions to shaping the colonial system in the Restoration period.8 While Locke writes primarily of Native Americans in Second Treatises’ discussions of property, his personal investment in the African slave trade was also substantial and worthy of notice. Regardless, Locke was privy to an enormous amount of detailed information about colonists’ interactions with Native Americans and the progress of colonial agriculture and settlement. The question of English property rights in the Americas was far from trivial for him: it had real and consequential daily ramifications for him. With this biographical information in mind, Locke’s repeated references to the Americas in the Second Treatise take on a much more important dimension, demonstrating the extent to which the Americas and Native Americans actually played a tangible role in his thinking on property rights. James Tully, followed later by Barbara Arneil, weaves together Locke’s colonial commitments with a close reading of Chapter 5—“On Property”—of the Second Treatise to argue convincingly that Locke bases property rights as he does on cultivation in order to justify English seizure of American lands.9 Locke’s investigation of property takes as its starting point the “Grants God made of the World” to humankind and then applies “Reason” to discover how individual property rights arose from this original state of communal goods and land.10 In so doing, Locke was operating within the 17th-century natural law debates on the origins of property that had been developed by Hugo Grotius and Samuel Pufendorf. But where Grotius and Pufendorf legitimize the development of private property through the notion of universal consent or agreement between individuals, Locke undertakes the task in Chapter 5 of explaining how property can

7 David Armitage, “John Locke, Carolina, and the ’Two Treatises of Government,” Political Theory 32, no. 5 (2004): 602–27.

8 Tully, “Rediscovering America: The Two Treatises and Aboriginal Rights,” 140-141.

9 Ibid.

10 John Locke, Two Treatises on Government, ed. Peter Laslett, Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1960).

begin without the need for consent.11 Locke’s “endeavour to shew, how men might come to have a property in several parts of that which God gave to mankind in common, and that without any express Compact of the Commoners” has been classically interpreted as a refutation of Sir Robert Filmer’s absolutist and monarchist arguments, Locke’s object in the entire First Treatise.12 However, establishing an alternative to property by consent also had critical implications for England’s colonial projects, which depended on occupying land without the express consent of the natives.

Locke’s chief innovation in finding this consent-free foundation for property rights was to make individual labor the basis of appropriation, which both serves to delegitimize native forms of property and exalt a specifically English agricultural model of colonization. Locke, as Macpherson noted in Possessive Individualism, bases the origin of property in self-ownership—“every man has a Property in his Person” — such that each man’s labor is his own property. By applying “the Work of his Hands…whatsoever then he removes out of the State that Nature hath provided and left it in, he hath mixed his Labour with, and joyned to it something that is his own, and thereby makes it his Property.”13 Locke identifies the“chief matter of property” as land rights. He argues that God “commanded [man] to subdue the Earth, i.e. improve it for the benefit of Life” by laboring upon it. Locke contends that this divine grant means that the individual who will most maximize the value of the land deserves to appropriate the land: “[God] gave it to the use of the Industrious and Rational, (and Labour was to be his Title to it;).”14 Locke contends that land has no value until cultivated—“let any one consider, what the difference is between an Acre of Land planted with Tobacco or Sugar, sown with Wheat or Barley; and an Acre of the same Land lying in common, without any Husbandry upon it.”15 This emphasis on cultivation implies that Native American communal land use fails to meet the

11 Barbara Arneil, “Colonialism and Natural Law” in John Locke and America: The Defence of English Colonialism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996).

12 Laslett, Two Treatises on Government, “Second Treatise”, Ch. 5, para. 25. Note by Peter Laslett.

13 Locke, Two Treatises on Government, “Second Treatise”, Ch. 5, para. 27.

14 Locke, Two Treatises on Government, “Second Treatise”, Ch. 5, para. 32-34.

15 Locke, Two Treatises on Government, “Second Treatise”, Ch. 5, para. 40.

“rational and industrious” standard laid out in the initial divine grant to mankind and therefore fails to meet the requirements of property rights.

Thus, by making agricultural labor and cultivation the hallmark of property rights and contrasting this with imagined Native American practices in the “state of nature,” Locke presents indigenous land use as a natural antecedent to inevitably be superseded by European cultivation. As Locke constructs it, indigenous Americans practice only a very limited form of individual property based on hunting and gathering: “Thus this law of reason makes the Deer, that Indian’s who hath killed it,” since “‘tis allowed to be his goods who hath bestowed his labour upon it.”16 This activity of the “wild Indian,” is identified as an example of primitive society before European ways of cultivation and commerce developed. Following up his example of the Native American appropriation of a deer, Locke explicitly excludes Native Americans from the group he terms the “civiliz’d part of mankind.”17 In his most famous phrase equating Native Americans to the state of nature, Locke insists that “In the beginning all the World was America,” making it clear that Locke sees America as a blank canvas for civilized development. By using agricultural labor as the standard of civilization, Locke creates a dichotomy where natives cannot resist its march: they either must adopt English practices or give their land over to the English.18 By equating cultivation and civilization, Locke positions the development of America along the lines of English agricultural practice as inherently desirable. Indeed, Locke uses this dichotomy between English “civilization” and Native Americans in the purported state of nature to label lands in the Americas as unoccupied and vacant, demanding English cultivation and colonization. He argues that “Land that is left wholly to Nature, that hath no improvement of Pasturage, Tillage, or Planting, is called, as indeed it is, waste.”19 Locke, describing how the invention and adoption of money in ‘developed’ societies had led to the age of property consumption unlimited by spoilage,

16 Locke, Two Treatises on Government, “Second Treatise”, Ch. 5, para. 30.

17 Ibid.

18 Barbara Arneil, “The Wild Indian’s Venison: Locke’s Theory of Property and English Colonialism in America,” Political Studies 44, no. 1 (1996): 60–74, https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb00764.x.

19 Locke, Two Treatises on Government, “Second Treatise”, Ch. 5, para. 42.

treats the Americas as an area where this inevitable and natural development has not yet taken place: “there are still great Tracts of Ground to be found, which (the inhabitants thereof not having joyned with the rest of mankind, in the consent of the Use of their common money) lie waste, and are more than the People, who dwell on it, do or can make use of, and so still lie in common.”20 Based on Locke’s aforementioned Puritan “rational and industrious” doctrine that God commands man to cultivate as much land as possible, the English settlers are essentially obligated to make use of these “wasted” lands for the good of mankind. As such, he combines his doctrine of hard-working English labor-based property and the insistence that America is wasted to create a subtle biblical mandate for English colonialism.

Locke’s labeling of America as vacant land and even as an uncultivated one was intentional, bordering on duplicitous. Locke was far from unfamiliar with Native American cultures, given his extensive exposure to news and literature from the colonies. Locke had even met and interrogated two Kiawahs from the Carolina colony who had traveled to England, an experience which influenced his conclusion in the landmark 1670 Essay on Human Understanding that Europeans had no exclusive cognitive or cultural superiorities.21 Besides the knowledge of native practices which accrued to him as the secretary of the Lord Proprietors of Carolina, Locke also had an impressive collection of colonial travelogues—over 195 titles, most of which describe trips to the Americas by European explorers like Sir Walter Raleigh and Richard Hakluyt.22 Locke clearly uses them to inform his concept of the state of nature throughout the Two Treatises, citing several throughout the First and Second Treatises—including, for example, Garcilaso de la Vega’s Commentarios Reales 23 Barbara Arneil concludes that “Locke was selective in the ‘facts’ he chose to include about them…what did not fit was ignored.”24 Most interestingly, Arneil notes that Locke’s exposure to colonial operations would have made him well aware of the fact

20 Locke, Two Treatises on Government, “Second Treatise”, Ch. 5, para. 45.

21 Armitage, “John Locke: Theorist of Empire?,” 88.

22 Barbara Arneil, “Locke’s Travel Books” in John Locke and America: The Defence of English Colonialism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996).

23 Locke, Two Treatises on Government, “Second Treatise”, Ch. 2, para. 14.

24 Arneil, “Locke’s Travel Books”

that natives cultivated the land and grew corn and other crops. English colonists in Virginia and Carolina depended on local populations for food and farming technology and Locke knew this.25 Locke’s insistence on describing American lands as vacant and uncultivated thus serves the purposes of his argument by making use of common misconceptions, rather than being the logical product of his actual expertise with colonial administration and Native Americans.

As such, the biographical evidence compiled by Tully and Arneil provides a convincing demonstration of the way that Locke’s exposure to the contest between Native Americans and the English for North American land shaped his thinking on the origins and foundations of property. Locke’s labor-based theory of property owes much of its inspiration to the nature of England’s agricultural North American colonies. However, the older historiography led by Macpherson and Nozick that makes Locke’s theory of property the origin of individualistic, small-government capitalism does not give credit to this essentially colonial and mercantilist bent of Locke’s individualism. Locke emphasizes small-holding, individualistic yeoman farming as the appropriate use of land in part because of the influence of the English colonial project on his thought: the need to justify the occupation of American lands, and, importantly, to elevate English colonial practices above those of other nations, including the French, the Dutch, and, above all, Spain.

Given Locke’s involvement in this mercantilist context, his labor-based theory of property owes as much to the need to formulate a ‘better’ justification for colonial appropriation than the Spanish and other European competitors as it does to natural rights theories about individual ownership. In the mercantilist, rather than purely capitalist, world economy of Locke’s day, both individual and national economic success was closely intertwined with national colonial power.

As John Tully argues in response to Macpherson, this “mercantile system” centered the nation rather than the individual as the beneficiary of colonial projects and appropriation of Native land.26 The state carefully oversaw and sponsored labor by English colonists in the Americas in order to bolster England’s position “in a zero sum, balance of power system of military and commercial rivalry with other European states over the

25 Ibid.

26 James Tully, “After the Macpherson Thesis,” in An Approach to Political Philosophy: John Locke in Contexts (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 137–76.

conquest, colonization, and exploitation of the non-European world.”27 Locke’s unpublished “Notes on an Essay for Trade,” prepared in 1674, makes this mercantilist mindset clear: “The chief end of trade is Riches & Power…Riches consists in plenty of Movables that will yield a price to a foreigner.”28 Throughout his assorted papers on trade and the colonies, Locke repeatedly tallies the economic benefits accruing to England from colonization in the internationally competitive mercantilist scheme, indicating the extent to which he saw his colonial project as in service of English power rather than individual capital gain.29

In Locke’s effort to distinguish English colonialism from its European competitors, he draws an especially strong contrast with Spanish conquest-based conceptions of property. The Spanish empire in the Americas loomed large over the politics of English colonialism. England had spent much of the 16th-century locked in a fierce rivalry with Catholic Spain.30 As Anthony Pagden writes, Spain’s 16th-century American conquests had made it the most successful and notorious of colonial powers: “only Spain had been able to carry out sustained and well-publicized conquests… marked down as one of the most appalling chapters in the history of human brutality.”31 The “grab and run” mentality of many conquistadores and the absolute devastation of the environment and native population via the encomienda and repartimiento systems of quasi-plantation slavery were well publicized by Spanish writers throughout the 16th and 17th centuries.32

Theorists of English colonialism, including Locke, had significant incentive to emphasize their differences with these publicly abhorred Spanish practices. Though Spain was far from its colonial heyday when Locke wrote the Two Treatises in the late 17th-century, it remained the pre-eminent colonial power in North America when the first English settlers arrived. Controlling much of the west as well as the Carolina-adja-

27 Ibid, 85.

28 John Locke, “Notes for an Essay on Trade” in Papers of Locke Relating to Trade and the Colonies, Oxford, Bodleian Libraries, Locke Manuscripts, 1671-1702, MS. Locke c. 30, folio 18.

29 Oxford, Bodleian Libraries, Locke Manuscripts, Papers of Locke Relating to Trade and the Colonies, 1671-1702. MS. Locke c. 30.

30 Timothy Paul Grady, Anglo-Spanish Rivalry in Colonial South-East America, 1650-1725 (London: Routledge, 2016).

31 Pagden, Lords of All the World, 4.

32 Pagden, Lords of All the World, 66.

cent colony of Florida. Spain posed a formidable threat to the late-coming English as they attempted to carve out their Atlantic dominions.33 As they had done in South America, Spanish Catholic missionaries in Florida used the “implied threat of the Spanish garrison” to convert the natives, a practice which the anti-Catholic English roundly despised.34 Though mercantilism provided a significant element of the competition between the English and the Spanish, the role of the Catholic-Protestant competition and the quest to convert native populations should not be underemphasized. To justify seizures of indigenous property that often amounted to little more than open theft and plunder, Spanish philosophers offered the idea that property was based on conquest or, at best, was the prize of a “just war.” They turned conquest into a “just war” by construing the natives as resisting civilization and thus damaging the overall welfare of mankind. Among the earliest philosophical justifications was Juan Lopez de Palacios Rubios’ 1512 requerimiento (“requirement”) argument that built on 15th-century papal grants of the American lands to Spain and Portugal to argue on a theological basis that Spain deserved to be the ruler of an immense global empire and promised hideous punishments to any natives that resisted this march of history.35 Indians were labeled as deserving of conquest given their purported resistance to the march of ‘civilization’ and thus to the overall good of humanity.36 Indeed, Locke takes square aim at these Spanish conquests and “just war” based justifications for the seizure of native property in Chapter 16, “On Conquest,” of the Second Treatise. He categorizes aggressive and unwarranted invasions as an illegitimate basis for property, noting that it “will be easily agreed by all Men, who will not think, that Robbers and Pyrates have a Right of Empire over whomsoever they have force enough to master.”37 His second, and more nuanced argument, is his self-described “strange doctrine” that even the victor of a “just war” “has not thereby a Right and Title to their possessions.”38 Locke supports a rejection of conquest-based property rights by claiming that it is because the costs to the conquered cannot be

33 Grady, Anglo-Spanish Rivalry, 2.

34 Ibid.

35 Pagden, Lords of All the World, 66.

36 Ibid, 97-100.

37 Locke, Two Treatises on Government, “Second Treatise”, Ch. 16, para. 176.

38 Locke, Two Treatises on Government, “Second Treatise”, Ch. 16, para. 180.

justified: “the destruction of a Years Product or two… is the utmost spoil that can be done.”39

Having thus rejected the Spanish “just war” argument, Locke reiterates his own waste-based view of the conditions in which land can reasonably be claimed: “where there being more Land than the inhabitants possess, and make use of, any one has liberty to make use of the waste,” reiterating his doctrine of peaceful English colonization of “vacant” lands rather than Spanish-style conquest and plunder. While this chapter on conquest was certainly also shaped by pressing European warfare, Locke’s curious attention to rehashing the contrast between cultivated and uncultivated lands demonstrates the extent to which his colonial concerns and interest in rejecting Spanish theories of property influenced him here as well.

Despite Locke’s insistence on rejecting Spanish-style practices in favor of a cultivation-based approach, he was basically splitting hairs: Locke and the proprietors praise themselves for improving on the Spanish model while still replicating the fundamental goals and practices of Spanish colonialism. Neither Tully nor Arneil fully reckon with Locke’s doctrine’s theoretical similarities and comparable consequences to the Spanish conquest-based project. Arneil largely accepts Locke and the proprietors’ attempts to differentiate themselves, emphasizing that “all of these perceived elements in the Spanish method of colonization—the lack of concern for the land, the refusal to recognize the rights of the Amerindians in terms of their lives and liberties, and the belief in colonization through conquest and the search for mines—were rejected wholeheartedly by the English colonizers.”40 She then goes on to suggest that Shaftesbury, assisted by Locke, even created Carolina as a contrasting model of this ethical, small-holding colony of freemen.41 Citing Locke and Shaftesbury’s advice to the governor of the colony in 1671 that suggested it would be more “advantageous” to pursue “Planting and Trade” instead of “rapin and plunder,” Arneil insists that Locke and the English colonists eschewed Spanish-style colonialism and actively sought to make ethical improvements

on the model.42

However, accepting this differentiation of the English and Spanish colonial practices ignores that even while trying to draw a contrast with Spanish abuses, Locke and the Carolina proprietors continued to construe Natives as remaining outside of civilization and operated under the same basic philosophical framework—America as a wasted divine grant that Europeans must make good on—as the Spanish. The Fundamental Constitution of Carolina, of which Locke was a principal architect, aims at a degree of tolerance but remains wedded to this basic Christian justification for land appropriation. It excludes non-Christians from landholding: “No man shall be permitted to be a freeman of Carolina, or to have any estate or habitation within it, that doth not acknowledge a God.”43 The constitution identifies the natives as these un-Christian men: “But since the natives of that place, who will be concerned in our plantation, are utterly strangers to Christianity.”44 Though the rest of the paragraph concedes that their “idolatry, ignorance, or mistake gives us no right to expel them or use them ill,” and advocates religious tolerance in the new colony for purposes of “civil peace,” it nods toward an improvement on the Spanish model fails to acknowledge a reality where indigenous practices were slowly but surely eradicated by Carolina colonists.45 In replicating the narrative of “civilized” Christians and the illegitimate “heathen” natives in the Fundamental Constitution, Locke’s doctrine echoed Spanish requerimiento logic even as it purported to condemn this. Locke’s agricultural appropriation hinged on the same basic justification as that of the Spanish: labeling the natives uncivilized and thus positioning the seizure of their land as a net benefit for mankind. While Locke’s characterization of labor as the defining feature of civilized land use masks this fact better than the “just war” doctrines of the Spanish, the basic effect of both remains the delegitimization of native forms of property use.46 Both doctrines—Prot-

42 Letter from Ashley to William Saile, 13 May 1671, written in Locke’s hand, Shaftesbury’s Papers, PRO Bundle 48, No. 55; Collections, 327–8. Cited in Arneil, “Carolina: A Colonial Blueprint,” 130.

43 “The Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina,” 1669, The Avalon Project, Yale University, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_ century/nc05.asp#1. Paragraph 95.

39 Locke, Second Treatise, Ch. 16, para. 184.

40 Arneil, “Carolina: A Colonial Blueprint,” in John Locke and America: The Defense of English Colonialism, 122.

41 Ibid

44 “The Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina”, Paragraph 97.

45 Ibid

46 Tully, “Rediscovering America: The Two Treatises and Aboriginal Rights,” 140-141.

estant and Catholic alike—invoked divine mandates for “civilization” and demanded the eventual forceful replacement of indigenous ways of life in order to generate European profit and glory, with devastating consequences for the indigenous.

The fact that the activities of the Carolina colony in practice departed substantially from his described ideal and mimicked Spanish practices further weakens Locke’s rhetoric around a uniquely English and moral type of land use. Despite Arneil’s insistence that the colony under Locke and Shaftesbury’s guidance prohibited “slavery in all its forms” in an attempt to differentiate itself from the Spanish, the Carolina colonists periodically practiced Native American slavery (as well as African chattel slavery), as Locke well knew.47 Indeed, in the mid-to-late 17th-century, the Carolina colony led the English Atlantic world in the scale and of the enslavement of natives.48 It is a well-known contradiction of Locke’s philosophical thought that Locke himself was personally invested in the African slave trade in the English Atlantic colonies—as noted above, he was a stockholder in the Royal Africa Company and Company of Merchant Adventurers to Trade with the Bahamas—even as he wrote ringing rejections of slavery in the Two Treatises. 49 In a similar vein, despite Locke’s rhetoric around the need to cultivate a peaceful relationship with native populations, the Carolina colonists did turn to “just war” and the enslavement of natives to further their colonial aims. For example, colonists provoked a series of wars with the neighboring Westo tribe between 1671 and 1685 and began a thriving trade in native captives.50 Though illegal, the practice was widely acknowledged and demonstrated the ethical vacancy of attempting to pursue a moderated or improved version of colonization. English ideals that purported to improve on the Spanish fell short in practice—regardless of rhetorical trappings and efforts around the edges to moderate the impact on Native Americans, the core underpinnings of the English project were equivalent to that of the Spanish: mercantilist national economic gain at the expense of the indigenous.

Finally, given the actual historical consequences for the natives of Locke’s supposed “admirable”

47 Arneil, “Carolina: A Colonial Blueprint,” 122.

48 Ibid, 65.

49 Wayne Glausser, “Three Approaches to Locke and the Slave Trade,” Journal of the History of Ideas 51, no. 2 (1990): 199–216, https://doi.org/10.2307/2709512.

50 Gallay, “Carolina, the Westo, and the Trade in Indian Slaves.”

alternative, his argument in the Two Treatises fails to mark any real ethical or intellectual improvement on the Spanish “might makes right” land seizures. As Domenico Losurdo discusses in his history of the ills of liberalism, Locke’s doctrine of American vacancy found its fullest expression via 19th-century proponents of the westward expansion of the United States, legitimizing both Andrew Jackson’s westward deportations of natives in the east in the 1830s and then later 19th-century wars of conquest against Western native nations.51

In the hands of admired liberal thinkers like Alexis de Tocqueville, Locke’s vacancy doctrine evolved into a theological mandate by God for the industrious white Americans to expand across the continent and make use of the lands—again, strongly reminiscent of and functionally equivalent to the arguments of the Spanish in South America over three centuries earlier.52 Regardless of the packaging of Locke’s property doctrine in its Puritan, individualist, and labor-centric values, its actual consequence—the eradication of indigenous ways of life—erodes the distinction between it and the conquest-based ideas that governed Spanish colonization. Though Locke laid claim to a more Puritan, industrious form of colonization and the global moral high ground for the English, his North American colonialism eventually resulted in comparable erasure of indigenous ways of life as in Spanish South America, if through a more drawn-out, long-term process. That such ethical baggage can be found attached to as central a doctrine of liberalism as Locke’s theory of individual labor-based property should be no surprise to any observer of liberalism’s history. Liberalism in the rear view is often marked by the tension between its lofty moral and ethical aspirations and the reality that the practical consequences of liberal doctrines often amount to little more than “might makes right.”53

As such, emphasizing the ways in which Locke’s treatment of property endorses a form of English colonialism—one that replicated the abuses of the Spanish land appropriation more than it avoided them—strengthens the line of scholarship begun by Tully and Arneil. Their work situating Locke’s doctrine of property in its appropriate mercantilist context and recognizing the strong influence of the contrast between Spanish and English colonialism does make important gains in addressing anachronistic treatments

51 Domenico Losurdo, Liberalism: A Counterhistory, trans. Gregory Elliot (Brooklyn: Verso Publishing, 2014), 230-233.

52 Ibid.

53 Ibid.

of his theory of property. However, it is important to extend their arguments by recognizing that Locke’s intended contrast with the Spanish belies a basic fact of the English colonial project: it fundamentally stands alongside other European colonial projects as their moral equals in its mercantilist goals and terribly destructive outcomes for indigenous Americans. While the particular shape and nature of Locke’s treatment of property in the Second Treatise is certainly innovative and worth appreciating in its own right, given these essential similarities, it should also be understood as part of a broader picture of early modern European rationales for colonialism. As such, Locke and his theory of property form a valuable piece of the 17th-century colonial landscape, with all the implications that contains for the colonial origins of the world economy and the virtual erasure of Native American society.

Lara Barreira Hamilton College - Class of 2025

The practice of healing, when pushed beyond the mundane and the ‘scientific’, becomes something like magic—the act of creating miracles through healing practices and ritual. The full extent of “healing,” for both body and soul, eclipses practices and concepts in modern medical vocabulary. It is difficult to historicize magic in the greater understanding of medicine and healing because ‘magic’ is more than material knowledge. Magic is a way of being and a social structure used to create an understanding of the world. Through an analysis of the historicization of Obeah, this essay will create “a conceptual space” that introduces the possibility of combining spiritualism, rituals, land, and politics to define Obeah in order to emphasize its role as a magical healing practice.1 I aim to define Obeah as a culture that exists beyond the constricting narratives of black magic or as a tool of resistance.2 Obeah instead represents the ways enslaved African people in the British West Indies engaged with their environment to create a culture of healing. In this paper, I will challenge the structures that historically have defined Obeah such as modern scholarship, legislation, and its societal perceptions, and bring it back to its “magic.”

“These are stories that did not wish to be told,” is how historian and professor Abena Dove Osseo-Asare describes her experience tracing traditional and oral

1 Diana Paton, The Cultural Politics of Obeah (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 21. In her book, Paton uses the phrase “conceptual space” to refer to a rift in the understanding of magic and the world.

2 Obeah is capitalized in this paper because I view it as a religious practice as well as a culture that deserves to be acknowledged as one. In most modern scholarship and leading historians like Diana Paton decided to use lowercase. However, there should be a conversation about whether Obeah should be capitalized like Vodou is. It raises the question of what practices deserve or do not deserve to be categorized as a singular concept.

knowledge in Africa.3 To write a contextualized history of the extraction of African plants, Osseo-Asare turned to oral histories and on-site research of pharmacies and communities. I could not travel to Jamaica to create an ethnographic study. For this reason, this paper uses only what is available to historicize Obeah and does not claim to be a history. Rather, this research aims to understand the healing culture of Obeah and how it has influenced science and medicine in the Caribbean. Much of the corpus used in this paper comes from English colonial archives, historical British texts, and the evident silence from the Afro-Caribbean community caused by centuries of British criminalization of Obeah and its practitioners.

To contextualize the British understanding of Obeah, I turn to modern scholarship to trace the historical transgression of Obeah in the Caribbean, paying important attention to weakening European authority and the existing stigmatization of Obeah. Historian Dipesh Chakrabarty reminds us, “Europe remains the sovereign, theoretical subject of all histories.’’ Osseo-Asare directly references Chakrabarty in her book, Bitter Roots, as a warning to historians to not depend on European epistemologies.4 I instead turn to historian Londa Schiebinger and agnotology, the study of culturally induced ignorance that serves to counterweight traditional concerns of epistemology to prevent the English colonial perspective from overwhelming a study of the true nature of Obeah.5 This paper is a transhistorical analysis of the culture of Obeah as it shapes,

3 Abena D. Osseo-Asare, Bitter Roots: The Search for Healing Plants in Africa (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), 7.

4 Osseo-Asare, Bitter Roots, 24.

5Londa Schiebinger, Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004), 3.

manipulates, and heals Afro-Caribbean society.

In the spring of 1760, Tacky, an enslaved man in Jamaica, led a group of 150 enslaved Africans from across the island to rebel against the British. What became “Tacky’s Rebellion” at Fort Maria quickly made the British realize the building unrest amongst the enslaved people, further emphasizing the immoral and destructive system of slavery. While the army managed to control the rebellion quickly, word of its occurrence and the development of other rebel groups subsequently spread anxiety across the British colonies. British planters discovered that Obeah was used to encourage the revolt; its rituals were used as a source of strength and protection for the African people.6 The English found out that an Obeahman started it all by convincing the enslaved people that his powers would make them invincible against the British. This Obeahman used his power and sorcery to strengthen the rebels, spreading the possibility of resistance across the West Indies.7 Cowed by Tacky’s Rebellion, various British colonies passed in ‘The Act’ criminalizing any use of Obeah before the year was out.8 This act put Obeah into a “conceptual space” engraved in Jamaican legislation inciting the spread of fear and distrust of the practice and those who interacted with it.9

During this period of increased anxiety around Obeah and rebellions, British scholars attempted to define the ambiguous practice of Obeah to further oppress the relationship between Afro-Caribbean people and the land they inhabit. Building on his experiences as a plantation physician from 1768 to 1778, Benjamin Moseley wrote A Treatise on Sugar about his understanding of Obeah and African people in the British West Indies. In this text published in 1800, Moseley began his section on Obeah by writing, “The Science of Obi is very extensive.”10 The science, as Moseley labels it, is the ways practitioners manipulate the material world to curse or to cure. Moseley’s book began to develop a concept of Obeah and brought clarity to the ambiguous nature of Obeah. When describing the people who practice Obeah, Moseley wrote, “The most

6 Diana Paton, “Witchcraft, Poison, Law, and Atlantic Slavery,” The William and Mary Quarterly 69, no. 2 (2012), 256.

7 Paton, “Witchcraft, Poison, Law’’, 256.

8 Paton, The Cultural Politics, 19.

9 Paton, The Cultural Politics, 21.

10 Benjamin Moseley, A Treatise on Sugar, with Miscellaneous Medical Observations, by Benjamin Moseley,... 2nd Edition (1800), 190.

wrinkled, and most deformed Obian magicians are most venerated,” associating age and perhaps wisdom with success within the practice of Obeah.11 Moseley began to link Obeah practitioners to the production of knowledge; whether of plants, their environment, or their situation.

British scholars demystified this bewitching phenomenon, referred to as “Obi”, to disrupt the individuality and preservation created by its development. By doing so, Obeah was transformed from its broader definition of sorcery into a racial term used to categorize African people as uncivilized. One of the first full monographs on Obeah, Obeah: Witchcraft in the West Indies by Hesketh Bell, recounts the oddly fascinating but, according to Bell, fabricated practice of Obeah. After interacting with Obeah, Obeahmen, and their rituals, he defined the practice as: “witchcraft, sorcery, and fetishism in general.”12 This definition, used widely after Bell’s publication in 1893, forced a practice that was beyond language to fit into a Eurocentric vocabulary. However, this oppressive definition fails to include Bell’s later acknowledgment that Obeahmen had “some skill in plants of the medicinal and poisonous species.”13 The brief mention of Obeah as more than witchcraft began to unravel the criminalized and racist understanding of the spiritual practice.

Many British texts briefly, if at all, hint at the extraction of medicinal knowledge from Obeah practitioners. In 1820, James Thomson wrote in his book, Treatise on the Diseases of Negroes as they Occur on the Island of Jamaica, “The intimate union of medicine and magic in the mind of the African is worthy the consideration of those interested in their welfare….”14 Thomson acknowledged the interwoven nature of medicine and Obeah to be one and the same. Disrupting preceding colonial narratives, Thomson’s acknowledgment spoke to the nature of Obeah practice as Afro-Caribbean people understood it. In Moseley’s book, he also describes an Obeah as a type of cure. He retells an experience where the Obeahman interrogated a patient to target the most “affected part of their body,” and from there they began to “torture” the patient with pinching, painting with gourds and calabashes, and pressing. After being nearly exhausted from being roughed up, the Obeahman would extract a rusty nail or piece of bone from the patient, and the “patient

11 Moseley, A Treatise on Sugar, 192.

12 Hesketh Bell, Obeah: Witchcraft in the West Indies (1893), 6.

13 Bell, Obeah, 9.

14 Thomson, A Treatise on the Diseases, 10.

is well the next day.”15 In this case, Obeah is not solely a ‘magical’ practice but also a sophisticated medical practice that can be used to heal people.

Despite undermining the influence of medicine in the practice of Obeah, Thomson, similar to Moseley, acknowledged its value. Thomson recommends plantation physicians to “derive useful information from the most intelligent amongst them.” He even confesses to applying the knowledge of enslaved people to his own “most labored prescriptions.”16 Although Obeah is not classified as a medicinal practice, implying the medical knowledge developed by enslaved African people legitimized Obeah medicine. In between the paragraphs and chapters on the racial differences between African people and the British, Thomson managed to preserve evidence of Obeah. More importantly, he preserved the possibility of its practice becoming part of British Caribbean pharmacopeias.

While not explicit, the influence of Obeah on Caribbean medicine can also be found within the descriptions of diseases. Historian Jeffrey Cottrell suggests Thomson’s section on labor and its discussion of the frequency of miscarriages, abortions, and infanticide amongst African women is evidence of the use of Obeah knowledge to cause them.17 Thomson writes that when young women “find themselves pregnant, [they] endeavor to procure abortion by every means in their power, in which they are too often assisted by the knavery of others.”18 While knavery may mean either the use of Obeah or disapproval of abortion, it is evidence of the women’s dependence on local knowledge to help young enslaved women abort children they did not want. The use of the word knavery is not enough to suggest this knowledge was Obeah, but it is enough to suggest how important local knowledge and obscure measures were to enslaved women. The ambiguity of knavery, like the ambiguity of Obeah, symbolizes the resilience of Afro-Caribbean people to hide knowledge from the British to preserve some control over their own lives as enslaved people. If it were only a type of “sorcery”, where does this acknowledgment of plant and medicinal knowledge

15 Thomson, A Treatise on the Diseases, 10.

16 James Thomson, A Treatise on the Diseases of Negroes, as They Occur in the Island of Jamaica: With Observations on the Country Remedies (1820), 10.

17 Jeffrey Cottrell, “At the end of the trade: obeah and black women in the colonial imaginary,” Atlantic Studies 12, no. 2 (2015): 212.

18 Thomson, A Treatise on the Diseases, 111.

come from? Furthermore, how does Obeah disrupt science and medicine in the Caribbean? It is strikingly apparent that the discussion of Obeah often obscures advancements in medicine and instead focuses on social constructions of political and autonomous identities amongst the Afro-Caribbean community. Print culture and its involvement in the colonial Caribbean worked against Obeah as it fetishized the practice. Obeah became another tool used to control enslaved people by denying their beliefs. The medicinal print culture of books like that of Moseley’s, Bell’s, and Thomas’s became part of a corpus that labeled and categorized Afro-Caribbean practices as simple superstitions. They are all shrouded in layers of racist ideology and narratives made to stifle the resistance amongst the African enslaved populations in the British West Indies. While their work inaccurately represents Obeah, they captured elements of healing even within the horrors of enslavement.

After the first legislation against Obeah in 1760, the British colonies began prosecuting anyone or anything associated with Obeah. Between 1760 and 1807, the British colonial government began to use Obeah to discredit Obeah. This transition meant Obeah shifted from a healing practice into one believed to cause sickness, poverty, and insurrections. Obeah was used to show how ‘foolish’ enslaved people were for believing in it.19 Once used to quell British anxieties over slave revolts, now colonial depictions of Obeah solidified racial hierarchy in Jamaica.20 Plantation owners found Obeah necessary to augment their authority in the Caribbean. This period marks the beginning of Obeah’s separation from its roots of healing and protection to the modern construction of Obeah as a cursed practice. Modern scholarship no longer defines Obeah the same way British scholars did in the 18th and 19th centuries. Historians are also fighting against the existing stigmatization of Obeah to prevent it from being forgotten. Historians Handler and Bilby suggest viewing Obeah “as a kind of neutral or positive spiritual force” to prevent stigma from overwhelming an understanding of Obeah.21 However, while historians do not necessarily need to define Obeah, they do create new boundaries for the term Obeah. Historians who discuss the prac-

19 19 Paton, The Cultural Politics, 19.

20 20 Paton, The Cultural Politics, 43.

21 J.S. Handler and K.M. Bilby, “Notes and documents - On the Early Use and Origin of the Term ‘Obeah’ in Barbados and the Anglophone Caribbean,” Slavery & Abolition 22, no. 2 (2001): 90.

tice attempt to contextualize the practice that allows for Obeah to become more than a taboo subject. Modern scholarship allows Obeah to once again, become a form of healing.

In Secret Cure of Slaves, Londa Schiebinger uses 18th-century physicians’ texts to depict healing in Obeah as a European cure. She constructs her understanding using physician texts that preserved Obeah’s healing practices but renamed them as a European cure. She argues that plantation physicians had the most contact with enslaved people, allowing them to understand what Obeah was. However, physicians discredited Obeah by calling it a part of the “African mind” to discourage respect towards practitioners. Most interestingly, physicians simultaneously began to implement Obeah-like practices into their treatments.22 European physicians also relied on the patient’s imagination, or “medical faith,” as part of their treatment.23 This faith convinced the body that it will get better; the same belief patients have as they enter modern-day clinics. The so-called African “superstitions” undermined in colonial texts became European “imaginations.”24 Slowly, this overlap between European medicine and Obeah practices became part of the same “cure.” In other words, Schiebinger begins to bridge the divide caused by the oppression of Obeah and African people.

Diana Paton, in The Cultural Politics of Obeah, rebuilds the relationship between the Caribbean people and Obeah broken by British colonialism. She uses British legislation against Obeah and trial records to extract the true nature of the practice. Instead of defining Obeah, Paton constructs an understanding of Obeah that pushes against the boundaries of only being a form of resistance. Through this framework, Obeah is understood as a product of the “cultural, political, and social effects of the consolidation of that term.”25 With time, Obeah became mutually reproduced by the enslaved population in the English West Indies and the colonial authority who acknowledged its existence.26 On the one hand, scholars must define Obeah to recognize it, and on the other, through this definition, Obeah becomes captured in another Eurocentric category. On

22 Londa Schiebinger, Secret Cures of Slaves: People, Plants, and Medicine in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World (Redwood City: Stanford University Press, 2017), 125; .Thomson, A Treatise on the Diseases, 9.

23 Schiebinger, Secret Cures, 125.

24 Schiebinger, Secret Cures, 126.

25 Paton, The Cultural Politics of Obeah, 3.

26 Paton, The Cultural Politics of Obeah, 3.

the other, to extract the medicine from within Obeah is to ignore and wrongfully reject its cultural and political significance. Either way, the influence of Obeah continues to affect Caribbean culture and life.

27

Through trial records, Paton finds that Obeah was not exclusively a form of sorcery. Instead, Obeah was naturally a “ritual complex created by, for, and about people on the move.”28 Practitioners preserved the practice of Obeah as they moved to different colonies or plantations, and as they died. Practitioners were infrequently released after their imprisonment, and so Obeah had to be adaptable to those who used it: the enslaved Afro-Caribbean people as they moved across various forms of oppression. Paton finds that Obeah includes aspects of African traditions and Christian practices. In the trials, “Christian ritual, language, and iconography,” and the Bible were part of the rituals performed by persecuted Obeah practitioners.29 The relationship practitioners had with Christianity was similar to their relationship to African traditions. Obeah is a product of how the Afro-Caribbean population consolidated their identities in relation to Europeans. Benjamin Breen proposes a new analytical lens when looking for the healing qualities of Obeah. He considers the two monoliths of African healing and European medicine to always stand at odds/ This dichotomy results in incorrect assumptions that both should be separated.30 Breen argues that Caribbean healing created a social pharmacopeia of its own, although it was discouraged to create a network of knowledge. Social pharmacopeia, a term coined by historian Pablo Gomez, is defined as a pharmacopeia developed in sociocultural spaces by the experiences and local knowledge of the Caribbean people.31 Healers in the colonial Caribbean held onto vast amounts of knowledge specific to their local areas but also learned from the transient space to which they belonged. As Breen proposes, instead of defining Obeah as only a religious practice or form of sorcery, Obeah can be seen as a social pharmacopeia that preserved knowledge and is informed by European and African practices. As a social pharmacopeia, Obeah may have developed a different type

27 Paton, The Cultural Politics of Obeah, 316.

28 Paton, The Cultural Politics, 211.

29 29 Paton, The Cultural Politics, 211.

30 Benjamin Breen, “The Flip Side of the Pharmacopeia,” Drugs on the Page, 2019, 156.

31 Pablo F. Gómez, The Experiential Caribbean: Creating Knowledge and Healing in the Early Modern Atlantic (Chapel Hill: UNC Press Books, 2017), 144.

of authority that complicates the ways historians have used it so far.

If Obeah is its own authority, then like science, it can also have experts. Obeah created a space for practitioners to use their understanding of medicine and herbal remedies to become experts in healing. Historians Handler and Bilby trace the origins of Obeah in a better attempt than Hesketh Bell, observing that “Obia” is a variant of the Efik or Ibo word that simply means “Doctor.”32 But, the term doctor constricts the complex relationship between healing and Obeah. Handler and Bilby break down the word even further and observe that the originating word “Dibia ‘’ or “Doctor,” Di can mean ‘husband,’ adept, or master, while Obia can mean knowledge and wisdom. Essentially, Obeah means the master of knowledge. Thus, using Obeah in a broader sense means using the knowledge developed by the experts in the field.

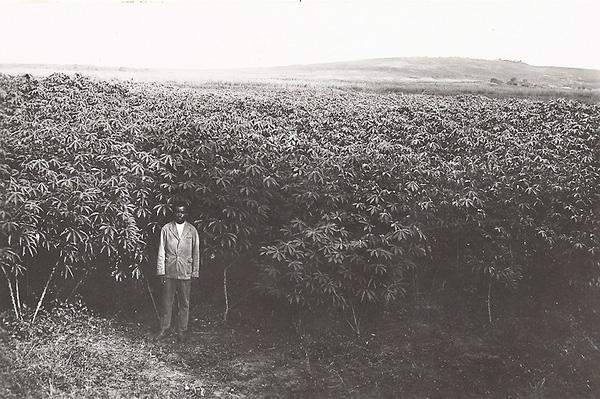

Seeking help from a practicing Obeahman was complicated; just as easily they could perform miracles, they could cause illness.33 Hesketh Bell’s Obeah describes the use of a curse called “Dressing the Garden”.34 In this ritual, Bell observed that a planter friend of his needed to prevent the theft of these crops, and as a last resort, he turned to an Obeahman named Mokombo. Mokombo tied “small and large vials” to the crops, muttered an incantation accompanied by the movement of his arms, and ceremoniously placed a small coffin with water and an egg to finalize the curse over the garden.35 Mokombo cursed the garden so that any thief would be attacked by “criboes” or evil black serpents. While Mokombo cursed the crops that may have been the source of food for people of his own community, the use of Obeah is not so straightforward. As an expert in Obeah, Mokombo successfully established a relationship with the European planter that went beyond the one between an enslaved person and an enslaver. The planter acknowledged and legitimized Mokombo’s skills by asking for his help to resolve his problems and establishing a reciprocal relationship. After the curse was done, the planter paid Mokombo five dollars in exchange for the spells used. Mokombo’s expertise in Obeah allowed him, for a moment, to be equals with the planter. Obeah, in that instance,

32 Kenneth M. Bilby and Jerome S. Handler, “Obeah: Healing and Protection in West Indian Slave Life,” The Journal of Caribbean History 38, no. 2 (2004):91.

33 Bilby and Handler, “Obeah: Healing”, 160.

34 Bell, Obeah, 3.

35 Bell, Obeah, 3.

became just as important as any European structure. In other words, Obeah practitioners used their knowledge of plants and sorcery as weapons of resistance against the tyranny of colonials.36 For the Afro-Caribbeans, practitioners, and the British colonizers, Obeah developed into an epistemological authority that withstood efforts to be stigmatized and undermined as a superstition.

The persistence of Obeah in Caribbean culture reveals what the practice actually is: the authority to manipulate the spiritual and material world. Diana Paton refers to historian Vincent Brown’s analysis of Obeah, he argues that Obeah is an “alternative authority and social power.”37 The authority combined with its ambiguity allowed Obeah to become part of Caribbean life and culture in a variety of ways. Obeah could only exist in a space like the Caribbean because the people who were forcibly relocated and enslaved used their understanding to reflect and grow from their transient experiences. The ambiguity of Obeah, in other words, established a legitimate authority of knowledge. As an authority of knowledge, Obeah influenced the ways Afro-Caribbean practitioners established credibility in the Caribbean. Spiritualists with extensive herbal knowledge became “Obeahmen” or “witch doctors.”38 To compare it to science, these historical actors became important cultural and societal figures that brought legitimacy to the institution of spiritual healing. The obscureness of the practice and its connection to magic established a new authority as important as any European one. In the Caribbean, the African traditions of using herbs and plants for healing and the European traditions of magic and witchcraft were interwoven. Obeah is the culmination of these exceptional epistemologies condensed and framed by a nuanced understanding of the world.

However, only looking at the authority of Obeah fails to fully explain the relationship between folk medicine and practitioners. The knowledge of these remedies demands that Obeah is seen as more than an ambiguous practice. To reference British physician Benjamin Moseley once again, Obeah is considered a

36 Arvilla Payne-Jackson and Mervyn C. Alleyne, Jamaican Folk Medicine: A Source of Healing (Saint Andrew Parish: University of West Indies Press, 2004),134.

37 Paton, The Cultural Politics of Obeah, 316.

38 I use witch doctors to imply that Obeahmen and women were not necessarily using only medicine, they used rituals and spells to heal as well.

practice of science.39 Stephan Palmié, a historian with training in anthropology, engages in very similar questions to the ones asked in this paper. In his book, Wizards and Scientists, Palmié believes that Obeah and science are more similar in practice than one might think.40 He extensively quotes anthropologist Donald Hogg’s article titled “Magic and ‘Science’ in Jamaica” to interrogate the relationship between Obeah and science. Hogg believes that what is called “‘magic’ is not necessarily mere superstition, but may be the product of intelligent, careful searching for knowledge”.41 This appears in the examples of Mokombo’s curse, the use of local remedies for abortion, and the Obeahmen who healed injuries. Hogg struggles with the use of “magic” because it also becomes a source of stigma. To him, defining Obeah as science allows the culture of Obeah to be respected.

The word magic holds so much authority that it completely overwhelms any understanding of Obeah. Any association with magic will immediately cause skepticism or credibility because of the stigma surrounding it. However, Hogg observes that “magicians” go through a similar process to that of scientists as they “work sincerely” and look for ways to improve their practice. “Obeahmen,” Hogg concludes, “may be scientists too.”42 Yet good intention and work ethic are not enough for Obeah to be called science. To answer this question, Hogg proposes that Obeah men also have “suspicious attitudes which motivate their skepticism and experimentation” the same way scientists do. He even suggests investigating labs because there is a possibility that “some of them may turn out to be Obeah men.”43 If a scientist or doctor were told their practice is like Obeah or Vodou, it would destroy their careers. It also suggests that science is not a sterile practice exclusive to its methods and laws. Instead, the scientific way to understand the world must be questioned. Perhaps, interrogating Obeah across various physician texts allows historians to realize that magic and its practitioners actively contradict and challenge tradi-

39 Moseley, A Treatise on Sugar, 190.

40 Stephan Palmié, Wizards and Scientists: Explorations in Afro-Cuban Modernity and Tradition (Durham: Duke University Press, 2002), 207.

41 Palmié, Wizards and Scientists, 208. Donald W. Hogg, “Magic and “Science” in Jamaica,” Caribbean Studies 1, no. 2 (July 1961): 5.

42 Palmié, Wizards and Scientists, 208.; Hogg, “Magic and “Science”, 5.

43 Hogg, “Magic and “Science”, 5.

tional science. While it is optimistic to think science can be easily challenged, Obeah cannot replace science. I was recently asked how I would respond if someone were to say science that is like magic is not true science. I ask then, why is there a need to categorize one over the other? Is the development of knowledge limited to only one practice? Just as Hogg frames it, what if Obeah is considered a science? Then, should any evidence of sorcery and spiritualism be considered as empirical evidence to understand the way the world works? Yes! Obeah is a practice that has demonstrated through centuries that it is not only a symbol of resistance, extensive knowledge, a culture, or a crime—Obeah is inexplicably magical in its ambiguity. Defining Obeah in any other way will be just as harmful as the laws that have originally banned it. Perhaps, Obeah is, after all, the magic of healing.

Jacob Piazza Hamilton College - Class of 2024

In 1983, Ernest Gellner wrote Nations and Nationalism. This work marked the commencement of an increase in literature on nationalism that took on an interdisciplinary nature including scholarship by political scientists, anthropologists, and historians. Three of these authors, Gellner, Benedict Anderson, and Partha Chatterjee formulate theories on nationalism that progressively totalize less and move from a primary political and economic focus to a more social-cultural approach. However, These theories do not implicate nationalism in racism and race. Then, in 1995, Prasenjit Duara wrote Rescuing History from the Nation, in which he rejected totalizing theories of nationalism. Instead, Duara connected 19th-century ideas of race to nationality through intellectual history and Foucauldian post-structuralism, which argues against attempting to generalize historical phenomena. Examination of these methodological and racial trends in the context of George Stocking’s study of 19th-century anthropology, the works of Frantz Fanon, and 19th to 20th-century African American literature reveal that this early canon of nationalistic theory insufficiently addresses relations between nationalism and racism.

Gellner and Anderson, both writing in 1983, approached nationalism through a primarily totalizing political and economic lens. Gellner’s work, Nations and Nationalism, relies heavily on analysis of the transition of society from agrarian to industrial; he claims his explanation that “mankind is irreversibly committed to industrial society” represents “the most important steps in the argument” about nationalism.1 This economic and partially social argument shifts towards a more political and cultural one when he explains his typology of nationalism which defines the emergence

1 Ernest Gellner, Nations and Nationalism (Hoboken: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2006), 38.

of nationalism based on access to education, culture, and power. Additionally, in his introduction, Gellner defines nationalism as “primarily a political principle, which holds that the political and national unit should be congruent.”2 Here, Gellner lays out his political approach to nationalism and emphasizes his totalizing interpretation of nationalism through this relatively un-nuanced definition. This tendency towards totalization also appears in his typology, which argues that there are only three types of nationalism, as well as his overemphasis on the Industrial Revolution’s impact.3 Thus, Gellner uses economic and political analysis to create absolute claims that overgeneralize.

Anderson’s Imagined Communities continues this pattern of economic and political analysis tempered by cultural and social influences. For Anderson, cultural changes in language, monarchical legitimacy, and conceptions of time permitted the emergence of nationalism. Each of these relates to economic and political analysis. However, Anderson focuses specifically on the economic and political factors of print capitalism and creolization. He contends that the effects of print capitalism created “the embryo of the nationally imagined community” and that creole functionaries’ “consciousness of connectedness,” which grew from local travel, provided the basis of nations in the Americas.4

In the second edition of his work, he examines the political aspects of the colonial state—census, map, and museum—which made possible nationalities such as “Burmese” and “Indonesian.”5 Early on, he defines nations as “an imagined political community—and

2 Gellner, Nations and Nationalism, 91.

3 Gellner, Nations and Nationalism, 91.

4 Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities (New York: Verso, 2016), 44, 56.

5 Anderson, Imagined Communities, 185.

imagined as both inherently limited and sovereign.”6 Through this definition and his use of “imagined,” Anderson acknowledges a cultural/intellectual aspect of nations, but assigns the possibility of their imagining to the distinctly political features of borders and sovereignty. This strict definition, along with his original primary focus on print capitalism and creolization, mirrors Gellner’s totalizing nature. Thus, Anderson’s investigation of the nation centers itself on economic and political factors, even as it accepts some cultural and social impacts.

Following this 1983 moment, Chatterjee’s 1993 book, The Nation and its Fragments, moves away from totalizing tendencies and leaves political and economic analysis behind for a primarily social and cultural examination. Chatterjee desires to “break down the totalizing claims of a nationalist historiography,” but contradicts this when he states that he hopes to create a “conceptualization of a new universal idea.”7 Additionally, he references Michel Foucault, whose historical genealogy characteristically refuses to totalize.8 Thus, he attempts to move away from totalizing assertions but still aims for universalism. Furthermore, Chatterjee’s reliance on colonial difference and emphasis on the colonized population’s creation of an independent domain of sovereignty represent different forms of the narrow totalizing thought that Gellner and Anderson use. Essentially Chatterjee relies on colonial difference in the same way that Gellner relies on industrialism to explain nationalism. However, Chatterjee differs from Gellner and Anderson in his focus on cultural and social history. His discussion of the inner/spiritual domain of sovereignty and Bengali “social agency” under British colonial rule exemplifies this, along with his scrutiny of the biography and vernacular plays of Sri Ramakrishna, a 19th-century Bengali religious leader.9 Therefore, Chatterjee begins a move away from Gellner and Anderon’s totalizing political and economic methodologies.

Duara completes this departure from Gellner and Anderson in Rescuing History from the Nation, in which he commits himself to Foucault’s anti-totalizing genealogical method and focuses on intellectual history. He claims that “nationalist consciousness is not… a unique… mode or form of consciousness,” to decon-

6 Anderson, Imagined Communities, 6-7.

7 Partha Chatterjee, The Nation and Its Fragments (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993), 13.

8 Chatterjee, The Nation and Its Fragments, 15.

9 Chatterjee, The Nation and Its Fragments, 35.

struct the totalizing arguments of previous thinkers.10 He then explains that “it is important for [his] analysis to firmly grasp [Foucault’s] reworking of ‘genealogy’ as a way to disrupt the continuum of traditional history.” Foucault’s genealogy helps him to “understand history as simultaneously dual or bifurcated movement of transmission and dispersion.”11 With this declaration of methodology, Duara asserts the anti-totalizing character of his approach. Furthermore, he continues to differentiate himself from previous scholarship with his focus on intellectual history. Thus, Duara breaks from Gellner and Anderson completely in his movement to a Foucauldian anti-totalizing genealogy and an intellectual analysis of nationalism.

George Stocking’s intellectual and post-structuralist approach towards the history of anthropology, in 1968 with Race, Culture, and Evolution and, in 1987, with Victorian Anthropology, aligns with Duara’s methodologies. In the earlier of these books, Stocking expresses dissatisfaction with linear progressive modes of history that act as “chronicles of an incremental process.” He references Thomas Kuhn’s emerging post-structuralist perspective which “does encourage us… to see historical change as a complex process of emergence rather than a similar linear sequence.”12 In Victorian Anthropology, Stocking formalizes his post-structuralist approach with references to Foucault’s interpretation that “the human sciences… are the product of a radical rupture at the end of the eighteenth century” along with his own “multiple contextualization.” Kuhn informs this method which attempts an “augmentation of context beyond that normally attempted.”13 Thus, Stocking’s process appears distinctly anti-totalizing in its post-structuralist Foucauldian tendencies. This similarity to Duara continues in his focus on intellectual history. Both of Stocking’s books trace the history of anthropology through texts written by anthropologists. Stocking’s and Duara’s intellectual and anti-totalizing approach contributes to a critique of the late 20th-century moment of nationalist historiography based on a lack of scrutiny of race. Stocking’s intellectual history and multiple contextualization reveal connections between race

10 Prasenjit Duara, Rescuing History from the Nation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), 7, 8.

11 Duara, Rescuing History from the Nation, 71.

12 George Stocking, Race, Culture, and Evolution: Essays in the History of Anthropology (New York: The Free Press, 1968), 7, 8.

13 George Stocking, Victorian Anthropology (New York: The Free Press, 1987), 30, xii, xiv.

and nation in scholarly thought during the 19th-century. Firstly, both of Stocking’s works establish the wide array of racist beliefs in the 19th-century. These ideas range from monogenist social degenerationism, polygenism, physical anthropology’s racial formalism, and after 1850, social Darwinism, eugenics, and sociocultural evolutionary ideas. This prevalence of racist views among Europeans in the 19th-century, the same period that nationalism developed in Europe, suggests that nationalist theories ought to concern themselves with race. Additionally, Stocking’s research uncovers a direct link between anthropological racial thought and European policy. In his discussion of Henry Maine, an English jurist, he explains how Maine wanted to discover “a truly scientific jurisprudence… by penetrating the history of the primitive societies.’”14 This exemplifies how anthropological racial convictions influenced European state policy. Later on, Stocking reaffirms this when he claims that “there can be no doubt that sociocultural thinking offered strong ideological support for the whole colonial enterprise in the late nineteenth century” through its argument that “savages were… racially incapable.”15 Stocking qualifies this belief with the example of how a colonial official “attempted to apply Mainian principles to the government of Fiji.”16 Thus, Stocking’s intellectual analysis, put into context with the nationalist upheavals of the 19th-century, reveals a direct relationship between race and the state structures from which nationalism emerged in the colonial and European world.

Furthermore, within a discussion of these racist ideologies, Stocking’s mentions of nation suggest a significant connection between race and nation. Twice in Race, Culture, and Evolution, Stocking implies a direct link between race and nation. This first appears in Citizen Degerando’s, a French Revolutionary era intellectual, belief that “the ‘traditions’ of the savages… could ‘cast a precious light on the mysterious history of these nations.’”17 Later, Stocking argues that his research on polygenist thought in post-Darwinian anthropology has “ramifications” that “should be followed into… nationalism.”18 This illustrates Stocking’s belief that race and nationalism possess inherent connections. Therefore, Stocking presents an awareness of race’s significance to nationalism which reveals itself

14 Stocking, Victorian Anthropology, 122.

15 Stocking, Victorian Anthropology, 236-237.

16 Stocking, Victorian Anthropology, 236.

17 Stocking, Race, Culture, and Evolution, 26.

18 Stocking, Race, Culture, and Evolution, 26,44.

through his intellectual analysis of anthropology. Additionally, Stocking’s exercise in intellectual history uncovers that 19th-century thinkers often used race and nation either interchangeably or exclusively, and rarely with separate meanings. Stocking explains this exclusivity in the anthropological transition from the use of nation to race as the terminology to denote ‘savage’ people. Degerando represents the tail-end of anthropologists who defined the savage nationally, in which “different savage groups were always ‘peoples’ or ‘nations’—never ‘races.’”19 He later illustrates how in post-Darwinian thought “the adjectives ‘savage’ or ‘barbarous’ or ‘uncivilized’... were now applied to ‘races’ rather than ‘nations’ or ‘peoples.’”20 Through this, Stocking exposes how anthropologists defined nation more socially than politically such that they could—and would—easily replace nation, with race in a post-Darwinian milieu. Therefore, Stocking establishes that throughout the 19th-century, European thinkers used race and nation at times exclusively, but in these exclusive works for the same purpose. This reveals an inherent connection between the terms throughout academia that suggests that scholars cannot understand one term without understanding its relation to the other.