Ed Wall

Ed Wall

Ed Wall

Rockaway’s Housing Superstorm: Between Rising Waters and Climate Gentrification

This report presents the Rockaway’s Housing Superstorm project, the focus of a semester-long project-based seminar at the Harvard Graduate School of Design in the fall of 2024. It brings together concerns for coastal neighborhoods in New York City that are under threat from both rising sea levels and processes of gentrification. The report follows the three-part journey of the project: firstly designing community workshops, supported by the community organization RISE (Rockaway Initiative for Sustainability and Equity); secondly, developing a public space plan that connect areas of housing–in particular public housing–with Jamaica Bay; and thirdly, in the context of predicted sea level rises, forming longer-term spatial strategies that address needs for repair, elevation, and relocation. While many questions were posed through the semester, one concern has repeatedly reemerged: From planning the project to editing this report, we have consistently asked how we can develop fair and meaningful conversations that can empower the communities we are working with. This report describes our endeavors to achieve this.

Seminar Instructor

Ed Wall

Students

Chandler Caserta, Garrett Craig-Lucas, Randy Crandon, Bhavya Jain, Carlo Raimondo, Kirsten Sexton, August Sklar, Makenzie Wenninghoff, Allen Wang, Piper Claudia Williams, Mabelle Zhang, Benedetta Zuccarelli.

Seminar Guests

Kristin Baja, Rosetta Elkin, Anthony EngiMeacock, Martì Franch Batllori, Shannon Mattern, Deborah Helaine Morris, Sam Naylor, Helena Rivera, Jane Wolff.

Final Review Critics

Larry Botchway, Jeanne DuPont, Tawkiyah Jordan, Steve Koller, David Luberoff, Rosalea Monacella, Deborah Helaine Morris, Helena Rivera.

Gary Hilderbrand

As a topographical placename, Far Rockaway conjures varied and captivating scenes. It’s not far from anywhere today (though it may have seemed handily far from Manhattan, as a resort, when travel took longer). But Far distinguishes the place from Near Rockaway (now East Rockaway). I’ve sometimes wondered: Did Rockaway allude to vanishing rock? I did some digging. For the area’s pre-colonial inhabitants, yes, it did refer to a lack of rockiness. In the Algonquin language, it was something like “Reckouwacky,” the place of sands. Rockaway still has venerable beaches; a historic village of shops, services, churches, and synagogues; housing scales in striking juxtaposition from rows of tiny bungalows to dense high-rise apartment blocks; fishing, surfing, and other recreations along classic boardwalks; and a diverse demographic. All this has enormous appeal. Cool name, alluring place. Hindsight would say it might have been better to build elsewhere. But all this has made it a source of beach town nostalgia and, more enduringly, generational devotion to place.

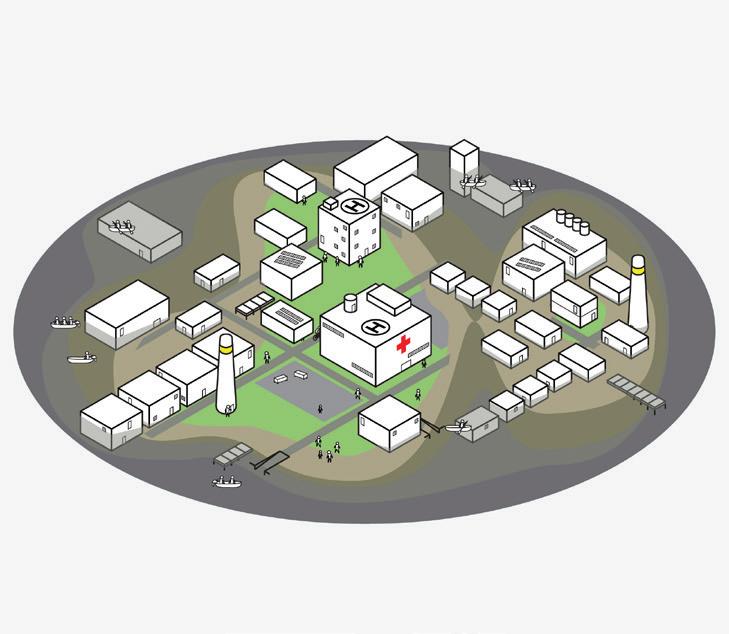

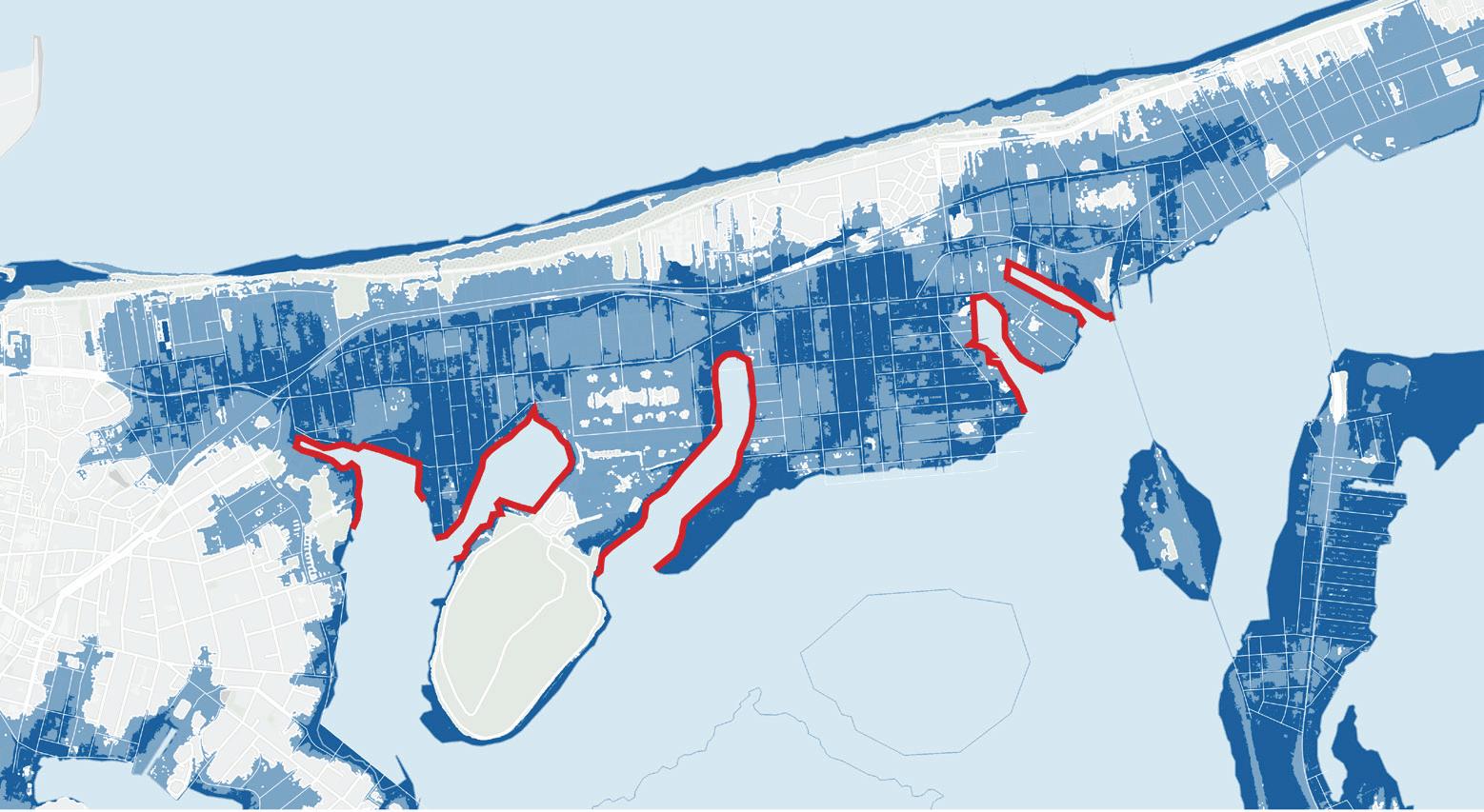

Many or most of the people who live there, and all these cultural assets, somehow presently endure the existential threat that comes with a changing climate. The weather is more turbulent, with winter and summer storms that are more frequent and more intense—with the certainty that much of it will be under water much or all the time in years to come. Superstorm Sandy’s massive damage in 2012 presaged this, unforgettably, with more than 1,000 homes and businesses destroyed. What forms of migration are needed? And how will any form of migration or rebuilding be equitably good for all?

Project-based seminars and studios in the Department of Landscape Architecture provide a platform for collaborative investigations into the urgent environmental, social, and climate-related issues of our time. Our intention with these studies is not to provide definitive answers but to probe carefully mapped out questions—as resolutely stated in this report’s narrative—and speculate on possible vectors for action. Our project outcomes are meant to be a generative compilation of robustly argued frames for how communities might prioritize actions that should—or must—be taken soon. And it’s made clear in this report that decisions around rebuilding, retreat, and adaptation of built space and its public realm take time, arduous debate, and cooperation. The everyday work of coping with frequent flooding can intrude on the care and rigor that comes with crucial planning.

III.

I’m deeply grateful to GSD Visiting Professor Ed Wall for the special energy and dedication he brought to this project and these students, his persistent and probing focus on design pedagogy, and his admirable clarity regarding the importance of active and repeated engagement with community members at Far Rockaway. He says it manifestly: “We have consistently asked how we can develop fair and meaningful conversations that can empower the communities we are working with.” That indeed is our aim. That ethic of care is invaluable within our professional degree curriculum and our engagement with stakeholders, and it will remain a durable good for these students as they move into the world to pursue sundry forms of climate adaptation.

Let me also extend my thanks to David Luberoff and Chris Herbert at Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing for the generous support of the studio and this publication. Gratitude as well to the many esteemed experts who helped inform or guide the effort. And special thanks to the good citizens of RISE, the aptly named group who shared so much with the students on their trips and in their final seminar review. We hope all at RISE feel you’ve received something valuable in return for your good work.

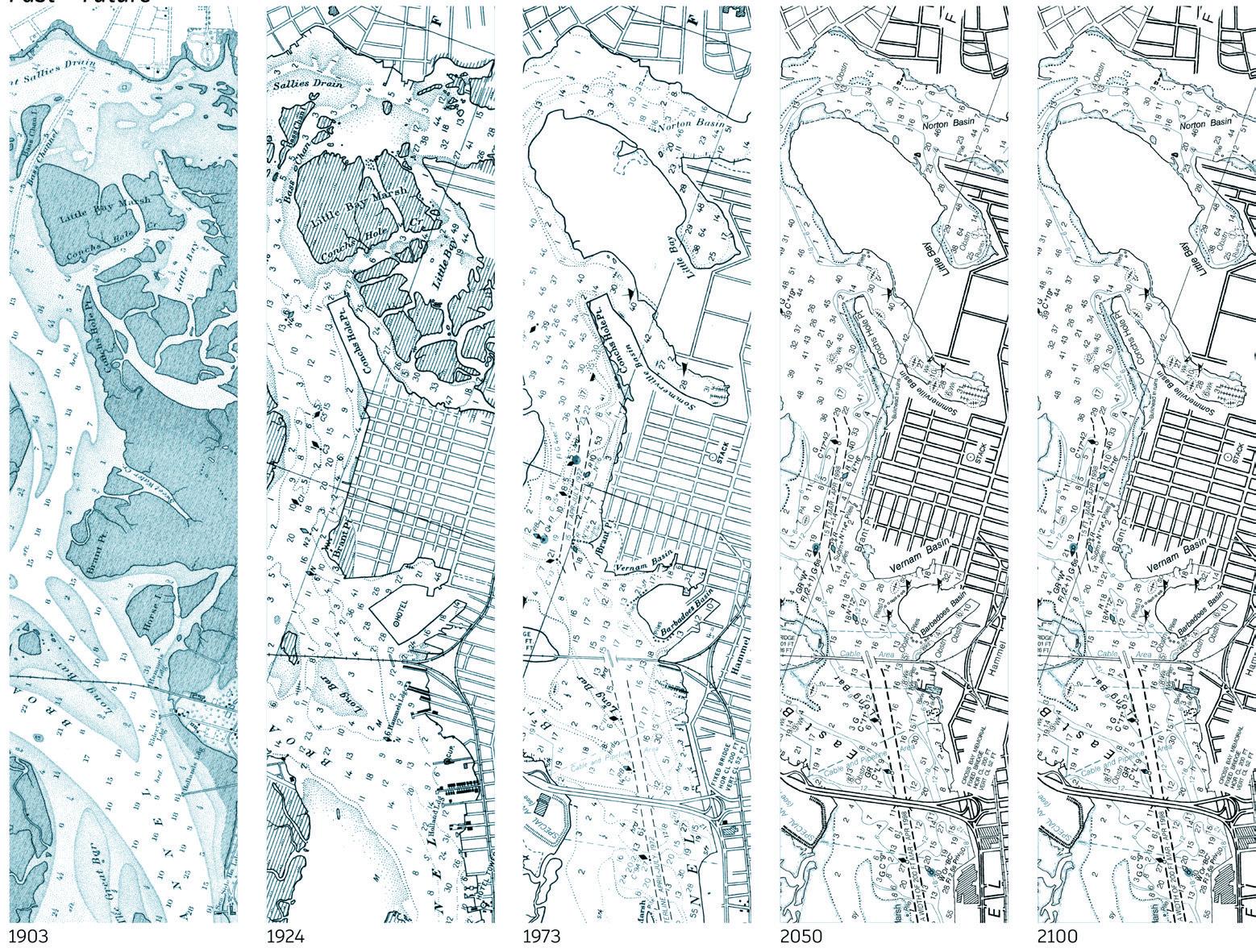

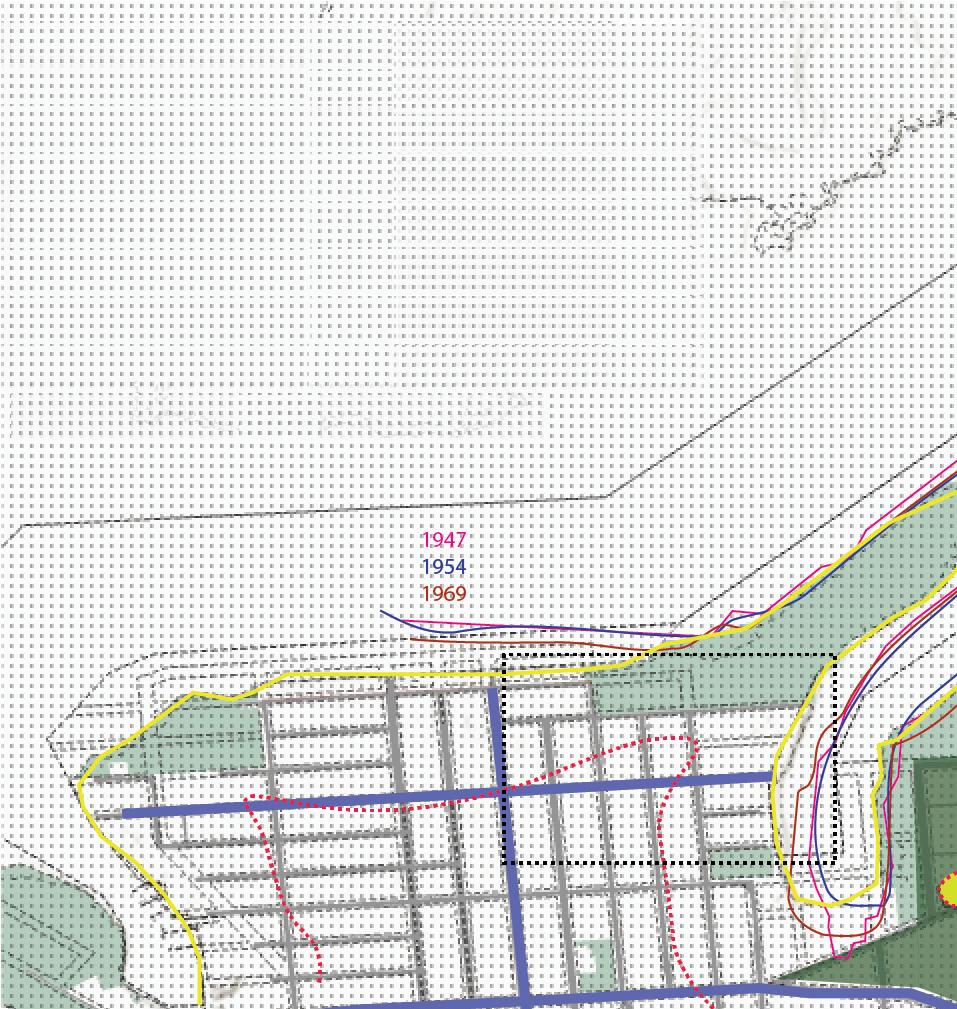

For over a century, New York City’s Rockaway Peninsula has been defined by displacement of residents from their homes, from eminent domain wielded by Robert Moses to the tidal surge of Superstorm Sandy. Displacement from the peninsula’s housing has also accelerated since 2012, due to homes damaged and destroyed during the storm, uneven support to repair and rebuild, and rising rents and real estate prices. Further displacement is expected as global warming causes flooding in neighborhoods across the peninsula.

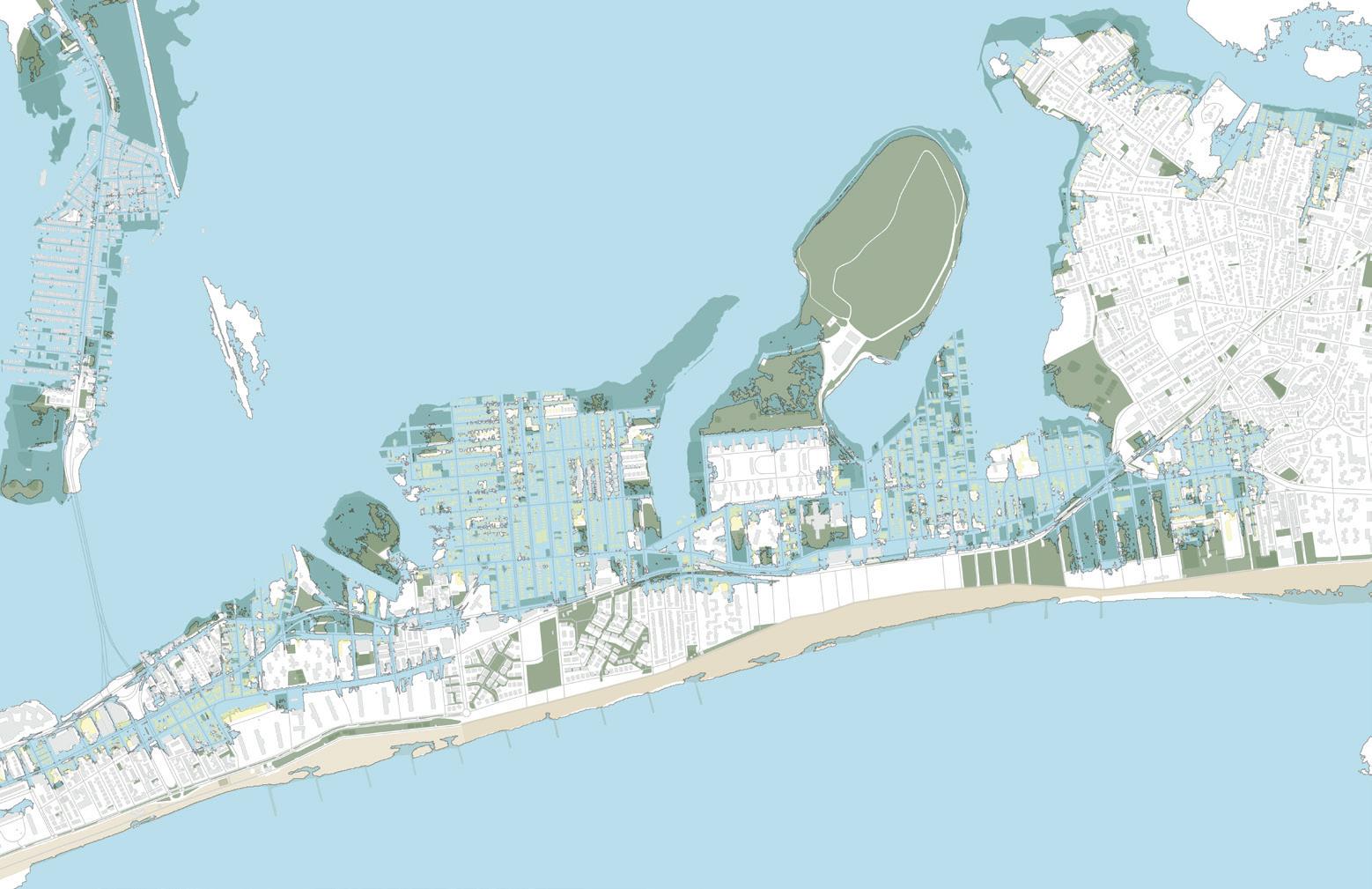

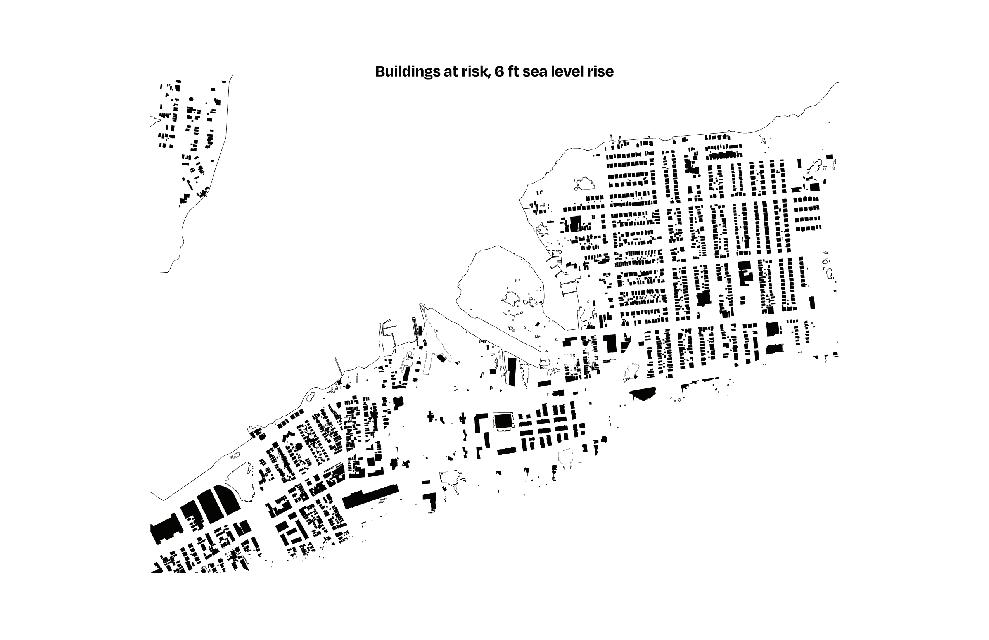

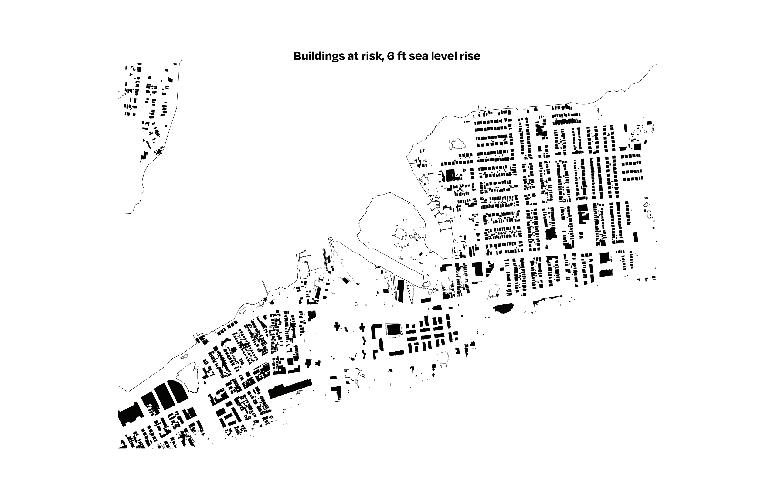

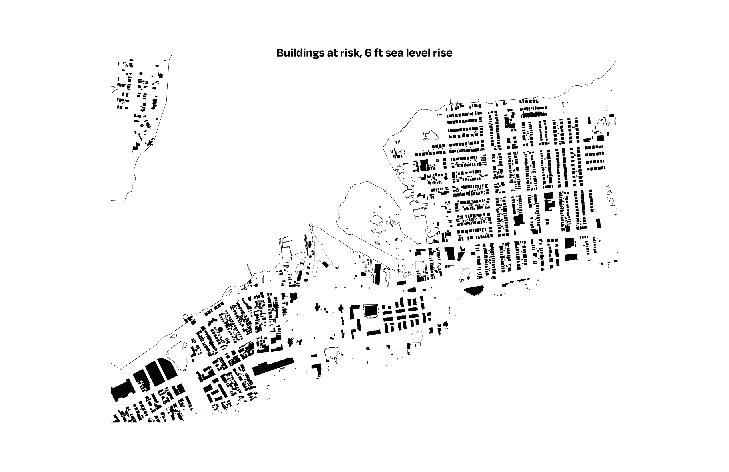

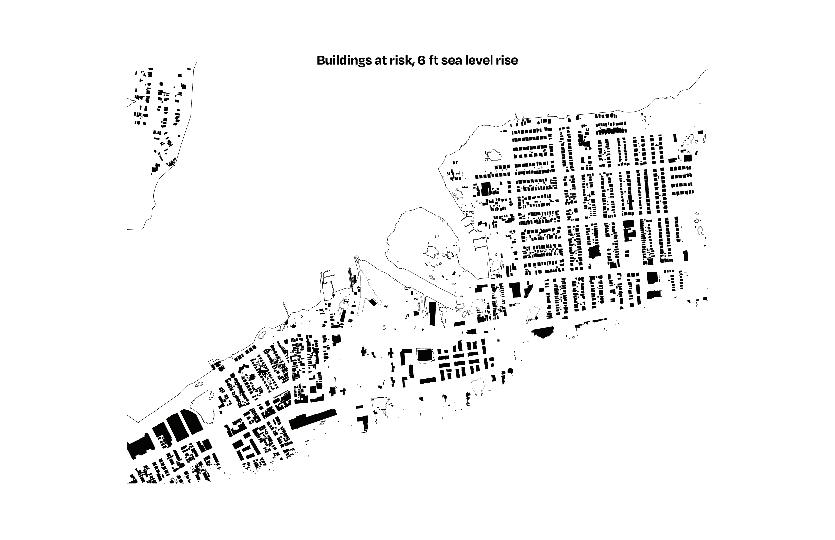

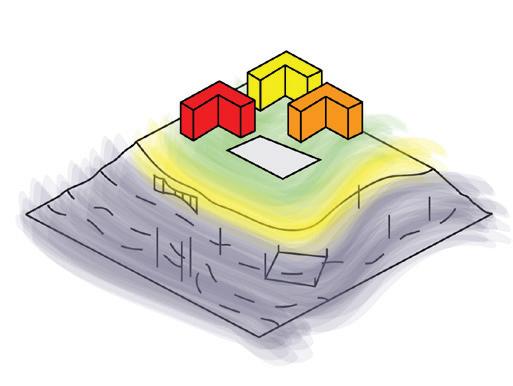

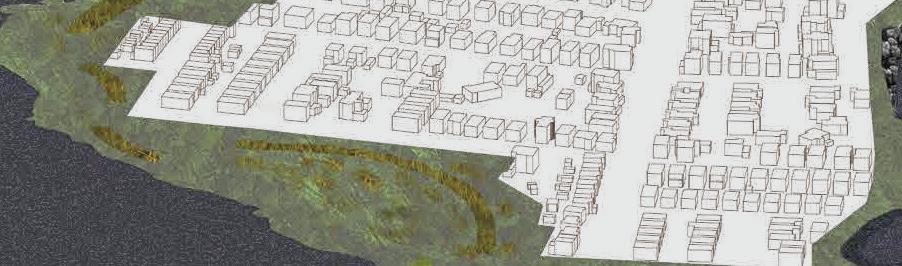

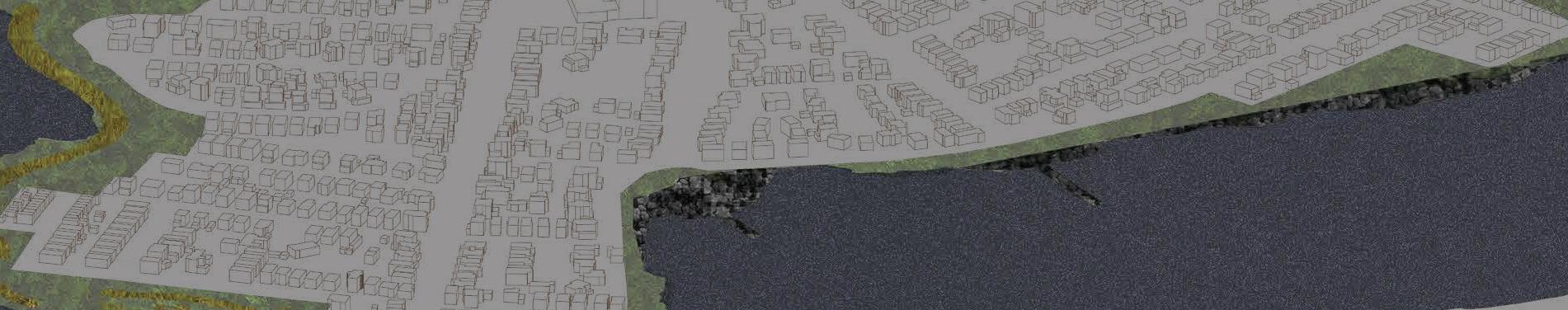

As relations between coastal waters and lands change through rising sea-levels, cloudbursts, and storm surges, life on the Rockaways will become increasingly challenged. It is expected that the peninsula will be inundated with tidal waters by 2100 and that inventive housing strategies of adaptation are needed, including repair, elevation, and even relocation. An expanded and resilient public realm will be essential to address decades of uneven development and to place community and climate justice at the heart of future designs.

The beaches, parks, and public housing of the Rockaway Peninsula have a strong presence and long history. However, they have also been used in the past to divisively separate neighborhoods and residents. A new public realm across the Rockaways will become more important in the coming decades as how and where people live and work is reconsidered. A new public realm has the capacity to provide a consistent ground of spaces, buildings, policies, and actions that put concerns for residents at the core of Rockaway’s future.

The Rockaway’s Housing Superstorm project aimed to address these concerns. The project was initiated by the Chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture at Harvard Graduate School of Design, Gary R. Hilderbrand; it was generously supported by David Luberoff and

Ed Wall

Chris Herbert at the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies; and it was made possible through a collaboration with Jeanne DuPont at RISE (Rockaway Initiative for Sustainability and Equity).

Through the semester, twelve students came together—across architecture, landscape architecture, and urban planning—to explore these layered challenges.

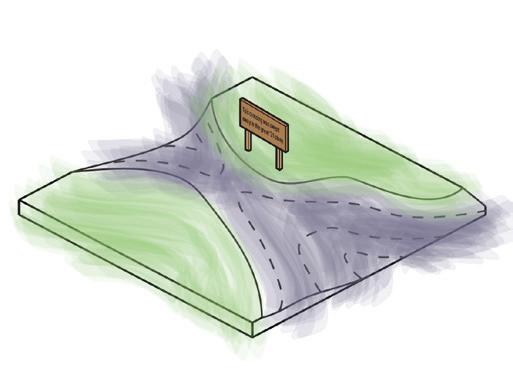

The project had three stages that reflected the priorities of these organizations:

• First, students engaged in conversations with residents. They designed community workshops that were hosted by RISE. Workshops brought together people living and working in the Rockaways and RISE’s Shore Corps high school students with students from the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

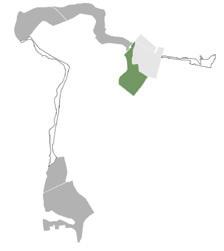

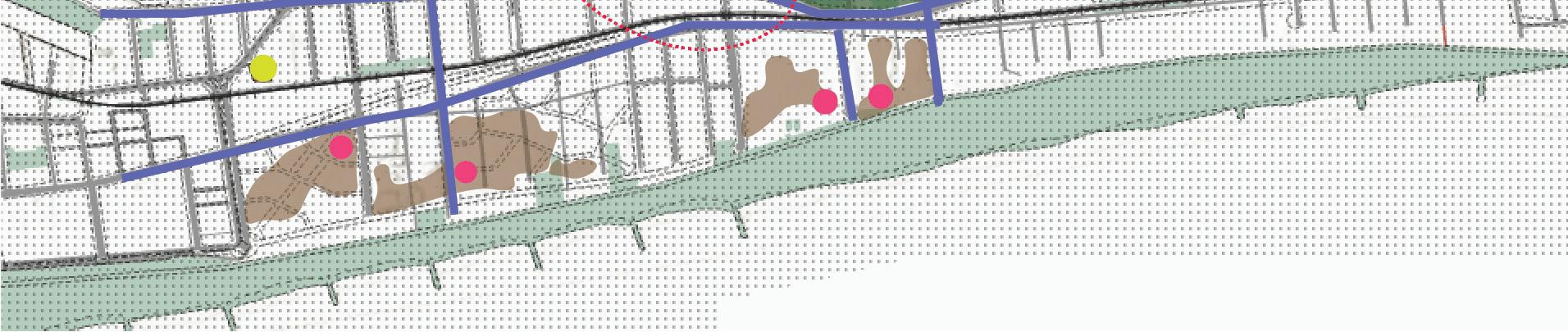

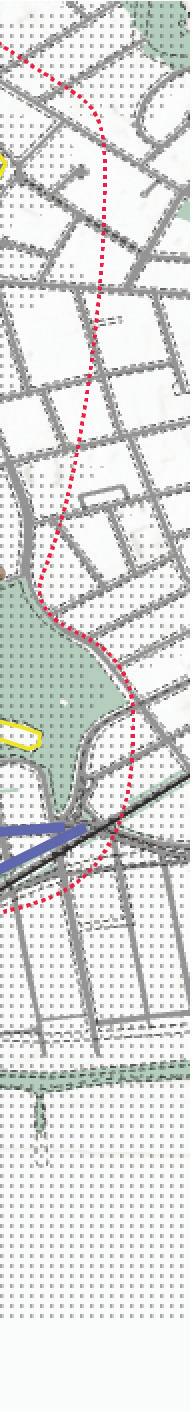

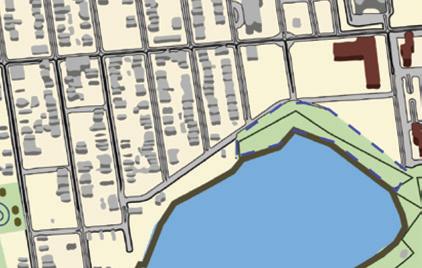

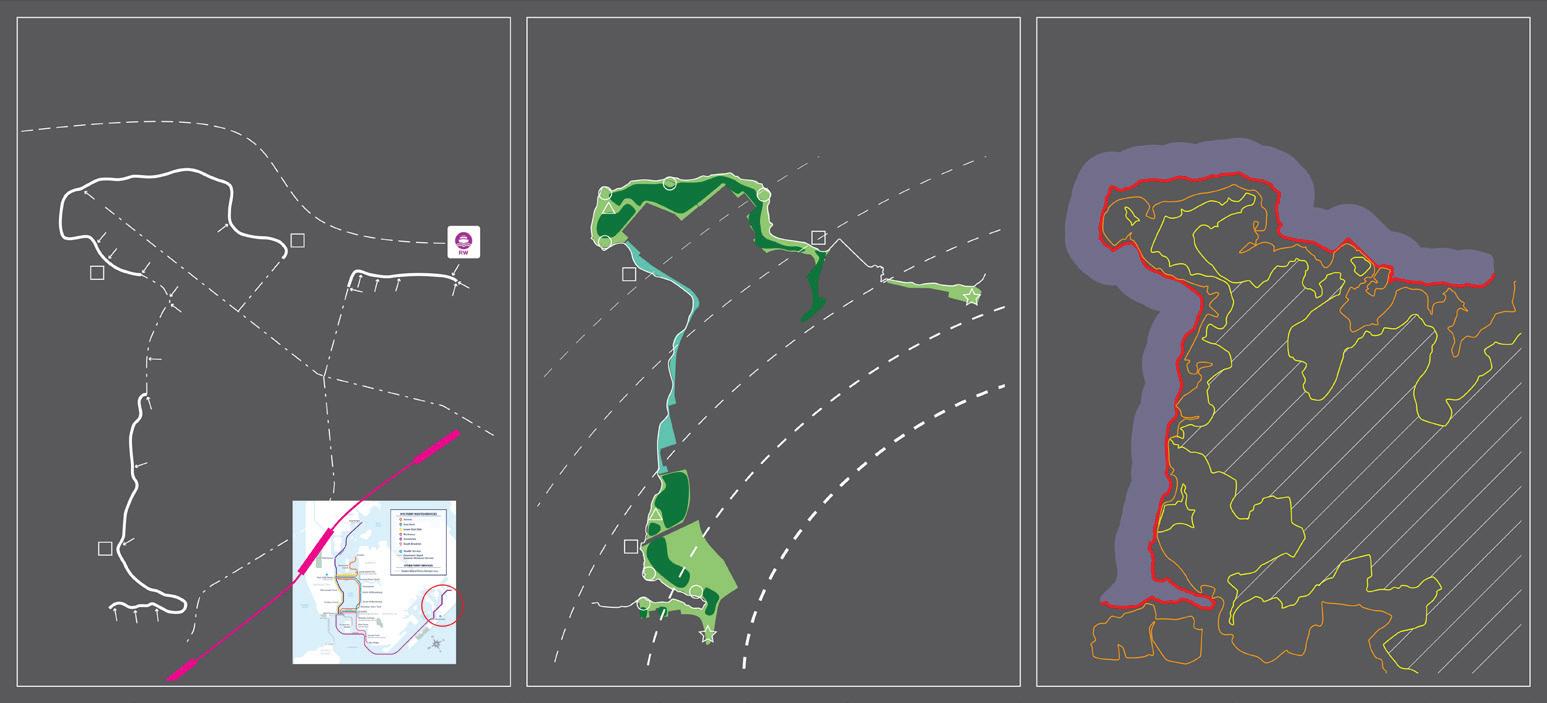

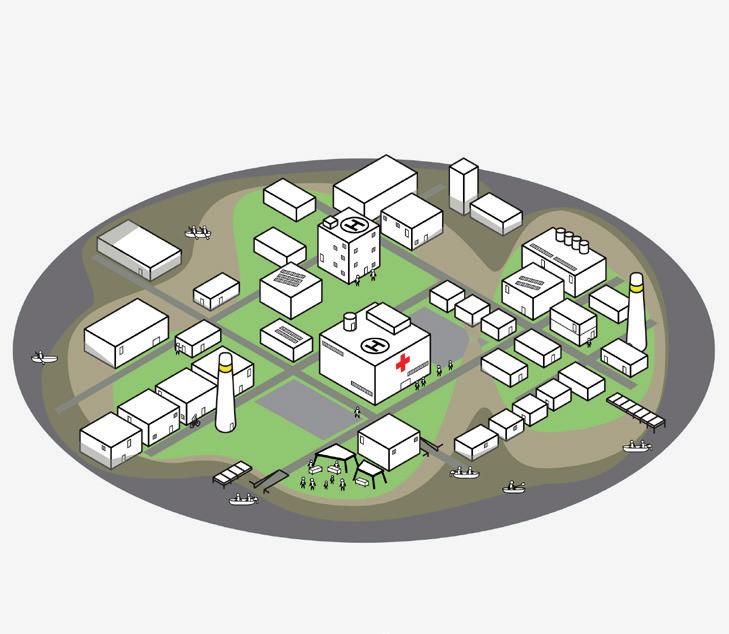

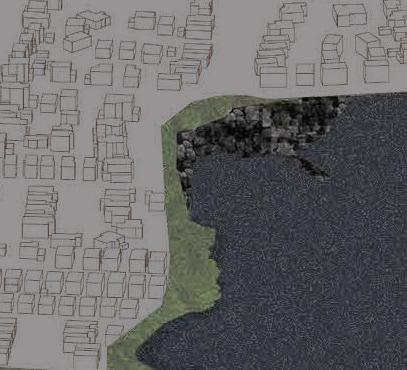

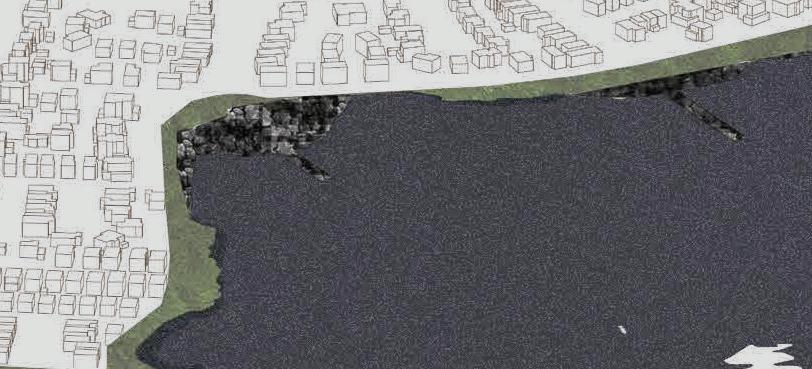

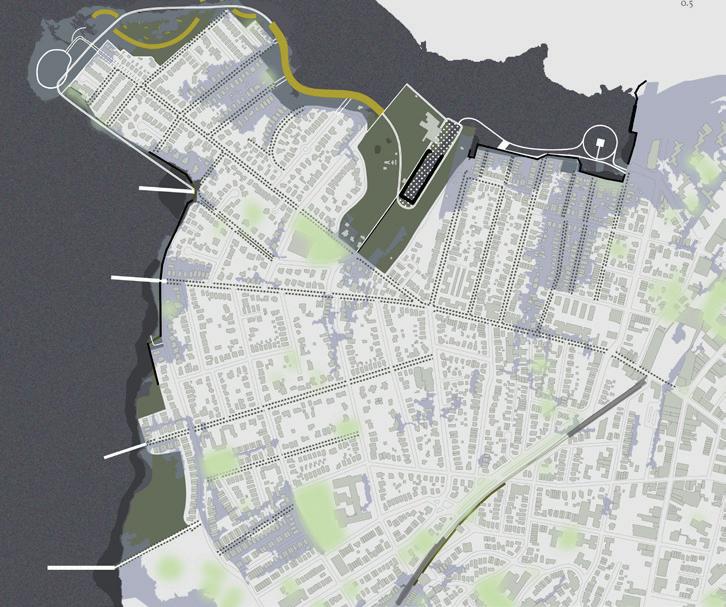

• Second, students developed public space design proposals connecting the Jamaica Bay waterfront of Far Rockaway with areas of public housing. These are neighborhoods that have historically been disconnected from the bay and are now increasingly experiences tidal flooding. It is also a coastline that, since Superstorm Sandy, has received limited attention compared with the Atlantic Coast on the other side of the peninsula.

• Third, students explored longer term strategies of repair, elevation, and relocation that would respond to rising sea levels. Concerns for housing included how residents’ lives were impacted by current and future flooding, from homes to neighborhoods, from car parking to boat moorings, from schools and libraries to public parks.

This report shares the designs of the students including the way that they worked together and with residents. It explains the approach that we took with the project and how students navigated the three stages of work. It describes the fieldwork and study trips that we took to the Rockaways as well as the conversations, workshops, and reviews with RISE and Rockaway residents. The report brings together the voices and concerns of students, guests, and critics through a glossary of terms that forms a common vocabulary. The main body of the report is structured around the student projects, including public space plans, housing strategies, and written design code for the future of Rockaway neighborhoods. The students embraced the complexity of this project brief as well as the magnitude of tasks needed to ground the project in meaningful ways with the community.

Our primary approach to the Rockaway’s Housing Superstorm project was to ground ourselves in the Rockaway Peninsula as much as possible. We recognized that to explore the site-specific impacts of gentrification and climate change we needed to spend time in the Rockaways and where possible with people who lived and worked there. As a group with variable familiarity with the Rockaways, it was necessary to develop relationships with individuals and organizations who were already living there.

The partnership that we forged with Jeanne DuPont at RISE (Rockaway Initiative for Sustainability and Equity) was essential to make the project possible. RISE provides civic engagement and youth development programmes that advance social equity and physical well-being, all with the aim of inspiring Rockaway residents to care for their environment and community. Since they were founded in 2005, they have successfully initiated several open space projects, including creating a 28-acre waterfront park on a site that was subject to illegal dumping.

Through three-months of planning with Jeanne, we found common ground between our pedagogical ambitions and a project that RISE wanted to explore. RISE were keen for us to develop public space plans that connected the Jamaica Bay shoreline to public housing–from Far Rockaway and Bayswater on the east of the peninsula through Edgemere, Arverne, and Rockaway Beach. We combined this focus with our overlapping ambition to explore the impacts of rising sea levels on neighborhoods in the Rockaways, from the current everyday flooding to the expected inundation of the peninsula by the end of the century.

This interdisciplinary project that involved the design of a new public realm and developing housing strategies started with planning

approaches to field methods and community workshops. The students designed interactive mapping tools to enable conversations with Rockaway residents. RISE supported us with hosting and publicizing a workshop where students and residents could meet. Working also with RISE’s Shore Corps high school students, the workshops gave a strong foundation of knowledge for the Harvard students to develop their projects. The generosity of RISE and the Rockaway residents encouraged our return to present draft proposals and then to share designs in the final review. The final proposals were shared on the RISE website to seek further comments from residents and potentially inform future plans.

The project was supported by many other people and organizations. Out in the Rockaways we were introduced to Project Underway by the Living City Project and the revitalization of Edgemere by the ReAL Edgemere Community Land Trust. Sail Rockaway also walked us through Marina 59 and discussed the increasing number of people living on boats on Jamaica Bay. WXY Studio welcomed us to their offices to share the work that they had undertaken in the Rockaways with RISE while Sam Stein, author of Capital City: Gentrification and the Real Estate State, met us and explained some of the histories of planning and development that have impacted the peninsula. While our approach to the project was mainly from the ground up, we also met with a team from NYC DDC (New York City Department of Design and Construction) and were generously advised by NYCHA (New York City Housing Authority).

Through the semester we invited guests to join the seminar to further enrich our knowledge of the Rockaways as well as the issues that this part of New York City faced. Shannon Mattern joined first to discuss her writing

on care and maintenance; Helena Rivara shared the community engagement work of A Small Studio; Deborah Helaine Morris explained the challenges of relocation and the Resilient Edgemere Community Plan; Anthony Engi-Meacock answered questions about Assemble’s community conversations that informed Granby Four Streets; Sam Naylor presented The State of Housing Design by Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies; Jane Wolff emphasized the precision and care needed in the language of coasts; Kristin Baja reminded us of the importance of working equitably and the challenges of our remote positionality in the university; Rosetta Elkin highlighted the importance of “retreat” as an approach to coastal flooding; and Martí Franch Batllori used his Girona Shores project to explain the need to take time when being embedded in place.

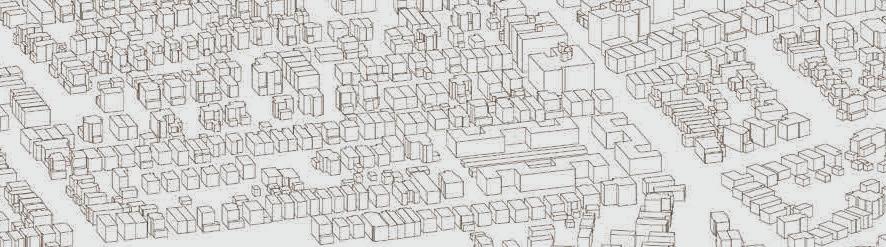

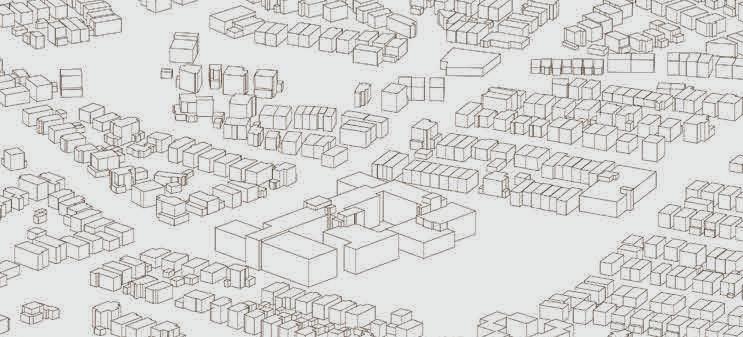

We adopted an iterative approach to the work. Weekly tasks in the brief built a structure where design proposals were informed by the research, fieldwork, and community workshops as well as the conversations with guests. Students employed digital drawing, mapping, and modelling, as well as composing written design codes, expanding from the scale of Jamica Bay’s beaches and Edgemere street sections to the massing of NYCHA housing and coastal bathymetry.

The project was not without its challenges. Firstly, we needed to navigate the uneven relationships between students based hundreds of miles away in Massachusetts and a community facing daily challenges of flooding and marginalization. RISE were extremely supportive in facilitating the project, but the need to take care in forging meaningful conversations while being open about what we could realistically achieve remained a concern. Secondly, we needed to make compromises between spending time in the Rockaways and following other commitments on campus. Community-based projects are complicated by the structures of semesters that don’t align well with the needs and rhythms of neighborhoods going through change.

Thirdly, the project held many complex questions, from everyday flooding to long-term rising sea levels, from gentrification to climate relocation, and from restricted public access to marginalization by public agencies. While the interdisciplinary nature of the seminar allowed

this complexity to be explored, there remained many challenges that we could not address. Fourthly, the work that the students produced also needed to communicate to different audiences: drawings had to explain the shared narratives of residents, all of different ages and backgrounds, as well as communicating to professionals and academics.

Finally, one of the questions that became louder through the semester was how we talk about climate relocation with communities whose everyday challenges can overshadow the need to plan for futures of longer-term rising sea levels. In the Rockaway’s Housing Superstorm project we asked more questions than we ever got near to answering, so it seems appropriate that we finished the project still grappling with such concerns.

Collective liberation: Transforming from within by recognizing our conditioning and working to transform systems and structures by transforming how we treat ourselves, each other, and nature. (Kirstin Baja)

Consideration: Recognizing that our perspectives and experiences are just one part of a larger picture, and thoughtfully creating space for the voices, needs, and experiences of others. (Larry Botchway)

Dynamic: Sea levels, society, and the hydrological cycle vary substantially over time. As we consider policies and desired futures with respect to flood risk management, engaging with uncertainty and impermanence can help identify tractable solutions. (Steve Koller)

Edge: A cultural and physical zone, often misunderstood as a hard line between ‘‘this’’ or ‘‘that’’, commonly articulated where water and land meet. Edges are thick and fluid spaces that are inhabited by people and materials in flux. Design that engages in edges should adapt to their transient nature. (Carlo Raimondo)

Flexibility: Land needs to be flexible to make space for water, boundaries ever-changing, non-existent. Buildings need to be flexible: moving, shrinking, weathering, adapting to change. Doesn’t designing for flexibility require flexibility in creative process? (Bhavya Jain)

Floating: A state of suspension, shifting with wind and tide, that offers residents a seamless and dynamic way of living in harmony with the ocean, simultaneously fostering connectivity to the natural wonders of Jamaica Bay, New York City, and beyond. (Randy Crandon)

Language: The medium through which neighbors, strangers, visitors, and long-time residents can communicate with each other about the coastline, and which can be used synchronously, asynchronously, or separated by long periods of time; and which can be visual, auditory, tactile, or otherwise. (Sam Naylor)

Listening: Taking time to pause, focus on someone or something else, and to reflect on what is heard is necessary for engaging in conversations about changing coastal landscapes and the challenges faced by people who are part of them. (Ed Wall)

Local stakeholder: The person or group that “holds” something “at stake” in an area or a theme. The stakeholder will have a point of view that is local, knowledgeable, experiential, and laced in options. The local stakeholder will be our most valuable asset in learning about a place or site and will help us understand its fragility, vulnerability, and opportunity. Finding the local stakeholder isn’t as easy as we think, but once we identify them, we have a clear brief and a collaborative road ahead. (Helena Rivera)

Persistence: Don’t be afraid to go against the stream! Keep working towards your goals for a sustainable, resilient, and equitable solutions. Continue to determinedly work with the community, even if you encounter opposition to new ideas. (Sofia Zuberbuhler-Yafar)

Reclaiming: Transforming underutilized coastal spaces into vibrant, community-driven environments. In the Rockaways, this involves repurposing neglected shorelines for recreation, connection, and resilience, fostering a sense of belonging and shared stewardship among residents. (Piper Claudia Williams)

Relocation: A crucial climate strategy for New York’s Rockaway Peninsula, where rising sea levels and intensified storms threaten communities. Relocation can provide the opportunity to reduce risk, protect lives, and restore natural buffers. This when done correctly, can ensure resilience while prioritizing equity, sustainability, and long-term adaptation to an increasingly volatile climate. (Makenzie Wenninghoff)

Restoring: Weaving fragmented scales of life and landscape—where housing adaptations meet expansive wetlands. This living mosaic blends resilience and renewal, as small interventions amplify larger ecological and urban transformations across vulnerable coastal environments. (Benedetta Zuccarelli)

Resiliency: The contradictory push to change just enough to remain the same. (Samuel Stein)

Retreat: Landscapes of retreat are portraits of climate adaptation, found in the land that is left behind as settlement patterns shift. Research suggests that communities are more likely to adapt to the forces of change when the landscape is appreciated. (Rosetta Elkin)

Risk: The ghost of a future uncertainty haunting the present day. When identified scientifically, a risk may be difficult for the average person to empirically perceive and thus difficult to mobilize around for mitigation. Climate change accelerates all risks, demanding new tools and paradigms for understanding the realm of possibilities. (Allen Wang)

Solidarity: In the face of rising sea levels, the communities in the Rockaways stand together bound by a shared shoreline and a shared fate. Storm surges and flooding: A community collectively fights for climate action to adapt it’s coastal heritage for future generations. (Rosalea Monacella)

Skeptical optimism: Striving and working to address key challenges-because of an optimistic belief that progress can be made—but also taking time to step back to seriously (and skeptically) identify and assess key assumptions. (AKA optimistic skepticism). (David Luberoff)

Thriving: Both as a process and an outcome. To thrive is to progress, to flourish, to advance. To center thriving is to require more of people, landscapes, structures, and the infrastructure that connects. Adaptation that permits people and place to blossom with cognizance of risk. (Deborah H. Morris)

Tools: Physical and cognitive devices for guiding or augmenting an individual or collective perception of the environment. Tools may aid in measurement, embodiment, and communication of shifting conditions on the coast, prompting imagination of what was, is, and can be. (Garrett Craig-Lucas)

Trust: Trust is necessary to create truly resilient neighborhoods. Trust emerges when there is a process by which all stakeholders can bring their skills, beliefs, goals, and abilities to the project, have a deep stake in its outcome, and that results in direct impact on physical environments and lived experiences. (Tanya Gallo and Andrew Meyers)

Unbuilding: The mindful deconstruction of the built environment—including residential structures, utility infrastructure, and roadways—to ensure that areas which face an outsized risk from coastal flooding can no longer be inhabited and are returned to a more natural state. (Chandler Caserta)

32 Mediating the Urban Edge

Chandler Caserta

36 GreenMosaic

Benedetta Zuccarelli

40 The East Bayside Commons

Piper Claudia Williams

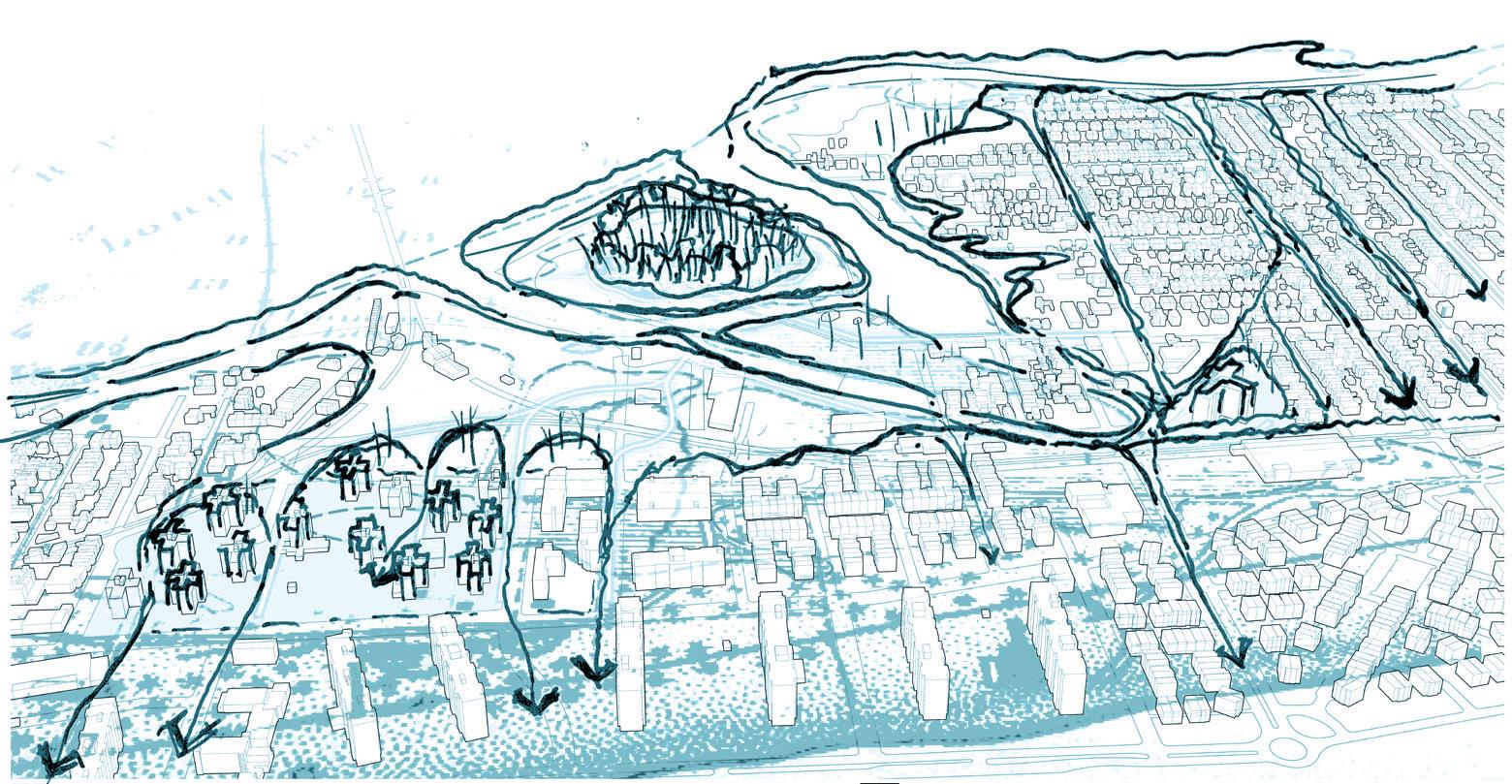

44 Growing on the Edge

Garrett Craig-Lucas

48 Blue Green Ways

Mabelle Zhang

52 Connecting Rockaway Re-Creeking with Infrastructure

Bhavya Jain

56 Living Shoreline on the Bay

Kirsten Sexton

60 Filling in the Edge(mere)

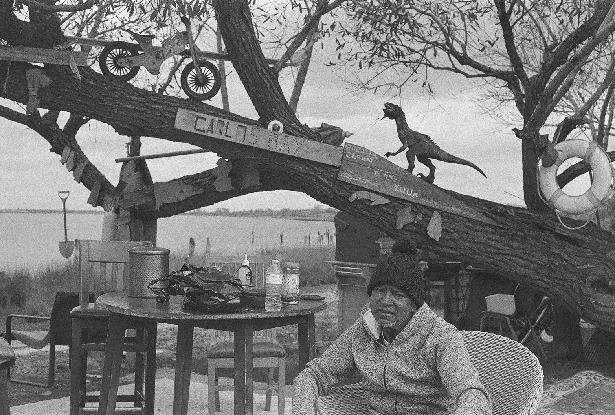

Carlo Raimondo

64 Grow, Learn, and Play by the Bay

Makenzie Wenninghoff

68 Can the rising tide lift all boats?

Allen Wang

72 Greening the Grey

August Sklar

76 Getting Afloat on the Bay

Randy Crandon

Chandler Caserta

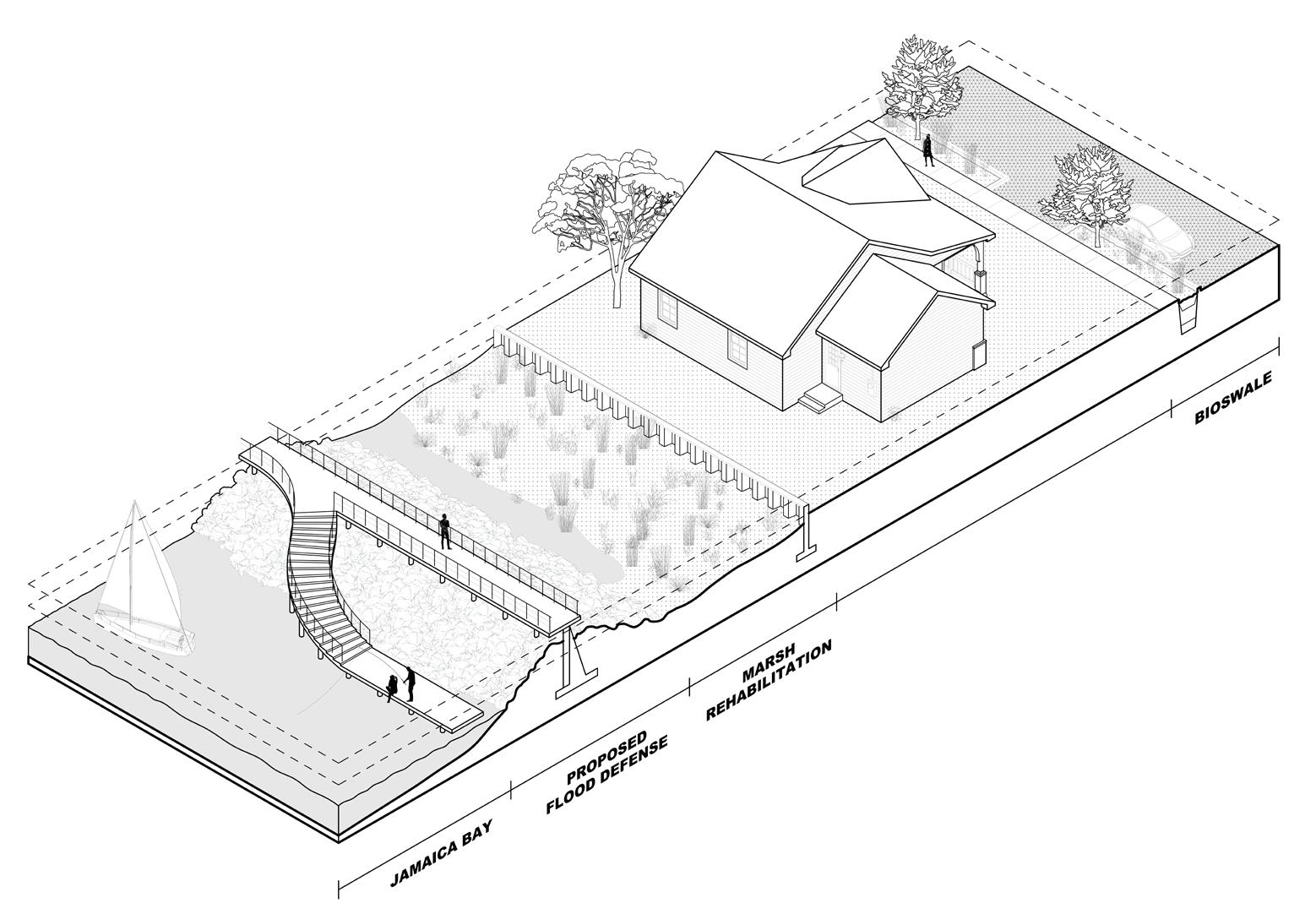

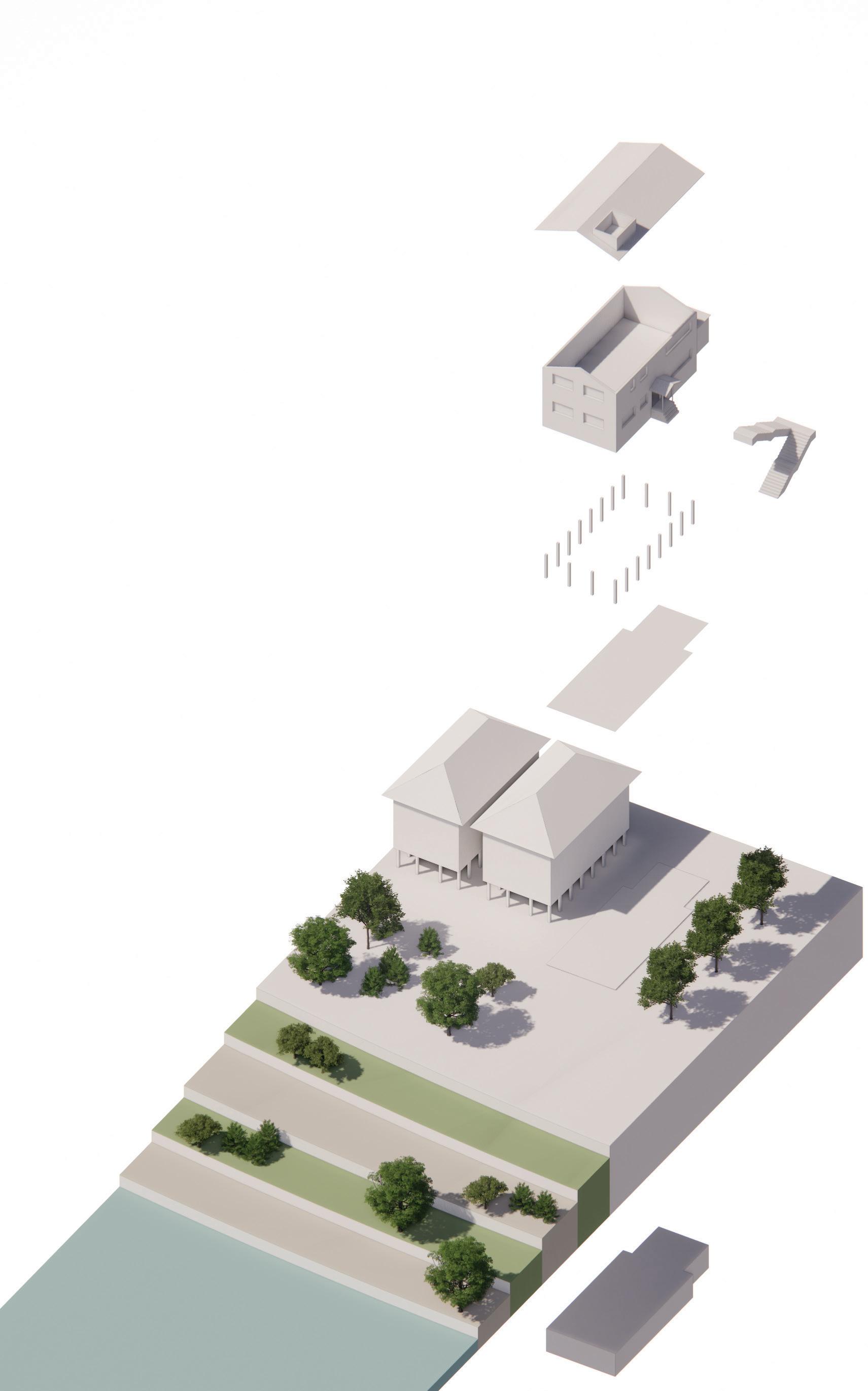

A system of raised pathways and boardwalks will connect existing green-spaces along the bay. Connection points will be placed at the end of each dead-end street to ensure that this new public space is accessible to everyone.

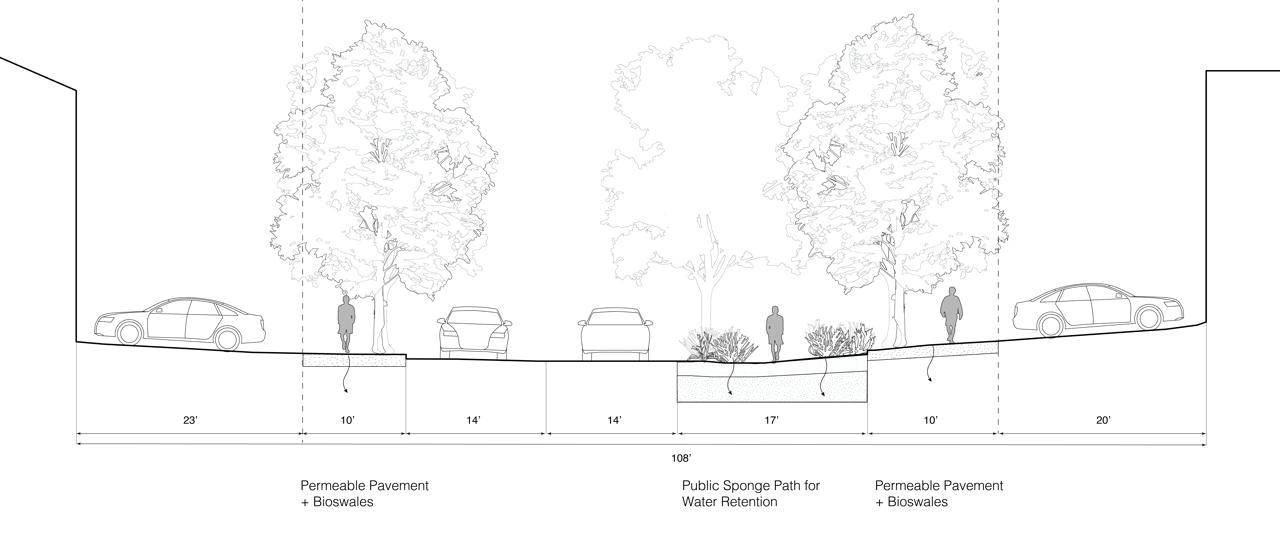

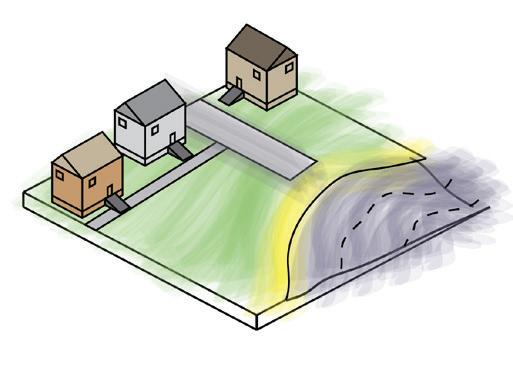

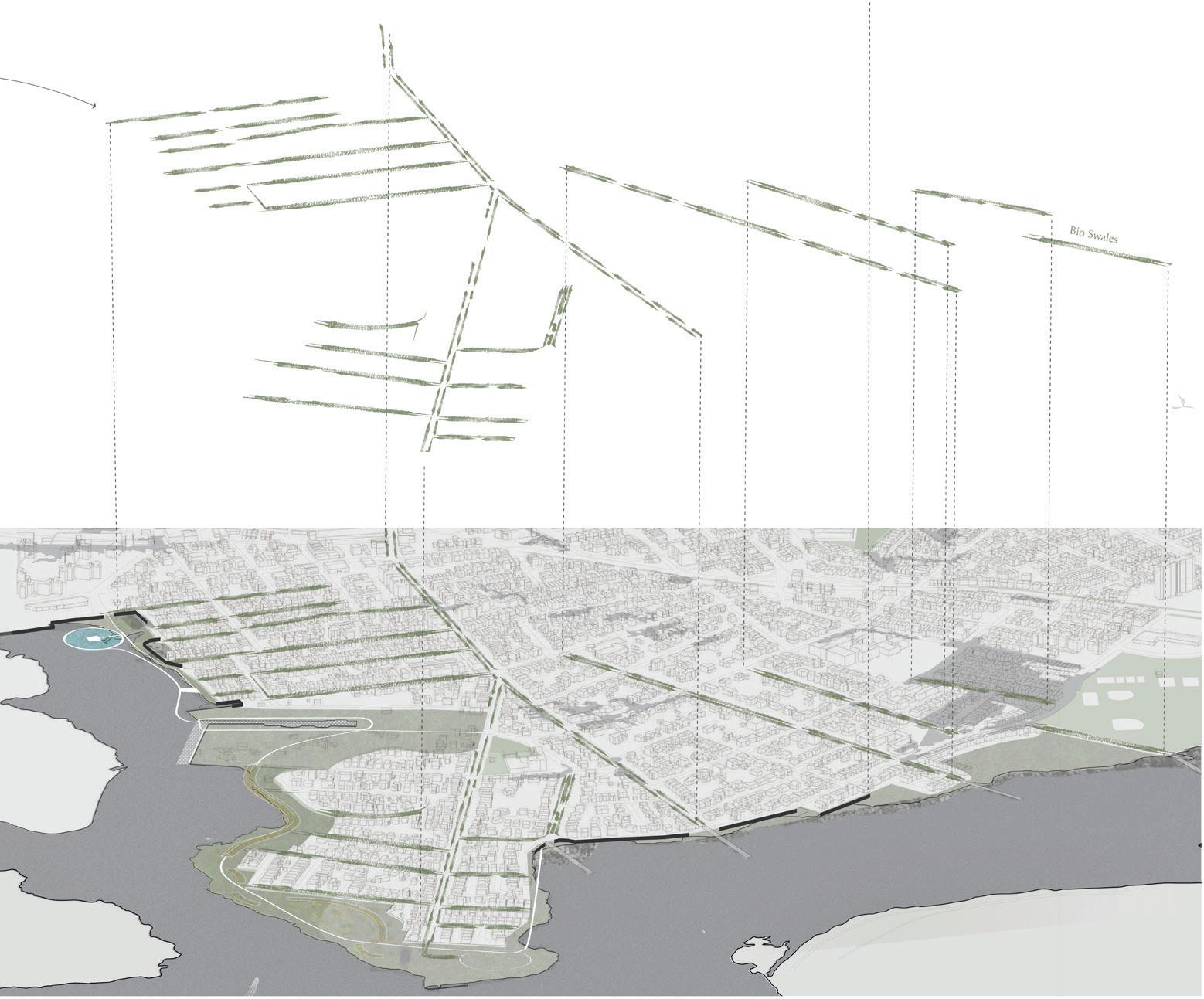

Built into these pathways will be a series of natural and manmade flood infrastructures to reduce the risk from inundation. In addition, bioswales and permeable pavement will be introduced along low-lying streets to encourage absorbency and reduce flooding.

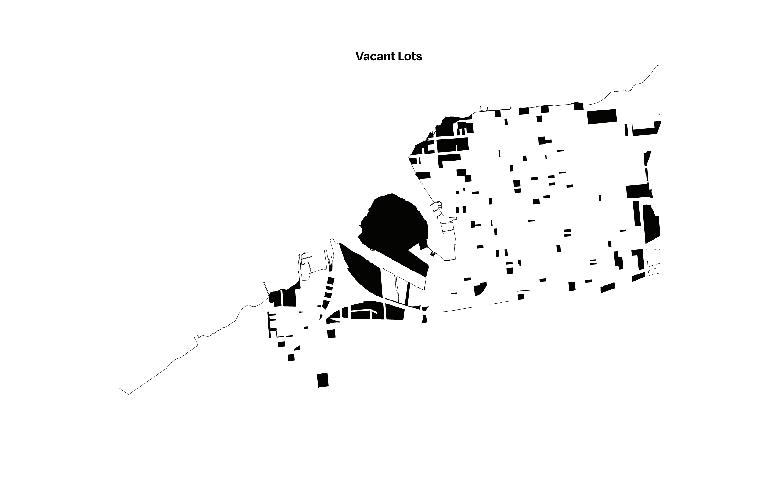

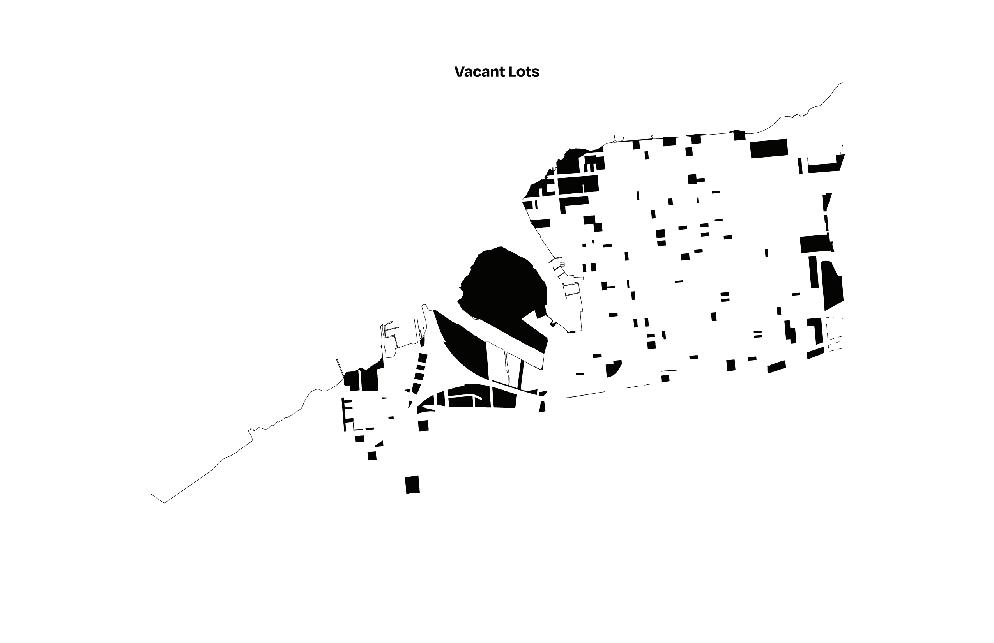

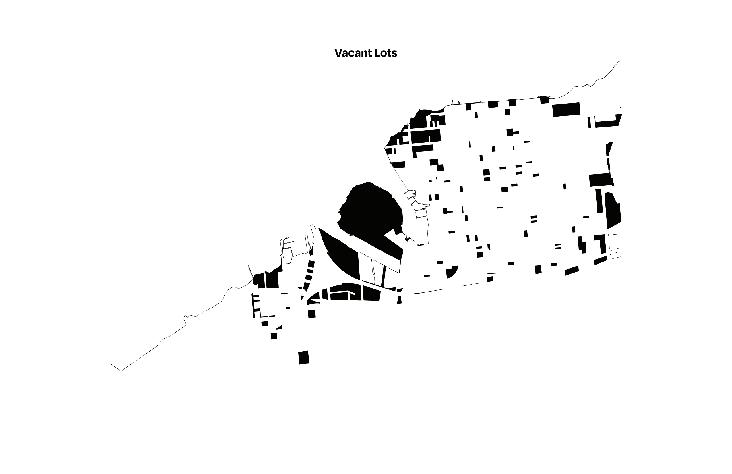

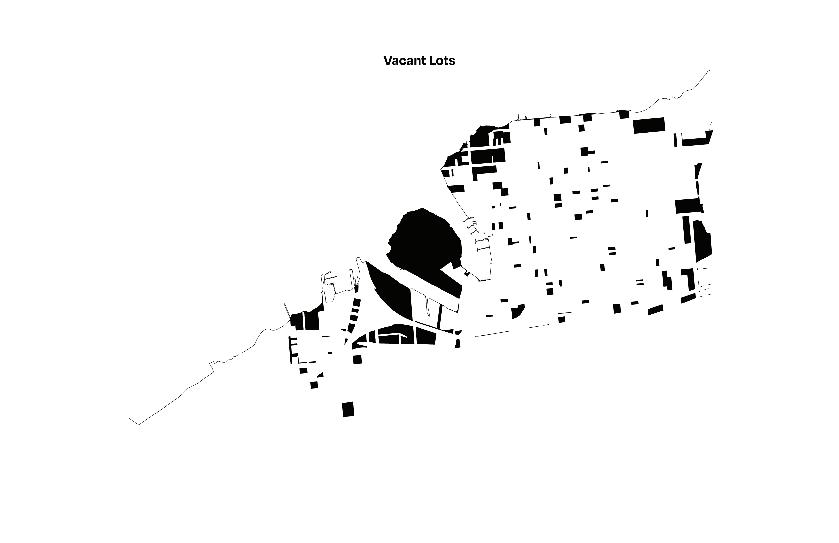

Rehabilitate vacant industrial sites to allow them to naturally recover and develop healthy ecosystems. Newly constructed paths will allow these ecosystems to be accessible to the public in addition to recreational green-space.

A ferry terminal will be introduced near Beach 69th Street to ensure the bay-side is accessible to the rest of NYC and viceversa. In addition, disused barges near the Arverne Cinema will be transformed into small vendor spaces to encourage local businesses.

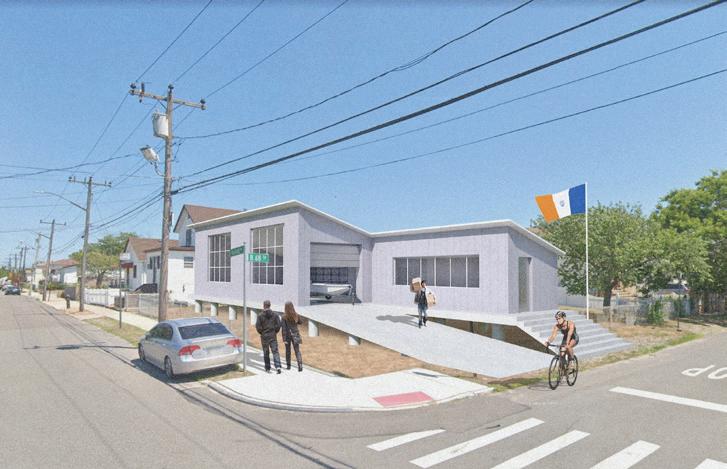

1.01 Beginning in 2030, no new residential, commercial, or industrial development shall be approved north of Beach Channel Drive given the certainty of future flooding risks.

1.03 Current and future vacant property will be transformed into a natural meadow, public greenspace, or a community garden depending on the desires of the surrounding neighbours. Adjacent vacant parcels can be combined with one another and should interconnect with interior pathways.

3.02 In the event that a property is damaged beyond repair during a storm event, residents will be offered a buyout that matches the value of their home in 2029, having adjusted for inflation.

3.03 A facility will be constructed on vacated industrial land to process the building materials from homes which have been vacated due to flooding. Materials will be salvaged or processed into a recyclable form.

4.01 Beginning in 2030, the Arverne Community Relocation Trust will be established and operated by the State of New York. Funded by Federal, State, and Local resources, the Trust will be established to ensure that residents of Arverne will always be able to receive fair compensation for their property in the event that they are no longer able to live in their home.

4.02 The trust will acquire property outside of floodplains in NYC in order to establish housing cooperatives. If a resident of Arverne wishes, they can trade their buyout for the ownership of a cooperative unit. This will ensure that residents are removed from the risks posed by home ownership in the age of climate change.

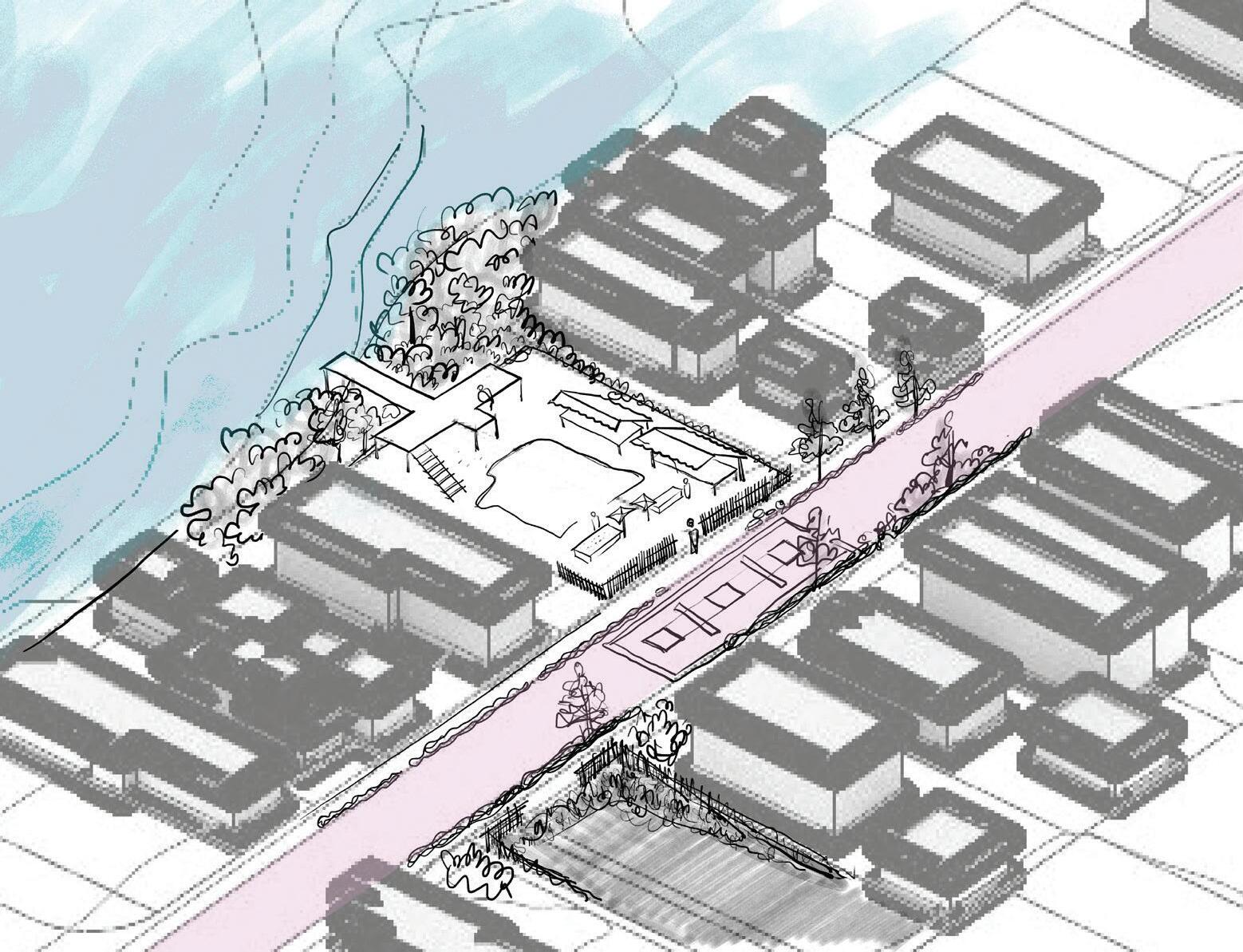

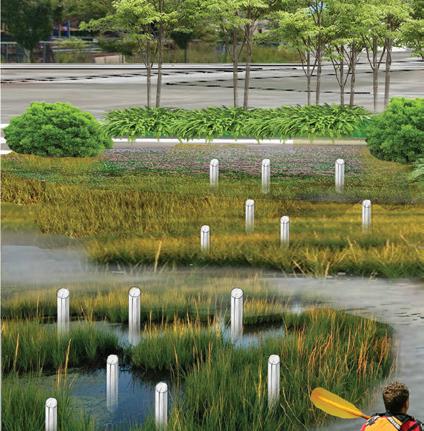

The GreenMosaic envisions a network of interconnected parks and green spaces that strengthen Far Rockaways’ coastal resilience while enhancing community life. This largescale mosaic serves as a natural buffer against flooding and erosion, and at a smaller scale, it integrates flood-adaptive housing features to create resilient, ecologically connected neighborhoods that foster a deeper community bond with the natural environment.

Connect pathways to water access points, enabling recreational activities like kayaking and tidal pool exploration, while creating a “bridge to the water.”

Provide flood and tide protection through terraced structures, enhancing resilience against rising water levels and coastal erosion.

Green spaces to reduce water runoff and offer recreational opportunities. Support environmental education and community activities.

GM - Garden Mosaic (Permeable soils and urban gardens)

GM 9.03 Green Boundaries Veil of Green for Privacy

Fences and edges should use vegetation as transitions, creating natural buffers that enhance community and environmental integration.

SP - Street Pattern (Permeable soils and bioswales)

SP 9.02 Community Spaces Corners of Companionship

Seating areas must be integrated with bioswales to create small communal spaces along streets, fostering neighborhood interaction and climate resilience.

NP - New Parks (Rain gardens and recreational spaces)

NP 9.02 From Yard to Park Yards of Adaptable Life

In residential areas, neighborhood yards should be combined to form new parks, providing muchneeded green space and ecological benefits.

AH - Adaptive Housing (Floodable basements and user needs)

AH 9.04 Adaptive reuse Adapting to the Water’s Flow

Coastal homes should be designed to transform into impact spaces for community hubs or seasonal rentals, integrated into parks with minimal infrastructure.

T - Terracing (Flood protection and wetland preservation)

T 9.03 Shoreline Facilities Sites of Discovery

Terracing should incorporate panoramic viewing areas, fishing docks, or boat launches to enhance community interaction with water and coastal resilience.

Piper Claudia Williams

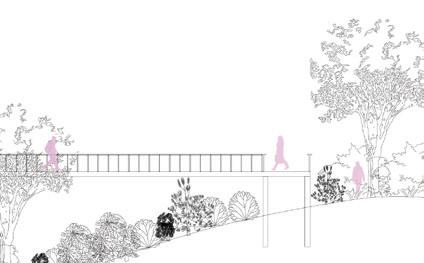

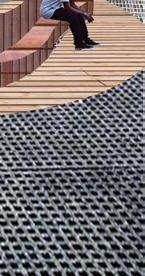

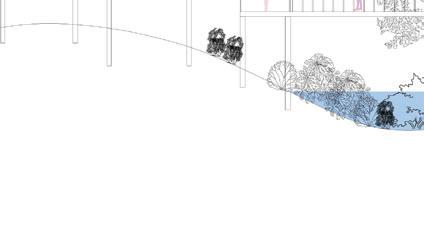

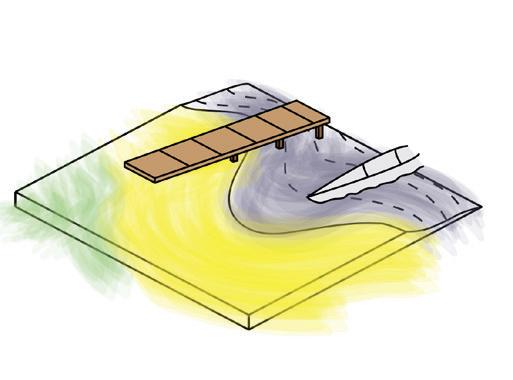

The East Bayside Commons proposes a resident-driven park network along the Far Rockaway waterfront, designed to connect naturally with local neighborhoods through accessible, intimate entrances. The park features thin, meandering boardwalks that encourage lingering, blending elevated views with direct water engagement to create a contemplative, bayside experience. Community amenities—including swimming docks, fishing sheds, public boat launches, and open air pavilions—invite residents to shape their interactions with the bay, fostering a flexible and inclusive space for everyday life. With native vegetation and designated low-intervention zones, the park promotes ecological health and resilience, establishing a sustainable community framework rooted in connection to the waterfront.

Collective

Access

Heights

C-3.1 Modular spaces shall be designed to adapt easily to diverse community uses, allowing residents to shape each space as needed.

A-1.1 Residential cul-de-sacs and dead ends shall be designated as intimate park entrances, inviting nearby residents into the bayside paths.

H-2.5 Transitions between heights shall be smooth, ADA-compliant, and intuitively designed to maintain an accessible flow throughout the park.

N-4.1 Native vegetation shall be planted throughout key zones of the park to promote biodiversity, low maintenance, and local ecological support.

N-4.3 Permeable materials shall be used in pathways to facilitate natural water drainage, contributing to the site’s ecological resilience.

E-5.2 Lightweight structures shall be utilized to create shelter while preserving sightlines and maintaining an open feel.

E-5.5 Semi-enclosed spaces shall frame water views thoughtfully, focusing the design on the bay to create a cohesive sense of place.

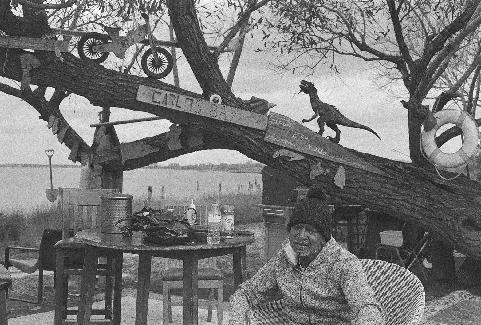

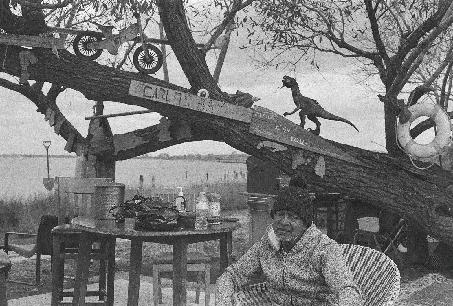

Garrett Craig-Lucas

Growing Edge + Community of Land + Connections + Water + Partnerships Past + Friendships Future + The Futures City

A framework for a network of public spaces organized around planting and stewardship on the bayside of the Rockaways, outlining actions to enable growth of, and by, animators, the people shaping the landscape.

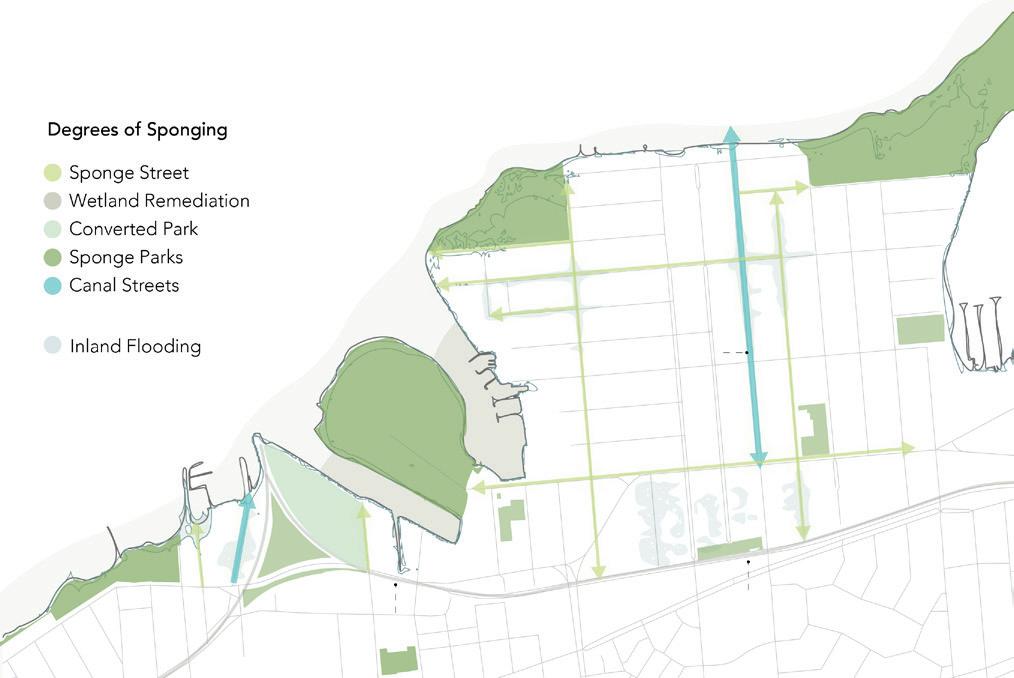

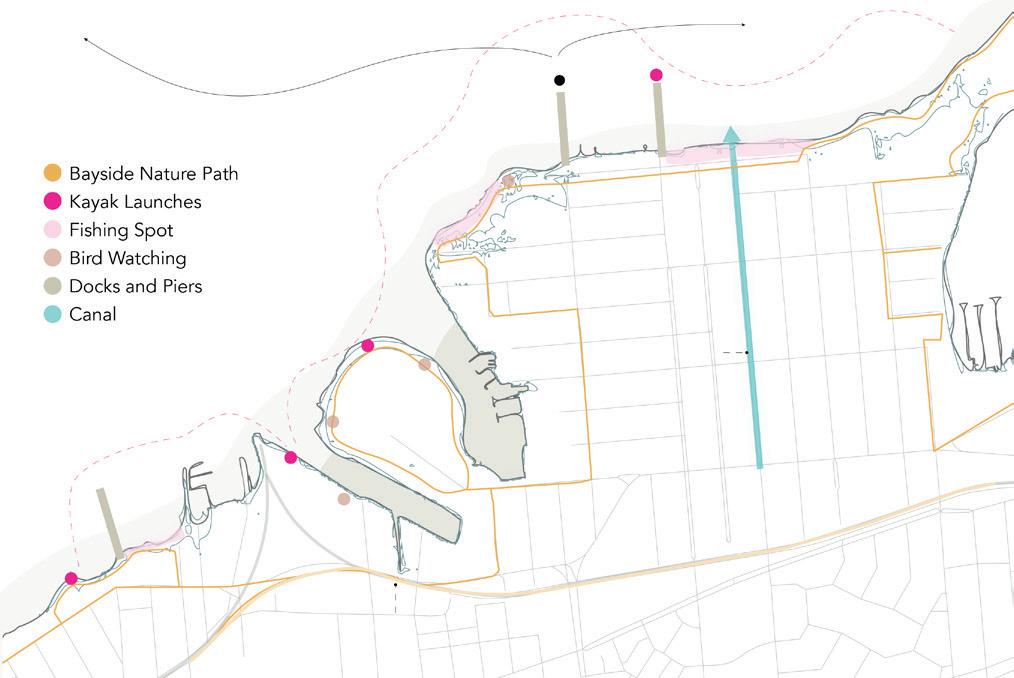

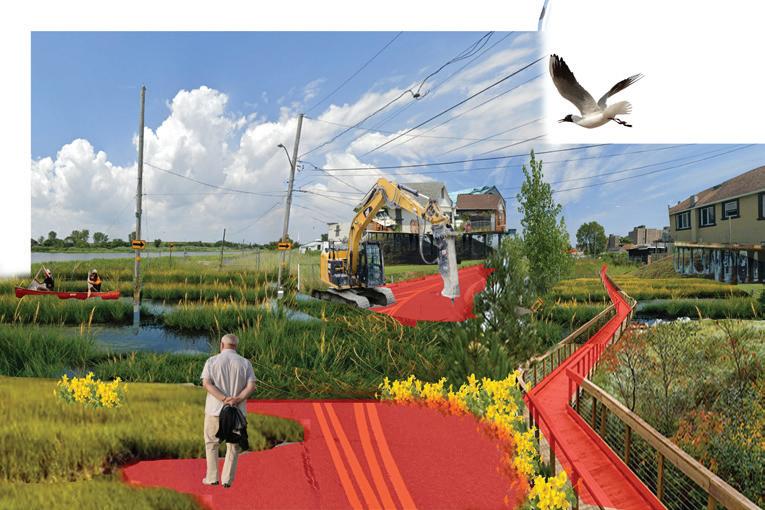

Mabelle Zhang

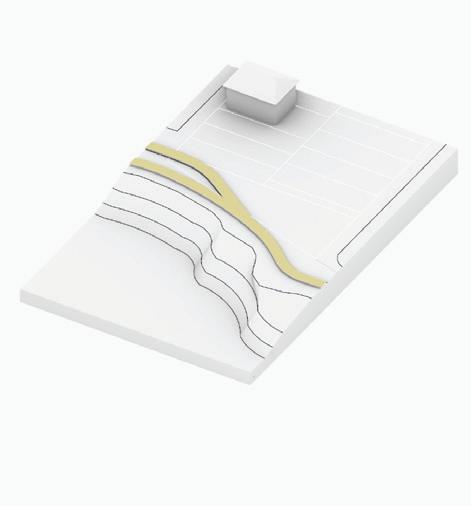

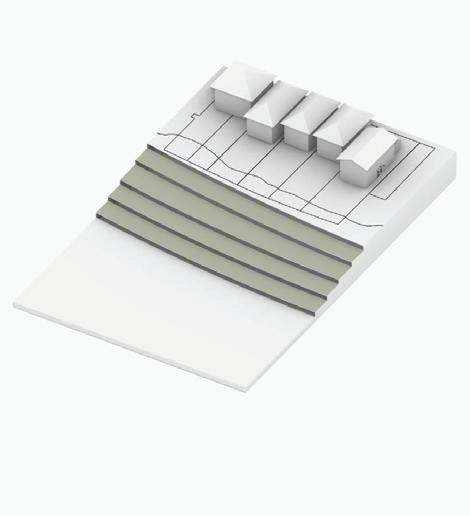

This project seeks to transform the bayside into a resilient, recreation-oriented waterfront that leverages green solutions and celebrates nature-based and water-based activites. Key design principles are:

To make this area into a natural sponge. This is achieved by expanding green space into underutilized lots, creating a network of “sponge streets”, that retain and filter water, creating canals in especially water-risk areas, and targeted wetland remediation to cleanse stormwater runoff before it reaches the bay.

To make this area into a immersive nature recreation experience. The Bayside Nature Trail provides continuous access to the bay with various recreation stops along the way. These include kayak launches, bird watching, fishing spots, a network of pieces and docks, and a ferry stop for increased access to this recreation hub.

Relocate: Community Driven

3. Reuse dismantled housing materials to construct bridges, pedestrian pathways, and boardwalks to improve connectivity and public access to open spaces.

5. Community members lead decisions on relocation strategies and site selection for new homes.

6. Phased relocation should prioritize those whose homes are regularly inundated with water.

7. Existing housing outside of the 2100 high tide line should be elevated to 15 feet above ground.

1. Vacant lots must be restored to public wetlands, prioritizing native plant and habitat restoration.

3. Design wetlands to serve as a natural buffer along the shoreline, mitigating flood risks and supporting biodiversity.

4. Reduce contamination in Jamaica Bay by expanding wetlands and remediating the shoreline.

5. Install bioswales along streets with irregular water inundation to capture and filter stormwater.

6. Require residential lots to include a minimum percentage of green space for water absorption and ecological benefits.

Revitalize: A Green Economy Hub

2. New development is limited to green economy businesses, community uses, or educational uses.

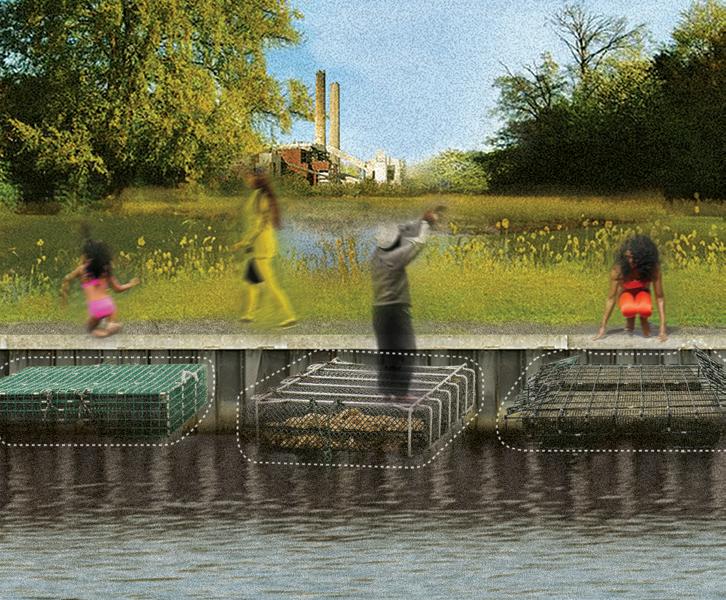

4. The historic oyster farming industry will be restored, once Jamaica Bay’s health is restored; new green water-based industries like kelp farming will be prioritized.

5. Recreation activities should celebrate the Rockaways’ natural assets, including kayaking, birdwatching, fishing, and outdoor exploration.

6. As the shoreline moves higher, a shoreline will be established with public access trails using repurposed materials.

Bhavya Jain

The project aims to provide protection against the rising possibilities of floods, storm, and tidal surge while providing the necessary recreation and amenities for the residents of the Rockaways. Eco-buffers are proposed along the edges towards the bay with boardwalks at places that double up as community spaces and kayak stations in a few spots. A corridor is proposed throughout the site which revitalises the access to various amenities such as community gardens, sports utilities, as well as parks and waterfront areas. Half of the landfill area is proposed to be empty for building infrastructure that might be needed for a future when there is sea-level rise. The other half is proposed to be an open area which can be used by the residents. Largely the material strategy for building is as follows:

• Layer of infrastructure to protect the coastline

• Decaying infrastructures and constant renewal

• Reclaiming infrastructure ecologically

• Protecting ecology from decay

Access to Shelter (Emergency Response)

1. All existing public buildings such as community centers and libraries should be retrofitted to incorporate high safety standards and secure storage for supplies.

2. Elevated areas must be identified, and critical emergency shelter facilities must be provided in buildings in these areas.

Gradual Retreat and Safety

1. The entire Rockaway Peninsula is to be declared as an eco-buffer zone with special tax credit and incentives for re-wilding efforts.

2. Incentive for transforming (high) buildings that cannot be easily removed or inhabit a temporary floating platform or eco-habitats.

Infrastructure Adaptation

1. Each neighborhood level block will have a wet street. These can become canals or artificial lakes during high tide or heavy rainfall.

2. Railway networks and freeways should either be elevated above the 500-year flood mark or allow for amphibious navigation.

Autonomy of Food and Power

1. All high-rise buildings should have their own wind-proof and flood-proof urban agriculture facilities (e.g., roof gardens, hydroponic systems).

Living with the Ocean, Health of the Ocean

1. All large open and public spaces not in use should have swales, retention basins, and other low-tech water management features to prevent runoff infiltration.

Kirsten Sexton

Living Shoreline on the Bay is a proposal to revitalize the existing waterfront in Rockaway Beach from Beach 90 St to Beach 65 St. It will do so in two phases:

1. Allow the bay to retake land under the current high tide zone, creating a porous and natural shoreline that aims to create and foster the existence of salt marshes, protected wetlands, and parks/open spaces for residents to enjoy.

2. Activate existing city-owned vacant lots with the injection of pop-up parks that encompass three different tyopologies of activity. These will be a market (economy), a community theater (arts), and an urban farm (food).

Salt marshes work to absorb excess water from flooding and storm surge, protecting the shoreline against erosion and fostering habitats for diverse wildlife species and filtering pollutants from the bay. This proposal will use natural remedies to address the polluted water, such as oyster farms and blue mussel beds, which offer an opportunity for the community to engage with waterfront educational activites while benefitting from the natural filtering that the species offer. This proposal will also inject community amenities, such as a boat launch, an ADA kayak launch, an outdoor ampitheater, a fishing pier, a public pool, and sports courts, among other leisure activites.

I. All privately-owned vacant lots shall be converted into public space or commercial amenities.

II. All land within the current high tide zone should be given back to the bay.

III. All build-it-back lots shall be converted to open, public, community space.

IV. All existing green spaces shall be made resilient and improved.

V. Every building located in the predicted 6 ft sea level rise zone shall be elevated by 10 ft.

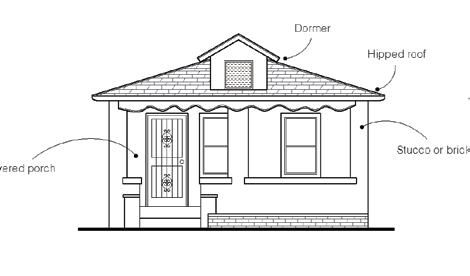

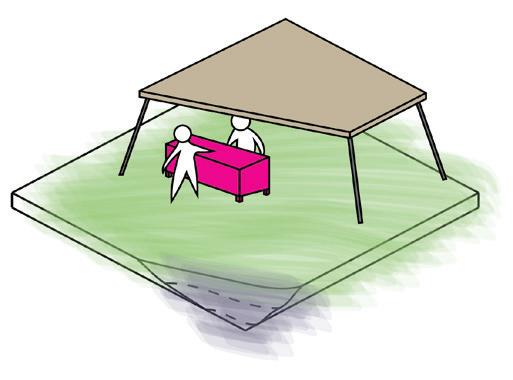

The spatial strategy of Amphibious Arverne chooses to embrace the precarity of the projected conditions of the Rockaway Peninsula when faced with the threat of climate disaster. Within the next 75 years, it is highly likely that nearly all buildings in the Arverne neighborhood will face inundation from storm surge and more frequent high-tide flooding. At the very worst, these buildings will become completely underwater. Embracing this fate, Amphibious Arverne aims to equip residents with a toolkit for retrofitting their exisiting homes to be better equipped in the event of flooding. Additionally, this strategy interjects three community programs onto city-owned vacant lots that incubate existing community use patterns and offer a third space for residents, such as a community theater, urban farm, and a fishing pier. These programs fill in neighborhood needs and address issues in the present.

Project. Began in the 2000s in response to relief efforts post Hurricane Katrina, the Buoyant Foundation offered a solution to retrofitting existing houses to become more resilient of tearing down and rebuilding. This

technology may be applied to the Rockaway Peninsula. Existing foundations are excavated replaced with buoyant blocks attached

retrofitting their exisiting homes to be better equipped in the event of flooding. Additionally, this strategy interjects three community programs onto city-owned vacant lots that incubate existing community use patterns and offer a third space for residents, such as a community theater, urban farm, and a fishing pier.

frame. This allows the house to rise up to 10 the event of extreme flooding. Vertical guidance posts allow the houses to stay in place. This strategy operates in opposition to the act statically raising houses, which is anthithetical longevity as projected flood plains continue Instead, this system offers a solution that flexible, affordable, and relatively easy to install. Most of all, it preserves the character of the existing Rockaway Bungalows, which have, the 1930s, embued the neighborhood with of community, spirit, and whimsy.

Katrina, the Buoyant Foundation offered a solution to retrofitting existing houses to become more resilient instead of tearing down and rebuilding. This same technology may be applied to the Rockaway Peninsula. Existing foundations are excavated and replaced with buoyant blocks attached to a steel frame. This allows the house to rise

and relatively easy to install. Most of all, it preserves the character of the existing Rockaway Bungalows, which have, since the 1930s, embued the neighborhood with a since of community, spirit, and whimsy.

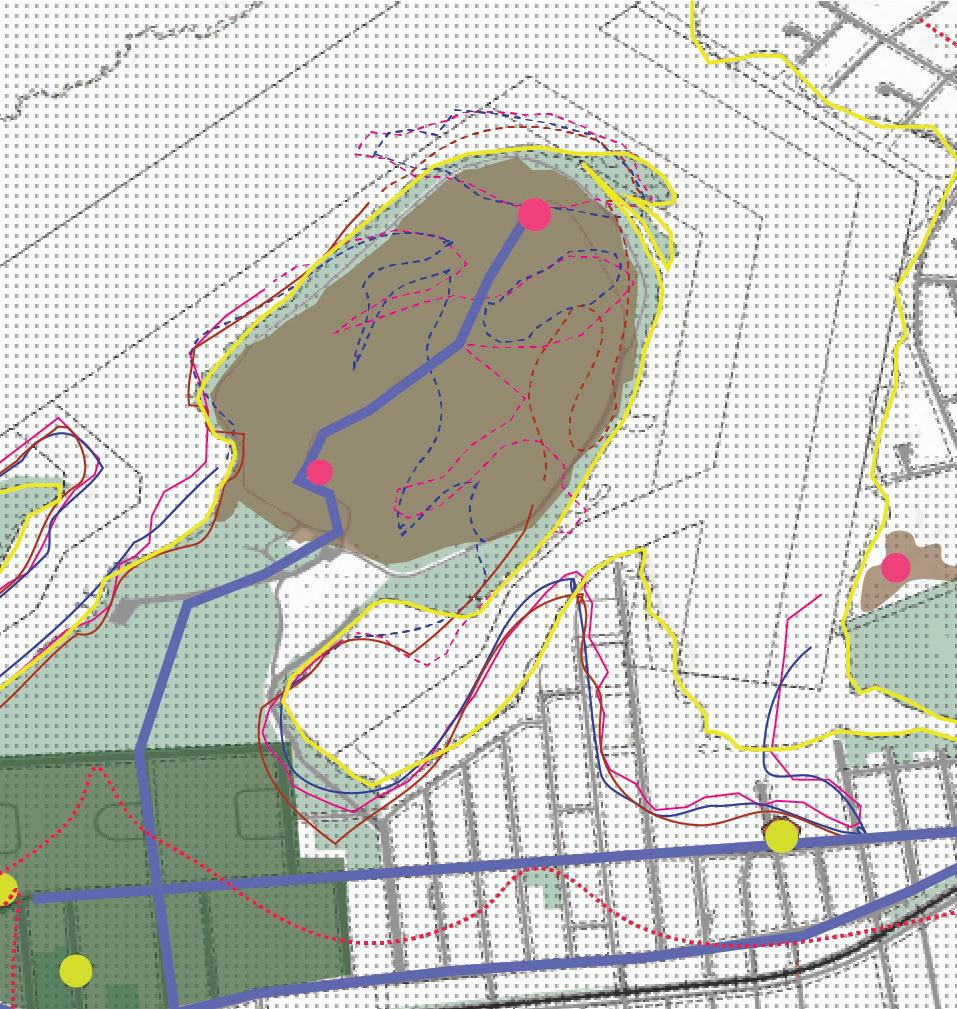

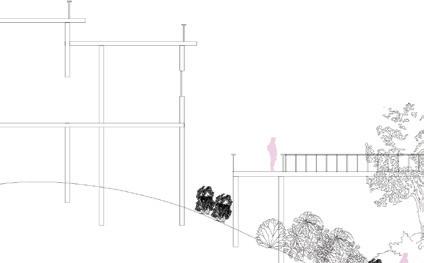

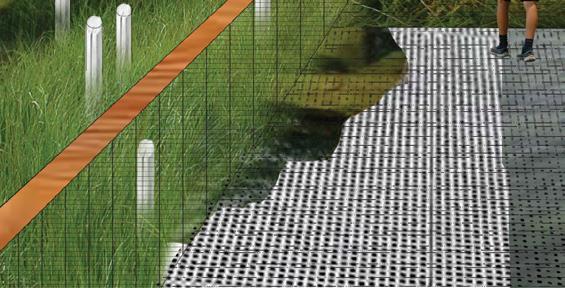

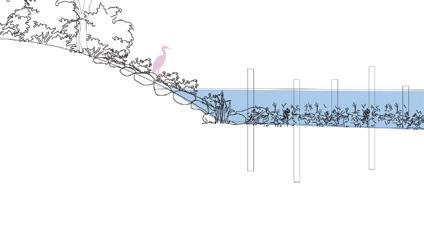

Carlo Raimondo

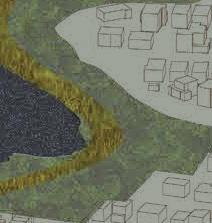

This project envisions the gradual integration of a wetland system into the Edgemere neighborhood, enhancing access to water in social, ecological, and infrastructural dimensions. Starting at the water’s edge along Jamaica Bay, the design establishes a network of raised walkways that consolidate and re-establish salt marsh habitats. This is complemented by a system of vegetated berms and swales that create a resilient edge, mitigating flooding and storm surge while providing public access to the bay. By reinforcing the boundary between the wetland and the neighborhood both ecologically and socially, the project fosters a new, dynamic relationship between the community and the water. The wetland’s gradual integration into the urban fabric allows for a transformation where open space becomes a collectively owned resource, and the line between private and public is blurred. Instead of retreating as the bay encroaches, this project aims to establish a future where Edgemere and Jamaica Bay coexist as one, redefining life within a living, adaptive wetland ecosystem.

6. Access will be defined and determined through a gradient of physical, social, and ecological cohesion.

7. The infrastructural needs of the water are situated in response to environmental pressures of flooding, rising sea level, and storms. Design interventions must operate symbiotically with evolving ecological conditions.

14. Through the invitation of the marsh into the neighborhood, new forms of intimacy with the wetland should emerge, fostering an intermingled way of life.

9. Salt marsh restoration must be implemented in any viable locations along the bay’s edge to create a resilient buffer for flooding and storms, improve water quality, and provide habitat for key species.

10. As water levels rise, the migration of the salt marsh should be facilitated into the neighborhood via vegetated swales, integrating the edge zone into urban spaces.

12. All houses should be elevated at least 10 feet and be situated on vegetated berms/mounds.

Infrastructural Adaptation & Wetland Integration

11. Existing infrastructure within this edge zone should be removed or adapted to be subsumed within the marsh. Removed materials should be repurposed to create mounded berms for elevated housing.

3. Any design intervention should be geared towards “filling in the edge,” realizing and strengthening the inherent potential of the transition zone.

18. Side streets in the neighborhood should be reoriented to vegetated swales, while roads connecting to the bay’s edge remain operational.

Makenzie Wenninghoff

Local community partners like Garden by the Bay, will be accessible from the boardwalk. Here, residents can learn to plant, grow, and harvest healthy vegetables and diverse produce. In addition, wellness programming will help to provide space to decompress and make space for mental and physical health.

Access to green-space will be available throughout the boardwalk. Nature trails that allow residents to get up close and interact with local land and water ecosystems will be emphasized. Non-profit groups lead nature tours and volunteer clean up events. Stewardship and planting opportunities will all be available to provide ample opportunity to learn about the lands, plants and animals found in and around Rockaway.

Community sports programs, renewed sports courts, kayaking events, and paddle boats will be just a few of the free or low- cost opportunities to play by the bay. Providing access to existing green space through improved lighting, mosquito control, and maintenance can help to ensure residents of all ages can enjoy the spaces near where they live at all times.

Immediate Retreat (2025-2050)

• A new shoreline will be established along the current high-tide line.

• Properties within the high-tide line will be purchased by the municipality at market rate by 2050.

• Displaced households will be offered fixed-rental housing for 50-years on the peninsula outside of the 5ft sea level rise zone.

• Newly held public properties will be conserved for water and coastal management and will remain open to the public without barriers.

• Households retreating will have unfettered access to their past properties for recreation following demolition.

Planned Relocation (2050-2075)

• Homes in the 2-3ft sea level rise zone will be relocated by 2075.

• As available, households may enter a lottery into fixed-rental housing for 25-years.

• The municipality will identify other viable housing options off the peninsula for all non-lottery winning households.

• Greening and preservation of properties from the first phase (retreat) will be complete and available for use.

Migration & Stewardship (2075-2100)

• Homes within the 4-5ft sea level rise zone will be part of the final migration from the greater Edgemere area.

• Households may elect to have municipal support in identifying housing or may be part of a larger migration away from New York City.

• In an effort to return the area to natural processes, efforts to prevent natural migration of the shoreline will not be permitted in areas of retreat, relocation, or migration.

Allen Wang

This public space proposal aspires to foster stronger connections between Rockaway residents and the Jamaica Bay shoreline in order to render the effects of climate change (particularly rising sea levels) more visible. Over time, as residents bond with a shoreline that gradually recedes inland, will their lived experiences inspire them to take greater action against climate change? This is the concept of the Climate Change Museum.

More concretely, I propose three sets of interventions (mobility infrastructure, shoreline recreation, and conservation zones) applied across four distinct zones (labelled A/B/C/D) supporting a plethora of activities along the shoreline, taking into account factors like proximity to residents, noise levels, and amenities. The proposal eschews new permanent construction, instead preferring to reuse what exists or to install temporary structures only, so as to empower the local community to act quickly (with minimal bureaucracy from distant city planners) while redirecting their limited funds to other needs (that are more urgent or will endure for longer in the face of rising sea levels).

1. The Rockaway Peninsula shall be renamed the Rockaway Archipelago, effective immediately.

5. New York City shall provide, free of charge, a bathymetric map of the Archipelago (with Islands, Shallows, and Deeps marked) available to all residents and visitors upon request.

2. A new Island is born when rising water submerges an existing Island into multiple contiguous landmasses.

5. Every Inhabited Island shall have, at minimum, the following amenities: a convenience store for essential supplies like food and water; a microgrid for electrical self-sufficiency (e.g., solar panels); a boat launch or pier for connectivity.

3. All Shallows are publicly managed by New York City for the good of residents. Private land that becomes a Shallow shall revert to NYC ownership, with the city paying fair market value for it.

4. The MTA and US Coast Guard shall operate a water taxi service to connect all Islands. This shall double as a water rescue service.

6. For water safety, lifeguards shall provide coverage of all swimmable shorelines, and lighthouses shall provide coverage of the entire navigable waters of the Archipelago.

1. There shall be a moratorium on all new construction on land that will become Shallows within the next twenty-five years or the expected lifetime of the building.

4. All buildings shall have a roof, second-floor door, or balcony that can double as a boat landing. Buildings with a sufficiently large rooftop shall also be accessible by helicopter.

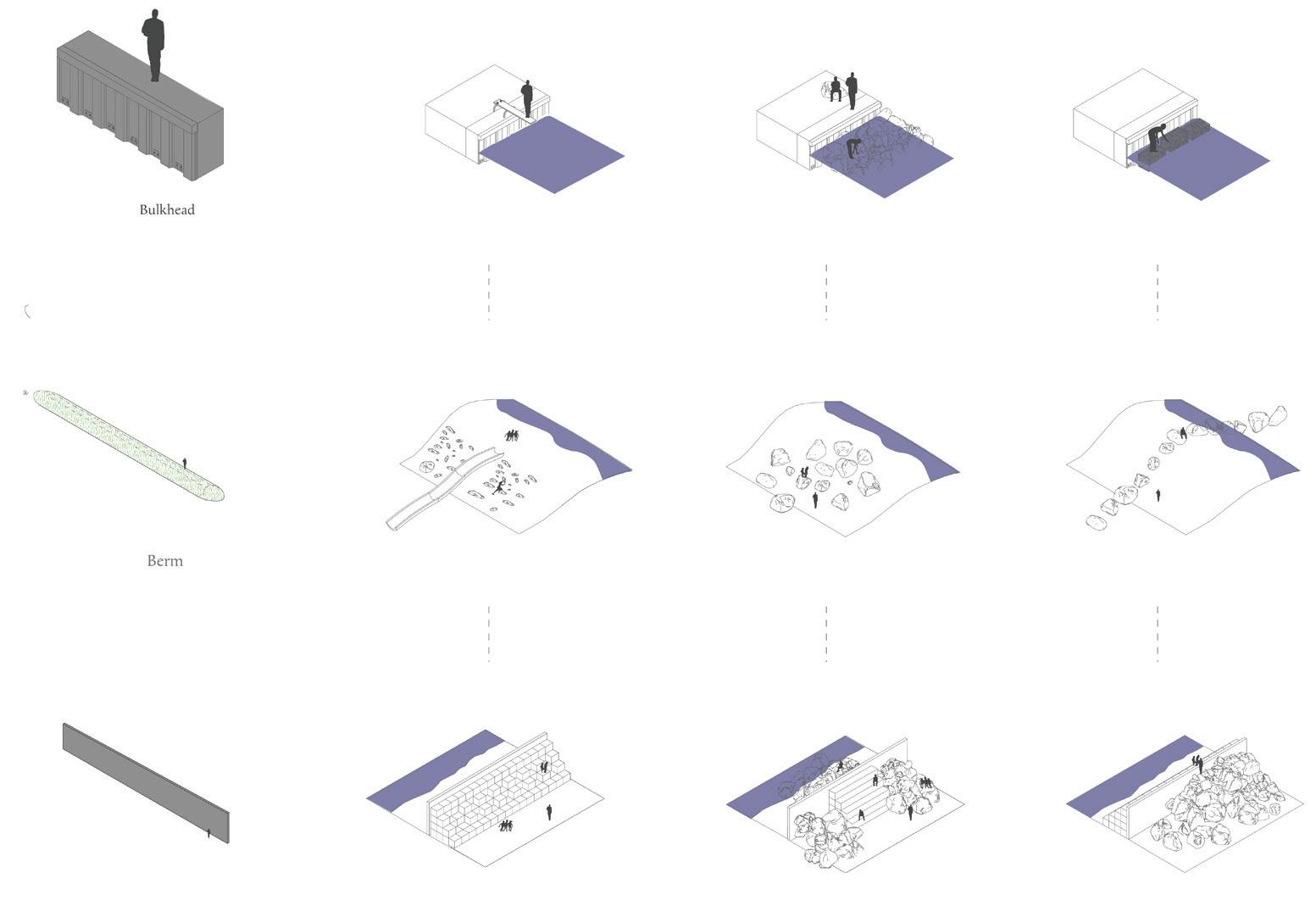

Greening the Grey addresses alternative solutions to impending flood protection infrastructure that will be implemented by the Army Corps of Engineers throughout the Rockaways. This project questions the implementation of grey infrastructure and aims to create a more porous, green future, where coastal resilience relies on the deconstruction and reorientation of existing infrastructures to form new ways of ecological and cultural engagement.

This project will erect several seawalls, a contiguous planted berm, and several bulkheads along the edge of Mott Basin. Greening the Grey intends to introduce green infrastructural solutions for storm attenuation and stormwater retention around the planned grey infrastructure. How can these interventions start bridging the gap between wet and dry, human and nonhuman, to create spaces for recreation and ecological connection?

Green infrastructure includes nature-based solutions that support the functions of a place. For the project, the implementation of berms and breakwaters is used as a means of storm attenuation that additionally contributes to habitat creation.

Grey infrastructure consists of conventional built structures made of non-living material. Below are suggested interventions to better engage with the Army Corps of Engineers’ schemes, creating a more socially and ecologically engaged riparian edge—a space where walls become breakwaters, and berms become playgrounds.

1. Deconstruct Existing Hardscapes

2. Reconfigure Flood Protection

3. Create Programs that Serve the Community

• This phase bursts the lining of concrete streets to create bio-swales in areas that are prone to stormwater flooding. The result is a more porous streetscape, with rubble from the deconstruction of streets used in gabions at the edge of the bay.

• Stormwater will initially be addressed through breaking up of excess concrete. Excess concrete will be used in tree pits and for gabion seating along Jamaica Bay.

• The second phase is focused on the reorientation of the Army Corps sea wall and bulkhead. Portions of the sea wall are removed in order to create access to the bay. The rubble from the removed walls is then used as breakwaters and barriers that adorn the sea walls and strengthen a connection to the bay, rather than as a separation.

• The third phase addresses the cultural significance of the proposed intervention. Through the creation of a contiguous park that connects the Army Corp Infrastructure, it becomes entangled in a more porous system. This system prioritizes that infrastructure cannot serve a single, logistical purpose, but must be multifaceted and serve as ecological hubs for the community.

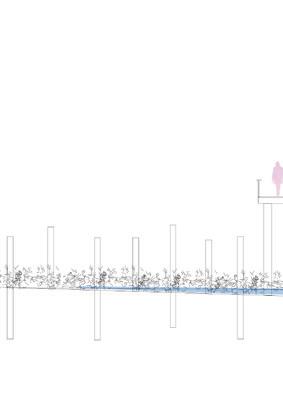

Randy Crandon

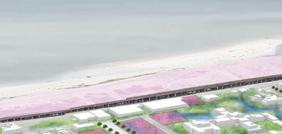

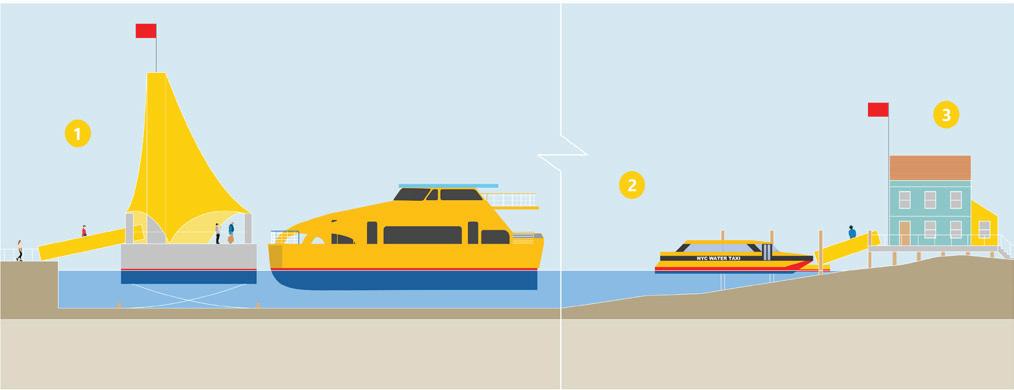

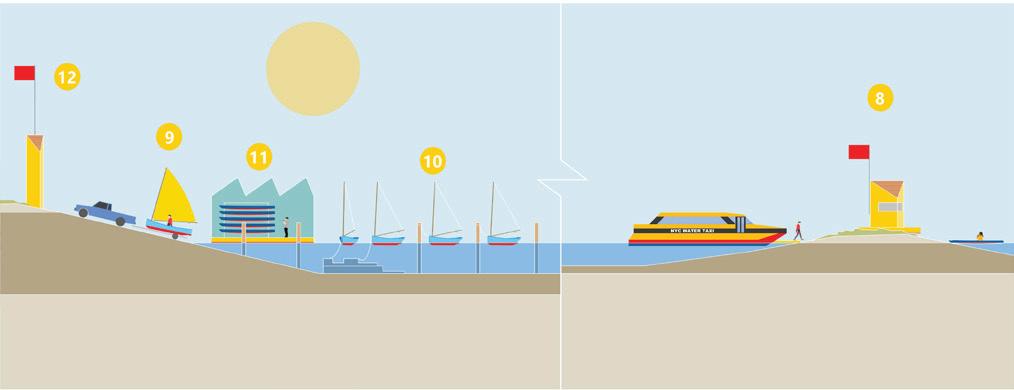

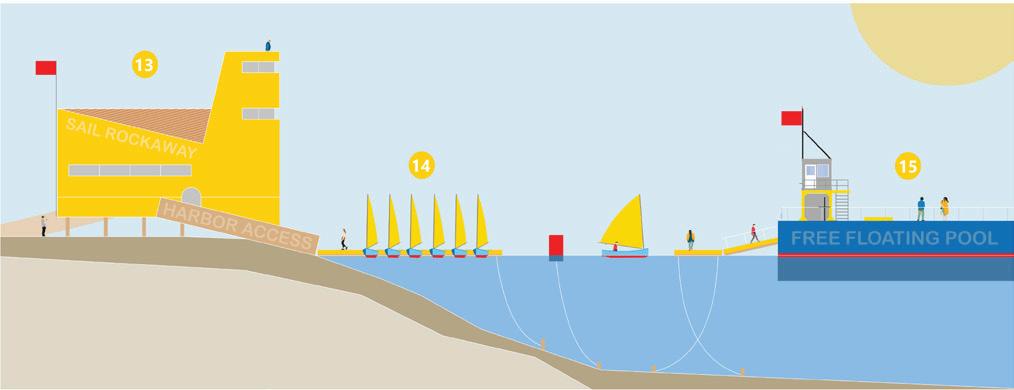

The proposal offers an alternative way of living with the rising seas. Naturally protected basins and underutilized points of entry along the shoreline are identified as ideal locations for new floating infrastructure. Water transportation, by way of expanded NYC Ferry service and water taxi services, is at the heart of the proposal and offers a seamless transition from land to sea. New floating spaces become the stage for everyday activities, while also encouraging a meaningful engagement with the ecological wonders of Jamaica Bay.

Transportation on the Water

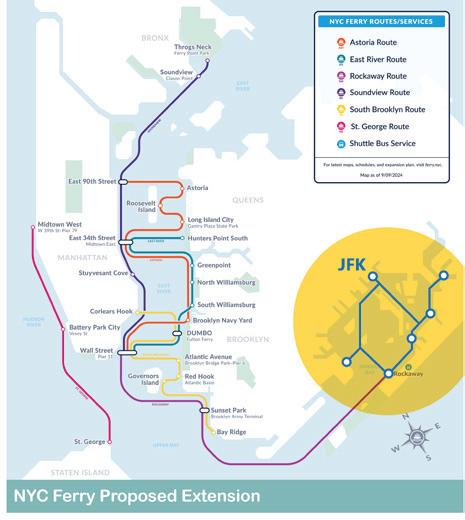

1. NYC Ferry Service will extend east into the bay and be free for all Rockaway residents, including a stop at JFK airport.

2. A new, shallow draft on-call Water Taxi service will provide 20x round-trip vouchers per year for residents needing short trips within the bay.

Homes, Buildings, & Streets with Water

5. Residents and building owners in flood-prone areas that lift structures onto floating barges will be incentivized.

6. Every vulnerable city block will have a floating sidewalk to maintain connectivity between important points.

8. Jamaica Bay shall be considered a public space and amenity for all residents to engage with.

9. There shall be a public boat ramp and dock every half a mile of bay coastline.

Navigation through the Water

13. New municipal harbor access facilities will be built in partnership with maritime education and engagement programs to offer navigational support and services to the new boating community.

14. The public school system shall forge relationships with maritime access programs like Sail Rockaway and share facilities.

15. Every resident shall have free access to public pools and swim lessons (floating pool).

Previous page:

Top: new connections and activities at low tide

Middle: getting afloat on the Bay

Bottom: fieldwork photos

Above: sea level rise masterplan Left: proposed spatial strategy

Kirstin Baja

Baja is the co-Executive Director of Embodied Ecosystem and the Resilience Hub Collaborative. She supports an ecosystem of care centered in a “whole human- whole species- whole system” theory of change. Baja coaches, facilitates, and leads workshops, retreats, and trainings that nurture heartcentered self- and collective-liberation while supporting deeper connectivity within, with others, and with nature’s genius. She actively works to dismantle the systems of oppression at different scales and to dissolve the unchallenged “norms” that intentionally cause harm with a focus on building awareness, embodiment, and shifting power through action.

Larry Botchway

Larry Botchway, an architect and engagement enthusiast, co-founded POoR Collective and serves as a Senior Planning Engagement Officer, specializing in architecture, placemaking and urban strategy design.

Chandler Caserta

Chandler Caserta is a fourth year M.Arch

I student at Harvard GSD. Previously, he received his B.S. Arch from the University of Michigan.

Garrett Craig-Lucas

Garrett is a landscape architect whose research explores tools for engaging the landscape that promote imagination and stewardship, with a focus on coastal zones.

Randy Crandon

Randy is a Vietnamese American photographer and designer. Having grown up in New England, he is an avid sailor and part-time oyster farmer with a keen interest in maritime infrastructure. Randy is currently pursuing his Master of Architecture at Harvard GSD.

Jeanne Dupont

As founder and executive director of RISE (Rockaway Institute for Sustainability and Equity), Jeanne DuPont has worked closely with the Rockaway community and city agencies since 2005, developing strategies to redevelop large stretches of underutilized public land for the good of the community. Much of her work has involved organizing community members and youth in utilizing outdoor space for programming focused on social equity, health, and environmental justice. Jeanne has a master’s degree in Design from Yale University.

Anthony Engi-Meacock

Anthony is a founding partner of Assemble a multi-disciplinary collective working across architecture, design, and art. Founded in 2010 to undertake a single self-built project, Assemble has since delivered a diverse and award-winning body of work, whilst retaining a democratic and co-operative working method that enables built, social, and research-based work at a variety of scales, both making things and making things happen.

Martí Franch Batllori

Martí Franch Batllori is the founder & principal of EMF Landscape Architecture. His work has been internationally published and awarded with a LILA Landezine international landscape award 2016, ASLA American Society of Landscape Architects Honor Award 2012, European Landscape Biennal–Rosa Barba Prize 2012, as well as being a selected finalist in FAD 2012, Rosa Barba Prize 2010, and CCCB European Prize of Public Space 2012.

Tanya Gallo

Tanya Gallo is Co-Founder and Director of The Living City Project. She is an urban planner and educator with a focus on resilience, public space, and educational access. At 100 Resilient Cities at The Rockefeller Foundation,

she led a global network in resilience strategy development in collaboration with cities around the world

Andrew Meyers

Andrew Meyers is Co-Founder and Director of The Living City Project. Andy has dedicated over 30 years to high school and college education, specializing in urban history, college guidance, and experiential learning.

Bhavya Jain

Bhavya Jain is an MDes Ecologies Student from Jammu, India. Much of her time is spent questioning methods of practicing design and their future suited for the developing world.

Tawkiyah Jordan

Tawkiyah Jordan, a professional urban planner and self-described “city scientist,” is a fierce advocate, ally, political strategist, convener, negotiator, policy expert, and translator of power brokers and community stakeholders. Serving currently as Senior Director of Housing and Community Strategy at Habitat for Humanity International, Tawkiyah is an expert in housing, especially regarding long-term affordability models.

Nani Kauz Apolo

Nani is a Senior Urban Planner at WXY Studio working at the intersection of urban planning and public education. At WXY, Nani led a year-long evaluation of the Community School District 15 Diversity Plan in Brooklyn and the development of learning materials for adult and youth coastal stewardship in the Rockaways in partnership with local educators.

Steve Koller

Steve Koller is a Postdoctoral Fellow in Climate and Housing at Harvard University’s Joint Center for Housing Studies. His research focuses on climate risk mitigation, residential insurance, and federal disaster policy.

David Luberoff

David Luberoff is Director of Fellowships and Events at the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies, which provided funding that supported the Rockaways project.

Shannon Mattern

Shannon Mattern is the Penn Presidential Compact Professor of Media Studies at the University of Pennsylvania and the Director of Creative Research at the Metropolitan New York Library Council. She writes and teaches about libraries, archives, and other information architectures.

Deborah H. Morris

Deborah Helaine Morris, AICP, is an urban planner and urban designer. Her work centers at the nexus of climate adaptation, social equity, and physical health.

Doug McPherson

Doug McPherson is the interim manager and first staff member of the Residents Acquiring Land Edgemere Community Land Trust (the “ReAL Edgemere CLT”). He trained in City, Community and regional Planning at Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Rosalea Monacella

Dr Rosalea Monacella is a faculty member of the Landscape Architecture Program at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

Sam Naylor

Sam Naylor, AIA is an architect, educator, and researcher of housing in the US.

Carlo Raimondo

Born and raised in New York City, Carlo is interested in how landscape architecture moves beyond reflecting culture through design to enabling its emergent forms.

Helena Rivera

Dr Helena Rivera is a professionally qualified architect, chartered by the ARB and RIBA, and is founder and director of A Small Studio, which is an award-winning architecture firm in London specialising in site-specific and responsive projects that are thoughtfully designed.

Rosetta S. Elkin

Rosetta is the Principle of Practice Landscape, Professor and Director of Landscape Architecture at Pratt Institute, and an Associate of The Arnold Arboretum, Harvard University.

Kirsten Sexton

Kirsten Sexton is a Master’s in Architecture student at Harvard GSD interested in how architecture and design may promote climate resilience, encourage social mobility, and enhance community.

August Sklar

August Sklar is an interdisciplinary visual artist and designer studying Landscape Architecture at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design.

Samuel Stein

Samuel Stein is a policy analyst at the Community Service Society and the author of the book Capital City: Gentrification and the Real Estate State.

Ed Wall

Ed Wall explores practices of public space and processes of landscapes through concerns for spatial justice. He is Professor of Cities and Landscapes at the University of Greenwich, in London, where he leads the Spatial and Digital Ecologies research centre. He has a PhD from the London School of Economics and has been a Visiting Professor at Politecnico di Milano, Harvard University, and TU Wien.

Allen Wang

Allen Wang is a Master in Design Studies (Ecologies) student with a background as a service designer in the Government of Canada. He is interested in human-environment relationships, blending human-centred design with ecological thinking to explore how climate

change and other macroscopic issues impact people’s lives, and how to mobilize people towards planetary health and sustainable development in turn.

Makenzie Wenninghoff

Makenzie Wenninghoff is pursuing a Master’s in Urban Planning focusing on climate and health. Prior to the GSD, Makenzie spent 5-years working with impacted communities in Puerto Rico and Florida.

Piper Claudia Williams

Piper Claudia Williams, was born in NYC and lives on Fire Island. She is currently an MDes Ecologies student and previously studied sculpture & architectural history at Hamilton College.

Jane Wolff

Jane Wolff is a professor at the University of Toronto. She was educated as a documentary filmmaker and landscape architect at Harvard University. Her activist scholarship uses writing and drawing to decipher and represent the web of relationships, processes, and stories that shape everyday landscapes in the Anthropocene. Her projects translate between rigorous, specialized information and ordinary language to make difficult (and often contested) places legible to the wide range of audiences with a stake in the future.

Mabelle Zhang

Mabelle is a second-year Masters of City Planning student at MIT DUSP, with development and policy experience and a focus on public realm planning and design.

Sofia Zuberbuhler-Yafar

Sofia has extensive experience in the planning, design and construction management of public and private projects. Presently, she leads in the integration of climate readiness, sustainability, resiliency, and equity into NYC DDC’s billiondollar infrastructure capital work. Sofia also oversees green infrastructure projects and urban landscape design solutions.

Benedetta Zuccarelli

Benedetta Zuccarelli is an Italian researcher and architect exploring climate-responsive design and sustainable building strategies to create resilient and environmentally adaptive urban spaces.

Rockway’s Housing Superstorm

Instructor

Ed Wall Report Design

Benedetta Zuccarelli

Report Editor

Benedetta Zuccarelli

Dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture

Sarah Whiting Chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture

Gary Hilderbrand

Copyright © 2024 President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without prior written permission from the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

Text and images © 2024 by their authors.

The editors have attempted to acknowledge all sources of images used and apologize for any errors or omissions.

I am indebted to the current Chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design, Gary R. Hilderbrand, for his generous invitation, steadfast support, and continued guidance in this project. I am also extremely appreciative of the current Dean, Sarah Whiting, for supporting this project and its publication.

The project was only possible through the partnership with RISE (Rockaway Initiative for Sustainability and Equity), funding from the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, and the support of the Department of Landscape Architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

The support we received during our visits to the Rockaways was invaluable, including from Nani Kauz Apolo (WXY), Sam Stein (Community Service Society), Jeanne DuPont (RISE), RISE staff, Rockaway residents, Tanya Gallo and Andrew Meyers (Living City Project), Doug McPherson (Real Edgemere CLT), Sofia Zuberbuhler-Yafar (Sustainability & Urban Design NYC DDC).

Harvard University Graduate School of Design 48 Quincy Street Cambridge, MA 02138

gsd.harvard.edu

I would also like to thank the guests and critics who joined us, including: Shannon Mattern (University of Pennsylvania), Helena Rivera (A Small Studio), Deborah Helaine Morris (Columbia Climate School / NYC Health and Hospitals Corporation), Anthony Engi-Meacock (Assemble), Sam Naylor (Utile), Jane Wolff (University of Toronto), Kristin Baja, Rosetta S. Elkin (Pratt), Martí Franch Batllori (EMF), Larry Botchway (PoOR Collective), Jeanne Dupont (RISE), Tawkiyah Jordan (Habitat for Humanity / Loeb Fellow), David Luberoff (Joint Center for Housing), Steve Koller (Joint Center for Housing Studies), and Rosalea Monacella (Harvard University GSD).

I wish to extend my gratitude to Benedetta Zuccarelli for the design and production of this report and to Giles Ashford/RISE for the photographs of the community workshops.

Finally, the greatest thanks to the students for their dedication and wonderful contribution:

Chandler Caserta, Garrett Craig-Lucas, Randy Crandon, Bhavya Jain, Carlo Raimondo, Kirsten Sexton, August Sklar, Makenzie Wenninghoff, Allen Wang, Piper Claudia Williams, Mabelle Zhang, and Benedetta Zuccarelli.

Image Credits

Cover:

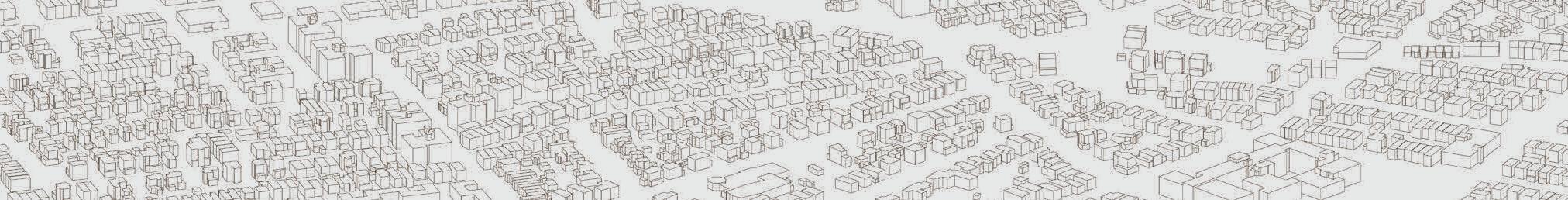

View of the Rockaways by Chandler Caserta

Inside cover:

View of Jamaica Bay from the Rockaways by Ed Wall

Harvard GSD Department of Landscape Architecture

Chandler Caserta, Garrett Craig-Lucas, Randy Crandon, Bhavya Jain, Carlo Raimondo, Kirsten Sexton, August Sklar, Makenzie Wenninghoff, Allen Wang, Piper Claudia Williams, Mabelle Zhang, Benedetta Zuccarelli