Inthe rituals related to an individual’s transition from one status to another, people’s mentality can be easily influenced by spiritual forces. In the transitional process, some special ritual objects are applied to consolidate the progress of rites of passage, such as creating a ‘bond’ between individuals and groups by the movement of objects among persons or giving values to objects with ‘ceremonial acts’. Moreover, noted by Van Gennep (2004), once this bond is created, it can only be broken by another ‘special rite of separation’ (2004, 31).

A pottery is a common ritual object in the initiation rites — a transitional period for cultivating and testing teenagers’ responsibilities of being adults. At this stage, artworks symbolically give edification and moral lessons to young people through its own ‘visual expression’, which can be understood as, e.g., masked performances, pottery images, figural sculptures, etc. In some tribes of the Bemba, introduced by Victor Turner (1995), a “secluded girl is said to be ‘grown into a woman’ by the female elders—and she is so grown by the verbal and nonverbal instruction she receives in precept and symbol” (1995, 103). In the rites, a pottery with a sacred image of the tribe on the surface will be used as the physical bond established between the girl and the tribe.

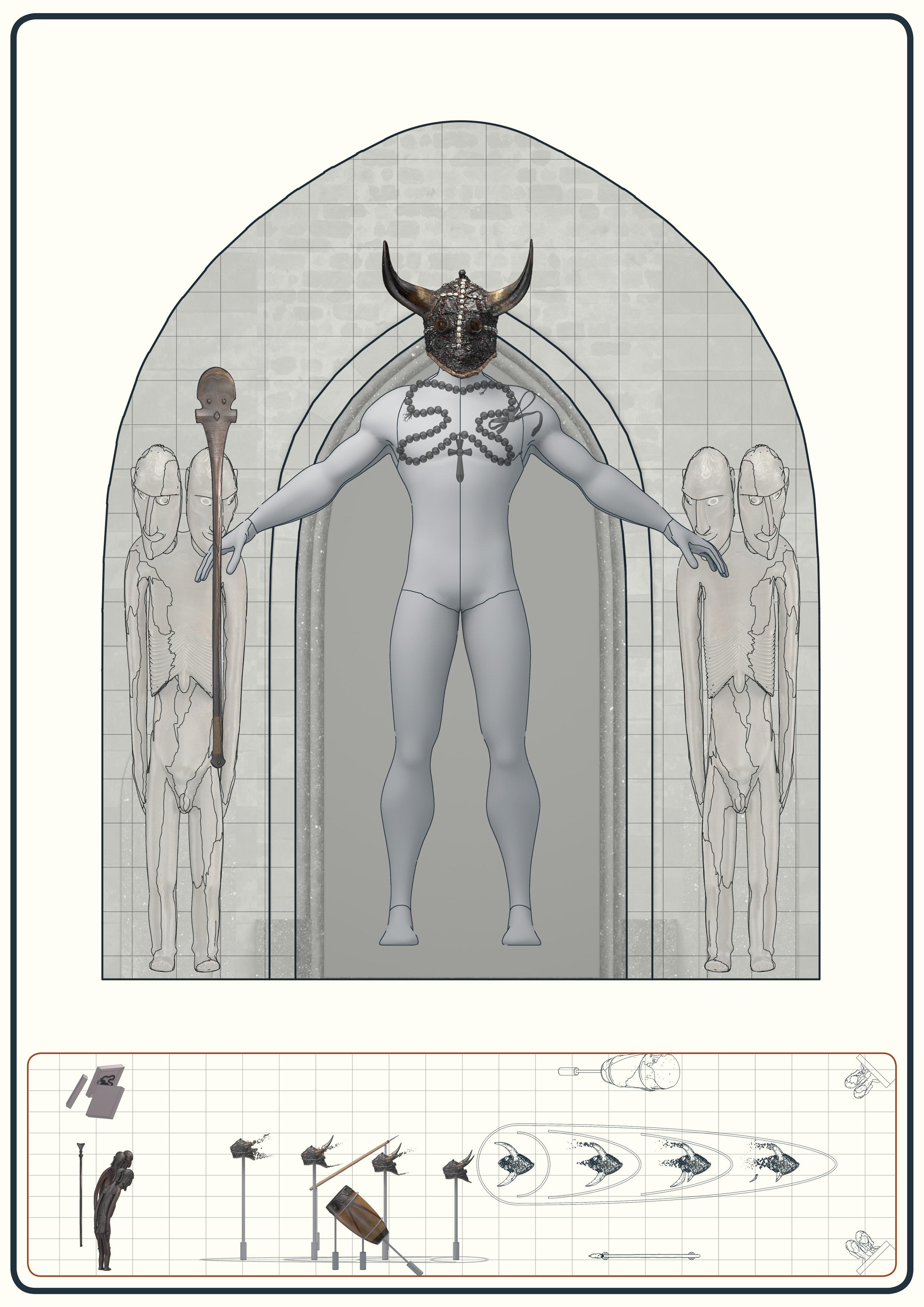

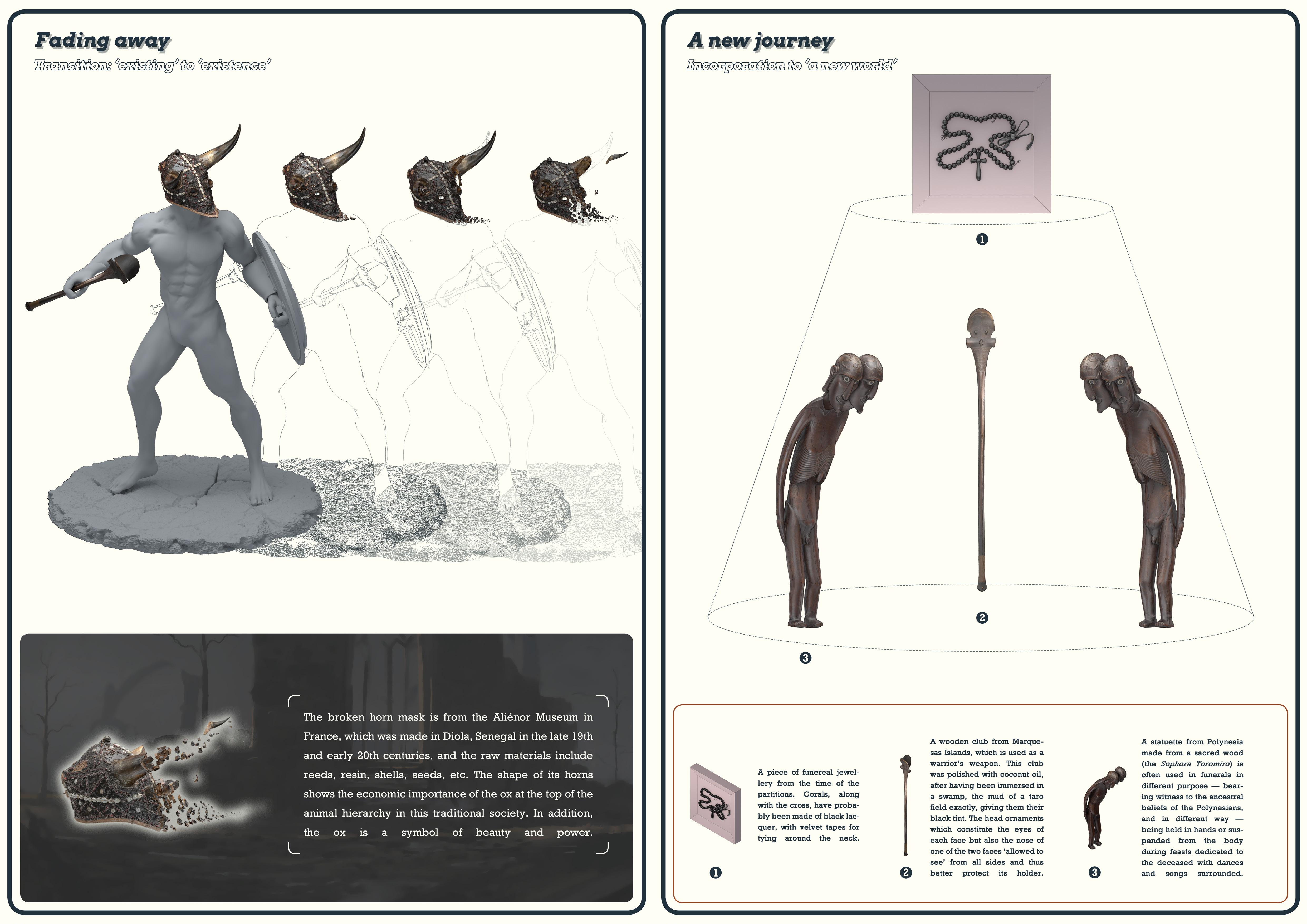

Masks

and masked-performances are very common to see during the initiation of boys. It is mentioned by Christa Clarke (2006) that, male dancers may perform several times with faces covered by wooden masks for multi-purposes, “to educate boys about their future social role, to bolster morale, to impress upon them respect for authority, or simply to entertain and relieve stress”. The mask, in Van Gennep’s statement, can be viewed as a temporary or permanent boundary set up between the sacred and the secular. Because in some cases, sight is contact — a special visual contact that differs from the physical contact by touching. Hence, it could then be comprehended why some people may wear a veil (a special kind of mask) on face in worship. As Van Gennep (2004) explained, “to separate themselves from the profane and to live only in the sacred world, for seeing is itself a form of contact” (2004, 168). He gave one example that, for Moslem women and Jewish women of Tunisia, covering faces with a veil is to “isolate themselves from the rest of the world” because they belong to their sex group and a given family group simultaneously (Van Gennep 2004, 168). On the contrary, taking off the veil may mean go back from the sacred (or to say the transitional stage) world to the profane (or more broadly, the incorporation to a community).