‘CORRUPTION’

Lead Editors - Gavriella Epstein-Lightman and Esala Jayasuriya

Staff - Dr Ian St John and Daniel Heyman

Deputy Editors - Anoushka Pathak and Nikhil Dewan VOLUME 15 - 2024

‘CORRUPTION’

Lead Editors - Gavriella Epstein-Lightman and Esala Jayasuriya

Staff - Dr Ian St John and Daniel Heyman

Deputy Editors - Anoushka Pathak and Nikhil Dewan VOLUME 15 - 2024

History, at its core, is more than a chronicle of past events. As Benjamin Walter reminds us, history gains meaning through its meaningful relationship to the present. It is not a static record but a living dialogue between what was and what is. When we examine history through the lens of corruption, this truth becomes even more apparent. Corruption is not simply a relic of bygone eras; it persists as a force we must continually grapple with today. It has shaped our world, but more crucially, it continues to shape it—demanding that we reckon with its presence not just in distant regimes or ancient systems, but in the power structures and institutions we live under now.

In reading these stories, we invite you to see how history’s enduring dialogue with corruption can illuminate both the battles fought and those yet to be won. Malversation may be timeless, but the fight against it is as urgent now as ever.

It has been an absolute pleasure working on Timeline 2024. The sheer quality and variety of submissions this year has been astounding, and I truly believe there is something hidden within these pages for everyone. Whilst the main focus within this magazine is the theme of corruption, we have also received a strong range of quality articles from other areas. I really hope you relish the inexhaustible variety of intellectual curiosity this magazine has to offer in the same way I did. My final words are a quote from Mark Twain, denoting the importance of studying History.

‘History never repeats itself, but it often does rhyme.’

-Esala Jayasuriya

Lead Editors - Gavriella Epstein-Lightman and Esala Jayasuriya

Staff - Dr Ian St John and Daniel Heyman

Deputy Editors - Anoushka Pathak and Nikhil Dewan

Editorial Team - Lanre Pratt, Ameya Barot. Amar Malde, Pranavi Shah

Family Dynasties in Third-World Country Politics - Shakir Moledina

Gaius Verres and Marcus Tullius Cicero: Revealing Corruption in Ancient Rome - Delilah

Or Market Entrepreneurs” - Pranavi

20 Charles Grey, Second Earl of Howick, 1764-1845 - Dr Ian StJohn

The Forgotten Queen - Ashleigh Teper

Who was the better war-financier – Pitt or Gladstone? - Ameya Barot

IN HISTORY 34 To what extent was Mao Zedong a disastrous leader? - Richard Zhou 40 Review: ‘Dictators’ by Frank Dikötter - Amelie Bruce

Review: ‘William Pitt the Younger’ by William Hague - Marisa Toms 43 Without the leadership of Otto von Bismarck, would Prussia have unified the German states in 1871? - Lucas Argent

47 Is Mao Zedong’s leadership viewed in a negative light? - Ria Shah MISCELLANEOUS

51 The Lewis Chesspieces - Lawrence StJohn 54 The Catastrophe of Counterfeiting - Elodine Levine

57 The Forgotten Genocide - Ebele Ezeuko

60 How Effective was Fear as a Tool used by the Soviet Union to Maintain Order?Lucas Argent 64 My Family in Uganda - Veer Gill

67 Review: ‘Why Ireland Starved: A Quantitative and Analytical History of the Irish Economy’ - Nikhil Dewan

“Power does not corrupt men; fools, however, if they get into a position of power, corrupt power.”

-George Bernard Shaw

By Francesca Notarianni

Martin T. Manton could be considered an embodiment of the American dream. From being born into a poor Irish immigrant family in 1880s Brooklyn, to becoming king of the American courts and even being short-listed for a seat on the American supreme court. However, it all came crashing down when the federal judge was forced to leave the bench in disgrace in the most shocking case of judicial corruption of the 20th century.

Martin T. Manton worked his way through the education system and into private law practice where he combined the two practice areas of personal injury and criminal defence, specialising in murder defence. One of his most notable cases was his representation of a NYC police officer accused of orchestrating the murder of a small-time gambler who had the officer on his payroll. This was an especially prevalent trial, as at the time there was growing attention on corruption in the NYC police department. This gained Manton publicity, and it was only 3 years later in 1918 when he was appointed by President Woodrow Wilson to the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. Due to New York’s commercial, financial, cultural, and political influence over the rest of the country, the Second Circuit handled a disproportionate share of the USA’s most consequential lawsuits. Manton served on the Second Circuit for over two decades, and during his time he earnt the title of the court’s senior judge, a position second to only the nine judiciaries of the supreme court.

During the Great Depression of 1929, Manton suffered severe financial losses. His fortune earnt from being a lawyer was invested in real estate and businesses, so when the stock markets crashed Manton’s fortune was gravely depleted. It could be these losses that caused Manton to begin accepting gifts and loans from the litigants who appeared before his court in return for ruling in their favour. Manton was not selective in his customers of justice, his litigants ranged from commercial companies such as the Fox Theatre Company and Warner Brothers, and evidence showed that Manton often held stock in companies that were litigants in whose favour he decided. Rather disturbingly, among the many litigants who appealed to Manton were the two most notorious New York gangsters of the era, Louis ‘Lepke’ Buchalter and Jacob ‘Gurrah’ Shapiro. The outlaws had arranged a payoff to Manton in order to

secure their release on bail and went on to assassinate the witnesses against them. It was also well known in New York prisons which housed federal defendants that Manton was corrupt. In one instance, an inmate who was cooperating with federal government in a drug case told the other inmates who were suspicious of him that he was paying off Manton.

Although in reality this was not true, the other inmates stopped bothering him as they believed him. The fact the inmates believed him emphasises how well-known Manton’s corruption really was among litigants. Manton’s gifts came in a number of different forms. It was sometimes cash, sometimes money given directly to his family, and on one occasion a litigant financed Manton’s summer holiday on a transatlantic voyage. Manton was ultimately selling justice to build his private fortune, and it is estimated that he earnt $823,000 which equates to $17 million in today’s dollars. By 1939 rumours of corruption began to spread and Manton was pressured into resignation due to investigations and recommendations of impeachment. Following his resignation, Manton was indicted and brought in front of his previous colleagues at the court where he once sat as a judge. He faced charges for conspiracy to obstruct the administration of justice and to defraud the United States. Manton was found guilty and given the maximum sentence of 2 years and a $10,000 fine.

Even recently Manton has caused controversy. In 2009 an oil painting of the disgraced judge was discovered and posed the question if it should be displayed or hidden. Although it is not an easy question to answer, the story of Manton serves as a reminder that judges are not sealed off from worldly temptations and are human too.

By Marisa Toms

Corruption was at the core of the Roman Empire. From its senators to its merchants and finally, to its Emperors and Empresses. The majority of the Roman population at the time was greedy and had resorted to bribing people to extend their powers and gain more wealth and land. They only thought of themselves and did everything and anything they could to ensure that they lived a comfortable life, no matter the cost. However, these criminal acts weren’t only committed by men, but by women also. Two clear examples were Livia Drusilla and Agrippina the Younger, both wives of Emperors. However, what role and influence did these women have within the Roman empire?

Livia Drusilla was the daughter of Marcus Livius Drusus Claudianus and wife of both Tiberius Claudius Nero and Emperor Augustus. When she was married to Tiberius, Livia had a son, the future emperor Tiberius and was also pregnant with Nero Claudius Drusus. The Emperor Augustus, in 38 BC, forced her to divorce her husband so that they could marry. Although she didn’t give birth to any of his children or heirs, they were happily married for 51 years. Donna Hurley says how Livia was given the right to manage her affairs without a guardian and a grant of ‘sacrosancitas’. The meaning of ‘Sacrosancitas’ in English, according to the Oxford Dictionary, is something that is deemed too important to question or change. Therefore, when Livia was given this huge honour, which mainly only tribunes enjoyed, she became more powerful and was able to have a greater influence over the entirety of the Roman Empire without her actions being questioned. With this power, Livia was able to have a major influence over state affairs. She was also involved in many political decisions and appointments of various individuals. However, she almost always directed the policies in ways that served her interests and those of her family. The amount of unchecked influence Livia had, although it was common for powerful political figures during the time, could be seen as corrupt since it bypassed the traditional structures of governance.

Furthermore, not only was Livia able to manipulate political decisions, but both Tacitus and Cassius Dio, Roman historians, wrote about the various rumours on how Livia gained her newfound power after she married Emperor Augustus. One of the most popular rumours was that she murdered many of Augustus’ relatives to ensure that her son, Tiberius, became the next Emperor, and she, therefore, maintained her power. One of these relatives was Emperor Augustus’ grandson, Agrippa Postumus. Moreover, both writers further mention that there was a possibility that Livia killed Augustus herself by poisoning some fresh figs which he then ate so that her son could become Emperor right away. Although this may have happened, many people nowadays think that this was very unlikely. Livia was further said to have corrupted Julia the younger, Emperor Augustus’ daughter, and Agrippa Postumus. Julia the younger was exiled due to her leading a promiscuous life and Agrippa, her son, was exiled and killed since he openly opposed Livia and was a potential candidate for Emperor after Augustus’ death, therefore being a double threat. Even though Livia is rumoured to have committed these murders for her son to become Emperor and for her to maintain her power and influence, in I Claudia II: Women in Roman Art and Society (which is a gathering of essays about women in Roman society based off evidence we have, such as art and texts by Diana E. E. Kleiner and Susan B. Matheson) she is described as serving as a public image for the idealisation of Roman female qualities, a motherly figure and god-like virtues. Therefore, although Livia had a strong image and was a role model to many women during those times, she did anything, no matter the consequence, to secure her and her son’s power from assassinations to manipulating important political decisions.

Agrippina the younger was another upper-class woman. She was the daughter of Germanicus Caesar, mother of the Emperor Nero and wife of the Emperor Claudius. When Agrippina married Emperor Claudius, he already had a son which was going to be his heir, Britannicus. However, Agrippina was able to convince her husband, Emperor Claudius, to adopt Nero and make him his heir. To ensure that her son became Emperor, she involved herself in many plots that resulted in the deaths of several individuals, one of which was her husband Emperor Claudius. Ancient sources say that she had poisoned the emperor with a plate of deadly mushrooms at a banquet on October 13 54 AD. Even when Nero had become Emperor, she continued to manipulate the political alliances she had obtained over the years and created many plots to eliminate any threats to her son and his succession. Due to her powerful position, she abused her power by using her relationships and connections within the Roman elite to achieve whatever she wanted. This included using her position as Emperor Claudius’ wife to influence political decisions and appointments. Furthermore, she used her power and position to accumulate a lot of wealth, sometimes through questionable ways. This was mainly done through bribery and coercion and could be said to be corrupt enrichment. In Roman society, Agrippina the Younger was viewed as a caring and vulnerable woman, mother, and wife, but at the same time was seen as

ruthless and cunning, quite different from the way that Livia was viewed as a motherly figure with God-like virtues even with the various rumours which surround her. Therefore, Agrippina was corrupt in several ways since she used her power and position to eliminate threats to the son’s succession and also to manipulate important political decisions and increase the amount of wealth and land she had.

In conclusion, the lives of Livia and Agrippina the Younger emphasise the influential roles women had within the corrupt Roman Empire even though politics and power were only accessible to males. Both women used their power and influence to manipulate political decisions and their connections with the Roman elite to achieve what they wanted. Both assassinated individuals to eliminate threats, coerced and bribed to ensure that their power increased and that their families were safe and comfortable. Agrippina went to such an extent to ensure that her son Nero became Emperor since she thought she would be able to control him and possess all that power for herself. Therefore, Livia and Agrippina demonstrate how women in the Roman Empire could have considerable influence even though they faced many gender barriers. Both these women serve as examples of how women were able to navigate corruption in the Roman Empire and manipulate it to serve their purposes and help them gain the power they were so greedy for.

By Shakir Moledina

Politics is the art of making your selfish desires seem like the national interest” - Thomas Sowell

The issue of family dynasties in third-world country politics is a complex and prevalent issue that plagues many countries in the world today. In this article, I will explore the political landscapes of Kenya and Pakistan, examining the influence of the Kenyatta and Sharif families. I will also explore the implications of the Panama Papers scandal that exposed years of political corruption and offshore funds. This article will analyse the family-dominated political landscapes of Pakistan and Kenya.

It is first important to understand and define what is meant by a political family dynasty. A political dynasty is a family in which multiple members are involved in politics. Members may be related by blood or marriage. A third world country is defined as countries that are poor or developing. Countries that are part of the “third world” generally have high rates of poverty, economic and/or political instability, and high mortality rates.

However, what is the issue with political dynasties? Well, the concentration of political power in one family alone for years gives it massive influence and gradually turns political rule in a country into a monarchical system. Eventually this family will use their power and influence for personal use and gain. This isn’t the case with every political dynast, however in truth it is more so than not. This article will cover two prime examples of corrupt political dynasties manipulating their influential roles for personal gain.

There are many reasons for political dynasties, one of those reasons is that most of those families have amassed a lot of money and personal benefit through illegal means, resultantly, such leaders fear the consequences of leaving office and facing accountability, so they will do all they can to protect themselves by keeping like-minded family members in power. For example, when Nawaz Sharif of Pakistan lost the election in 2018, he fled Pakistan in self-exile to London after the Supreme Court charged him and provided him with bail to avoid the accountability.

Secondly, political families would have made a lot of investments so they want somebody who can either continue that particular process that they have started or somebody who can protect the investment interest of the family.

It seems to be a pattern that, where a political dynasty thrives, so does political instability and economic mismanagement. Such families loot state funds in most cases, hurtling countries into economic crises and political tensions.

The Kenyatta family has played a pivotal role in Kenyan politics, with Jomo Kenyatta, the country’s first President, leading his nation to independence from British rule in 1963. His son, Uhuru Kenyatta, continued the family’s political legacy, serving as President in 2013 and getting re-elected in 2017 with his tenure ending in 2022. During Daniel arap Moi’s presidency (1978-2002), the Kenyatta family-maintained influence within the ruling party. The family’s presence has continually persisted in Kenya’s political landscape, with Uhuru Kenyatta’s presidency one of controversy and monetary gain for the Kenyatta dynasty.

From the start of the Kenyatta family’s influence Jomo Kenyatta misused his role for personal gain as well as gain for his family and close aides. A United Nations-backed commission found that in two years, one-sixth of all properties previously held by Europeans, including “vast farms” and valuable coastal real estate, were “cheaply sold” to Kenyatta, his family and his allies. These properties were cheaply sold to people such as his son Uhuru, and Moi, a former president and close aide of the Kenyatta family.

Although the Kenyatta family has consistently denied any wrongdoing, the Panama Papers leak appears to prove the opposite. “Every public servant’s assets must be declared publicly so that people can question and ask: what is legitimate?” Uhuru Kenyatta said to the BBC in 2018. Years of previously undisclosed political corruption and offshore wealth were made public by the Panama and Pandora papers. The Pandora Papers is the largest known data leak in history (12 million files). Because of the Pandora papers leak, Uhuru Kenyatta and six members of his family have been connected to 13 offshore companies.

The Pandora papers served as a window into the years of offshore companies the Kenyatta family owned. In particular a notorious case called ‘client 13173.’ This is when the Kenyatta’s tried to create a company that wouldn’t be traced back to them while using this company to purchase offshore properties for the Kenyatta family. The Pandora Papers reveal that in 1999, Mrs Ngina Kenyatta and her two daughters, Kristina and Anna, set up an offshore company - Milrun International Limited. Invoices from a law firm to the bank show that the Kenyattas were named with the code ‘client 13173’. This company was used by Mrs Kenyatta and her daughters to buy an apartment in central London, which they still own.

The Kenyattas’ offshore investments included a company with stocks and bonds worth 30 million dollars (£22m). Although, it’s not illegal to run secret companies, some have been used as a front to divert money, avoid taxes and for money laundering. Furthermore, the Kenyattas’ offshore wealth, revealed in the Pandora papers, reveals an estimated half-billion-dollar family fortune amassed despite Kenya’s average salary being less than $8,000 a year.

Furthermore, it seems suspicious that the family began to accumulate much of its offshore wealth while Uhuru Kenyatta was a rising political star. This may allude to the family using state money to grow their offshore wealth; however, nothing has been proved in this regard.

Conclusively, there is much significant evidence to prove the corruption of not only Jomo Kenyatta but his predecessors in his political dynasty. His dynasty benefitted from his power and influence and used it to rise to the top of Kenyan politics again and in the process fund many offshore companies to help build their own secret business empire in the light of their leadership which was used to support this corrupt practise.

Pakistan since its conception in 1947 has been riddled by corrupt politicians, an over-involved army and political dynasties. Two of the three most popular political parties in Pakistan are political dynasties and both parties have had multiple terms as the leading party. The Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) has been the breeding ground for the Bhutto Family’s dynasty while the Pakistan Muslim League (PML) has been the party ruled by potentially the most corrupt political dynasty in modern times: the Sharif family.

Nawaz Sharif is the longest-serving prime minister of Pakistan, having served a total of more than 9 years across three terms. Each term has ended in his ousting. His brother Shehbaz Sharif has also served as Prime minister after former cricketer Imran Khan was ousted as Prime minister in a plan allegedly schemed by an American government official. Pakistan’s then-ambassador to the US, Asad Majeed, and Donald Lu, the Assistant Secretary of State for the Bureau of South and Central Asian Affairs had a conversation that was later leaked in which Lu was worried by Imran Khan’s ‘aggressively neutral stance in the Russia-Ukraine war’ saying ‘all will be forgiven’ if Khan is sacked.

Resultantly, Imran Khan claims the PML-N saw this as an opportunity to take to power. Due to Nawaz Sharif being in self-exile his second-hand man and brother in his dynasty and former chief minister of Punjab, Shebhaz Sharif, took the spot in power. With recent elections Nawaz Sharif has returned to Pakistan to run in elections for his fourth term with all of the corruption cases against him dropped. Allegations of pre-poll rigging and vote-rigging which has caused an uproar globally with David Cameron even raising ‘serious concern over the fairness’ of the elections, and some human right groups even saying that ‘fair elections’ were not possible.

Nawaz Sharif has gone to unimaginable extents to hide his wealth. Nawaz Sharif has been accused of ordering the torture of Rehman Malik by placing his hands and feet on ice for up to an hour at a time at a ‘safe house’ in Islamabad. There were many orders for his release but he was repeatedly arrested on false pretences until the Pakistani Supreme Court declared his detention to be unlawful.

Well, why was Malik arrested? He served as the deputy director of Pakistan’s Federal Investigation Agency (FIA), he investigated claims of widespread of the Sharif family. Along with Malik’s investigation and the Panama papers leak it is undeniable that Sharif’s political dynasty is one of corruption in a third-world country where poverty is all too prevalent. The Guardian published an article on offshore wealth stashed abroad by politicians across the globe and Nawaz Sharif topped the list.

There are many examples of Nawaz Sharif misusing his power for personal gain such as when he made import duties on luxury cars drop from 325 per cent to 125 per cent. A week later they were restored. In between a friend of Sharif imported 80 cars. Nawaz Sharif like Kenyatta has many offshore companies which he also used to the buy the infamous Avenfield flats in London worth in excess £7,000,000.

The Panama papers which were leaked in 2016 revealed that three of Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s children owned offshore companies and assets not shown on his family’s wealth statement. The companies included three British Virgin Islands-based companies. These companies have been used to channel funds to acquire foreign assets, including his flats in Mayfair. One of Sharif’s children that gained from these undeclared offshore companies was Maryam Sharif the now Vice-chairman of the PML party. Her role as his successor clearly to continue the corrupt political dynasty of Nawaz Sharif.

The family, whose empire grew hugely while Nawaz Sharif was in office, was also accused of defaulting on $120m of state bank loans. Furthermore, that was part of a series of transactions in which the Sharif family were lent up to $13.8 million to three of their companies, with their London properties as collateral. It appears Nawaz Sharif wants to keep his family in power at the PML to sustain the Sharif empire. Keeping his family in power will mean the interests of his family will always be fostered whereas if it wasn’t someone from the family him and his dynasty wouldn’t be able to put their personal gain at the forefront.

Nawaz Sharif’s name wasn’t directly mentioned in the Panama papers rather all the companies were put in his children’s names. However, he has been accused of corruption, ownership of illegal assets, tax avoidance and money laundering. When put in court after the leak of the Panama papers he was accused of corruption, Sharif failed to provide a satisfactory explanation for the offshore holdings. The Panama Papers scandals eventually played a pivotal role in his disqualification as Prime Minister by the Supreme Court of Pakistan in July 2017. Him and his family claimed the properties had been acquired through investments in middle eastern countries such as Qatar. In July 2017, the Supreme Court of Pakistan disqualified Nawaz Sharif from office, citing his failure to disclose a source of income that could explain his ownership of the luxury flats. However, this was recently mysteriously reversed in time for Pakistani elections.

In conclusion, family dynasties in third-world country politics, as shown by the Kenyatta family in Kenya and the Sharif family in Pakistan, use their dynasty for corruption and personal gain. The Panama Papers exposed the questionable offshore dealings of both families, revealing an abundance of wealth gained through suspicious means. The Kenyatta family’s offshore investments, highlighted in the Pandora Papers, raised concerns about political justice in a country plagued by widespread poverty. Similarly, the Sharif family’s involvement in offshore companies led to widespread anger and his self-exile. These examples emphasis the need for increased transparency and accountability. Ongoing political rivalries and concerns over censorship and poll rigging in Pakistan highlight the challenges in breaking the cycle of political dynasties in third world countries.

By Marisa Toms

The Roman Republic was a time when the Roman Kings had been removed and democracy was ruling Rome. In his book ‘Conspiracy of Cataline’, Sallust, an Ancient Roman writer, delves into the political history of the Roman Republic and its greatest conspiracy and betrayal: that of Cataline.

Sallust bases his story around Cataline, someone whom he describes as being intimate friends with ‘all assassins or sacrilegious persons from every quarter’ and ‘shameless, libertine, and profligate characters’. He is portrayed as a power thirsty senator as he used all his money, as well as others, in order to help him run for a Consulship, which he then lost three times. Sallust also conveys him as being immoral and ‘guilty of crimes against nature’. However, Sallust’s opinion is limited as it is the opinion of only one man.

Cataline wasn’t alone in the conspiracy, he had many fellow conspirators which helped him to set out his plans. Sallust lists them, all of which wanted to remove the current Consuls, Marcus Tullius Cicero and Gaius Antonius Hybrida, and gain control of the Consulship. Cataline was driven to do this since he was in a lot of debt and if he was able to overthrow the Consuls, he would clear everyone’s debt, including his own. Sallust wrote how he schemed to burn down buildings and paid others to start hostilities in order to cause chaos.

Sallust uses many techniques to intricately portray the corruption within the Roman elite. Although there are various editions due to different translations, they all capture Sallust’s clever writing style and his engaging narrative style. This impacts the reader’s experience and allows them to fully engage with Sallust’s writing.

In conclusion, although, Sallust may exaggerate certain aspects in his book, it is still a valuable source for historians to read and anyone interested in the Late Roman Republic, politics, power, ambition, and betrayal in the ancient world. It is a captivating read and Sallust uses Cataline in order to show the reader about the erosion of traditional values within the Roman society and the rise of greedy, power-hungry individuals, in the Roman elite.

By Delilah Smith

Ancient Rome: the backdrop to some of the most scandalous stories of bribery, greed and corruption in all of history. However, even in such company, there is one particular figure who stands out – a figure whose dubious and disreputable rise to the top shows the degree to which the Roman empire was built upon the hunger for power and wealth. This man was Gaius Verres [figure 1] – quaestor to the consul Gnaeus Carbo; praetor of Rome; and most notoriously, governor of Sicily. Leaving a trail of newly filled pockets and scandalous secrets wherever he went, Verres was at the heart of the most significant corruption case of his time. Yet, one of the most remarkable things about this revealing journey through Roman politics is its dramatic end, which is also the reason why we are able to reconstruct the scale and significance of Verres’ corruption. The legal case against Verres was ultimately put forward by the legendary statesman Marcus Tullius Cicero. The speech in question was called ‘In Verrum’ (against Verres) and was a merciless exposé of not only Verres’ avarice, but that of the Roman government as a whole.

The story of the criminal career of Gaius Verres (115BCE-43BCE) can be traced to his relationship with a general named Gnaeus Carbo. Verres took over responsibility for Gneaus Carbo’s financial activities – activities which, while not quite as audacious as Verres’ dishonest dealings, were also far from honest. This brought Verres access to a certain degree of power and wealth, but the partnership didn’t last long. Verres took advantage of an 83BCE Civil War and used it as an opportunity to embezzle Carbo’s military funds shortly before fleeing and becoming a senior officer to Gnaeus Cornelius Dolabella, the governor of Cilicia (a Roman province in what is now Turkey). These two, it seems, were both motivated by their greed and thirst for power. Together, the kindred spirits laid waste to the provinces of Asia and Pamphylia (the “land of many tribes” located between the modern day Turkish cities of Side and Attaleia), stealing from and ransacking peoples’ homes. According to Cicero’s “In Verrum”, “not one single sanctuary escaped his depredations.” In typical style, however, once Verres had finished with these lands, and the two men had no reason to remain allied, he turned on Dolabella. When the authorities finally caught wind of Dolabella’s illicit activities, he needed someone to defend him. Surely Verres, his trusted friend, his “partner in crime,” would step forward to defend him? Apparently not. Verres’ vicious nature shone through once again, as he not only abandoned Dolabella, but was a key source of evidence for his crimes. The same crimes that he himself had helped to carry out. As Cicero put it, “not merely failing to support him in the hour of danger, but deliberately attacking and betraying him.” Verres was not finished here, though. He returned to what he was best at: bribery, this time successfully aiming for the praetorship of Rome – a position in which he “behaved like a pirate.”

Still, all of these twists and turns were only a prelude to his most damaging actions when, a year later, Verres gained the position of Governor of Sicily. Cicero compares Verres to “a destroying pestilence in his province of Sicily.” It was laughably simple to find a corrupt or suspicious governor anywhere in the Roman empire; however Verres’ behavior was shocking even for this period of history. Between the years 73 and 71 BCE, Verres managed to steal several works of art while, in a seemingly random fashion, calling for the execution of innocent locals, and accepting bribes all the while. Sicilian farmers were left destitute due to extortionately high taxes put into place by Verres, and under his governance Roman citizens were stripped of their rights. The list of crimes that Verres committed whilst stationed in Sicily nearly runs longer than the list of people that he bribed to secure the position. Cicero comments that “nowhere did he multiply and magnify the memorials and the proofs of all his evil qualities so thoroughly as in his governorship of Sicily,” and accuses Verres of leaving Sicily, “ruined so effectually that nothing can restore it to its former condition.” After three long years of misgovernment of the island, Verres left Sicily a shadow of the place it had once been, returning to Rome only to be met with the man who would finally act as a dam in the stream of bribes constantly flowing towards the corrupt governor.

Marcus Tullius Cicero [figure 2] was sent to prosecute Verres, who knew that his case was hopeless. Nevertheless, Verres was not going to leave without putting up a fight. He chose to be represented by Quintus Hortensius Hortalus, a highly respected speaker in his field. Little did Hortalus know this case would be the one which caused him to lose his credibility in court. Verres and Hortalus repeatedly tried to push the trial back until the next year when Verres’ friend Metellus would be the judge, but the trial went ahead regardless. Cicero condemned Verres with just one speech. It was devastating, to the extent that Hortalus allegedly refused to respond, as any effort against Cicero would be in vain. But Cicero had a wider point to make in this condemnatory speech. “In Verrum” used Verres’ case as a chance to highlight the corruption of the Roman courts more broadly, stating that, “A belief has by this time established itself, as harmful to the whole nation as it is perilous to yourselves, and everywhere expressed not merely by our own people but by foreigners as well: the belief that these Courts, constituted as they now are, will never convict any man, however guilty, if only he has money.” Cicero went on to argue that Verres had practically already been “acquitted [...] by his vast fortune.” Still, with any chance of regaining his old lifestyle gone, it was agreed that Verres would go into exile in Massilia. While this trial had delivered some justice to the Sicilians affected by Verres’ severe misgovernment of their island, the damage had still been done. Because of Verres’ actions, Sicily had lost its title as Rome’s main source of grain; and Verres remained in possession of those stolen artworks. If there was a personification of corruption in ancient Rome, in my opinion, it was certainly Gaius Verres, the little known but highly harmful scourge of Sicily.

By Pranavi Shah

‘Robber Baron’ is a term that was coined in the late 19th century to describe wealthy capitalists who were thought to have acquired their wealth through corrupt, economic practices. It was first attributed to Cornelius Vanderbilt who, after providing extremely low prices on shipping routes of government-subsidized shippers, was then paid by them to stop competing on their routes. The term was first coined to express the public discontent with their practices and was a direct descendant of the title attributed to German Lords who charged illegal tolls on rivers.

This is where Folsom attributed the description of “Political Entrepreneur”, to the Barons like Henry Villard who took advantage of government patronage to run unethical business practices. From the 1890s citizens began to use the term as a form of social criticism against the industrialists. They were seen as an elite that preyed on the vulnerable working class to become wealthy and monopolise the markets. Not only Villard but industrialists such as Vanderbilt, J.P Morgan and Rockefeller were all grouped into this category. Much of the public scorned their seeming corrupt practices which allowed no other business to compete against them. An example is J.P Morgan who sought to create a monopoly by reducing his workforce to maximise the profits that he made. The workers were paid as little as $1 a day and the company has been proven to have owned over 1,000 slaves.

Political corruption was another tool exercised by robber barons to ensure that the government was on their side and they could continue to control their business as they wished. A famous example is the Credit Mobilier Scandal which revealed many politicians had taken bribes from a fraudulent construction company. The company was set up to build the Union Pacific Railroad that was overfinanced so shareholders could receive greater profits. Government officials including the vice president were scrutinized and were involved in this scandal, having accepted stocks in exchange for their silence. This was not the only case of political corruption and was repeated over the duration of many years. Individual barons also participated in political corruption when they backed candidates who were inclined to support their business and contributed funding so that the candidates would

have the best opportunity to be elected. Political corruption did not exist only to bribe those who already held seats in Congress but to also ensure that Congressmen were elected who favoured the exploitive economic practices of these Robber Barons.

These economic and political practices are the reason as to why most historians consider Robber Barons solely “Political Entrepreneurs” but Folsom in his book The Myth of the Robber Barons suggests the term is only applicable to some Barons, such as Henry Villard, and others, such as Vanderbilt and Rockefeller, were “Market Entrepreneurs”. Although Robber Barons were largely involved in monopolization, their philanthropy in their later lives is often forgotten. For example, Rockefeller donated 10% of every pay check that he earned and many other Barons donated to education centres, technological research and other organizations which would go on to help the public.

Their impact on the American economy cannot be diminished. The investments in large railway companies and infrastructure meant that the railway coverage grew from 35,000 to 200,000 miles by the close of the 1800s and transport between the West and East was made extremely easy. Their role in industrialization did not stop there and the creation of largescale companies which provided the model for the new business corporations is what earned the 1870s-90s the title of the Golden Age. Robber Barons were key for industrialization and expanding the economy, and providing the groundwork for the future American economy.

Although the term “Market Entrepreneur” is not applicable to all capitalists of the Gilded Age, many of them were not defined by the corrupt practices which marked the political few. There is no doubt that corruption reigned in the wealthiest percentile of the population but this did not reduce the philanthropy of other Barons. Perhaps the corrupt lens through which the Barons are usually viewed is outdated and they should instead be noted as the great industrialists of their age instead of corrupt feudal Lords.

“The more you know of your history, the more liberated you are.”

- Maya Angelou

By Dr Ian St John

Although contesting with Lord John Russell the title of the most famous Whig of the nineteenth century, Earl Grey was not born a Whig – and he didn’t die one either. He was not born into the Whig aristocracy. His father, Sir Charles Grey, was a soldier who supported the King’s government, and this meant, in the 1780s and 1790s, serving under William Pitt the Younger – a man whom his son, Charles, despised. Only in 1801 did General Grey become a Baron in recognition of his military services (especially against the French in the West Indies) and only in 1806 was he made an Earl – due to the benefaction of the ‘Ministry of All the Talents’, in which his son was First Lord of the Admiralty. So only when he was 42 did Charles Grey become the heir to an Earldom at all.

Grey became a Whig, not by birth, but by association. After being educated at Eton and Cambridge, Grey headed to the continent for his Grand Tour. In his absence his uncle secured him, in 1786, election to parliament for the County of Northumberland. Aged just 22, Grey quickly fell under the spell of the charismatic Whig, Charles James Fox. He socialised with Fox and his friends; became a lover of Fox’s close friend, the Duchess of Devonshire; and imbibed Foxite doctrine. This essentially revolved around the belief that Britain’s ills were attributable to the excessive power of King George III, who had used corrupt patronage networks to unbalance the constitution at the expense of the House of Commons, British liberties, and British interests – as revealed in the mishandling of American policy and the loss of the American colonies.

Fox had every reason to feel sore at his handling by the King, who had engineered the dismissal of the Fox-North coalition government in 1783, installing William Pitt the Younger as Prime Minister, who proceeded to trounce Fox and his allies in the 1784 election. Fox thus found himself in opposition, where he and his dwindling band of followers would remain until 1806, when he had a few brief months back in office before his death. This was the context Grey encountered when he entered parliament. What is central to understanding Grey’s career is the resolution with which he stood by Fox through all Fox’s years in the wilderness and how, after Fox’s death, he struggled to keep the Foxite connection alive. It was only in 1830 that events conspired to offer him the chance to realise some, at least, of the Foxite ideals of the 1780s and 1790s.

Grey was remarkably loyal to Fox and generally endorsed his initiatives – even when he was sceptical of their wisdom. This was notably so during the Regency Crisis of 1788, when George III fell ill with incapacitating delusions. With the King unable to reign, the Regency of his son, George Prince of Wales, seemed inevitable. But the Regency question was not simply a constitutional one: it was profoundly political. George III had placed Pitt in power him and resolutely supported him, determined to prevent any prospect of Fox returning to government. The Prince was personally drawn to Fox, the two sharing a love for high living, socialising, and gambling; but he patronised him politically too, knowing how much it would infuriate his father. If the Prince were to secure the levers of power he would certainly dismiss Pitt and instal Fox in his place. The stakes were thus high and Fox seemed to hold the winning hand. Yet he played it clumsily. Although Fox is often labelled a Whig and Pitt a Tory, this is a mistake. If Fox were a Whig, so were most leading politicians, including Pitt – who always called himself an ‘independent Whig’. To be a ‘Whig’ politically meant to accept the Revolutionary Settlement of 1689 and to hold that the King was King in Parliament and ruled with and through parliament. It was this doctrine that allowed Pitt to turn the tables on Fox. For Fox (and Burke too) proclaimed that with the King incapacitated the Prince of Wales had a constitutional right to be appointed Regent with the power to appoint whatever government he wished. Pitt rejoined that the Prince had no such right; that parliament needed to agree and that it was proper that parliament should decide if and on what terms a Regency be instituted. Although Pitt was primarily playing for time, his interpretation of the constitution found more favour with the House of Commons than did Fox’s – and here it did not help that neither Fox nor the Prince were much liked or trusted. Fox’s call for a Regency appeared as opportunistic and self-serving as his alliance with North in 1783. Although Grey regretted Fox’s rash support for a Regency, he stood by him. The House of Commons, though, rallied around Pitt and agreed with him on the need to explore past-precedents for the establishment of Regencies – and then the entire issue was rendered academic as the King recovered his senses. What is so ironic about the entire episode is that Fox and Grey, who were usually so critical of the excessive powers of the King against Parliament, looked in 1788 to those very royal powers to catapult Fox into the premiership over the heads of MPs and the electorate. It is a reminder (in case one were needed) that we should be wary of looking to politicians for principled conduct – the scent of power is too alluring.

Charles James Fox

Grey was at one with Fox, too, in welcoming the French Revolution, believing that events in France would yield the kind of balanced ‘Whig’ constitution that Britain had long enjoyed. Indeed, they hoped the example of revolution in France would awaken calls for reform in Britain to curb the absolutist tendencies of King George. Fox and Grey clung doggedly to the virtues of the French Revolution despite mounting evidence of its cruelties and capriciousness, Grey blaming the excesses of the Revolution on the intervention in French affairs of the monarchies of Prussia and Austria. Not all Whigs were so indulgent towards the French revolutionaries. Edmund Burke detested the Revolution from its beginning and denounced it in extravagant and emotionally-charged terms, predicting violence and disaster. Burke had already been growing apart from his erstwhile ally Fox, but now their contrasting reactions to the Revolution and the discovery that Burke was actively seeking to persuade Fox’s more moderate allies like the Duke of Portland to break with him and join a National Anti-Revolution government with Pitt, brought a final schism. Grey could never forgive Burke’s intrigue. He disliked Burke and doubted his judgement, blaming him for many of the Whig’s misfortunes since the Fox-North coalition. Grey was in fact, for all his apparent equanimity of character, a great hater and more than capable of harbouring an indefinite grudge against someone. He disliked the Whig politician and playwright Sheridan, who he saw as his rival on the opposition benches and for being too close to the Prince of Wales, whom he also grew to hate. In later years he harboured deep-rooted animosity towards the Irish leader, Daniel O’Connell, and Radical leaders like Hunt and Cobbett. Above all, he detested Pitt, whom he always viewed as a manipulative and mendacious tool of George III’s absolutist ambitions. Dislike of Pitt was probably Grey’s defining political principle, and following Pitt’s death in 1806 he transferred that hatred to Pitt’s younger disciples, Canning, Castlereagh, and Lord Liverpool.

There were, however, two main ways Grey departed from the leadership of Fox. One was his willingness to reach out to Radicals in the country to advance the demand for political reform; the second was a growing disenchantment with political activity as such, which caused him to retreat from Westminster to family life in his Northumberland estate of Howick.

Fox was never a strong advocate of electoral reform. Yes, he used liberal and democratic language, but in practical terms his traditional Whiggism focused more on ‘economical reform’ to limit the patronage powers of the King, leaving the complex mediaeval electoral system alone. Grey, by contrast, saw the French Revolution and upsurge of demands for reform outside parliament as a means to re-build opposition to Pitt –seeking to use Radical calls for reform in the country as a lever to shift opinion within parliament towards accepting moderate change so as to head-off unrest and threats to property. To this end he joined with several other younger Whigs to form, in 1792, The Society of the Friends of the People – an upper-class organisation hoping to provide a bridge between Radicals in the country and reforming MPs to bring about change to the electoral system. Fox was sceptical and never joined the Society. In this he was more perspicacious.

Within months events moved against Grey’s plan. First, Tom Paine published the second part of his The Rights of Man. In this book he provided Radicals with powerful and principled arguments for democracy and the need to sweep away hereditary power in favour of a republic. Radicalism became more Radical in ways Grey, himself a member of the landed class, could not countenance. Grey was no believer in abstract human rights and shared the propertied-classes horror of democracy. As a result, his patrician Whig agenda appeared irrelevant to Paine’s followers in the Corresponding Societies that were spreading through the kingdom. At the same time, the French Revolution lurched further away from Whiggish constitutionalism towards chaos and violence, culminating, in January 1793, in the execution of King Louis XVI. The vast majority of MPs looked aghast at events in France. Burke, it seemed, not Fox or Grey, had read the Revolution correctly and his predictions of bloodshed were being played out before their eyes. Now was not the time to dally with French-inspired Radicalism within Britain. Worst followed in February 1793 when Britain was drawn into war with France. How could people like Grey advocate reform under the inspiration of ideas emanating from the country’s avowed enemy?

With Radicals moving to the Left, and moderates within Parliament moving to the Right, Grey’s projected bridge between the two groups collapsed. When he pushed on with his promise to raise the topic of parliamentary reform in May 1793 his motion was defeated by 282 to 41. Half his own side deserted him. When Grey tried again in 1797, this time with a more detailed set of proposals including giving the vote to all male householders paying rates in the boroughs, he was defeated again by 256 to 91. This defeat was the signal for Grey to abandon active politics altogether. He withdrew to Howick and did not appear in parliament for three years.

From this point on Grey was very reluctant to become engaged in politics at all. When Fox urged him to come south to join him in the Commons, Grey invariably declined, citing the difficulties of the journey and the needs of his frequently-pregnant wife. He even said he couldn’t leave his wife in case Napoleon invaded. For the next thirty years Grey took little direct part in Westminster politics, especially from 1807 when the death of his father saw him leave the Commons for the more stilted atmosphere of the House of Lords. He briefly took office as First Lord of the Admiralty and then Foreign Secretary when Grenville and Fox formed the ‘Ministry of All the Talents’ following Pitt’s death in 1806. But Fox died within months and not long after the government broke up after it offended George III with some confused proposals for allowing Catholics to hold officerships in the armed forces.

For the next 23 years Grey did barely enough to keep a parliamentary opposition in existence. There was little chance of a return to government. Hope flickered briefly in 1810 when the final madness of King George meant that the Prince at last became Regent on his behalf. But, with Fox dead, there were few links between the Prince and the Whigs,

and George was now more conservative and determined to see the war with France driven home to a victorious conclusion. Even so, Grey and his opposition ally, William Grenville, expected to be called upon to form a ministry and, when no call came, they indicated to the Regent their frustration. The Prince was in no mood to be dictated to and declared he would keep faith with his father’s appointment as Prime Minister, Spencer Percival. Fox’s old hope that the Prince would break the hold of the Pittites on power was over and the Grenvillites gradually abandoned the opposition and allied with the government.

Grey was thus left to observe as a bystander the government of Spencer Percival and then, following his assassination in 1812, the administration of Lord Liverpool. True to form, Grey hated Liverpool, who he saw as another agent of executive despotism. The government’s stringent response to the resurgence of popular unrest in the wake of the final defeat of Napoleon in 1815 only confirmed Grey’s belief in Liverpool’s dictatorial tendencies – but then he hated the Radicals too and had no wish to be associated with their agitation. He labelled their calls for universal suffrage and annual parliaments extravagant and delusional. ‘Can you have’, he asked a friend in 1819, ‘I will not say any confidence in their opinions and principles, but any doubt of the wickedness of their intentions? Look at the men, at their characters, at their conduct. What is more base, more detestable, more at variance with all taste and decency, as well as all morality, truth, and honour? A cause so supported cannot be a good cause.’1 As in the 1790s, Grey hoped the antidote to Radicalism without parliament was moderate reform within, but few were listening and once the crisis years of 1815-19 had passed Liverpool’s government settled down to a programme of economic reform and national revival. It appeared that Grey’s career would gradually subside with nothing tangible to show for it.

But then the Tories do what the insist upon doing every few decades – they imploded into civil war. It began when Liverpool was forced by a stroke to retire as Prime Minister in 1827. Canning was appointed his successor – only to be abandoned by several leading figures such as Wellington and Peel. It mattered little for within a few weeks Canning was dead. Lord Goderich attempted to form a government but resigned before ever facing parliament. The Duke of Wellington stepped up to the mark, but was soon confronted with a crisis in Ireland over O’Connell’s agitation for Catholic Emancipation. Despite its flaunted opposition to Catholic Emancipation, Wellington’s government gave way and lifted the remaining disabilities relating to Roman Catholics, including allowing them to sit in the House of Commons. High Tories denounced Wellington as a traitor and his position weakened. It weakened still further with the general election of 1830 called upon the death of George IV. Attempting to re-secure support from the Right of the party, Wellington unequivocally rejected any suggestion of parliamentary reform. But this only led Liberal Tories to abandon him as well. Haemorrhaging support to Right and Left, Wellington’s Tory government collapsed. The new King, William IV (who like his brother George had thought of himself as Whig in his younger days), had no hesitation in calling upon the now sixty-six year-old Earl Grey to form an administration. Grey was Prime Minister for the first time.

When Grey assumed office in 1830 he did so with the clear intention to pursue a measure of parliamentary reform. He had, of course, been personally committed to parliamentary reform since the early 1790s, and since then the case for reform had only grown with the blatant corruption in over one hundred small, sometimes Rotten, boroughs in the rural south of England, while new industrial centres like Manchester and Birmingham had not a single MP. The rapidly expanding middle class was under-represented, and Grey feared that they might yet make common cause with working class Radicals to challenge the pre-eminence of the landed elite and the monarchical order. Catholic Emancipation showed reform was possible. Now it was time for parliament to reform itself on its own terms.

Grey’s role in the reform process was threefold. First, he assembled and led a government committed to reform. This was not easy as the Whig opposition had been out of power for nearly fifty years. As an aristocrat and patrician, he was able to reassure doubters in parliament that he would proceed cautiously, forming a coalition government that included liberal Tories like Palmerston, Melbourne, and Graham. Although he delegated the drawing up of the details of the measure to a committee, he himself kept a firm hand on the proposals, steering a course between excessive timidity or radicalism.

Second, Grey oversaw the presentation to parliament of a Reform Bill that was thoroughgoing yet did not fundamentally break with the British parliamentary tradition. Grey rejected calls for universal suffrage, annual parliaments, or secret voting. He drew back from the idea of a household rate-payer franchise that he had floated in 1797, opting instead to give the vote in boroughs to heads of households paying £10 per annum in rates. In this way only those with significant property would get the vote. Nearly all constituencies with less than 2000 voters were to lose their MPs, while boroughs with 2,000 to 4,000 voters were to be reduced from two to one MP each. The 168 seats thus freed up would be given to London and the Counties, while seven of the new industrial towns were to get MPs for the first time. While Tories like Peel were initially shocked at the extent of the changes, in truth the substance of the old electoral system remained. The traditional conception that parliament reflected the interests of the nation was retained – there no attempt to mathematically relate population to representation. The County franchise changed little and the south was still significantly over-represented by MPs compared to the north. The working class were largely excluded from the vote. Even the existing electorate supported the proposals, and when a general election was called in 1831 after the initial proposals were blocked by the House of Commons the government’s majority increased from just one to 136. There was increasing recognition that Grey was true to his word: he was reforming to preserve.

Third, Grey held his nerve throughout the tortuous and sometimes tempestuous process of guiding the reform proposals through parliament. The most dangerous point of controversy arose over the attempts of the House of Lords to block the measure. There were calls for the King to create a sufficient number of Whig peers to break the Lord’s resistance and vote the measure through. But Grey, a Whig peer himself, had no wish to dilute the Lords and compromise its position within the constitution.

He delayed as long as he could from approaching the King to suggest this last resort and when, he could no longer avoid doing so, he did so in as cautious and reassuring manner as possible. His patience was rewarded. William agreed to create a sufficient numbers of Peers to pass the Bill but only if the Lords rejected it once more. The threat alone was sufficient: the Lords backed down and passed the Bill, with the result that the Reform Act became law in 1832.

With the passing of the Reform Act Grey realised his vision of strengthening the House of Commons by placing its electoral arrangements on a defensible basis and incorporating the bulk of the middle class into the political nation while firmly excluding the working class and Radical demands for democracy. The Reform Act was soon accepted as a wise measure by both sides of the House of Commons: in 1834 Robert Peel publicly avowed that the Conservative party had no wish to reverse it.

Grey’s premiership lasted for two more years and included such foundational measures as the abolition of slavery in the British Empire and the passage of the first serious Factory Act regulating the hours of work of children. But Grey’s energy and authority ebbed now his chief work was done and relations within the Cabinet became more fractious.

Inevitably it was Ireland that brought down Grey’s government – as it has brought down so many governments over the last two hundred years. Despite Catholic Emancipation, unrest in Ireland continued, with O’Connell now raising demands for Irish independence from the UK. Grey saw the need to maintain the Coercion Acts that were used to strengthen law and order measures in Ireland, and when he found out that members of his government were secretly conspiring to water-down the measures and had been liaising with O’Connell (who figured prominently on Grey’s hate list) Grey resigned as Prime Minister in July 1834.

Grey had never sought office with enthusiasm. Even during the prime of his political life he had preferred to reside at his country house in Northumberland and live privately with his wife and family, and so to Howick Hall he returned in 1834. Just as Grey had not entered the world as a Whig, now in his final years he drifted away from the Whig government and its Radical, Irish, and utilitarian allies. He was less in sympathy with the Whigs and more often found himself agreeing with Peel and Wellington. Disraeli once described Peel’s Conservatism as ‘Tory men and Whig measures’. By the time of his death in 1845 Grey found that formula very much to his taste.

By Ashleigh Teper

Lady Jane Grey was only 16 years old when her dying cousin (Edward V1) requested the throne to be passed to her. She is the shortest reigning monarch is British history, with her reign lasting only 9 days. Highly unpopular and uncredited, Lady Jane Grey’s story has remained in the shadows of British history and her contribution has stayed hidden.

Lady Jane Grey was born in autumn 1537 (her actual birthday is unknown) and died only 16 years later on February 12th 1554. Her great uncle (Henry V111) left the throne to his only male heir Edward V1, who passed away at only 15 years old from tuberculosis. Having always been a sick child, Edward feared the throne may eventually end up passing to his oldest sister Mary 1 if he were to pass away, and this consequently would mean the country may became Catholic as Mary and her mother Catherine of Aragon were strong Catholics (while Edward and his other sister Elizabeth were protestant as well as the rest of the country). For this reason, Edward chose to request for his younger cousin Lady Jane Grey to be crowned after him instead of Mary. At 16 years old, Lady Jane Grey was crowned Queen of England following Edward’s abrupt death, enraging Mary and leading her to the decision (despite her father and brother’s wish’s) to pursue her right to the throne.

Before the passing of Edward V1, Lady Jane Grey had led her own life, without the knowledge of her cousin Edward’s intentions. On 25th May 1553 (aged 16), Lady Jane Grey married her husband – 18-year-old Guildford Dudley.

Lady Jane Grey was crowned only 4 days after Edwards V1 death, with her reign starting on the 10th July until the 19th July. On the 10th July, Lady Jane Grey is introduced to life as queen while she awaits her coronation, which is on the 3rd day of her reign. After her coronation, Lady Jane Grey was encouraged to meet the public, however she was met with masses of hate and little support, as the public expected someone else as their queen and she became very disliked. On the 4th day, she wrote a letter to Mary 1, asking her approval and acceptance as the queen, but on the 5th day she received Mary’s reply in which she denied the acceptance and instead began to plan her overtake of the throne against Lady Jane Grey. Mary 1 had been building an army to declare battle against Lady Jane Grey and have her removed as queen.

The following days, Mary’s army was successful in defeating Lady Jane Grey’s attempt to stop her. Gradually, all remaining supporters of Lady Jane Grey fled or supported Mary out of fear in an attempt to save themselves. Left with no support from the public, Mary easily defeated Lady Jane Grey by accusing her of treason and having her arrested, limiting her reign to 9 days.

On 12th February 1554, Lady Jane Grey and her husband were executed. In the morning, Lady Jane Grey watched her husband being carried from the tower but denied his request to see him one last time. Two hours later, Lady Jane Grey was carried from the tower and led to be executed. She was only sixteen years old. It was noted that she was blindfolded and instructed to place her head on the block. However, out of fear, she struggled to find the box and started to panic, requiring help to find the block. Her final words were said with her arms stretched up to the sky ‘Lord, into thy hands I commit my soul’.

As such a disregarded and short reigning queen, Lady Jane Grey is often forgotten in today’s modern world. Ranging from school curriculum to politics, the memory of Lady Jane Grey is often left out, resulting in our future generations total disregard of her life. As an accomplished young women, who had to instantly fill the shoes of her cousin at only sixteen years old, she shouldn’t be forgotten, but celebrated. Lady Jane Grey fought until the very end of her life and tried her best to provide her country with support and a worthy queen. Today’s society will have us believe she was an unpopular and worthless monarch, but underneath the hatred and lack of support is a young teenager who was frightened and given an overwhelming responsibility. As a key monarch in British history, Lady Jane Grey should be displayed as an inspiring queen, who fought till the end of her life.

By Ameya Barot

Pitt the Younger and Gladstone were two prime ministers who were strong believers of free trade. Pitt was prime minister during the Napoleonic Wars until his death in 1806 and Gladstone was the chancellor of Exchequer during the Crimean War 1853-56. Both prime ministers adopted similar tactics, such as raising income tax, but ultimately Pitt was the better war financier, because Gladstone was able to use his ideas and learn from his mistakes.

One way in which Pitt was a good war financier was him introducing income tax. The government needed more money to pay for weapons and allies. This was better than borrowing money, because it did not contribute to the increase in the national debt. It is also a direct tax, so does not rely on spending, which means that the government is guaranteed to receive revenue through it. Furthermore, income tax ensures that the rich pay more than the poor, so it does not increase starvation and suffering and it reduced income inequality. Income tax was 10% for those with an income between £60 and £200, and 20% for people with an income over £200. The poor are more likely to resort to radicalism, so income tax reduced the likelihood of there being mass amounts of unrest. The income tax raised over £6million in 1799, which proves how effective the measure was. However, the tax was very unpopular, especially with the middle classes. It was seen as an invasion of privacy as it allowed state interference in private affairs. However, it did help the country’s financial recovery significantly and it was meant to be a wartime measure, so was not fought against that much.

Another reason why Pitt was the better war finance is he invested in the navy. Before the war, his administrative reform ensured that money was used more wisely to strengthen the military and the navy in particular. This was very important, because since Britain is an island, these adjustments resulted in Britain having a better chance during the war. By 1790, the Royal Navy had 33 new ships. Pitt investing in the Navy was very successful, because Naval supremacy protected Britain during the war with France. For example, in 1797, in the Battle of Cape St Vincent, the British navy defeated the Spanish navy, which prevented Spain from supporting France at sea until 1803. This significantly increased Britain’s chances in the war. Additionally, Admiral Horatio Nelson defeated France’s naval force in 1798 on the Nile, which encouraged Austria and Russia to form the Second Coalition with Britain. This means that Pitt’s investment in the British navy was also important, because it ensured Britain had allies later on. France was unable to defeat British naval power, making it impossible to invade Britain. Because the navy was strong, Pitt’s war time policy of the Blue Water strategy was also successful.

This strategy ensured Britain’s economic interests were protected, so Britain could carry on fighting in the war. Britain’s navy captured the Cape of Good Hope and Ceylon, which became important trading posts and by the 1800s over half of British exports went to the Americas. Although Napoleon attempted to destroy British trade through blockades, Pitt’s forward thinking enabled Britain to trade with the Americas instead, making him the better war financier.

On the other hand, Pitt was a bad war-financier, because he continued using the sinking fund during the war, which made things worse. When Pitt initially attempted to reduce the national debt using the sinking fund in 1786, it was successful as it reduced the national debt by £10million. The sinking fund involved the government putting extra money into a separate fund and this money was used to buy government bonds on the stock market. The profits from these bonds were used to reduce the size of the national debt, which made Britain more stable and resulted in more nations trusting Britain’s financial status enough to trade with Britain and markets become more willing to lend to the UK government. However, although Pitt’s introduction of the sinking fund proved he was a good financier, it provides evidence that Pitt was a bad war-financier. The war increased government spending and borrowing significantly, as there was high demand for weapons and uniforms, which also resulted in demand pull inflation. The national debt was rising so fast that the sinking fund could not keep up with it. This meant that the government had to borrow money to pay for the sinking fund. Interest rates were high, because there was inflation. Since interest rates were high, borrowing money to fund the sinking fund cost more money than was gained in using the sinking fund. By 1801, the national debt had increased by 87% to £456 million, which proves how damaging Pitt’s policy turned out to be.

Another reason why Pitt was not a good war-financier is that the Industrial Revolution was happening during the French war, so Britain’s financial success was ultimately due to the Industrial Revolution, not Pitt. The annual growth of industrial output increased to 3 to 4 % from the long term level of 2% in 1780. This ensured that Britain was still undergoing positive economic growth during the war. A consequence of the Industrial Revolution was that in 1800 one farmer was producing enough to feed 2.5 people, whereas a century earlier the average was 1.7. This meant that when resources were pulled away from agriculture because of the war, a sufficient amount of food was still able to be produced because of the advanced farming techniques and machinery created during the Industrial Revolution. The Industrial Revolution was not caused by Pitt; it resulted from Britain running out of wood and being forced to switch to coal as its main source of energy, as well as Britain having high literacy rates, inflation and pressure of war finance.

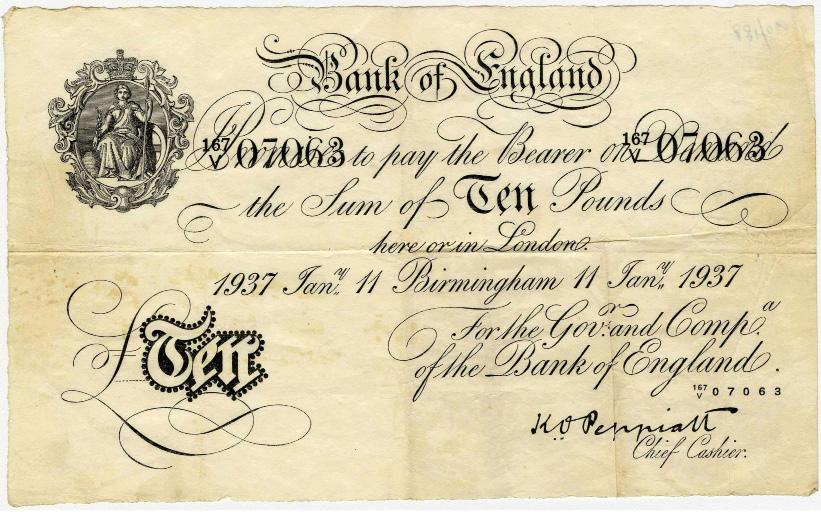

A final reason in which Pitt was a bad war-financier is that he abolished the gold standard, enabling the Bank of England to print too many bank notes, as he lifted the restriction on printing paper money. This led to high and unstable prices, which was negative as it increased income inequality and reduced investment and economic growth as the instability resulted in negative animal spirits. Income inequality increased, because the landed classes benefitted from the higher prices as they could charge higher rents as the farmers earned more money. However, the working class suffered from these high prices; in 1793 the price of wheat was 47 shillings a quarter.

On the other hand, Gladstone was a good war financier, because he made an effort to cover a large portion of the cost of the war with increased taxation, as opposed to borrowing, like Pitt did. He said in a speech in March 1854 that he would learn from Pitt’s experience and attempt to raise money through taxation, so the national debt would not increase too much. Gladstone wanted to maintain national credit and imposed new and heavy taxation as a result. Most of the burden of the war was placed on Income tax, which was increased from 7d to 10.5d and then to 14d and the tax would continue at the increased rate while the war lasted. Indirect taxation was also raised; spirits, malt and sugar were additionally taxed. Indirect taxation would produce around £3,200,000. The overall cost of the Crimean War came to around £70 million, of which £38million was paid for with immediate taxation and £32million was added to the debt. This proves that Gladstone was a better war financier than Pitt, because he paid for the majority of the war with taxation, as opposed to borrowing vast amounts of money and adding to the national debt.

However, ultimately Gladstone was a champion of free trade and took any excuse to cut taxation when he could. This made him a bad war financier, because after the war taxation should have been held high, so the national debt could be cut. The public wanted a reduction of taxation instead of a repayment of debt, so in 1860 Gladstone applied two million to cutting taxes, which previously had been applied, and should have been reapplied, to the annual reduction of the national dent. The economy was not predictable, and if the Crimean war debt was not met immediately, it was unlikely that any government would be able to reduce it afterwards. The suspension of the double sinking fund also resulted in finances being in a much worse position. Therefore, Gladstone was not a good war financier, as he did not focus on paying off the national debt after the war.

Another reason why Gladstone was a bad war financier, is that he did in fact borrow money. He just refused to label this borrowing of money as a loan. On the 21st April, the treasury offered for sale £6million of Exchequer bonds, repayable in three series of £2million each in 1858, 1859 and 1860. He was attacked for inconsistency, as Gladstone made it clear he wanted to finance the war through taxation, but he still accepted the bonds. Gladstone claimed the bonds were ‘no loan, but a provision for the temporary raising of money’ and evaded the subject, which makes him a bad war financier, as he did not keep the people properly informed. These exchequer bonds later added to the national debt, because they were not paid off. His use of Exchequer Bills are another example of where Gladstone added to the national debt. In 1855 the Exchequer Bills Bill for that year added the £1,750,000 of Exchequer Bills to the Exchequer Bills annually renewed, although Gladstone had said they would be paid off as soon as taxes came in. This meant that these Exchequer Bills became permanent debt, although Gladstone never announced the change in the nature of these bills. This proves that, although Gladstone might have planned to fund the war through taxation, he did borrow money and tried to conceal this fact as much as possible.

Gladstone was also a bad war financier, because a deficit of £2million had accumulated by the time Gladstone left the office in February 1855. This proved that Gladstone was not a great financier, because his decisions resulted in a deficit. Gladstone also did not have any innovative strategies for financing the war, whereas Pitt invested in the navy, which proved to be very useful and Pitt also introduced income tax as a concept, whereas Gladstone only raised it. Gladstone’s main strategy was to raise taxes, which Pitt did too.

After the Crimean War, there was an increased funded and unfunded debt of £40,000, whereas the Napoleonic War increased national debt by £850,000,000. This implies that Gladstone did a much better job at financing the war than Pitt did, although it is important to take into account that the Crimean War lasted for less than three years, whereas the Napoleonic Wars lasted for 20 years. However, £850,000,000 is still much more than five times £40,000, so it is still safe to say that Gladstone was better at controlling debt than Pitt was. The image provides further evidence of how the Napoleonic War which ended in 1815 resulted in a far higher national debt as percentage of GDP (270) than the Crimean war which ended in 1856 and resulted in a national debt as a percentage of GDP of 110.

Overall, Pitt was the better war financier. Pitt was more innovative and introduced income tax in the first place, as well as making reforms to the navy. Gladstone’s main strategy was raising income tax and direct taxes, which is what Pitt did already. The main thing that Gladstone did that was better than Pitt was being careful not to borrow and increase the national debt as much, but the only reason why he knew to be cautious with borrowing is that he had the luxury of being able to learn from Pitt’s mistakes. Furthermore, Gladstone did still borrow money in the form of bonds and Exchequer bills, so he did not even really learn from Pitt’s wrongdoings. Pitt also had to organise finances for a longer and more intense war; the Napoleonic wars lasted for twenty years, whereas the Crimean War lasted for less than three years. This also makes me conclude that Pitt was the better war financier.

“A leader is a dealer in hope.”

By Richard Zhou

The legacy of Mao Zedong is one of history’s most contested. Pro-Maoists claim that his profound social reforms for women and peasants and strengthening of national security show Mao’s leadership as a golden era for China. However, critics claim that his disastrous policies in the Great Leap Forward (GLF) costing tens of millions of lives, and his initiation of sociopsychological destruction in the Cultural Revolution unmask Mao as a disastrous leader. This essay aims to evaluate Mao’s overall effect on the Chinese people by assessing the GLF, Mao’s policies on women’s rights, the Cultural Revolution, and Mao’s land reform era, and show that ultimately the benefits from Mao’s social reforms are simply dwarfed by the sheer scale of destruction his GLF and Cultural Revolution caused.