THE ROAD TO

REVOLUTION

Colonial Americans Envision Change

UPCOMING AT MOUNT VERNON

JOIN US FOR THESE POPULAR EVENTS

COLONIAL MARKET & FAIR

Shop 18th-century-inspired goods and meet the artisans at Mount Vernon’s Colonial Market & Fair—September 14–15. Admission is free for Mount Vernon members. mountvernon.org/colonialmarket

WHISKEY TASTINGS AT THE DISTILLERY

Sample George Washington’s whiskey and other distilled spirits made at Washington’s Distillery at this outdoor event— Saturdays in September. Tickets are discounted for Mount Vernon members. mountvernon.org/whiskeytasting

CONSULTING EDITOR: Norie Quintos

DESIGNER : Jerry Sealy

VICE PRESIDENT, MEDIA AND COMMUNICATIONS: Julie Almacy

CREATIVE DIRECTOR: James B. Hicks III

EDITORIAL COORDINATOR: Breck Pappas

VISUAL RESOURCES: Dawn Bonner

PROOFREADER: Lorna Notsch

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS: Adam Erby

Dawn Bonner

Margaret Loftus

Cheryl Marling

Kristen Otto Breck Pappas

Mount Vernon magazine is published three times a year by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, the nonprofit organization that owns and manages George Washington’s estate. We envision an America where all know and value the singular story of the father of our country. Ever mindful of our past, we seek innovative and compelling ways to tell the story of George Washington, so that his timeless and relevant life lessons are accessible to the world.

This publication is produced solely for nonprofit, educational purposes, and every reasonable effort is made to provide accurate and appropriate attribution for all elements, including historical images in the public domain. All written material, unless otherwise stated, is the copyright of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association. While vetted for accuracy, the feature articles included in this magazine reflect the research and interpretation of the contributing authors and historians.

George Washington’s Mount Vernon P.O. Box 110, Mount Vernon, Virginia 22121

All editorial, reprint, or circulation correspondence should be directed to magazine@mountvernon.org. mountvernon.org/magazine

ABOUT THE COVER

This 19th-century engraving depicts Virginia legislators George Washington, Patrick Henry, and Edmund Pendleton as they set out August 31, 1774, on horseback from Mount Vernon to attend the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia, held in September and October. Engraving by Henry Bryan Hall after Felix Octavius Darley, 1856, MVLA

16 | The Road to Revolution

What came before the “shot heard ’round the world”

20 | The Gathering Storm

Timeline: Lead-up to the Revolutionary War

22 | The Making of a Statesman

Washington’s leadership abilities did not only come from his vaunted military expertise but also his years as a legislator

By David L. Preston

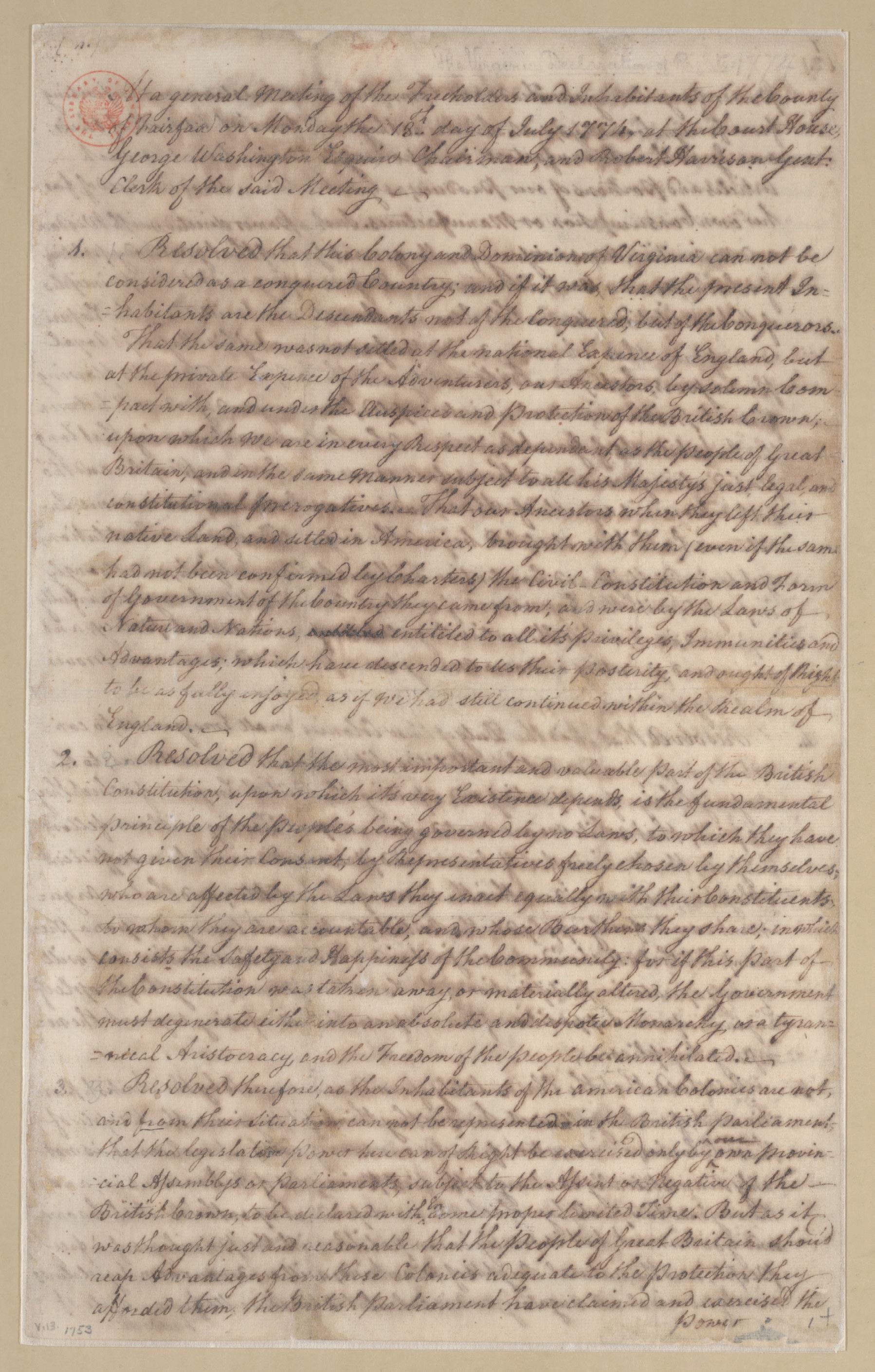

30 | An Argument for Autonomy

Written at Mount Vernon, the Fairfax Resolves were a draft of a future nation’s founding documents

By Samantha Snyder

On December 16, 1773, a group known as the Sons of Liberty pitched British tea into Boston Harbor. The act provoked punitive measures from the British and helped unite the American colonies.

4 | News

New Library director, a celebration in Alexandria, Mount Vernon treasures in Philadelphia, upcoming events, and more

12 | Object Spotlight

The earliest known visual depiction of the Marquis de Lafayette visiting the Tomb of George Washington

14 | Focus on Philanthropy

With deep roots in American history, the Boeing Company has a natural affinity for Mount Vernon

38 | Washington in the Classroom

A Wisconsin teacher shows fellow educators how to help students gain new perspectives on U.S. history

40 | Shows of Support

Special tours of the Mansion, donor receptions, and other events

44 | Featured Photos

Pohick Church, attended by George Washington, celebrates a milestone year

George Washington’s Mount Vernon estate is owned and maintained in trust for the people of the United States by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association of the Union, a private, nonprofit 501(c)(3) organization founded in 1853 by Ann Pamela Cunningham.

THE MOUNT VERNON LADIES’ ASSOCIATION

Margaret Hartman Nichols, Regent

Andrea Notman Sahin, Secretary

Anne Neal Petri, Treasurer

VICE REGENTS

Cameron Kock Mayer, Louisiana

Maribeth Armstrong Borthwick, California

Ann Haunschild Bookout, Texas

Virginia Dawson Lane, South Carolina

Laura Peebles Rutherford, Alabama

Susan Marshall Townsend, Delaware

Anne Neal Petri, Wisconsin

Liz Rollins Mauran, Rhode Island

Ann Cady Scott, Missouri

Sarah Miller Coulson, Pennsylvania

Andrea Notman Sahin, Massachusetts

Catherine Hamilton Mayton, Arkansas

Helen Herboth Laughery, Wyoming

Catherine Marlette Waddell, Illinois

Lucia Bosqui Henderson, Virginia

Mary Lang Bishop, Oregon

Elizabeth Medlin Hale, Georgia

Ann Sherrill Pyne, New York

Karen McCabe Kirby, New Jersey

Hilary Carter West, District of Columbia

Adrian MacLean Jay, Tennessee

Sarah Seaman Alijani, Colorado

Susan Brewster McCarthy, Minnesota

Carolyn Sherrill Fuller, North Carolina

SENIOR STAFF

Douglas Bradburn, PhD, President & CEO

Julie Almacy, Vice President, Media & Communications

Joe Bondi, Senior Vice President, Development

Lindsay M. Chervinsky, PhD, Executive Director, George

Washington Presidential Library

Joan Flintoft, Vice President, Hospitality

Phil Manno, Chief Financial Officer

Susan P. Schoelwer, PhD, Executive Director, Historic

Preservation & Collections & Robert H. Smith Senior Curator

Joseph Sliger, Vice President, Operations & Maintenance

K. Allison Wickens, Vice President, Education

On the eve of setting out to Philadelphia for the First Continental Congress in August 1774, George Washington wrote that the Parliament of Great Britain seemed intent on “trampling upon the Valuable Rights of Americans” and that nothing less than “Unanimity in the Colonies and firmness” could prevent the gradual loss of political freedom for the colonists.

We can imagine the scene of parting from Mount Vernon, with his enslaved manservant William Lee and fellow Virginia burgesses Patrick Henry and Edmund Pendleton. One likely apocryphal story has Martha Washington encouraging the men to “stand firm.” As the story is told, Pendleton remembered that, when they set off together, Martha “stood in the door and cheered us with the good words, ‘God be with you gentlemen.’”

Two hundred fifty years have now passed since George Washington left Mount Vernon for the First Continental Congress. In this issue, we set out to share some wisdom harvested from our collective past. We begin by taking a close look at 1774, the last full year before the start of the war. As Mary Beth Norton points out in her book 1774: The Long Year of Revolution (winner of the 2021 George Washington Prize), the year did not begin on a particularly rebellious note; many colonists, including Washington, looked unfavorably upon the destructive nature of the Boston Tea Party in December 1773. Understanding the events of the following months, which resulted in the First Continental Congress in September, is therefore critical to our understanding of the Revolution.

We then turn our attention to the evolution of a leader. Much has been written about Washington’s military qualifications to lead the Continental Army, but historian David Preston sheds light on a lesser-known facet of Washington’s leadership: his 16 years as a legislator before the Revolution. In Virginia’s House of Burgesses and the First and Second Continental Congresses, Washington matured into the republican statesman who, while at the helm of the Continental Army, would champion the people’s will as “the purest source and original fountain of all power.” His extensive legislative background, surpassing that of any potential rival for command, became invaluable in navigating the complexities of war and later in guiding the nation it birthed.

Samantha Snyder, the Washington Library’s research librarian, highlights Washington’s collaboration with

neighbor George Mason in crafting the Fairfax Resolves. This crucial document, drafted 250 years ago right here at Mount Vernon, was a full-throated declaration of American rights, signaling a key moment in the colonies’ united stand against British oppression and propelling Washington to the forefront of colonial resistance.

I’m also pleased to introduce Lindsay M. Chervinsky, PhD, as the executive director of the George Washington Presidential Library. Turn to page 6 to learn more about her. I look forward to seeing the insights and innovations she will bring as she leads the institution into its second decade.

As you navigate through the pages of this issue, I hope you are reminded of the resilience and unity, in the face of great uncertainty, that defined our nation’s journey to independence. May it serve as a testament to the enduring spirit of freedom and the legacy of those who paved the road to revolution—and a reminder that we are responsible for our shared future.

My best regards,

Douglas Bradburn President and CEO

Landmark Anniversary

The city of Alexandria, Virginia, celebrates the 1774 Fairfax Resolves

On July 18, the city of Alexandria, Virginia, hosted an evening commemorating the Fairfax Resolves, adopted 250 years ago to the day in that city. Attendees explored various history booths that provided insights into the era, met reenactors portraying George Washington and George Mason, and witnessed the dedication of a new historical marker near Market Square.

The Fairfax Resolves, written in July 1774, were a set of resolutions adopted by a Fairfax County committee at the time. They are widely regarded as one of the most radical statements of colonial rights and grievances against British policies. Crafted by George Mason with input from George Washington, the Resolves called for a Continental Congress and advocated for a unified response to British oppression, significantly influencing the colonies’ move toward independence. (See story, page 30.)

The event featured remarks by Carly Fiorina, national honorary chair of the Virginia American Revolution 250 (VA250) Commission. “The words of the Fairfax Resolves, the Declaration of Independence, the Bill of Rights, and the Constitution applied then only to white, male property

owners. Their writers were all enslavers. And yet these words ... brought radical ideas to life that have inspired every movement for human dignity, sovereignty, equality, and liberty everywhere, ever since.”

Additional events were held at George Mason’s Gunston Hall, historic Pohick Church, and Mount Vernon, which hosted the two-day conference “The Origins of the Revolution: 250th Anniversary of the Fairfax Resolves.”

The commemoration in Old Town, Alexandria, featured (clockwise from opposite) music by the U.S. Army Old Guard Fife and Drum Corps; remarks by Allison Wickens, Mount Vernon’s vice president of education; a keynote by Carly Fiorina, honorary chair of the VA250 Commission; period reenactors and the new historical marker highlighting the Fairfax Resolves; and a procession led by the Sons of the American Revolution Color Guard.

OCTOBER CELEBRATIONS

This fall, Mount Vernon will host two events in support of the landmark Mansion Revitalization Project. On October 14, a Masonic cornerstone ceremony will honor the ongoing effort to shore up the Mansion’s foundations. Hosted in conjunction with Alexandria–Washington Lodge, No. 22 (of which Washington was Master), the event includes a wreath-laying at the Tomb, a ceremony featuring a carved replica of the ornamental stone Washington set in his cellar wall, and a barbecue on the east lawn. Mount Vernon visitors can purchase tickets to join the barbecue. Visit mountvernon.org/corner stoneceremony.

On October 17, the Life Guard Society of Mount Vernon will host an evening gala on the east lawn to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the Marquis de Lafayette’s return to Mount Vernon. Lafayette’s visit in 1824 was a poignant tribute to his departed friend George Washington.

Visit mountvernon.org/ lgevent.

New Library Director

Lindsay M. Chervinsky takes the helm of the George Washington Presidential Library

This summer, the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association (MVLA) introduced Lindsay M. Chervinsky, PhD, as the new executive director of the George Washington Presidential Library. A renowned presidential scholar, Chervinsky joins Mount Vernon from the Center for Presidential History at Southern Methodist University and the White House Historical Association.

“The George Washington Presidential Library at Mount Vernon has established itself as the preeminent center for the study of George Washington, and we are pleased to have a historian of Dr. Chervinsky’s stature at the helm,” said Margaret Nichols, Regent of the MVLA. “Her knowledge and expertise of American history will ensure the continued advancement of the Association’s educational

mission to the highest standards.”

A past recipient of the Library’s James C. Rees Fellowship on the Leadership of George Washington, Chervinsky expressed her gratitude, stating, “I’m excited about leading the Washington Library into its second decade, and I look forward to sharing George Washington’s leadership, civic virtue, and commitment to democratic institutions with the American people at this pivotal moment in our nation’s history.”

Chervinsky received her bachelor’s in history and political science from George Washington University and completed her master’s and doctorate from the University of California, Davis. Her expertise will guide the Library through key anniversaries, including America’s 250th in 2026 and George Washington’s 300th birthday in 2032.

The Mansion’s ornamental stone.

Traveling Tent

New exhibit at Philadelphia’s Museum of the American Revolution showcases items from Mount Vernon

It’s no ordinary camping tent.

Witness to Revolution: The Unlikely Travels of Washington’s Tent, running through January 5, 2025, delves into the journey of George Washington’s Revolutionary headquarters tent through time. Kept by Martha Washington and later routinely displayed in the 1800s, including at Philadelphia’s Centennial Exposition of 1876, the tent has traveled widely.

In addition to the tent, the exhibit showcases other key camp items on

loan from Mount Vernon, including Washington’s foldable field bedstead, one of Martha Washington’s trunks, and silver spoons selected by General Washington for use in camp. Additionally, a significant piece of tent lining from Mount Vernon’s collection is reunited with eight other tent fragments, all preserved as souvenirs during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Finally, a stereograph from the Washington Library collection offers a glimpse of the tent’s display at the 1876 exposition.

The installation was made possible by Mount Vernon’s Collections Management team, which ensured the safe transport and installation of these priceless artifacts.

Spirit of Virginia Award

MVLA recognized for its legacy of stewardship

Virginia’s governor and first lady presented the Spirit of Virginia Award to the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association (MLVA) at a ceremony at Mount Vernon. Gov. Glenn Youngkin lauded the MVLA’s legacy: “Its commitment to preservation has provided an unmatched opportunity for Virginians to learn about George Washington’s legacy and the Commonwealth’s history.” Suzanne S. Youngkin emphasized the Association’s significance during Women’s History Month, noting, “Virginia’s history is America’s history, and we are reminded of the women whose vision led to today’s Mount Vernon and a greater understanding of our nation’s founding.”

MVLA Regent Margaret Nichols expressed gratitude for the award, underscoring the Association’s 166-year legacy of stewardship. The Spirit of Virginia Award recognizes exemplary contributions in education, culture, the arts, philanthropy, and business.

Virginia’s governor and first lady with MVLA Regent Margaret Nichols, Vice Regents Lucia Henderson and Anne Petri, and Douglas Bradburn, Mount Vernon president and CEO.

BEHIND THE SCENES

How to Pack Up a Room

A step-by-step guide to removing and storing the historical objects in the New Room

IN EARLY 2024, Mount Vernon began the Mansion Revitalization Project, which requires preservation carpenters to work extensively in the New Room as they repair elements of the Mansion’s framing. To best protect the objects in the New Room, many of which are Washington originals, Mount Vernon’s Fine and Decorative Arts Collections team first needed to remove them to a stable environment.

Art handlers on scaffolding removed objects out of easy reach, including this engraved portrait of France’s King Louis XVI.

1

Plan for storage: Every object removed from the New Room is stored on-site at Mount Vernon. Before beginning the de-installation process, the Collections management team carefully organized the climatecontrolled storage facilities.

2

Use proper packing materials: Standard paper and cardboard boxes made from wood pulp become acidic over time, which can deteriorate and degrade the items contained within. To best protect the objects, the team used acid-free boxes and packing materials—and a lot of bubble wrap.

3

Small items first: Working in their socks (to protect the floors), staff began early each morning, before the day’s first guests arrived at Mount Vernon. Beginning with the New Room’s smaller objects—such as the knife cases, porcelain figures, chairs, and small prints—the team

of seven handled and packed each object based on its specific needs.

4

Arrange for specialists and custom crates: To pack the room’s larger items, Mount Vernon enlisted the services of longtime partner ELY, Inc.—experts in crating and collections relocation. For the biggest items, including the room’s two sideboards and mirrors, ELY built foam molds and custom crates around the objects before removing them from the Mansion.

5

A special box for the room’s centerpiece: Lastly, a protective box was constructed to enclose the Vaughan mantelpiece—sent to George Washington as a gift from Samuel Vaughan, an English admirer and a recent emigré—thereby preserving the room’s magnificent centerpiece.

To learn more, visit mountvernon.org/de-install.

Moving day: (clockwise from top) A print is wrapped in plastic; a porcelain vase receives a custom foam mold; one of the room’s distinctive “mirrors and brackets” is carefully disassembled; a sideboard is crated in place.

Now part of the Mount Vernon collection, a drawing by Rembrandt Peale (left) and a document signed by King George III (below).

New Acquisitions

A trove of 18th-century documents and a remarkable Peale drawing

The Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association recently expanded its collection following two notable acquisitions.

Edward “Ted” Wendell and his wife Mary gifted Mount Vernon with their collection of more than 60 18th-century documents and books. For over 30 years, Ted’s particular interest in George Washington’s activities in the early American West prompted him to acquire more than 20 documents written, annotated, or signed by George Washington on that topic, including four Washington surveys, financial documents related to western land claims and rents, a British royal order signed by King George III (pictured above right), and several rare, early maps of western North America. The Wendells’ donation is the largest single contribution of George

Washington material since the 1940s and is a tribute to Washington’s 292nd birthday.

Separately, through the Jay F. and Patricia P. Hill Family Fund, Mount Vernon acquired a remarkable drawing executed by Rembrandt Peale in 1855 of the Houdon bust of Washington. Peale, who promoted himself as the last surviving artist to have painted Washington from life, esteemed the Houdon bust highly but saw shortcomings. In this drawing, Peale corrected perceived defects, using it later to create his famous Colossal Monochrome oil-on-canvas version of the bust. Peale believed this likeness was the example against which all other images of Washington should be judged. The acquisition strengthens Mount Vernon’s holdings of Peale’s works and offers insights into 19th-century perceptions of Washington.

Notebook

Cherries jubilee: Two rare, intact, liquid-filled bottles containing cherries—about 250 years old—were discovered by archaeologists working in the Mansion cellar in the fall of 2023. The Washington Post published the exclusive story and other outlets soon followed. Thirty-three more bottles, many containing additional berry varieties, have since been unearthed and researchers are studying them. Re-examined: The original ledger containing information about archaeological objects found at Mount Vernon between 1931 and the early 1970s had never been fully catalogued and described, until now, thanks to the work of curator of preservation collections Lily Carhart and archivist Rebecca Baird. New blog: The new Mansion Revitalization blog was launched in February at mountvernon. org/ManRevBlog. Articles give insight into the discoveries, excavation, and other behind-the-scenes work of this landmark project.

BY THE NUMBERS

9

New bilingual (English and Spanish) guided virtual tour videos for children to explore a variety of Mansion spaces.

1792

Year written on a newly acquired receipt for the purchase of a chair by Washington, possibly used in the president’s house in Philadelphia and later at Mount Vernon.

BUILDING ARTS RECOGNITION

The Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association was recognized with the American College of Building Arts’s (ACBA) 2024 Honors Award, bestowed in Charleston, South Carolina. The award was created to recognize outstanding achievements in the building arts and preservation fields. “The MVLA was the first national historic preservation organization and is the oldest women’s patriotic society in the United States,” noted the ACBA. “Its pioneering efforts in the field of preservation set an important example.”

83,975

Website views in the last four years of “How to Make Invisible Ink,” one of the most popular classroom activities to date.

The ACBA is the only college in the U.S. with a bachelor’s degree program that combines a liberal arts curriculum with professional training in the traditional building trades (timber framing, blacksmithing, plaster, etc.).

Under the leadership of Thomas Reinhart, director of preservation, Mount Vernon has welcomed ACBA students as summer interns, and graduates of the program are now valued staff members.

Astounding find: cherryfilled bottles.

Last Goodbye

The only known depiction of Lafayette’s visit to the Tomb of George Washington 200 years ago

Last year, Mount Vernon acquired a remarkable addition to its decorative arts collection, a gift from donor Marta Hallowell Black. This watercolor and silk embroidery on silk is the earliest known visual depiction of a momentous historical event: the Marquis de Lafayette’s stop at the Tomb of George and Martha Washington on October 17, 1824, during his final visit to the United States. He was a guest of Congress, and his 1824–25 visit coincided with the nation’s 50th birthday. Lafayette had personally bid farewell to the Washingtons at Mount Vernon 40 years earlier. Arriving now at the Tomb, as his official secretary Auguste Levasseur later wrote, “Lafayette descended alone into the vault, and a few minutes after re-appeared, with his eyes overflowing with tears.”

The work, by an unidentified artist, captures the emotionally charged moment before Lafayette entered the Tomb. It depicts the Old Tomb, the Washington family burial vault set in the wooded hillside overlooking the Potomac River. Heightening the illusion of the scene are embroidered portions of the foreground in smooth and crinkled chenille yarns that add depth and texture. Lafayette and the other gentleman at right also have tiny buttons applied to their coats.

Who’s Who?

n On either side of Lafayette (light brown coat) are members of the Custis family, headed by the two grandchildren of Martha Washington who grew up at Mount Vernon: George Washington Parke Custis (gesturing towards the tomb) and Eleanor (Nelly) Parke Custis Lewis (white dress). The other figures in this group may represent Lawrence Lewis, Nelly’s husband; Lorenzo Lewis, their son; and George Washington Lafayette, Lafayette’s son (far left).

n On the right, the artist depicted members of the Washington family, descendants of George Washington’s brother: John Augustine Washington II and his wife Jane Charlotte Blackburn Washington with one of their two young sons, and Bushrod Corbin Washington and his wife Anna Maria Blackburn Washington.

Stalwart Partner

The estate’s largest corporate donor, Boeing, sponsors several important annual events

The Boeing Company, with its deep roots in American history and a headquarters in Northern Virginia, has a natural affinity for its neighbor Mount Vernon. The company began in Seattle in 1916 with the sale of two single-engine seaplanes to the New Zealand Flying School. It took off a year later when the U.S. Navy ordered 50 Model Cs—another two-seater seaplane—to train pilots during World War I.

Since then, Boeing has become integral to the development of air travel, evolving into a multinational corporation that employs around 170,000 people in more than 65 countries. Today, the company is not only one of the top commercial airplane manufacturers in the world, it also continues to build military aircraft, satellites, and space rockets,

making it the third-largest federal government contractor.

In 2022, Boeing’s philanthropic interests found a home at Mount Vernon when it became the estate’s largest corporate donor with a one-million-dollar commitment. The pledge includes annual support and the sponsorship of several events. Mount Vernon’s July 4 celebration is particularly meaningful, as the patriotism on display goes beyond the special made-for-daytime fireworks: Each year, the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services holds a naturalization ceremony for 50 to 100 new citizens. “Boeing is proud to welcome these new citizens and celebrate the diversity that makes us all stronger,” said Ziad Ojakli, Boeing’s executive vice president for government operations.

The company also sponsors Mount Vernon’s official commemoration ceremony for Purple Heart Day (August 7) to pay tribute to the oldest American military decoration. It is especially poignant that members of the Military Order of the Purple Heart are recognized at the home of George Washington. (Purple Heart veterans are admitted free to Mount Vernon 365 days a year.) For all active duty, former, or retired military personnel, Boeing sponsors Mount Vernon Salutes Veterans, which provides them free admission on Veterans

Day, November 11. “Boeing values the leadership, integrity, and critical skills that veterans bring to the workforce, and we are committed to building better lives for transitioning military service members, veterans, and their families,” said Linwood Ham, Boeing’s director of military and veteran affairs. “This is just one small way we can thank them for their service to our country.”

Boeing’s Ziad Ojakli offers remarks at a July 4 naturalization ceremony at Mount Vernon.

What’s more, Boeing serves as a platinum sponsor for the annual Spirit of Mount Vernon Sunset Reception and Dinner (held in October), which brings the government affairs community to the estate to support its education and historic preservation mission. In 2023, the event hosted a record 950 guests; this year, the goal is to raise more than one million dollars

to secure the foundation of the Mansion in time for the country’s semiquincentennial in 2026.

Inspired by the leadership and determination of President Washington, Boeing has been a proud partner in carrying his legacy forward to the next generation by supporting civic education and engagement in communities across the country.

THERE ARE MANY WAYS TO SUPPORT MOUNT VERNON. TO LEARN HOW, EMAIL SUPPORT@MOUNTVERNON.ORG.

In 1818, John Adams reflected rhetorically on the nature of the American Revolution.

“But what do We mean by the American Revolution? Do We mean the American War? The Revolution was effected before the War commenced. The Revolution was in the Minds and Hearts of the People.”

In Adams’s view, the political and social revolt had already occurred by the time gunfire was exchanged at Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts in April 1775. If so, then 1774, the last full year before the start of the war—the year by which American colonists’ thoughts and feelings about Britain had become set—is one of the most pivotal years in American history.

What exactly changed in the hearts and minds of those colonists 250 years ago that led them to rebel against such a powerful and entrenched system as the British Empire? Historian Carl Becker wrote in 1908 that the Revolution was a contest to decide “the question of home rule” and “who should rule at home.” While the process of answering the second of those questions—what specific sort of government would they create for themselves—would extend years beyond the Revolutionary War, by the end of 1774 most colonists had already decided on the first—that they had a right to self-government.

WAR OF WORDS

The Road

Special Section: More than two years before

Patrick Henry utters his famous words at the Second Virginia Convention in Richmond, Virginia, in March 1775; among the delegates was George Washington (top). Colonists’ anger against Britain had been building, with protest flags (inset) as visible symbols.

to Revolution

the Declaration of Independence, a new nation was already taking shape

Competing Visions

Indeed, most American colonists— even many Loyalists who chose not to rebel—argued that they had always ruled themselves, and that by imposing increasingly restrictive measures, the British Parliament was trampling on their rights and liberties. Meanwhile, in the eyes of distant British lawmakers, Parliament was merely exercising its sovereign authority to govern. Though the first indications of this deep disagreement arose with the controversy over the Stamp Act in 1765, it was another nine years before the outlines of these opposing points of view became clear.

What turned British subjects into American revolutionaries in 1774? In her 2020 book, 1774: The Long Year of Revolution [see sidebar, opposite], historian Mary Beth Norton points out that the year did not begin on a rebellious note. As news of December 1773’s Boston Tea Party spread south and west from New England, many colonists reacted negatively to the event and argued that the East India Company should be compensated for those losses. George Washington, long dubious about British rule [see story, page 22], nevertheless expressed widely shared disagreement with, and dismay over, the Tea Party

protestors’ destruction of private property. While “the cause of Boston the despotick Measures in respect to it I mean now is and ever will be considerd as the cause of America,” he emphasized that he did not mean “we approve their cond[uc]t in destroyg the Tea.”

Deepening Crisis

The consensus colonial perspective was that if specific individuals broke the law, then punish them. But Parliament responded to the Tea Party with a series of blanket measures that became known as the Coercive (or Intolerable) Acts, and colonial reactions to these

INFLECTION POINT Many American colonists, including Washington, decried the December 1773 destruction of private property at the Boston Tea Party by a group called the Sons of Liberty, but the punitive British response only fanned the flames and reinvigorated rebellious fervor.

punitive laws reinvigorated rebellious fervor. When, in late March 1774, the Boston Port Act threatened to stop the trade that was the city’s lifeblood, people throughout the colonies viewed this as yet another example of Parliament’s trampling of their rights. Such an overreaching response to a criminal act smacked of the arbitrary power antithetical to the rights of Britons. And so it was news of the Boston Port Act that sparked community meetings throughout the colonies that produced dozens of statements of rights, grievances, and protest actions, the most famous of which is the Fairfax Resolves. [See story, page 30.]

Tensions eased, and relations might not have worsened but for passage of the next two Coercive Acts in late May— the Massachusetts Government Act and the Administration of Justice Act. Under these laws, many state officials previously elected by the people of Massachusetts would now be appointed by the king or the royal governor. Additionally, the royal governor could determine whether people should be charged with crimes, and British officials could move trials from Massachusetts to other jurisdictions within the empire. To many Americans, the first of these laws represented a fundamental change to the colony’s constitutional structure— an end to government by consent. The second rendered the justice system arbitrary and ineffectual by making it too difficult for the people to seek redress of their grievances.

As the First Continental Congress met in the fall, three events—in New England, Maryland, and New York—clarified the risks of spontaneous, unorganized resistance. From Boston, news quickly spread that six people had been killed

while preventing the British seizure of gunpowder from a city arsenal, and that British ships were bombarding the city with cannon fire in response. Before the rumor was proved false, area militias had started organizing for armed confrontation. In Annapolis, a local committee detained the merchant ship Peggy Stewart for carrying East India Company tea. Although the ship’s owner agreed to destroy the tea and apologized for violating non-importation measures, an extreme opposition faction forced him to burn the ship. And in New York in December, when the royal customs officer attempted to seize chests of arms and ammunition aboard the Lady Gage after King George III had prohibited weapons shipments to the colonies, a group of self-identified Sons of Liberty intervened and seized the cargo themselves.

Nascent Nation

The events of late 1774 clarified for the colonists that deadly conflict, widespread property destruction, and the suppression of rights were dangers created by an ineffective and unconstitutional government. Representatives meeting at the First Continental Congress concluded that a unified course of action was crucial. The resulting Articles of Association were written to coordinate resistance to British authority with commercial boycotts and embargoes.

But more important than the strategy of resistance was the fact that Virginians, Pennsylvanians, South Carolinians, and colonists from across British America had created their first regularly functioning, inter-colonial governing structure that would eventually lead to the founding of a new nation.

The Year of Living Dangerously

If there’s just one title on your reading list in 2024, make it 1774. The book won its author Mary Beth Norton the George Washington Prize (co-sponsored by Mount Vernon) in 2021. It chronicles the often overlooked developments of exactly 250 years ago and charts the revolutionary transformation of American resistance to Britain, from the destruction of tea in Boston to the marching of British troops on Lexington and Concord. According to the jury, “This work helps us see just how colonial leaders ‘practiced independence in thought and deed’ long before the Declaration of July 4, 1776.”

The Gathering Storm

A timeline of the dramatic events that led to the Revolutionary War and to George Washington assuming command of the Continental Army

1763

The Treaty of Paris ends the French and Indian (or Seven Years’) War. King George III creates the Proclamation Line, declaring that no American colonists can settle beyond it. Americans reject the line and begin moving west.

1765

To pay for troops in America, the British issue a stamp tax on all paper products. Americans protest the tax, declaring, “No taxation without representation.”

1766

Parliament repeals the tax but declares it retains the right to make laws for the colonies.

1768

Parliament creates new American taxes on vital goods imported into the colonies. Thousands of redcoats are stationed in Boston.

1769

George Washington and George Mason create the Virginia Association to enforce the boycotts of British imports.

1770

The Boston Massacre leaves five Bostonians dead in the streets. Parliament repeals its taxes on everything — except tea.

1773

Bostonians destroy imported tea during the Boston Tea Party.

MARCH 1774

Parliament calls for martial law in Boston and orders the harbor closed.

JULY 1774

The Fairfax Resolves, written by George Mason and George Washington, promise to resist Parliament on behalf of Boston.

SEPTEMBER 1774

The First Continental Congress meets in Philadelphia to protest Parliament’s actions, which colonists call “the Intolerable Acts.”

JANUARY 1775

British general Thomas Gage promises to uphold the law, with force if necessary.

MARCH 1775

In a rousing speech to the Second Virginia Convention, Patrick Henry declares, “Give me liberty or give me death!”

PRELUDE TO WAR

Clockwise from bottom left: An American political button, perhaps the first of its kind, decries the Stamp Act; George Washington, military veteran and legislator; King George III of Britain; a colored engraving by Paul Revere of the so-called Boston Massacre; Washington takes command of the troops; and Patrick Henry delivers his famous rallying cry.

APRIL 1775

Fighting breaks out at Lexington and Concord—“the shot heard ’round the world.”

JUNE 1775

The Second Continental Congress names George Washington commander in chief of the Continental Army. Two days later, the British win a costly victory at the Battle of Bunker Hill, overlooking Boston.

The Making of a Statesman

Over 16 years as a legislator, George Washington, Virginia burgess, came to appreciate the authority of representative government

By David L. Preston

POLITICAL CANVAS

Painted during a time of imperial tensions, Charles Willson Peale’s famous 1772 portrait of Washington in his Virginia regimental officer’s uniform at once evoked pride in his military achievements during the late war and held a veiled promise of how that experience might be wielded in defense of American rights in the future.

23 GEORGE WASHINGTON’S MOUNT VERNON

LEGISLATIVE GAMBIT

Washington (far left) and other delegates at the First Continental Congress in 1774 sought a legislative solution to a rift with Britain. Although the painting inaccurately depicts him wearing his regimental uniform, he would be warring with British general Thomas Gage (right) less than a year later.

IT WAS AUGUST 1775, during the early days of the Revolutionary War. George Washington, commander in chief of the Continental Army, and his British counterpart, Thomas Gage—who had known each other since their service together during the French and Indian War 20 years earlier—were exchanging testy missives over the treatment of captured American soldiers. Gage, while extolling British mercy to rebel prisoners, declared, “I acknowledge no Rank that is not derived from the King” and accused Washington of acting under “usurped Authority” from an extralegal Continental Congress.

Washington’s reply: “You affect, Sir, to despise all Rank not derived from the same Source with your own. I cannot conceive any more honourable, than that which flows from the uncorrupted choice of a brave and free People—The purest Source & original Fountain of all Power.” Inverting Gage’s top-down, king-derived conceptions of rank, honor, and power, Washington exalted bottom-up republican principles of virtue, consent of the people through elected representatives, and the authority of the Continental Congress. Contemporaries were moved by his defense of republican government when his correspondence with Gage was published later that year. How had Washington come to believe that the people were the “original Fountain of all Power”? How had he developed such fully formed republican convictions by July 1775, when he took command of the Continental Army? Delegates to the Continental Congress such as John Adams remarked on Washington’s extensive military qualifications to command, going back to his French and Indian War experiences. Historians and biographers have followed suit, emphasizing the important formation of Washington’s leadership on the American frontier, while

Washington’s service

in the House of Burgesses, which

coincided with growing colonial resistance to British imperial policies in the 1760s, also functioned as an incubator of his republican political beliefs as well as an emerging American identity.

glossing over perhaps the most important aspect of his ability to command and lead.

A New Civic Role

Washington possessed a deep reservoir of legislative experience. Indeed, he had served for more than 16 years as an elected legislator, far longer than his five years of military service during the French and Indian War. His legislative career from 1759 to 1775 encompassed service in the Virginia legislature (known as the House of Burgesses), as well as the First and Second Continental Congresses. Although not marked by fiery speeches in the vein of Patrick Henry or crucial legislation and political treatises in the manner of Thomas Jefferson, those years saw Washington’s transformation from a loyal subject of the Crown to a republican statesman and revolutionary leader. His civic education was as vital as his military education, as both were the sure foundation of his quintessential leadership in the war to come and his future presidency.

Washington’s understanding of civil authority matured over the course of his legislative career, just as his military attributes had been sharpened by defeat and setbacks in the 1750s. While he was commander in chief of Virginia forces during the French and Indian War, his relationship with the Virginia legislature was tempestuous and often adversarial. The young colonel—he was only 25—once vented his frustrations in a 1757 letter to his British counterpart, the Earl of Loudoun. He excoriated the “Chimney Corner Politicions” in Williamsburg who were at once “thirsting for News, & expecting by every express a circumstantial account of the Siege, and reduction of Fort Duquesne.” In Washington’s estimation, the legislature’s “Jumble of Laws” had locked him into a static and futile defense of the Virginia frontier and frustrated his military efforts. Nevertheless, Washington and his Virginia forces aided the British Army’s successful effort to eject the French from the Ohio Valley in 1758. While

on that campaign, he received word that he had been elected to the House of Burgesses from Frederick County. With the war winding down, he resigned his military commission and focused on his new civic career, as well as his approaching marriage to Martha Custis in early 1759. Washington was formally seated in the House of Burgesses in February 1759 and quickly discerned the contours of 18th-century politics. Virginia’s colonial government was supposed to function in microcosm like the mixed constitution of Great Britain, in a balance among the monarchy, the aristocracy in the House of Lords, and the representative House of Commons. It had a royal governor with viceregal powers; a small, appointed council that functioned as the upper house of the legislature; and the lower house composed Virginia’s elected burgesses. Modeling itself after the House of Commons, the House of Burgesses took the lead in passing legislation, levying taxes, and defending British political liberties and local privileges against royal encroachments. In practice, the American provincial legislatures had amassed political power at the expense of British governors and their diminutive councils. Virginia’s House of Burgesses was dominated by wealthy white men chosen by their peers. Candidates for office traditionally did not campaign for votes; rather, their most ardent supporters took the lead in advancing their public virtues. For the landed gentry, elected office was a measure of their provincial power and stature within their local community. Although Washington had represented Frederick County since 1759, it was significant that his Fairfax County neighbors elected him as one of their burgesses in 1765, and he served in that office until 1775.

The Game of Politics

Washington’s service in the House of Burgesses, which coincided with growing colonial resistance to British imperial policies in the 1760s, also functioned as an incubator of his republican political beliefs, as well as

LESSONS IN CIVICS Washington represented Frederick County, and later Fairfax County, in Virginia’s House of Burgesses (above), in Williamsburg. He served alongside Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, and other notable Virginians, meeting on the first floor in the east wing of the Capitol (below).

an emerging American identity. Since 1619, the power and independence of the elected assembly had grown steadily. Even as early as 1754, Virginia’s royal governor, Robert Dinwiddie, found the House of Burgesses “very much in a Republican way of Thinking.” Successive irritations over imperial policy only underscored the virtual independence of the American colonies that British administrators routinely complained and worried about. From his legislator’s perch, Washington grappled with the unresolved questions that would eventually lead to war: the right of Americans to be taxed by their own elected colonial legislatures, the extent of the British government’s authority over its American territories, and the very nature of political representation.

Washington’s political education began with an assignment to the important Committee on Propositions and Grievances that oversaw much of the internal political negotiation within the chamber. He frequently reviewed ordinary colonists’ complaints and petitions for financial relief. Some petitioners were widows of soldiers killed in the late war or veterans he had once commanded, still struggling with the effects of wounds or wartime service. Washington also experienced two major wars affecting Virginia—Pontiac’s War (1763) and Dunmore’s War (1774)—from the very seats occupied by those “Chimney Corner Politicions” he had once condemned. He began to comprehend how difficult it was for a legislative body to prosecute a war, particularly with regard to finance, recruitment, and supply. He came to appreciate the labor and art of political communication, consensus-building, and mastery of legislative procedures.

Becoming American

contemporary works, such as Cato’s Letters and John Dickinson’s Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, deepened his understanding of history and imperial politics. He absorbed viewpoints and arguments opposing Parliament’s actions and increasingly believed that the British threatened to demolish the liberties of all American colonists.

Imperial issues in the 1760s also reignited the stillsmoldering embers of his discontent with the British imperial system that he’d experienced during the French and Indian War. British policy in the 1750s had given precedence to regular army officers holding the king’s commission and relegated colonial officers like Washington to second-rate status. As early as 1757, Colonel Washington expressed a sense of “being Americans”—not Virginians—in a British world that stymied his ambition of gaining royal status for the Virginia regiment he commanded. And Britain’s restrictive postwar land policies, such as the Proclamation Line of 1763, challenged his and other Virginians’ efforts to expand into the very Ohio Valley lands for which they had fought.

READING LIST

Washington embarked on a program of self-education, constantly adding to his extensive library. His reading of classical and contemporary works deepened his understanding of history and imperial politics.

At the same time, Washington embarked on a program of self-education, constantly adding to his extensive library. His defense of republicanism to Thomas Gage mirrored ideas in Robert Dodsley’s 1748 The Preceptor—a work he had ordered for his stepson’s education and apparently read himself. His reading of classical and

Washington’s turn toward resistance was rapid and decisive. Although he had registered discontent over the 1765 Stamp Act, his attitudes had hardened by 1769. Burgess Washington sarcastically referred to “our lordly Masters in Great Britain” who would be “satisfied with nothing less than the deprivation of American freedom”— again referring to a broader panoply beyond Virginia. Believing that petitions to Parliament and the Crown were ineffective, Washington spearheaded Virginia’s non-importation association that year. Virginians would pledge to cease imports and consumption of certain British goods to exact economic pressure on British merchants and policymakers. He also foresaw, earlier than his peers, the necessity of taking up arms in defense of American rights. Although he qualified that force should be the last resort, he enjoined his friend George Mason in 1769, “That no man shou’d scruple, or hesitate a moment to use [arms] in defense of so valuable a blessing, on which all

He absorbed viewpoints and arguments opposing

Parliament’s actions and increasingly believed that the British threatened to demolish the liberties of all American colonists.

the good and evil of life depends; is clearly my opinion.”

Painted during a time of imperial tensions, Charles Willson Peale’s famous 1772 portrait of Washington in his Virginia regimental officer’s uniform at once evoked pride in his military achievements during the late war and held a veiled promise of how that experience might be wielded in defense of American rights in the future.

Toward a New World Order

Perhaps the pinnacle of Washington’s political emergence was his involvement in the Fairfax Resolves, an influential declaration of American constitutional rights that included

an unequivocal call for a congress drawn from all 13 colonies. The Resolves upheld the “fundamental Principle of the People’s being governed by no Laws, to which they have not given their Consent, by Representatives freely chosen by themselves.” [See story on page 30.] As chair of the general meeting of Fairfax County freeholders in July 1774, Washington had a signal role in overseeing its passage, and the meeting specifically designated him, along with another delegate, to present the resolutions to the First Virginia Convention in Williamsburg.

Washington’s 1775 letter to Gage underscored that the American army’s first commander served under the authority of the Second Continental Congress. His experience as a legislator proved vital to his leadership between 1775 and 1783, particularly in how he interfaced with Congress and the state legislatures and navigated political challenges. No other rival to command of the Continental Army—not Charles Lee, Horatio Gates, or Thomas Conway—had his depth of political experience and skill.

Throughout the war, he consistently upheld Congress’s authority, even when (to his dismay) it undermined his own or went counter to his better military judgment. Washington’s example became the template for future civil-military relations in the United States, in which military forces are subordinate to civilian authority. At the conclusion of America’s eight-year-long war for independence in 1783, Washington resigned and surrendered his commission back to the authority that had given it: Congress. It remained, as it always had been in his mind’s eye, “this August body under whose orders I have so long acted.”

David L. Preston, PhD, is the General Mark W. Clark Distinguished Professor of History at the Citadel, in Charleston, South Carolina. His book, Braddock’s Defeat, won the Guggenheim-Lehrman Prize in Military History for 2015.

ANGER REIGNITED Washington sympathized with Bostonians, shown in this 1774 mezzotint as political prisoners of the British.

TWO GEORGES

In July 1774, George Mason traveled to Mount Vernon to work with Washington on what would become the Fairfax Resolves.

An Argument for Autonomy

George Washington and his neighbor, George Mason, crafted one of the most comprehensive lists of colonial grievances against British rule

By Samantha Snyder

COMPLAINT LETTER

Running more than 3,000 words over nine pages, the Fairfax Resolves are one the most detailed, comprehensive, and cogent sets of resolutions against British policies that survive from that crucial time period.

AFTER THE SEVEN Years’ War ended in 1763, Britain—trying to recoup debts incurred during the war against France over land claims in North America— began to pass laws affecting the economies of the American colonies. Starting with the Stamp Act in 1765, Parliament taxed colonists on numerous goods and imposed higher duties on international trade.

By the summer of 1774, after Britain had passed four laws—what came to be known as the Coercive, or Intolerable, Acts—viewed by colonists as punishment for the Boston Tea Party, many colonists had had enough and called for a Continental Congress. John Adams, recently appointed as a delegate from Massachusetts, proclaimed it was “highly expedient” for representatives of the colonies to meet to “consult upon … the Miseries to which [the colonies] are reduced to by the Operation of Certain Acts of Parliament respecting America.” His words resonated with many.

Politicians in the 13 colonies established committees of correspondence to organize and to express their solidarity with the people of Boston. Each colony handled the lead-up to the Congress differently. In Virginia, representatives from 40 (of some 60) counties decided to craft separate lists of resolutions, or “Resolves.” These were to be discussed and adapted at a meeting of the House of Burgesses (an assembly of democratically elected representatives from counties in Virginia), in Williamsburg, in early August.

In mid-July, George Mason traveled up the Potomac River to Mount Vernon to meet with George Washington to work on the list for Fairfax County. Over the

course of several weeks, the two men drafted the Fairfax Resolves. These would turn out to be the most detailed, comprehensive, and cogent set of resolutions that survives from any county or colony. While the Virginians expressed no desire for independence from Britain, they were adamant that the present situation was untenable. As Mason and Washington wrote in Resolve 8, “It is our greatest Wish and Inclination, as well as Interest, to continue our Connection with, and Dependence upon the British Government; but tho’ We are its Subjects, we will use every means which Heaven hath given Us to prevent our becoming its Slaves.”

The Fairfax Resolves run more than 3,000 words over nine manuscript pages. The 24 resolutions cover the fundamental rights of American colonists. They express a desire for change. Representation in Parliament, and control over taxation, military forces, and judicial powers are among the topics covered. The surviving manuscript copy of the Resolves, written in George Mason’s hand, is in the George Washington Collection at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. Here are some of its most interesting passages. •

RESOLVE 6

No Taxation Without Representation

The representatives argued that only colonial legislatures had the right to levy taxes on the colonists. This central argument was echoed throughout the resolutions and during the debates of the First and Second Continental Congresses. (The Second Continental Congress was called in the spring of 1775, following the Battle of Lexington and Concord. This Congress led to the Richard Henry Lee Resolution, also known as the Resolution for Independence. Lee’s Resolution was the first draft of the Declaration of Independence.) Resolve 6 claims that “Taxation and Representation are in their Nature inseparable; that the Right of withholding, or of giving and granting their own Money is the only effectual Security to a free people against the Encroachments of Despotism and Tyranny …”

RESOLVES 17 AND 20

Questioning the Slave Trade

Many colonists made the distinction between the Atlantic slave trade, which brought enslaved people directly from Africa to the colonies, and the institution of slavery itself. Washington and Mason are examples of this. Though Washington and Mason may have publicly supported the abolishment of the trade, both were enslavers until their deaths. The contradictory nature of Resolves 17 and 20 demonstrate ambivalent and evolving views. Resolve 20 proclaims the trade to be “wicked, cruel, [and] unnatural.” However, in Resolve 17, colonists promise to reinstate the trade after Parliament met their demands. (The Atlantic slave trade was officially abolished in the United States in 1808, with the Act Prohibiting the Importation of Slaves.)

A map cartouche depicting Virginia’s economic prosperity, including its reliance on enslaved labor.

RE SOLVE 14

These United Colonies

The men who framed the Fairfax Resolves joined in calling for the convening of a Continental Congress, a formal way of unifying all ideas for change. In Resolve 14, Mason wrote that Virginians should put aside every “jarring Interest and Dispute, which has ever happened between these Colonies, and bury them “in eternal Oblivion.” These words helped lay the foundation for the start of a new nation, in which colonists would be one united front.

RESOLVE 5

Toward Self-Government

Resolve 5 advocates for the right of colonists to govern themselves, within limits. The colonists believed that their poor treatment by Parliament was “incompatible with Privileges of a free People, and the natural Rights of Mankind.” They subsequently determined to establish a permanent government to keep themselves in a “State of Freedom and Happiness” rather than allowing Parliament to reduce them “to Slavery and Misery.” Self-government brought the colonists closer to the Enlightenment-era ideals of natural, inalienable rights—that of life, liberty, and property.

Washington en route to Philadelphia.

British troops landing in Boston in 1768 to quell riots following the passage of the Townshend Acts.

RESOLVES 11 AND 22

The Tea Party Went Too Far...

But It Wasn’t Wrong

These Resolves tried to thread the needle between opposition and conciliation. The Fairfax County representatives indicated that Virginia might be “willing to contribute towards paying the East India Company the Value” of the tea lost in Boston. Nevertheless, they insisted that regardless of the public or private ownership of the tea, the company was one of the “tools and instruments of oppression,” in relation to the colonists’ broader economic struggles and “distress.” Further, despite giving their tacit support to the Boston Tea Party, Washington and Mason held that British punishment on Boston “shall not hold the same to be binding upon Us” as Virginians, and absolved themselves of any culpability.

RESOLVE

9

Not Looking to Leave Britain

Resolve 9 claims any talk of a separate country to be malicious rumors being propagated by factions in Britain. According to Mason and Washington, the “British Ministry … are artfully prejudicing our Sovereign, and inflaming the Minds of our fellowSubjects in Great Britain, by propagating the most malevolent Falsehoods; particularly that there is an Intention in the American Colonies to set up for independent States….” They express a sentiment that “by breaking in upon the American Charters,” and “no longer remain[ing] dependent upon the British Crown,” things would end in the “Ruin of both Great Britain and her Colonies.” Though they deny seeking an independent state at that moment, it was to prove true just two years later— many of the colonists having come around to the idea.

What Happened Next?

The representatives for Fairfax County presented their resolutions at the House of Burgesses in Williamsburg on August 1, 1774. The burgesses then elected seven men, including George Washington, to serve as delegates to the First Continental Congress, which met in Philadelphia in September and October 1774.

After two months of debate, the First Continental Congress resulted in a “Declaration of Colonial Rights,” a formal statement sent to England detailing grievances and the intention to boycott British goods. The document borrowed many of its ideas from the Fairfax Resolves.

Samantha Snyder is the research librarian at the George Washington Presidential Library.

George Mason: Drafting Democracy

One of the least known of the founders, George Mason played an important role in Virginia politics and the early development of the United States. He and his friend and neighbor George Washington were both vestrymen in Truro Parish. Washington and Mason also served in the Virginia House of Burgesses together. In 1767, they drafted the Virginia Resolves, advocating for the boycott of all British goods in protest of the acts imposed by Parliament.

Seven years later, the two collaborated again to write the Fairfax Resolves. In 1776, Mason drafted the Virginia Declaration of Rights, the first state declaration of the fundamental human liberties that the government should protect, and it greatly influenced America’s founding documents. Mason served as a delegate at the 1787 Constitutional Convention and many clauses bear his imprint, but he did not sign the final document. He had called for a bill of rights to be included, as well as an immediate end to slavery. Washington and Mason fell out over Mason’s refusal to sign. Mason’s fight for a bill of rights led fellow Virginian James Madison to introduce one in 1789; these amendments to the Constitution were ratified in 1791, a year before Mason died at his plantation, Gunston Hall.

Philadelphia’s Carpenters’ Hall hosted the First Continental Congress.

What Would Washington Do?

Kyle Freund helps students gain new perspectives on U.S. history

After teaching U.S. history to eighth graders in Wisconsin’s Stoughton Area School District for a decade, Kyle Freund has a new role: mentoring new educators in grades six through 12, leading professional development and instructional coaching, and analyzing student learning. He’s visited Mount Vernon multiple times, including a stint in the summer of 2023 at the George Washington Teacher Institute (GWTI). “I feel very lucky to have been able to be on the historic grounds so many times and really enjoyed getting access through GWTI to the Mansion, including watching the sunrise on the piazza.”

You taught U.S. history to eighth graders for 10 years. What methods did you use to make 18th-century events resonate with 13- and 14-year-olds, particularly the lead-up to the Revolutionary War? I help my students put themselves in the shoes of people who lived at the time so they can better understand their perspectives. For example, a favorite activity of my students is playing the virtual game “Be Washington,” developed by Mount Vernon. This fast-paced interactive leadership experience puts my students in the role of Washington himself as either general or as president in order to make

decisions in crises that Washington faced in those roles.

Has teaching about George Washington and the Founding Era changed in the time you’ve been teaching it? It has changed in the decade I have been teaching it. Attending GWTI helped me become a more effective educator about Washington. I try to teach about him as a human being capable of the great heroics we are all familiar with, but also capable of the cruelty of being a slaveholder. GWTI helped me gain a sense of confidence in teaching Washington’s entire history. Knowing that Mount Vernon, an

institution tasked with preserving his legacy, does not shy away from acknowledging his role in the continuation of the injustice of slavery gives me more confidence as well.

How else has traveling to Mount Vernon influenced how and what you’ve taught? So much of teaching history is storytelling. Having the opportunity to visit Mount Vernon, including access to the grounds, has allowed me to vividly describe these places and the people who lived there in ways that engage my students. I was allowed to be a part of a private wreath-laying ceremony at the final resting place of the enslaved community at Mount Vernon. I use that experience to tell the stories of those who lived in the shadows of our founders but whose stories have often not been told and are only now being recognized through ceremonies such as this. To further this learning for students, I use Mount Vernon’s powerful virtual exhibit Lives Bound Together to help students understand the story of all who lived at Mount Vernon.

What lessons have you learned related to teaching U.S. history over the past decade that you’ll pass on to the educators you’ll be mentoring in your new role?

Here’s what I’d like to share: Be true to the historical record and prepare each day to the fullest. Also, always find ways to connect your students to the past. Lastly, don’t rest on your laurels.

Constantly challenge yourself to be a student of history yourself. GWTI has given me access to some amazing scholars, historians, and professors around the country whom I know I can reach out to with any questions.

Kyle Freund, pictured in a seventh grade social studies classroom at River Bluff Middle School in Stoughton, Wisconsin (above), mentors educators by modeling teaching practices (opposite).

Hard-Hat Mansion Tour

Special guests view rarely seen aspects of the first president’s home

Aselect group of donors joined the Regent, Vice Regents for Illinois and Massachusetts, Vice Regent emerita for Washington, and Douglas Bradburn, president and CEO, for a special behind-thescenes experience titled “The Art and Science of Historic Preservation: Securing George Washington’s Mansion” on May 29.

Guests toured the Mansion with a special hard-hat inspection of the preservation work underway in the cellar, followed by cocktails and dinner. Attendees spoke with Mount Vernon’s historic preservation staff and viewed structural components, or fabric, of the nearly 300-year-old

building not seen in more than a century. The exploration included commentary on the importance of the Mansion as the place where George Washington and others gathered to discuss the formation of a new government that would be a nation of free people, thereby solidifying the Mansion as an enduring symbol of democracy.

The Mansion Revitalization Project is an unprecedented effort to preserve George Washington’s beloved Mansion for generations to come. The work will ensure Mount Vernon remains a symbol of democracy and independence well beyond 2026, the country’s 250th birthday.

The group proceeds along the south colonnade to the Mansion for a hard-hat tour of the cellar.

Campaign Continuation

Fundraising for Strengthening Our Foundations: The Campaign for Mount Vernon has surpassed $175 million, and the Campaign will continue through 2026, when all eyes will turn to the home of the father of the country.

As Mount Vernon tackles immediate preservation challenges through the Mansion Revitalization Project and ensures its educational resources and programs are second to none through upgrades to exhibits and enhancements to teacher programming, your support is more important and appreciated than ever

Inspection tour: Douglas Bradburn, Mount Vernon’s president and CEO, engages guests at dinner (above); Regent Margaret Nichols and Vice Regent Andrea Sahin tour the cellar (left).

Thomas Reinhart, director of preservation, explains restoration efforts to the Regent and Remmel Dickinson (center); the group poses at the center door (lower right); Susan Schoelwer, executive director of historic preservation and collections, outlines the phases of construction (lower left).

Annual Fundraiser

The Founders Committee supports the conservation of New Room furnishings

The Founders, Washington Committee for Historic Mount Vernon hosted its annual fundraising event on Sunday, June 2. Proceeds supported the conservation of paintings and chairs in the New Room as part of the Mansion Revitalization Project.

More than 180 guests enjoyed cocktails on the east lawn, a dinner buffet, views of the Potomac River, tours of the Mansion, and an opportunity to see some of the bottles recently excavated from the Mansion’s cellar.

Attendees of the event could also experience the impact of their philanthropy from past years by viewing rooms in the Mansion, such as the Front Parlor (2016 and 2017) and the Old Chamber (2023), that were

restored thanks to previous support from the Founders. The event raised more than $228,000 for the New Room project. The Founders’ philanthropic support, the support of its host committee, and contributions from event attendees and other donors will enhance the story of how George Washington set precedents for the new nation as a leader and a patron of the arts.

TO LEARN MORE ABOUT THE EVENT AND THE FOUNDERS COMMITTEE, VISIT MOUNTVERNON.ORG/FOUNDERS.

Founders Committee chair Valerie Burden addresses the crowd (upper right); guests enjoy the reception on the east lawn (upper left and lower right); Mount Vernon archaeologists display some of the bottles recently excavated from George Washington’s cellar (lower left).

Homecoming Weekend

The Connoisseur Society gathered for events at Mount Vernon and the surrounding area

Members of the Connoisseur Society of Mount Vernon gathered for their annual Homecoming on May 30 and 31.

The group toured the newly refurbished Diplomatic Reception Rooms at the Department of State with Virginia Hart, director and curator of the Diplomatic Rooms and a member of the Founders Committee.

Considered one of the finest collections of American art and design in existence, the collection focuses on the Colonial and Federal periods and features treasures by Gilbert Stuart and others.

After lunch at the Metropolitan Club, the group enjoyed a curator-led tour of the presidential portraits exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, as well as the home and art collection of the historical Lafayette House in Alexandria,

where the Marquis de Lafayette stayed during his grand tour of the United States in 1824. The day concluded with a dinner reception at the home of Connoisseur Society chair Lucy Rhame.

The gathering’s second day was held at Mount Vernon, where participants viewed an exhibit of the Peter Presidential collection among other recent acquisitions to the permanent collection, as well as the recently discovered 250-year-old glass bottles containing cherry remains that were unearthed during the Mansion’s cellar excavation.

For many, the Homecoming led into the annual Mount Vernon Symposium, and Connoisseurs left with a renewed appreciation for the art and history that define the nation’s past.

Members of the Connoisseur Society tour the exhibition of presidential portraits at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.

Northern Virginia’s Mother Church

Pohick Church, attended by George Washington, celebrates a milestone year

Jus t seven miles from Mount Vernon, 18th-century Pohick Church, the first permanent church in colonial Virginia to be established north of the Occoquan River, was attended by such well-known area residents as George Washington, William Fairfax, and George Mason. Following in his father Augustine’s footsteps, George Washington became a vestryman of Truro Parish in July 1762, serving for 23 years. In 1767, the vestry embarked on replacing and rebuilding its parish church on a grander scale, constructing it out of the elegant and durable colonial brick seen today. Much of the work was done by enslaved people. The building was completed in 1774, just before the outbreak of the Revolutionary War. Over the next century, the church would endure ongoing cycles of neglect and repair, experiencing its worst destruction during the Civil War when occupied by Union troops. Services would resume in 1874, and a major restoration began in 1890, supported by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, among others. In 1882, the MVLA began renting the pew formerly occupied by George Washington, and members would attend Sunday service during their annual and biannual meetings at Mount Vernon. This year, Pohick Church celebrates its 250th anniversary. A bronze plaque contains the names of all known individuals who worked on the structure, including those in bondage. It continues to be an Episcopal church in Lorton, Fairfax County, and free, self-guided tours are offered daily.

In 1912, Pohick Church dedicated a pew to Ann Pamela Cunningham, the first Regent of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, for her work preserving the home of its most famous parishioner.

An image of Pohick Church, taken in the early 1900s (above). In May 1948, MVLA members posed for a group photo (below).

I think the Parliament of Great Britain hath no more Right to put their hands into my Pocket, without my consent, than I have to put my hands into your’s, for money.

George Washington to Bryan Fairfax 20 July 1774

P.O. Box 110, Mount Vernon, Virginia 22121