Sunday, November 09, 2025

GTA programmes are equipping a new generation of skilled professionals for a growing industry Building

Sunday, November 09, 2025

GTA programmes are equipping a new generation of skilled professionals for a growing industry Building

By Michel Outridge

AMIDST the evolving landscape of D’Edward Village, West Coast Berbice — where commercial activities and modern housing developments are reshaping the once-agricultural community — one man continues to uphold the village’s proud tradition of livestock rearing and fresh cow’s milk production.

That man is Dennis Thomas, a 67-year-old farmer whose unwavering dedication to animal husbandry has earned him the respect of his peers and the gratitude of his community.

A proud son of D’Edward, Thomas represents a long lineage of cattle farmers whose livelihoods and traditions are deeply rooted in the savannahs and settlement lands of the village. His family has been rearing cattle

for generations, relying on the lush, untamed backlands that have long supported

Berbice’s livestock industry.

Over the years, Thomas has skilfully combined traditional

farming wisdom with modern scientific approaches, ensuring that his farm remains productive, sustainable, and competitive in an evolving agricultural landscape.

Although Thomas’s approach to farming is guided by decades of traditional knowledge, he is not one to shy away from innovation. A few years ago, he became a beneficiary of the Artificial Insemination (AI) Programme spearheaded by the Guyana Livestock Devel-

opment Authority (GLDA)

— a national initiative aimed at improving animal genetics and productivity across the livestock sector.

Before introducing AI on his farm, Thomas often struggled with low milk yields, smaller carcass weights, and

reduced growth performance in his herd.“We used to have good cows, but the production was limited. The animals were smaller, and milk production was not always consistent,” he recalled.

Through the GLDA’s AI TURN TO PAGE XVI

By Shaniya Harding

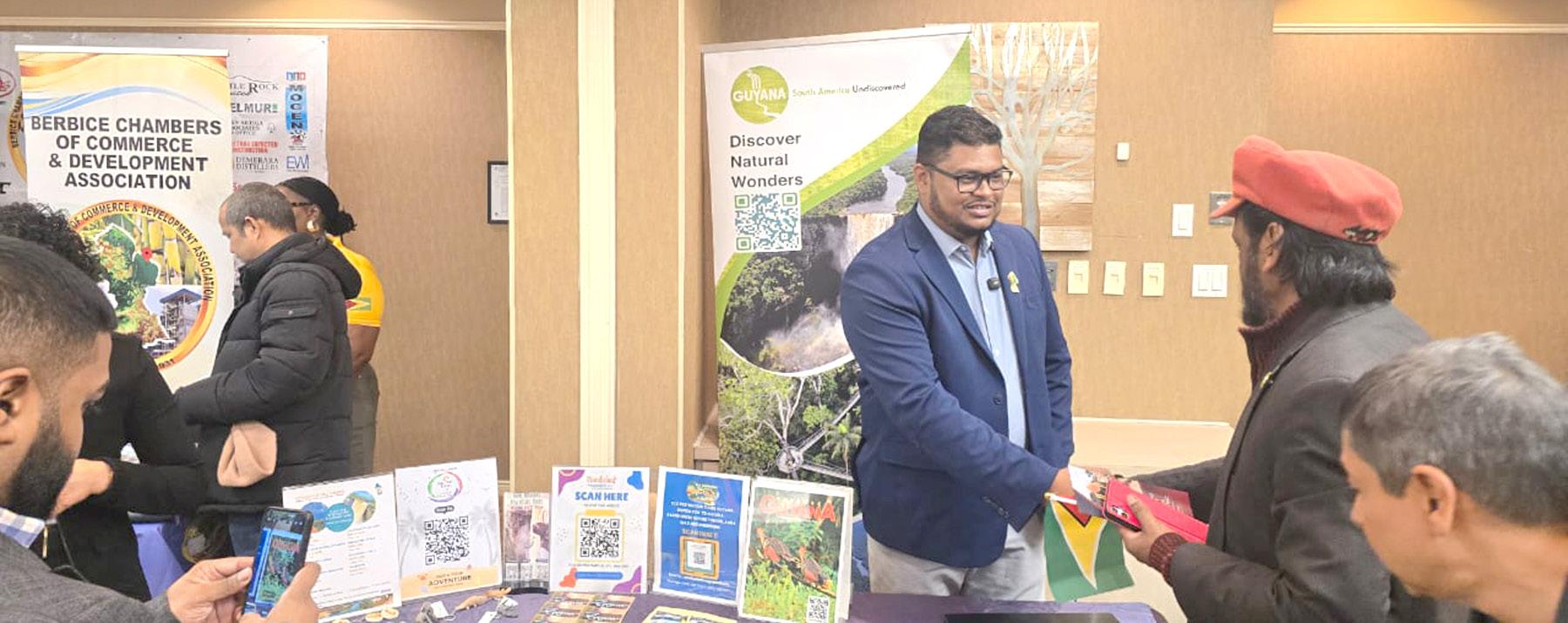

GUYANA’S tourism industry is experiencing remarkable growth and, while the influx of tourists showcases rising interest, the increase in licensed tourism businesses and tour guides highlights steady progress across the sector. This week, Pepperpot Magazine sat down with Chetnauth Persaud, Manager of Training and Licensing at the Guyana Tourism Authority (GTA). He spoke about new and emerging businesses, the path to becoming a licensed tour operator in Guyana, and why it matters for strengthening the tourism industry.

As Manager of Training and Licensing, Persaud ensures that those entering the tourism field are competent, well-rounded, and skilled enough to handle a wide range of challenges, conflicts, and emergencies.

“My role here at the Guyana Tourism Authority is mainly to manage the Training and Licensing Department, which deals with training of the tourism industry. This involves training of all the hotels, tour lodges, tour operators and tour guides within the industry.” He added, “The licensing side of that is to license all the hotels, tour lodges, tour guides and tour

operators.”

Currently, the GTA is responsible for several training programmes, most of which focus on customer care in efforts to raise and maintain the standard of hospitality in Guyana. The Authority is also responsible for training tour guides and tour operators — two major pillars of the industry. “We deal with our tour guides a lot because we want our tour guides to be well trained and licensed. So we do tour guide training, first aid and CPR, hygiene and sanitation training, culinary training, and business management training for the tour operators.” The GTA also provides training for the business side of tourism.

“Experiential travel training deals with pricing for tour operators. Mixology training also deals with our bartenders and mixologists. It’s not just about mixing drinks, it has so much more to do with customer service. All the trainings involve the overall development of the industry.”

The robust and diverse training programmes offered by the GTA are perhaps one of the reasons the agency has seen such an influx of interested people. As Persaud highlighted, the GTA has witnessed tremendous growth in Guyanese joining the sector. He explained that the Authority is now on course to train

some 2,750 individuals. “We have seen tremendous growth in the numbers of training that has been done. When I started working in 2019 we were training 450 persons. Our target for 2025 is 2750, which we have surpassed the target last year of 2500.” He added, “This year our number is 2750, which we are well on the way of hitting. We are currently at 2300 and something.”

Whether they are tour guides or not, Guyanese are naturally hospitable, friendly, welcoming, and always ready to help. Persaud believes this innate warmth is one reason for the sector’s success and a driving force behind its continued expansion. “I think it has a lot to do with our natural Guyanese style.

We love being hospitable, we love working in the tourism industry, we love giving information. We see a lot of people flocking the tourism industry. They want to be tour guides, they want to be managers, hotel workers, restaurant owners, chefs.” He further added, “I think the interest and the drive are coming from people themselves wanting to showcase that, which speaks more to national pride. Everybody wants to improve their skills to be a part of the tourism industry.” While interest in the sector is strong and growing,

licensing remains a major part of the industry and of the GTA’s work. Businesses, both new and established, across Guyana are working to get licensed — a sign, Persaud says, of rising standards within the expanding industry. “We have seen a growth in the licensing industry also. A lot more tour guides want to be licensed, tour operators are pushing to get their licence, and interior lodges and hotels are pushing to get licensed. It has become some kind of competition now, businesses want to be the first to be licensed. We had one this year that became the first to be licensed and wanted us to post it that way.” He added, “Any licensed business can reach out to the GTA for free staff training in areas like dining etiquette, business ethics, culinary arts, mixology, and customer service.”

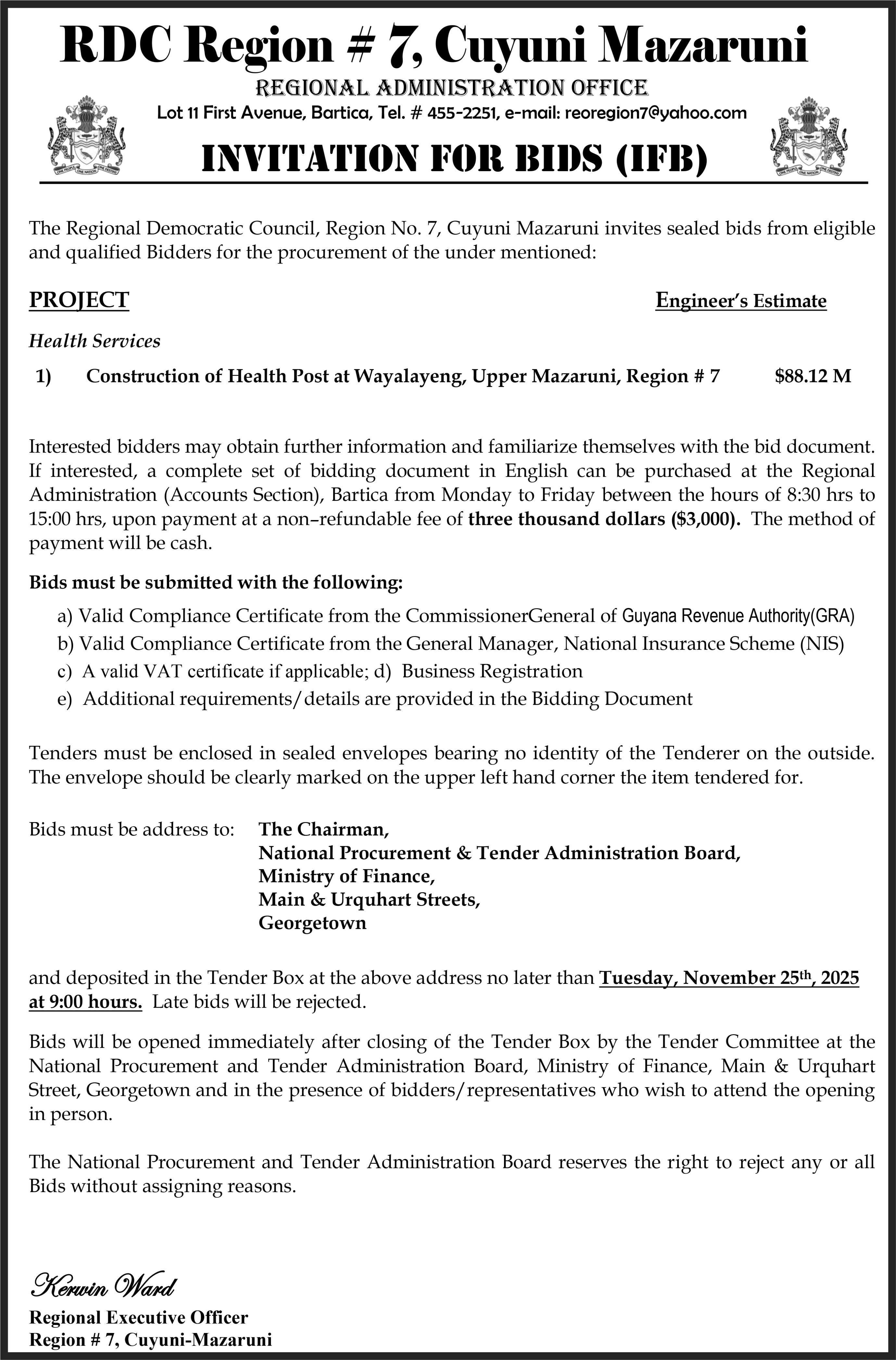

The first step for a business seeking to become licensed by the GTA is obtaining the required permits. As Persaud explained, guides and operators who wish to gain their licences must secure an EPA permit, fire permit, proof from the housing authority, business registration, and compliance documents. Once that is done, the GTA creates a file, conducts an inspection, assists with fixing any issues, and issues the licence. “You pay a reg-

istration fee to the GTA of just $2,000, and for hotels and lodges, the fee increases based on the number of rooms. Tour operators pay a standard fee of $25,000 to get licensed, plus a $2,000 registration fee.” Persaud further added, “They must have a business registration, NIS and GRA compliance, an operational plan, and an emergency plan. Basically, everything in your head about your business, we want to see it on paper.” Tour operators are also required to have public liability insurance and a customer waiver form for guests to acknowledge possible risks, along with a feedback form for guests to share their experiences.

Becoming a licensed tour guide follows a similar process, according to Persaud. Guyanese who aspire to become guides can be licensed in just a matter of days. Although it may sound simple in theory, the GTA’s training programme is designed to be thorough, equipping new guides with all the skills they

need for a safe and successful tour. “All a person needs to do to be a tour guide is first identify that you want to be one. It sounds exciting but it’s really hard because you are responsible for your guests for the entire day. Tour guides must complete a tour guide training, two days of theory and one day of practical. Those in interior locations sometimes go for four or five days.” He added, “They also need to complete first aid and CPR training, submit a police clearance, CV, and basic medical. Once you complete that and pay your fee, you become a licensed tour guide. It’s as simple as two weeks that you put in, but you must have the drive to be a tour guide.”

As Guyana’s tourism sector continues to reach new heights, training and certification are just one part of the bigger picture. The nation is also working to improve infrastructure, transportation, and accessibility. But industry professionals like Persaud see the future of Guyana’s tourism as exceptionally bright. “We need to make sure hotels get the right training, have the right policies, and are guided in the right direction.

The GTA is doing very well in ensuring training and licensing are being done properly. I see Guyana becoming a very big tourism destination for nature, culture, adventure, and culinary tourism.” He added, “Our product will appeal to adventure tourists and those who want to go off the beaten path or relax. I see the product growing into something bigger than what we expect it to be, but we must ensure everything grows in the right way.”

TRINIDADIAN poet and publisher behind House of Lilac, Aminah Ali, speaks on her creative origins, navigating identity, and shaping new spaces for Caribbean writers to be heard.

Trinidad and Tobago writer and publisher Aminah Ali began writing poetry out of curiosity and self-expression, seeking to make sense of identity, faith, and belonging. What started as short musings on Wattpad and Instagram grew into two published poetry collections and the founding of House of Lilac Publishing, a space dedicated to amplifying new voices across the Caribbean. In an interview with Pepperpot Magazine this week, Aminah highlights the challenges young Caribbean writers like herself face, her work and publishing house, and what could be the next step in creating a Caribbean literary community.

Aminah’s love for words and writing began early. When she was still in school, Aminah would spend long hours expressing herself through words in her room. Coupled with her love for photography, Aminah began posting her work online. Today, Aminah’s work has blossomed, and she is one of the loudest young voices in Caribbean literature.“So it became a thing where I’d post photographs, anything artsy-looking and paired with a quote. And from that, I was able to write poetry, some

poetry on Wattpad, poems. It wasn’t good because at that time, I didn’t really know how to write poetry. And I didn’t really study that much literature, only up to Form 3 in secondary school. However, it prompted me to start an Instagram account with the same idea of putting photographs and pairing it with my own words, like quotes, at the beginning. And I started to build from there.”

Aminah’s origins and background continue to have a profound impact on her work. Growing up in Trinidad and Tobago, she used her words to understand her family, community, country, and herself. Her first published works, Through the Lilac Window and Lilac Honey, were collections of poems that addressed a variety of themes, among the most significant and personal being family.“In terms of my upbringing has influenced my writing as well, I include my family stuff, like my grandmother. She’s from Venezuela. And, I dedicated a poem to her. I have never met her, but, you know, they are my bloodline. So, I dedicated a poem to her with her name, her full name, in my second collection,” she said.

Aminah says her writing process has not changed very much over the years. She follows a simple routine of free-writing, coupled with her use of dictionaries and thesauruses, to find the perfect

words that give her poetry a unique style.“My writing process, I would say, is nothing too strict or anything like that, because at the moment, yes, I write poetry. I free-write a lot, however, too. I use a dictionary, I use a thesaurus, I search up Google words, usually, if there’s something that I think that I want, I would choose a word.” She added, “I use big words in my poetry, and some people, they tend not to like that. But that is me, how I write in terms of me wanting to expand my craft and whatever, make it interesting,” she added.

In 2023, Aminah launched House of Lilac Publishing, a venture she says is focused on new voices. House of Lilac saw massive support from the beginning and continues to be a stepping stone rather than a hurdle for young Caribbean writers.“The creation of House of Lilac was the fact that people were coming to me to ask me how I do this, how I do that, how do I make a book, and I just wanted to help people.

So that’s how House of Lilac was made, and I formulated a team who were in departments like illustration, editing, infographic, and designing.” She added, “And even to myself, it took me years to reflect on how the publishing works, only after I published my first poetry book, then I understood more things, and in terms of building a network with other local

authors.”

While House of Lilac brings one major hurdle to the forefront, Aminah says Caribbean writers face a number of other challenges. Marketing is one of the biggest, says Aminah. While the region is full of young creatives, their work may never truly be seen, simply because of a lack of marketing and publicity.“Marketing is one of the biggest problems.

A lot of them, some of them, I mean, obviously, yes, they may not know how to market, and then some of them, when they put out the book, they just leave it there, you know, but they want to get sales. Marketing is a lot of recycling, but also with reinvention,” she added. “There are a lot of good books out there, especially self-published. Some people might not want to buy self-published books because they will have errors in them. But some people, they have their own team, and these books are so good too.”

But there is good news. With the introduction of new literary festivals, inter-Caribbean literary support is growing, and writers like Aminah say it’s more vital than ever.“I think inter-Caribbean collaboration is something so important now, especially to make it as a hub, a growing hub. For me, I think even being a part of the BOCA lit fest opened my eyes.”

She added that this regional support plays a role in learning as well as marketing. “And when I started marketing Lilac Honey, I realised there were other authors just like me. We became friends. If we network and help each other out in a good way, we are able to formulate a community through that. However, it’s still growing.”

Aminah hopes that her work will continue to inspire and move. Her work is often described as relatable and raw, qualities Aminah says she aims to convey. Through real-life themes and bold words, she hopes to make everyone feel just a bit less alone in this ‘universal struggle.’“I think the biggest thing for me is resonance. Even as a person, we have our own

mundane life, and then we have our struggles and obstacles. It may be universal. Even though me and you, we go into a struggle, it may not be at the same level. But we understand to have empathy and ways of coping with it.”

She added, “I would refer to poetry as a way of resonance and coping, to feel like you’re not alone. To be alone, it does be hard for some people. Sometimes you need reminders of who you need to be or who you need, who you might as well put you across.”

Currently, Aminah is working on a few new ventures, with a third poetry book, a folklore-inspired

novel, and a House of Lilac anthology all under development.

Although novels are new territory for Aminah, she is excited to try her creative hand at something slightly different.“I don’t have a title yet. So I will start with the novel first. It’s not a werewolf book; it has little sprinkles of local folklore characters that I want to incorporate in it.” She added, “I’m currently working on my third poetry book, so hopefully that might come out next year. And House of Lilac has an anthology coming soon, hopefully by December or January.”

By Michel Outridge

AMONG livestock farmers along the West Coast Berbice corridor, one name is often spoken with deep admiration and respect — Dr Joel Dilchand. Known for his calm professionalism, hands-on approach, and unrelenting commitment to service, he has become a trusted and beloved figure among farmers

Whether he is making early-morning rounds to inspect herds or responding to late-night calls about ailing animals, Dr Dilchand never hesitates to lend his support.“Once it is legal and within my duty, I will go out of my way to help farmers,” he said. “I’ve always believed that veterinary medicine is not just about treating animals, but about serving people and ensuring their livelihoods are protected.”

Born and raised in Queenstown Village on the Essequibo Coast, Dr Dilchand’s love for animals took root from a young age. He recalls helping his grandfather, Ramdial (Fazal), care for his Brown Swiss milking cows at Hampton Court.“After school, I would go with him when he was feeding the cows with antelope grass mixed with molasses and stockfeed,” he shared with a

smile. “When they were sick and he couldn’t handle it, he called in the veterinarian, and I would stand by to assist in measuring the doses of medication. That’s how I fell in love with livestock.”

Even today, he credits those early experiences for shaping his deep respect for animals and his passion for the field.

He attended the Anna Regina Multilateral School,

where he pursued studies in agriculture and excelled both academically and practically, earning double awards of excellence. After completing eight CXC subjects in 2002, his father, Mr. Cecil Dilchand, played a pivotal role in guiding his next steps.“One day in 2003, my father came home with a government scholarship form,” he recalled. “When I looked at the options and saw veter-

inary medicine and zootechnics, I knew right away what I wanted to do.” That decision marked the beginning of a life-changing journey.

He was awarded a scholarship to study in Cuba at the Universidad Central ‘Marta Abreu’ de las Villas in Santa Clara. There, he spent one year mastering Spanish and five years studying veterinary medicine and zootechnics.“Those six years were some of the most defining years of my life,” he said. “The Cuban education system was rigorous but practical, and it really helped me develop a scientific mindset.”

He graduated in 2010 and returned to Guyana with a strong sense of duty to give back to his country. Upon his return, he joined the Ministry of Agriculture and later the newly formed Guyana Livestock Development Authority (GLDA).

One of his earliest hinterland assignments was in Region One (Barima-Waini), stationed at Port Kaituma, before being transferred to Region Five (Mahaica-Berbice), where he has since spent the majority of his professional career. In 2014, he was appointed Regional Coordinator for GLDA, overseeing the region’s animal health, breeding, and production programmes.“Region

Five has the largest livestock population in Guyana,” he noted. “It’s a challenging responsibility, but I see it as an opportunity to make a real difference in farmers’ lives.”

Dr Dilchand currently supervises a team of thirteen officers, including livestock extension officers, artificial insemination technicians, and veterinary staff. His work involves animal health surveillance, farm visits, ante-mortem inspections at slaughter poles, and the issuance of slaughter permits. He also provides veterinary reports and evidence to the police in cases involving animal cruelty or ownership disputes.“My job goes beyond treating animals,” he explained. “It’s about ensuring food safety, protecting livelihoods, and supporting rural development.”

Dedicated to continuous learning, Dr Dilchand has undertaken several professional development programmes both nationally and internationally. These include training in foodborne disease surveillance, animal and plant health inspection in Mexico, parasitology and

immunology at the University of the West Indies in Trinidad and Tobago, poultry disease response at the University of Delaware in the United States, and African Swine Fever preparedness at the University of Kansas and in Puerto Rico. He has also completed courses in Geographic Information Systems (GIS) for animal disease surveillance.“Every training I attend adds to my ability to serve better,” he said. “Veterinary medicine keeps evolving, and we must evolve with it.”

He currently serves on the Veterinary Board of Guyana (since 2021) and as a director on the Ministry of Agriculture’s Board (MARD) since 2022.“These roles allow me to contribute to national decision-making and policy development for the livestock industry,” he said proudly. “It’s fulfilling to be part of shaping the future of agriculture in Guyana.” In Region Five, he leads several of the government’s major livestock initiatives, including the Barbados Black Belly Sheep Project TURN TO PAGE XIV

By Shaniya Harding

OFTENTIMES, when Guyana is seen on the international stage, the focus remains on its captivating lakes, unique wildlife, and one-of-a-kind rainforest. But American tourists Toni Thompson and Robert Langford say their journey has given them a front-row seat to Guyana’s cultural and culinary vibrancy, and the rich history that has shaped the architecture of the capital city.

Speaking with Pepperpot Magazine this week, the duo shared their experience— from a spice-filled food tour through Georgetown to conversations about heritage and history—saying the country’s warmth and diversity have left a lasting impression.

Guyana is not entirely unfamiliar to educator and writer Toni Thompson. Having lived in South America during the eighties, she had learned about the small South American nation with a past similar to that of the Caribbean. While Guyana’s natural beauty is certainly captivating, Toni says its uniqueness lies in its flavours and diversity.“I’ve been to most coun-

tries in South America, which all have a different flavour, and I just always am open to what is going to happen. I just knew it was a tropical country, which makes people a little different. They tend to be more open and outgoing.”

She added, “I find people to be absolutely incredible. We walk down the street, people say hello. People are very, very friendly, open in the restaurants. We have had incredible service. I found people great, and I think that there is a great deal of respect for the multicultural history here.”

Fellow traveller and California native Robert Langford shares similar sentiments. With a background in engineering and construction, he says Guyana’s architecture is among the most fascinating aspects of the tour. While the historic buildings tell stories of the past, Robert notes that the skyline also reflects a visible wave of modern development.“I really didn’t have a concept of what the country would be like when I got here. I did know that economically it was not in the best of conditions,” he said. “I do know that there’s been a tremendous infusion of cash

based upon the industry that you’re now developing as well. I foresee that there’ll be a tremendous social change that’s going to be taking place because of it.” For Robert, the mix of heritage and new infrastructure — the way colonial charm meets emerging luxury — is in itself a sign of Guyana’s changing landscape.

While Toni and Robert plan to visit popular tourist destinations like Kaieteur Falls, their first introduction to Guyana came through the tastes, sounds, smells, and sights of Georgetown — an introduction they say made them fall in love with the country. Recounting their experience, Toni highlighted the Guyanese food tour by the Singing Chef Adventure, the markets, the history, and the people as the most unique parts of their visit.

“The first thing we did was go to visit a couple of historic places to set the background on slavery and indentured people, people coming from India, from Africa, other places.” She added, “Then we went to do some marketing. We went to a few markets, and we went to a place, Matai’s, and said

we’re going to get some spices. I envisioned a bunch of jars, and we walked in, and I said, spice market. It smelled incredible.”

Throughout the tour, Toni and Robert gained insights into Guyana’s history, culture, and cuisine. As Toni highlighted, Guyana is home to fruits and produce not seen anywhere else in the world. Combined with the hospitable vendors and vibrant market scene, it made for an unforgettable experience.

This, she says, is why more information about Guyana is needed — not just locally, but internationally as well.“We were buying fresh produce and talked about some of the produce that was very unique to here. Then we went to their place and started chopping, cooking, preparing step by step. I think I might be able to go home and do it myself.” She added, “I teach about culture and diversity, and I realised that there’s very little information about Guyana in that material. I think I’m going to really incorporate this in my presentations so people can look this up, learn about the culture, and come and visit.”

Robert, however, admitted that he was surprised by Guyana’s deeply layered past. Learning about the various cultures and the people who brought them to these shores, he says, made him appreciate Guyana’s diverse flavours even more.“The

cultural diversification is a lot broader than I thought it would be. As we learned about the different immigration that has come into the country, it’s really affected the food, the style of food, and the preparation for the food. I found that to be very interesting and very flavourful.” Moreover, Robert is an advocate for historic buildings, and he says Guyana’s are worth preserving.“I see some of your older buildings, the wood structure, and I really have an appreciation for that type of construction and how it looks. Hopefully, your country will maintain that and don’t be in such a rush to knock down the old to build new. Keeping that history of your country would be very important.”

Safety is another area where Toni and Robert share positive reviews of their time in Guyana. Although some online forums may list Guyana as unsafe, Toni says that during her time exploring the capital, safety was not a major concern.“I look at countries and their safety levels, and I can tell you quite honestly, I feel safer here than I do in many places in the United States right now. But again, we don’t just get up at midnight and go out and walk in unknown areas. If we’re going to go in the evening, we’re going to go with a group,” she said. Robert shares a similar view, adding, “When I read up on

it, this country was listed as level three, reconsider travel, and it’s primarily because of crime. That was a consideration in coming here, and we probably won’t be wandering around at night. But I feel that’s really unjustified.” As the duo and their team move forward with plans to explore the more natural side of Guyana, they say that the history, culture, and hospitality of Guyanese people are what they would most encourage others to experience. As Toni explained, “I say come here to visit the people and learn about their culture. Come here to visit and enjoy the people and be open to things. Take organised tours and get to know things, get to know the people, and I bet if we’d be here a few days, we would meet somebody that we’d end up at their house or doing something with them.”

She added, “Everybody, come and visit Guyana. I’m telling you, it’s phenomenal. It’s so cool, awesome, and you will have incredible, healthy food.”As Robert added, “The improvements that currently are going on are impressive. I can see that prior, some of the areas needed work, needed repair, and I can see a lot of that going on now. The people we’ve met so far have been very friendly, and I find it a very pleasant experience. I would recommend other people to come here.”

By Shaniya Harding

FOR Guyanese artist Sameer Khan, art has always been more than expression — it’s survival. From a childhood shaped by hardship and resilience to the loss of his home and more than 70 art pieces in a fire last year, Khan has continually turned tragedy into transformation. Now, at 34, he prepares to unveil Elysium, his most personal and abstract exhibition yet, opening on November 14 at Castellani House.

Through vibrant strokes and layered emotions, Khan’s work invites viewers into a space where imagination meets healing — where pain finds beauty in abstraction.

Art has been a catalyst for self-expression since Sameer was a child. Growing up on the Essequibo Coast, his childhood was characterised by things he says no child should see. Grappling with family issues and hurdles, art became his outlet.

“I grew up in Essequibo, and at a very tender age, I witnessed some things that I think I should not have wit-

nessed as a child. And I think I’ve used art as a coping mechanism to get a grip on my emotions or express my emotions. At a very young age, I was very skilful in drawing,” he said. Throughout his childhood, Sameer won various art competitions. With his mother’s support, he fell in love with, and pursued, art. While his primary school years were filled with challenges, high school became a fresh start. Since taking art seriously in secondary school, Sameer has never looked back.

“I had a period of time in primary school where I was bullied and abused by one particular teacher. Then I went into secondary school, and that was kind of like a relief for me — new people, new teacher, new atmosphere, new settings, everything was new. And I was willing to step into that.

I started winning many art competitions again.” He added, “Year after year, I would come up as a national winner or in the top three consecutively. After my CXC exams, my results weren’t even out

yet, and my school was calling me to go back and teach.”

Teaching was where Sameer perfected his skills while guiding others to create art. Although he initially wanted to be anything but a teacher, he soon fell in love with the profession.

“I didn’t want to get into teaching. I was looking for anything else but teaching. Unfortunately — or rather, fortunately — I ended up in teaching in Georgetown. I was teaching visual arts and craft from Forms One to Five. That’s how I started. And I was teaching Spanish from Forms One to Three, and technical drawing from Four and Five,” he said. “After a few months, I changed that. I was juggling two schools — teaching visual arts, craft, and Spanish from Forms One to Five in one school. In the other school, I had to teach up to Grade Nine Spanish, and then Grades Seven to Eleven art. I did that.”

While teaching, Sameer was also expanding his creative horizons, learning new art forms and developing diverse skills that have made

him the multifaceted creative he is today.

“While I was doing so, part-time I would do décor, backdrops, set dressing, costumes, sometimes special effects makeup for different productions at the Cultural Centre. I would do banners and so on — painting and tinting these banners. And I just evolved, basically.” He added, “Then I went a little bit into floral and cake décor. Basically, I tried to get into every single thing so that I don’t get bored doing one particular thing. I can do portrait drawings, whether coloured or black and white, and I can do them in painting forms. I can do sceneries and so on.”

Although versatile, Sameer has developed a unique signature style that includes strong abstract elements. His art is layered and profound, using shapes, shades, and depth to convey more than a scene — it conveys emotion, much like poetry.

“I also have a love for abstract. I think abstract is poetry, and that means a lot more to me rather than just doing a portrait or a scenery. I mean, come on, anybody could just say, I want to go and paint the Kaieteur Falls TURN TO PAGE XVII

IT can be frightening when one realises that we are part of the “save the Earth generation”. For as long as I can recall, that title has often been emphasised. It is often said that the future of humanity — and by extension, our planet — lies in the hands of young people. That reality can feel like a huge responsibility for many, especially those actively committed to environmental and climate justice.

We often measure our everyday actions; we try to be politically correct and stay conscious of global climate conversations, and we seek to critique how our daily decisions will impact “tomorrow”. These realities and this sense of responsibility

can lead to anxiety and stress about our roles in climate change and justice. It can be quite overwhelming. The concept of “climate anxiety” is now being coined by psychologists worldwide. It is being recognised as the feelings of anxiety and fear that we experience about the growing concerns surrounding the state of our planet and environment.

Guyana, and by extension the Caribbean, has experienced many environmental changes in recent decades due to climate change. I have previously written a significant number of articles on environmental impacts, including floods, receding shorelines, and deforestation. When I was younger, the concept of “climate change”

was amateurishly dismissed as a “thing of the future”—a reality to be spoken of only in the future tense, a reality that existed only for humans of the decades to come.

Unfortunately, in recent times, it has been scientifically proven that climate change has been increasingly affecting our ecosystems, biodiversity, human social systems, and overall daily lives — from the floods in 2020 that devastated livestock farmers, resulting in millions of dollars in losses of animals and farmland, to the increasing heatwaves that often lead to wildfires and loss of trees in forested regions. It is devastating — and, unfortunately, we are presently living through these devastations. As someone actively reading

and learning about climate justice and change, I often hear the importance of owning the realities we now face. Humans are not always keen to “own” the devastating realities they have created. However, the more we understand climate justice and environmental science, the more we recognise how our everyday actions affect the environment around us.

One professor of mine who teaches these concepts once joked about not having the role of teaching a “doomsday class”, noting that sometimes it is hard to be optimistic about environmental justice. Unfortunately, there is truth in the humour, because I often find it difficult to remain optimistic after those class sessions.

I can recall the first time I experienced “climate anxiety”. I was grappling with thoughts about the quality of the Earth’s living spaces for my children. Will they experience better or worse

air quality? Will they be able to enjoy the breathtaking Atlantic Seawall in similar ways? What crisis management systems are in place for climate disasters, and how effective are they?

These were all questions I had, and I kept wondering if I was being too dramatic or too critical. I eventually concluded that my questions and fears were all valid. I wanted to share these personal reflections to show a possible solution — how you can fuel these valid fears into an actionable response.

Similarly to my advocacy through writing, you too can channel your concerns and anxiety into awareness and action for change. The Caribbean region — and, by extension, Guyana — is often considered “climate resilient,” but I personally believe we sometimes hide our fears behind the concept of resiliency.

However, I want us to push beyond this narrative

of resiliency and accept that it is okay to be fearful of the unknown state of our world. As such, the next time we experience flooding due to rainfall or a wildfire, I want us to remember that our fears are valid and important to consider — but so is our call to action.

In the words of Caribbean climate activist Adia S. Daniel from St Vincent and the Grenadines:

“This is not a scene from a horror movie, but a grim reality that we in the Caribbean face due to the devastating impact of climate change.”

If by chance you feel overwhelmed by the news or realities of our climate, I would advise taking a break from the media, talking with climate buddies or other activists, taking care of yourself first before thinking of other people and things, and most importantly, fuelling those fears into meaningful solutions for our planet.

BECOMING a Chief Executive Officer explores the realities of the position, including identifying and developing skills, delegating work, adopting a leadership mindset, and allocating resources. Geary addresses the most pressing aspects of what a CEO actually does and how to tailor your mentality to become more like one.

In life, not everyone can do the same thing, nor can they become everyone else. Therefore, it is important for those who want to become great leaders to find their purpose.

You must be aware of what you are required to do and what you are able to do based on your specific gifts and talents. Each person has their own unique duties to perform on this Earth, in whichever field they find their calling. Once you find your purpose, you must make every effort to operate within that calling.

For some people, finding their purpose can take time, as they must go through a process of metamorphosis — much like a caterpillar transforming into a butterfly. Others find their purpose at a very tender age. However,

once you find your purpose, you must take great care to enhance your area of specialisation or skill.

While you may know your purpose, there will always be people who believe you should be something else. Be wary of those who try to influence you to be someone you are not. Some people are afraid of your passion because it will present a challenge to them — so they try to be a stumbling block in your path. Therefore, remain focused on your purpose and do not be easily distracted. It is your passion that will separate you from others with similar talents. It will prompt you to act and grow. Stay within your purpose, since that purpose may make you the next CEO. Your individual purpose is rich with many important qualities that others have not been endowed with. Do not throw away your purpose for what someone else has. Each purpose has its own challenges and glory. Purpose is like a machine: the manufacturer often builds it for a specific function. You were born — or built — with a specific purpose.

Once you have found your purpose, it is important to seek opportunities to learn and develop your knowledge and skills. While you may know that you have been

called to lead, you must also develop the skills and knowledge needed to help people. Some of these skills may come naturally, but others will require focused learning and training.

You can learn from others, even when they are not speaking. Observation is a powerful way of learning, as communication can be both verbal and non-verbal. Some great leaders teach simply by example. While saying little, they demonstrate invaluable skills — and you are expected to learn from such leaders.

You will be required to manage people and machines (equipment) to help the organisation move forward. To do so, you must be knowledgeable about your organisation and understand its needs, as well as those of others in leadership roles. It is often difficult, if not impossible, to lead if you do not know your organisation or have good team players within it.

Sometimes, you must build a winning team or take the opportunity to recruit people who will help you succeed. Remember, your greatest assurance of longevity within the organisation is your ability to make it successful. Failing to do so

may force you to change positions or organisations — often a painful experience for a CEO.

As the CEO, you must be engaged with all aspects of the organisation — operations, human resources, strategic management, marketing, finance, and more. While these areas often require the help of technical experts, you will still have to work closely with them to ensure profitability and sustainability.

All aspects of short-, medium-, and long-term planning are critical in your decision-making. Therefore, you must ensure you have accurate, timely information to support these decisions.

A CEO must also ensure there is a reliable information system that enhances decision-making by all employees. Staff should have the appropriate level of access to key data and information to make sound decisions. As CEO, you must be a good

communicator, motivating employees to accept and work toward the organisation’s vision.

Section C: Moving On

The two important sections above should help you in your career and duties on the job. Eventually, you will accomplish many things in life and reach the point where your active working days are coming to an end. Some people welcome retirement, while others dread it because they are unsure what to do with their time.

The final section of this book provides guidance on how to prepare to exit the business world. When preparing to leave, it is wise to share your knowledge and experience with others. Passing on the reins to successors is often a challenge for many people. Some hold onto knowledge, unwilling to share it — but you have a great responsibility to make

this world a better place.

Share your knowledge and experience. Take time to mentor and coach others. Establish a quiet period in your life to reflect on things — good and bad. During this period, you may find new energy and purpose. While some people are handed a baton to run their race, others must fight their way to get it. Whatever your conditions for success, you must help others achieve the same. If you can mentor others, people will speak well of you — both in life and after you’ve passed on.For more information about Geary Reid and his books:

• Amazon: www.amazon.com/author/gearyreid

• Website: www. reidnlearn.com

• Facebook: Reid n Learn

• Email: info@reidnlearn.com

• Mobile: +592-6452240

I READ a letter to the editor by Sahodeo Bates about the shooting of a jaguar by an over-enthusiastic miner who was in possession of a shotgun or rifle. He had stalked and killed the jaguar, motivated by no threat from this animal — except, it seems, driven by a need to satisfy some inner missing link.

I’m no stranger to the hinterland. I can recall a walk to the backdam in the 1970s; upon crossing a tacouba, I saw a snake coiled beneath its edges on the bank of the waterway.

I alerted the late “Cash Morgan” and asked for his cutlass. He looked at me with a questioning, serious stare and responded, “Duh snake do yuh something?”

To that, I remained somewhat pensive. I came to understand why, in checking our jute-bag beds, we explored for snakes which, if found, would be thrown out of our huts and hammocks, but seldom killed. I mentioned a similar experience at Kura-kura involving tiger cats (ocelots) in a previous article.

The age for the callous killing of animals due to our primate fears has passed, due to the realisation that some animals are not to be eaten, nor to be eliminated. The ancient errors of humans — the self-destructive egos of elimination initiated by some human tribes — led them to consume without ob-

serving the volumes they destroyed. They destroyed even what they did not eat, thus committing themselves to starvation and extinction.

Much like the example of the rise of human life and creativity on Easter Island, and the probable reason for its population’s disappearance, they ate everything and thus starved to death, even if they resorted to cannibalism, too late.

In trying to understand this garden that our species is supposed to explore and sustain, we begin with the life forms and the medicines among the fruit and botanicals that the older life forms (animals) explore and use.

The more balanced among our

species also explore, observe, and adopt — but it’s the multitude of others of our kind that we must be cautious with.

My children can accuse me of depriving them of visits to the zoo.

After seeing animals in the wild, observing them in extremely limited-size cages can be disturbing — to see an ocelot in a 3ft by 4ft cage, on average, when you’ve seen that animal move in the wild at its natural speed.

In that case, the cage becomes a thing of torture. I’m sure that some of our caged animals, without movement, went mad before they perished.

There’s an area in the wild that

doesn’t come to the fore — that some animals should not be eaten. I’m not going to mention any species; that should be left to the professionals.

Most of nature is older than us humans by over 100,000 years. We like to chant about wildlife, but those who study these areas should bring these life forms to the fore. You’d be surprised what some folks eat.

In closing, we do need to guard our wildlife. There are lots of “never see come fuh see” folks who might be tripping on a newfound permitted lethal toy—they need guidance.And don’t know it, till next time.

Mustafa Ali was perspiring profusely as he waited impatiently for Chandini Sharma, the love of his life. Their Muslim and Hindu liaison was strictly forbidden by almost everyone in their village. He crouched low behind some sage bushes just outside the six-foot-high brick walls surrounding the compound of her family home.

It was about eight o’clock in the evening, and the only visible source of light was the bright full moon. The temperature was unusually cool for January 1843, in the State of Uttar Pradesh in Northern India.

“Chandini... Chandini, are you there?” he whispered above the din made by hundreds of crickets and mosquitoes. He was very wary of being heard by Ballu, the watchman and guard of Chandini’s family home and compound.

Mustafa kept as still as possible and decided to wait a little longer so as not to arouse any suspicion in Ballu or his guard dog, which was fast asleep. The mongrel was tied securely to a short wooden peg in the hard ground by

one from the large household ever seemed to check on him or his equally lazy canine companion. This approach to security by Ballu, a short and chubby man in his late forties, allowed Chandini—sixteen years old, the youngest child of the Birendra Sharma family—to sneak past him and out of the compound to meet her Mustafa, who was eighteen.

This night was crucial for the two young lovers as they wanted to meet one last time to plan their elopement. They would creep slowly through the sage bushes beside a pathway, as they had done many times over the last few months. The pathway led to the edge of a great stream that flowed past their beautiful, serene village near the town of Kanpur.

They would nervously hold hands, tiptoe down to the water’s edge, and sit on one of the ghats with their feet dangling into the cool,

soothing water as it slowly and silently ebbed along. A great mango tree’s branches provided cover over the ghat in the evenings, and welcome shade during the bright, hot, and sunny daytimes.

Mustafa was about five feet nine inches tall, of dark brown complexion, and appeared older than his age due to his work as a labourer in the village and local sugarcane plantations. Chandini was petite, about five feet tall, fair, and always wore a captivating smile which exuded a sense of mystique.

Their relationship had begun as innocent children playing amongst others in the village square. However, as they grew older, their friendship was frowned upon—particularly by the village elders and their families.

Their clandestine meetings were normally restricted to about half an hour to an hour at most, for fear of being discovered, particularly

by anyone from Chandini’s family or the household servants, including Ballu. They would hold hands and whisper about how much they felt for each other—about the first time they looked at one another and realised that the little glances they exchanged meant more than friendly acknowledgement and mutual respect.

Mustafa was the youngest of Hussein Ali’s seven children, all of whom worked on the sugar plantation owned by Birendra Sharma—Chandini’s father and the Zamindar of the village. The work in the sugarcane fields was tough and included cutting grass and weeds from the undergrowth while the young sugarcane plants grew to maturity.

The grass and weeds were manually cut using a handheld “grass knife”, a sharpened and jagged half-moonshaped iron blade wedged TURN TO PAGE XV

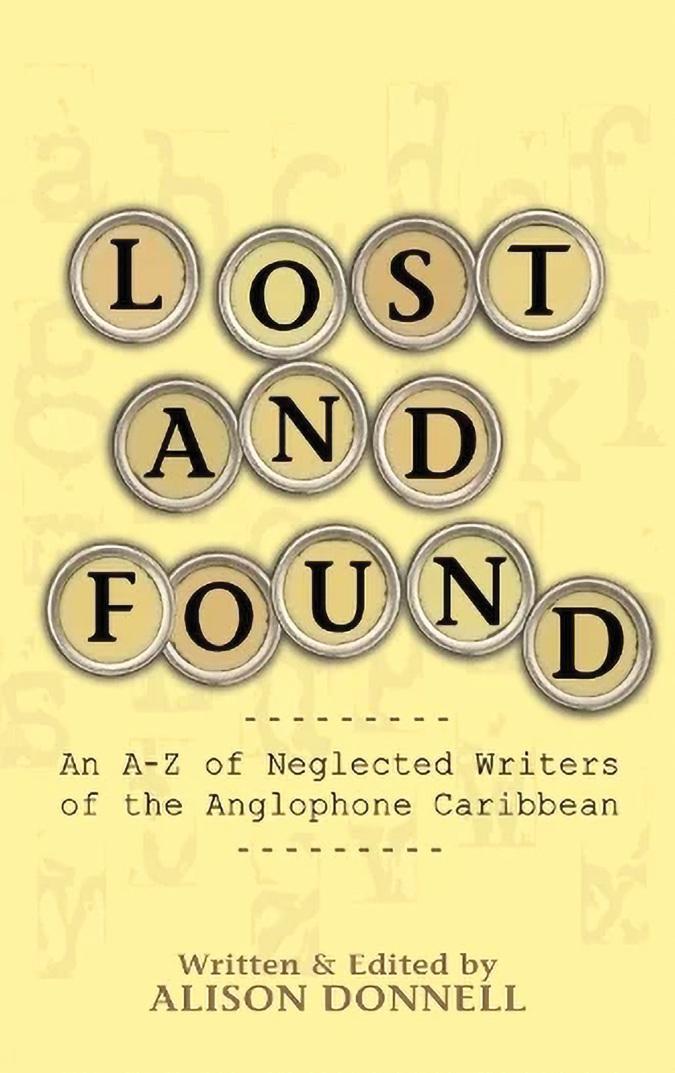

LOST AND FOUND: An A–Z of Neglected Writers of the Anglophone Caribbean, written and edited by Alison Donnell, is a fascinating and necessary book.

Ostensibly a reclamation project, it sheds light on the lives and work of twenty-six Caribbean writers — many of whom have been forgotten or overlooked, their names fading into

obscurity. But more than just a catalogue of literary neglect, Lost and Found serves as an education in the forces — both cultural and institutional — that determine which writers are remembered and which are not.

Someone once remarked that the most essential trait of a great political leader is a sense of destiny — that belief

that their work should outlast their time. The same could be said of writers. Beyond writing for the present, they write for the future; their hope, or conviction, often underpins their creative impulse — that their words will endure beyond their death.

Writers like Shakespeare and Whitman come to mind: figures whose reputations have not only survived but

grown with time. Their works continue to feel urgent, timely, and resonant centuries after their passing.

The writers featured in Lost and Found may not have achieved such global renown, but their contributions to Caribbean literature are no less vital.

Figures such as the Guyanese writer Edwina Melville, Dominican novelist Elma Napier, and Jamaican poet and critic Gloria Escoffery belong in this category — regional voices whose work, though largely unrecognised outside the Caribbean, forms TURN TO PAGE XVIII

FOR it’s purely from nature — a smooth transition patterned with the change of the season.

Sarah sat on a bench in the cemetery, the fallen leaves all around her, a pained look on her face.“I had waited so long for you to come back home,” she said in quiet grief, “but you never did.”

She closed her eyes, reflecting on her past — from a little girl in the countryside — and when she reopened them, she saw the image of that little girl as she ran, tumbling and playing among the dry leaves. She laughed a little, for it was the age of innocence, when there was cheerfulness and joy, and you couldn’t see the cracks in your parents’ marriage — until it all fell apart.

Life had been a struggle for her single mother, and Sarah had told her, “One day I will get a great job and life will be better for us.”

She focused on her studies, assisted her mother in their small business, and excelled in her exams, earning a great opportunity to attend university. It was, for her, a dream come true to pursue studies in medicine, whilst her brother, who had also excelled at high school, pursued a degree in engineering. When she graduated with a Bachelor’s degree, it gave her life a special meaning — but deep within her was still that longing to see her father, even if only for a moment.

That moment came many years later with a brief phone call informing the family that her father was in critical condition in a hospital in New York. The news formed a knot in her stomach, and only then did she ask herself the questions: “Did he think about us? Did he want to see

She was six when her mother and father separated. He had left, looking back just once when she called out to him — and then he was gone. She had cried herself to sleep many nights, hoping and praying for his return, but by then her hopes had somewhat diminished.

us?”

Only he, she knew, could truthfully answer those questions. So now, maybe, they would remain unanswered.

She and her brother travelled the next day, hoping he would survive. By the time they got there, he was not very responsive. She looked at the man — her father — she had longed so much to see again.“This was not how I had hoped it would be,” she said sadly to herself. He looked older than mid-fifties, with thinning grey hair, deep wrinkles, and an uneven tone.“Dad,” she whispered.

He opened his eyes after a long moment, a glazed look in them — and being a doctor, she knew he was close to his end. He passed away that night — a part of her now gone, forever.

At his funeral days later, she and her brother sat quietly as eulogies were read. They had nothing to say because he had not shared his life with them. His wife, his TURN TO PAGE XVIII

and the Zebu Bull Rotation Programme, which involves rotating twelve bulls across different farms to improve breeding genetics.“These programmes are transforming livestock production,” he said. “Farmers are now seeing better meat quality, increased birth weights, and more lambs born per season. It’s a major step forward for the sector.”

Dr Dilchand is quick to acknowledge that his professional growth has been supported by strong mentorship within the GLDA.“I am always grateful to Dr Dwight Walrond, Dr Tihul, and Dr Bowen,” he said. “They are astute leaders with deep knowledge of the industry and are always willing to provide guidance and encouragement. Their leadership style

FROM PAGE V

promotes growth, teamwork, and professionalism.”He also extended appreciation to the Minister of Agriculture, Hon. Zulfikar Mustapha, for the confidence placed in him to lead Region Five’s livestock development.“The success of this region is a collective effort,” he emphasised. “It reflects the dedication of our farmers, the commitment of my staff, and the vision of

our leadership. Our success is built on humility, collaboration, and a balance between traditional practices and modern science.”

Beyond his professional life, sports have played a major role in shaping Dr Dilchand’s character. A talented cricketer, he represented Guyana at the Under-15 level and later played junior cricket for Essequibo. Since 2015, he has captained the Bush Lot Unity Sports Club.“Cricket taught me discipline, teamwork, and patience,” he reflected. “Those same lessons guide me every day in my work as a veterinarian and leader.” While studying in Cuba, he also played basketball for his faculty — balancing academics with athletics as a reflection of his commitment to holistic growth.

Now residing in Bush Lot, West Coast Berbice, Dr Dilchand is the proud father of one daughter and the only veterinarian in his family. His father, Cecil, retired from the Ministry of Public Works after forty-five years of service, and both parents continue to support and encourage him.“My parents have been my greatest motivators,” he said warmly. “My father especially was the one who

helped me find my path, and I’m forever grateful for his guidance.”

Reflecting on his journey, Dr Dilchand said, “Working with farmers keeps me grounded. They remind me every day why I chose this career — to serve, to protect animal health, and to contribute to Guyana’s food security.”

After fifteen years with GLDA, he remains passionate and committed to improving the livestock industry.

“I am proud of what we’ve accomplished as a team,” he said. “There is still much to be done, but I believe that with dedication, humility, and collaboration, the future of livestock farming in Guyana is bright.”

From a boy tending to his grandfather’s cows in Hampton Court to leading the country’s livestock capital, Dr Joel Dilchand’s journey is a testament to the power of hard work, service, and purpose. To the farmers of Region Five, he is not only their veterinarian but also their friend, mentor, and advocate — a man whose legacy continues to inspire the next generation of agricultural professionals in Guyana.

into a wooden handle. A twofoot-long machete or “cutlass” was used to cut the sugarcane stalks about six inches from the base. The cut stalks were tied into bundles using the long grass-like leaves of the plant and packed onto two-wheeled bullock carts for processing into sugar.

Mustafa always took great pride in carrying his grass knife securely tied to his hip with a string tightened around his waist. He had learnt the art of weeding from one of his most experienced brothers.

The village was a small enclave of two-roomed, low-level wooden houses spread out in a loose circle away from the square. A large banyan tree provided natural shade in the middle of the square. Wooden seating was constructed around the base of the tree, where the village elders would normally sit discussing all manner of issues affecting village life. This was also the central meeting point for villagers, where the Zamindar and other prominent members of the community would gather to hold meetings, hear disputes, and deliver judgements on family matters.

Some of the elders held sessions of storytelling which fascinated the children and young people. The youngest used the square as their main playground, chasing each other tirelessly, only to be scolded when the noise became too distracting. Mustafa and Chandini, when very young, often joined in the play and listened to the stories told just after sunset.

The Sharma’s house was the most substantial property in the village, with two floors. There were four bed-

rooms on the upper floor, and the flat roof was often used as a place for sleeping during the dry, cool summer evenings.

The majority of the three hundred villagers were Hindu, who lived in low-level houses about a hundred yards from the square and the Sharma residence. The minority Muslims lived in a few similar houses a little further behind. The Sharma’s house was flanked on either side by a large Mandir and a Mosque.

Hussein Ali’s family were Muslims who tried their best to practise their faith, learning to read the Holy Qur’an in Arabic and observing namaaz five times each day, even while working in the sugarcane fields. They fasted through the holy month of Ramadan and gave zakaat to the poor, whether or not they were Muslim. Those who could afford it undertook pilgrimage to Mecca at least once in their lifetime.

Birendra Sharma was a Hindu of the Brahmin caste who, though not as learned as a Pandit, ensured his family followed the tenets of Sanatan Dharm and obtained knowledge through study of the sacred Hindu texts such as the Vedas, Ramayan, and Bhagwad Gita. The family also served the community selflessly. Indivar, the eldest at twenty-two, was being groomed as his father’s successor while studying to become a Pandit.

The Sharma family funded the village’s only Mandir, built mostly during the gap between harvests. Everyone with a skill—stone and wood carving, carpentry, masonry, roofing—was contracted to work on the building and its

grounds. The Ali family also helped to build the Mandir. Likewise, when Hussein Ali’s grandfather started building the first and only Mosque in the village, everyone, including the majority Hindus, helped.

The Madrasa built alongside the Mosque taught young Muslim boys and girls Arabic and Urdu and the tenets of Islam. The Mandir also served as a school where young Hindu children learnt Hindi, Sanskrit prayers, and Indian classical music, singing and dancing. Everyone in the village communicated in Bhojpuri, and some had begun learning English through contact with the British, whose influence was expanding across Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Bengal.

Both Birendra Sharma and Hussein Ali were mutually respectful and shared a common dislike for the new masters—the latest in a long line of invaders to their beloved country. Their families collaborated to resist the British as their ancestors had done against the Marathas and the Mughals.

In one such battle against the Marathas, their fathers—

close friends—fought side by side. Hussein Ali’s father, gravely wounded while protecting his friend, begged Allah for mercy and his friend to look after his family. This final pact between them included a promise that their families would continue following their respective faiths and never intermarry. The Ali family would also honour their debts to the Sharmas by working on the sugar plantation.

This mutual respect continued with Birendra and Hussein often meeting at each other’s homes to discuss village matters and the growing influence of the British.

On one such occasion, Birendra visited Hussein’s home. Hussein’s wife, Batool, silently served hot green chai brewed over a clay stove before sitting in the courtyard to sift rice. Mustafa stayed in the adjacent room, listening.

“Hussein bhaiya, I need to talk to you about your youngest son Mustafa,” Birendra began.

“What has he been up to now?” asked Hussein, looking perturbed.

“I have heard that he has been secretly meeting my

daughter Chandini. And I am worried that the two of them have strong feelings for each other.”

Hussein put his cup down slowly, surprised. “This is the first I’m hearing of this,” he said. “Have you scolded Chandini?”

Birendra shook his head.

“I wanted to speak with you first, so we can decide how to deal with it together.”

They both remembered their families’ pact—marriage between their children was unthinkable.

“Maybe you can talk to Mustafa and confirm what’s going on,” Birendra continued. “Also, please don’t tell anyone, especially your sweet daughter Aleemah. She’s been passing messages between them when she comes to work at my house.”

Aleemah, nineteen, was close to her best friend Chandini and always advising Mustafa. Smart and inquisitive, she knew her family’s obligation to serve the Sharmas and secretly wished for freedom. “Like the meaning of your name,” she once told Mustafa, “you’re the Chosen One to liberate the family.”

“How did you find out?”

asked Hussein quietly. Birendra leaned forward. “I overheard Aleemah making plans with Chandini for her meeting with Mustafa by the ghat beside the mango tree near the stream.” Mustafa, listening, caught his sister’s name and realised she should no longer be involved.

“If it’s true, I’ll tell Mustafa to stop seeing her immediately,” Hussein said. “He’s of age to marry, and perhaps you can help find him a suitable girl.”

“Thank you, Hussein bhaiya,” Birendra replied. “I’ll ask Ballu to be watchful and make sure none of my family, especially Mahaveer, find out.”

They concluded their meeting warmly. Birendra left, greeting Batool respectfully on his way out. Mustafa, hidden from sight, sat quietly in thought. He knew the strict separation between their religions and that their relationship was forbidden. Any couple who crossed that line faced harsh punishment. His and Chandini’s love could mean ruin—for both their families.

intervention, Thomas introduced superior breeds, such as Holstein and Beefmaster, which were crossbred with his native Zebu cattle. The results have been transformative.“Since the AI project, I’ve seen tremendous improvements,” he said proudly. “The cows are producing more milk, the meat quality is better, and the animals are healthier and larger.”

Thomas now manages a herd of approximately seventy head of cattle, with a mix of traditional and improved breeds. He plans to take his farm’s genetic improvement even further by embracing embryo transfer technology, a next step he is currently exploring with GLDA’s technical team.

A strong advocate for natural feeding practices,

Thomas proudly maintains a grass-fed system for all his animals. He avoids using commercial stock feed as much as possible, relying heavily on nutrient-rich grasses grown in the savannahs and rice-field backlands of Blairmont Village. During the rice-harvesting off-season, he allows his cattle to graze freely in the fields, rotating them as needed to

keep the land fertile and sustainable.“I believe animals should eat what nature provides,” Thomas explained. “The quality of the milk and meat depends on what they eat, and my customers can taste that freshness and purity.”

Currently, his lactating cows produce approximately 1 gallon of milk per day, which his sibling sells fresh

within the community. The milk has become a staple for many D’Edward Village residents who appreciate its quality and natural taste.

His herd also includes several young bulls, which he raises primarily for meat. Once they reach a live weight of about 280 to 300 pounds, he sells them to local butchers or buyers from as far as Essequibo at a rate of $500 per pound. He expressed his pleasure with the quality of animals he now produces for beef production, which allows him to negotiate with potential buyers without any hassle.

In addition to his thriving cattle operation, Thomas’s farm is a vibrant ecosystem of domestic animals. He rears horses — used mainly for managing cattle in the backlands — as well as pigs, sheep, goats, ducks, chickens, and turkeys. His yard is also home to a few beloved cats and dogs, which he regards as part of the family.

He currently owns fifteen horses, all in excellent condition and well-kept in his stables. Every inch of his property is utilised to the fullest, reflecting his meticulous care and love for animals.“I treat my animals like my children,” he said with a smile. “They provide for me, so it’s only right that I take good care of them.”

With a warm smile and glee in his voice, Thomas credited much of his recent success to the technical support and regular farm visits by GLDA Region Five Livestock Extension Officers and Mr. Sohan, GLDA Region 5 AI Technician, who have assisted with animal health, feeding regimes, and genetic improvement strategies. He also participates in the agen-

cy’s Traceability Programme, which monitors livestock farms and animals using tags, record-keeping, and active farm surveillance to ensure food safety and disease control.“The traceability system helps me monitor my progress and gives the consumers the confidence that our local meat and milk are safe for the market,” he said. “It’s a good thing for both farmers and consumers.”

Thomas’s decades of experience — gained from working on large cattle ranches, attending training workshops, and exchanging knowledge with fellow farmers — have made him a respected mentor within the livestock community. Although his children have chosen different career paths, he continues to pass on his knowledge to younger farmers in D’Edward who share his enthusiasm for agriculture.

Despite the modernisation sweeping through D’Edward Village, Mr. Thomas remains deeply connected to the land, the animals, and the traditions that have defined his life. For him, the preservation of livestock excellence is more than just farming as an occupation — it is a lifelong passion and a family legacy. His integration of modern genetic technologies like artificial insemination with traditional livestock rearing practices demonstrates that science and heritage can coexist harmoniously in shaping Guyana’s agricultural future.“I’ve seen farming change over the years,” Thomas reflected. “But one thing stays the same... if you love your animals and take care of them, they will take care of you.”

or St George’s Cathedral. Those are common things that you see. But self-expression is on a totally different level — it’s like poetry and art,” he said.

Like so much other great art, Sameer’s newest collection was inspired by loss and grief. After losing several family members, tragedy struck again when his home and much of his art were lost in a fire.

While abroad last August, Sameer received the gut-wrenching news that his home had been reduced to ashes — his business and more than 70 pieces gone. Although he considered staying overseas and starting anew, he made the bold choice to return home and rebuild.

“The fire happened on August 19. I was supposed to come back in August, and I had to extend my stay until September 16. I wasn’t sure if I was trying to stay abroad — I was getting some opportunities to stay — and then I was thinking, I might stay here,” Sameer said. “But I told myself, I could go back home and start to rebuild, see what my country has to offer, and help me with. I decided to make that bold move and come back home.”

Sameer’s rebuilding could be summarised in one word: Elysium. The exhibition, slated for November 14 to December 15, is a profound, personal showcase featuring much of his new work inspired by loss, grief, and rebirth.

“Looking back at the previous pieces that I was accumulating — most of it was portraits and sceneries and so on. This fire actually kind of awakened a part of me. I always loved abstract. My idea of having an art gallery in the past was more of the fact that I always saw people do portrait forms or sceneries, and I was kind of adapting to it,” he stated.

Sameer says his art has changed. Backed by the same creativity, his work now seeks to be more unique and powerful, urging onlookers to feel emotion.

“When I really sat and thought about it, I was like, I don’t have to do the most common thing like everybody else. I want it to be different. I want it to be all me. It must be a representation of a different part of me,” he said.

And he says that is what Elysium is all about.

“Elysium speaks of some-

thing sort of fantasy and imaginative. So I looked up this theme and I was like, you know what — Elysium, that’s what it’s going to be. It’s going to be all the things that you could imagine and think when you look at the piece,” he explained.

Elysium will feature around 50 pieces, each bold and emotive in its own way. Giving some insight into

what exhibition-goers can expect, Sameer shared: “Some pieces take the form of three pieces to conclude one piece. And then there are others based on the shape of the canvas — one piece in particular is a collection of eight small pieces. There’s a lot of diversity happening there.”

For Sameer, Elysium is a dream materialised and a goal long held since 2008, when

his first piece was exhibited at Castellani House. More importantly, he hopes that his exhibition will inspire other young artists to see their talent as a viable career, not merely a hobby.

“Over the years, I’ve seen a lot of artists struggle with their art. I’ve seen a lot of good artists put away art for some sort of career. I always believe that we should

be able to capitalise on the things that we love to do,” he said.

“I think a lot of young artists should put their all into what they’re doing. Turn your struggles into steps and pedestals that you could climb on. It doesn’t matter how many times you fall — what counts is how many times you actually get up.”

stepchildren, and his friends had much to say.“A father who became a stranger,” her brother stated, an edge of bitterness in his voice.

Sarah squeezed his hand lightly. “It’s not easy to accept, but I guess that was our fate.”

She had embraced quiet courage as she grew older and practised thoughtfulness for whatever little they had,

for she believed in her heart that one day things would get better.And they did.

“We survived,” she said to her brother. “We did great without him — but at the end of the day, he is still our father, so we will pay our due respects.”

He sighed and squeezed her hand back with a little wry smile. Sarah understood why he was bitter — because

he never had a father figure. He had to grow up without that support and encouragement; as a result, he lost interest in cricket, something he had once been passionate about.“You win some and lose some,” he said, trying not to show his hurt and disappointment.

She sighed deeply as a gust of wind shook the tree limbs, and the drying leaves

fell over her on their way to the ground.

Though her heart was grieved, she saw the pure beauty of nature around her. That was when tears filled her eyes, and she cried for every impactful moment she had lived through in life.

She wiped her tears and, after a long while, gathered up some dry leaves and took them to her father’s resting

place. She held her arms up and let the leaves fall slowly from her hands over his headstone.

“I leave for you something of beauty — the simplest things in life. Sorry, I don’t have many memories of you to cherish. That would have been nice, but you never came back.”

A knot formed in her stomach as she continued to speak softly. “I want you to know that I lived with hope that you would return — but after years passed, I stopped hoping. Now I’m standing at your grave.”

She took a deep breath to say her final goodbye and

saw the glimpse of a figure through the trees. She took two steps backwards; the figure, standing in light mist, turned — and she gasped. She froze, her heart racing, as the figure slowly faded away, enveloped by the mist. She took a few deep breaths and said, “Go rest in peace, dear Dad. One day, I will return to visit your grave, for it’s all I have of you.”

Sarah returned home. A dry leaf she had brought with her, she kept in a glass frame, and beside it, a portrait she had sketched. It was the face of the man she had seen in the mist at the cemetery — her father.

an important part of its literary heritage.

Then there are those whose neglect seems harder to explain — writers like O. R. Dathorne, Eric Walrond, Peter Kempadoo, and Zee Edgell. These are authors who wrote with clarity, imagination, and purpose, many of them published by major international houses. And yet, despite critical recognition at various points, their work has not achieved lasting traction in either academic or popular literary canons. A lack of consensus remains as to why certain writers fail to transcend their time or geography.

In the case of many of the women profiled in this collection, domestic responsibilities appear to be a recurring reason for their literary obscurity. The demands of

childbirth, childrearing, and family life often interrupted or curtailed their creative output. Political involvement, too, could overshadow a literary career — as it did for Elma Napier of Dominica, whose public service played a major role in how she was remembered, or not remembered.

Lost and Found offers both a scholarly and accessible survey of these writers’ lives and works. The biographical sketches, while brief, are often the most comprehensive records we have of these individuals.

Donnell’s project is an invaluable one: it not only revives lost voices, but it also invites readers and scholars alike to reconsider the mechanisms of literary remembrance — and forgetfulness.

Welcome, dear reading friend. Reading comprehension skills hinge on your ability to pull explicit or implicit information from a text. Sometimes you need prior and independent knowledge to understand a deeply implicit fact in the matter; but otherwise, you grasp an implicit fact through other clues in the text. A fact that is not implicit is explicit and outrightly stated.

It has no hidden connotations and no room for misunderstanding. It is easier to score on recognising explicit facts. Be knowledgeable.

Love you.

Understanding facts in reading

Reminder: To understand facts in reading, we address those obtained from reading a text. To make sense of the text, we connect with facts like: i) those that involve identifying verifiable information, ii) those that are distinguished from opinions, and iii) those that require comprehension strategies to be connected. Facts are objective statements. They are proven true or false through evidence in the text. Opinions are subjective statements of beliefs, feelings, tastes, or interpretations of the person(s) proffering them. But there are pure

opinions that cannot be proven true or false. Also, some opinions are based on facts, and others are predictive. These last-mentioned categories can be proven right or wrong through evidence.

Read carefully the passage below and then answer all the questions that follow.

The village appeared to be at the end of the world, and it seemed as though each day was a deliberate effort. Dawn came slowly; the cold air flowing off the sea, the smell of fish and the wet smell of the nets fading away as the light climbed up the sky. Midday brought a blazing heat that softened the raw pitch with which the road was made in the village.

Cars parked too long out

November 9th, 2025

in the heat sank slowly, tyredeep, into the soft asphalt, and the hot sun and the heavy air filled with the smell of cooking saw the huge red ball of the sun dipping across the sky into the sea, leaving glorious and stunning sunsets that coloured the bay red, burning off the hulls of the tankers that tied up against the long oil-jetty, matching the flares of the oil refinery in the distance as the excess gas was burned off. The evening smell was that of oil.

There was death in the village, but that death was not a final horror, it was not the heart-rending, bitter cry of a sudden and unexpected grief.

No! It was the sad, lingering, whimsical death found in the eyes of broken,

A man, Sir, should keep his friendship in constant repair.

Boswell’s “The Life of Samuel Johnson” p.300, 1755

old men as they patted young boys on the head and considered the foolishness of youth; it was the empty death found on abandoned coasts at the end of small islands dwarfed by the hugeness of the Atlantic; it was the hopelessness of this backwater village, swept clean of talent and vitality, missed and ignored by a political turmoil sweeping the city, dependent upon a poor stony earth and dwindling oil. Death here was a vision of a hopeless future.

(Noel Woodroffe, “Wing’s Way”)

1. Give the meaning of each word-group: the village appeared to be at the end of the world; the cold air flowing off the sea; heavy air … drove people into the shade; burning off the hulls of the tankers; matching the flares of the oil refinery; old men … considered the foolishness of youth.

2. In paragraph 1, the writer describes times of the day. What times of day are they?