Eric Rodenbeck

Eric Rodenbeck

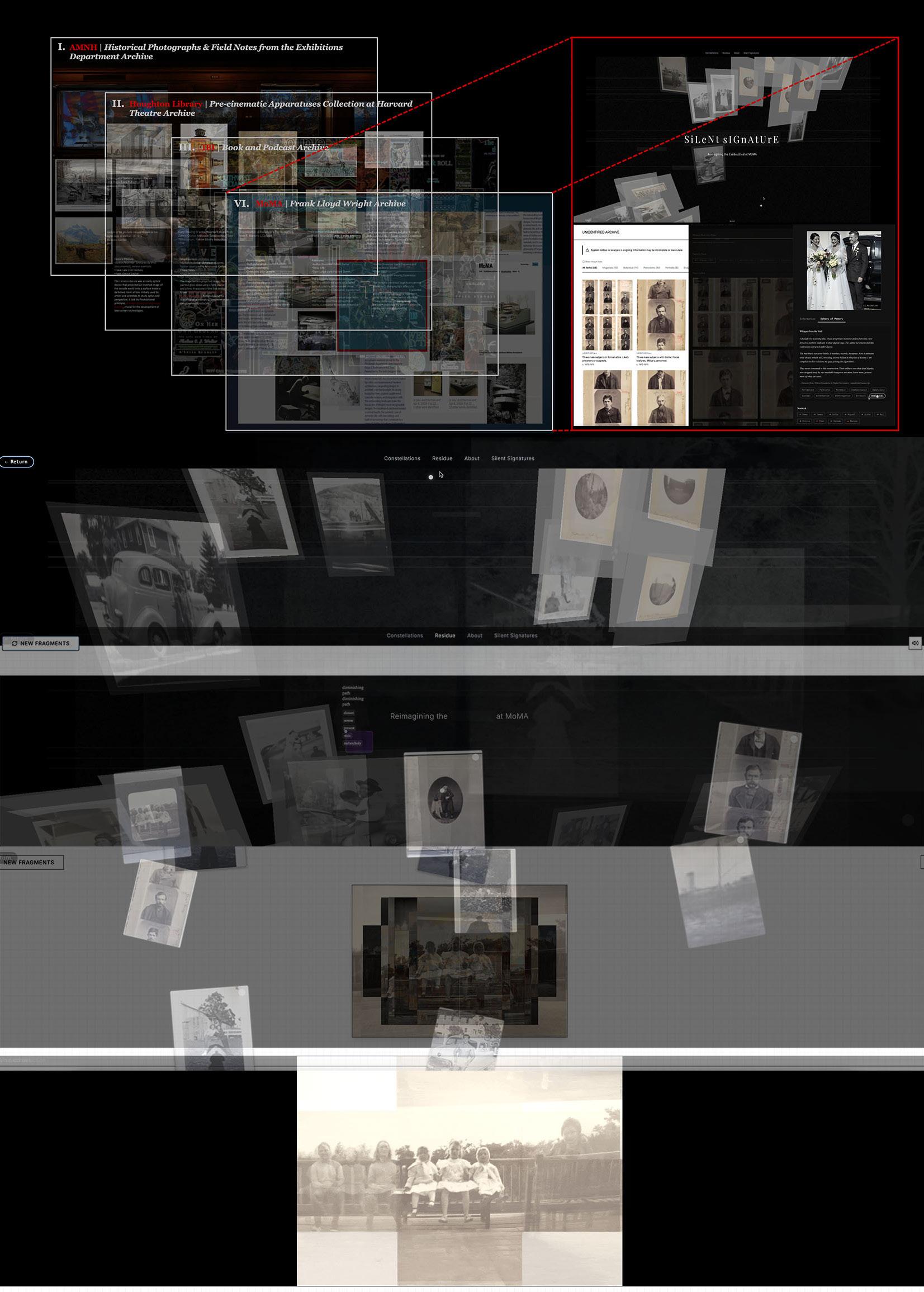

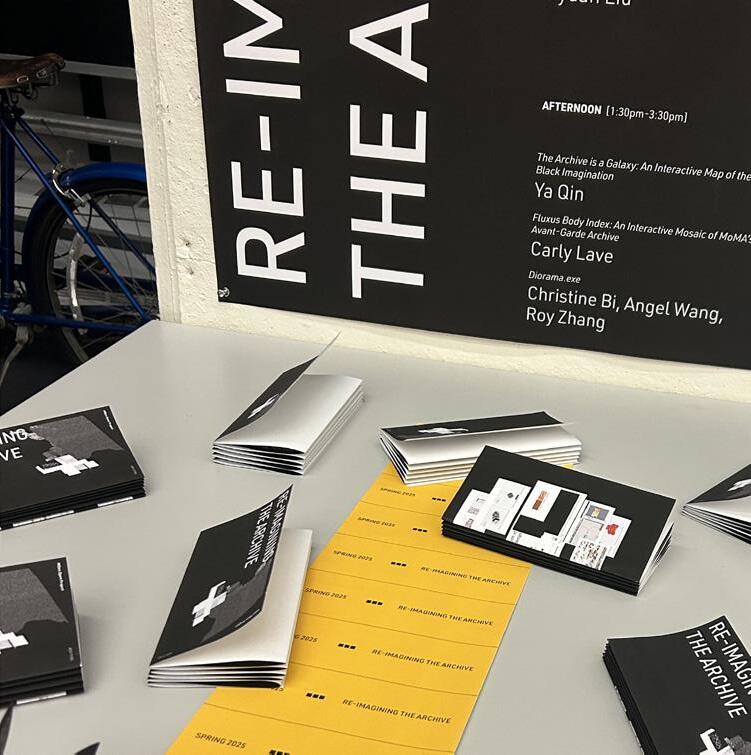

MDes Open Project: Re-imagining the Archive

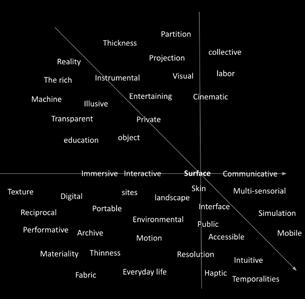

Archives are never neutral, complete or perfectly accurate. They are always inscribed by power, history, practice, and culture. Working in collaboration with prominent institutions, this Open Project engaged students in the process and practice of designing and developing data visualizations of their archival holdings.

Studio Instructor

Eric Rodenbeck

Teaching Associate

Eric Rannestad

Students

Shiman Xu, Ben Kazer, Kevin Tang, Yuanqing Xie, Ya Qin, Carly Lave, Christine Bi, Jyuan Liu, Angel Wang, Roy Zhang

Final Review Critics

Dario Calmese, Charles Waldheim, K. Michael Hays, Ben Fry, Josh Draper, Annie Simpson

What is an Archive? It’s what’s left behind after the forgetting. It’s the crime scene of knowledge: bodies rearranged, evidence mislabeled, histories redacted. It’s memory manipulated, curated, and sometimes weaponized. We wanted to re-imagine an approach to archives that would take them seriously: not as neutral repositories of information, but as sites of violence, ruthless culling, and power.

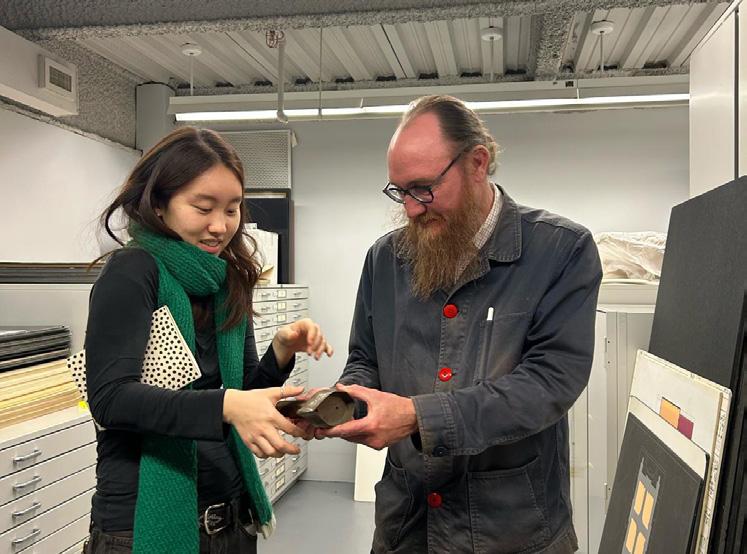

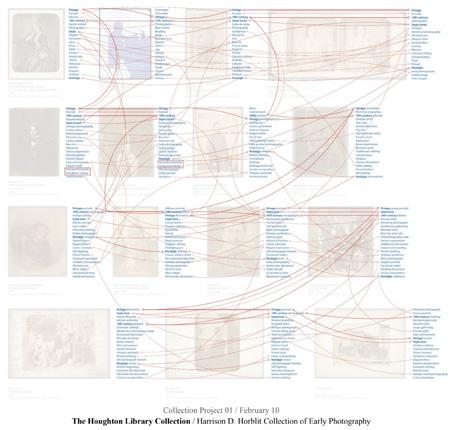

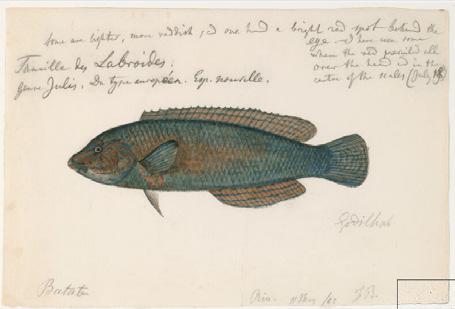

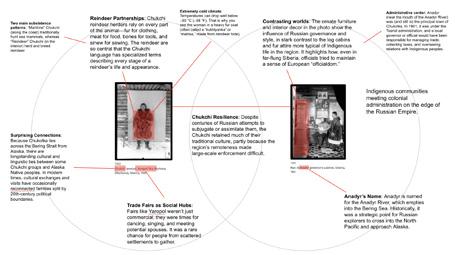

We chose four archives, for their curators’ willingness to open their doors and engage us in expert conversation: the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), the Institute of Black Imagination (IBI), Houghton Library, and the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH). We visited each of them over the course of the workshop. What drew us in? Not just the objects, although it was great to have access to these giant warehouses full of treasure, but the contradictions, the gaps. MoMA’s crates were as sexy as their paintings, tagged like fugitives who’ve fled across continents. IBI’s books whispered truths and textures you’d never find in a museum catalog. Houghton let us handle 900 years of manuscripts like we were just flipping through old receipts. And AMNH let us play dress-up with the deep past: diving helmets, dead animals in miniature, and the quiet hum of colonial taxonomy with all its violence. Paul Galloway at MoMA, Iris Lee at AMNH, Dario Calmese at IBI and Kristine Greive at Houghton were kind enough to give us their time and access to their collections, and we couldn’t have done this work without them.

The similarities across institutions were as instructive as the differences. At MoMA, touch and photographs were taboo in an unmarked building on a flood plain in Queens. At AMNH, touch was mandatory and we explored cabinets full of sextants and rooms stacked high of North Pole expedition sleds. IBI’s books came glove-free, like they trusted us with their secrets. Houghton’s manuscripts were shelved by century, as if time could be domesticated. Each institution’s posture towards their collections said something about power. About who gets to

touch, who gets to look, and who gets to tell the story.

We didn’t aim for polish, and we didn’t fetishize the final. We made nine projects each over the course of a single semester, because continuous iteration is a kind of rebellion. In a university system that rewards perfection and scarcity, we chose abundance and velocity. We purposely stayed away from overly finished work and biased towards work in progress.

We made bad work, weird work, brilliant

to neural networks like confessions, broke conversations into fragments and sorted through the debris. We created a new archive: the tools, the tactics, the digital residue of the spring 2025 creative arms race.

We treated the course as a workshop. Mondays we reviewed work; not proposals for future speculative projects, but real investigations into the substance of these datasets. Tuesdays were studio days, where we came together in person around a big table and worked

failures. One of my favorite presentations started with “I tried (and failed) to download hundreds of images from MoMA.” We moved too fast to be overly precious, and mistakes were an important part of the work. By pressing right up against the face of what computation can do, we started to develop a sensibility for what archives can and can’t say, and that sometimes the most beautiful and provocative and useful messages are to be found in what they are silent about.

David Newbury at the Getty gave me some advice before I taught the course that has stuck with me: “If you want them to make that much work, they’ll have to cheat.” Boy did they cheat! With whatever AI tools they could find for free, with vibed code, with duct tape, accidents and mistakes. The practitioners scraped data, hallucinated citations, secretly whispered prompts

together. We spent two weeks on each archive, and delivered and reviewed two projects for each archive. These shortened timeframes did a couple of things: they introduced participants to the production schedules that often characterize commercial work; they broke us all out of the mindset of putting all our energy into a “final” project; they made each project and presentation (including the failures that accompanied them) less precious; and they opened the possibility for a state of flow. We tried to get out of our own way, in response to the specific poetics of each archive, and do as John Cage exhorts us to do: start anywhere.

The iterative nature of the work was a deliberate rebuttal of archival certainty. Archives are often understood as fixed, authoritative and neutral repositories of truth; here, they became sites of instability, of gaps and contradictions brought into relief by algorithmic misfires and hallucinatory outputs. As a result of the speed & public nature of the presentation requirements,

participants were encouraged to treat speculation as a method, to understand that the archive is as much about its silences as its contents. The pedagogical insistence on iteration reinforced this shift. It trained practitioners to approach the archive not as a static sacred object but as a living field of interpretation, where uncertainty becomes a generative force.

By the end, we stopped asking what an archive is. We started asking: what does it hide? Who does it serve? And who gets to burn it down?

We didn’t just visit archives. We cracked them open and danced in the wreckage. We had a great time! I hope you’ll enjoy what we learned.

Kevin Tang

When I signed up for “Reimagining the Archive”, an Open Projects (OP) studio at Harvard GSD led by Eric Rodenbeck, I arrived with one set of expectations and left with another entirely.

Only months before, MIT’s 6.1040 “Software Design” had flipped my mindset about building full stack web applications. Until then, I’d lived in the physical realm—industrial design, hardware prototyping, 3D printing, electronics and sensor work. Sure, I could program microcontrollers to drive motors and actuators, but crafting web apps, databases, or user-flow logic felt like wrestling with a black box.

Pre-Course

Learning to Think Like a Software Engineer

MIT’s top-down approach to web development changed that. Diagramming systems into modular concepts, sketching data flows, then methodically implementing each layer gave me a clear framework. I deployed a full-stack app on Vercel, linked it to MongoDB, stored images as base64 strings, called external APIs, and managed reactive states. I’d be lying if I said the process wasn’t tedious, but it reframed programming as a logic puzzle rather than a chore. By semester’s end, I’d gained both the mental framework and the confidence to embrace “vibe coding”, letting AI-generated snippets boost speed and accuracy.

Engineer Mindset (“Make It Work”)

Entering OP, I was confident but my bar was modest: functional prototypes that looked presentable, ran without fatal errors, and responded under 100 ms. Sliders, dropdowns, straightforward backends—I built what I needed and moved on. Beyond basic usability, user experience felt like a luxury I couldn’t afford.

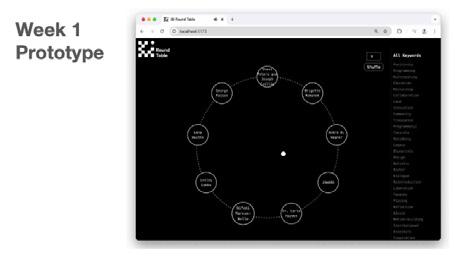

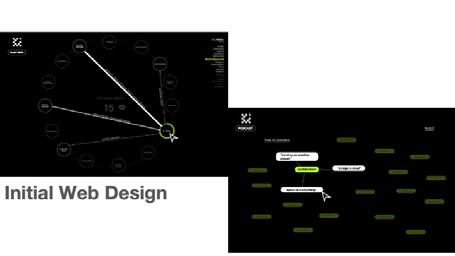

Midway through the term, that comfort evaporated. Proud of my weekend’s work, an

audio-query interface for a podcast archive, I demoed it in class and watched a peer with no prior coding background deploy a similar, but polished, animation-rich version, built with AI. Panic set in. Hours spent wrestling with UI alignment and manually debugging through console.log now felt like a bygone era.

Design-Centered Build (“Make It Delightful”)

That moment revealed a truth: when AI handles boilerplate and scaffolding, design becomes the differentiator. Detailed Figma prototypes (precise gradients, exact border radii, layered shadows) weren’t for engineers, but prompts for AI. An exported mock-up could prompt CSS generation. Before-and-after screenshots defined hover-state animations. Iterating on micro-interactions, animations, and transitions replaced stitching together backend routes. Suddenly, my role shifted from coding and debugging to curating aesthetics and experiences.

Archive as Narrative (“Make It Meaningful”)

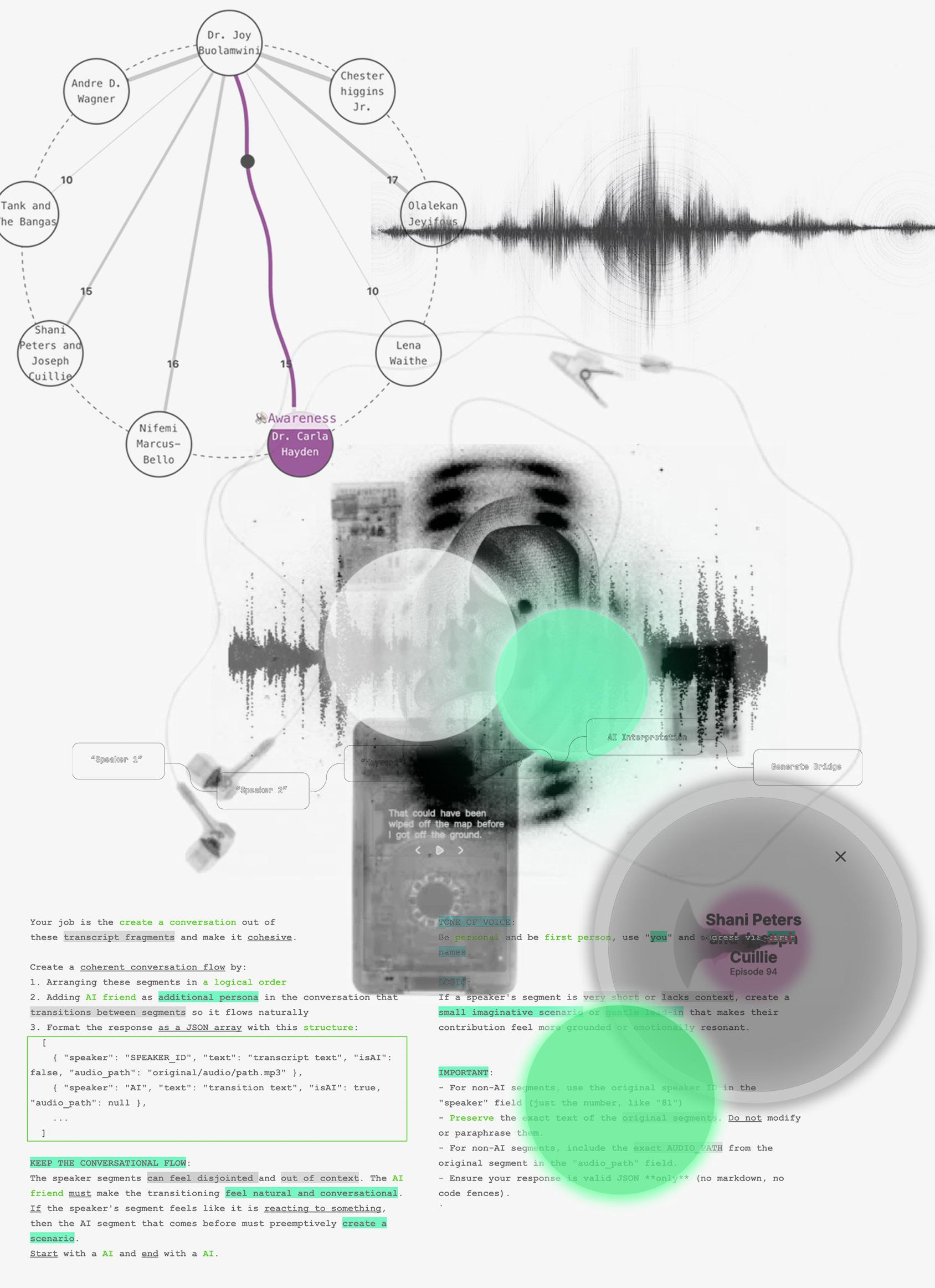

Up until the end of the semester, I approached projects as a simple retrieval pipeline: “build search,” “filter by tag,” “display results.” After seeing more than twenty demos in class, however, I sensed something was amiss—I realized AI could add a layer of interpretation and nuance to queried results.

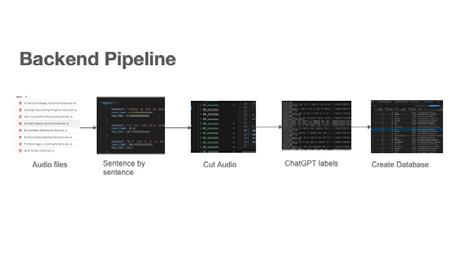

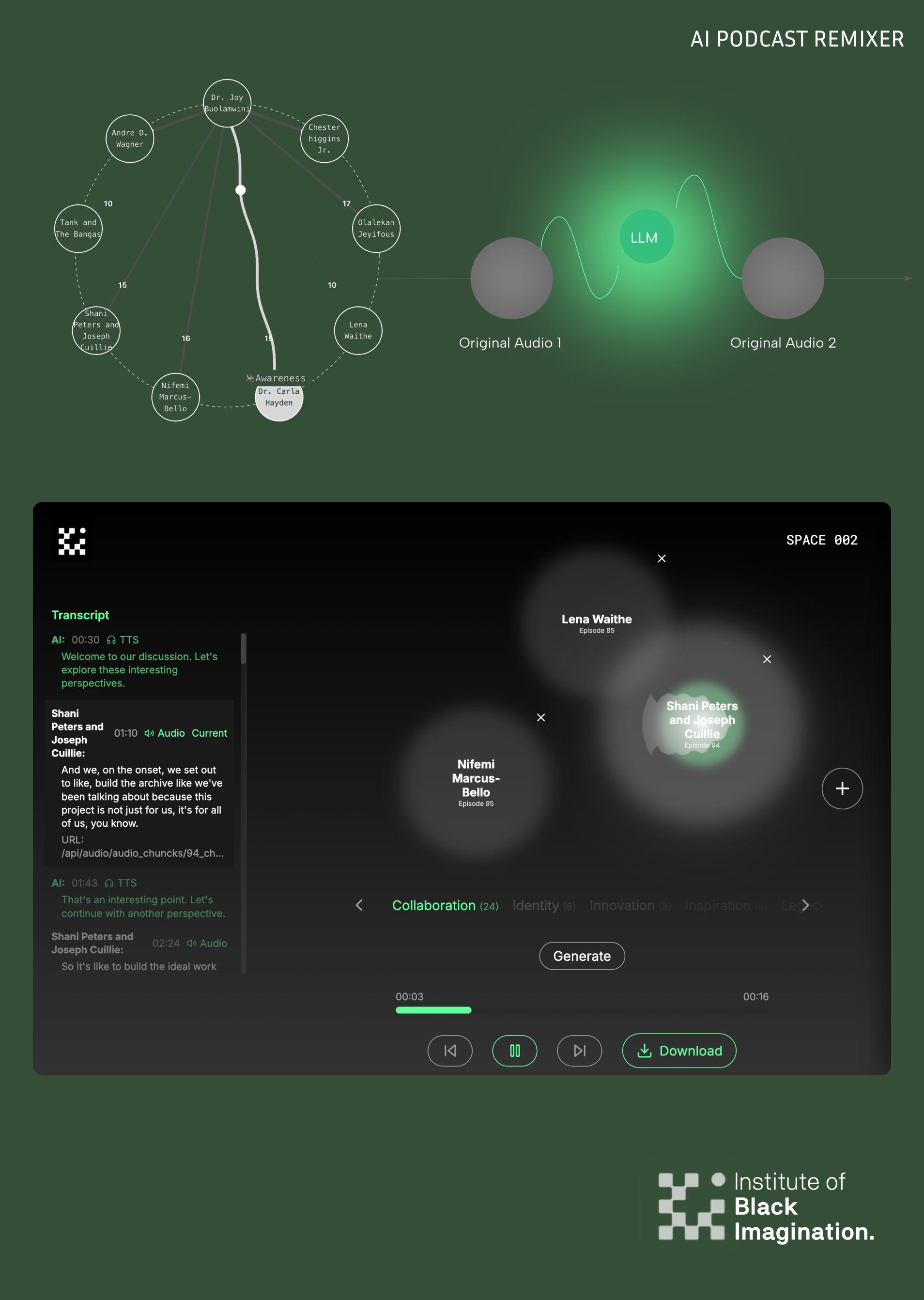

An “Aha” moment dawned: AI could do more than “vibe coding”—it could become an integral part of the archive interface itself, augmenting and amplifying the material rather than merely automating code generation. To unlock that potential, we have to start upstream—in how we structure and label our data. By breaking each podcast episode into sentence-level chunks and enriching them with transcripts, semantic keywords, and timestamps,

I created a brand-new archival layer from the same material, opening up narrative possibilities I hadn’t imagined.

Designing an AI-powered interactive archive is less about generating new content and more about revealing hidden relationships within existing materials. Accordingly, my project pivoted from building query interfaces to architecting a robust metadata schema: hierarchies of topics, time-based chunking of episodes, and sentiment tags on each segment.

With that foundation in place, I moved beyond “search and filter” to crafting relationships. AI became a sense-making layer— suggesting connections (“these two speakers reference ‘design’”) and highlighting thematic overlaps across episodes. In this role, AI amplifies archival intuition rather than replacing it.

Finally, I recognized that an archive is not just a database; it’s a living narrative shaped by metadata. I shifted from building queries to crafting relationships—layering transcriptions, clustering content, encoding provenance. AI’s job was to reveal patterns I couldn’t see alone, to suggest connections, to highlight gaps.

“Reimagining the archive” for me now means designing an ecosystem where humans and AI collaborate to surface hidden stories. The designer’s role has evolved: our task is to shape the conditions that enable AI and people to co-discover insights. There is a growing appetite for transforming static collections into dynamic, living experiences that invite exploration and serendipity. In this new paradigm, coding remains essential—but the real art lies in constructing the scaffolding of meaning.

At the conclusion of the course we compiled a list of technologies we used througout the semester. We treated the course as a workshop, with everyone sharing their tools and expertise as they learn.

AI + Machine

Learning

BLIP

ChatGPT

Claude CLIP

DeepFace

Google NotebookLM

MediaPipe

OpenAI API

OpenAI GPT-4

Runway AI

TensorFlow.js

WebGazer.js

v0

Programming + Frameworks

D3.js JavaScript Node.js Processing Python Tone.js & Wavesurfer.js Vue.js

p5.js Tailwind

Visualization

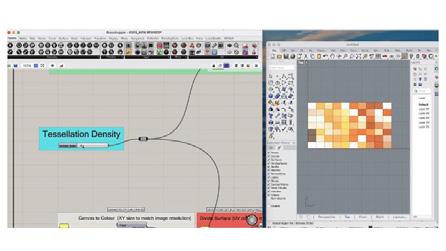

8th Wall Grasshopper

Open Seadragon Rhino Three.js

Databases + Cloud

AWS S3

Google Cloud Platform SQLite Turso

Design + Media

Adobe Illustrator

Adobe Photoshop Figma

InDesign

Premiere Pro Runway AI

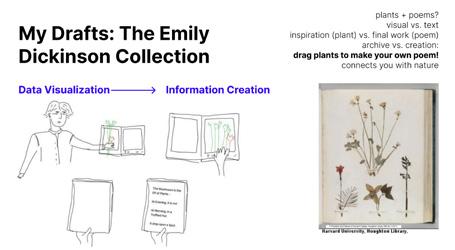

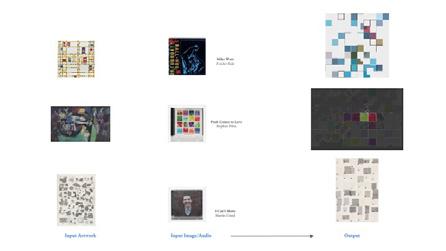

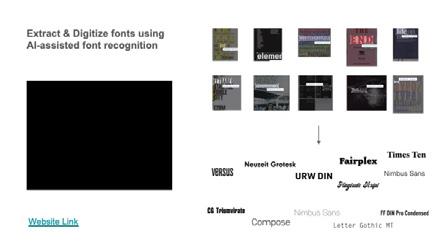

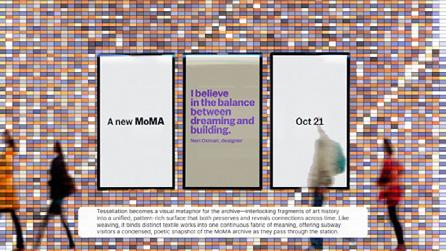

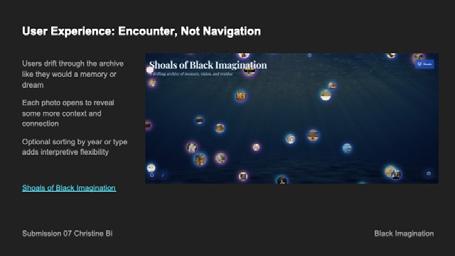

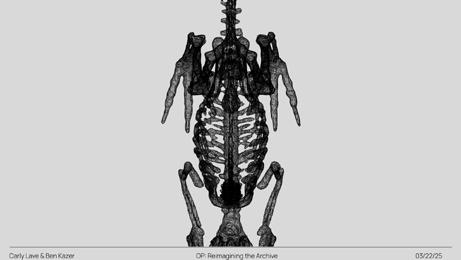

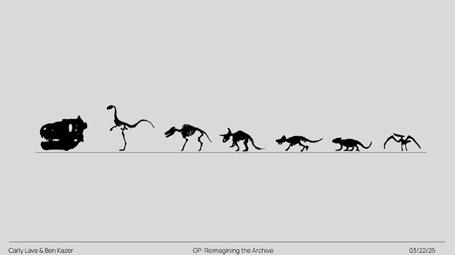

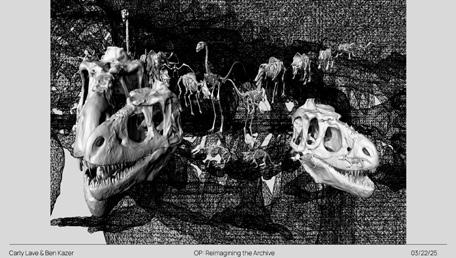

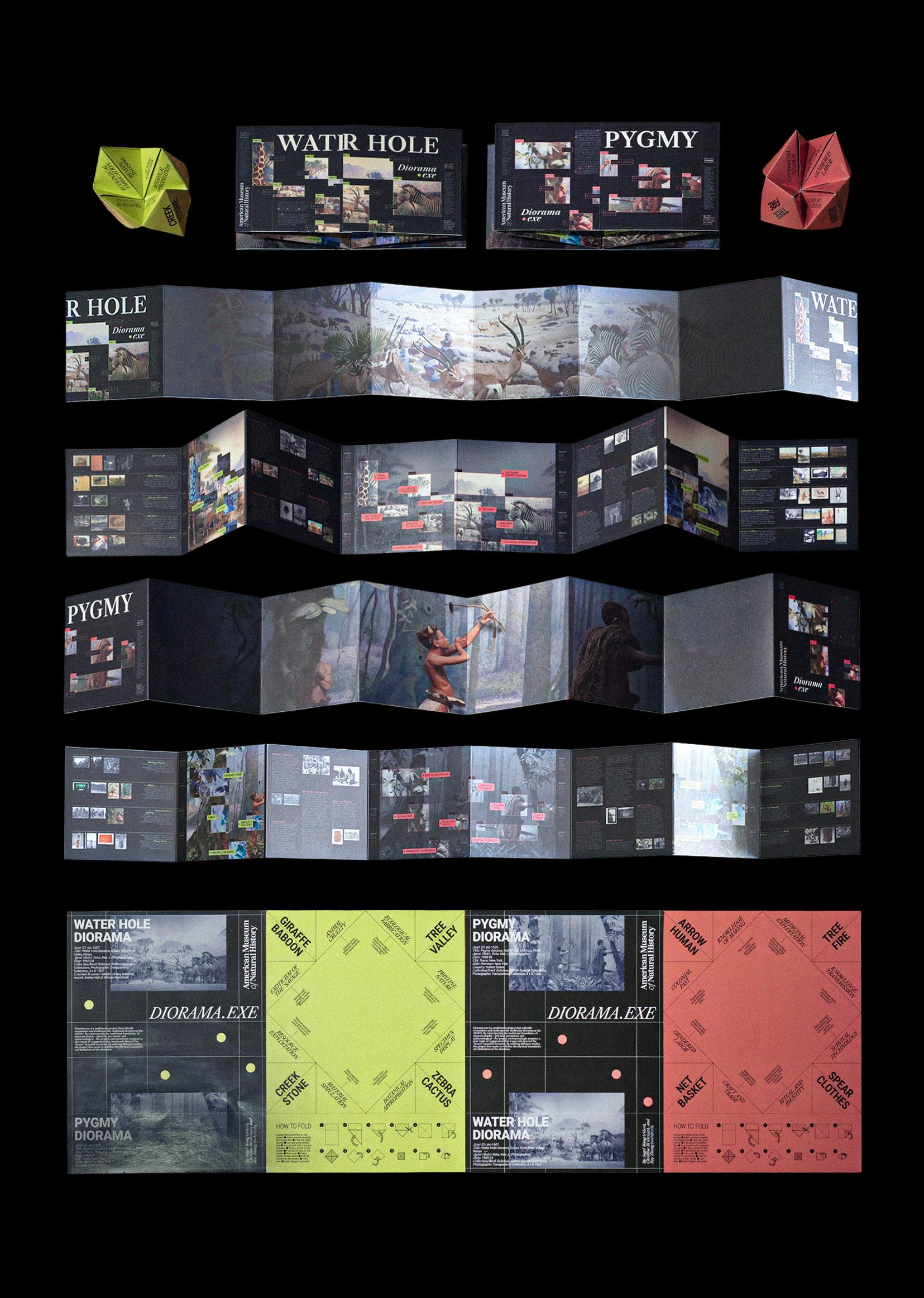

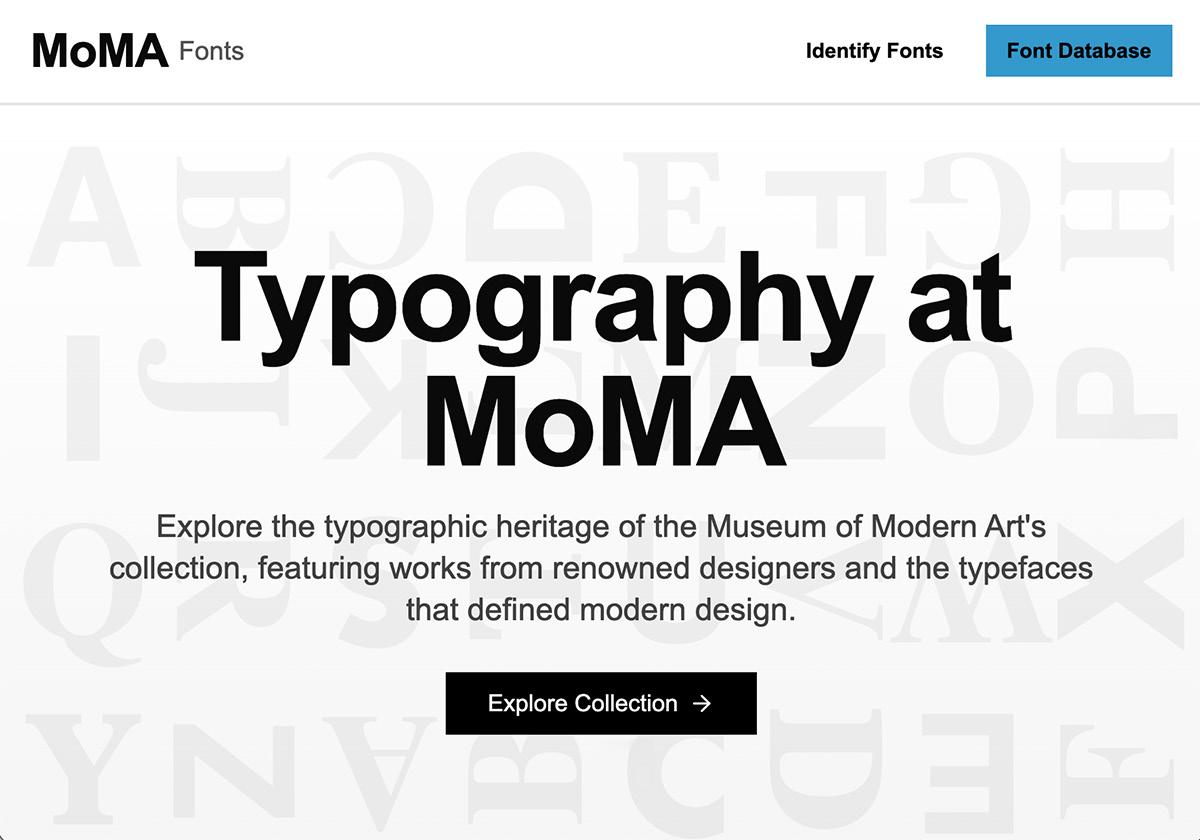

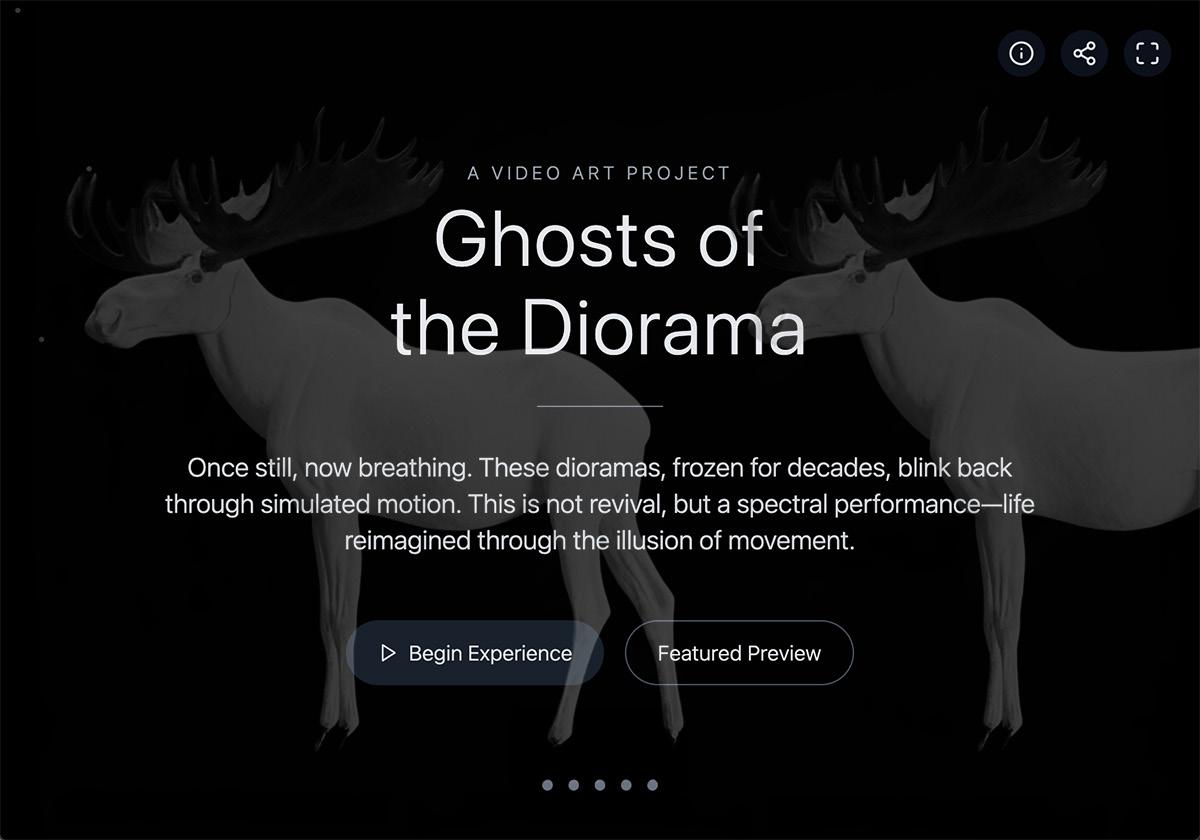

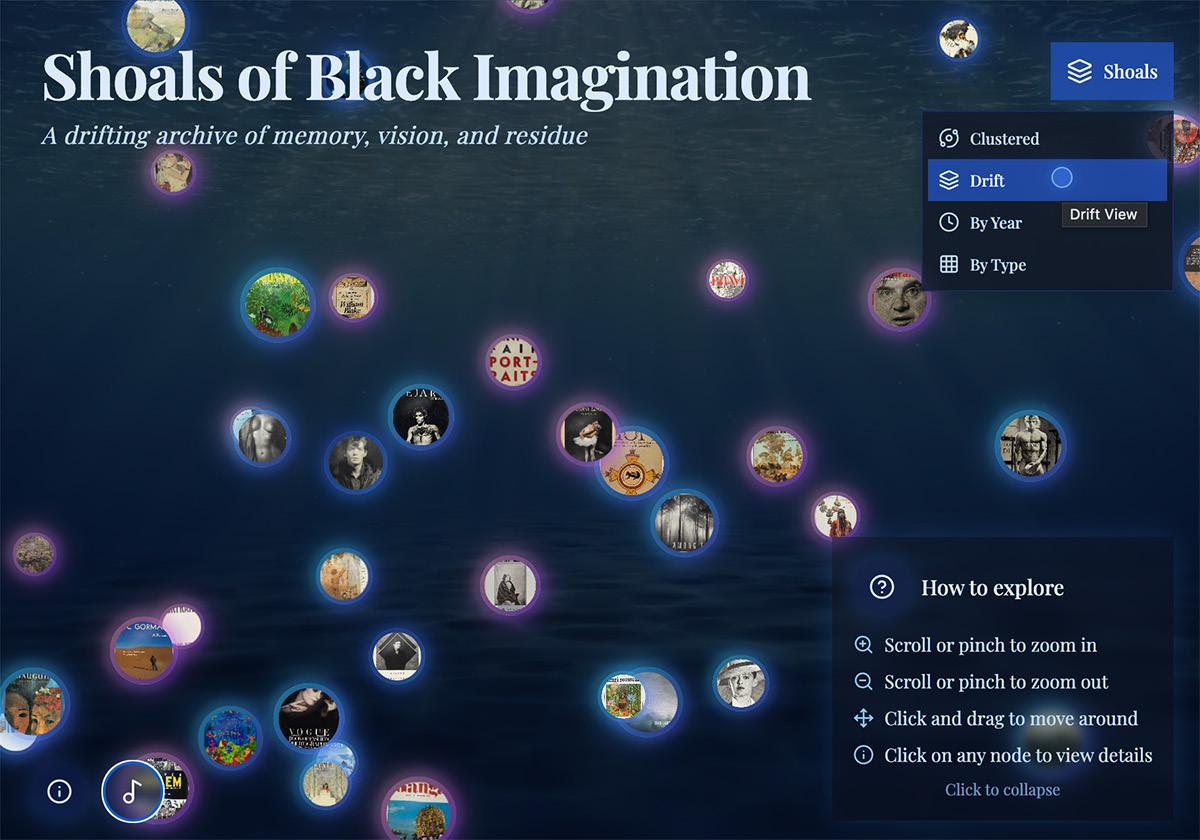

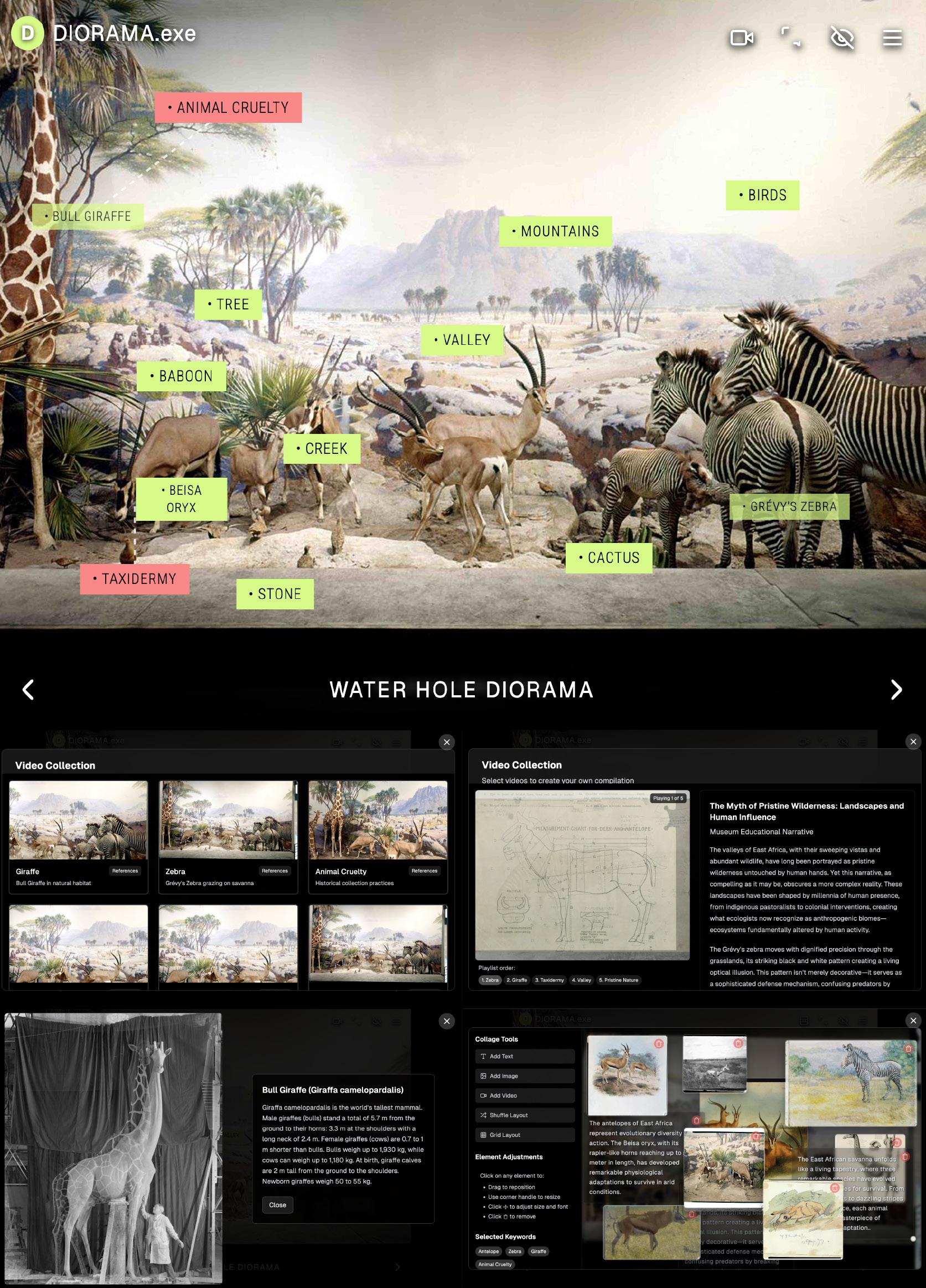

This course reshaped how I understand and work with archives. I started by reviving a 19th-century typeface and later created an AI-assisted font database—early attempts to reveal overlooked visual elements. I then experimented with animation in Ghosts of the Diorama, using AI to simulate motion in static images. Inspired by The Black Shoals, I built an interactive, drifting archive that visualizes memory as fluid and nonlinear. Through each project, I began to see visualization less as explanation and more as speculation.

The semester culminated in a collaborative final project with two classmates. They developed a digital platform and video, while I focused on the physical experience—designing foldable zines and posters that reimagined AMNH dioramas through layered, participatory storytelling. This process taught me to treat archives not as fixed sources, but as evolving terrains shaped by access, gesture, and imagination. Moving forward, I want to continue using design as a way to question systems of knowledge—creating tools and spaces that invite others to explore, reinterpret, and engage on their own terms.

Instructor Commentary

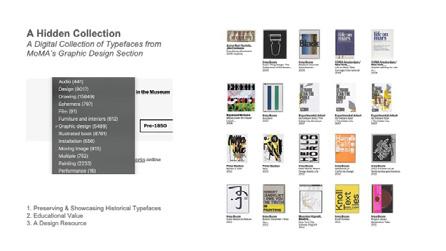

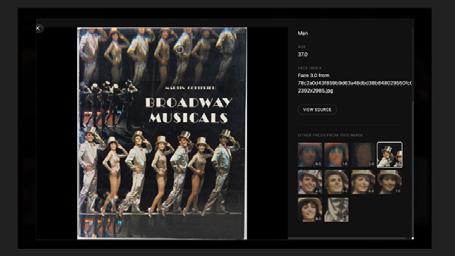

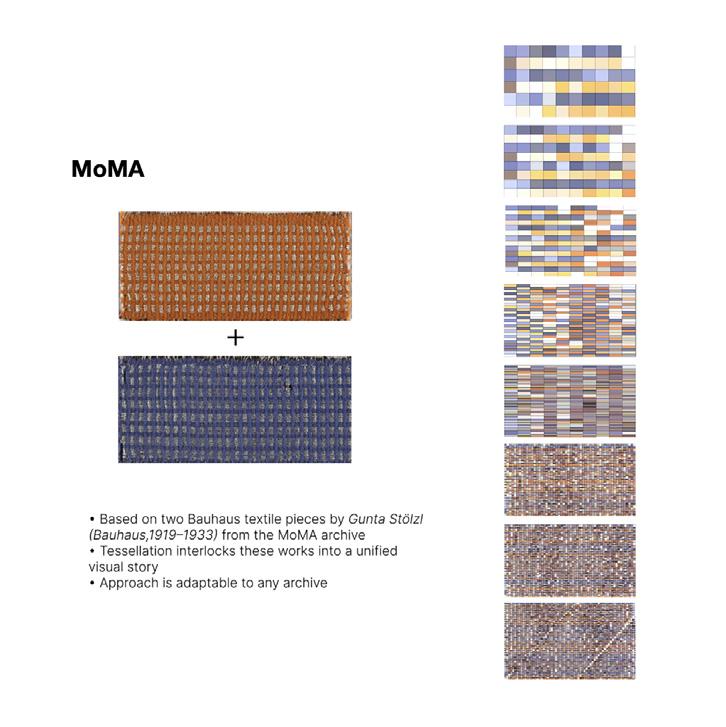

Christine built, among other things, a gallery website that lets you browse all of MoMA’s online graphic design collection by font. So instead of sorting them by author, or subject, or year, the project brought all the pieces that used Futura, or Helvetica, or Garamond, and displayed them together. Authorship became secondary to typographic style. For me this was a prime example of what AI is (currently) good for: it lets you realize, with very low starting costs, a good-enough version of an idea, to let you see whether it’s worth really putting in the effort to build out. After you got four or five levels deep into the project, it started to break down and the machine hallucinations became evident. But she showed that it was an idea that had legs.

Bottom:

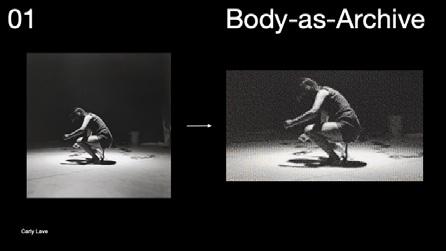

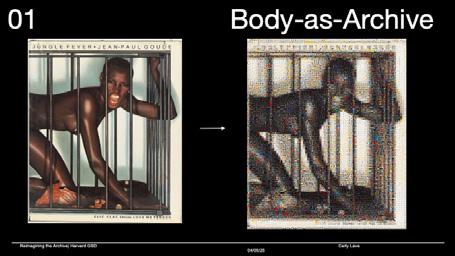

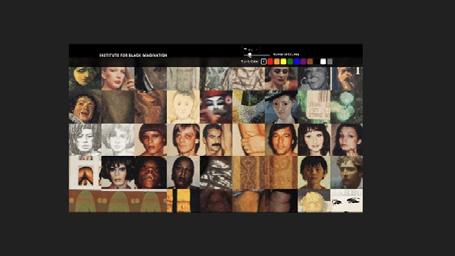

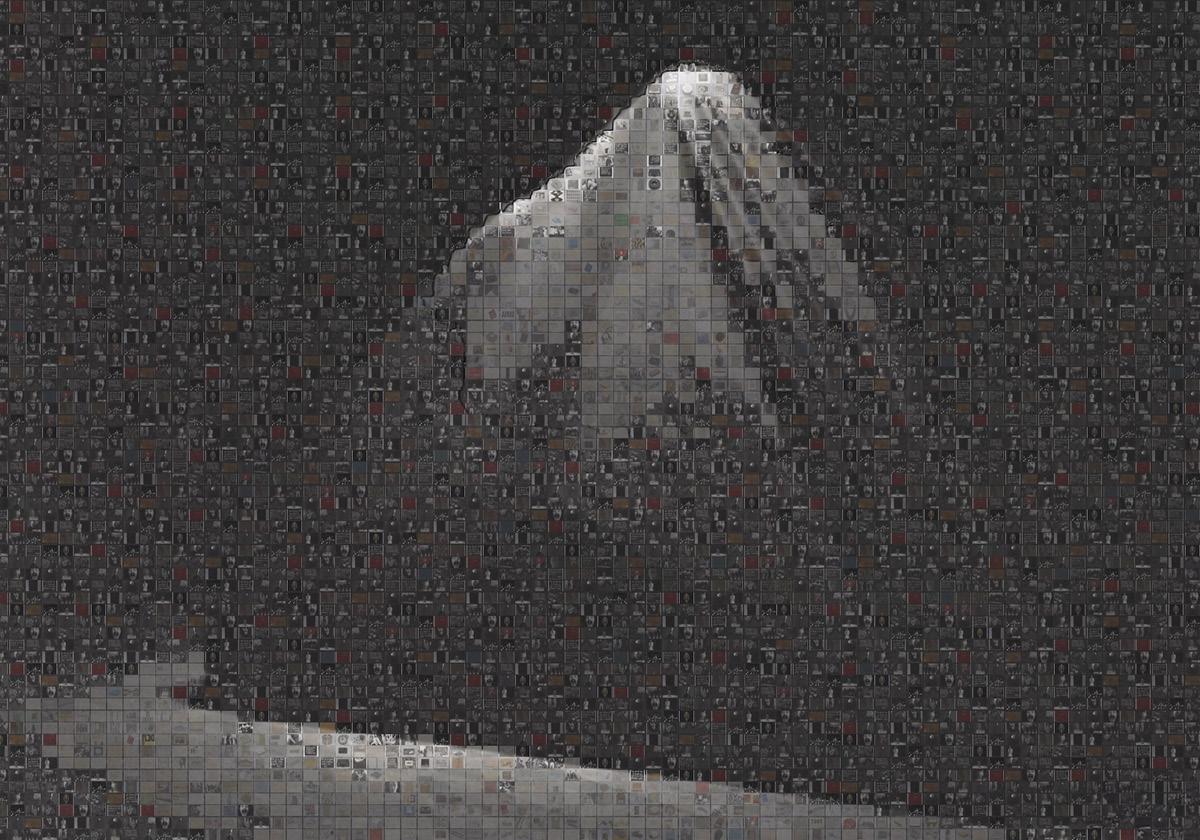

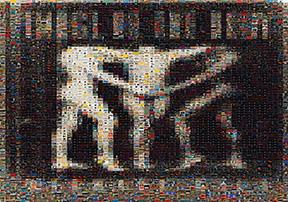

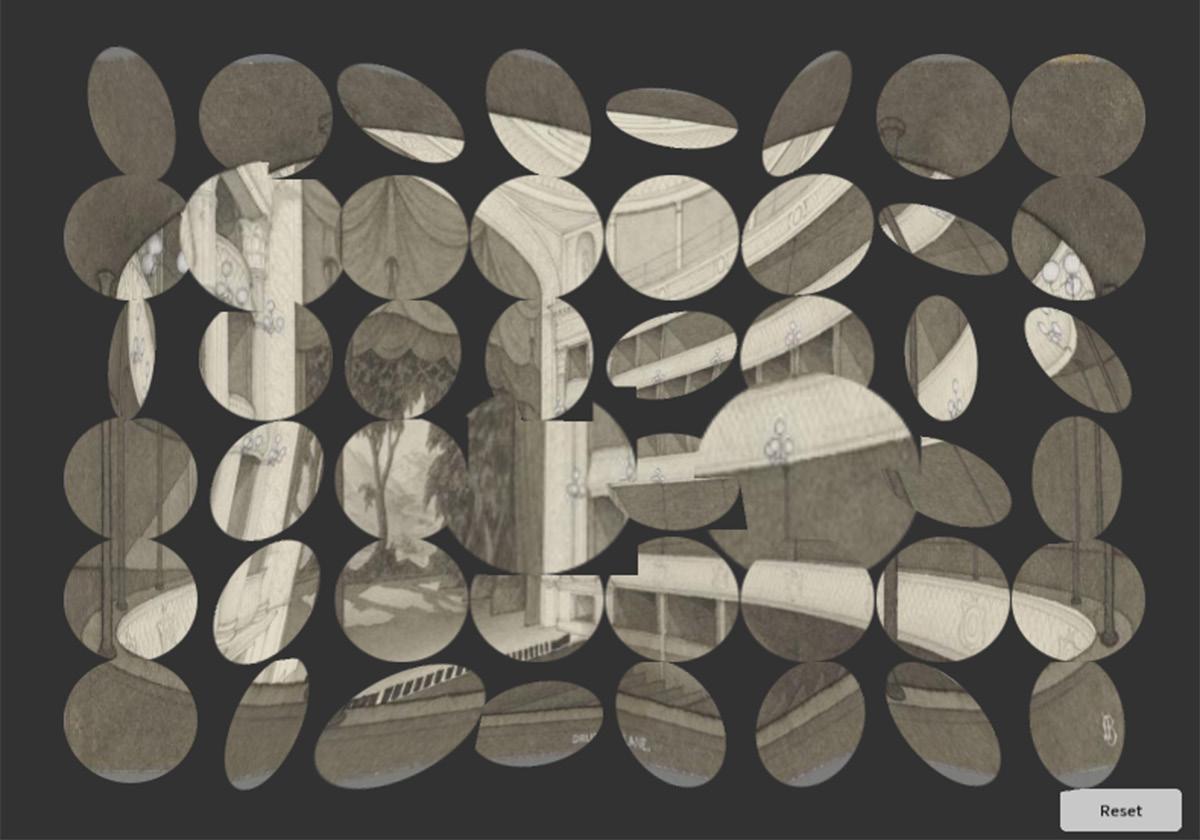

Over the semester, I have explored the photomosaic as both technique and metaphor—layering countless Fluxus fragments into a single, expansive portrait of the Collective’s spirit. Exploring various museums archives such as the Institute for Black Imagination among other, the Collection at MoMA holds thousands of images, documents and performance records by artists like Terry Riley, Yoko Ono and John Cage; my work uses those archival tiles to probe how process—rather than polished outcome—can generate new forms of meaning. Each thumbnail, drawn from archive becomes a living pixel in a larger mosaic that evolves with every user interaction, echoing Fluxus’s embrace of chance, participation and the performative body. This interactive web experience—Fluxus Mosaic—positions the photomosaic concept at its core. Over the course of the semester, I’ve refined scripts to parse archive metadata, mapped image-to-grid algorithms in Python, and designed front-end interactions in JavaScript so that clicking any cell not only reveals the original performance behind it but also reframes the digital body as archive. In doing so, the project brings Fluxus’s ethos into the digital age: users navigate their way through datadriven bodies and artworks, uncovering layers of history one pixel at a time while contributing to an ever-shifting collective portrait.

Instructor Commentary

Carly took a well-understood technique and turned it on its ear. Different photomosaics showed subtle differences depending on whether the thumbnail imagery came from Fluxus, or dance, or portraiture. She used one of my favorite techniques, repetition and small variances, to explore how the contents of an archive can influence the way in which that archive is represented. Visualizations are not just containers for neutral viewing!

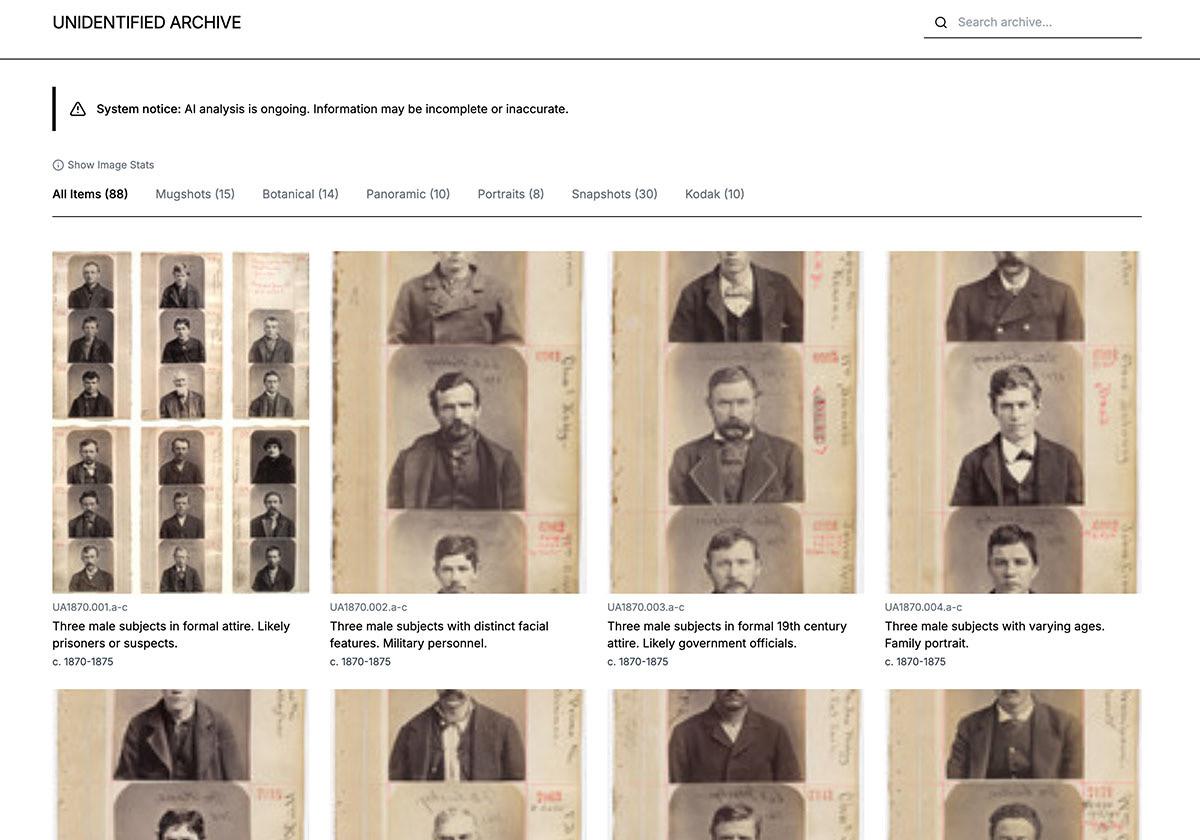

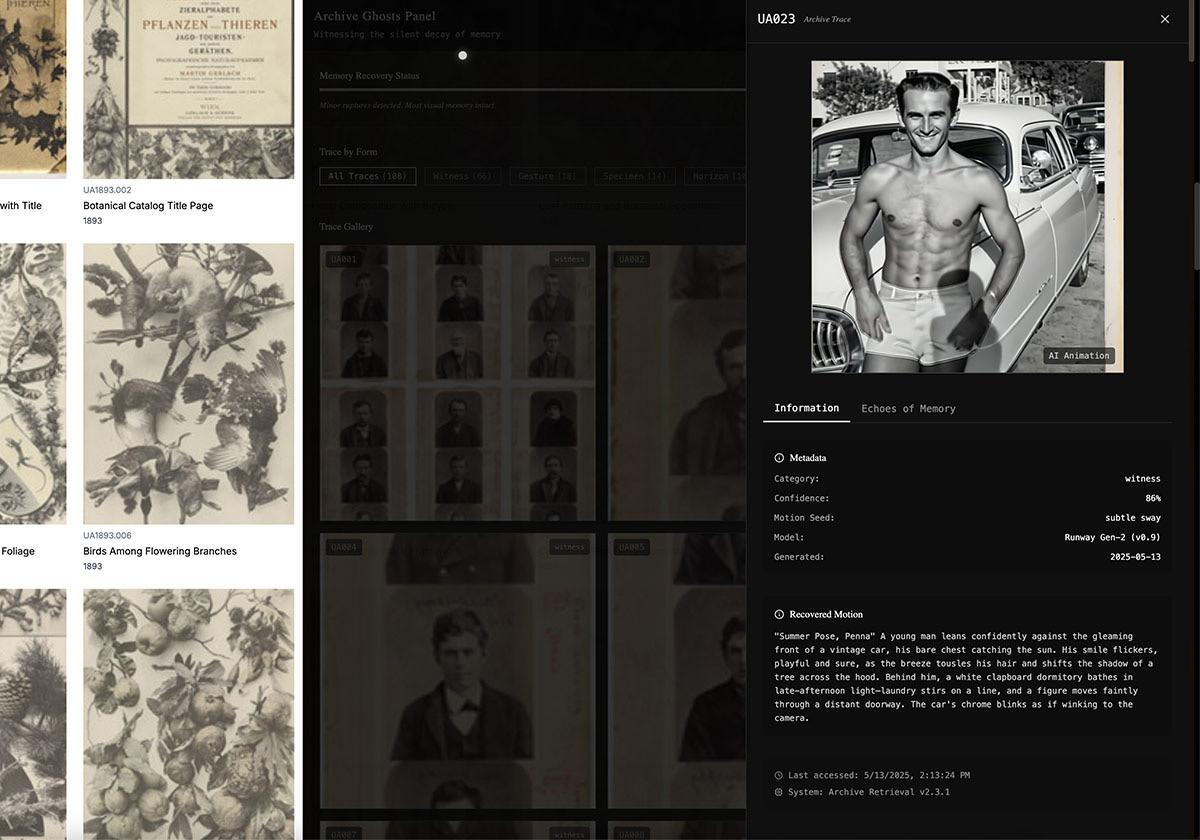

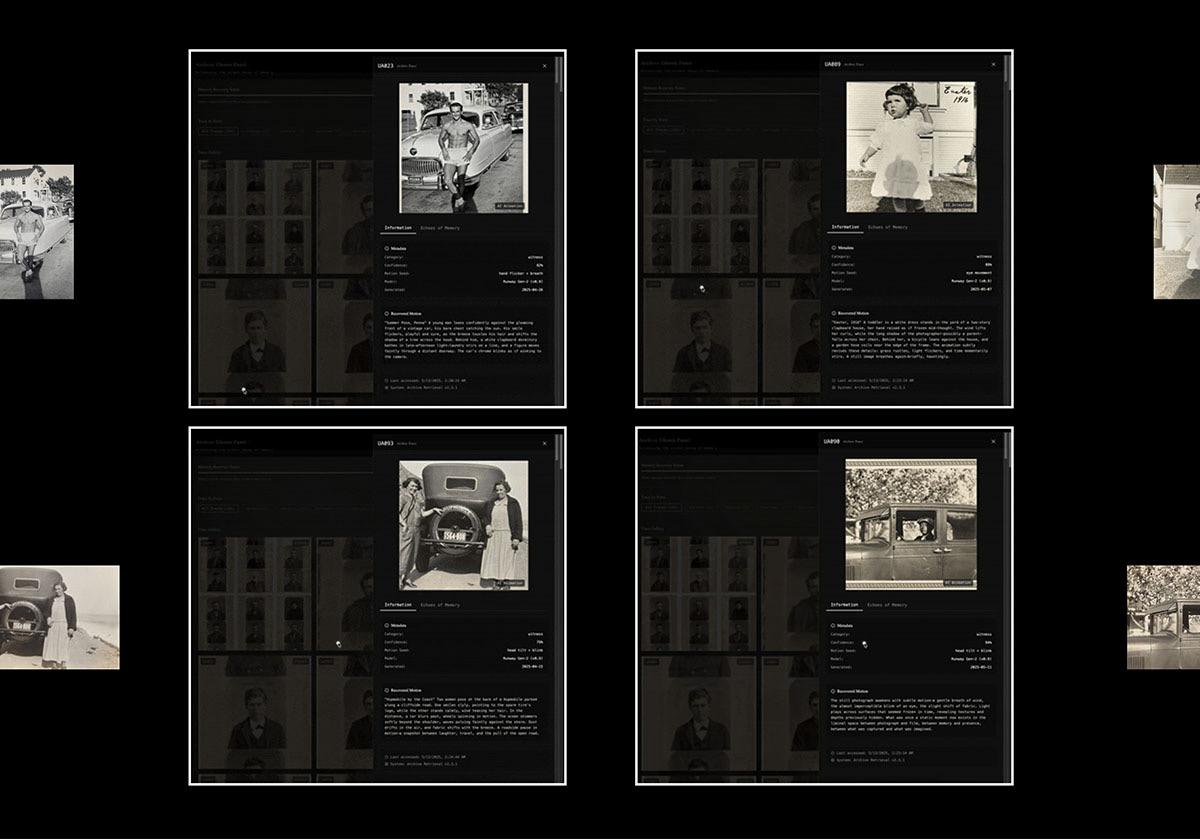

Over the course of this semester, I found myself wandering through archives not as static containers of knowledge, but as living, breathing systems—fragile, fractured, and full of unresolved echoes. Each institutional encounter led me deeper into the tensions between visibility and erasure, memory and mediation. I became increasingly drawn to what sits at the margins: the overlooked blueprint, the misfiled photograph, the unnamed artist whose work remains suspended in a system that never bothered to ask.

This journey taught me to read not for information, but for absence—to treat glitches as annotations, and silence as evidence. Working with AI was not about automation, but about generating friction: between what machines can interpret and what they inevitably distort. Through this process, I began to understand design not only as form-making, but as an ethical act of re-encountering forgotten lives.

Silent Signature emerged from this space of longing and hesitation. It became a way to rehearse care for what can’t be recovered, and to imagine an archive not as a vault, but as a séance—where meaning flickers, misreads, and finally, moves us.

Shiman broke every rule of curating, and did it so beautifully that we gasped as a group when she presented her project. Her AI companion endlessly stirs the pot of unidentified authors and presents an authoritative hallucination that’s painful and haunting and hard to look away from. We know that each of the objects she gathers are authorless, subjectless, and out of time, and yet they’re presented with the total confidence and assurance that we’re used to when looking at a museum’s collection. The resulting work is deeply flawed, deeply problematic, deeply human.

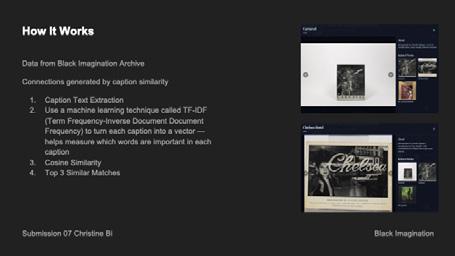

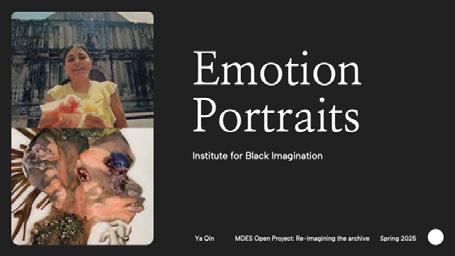

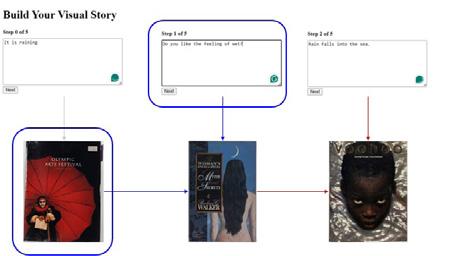

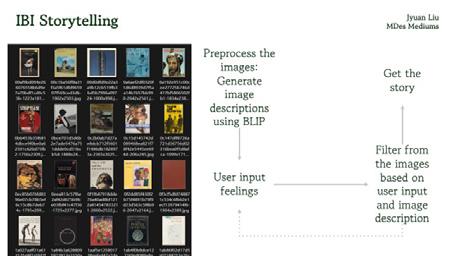

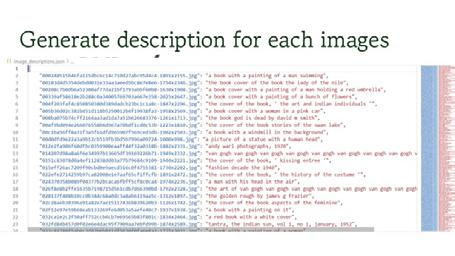

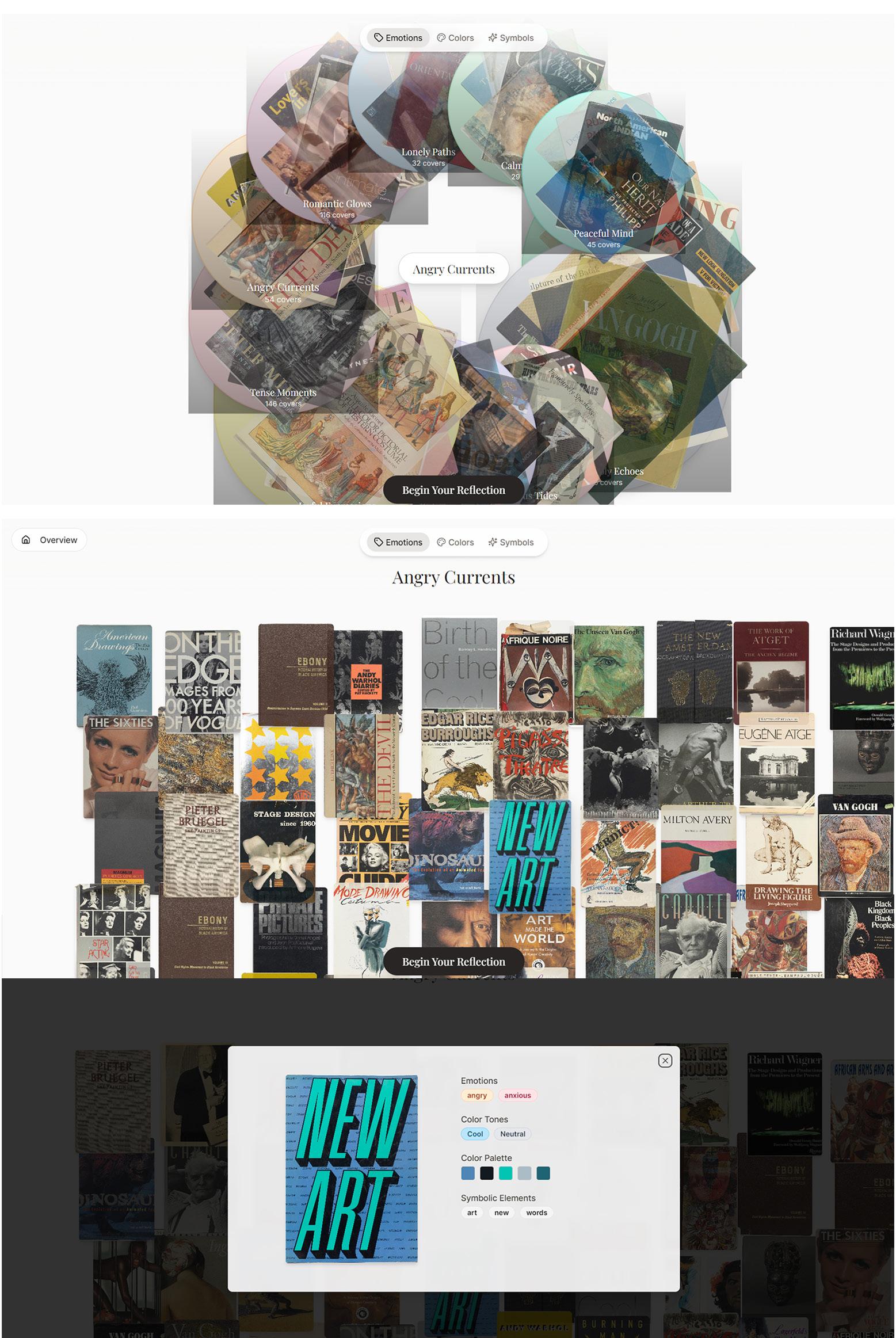

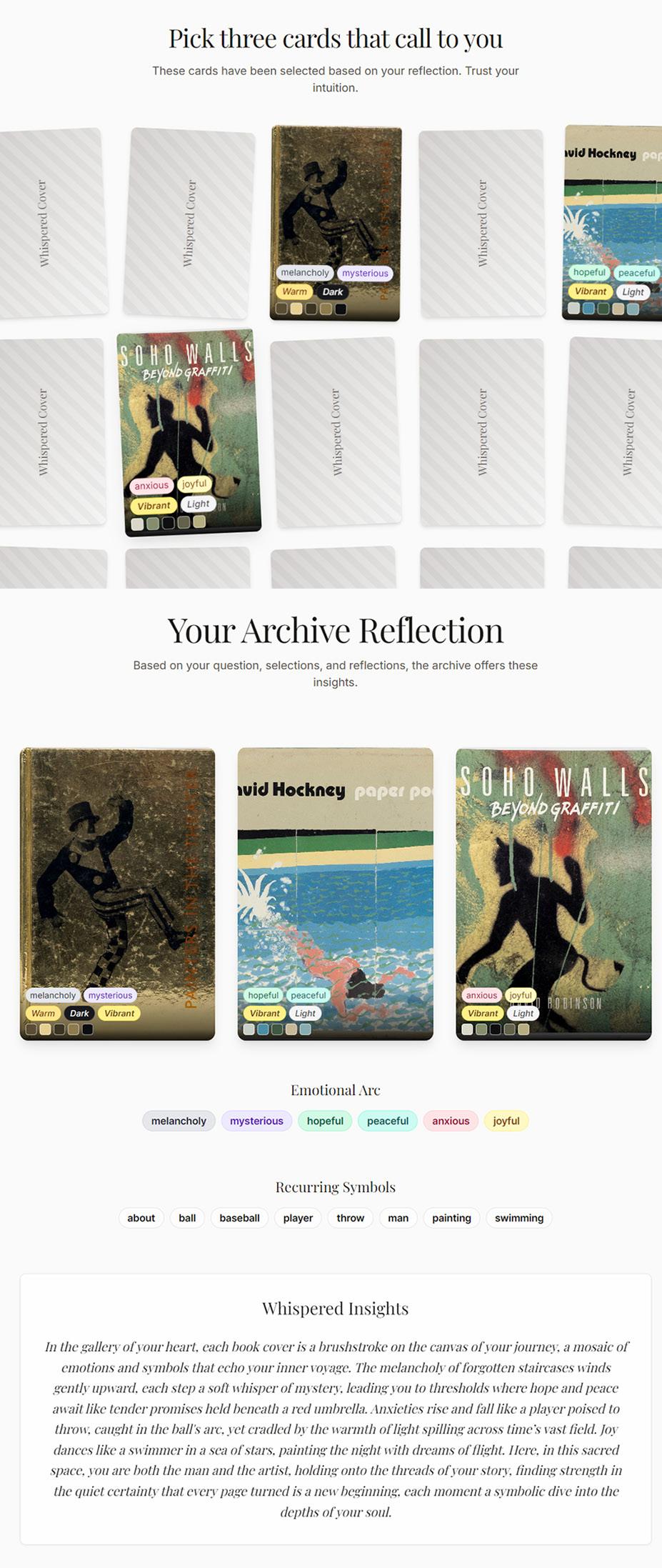

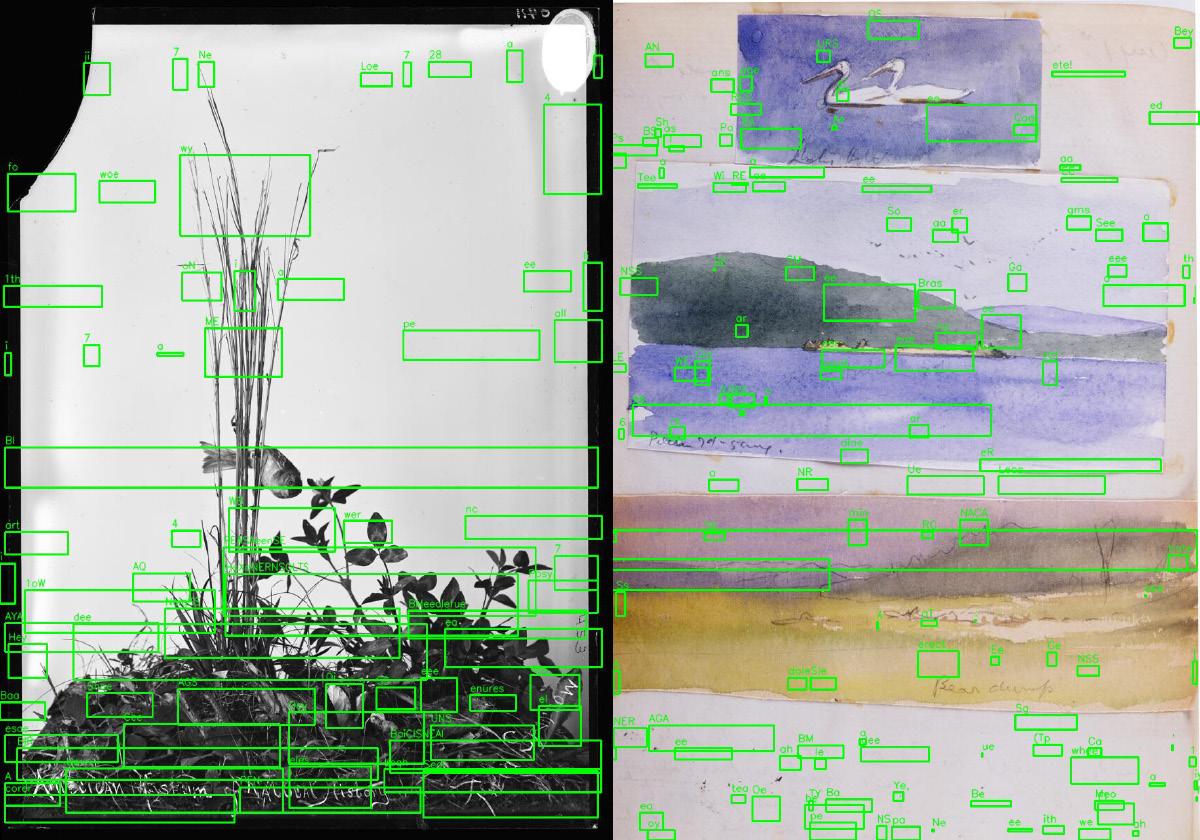

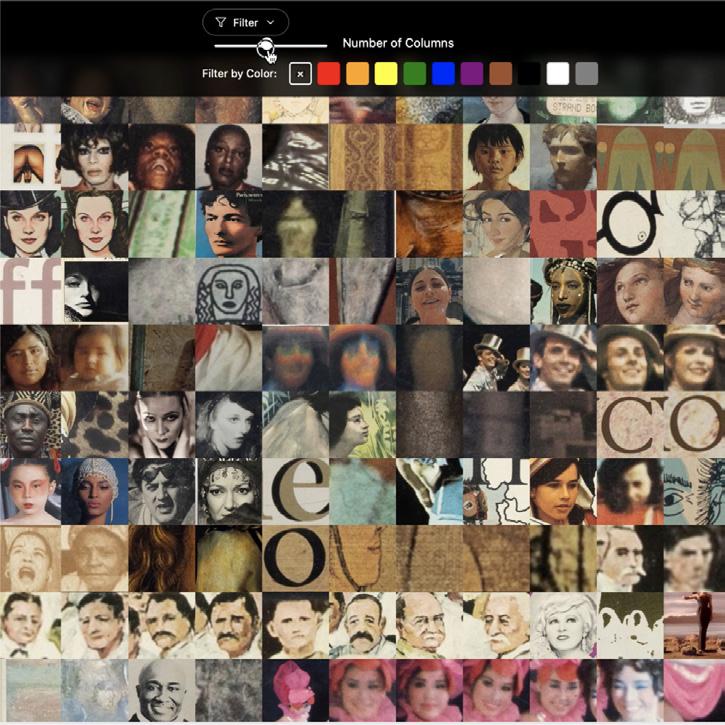

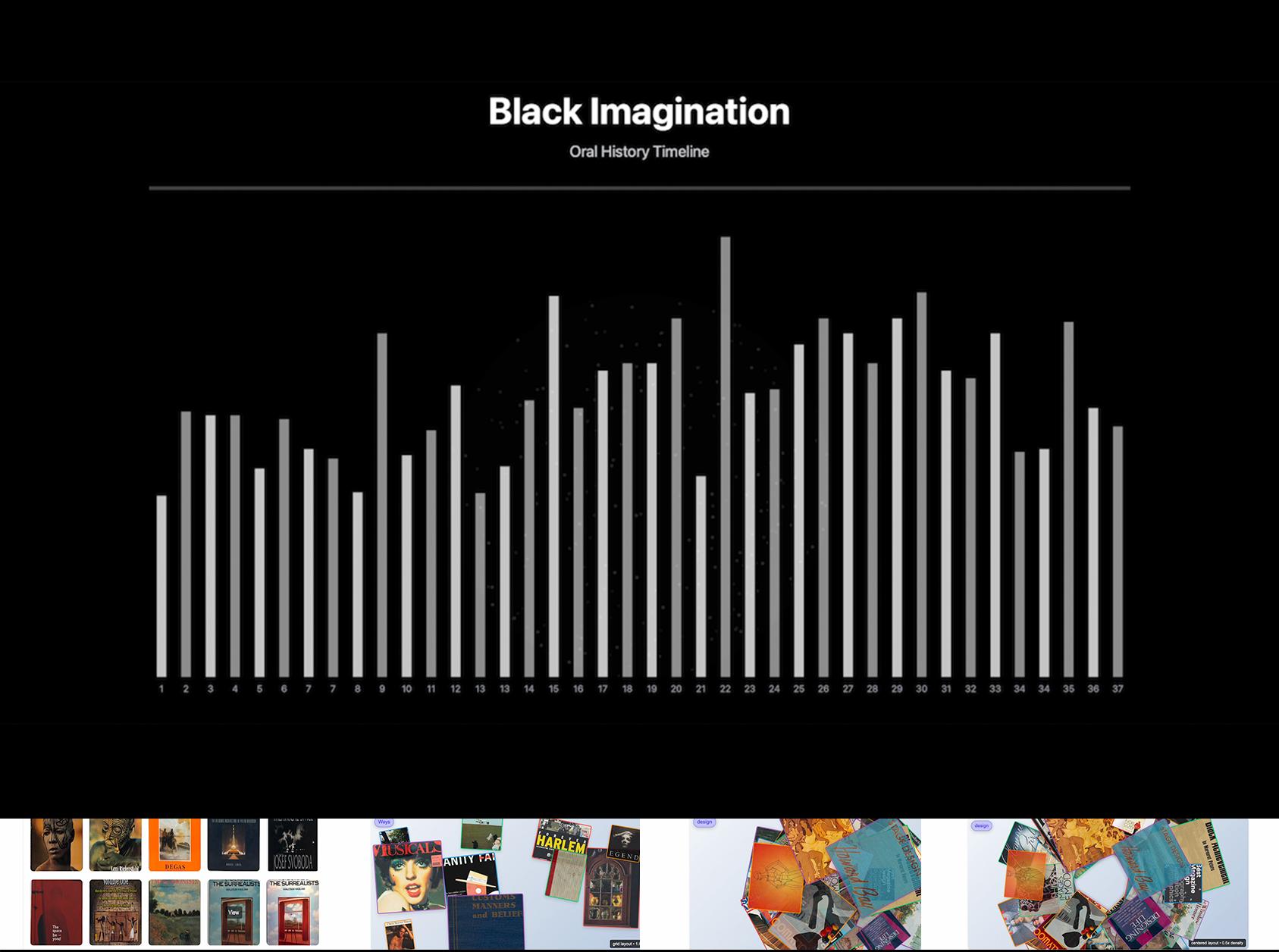

This semester, I explored new ways of visualizing museum archives, experimenting with different technologies and interaction methods. Through a process of iteration and discovery, I developed my final project: Whispered Covers, an interactive experience built on the Institute of Black Imagination Archive—a collection of 2,000 book covers that capture the depth of Black creative expression across time and space. Rather than treating these covers as static objects, the project invites users to explore them as emotional and symbolic portals. Visitors are encouraged to ask personal questions, select covers intuitively, and reflect on the emotions or meanings these images evoke. The archive becomes a mirror—reflecting not only the legacy it holds but also the thoughts and feelings the viewer brings to it.

This journey has led me to reconsider what archives can be. Beyond documentation, they hold potential as living, emotional landscapes. Data visualization, I’ve come to realize, is not just about clarity—it can also foster intimacy, storytelling, and self-reflection.

Jyuan excitedly treated book covers in IBI’s collection like cards in a tarot deck. Obsessive analyses of multiple aspects of each cover; not only faces but emotional resonance, staying power and so on. Each of these was collated into a multi-dimensional LLM that grouped covers into “hands” in a way that made us consider and reconsider the many different groupings, human- and otherwise-constructed, that collections can offer up meaning.

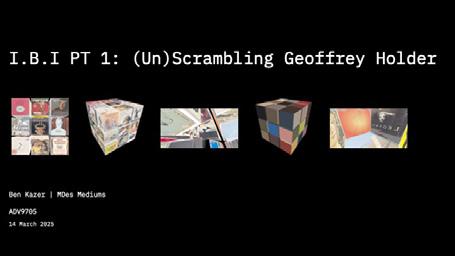

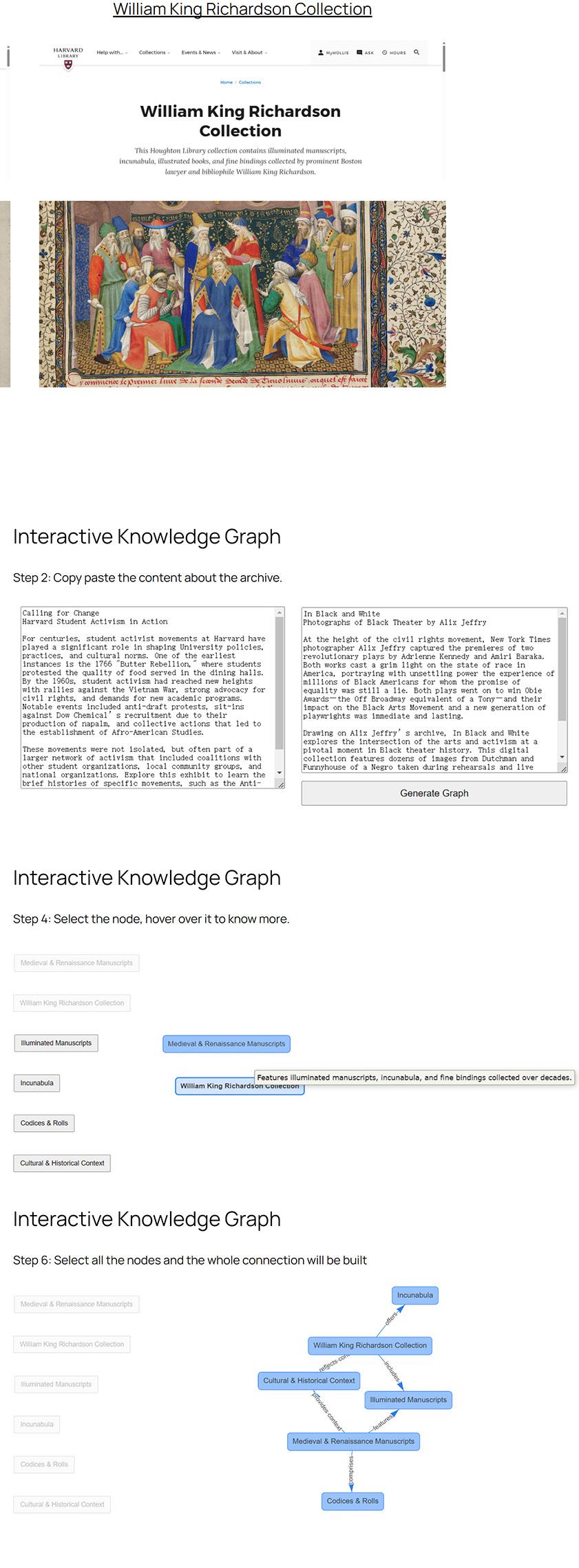

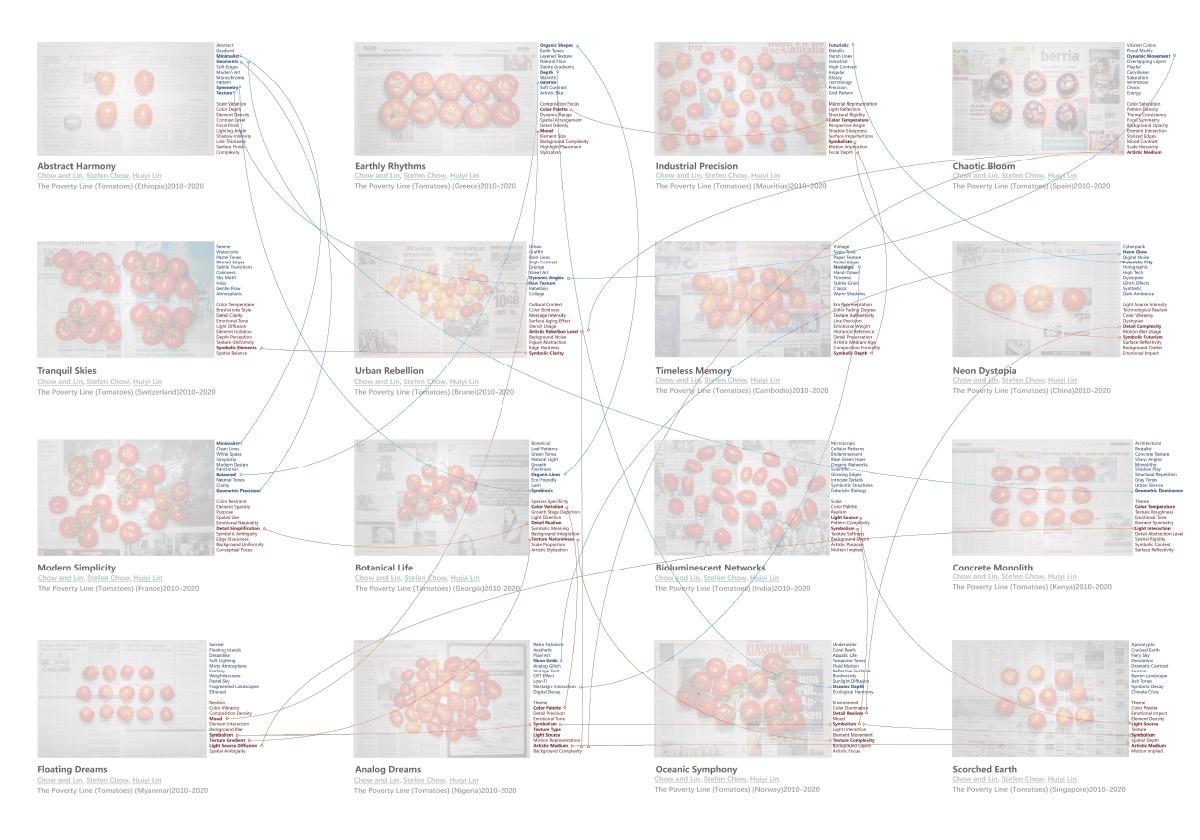

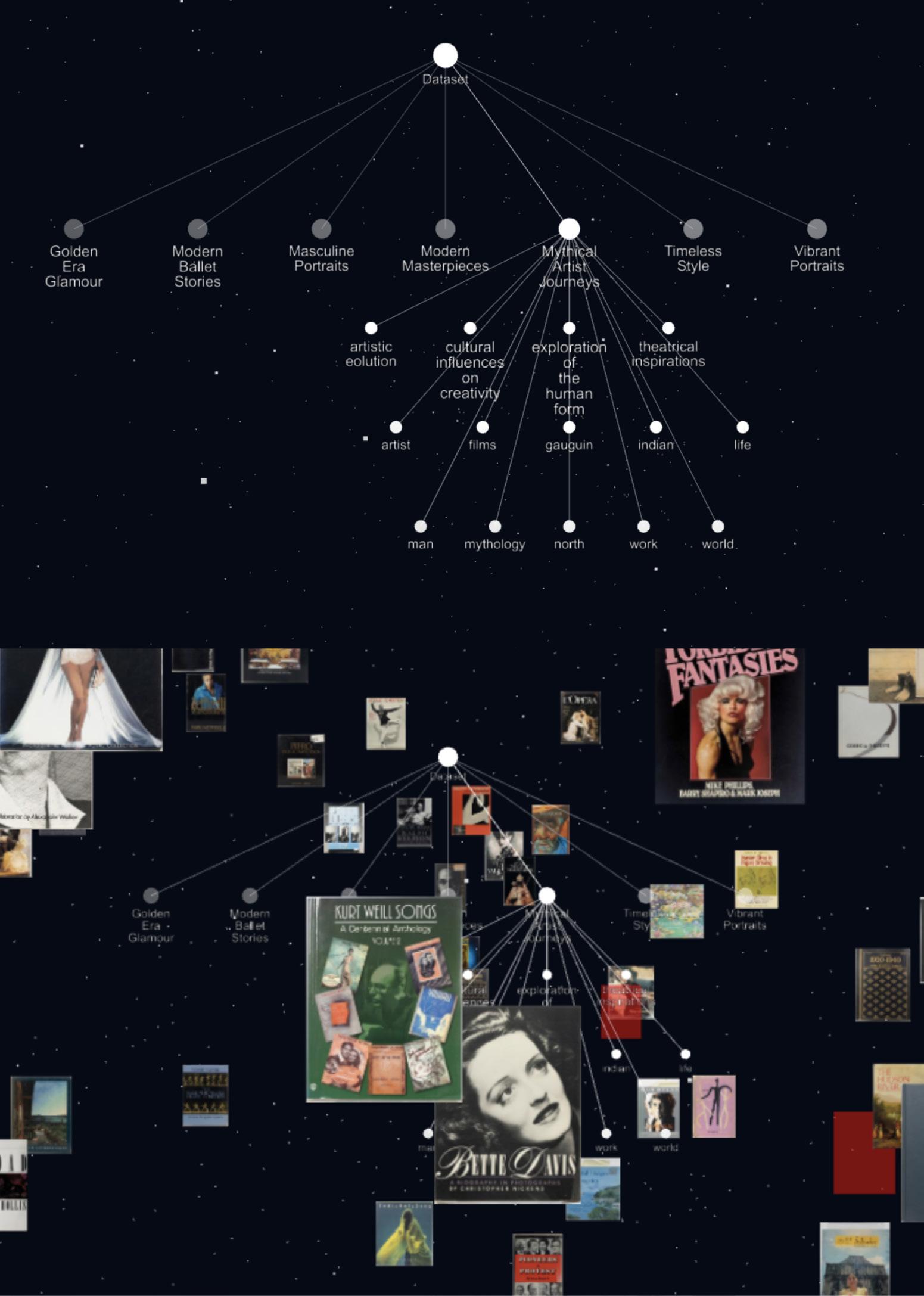

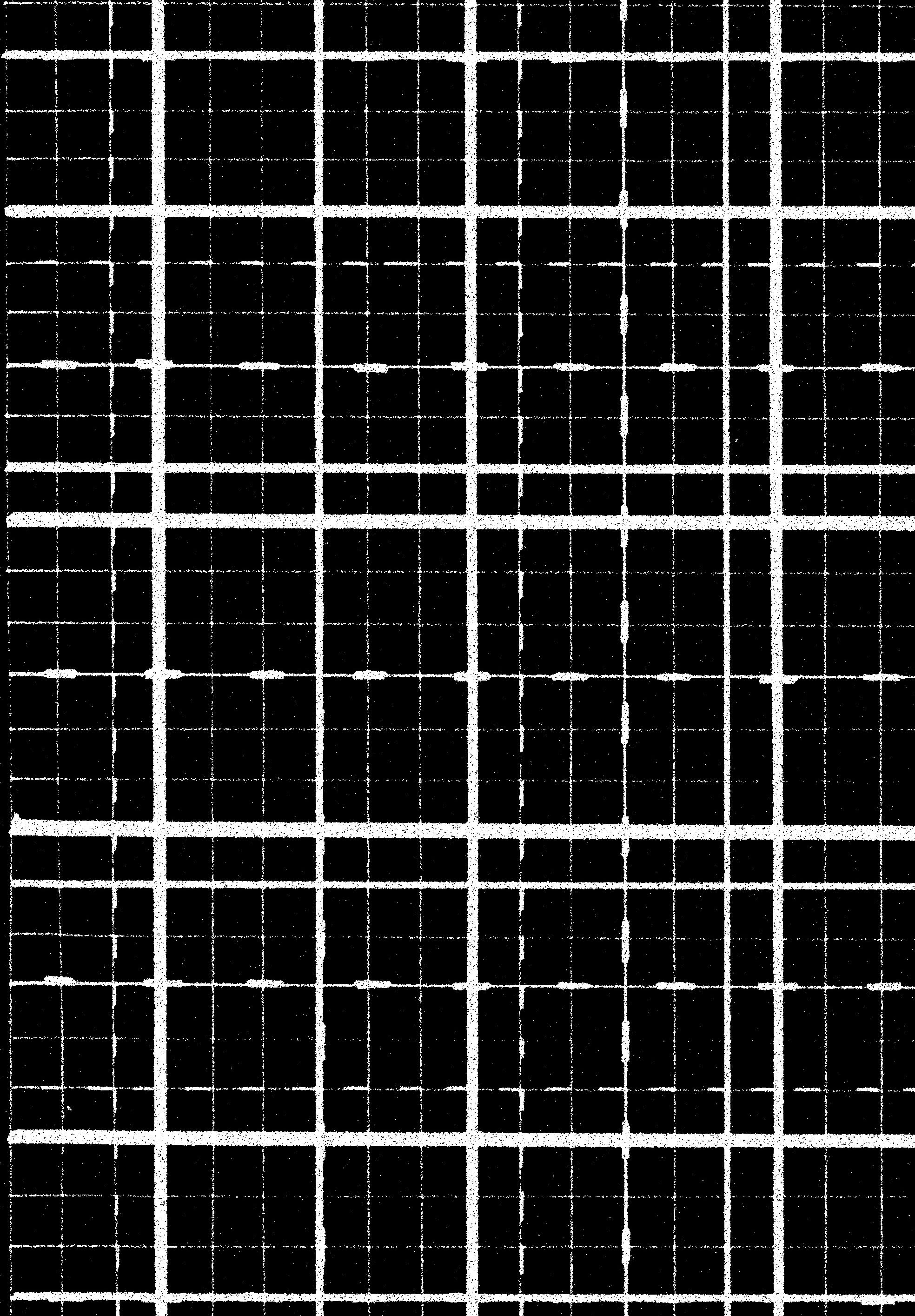

Over the course of the semester, my work has focused on critically examining how artificial intelligence perceives, interprets, and reorganizes visual, textual, and archival materials and how it differentiates from human thinking. Using museum and photographic collections as a foundation, I investigated the tension between machine-generated logic and human understanding.

Through a series of experiments with AI-generated keywords, titles, and compositional readings, I attempted to explore how technology distinguishes between similarity and difference, accuracy and error. By feeding [usually] untitled images, texts, and contemporary photographs into AI systems, I analyzed how visual data is translated into distinct languages— sometimes insightfully erroneous. These misreadings became productive sites of inquiries, revealing the underlying mechanics of computational perception and raising broader questions about authorship, curation, and interpretive control we must take in order to approach archival materials.

My goal throughout was not only to uncover how AI “sees,” but to use those insights to propose new methodologies for engaging with collections: whether through reclassification, collage, or interactive tools. Ultimately, my semester’s work aimed to position artificial intelligence not as a neutral observer but as a generative, sometimes fallible partner in the ongoing task of reading, organizing, and reimagining cultural artifacts. This approach offers new pathways for curatorial research, digital interpretation, and the future of visual knowledge production.

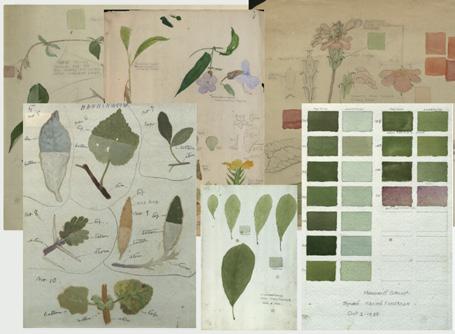

Roy conducted consistently weird investigations of what AI responses to repeated queries would be. By comparing queries to follow-on, identically-worded queries, he was able to reveal patterns in how these queries came back over time. He helped us visualize and understand that the answers that come back from questions to AIs are situated in a way we would never have been able to articulate without his research. By using repetition as a tool: ask, ask again, ask again: he showed us that all our interactions with AI take place within a linguistic and temporal continuum that can be charted, mapped, interrogated, investigated and critiqued. His use of optical character recognition techniques revealed hidden textual patterns in pictures of plants & drawings of landscapes, and his archival collage maker pointed a path to automated drawing that made museum archives seem like playful landscapes for discovery.

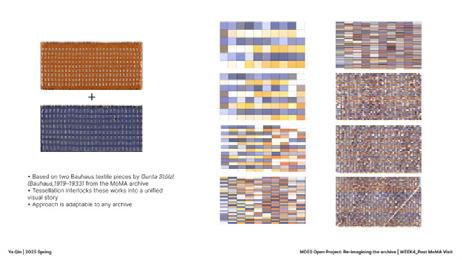

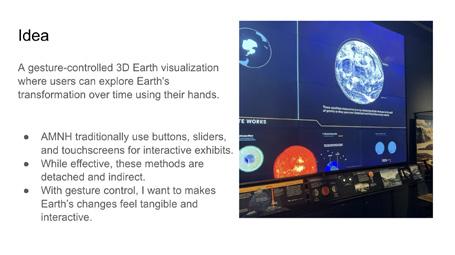

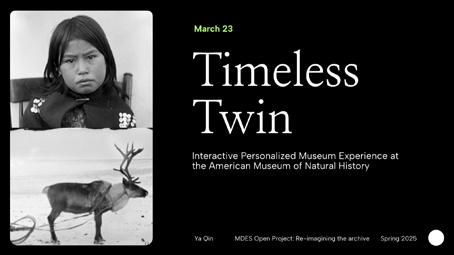

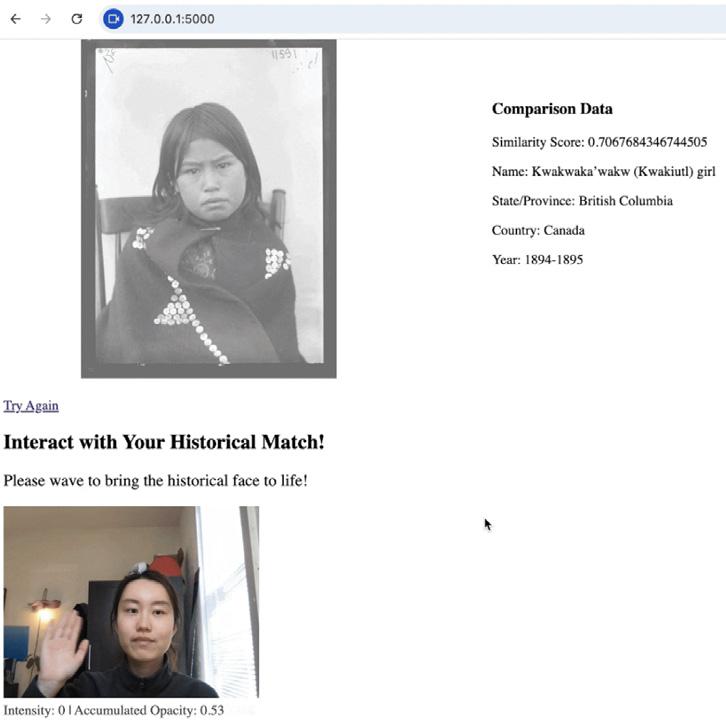

This semester’s journey has flowed like several creeks, each exploring a different archive, eventually gathering into a cohesive and larger stream. Understanding the purpose and content of each archive, hearing the true stories behind the material, and connecting people to it in a genuine and engaging way have been the starting points for every project. Through a growing familiarity with digital archival formats and creative coding, Ya has grounded each exploration in curiosity and care.

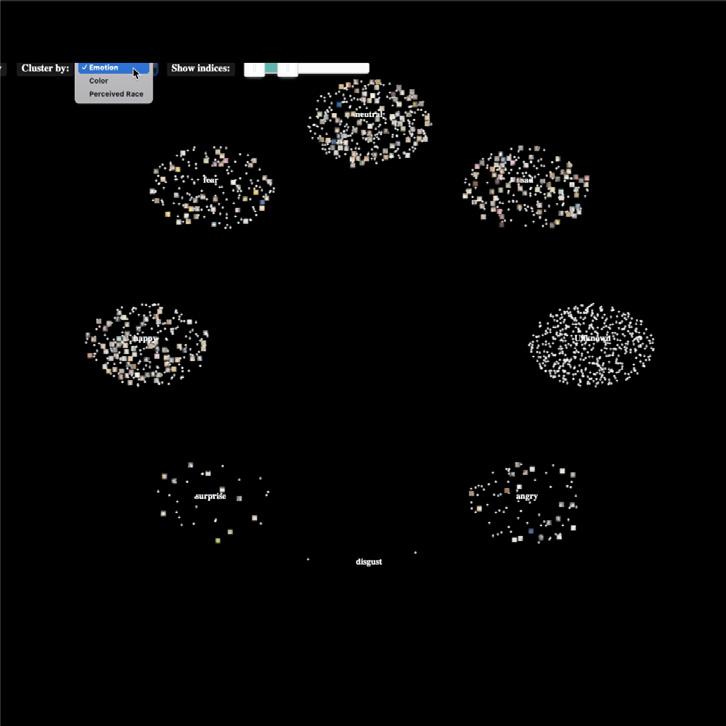

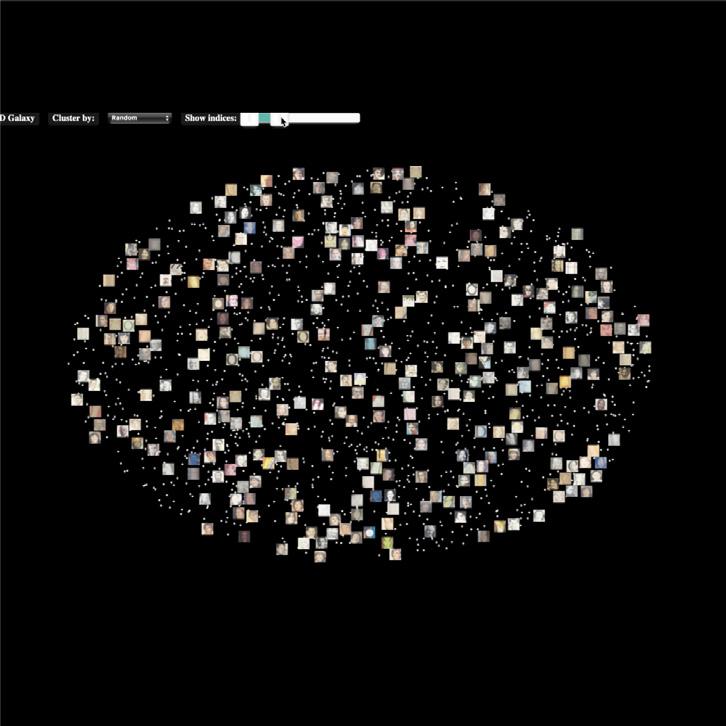

Ya’s approach and the form of presenting ideas have evolved from developing early concept sketches to building fully functioning website iterations each week. While adapting to the fast pace of AI-aided creative coding, Ya’s work has remained centered on people—those represented in the archives and those engaging with them. Whether recreating MoMA’s textile collection using generative design tools to enhance spatial experience, using machine learning and Python to allow people to interact with their timeless twin from the AMNH portrait archive, or building a constellation of stories from the Institute of Black Imagination using Three.js, each project seeks to bridge data with human experience.

Instructor Commentary

Ya focused on faces, creating poignant collections within the collections we worked with. She inadvertently made an interface to find book covers with more than one person featured on them, a delightful and serendipitous discovery. She used her own face as a tool for browsing historical archives! And ended with a galaxy of stories that hung together in multiple configurations across time, space, and color.

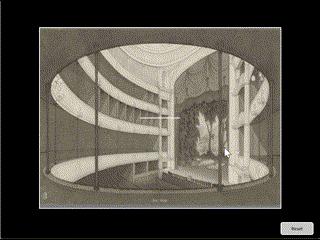

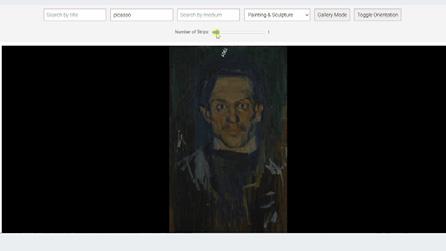

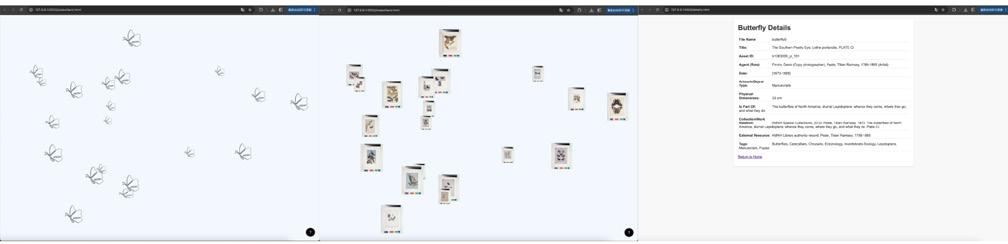

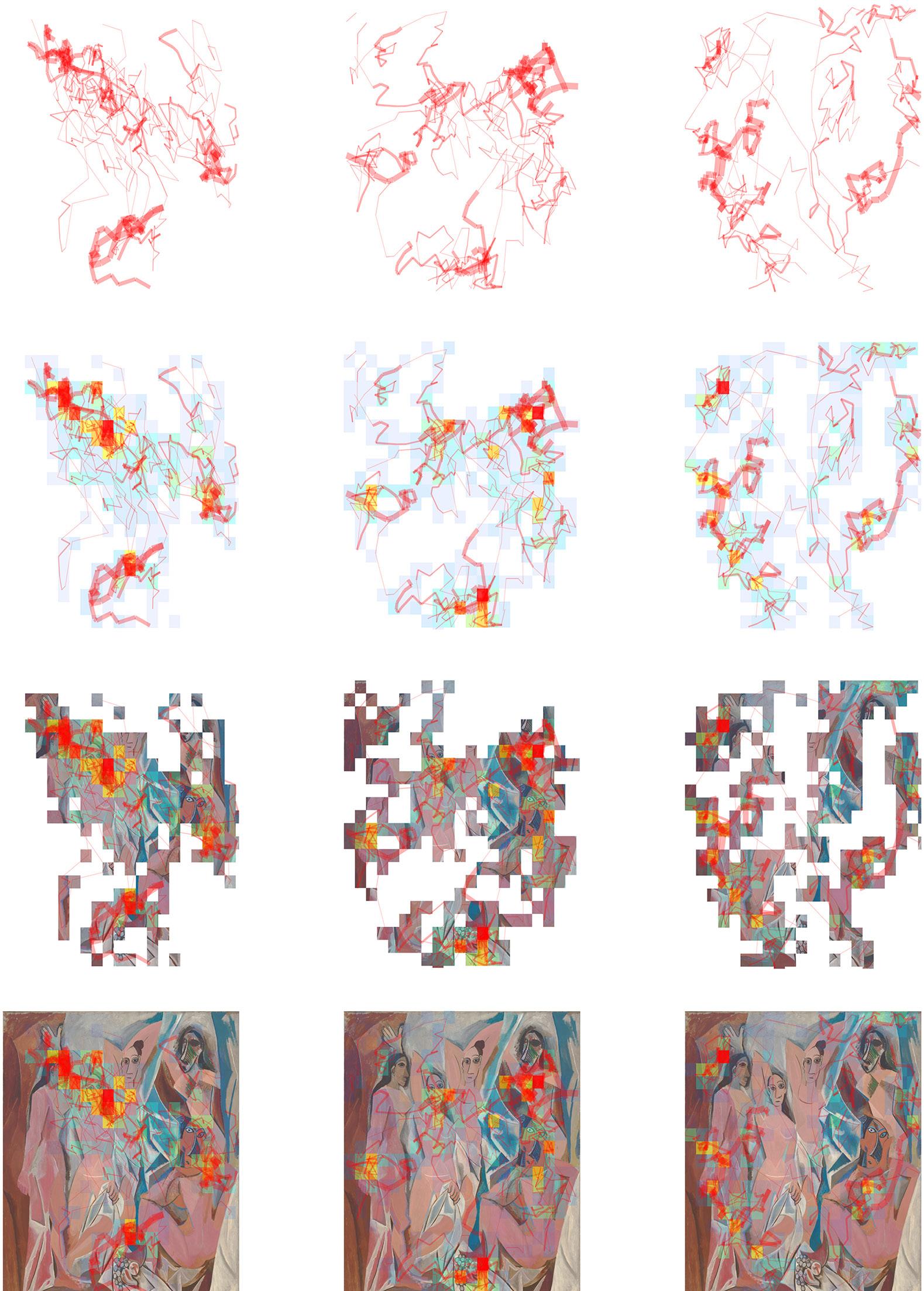

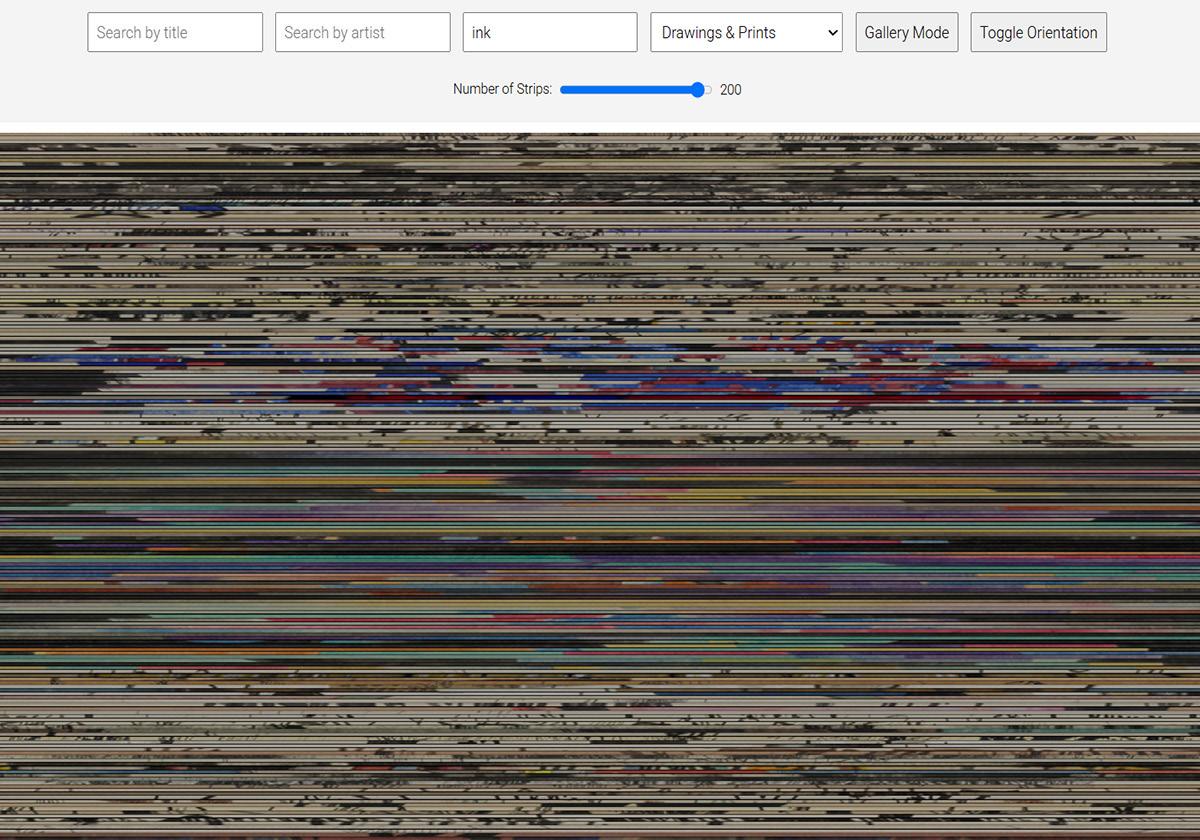

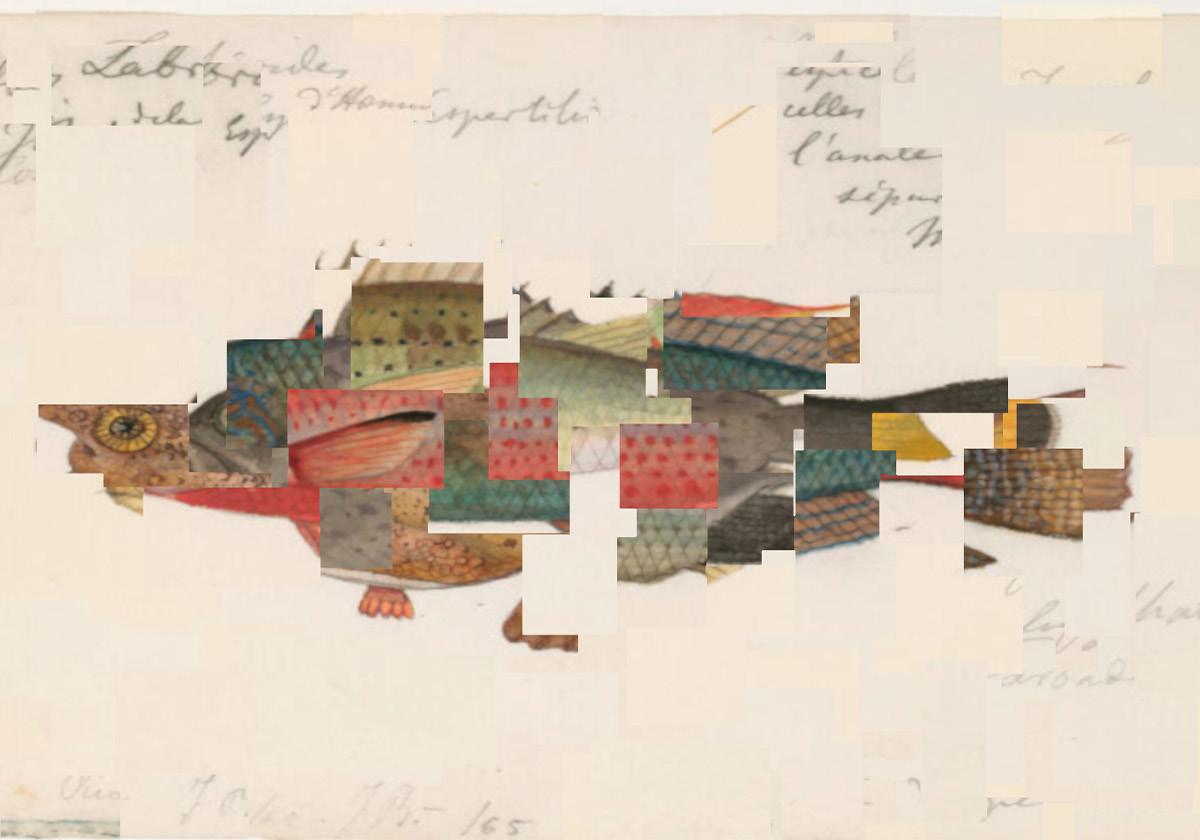

I came into this course having never worked with archives or information visualization, so every project was a leap of faith. Throughout the semester, I became driven by an inquiry into how we see, and how visual perception might inform the way we engage with an archive. I was primarily drawn to the representation of archival images, and conducted a range of experiments at various scales. Whether it be the synthesis of hundreds of images at once, or more intimate examination of a single image, my work attempted to add new layers of visual meaning onto existing archival material. My projects tended to be tools rather than artifacts. These tools are capable of extracting information both from the viewer of the archive, and the archive itself. They also enable art-making as a form of archiving, where new artworks emerge from our subjective interpretations and interactions with an archive.

Technologies JavaScript, Python, Processing, p5.js, three.js, node.js, D3. js, WebGazer.js, Google Cloud Platform, Rowboat, Adobe Photoshop, Adobe Illustrator, ChatGPT

Ben started out with a kind of kaleidoscoping chopping block, remixing drawings of fish and buttons. He showed us that some archives have a kind of shape that pervades their holdings, that this shape can be thought of as a kind of meta-form that persists across many objects in the collection, and that this shape varies across catalogs & categories. He ended with a speculative kind of metadata, tracks of the eyes of people looking at paintings in MoMA. In Ben’s hypothesized world, these records of attention would take their place alongside other forms of provenance in an archive.

Bottom: Simulating selective attention and perspective.

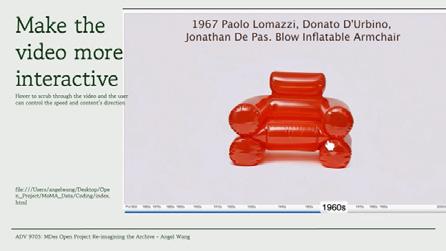

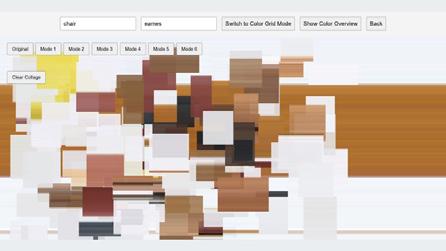

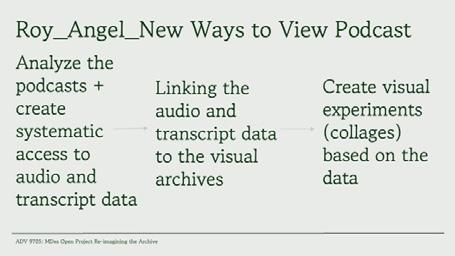

Over the course of the semester, Yining (Angel) Wang explored the intersections of archival media, AI tools, and experimental storytelling—shifting from initial hesitation with technology to a more adaptive, hybrid practice. Her projects, including Rotating Chairs, Coloring Absence, Cover Collage from Podcast (in collaboration with Roy Zhang), and Diorama. exe (in collaboration with Christine Bi and Roy Zhang), investigated how narratives evolve across time, format, and audience interaction. Whether using Runway to animate MoMA’s chair archive, generative AI to restore color to AMNH’s overlooked field photographs, or creative coding to visualize a podcast’s rhythm and memory, Wang consistently challenged institutional boundaries of access and perception. Through a balance of hands-on research, video editing, and AI-generated visuals, she reframed static archives as living, responsive systems. What emerged was not just a series of outcomes, but a deeper understanding of how story, interface, and cultural memory can be activated—and how digital tools, when thoughtfully engaged, can be shaped into intimate, critical, and poetic forms of expression.

Instructor Commentary

Angel took MoMA’s collection and turned it into movies that showed us the fluidity and continuity of curatorial practice. Like Ben Kazer’s work, these forms took advantage of the visual continuity between objects in an archive, in this case chairs, and hung them together like beads on a chain. She remixed drawings of insects in dizzying ways and collaborated with Roy and Yuanquing to re-imagine IBI’s podcast archives into something new and deeply strange.

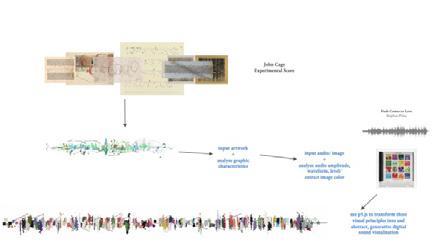

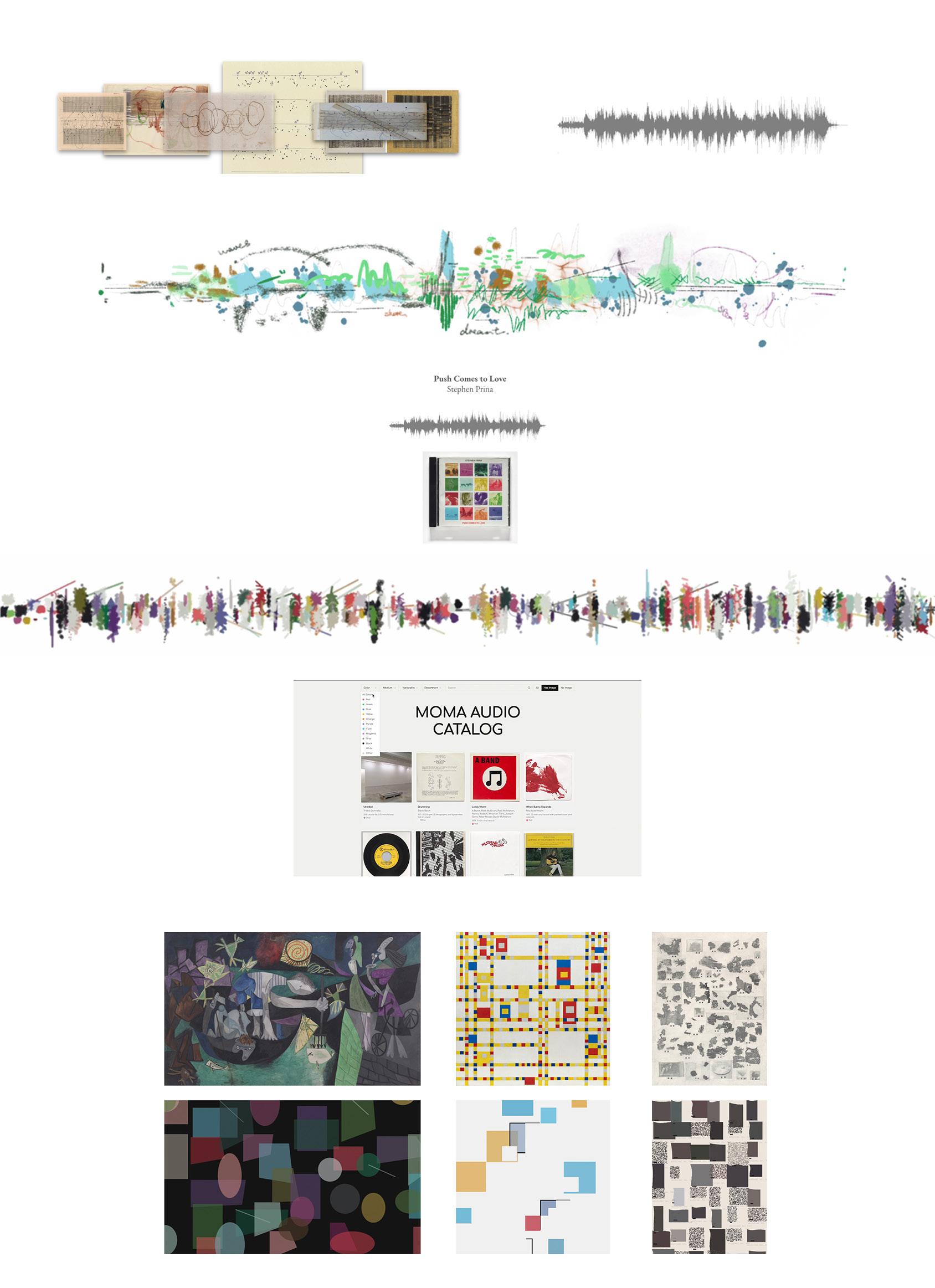

Over the course of this semester, I’ve explored the transformative potential of AI, coding, and web-based interfaces in reshaping how we engage with archives. From the Institute of Black Imagination’s podcast to the Audio Category of MoMA and visual materials from the American Museum of Natural History, each project challenged traditional notions of static archival access. I focused on building systems that allow audiences to interact with materials thematically, rather than linearly—using tools like keyword detection, AI-generated summaries, and generative visual layers. The use of web technologies became essential: not just as a display platform, but as connective tissue that enabled real-time collaboration, searchability, and fluidity. AI acted less as a creator and more as a provocateur—surfacing patterns, sparking new inquiries, and highlighting forgotten voices. Coding became the medium through which these relationships could be visualized and performed. This journey made me rethink the archive as a living system, one that learns, responds, and evolves with its users.

Instructor Commentary

Yuanquing gave visual shape to the recordings in MoMA’s collections, making tools that rode the line between analysis and poetry. Seeking forms that would evoke or correspond or echo, her software gave us a window into how a synesthete might approach these reimaginings. She ended by collaborating with Roy and Angel on IBI’s synthetic narrator project, which pointed at a new kind of listening that surprised us all.

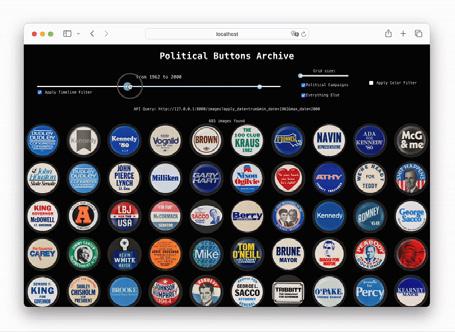

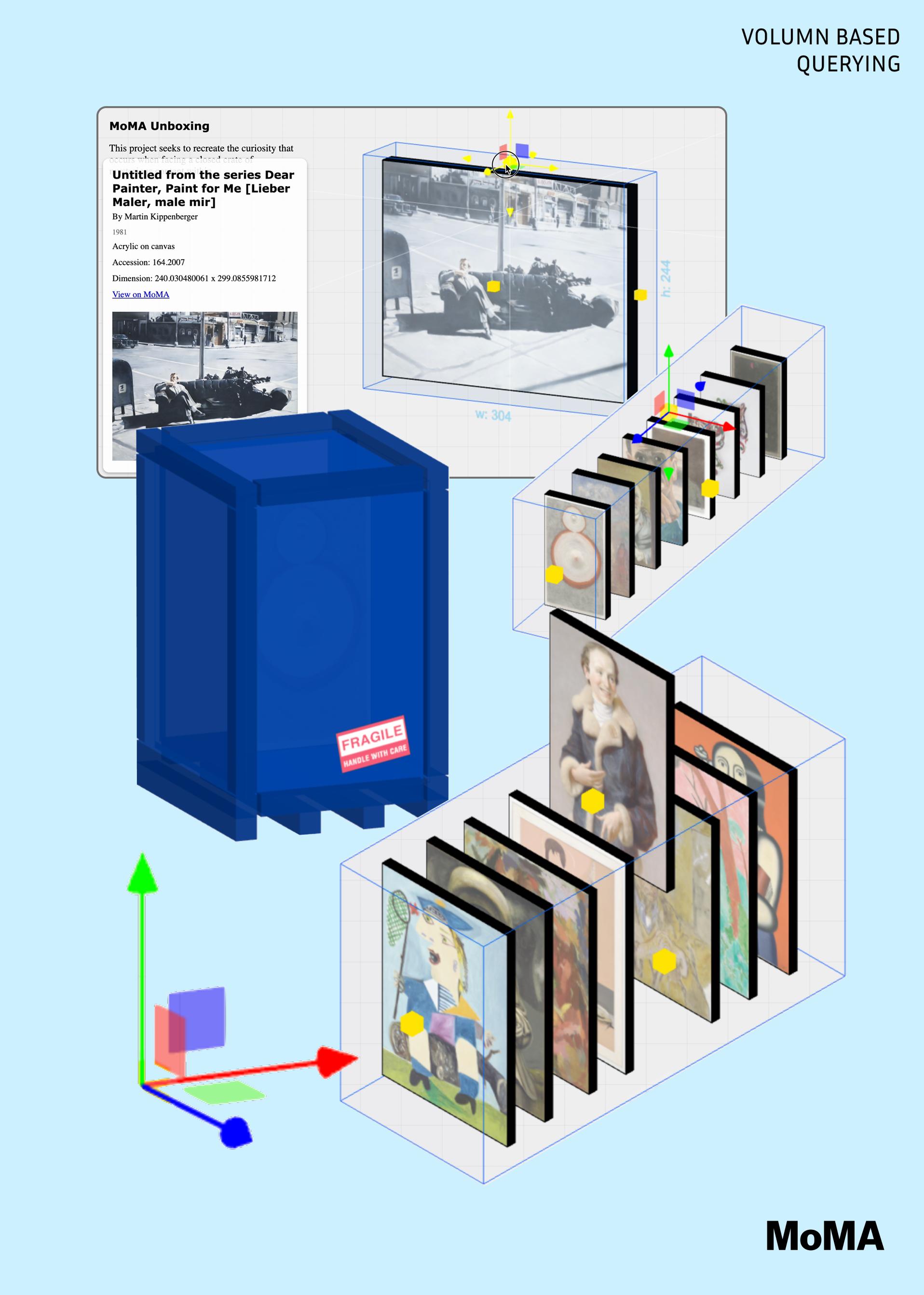

This semester, I used the weekly assignments as a way to explore different methods of processing and activating archives. Rather than highlighting individual items, I focused on surfacing patterns and relationships across the archive as a whole—leveraging efficient code and the scale of metadata to drive visual and interactive insights. Early projects like the Political Button and MoMA Unboxing experiments emphasized playful querying and visualization, but my final project, SPACE002, pushed further—toward synthesis. I realized that the true power of an interactive archive lies in how the metadata is structured: labeling, chunking, and encoding relationships fundamentally shape the narrative that emerges. My work evolved from designing visual queries to designing meaning. I became more interested in how AI could support this process—not as a tool for creation, but for intelligent preprocessing and augmentation. To me, AI’s role in archival practice isn’t about generating new content, but about accelerating the human ability to make sense of what already exists. It should remain a sense-making layer, not a creative one—preserving the integrity of the archive while enabling new forms of access and insight.

Kevin had, before our class, perhaps the most experience of any of us in coding, collating and deploying web-based applications. He came storming out of the gate with early prototypes for analyzing political buttons by color, size and text content, while the rest of us were just getting used to the idea of what it meant to access and think about an archive. His volume-based querying of MoMA’s collections let us browse through their holdings not by semantic or authorial constraints, but by size. It was a radical move that suggested multiple ways of collation and sorting that none of us had considered, let alone executed. When he and Yuanquing started chopping IBI’s podcast archives into semantically-organized sentence structures and using AI to stand in as interlocutor to conversations about alienation, impostor syndrome and blackness, I knew we had something special. In the end they built a fully-functioning app that pointed towards a radical re-imagining of what conversation could be on the internet, freaking me out in the process.

Kristine Grieve

Head of Teaching & Learning for Archives & Special Collections, Harvard University Archives and Houghton Library

Paul Galloway Senior Collection Specialist, The Museum of Modern Art

Michelle Jackson-Beckett Curator of Rare Books, Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian

Iris Lee

Cataloging & Metadata Librarian, American Museum of Natural History

Dario Calmese Director, Institute for Black Imagination

Ben Fry Lecturer, MIT Founder and Principal, Fathom Information Design

Josh Draper Lecturer, Center for Architecture Science and Ecology at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI)

Andrea Lipps Curator and Founding Head, Digital Curatorial Department Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

Emily Pugh

Principal Research Specialist, Getty Research Institute

Nikki Rodenbeck Hugo Rodenbeck

Re-imagining the Archive Instructors

Eric Rodenbeck Report Design

Eric Rannestad Report Editor

Eric Rannestad

Dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture

Sarah Whiting Chair of the Department of Design Studies

Charles Waldheim K. Michael Hays

Copyright © 2025 President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without prior written permission from the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

Image Credits

Cover Image: Eric Rodenbeck All other text and images © 2025 by their authors.

The editors have attempted to acknowledge all sources of images used and apologize for any errors or omissions.

Harvard University Graduate School of Design

48 Quincy Street Cambridge, MA 02138

gsd.harvard.edu