AMERICAN BUILDERS QUARTERLY

At Brookfield Properties, Michael Daschle is focused on one thing: bringing improvements to his company, its communities, and the world P40

Jill Pearsall takes a fluid approach to planning at Texas Children’s Hospital P70

Maria Beard prioritizes oftenoverlooked factors to help children on the austim spectrum thrive at Action Behavior Centers P96

High school students are given a tour of Wellesley College.

High school students are given a tour of Wellesley College.

Tim Singleton and Wellesley College lead by example when it comes to bringing muchneeded, equitable change and building a diverse pipeline for the future

BY BILLY YOSTPORTRAITS BY NICOLE LOEB

Given his early experience in the field, it’s a miracle that Tim Singleton stayed around. But the construction space is better because he did.

He was working as a tradesman at the beginning of his career when one of his coworkers told him the only reason that he had a job was because he was Black. “And I told him, the only reason that he was on this project was because his uncle was the superintendent,” Singleton remembers. “That’s the issue I’ve always looked to address. You have to know somebody to get these jobs, and it’s about improving access to make the building space a more equitable one.”

As associate director of construction at Wellesley College, Singleton lives his mission on behalf of an organization that is determined to educate women to make a difference in the world. And from his position, Singleton creates those opportunities within his own organization to break down traditional barriers in the construction space.

In his own words, Singleton shares with American Builders Quarterly about building a more equitable pipeline for the future and what it means to actually practice what you preach when talking about equity in construction.

Since 2018, our capital projects team has been working with diverse groups of other owners, contractors, and designers to move the needle on building higher-performing teams through continuous improvement. We know through research that diverse teams are a part of this, and our efforts have led us to focus less on percentages and quotas.

Our discussions have been about helping to lead in the way we create real, long-term minority- and women-owned business enterprise (MWBE) improvements in the design and construction industries. We do it because not only is it the right thing to do but it leads to better outcomes for everyone involved.

We know that it’s about building the pipeline for the future. We want to lead by example. We want others to follow us. Do what we do.

In 2018, we began construction of our new $200 million-plus science complex. It included major

Tim Singleton

Associate Director of Construction

Tim Singleton

Associate Director of Construction

new and deferred maintenance work, a teaching and research greenhouse, another greenhouse to house our botanical collections, a new observatory, and landscaping.

In 2019, the Wellesley College senior leadership recommended that our project team to follow MWBE quotas per Massachusetts state guidelines for public construction projects. These efforts and policies have been in place for many years in many places throughout the country.

We were very successful in meeting the state’s guidelines on our private college campus. However, our community of owners, contractors, and designers recognized and agreed that efforts must be redirected to allow for much better long-term outcomes. Together as a community, we are more powerful and can build more momentum than the individual efforts on our campuses.

We are coming together to raise the bar on expectations for each other and our supply chain partners by moving beyond quotas to substantive opportunity creation for underrepresented individuals and firms. By educating, learning from, and challenging each

other and our communities, we’re breaking down the barriers to systemic change. We created goals, both short- and long-term:

1. Build culture of diversity inside our organizations

2. Support underrepresented firms to engage in work with us

3. Alter and share procurement practices to partner with like-minded vendors

1. Build the pipeline

2. Develop best practices and share them with others

3. Measure, track, and report outcomes

On the campus of Wellesley College, we have altered our procurement practices to identify and seek planners, designers, and builders who actively work for real, long-term diversity changes within their industries. We will no longer use only quotas and percentage counts to drive change.

Women from various firms that work with Wellesley stand together to form a single high-performing project team. Courtesy of Tim SingletonWe say, “If you want to work on our campus as a designer or contractor on our larger projects, we expect you to do much more than just count percentages. You must be doing things that we know really create real, long-term diversity, equity, and inclusion improvements within the architectural and construction industries.”

Here are nine examples of what we see now from those working on our campus:

Turner Construction Company (TCCO) led by example on our science building project, and we’re talking about almost all the trades, superintendents, project managers, and field supervisors, and even TCCO’s vice president. It frequently toured diverse youth groups on-site so that these kids could “see people that look like them, doing things that are not typically done by people that look like them.” TCCO leverages its relationships with local community groups to reach diverse populations that may not be reached through traditional outreach for workforce development and youth STEM engagement.

“You have to know somebody to get these jobs, and it’s about improving access to make the building space a more equitable one.”

As a third-generation, family-owned and operated WBE, Elaine Construction’s dedication to a diverse workforce is a challenge that it embraces. Acknowledging that challenges extend beyond visibility and access to include payment terms, bonding, capacity, favorable loans for business expansion, and more, begins to unpack the breadth and depth of the challenge. As Elaine Construction expands its understanding, form alliances and partnerships within the industry, and with clients, we witness change. From (former) Mayor Walsh’s Pay Equity Compact to its affiliation with the Commonwealth Institute, and participation in MA Workforce Training Fund programs—both in the office or field—Elaine Construction values the individual so that the team can succeed.

In 2010, Suffolk launched an accelerator program, Build With Us @ Suffolk, to offer small business enterprises and minority-, women-, and veteran-owned

“Together as a community, we are more powerful and can build more momentum than the individual efforts on our campuses.”Courtesy of Tim Singleton

business enterprises (MWVBE) the experience to work with Suffolk or other firms. The eight-course interactive program is structured with a focus on construction management procedures and processes. Upon graduation, each trade partner is paired with a Suffolk executive who serves as a mentor and provides continued support for lasting development and opportunities.

Suffolk included LJV Development as part of the team to whom the college awarded a $10 million project. Suffolk formed a mentoring partnership with LJV following its successful completion of the Build With Us at Suffolk program and its successful completion of a smaller project on campus. As a an MWVBE, LJV has already become a valuable team member.

Dellbrook | JKS’ Community Partner Accelerator Series consists of two half-day sessions hosted on a quarterly basis with the intention to assist its MWBE trade partners through a series of trainings that will make them better prepared to work with Dellbrook | JKS and other CMs. The curriculum was designed specifically to assist

Team members from various firms in Wellesley’s pipeline stand together to discuss a project.

Team members from various firms in Wellesley’s pipeline stand together to discuss a project.

with barriers such as insurance, bidding, estimating, safety, accounting, and more.

Upon completion of the Partner Accelerator program, each subcontractor is equipped with Procore and a Certificate of Completion that signifies they have completed the course and are better prepared for success on all of their projects. Dellbrook | JKS has also presented trade partners with iPads at the end of the program to give them the physical tools they need in addition to the education.

Walsh Brothers is committed to treating all employees with respect and dignity, and the diversity of its employees enhances creativity and brings unique viewpoints

to the company. The Women of Walsh (WOW) strives to unite women company-wide and improve the workplace by creating opportunities and supporting their personal and professional life.

WOW’s events and programming are geared toward increasing awareness of issues that specifically affect women in the industry. It works to support and facilitate learning through career development and leadership skills events. Additionally, WOW holds social events to help connect women with other women, share ideas, and encourage informal mentorships and networking opportunities.

Shawmut has actively partnered with the Compliance Mentor Group on Harvard projects to run its signature workforce program. This is a three-phase, twelvemonth mentorship program for Boston-area career and STEM school students. Through group learning, job-shadowing, and mentoring experiences, students become acclimated to a project site and work with the project team members whose careers align with the students’ academic studies and career goals.

Lee Kennedy (LK) is a full supporter of Operation Exit, which trains young people returning from incarceration by giving them a second chance. Many of these are women and people of color. LK is a supporter of Building Pathways, a six-week pre-apprenticeship program that provides low-income women and minorities an introduction into the highly competitive apprentice opportunities, and Youth Build Boston, which provides underserved young people with the support and credentials needed to successfully enter the building trades. Christine Walsh, its director of government and community relations is a cochair for the Building Pathways Employers Advisory Committee.

Many Isgenuity employees are members of local and national professional organizations that focus on elevating the next generation of women and minorities in the design profession. They are active supporters and participants in the Professional Women in Construction’s Boston chapter, the National Organiza-

High school students tour Wellesley’s facilities.

High school students tour Wellesley’s facilities.

tion of Minority Architects and its Boston chapter, and the Young Designers Professional Development Institute, among others.

Isgenuity continuously improves its approach to addressing diversity, equity, and inclusion in the work and organization through these memberships. This may be why it is so successful in having a diverse team. The design firm has connected with many others in the industry who support the mission to advance women in their design and construction careers. We (at Wellesley) have been active participants on outreach and scholarship giving boards, and we have presented in public forums on career advancement for women.

Finegold Alexander Architects (FAA) has become a women-owned business by promoting from within and leading by example. FAA works to promote a culture in which its staff are empowered to support their families, pursue individual and community interests, and thrive economically. The firm has a formal mentoring program, schedule flexibility (implemented pre-COVID), offers paid time off for volunteering, and offered paid parental leave prior to the 2021 implementation of the Massachusetts Paid Family and Medical Leave program. The firm additionally is a sponsor of NOMA (National Organization of Minority Architects) Project Pipeline, which provides summer experiences and introduction to the design professions for students of color, as well as employing Boston high school students for summer internships through the Boston Private Industry Council program.

DesignLAB architects is another women-owned business created from promoting from within. It is focused on improving communities through mentoring and supporting emerging designers. As such, designLAB has committed to an ongoing internship program dedicated to supporting Black, Indigenous, and people of color as they enter the profession.

The three-month program employs aspiring architects with the goal of giving them a broad range of experience and exposure to the profession. The program is fully compensated and open to any students who are currently enrolled in a professional degree program in architecture and identify as Black, Indigenous, or a person of color.

Turner Construction Company is proud to have completed this state-of-the-art science facility for Wellesley College. The new academic building contains offices, classrooms, and lab programs, and has transformed the existing facilities while simultaneously preserving the historic integrity of the buildings and campus. The Science Center encompasses four existing structures, including a complex of greenhouses; Sage Hall; the L Wing addition that includes laboratories, a vivarium, and an atrium; and the E-Wing classrooms and offices. With an emphasis on sustainability and the impressive use of mass timber, this building received LEED Platinum certification.

Walsh Brothers is committed to addressing diversity and inclusion issues within the industry. Our Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (WBDEI) committee is made up of employees selected from all departments to ensure representation and input from a diverse range of voices. The WBDEI committee established both immediate and long-term goals that continue to help direct our focus and initiate new behaviors on the projects we manage as well as the culture of our company. The committee is split up into multiple subgroups: Education and Training; Affiliations and Partnerships; Marketing and Communications; Site Workforce Diversity; Subcontractor Diversity, Policy, and Support; and Mentoring. These subgroups meet separately to discuss individual objectives and develop ways to achieve inclusiveness in the workplace; the entire WBDEI committee meets biweekly to report, measure, and reassess our efforts.

We are proud of our continued relationship with Tim Singleton & Wellesley College

Quincy | Falmouth | dellbrookjks.com

Quincy | Falmouth | dellbrookjks.com

We are pushing to have the conversation with anyone that will listen. Focus less on just counting percentages. Do more to build the pipeline. Yes, it’s the right thing to do. But we also know through numerous studies that more diverse teams lead to continuous improvement and higher-performing teams.

Higher-performing teams lead to better outcomes for owners. And more successful projects lead to more work for designers and contractors.

Suffolk is a national enterprise that builds, invests, and innovates. We are an end-to-end business that provides value throughout the entire project life cycle by leveraging our core construction management services with vertical service lines that include real estate capital investment, design, self-perform construction services, technology start-up investment, and innovation research/development. At Suffolk, we service clients in every major industry sector, including healthcare, mission critical, science and technology, education, gaming, transportation/aviation, and commercial. Learn more at suffolk.com.

Su olk is thrilled to work with the Wellesley College team again this summer on renovations to the school's Pool House. Su olk.com/Higher-Education

Wellesley College - Beebe Hall and Munger Hall RenovationsWe are proud to be partnering with Wellesley College on their upcoming renovation projects.

It’s on Mark Murbach to make traditional high schools function in a decidedly nontraditional way. What’s more, he has to do it within the financial structure of a charter school system: based not on what property taxes can be raised, but according to a per-studentenrolled budget that can change from year to year.

Murbach is the director of facilities and property management for Colorado Early Colleges (CEC), founded in Colorado Springs. The institution is made up of 11 schools: 6 high schools, 3 middle schools, and 3 “college direct” campuses. Meanwhile, the course curricula support the name “early colleges,” as a good portion of the students earn college credit while simultaneously earning a high school degree. In fact, some students earn a full college bachelor’s degree by the time they graduate CEC.

It should be obvious, then, that CEC is not your typical American high school: students spend their days building robots and diving into advanced calculus, whether they’re being taught by staff or at home. On some campuses, up to 20 percent of the students are homeschooled; CEC provides them with laboratories and other functions that is difficult to replicate in a home environment.

In fact, part of what draws students to this tuitionfree charter education is such things as robotics and aviation laboratories, where they get hands-on mechanical engineering instruction and sufficient experience with drones to earn professional drone pilot certifications.

This is where Murbach’s task gets interesting. Because those facilities were formerly traditional high schools or big box stores, he is able to convert spaces such as gyms for other purposes, including drone piloting instruction. Most CEC schools do not have traditional physical education, thereby freeing up that space.

One such location, in Fort Collins, is a repurposed 90,000-square-foot warehouse. “This is where we have our ‘maker space,’ a massive workshop for woodworking and building classes,” Murbach says. It was retrofitted with the power and safety requirements of manufacturing space and includes 3-D printing equipment and tools for laser engraving, intertwined with CAD capabilities that tie it all in with digital learning.

The Staff Break Room at the CEC Innovation Campus.

The entry hall at the CEC Innovation Campus.

The Staff Break Room at the CEC Innovation Campus.

The entry hall at the CEC Innovation Campus.

So while a large portion of CEC students are actually earning college degrees, the schools don’t neglect students who elect to join apprenticeships and trades.

“This education addresses shortages in the market,” says Murbach, whose own background includes a bachelor’s degree in facilities planning and management and a facility management professional certification.

Another feature of the CEC high schools are green screen rooms, used for video production instruction, which Murbach says exposes students to the video industry. It’s one of many structured pathways that fast-tracks kids into a community college or university major. “The idea is we allow kids the opportunity to try and explore something that is new to them,” he says.

The CEC schools also serve as testing centers for technical courses, such as AutoCAD, Microsoft Office, and Adobe. These involve monitors and desktop computers, appropriately spaced and with the power cords required to support them.

Through this conversation, it’s apparent that Murbach is basically a microeconomist. Unlike a facilities manager in a traditional public school, he has to make the schools operate within that enrollment budget—and generate income where prudent and possible. Which means if a space is underutilized, it can be rented out.

“We have many tenants,” he explains. “Half of what I do is onboarding and managing them.” Those renters include other charter schools, mostly prekindergarten and K-5 schools, some for-profit ventures (including a trampoline park), and a technical university. “Big buildings with high ceilings are right for some of these organizations.”

But to be clear, CEC more than makes do with what they have. In the case of cafeterias, this is a thoroughly progressive venture that triumphs over the typical bad high school cuisine.

“All schools are supported by CEC scratch kitchens,” Murbach explains. “Our food is locally sourced, and

some is grown on-site. Very little is prepackaged food.” With about 10,000 square feet of dedicated kitchen space, the system also serves as a farm-to-school lesson for students: some work in the kitchen, while others get involved in the grow operation. Students plant the seeds, nurture the plants in raised beds, then harvest the produce.

Murbach has been in his position since mid-2020 and credits his predecessor and chief executive administrator for growing CEC’s footprint with added facilities. But his mission is different: to manage those facilities—including capital improvements and costly maintenance projects—with a zero-based budget. This isn’t easy, he explains. “I have to write grant proposals for state capital funding,” he says. “Fortunately, we have reserves, plus vendors invested in the success of CEC. We work together to find cost-effective solutions.”

Murbach is a problem solver that the CEC students, stereotype-defying kids they are, can observe and learn from.

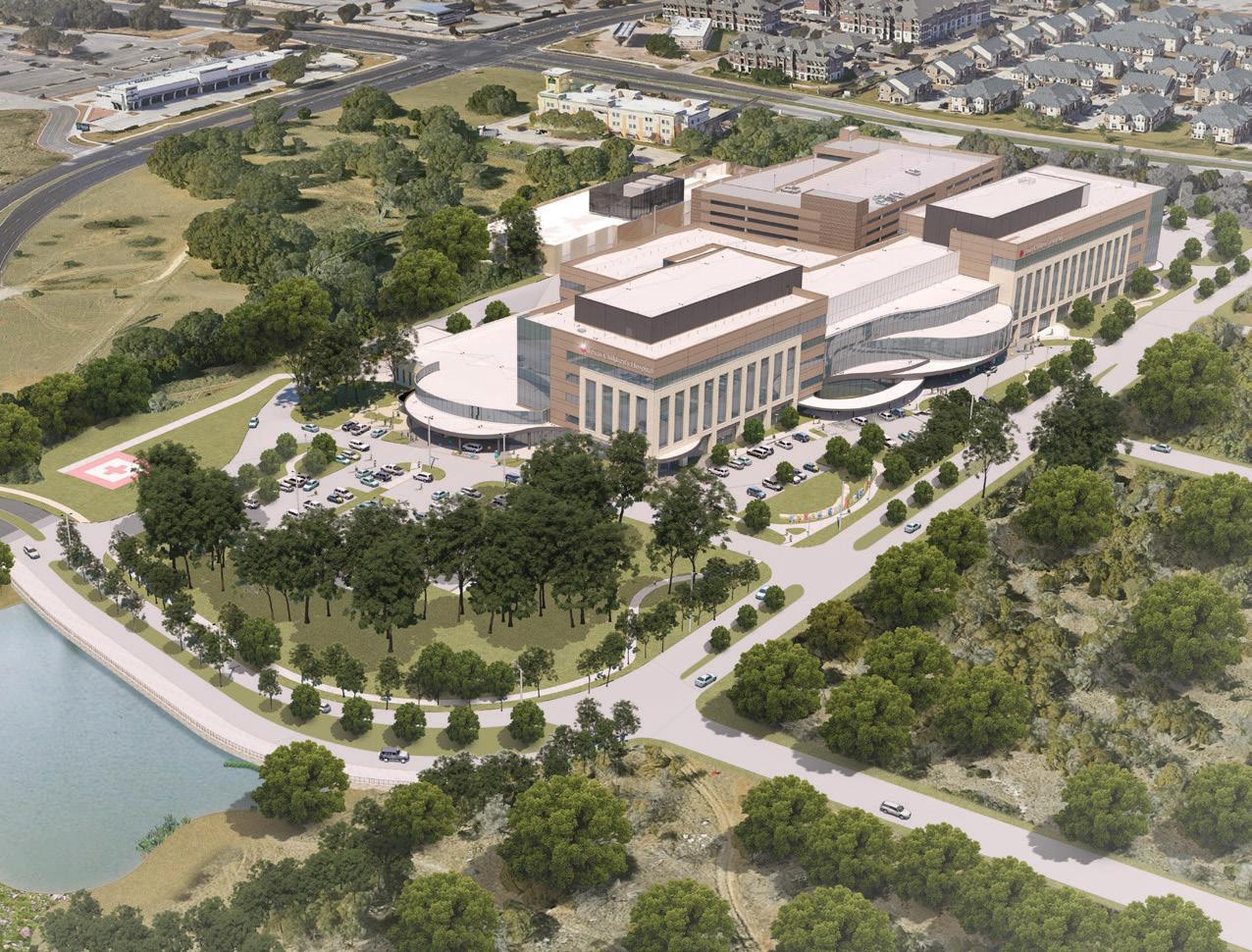

The Susan and Henry Samueli Interdisciplinary Science and Engineering building.

The Susan and Henry Samueli Interdisciplinary Science and Engineering building.

Having equipped UC Irvine with more LEED-certified Platinum and Gold buildings than any college campus in the US, Brian Pratt is proving that the time for sustainable innovation is now

BY MARCOS CHISHOLM

BY MARCOS CHISHOLM

Many colleges have a hero who injects life into its campus. For some universities, it’s a star football player; at others, it’s a student body president who’s as popular on the quad as the Pope is in the Vatican.

Every now and then, there’s someone working behind the scenes in the administration that deserves similar praise. Enter Brian Pratt, campus architect and associate vice chancellor at the University of California, Irvine (UCI); he leads the university’s Design and Construction Services (DCS) group, which handles more than $2 billion worth of projects on campus.

The recognition is there—project partners of Pratt’s are quick to attest to his skills. “We’ve had the opportunity to work closely with Brian and his team to retrofit numerous buildings on campus,” says James Awford, project executive and principal of BNBuilders. “His leadership style and collaborative approach to delivering projects with practical solutions has proven to be a recipe for success.”

Since his arrival to UCI in 2014, Pratt has laid down the foundation for DCS to thrive as a behind-the-scenes change agent on campus. Before DCS began to play a large role in the growth of UC Irvine, Pratt expanded its services by handpicking talented teams of inspectors,

“[Being a servant leader] is really just exercising good judgment and trying to offer good advice to campus leadership and other stakeholders.”

project managers, and contract specialists, all with a common goal.

“I think to survive and to do well in this environment, you need to be committed to the [UC Irvine] mission and be relentless in ensuring it’s met on each project,” Pratt says. “They don’t just reinforce it. They help shape it.”

Once Pratt noticed the early returns from his staff, he hired plan reviewers, financial analysts, and quality assurance coordinators that bolstered the credibility of DCS. Soon, DCS had transformed into a dynamic department with 21 employees with a need to approximately double.

Still, Pratt knew that working smarter—not harder— would be key to leaving a lasting impact on the 37,000 students and more than 1,500 faculty members at UCI. Like all University of California schools, UC Irvine has committed to becoming carbon-neutral by 2025. The school has been investing in the sustainability of its open facilities, and Pratt is helping to ensure that this becomes a reality.

For example, Pratt and his team are implementing a Central Utility Plant as part of UCI’s new hospital. The project makes it easier for the UC Irvine Medical Center Irvine to manage its utilities. The UC Irvine Medical Center Irvine will rely on it to enhance patient care in the region, including cancer treatment, surgeries, and ICU support. The icing on the cake? The plant is 100 percent electric, reducing energy consumption and lowering maintenance costs across the medical campus.

“The only fossil fuels that would be burned would be diesel fuel for an emergency generator in the event of a major catastrophe that brought down our electrical feeds,” Pratt says.

Pratt thrives as a servant leader who listens to his team and acts as a practical diplomat who’s three steps ahead. He anticipates what everyone needs, which allows him to find common ground and create win-win opportunities.

“It’s always a balance,” Pratt says. “There are a lot of stakeholders on a campus, ranging from campus leadership, right down to students, faculty,

BNBuilders recently completed this $20 million designbuild renovation project for UC Irvine. The project addressed a number of urgent fire and life-safety issues in academic areas of the Irvine campus, including the installation of fire sprinkler systems throughout two laboratory buildings—Rowland Hall and Reines Hall— and in the breezeway of a third engineering laboratory facility. Obsolete fire alarm systems were replaced in 13 academic buildings and one campus support building, thereby improving the safety of over 500,000 square feet in UC Irvine’s academic core.

NEW FOR IRVINE

Hathaway Dinwiddie has had a longstanding presence on the University of California, Irvine’s campus, building state-of-the-art structures for students, faculty, and staff Since 2005, Hathaway Dinwiddie has successfully delivered projects such as the Sue & Bill Gross Stem Cell Research Center, Gavin Herbert Eye Institute, Paul Merage School of Business, and Anteater Learning Pavilion.

The latest endeavor serves the Susan and Henry Samueli College of Health Sciences, Susan Samueli Integrative Health Institute, and Sue & Bill Gross Nursing and Health Sciences Hall. Going up concurrently with this project is the Interdisciplinary Science and Engineering Building and the Health Science Parking Structure.

and staff. So it’s really just exercising good judgment and trying to offer good advice to campus leadership and other stakeholders.”

The results are impressive. UC Irvine’s 21 LEED Platinum projects lead the nation for college campuses. Pratt and his team got approval to break ground on a $1.3 billion hospital complex that includes 144 acute care beds, an emergency room, and the Chao Family Comprehensive Cancer Center. They’re also building the Joe C. Wen and Family Center for Advanced Care, including multispecialty clinics, urgent care, an autism center, and pediatrics.

Overall, that’s more than 1.5 million square feet of combined space of a total current construction portfolio of more than 4 million square feet. Pratt points out the important role that his team plays in accomplishing all this work. “I can’t emphasize enough how professional, skilled, and committed they are,” he says.

“That’s a credit to the team here, but also to our industry partners and our design and build teams because they’re also very focused on the right

outcome for a project. Hopefully we treat them in a manner that they’ll want to come back and do more projects for the university.”

Because, Pratt adds, “If we can better a patient’s life or contribute to a breakthrough in research or impact an incoming freshman’s college career? That’s pretty cool.”

Brian Pratt Campus Architect and Associate Vice Chancellor University of California, Irvine

Brian Pratt Campus Architect and Associate Vice Chancellor University of California, Irvine

Outlining the strategies, advancements, and new ways of thinking that will renovate the workforce and project delivery

The office doors are reopening for some. Elizabeth Fennell is mixing touchdown spots, collaborative spaces, and other novel approaches to keep Humana’s workplace buzzing.

By Frederick Jerant

By Frederick Jerant

When you hear the term “future work,” it’s easy to visualize George Jetson pushing buttons all day long. At Humana, it’s a bit more grounded—but the company still considers what’s to come just as much as the 1960s sitcom did.

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic were far reaching and had a particular impact on the American workplace. For many companies, working from home became the new normal, and a sprawling building packed with employees was no longer practical in every instance.

Elizabeth Fennell is the director of architecture and workplace design at Humana; she and her team have been tasked with guiding the company’s real estate usage and needs to accommodate the new fluidity in work patterns.

“Our general experience was like that of the rest of the country,” Fennell says. “We reopened in March 2022 but didn’t see a return to full capacity. In some ways, we are competing with home-office arrangements—people are comfortable and productive there and are saving many hours in commuting time.

“On the other hand, we need to deal with a mix of work styles,” she adds. “Some employees are full-time in the office, some work from home, and others are in a hybrid model. It can be hard to accommodate everyone.”

As a result, Humana is rethinking what the workspace means. “We began working with [global design firm] Gensler in 2021 to start building out templates for the future. We wanted to focus on what our associates will really need,” the director says. “For example, we expect there will be less focused time at individual workstations but more time devoted to collaborative meetings. We’ll need to have intentional spaces for that.”

A few related projects were underway before COVID19 struck, Fennell says, and were completed in time for the reopening. One key aspect of her team’s more recent work is the use of “teaming” rooms, which are multipurpose areas (of sorts).

“We’ve found that a lot of Humana’s project work has shifted to a cross-functional team model, sort of like a matrix, rather than individualized tasks,” she says. “We had dabbled in ‘coworking spaces’ before, but these flexible areas are designed for that purpose.”

And while typical conference rooms are reserved for an hour or two, these spaces can be occupied in terms of weeks or months at a time. They’re also helpful “touchdown spots” for associates who travel in for project-related meetings.

Some old-school methods are in the works too. “Sometimes, people can be distracted by the office

“We expect there will be less focused time at individual workstations but more time devoted to collaborative meetings. We’ll need to have intentional spaces for that.”

itself: ringing phones, conversations, and other common sounds. They can be distracted visually as well, so we’re looking into establishing ‘quiet zones’ with old-fashioned carrels in them,” Fennell says.

Fennell leads her internal team with an emphasis on relationship building. “Everyone here has been through a lot of changes,” she explains, “and I strive to understand their concerns by connecting with them in a sincere way—asking about their families, or just listening to their concerns. It’s the soft skills that not everyone focuses on, but they’re worth striving for. We can find joy in being together, and that can help you manage the hard things.”

The nature of “future work”—and current work, for that matter—leans heavily on technology. “Everyone seems happy with the idea of being able to work from home at least part of the time,” Fennell notes, “and

that has provided real value to many of our associates. But that also means even those in the office full-time will sometimes have to interact in a hybrid fashion.”

To that end, Humana is exploring ways to make its communications technology easier to use, and compatible with everyone’s needs. The company is even modifying presentation rooms to be more video-friendly.

“We’ve taken some cues from the home experience,” Fennell explains. “Associates often have bookcases or artwork as backdrops, rather than plain walls, for more visual appeal. We want to do similar things, so we’re looking at more attractive backgrounds and using lighting that meets the particular needs of video conferencing.”

She adds that no detail is too small; many of these rooms will have U-shaped seating arrangements to ensure that all participants are visible on-screen.

▲ The stair lounge in Humana’s Waterside building. Andrew Kung

▲ The Refill coffee shop in the lobby of Humana’s headquarters building.

▲ The Refill coffee shop in the lobby of Humana’s headquarters building.

“Everyone here has been through a lot of changes, and I strive to understand their concerns by connecting with them in a sincere way. . . . It’s the soft skills that not everyone focuses on, but they’re worth striving for. We can find joy in being together, and that can help you manage the hard things.”

▲ The open huddle space for employees to collaborate in the Waterside Building.

Humana’s Louisville, Kentucky, headquarters underwent some major renovations in 2021. Highlights include:

• A reimagined traditional conference center. Humana will host various strategic meetings in spaces distributed over four floors, which offer a visual break from the typical corporate decor.

• A major revamp of its original stone-andmarble design by Michael Graves. “It felt more like a bank or law firm,” Elizabeth Fennell says, “so we warmed and softened it with inviting seating, a greeter at the front door, and some visitor amenities right at hand.”

• An upgraded exterior courtyard. Employees find themselves among trees, benches, tables, and casual seating to facilitate working in fresh air.

▼ The second-floor Coffee Point in the Exchange located in Louisville, Kentucky. Andrew KungFennell is also charged with broader responsibilities within the corporate real estate department, including the management of space, designs, architects, furniture vendors, and branding signage.

“We’re working with Gensler to develop guidelines that will let us accommodate technology, spaces, and the overall ‘look’ of our properties,” Fennell says. “Our intent is to have a certain consistency from space to space so you’ll always know you’re at a Humana property, whether it’s a clinic, sales office, or pharmacy. But we also must be flexible enough to accommodate the various needs of our teams across the country.”

Hydropower facilities in upstate New York operated by Brookfield Renewable.

At Brookfield Properties, Michael Daschle is focused on one thing: bringing improvements to his company, its communities, and the world

With 325 million square feet of commercial space, 65 million square feet under development, and more than 750 properties around the world, Brookfield Properties has become one of the largest alternative asset managers on the planet. The company’s expansive portfolio includes office buildings, retail spaces, multifamily housing, hospitality spaces, logistics facilities, and mixed-use properties including recognizable high-rises that dot major metro skylines.

But Brookfield isn’t content simply growing, expanding, and increasing revenue. The company is harnessing real estate’s unique power to build a better world—one that benefits individuals, businesses, and communities alike.

As senior vice president of operations, Michael Daschle leads environmental, social, and governance (ESG) activities for the company’s New York City office portfolio. He is also Brookfield’s director of energy and sustainability, the lead for renewable energy procurement across the entire US, and the cochair of a global renewable energy advisory committee.

Daschle came to Brookfield in 2018 after completing an MBA in real estate at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania and working for another prominent New York City company, Tishman Speyer. At Brookfield, he started to look into optimizing how the company powers its buildings, manages its waste, and mitigates the negative impact of its properties.

“I started to specialize first on the E side of ESG, but we always had a plan to move more strongly into the social and governance areas as well,” he says. Over the past couple years, the ESG team has also developed a comprehensive plan to help ensure Brookfield supports its communities, promotes employee well-being, and adheres to strict ethical standards.

In the past 25 years, Brookfield’s sister company, Brookfield Renewable, has installed enough green power assets to power all of London and aims to double what is already the largest private renewable power business before the end of 2030. The availability of so much renewable energy will help Brookfield Properties meet its commitment to achieve a 50 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions on its way to achieving net-zero carbon status by 2050.

“Michael is an innovative individual whose vision is one of the key reasons why Brookfield Properties’ One Manhattan West is now powered by 100 percent renewable energy,” says Stephen Gallagher, chief commercial officer of Brookfield Renewable US. “With his leadership, Brookfield Properties is well situated to achieve

its carbon neutral goals, and we look forward to our continued partnership.”

Achieving net-zero status by 2050 is a lofty goal, but Daschle isn’t one to back down from a challenge. The Colorado native and nephew of a prominent senator from South Dakota enrolled in the United States Military Academy at West Point, where he studied philosophy and environmental engineering.

In his free time, Daschle ascended tall peaks with other cadets as the head of his mountaineering team. When it came time to select a military branch, he

“I started to specialize at first on the E side of ESG, but we always had a plan to move more strongly into the social and governance areas as well.”

SixSixty Fifth Avenue, located in the heart of Midtown Manhattan, is undergoing a $400 million redevelopment that includes a brandnew façade featuring 11-by-19-foot glass units, the largest ever used on a skyscraper.

chose Army Aviation. As an army captain, Daschle flew Chinook helicopters during deployments in Iraq and Afghanistan and taught Unmanned Aircraft Systems as a company commander.

When he transitioned out of the military, Daschle found new purpose in business development and asset management at large New York firms. In these roles, he was able to advocate for environmentally sound policies and effect some level of change. Now, at Brookfield, Daschle has the chance to do much more.

“Brookfield Properties has a massive portfolio of properties and has the unique ability to lead by example and influence others in what we do,” he explains. “We see ESG as a way to distinguish ourselves, do something good, and create long-term growth all at the same time.”

This approach is designed to address the interests of all Brookfield stakeholders including employees, tenants, business partners, residents, and communities. “We are creating spaces where people want to work, live, and play,” Daschle says. “Communities want Brookfield in their neighborhood because we do things that support people and provide value.”

As a fully integrated developer, Brookfield can harness the power of multidisciplinary teams to deliver unique spaces that anchor and elevate their surroundings.

One such property is SixSixty Fifth Ave. The prestigious Manhattan address is becoming the Big Apple’s most desirable workspace thanks to a $400 million redevelopment of the 39-story office building, which has 1.2 million square feet of commercial space. The plan boasts impressive design features and sustainable elements working in concert. Single-pane glass units spanning 11 feet by 19 feet will grace the façade, and the building hosts exclusive outdoor terraces, dramatic atriums, and sprawling interiors.

Seventy-five percent of construction waste will be recycled while the building will achieve a 40 percent reduction in water use. Additionally, teams are planning for LEED Gold V4 certification. Now, all core Brookfield developments are built to at least LEED Gold standards.

Efforts to enhance social and governance initiatives complement these environmental achievements. Brookfield is investing in diversity, promoting wellness, and empowering its employees. Leaders are now developing more objective criteria for each job description and tracking the ethnicity of candidates.

Half of Brookfield’s new hires and 41 of all promoted employees in 2021 were women. At least 62 nationalities and 32 spoken languages are represented in the workforce, which is 48 percent non-white.

The company also offers six employee engagement groups and recently launched Brookfield Cares, an official social responsibility program that drives philanthropic activities and gives employees the chance to volunteer.

Additionally, Brookfield is making strides when it comes to governance. Daschle and his counterparts have implemented antibribery policies, codes of conduct, data protection and cybersecurity programs, and business practices that eliminate discrimination, hold partners accountable, and protect human rights.

These steps, when taken together, yield dramatic results. Brookfield has 27 properties in New York; 28 in Washington, DC; 2 in Pittsburgh; 2 in Chicago; 1 in Nashville, Tennessee; 10 in Houston; 5 in Denver; 1 in Seattle; and 14 in California (Los Angeles, San Francisco, and San Jose), with many more in active development. With an ESG blueprint in place, Brookfield can now build upon a solid foundation.

Giovanni Lepori is taking Rothy’s to retail locations nationwide as the popular fashion company continues working to reduce its carbon footprint

By Zach Baliva

By Zach Baliva

When Stephen “Hawthy” Hawthornthwaite and Roth Martin’s company launched in 2016, it offered exactly two products: the Flat and the Point. Both were women’s shoes made with single-use plastic and sold only online. The company was Rothy’s, a trendy and sustainable fashion outlet that now includes other shoe designs as well as handbags and accessories for men, women, and children. The brand is also expanding from the digital space into brick-and-mortar retail.

As vice president of global retail development, Giovanni Lepori is tasked with making a beloved digital brand physical. He’s doing that by importing Rothy’s culture and aesthetic into his design choices and honoring the company’s foundational commitment to sustainability.

Rothy’s has been on a meteoric rise, thanks in part to celebrities, fashion critics, and fans praising its products for their undeniable comfort, smart style, and positive social impact. They’ve also praised the budding lifestyle company for its entrepreneurial spirit and fast-paced innovation. In 2021, TIME listed Rothy’s among the most influential companies of the year.

What makes the company so innovative? After seeing firsthand the alarming amount of waste produced by the footwear industry, the founders of Rothy’s set out to produce an eco-conscious shoe by perfecting the “bottle to shoe journey.” Using thread spun from recycled plastic bottles, Hawthornthwaite and Martin harnessed the power of 3-D knitting to create a durable and comfortable shoe made with almost zero waste.

“Rothy’s is creating a shoe in a totally different way,” Lepori says, adding that the traditional method of building a shoe from cloth or leather produces excess and unused scrap material. Understanding the importance of transparency and traceability, Hawthornthwaite and Martin also set out to build their own factory, ensuring that every point on the journey, from design to production, was handled in-house in a sustainable way.

The lightweight, flexible shoes are machine washable. To date, Rothy’s has converted more than 146 million plastic bottles into shoes and used more than 490,000 pounds of ocean-bound marine plastic for its accessories. The company is also hoping to achieve full circularity in production by the end of 2023. Instead of creating waste like other apparel companies, Rothy’s will find ways to not only create products from recycled materials but also recycle those products.

The focus on sustainability at Rothy’s has drawn companies like Trinseo, a global materials manufacturer, to partner with them. “We are looking ahead to

▼ The exterior of a Rothy’s storefront in Atlanta, Georgia.

“Rothy’s is creating a shoe in a totally different way.”▲ Rothy’s lightweight, flexible shoes are machine washable.

our next decade and beginning an exciting new journey to transform our company into a specialty materials and sustainable solutions provider,” says Frank Bozich, president and CEO of Trinseo. “Partnering with sustainability-focused brands pioneering within their category, such as Rothy’s, is the perfect journey to progress together.”

Lepori, who was born in Florence, Italy, has worked for top brands like Prada and Dior. He’s helping the company grow its retail footprint, which started when Rothy’s opened its first boutique on Fillmore Street in San Francisco’s Pacific Heights neighborhood in 2016. Since then, it’s added 13 stores and will expand to reach a total of 16 by the end of 2022.

The physical stores give Rothy’s evangelists and curious skeptics alike the chance to touch, feel, and try on the unique products. As the company moves away from its original online-only model, Lepori is developing the offline experience and creating touchpoints that represent the physical manifestation of Rothys.com.

He’s accomplished that by focusing on sustainability in both design and format. Lepori is using the same recycled materials from Rothy’s shoes to cover

“This is a company that’s always had the courage and the vision to try things nobody else will do.”Giovanni Lepori VP of Global Retail Development Rothy’s ▼ Lepori uses recycled materials from Rothy’s shoes to cover benches and other store surfaces.

▲ Lepori is creating in-store touchpoints that represent the physical manifestation of the Rothy’s website.

▶ A Rothy’s store in Pasadena, California.

▶ A Rothy’s store in Pasadena, California.

▼ Wood panels cover magnetic walls and thin moveable shelves that display a smart and carefully chosen product assortment.

▶ One of Lepori’s goals with flexible designs is to “tell different stories in different ways.”

benches and other surfaces in each store. Forest Stewardship Council-certified wood panels cover magnetic walls and thin moveable shelves that display a smart and carefully chosen product assortment. Lepori says each location is a “blank canvas” that can be reconfigured quickly as associates swap out merchandise, dial inventory up and down based on demand, and “tell different stories in different ways.” A short lead time and control over its factory allows Rothy’s to avoid overproduction and reduce waste in the supply chain.

Rothy’s demonstrated the influence it can have in this space in the lead-up to the 2022 US Open tennis tournament. The company introduced a limited edition special collection consisting of shoes, a hat, a visor, and bags made from 72,000 Evian water bottles gathered from the same event in the previous year. Lepori expects the company to try more daring initiatives in the coming years. “This is a company that’s always had the courage and the vision to try things nobody else will do,” he says.

The future is both green and bright for Rothy’s. In late 2021, its leaders announced a cash infusion

from Alpargatas, which gave the Brazilian owner of Havaianas a 49.9 percent ownership stake in the company. The young brand has a cult following and more than 2 million customers. Lepori is helping Rothy’s put its best foot forward as it moves deeper into the physical retail environment.

Trinseo , a specialty material solutions provider, partners with companies to bring ideas to life in an imaginative, smart, and sustainability-focused manner by combining its premier expertise, forward-looking innovations, and best-in-class materials to unlock value for companies and consumers. Trinseo’s approximately 3,400 employees bring endless creativity to their efforts to reimagine possibilities with clients all over the world from the company’s locations in North America, Europe, and Asia Pacific. Trinseo reported net sales of approximately $4.8 billion in 2021. Discover more by visiting trinseo.com and connecting with Trinseo on LinkedIn, Twitter, and Facebook.

Susan Stearn draws on community-inspired design elements to enhance the experiences of visitors and employees alike at Rush University Medical Center

By Donald LiebensonTalk about having your career journey mapped out for you. Susan Stearn, senior construction project manager at Rush University Medical Center, had excellent directions when she started out.

Her father was a cartographer for Rand McNally; he produced some of the company’s most iconic road atlases and coffee-table books, including the International Atlas. Her mother started as a social worker and then became a residential real estate broker.

“Our household always had an emphasis on visual arts,” Stearn says. “My father was also a silk screener. There was always a Better Homes & Gardens magazine around with the renovation before-and-after shots. I just loved that stuff. I grew up in Glenview, Illinois, outside Chicago, and our family used to go downtown to look at the architecture. Exploring the way cities were put together always intrigued me.”

This made her college counselor’s job easy. “He said to me, ‘You love the arts and I see that you are good at math. How about architecture?’ And here I am. One thing led to another.”

Stearn attended the Architecture School at University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and earned her master’s degree in urban planning and policy at the University of Illinois Chicago.

“I always liked the big picture, so when project management jobs came my way, those roles became my career path,” she says. “I got my communication and sound negotiating skills from my mother, and these allowed me to progress quickly on the business side of architecture.”

The first 20 years of Stearn’s career were spent in the commercial real estate sector, where she directed the architecture and interior design for shopping malls. “My goal was to improve on the cookie-cutter shopping center experience to make sure each mall’s common Courtesy of Rush University Medical Center

“I always liked the big picture, so when project management jobs came my way, those roles became my career path.”Susan Stearn Senior Construction Project Manager Rush University Medical Center

area was unique to the town it was located in by using local artists and relevant finishes and materials,” she says. “Little did I know that this background would come in handy in my next career in healthcare.”

Stearn works under the umbrella of Rush’s facilities group in the capital projects department. “I wear many hats,” she says. “In the past, I did project management and headed up Rush’s offsite ambulatory build-outs (specialty clinics), including Chicago’s River North, South Loop, and Oak Park locations, among other onsite projects. I’ve now taken on master planning campus space for clinical and administrative uses, and creating and updating design standards.”

Stearn describes her role as that of a chief experience officer (or, as she puts it, “a lowercase CEO”) and is assembling her FX (facilities experience) team to round the hospital common areas and keep up with required changes and maintenance. “In large and small ways, I work to make the campus environment better for visitors and for employees,” she says. “Visitors are here a few hours or a few days at a time, while employees are here every day. And in healthcare, many employees are here in the wee hours of the morning keeping things running. I work to make sure that projects and improvements that affect employees get attention and that we receive design input from the actual user.”

For example: behind-the-scenes areas that support patient spaces, such as janitors’ closets, security officer and environmental services locker rooms and break rooms, and administrative offices are all key to keeping employees engaged.

To foster community engagement, Stearn looks at outdoor areas as a canvas for public art. She is currently working with the Illinois Medical District Arts Council to assemble potential mural locations on the Rush campus for local artists to paint.

In her near-decade at Rush, Stearn has also sought input from healthcare practitioners. “I recently became aware that the rooms for residents on call—another seldom-acknowledged set of spaces—were in disrepair. I worked with the graduate medical education group, developed a criteria for the rooms, and outfitted each with new blackout shades, furniture, and lamps.”

The Rush campus has 22 buildings, the oldest of which was built in 1912. The newest is slated to open this year. “I am working to bring all buildings up to the level of that newest one for a ‘One Rush’ look and experience,” Stearn says. “Rush has some of the best medical care in the country; the physical environment should reflect that.”

She has also been partnering with Rush’s philanthropy and employee wellness groups to convert a donor’s COVID-19 gratitude funding into a large piece of beautiful stained glass with images of nature and flowers to be hung in a prominent public corridor.

Stearn receives enormous satisfaction from her job. “The people at Rush are a diverse and exceptional group,” she says. “Every day is different, and I learn something new from everyone and every project.”

We are proud of our partnership in helping you propel your organization forward by bringing to life the spaces and environments that are designed precisely for your purpose.

-Susan Stearn

Setting the stage and implementing the building blocks for what will soon be state-of-the-art facilities and designs from difference makers in the building industry

A seasoned construction professional, Edward Nystrom has always catered to the needs of his clients. When he found a home in hospitality, he never looked back.

By Will Grant

By Will Grant

What has kept Edward Nystrom in hospitality for the majority of his career? The senior vice president of design, construction, and project management at Hospitality Project Advisors and Driftwood Hospitality Management has always made it his primary objective to cater to his clients and provide services that satisfied their needs. The hospitality industry was an obvious choice for him.

“I have always been very concerned about my clients’ needs and do whatever it takes to provide services to satisfy the client while building a successful project,” Nystrom says. “When I started doing hospitality projects as a contractor, I quickly realized that hotels do whatever it takes to satisfy the guests, so I felt like we were very much aligned.”

Driftwood’s portfolio is packed full of dreamy getaways like the Curio Collection by Hilton, the Scottsdale Resort at McCormick Ranch, Hilton Cocoa Beach Oceanfront, Margaritaville Lake Resort Lake of the Ozarks, San Diego Marriott Mission Valley, Canopy by Hilton Tempe, and Flamingo Margaritaville Beach Resort Playa Flamingo. The company currently has 75-plus hotels, 27 brands, and 14,500-plus rooms under its banner, and Driftwood only continues to expand.

Nystrom has been part of that incredible growth since joining the company in 2012, but his design and construction roots go much deeper. Having worked in his family’s construction business during his college years, he knew he wanted to pursue a career in the construction industry.

“I went to college thinking I wanted to become an architect but quickly changed over to building construction and eventually started my own general contracting company,” Nystrom explains. “After a short stint in residential construction, I needed a faster pace, so I moved into building restaurants and high-end retail stores. I thought this was my sweet spot until I was given the opportunity to do a hotel renovation. It was the fast-paced schedule and the complex coordination that challenged me, and the rest is history.”

He then transitioned from contractor to the owner’s side of hospitality, working on exclusive golf resort properties and collaborating with national hospitality companies. It was in that capacity that he met Driftwood Hospitality Management. After they completed several successful projects together, Nystrom joined the Driftwood team as an “army of one.” Since then, he has not only grown his team to nearly 15 but also cultivated a reputation for running a team that’s capable of pulling off major renovations quickly—which is no small feat.

“Fast-paced renovation projects are always a challenge. It takes time to complete the design and get brand approval before we can start,” Nystrom explains. “It takes massive coordination and scheduling, and we have built a team that does a fantastic job of working with brands like Marriott and Hilton to create a streamlined process. In addition, we have built relationships with designers and contractors that we keep coming back to because they deliver excellent work. They understand how fast we move, and they’re built for it.”

Nystrom’s team recently finished renovations in Dallas; Houston; Appleton, Wisconsin; and Pittsburgh and is currently working on projects in Houston Galleria, the largest mall in Texas; Cocoa Beach, Florida; Scottsdale, Arizona; and San Juan, Puerto Rico. The Hilton at Cocoa Beach is being renovated for the second time in eight years due to the increased tourist attention brought about by SpaceX and NASA launches.

When it comes to new builds, Driftwood and its partners are currently working on a new $250 million Westin Oceanfront Resort just down the street from the Hilton Cocoa Beach, in addition to a mixed-use entertainment and hotel project called the Dream. They’re also planning a new build in San Juan, but Driftwood’s development team takes the reins on larger developmental projects so Nystrom can continue delivering fresh renovations.

The SVP says maintaining close working relationships with the company’s partners helps the organi-

zation to stay nimble and flow in the right direction. “When we commit up front, we already know that commitment can be fulfilled because our in-house procurement team has built long-term relationships with manufacturers and vendors,” he explains.

More broadly, Nystrom says his team’s success is the product of hard work and the opportunity to work with the same people for many years. “Keeping the team together is key!” Most of his project managers have been with him for at least five years, so they fully understand the complexity of a hotel renovation and are highly skilled in completing the project with minimal guest disruption.

“We have been lucky enough to have been able to sustain a steady pipeline of projects so we can keep our project managers flowing to the next project, maintaining quality, preserving budgets, and delivering successful projects,” he says.

While Nystrom enjoys his work renovating hotels, he admits that sleeping in hotels often doesn’t have quite the same allure it did a decade ago. So he and his wife bought an RV and ventured into the world of “glamping,” allowing them to spend quality time together when Nystrom isn’t heavily involved in a project.

Meanwhile, Driftwood is continuing to grow. Fortunately, Nystrom loves a challenge—and he was built for this.

“It was the fast-paced schedule and the complex coordination that challenged me, and the rest is history.”

◀ An aerial shot of the Margaritaville Lake Resort Lake of the Ozarks in Missouri’s Osage Beach.

BETTER THAN HOME

The Hilton Rockwall in Texas is a resort that allows guests to truly feel like they’re in their home away from home. The suites contain a separate living room, a workspace, and a half-bath that creates an atmosphere that goes beyond a hotel. Premier Hospitality USA helped bring this to life by manufacturing the seating for the suites, as well as the case goods. The case goods offer ample storage while still fitting as a natural part of the room itself. Do you want to see more of our projects? Visit our website at PremierHospitalityUSA.com.

StorageMart’s properties have wide loading bays, oversized elevators, and wide hallways to meet customers’ needs and expectations.

Brian Pierce Photography

Brian Pierce Photography

The Burnams have more than a family business: StorageMart is a self-storage empire

By Zachary Brown

By Zachary Brown

What started as a simple idea during a family vacation has turned into a thriving and profitable business with hundreds of locations across several countries.

In 1974, the Burnams were enjoying some time together in Texas on South Padre Island when the rain threatened to ruin their family vacation. Needing to pass the time, the patriarch, Gordon, initiated a conversation with the owner of a self-storage company. As they chatted, Gordon realized he could replicate his new friend’s success by starting a similar company of his own.

When they got back to Missouri, the Burnams started Storage Trust Realty, and later, StorageMart. Today, the company has more than 250 facilities in the US, Canada, and the UK. After more than two decades, StorageMart is still a family affair. Although Gordon passed away in 2017, the team includes Mike Burnam (president), Cris Burnam (CEO), and Weyen Burnam (managing director of real estate).

Weyen is responsible for growing and maintaining StorageMart’s portfolio through building, acquisition, and takeover. Since coming to the company in an official capacity in 2000, he’s helped it become one of the fastest growing in its category. He’s done that in part by focusing on key areas like customer experience.

StorageMart’s properties have wide loading bays, oversized elevators, and wide hallways to meet customers’ needs and expectations. StorageMart allows users to reserve units online and is implementing features like touchless access, fully enclosed bays, and automated doors with sensors.

Strong leadership, efficient operations, clear communication, and effective relationships with vendors help StorageMart maintain consistency as it

◀ While StorageMart offers online booking, its sales offices are brightly lit and available for in-person use.

ourtesy of Weyen Burnham

ourtesy of Weyen Burnham

grows across the United States and beyond. “We have a very lean team, so communication is a must when you’re going all over the country. You have to trust your team but also the outside contractors you’re working with,” Weyen says.

In 2016, StorageMart acquired Big Box Storage Centres’ 15 locations in southern England. Five years later, the company acquired Manhattan Mini Storage’s 18 locations in New York City to surpass 20 million net rentable square feet of storage and 200,000 units.

Now, the successful company known for clean, easy-to-use facilities is pursuing another goal—social responsibility. StorageMart is installing solar panels atop many of its self-storage properties. By 2035, five Northern California locations will have generated five million kilowatt hours of energy, which is nearly enough to power those five facilities without using energy from traditional sources.

The desire to limit impact to the planet is impacting StorageMart’s overall strategy. The company’s leaders

say they never look to build a new facility from the ground up. Instead, when it comes time to expand, they first look for used buildings or sites that can be redeveloped, repurposed, and reused.

That means they’ll face renovation costs, but those costs and the related energy consumption will always be lower when compared to requirements for a brandnew facility. “The way we see it, saving energy is not only good for the planet; it’s good for business once the initial installation costs have been recovered,” the company’s website says.

As StorageMart moves forward, the company continues to navigate challenges related to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and supply chain delays. “It’s also hard to lock in pricing for a steel structure or labor two years in advance of a project, so forecasting potential costs can be very difficult too,” Weyen explains.

He’s relying on his experience in single family, multifamily, industrial, and commercial projects to help him navigate the unusual era and putting in extra

work to predict the amount of people and time required for each job.

Teaming so many Burnams with long-tenured workers brings intangible results. Many veterans on the staff just know what a certain project needs. They understand that customers in rural Missouri have different habits and expectations than those in Manhattan, and they can cater their spaces accordingly. What Gordon and his wife, Mickey, started so many years ago is still going strong with four generations involved today.

In 2021, Janus International worked with StorageMart to revitalize an aging facility in Middle River, Maryland. At the time, this facility featured old, faded doors that were doing little to no good for the site’s curb appeal. That’s when Janus was pulled into the project to complete a full door replacement. StorageMart’s director of real estate, Weyen Burnman, says of the project, “The Eastern Boulevard project had been neglected for years, and by replacing all unit doors with Janus products we were setting our team up for success and providing our customers with top quality and secure doors.”

Congratulations Weyen Burnam and StorageMart for this well-deserved recognition in American Builders Quarterly Strickland Construction Company is proud to partner with you and looks forward to continued work together. Strickland provides preconstruction, construction, and post-construction services. To learn more please visit stricklandconstruction.com

Congratulations Weyen Burnam and StorageMart for this well-deserved recognition in American Builders Quarterly Strickland Construction Company is proud to partner with you and looks forward to continued work together. Strickland provides preconstruction, construction, and post-construction services. To learn more please visit stricklandconstruction.com

“It’s also hard to lock in pricing for a steel structure or labor two years in advance of a project, so forecasting potential costs can be very difficult too.”

Exploring new and renovated facilities across the industry, from buildings to work spaces, along with the people and companies behind these projects

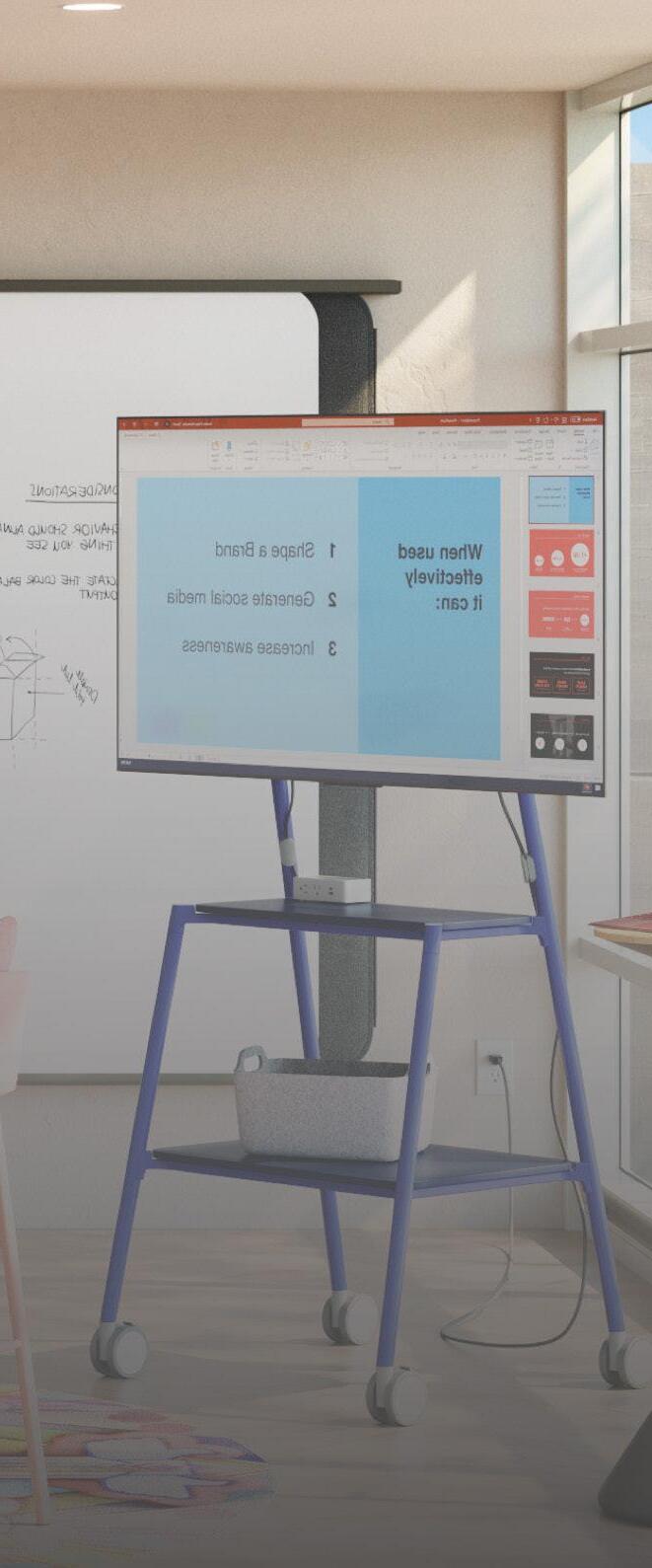

◀ Texas Children’s Hospital North Austin Campus will include an emergency center, urgent care, patient floors, healthcare core services, outpatient building, central utility plant, parking garage, and surface parking for pediatric and women’s services patient care.

In her role overseeing facilities development for the Texas Children’s healthcare system, Jill Pearsall takes a fluid approach to planning to ensure that she can pivot quickly when necessary

By Russ KlettkeJill Pearsall has a pretty good handle on the complexity of hospital systems. She’s the senior vice president of facilities planning and development at Texas Children’s Hospital, the largest system in the country serving pediatric and women’s health. The hospital is affiliated with Baylor College of Medicine, making it an academic teaching institution.

Texas Children’s, with its 897-bed inpatient care and outpatient system, is based in Houston; it’s now establishing its range of care in Austin, 180 miles away. Its large scale of operations means that one might expect its facilities management to be fairly corporate.

But visit one of the buildings, in a hallway where anxious parents and ailing children pass daily, and you can see something that makes it clear Pearsall hasn’t lost touch with the mission of the organization.

It’s dancing cows. Technically, they are sculptures of cows (named Fred and Ginger) in rhinestone outfits, raised up on hind legs, cutting a rug and larger than life.

Those cows were originally part of citywide fundraiser for the hospital, called CowParade, in 2001. Amid the vast array of best-in-class medicine and technologies is the kind of whimsy that patients and visitors love. Children with illnesses or injuries need something to make them smile, and the smart designers who work under Pearsall figured out a way to make that happen.

Pearsall, who trained as an architect, is responsible for much more than design. But she particularly delights in ribbon cuttings—that crowning moment when modern healthcare design principles come together to create a place for healing. In the last decade or so that has included bringing in more natural light for the benefit of patients and healthcare providers.

It also includes a programmed dimming of lights that helps calm patients so clinicians can do their work, and the use of acoustic materials in floors, ceilings, and walls to achieve a similar effect.

She speaks of the collaborative, “internally owned” nature of the culture at Texas Children’s, which makes it possible for her team to do what they do. It pervades the entire organization. Pearsall notes that the physicians go out of their way to be more engaging and less scary to the young patients, which contributes to this atmosphere.

But she also credits the CEO, who’s been with the hospital for more than three decades, for making this possible. Pearsall herself has worked there for two decades and helped it evolve—though she was impressed with the work environment from the very beginning.

“When I first started working here, I was surprised by the culture,” she says. “Everyone wants to be involved, wants it to succeed.”

This culture plays out in a very specific and important way for Pearsall, who is responsible for facilities development. “The biggest mistake we could make would be to write up a big, long-range master plan

▼ The hospital entrance for inpatient and outpatient care will be uniquely marked with undulating glass walls and a warm welcoming wood canopy for protection from inclement weather.

“The biggest mistake we could make would be to write up a big, long-range master plan and put a big bow on it.”Jill Pearsall SVP of Facilities Planning & Development Texas Children’s Hospital

and put a big bow on it,” she says. There are too many moving parts, too many variables, for anything to be perfectly predicted that far out.

The construction of huge facilities might take several years from conception through approvals, permitting, and construction. But there is, by nature, a lot of back-and-forth in that conceptual stage.

“In 2016 we started a facilities master planning group,” she says. It is made up of executives from finance, facilities, nursing, and other clinical specialties, who gather on a regular basis to discuss “everything from minutiae to strategy,” she says, describing it as a free-form exchange of ideas, likely costs, and priorities. “We have this uber-crazy spreadsheet with every great idea on it,” she notes, which remains fluid in response to all the dynamics a big healthcare system faces.

When pressed on the overall mission of facilities, Pearsall points out that the buildings have to exist before you can treat patients and the buildings need to respond to the care being provided. It’s clear she finds joy in not only creating those places for patients,

“When I first started working here, I was surprised by the culture. Everyone wants to be involved, wants it to succeed.”

▼ The outpatient building primary and specialty care services will have parking available in the adjacent parking garage.

employees, and visitors, but also ensuring that they’re safe and enable mental as well as physical health.

The biggest projects underway or nearing completion are the 52-bed, 5-story pediatric and women’s facility in North Austin, and an office building conversion to a women’s services outpatient facility in Houston, adjacent to the Texas Children’s Texas Medical Center campus.

The latter was built with white, precast concrete, not the “sunset red” granite on the exterior of their other buildings. To ensure that the building is identifiable as Texas Children’s, a clever solution was devised to apply a complementary paint shade to the concrete.

Pearsall manages to do more than oversee huge buildings full of twenty-first-century technologies to improve the health of children in Texas. She also volunteers with a program for fifth graders, showing them the diversity of careers they might one day follow into healthcare—including architecture and building.

One imagines that anything involving bejeweled dancing cow sculptures would show them how serious work can involve some fun as well.

When AECOM (known for projects like the World Trade Center, Hong Kong International Airport, and Chicago’s Millennium Park) acquired Hunt Construction Group (builders of the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center, Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport Terminal 4, and the San Francisco Federal Building) in 2014, it became one of the largest and most capable professional services firms in the world.

Since then, AECOM Hunt has built some of the most iconic venues, transportation hubs, healthcare facilities, and academic campuses of all time.

By Zach Baliva

By Zach Baliva

Today, the behemoth company has 51,000 employees and $13 billion in annual revenue. It’s active in dozens of countries, where its teams are leading design and construction of the NBA’s Intuit Dome, upgrading London’s infrastructure, building what is set to become the first dedicated offshore wind port in the US, engineering light rail transit projects in Canada, and creating the world’s largest indoor theme park (the size of 21 football fields) in Abu Dhabi.

While these complex projects may intimidate even the most talented industry professionals, Executive Vice President and South Region Manager Monte Thurmond remains unfazed. There’s not much he hasn’t seen in his 43 years with AECOM Hunt.

Although Thurmond officially started with Hunt after finishing college 1984, he joined the organization’s field engineering teams as a “grunt and gofer” in the fall of 1979 when he was still in high school. He got his laborers’ card, volunteered for leadership roles, and was the second shift supervisor at a manufacturing facility before graduating from Purdue University.

Thurmond says it was watching projects come out of the ground that first got him hooked. “There’s something rewarding about working in construction and being able to see the tangible results of all your hard work,” he says.

Over his decades in the business, Thurmond has also grown to appreciate the intangible results he can see as his company’s projects help stimulate local economies, introduce jobs to depressed markets, and bring joy to users’ lives.

After 40 years spent building the places where people gather, Thurmond is at his busiest. Part of that may be due to the COVID-19 pandemic. “People have

AECOM

look on what it takes to create some of the world’s most unique and complex venues

a new appreciation for being together and there is a heightened awareness of how special performance and sports venues are,” says the EVP, adding that AECOM Hunt is currently active in several university, entertainment, and transportation projects.

Danny Espino, owner and president of Critical Electric Systems Group, is proud to collaborate with Thurmond on a college campus expansion and renovation in Fort Worth, Texas. “Monte is a natural leader with many years of field and hands-on experience, which supports his thorough review of all pertinent details and risk scenarios on every one of his projects,” says Espino, adding, “We are confident our current AECOM Hunt project for the Tarrant County College District will be successful because of him and his team.”

By now, Thurmond is used to the grind. AECOM Hunt had five major, world-class sports arenas—SoFi Stadium, Coachella Arena, Intuit Dome, UBS Arena, and Moody Center—all underway at one time in 2021. Moody Center, home to University of Texas Longhorns basketball and other events, opened its doors on

Monte Thurmond EVP AECOM Hunt

▼ The expansion of Tarrant County College District’s southeast campus includes two new buildings with the renovation of classrooms, administrative offices, and laboratory spaces.

Monte Thurmond EVP AECOM Hunt

▼ The expansion of Tarrant County College District’s southeast campus includes two new buildings with the renovation of classrooms, administrative offices, and laboratory spaces.

April 20, 2022. It was Thurmond’s 29th sports project: he did a stadium expansion in the second year of his career and followed that up with a large arena before acting as project manager for a 20,000-seat venue.

In the early 1990s, Thurmond moved to Dallas and built facilities for the Mavericks, Stars, and Spurs on his way to completing 15 regional stadiums in the early 2000s.

Thurmond’s history in team sports informed his work and helped him appreciate the level of coordination and collaboration necessary to pursue common goals in construction. Each person on a building project has a unique task, but all those individual members must work together with one clear vision.

As he saw the importance in strong teams and lasting relationships, Thurmond developed a credo that’s remained intact throughout his long career. “All of us working together are smarter than any one of us working alone,” he says.

AECOM Hunt’s VP, Clint Binkley, praises Thurmond’s demonstration of these values. “Monte is tremendously involved behind the scenes: teaching, guiding, and providing constructive direction to the entire team with every project, from inception through closeout,” he says.