- Despite long days and heavy lifting, Bourda Market vendor Radha Danpat says she wouldn’t trade her work for an office job

- Kuru Kuru eddoe farmer shares the challenges, triumphs, and daily grind behind

By Shaniya Harding

WHEN he left the army in 1992, he traded his uniform for a cutlass and faith. Today, more than thirty years later, Justin Bacchus still rises before dawn, working seven days a week on the same 25 acres of land he carved from the dense Kuru Kuru foliage with his bare hands. Through floods, hardship, and hope, Justin has persevered and is now among the largest farmers in his community, often harvesting hundreds of pounds of eddoes.

In his interview with Pepperpot Magazine, Justin shared the ups and downs that have shaped his farm's growth, the hurdles that farmers and the government are trying to overcome, and—despite countless challenges— he says there are very few things he loves more than his farm.

Born and raised along the Berbice River, Justin was no stranger to agriculture. However, rather than ventur-

ing into farming like many of his friends and family, Justin became a soldier. His agricultural roots caught up with him in 1992, when he came to Kuru Kuru and saw eddoes being harvested for the first time.

“The first time in my life I ever plant eddoe is when I come in Kuku. My brotherin-law had a farm over the next side. He used to plant eddoe, and I used to go and help him plant eddoes and pull eddoe. I said, this is how the farming that I do. I just end up coming away as a soldier and I start cutting.”

Today, Justin’s farm covers some 25 acres, but this growth was slow and marked by dozens of losses and challenges.

“When this farm start, is me alone and God start this farm. I chop it down with a cutlass. I didn’t have power saw, so I chop it down with cutlass and axe. The first eddoe I reap was 200 bag of eddoe. I get $14 a pound. I go and I start build my house. And I start establish

this farm,” he said. In the years since the farm’s first crop, Justin says it has faced its fair share of losses, with challenges like flooding nearly ending the farm more than once.

Justin says he has been in love with farming since coming to Kuru Kuru, but there are still challenges he and his fellow farmers are working to overcome. One of the main hurdles, he says, is the combination of labour shortages and difficult accessibility. Justin’s farm rests on 25 acres of land, the large majority of which is swamp, needed for the proper cultivation of eddoes.

The challenge, however, comes with accessing the swampy farmland, leaving more than 10 acres of eddoes unharvested simply because of its location and the lack of workers willing to venture into the wetlands. “I get 10 acres over a hill. I left 300 bags of eddoe there for rot, because you have to drive around. It is so sad that there is no road. So, the farm just

left there, abandoned. Get eddoes, but they cannot pull. Who can bring it out? They can’t bring it out from so far.”

Issues with accessing the farm are a major hurdle in the farm-to-table process and just one of the challenges farmers face. Limited accessibility also increases production costs. “But the only problem now is we don’t have trans-

portation and the road, as you could see, very difficult for the workers, it is already expensive to pay workers on the farm and you got to pay workers extra for farther; it’s rough,” he said. While government intervention would be welcomed, Justin and many of his fellow farmers have carved their own paths through the swamp, creating

a unique network of interconnected routes connecting different areas of the farm. There are no rest days on a farmer’s calendar, according to Justin. Contrary to popular belief, his crops require constant attention. Every day, he follows a simple routine before heading to the farm. “As a farmer, I TURN TO PAGE VIII

By Shaniya Harding

MARKET vendors in Guyana, and countless other countries, are the movers and shakers of the market. Whether it’s fruits, vegetables, or unique produce, vendors serve as a vital and vibrant bridge between the farm, the farmers, and the tables of everyday Guyanese.

At just twenty-two, Radha Danpat has already spent seven years managing her grandfather’s business in the heart of Bourda Market. From six in the morning until sunset, she sells pumpkins, plantains, and watermelons with a pride that defies the perception that market work is “hard and old-fashioned”. In an interview with Pepperpot Magazine this week, Radha highlighted the ups and downs of market life, the everyday hustle and interactions, and why she loves her job so much.

While it may be unusual, Radha is one of the youngest market vendors Guyana has to offer. Though rare, she is also among the most dedicated to her craft. Her love for the market began when she was quite young, through her grandfather. “My grandfather owns this business here. He’s been in business for like thirty-something years, and I guess it’s just like a family tradition.” Radha fell in love with market life more than seven years ago. Although

- Despite long days and heavy lifting, Bourda Market vendor Radha Danpat says she wouldn’t trade her work for an office job

the biggest hurdles for vendors, Radha says it is necessary. “We have our suppliers all the way from the islands. Basically, we call in on the days when we need them to bring the load.

she has other siblings, Radha is the only one drawn to market vending. “It’s always been something in the family. Before my grandfather had his own business here, his dad did the same thing. So it’s like a tradition passed down through generations. I kind of just took it in. I have sisters and a brother, but they prefer to work in offices, while I prefer to be on the market selling these products.”

Since then, Radha has become a master of her craft, working with farmers and suppliers across the country to bring the freshest produce to hundreds of Guyanese daily. But she shared that this was not always what she imagined for herself. “I always imagined myself working in an office, but market work is so much better than people think.

The diverse experiences and interactions with customers have not only confirmed that the market is right for her; she believes market vending is not only a viable option for young people but also among the best they could have. “In the market, you get a different type of life experience.

You experience sales and the position itself on a different level, and you get to meet different types of people every day.” She added, “Honestly, it’s great. I can’t see myself working for a company at this point in my life.

I’ve been on the market for seven years, and I would say this is the best job I would ever recommend anybody to have: become a vendor on the market and sell.”

The day-to-day life of a market vendor is demanding. Radha starts her mornings around six-thirty, opening the stand and preparing produce for customers who begin arriving just minutes later. Some mornings are bustling, while others are quieter—a dynamic that requires patience and flexibility. “Sometimes in the morning we have a great deal of customers, and then there are days when it’s slow.”

She added that although unpredictable, market work follows a simple formula: “Some days are busy, and others are quite slow. It’s like a fifty-fifty type of thing. We work up to six in the afternoon. Market work is pretty easy: you put out, you sell, you supply your customers, and then you lock up and go home at the end of the day, ready for the next day.”

Radha’s selection of fruits and vegetables, which includes pumpkin, lime, and watermelon, was curated by her grandfather. These products come from various suppliers and farmers, often travelling long distances

They bring it up to Parika for selling, and then our guys who work the trucks bring the provisions or fruits down to the market here. It gets transported from Parika to here, but it mostly comes from the islands, like Bartica and Pomeroon and stuff,” she said. Although challenging, logistics are as much a part of the job as interacting with customers and managing the stand.

Market work is physically demanding, requiring stamina, strength, and constant activity. Radha works

long hours, often without breaks, moving and arranging heavy produce throughout the day. Despite her youth, she handles tasks that would challenge many older workers. She says although it takes a toll, it is part of the job she loves and does not intend to give up.

“I’m quite young, I’m only twenty-two, and at this age, I do the job of any middle-aged person. To lift a bunch of plantains, we’re talking about thirty to thirty-five pounds, sometimes twenty. I have days where I go home with pain—sometimes my head, my back, or my feet hurt—but I don’t let it stop me because that’s part of my journey,” she said.

Radha wants to challenge perceptions about young

people and agriculture— more specifically working in Guyana’s markets. She believes many avoid farming or market work because they are accustomed to the convenience of nine-to-five jobs with weekends off.

“A lot of young people these days just want to work the regular nine-to-five job and have weekends off, whereas this is seven days a week. On holidays we work half-days, but other than that, it’s every day.

You’ve got to be on your feet all the time and have your head on straight.” Yet she believes hard work and dedication are lessons young people need to embrace. “I would really encourage my generation to take things a bit

TURN TO PAGE IX

By Michel Outridge

WHEN Marlon Fraser was just 12 years old, his world changed dramatically. The passing of his father meant that the young boy from Martyrsville, Mon Repos, had to shoulder full responsibility for his family’s small farm.

But what could have ended a childhood instead became the beginning of a remarkable journey—one that has seen him rise as a promising leader in Guyana’s small ruminant industry.

“My father was my teacher,” Marlon recalled, reflecting on long days spent tending to Barbados blackbelly sheep and helping in the family’s fruit orchard.

“Everything I know started from those lessons at home.”

Taking over the reins so young wasn’t easy. But with determination and a clear vision, Marlon transformed tragedy into purpose. One of his main goals after his father’s death was to improve the genetics of his flock, creating animals that could meet the growing demand for better breeding stock and

higher-quality meat.

He has deep respect for the Barbados blackbelly, a native breed known for its adaptability, long body, and excellent mothering ability.

“The blackbelly is an amazing breed,” he explained.

“It’s prolific and well-suited for our climate. When bred with other high-performing breeds, the results are exceptional.”

That philosophy guided Marlon’s next steps. His turning point came when a fellow breeder gifted him a Katahdin-Dorper crossbred lamb—a gesture that would forever change his flock’s future.

“That lamb marked the start of my genetic improvement programme,” he said proudly.

With the support and technical guidance of the Guyana Livestock Development Authority (GLDA), Marlon began incorporating Dorper and Katahdin genetics into his flock. These breeds, imported through GLDA initiatives, have been key to boosting meat production and overall flock performance nationwide.

Today, Marlon manages about 50 sheep at his home in Martyrsville, housed in an elevated pen system that keeps the animals safe and healthy. With no open grazing space, he uses a cut-and-carry feeding method, supplementing with store-bought feed to maintain balanced nutrition. He also runs a fruit farm at Enterprise backlands, balancing both operations with discipline and care.

Over the years, his partnership with GLDA has proven invaluable. “The extension staff visit often, guiding us in feeding, nutrition, and genetics,” Marlon shared.

“The Region Four team, led by Ms. Ava Klass, and my area Livestock Extension Officers, Lydia Gopaul and Ronaldo Pancham, have been instrumental.

With their help, I’ve learned how important record-keeping is—traceability is really the lifeline of my operation. All my animals are tagged and separated to prevent inbreeding.”

Marlon also spoke highly of GLDA’s strict monitoring and quarantine procedures, which he admits he didn’t al-

ways appreciate as a younger farmer. “At first, I used to be impatient with all the rules,

paperwork, and quarantining when importing animals,” he said with a laugh. “But now I understand—it’s about protecting our industry. The GLDA team, including Dr Walrond, the CEO, is always ready to advise us on the right steps. That level of support is something I truly value.”

He believes this partnership between the government and farmers is a model of success. “It’s a real public-private partnership,” he emphasised.

“Because of GLDA’s work to import quality breeding stock, farmers like me now have more choices. We’re better equipped to meet market demand, especially with the oil and gas sector expanding and people having more disposable income for quality food.”

While the cost of intensive sheep farming can be high, Marlon said the returns make it worthwhile. His target each year includes three rounds of breeding animal sales and an average of twelve rams per month for slaughter. “It’s hard work, but it pays off,” he said with a satisfied smile.

His dedication recently earned national recognition when he took first place in the Small Ruminant Expo at the Rising Sun Turf Club in Weldaad, representing Region Four.

The competition brought together farmers from across Guyana, showcasing the country’s growing livestock excellence.

Looking ahead, Marlon is focused on expanding his flock to meet rising market demand while continuing to raise the bar on quality and efficiency.

“This journey has taught me patience, discipline, and the value of support,” he said. “With the right guidance and a clear plan, young farmers like me can help strengthen Guyana’s food security and build a stronger livestock industry.”

From a young boy managing his late father’s flock to a recognised champion in small ruminant farming, Marlon Fraser’s story is one of resilience, innovation, and hope—a reminder that with passion and perseverance, even the smallest farms can achieve extraordinary growth.

By Shaniya Harding

IN recent years, Guyana has reached major milestones in environmental sustainability, becoming a leader in conservation and climate action. The government, working closely with the nation’s Indigenous peoples, has rolled out numerous projects and initiatives that support both Guyana’s natural diversity and its people. Among the most impactful of these has been the Low Carbon Development Strategy (LCDS).

While large-scale projects like these ensure sustainability on the national stage, backed by international collaboration and scientific guidance, Chairman of the National Toshaos Council, Derrick John, reminds the world that the nation’s success is deeply rooted in shared stewardship between Indigenous communities and government leaders.

Speaking at a forum held in preparation for the highly

anticipated 30th United Nations Conference of Parties (COP30), John highlighted years of community-led forest protection and equitable development, urging continued unity and bold action ahead of COP30.

Indigenous Communities at the Forefront

The relationship between Guyanese leaders and Indigenous peoples has been impactful and, according to John, stems from a long-standing partnership. While the relationship existed for years, John stated that it was in 2008 when the voices of Indigenous people were formally recognised in the landscape of natural conservation and sustainability. This eventually paved the way for the 2009 Guyana–Norway Agreement on Climate and Forest Partnership.

Derrick John, Chairman of the National Toshaos Council, speaks at a forum ahead of COP30 (Japheth Savory photo)

John says Indigenous people have always been among the loudest voices in that fight.

“Guyana has always lobbied for the world to recognise the importance of our forests on the global stage.

With the leadership that our country has always had, we were taken seriously.

But all of this work can only happen by recognising the role of every stakeholder in Guyana.”

Highlighting the importance of the Indigenous voice, John added, “Indigenous people have always been in that conversation. I must make it very clear that we were always given a seat at the table. We are members of the multi-stakeholder committee.”

the rest of the world is recognising the role of Indigenous people—not only in conservation but also in national strategy and policymaking.

“Many times, when I travel, people ask why Guyana is being recognised. I always say it’s a very simple method: it’s because everyone in Guyana respects each other. Government respects Indigenous people; Indigenous people respect other stakeholders. We live by our motto: One People, One Nation, One Destiny. That’s something very unique across the world. I’ve listened to sad stories from other Indigenous groups globally, and it’s heartbreaking to hear that their voices are not recognised at the national level. It’s very different in Guyana.”

“Indigenous people have always recognised the importance of nature. It’s part of our life. For centuries, our ancestors have done an outstanding job in preserving our forests,” he said. “In 2009, when Guyana signed the first bilateral agreement with Norway, Indigenous people received their first financial support from the government.

development plan, and we were given five million Guyana dollars for that project.”

We were asked to develop what we called a community

Since then, heads of state, various ministries, and both private and public entities have joined the conservation and sustainability efforts, and

The voice of the nation’s Indigenous people, though seemingly small, has played a major role in the success of countless sustainability initiatives in Guyana. As John described it, their traditional knowledge has been integrated into the national strategy.

Because of this, John says,

The LCDS and Equitable Development

Presently, various Indigenous communities are benefitting from carbon financing, with money distributed equitably among the 242

TURN TO PAGE XIV

By Michel Outridge

AT just 29 years old, Alameen Hussain of Good Hope, East Bank Essequibo, has distinguished himself as one of Region Three’s most dynamic young livestock farmers.

Raised in a family of small ruminant farmers, Hussain developed an early passion for animal husbandry—one that has since evolved into a thriving and competitive sheep-rearing enterprise built on careful breed selection, innovation, and resilience.

Growing up, Hussain spent his afternoons assisting his father with the family’s poultry and small livestock, primarily turkeys and chickens. His own journey began when he was gifted two goats, but after challenges with their aggressive nature and neighbour complaints, he decided to shift to sheep rearing in 2012—a decision that transformed his livelihood.

“Sheep are easier to manage than goats,” Hussain explained. “I started with seven—a mix of Blackbelly and Texana breeds—and with the right care, that small flock grew into something much larger.”

Hussain’s decision to work with mixed breeds was

a deliberate strategy to meet diverse market demands. The Blackbelly breed, known for its hardiness and adaptability, forms the foundation of his flock, while the Dorper breed was introduced for its superior meat quality and faster growth rate. The Texana and other purebred lines, meanwhile, are raised for breeding purposes and sold to other farmers seeking to improve their stock.

“The market demands variety,” Hussain noted. “Some butchers prefer the Dorper for its meat yield, while other farmers look for purebreds or crosses with specific traits. Having mixed breeds allows me to serve multiple markets—from breeding stock to meat production—which makes the business more sustainable and profitable.”

With sound breeding practices and strict record-keeping, Hussain has steadily expanded his flock from just a few animals to over 200 sheep, emphasising both genetic improvement and disease prevention. His management strategy includes maintaining five different breeding rams, ensuring no inbreeding occurs, and practising rotational breeding to sustain the genetic health of his animals.

Hussain credits much of

his early success to the Guyana Livestock Development Authority (GLDA) and to Dr Praimnauth Tihul, GLDA’s Deputy Chief Executive Officer and former Regional Coordinator for Region Three.

“I am thankful for the support of Dr Tihul during the initial phases of my sheep farm development,” he said. “He helped me improve my flock’s health, manage foot rot, and understand nutrition. His guidance laid the foundation for the farm I have today.”

In addition to his work as a part-time mechanic, Hussain dedicates significant time to improving the productivity and welfare of his animals. His sheep are grass-fed for at least two hours daily and supplemented with pre-mixed feeds from Bounty Farm Ltd., along with molasses-enriched water, to maintain top condition.

His commitment to excellence was recently recognised when he won first place for Region Three at the National Small Ruminant Show at Rising Sun Turf Club, Weldaad. His winning entry—a massive Texana ram—was selected for its impressive structure and condition.

“I only learned about the show two weeks before,”

Alameen Hussain with his trophy, at the Small Ruminant Show he recalled, “but my animals were always in excellent shape because of proper nutrition and management.

Winning was a proud moment for me and my family.”

Reflecting on his journey, Hussain emphasised that sheep farming is both rewarding and demanding.

“Sheep rearing is profitable once you know what you’re doing,” he said. “It doesn’t happen overnight, and there will be challenges, but you can’t let losses discourage you.”

As a young farmer, Hussain is optimistic about the future of Guyana's ruminant industry. He praised the government’s enabling policies, the Ministry of Agriculture’s support through GLDA, and the visionary leadership of Hon. Zulfikar Mustapha, Minister of Agriculture, alongside GLDA’s CEO, Dr Dwight Walrond, Dr Praimnauth Tihul, and Region Three’s strong extension team led by Dr Narine.

“These gentlemen are helping to build the industry, but as farmers, we also have

to play our part,” he emphasised. “The government’s public-private partnership strategy is an excellent one— it gives farmers flexibility, access to improved breeds, and better opportunities to grow.

With this kind of collaboration, I believe Region Three can become the small ruminant capital of Guyana.”

For Hussain, the journey from tending chickens as a child to becoming a champion sheep breeder reflects the power of persistence, technical guidance, and vision.

“The future of small ruminant farming in Guyana is bright,” he concluded.

“With the continued support of GLDA and strong leadership at the national level, young farmers like me can transform traditional livestock rearing into thriving, modern agribusinesses that support food security and rural development.”

By Michel Outridge

AT just 30 years old, Sunil Balkaran of Wash Clothes, Mahaicony, East Coast Demerara, has emerged as one of the Guyana Livestock Development Authority’s (GLDA) most dynamic and forward-thinking professionals. As a Senior Livestock Extension Officer, he plays a pivotal role in the management of large ruminants—both dairy and beef—and continues to inspire a new generation of farmers through his leadership, innovation, and passion for agricultural development.

Early Roots and Academic Excellence

Balkaran’s story is rooted in the rich agricultural traditions of Mahaicony “Branch

Road”, where his family’s farm shaped both his character and career path. Growing up under his father's guidance—a farmer with over 30 years of experience—he learned the fundamentals of animal husbandry at an early age.

“We always had goats and cows,” he recalled. “My father taught me everything, from deworming and branding to administering medication when the animals were sick. Only in serious cases would a vet be called.”

A disciplined and determined student, Balkaran graduated as the Valedictorian of Mahaicony Secondary School, earning strong grades in ten CSEC subjects. Although he initially dreamed of becoming a cardiologist, fate had other plans.

During a casual visit to

his sister-in-law’s home, he came across a newspaper advertisement announcing a call for applications for government scholarships to study abroad. “It was the last day for submissions,” he recalled.

“I sent in my grades immediately without even attaching the certificates.”

A few days later, he received a call requesting proof of his results, and a month later, his application was approved. Balkaran was headed to Kuban State Agrarian University in Krasnodar, Russia, to pursue a five-year degree in Zoo Technology, Management, and Veterinary Science—a life-changing opportunity that solidified his future in animal science and agriculture.

The Road Back Home and Professional Growth

Upon completing his studies, Balkaran returned to Guyana in 2019 with renewed purpose. He joined GLDA on October 1, 2019, and was assigned to the large ruminant division. “When I joined, I was told the livestock sector was facing challenges,” he said. “But I’ve always been someone who embraces challenges.”

One of his early and most successful initiatives involved working with Mohan Singh, a dairy farmer in Mahaicony who owned 20 cows producing about 10 gallons of milk daily. Recognising the potential for increased productivity, Balkaran introduced Singh to GLDA’s Artificial Insemination (AI) Programme, which led to a genetic upgrade of the herd. Within months, milk production doubled.

This presented a new opportunity: value addition. Drawing inspiration from his visit to the St Stanislaus College Farm, Balkaran suggested producing paneer (a soft cheese) from the sur-

Ebony McKenzie and Latoya Harte lend support to farmers on the ground

plus milk. Singh adopted the idea, using biogas to process the product sustainably and economically. “The project was a major success,” Balkaran shared proudly.

“Today, paneer from Singh’s farm is available in local shops and supermarkets. It’s a true model of innovation at the community level.”

Leadership, Trust and Youth Empowerment

For Balkaran, leadership in the agricultural sector is not only about science and productivity—it’s about

trust, collaboration, and empowerment. “I’m thankful for the opportunity to lead and support the livestock sector in Guyana,” he said. “I am grateful for the confidence my boss, Dr Walrond, GLDA’s Chief Executive Officer, has placed in my ability—but most importantly, I’m thankful to the farmers and other stakeholders. For me, trust is very important.” Among his proudest professional experiences was serving as Coordinator of the GLDA’s Ruminant Expo TURN TO PAGE XXII

IN A Productive Garden, Geary Reid provides an indepth look at methods for planting, maintaining, and harvesting a garden. This quick, easy-to-read guidebook examines how plants grow and how you, as a gardener, can help them. Reid touches on issues that might affect your plants, including the environment, soil quality and type, weather, soil erosion, and pests. Drawing on his background in agricultural science, Reid provides helpful tips on proper irrigation practices, weeding, harvesting, and marketing your produce, as well as how to protect the environment while gardening. A Productive Garden is an essential guide to cultivating a healthy garden that you will reap the benefits of for years to come.

1. Gardening will involve hard work

Gardening may involve hard work, but it also has many benefits. For some, farming is seen to include both small- and large-scale cultivation. In this literature, however, the word “gardening” is used only to describe small-scale farming. The terms gardening and agriculture are often used interchangeably.

2. Consider the soil

The soil plays a crucial role in plant growth. Some plants can survive without soil, but generally, plants need some form of medium for support. Soil helps the plant in many ways. Some people choose to purchase soil at varying costs because they want a specific type that can benefit their plants. If the soil is nutritious, it can help make the garden productive. People may purchase good seeds, but if the soil lacks nutrients or is not supplemented with something that boosts its health, then the plant may not thrive. Having healthy soil is a good starting point for anyone who wants to have a garden.

Not all plants can manage rocky soil. In areas with mountains, you may see some vegetation, but in softer soils, there may be more plants growing. Many planters prefer to work with softer soils for cultivating various plants. While there may be soft soil, some gardeners may choose not to cultivate it if the level of investment is high and the returns are not guaranteed or significant.

A farmer can choose seeds for ornamental plants (for beautification) or for plants that produce outputs used by many people for

consumption, health, or production.

Therefore, if a person wants their surroundings to look beautiful, they should choose flower plants.

However, some will be interested in the commercial aspect of gardening and will select seeds that produce plants with outputs that can be sold.

In some yards, many plants are used for beautification. These plants often create a relaxing atmosphere for the owner or visitors. While artificial plants can make a place look good, live flower plants often evoke a different feeling for many people.

A farmer may not be able to sow seeds directly into their permanent locations at the beginning.

Some seeds may be too small to be planted directly in permanent soil and must first be placed in boxes or other containers for germination. Once those seeds or other plants are mature enough, they can be transplanted into the designated areas.

Some examples of seeds that are placed in a nursery for germination and then transplanted include pepper, tomato, and mustard.

Once the plant is in its permanent position or temporary location, water will be crucial for its future.

Some plants require a lot of water throughout their life, while others may only need water occasionally. Water helps plants in many ways. As mentioned, the roots help move water to different parts of the plant.

Plants in the desert are accustomed to small portions of water—it may rain only rarely. Most desert plants know how to store the water available to them.

Both water and other minerals needed by plants travel through their cells. These cells are distributed throughout the plant, and each plant can move water and minerals independently, without human assistance. Therefore, once there is sufficient water surrounding the plant, it can absorb various minerals and water on its own.

The sun does not always have to be very hot for plants to survive. Too much sun and insufficient rain can be detrimental to certain plants.

Farmers may build a shade for the plants, but they will construct it so the plants

still receive some sunlight. With a roof over the plants, the sun will still penetrate the shade, allowing them to continue growing.

At different times of the year, the sun’s rising and setting times will vary. Farmers may be aware of these times and plan their activities accordingly.

6. Manure

The food that the plant needs to consume will be provided mainly through manure. Manure and fertiliser are sometimes used interchangeably, as they both add nutrients to plants.

When farmers rely on organic manure, they reduce their expenditure, or in other words, save money. Most farmers aim to keep costs as low as possible while maintaining great output.

Some customers are only interested in purchasing agricultural products that are free from additives. They often say they would like to live longer and prefer not to have chemicals in their diet. The prices paid for organically grown products can sometimes be higher than those of plants grown with inorganic manure.

7. Insects

While farmers plan their

work to have a productive garden, others see the garden as their habitat. It is often challenging to have two owners in one house! Some inhabitants may make a valuable contribution, while others simply occupy without contributing.

Insects can be good or harmful. Most gardeners will be happiest to have good insects.

However, such wishes are not always granted—some creatures will contribute positively to the environment, while others will not.

8. Weeds

As with pests and pesticides, it is important to assess weeds and their control methods.

Once weeds are on the farm, the farmer must arrange for some to be eradicated. If farmers fail to address weeds, they can harm the farm, and all the investment made by the farmer will be wasted.

For more information:

Author: Geary Reid Amazon: amazon.com/ author/gearyreid Website: www.reidnlearn.com

Facebook: Reid n Learn Email: info@reidnlearn.com Mobile: +592-645-2240

don’t know where is the rest day. I work each and every day, Sunday to Sunday. Whenever I’m at home, I just focus on my farm because I love farm work. My day is just farming every day. Every day, Sunday to Sunday, I don’t get rest day.”

He added, “Every day, since I wake up, say my prayer, I play music and then

farm. You come or you call, I get in the farm. Whether snake in the farm, me don’t frighten anything. I pick them up, throw them away, I don’t get angry. Because I love farm work.” Justin’s love for his farm inspired him to join the community’s farmers’ association. As vice-chairman of the association, he is just one of many farmers

in the community working together to solve their issues.

“In the farmers’ association, I’m the vice-chairman for it. We get two times every second Wednesday or second Thursday we get a meeting. And we keep the meeting concerning how we’re going to get on with farm and if they have any issues, we try to solve it and so on. This

area has a lot of farmers and we have a lot of eddoe farmers too,” he shared. Agriculture for Justin is more than a job or a means to an end; it is a passionate pursuit to grow quality crops and deliver them to Guyanese homes. But it is also a business. Speaking to other farmers, Justin says the commercial side of farming

is often overlooked but is crucial to success, no matter the scale. “For me to advise farmers across the region in Guyana you got to be sustainable. You got to be consistent. You can’t want to pull $50,000 produce and spend $200,000. It’s not profitable. You cannot make it in farming. You have to decide in your mind what’s going to be

beneficial to you. This farm here, if I put $10 and produce $20, and I put back $20 and produce $80, the farm is going to grow.” For Justin, farming is a lifelong commitment, a labour of love that connects him to his roots, his community, and the land he has nurtured for more than three decades.

MY experiences as a young woman have always been filled with fear and anxiety when it comes to the night. In fact, when I speak to many women, nightfall and womanhood seem constantly at odds. We are fearful of the night, and our Guyanese culture further compounds that fear.

From an early age, Guyanese parents often reinforce the belief that “girl children should not walk late.” It simply means that girls ought

to be indoors before the sun sets.

The older I get, the more stories I hear of women being harassed, harmed, threatened, or worse—having their lives taken at night. I came across the concept of “reclaiming the night” after a conversation with a professor in the United Kingdom. She explained that she once helped to organise such a march for women on her university campus after many complained about feeling unsafe

while walking there at night. She said they all marched around the campus holding hands, and it was such an empowering experience for all the women present. With a sense of community, they were able to “reclaim the night,” and at the same time, they carried posters and flyers encouraging men to leave women alone as they walked during the evenings. Have you ever considered that women have to plan an entire routine if they need to

venture out in the evenings? If some women need an item from the store, they either hurry to get it before it’s “too late” or ask a male partner or friend to assist. I vividly recall my experience attending university and having late-night classes. My father would wait for me on the roadway to walk with me into our street. He did this to deter men from taunting me as I walked.

For some women, the night is far more dangerous

more seriously. You can have fun—nobody’s stopping you—but life is not going to wait on you. You’ve got to get up and get what you need. That’s what I believe.”

For Radha, the market is more than a place to sell pumpkins, plantains, and watermelons. It is a space to grow, test limits, learn, and carry forward a family legacy. “I’ve seen my grandfather do this job for so many years, and after I got into it, I could really understand what he meant. Agriculture teaches you life from a different perspective. It’s not just about the corporate world where you just do your work and that’s it. Agriculture requires you to be active all the time. Your mind has to be straight and sharp,” she said.

As Guyana celebrates Agriculture Month, Radha extends her wishes and hopes her story will inspire others to explore the opportunities and lessons that market life offers. “I’d just like to say a very happy Agriculture Month, and I encourage more people in my generation to get active in agriculture because it can really change your life.

You need to learn and have different experiences in life. You’ll see something else that you never thought you’d see, and not the way you would see it in the corporate world. This here, on the market, is something else.”

FROM PAGE III

in their communities—beyond taunting and teasing.

In fact, the “Reclaim the Night” movement originated in the United Kingdom in the 1970s. In the city of Leeds, women launched the movement after a rogue serial killer murdered and attempted to murder many women in the area during the night. Women were terrified to walk the streets. As such, this movement was started to empower women to take back control of their routines and their right to traverse the streets at night.

Over the years, the movement has crossed borders, and many women across the world now host marches and demonstrations on “reclaiming the night” in their own communities. I am writing this column in the hope of inspiring women in Guyana to understand that we, too, are entitled to the freedom of evenings and nightfall. We should walk our streets, no matter the time of day, without worry or fear.

I encourage you all to

challenge your internal belief systems.

When we see news headlines of women being tormented on the streets at night, many often say, “She should’ve stayed home,” or “What is she doing out so late?” But how often do we turn our attention to the perpetrators and how they use the night to their advantage to prey on women? These reflections can help us all collectively understand why it is important for women to reclaim the night.

It is more than just the time of day, the darkness of the nights, and the ability to walk when we feel like it—it’s about reclaiming our power and fighting for our human rights. So many terrible things have happened to so many women in the evenings, on our streets, and in our communities—it’s about time we say enough is enough. No matter where we go, what we do, or what we wear, yes means yes and no means no. The night belongs to us too.

AS a child, I was introduced to the beliefs that enveloped the world of the last days of British Guiana and early Guyana.

Story time occurred occasionally in my father’s workshop up the coast, with his friends like Uncle Mosche, the masquerade band flautist, who had an archive of explanations concerning the masquerade band. He urged me that until my maturity— marked by becoming a father—my first honour would be to keep secret what I was told. But that was on the East Coast.

Years later, I had filed away most of what I had learnt then, not knowing that I would one day witness, for the first time, an incident that had only ever been described to me in gyaff. In West Ruimveldt, where I lived, a younger brother was standing next to me as drums beat in front of our range.

Suddenly, he did a somersault and, supported by his arms, began dancing upside down; at one point, he was balancing on his head. It was incredible.

Someone came back from the group that had left hur-

riedly. We all had names for what was happening, but couldn’t do anything to change it. The ‘Front Road’ didn’t have all that housing back then. The dark trench water kind of awakened him, but the brother couldn’t recall anything afterwards. We were just glad he was still with us.

A few years ago, I bought and read a book titled, The Jumbies’ Playing Ground, by Robert Wyndham, which focused on Afro-Creole masquerades in the Eastern Caribbean. I then realised that our masquerades had a different root from those in

that part of the Caribbean. Though we had adopted some colonial instrumentation, there were still unique elements that were ours.

A. J. Seymour had published a book in 1975 titled, Dictionary of Guyanese Folklore (and please don’t ask me—I’m not lending any of my country folk a book).

My late great-aunt told me about the declaration of Cumfa, a festival common to Charlestown, Albouystown and La Penitence, in honour of King O’ Cumfa of the Congo. In the 1930s, those days when the Sussex Street

trench was black water, many mysteries would emerge, though not without symbolic meaning.

I can well recall meeting the late illustrator Seymour. I had questioned him about the character ‘Big Mama’ and why he had demonised her. He explained that he wouldn’t have been able to get published otherwise, since the Church held great influence and could suppress anything it disliked. It must have been difficult back then. Today, it isn’t smooth running either; the arts’ potential still seems not quite

understood.

But everything can be comprehended if the people involved are allowed to ask and answer a few questions themselves.

We may, in conclusion, try to avoid the predicament of our CARICOM zone, as cited in Al Creighton’s June 20, 2021 interview with Harold Bascom, The Impoverishment of Caribbean Writers and Creative Souls. My addition, in closing, is that creative folk have a clear perspective of the bridge before us. We’ve already paid the troll’s fee.

SHE was born on a Tuesday morning in late February, when it was still dark, in a play park in a residential area. Someone had forgotten to close the gate that night, and the pregnant mare wandering the streets found a clean and safe area to bring her baby into the world.

The next morning, when it became light, residents were thrilled to see a newborn foal wobbling on its legs as it tried to get its balance. Animals were not allowed in the field because it was newly upgraded— hence the gates—but the mother and baby were allowed to stay until she was ready to leave. Later that day, the mother was leaving with her baby, but unfortunately, it fell into the drain just inside the fence.

I had just looked out to see how they were doing and saw the mother standing by the fence inside the field, looking concerned. Upon checking, I saw the baby foal stuck in the drain. No one was around to assist, so I knelt down and put my arms around the baby’s waist to pull it out. I fell back a little, so I had to hold it against my chest. Then it jumped away and ran shakily back into the field. I had mud all over

me, but I was happy to have saved it from further peril.

At that moment, I made an onthe-spot decision to close the gates to keep the mother and baby in the field a little longer, to prevent them from walking out and falling into another drain.

Someone else might not have seen it in time to save it, and that could have meant hours of suffering in the water. We had already had two newborn foals die in that way, and both are buried right there in the playfield. I didn’t want another death, especially after being

involved in rescuing the first two.

One resident joked, “It seems to be a calling for you to rescue these babies.” Maybe it is—but as an animal lover, I know that I have the instinct to help any animal in distress once I’m nearby.

It’s a sad situation that these

adult horses are neglected by their owners—perhaps because they are no longer useful.

They are left to roam the streets in the harsh sun and heavy rain, looking for grazing areas and scavenging in garbage bins. They often come into the community to graze on the fresh, green grass on the wide parapets—sometimes injured and looking quite forlorn.

The experience I had with the first foal, trying along with a few other residents to save its life, left a deep impact on me. For two days, we did our best to help it survive, and the mother stood protectively over her baby from the evening we left it under a shelter. The next morning, when I checked if its condition had improved, its body was stiff and cold. It had died during the night, but the mother still stood there, protectively over it.

Later that day, as a grave was dug to bury the baby foal, I sat and witnessed the mother’s deep anguish and reluctance to leave her baby. Animals and humans are no different when it comes to love, pain, and grief, yet animals are often mistreated by humans. It touched

TURN TO PAGE XX

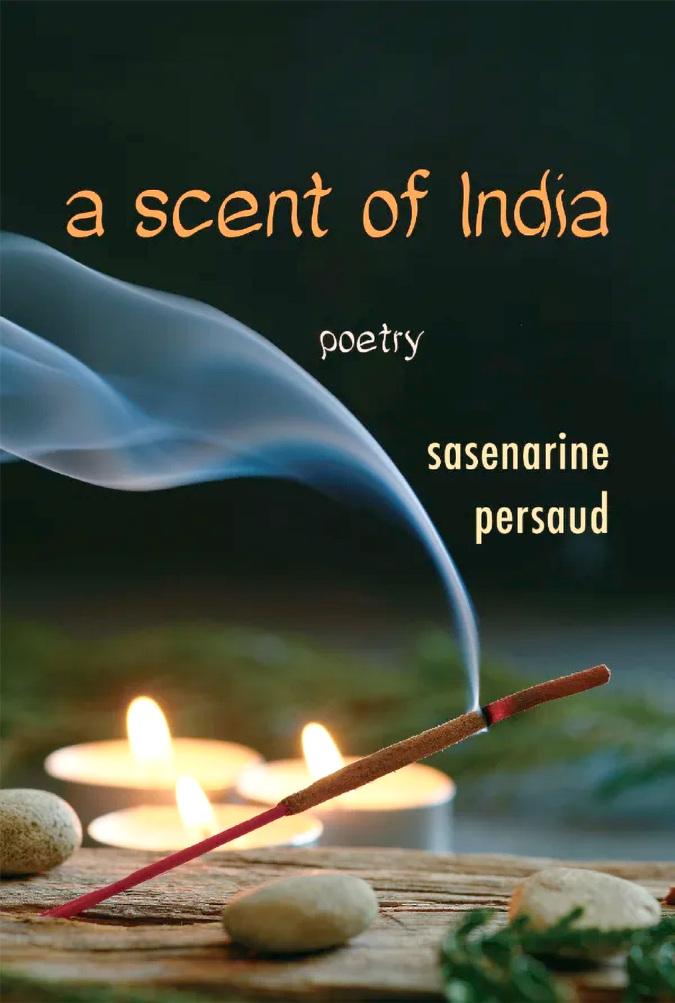

A POEM can dignify even the crudest thing—redeeming it from anonymity or disgrace, and elevating it to something strange, memorable, and profound. This transformative alchemy is often at work in the poetry of Sasenarine Persaud, the prolific and perceptive Guyanese-Canadian-America n poet. Persaud’s vision is panoramic; whatever crosses his retina often finds its way into verse.

Think of his poems as a drag seine: they trawl through oceans, seas, and rivers—and what they haul in is wild, diverse, and often surprising. The metaphorical net catches everything, including, as the old saying goes, the kitchen sink.

This democratic inclusivity of content—where even the trivial or overlooked becomes central—is also found in the works of literary giants like Walt Whitman and Kamau Brathwaite. In such poets, the seemingly insignificant is not mere scaffolding but structure—the very fabric of the poem itself. These “kitchen sink” poems brim with so much that there’s something in them to please, challenge, or provoke every reader.

One of Persaud’s most striking poetic modes is the travelogue. These poems feature a wandering, curious persona who observes, reflects, and philosophises—often simultaneously.

The poems ebb like tides, carrying the poet’s thoughts as they brush against, cling to, and interrogate the world around them.

Take Patches, the opening poem in Persaud’s new collection A Scent of India (MaWenzi House, $20.95).

The poem juxtaposes two spaces: poverty as want and wealth as waste. In the latter, we find “McMansions” with “bedrooms for guests who never come”—symbols of excess and hollow affluence. The former is one of patched clothing and scarcity—going without even a buckta (Guyanese Creole for male underwear). Clothing is cobbled together from remnants, from the patches of what once was whole.

This contrast is stark, and Persaud handles it with a deft touch, connecting material realities with quiet emotional resonance. The movement of thought in the poem is subtle, like a marble rolling along an uneven floor—never still,

always suggestive.

Wearing khaki shorts without buckta

The firm rub of hard cotton

Handstitched from inseam, indigo

Denim scraps gathered from a worn Shirt’s least jaded areas— what

Do you mean thimbles from Hollywood Or Pinewood—just having needle

And thread enough—we asked for little

You who would scorn our memories

Mistaking blog’s history for nostalgia

Celebrating our cloud in computing

Cryptocurrencies, wallow in ancient

Bigbellied Buddhas better Ganesh’s

Sisters see blue patches from a distance

On our separate bridges than our bottoms

Bare skin, unshod toes navigating

Pebbles on unpaved Dennis Street—we

Will rename that too, slaveholder, Amerindian landgrabber, misogynist,

Ant-trampler, carnivore, meateater, Orsomethingnowoffensivedoer—to Rangilia’s store for jil-

There is a poetic quality in Persaud’s work that echoes John Ashbery—particularly in the way his poems mean-

der away from a central idea, exploring tangents before circling back, much like a jazz solo that improvises before returning to the melody. In Patches, these digressions are often allusive, drawing on references to Indian mythological figures that lend the poem layers of meaning and cultural resonance. Ultimately, however, the poem returns to the literal—to the unambiguous terrain of lived experience.

The title A Scent of India hints at more than it states. The collection isn’t explicitly or solely about India. Instead, India becomes a kind of atmospheric presence—a way of seeing, sensing, and remembering.

It permeates the poems not only through history and culture but through the legacy of its exports: people, food, language, religion, art, and politics.

India, in Persaud’s poetry, is not geographically bound. It lives in Guyana, the poet’s birthplace, where its influence is unmistakable. It persists in Canada and the United States, where Persaud has lived for decades. In this sense, the collection’s title is TURN TO PAGE XXI

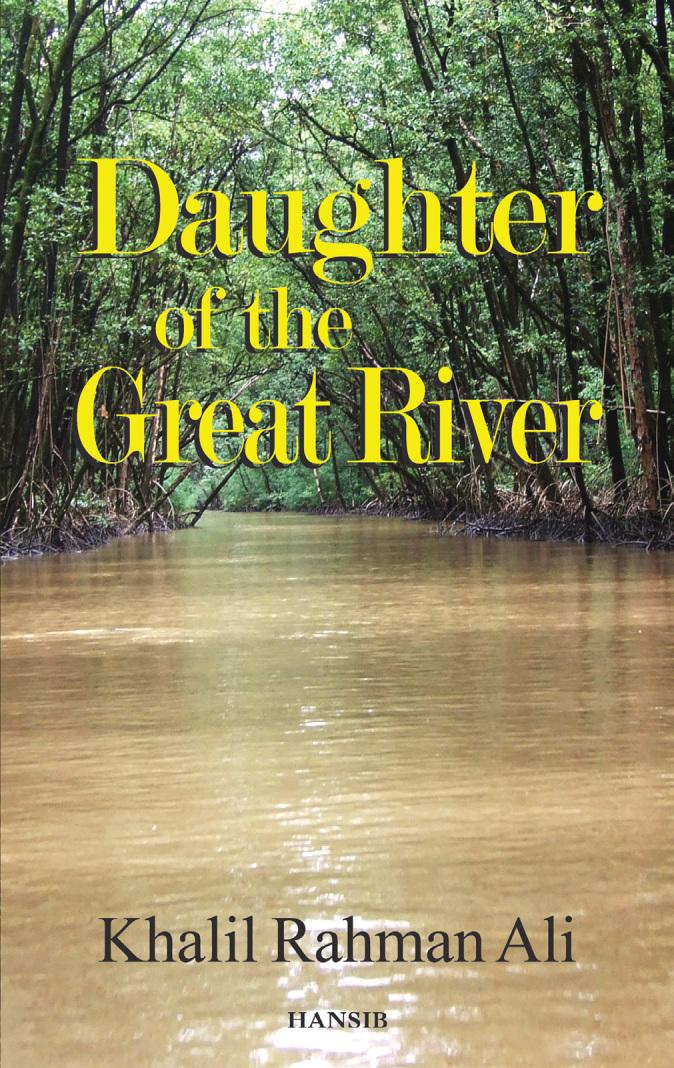

THE world stood still as the midnight hour of a new millennium approached. Preparations had been completed by billions of people in every corner of the planet as the first second of the new year 2000 was awaited with bated breath. Elaborate and costly plans were in place to manage the uncertainty of computer and other systems moving from the end of the year 1999 to the beginning of 2000.

Deep in the rainforest that made up most of the land of Kayana, in the north of South America, all the members of a small settlement of the Kayanese tribe of Indigenous Peoples also sat silently and patiently around the outside of the benab, or big house. They were awaiting the arrival of a special baby whom they believed to be the chosen one to save them, the rainforest, Kayana, and the world. This was far more important to the residents than the anxieties of a changeover of computer systems from 1999 to 2000.

The settlement, situated

deep in the lush green rainforest of Kayana, known as The Land of Many Waters, was not easily accessible to others, except for the members of the twohundred-strong, resilient, and resourceful tribe. The site was carefully chosen by their Chief, or Cacique, over five hundred years prior—just off the tributary of the longest river, known as the Great River of Kayana. He, along with a handful of men, women, and children, had escaped from further northwards of the country due to brutal persecution by invading Europeans.

The life-giving tributary was about two hundred yards wide at its mouth and cut through the vegetation on both banks, narrowing to only a few yards wide further and higher into the rainforest. This allowed ideal protection for the settlement. It also offered a variety of fish, shrimps, and crabs, which had always been a main source of food for the families.

The dark brown water flowed steadily through, with

small ripples lapping against the grey, muddied banks. The first inhabitants who found and set up the settlement had cut a narrow path through the vegetation into the large opening where their huts were built in a great circle around one central structure called the benab.

The benab was circular in design and built upon strong timber legs which supported the roof made of leaves and vines. It served as a communal resting and meeting place. A carefully cleared and maintained bare-earth area in front of the benab was specially set out for celebratory dances, games, and day-to-day gatherings.

The population of the settlement had managed to grow and survive over the centuries through the successive Chiefs’ astute guidance and avoidance of contact with strangers, including members of other Indigenous tribes. Skills for hunting and physical self-defence were taught and handed down to the young over time. The older women taught young girls essential weaving skills,

cooking, and general housekeeping, as well as the strenuous lifting and carrying of baskets of cassava, their main ground provision.

The people’s watchful and protective approach had provided them with security over the centuries, until a more recent contact with strangers caused the outbreak of a severe incidence of pneumonia which almost decimated the entire population. However, over the last thirty years, the community had managed to rebuild itself and had tried to adapt to its new situation.

The entire community initially sat quietly on their haunches outside the benab, as the oldest female member—who would become the baby’s great-grandmother— offered traditional prayers throughout the labour. No men were allowed in or near the birthplace, and they joined the gathering outside in a separate group.

The expectant mother was only eighteen years old and had endured a very difficult first pregnancy. How TURN TO PAGE XX

communities, according to John. Under the LCDS, now in its 2030 phase, Guyana receives carbon credit payments for keeping its forests intact, and a significant share of that revenue is directed to Indigenous communities.

Even the distribution of funds among communities was strategic, John says, with various steps ensuring the best allocation across Guyana, whether titled or untitled, taking into account factors such as population, landmass, and location. “We looked at a model most suitable for Indigenous people. Some communities have very

small populations but huge land masses, so the focus was people-centred,” he explained.

“There are also communities that do not yet have rights to their lands. We had to take that into consideration; they still need to benefit. Some communities have forests, and some do not, but it’s a really good model. I’m proud to say that over the years, Guyana has developed a model where all Indigenous communities benefit, whether you have titled lands or forests.”

While the project continues to grow, garner interna-

tional attention, and become a model of sustainability, John says the LCDS has already had a massive positive impact on the lives of thousands of Guyanese.

“From the funds being distributed, we have seen massive transformation taking place. Lives are being improved, there are more job opportunities for local people, especially women and young people. Communities are investing their funds and doing more to protect the forests.”

One of the sectors seeing significant investment and growth has been eco-tourism,

with communities highlighting Guyana’s natural beauty while keeping conservation at the forefront.

“One of the big investments has been introducing eco-tourism, which is very important for us. We don’t have beautiful beaches like the Caribbean, but what we do have is nature, and it plays an important role in keeping our environment stable, maintaining temperature, and sustaining the global atmosphere so that we can all survive as human beings. Without our forests, it would be a catastrophe. The forest is like the lung of the earth,

and people want to come to experience life with nature.”

Development has not stopped at eco-tourism.

Across the hinterland, communities are building eco-lodges, promoting ecotours, and revitalising traditional practices. “Communities have developed eco-lodges and other activities that promote eco-tourism. They have also invested in food security to become self-sufficient at the community level, introducing poultry rearing and expanding farming.

Some are using the funds to revive their languages and traditional knowledge, which

have been in gradual decline. There’s a vast amount of change happening across different sectors in our communities,” he said.

Pointing to examples of exceptional leadership within communities, John added, “This is very important for us. We’ve seen communities recognising the need to do more, and I must commend the communities in Region Nine Deep South, who have pledged some of their resources to protect biodiversity. That’s a big step, a worthwhile investment I hope other communities will follow.”

As the world prepares for COP30 in Brazil next year, John said Guyana must carry forward its message of partnership and respect. “We always recognise nature-based solutions as very important, but at the same time we must be able to access funding that is critical for Indigenous people. Guyana has to be proud. We, as a people, have to be proud.”

He further emphasised, “As we head to COP30, I want us to keep the momentum. Let us go to COP30 with one voice so that we can influence the big countries. We hope to move from promises to actions, that’s very critical. We have not been seeing the results from all these past COPs. There have been many promises, but we need to move forward and start implementing.”

THERE is a constant, quiet whisper that resides within each one of us. The whisper is a heartbeat that paints every breath we take. It hides itself amidst the noise of daylight. In the night, however, when the world is quiet, we hear it clearly in our ears—like the laughter of a river. They are the unnamed thoughts that bind guilty willingness to involuntary errors.

They are the darkness so bitter that we cannot face them long enough to conceal them. So, instead, we pretend that they do not exist. We call these things desires, but this is a false name. In reality, they are called impulses.

Impulsiveness has gradually become one of the hallmarks of Generation Z. Our generation seems to be centred around speed, excitement, and immediate gratification. Life is an itch that must be scratched, and time is an obstacle meant to be survived.

Most of our technology and innovations are centred on saving us time—how to live longer, how to do tasks faster, or how to reach goals in smaller steps. These changes in our world have led to corresponding changes in our behaviour. We have become far more impulsive. Impulsiveness, of course, is a powerful force that can determine what kind of person we are.

This brings us to the question: what exactly differentiates a good person from a bad one?

Does having bad thoughts make us bad people? If so, this would mean that everyone who has been angry or upset is a bad person. Perhaps someone who does good things becomes a good person by virtue of their actions. But that too would not be acceptable—it would excuse every wrongdoer from the responsibility for their actions, as long as they did something good afterwards.

The truth is, human beings cannot be categorised as ‘good’ or ‘bad’. We are all made of good and bad parts. We have all done good things and had bad thoughts, or vice versa.

More importantly, regardless of what we have done or thought, we are capable of change.

This means that someone who may have made terrible choices in the past may now be a person who makes the right choices to help people and contribute to the world in a better way. A thief can become a philanthropist, and a liar can become an honest man—all through practice and time.

Our goodness lies in how we respond to the world as it carries us through life. Some of us are condemned to live more difficult lives than others. Yet, even as we

stand in the face of cruelty and injustice—even as we are hurt—we make the intentional choice not to lash out or cause harm. Our goodness is our ability to control the ‘bad’ impulses, even when it seems like the most difficult thing to do.

When we practise giving in to our impulses in seemingly harmless situations, we

unintentionally teach ourselves that impulsiveness is the normal way to approach life—that it is okay to hurt when we are hurt, and to destroy when parts of our own lives are destroyed.

Sometimes, our impulses become a mask that hides our true capabilities and powers. They can diminish the light of the good parts that we hold

in our hearts.

The only way to find freedom from our impulses is to practise it in our lives.

Try making choices that are not instantly gratifying, but instead contribute to a better life or a better world.

Try to make small sacrifices to achieve goals rather than taking shortcuts. If you see that a method can help you

learn more, even if it takes longer, choose it anyway.

There is great strength in someone who can be kind and gentle even when thrown into a brutal world. This strength is the material that will create a generation capable of building a magnificent legacy—even when it has been dealt a bad hand.

ever, upon advice from her grandmother, she was not taken from the settlement to receive more modern maternity care and support from the midwives and doctors stationed at the community hospital in a small town about thirty miles up the Great River. The old lady was particularly keen for the special baby to be born within the benab, in the presence of the tribe.

The sombre chanting continued in a mesmeric rhythm for several hours into the night, only pausing at the sound of agonising cries caused by the acute pain of labour. A local band of howler monkeys responded noisily upon hearing the cries of the mother-to-be, as if in empathy with her. Their calls carried higher and deeper into the surrounding forest. Their black coats made them difficult to spot high in the trees, until they leapt from branch to branch, aided by their strong arms, legs, and long tails.

Finally, at midnight, the young mother gave a sustained cry as the baby was born. A few moments of utter silence were then broken by the faint wail of the newborn. Then, as the weary onlookers began to stir, they were alarmed to hear the screams

of the women attending the birth.

The great-grandmother, who was just less than five feet tall, slowly stood up and cradled the baby, which was wrapped in a white cotton towel. Tears trickled down her wrinkled cheeks from her tired, reddened eyes as she tried to forge a smile. She stepped forward to the open entrance of the benab and stood at the top of the short stairway. The entire audience looked up with great joy at the new child of the millennium. They spontaneously raised their arms in prayer to welcome the promised chosen one and new Chief.

The old lady raised the bundle above her head as the baby began to cry.

She said, “Hail to our future Chief! Rise up to welcome our Onida, the Daughter of the Great River! Long live our chosen one!”

Everyone shouted, “Long live our Onida! Long live our Chief Koko!”

The howler monkeys screamed excitedly as their message rang out through the forest.

About the Author Khalil Rahman Ali is a successful author who was born in Guyana, South America, and has lived, studied,

and worked in London, England, since 1970. His first three historical fiction novels—Sugar’s Sweet Allure (2013), The Domino Masters of Demerara (2015), and In Pursuit of Betterment (2017)—are based on the experiences of the Indians who were indentured to work on sugar plantations between 1835 and 1920 in several countries around the world, including Guyana, Trinidad, Jamaica, Mauritius, Fiji, Réunion, Suriname, and South Africa, and their descendants who are part of the Indian diaspora.

Khalil has a keen interest in the environment, climate change, and the sustainability of the planet. He believes that the Indigenous Peoples of the world are best suited to help sustain and save the planet. This latest novel offers an insight into the problems and threats facing Indigenous Peoples living in the rainforests.

He is a keen traveller, loves sports, and is an accomplished Indian singer and musician. Khalil hopes that Daughter of the Great River will help to inspire individuals, communities, and governments around the world to work harder to save the planet.

my heart that afternoon to see that mother’s sorrow as she stood over her baby’s grave.

I didn’t want a repeat of that with the new baby, but little did I know that this would be a new experience. Another resident and I took water for the mother horse because the sun was scorching and there were no big trees for shade in the field. We kept watch on them as we refilled the water buckets. On the second day, we noticed the mother wasn’t allowing the baby to nurse.

The baby was beginning to look weak, and a vet was called. We stayed in the field until late evening, but he never showed.

On the third day, the baby had grown weaker as the mother continued to reject her. An idea came to me— perhaps we could feed her milk with a nursing bottle to ensure her survival. It worked. She drank the milk hungrily.

By that time, four vets had been called and none had arrived, but one explained by phone that the mother was suffering from depression,

thus her rejection of her baby.

It was amazing to know that animals experience the same postpartum depression as humans.

Word spread around the neighbourhood about the baby foal’s plight, and it was heartening to see how motherly care stepped up. By day four, five mothers had their own nursing bottles, and a feeding schedule had to be implemented.

I named her Bella, and two foreign diplomats’ wives named her Martha. She was so cute you couldn’t help but fall in love with her. By the end of the week, she had become everyone’s pet. The mother had to be let out to find fresh grass, and we thought she would return— but she didn’t. The baby began looking lonely except during feeding times, and I feared she might fall into depression without seeing her own kind.

We waited into the new week for the mother to return, but she never did, and I had to consider the next steps regarding Bella Martha’s in-

FROM PAGE XI

terest. None of us knew how to care for a horse as it grew, and we couldn’t depend on a vet to come in time should something go wrong. One of the foreign ladies suggested we keep her until she got older and then let her out—but we weren’t sure she’d be safe on the streets without her mother. She’d be exposed to the sun and rain, scavenging for food, and could be hit by a vehicle.

She was precious—our baby—and we all wanted her to have a good life, cared for and safe with vets on call. We finally found a place that was like a little paradise, suitable for our little princess. It grieved our hearts to let her go; the mothers who fed her were in tears, but it was in her best interest—for the streets are cruel.

The adoptive owners fell in love with her at first sight, and a special caretaker was assigned to her. We still receive updates and pictures to see how she’s growing. We helped her to survive, and she will continue to live in our hearts— our own Bella Martha.

both literal and metaphorical. The “scent” is everywhere: sometimes pungent, sometimes faint, but always present.

Even in a poem about the Holocaust—specifically Auschwitz—this transnational and transhistorical consciousness is present. In one devastating passage, the cataloguing of human remains evokes the industrial scale of brutality: 110,000 shoes / 3,800 suitcases, 470 prostheses, 88-pound eyeglasses, 500 acres, 155 buildings, 300 ruins.

This chilling arithmetic is not limited to the Holocaust. The poem extends the litany of suffering to include Russia in WWII, the Hindu-Muslim conflicts in India, China during Mao’s Long March, the Rwandan genocide, and the systematic destruction of Native peoples in the Americas. A single poetic thread here unravels a global tapestry of shared, recurrent violence.

Most of the poems in A Scent of India are short— between eight and eighteen lines. Many resemble extended sonnets in scope and density, though they forgo rhyme. They are enigmatic, elusive, and often epigrammatic—evoking feeling more than asserting meaning. The poems have the lapidary quality of finely cut gems. Poems like Empty House, Cleaning Up After, and Into October achieve a mysterious resonance. The ideas are clear but slippery, familiar yet resistant to easy interpretation.

There is a kind of poetic matati—a wringing-out process—at work here. Superfluity is purged. These are taut, compressed poems, eschewing conventional punctuation. There are no question marks, no periods—no terminal points. The poems resist closure; they linger

beyond the page, echoing in the reader’s mind. This technique compresses meaning, deepens density, and demands rereading. The effect is akin to navigating a poetic labyrinth: the reward for persistence is insight.

In this, Persaud’s collection echoes Wilson Harris’s Eternity to Season, both in form and in philosophical ambition.

In my review of Persaud’s earlier work, Mattress Makers, I noted the intrepidity of the narrators. That spirit continues here. The peripatetic voices in A Scent of India move constantly—like satellites, ever orbiting, ever recording. The locations are global:

• Picking mangoes and walking the streets of Kitty, Guyana

• Buying Indian street food in Couva, Trinidad

• Strolling beaches in San Salvador

• Wintering in Florida, missing the May/June rains of Guyana

• Observing the ruins of a concentration camp in Europe

The best poems in the collection evoke a deeply felt sense of place, refracted through the prism of India. In Doubles at Curepe Junction, Indian Belles at Sevilla House, Couva, and Rooster in Trinidad, we experience the India of Trinidad—its cultural residue made palpable:

Hands outstretched, supplicant at night for Indian manna in grease-proof paper

Hot channa curry on thin puris

Cupped in palm and medium hot

And again:

Nothing curried channa and leaf-thin puris

At Curepe Junction won’t cure. But whose hands

Stirred that karahi, whose palms guided belna

Whose eyes aflame mis-

used orifice, muscles

This is not nostalgia. It is invocation—of culture as lived, of history as embodied, of identity as hybrid and ongoing. The karahi and belna are not just kitchen implements—they are cultural relics. The raggas hummed while cooking become part of the poem’s ambient music.

A Scent of India is more than a fleeting perfume. It is history, mythology, food, and philosophy. It is the taste of masala—complex, lay -

ered, unforgettable. Whether you’re in Puerto Rico, Guyana, the United States, or elsewhere, Persaud’s poetry reminds us that the scent of India lingers—imprinted on the world and within us.

This collection is expansive, ambitious, and richly rewarding. It invites the reader not merely to observe but to engage—to taste, smell, and feel. In doing so, it dignifies the everyday, making it strange, new, and necessary.

2025, which he described as “one of the most inspirational and educational opportunities” of his career.

“The Expo showcased the immense potential of our livestock sector and brought together farmers, scientists, and young professionals in a way that truly reflected the future of agriculture in Guyana,” he said.

As a young livestock visionary, Balkaran is especially passionate about encouraging youth and women to view agriculture as a viable and rewarding career. “Traditionally, livestock was seen as a male-dominated field and a source of supplemental income for rural families,” he explained.

“But today, more females should embrace this industry—there are numerous opportunities. Young people, too, should use the available support to transform their traditional farms into successful business enterprises. The time is now, especially with the lucrative national policies supporting agricultural development, including access to financing and technological advancement.”

Recognising Dedication and Modernising Agriculture

Balkaran also took time to acknowledge the dedication of his colleagues, Ebony McKenzie and Latoya

PAGE VII

Harte, whom he described as “loyal and committed team members” of the livestock division. “I’ve seen them lift calves, work through the night, and go above and beyond to ensure animals’ survival. Their dedication and nurturing spirit are truly commendable.”

He also praised the GLDA and the Ministry of Agriculture for implementing programmes that have significantly advanced livestock production nationwide, including the Bull Rotation Programme, Artificial Insemination Services, and the Embryo Transfer Programme.

“GLDA is transforming the industry,” he said. “We’re helping farmers modernise, improve yields, and adopt sustainable practices. It’s fulfilling to see how far we’ve come, but there’s still much more to achieve.”

From a young boy tending goats and cows on his family’s farm to a national leader shaping Guyana’s livestock future, Sunil Balkaran’s journey embodies passion, perseverance, and purpose.

His story is a powerful reminder that agriculture—when infused with innovation, trust, and vision—can drive not only food security but also social and economic transformation for generations to come.

Welcome, dear reading friend. We mentioned ‘attention’ last time. Yes. But do you know that interest leads to attention? It does. Whatever is in your interest will gain your attention. Even during deep study at times, your attention can be distracted.

One method: suppress that interference. Keep working at a fair speed as you

switch from one useful point to another. Cease concentrating too long on one point! It sways your attention. Another method: keep connected with your study group. Be wise.

Love you.

Sentence fragments

A Written Sentence: There are many ideas about

the sentence that must be clarified first before getting into sentence fragments.

Reminder: a) A simple written sentence contains only one subject and only one verb (predicate), either of which can be compound.

A sentence can be considered a complete thought OR one main idea. If it is a complete thought, it must include contextual details to allow you, the reader, to understand better what is

being said.

October 26, 2025

A sentence must also have proper capalisation, grammar, and punctuation.

Reminder: b) The verb alone is called the simple predicate. The complete predicate consists of the verb plus all its modifiers or complements.

Example: The old man sang the beloved song of his ancestors.

The simple subject is “man”; the complete predicate is “sang”.

The complete predicate is “sang the beloved songs of his ancestors.”

The sense of ‘sentence’ (or sentence sense) exists mostly in written and formal speech. [Understand here that dialogue structures in story writing are governed by their individual forms of speech patterns and culture. We are not talking about any of that.]

A simple written sentence is also an independent clause. (The concept of ‘clause’ is already dealt with a short time back, but will be expanded further, if necessary, in later issues.) You will see why this is mentioned here and now.

1. A Written Sentence Fragment:

a) A group of words that fails to have the requirements clearly referred to above as a simple written sentence, is called a written sentence fragment. No matter if you, the writer, put a capital letter upon the first word, and an end stop after the last, the group of words is still a fragment.

b) If you read well, you will find that accomplished writers use fragments freely to make conversation sound natural. But that is all in the business of accomplished writing, and knowing when and how to use fragments as part of your style.

c) Test to Determine: A good test to determine whether a group of words is a sen-

The more things change, the more they are the same.

tence, or a sentence fragment, is to take the group by itself and read it aloud. If it seems to make an understandable statement, it is probably a sentence – containing a predicate, and a subject about which the predication is made.

2. Sentence Fragment Types:

a) There are many types of sentence fragments, but basically each fragment falls into one of the following classifications:

i) A group of words without a verb or predicate:

Example: The choir working hard to complete the thanksgiving songs.

ii) A group of words without a subject:

Example: Responded in few words.

iii) A group of words lacking both predicate and subject.

Example: Depending on the food and the door price.

iv) A group of words forming a dependent clause.

Example: After he finally reached his destination.

b) EXERCISE: Try to fit each of the five given below into one of the groups just mentioned above to flex your understanding of different types of sentence fragments.

i) A verbal phrase: to make red marble cake.

ii) A part of a compound predicate: and spoke to all the interested freshmen.

vi

iii) A prepositional phrase: At the beginning of the dreaded Language 3 course.

iv) A dependent clause: While they were making a thorough search.

3. Treatment of Sentence Fragments:

Sentence fragments can be properly treated. One way is to recognise what it is doing. And then, try to correct and restore it by adding the missing parts OR by attaching it to a main clause. (Expect more next week.)

THE PASSAGE

Reading Comprehension

Read the passage that follows and then respond to the questions that follow.