Published 2023

All rights reserved © Mimi Kuttelwascherová

Published 2023

All rights reserved © Mimi Kuttelwascherová

COMMEMORATING CIVILIANS KILLED POST THE YALTA CONFERENCE

by MIMI KUTTELWASCHEROVÁ

While housebound during the CV19 pandemic I opened old family albums and cardboard boxes. Fragile records ing back a century. Sepia prints of ancestors and their compatriots floated into my London life. morphed into a scribe to record their lives in Brothers in Arms and Man of Few Words

Like countless millions, I and my direct family became refugees. We sought sanctuary twice: first under Hitler, the second time under Stalin.

Unexpectedly, these two narratives coincided with a project at the London Czech Embassy: Children of Heroes – remembering the lives of those that came to the UK to join the Allied Forces and fight Hitler when territorial integrity was lost in Europe.

Polish and Czechoslovak men and women, who remained on guard, withstood the fear, depravations and hardships of war for many years. In the skies above France and the English Channel they excelled in airmanship, honed in battles not witnessed by home grown pilots. While on the ground, as infantry or tank crew, they slowed the enemy’s progress.

After a few weeks of my comfortable isolation, I went out on my first walk.

Very nearby I found a memorial dedicated to people displaced and those killed as a direct result of the Yalta conference at the conclusion of World War II.

I squatted on my haunches and through the mosscovered stone I read and reread the inscription.

The nearby traffic lights blithely flashed their Red, Amber and Green lights to empty roads.

The central stone plinth has a cluster of tightly grouped heads: men, women and children gazing outwards. At the base four metal supports make a cross like the main points of a compass.

A police car slowed up alongside me, “Please keep moving ma’ am.”

“I can’t my knees are locked. Give me a few minutes?”

“Sorry, we cannot help you as it is strictly no contact.”

“I’ll just take another minute.”

I walked round the brick plinth several times. An urban seagull perched itself on the sculptured heads then flopped down to the bins searching for scraps. Clearly birds stop here for comfort breaks. In an ice-clear blue sky the cupola of the Victoria and Albert Museum was silhouetted above me.

Not very long ago those skies had fighters battling for my freedom today. My uncle was one of those Czech pilots facing the invaders. My father was fighting from a tank somewhere in the middle of France. Having lost sight in one eye from a nearby bomb blast the accuracy of his aim at targets was commented upon by his commanding officer:

“Good ambition, quick witted, hard-working, sociable, looks after his appearance, disciplined, reliable, energetic, proactive, carries out orders with precision, interested in Military service, good military knowledge. Did very well in attack and reconnaissance. Took wartime hardship very well.”

I strolled round the memorial: Twelve Responses to Tragedy Angela Conner. These twelve bronze heads were my people. The females were like me. The men with distinctly Slav faces were my countrymen and our good neighbours. The small child’s head tucked between the adult heads was being shielded. The brutality these innocent victims endured after being displaced or forcibly repatriated after The Yalta Conference was remembered here, in this small triangular garden in the heart of London.

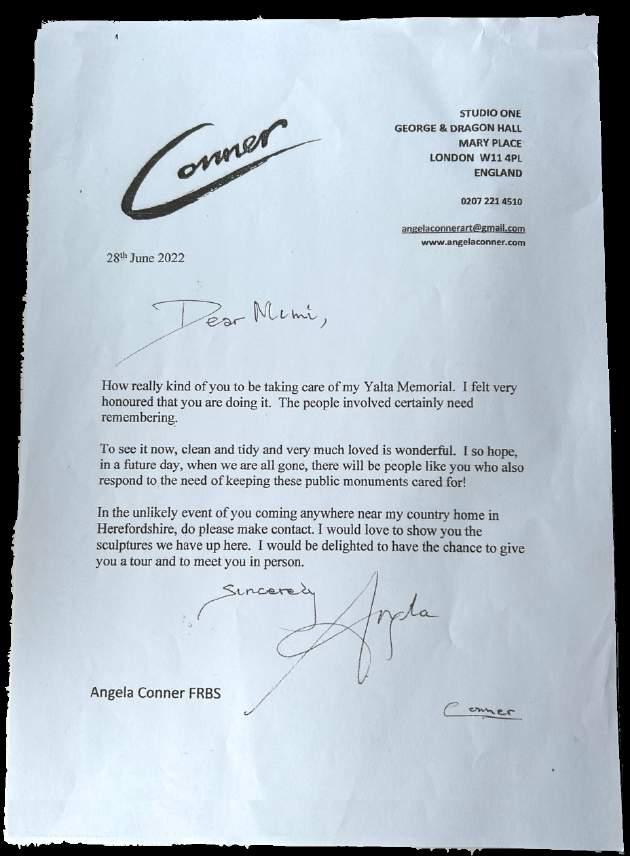

I resolved to bring a bucket of soapy water and clean the bronze heads and the inscriptions. I contacted Angela Conner the artist to ask her permission.

Political parties in both Houses of Parliament had joined together to commission a memorial to over two million men, women and children forcibly repatriated to Stalin’s control by our own wartime leaders. Many were executed on arrival in Russia and others sent to Gulags and left to die. In spite of some opposition demanding not to re-visit that past horror, a memorial was erected. In front of one of the great museums of the world it stands testament to the millions who died or lost their countries after negotiations by their own leaders.

The first memorial to that brutality was itself brutalised by people who could not stand the truth. The tilting water sculpture was irreparably damaged by vandals and the inscription smashed.

A picture of the original memorial arrived from the artist with kind permission to use it.

Over the decades it seemed to become less and less well known. In 2013 it was described as being in poor condition.

In 2018, it was recorded as Condition: Poor (updated on 22 Nov 2018).

Memories were possibly fading. I learned how few of my Eastern European friends knew it even existed.

I was now on a self-appointed mission to spotlight and elevate this haunting memorial to the victims who were not insignificant.

Europe had been ravaged during World War II. Millions died. Millions lost families. Millions were displaced. The leaders of Russia, the United Kingdom and the USA had worked together to destroy HITLER. They themselves had lost their own people in battles of unspeakable horror to regain stolen lands and freedo m for others in the fight for Democracy.

After that war was won the Big Three leaders gathered to discuss Europe. The USA and Great Britain were still in a bitter war in the Far East. Japan’s aggression occupying their neighbours’ countries was still being fought.

On 4 February 1945, the Victorious leaders assembled. Each party wanted the peace secured. The horse-trading would start at the former Royal Livadia Palace in Crimea near YALTA.

President Roosevelt was in very, very poor health.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill was anxious and alert.

First Secretary Josef Stalin was wily, determined and demanding.

Discussions began. Who had conquered where, how far, and where exactly were those old boundaries, having been wiped out during World War II. Under the watchful eyes of their own military personnel, lines were being drawn on maps of Central and Eastern Europe. Stalin’s demands were proving paramount. With his liberating armies still in those countries there was little scope for compromise beyond a vague promise by Stalin to give free elections.

Churchill and Roosevelt may have had hopes that Russia would join them in the Far East to crush Japan’s aggression. There was an atmosphere of not wanting to antagonise or upset Stalin. Russia’s military contribution to crushing Hitler had been crucial, albeit that it was started to counter Hitler’s catastrophic miscalculation to expand into Russian lands.

By 11th February several European borders were moved or altered with black and green lines (see back cover). ‘To the Victor went the spoils’ in Stalin’s favour. A month later, the words of Churchill sent a chill through the hearts of many.

“From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the Continent.”

The upshot, he went on to say, was that police governments ruled Eastern Europe. A month after that, Roosevelt the USA President died: 12 April 1945.

I was fully aware of the consequences of the YALTA meeting. That was why my father’s doctor injected me with a sedative one night. Hiding me in the back of a STUDEBAKER car, we were getting ready to escape. A journey that nearly didn’t happen After repeatedly and forcibly trying to close the car door he saw had flopped out of the opening. My hand and arm were a mess. I made no sound. To take me to a hospital would have meant a fatal delay. He decided to drive his young family through the night across Bohemia to the border several s away. From Karlovy Vary we drove to Velhartice to pass by the grandparents’ house to refuel, get more provisions and a short, tearful farewell. Then driving through the dark countryside to reach Regensburg in southeast Germany my father escaped for a second time and left everything behind, except his new young family.

Many that returned with false hopes to their homelands paid a heavy price. They were executed as traitors having fought with The West. Others, whose lives were regarded as insignificant, men, women and children were incarcerated for decades in Gulags across the Soviet Union. Those that escaped before the Iron Curtain descended were cast far and wide across the world. Many never spoke of their ordeal . Their descendants may remain unaware. The horse-trading at Yalta, with those black and green set in motion half a century of Cold War for millions on both sides of the Iron Curtain, dividing countries and families. The YALTA Memorial and garden is one way for them to connect with that sacrificed generation. Occasionally I meet somebody who shares their family story and then: On Thursday, 24 February 2022, in a major escalation that stunned the world, Russian Tanks further invaded parts of Ukraine with wanton and brutal killings of thousands of innocent victims. The V&A Museum raised a fluttering Ukrainian flag to show support.

Twelve Responses to Tragedy was starting to be bedecked with candles, sunflowers and ribbons in the colours of Ukraine. Like soft weapons, these tributes have their own strength when being visited and acknowledged. Passers-by stop to look, to read, to think: the cost of our freedom was paid by others. This current invasion by Russian forces trying to destroy the territorial integrity of a neighbour’s land is a ravaging beast from a past era.

The Yalta memorial garden is now added to the list of sites supported by descendants from the tragic struggles for freedom. Under the care of Mrs Gerry Manolas, the granddaughter of a Czechoslovak veteran and Mr George Scott, the son of a Czechoslovak veteran and resident Historian, the annual memorial service is held for the Czechoslovak veterans of World War II at BROOKWOOD CEMETERY, Surrey.

At Cholmondeley Castle, the 80th anniversary was twice delayed but resumed on 13/14 May 2022.

In the Castle chapel a Commemoration speech and readings by the Czech Ambassador H.E Marie Chataradova and Mrs Gerry Manolas.

“Before we complete our service here, I would like to share a short passage that was written by one of the soldiers stationed here for the Czechoslovak Army’s newspaper at that time. His nom de plume was Jiri Zora, and this piece explains his arrival at Cholmondeley and what it meant to him and his BROTHERS IN ARMS to be here.“

This soldier arrived in Liverpool during August 1940 ready to fight Hitler. His true name unknown, the piece was entitled Evening by Jiri Zora, and dated 8 August 1940.

Evening by Jiri Zora

A fast moving, completely darkened train, stopped at a small station in the middle of the woods, “Somewhere in England”. In front of the station, a stream of characters spills out and floods a wide area. Short, sharp commands, the dark rumble of footsteps and large coaches gradually take away the tired soldiers along the asphalt road winding through the woods, leading us to the entrance gates of Cholmondeley.

Beyond the canvases of the tents a fire blazes merrily by the kitchen. “Hello

The first days in the camp passed smoothly usually in bad weather and the camp life developed at a completely normal pace. These days I often remember my boyhood years spent in scout tents in the beautiful forests of Czechoslovakia. I don’t even feel 1000 metres from home here. Here i surrounded by deciduous trees and on a green lawn, I found, my temporary home again. My friends and I spend our free time with music, singing and games. The only training, that could be talked about is marching exercises. One, Two –One, Two, comes the rhythm of the raincoats and the stamp of shoes. And still we sing. People run out of their farms and isolated buildings curious about our tenor voices. They wave to us, some with clenched fists held high, showing the English sign for victory. We answer the same way and go on cheerfully while rain drums on our raincoats and the wind whips around us.

There is rest in the afternoon, an English class, and some culture. In the evening football is played, or there is discussion somewhere. There is a guitar playing and a cheerful song coming from the tents. By 10.30 it was slowly getting dark. Somewhere a violin plays Chopin’s ”Tristesse”. Then it was replaced by Fibich’s “Poem”. The music is interrupted by the long sound of a trumpet. The last of the latecomers are closing their tents. There is a whisper and muffled laughter from the tarpaulin here and there. But even that slowly dies down. Only the guards walk around the tents and watches. It is a humid night. It has long since stopped raining. A warm breeze strokes the patrolmen’s faces and to the east the first star looks down on the sleeping camp. The guard stops, looks at it and remembers. So far away there lies a beautiful country, CzechoSlovensco, where there is a mother, a girl, and everyone else he loves.

After the first star, others dare. There will be thousands of them in a moment. We are not sentimental, but it seemed to us that they bring greetings from home from those who believe in us and place their hope in us. No, we will not disappoint them. And if only names are left behind, they will not be disappointed in us.

In a foreign land that gave them sanctuary about 300 Czechoslovak military are buried. Many sites are overgrown and almost forgotten. Their final resting places are being located and given head stones so their names will be forever remembered

A tribute to my mother, Helena Dziedzic (1919 – 2006), by Zofia Dziedzic

My mother was born in Homel, Poland in 1919, to Polish parents. Homel is now in Belarus. She spent her early years in Wilno in the eastern part of Poland (now called Wilnius and in Lithuania). She was a clever girl and was finishing h er first year at the University in Lvov in the Ukraine when the Germans invaded Poland and made it impossible for her to continue her studies. Her family had a sad time through the occupation but they suffered no serious hardship or danger. Things changed tragically when the Russians forced the Germans out and replaced them in occupation. They soon started purging potential opponents. Her father, a railway official, had been active in local politics; one night , Russian soldiers came and took him away. They never saw, or heard from him, again. A few weeks later Helena, her mother and three brothers were taken from their home and sent in a railway cattle trucks to Kazakhstan. They were being ‘relocated’ by Stalin. The journey seemed endless and they saw people die of starvation, thirst, or from beatings by the guards. Somehow the family survived. They were put into a resettlement camp and Helena was put to work in a coal mine and later, when local officials discovered her administration capabilities, she was given an office job on the surface. They endured with little food, poor nutrition and suffered from scurvy – but they survived.

Eventually Stalin was persuaded by the western powers to allow relocated Poles in the USSR to be recruited into the Free Polish Forces. Helena joined the air force and she was sent through Iran to the Persian Gulf for training. A few months later she boarded a liner called the Empress of Canada, which was being used as a troopship for passage to the UK. She enjoyed the voyage and the air force training that continued on board.

Then, off the coast of West Africa, The Empress of Canada was torpedoed by an Italian submarine. She sank quickly; Helena just managed to get to a lifeboat. Many others perished as the ship went down. She was haunted ever after by memories of that day. She remembered the screams of Italian prisoners of war trapped on board – because there had been no time to release them, and she could not forget seeing survivors in the water being taken by sharks.

She and her companions were rescued by Canadian destroyers and taken to Freetown to recover. Later she was transported safely to the UK, where she arrived with virtually nothing, and finished her air force training in Scotland and was commissioned.

She served efficiently and enthusiastically at several RAF stations; at one of these she met a young bomber pilot called Jan Dziedzic. They fell for one another and they married just as the war was ending – their close friends called her ‘Lala’ which loosely translated meant ‘baby doll’. They would have liked to return to Poland and they were horrified to see the country given up to the Soviets. Neither would have been able to tolerate that regime so they stayed in the UK. Helena left the service soon after the war d Jan was transferred to the RAF.

Most of Jan’s postings were in East Anglia. In 1947 their first child, Zofia, was born at Bury St Edmunds. Helena’s brother Valentin had survived heavy fighting with the Free Polish Army in the Mediterranean and at Monte Casino and had also decided to stay in England with his wife and young family. The two families settled in Wimbish, near Saffron Walden to grow mushrooms close to Debden where Jan was stationed. Jan, when he was off duty, and Helena worked long hard hours to make a success of the business. Their son, Jerzy, was born in 1951. Their determination and industry paid off and in time they were able to buy land at Stansted.

At Stansted they built a house and named it “Ostra Brama” after a shrine to Our Lady in Poland. They also built a larger mushroom farm at which they worked like Trojans. It started doing well. She worked hard to ensure that they created a solid foundation for her children so that they could integrate and adapt to both English and Polish cultures. Whilst on pilgrimage to Lourdes, Jan and Helena brought back a statue of St. Theresa for the church in Stansted. Then Jan was posted to Cyprus, so they shut the business and house and embarked on what was probably the happiest and most enjoyable three years of her life. It was in Cyprus that her second daughter, Teresa, was born. Whilst in Cyprus, my mother, father and I made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land.

The family returned to Stansted in 1961 and set about making the mushroom farm successful again and, in time, my parents were able to build a bigger, much grander house which Helena largely designed. Just as it was being finished, Jan was posted to Gibraltar.

They did not resume mushroom farming when they got back; Jan left the RAF and they took on a very active retirement. They both loved travelling and, over the next few years they went to Poland (several times), Australia, New Zealand,

Spain, Holland and Finland. During those years, she visited Oberammergau more than once to see the Passion Play.

In 1994 Jan died on a visit to Poland and Helena had to face widowhood. She continued and managed with characteristic fortitude, and even did some travelling; she visited family in Holland and Poland and made a memorable pilgrimage to Knock in Ireland.

As the new century approached it was hard for this energetic and fiercely independent lady to accept that her failing health was steadily limiting her activities and that she would have to stop. Despite becoming quite frail she remained independent, with help from housekeepers and companion ladies she arranged to come from Poland. She was ever a staunch Catholic and one of her sources of greatest pleasure in her last few years was attending this fine new church in Stansted. She lived to have nine grandchildren and eight great grandchildren.

My mother was an intelligent and forthright woman with strong opinions and, at times, could be very abrupt. In her final hours, she asked for forgiveness from anyone she may have offended. Mother, may you now rest in peace.

Scan for an interview on BBC Radio with Jan Dziedzic about the war years flying over Europe on special military missions.

These two stories bring to life the human face of war and its consequences. The Twelve Responses to Tragedy represent millions more whose own stories may largely be unrecorded but they, whose lives were sacrificed during the Yalta meeting, will never be forgotten. Their memorial will never be regarded as insignificant and never again hidden under moss and guano.

With thanks to

H.E. Mrs. Marie Chatardová & Mr. B Chatard. Angela Conner for her support. Gray Elkington, my Artistic Director. George Dziedzic who permitted the use of their family story. The Memorial Association for Free Czechoslovak Veterans.