Baracara: A Haven of History and Culture

SOME many years ago, Africans who escaped slavery, scattered themselves across Guyana and formed settlements where they hoped to start a fresh life, one such settlement, Baracara, can still be found on the Canje River, in Region Six East Berbice-Corentyne.

Baracara also known as ‘Wel te Vreeden’ or ‘New Ground Village’ is the home to the direct descendants of the Africans who led the historical 1763 Berbice Slave Revolt; as such it is referred to as a Maroon settlement.

In a recent ‘gyaff’ with this publication, chairman of the Community Development Council (CDC) Marshall Thompson shared a brief history of his home village.

As told by his elders, Thompson disclosed that in the early 19th century, a group of escaped enslaved Africans settled in Baracara, occupying both the east and west banks of the river.

Baracara is the only Maroon village in Guyana.

“Mostly black people live here; slave decadents and we

are a self-support people.”

With a small population of just over 100 households, the residents of Baracara considered themselves to be one big family, supporting each other in their everyday joys

and sorrows.

The economy of the village is based on subsistence farming and logging. The village has a health centre and a primary school, but no secondary school. Most of

the children leave the community for secondary school once they’ve completed their primary education.

Life in Baracara, Thompson said, is ‘quiet and simple’.

The people of Baracara live humble lives and still rely on the teachings and traditions passed down to them by their Maroon ancestors.

Thompson like most villagers grew up hearing

varying anecdotes of Cuffy and the Berbice Rebellion and according to Thompson, Plantation Magdalenenberg was located just a few miles from Baracara and traces of its existence still remain.

“If we check in some of our backdams, we see beds that were cultivated by the slaves; beds that they planted cocoa on. They were planting in different areas along the river, and that’s how they ended up settling in various places along the river.”

A GLIMPSE INTO HISTORY

It was in February 1763 on the very same Canje River more than 2,500 enslaved Africans working here revolted against the outright injustices meted out to them. At the forefront of this massive revolt was Cuffy, the Akan man brought to Guyana to work on the sugar plantations.

Kofi Badu or “Cuffy” as he is better known, was a ‘house slave’ at Plantation Lilienberg, another plantation

Continued on page 3A

Baracara: A Haven...

From page 2A

on the Canje River. According to historical records, on February 23, 1763, when the catastrophic events began in the Dutch colony of Berbice, it was Cuffy who managed to organise the enslaved persons into a ‘military unit’.

By his side was his lieutenants Atta and Akara.

Together, the Berbice slaves overran plantation Magdaleneburg, removing the colonial masters, and taking their freedom.

Cuffy had planned the revolt just as two shiploads

of people from Africa had arrived at the docks, which significantly increased the number of Africans in the fight to overthrow the 346 colonial masters.

News of the rebellion spread like a forest fire on a hot day and soon enough uproars began at plantations across Guiana and in other Caribbean nations such as Barbados and Jamaica.

Within one month, Africans were in full command of most of the plantations in Berbice. Cuffy then declared freedom for the enslaved Af-

ricans, and they managed the plantations for almost a year. Unfortunately, after the plantations were reconquered by the Dutch, Cuffy shot himself in the head, in a bid to never submit to his enslavers. Although their freedom did not last due to Dutch reinforcements arriving by ships with heavy machinery and artillery to recapture the slaves, Cuffy left a lasting legacy, one that the people of Baracara share with pride.

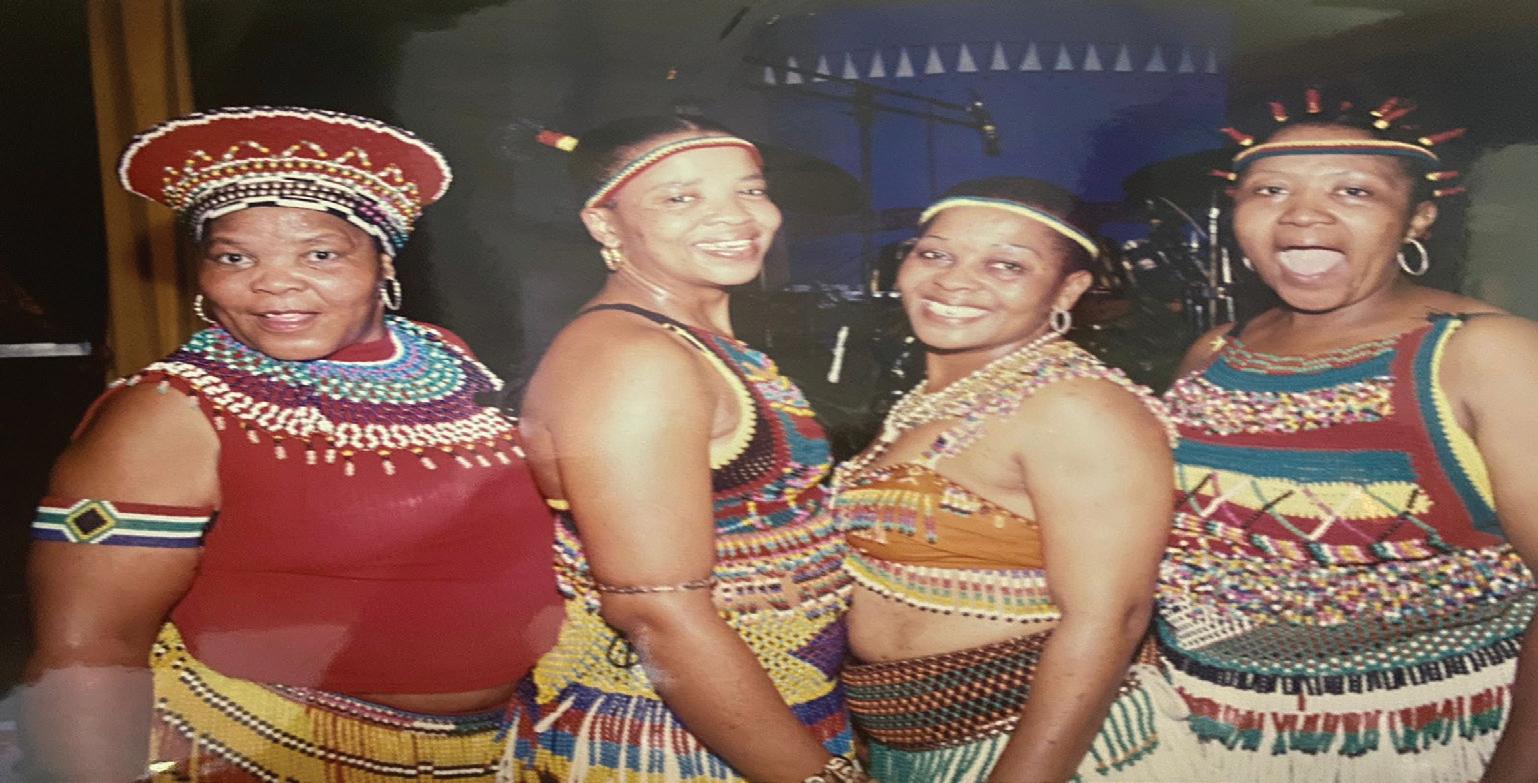

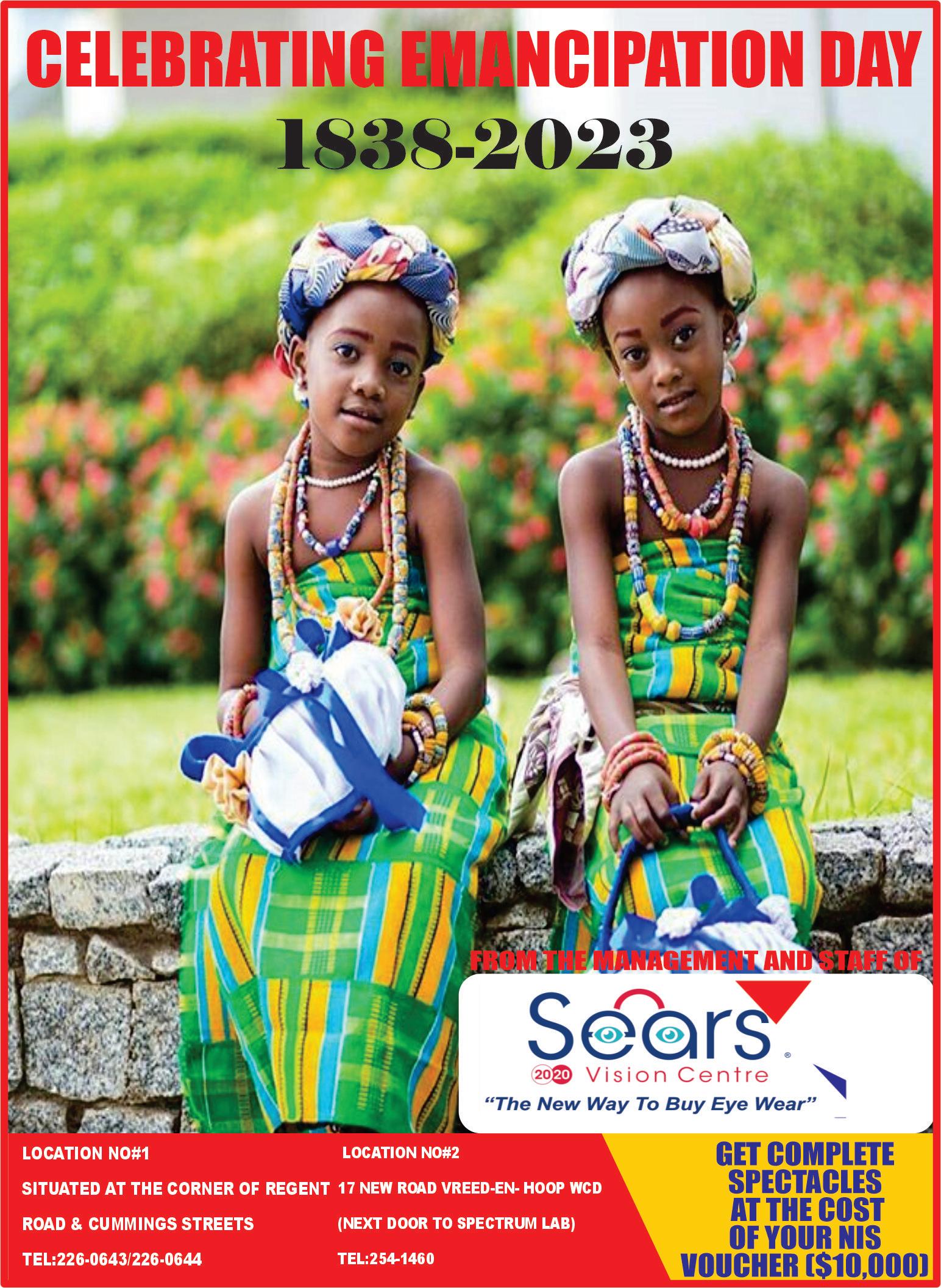

Emancipation celebrations throughout the years

Emancipation celebrations throughout the years

A journey through history

— the Caribbean's slave trade and Emancipation

By Faith GreeneON this day, 185 years ago, thousands of African people from Guyana and other Caribbean nations gained their freedom from the chains of slavery that had kept them bound for centuries.

They were finally free to determine what was suitable for them and what was not, all within certain limits of course.

The then-enslaved Africans were victims of what some historians described as one of the world’s largest crimes committed against a group of people.

The Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), in a recent publi-

cation titled The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade (2022), labelled this crime as one of abduction and abuse that has altered the global landscape and created a legacy of suffering and bigotry, all of which still exists today.

The 1400s

Trekking back to the tales of centuries ago, the Europeans in search of wealth sent several ships and armed militia to exploit new lands, many of which had already been occupied by Indigenous peoples.

These lands or territories were known then as ‘the Americas’ and the home to extraordinary natural resources which provided great opportunities

to gain power and influence for Portugal, Spain, Great Britain, France, Italy, Germany, and Scandinavian nations.

History tells us that these lands produced an abundance of gold, sugar and tobacco all of which were sought after by the Europeans to generate wealth.

They first attempted to enslave the Indigenous peoples and they were met with much resistance, but in their determination to extract wealth from these distant lands, they sought labour from Africa, launching a tragic period of kidnapping, abduction, and trafficking that resulted in the genocide and enslavement of millions of African people.

THE SOCIAL PYRAMID

According to the Guyana Chronicle’s archives, slave societies in the Amer-

icas were formed according to power, prestige, privilege, and colour. At the top were the Whites, which comprised government officials, plantation owners, managers, merchants, clergies, small shopkeepers, craftsmen, and indentured servants.

At the middle were Blacks and free Coloureds, who were classified as Mulatto, Quadroon, and Sambo. This was a sandwich group that served as a social lubricant between the highest and lowest layers of Guyana’s slave society. And at the lowest layer were the enslaved Africans, who were further stratified into the fields, house, skilled and urban slaves.

Each layer of stratification was hierarchically organised along firm boundaries. The structure of slave society was shaped like a social pyramid.

David Lambert’s, ‘An Introduction to the Caribbean, Empire and Slavery’ published in 2017, states that the Europeans came to the Caribbean in search of wealth. The Spanish had started out looking for gold and silver, but there was little to be found. Instead, they tried growing different crops to be sold back home.

After several unsuccessful experiments with growing tobacco, the English colonists tried growing sugarcane in the Caribbean. This was not a local plant; however, it grew well after being introduced. According to Lambert, several people in Europe wanted the products of sugarcane, and as a result, those ‘planters’ who grew it became very wealthy.

Lambert, a Caribbean History Professor at the University of Warwick, in the United Kingdom penned that the spread of sugar plantations in the Caribbean created a need for workers. Planters turned to buying enslaved men, women and children, brought from Africa.

It is believed that five million enslaved Africans were taken to the Caribbean.

“As planters became more reliant on enslaved workers, the populations of the Caribbean colonies changed, so that people born in Africa, or their descendants, came to form the majority. Their harsh and inhumane treatment was justified by the idea that they were part of an inferior ‘race’. Indeed, complicated ways of categorising race emerged in the Caribbean colonies that placed ‘white’ people at the top, ‘black’ people at the bottom and different ‘mixed’ groups in between. Invented by white people, this was a way of trying to excuse the brutality of slavery.”

THE UPRISING OF REBELLIONS IN GUYANA

In Guyana, the Dutch European established the settlement, British Guiana in order to trade with the Indigenous people, however, due to the competition with other European countries to gain territory, it soon became a commercialised base and by the 1660s, more than 2,000 slaves had been brought to the Dutch territory to work on plantations.

According to the textbook, Social Studies Made Easy, they had lured Africans from several countries in Africa and brought them to then British Guiana to work on sugar plantation as slaves, much like what happened in several Caribbean countries during that period.

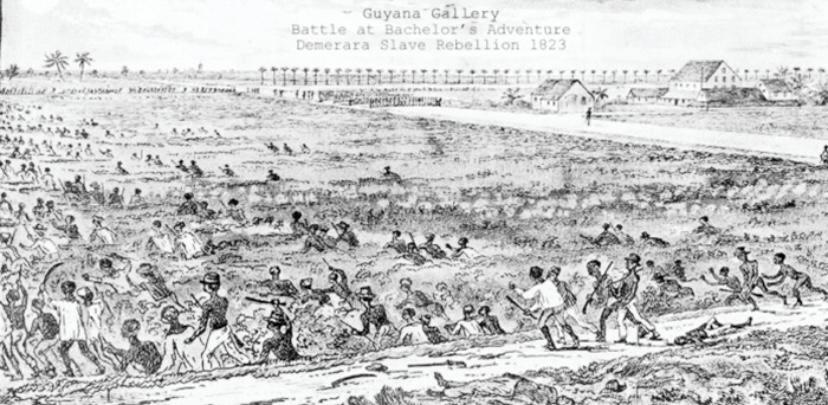

By 1763, a slave revolt began on two plantations on the Canje River in Berbice by a West African slave named Cuffy. This was due to the harsh treatment of slaves by the Europeans which additionally caused many slaves to commit suicide, run away, and eventually give rise to several rebellions.

Other persons involved in this rebellion were Akara, Atta, Accabre and Gousarri. Unfortunately, this rebellion failed because of disunity among the Africans. Cuffy committed suicide, and the other leaders were defeated. Another rebellion arose on Plantation Le Ressouvenir in 1823.

According to the textbook, Quamina and his son Jack Gladstone were held responsible for this uprising, which proved to be unsuccessful after the leaders had discouraged the Africans from being violent.

Quamina was shot, and

Continued on page 7A

From page 6A

Gladstone was sentenced to deportation and taken to St. Lucia where he was sold into slavery.

Rebellions continued across the Caribbean with

uprisings in Barbados, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago and other territories.

Emancipation however came years later on August 1, 1838, after people like Thomas Buxton, Thomas

Clarkson, Granville Sharp, George Canning, James Ramsay and William Wilberforce campaigned to abolish slavery. While slavery was abolished in 1834, slaves still had to work

on plantations, but were paid small wages for their labour.

Some Africans, like Damon, refused to work and in 1834, he started a protest which resulted in him being

hanged.

After their emancipation, the Africans began to buy plantations. The first plantation bought by the freed slaves was plantation Northbrook, which

was later renamed Victoria. The Africans earned a living by practicing peasant farming of crops such as rice for example, and trade work (masonry, carpentry, plumbing and handcraft).

ACDA celebrates 30th Emancipation festival today

By Shaniya Harding

By Shaniya Harding

PERSONS will enjoy food, dance, storytelling, music and much more today at the National Park, Georgetown, where the African Cultural Development Association (ACDA) will host its 30th Emancipation fes-

— annual event to reconnect Guyanese to their roots, celebrate culture and tradition

tival.

At a press conference on Monday at the Pegasus Hotel, ACDA official Aisha Haynes disclosed that this year’s event will not only feature traditional activities but new excitements.

“We open at 10 am and you’ll have a lot of different experiences,

and have a lot of food. Come out and watch the cook-up competition. We have a lot of activities for the children. We have storytelling, face painting and a bouncy castle. We have three stages, tarmac and centre stage. The centre stage starts at 10 am and runs until five pm, while the tarmac

stage starts at 2 pm.”

This year’s festivities will also feature Ghanian Afro-beats star, Livingstone Etse Satekla, better known by his stage name “Stonebwoy” and award-winning reggae family band Morgan Heritage.

Teasing what patrons can expect from their

performances Gramps

Morgan of the Morgan Heritage Group said he hopes the band’s production at the festival will connect Afro-Guyanese to their ancestorial roots.

“Our song called ‘Africa, Jamica’ was to wake up everyone and make them understand that Africa is calling us and it is changing.”

Popularly known for their conscious lyrics and reggae rhythms, the elder Morgan said that the band’s work is a small example of what can be accomplished by collaborations between Afro musicians from all around the world.

“On our trips going to Africa, we make it our duty to reach out to the local artists which is how we met Stonebwoy.”

Also present and sharing similar sentiments was the Ghanaian

musician ‘Stonebwoy’, who similarly expressed the significance of celebrating emancipation alongside the Guyanese populace.

“The uniform of all Africans is our skin colour,” he said.

Both the Morgan brothers and ‘Stonebwoy’ revealed their intentions of returning to Guyana to celebrate similar festivities.

Gramps Morgan added: “It is time black people around the world wake up and feel beautiful. We are beautiful naturally. And even next year if we are not booked, I would like to attend this event.”

Gates will be open from 10 am, children will be admitted for a fee of $500 while adult tickets cost $1,500 before 5 pm and $2,000 after 5 pm.

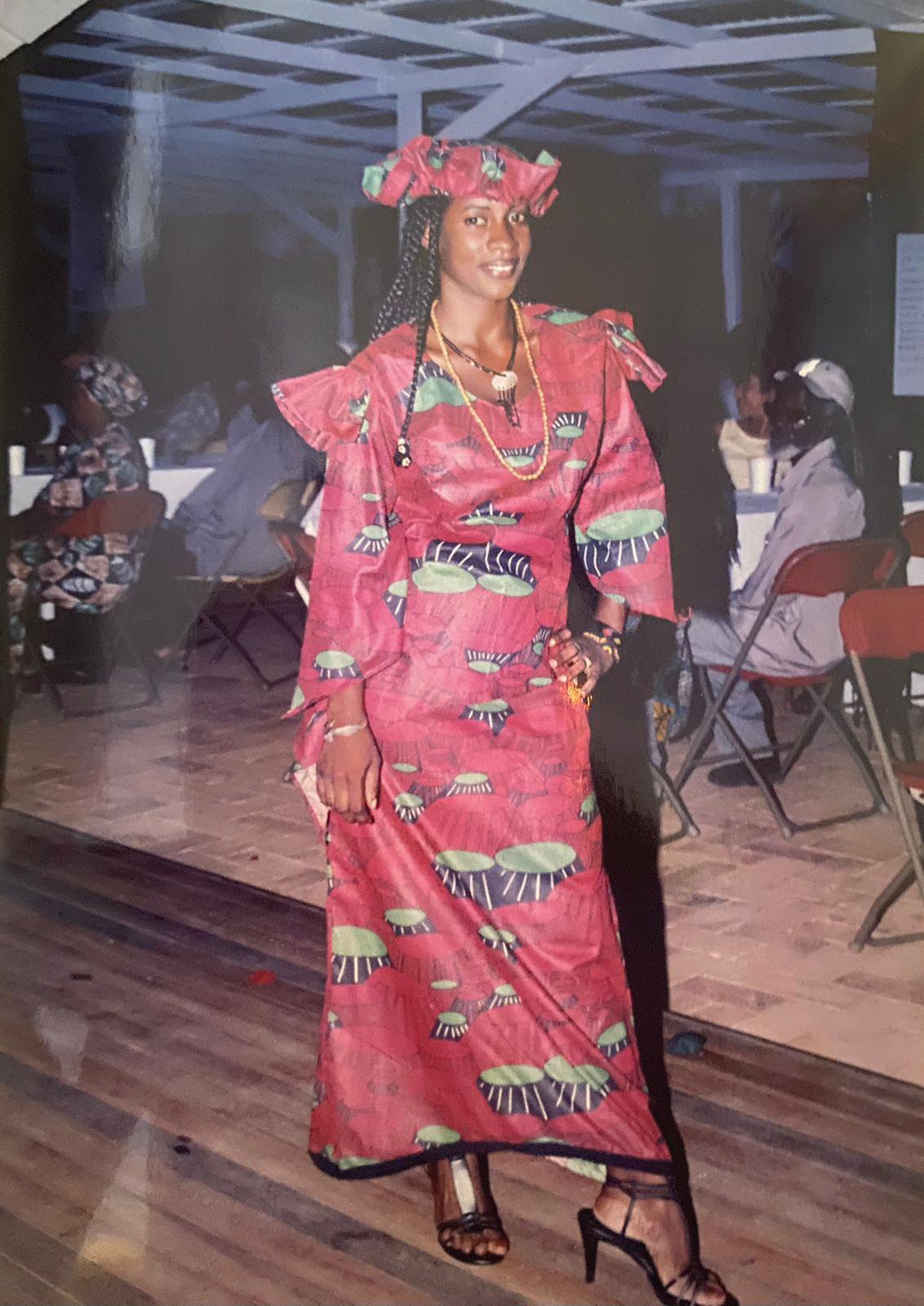

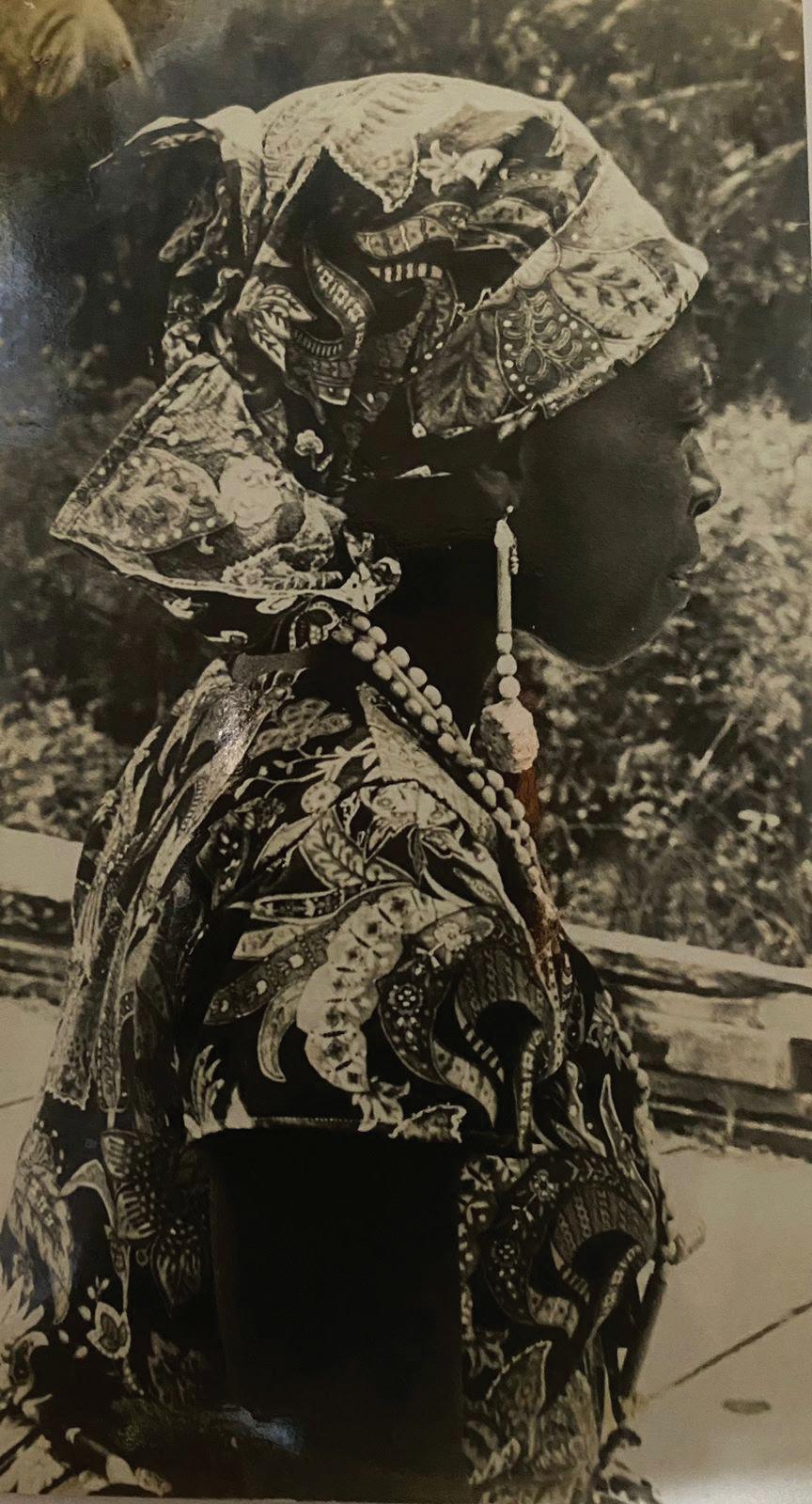

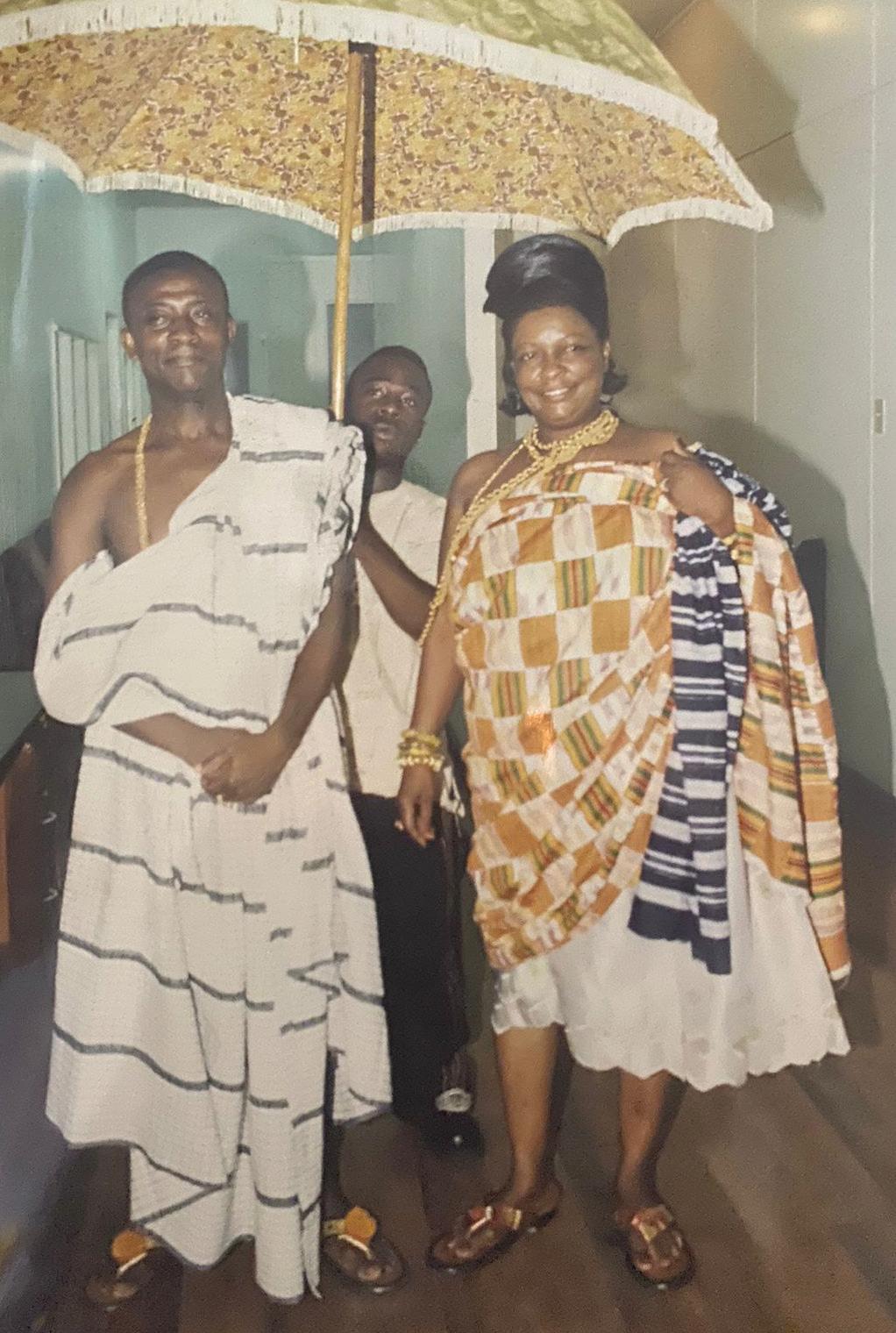

More than just clothing — The revolution of African garments

By Naomi ParrisFILLED with vibrant threads of colour, uniqueness and history, African clothing is full of life, telling the stories of the past, present and future.

Varying from colourful prints to embellished symbols, traditional African garments depict a turbulent past

of trials and triumphs. In Guyana, however, while African clothing does not stray from its traditional roots, it does have a modern flare. Some traditional clothing worn in Guyana include the Dashikis and Kaftan dresses, which are usually worn during Emancipation Day festivities on August 1st.

THE TRAVELLING HISTORY OF FABRIC

The evolution of clothing in African history is very difficult to trace due to the lack of written word and actual historical evidence. What is known and has been pieced together were handed down from word of mouth (oral history), theatre, movies, masquerades, art and arte -

facts which show sculptural representations of clothing. Research revealed that clothing was not generally a necessity in many African nations, due to the warm and hospitable climate. Many tribes in fact did not wear much at all. The men wore just a loin cloth or apron and the women wore wraps

Continued on page 12A

More than...

From page 11A around their waist or breasts, often adorning the rest of their bodies with scarification and paint ochres.

Bark cloth, furs, skins and hides were mainly used for these first forms of clothing.

SIGNIFICANCE

While the significance may not be the same for Guyanese, different tribes throughout the African continent pride themselves on their national dress. These varied styles, fabrics and prints play an integral role in fashioning an entire identity, community and tribe.

It’s not just a fashion statement piece; African clothing often reflects the society in general as well as the status of individuals or groups within that community.

MODERN AFRICAN CLOTHING

Today, while fashion has been influenced heavily by foreign cultures such as the

African clothing has, throughout the years, evolved, with newer styles dominating the local fashion scene

colonial impact or popular western dress code, traditional dress is worn by millions of people for both ceremonial occasions and for everyday wear.

With the most popular being the Ankara fabric. This vibrant material with rich,

colourful patterns in recent years has become very trendy and even made its way to luxury designer brands.

Ankara has gone beyond being merely a piece of attire. To date, it is being used as a base for hats, handbags, shoes and all manner

of clothing, as well as décor items for the home.

Personal Wardrobe

As a lover of all things African, whether it be clothing, accessories or music, having pieces of my history embedded in my everyday life gives me a sense of pride.

In Guyana the vibrant prints of African garments usually flock the local markets as celebrations for Emancipation are nearing. For me personally, these pieces of clothing are more than just for special occasions and events, as I incorporate pieces of these gems in my everyday life and so should you.

African clothing has been modernised and it ever so changes to fit the latest fashion trends, while still staying true to its unique style. Today, African clothing is much more than just the traditional Dashiki. It comes in various colours, designs, materials and styles with each garment offering its own authentic look and identity.

Cuffy and Damon – the brave African men who must never be forgotten

British attempt to instill fear in the slaves, their determination and strength led to one of the Caribbean’s first and largest slave rebellions. Led by a house slave named Cuffy (or Kofi), the 1763 revolution is recorded as a pivotal move in the abolition of slavery.

Creating a ripple effect, Cuffy, with his two lieutenants, Atta and Akara, by his side, led 3,833 enslaved Africans to their freedom. Together, the Berbice slaves overran plantation Magdaleneburg, removing the colonial masters, and taking their freedom.

Cuffy had planned the revolt just as two shiploads of people from Africa had arrived at the docks, which significantly increased the number of Africans in the

fight to overthrow the 346 colonial masters.

News of the rebellion spread like a forest fire on a hot day and, soon enough, uproars began at plantations across Guiana and in other Caribbean nations such as Barbados and Jamaica.

Within one month, Africans were in full command of most of the plantations in Berbice. Cuffy then declared freedom for the enslaved Africans, and they managed the plantations for almost a year. Unfortunately, after the plantations were reconquered by the Dutch, Cuffy shot himself in the head, in a bid to never submit to his enslavers. Although their freedom did not last due to Dutch

Continued on page 14

STRIPPED of their names, religions, cultures, and identities, over three million Africans were shipped across the Atlantic Ocean in what was known as the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Stolen from their motherland, they were auctioned off and sold as slaves to British-owned colonies to work on plantations in the Caribbean.

By the 1760s, there were about 15,000 slaves toiling endlessly across the three colonies of the then British Guiana – Essequibo, Demerara and Berbice. Eventually, the slaves had become exhausted of living a life of torture and captivity, and so, several of them banded together and began plotting and planning their escape. Several attempts were made, but the African

slaves remained shackled to the inhumane treatment they received on the plantations. Moreover, their attempts to escape in the first place were heinously rewarded as some were flogged, while others suffered amputation or were killed.

CUFFY AND THE RIPPLE EFFECT

However, despite the

Cuffy and...

tory as the first major revolution by Africans in the western hemisphere and influenced several other revolutions in the west, including the Haitian revolution led by Toussaint Louverture.

To date in monumental form of Cuffy adorns the Square of the Revolution, in the capital city of Georgetown.

DAMON AND THE FALL OF LA BELLE ALLIANCE

After Cuffy’s demise, the fight for freedom did not stop. Eventually, the African slaves gained the rights to liberation on August 1, 1834. However, the road to freedom was no smooth sail, because, despite having the Emancipation Act passed in 1833, the now freed Africans still had to fight to be treated fairly.

They were transitioned into a period of apprenticeship and continued to work with their former masters for miniscule wages. That did not sit well with the exslaves who had a different vision of what life would be like after freedom.

reinforcements arriving by ships with heavy machinery and artillery to recapture the slaves, Cuffy left a lasting legacy, one that inspired other slaves to fight for their freedom and to never give up until they were free.

The February 23, 1763 Cuffy-led revolution was recorded in European his-

What started the fall of La Belle Alliance at Essequibo was a problematic move by the owner of Richmond sugar plantation, Charles Bean, who stirred up trouble by killing the pigs and cutting down the fruit trees that the former slaves had been rearing for their livelihoods. His excuse for the destruction of the ex-slaves’ properties was that their pigs were destroying the roots of his young canes.

In rebuttal to Bean’s

destruction, an ex-slave named Damon, led a protest which resulted in some 700 apprentices downing their tools in support of Damon’s cause. On August 3, 1838, they protested the apprenticeship scheme. The following morning, the freed slaves were more than surprised, and became angry when they were ordered by their former masters to return to work; however, the protests continued and by August 9, the labour situation had worsened with ex-slaves from Richmond to Devonshire Castle gathered in the Trinity Churchyard at La Belle Alliance to stand beside Damon. Governor Smyth addressed the workers at Plantation Richmond, telling them that the apprenticeship period was still in force and they should go back to work. He arrested the leaders of the peaceful demonstration. Considered the “captain” and “ringleader” of the unrest, Damon was hung in front of Parliament Buildings at noon on October 13, 1834. Although his attempts then were futile, the fight for freedom did not end with him. His resilience influenced many other ex-slaves and served as a warning to other plantation owners that the Africans were a strong and brave people. Also in monument form, the statue of Damon stands next to the Anna Regina Town Hall on the Essequibo Coast. These heroes fought the greatest for us all to be able to experience the freedom and the Guyana that we do today.

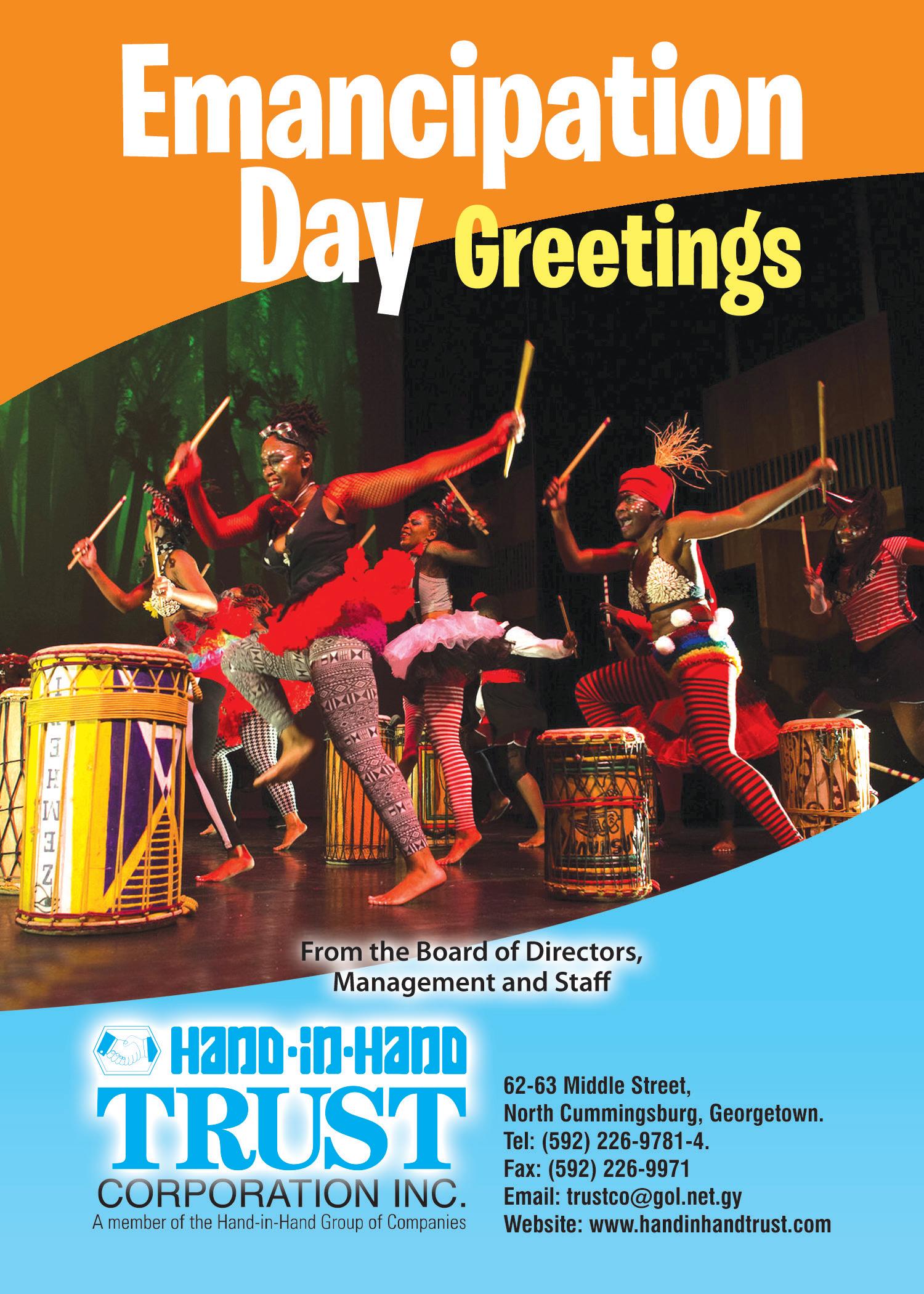

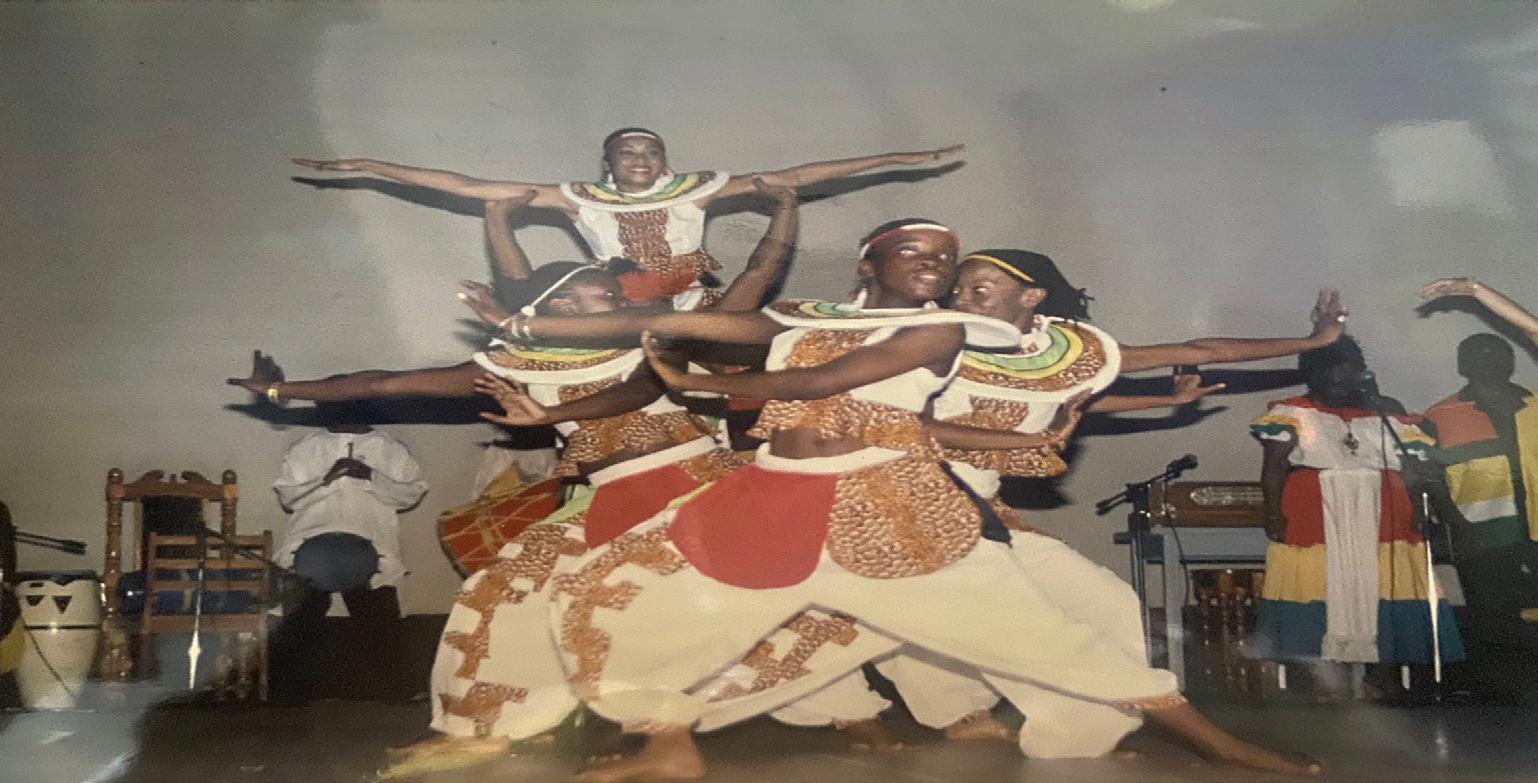

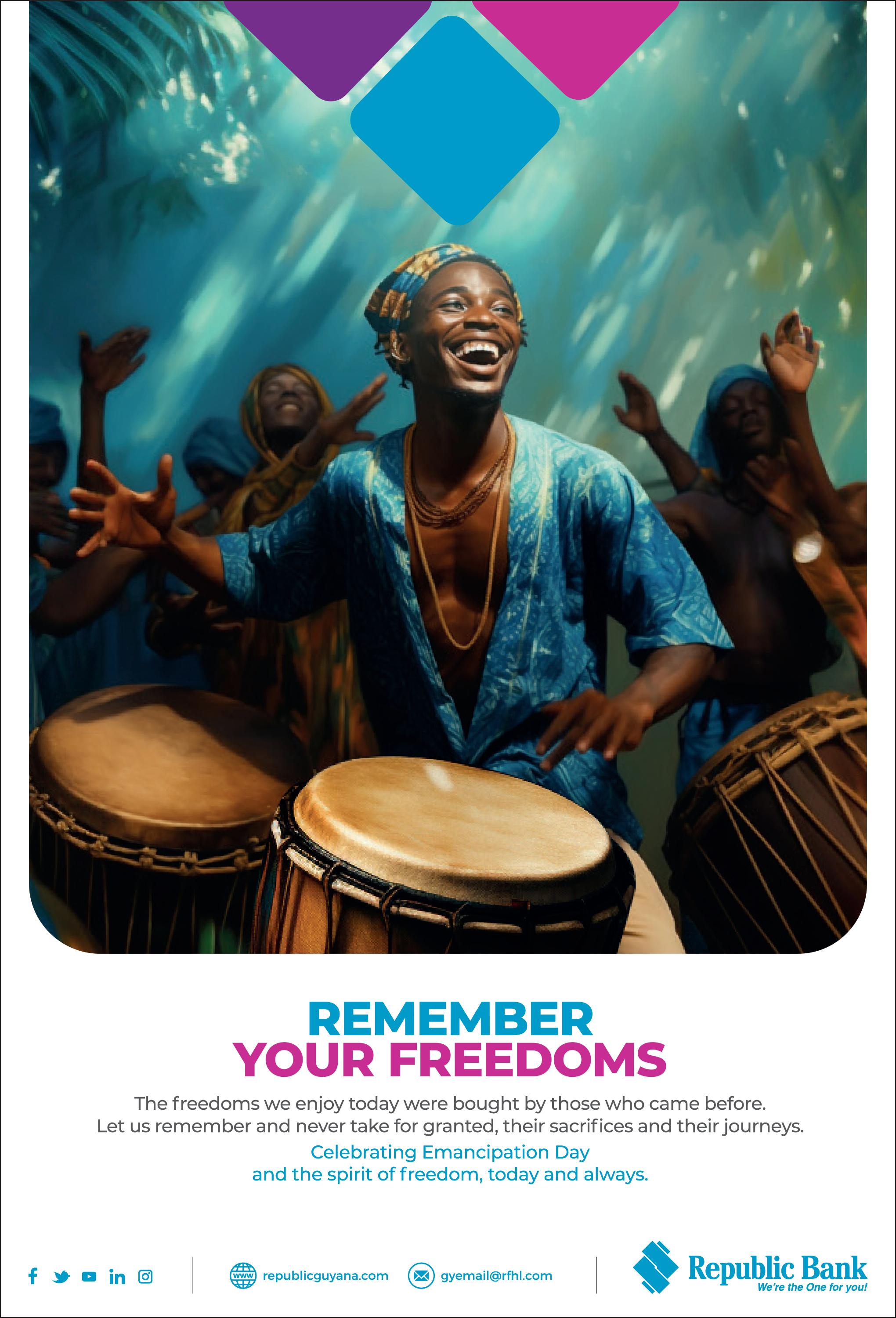

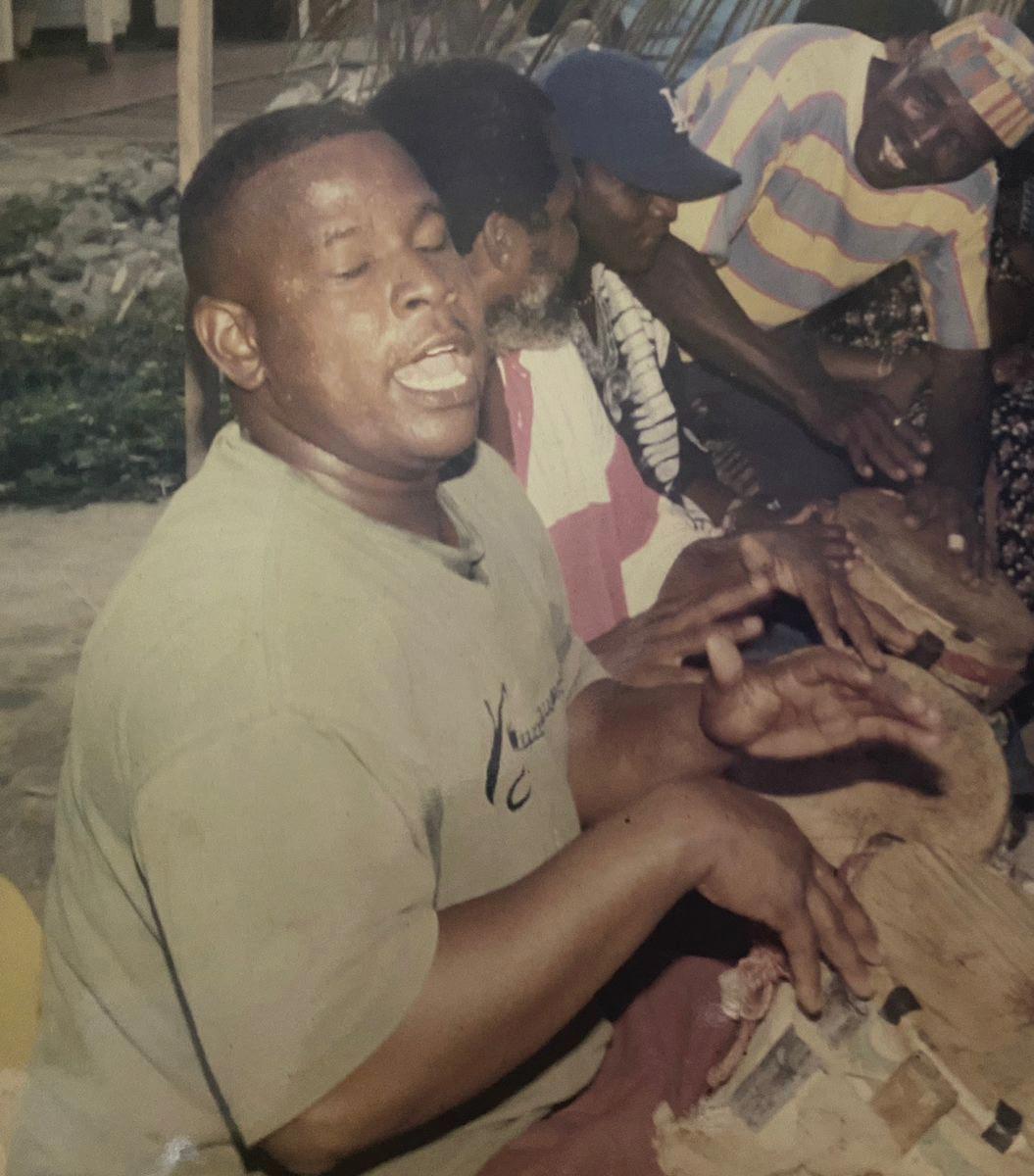

DANCE and music are common forms of expression in Guyana and many other parts of the world. In Guyana, dance and music are heavily influenced by the country’s multicultural society.

In Guyana particularly, people of African descent, who are connected to the traditions of old, use dance and music to commemorate important social and religious events.

One of these many festivals is Soiree, a tradition held yearly in celebration of the Emancipation of enslaved Africans in Guyana.

Similar to ‘Queh Queh’, a pre-marital celebration, Soiree is the gathering of family and friends in celebration.

The joyous occasion is celebrated with drumming, chanting, and Shanto dancing, used to invoke the spirits of the African ancestors.

On the night of July 31 or even on previous nights before August 1, soirees are held in predominantly Afro-Guyanese villages along Guyana’s eastern coast.

Soiree: A festival of dance and togetherness

This cultural festival has its roots in the 1800s, and is indigenous to villages along the coast and banks of the main rivers that Africans bought when they were liberated from slavery.

Villages that have embraced this tradition even now are Hopetown, Ithaca, and Belladrum in Berbice; and Buxton, Victoria, and Bagotville in Demerara.

The village of Hopetown was bought by former enslaved Africans in the 1840s which is around the time the Soiree tradition emerged.

Today, drumming, marching and dancing would start around 18:00 hours on the eve of Emancipation in an area of the village called ‘Twenty-Two’.

The large crowd would disperse into groups to keep their separate libation ceremonies, while the main access road cutting through the villages is flooded with hundreds of Guyanese with their music sets, creating a party-like atmosphere.

Traditionally on July 31, there is a

Soiree: A festival of dance and ...

From page 15

thanksgiving church service at the village’s traditional church. At 22:00 hours, the villagers then head to the village koker for the libation ceremony.

They dance and mimic the sounds of the drums and other musical instruments.

Upon arriving at the koker, the participants sing as they “invite the ancestors to join the celebrations”.

When it is certain that the ancestors are “within their midst”, the celebrants move over to the community centre for a grand enjoyment.

At this time, the centre is filled with spectators, dancers, drummers and singers, as well as children.

At about 06:00 hours the following morning, the libation ends, but not the Emancipation celebrations! This continues throughout the day.

A packed programme, prepared weeks in advance, is started at about noon. The villagers gather at the centre of the village, once again, to witness the traditional concert.

This includes African dances and songs, skits, speeches, and, most importantly, storytelling.

This year Soiree celebrations will be in full swing after a three-year hiatus due to the COVID-19 pandemic.