INTENTIONAL IGNORANCE PSYCHOLOGY OF WILLFUL NAIVETE 6 AI HARMS

9

HABITATS

NEW TECH DAMAGES THE ENVIRONMENT

INTENTIONAL IGNORANCE PSYCHOLOGY OF WILLFUL NAIVETE 6 AI HARMS

9

NEW TECH DAMAGES THE ENVIRONMENT

3 4 5 6 8

International cinema broadens horizons

Community concerts and climate activism

The potential of Wolbachia in malaria prevention

Helios explores the role of human connection in fostering empathy

Black April prompts reflection in the Vietnamese community

9 10 11 Social media promotes overconsumption

AI usage imposes costs on the environment Politics and science: A historical interplay

Dear Reader,

Welcome to our long-awaited second issue of the 2024–2025 school year. Though printing delays pushed publication later than planned, we’re thrilled to finally share this collection. Each page is a reflection of the precision and creativity of student contributors in various grades and disciplines.

From international cinema that deepens cultural understanding to the Aeolian Piano Quartet’s profile, and from art that raises awareness about environmental issues to explorations of malaria, willful ignorance, and female friendship, this issue travels wide in the Arts. We commemorate the 50th anniversary of Black April, examine how book covers entice readers and question how social media and fast fashion shape consumption in the Culture section. Our STEM writers probe the politics of science and the climate concerns surrounding NFTs

— reminding us how curiosity drives inquiry across every field.

We hope one story is bound to challenge or inspire you. If you’re interested in joining the creative magazine, our community welcomes writers, artists and designers eager to grow, collaborate, and experiment in a supportive space that Vanisha Vig and Sarah Grupenhoff are curating as the next leaders!

This issue’s cover — crafted by visual arts editor Sarah Xie — gorgeously links our name to the themes within, a fitting emblem for an edition born of patience and persistence for the craft that connects us: journalism. Thank you for your support of our campus reporting. We hope you enjoy!

Your Editors-in-Chief, Sarah Grupenhoff and Sylvie Nguyen

EDITORS-INCHIEF

Sarah Grupenhoff

Sylvie Nguyen

LAYOUT DESIGNERS

Ella Nguyen

Vaani Saxena

Vanisha Vig

Ya-An Xue

VISUAL ARTS

EDITOR

Sarah Xie WRITERS

Donovan Carlson

Owen Cheng

Ellie Chang

Athena Gao

Evelyn Luong

Kabir Mahajan

Michael Matta

Ella Nguyen

James Ng

Ezra Rosenberg

Vaani Saxena

GRAPHICS

Sylvie Nguyen

Sarah Xie

Helios, Gunn’s art, culture and STEM magazine. publishes one color issue each semester. Join our staff as a writer, layout designer, graphics artist, or photographer by coming to our club meetings at lunch on Tuesdays in N-106. No prior experience needed!

In today’s world, the media we engage with shapes our biases and understanding of different cultures. However, international cinema continues to be undervalued and sidelined by Hollywood, making it difficult for audiences to access. Despite these obstacles, international cinema is capable of deepening our understanding of diverse perspectives, promoting a more empathetic and knowledgeable society.

One noticeable difference between the worlds of U.S. cinema and international cinema lies in the stories told. Hollywood productions frequently follow familiar formulas to appeal to the masses, often prioritizing spectacle over substance. On the other hand, international cinema delves into unique cultural experiences, social issues and unusual narratives. Films like these serve as windows into the realities of life in different societies, ultimately helping viewers further comprehend people’s experiences across the globe.

Beyond just providing good entertainment, international cinema also challenges viewers to engage with various complex themes as well as strikingly relatable narratives. Films like “Perfect Blue,” a groundbreaking Japanese animated psychological thriller, dissect the impact of media on personal identity — a theme that has universal relevance but is rooted in Japanese culture. On the other hand, Ingmar Bergman’s “The Seventh Seal” utilizes Sweden’s medieval history to explore existential questions of faith and death inspired by the works of the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard. A common thread between these films is that they are not afraid to intellectually challenge the viewer while creating an atmosphere that is immensely hard to escape. By prompting viewers to confront unfamiliar ideas and emotions, they

foster greater empathy and cultural awareness.

Despite all of this, international cinema remains largely inaccessible to many audiences. This is likely due to Hollywood’s dominance in global film distribution, which leaves little room for foreign films to gain widespread recognition. Streaming services have begun to expand their offerings, but the selection remains limited. Independent film festivals such as Sundance and Telluride, along with niche streaming platforms like Mubi and The Criterion Channel, play a crucial role in bridging this gap, providing a platform for diverse voices. Advocacy efforts, such as petitions for more diverse film catalogs, could further push for greater accessibility.

Sylvie Nguyen

Engaging with international cinema has been proven to have a profound impact even on a local level. Personally, I founded the International Cinema Club last August, a club dedicated to screening international cinema and subsequent discussion. This has allowed me to witness firsthand how films such as “Godzilla Minus One” entertain members while also educating them about the many hardships that Japanese veterans faced after WWII. Besides the club, individuals can and should contribute to a more inclusive and culturally aware environment by seeking out and supporting these films.

Overall, international cinema has the power to transform not only individual perspectives but society as a whole. Understanding and empathy are more vital as the world becomes more interconnected. By championing greater accessibility and making the effort to explore stories from around the world, we can help build a society where every voice is heard. The stories told on screen transcend borders — it’s time to press play and broaden our horizons.

—Written by Michael Matta, a writer.

Gunn’s Aeolian Piano Quartet strikes the right chord — not only showcasing the musical talent of sophomores Jamie Cheung on viola, Yaya Li on violin, Sophia Parang on piano and Vincent Tsai on cello, but also proving they can orchestrate their own success.

“I think one thing that’s very unique about our quartet is (that) we’re formed by students and we coach ourselves,” Cheung said. “Playing chamber music is an intricate art and sometimes you really need some guidance. (But) we give each other the guidance that we need to play music together.”

While most quartets are traditionally composed of either all string or all wind instruments, the Aeolian Piano Quartet sets itself apart with the addition of a piano. For Li, playing alongside a piano is special because it distinctly differs from when she plays in her outside-of-school orchestra.

said. “In my orchestra outside of school, the chamber music I play is only with strings, but with the piano, I think it’s a very different experience.”

Cheung expresses a similar sentiment about how Parang’s piano playing expands the ensemble’s sonic texture and dynamic range, bringing a contrast not found in traditional quartets.

“Usually quartets come in like saxophone quartets or string quartets, right?” he said.

and how things went smoothly, leading to an unforgettable memory.

“I think one of the things that’s most memorable (for me) is our first proper performance because it was really an eyeopening experience, getting to play all the repertoire that we prepared for so long and play it for a really big audience,” he said. “It actually went pretty well, which is why it is also one of the memorable memories that I have.”

“I like to have a chamber music experience

—Written by James Ng, a writer.

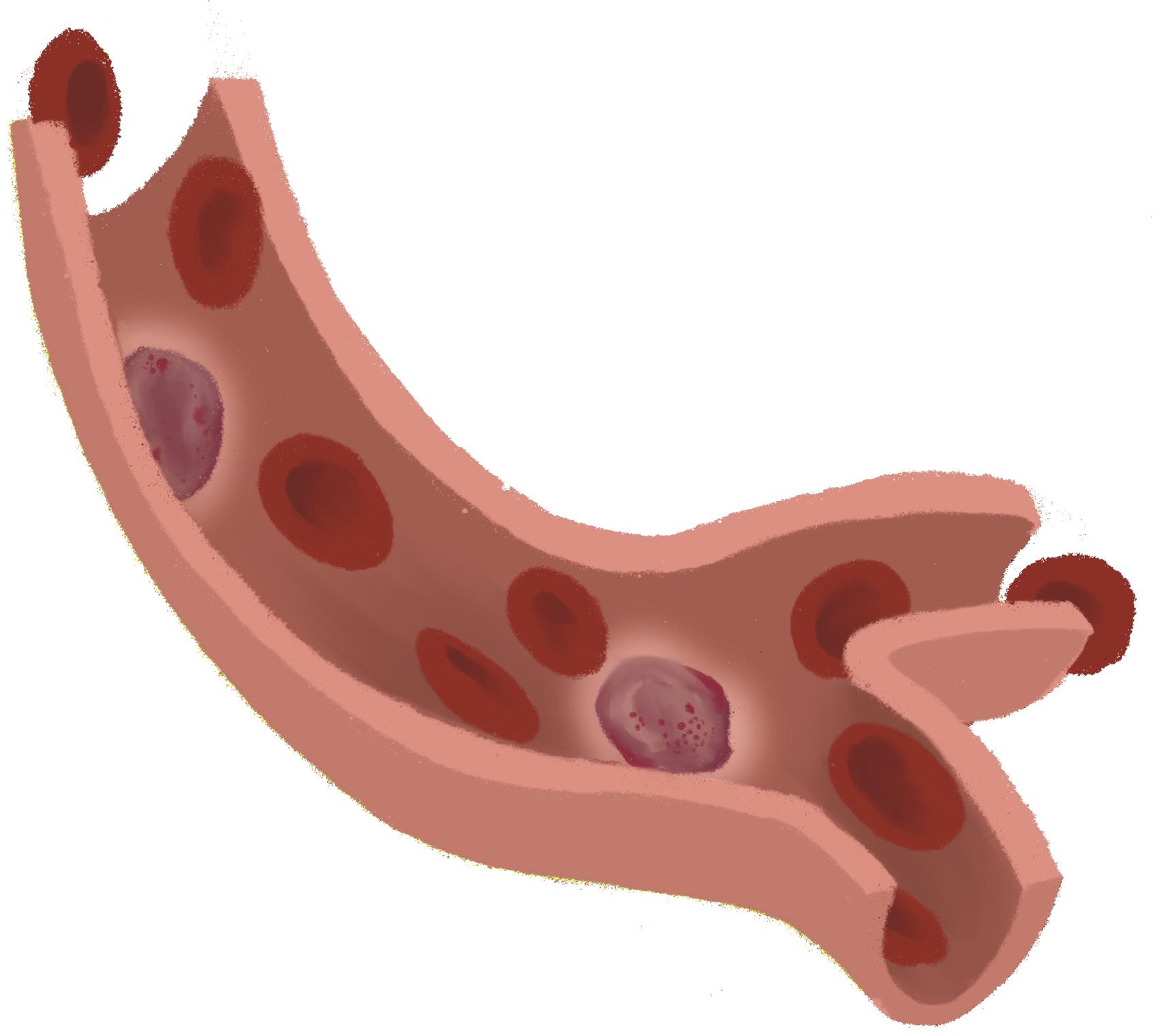

Malaria, one of the deadliest worldwide diseases, is caused by Plasmodium parasites transmitted through the bites of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes. Characterized by high fever, chills and flu-like symptoms, malaria can be fatal if left untreated and is only curable with antimalarial drugs when diagnosed early. The disease is most prevalent in warm, humid regions in Africa and Asia, where it disproportionately affects underprivileged communities due to inadequate housing, increased mosquito breeding and limited access to preventative measures and proper sanitation.

Some of the best ways to combat the spread of malaria are preventative measures like malaria vaccines and mosquito repellents. However, an unexpected approach has surfaced to international recognition: Wolbachia.

Wolbachia is present in almost all insect species, including approximately 30% of Anopheles mosquitoes. These naturally occurring, maternally transmitted bacteria can block the replication of disease-causing pathogens in a phenomenon known as virus blocking. Many Wolbachia spread through natural populations due to cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI), a reproductive manipulation that results in no offspring from matings between a Wolbachia-infected male mosquito and a noninfected female mosquito, meaning Wolbachia-infected male mosquitoes can only produce offspring with Wolbachia-infected female mosquitoes. Because of the success of Wolbachia in counteracting the spread of dengue, scientists are hopeful that it can counteract malaria as well. There are two alternative disease control strategies using the spread of Wolbachia to reduce mosquito-borne diseases: population suppression and population replacement.

researches Wolbachia, suggests it is unlikely to evolve quickly.

“We’ve always worried about whether the host species would evolve to suppress the cytoplasmic incompatibility that’s used to drive the Wolbachia into the population and keep it at high frequency,” he said. “Although predicted based on evolutionary theory, it has never been observed in the lab or nature.”

Despite this, population suppression is costly, typically requiring ongoing releases of Wolbachia-infected male mosquitoes to maintain population reduction.

The population replacement strategy, on the other hand, uses Wolbachia-infected male and female mosquitoes to replace the wild mosquito population with a greater percentage of Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes, therefore curbing the spread of malaria. It introduces specific Wolbachia variants, called “strains,” such as wMel and wAlbB, known to significantly reduce or block the transmission of diseases like dengue and malaria. By releasing enough of these Wolbachiainfected mosquitoes into wild populations, CI promotes the spread of Wolbachia. Once established, these Wolbachia-carrying mosquitoes are less capable of transmitting diseases.

“Malaria elimination, or even a strong reduction in transmission, is not going to happen without multiple intervention strategies.”

—UC Davis Distinguished Professor of Genetics Michael Turelli

The population suppression strategy uses releases of Wolbachia-infected male mosquitoes in an initially uninfected population to reduce or locally eliminate the entire mosquito population. The plan relies on CI to

According to Turelli, the main concern for Wolbachia disease control strategies is rising global temperatures. Many Wolbachia cannot function in extremely hot environments, where diseases like malaria and dengue thrive.

“The big (goal) is to find Wolbachia that will be better adapted to really hot climates and be stably maintained,” he said. “They have to cause CI — we think that’s not going to be a problem — but they also have to be faithfully, maternally transmitted.”

Furthermore, successful applications of Wolbachia are largely found in cases of the dengue virus. Medical entomologist Thomas Walker, who is also an associate professor at the University of Warwick, believes the use of Wolbachia for malaria is much more complex than for dengue. The main reason for this is that there is a larger number of Anopheles mosquito species than Aedes, so creating Wolbachia variants suited to all of them would be difficult.

“I think in 10 to 20 years we will see preliminary release trials (of Wolbachia variants in Anopheles mosquito populations),” he said. “But widespread release in multiple Sub-Saharan African countries would seem unlikely given the challenges ahead.”

But can Wolbachia end malaria? To answer this question, further research is required on the effects of Wolbachia in Anopheles mosquitoes for malaria control strategies to determine if these Wolbachia strains have a significant impact on Plasmodium parasites, and also if these Wolbachia strains can spread through mosquito populations. While Wolbachia is promising, it is unlikely to be the perfect solution.

Nevertheless, Walker believes that relying on a mixture of strategies rather than just one is necessary to genuinely make an impact and eradicate malaria.

“Malaria elimination, or even a strong reduction in transmission, is not going to happen without multiple intervention strategies,” he said. “The use of malaria vaccines in combination with any mosquito control strategy should be the way forward.”

—Written by Athena Gao, a writer.

“Political affiliations and family values, for instance, can lead individuals to dismiss certain perspectives as untruths, allowing emotion to override reason.”

• When was the last time you changed your mind after hearing someone out?

• What moments evoke bring out your cuddle chemical?

“Sharing yourself with someone might feel hard at first, but opening up can lead to deep, lasting friendships.”

Helios explores how human connection — whether through friendship or dialogue across political divides — can foster empathy

For many people, accepting hard truths feels like surrendering control. Instead, they choose to create a sense of artificial control through willful ignorance. Ironically, this decision to ignore often guarantees a loss of control through inaction.

A Gunn student might not see themself as blindly ignorant — yet ignorance still appears in more subtle forms. Political affiliations and family values, for instance, can lead individuals to dismiss certain perspectives as untruths, allowing emotion to override reason. Still, behavioral studies and psychologists affirm our ability to rewire the brain toward informed awareness.

In the realm of political issues, motivated reasoning occurs when people unconsciously interpret information in ways that align with their political beliefs. In face-to-face studies of bipartisan systems, this phenomenon often clashes with the concept of social learning — the idea that individuals can make more accurate judgments by drawing from the opinions of their peers. When a political party symbol is present, or when participants know their partner is from the opposing party, people often make emotionally charged decisions to willfully ignore new information.

To test this, students at the University of Pennsylvania conducted a study to explore whether bipartisan networks could still allow social learning to take place. Participants were shown a NASA graph on sea ice trends and asked to revise their initial predictions based on the consensus of their peers. Surprisingly, the study found that social learning can flourish between individuals on opposite sides of the political spectrum, as long as anonymity is preserved. However, in

separate trials, even minimal political priming led to smaller improvements from participants’ original predictions.

The fact that peer consensus led to more accurate climate predictions demonstrates that both conservatives and liberals are capable of overcoming motivated reasoning. Even when political identity is subtly present, social learning still occurred— just to a lesser extent. This suggests that, even in a deeply polarized society, people have more openness to opposing perspectives than we often assume.

Psychologist Adam Grant calls this mindset the 10 Percent Principle: be 10 percent more skeptical of those you agree with, and 10 percent more charitable to those you don’t. Even if your views don’t change, questioning them sharpens your thinking—and creates space for empathy in a divided world.

—Written

by Donovan Carlson, a writer.

After a difficult test or frustrating day, many people seek something — or someone — that offers comfort and security. Whether found in family, food, music, or books, these sources of comfort play an important role in helping us ease our worries. One of the most common places people turn to is friendship. In female friendships specifically, researchers have found that women who are emotionally close to their female friends tend to feel more relaxed and happy. This is due to the release of two key hormones: oxytocin and progesterone. Oxytocin, commonly known as the “love hormone” or “cuddle chemical,” is released during positive social interactions like hugs or heart-to-heart conversations. While it’s famously known for stimulating contractions during childbirth, oxytocin also serves a powerful social function. It helps promote bonding, encourages trust and improves mental stability. As oxytocin is released, women often seek more interaction and engage in more vulnerable, meaningful conversations because of the heightened sense of trust.

SPARK BRAIN’S ‘CUDDLE CHEMICAL’

Progesterone, another hormone released during social connection, plays a calming role. It helps reduce anxiety and stress, which explains why women often seek comfort in their female friendships. A University of Michigan study found that higher levels of progesterone not only boost well-being but also increase a person’s likelihood to help others. In this way, the personal benefits of female friendship ripple outward—calmer, more grounded individuals foster more positive and memorable interactions, creating stronger, healthier communities.

The effects of these two hormones highlight just how essential friendship is to our daily lives. As students, we’re constantly facing academic pressure from parents, peers, and ourselves. And even as we grow older, stress continues — whether it’s balancing work, family, or the challenges of adult life. Chronic stress can lead to both physical symptoms, like headaches, and emotional tolls, such as depression, sadness, or anger.

Even today, in the 21st century, women are often expected to juggle raising children, managing households, and excelling in the workplace — all while rarely making time for themselves. That’s why having someone to talk to, to bond with, to grow closer to is more important than ever. Sharing yourself with someone might feel hard at first, but opening up can lead to deep, lasting friendships. In the end, those friendships don’t just help us feel seen and supported—they shape a more relaxed, more trusting world.

—Written by Evelyn Luong, a writer.

When he was only six months old, math teacher Khoa Dao escaped Vietnam with his family after the Fall of Saigon. Though he grew up in California, his earliest story was one of exile. For him, April 30—known to Vietnamese everywhere as Black April—is a day of remembrance, mourning, and resilience.

For years, Dao wrestled with questions of identity. As a stu dent at UC Berkeley, where Vietnamese made up only a fraction of the population, he often wondered where he truly belonged.

“Okay, well if I’m not Vietnamese (and) I’m not American, then what am I?” he said.

It wasn’t until he joined the Vietnamese Student Association that he began to feel at home. Surrounded by peers who shared his struggles, Dao came to see his identity not as a divide but as a bridge between cultures.

For Dao, Black April reminds him of the importance of understanding your identity and working to better your community. The aftermath of the Fall of Saigon has led to many Vietnamese people living abroad. But rather than seeing this as an obstacle, Dao believes it to be a new beginning. He explains that Black April also commemorates the struggles that Vietnam ese refugees took for a brighter future.

“I’m just so proud of my Vietnamese brothers and sisters in all these different professions, all these different countries — we’re killing it,” he said. “It seems like we’re really rising in the community. So, I look at it as an op portunity for the new generation to be able to grow and thrive.”

As for the younger generation, Black April serves as a powerful remind er of their roots. Growing up, senior Anh Le often felt unsure of where she fit. Living in a town with little Vietnamese representation for almost seven years, Anh felt disconnected and was even bullied for her cultural identity.

But after moving to San Jose, Anh began to feel pride in her culture. San Jose’s Viet namese community makes up 10% of the population, being the home to the largest Vietnamese population outside of Vietnam. Surrounded by others who shared her back ground, Anh found a sense of belonging and understanding of who she was: a Vietnam ese-American.

For Anh, Black April reminds her of the dedication, effort, and resilience Vietnamese people have endured in the face of hardship. Being able to understand and see, first hand, the strength that her community brought from Vietnam opens a gateway for the younger generation to embrace their identity.

“I think a lot of the time, we disconnect from the stories of our heritage and the people that it’s connected to, but I think it’s important to connect these stories with the people that are close to us.”

—Junior Arden Lee

“It’s just important to reconcile your relationship with your Vietnam ese-American identity,” she said. “I think that’s something really special.”

To junior Arden Lee, Black April holds a significance greater than his own story. Surrounded by Vietnamese culture all his life, Lee carries strong traditional values. Although his identity spans across many cultures — Viet namese, Chinese and Burmese — growing up closest to his maternal family, Arden has found a strong bond with his Vietnamese originality. Through these relatives, he found a sense of belonging and pride that needed to be shared.

“It’s also important to understand that everything is linked,” Lee said. “No matter where you’re from, there is a relationship and identifying these connections, embracing them and using them to empower each other is the best gift that we could give.”

“I think a lot of the time, we disconnect from the stories of our heritage and the people that it’s connected to, but I think it’s important to connect these stories with the people that are close to us.” he said. “Black April allows us to do this by highlighting their stories.”

—Written by Ella Nguyen, a layout designer.

Every day, sensationalized headlines announce to an anxious world the latest in politics and science: cuts to the National Institute of Health, slashes to university programs, grant cancellations and other jarring news. This recent flurry of fear-mongering seems like an abrupt change in fields that used to be celebrated — after all, it seems like the rigidity of science, based upon reason, logic and universal truth, should preclude its controversiality.

Although these ongoing debates over science may seem new, the contentious political nature of science is hardly a novel phenomenon. Throughout history, politics have permeated science, shaping public perception and influencing the direction of inquiry. The powerful often block scientific research that threatens to jeopardize their influence — some of the best early examples being religious elites. Weaponization of science has allowed those in power to justify colonialism, slavery, eugenics and other actions of highly dubious morality through a twisted form of science. With the rise of the internet, the spread of disinformation has only increased distrust in science, leading to its ultimate devaluation. The widely varying effects of politics on science can be generally split into three categories: suppression, manipulation and devaluation.

One of the paradigmatic cases in suppression is found in the 16th century debate over heliocentrism. Nicolaus Copernicus, a Polish astronomer, was the first to propose his hypothesis that our solar system revolves around the theory directly opposed the Church’s geocentrism — the belief that everything revolved around the Earth. Galileo Galilei confirmed this theory through his invention of a new telescope. The Church accused Galileo of heresy, condemning Copernicus’ work and putting Galileo on trial by the Royal Inquisition. Galileo was forced to give up his writing, denounce heliocentrism and remain in house arrest until his death. The Church’s authority was weakened by scientific questioning, and by suppressing dissenting voices, it maintained its control.

or “good in birth,” and is a pseudoscience dedicated to the theory that it is possible to “perfect” people or groups of people based upon the principles of genetics. Through the first half of the century, scientific fields dedicated to the justification of social prejudices exploded. Craniology, one of the most notable, consisted of measuring properties of the skull in order to determine differences between various racial groups. False data on the size of African-American skulls helped white supremacists claim to “prove” the racist idea that non-Europeans were innately inferior. In Nazi Germany, eugenics was used to justify horrific experiments throughout the Holocaust: scientists manipulated research to justify the mass murder and sterilization of Jews and other groups seen as inferior. Forced sterilization of those deemed genetically second-class wasn’t unique to Nazi Germany either; it was often used against mental patients in America, disproportionately on African-American women. Science has never been free from the biases and beliefs of those in power: it is inherently political.

Through the late 20th century, the silencing of climate research allowed large industrialists to maintain their empires. Scientists had been researching the effects of industry on climate since the 1950s. According to Scientific American, ExxonMobile, an oil and gas company, had information from scientists as early as 1977 warning executives about the dangers of climate change. Multiple impassioned warnings from senior Exxon scientist James Black given to executives were ignored — if the company acknowledged the veracity of these reports, they could harm the company’s interests. Exxon even helped found the misleadingly named Global Climate Coalition, a group dedicated to undermining the scientific basis of climate change. Confusion and disinformation spread by companies like Exxon continues to suppress the proper execution of scientific research, shoving the needs of the many aside in favor of maximizing material gain for the few.

However, as scientific ways of thinking increased in popularity, especially after the Scientific Revolution, the powerful also began to manipulate science for their own agendas. If suppression is denial of fact, misrepresentation of fact has been similarly exploited. The eugenics movement of the 20th century provides a prominent example of this manipulation tactic. Eugenics’s name comes from the Greek term “eugenes,”

As powerful institutions and individuals are threatened by scientific research — as with Exxon — they try not only to suppress and manipulate science but to devalue it as a whole. If the public no longer believes in scientific thinking, there is no voice of reason or dissent against false narratives. A clear illustration of this effect in the 21st century has been the growing distrust in vaccines. Starting with papers in the 1990s that falsely using cherrypicked data to claim that vaccines caused autism, the general public started to doubt not only vaccines but the institutions of science as a whole. The age of social media and the COVID-19 pandemic only accelerated this trend, as the internet provides a way to quickly and easily disseminate disinformation. The end result? Some of the biggest measles outbreaks since the eradication of measles via vaccine. In fact, the current United States Secretary of Health and Human Services, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., has himself propagated false claims that vaccines cause autism. He has also stood against the addition of fluoride to drinking water — despite the CDC declaring it one of the biggest advancements to public health in the 20th century. In addition, Secretary Kennedy has criticized the addition of riboflavin to cereals. Riboflavin is another name for vitamin B2, a substance essential for our health that is not harmful as an additive. Politicians have targeted vaccine mandates and other public health issues, dragging them into the argument of government overreach and exploiting the skepticism and distrust in science that they helped create and perpetuate in order to maintain power.

Though the world of science today is fraught with political conflict, the entanglement between politics and science is far from a new development. Whether it be the 16th century suppression of groundbreaking ideas by the Church, justification of eugenics or degradation of trust in scientific institutions, politics and power dynamics have been closely tied to the creation and advancement of science. Understanding this history reminds us that this is not a passing trend. The dire challenges we face today, while frightening, are new iterations of the long-standing struggle against efforts to obscure, manipulate and undermine scientific discoveries to promote specific agendas.

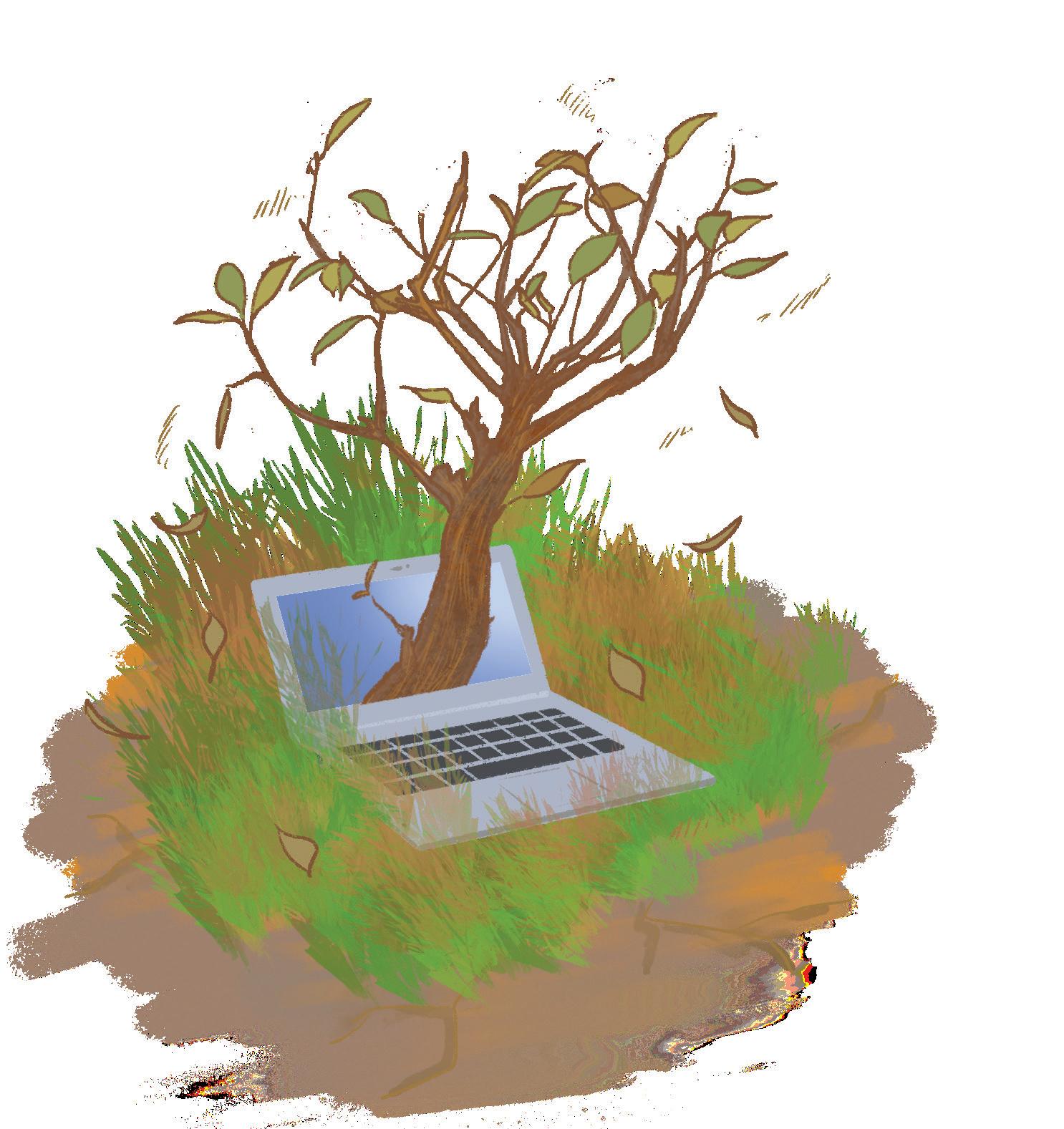

Data

From an obscure research project to a household name, artificial generative models such as ChatGPT, Gemini and Perplexity have furthered global access to artificial intelligence. However, surrounding the zeal of AI’s popularity, there is a darker side: an environmental consequence that threatens our carbon emission goals.

AI has increasingly become a powerful and productive tool. Both students and workers alike use it for tasks including information retrieval, grammar checking and email drafting. According to a 24-hour Instagram poll done in March, about half of the 61 pollers (majority of whom go to Gunn) reported that they use AI on a daily basis and 70% thought that AI was useful in their lives. With AI developing more and more use cases by the day, it has undoubtedly become an integral part of many people’s lives.

Unfortunately, at a time when humanity is trying to reduce its carbon footprint to mitigate climate change, AI is highly energy and resource-intensive. Recent studies suggest that AI makes up one to two percent of global energy consumption and this figure is set to increase to four percent by 2026. To better understand the consequences of AI, we must first look at where these AI companies emit the most: data centers. To put it simply, data centers are massive buildings that house computer graphics chips to run models such as GPT and Gemini. A data center’s carbon footprint can be divided into three subcategories: construction, chip construction and inference. Firstly, most data centers are primarily composed of concrete, which can contribute to up to 80% of total embodied carbon emissions. Concrete is an incredibly carbon intensive product, emitting around 112 pounds per square foot. Considering the average size of a data center, this could mean that several thousand tons of carbon are emitted from just con struction alone.

data centers handling up to tens of thousands of GPUs, chip manufacturing emits large amounts of carbon. However, both of these figures can’t come close to the actual emission from the usage of these models. The average ChatGPT query consumes upwards of 0.0029 kilowatt hours, or up to ten times more energy compared to a Google search. In the year 2022 alone, the AI industry consumed 1.65 billion gigajoules of energy, equivalent to the energy consumption of a medium sized country. Instead of relying on solar, wind and hydropower, countries may need to burn fossil fuels to meet this demand for electricity, potentially slowing down the movement to a greener, carbon-free future. According to Google’s 2024 Sustainability Report, data centers in many European countries already run on upwards of 90% of clean energy. However, data centers in developing countries like Asia and the Middle East still use coal or natural gas to generate electricity.

In the year 2022 alone, the AI industry consumed 1.65 billion gigajoules of energy, equivalent to the energy consumption of a medium sized country.

Source: International Energy Agency

Next, the actual construction of the graphics chips (GPUs) must be considered. The average Nvidia GPU can emit upwards of several hundred pounds of carbon through its construction and delivery to facilities. With

While AI may slow down our fight against climate change, there have been numerous initiatives to decarbonize data centers. When it comes to the private sector, despite Google having to remove its carbon neutrality goal after it introduced Google Gemini due to being unable to purchase enough carbon credits to keep up with the emissions from its data centers, it has made clear its intention to reach carbon neutrality and has set a new goal of 2030. Another example is Microsoft, which has begun to use wood to construct data centers in an effort to lower its embodied carbon emissions. A standard metric in the industry is the PUE ratio, which measures the total energy a data center uses over the amount used for the actual computations. In 2016, the PUE ratio was around 1.5, meaning that 33% of the data centers’ energy consumption was used for anything besides computations, such as cooling. However, companies have been able to lower their PUE ratios, with Google claiming it has lowered its to around 1.01. Regardless of how energy efficient these data centers are, we need to ensure the source of energy is also clean to achieve carbon neutrality in this sector. Firstly, we must push governments to invest in constructing clean energy sources, such as hydroelectric dams, solar farms and wind turbine farms. Another idea is to introduce a carbon tax, where companies have to pay the government based on the amount of carbon they emit. Through this route, we can provide revenue for the government to build clean energy infrastructure while simultaneously motivating companies to continuously build cleaner data centers.

As the world begins to adopt AI, it is imperative that we remain aware of the environmental costs. Through establishing clean energy infrastructure or incentivizing companies to increase data center efficiency, it’s possible for us to decrease the drawbacks.

—Written by Owen Cheng, a writer.