An

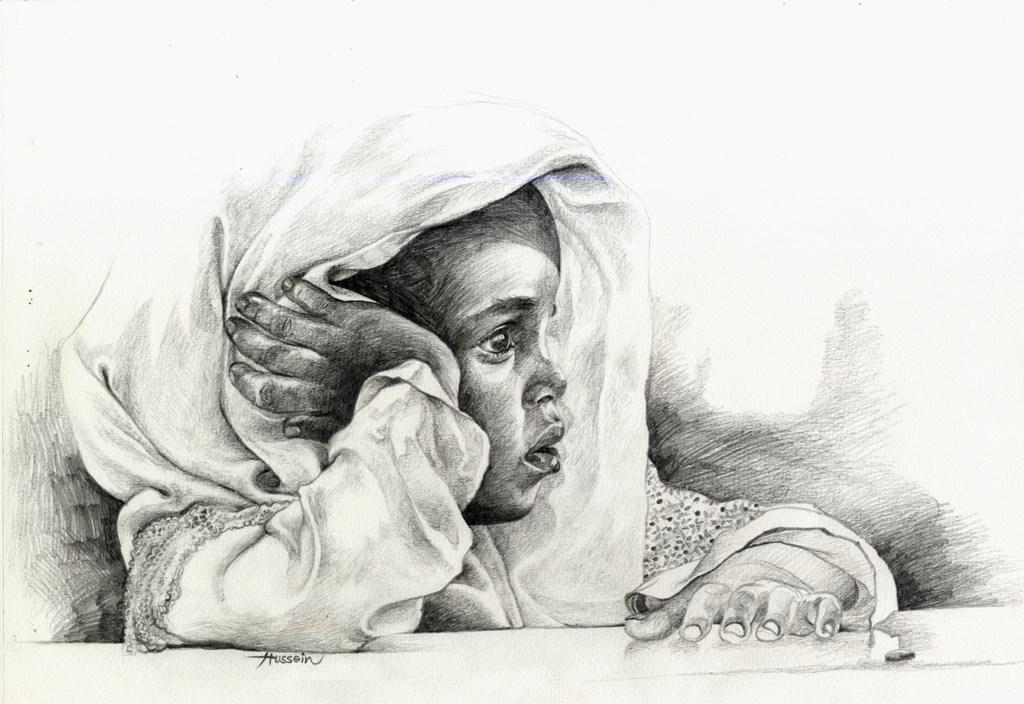

Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) continues to be one of the most widespread and deeply rooted human rights violations affecting women and girls in Somalia. With an alarming prevalence exceeding 99% among women aged 15 to 49, FGM is nearly universal in Somali society, making it a country with one of the highest rates globally. The practice is often perceived as a necessary rite of passage, essential for maintaining social acceptance, preserving chastity, and ensuring marital prospects. It is also wrongly justified by many communities as a religious obligation, despite the absence of any theological foundation for FGM in Islamic doctrine. This dangerous blend of cultural entrenchment, societal pressure, and misinterpreted religious beliefs has allowed the practice to persist across generations, with little challenge to its legitimacy in many communities.

The prevalence of FGM in Somalia is symptomatic of a broader systemic failure to protect the rights and bodily autonomy of women and girls. Despite a constitutional provision that denounces FGM as “cruel and degrading, tantamount to torture,” there is still no national criminal law explicitly prohibiting the practice. This legal vacuum allows FGM to continue with impunity, compounded by weak enforcement mechanisms and an absence of political will to pursue prosecution or accountability of the perpetrators. Moreover, societal reluctance to abandon harmful traditional practices, combined with limited education on the physical and psychological harms of FGM, further exacerbates the challenge. In regions where legal or religious fatwas (decrees) have attempted to curb the practice such as Puntland, Somaliland, Galmudug, and Jubaland, the results have been

mixed, with fragmented implementation and inconsistent follow-through.

Somalia’s engagement with international human rights frameworks has also been hesitant and incomplete. While the country has ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT), signed or expressed intention to ratify instruments such as the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, on the Rights of Women in Africa (the Maputo Protocol) and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACRWC), it has failed to fully domesticate these commitments into binding national law. This ambivalence reflects deeper structural resistance to reforms that advance women’s rights and challenge longstanding gender norms.

Somali Women’s Rights Organizations (WROs) have emerged as vocal and influential advocates against FGM. These grassroots organizations have worked tirelessly to mobilize communities, raise awareness about the dangers of the practice, support survivors, and engage religious leaders to dispel myths around FGM’s supposed Islamic origins. One of the most notable achievements of WROs advocacy has been the drafting of “the Anti-FGM Bill.” This proposed Bill aims to criminalize all forms of FGM, provide legal protection for survivors, and establish preventive and rehabilitative measures countrywide if enacted. The draft law represents a significant milestone in the fight against FGM and is widely welcomed by human rights advocates.

Unfortunately, these gains are now under threat. Proposed regressive amendments

to Somalia’s draft Federal Constitution particularly those seeking to legalize Sunna1 forms of FGM are alarming setbacks. 2 Sunna FGM, often presented as a milder or more acceptable version of the practice, still involves the cutting or alteration of female genitalia and constitutes a violation of the right to bodily integrity. These amendments contradict both international human rights norms and the original spirit of Somalia’s 2012 Provisional Constitution, which recognized FGM as a form of violence and torture. The legitimization of any form of FGM, under any label, represents not only a betrayal of the rights of Somali women and girls but also undermines the efforts of local activists who have risked their lives to challenge this harmful tradition.

The patchwork approach to banning FGM across federal member states has created a situation where the protection of girls is largely dependent on geography. In some regions, regional governments and religious leaders have issued fatwas or passed laws banning the practice, while in others, it continues unabated. Even in areas with legal bans, enforcement remains weak due to limited resources, fear of community backlash, and a lack of training among law enforcement personnel. This uneven protection underscores the urgent need for a unified, national legal framework that unequivocally prohibits FGM and ensures consistent implementation and enforcement across all regions.

Addressing FGM in Somalia therefore requires a multidimensional strategy that combines legal reform, community engagement, religious dialogue, education, and survivor support. It is critical that the Somali Government, in partnership with civil society, religious authorities, international agencies, and development partners, prioritizes the enactment of the draft Anti-FGM Bill and backs it with adequate resources for enforcement, monitoring, and survivor care. Furthermore, sustained investment in public education campaigns and school curricula is essential to challenge the societal myths that sustain FGM and to empower future generations with the knowledge and courage to reject it.

To help make this a reality, the purpose of this policy brief is to provide an in-depth analysis of the Anti-FGM Bill by examining its strengths, weaknesses, and areas for improvement to better align with international and regional human rights frameworks. The ultimate goal is to establish a stronger legal foundation to effectively combat the persistently high prevalence of FGM in Somalia.

1 The Sunna type of Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) refers to the partial or total removal of the clitoral hood and/or clitoris, often believed to be less severe but still harmful. Despite its name, it has no basis in Islamic teachings and poses serious health and human rights risks.

2 Somalia’s provisional constitution lacks clarity on the issue of female genital mutilation. While it declares that “female circumcision is a cruel and degrading customary practice and is tantamount to torture,” and prohibits the practice, it does not provide a clear definition of “female circumcision.” As a result, it is uncertain whether this term fully encompasses all forms of female genital mutilation.

According to Human Rights Watch (HRW), the constitutional review process should explicitly include a comprehensive ban on every form of FGM. Doing so would lay the groundwork for the government to develop effective laws and policies aimed at completely eliminating the practice. See HRW, Somalia: Constitutional Proposals Put Children at Risk, available at: https://www.hrw.org/ news/2024/03/29/somalia-constitutional-proposals-put-children-risk.

Somalia’s Anti-FGM Bill comprises of 13 articles grouped into various parts that define the offence, set penalties, describe protection measures, and elaborate enforcement mechanisms.

The following sections below are a thematic analysis of Bill’s strengths and weaknesses aligned with international and regional human rights instruments.

In terms of its strengths, the Anti-FGM Bill in Somalia presents a broad and inclusive definition of female genital mutilation under Articles 1 and 2, encompassing a wide range of harmful practices such as clitoridectomy, excision, infibulation, and other procedures like pricking, piercing, scraping, or cauterizing the female genitalia. This comprehensive framing reflects a progressive step toward recognizing the full scope of FGM and its diverse manifestations. Importantly, the Bill also takes a firm stance in rejecting any cultural, religious, or customary justifications for FGM, an approach that aligns with international human rights standards. This includes Article 5 of the CEDAW and General Comment No. 14 of the CRC which both emphasize that harmful traditional practices must not be tolerated under the guise of cultural or religious values and Article 5(b) of the Maputo Protocol, which specifically prohibits all forms of FGM, including its medicalization, through legislative measures backed by sanctions. This reflects a strong legal commitment to eliminating the practice.

Article 3 of the Bill marks a significant advancement by criminalizing all forms of female genital mutilation, including those performed by medical professionals or even self-inflicted cases. This comprehensive criminalization aligns with key international instruments such as Article 5 of the Maputo Protocol and Articles 19 and 24(3) of the CRC, which obligate states to protect women and children from harmful practices, including those carried out under the guise of medical necessity or personal choice.

Furthermore, the Bill makes it explicitly clear that consent is not a valid defense, a crucial clause that aligns with the CAT, which maintains that torture or inhuman treatment cannot be justified even with the victim’s consent. This is also in line with CEDAW General Recommendation 31, which underscores that cultural or individual consent cannot override the rights of women and girls to be free from violence and bodily harm.

Articles 8 and 10 of the Bill demonstrate a forward-looking approach by addressing both cross-border FGM and preventative legal mechanisms. Article 8 criminalizes the act of taking a girl out of Somalia or bringing someone into the country with the intention of subjecting them to FGM. This provision is a vital step in closing legal loopholes that allow families to bypass national restrictions by conducting practice abroad. It brings Somalia in line with Article 19 of the ACRWC and United Nations General Assembly Resolution 69/150, both of which stress the need to combat cross-border harmful traditional practices. Meanwhile, Article 10 introduces protection orders, empowering courts to intervene when there is credible risk that a girl or woman may be subjected to FGM. By allowing any concerned individual, not just the potential victim to petition the court, the Bill mirrors progressive legal practices from countries like the UK and Kenya, where protective court orders have played a crucial role in

preventing FGM before it occurs. Article 6 of the Bill is notably progressive in its recognition of the social and psychological harm that accompanies FGM-related stigma. Criminalizing the use of derogatory or abusive language toward girls who have not undergone FGM, or toward men who marry such women, the law directly confronts one of the most powerful non-physical drivers of the practice: social pressure and shaming. This provision supports the right to dignity and non-discrimination as outlined in Article 2(f) of the CEDAW, which obligates states to address cultural and social practices that reinforce gender inequality. By targeting stigmatizing language, the law takes an important step beyond physical protection and into the realm of cultural transformation.

Articles 7 and 9 of the Bill take a progressive stance by establishing accountability for both inaction and silence in the face of FGM risk. Article 7 introduces legal liability for parents, guardians, or any responsible adult who fails to protect a girl under their care from undergoing FGM. This provision reinforces the principle of child protection as outlined in Articles 3 and 19 of the CRC, which emphasize the obligation of both the state and caregivers to act in the best interests of the child and prevent all forms of physical or mental violence. Article 9 complements this by imposing a mandatory duty to report on any individual who has knowledge of an actual, ongoing, or planned FGM act. This aligns with General Comment No. 18 of the CRC, which stresses that states must not only establish preventive measures but also hold individuals accountable for failing to act when a child’s rights are at risk.

Finally, Article 11 of the Bill outlines a strong punitive framework that reflects the seriousness of the offense and aligns with international obligations to combat torture and cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment. The provision allows for life imprisonment in cases where FGM results in death and imposes 10 to 15 years of imprisonment for aggravated circumstances such as disability or transmission of HIV. These harsh penalties underscore the gravity of FGM as a human rights violation and fulfill Somalia’s obligations under Article 4 of the CAT, which mandates that states impose appropriate penalties for acts of torture and ill-treatment. By treating FGM not as a cultural custom but as a violent crime deserving of the highest level of legal censure, the law signals a critical shift in national priorities and a commitment to ending impunity for perpetrators.

Despite the promising framework of the FGM Bill, several contradictions arise when measured against international and regional human rights standards.

Firstly, despite the broad definition of FGM under Articles 1 and 2 of the Bill, it overlooks critical and contextual nuances that weaken its overall impact. Notably, the Bill fails to specifically address or name the Sunna type of FGM, which is widely practiced in Somalia and often perceived as a milder or acceptable form of the practice. By avoiding specific reference to Sunna, the law creates space for continued ambiguity and potential justification of this form under cultural or religious pretexts, despite its clear harms.

Additionally, the Bill does not account for the psychosocial consequences of FGM or include a survivor-centered framework that offers medical, psychological, or legal support for victims. This absence reflects a critical gap in ensuring accountability and redress. Survivors of FGM are often left to endure the physical and psychological consequences in isolation, without state-facilitated pathways to healing or justice. As such, this omission undermines obligations under international norms, including Article 14 of the CAT and Article 39 of the CRC, both of which call for comprehensive rehabilitation services for survivors of harmful practices and abuse. It further undermines the spirit of protection the Bill seeks to uphold.

Notably, Article 3(4)(a) and (b) introduces a potential loophole by permitting FGM if deemed necessary for a woman’s “mental or physical health.” While such exceptions might be intended for legitimate medical interventions, the absence of clear definitions or safeguards opens the door for potential abuse. In a context like Somalia, where Sunna FGM is often misrepresented as religiously or medically justified, this ambiguity risks being exploited to perpetuate the very practices the Bill seeks to eliminate. Moreover, the law lacks a provision requiring independent or mandatory psychological evaluations to determine when such procedures are genuinely necessary. This weakens legal oversight and undermines the protective intent of the legislation, leaving space for medicalization of FGM under dubious pretenses.

This clause, if left unregulated, risks legitimizing medicalized FGM, which is firmly rejected by both the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). These international instruments emphasize the absolute prohibition of all forms of FGM, regardless of the setting or rationale, underscoring that so-called medical justification does not mitigate the harmful and discriminatory nature of the practice.

While Articles 8 and 10 of the Bill progressively address both cross-border FGM and preventative legal mechanisms, significant gaps still remain, particularly around enforcement and international cooperation. The Bill does not provide any clear implementation mechanisms to support cooperation with foreign governments or legal systems in terms of investigation, extradition, or mutual legal assistance around FGM cases.

This shortfall undermines the effectiveness of Article 8 and hampers Somalia’s ability to fulfill its obligations for coordinated and collaborative efforts between states to eliminate FGM in all its forms, including its transnational dimensions. Without specific procedures or institutional frameworks to support international legal collaboration, the provisions on cross-border FGM risk becoming symbolic rather than actionable.

While Article 6 of the Bill commendably criminalizes the use of “derogatory” or “abusive language” toward girls who have not undergone FGM, or toward men who marry such women, the vague and undefined use these terms leaves room for subjective interpretation and inconsistent enforcement. Without clear legal definitions or contextual examples, there is a risk that the law could either be under-enforced, due to uncertainty over what qualifies as abusive language, or misused, to punish legitimate expression or community dialogue.

This lack of clarity may also deter victims from reporting violations, fearing that their complaints may not be taken seriously or legally upheld. To ensure the effectiveness of this provision, the law would benefit from incorporating specific guidance or standards for identifying stigmatizing language, as well as training for law enforcement and judicial officers on the cultural dynamics of FGM-related shame and discrimination.

Further, the Bill establishes accountability for both inaction and silence in the face of FGM risk under Articles 7 and 9 as mentioned above. Despite this critical step, the Bill does not offer sufficient clarity on how the legal system will determine guilt in failure-to-protect cases, particularly with regard to the burden of proof. This ambiguity could discourage genuine caregivers who may be unaware of risks or lack control over extended family actions.

The Bill also omits the inclusion of protection and support mechanisms for whistleblowers, such as teachers, health workers, or neighbors, who may fear retaliation or stigma for reporting suspected FGM cases. Without clear legal safeguards, these mandatory reporting requirements risk being underutilized, weakening enforcement and leaving many girls vulnerable despite the law’s intent. To be truly effective, the law must balance accountability with procedural fairness and supportive protections for those acting to prevent FGM.

Despite the Bill’s strength in imposing strong criminal sanctions against FGM, the penalties provision lacks a restorative justice lens, offering no alternative or complementary measures such as non-custodial sentences, community education, or rehabilitation programs for either offenders or survivors.

This reflects a purely punitive approach that may fall short in addressing the underlying social drivers of FGM or supporting long-term behavior change. Moreover, the absence of rehabilitation efforts contradicts guidance from international frameworks like Article 14 of the CAT and CEDAW General Recommendation No. 19, both of which stress the importance of comprehensive remedies, including education and reintegration, for survivors and communities. Without provisions for awareness campaigns or rehabilitation pathways, the law risks being perceived solely as a punitive instrument rather than a transformative tool for societal change. Lastly, the Bill neglects to meaningfully include children in its prevention mechanisms, diverging from Article 4 of the ACRWC, which emphasizes the right of children to be heard in all matters affecting them. This omission not only weakens the preventive capacity of the legislation but also disregards the agency and insights of young girls, who are most at risk of undergoing FGM.

Ratifying the Maputo Protocol, CEDAW, ACRWC, and other key international and regional human rights instruments would represent a transformative step in Somalia’s efforts to eliminate FGM and broader gender-based inequalities. These treaties not only establish clear legal obligations for states to prohibit harmful traditional practices, but also provide frameworks for survivor-centered protections, community education, and institutional accountability. For example, Article 5 of the Maputo Protocol explicitly requires states to outlaw all forms of FGM and to take legislative and other measures to eliminate the practice, including through public awareness, health services, and the support of survivors. CEDAW Articles 2 and 5, meanwhile, call for the elimination of discriminatory laws and practices, and measures to transform social and cultural norms that perpetuate gender inequality. By ratifying these instruments, Somalia would be obligated to integrate these principles into its national legislation, including constitutional reforms, judicial procedures, and resource allocation— ensuring a rights-based and coordinated national approach to ending FGM.

Moreover, ratification would strengthen the capacity of Somali institutions and civil society actors to advocate for change, seek justice, and hold authorities accountable. It would allow Somalia to participate and engage with international and regional monitoring bodies, such as the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, UN treaty bodies, committees and its special procedures, which provide avenues for international review, reporting, and support. This external oversight can help ensure the implementation of anti-FGM laws like

the 2019 Bill is not just symbolic, but meaningful in practice. It would also legitimize and empower local WROs, whose efforts are often undermined by legal ambiguity and political resistance. In essence, full ratification and domestication of these treaties would not only bring Somalia into alignment with African and global norms but would also provide the legal, political, and moral tools necessary to combat FGM and dismantle structural discrimination against women and girls.

In light of the analysis above, the following recommendations are made to enhance the effectiveness of the Anti-FGM Bill of 2019 as follows:

Explicitly ban all forms of FGM, including those categorized as sunna.

Revise the definition of FGM to specifically include all types, including those commonly practiced and categorizes as sunna , to address local misconceptions and ensure all forms are clearly recognized as harmful, non-medical, and not religiously justified.

Incorporate a survivor-centered framework.

Include mandatory provisions for psychosocial support, legal aid, and medical care for survivors of FGM. This aligns with Somalia’s obligations under Article 14 of the CAT ,Article 39 of the CRC , and ensures the law supports victims beyond punitive measures.

Clarify exceptions to prohibited procedures.

Remove or narrowly define exceptions in Article 3(4) regarding surgical interventions for “mental or physical health.” Any permitted procedures must be based on independent medical evaluations and include strong oversight mechanisms to prevent abuse or medicalization of FGM.

Strengthen language on stigmatization and social harm.

Provide clear definitions and examples of what constitutes “derogatory” or “abusive” language to ensure consistent application of Article 6 of the Bill. This should be supported by public awareness campaigns and training for law enforcement and judiciary on harmful FGM-related social norms.

Establish whistleblower protections.

Introduce robust legal protections for reporters of FGM, including health workers, educators, and community members. This includes safeguards against retaliation and a confidential reporting mechanism, in line with best practices in child protection.

Detailed enforcement and burden of proof provisions.

Provide clear guidelines on the burden of proof in failure-to-protect cases under Article 7 to ensure that the provision does not inadvertently criminalize caregivers acting in good faith. Include criteria for reasonable knowledge and control over the child.

Operationalize cross-border enforcement mechanisms.

Establish formal cooperation protocols with neighboring countries and international law enforcement bodies to investigate, extradite, and prosecute cross-border FGM cases. This would operationalize Article 8 and fulfill obligations under the Maputo Protocol.

Mandate nationwide public education programs.

Include a statutory requirement for the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Education to collaborate on public awareness campaigns, school-based education, and community outreach to shift social norms and dismantle the cultural acceptance of FGM.

Integrate restorative justice measures.

Complement punitive sanctions in Article 11 with restorative and rehabilitative options such as community service, education programs for offenders, and dialogue-based reintegration. This approach acknowledges the social nature of FGM and focuses on sustainable change.

Ensure the full domestication of international and regional treaties.

Expedite the ratification and domestication of the CEDAW, CRC, ACRWC, CAT and the Maputo Protocol, and reference these frameworks explicitly within the Anti-FGM Bill to enhance its legitimacy, accountability, and alignment with international human rights obligations.

Create an independent monitoring and evaluation mechanism

Establish a national oversight body to monitor the implementation of the Anti-FGM law, collect data, track cases, and publish annual reports. This body should include representatives from WROs, survivors, legal experts, and health professionals.

The paper through a human rights lens reveals a commendable but incomplete legal effort to eradicate one of the most entrenched forms of gender-based violence in Somalia. The Bill stands out for its broad criminalization of FGM, its rejection of cultural and religious justifications, and its forward-looking approach to cross-border practices and stigmatization. These elements show clear alignment with international and regional human rights standards and demonstrates a serious attempt to fulfill Somalia’s obligations under instruments such as CEDAW, CRC, the Maputo Protocol, and the CAT. The inclusion of protection orders, mandatory reporting, and strong punitive measures further illustrates an intention to create a deterrent legal framework that moves beyond symbolic commitments.

However, the Bill’s progressive aspirations are undermined by several critical omissions and ambiguities. The failure to explicitly ban Sunna FGM leaves a dangerous loophole that risks legitimizing one of the most commonly practiced forms of mutilation in Somalia. Similarly, the absence of survivor-centered services, weak implementation mechanisms for cross-border cooperation, and the lack of legal clarity in key provisions such as stigmatizing

language and failure-to-protect offenses reduce the Bill’s potential to be transformative. Without well-defined enforcement structures, procedural safeguards, and protective systems for whistleblowers and survivors, many of the Bill’s promising provisions may remain under-enforced or exploited.

To genuinely safeguard the rights of women and girls, Somalia must move beyond legislative drafting toward concrete implementation grounded in human rights principles. This includes incorporating survivor rehabilitation, clearly outlawing all forms of FGM including those categorized as Sunna, and building institutional capacities for enforcement, protection, and community education. The Anti-FGM Bill should not only punish offenders but also dismantle the social and cultural systems that sustain the practice. With strong political will, engagement from WROs, and alignment with international and regional human rights norms, Somalia can transform this legislation into a powerful tool to end FGM and restore bodily autonomy and dignity to millions of girls and women across the country.

https://sihanet.org/support-us/