GEORGE WASHINGTON’S

“I think we are in an exceeding dangerous situation.”

GEORGE WASHINGTON’S

“I think we are in an exceeding dangerous situation.”

IN THE SUMMER OF 1775, THE GENERAL HAD REAL DOUBTS ABOUT HIS ABILITIES AND THOSE OF THE CONTINENTAL ARMY

Immerse yourself in history with military drills and lively encampments, May 3–4. Free for Mount Vernon members. mountvernon.org/revwarweekend

Taste unlimited samples of wines from Virginia’s finest wineries, May 16–18. Tickets are discounted for Mount Vernon members. mountvernon.org/springwine

CONSULTING EDITOR: Norie Quintos

DESIGNER : Jerry Sealy

VICE PRESIDENT, MEDIA AND COMMUNICATIONS: Julie Almacy

CREATIVE DIRECTOR: James B. Hicks III

EDITORIAL COORDINATOR: Breck Pappas

VISUAL RESOURCES: Dawn Bonner

PROOFREADER: Lorna Notsch

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS:

Dawn Bonner

Margaret Loftus

Cheryl Marling

Kristen Otto

Breck Pappas

Mount Vernon magazine is published three times a year by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, the nonprofit organization that owns and manages George Washington’s estate. We envision an America where all know and value the singular story of the father of our country. Ever mindful of our past, we seek innovative and compelling ways to tell the story of George Washington, so that his timeless and relevant life lessons are accessible to the world.

This publication is produced solely for nonprofit, educational purposes, and every reasonable effort is made to provide accurate and appropriate attribution for all elements, including historical images in the public domain. All written material, unless otherwise stated, is the copyright of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association. While vetted for accuracy, the feature articles included in this magazine reflect the research and interpretation of the contributing authors and historians.

George Washington’s Mount Vernon P.O. Box 110, Mount Vernon, Virginia 22121

All editorial, reprint, or circulation correspondence should be directed to magazine@mountvernon.org. mountvernon.org/magazine

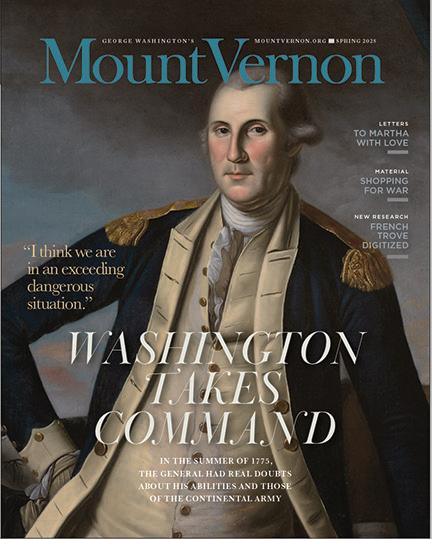

This is a zoomed-in image of a replica by Charles Willson Peale of his popular 1779 official portrait of General Washington. In the original portrait, Washington wears a blue sash, the insignia of the commander in chief since 1775. Washington later eliminated the blue ribbon. Peale clearly had started the present portrait earlier, as a long blue sash, painted out by the artist at a later date, today shows through. (See pages 27 and 31.) Portrait: Given by the Associates in Fine Arts and Mrs. Henry B. Loomis in memory of Henry Bradford Loomis, B.A. 1875, Yale University Art Gallery

In the summer of 1775, George Washington felt woefully unready to take on the enemy PLUS: Timeline of a revolution

By Rick Atkinson

22 | From the Heart

Love notes from the new commander of the Continental Army to his wife

By Samantha Snyder

| The Wartime Kit

The general’s wardrobe and equipment choices

By Amanda Isaac

A long-hidden trove of Revolutionary War–era papers reaches the digital age

4 | News

New Revolutionary War encampment, mini Mount Vernon aboard the USS George Washington, electric vehicles added to the fleet, and more

10 | Focus on Philanthropy

Entrepreneur Tom Hand so believes in the importance of history education that he puts his money behind it

38 | Washington in the Classroom

A middle-school teacher in Sunnyvale, California, helps students connect history and current events

40 | Shows of Support

George Washington’s 293rd birthday events and an update on the Strengthening Our Foundations campaign

44 | Featured Photo

A circa 1920s stereograph showcases an elm in Boston Common, under which Washington took charge of the Continental Army, or so the story goes

George Washington’s Mount Vernon estate is owned and maintained in trust for the people of the United States by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association of the Union, a private, nonprofit 501(c)(3) organization founded in 1853 by Ann Pamela Cunningham.

THE MOUNT VERNON LADIES’ ASSOCIATION

Anne Neal Petri, Regent

Susan Marshall Townsend, Secretary

Catherine Marlette Waddell, Treasurer

Maribeth Armstrong Borthwick, California

Ann Haunschild Bookout, Texas

Virginia Dawson Lane, South Carolina

Laura Peebles Rutherford, Alabama

Susan Marshall Townsend, Delaware

Liz Rollins Mauran, Rhode Island

Ann Cady Scott, Missouri

Sarah Miller Coulson, Pennsylvania

Andrea Notman Sahin, Massachusetts

Catherine Hamilton Mayton, Arkansas

Margaret Hartman Nichols, Maine

Helen Herboth Laughery, Wyoming

Catherine Marlette Waddell, Illinois

Lucia Bosqui Henderson, Virginia

Mary Lang Bishop, Oregon

Elizabeth Medlin Hale, Georgia

Ann Sherrill Pyne, New York

Hilary Carter West, District of Columbia

Karen McCabe Kirby, New Jersey

Adrian MacLean Jay, Tennessee

Sarah Seaman Alijani, Colorado

Susan Brewster McCarthy, Minnesota

Carolyn Sherrill Fuller, North Carolina

EXECUTIVE STAFF

Douglas Bradburn, PhD, President & CEO

Julie Almacy, Vice President, Media & Communications

Joe Bondi, Senior Vice President, Development

Lindsay M. Chervinsky, PhD, Executive Director, George

Washington Presidential Library

Joan Flintoft, Vice President, Hospitality

Phil Manno, Chief Financial Officer

Joseph Sliger, Vice President, Operations & Maintenance

K. Allison Wickens, Vice President, Education

We would like to take you back 250 years to a pivotal moment in our nation’s history: George Washington’s appointment as commander in chief of the Continental Army. Standing before the Continental Congress on June 16, 1775, Washington professed that his “abilities and military experience may not be equal to the extensive and important trust. However, as the Congress desire it, I will enter upon the momentous duty and exert every power I possess in their service and for the support of the glorious cause.” In just a few words, Washington demonstrated the humility, resolve, and dedication that would define his leadership throughout the Revolution.

In this issue, we explore the profound challenges Washington faced in his new role and the ways in which his character shaped the fight for independence. In our opening feature, Pulitzer Prize–winning historian Rick Atkinson captures the daunting task of transforming a ragtag militia into an army capable of taking on the world’s mightiest military power. Atkinson highlights how Washington’s vision and determination became cornerstones of the Revolutionary effort.

Samantha Snyder, research librarian at the Washington Library, provides an intimate glimpse into Washington’s personal life through two surviving letters to Martha Washington. Written as he prepared to leave for Boston, these poignant letters reveal his deep affection and concern for his wife, as well as his sense of destiny in accepting command and his sober view of the challenges he would face. Miraculously, these letters escaped destruction when Martha ordered much of their correspondence burned late in her life, offering a rare window into their marriage.

Finally, Mount Vernon curator Amanda Isaac takes us into the material world of George Washington’s wartime life. As Washington went to war, he made sure to look the part, and now these personal witnesses to revolution— including his uniform, trunk, and the camp tent where he shared the hardships of his soldiers—tell a powerful story. They shaped his image as a citizen-leader and embodied the values of a fledgling nation.

As we approach the 250th anniversary of American independence in 2026, we are excited to mark the

Revolution’s milestones in our running Revolutionary timeline, which begins in this issue on page 20. We also invite you to visit Mount Vernon, where we recently unveiled Patriots Path, a Revolutionary War encampment supported by Americana Corner. This immersive experience offers visitors a glimpse into life in the Continental Army, with reproduction tents, hands-on activities, and interpreters sharing stories of the Revolution. As time unfolds, Patriots Path will evolve to reflect key anniversaries, offering fresh perspectives on this decisive period in history.

This is a moment to reflect on our nation’s founding ideals and the extraordinary individuals who made them a reality. Put Mount Vernon on your bucket list of places to see in these anniversary years. I look forward to welcoming you here soon.

Warm regards,

President and CEO

On the grounds of Mount Vernon, a Revolutionary War encampment springs to life

As visitors walk through rows of canvas tents to the sounds of bugle calls and musket fire, they leave the 21st century behind. Patriots Path, a hands-on, immersive experience, helps people imagine what life may have been like in the Continental Army during the American Revolution.

The experience, which debuted this spring and will continue through at least the next few years, re-creates a Continental Army infantry company encampment with reproduction tents and periodappropriate equipment. Guests can explore soldiers quarters stocked with essential gear, try their hand at laundry in the wash yard, and visit the officers’ tent, which features maps and documents highlighting Revolutionary War events. In 2025, the focus includes the Battles of Lexington and Concord, as well as

other key moments from the pivotal year of 1775.

Interpreters stationed throughout share insights into camp life, the hierarchy between soldiers and officers, and the contributions of civilians in the camp. Scheduled programs such as cooking and musical demonstrations further bring the era to life.

“It’s an opportunity for visitors to connect with the experiences of those who fought for American independence,” says Zerah Jakub, senior manager of education operations. “It reflects Mount Vernon’s commitment to inspire a deeper understanding of the nation’s founding.”

Patriots Path is open daily and is included in the cost of admission. The experience is made possible by support from Americana Corner (see page 10). To learn more, visit mountvernon.org/patriotspath. H

Time travel: A row of replica tents gives visitors a glimpse of life in the Continental Army (opposite). Clockwise from above left, a child peers into a camp tent; cooking demonstrations showcase how meals were prepared in a Revolutionary War encampment; reenactors with period equipment and attire stroll through the encampment; and everyday objects, such as a deck of cards, highlight the ways Continental soldiers passed the time and built camaraderie.

Wisconsin is the 24th Regent of the Mount

On October 5, 2024, Black Women United for Action (BWUFA) and Mount Vernon hosted the annual Slave Memorial Commemoration. A highlight included a wreath-laying ceremony at the Slave Memorial, located approximately 50 yards southwest of George and Martha Washington’s tomb. This sacred ground was used as a cemetery for those enslaved on the plantation and a few members of the free black community who worked at Mount Vernon in the 18th and 19th centuries.

The event was led by Alotta Taylor, BWUFA treasurer, and featured a custom wreath (below) presented by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association. Designed by botanical artist Valencia Wilson, the wreath symbolizes the resilience of the enslaved through materials they once harvested. “Each element speaks to their enduring legacy,” Wilson said, “with wheatgrass and millet representing sustenance, okra signifying cultural heritage, and flax embodying the strength and versatility they displayed in the face of adversity.” Watch the ceremony at mountvernon.org/slavememorial. H

Caption Tk

Two electric-powered shuttles added to Mount Vernon fleet

Mount Vernon has added two electric shuttles (above) to its fleet, enhancing accessibility and convenience for guests. These eco-friendly vehicles, a 14-passenger shuttle and an 11-passenger wheelchair-accessible model, resemble oversize golf carts.

“Accessibility is a core value at Mount Vernon, and these shuttles will help improve our guests’ ability to experience some of our most important sites, such as Washington’s Tomb and the Slave Memorial, which are located in physically challenging areas on the estate,” says Astrid DeJesus Rivera, Mount Vernon’s associate director of Guest Services.

The shuttles will be deployed seasonally, from April through November, to operate a continuous loop incorporating the 12-acre field, the Tomb, and the Wharf. “Catching a ride is as easy as flagging down the driver,” DeJesus Rivera says, “and service will be provided on a first-come, first-served basis.”

For shuttle schedules and availability, visit mountvernon.org/shuttle. H

Two events last fall promote founding ideals

Last September, Mount Vernon hosted its annual Founding Debates program, held every year to mark the anniversary of the Washington Library’s opening.

Co-hosted with More Perfect, a nonpartisan consortium of civic institutions, the event focused on five goals for democratic renewal ahead of the nation’s 250th anniversary. With nearly 300 guests in attendance, expert panelists Danielle Allen, Manu Meel, and Dale Anglin, along with former U.S. representative Zach Wamp and retired U.S. general Stanley McChrystal, led discussions on rebuilding trust and strengthening democratic principles.

The following day, the Library hosted More Perfect’s second general meeting, uniting representatives from presidential sites and civic institutions to evaluate progress on these goals. H

Mount Vernon initiative expands public access to Revolutionary-era maps

Mount Vernon’s Center for Digital History is making groundbreaking strides with ARGO: American Revolutionary Geographies Online, a project transforming public access to historical maps of North America. Since its launch in November 2022, ARGO has brought together an impressive collection of more than 4,000 maps from the 18th century, sourced from 28 dedicated partner institutions.

Among its featured collections is the Richard H. Brown Revolutionary War Map Collection, housed at the George Washington Presidential Library at Mount Vernon, alongside maps from the Norman B. Leventhal Map and Education Center at the Boston Public Library. The

latest additions come from the MacLean Collection—a renowned private archive of rare maps focusing on the Americas—digitized specifically for ARGO

More than a repository, ARGO is a source of interpretive content. Recent highlights include an interactive breakdown of the 1775 Battle of Sullivan’s Island and pre-recorded map talks.

Mount Vernon plans to expand ARGO further this year, incorporating materials from at least seven new partner institutions. Among the forthcoming additions is a remarkable selection of 112 maps from the Royal Danish Library in Denmark.

Explore the collection at argomaps.org. H

Mount Vernon donates replica pieces for display aboard the USS George Washington

Where’s the newest museum on George Washington? It might just be the one aboard a nuclear-powered Nimitz-class aircraft carrier, the USS George Washington, currently deployed in Yokosuka, Japan.

The ship recently underwent a multiyear modernization process in Norfolk, Virginia, during which Mount Vernon helped create an onboard museum dedicated to the life and legacy of George Washington. The museum features several replica pieces donated by the estate, including Washington’s Acts of Congress, examples of Washington’s china, and a copy of the Bastille key—a symbol of liberty gifted to Washington by the Marquis de Lafayette. Additional donated items include a framed copy of Charles Willson Peale’s iconic porthole portrait of Washington and an 1870 image of members of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, the earliest known depiction of the group that preserved Washington’s home.

Timber harvested from the grounds of Mount Vernon was crafted into museum display shelves in the ship’s onboard carpentry shop, further connecting the museum

to the president’s historic home. “The museum not only honors the legacy of Washington,” said Mount Vernon president and CEO Douglas Bradburn, “but also serves as a testament to the enduring connection between his ideals of leadership and service and the men and women who walk in his footsteps, serving the nation on this great and worthy ship.” H

Expanding portal: Newly digitized maps from the Illinois-based MacLean collection were added to ARGO: American Revolutionary Geographies Online, bringing the total number of maps on the portal from that institution up to 335. Quiet welcome: A “sensory-friendly family morning” held on September 21 was the highest attended since the ongoing program’s inception in 2018. Neurodivergent guests and their families visited the estate before opening. Specially trained staff provided a quieter experience, self-paced Mansion tours, sensory bags, and a “take a break” room. Preserving species: A steward of heritage breed animals, Mount Vernon collaborated with the National Animal Germplasm Program through its Livestock team to donate tissue samples from its heritage breeds for preservation in a central DNA bank. Students of the year: Sachin Saravanan, a highschooler from Jacksonville, Florida, and Katie Wurst, a middle schooler from Falls Church, were the 2024 recipients of the Mount Vernon Prize for Excellence in Civics and History in Honor of Dr. Jennifer London. H

BY

THE NUMBERS

12 Mansion rooms deinstalled in preparation for the second phase of the Mansion Revitalization Project.

1,000

Nails created by Mount Vernon blacksmiths for various needs in 2024, including for sale at The Shops.

16 Years that Aladdin the camel has been coming to Mount Vernon for the holiday season.

A new digital feature brings the Revolutionary War to life as it happened 250 years ago. The interactive “Washington Day-to-Day” timeline, which debuted on January 1, follows George Washington’s daily activities—beginning on the same day in 1775—through his letters and diaries. Updated daily on Mount Vernon’s website and displayed in the Ford Orientation Center, the timeline provides an intimate glimpse into Washington’s world—from the guests he hosted at Mount Vernon to the minutiae of managing the Continental Army. Each day’s entry links to Washington’s full letters and Mount Vernon’s digital resources, offering unparalleled insight into the Revolutionary War and the life of its American commander.

SEE WHAT WASHINGTON WAS DOING ON THIS DAY AT MOUNTVERNON.ORG/ WASHINGTONTODAY.

Tom Hand was 10 years old when his mother gave him a pictorial atlas of the Civil War for Christmas, sparking a lifelong interest in American history. “That’s the first time I thought, ‘I like this history stuff,’” he says. “It’s stayed with me ever since.”

It wasn’t until a visit to Mount Vernon, however, that he discovered the period that would inspire his second act in life. He and his wife, Char, who together ran the family cheese business in Wisconsin, had become involved with Washington’s estate philanthropically and had been invited to stay onsite. “I remember getting up at 6 a.m. and going to the piazza, and there was a mist over the Potomac, and I realized, ‘Oh wow, I’m in love with this place,’” Hand says. “From there, I started looking more into the American Revolution and learning about the founding era. Since then it’s become a passion of mine, my ‘retirement gig,’ so to speak.”

After he and Char sold their company, Hand began writing articles about history for the Bryan County News, a small newspaper outside Savannah, Georgia, where the couple had moved. Hand enjoyed it so much that he launched a website, Americana Corner, as a way to teach U.S. history. The site shares engaging digital content and books, and it also supports small history nonprofits by providing grants and a forum to share information. “Mount Vernon happens to be my favorite history nonprofit, but there are a lot of mini Mount Vernons out there with missions to educate the public, so I thought I could use my dollars to help them,” he says.

To that end, last fall Americana Corner hosted its first-ever Preserving America Conference, aimed at

empowering battlefield park partners and historical sites with the tools to achieve greater sustainability. The conference hosted 22 organizations to discuss fundraising and becoming self-sufficient. “I think that old adage about teaching a man to fish as opposed to giving a man a fish can be applicable to many [aspects of life], including how to run a philanthropic organization proficiently.”

Hand’s interests and Mount Vernon’s goals aligned on a Revolutionary War encampment that he and Char would go on to help fund. “I want to fill gaps. I tried to do that in business, to make products that others didn’t, and when we got into philanthropy I wanted to do the same thing,” he says.

To his delight, Mount Vernon brought his vision to life: The encampment debuted on the estate grounds this spring (see page 4). “We forget that education can be entertaining,” he says. “If we can get [visitors] on this site, and they see musket demonstrations and people in period garb talking about what it was like back then, I think it’s going to be impactful.”

Hand strongly believes that learning about the past is crucial to the future of the country. “It does matter that we know where we came from,” he says. “So that when we have important decisions to make, we can say this is what [the founders] had in mind; this is what we should do based on that.” H

In the summer of 1775, the army general felt woefully unready to take on the enemy

By Rick Atkinson

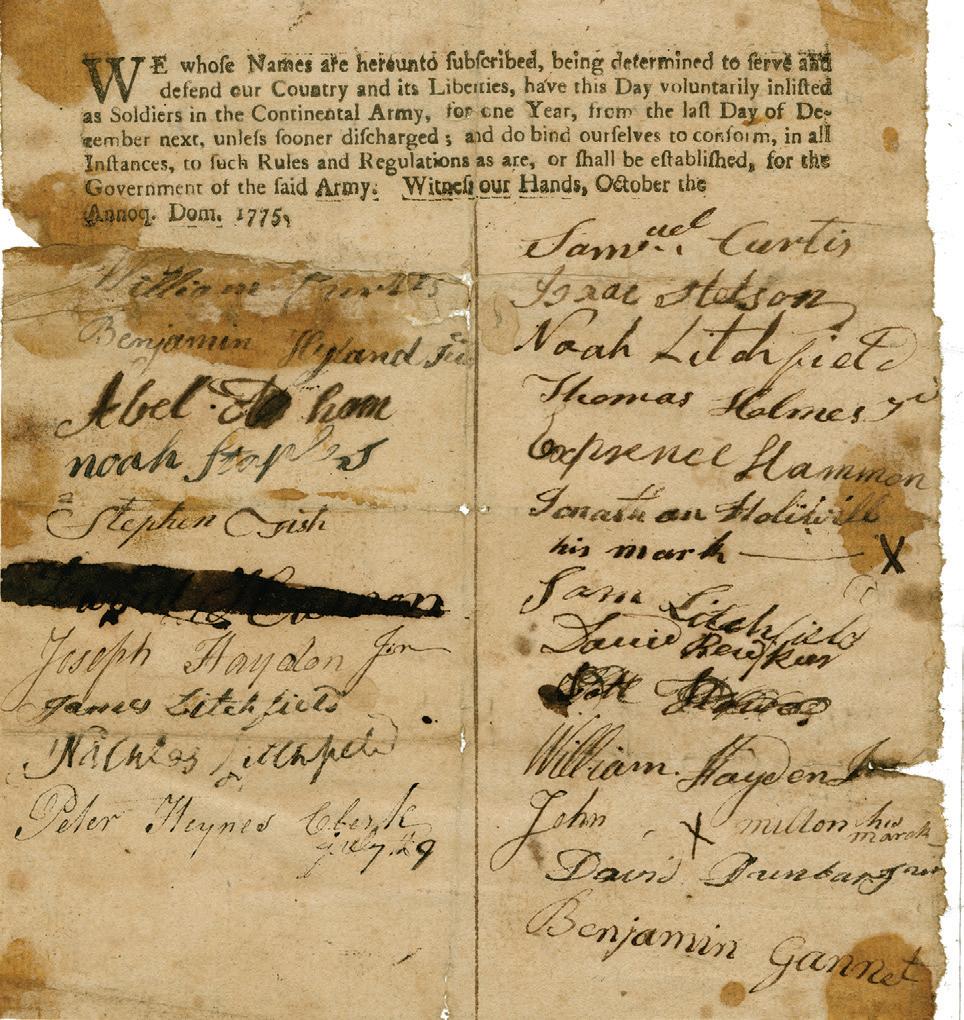

General Washington,

faced a mountain of obstacles, not least of which was organizing an army. Opposite: Records from a New Hampshire brigade, 1778–1779.

Few would guess that the imposing, confident figure who rode into Cambridge, Massachusetts, in July 1775 to command the newly formed Continental Army concealed his own anxieties and insecurities. In tears he had told a fellow Virginian, Patrick Henry, “From the day I enter upon the command of the American armies, I date my fall, and the ruin of my reputation.” To his brother he confided, “I am embarked on a wide ocean, boundless in its prospect & from whence, perhaps, no safe harbor is to be found.”

General George Washington would soon move his headquarters into the vacant Vassall House, a gray, threestory Georgian mansion whose orchards, outbuildings, and sweeping vista of the Charles River evoked his beloved Mount Vernon. He chose a high-ceilinged, ground-floor room with Delft tile for his bedchamber, parked his new phaeton and saddle horses in the stable, and then set out to fulfill his marching orders from Congress.

The new commander in chief needed little time to grasp the lay of the land. The former surveyor’s spyglass showed two armies barely a mile apart, squinting “at one another like wildcats across a gutter,” in one officer’s description. The Charlestown peninsula, across the Charles from Boston, had been seized by the British in mid-June at the cost of a thousand redcoat casualties in the Battle of Bunker Hill. Now the enemy was “strongly entrenched on Bunker’s Hill,” Washington wrote on July 10 to John Hancock, the president of Congress. Charlestown Neck had been ditched, palisaded, and fraised to thwart an American attack. White British tents

covered the peninsula, and three floating batteries on the Mystic River commanded the isthmus. In Roxbury, felled trees, earthen parapets, and gun batteries blocked the southern approach to Boston.

Washington’s own “troops of the United Provinces of North America,” as he called them, occupied more than 230 buildings from Cambridge to Brookline. But they hardly seemed a match for the professional British Army and the Royal Navy fleet that controlled the New England coast. “Between you and me,” Washington wrote a Virginia friend, “I think we are in an exceeding dangerous situation.”

Commands cascaded from his headquarters, the first of 12,000 orders and letters to be issued in his name over the next eight years. Because so few Yankees wore uniforms, rank would be color-coded: Senior field-grade officers were to wear red or pink cockades in their hats; captains would wear yellow or buff; subalterns, green. A strip of red cloth pinned on the shoulder signified a sergeant; green indicated a corporal. Generals wore chest sashes: purple for major generals, pink for brigadiers, light blue for the commander in chief. Washington agreed to be called “His Excellency,” despite grumbling in the ranks about the imperial implication. “New lords, new laws,” the troops told one another.

Washington quickly organized his army into three “grand divisions,” each commanded by a major general and composed of two brigades, typically with six regiments apiece. Rather than the 25,000 troops he had expected, Washington found that he had fewer than 14,000 men present and fit for duty around Boston.

For every moment Washington drew his sword or spurred his horse to the sound of the guns, there would be a thousand administrative moments: dictating orders, scribbling letters, convening meetings, hectoring, praising, adjudicating. He soon recognized that he needed to oversee the smallest aspects of the army’s operation, from camp kettles to bread quality to the $333 paid an unidentified spy—“to go into the town of Boston … for the purpose of conveying intelligence of the enemy’s movements and designs.”

He quickly saw that unlike the fantasy army that

existed in congressional imaginations, this army was woefully unskilled; bereft of artillery and engineering expertise, it was led by a very thin officer corps. “We found everything exactly the reverse of what had been represented,” complained Major General Charles Lee, who would serve as Washington’s senior deputy. “Not a single man of ’em is [capable] of constructing an oven.”

Washington also recognized that his own five years as a callow militia officer during the French and Indian War had left him, as he wrote, with “the want of experience to move upon a large scale”; like every other American commander, he knew little of cavalry, artillery, the mass movement of armies, or how to command a continental force. Still, service under British officers in that earlier struggle had deeply imprinted him with European orthodoxy, including strong preferences for offensive warfare, firepower, logistical competence, and rigid discipline.

Even as he immersed himself in tactical minutiae, Washington recognized that a commander in chief must be a capable strategist; that brass spyglass had to focus on the horizon as much as on the local battlefield. And Washington was—instinctively, brilliantly—a political general: In the month following his departure from Philadelphia to take command in Cambridge, he wrote seven letters to Congress, acknowledging its superior authority while maneuvering to get what he needed. He used all the tools of a deft politico: flattery, blandishment, reason, contrition. More letters went to colonial governors and other influential officials. Congress had adopted the New England militia as a national force, to be augmented with regiments from other colonies, and he was aware that placing a southerner in command of this predominantly northern army was a fragile experiment in continental unity.

The coming weeks and months required intimacy with his army, building the mystical bond between leader and led. Washington would personify the army he commanded, no small irony given the despair and occasional contempt it caused him. That army would become both the fulcrum on which the fate of the nation balanced and the unifying element in the American body politic, a tie that bound together disparate interests of a republic struggling to be born. “Confusion and discord reigned in every department,” Washington wrote in late July. “However we mend every

day, and I flatter myself that in a little time we shall work up these raw materials into good stuff.”

“Discipline,” Washington had written in 1757, “is the soul of an army.” Certainly this army was still looking for its soul. American troops, one visitor claimed, were “as dirty a set of mortals as ever disgraced the name of a soldier.” No two companies drilled alike, and together on parade they were described as the finest body of men ever seen out of step. Their infractions were legion: singing on guard duty, voiding “excrement about the fields perniciously,” promiscuous shooting for the sake of noise, a tendency by privates to debate their officers, “unnecessary drum beating at night,” and insolent “murmuring.”

For days on end, Washington rode from Chelsea to Roxbury and back—inspecting, correcting, fuming— then returned to Vassall House to issue another raft of exhortatory commands. In the three months following his arrival in Cambridge, the commander in chief on five occasions, in general orders, condemned excessive drinking. Four times he demanded better hygiene. Thirteen times he pleaded for accurate returns from subordinate commanders to gauge the size and health of the army.

Washington’s conceptions of military justice had been shaped by his years under stern British command during

the French and Indian War. In the spring of 1757 alone, he had approved floggings averaging 600 lashes each— enough to cripple a man, or even kill him—and presided over courts-martial that imposed more than a dozen death sentences. Congress now stayed his hand by restricting floggings to 39 stripes (soon to be increased to a hundred, at his insistence).

“My greatest concern is to establish order, regularity & discipline,” Washington wrote Hancock. “My difficulties thicken every day.” In truth, an immensely wealthy man to the manner born, with scores of slaves to tend his business in his absence from home, could hardly comprehend the sacrifice made by most of his men in leaving their families, shops, and farms in high season. For that vital link between commander and commanded to be welded, Washington would have to know in his bones—and the men would have to know that he knew—what was risked and what was lost in serving at his side.

Aggressive and even reckless, Washington longed for a decisive, bloody battle that would cause Britain to lose heart and sue for a political settlement. That appeared unlikely in Boston, where the British were

so entrenched “it is almost impossible for us to get to them,” he wrote. Instead, the summer and fall would be limited to skirmishes, raids, and sniping. “Both armies kept squibbing at each other,” wrote the loyalist judge Peter Oliver. Yet squibbing would not winkle the British from Boston, nor provoke them to give battle. Moreover, Washington could hardly wage a protracted campaign, given that his army was short of virtually everything an army needed, from straw to spoons.

American troops—badly housed, badly clothed, and badly equipped—were at war with the world’s greatest commercial and military power, long experienced in expeditionary administration. As an ostensible national government, Congress had begun to improvise the means to fight that war, from printing money and raising regiments to collecting supplies. But the effort thus far seemed disjointed and often half-baked. Although Congress had appointed quartermaster and commissary chiefs, the jobs were neither defined nor supported, and other critical supply posts—notably for ordnance and clothing—would not be created for another 18 months.

Simply feeding the regiments around Boston had

become perilous. Commissary General Joseph Trumbull frantically tried to organize butchers, bakers, storekeepers, and purchasing agents. Coopers were needed to make barrels for preserved meat, and salt—increasingly scarce— was wanted to cure it. Forage, cash, and firewood also grew scarce; an inquiry found that much of the “beef” examined was actually horse. By late September, Trumbull worried that by spring the army would face starvation and thus have to disband. “A commissary with twenty thousand gaping mouths open full upon him, and nothing to stop them with,” he wrote, “must depend on being devoured himself.”

But no shortage was as perilous as that discovered in early August. Gunpowder was the unum necessarium, as John Adams wrote, the one essential. A survey taken soon after Washington’s arrival reported 303 barrels in his magazines, or 15 tons—enough to stave off a British attack, but too little for cannonading. “We are so exceedingly destitute,” Adams told Hancock, “that our artillery will be of little use.”

Precisely how destitute became clear on August 3. The earlier gunpowder estimate had erroneously included

stocks used up at Bunker Hill and other skirmishes. The actual supply on hand totaled 9,937 pounds, or enough for about nine rounds per soldier. “The general was so struck that he did not utter a word for half an hour,” Brigadier General John Sullivan told the New Hampshire Committee of Safety. When he finally regained his tongue, Washington wrote his lieutenants that “our melancholy situation” must “be kept a profound secret.” This dire news, he added, was “inconceivable.”

More orders fluttered from the headquarters, along with desperate pleas. “Our situation in the article of powder is much more alarming than I had the most distant idea of,” Washington wrote Congress. “The existence of the army, & the salvation of the country, depends upon something being done for our relief, both speedy and effectual.” Every soldier’s cartridge box was to be inspected each evening; some regiments levied one-shilling fines for each missing round. Civilians were asked “not to fire a gun at beast, bird, or mark without real necessity.” Even the camp reveille gun should be silenced.

The protracted struggle to come It would not get easier. No one could foresee that the American War of Independence would last 3,059 days. Or that the struggle would be marked by more than 1,300 actions, some large and bloody, others small and bloody. Or that there would be 241 naval engagements in a theater initially bounded by the Atlantic seaboard, the St. Lawrence and Mississippi Rivers, and the Gulf of

Mexico, before expanding to other lands and other waters.

Roughly a quarter million Americans would serve the cause in some military capacity. At least one in 10 of them would die—25,674 deaths by one tally, as many as 35,800 by another, the largest proportion of the American population to perish in any conflict other than the Civil War. The odds were stacked against the Americans: No colonial rebellion had ever succeeded in casting off imperial shackles. But, as Voltaire had observed, history is filled with the sound of silken slippers going downstairs and wooden shoes coming up.

Those 3,059 hard days would lead to the creation of the American republic. Surely among mankind’s most remarkable achievements, this majestic construct also inspired a creation myth that sometimes resembled a garish cartoon, a melodramatic tale of doughty yeomen resisting moronic, brutal lobsterbacks. The civil war that unspooled over those eight years would be both grander and more nuanced, a tale of heroes and knaves, of sacrifice and blunder, of redemption and profound suffering. Washington more than any man would lead his country to victory against all odds. Beyond the battlefield stood a shining city on a hill.

Historian and author Rick Atkinson is a three-time Pulitzer Prize winner in history and journalism. This article is adapted from his book, The British Are Coming: The War for America, Lexington to Princeton, 1775–1777, which won the George Washington Prize in 2020.

The second volume of the American Revolution trilogy to be published in April

Rick Atkinson’s The Fate of the Day covers the middle years of the Revolution. In Pennsylvania, George Washington pleads with Congress to deliver the money, men, and materiel he needs to continue the fight. Stationed in Paris, Benjamin Franklin woos the French. And in New York, General William Howe, the commander of the greatest army the British have ever sent overseas, plans a new campaign. The months and years that follow bring epic battles at Brandywine, Saratoga, Monmouth, and Charleston, a winter of misery at Valley Forge, and yet more appeals for sacrifice by every American committed to the struggle for freedom. Atkinson provides not only a narrative of dramatic history, but also a fresh perspective on the demands a democracy makes on its citizens. The book will be available in The Shops or online at mountvernon.org/shops.

Spring and summer of 1775: A fiery speech, a shot heard ’round the world, a daring ride in the dark, a new commander, a bloody battle

March 20–27

Washington attends the Second Virginia Convention in Richmond, where Patrick Henry delivers his famous “Give me liberty, or give me death!” speech.

April 14

British General Thomas Gage receives orders from London to suppress the colonial rebellion by force. He orders British regulars in Boston to seize Patriot supplies in Concord, Massachusetts.

April 18

Paul Revere and William Dawes ride from Boston to warn colonial militias of the British advance on Lexington and Concord.

April 19

The Battles of Lexington and Concord occur. The first shots of the American Revolution are fired as British forces clash with colonial militias, sparking open conflict.

May 10

Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold capture Fort Ticonderoga in New York, gaining crucial artillery for the colonial cause. The Second Continental Congress convenes in Philadelphia, debating the next steps for colonial resistance. Washington attends as a delegate from Virginia.

May 25

British reinforcements, including Generals William Howe, Henry Clinton, and John Burgoyne, arrive in Boston to strengthen the British presence.

June 14

The Second Continental Congress creates the Continental Army, adopting the militias besieging Boston as its core force.

June 15

Washington is appointed commander in chief of the Continental Army, a

critical moment in the Revolution.

June 16

Washington formally accepts his commission as commander in chief. He tells the Congress that he does not feel equal to the task but would serve out of a sense of duty to his country.

June 17

The Battle of Bunker Hill takes place near Boston. Though the British win the battle, they suffer significant casualties, bolstering colonial morale.

July 2

Washington arrives in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and officially takes command of the Continental Army besieging Boston. His first task is to organize and discipline the disparate colonial militias into a unified fighting force.

July 5

The Continental Congress adopts the Olive Branch Petition, a final attempt by the Congress to avoid war with Great Britain.

In the first days of war, the new commander of the Continental Army penned two love letters to his wife

By Samantha Snyder

As violence continued to escalate in Massachusetts after the Battles of Lexington and Concord that April, the Continental Congress decided to establish a formal standing army. Raising an army was one challenge; finding a capable leader was another. Thomas Johnson, a delegate from Maryland, formally nominated George Washington, who was soon recognized by the “unanimous voice of the colonies” as the only individual who could lead successfully.

On June 16, 1775, the delegates to the Second Continental Congress, meeting in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, named George Washington commander of the Continental Army. The solemnity of the moment weighed heavily on Washington, but through all the felicitations and fanfare, the newly tapped general could think of little else but his beloved wife, Martha. The couple had been married for 16 years, and Martha had seen George through numerous trials before this. They’d been separated before, and for months at a time, but always

with an end date in sight. This was different. In taking the position of commander, he was now under a threat of violence that could lead to a permanent separation. A violent end was possible, even likely.

On June 18, he wrote the first of two surviving letters to Martha, affectionately calling her his “dear Patcy.” In this letter (now held by Tudor Place in Washington, D.C.) he alerts her to the news of his appointment. This news was not entirely surprising, as he’d been preparing for weeks, if not months, for the responsibility of leading American troops into battle. Nonetheless, he expresses great reluctance at leaving her vulnerable and without his companionship or any family at Mount Vernon, telling Martha he would rather “enjoy real happiness in one month with her at home,” than he had at the “distant prospect of finding abroad, if his stay were to be seven times seven years.” Nevertheless, Washington believes the position to be “a kind of destiny.” He tells her it is not his own safety he worries about, but hers.

I shall rely therefore, confidently, on that Providence which has heretofore preserved, & been bountiful to me,

not doubting but that I shall return safe to you in the fall—I shall feel no pain from the Toil, or the danger of the Campaign—My unhappiness will flow, from the uneasiness I know you will feel at being left alone—I therefore beg of you to summon your whole fortitude & Resolution, and pass your time as agreeably as possible—nothing will give me so much sincere satisfaction as to hear this, and to hear it from your own Pen.

He wrote several other letters to family members the following day in a similar tenor, but none were quite

as personal. The subsequent five days were filled with dinners, meetings, and preparations for his journey east.

On Tuesday, June 20, he reviewed three Philadelphia battalions in the State House Yard. One attendee wrote that it was a “spectacle of grand proportions,” seeing the men dressed in their finest uniforms, making “a most martial appearance.” One of these battalions, the Troop of the Light Horse, would usher George Washington out of the city to New Jersey, along with congressional delegates from Massachusetts and other militia members.

On June 23, the morning of his departure, his trunks were packed and his entourage awaited. Compared to the week prior, when he penned a steady stream of letters, he simply wrote one: a short, sweet note to his wife.

My dearest,

As I am within a few Minutes of leaving this City, I could not think of departing from it without dropping you a line; especially as I do not know whether it may be in my power to write again till I get to the Camp at Boston—I go fully trusting in that Providence, which has been more bountiful to me than I deserve, & in full confidence of a happy meeting with you sometime in the Fall—I have not time to add more, as I am surrounded with Company to take leave of me—I retain an unalterable affection for you, which neither time or distance can change, my best love to Jack & Nelly, & regard for the rest of the Family concludes me with the utmost truth & sincerity Yr entire, G.o Washington

This letter, held in the collections of the George Washington Presidential Library at Mount Vernon, appears to be the only one he wrote that day. The next surviving letter is dated June 25, in which he informs Congress of his arrival in New York. It would take him another week to reach Cambridge, arriving on July 2.

“I could not think of departing from [the city] without dropping you a line.... I retain an unalterable affection for you, which neither time or distance can change.... Your entire, G.o Washington”

Just under six months later, Martha joined him in Cambridge. She would go on to visit her husband numerous times over the next eight years, providing him with a sense of peace and comfort that was evident to all. As Martha’s son John Parke Custis wrote, his mother and stepfather’s “happiness when together will be much greater than when they are apart.”

Samantha Snyder is the research librarian at the George Washington Presidential Library at Mount Vernon.

The secret history of the letters George Washington wrote

In 1802, just before Martha Washington’s death, according to a letter from her granddaughter Eleanor to Washington biographer Jared Sparks, the nation’s first first lady ordered the letters between her and husband to be destroyed during her “last illness,” thereby safeguarding the privacy of nearly 41 years of marriage. Luckily for posterity, two letters managed to escape the flames, thanks to simple oversight. Sometime before 1828, Martha Washington’s granddaughter, Martha Custis Peter, stumbled upon two letters concealed behind a drawer of her grandmother’s writing desk (see page 23). She had inherited the desk and moved it to Tudor Place, her home in Washington, D.C. After George Washington purchased the piece in 1789, Martha must have used it as storage space for many years of correspondence, including those dating back to

the Revolutionary War. This historic desk is now once again at Mount Vernon.

The consecutive dates of the letters suggest that Martha kept them bundled together chronologically, keeping with her husband’s practice. It remains a mystery how these two letters became separated from the rest of the bundle. It could be that someone, perhaps even Martha herself, intentionally slipped them back behind the drawer. More likely, the letters may have been at the bottom of a stack, and slid away from the rest when they were taken from the drawer to be burned. Apart from one other letter from Martha to George dating to March 30, 1767, the rest of the correspondence between the couple has been lost, giving the Washingtons the privacy they rarely had while they lived. —S.S.

Image conscious:

confidence and respect,

Both his choice of uniform and his equipment branded General Washington as an honorable and frugal leader

By Amanda Isaac

For washington, outfitting for war was not just a matter of necessity or convenience; it was an argument asserting that Americans had the virtue and civility to govern themselves. At the outset of the conflict, the then-called United Colonies had a profound image problem. To the mother country, Americans were spoiled children, provincial and naïve, and when it came to fighting, “poltroons & cowards.”

Washington’s self-presentation through his uniform and material goods defined him as a man of honor, a leader who led by merit rather than ostentatious displays of wealth and power, served without pay, and was frugal with public funds. To see Washington at his campaign headquarters surrounded by his troops was to see one of “the most admirable spectacles in the world—the valiant and generous leader of a brave nation fighting for liberty,” gushed French diplomat the Marquis de Barbé-Marbois.

Washington’s ability to brand himself and the American cause would be among the many gifts he would later bring to the presidency, when he once again took the helm, and found the nation and the world eager to understand what a citizen-leader looked like.

Arguably the most important parts of Washington’s baggage were the trunks that secured his official correspondence—the papers that would defend his character and actions before Congress and his contemporaries. This half-tanned leather trunk was the first one used for this purpose. Purchased on April 4, 1776, as Washington and the Continental Army departed Boston on the first major campaign of the war, it was not exactly ideal in form for carrying papers, but it was the best that could be found at the moment. Washington’s oval copper nameplate was nailed over the previous

owner’s initials. In 1781, after five years of service, the trunk and its papers were delivered to Lieutenant Colonel Richard Varick, the recording secretary appointed by Congress to organize and classify all official wartime correspondence.

Symbol of rank, ultimately abandoned

Elected commander of the Fairfax Independent Company in the fall of 1774, Washington initially outfitted himself

Washington’s agent secured the “only one” to be found in Philadelphia, a secondhand sash purchased at the discounted price of £5.

with the typical symbols of rank worn by English officers, including this red silk sash. These specialty items were in short supply at the time, and Washington’s agent secured the “only one” to be found in Philadelphia, a secondhand sash purchased at the discounted price of £5. Washington may have worn it while attending the Second Continental Congress in 1775, but by the time he took command of the Continental Army in July 1775, he had dropped it. The decision was one of many refinements he would make to his and his officers’ uniforms over the course of the war.

The better to see British and American troop movements with

Handheld telescopes were crucial to George Washington’s ability to monitor troop movements. He acquired several during the war through purchase and as gifts and on one occasion, he sent one to an officer in preparation for covert communication via signal fire. This handsome, three-draw, mahogany and brass spyglass by London optical instrument maker Henry Pyefinch was named in Washington’s will as “part of my equipage during the late War.” It featured achromatic lenses: compound lenses made of two different kinds of glass that corrected chromatic distortion of color wavelengths, resulting in a crisper and cleaner image. Pushing in or pulling out the draw barrels focused the instrument.

Symbol of rank, honor, and prowess

Washington wore this finely decorated 1767 silver-hilted smallsword on many dress occasions during the war. Charles Willson Peale’s portraits of Washington often display this sword, a detail that heightens their realism. Originally acquired in the 1760s, the sword features a German blade and a London-made hilt with delicate piercing on the guard and pommel button, faceted bright-

cut decoration on the knuckle bow, and elegant tracery engraved on the blade. Washington is believed to have worn this sword for his greatest, final act of the war, when he resigned his commission before Congress in December 1783 and returned to civilian life.

Ceremonial, as well as practical

Over the course of the war, Washington acquired several pairs of pistols through purchase, capture, and gift. The smoothbore flintlock pistols on page 26 date to circa 1780 and bear the mark of lockmaker William Woolley of Bilston, England. They feature brass barrels, lockplates, sideplates, and butt caps, with the additional flourish of silver wire inlay on the tang. In the 19th century, a later generation of owners cut down the barrels and a misfiring resulted in the partial destruction of one.

A foldable cot frame that came up short

Washington acquired this field bedstead in Massachusetts on October 3, 1775, just a few months after taking command, and used it throughout the war in his sleeping tent. The plain bedstead exhibits the ingenious design that characterized British campaign furniture. The posts and legs fold up, and the rails are hinged to fold like an

accordion, collapsing into a form that could be bundled into a leather portmanteau and easily transported. It may have been a little short for the General’s estimated 6'2'' frame (it was just six feet long by three feet wide), but when fitted out with bedding, canopy, and curtains, it offered hope for a relatively comfortable night’s sleep in the field.

This delicate blue silk ribbon is a remnant of Washington’s wartime appearance, having been worn by him between 1775 and 1780. Upon taking command of the loosely

constituted Continental Army, Washington needed a simple way to make sure independent-minded men from across the colonies could tell who was in charge. In his General Orders of July 14, 1775, Washington designated that a blue ribbon be worn by the commander in chief, purple by major generals, pink by brigadier generals, and green by aides-de-camp. It may have seemed like a good idea at the time, but it sent mixed messages, confounding soldiers and outside observers alike, who thought the system contradicted the goals of the cause. The ribbons resembled those worn by the nobility and members of orders of chivalry in Europe. In England, blue silk ribbons were synonymous with loyalty to the crown, and were

By Lindsay Chervinsky

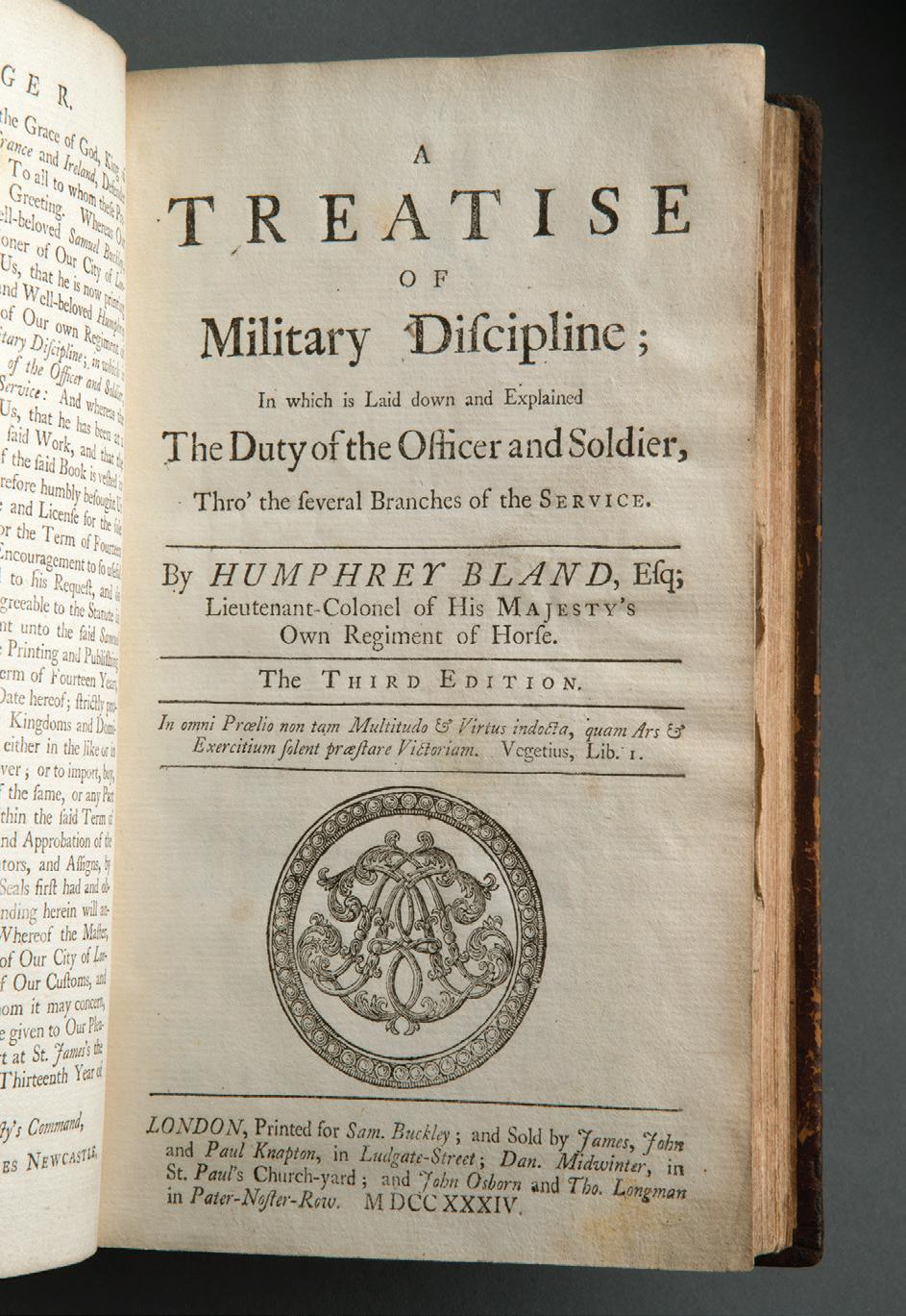

n The Prussian Evolutions in Actual Engagements Thomas Hanson’s manual, one of the earliest for the instruction of American officers, reflects American efforts to adopt European military practices, particularly those of the esteemed Prussian Army. A month before his appointment as commander in chief of the Continental Army, Washington ordered eight copies of the book, which details 1760s-era platoon organization and maneuvers in firing, standing, advancing, and retreating.

n A Military Treatise on the Appointments of the Army Washington received this book, authored by Thomas Webb, from Philadelphia merchant William Milnor in 1774. Originally aimed at enhancing British military operations in North America during the French and Indian War, the book, according to its own subtitle, contained “Many Useful Hints, Not Touched Upon Before by Any Author: And Proposing Some New Regulations in the Army, Which Will Be Particularly Useful in Carrying on the War in North-America.” It became a valuable resource for Washington as he organized the Continental Army. This treatise was among the volumes in Washington’s library at the time of his death.

n A Treatise of Military Discipline First published in 1727, Humphrey Bland’s work (see page 16) is regarded as the most widely used military drill book of the 18th century. Washington purchased the book, which lays out the duties of the officer and the soldier, in 1756, using its principles to train the Virginia militia during the French and Indian War and later the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War. While recommending books to a colonel in 1775, Washington wrote that “Bland (the newest edition) stands foremost.”

worn by the elite Knights of the Order of the Garter. The Marquis de Barbé-Marbois saw Washington’s ribbon as an “unrepublican distinction.” When Washington dispensed with the ribbon system in 1780, Barbé-Marbois commended the change, noting that Washington’s uniform then appeared “exactly like that of his soldiers.” Washington gave the ribbon to painter Charles Willson Peale, who preserved it for posterity, even while his portraits of the General from 1780 onward presented his new, ribbon-less look.

Cooking and dining while on the go

Washington’s camp equipage included several canteens, or traveling chests and leather packs for transporting lightweight cooking equipment, food, and spirits when on the move. This example contains tinned sheet iron plates, camp kettles with detachable wooden handles, a folding gridiron, and cutlery. The dishes endured heavy use, and in 1779, Washington noted: “[M]y plates and dishes, once of Tinn, now little better than rusty iron, are rather too much worn for delicate stomachs in fixed and peacable quarters, tho they may yet serve in the busy and active movements of a Campaign.” Washington procured sets of ceramic dishes to use during winter quarters and when entertaining at headquarters.

Eager to get on campaign, Washington acquired his first set of headquarters tents made of strong linen in the spring of 1776. In a letter to Colonel Joseph Reed, he wrote, “I cannot take the field without equipage, and after I have once got into a tent, I shall not soon quit it.” Washington typically used his field headquarters for seven to eight months of the year—roughly from May to December. After two years of hard campaigning, he replaced the first set of tents with new ones in 1778. Thanks to the remarkable efforts of numerous individuals, most of this second wartime tent complex survives, including the sleeping and office tent, now held by the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia. The relative plainness and simplicity of the tent, in contrast to the elaborate setups of warring European monarchs, became emblematic of Washington’s virtue. His commitment to living in a tent, personally identifying with the hardships of his troops, demonstrated he was one of them and worthy of their respect.

Ruggedly elegant tumblers of good cheer

Dining with General Washington was a formal affair, equivalent to a state dinner when members of the government and foreign dignitaries were present. Silver camp cups brought an air of elegance to the otherwise modest table settings. Philadelphia silversmith Richard Humphreys made this camp cup (see page 27) engraved with Washington’s crest as part of a larger set. Among the guests who recalled drinking from them was one English visitor, who, arriving ill, noted: “The General … made me drink three or four of his silver camp cups of excellent Madeira at noon, and recommended to me to take a generous glass of claret after dinner, a prescription by no means repugnant to my feelings.” Washington’s cure worked like a miracle. The visitor claimed, “I continued my journey to Massachusetts, without ever experiencing the slightest return of my disorder.”

Amanda Isaac is the curator at Mount Vernon.

The remarkable story of how a long-hidden trove of Revolutionary War–era private papers reached the digital age

On december 14, 1782, from his headquarters in Newburgh, New Jersey, George Washington penned a poignant farewell to his cherished friend and brother-in-arms, Major General François-Jean de Beauvoir, Chevalier de Chastellux: “I felt too much to express

anything the day I parted with you,” Washington confessed, adding, “never in my life did I part with a man to whom my soul clave more sincerely than it did to you.”

The letter captures the depth of their relationship—a bond forged through shared military service, intellectual exchange, and mutual admiration. It is also a testament to the enduring Franco-American alliance, culminating in

the victory at Yorktown in 1781—a pivotal event that all but ended the Revolutionary War. Chastellux, who returned to France in 1783 after fighting for American independence in General Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau’s expeditionary army, held the letter in high regard and kept it among his private papers.

Marie-Brigitte de Chastellux safeguarded the papers following her husband’s death in 1788, ensuring their preservation during the turbulent years of the

French Revolution. These papers contained not only Washington’s letters but also a wealth of invaluable documents: correspondence with other American leaders such as Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and John Adams, as well as military reports and maps detailing Chastellux’s contributions to the American Revolution.

For more than two centuries, the collection remained largely forgotten in the family château in Burgundy, France, with the current generation of the Chastellux

family unaware of its scope or significance. However, in 2015, a Dutch historian studying in Paris came calling. Iris de Rode was interested in the origins of a very large centuries-old tulip poplar tree standing in the garden of her holiday home in Burgundy, which was reputedly planted by the Marquis de Lafayette. However, her research uncovered that it was not Lafayette but rather his uncle by marriage, François-Jean de Chastellux, who had brought the tree back to France from America. This led her to reach out to the resident of the Château de Chastellux, Philippe de Chastellux, which eventually resulted in the

For more than two centuries, the valuable trove of papers remained largely forgotten in the family chateau in Burgundy, France

unearthing of not only information about the tree but also 6,000 pages of unpublished source material detailing Chastellux’s life—as an officer of the French king and as a philosopher of the Enlightenment. Among these archival treasures, De Rode found Chastellux’s copy of the letter from George Washington quoted earlier in this article, along with 11 other manuscript letters addressed to Chastellux, and numerous other invaluable documents.

De Rode successfully negotiated access to the papers as part of her PhD research. In 2017, to support the upkeep of their 1,000-year-old château, the Chastellux family considered selling a few of the most significant materials, including Washington’s letters. Douglas Bradburn, Mount Vernon’s current president and CEO but at the time director of the George Washington Presidential Library at Mount Vernon, spotted the letters in a catalog at Christie’s auction house. He reached out to De Rode and subsequently offered the historian a fellowship at Mount Vernon. Since then, De Rode has returned multiple times for three additional fellowships, which have enabled her to complete her PhD dissertation on Chastellux’s intellectual and military achievements, and publish a biography of Chastellux in 2022. In 2023, it received the prestigious Prix Guizot from the Académie Française. De Rode’s breakthroughs in archival research did not end with Chastellux. While investigating Chastellux’s closest colleagues for her forthcoming English-language book, the researcher uncovered another unpublished archive in the French town of Le Creusot, Burgundy—the papers of Major General Antoine-Charles de Vioménil, another key officer under Rochambeau during the American Revolution. This little known collection was in an archive associated with the region’s heavy metal industry and is now preserved by the Académie François Bourdon. The Vioménil papers offer new insights into

his role, particularly regarding the internal organization of the French army that fought alongside Washington. They wonderfully complement the Chastellux papers, which primarily detail the cooperation between the allies. Together, these two previously inaccessible archives provide a unique perspective on the French role in the American Revolution through the eyes of its key players.

With the support of a generous grant from the Richard Lounsbery Foundation, the George Washington Presidential Library at Mount Vernon has partnered with the Chastellux family and the Académie François Bourdon to digitize the papers of both Chastellux and Vioménil in an initiative aptly named the French Digitization Project. The Vioménil database is available for researchers and the public at viomenil.mountvernon.org. The Chastellux digitized collection will only be available upon request to researchers onsite at Mount Vernon, as requested by the family.

Tara Galvez teaches English language arts and social science to eighth graders at Cupertino Middle School in Sunnyvale, California. Much of the history curriculum she covers focuses on the founding era, which led her to attend the George Washington Teacher Institute (GWTI) in the summer of 2024 for the “Washington at War” week.

What did you learn from the Teachers Institute that you’ve been able to integrate into your history curriculum? One speaker was Richard Josey, who brought up the concept of the duality: The idea that we are complex individuals, and one bad habit or truth does not invalidate the good. It’s not “but,” instead we use “and.” Washington was a liberator and an enslaver. The two can both be true in tandem. So I created this activity in which students are given a handout that resembles a pair of glasses. On one side of the glasses they write out all the good actions, and on the other they write all the questionable or negative actions while looking through the eyes of the historian.

Can you share specific history teaching methods that work with eighth graders?

I taught a condensed version of Modern Government last October and November so that students had a better understanding of the 2024 election. Students learned the ins and outs of propositions, including what a yes/no vote means, and then presented their research in teams. As a class, students voted for or against the propositions. The following day, we compared our results to the whole state and discussed why there may be discrepancies. Many students reported not only feeling more confident in understanding what they were hearing in the news, but also that they taught their adults about what some propositions meant or why they might choose to vote one way or another.

Are there moments in George Washington’s life that resonate with your students? When compared with the résumés of other founders, Washington is one of the few who did not have a formal education. He made a name for himself by joining the military and working his way up politically. His story resonates with students because if Washington can come from a tough beginning and work his way to president, why can’t they?

In the eight years you’ve been teaching social science, has the way you teach U.S. history changed? Early on in my career, I was more apt to follow the textbook, whereas now I find more supplemental materials that are more student-focused. It’s not just about reading a chapter about Andrew Jackson, it’s about letting students research and debate each other on how Jackson should be remembered. I want students to learn the facts to form their own opinion. I hope they leave my class knowing history is complex, and that they should always consider whose story is being told, and whose is being left out.

What do you hear from students when they learn about Washington’s role in the founding of the country?

Students arrive to class usually knowing he was the first president, but they don’t always realize all the precedents he set into motion that still impact our government today.

We outline many of Washington’s first-term decisions, such as forming the Cabinet, being called “Mr. President,” and proposing legislation to Congress. Students are often wowed by the idea of a person with so much power choosing to step down. H

Two signature events celebrate George Washington’s 293rd

On Sunday, February 16, Mount Vernon hosted its longest-running fundraiser, the Birthnight Supper and Ball. This year’s theme was inspired by the American trade ship that set sail for China on Washington’s 52nd birthday in 1784, returning with tea, fabrics, and spices, as well as approximately 64 tons of porcelain, including a remarkable 302-

piece porcelain set purchased by George Washington. In addition to porcelain, intricately painted fans were highly sought-after imports in the 18th century, and Martha Washington was known to have been particularly fond of them. Original examples of the Washingtons’ elegant blue-and-white porcelain and Martha’s fans can still be seen at Mount Vernon today.

Event co-chair Julie McLellan welcomed guests to an elegant evening featuring an Asian-inspired three-course dinner, a spirited auction where guests raised decorative fans to place their bids, live music, and dancing. Hosted by the Neighborhood Friends of Mount Vernon, the event raised more than $385,000 to support the restoration and preservation of the Mansion. Blending history with celebration, the night offered attendees a unique opportunity to connect with the Washingtons’ personal tastes and enduring legacy.

A week later, on February 22, Washington’s actual birthday, Mount Vernon’s most generous friends braved the winter chill to celebrate. Guests enjoyed a welcome reception followed by a conversation between philanthropist David Rubenstein; national security expert, consultant, and presidential granddaughter Susan Eisenhower; and Pulitzer Prize–winning author

Kai Bird. Eisenhower, Bird, and Mount Vernon’s president and CEO Douglas Bradburn were interviewed by Rubenstein for his latest book, The Highest Calling: Conversations on the American Presidency.

The Regent presented the esteemed Ann Pamela Cunningham Medal to extraordinary businesswoman and philanthropist Karen Buchwald Wright. Named for the founder of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, the award recognizes exceptional longterm contributions—in time, talent, resources, or a combination thereof—to Mount Vernon. This marks the fourth time the award has been presented, and Wright is the first female recipient. Her dedication and commitment to Mount Vernon include more than two decades of generous philanthropy as well as service on the former Advisory Committee and the current Washington Cabinet. H

Major donors supported Mount Vernon’s mission in 2024

Thanks to the generosity of major donors and those who participated in the America’s Home matching gift challenge, Strengthening Our Foundations: The Campaign for Mount Vernon has topped $210 million. More than 52,000 donors made gifts to Mount Vernon in 2024, including the following nine individuals, who made gifts of $1 million or more.

Washington Cabinet chair David Rubenstein announced his $12-million commitment to the Campaign for Mount Vernon at the group’s annual meeting. He joins Washington Cabinet members John and Adrienne Mars, Rob and Jean Estes, and Margot B. Perot, who also made major campaign commitments in 2024. The Campaign is funding important priorities, such as revitalizing the Mansion, creating a refreshed exhibit on George Washington’s biography, growing the Annual Fund, and increasing Mount Vernon’s endowment.

The Great Hall in the new George Washington exhibit will be named for Boeing in recognition of its multimillion-dollar commitment. The President’s House in the exhibit will recognize Roger Ferguson and Annette Nazareth. An anonymous donor funded the Washington in American Culture gallery. Additional naming opportunities are available. Connoisseur Society chair Lucy S. Rhame’s endowment gift will name a position in horticulture, and Tom Hand’s support through Americana Corner will fund Patriots Path Revolutionary War encampment. (See pages 4 and 10.)

Gifts at all levels are valued and appreciated as Mount Vernon preserves George Washington’s home and educates people around the world about his legacy. The Campaign for Mount Vernon will continue through 2026, when the Mansion will be in its best shape ever, a brand-new George Washington exhibit will be in the Education Center, world-class programming will continue at the George Washington Presidential Library, and educator outreach will be expanded. H

An elm tree in Cambridge, Massachusetts, witnessed Washington take command

In this stereograph (c. 1920s) stands an elm tree in Cambridge, Massachusetts, near the 1775 headquarters of the Continental Army. According to tradition, it was under this tree, dubbed the Washington Elm, that George Washington assumed command of the army on July 3, 1775. A granite marker, visible in the photo, was installed in 1864.

While it’s unclear whether Washington ever stood

under its branches, the elm was certainly a bystander to the action. Later romanticized 19th-century artwork and accounts depict a grander ceremony than likely occurred. With an advancing enemy, regiments spread thin, and no ammunition to spare, a parade and exposition of troops were simply out of the question; further, it was not in keeping with the temperament of their modest leader.

Two nearly identical photos, paired to produce a single 3D image when viewed through a stereoscope.

Unfortunately, on October 26, 1923, the historic tree fell while workmen were attempting to remove a dead branch. The city government had the tree sawed into numerous pieces and distributed them around the country. Mount Vernon has several in its collection. Grafts and descendants of the tree were planted nationwide, and several still survive, including across the street from the original, on Cambridge Common. H

P.O. Box 110, Mount Vernon, Virginia 22121

Tho’ I am truly sensible of the high Honour done me in this Appointment … I do not think myself equal to the Command I am honoured with.

George Washington

Address to the Continental Congress 16 June 1775