by Rosemary Sprague

To the four thousand Longwood College students I have taught, and to the students of the future, this history is affectionately dedicated.

A book such as this does not come into existence without the assistance of many people. I wish to express my appreciation to Martha LeStourgeon and the staff of the Longwood College Library, especially to Lydia Williams, archivist, and to the staffs of the Vir ginia Historical Society and Virginia State Library in Richmond and the DAR Library in Washington, DC. Dr. Ashley Neville, archivist of the Methodist Collection of the McGraw Page Library at Randolph-Macon College, receives my special thanks for locating infor mation concerning Presidents Edwards, Crawley, and Whitehead.

I am grateful to my colleague Richard T. Couture for photocopy ing the Mason-Kern-La Monte family papers, and to the Longwood College Foundation for making his work possible. I am most appreciative of the permission granted by the New Jersey Historical Society and its Library Director, Sarah Collins, to use this invaluable material.

I wish to thank especially Longwood's former presidents— Francis G. Lankford, James H. Newman, Henry I. Willett, Jr., and Janet D. Greenwood—for their interest, support, and unfailingly honest answers to questions. I was given full access to all Board of TrusteesA^isitors minutes; and Evelyn Coleman, who served as presidential executive secretary through five administrations, peri odically supplied necessary details which only she could remember. And certainly I have greatly appreciated the interest and encourage-

ment of Dr. George Healy during his interim year and of Dr. William F. Dorrill, now president of Longwood College.

Publication could not have been a reality without the assistance of H. Donald Winkler, Richard Hurley, Donald C. Stuart III, and Nancy Shelton. I want to thank Dr. Stuart's office staff for xeroxing the chapters as they came off my typewriter, to the Registrar's staff for a number of "assists", and to Mary Yovich, Mr. Hurley's "word-processor whiz," for the final copy. I am most grateful to Donna Breckenridge and Don Winkler for the beautiful jacket design, and to Carolyn Wells for her painstakingly executed photo graphs. And there are not enough words in the English language to express my gratitude to Aleece Jacques and Carolyn Wells who caught the typos and peculiar sentences and made a number of valuable suggestions.

Then there are the "intangibles." 1 am indebted to colleagues, friends, and alumni who so willingly shared their recollections with me,and often by a chance remark or a few lines in a letter helped my research without realizing they had done so. In particular, I wish to thank Professors Emeriti George W. Jeffers and John W. Molnar, and Dr. Jed Molnar for sharing his knowledge of Virginia history and for permission to quote the letter in Chapter II. Mr. Couture receives an additional "thank-you" for his permission to quote the letter in Chapter III. Wayne and Marie Delaney helped me through the U.S. Census maze to find what could be found about the elusive President Tinsley, and Dr. Edna Allen-Bledsoe gave me the sources of information concerning Nathaniel W. Griggs, member of the Virginia House of Delegates in 1884. Last, but certainly not least, Joe McGill receives my thanks for sharing his material concerning rule infractions and penalties in the 1940's and 50's.

Finally, my department colleagues and my students—your sin cere interest and support have made it possible, even comfortable, for me to wear my "author's hat" for the past two-and-a-half years. Your patience and understanding, especially during the final phases, have been a great source of strength. From my heart I say to you. Omnibus vobis gratias agol

Rosemary Sprague

Longwood College Farmville, Virginia 15 April 1989

O, n March 5, 1939, the Legislature of the Commonwealth of Virginia agreed to the incorporation of a "female seminary" in the town of Farmville, Prince Edward County. The incorporators names were given as W. C. Flournoy, Joseph E. Venable, Thomas Floumoy, William Wilson, George Daniel, Willis Blanton, and James B. Ely. They,and others, under the title of"The Farmville Female Seminary Association," issued ". .. shares of stock ... at SlOO apiece, in an effort to raise $30,000 for the erection of a building and other items needed to start a school" (Shackelford 2). The land, one acre on High Street, was purchased from George Whitfield Read, law partner of W.C. Flournoy, and his wife Charlotte; and the building, completely paid for, was ready for operation in the spring of 1842. These prosaic facts comprise the beginning of Longwood College. The immediate questions that come to mind are, why build a school specifically for "females" in Farmville, and, equally impor tant, who were the male incorporators? Those who are unaware of the long, proud tradition of Longwood College inevitably ask, "Where is Farmville?" Residents of the area have learned to re spond,"Midway between Dillwyn and Rice," which usually puts an end to the conversation. Actually, the location of the town—sixty miles west of Richmond,fifty miles east of Lynchburg,and sixty-five miles south of Charlottesville—was as advantageous in 1839 as it is in 1989, even though travel in the 1830's was by horseback or

Longwood College: A Hisloty

stagecoach. One stagecoach line, from Washington, D.C., took its route through Prince Edward County, and provided the best route south. In 1831, the Fredericksburg-Halifax(a trip that took three and one-half days) line opened, and in 1834, the year the town of Farmville was chartered, the Petersburg-Farmvilie line was in oper ation. Passengers could make connections at Farmville for Rich mond,or Lynchburg,or for points south, perhaps staying overnight at the Eagle Hotel, or at the most modest Farmville Tavern. But even more important to the town's prosperity was its location on the Appomattox River.

Farmville took its name from "The Farmlands," which were part of "Bizarre" Plantation, owned by Richard Randolph, brother of John Randolph of Roanoke. After his death, a group of publicspirited citizens purchased fifty acres of "The Farmlands" from his widow,Judith Randolph, which were laid out in half-acre lots(Wall 163). That this property was on the Appomattox River proved to be the new village's—later, town's—greatest asset because it became a river station from which tobacco grown on the farms in Prince Edward and the surrounding counties could be shipped by barge to the main market at Petersburg. Flour and cord wood were also export staples, contributing to the town's growth and prosperity. The Lithia Mineral Springs were another attraction. By 1832, the Farmville Chronicle was being published on a regular basis, and, despite the temporary setback of the panic of 1837, a branch of the Farmers Bank was authorized for Farmville by the Legislature in that same year. The town had already petitioned the Legislature in 1836 ". .. to charter railroads from Petersburg to Farmville to Danville" (Bradshaw 327). The first rails were not laid until eleven years later, but the petition indicates the early awareness on the part of the Town Trustees of the advantages train service would bring. By 1839, the Female Seminary incorporators doubtless viewed the town's ever-increasing prosperity and thought,"Why nol Farmville?"

There was doubtless another factor that contributed to their thinking: the work of those pioneers who were already advancing the cause of education for women in the north. Benjamin Rush of Philadelphia, whose Young Ladies Academy was chartered in 1787, and whose student body in 1792 included several from Virginia (Woody 326); Emma Willard, Troy (N.Y.) Female Seminary (1821); Catherine Beecher, Hartford (Conn.) Female Seminary (1823); and Mary Lyon, South Hadley (Mass.] Female Seminary (1837), are names which come immediately to mind. Nor is it improbable that their work was known in Farmville in the 1830's; Hampden-Sydney Academy five miles down the road had been founded in 1776(It was

not chartered as a college until 1783.), and had sent a number of its graduates to Princeton University. Jonathan P. Gushing, president of Hampden-Sydney from 1821 to 1838, was a graduate of Dart mouth College. Even more pertinent, Eleazer Root,". .. a native of New York and a graduate of Williams"(Bradshaw 167), had opened a girls' school at Prince Edward Courthouse(now Worsham)twelve miles from Farmville in 1832; and the Reverend A. J. Heustis, graduate of Wesleyan University in Connecticut with teaching experience in New Bedford, Massachusetts, opened his school for girls in Farmville in 1835. Even though these men may not have had direct contact with the northern educators, they certainly knew of their work through their professional journals and newspaper accounts. And they surely must have been aware of Horace Mann, secretary of the newly created Massachusetts Board of Education, whose pioneer efforts to improve public education in that state had begun in 1837. The curriculum of the Heustis school, along with English language and literature, and the usual "music, drawing, painting"(Bradshaw 164), included an emphasis on science which Willard and Beecher had introduced into their schools. "French and ancient languages"(Bradshaw 164) were also taught.

Heustis did not remain in Farmville long; in 1837, his name appears " ... as one of the principals of Buckingham Female Collegiate Institute ..."(Bradshaw 164). It is interesting to note that Emma Willard, in 1818, in a letter to the New York Legislature urging state support for women's education, said of the schools available to them, "They are temporary institutions founded by individuals whose object is present emolument; these individuals cannot afford suitable accommodations, nor sufficient apparatus and libraries... the teachers are accountable to no particular persons or board of trustees .. ."(Woody 308). Whether these criticisms are applicable to the Heustis and Root schools, which were essentially one-man operations, is impossible to say; however, from the very beginning there was a significant factor which differentiated the Farmville Female Seminary from these. It grew out of a corporation formed by seven of the town's leading citizens, who themselves contributed financially to its foundation, and therefore had a per sonal stake in its success. Who were these men, and what can be implied from their contribution?

The first name on the list, and probably the chairman of the corporation, is that of William Cabell Flournoy (1809-1861). His father, John James Flournoy,(the son of Jean Jacques who came to America in 1686, a Huguenot refugee from Catholic persecution in his native France)was the owner of"Union Grove," a large property

south of FarmvUIe, and had been appointed one of the first county commissioners for public education in 1818 (Bradshaw 169) His mother was Anne Carrington Cabell, daughter of William Cabell Jr., of "Union Hill" in Nelson County, and Anne Carrington of Charlotte Courthouse. A graduate of Hampden-Sydney College, William Flournoy went on to study law (possibly at Creed Taylor's celebrated law school at "Needham," the Taylor home across the Appomattox River in Cumberland County), which led to his con stant involvement in Democratic Party politics. UlHmately he would serve in the House of Delegates(1850-51,1851-53)and as Common wealth's Attorney for Prince Edward County (1846-51). He was one of the early proponents for the railroad, and, when the RichmondDanville Line was chartered in 1847, he was appointed one of the commissioners to sell stock(Bradshaw 329). Another of his interests was the Farmers Bank, an involvement which provides a priceless vignette giving insight into the man. At the 1846 stockholders meeting, Flournoy presented a slate of directoral nominees, includ ing himself. Nathaniel Venable of "Slate Hill" presented a rival slate, including himself. At a final vote, after what Venable described as a "most disagreeable scuffle"(Bradshaw 322), both Flournoy and Venable were elected! This episode in part confirms the apparently unforgettable"... gleam of Flournoy's eye, the glow of his words, the force of his logic, the sting of his sarcasm" (Bradshaw 223)! Clearly, William Cabell Flournoy was not a man to be trifled with! However, Elizabeth Marshall Venable in THE VENABLES OF VIR GINIA provides an additional portrait: ". . . a talented, distin guished lawyer, an attractive, benevolent and honorable man; his many virtues will be long remembered"(52).

It was an era when the wealthy lived by the code of noblesse oblige, and his marriage in 1834 to Martha Watkins Venable united him to a family equally prominent and public spirited. Her father was William Lewis Venable of"Haymarket" who had seen active duty as a lieutenant in the County Militia during the War of 1812(Bradshaw 230), and had served as a County Magistrate and as a trustee of Hampden-Sydney College. William Lewis was the son of Nathaniel Venable of "Slate Hill," renowned for his many contributions to the county and the Commonwealth, including fourteen children! Prior to the Revolutionary War, Nathaniel had served in the Virginia House of Burgesses,and had been a member of the committee appointed to plan the buildings for Hampden-Sydney College. He was also a member of its first Board of Trustees. Speculation is not permitted to the writer of history; still, it is fascinating to imagine what influence

Martha Venable Flournoy, given her background, may have had upon her husband's involvement with the Female Seminary.

Joseph E. Venable (1807-1881), the second named incorporator, was the son of Robert Venable, a "connection" of the "Slate Hill" Venables, and his wife Sarah Madison, was the daughter of James Madison, a Farmville tobacco manufacturer. Robert was the owner of a large property and a general store near Prospect, Virginia, but he had political interests, serving as a judge and as a county sheriff. In 1820, he donated the land for the Prospect Methodist Episcopal Church. He was a close friend of the Reverend John Early, who frequently stopped over at the Venable home when he rode the circuit; Early once remarked that on a November visit in 1807, ". . . I ate as good a watermelon there at that season of the year as 1 ever did in the summer"(Bradshaw 366). It is interesting to note that Mr. Early, as ". . . presiding elder of the Lynchburg District, planned the organization of a Methodist Church in Farmville. A building was erected in 1832 on the lot still occupied by the Farmville Methodist Church"(Bradshaw 265).

Robert's son, Joseph, who always referred to himself as a "far mer,"continued to work the family land and developed the "Early Joe" peach (Bradshaw 341). Apparently, he was very much inter ested in and influenced by the work of Charles Woodson, recog nized state-wide as an agronomer of first rank. In 1829, he was one of the six Trustees who governed the village of Farmville. He was in volved in tobacco manufacturing and was co-owner of a grist mill; as might be expected, he was also involved in bringing the railroad to Farmville(Bradshaw 329). In 1845, he would be appointed a Justice of the County Court(Bradshaw 680)and,in 1845, he would ser\'e as a commissioner to divide the county into five judicial districts and to set up a polling place for each one(Bradshaw 219). The Temperance Movement was another of his interests. His wife, Mary Ann Dunnington, who he married in 1832, was the daughter of William Dunnington, tobacco grower and later tobacco manufacturer.

Thomas Flournoy (1804-1892) was William Cabell Flournoy's cousin. His father was Dr. David Flournoy of "Chantilly," a distin guished physician who had studied at the University of Edinburgh. Thomas attended Hampden-Sydney, and graduated from Princeton University in 1825. In 1827, he married Frances Matthews Venable, sister of Martha Venable Flournoy. Described as a ". . . man of great personal charm and courage"(Venable 53), he was active in politics in both Andrew Jackson campaigns and worked for Harrison against Van Buren in 1840. In 1845, he was appointed a Justice of the County Court, indicating that he had been admitted to the bar. His great

Longwood College: A History

interest, apart from law and politics, was horse breeding, which apparently provided part of his income as well. He was not the only man interested in horse breeding, even though racing was not a part of county life, but he was certainly the most colorful. "In the 1830's, Thomas Flournoy brought to Prince Edward, a black Arabian stallion which had been bred in the stables of the Emperor of Morocco... The stallion was presented by the Emperor of Morocco to the United States through the consul at Tangier, and was sold by Act of Congress February 21, 1835" (Bradshaw 34^5). Although Thomas Flournoy ". . . took his Arabian on a tour of the March courts, going to Buckingham, Nelson, and Amherst counties and to Lynchburg after the Amherst court" (Bradshaw 345), there is no evidence that the horse was ever raced.

There is very little information concerning William Wilson and George W. Daniel. Wilson was one of the commissioners appointed to sell twenty-five acres of the Randolph estate as half-acre town lots (Bradshaw 296); evidently he had some connection with the Ran dolph business interests. Daniel was active in county Democratic politics, but he was interested in education as well; he was ap pointed a District School Commissioner in 1846 (Wall 150). Willis Blanton is listed as one of the elected (by the freeholders) Town Trustees in 1839-41. He was also one of the petitioners for the railroad in 1836 (Bradshaw 327). James B. Ely was a trustee of the Randolph estate and was granted an ordinary (innkeeper's) license in 1829(Bradshaw 310). He, too, was active in politics and involved with the railroad petition, and in 1846 he was one of the incorporators of the Farmville Savings Bank. He served two terms as a Justice of the County Court. When Farmville became the county seat in 1871, Ely sold half an acre of land for the new courthouse and jail. (Bradshaw also notes the ". tournament held in the field on the J. B. Ely estate on October 8, 1875" [649].)

The incorporators raised the $30,000 to finance the seminary build ing, and the cornerstone was laid in 1839. A metal plaque inscribed "Farmville Female Academy built by Joint Stock Company AD 1839" (discovered in 1897 when part of the building was demolished to permit expansion) was set into it. Construction was completed on May 26,1842, at which time the deed to the land on High Street was formally conveyed to the stockholders in return for $14,000, an arrangement which further indicates community commitment to the venture. True, George Read was William Flournoy's law partner but certainly his willingness to wait for his money for two and a half years reveals an unusual degree of trust and good faith.

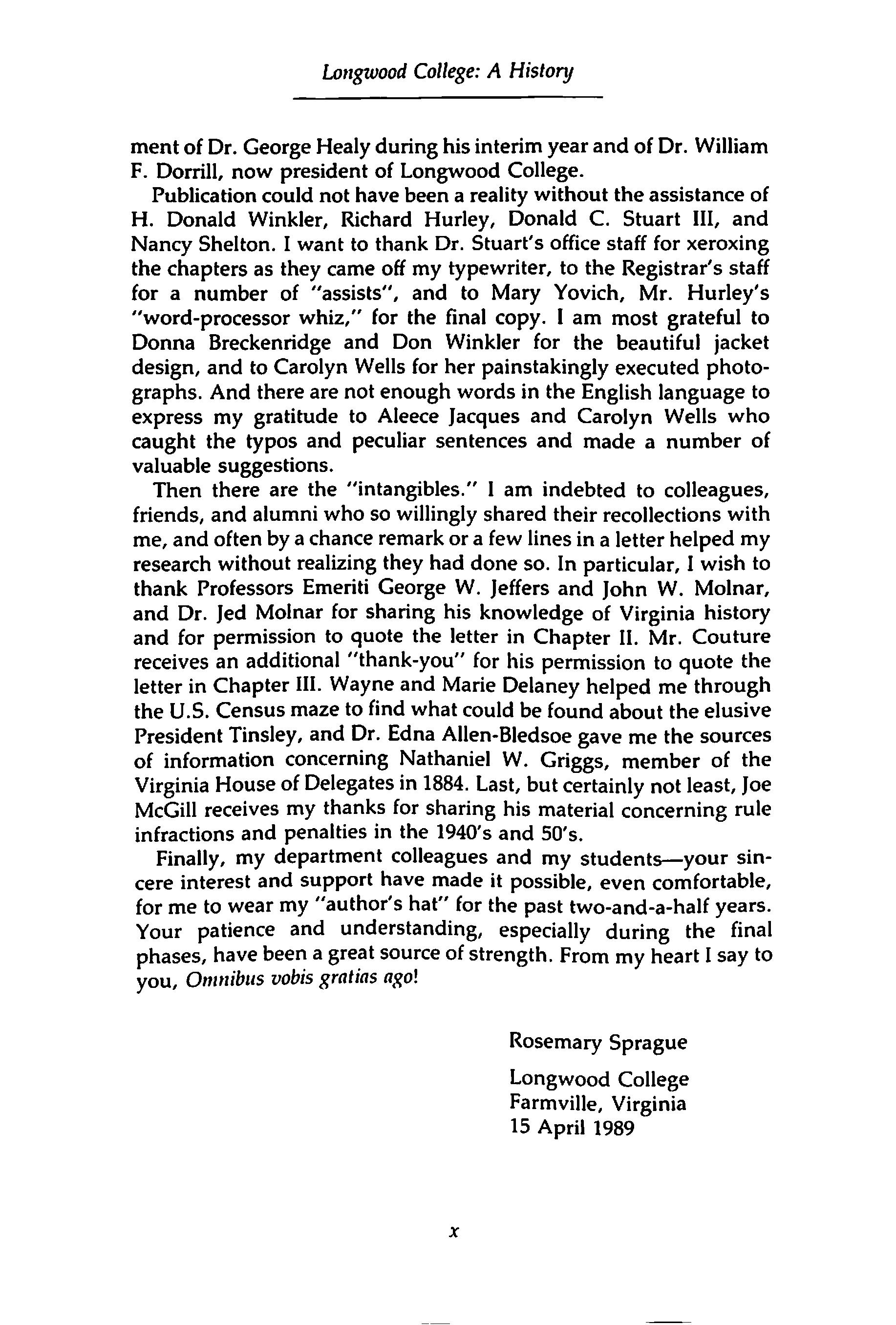

Judging from an old engraving (dated 1859), the Seminary was

Original Placque

indeed "spacious and comfortable," and its location was, as de scribed by a later principal, ". . . for beauty of situation surpassed by few in the country" (Shackelford 3). The engraving shows a square, three-story brick building with a hipped roof. Five long windows across each of the two upper stories, and two on either side of the front door, provided a pleasing symmetry. A circular drive, with a wide lawn and many trees on either side and a grass island in the center, led to a small columned and roofed front porch three steps above ground, and the entire structure was surrounded by a picket fence with a double gate. Several young ladies, properly bonneted and probably gloved as well, are pictured strolling on the lawn, while another young lady genteely rides sidesaddle outside the fence on a spirited white horse, accompanied by her top-hatted, frock-coated escort. The total effect is more that of a stately private home than that of a school, which was probably what the incorporators intended. Certainly over the years one asset continually stressed by Longwood College under all of its earlier names is its "home-like" atmosphere; actually, until 1944, the Dean of Students was called "the Head of the Home", and only recently has the "Home Office" become the Information Office.

The building was completed; however, it took a little time to find teachers and a principal. But all was in readiness on July 17, 1843. "The school opened with Solomon Lea as principal and offered

Female Seminary, 1859

English, Latin, Greek, French, and piano. The tuition fees for five months were $20 for piano, S15 for senior English, $12.50 for lower English, and $5 for each foreign language, with board available at $8 to $10 a month" (Shackelford 3). Mathematics and science are conspicuous by their absence; their omission is not really surprising because the conservative incorporators doubtless adhered to the prevailing view that these disciplines were too strenuous for the female mind, no matter what the Yankee schoolteachers were advocating up north! However, by 1856 that view had obviously changed. Bradshaw records that "A visitor from Cumberland" attended the public examinations on June 24 of that year.

Principal, teachers, and several gentlemen conducted the examinations. The examination of Miss Susie Dunnington in chemistry would have done credit to a college junior, thought this member of the audience; he mentioned the Misses Bettie Watkins, Hattie Read, Christianana Osborne, Hattie Venable, and Louise Fouqua as showing a knowledge of textbooks which would elevate them to the highest grade of scholarship. Exam inations were conducted in Latin, French, astronomy, chemis try, botany, rhetoric, philosophy, algebra, grammar, geogra phy, and arithmetic. A dialogue by three young ladies pointed out the deficiencies of superficial education of literary polish and parlor accomplishments "afforded by too many female schools" (165).

This account is the only concrete evidence of the curriculum pursued at the Farmville Female Seminary in its first quarter century. Nor is there much information concerning the first princi pals beyond their names. Solomon Lea was succeeded by his brother, the Reverend Lorenzo Lea, "former president of the Buckingham Female Collegiate Institute" (Draper ms.), who was followed by Lorenzo Coburn, described as "... northern man . . . remembered mainly as the possessor of a very long nose" (Burrell 302). John B. Tinsley was appointed principal in 1850; he had been ". . . principal of Powhatan Female Seminary" (Draper ms.). The 1850 United States census(Visitation 352) notes that he was forty-six years old and came originally from Richmond. His wife, Eliza, was forty-five, and they had five children, all of whom were born in Powhatan. The census also lists the names of twenty-two Seminary students, seven of whom also came from Powhatan; perhaps Tinsley brought a "following" with him. Benjamin Could took the helm in 1855. However, despite these administrative changes, it is a fact that the Seminary definitely thrived.

There is one glimpse into those early years, provided by the autograph album of Miss Susan Campbell Jordan in the Longwood College archives. A square, thin, board-bound blue volume, it is filled with poems and "sentiments" in the beautiful copperplate handwriting of her classmates and obviously admiring gentleman friends, many of which are dated 1844 and 1845. (There is also a recipe, "To boil rice Savanna fashion".) And the principal contributed.

As I am getting old. My poetry, love and Album days, are over With me.

Solomon Lea June 13th, 1845

Another, obviously supplied by an admirer, tells the world,"Wom an—the only power before which free men may bow without disgrace, and brave men without dishonor!" And finally, one entitled "A Parody," dated "Farmville,July 27, 1844," but unsigned:

How do the little boys of Farmville Improve each shining hour: In gathering pleasure every day From our Seminary's Bower.

An "improvement" which continues, with variations, to this day!

O. n May 24, 1860, the Seminary Charter was amended by the State Legislature and the school received a new name: Farmville Female College. The familiar names—William Flournoy, Thomas Flournoy, Joseph Venable, George Daniel, and James Ely (now chairman of the corporation)—had been joined by those of Francis Nathaniel Watkins and Howell E. Warren. Watkins was a native of Prince Edward County, who had graduated from Amherst College and the University of Virginia Law School. Upon his return to Farmville, he quickly established himself as an able attorney; in 1869, he would be elected a judge and achieve a formidable reputation as a jurist. He had served on the Hampden-Sydney board of trustees, and,as might be expected, he was very active politically, first for the Whigs and later as an organizer of the Conservative Party. He and his wife, Martha Ann Scott of Bedford County, lived at"Ingleside," two miles from Farmville near the Bush River Bridge. Howell Warren was also an attorney, but his principle forte was banking, though he had served as a justice of the peace and would, in 1865, be named a justice of the County Court. In 1860, he was involved in the establishment of the Planters Bank, of which he would become president in 1873. In 1861, he became president of the Farmville Savings Bank and an incorporator for the Farmville Insurance Company. In 1860, his evident flair for finance would

doubtless have made him an important asset to the new Female College.

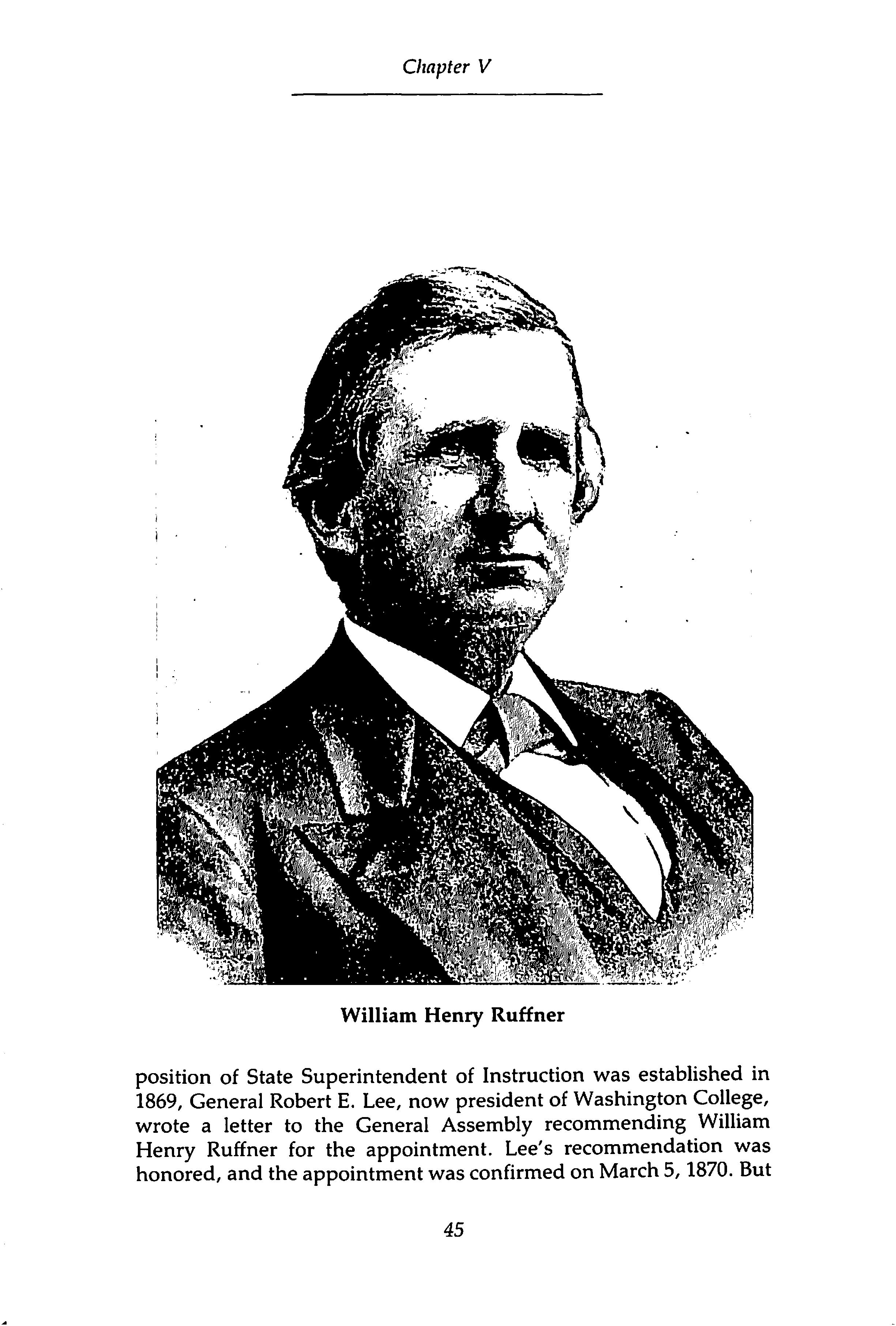

Seminaries do not become colleges overnight, and the previously noted expansion of the curriculum by 1856 indicates that the Seminary incorporators may, at that time, have been thinking of what would have been a giant step. Certainly the prosperity of the fifties contributed to their optimism, a prosperity which doubled when the South Side Railroad Company opened High Bridge, four miles from Farmville, in November 1854. "Spanning the Appomattox River from a bluff in Cumberland County to a bluff in Prince Edward County"(Smith 5), the bridge made the transport of goods, including perishable agricultural products, faster between Rich mond and Petersburg than river transport, because "Shipments were no longer delayed due to weather factors or winter snows" (Smith 5). But possibly the crucial factor in the incorporators' decision was the new Seminary principal, George La Monte, who arrived to take up his duties in the late summer of 1859.

Whether his arrival was the result of a deliberate search for a possible College principal, or whether it was simply good luck for all concerned, will never be known, but La Monte applied for the position and was hired. Born in 1834 in Charlottesville, N.Y., he grew up in a devoutly Methodist home. He received his Bachelor's Degree from Union College in Schenectady, an institution which emphasized not only religious observance, but also the classics, mathematics and the sciences, in 1857, and two years later received his M.A. degree. Under normal circumstances, he would have remained in New York State, but, while he was still in college, he, together with his brother Thomas and some other students ". . . were hired by a New York publishing firm to go south and canvass for the preparation of a map of the United States" (La Monte papers). Their territory was Frederick Count\', Virginia. George La Monte promptly fell in love with Virginia, with, as he put it, ". . . the land of boasted honor and chivalry—the land rendered sacred by a host of such honored names as Henry, Madison,Jefferson, and Washington"(La Monte,June 2, 1856). He also fell in love with Miss Rebecca Kern of Romney. In June 1958, he returned to Virginia to marry Rebecca, and to begin his new job as assistant principle of the Valley Institute at Winchester.

La Monte,at the age of twenty-five, was an ideal candidate for the principal of Farmville Female Seminary. He was very well educated, and he had some interesting connections—in the La Monte papers there are letters to him from President Millard Filmore and Horace Greeley, accepting honorary memberships of the Wesleyan Associ-

Longzpood College: A Hislon/

ation of the New York Conference Seminary. His recommendation from the Valley Institute, dated December 18, 1858, was unimpeach able:

We take pleasure in certifying to the high character that Mr. Geo. La Monte has sustained among us as a Teacher and a Gentleman. We believe him to be fully qualified to conduct a Female School of High Grade; and feel assured that his experi ence and enterprise, his moral worth and literary qualifications eminently fit him for such a position.

And the qualifications of the eleven signatories were attested to in a note from Henry A. Wise, Governor of Virginia.

But even more important to the future college were La Monte's views concerning the education of women. In July 1860, he stated his conviction that,"Woman is neither the inferior nor the superior of man. Each is the compeer of the other." In his address at the presentation of awards on June 26, 1861, after complimenting the students for their diligence despite ". . . the many distracting influences by which you have been for the last few weeks sur rounded" (Virginia had seceded from the Union on April 24), he continued.

If our armies in the present contest succeed and do not doubt it for a single moment, what would our independence be worth if our daughters, the mothers of our future statesmen, are not cultivated and educated and equal to the great trust confided to them?... Our women, God bless them! should be fitted to be not only the guardians but the teachers of our children.

Urging them to ". .. be not content with halfway excellence," he admonished, "Remember that education does not consist in the amount of knowledge we may possess, but in the degree of mental culture and self discipline: and in your reading select such books as will make you think most. . .

He also expressed strong convictions concerning masculine atti tudes and feminine response:

The preposterous absurdities of chivalrous times still exert a wicked influence over the character and allotment of women. Men are not polite, but gallant. They do not act towards women as beings of kindred habits and character, but as beings who please and who they are bound to please.

He is the man of politeness who evinces his respect for the female mind. He is the man of practiced insolence who tacitly says when he enters the society of women that he should not bring his intellect with him.

Unhappily a great many women themselves prefer this varnished and gilded contempt to solid respect. They would rather think themselves fascinating than respectable—a large class by their mothers are taught less to think than to shine. .. To be accomplished is of greater interest to them than to be sensible. .. to charm by the tones of a piano than to delight and invigorate by intellectual conversation.

The students were, of course, to be ladies; that went without saying. They were to "cultivate high qualities and gracious gifts of soul." But for La Monte, the word ladi/ implied much more. In his lecture entitled "Womanly Perfection," which he presented to the LeVert Literary Society in May 1862, he remarked.

Another element of character essential to womanly perfection is self-reliance. . . You owe it to yourself especially in this time of war and desolation to learn this art and acquire the power of relying on your own energies and attainments. Mental strength, firmness, courage, industry and perseverance are the foundation of this element of character.

And he concluded.

Endeavor in your conversation to say something useful, rather than something smart. Reflect when you read—write frequently. For reading makes a free man, conversation makes a ready man, but writing makes a correct man. Do not read novels, for if you do, the result is an obscure, feeble intellect, a weakened memory, an extravagant and fanciful imagination, bemused sensibilities, and a corrupt heart.

THE ANNUAL REGISTER AND ANNOUNCEMENT OF THE FARMVILLE FEMALE COLLEGE for 1859-60(apparently the word COLLEGE was included in anticipation of the new charter of 1860) represents the fulfillment of La Monte's convictions and ideals. The religious foundation of the college is evidenced by the fact that the Reverend John Early, now D.D., had accepted the chairmanship of the twenty-three member Board of Visitors, which must have been quite a coup for the College and implies the continuing influence of

Joseph Venable. The REGISTER also stressed the religious ambience the students would experience, a very important factor for parents of young girls. The major emphasis, however, was academic."With more faith in the intelligence of girls than was then common, the new college president outlined a curriculum which would discour age many a present Longwood student" (Schlegel 4). George La Monte taught classes in Latin, Higher Mathematics, and English Literature. Miss Susan B. Fowler was named Preceptress—an office which carried the responsibility of the present Dean of Students— and was also "Instructress in French and English Branches and Drawing and Painting." Mr. A.S.Simmons was"Professor of Music on Piano and Guitar, Vocal Music, and Organ," and Miss Anna A. M. Woodward was "Instructress on the Piano." One is struck by the evident versatility of these first faculty members,and also by the fact that from the beginning English literature, foreign languages, math ematics, and music were emphasized, an emphasis that continues at Longwood College today. No science professor is listed, but science courses were offered and were probably taught by members of Hampden-Sydney or Buckingham Female College faculties. Minis ters were called upon to teach courses in philosophy, both intellec tual and moral, and "Evidences of Christianity."

There were two "Departments." In the Preparatory Department, students received instruction in "Reading, Writing, Spelling, Defi nitions, English Grammar, Arithmetic, Geography, History, and the simpler forms of Composition"(REGISTER 10). There is no indica tion that these courses were "remedial" in the present day sense; they were designed to prepare younger girls for the rigorous fouryear collegiate curriculum. The grading scale college-wide was a scale of 1-5, 3 3/4 being accepted as demonstrating sufficient proficiency to continue to the next level.

The Collegiate Department was heavily weighted in favor of English Literature, Composition, Rhetoric, Mathematics—including both Algebra and Geometry(The April 1860 monthly report card of Lucretia Kem, Mrs. La Monte's younger sister, reveals that she pursued these concurrently with 5's in both.) and Philosophy. The sciences were represented by course offerings in Chemistry, Physi ology, Geology, and Astronomy. But there is one surprising evi dence of practicality: students in their final term were expected to take "Book Keeping and Forms of Business," along with "Principles of Taste." Nor was this all. "Reading, Writing, and Spelling throughout the course. ..Latin and one of the Modern Languages and Music will be required of a candidate for a diploma"(REGISTER 11). (Lucretia Kern's April 1861 report indicates that she was studying

French, German, and Piano, with 5's in all three.) Finally, "Every pupil is required to write, semi-monthly, an original essay and submit the same to the president"(REGISTER 10). Today's advo cates of "Writing across the curriculum" might like to consider reinstating the last item.

Students who achieved the 3 3/4 required passing grade in all classes were awarded the diploma of Mistress of Arts. There was some flexibility; a student might also pursue a single discipline and receive a certificate of proficiency in that discipline, or she could choose to omit the modern language and receive the diploma of Mistress of English Literature. The REGISTER states that "A valu able Library and the best Journals of the day are always accessible to the young ladies, and Maps, Globes, Philosophical and Chemical Apparatus, furnish ample means of illustration in the school . . ." (8).

The "home atmosphere" was emphasized:

The Pupils boarding in the college reside with the family of the President, and are under his guardianship. In their evening studies, they will enjoy the benefit of his assistance and that of his colleagues. Every exertion will be made to render the College an agreeable HOME to resident pupils. To ensure to each pupil all the care and attention promotive of health and comfort, and to make this emphatically a HOME SCHOOL and to give it a HOME air and influence, the number of boarding pupils has been limited to thirty. One distinctive feature of this Institution is its social arrangements; the lady teachers are expected to be as elder sisters to the young ladies, and inculcate punctuality, diligence, order, neatness, easy and graceful de portment as much by example as by precept. Instead of remain ing in cliques in their rooms, out of school hours, to spend their time in gossip and scandal, the young ladies are encouraged to assemble with teachers in parlors and library with needle work or a book, and a HOME feeling thus induced, manners are improved, conversation becomes easy, much knowledge is acquired, and happiness secured (REGISTER 6).

The boarders gathered in the parlor for family prayers "... one hour after the rising bell"(REGISTER 9). Lucretia Kern's April 1861 report records eighteen absences from prayers. Twenty-five would have brought a demerit: the report notes,"Any pupil receiving one demerit will not be entitled to a prize," and, even more sternly, "If a pupil receives three demerits in one session, she shall be sent

home." Demerits could be "earned" by inattention to manners, neatness, orthography, punctuality, penmanship, and by absence from prayers or "recitation."

After prayers, the students had their breakfast, followed by a daily chapel, which all students, including all those who lived in Farmville or who boarded with "approved" families, were required to attend. The service always concluded with . . sacred music accompanied with an instrument and under the direction of a professor"(REGISTER 9). Then the students attended six hours of classes. (There is no mention of a break for lunch.) Parents, by means of the monthly reports, were reminded,"It is very important that your daughter be in school every day," and, "Please see that your daughter studies AT HOME." The last injunction was not needed for the boarders; after classes, their time was free for study or for a stroll around the college grounds until "Tea," which was probably a light supper. Four evenings a week there was an hour-and-a-halfstudy hall presided over by a member of the faculty. The day concluded with family prayers, and a free half-hour before the "silence bell" announced the time to retire, after which each student's room was visited by Mrs. La Monte or a female faculty member, not in the spirit of "bed check," but rather as a continued emphasis on the College as a home. Students were expected to attend Sunday School and church services, and on Sunday evening, the "family" gathered in the parlor for an hour devoted to reading Scripture and to singing "sacred melodies"(REGISTER 9).

The social rules as listed on page 12 of the REGISTER were stringent by modern standards. "Novels and promiscuous pam phlets" were forbidden "without consent of the President." Parents were reminded ". .. not to encourage their daughters in visiting home oftener more than once in three months. Those pupils gen erally do best who visit least during the school session." Students might not receive ". ..the calls of gentlemen who may be strangers to the President and not specified by parents. . . unless authorized by letters of introduction," and even with authorization only ". from 4 o'clock to 5 p.m. on Wednesdays and Saturdays." No callers were permitted on Sunday, and students might not ". . . spend the night out of the College unless under very extraordinary circum stance." Finally,"Inasmuch as the table of the College is at all times furnished with an abundance and variety of good food, well prepared, pupils will not be allowed to receive boxes of eatables, except by special permission." Parents were also requested to provide their daughters with ". . .a simple state of dress," and ". . . not to give them any considerable amount of pocket money." The

students furnished their own towels and table napkins, a silver fork, a napkin ring, and ". . . a spoon to use in her room."

The students, however, adjusted. They lived by similar rules at home, so College rules came as no surprise. And they were, for the most part, content, as is evidenced by a letter sent to Miss Willie Morgan of Petersburg, on October 25, 1861, by her Cousin Lucy. (The original spelling and punctuation have been retained.)

My Dear Cousin, 1 promised you, I would write to you; but I reckon you began to think 1 would not do it. I hope you will not judge me harshly, for it was not that 1 did not wish to write to you, that I have delayed this long, but that 1 have not had the opportunity to do so. I intended to have written to a great many girls; but time will not come to me to do so. Dont you think it very itmccomodating in time not do what I wish it to? I know you do. This is a splendid school if every girl, does not learn very much while hear; it most assuridly is her own fault. For Mr. La Monte takes all the pains he is capable of taking; with each and every girl. Mr. Preot is an excelent teacher; he does everything in his power to make the girls happy and comfortable. Mrs Preot and Mrs La Monte are certainly the most agreeable ladies I have ever met with. Excuse me for remaining so long in one strain but really, when 1 begin to talk of our Teachers, I never know when to stop; just let me say the school is indescriably exclent, and the Teachers are indescribably good.

Lucy's spelling may leave something to be desired, but her enthu siasm is unmistakable.

A great source of recreation was the LeVert Literary Society. The REGISTER notes,

The young ladies boarding in the College have organized a society for mutual improvement called the "LeVert Literary Society," which is in a highly prosperous and flourishing condition. Its objects are to cultivate the friendship, refine the taste, improve the manners, and develop the social feelings of its members. The exercises are varied and interesting, and all pupils boarding in the College are expected to connect them selves with this society (9).

A keen participant was Lucretia Kern, who was also one of the major contributors to the Society's newspaper, the LAUREOLA.

The unique issue appeared on December 25, 1861, with the an nouncement, "This paper—the LAUREOLA—is now for the first time printed and cleared for circulation, the proceeds of its issues [ten cents a copy] to be devoted to the holy cause of the soldier." In the list of faculty members, the names of Arnaud Preot, as teacher of music and modern languages, and Mrs. Preot, as teacher of music, appear for the first time. Both the Preots would be very important to the future of the Female College.

The contributions to the LAUREOLA—poems, short stories, essays—were signed by "Grace," "Olive,""Sunshine," "Traviata," or simply with initials. Miss L. H. K. (Lucretia Kern) was listed as "editress." Perhaps she was also the "authoress" of the following "Donts (sic.) for Young Girls:"

. .. dont fight while there is anybody to kiss, and dont talk scandal and look religious at the same time.

Dont "wish all the boys were in Halifax," when from the bottom of your heart, you wish they were all in Farmville. Dont say, you will "never, no never get married" until you are quite sure somebody means to ask you and when you are asked dont say "no" when you mean "yes" nor "yes" when you mean "no."

Dont always manage to step on the skirt of somebody's dress behind whom you are coming downstairs or out of a church door and dont always forget to thank the gentleman who opens a door for you, or finds you a seat in the railroad car, nor that other gentleman who pulls down all the goods in his store to please you and smiles when you decide what darning needle to take.

Dont laugh at a mistake until you know that you or your Grandmother has not made one very similar, and don't think fine clothes make fine ladies any more than "fine feathers make fine birds." And dont, oh! dont be so careful to repeat every word of that secret you promised never, never to tell.

Dont think Mr. is the best preacher you ever heard just because you can't understand anything he says, and dont insist that Dr. is the best physician in the world just because he is handsome and has such sweet eyes. Dont love all the good-looking people and hate all the ugly ones but remember the old adage,"Handsome is, that handsome does."

Dont make a great fuss about a biped in uniform until you know he is every inch a Soldier, and wont run away from the first Yankee he sees; dont mope because the times are hard, and tea and coffee are scarce, dont be afraid of the sunshine, the

fresh air, the pure water, or of wearing out your last pair of shoes, and dont let the Yankees think we are afraid of them as long as there's a man left to fight for us.

The light-hearted, schoolgirl tone of the publication may at first glance seem surprising, considering the fact that the divided nation was already at war, and . . early in 1861 eight volunteer compa nies had been organized in Prince Edward County"(Bradshaw 380). In a letter dated December 14, 1861, Lucretia Kern wrote to her

father, "Mollie Harrison's soldier brother has been here to see her—His presence created quite a sensation among the girls." It must be remembered, however, that in December 1861, no one believed that the war would last long, and after Confederate victories at Fort Sumter and First Manassas(Bull Run)all Virginians held as an article of faith that the Confederacy would prevail. Farmville Female College closed for the Christmas holidays, and the students returned for the spring term to continue their studies with President La Monte's purpose constantly before them: "Proficiency will be secured by a love for science and art, and by instilling the highest motives of being useful thereby .. .(REGISTER 7). At that time, no one could foresee the trials and the testing that the next four years would bring.

JUjvents moved swiftly, and during the spring and summer of 1862, the La Monte family was struck by a series of personal tragedies which the College family must have suffered with them. In March, the Kern family home at Romney was almost completely destroyed by fire, a casualty of the Valley Campaign. Homeless, Rebecca La Monte's mother and a younger sister, Tillie, had to come to Farmville. Rebecca's letters to her father in Richmond reflect her growing anxiety. On February 24,1862,she had written,"It is so sad to look at these dear, happy,frolicking girls, and think what may be in store for them." A major concern was her sister Lucretia's future. "Is it not better," she wrote on March 7 1862, "for her to try to establish her independence at once? Oh!I wish I could make her see her duty as 1 see it now. It is not time to linger in pleasant places and stand clasping each other's necks, when father and mother are wide apart and Home there is none for any of us." Her anguish is apparent: "If 1 were to die tomorrow, Lulie would not longer have a claim here —where would she go then?" The arrival of Mrs. Kern and Tillie settled the question for the moment. Lucretia was needed to help at home;she would finish her studies at the College, receive her diploma, and remain in Farmville at least through the summer vacation.

But the College, paradoxically, flourished. George La Monte, with the assistance of his father-in-law, had obtained a substitute to serve

Longwood College: A Hislonj

in his place in the Confederate army. The alternative would have been to close the College, a prospect no one wished to contemplate, especially parents who were convinced that Farmville was a safe place for their daughters. True, this conviction could disrupt family life. In a letter dated December 11,1862, Laura C. Bland wrote to her mother Mary Bland of Burt Quarter, Dinwiddie County,

were to wnce to you i migm leei a nine oetter arterwaras. 1 do not know what I shall do up here all of Christmas, it will be so very lonesome. I hope this will will be the first and last Christmas 1 will ever have to spend from my sweet home. Even Mr. La Monte intends going away. Please come to see me if you do not stay but one hour.

Even Bettie Boisseau intends going home. If you do not come write me a long letter for Christmas and send me another dress. I think Farmville is one of the lost places on earth.

Then the war struck home. On June 22, 1862, Lucretia, upon hearing of the imminent action involving Generals Beauregard and Jackson in Richmond, wrote her father a frantic letter;

Oh Pa, my baby Brother, our little fosie must be exposed in this fearful hour. 1 thought I was strong and patriotic, but this is too great a trial for my woman strength. I want my little Brother. Oh! I must clasp him in my arms and spare him from the horrible foe. ..oh. Pa, I never felt the war until tonight. I thought when my home was all broken up that our cup was full, but now the bitter drops are running over. I cannot write. How glad I am that we may pray.

Joseph Kern sustained a wound in his arm. He recovered over the summer in Farmville, and returned to fight again only to be taken a prisoner of war. Then, on August 10, John Kern died suddenly in Richmond. There is no family correspondence concerning this loss and its accompanying grief, which must have been profound. Further, George La Monte had been enduring the increasing strain of being a Yankee in an ambience which was growing increasingly hostile. All these stresses combined would have been factors in his

next decision. He opened the 1862-63 College session, but by early March of 1863 he had joined the faculty of the new Danville Female College, taking his family with him.

The destiny of Farmville Female College was now in the hands of Arnaud Eduard Preot. Born in Lille, France, on December 17, 1818, educated in Paris, he emigrated to New Orleans in 1837, when he was nineteen years old. According to his granddaughter, Margaret Hathaway Jones, who wrote a short biographical sketch based on the few published materials available and her mother's recollections, he had left his native land because,

the uncle with whom he was a favorite and who had planned to leave him all his worldly goods, married late in life and changed all this, whereupon he wanted his nephew to go into the priesthood, so Amaud ran away and came to America. All the English he knew were a few "cuss words" which he had picked up from the sailors.

He is described as having "... brown hair, beard and eyebrows, blue eyes, an aquiline nose, and an oval visage"("Idler's Column" n.d.).

From New Orleans, he traveled north and became a teacher at Walkhill Academy in Pennsylvania. A superb linguist and a talented musician, he quickly established himself as an excellent teacher. A letter of recommendation from Walkhill's principal, Mr. P. Roberson, dated October 18, 1843, says of him,

He possesses good natural talents, a thorough acquaintance with his own language. . . and a happy faculty in imparting to his pupils a knowledge of the pronunciation of the French. He is hereby very cordially commended to the confidence and esteem of all who know how to appreciate character, talent and industry and are disposed to give them encouragement.

Mrs. Jones says that Preot next went to Southworth Academy in Petersburg, Virginia. There is no record of a Southworth Academy in that city; there was a Leavenworth Academy, and perhaps this is one of those situations where the memory plays tricks. He was definitely at Petersburg Classical Institute in 1845-46, and again in 1847. On August 9, 1848, he married Elizabeth Ann Hammatt of Fleet's Hill (now Ettrick). Again according to Mrs. Jones, his wife was "one of his music students," suggesting that he may have supplemented his income by giving private piano lessons.

Preot's next move, around 1850, was to the Buckingham Female Collegiate Institute, where he was named professor of music, art and languages. He was one of the most popular members of the faculty, remembered for the "many romantic songs and sprightly dances" which he composed (Jones). Then, for some unascertainable reason, the Buckingham Institute began to fail around 1858; it would close in 1863. Whether Preot applied for a position at the Farmville Female College, or whether President La Monte ever on the lookout for a means of improving his institution invited him to Farmville, is unknown; however, in 1860, La Monte announced the appointment of an "...eminent Pianist and distinguished Linguist" to the faculty. When La Monte left, Preot was his obvious successor. In the Christian Advocate(Richmond, Virginia) of February 19, 1863, the following announcement appeared;

The trustees announce the organization of this institution (Farmville Female College) with the following instructors:

A. Preot, President

Rev. R. W. East, Ancient Languages

Rev. William Judkin, Mental and Moral Philosophy

Mrs. S. V. East, Mathematics and the English Branches

Mrs. A. E. Preot, Music and French

Mr. Preot is well known as a faithful and excellent instructor in Music and Modern Languages. His family will have charge of the boarding department.

Preot's teaching methods and philosophy were considered "out standing" (Jones), and his contribution to higher education was recognized throughout the state. Bradshaw notes that, at a teacher's convention held at Petersburg on December 30-31, 1863, "Professor A. Preot of Farmville College served on the Modern Languages Committee" (391). He continued the high standards instituted by George La Monte. The 1864—65 REGISTER contains the following testimonial:

The Trustees take pleasure in testifying to the faithfulness and ability of the Board of Instruction; and they feel well assured that their confidence in the teachers has not been misplaced. They, therefore, recommend this Institution to the patronage of parents and guardians (12).

The faculty had been enlarged; the Reverend George H. Gilmer taught Moral Science, the Misses Emma J. Turner and Bettie A. Thackston taught English, and Miss Bettie Prichard, music. Mrs. East, who in 1863 had taught both English and mathematics, now taught mathematics exclusively. The Preparatory and Collegiate Departments continued unchanged, but Preot did follow the Con tinental tradition familiar to him and instituted a three-year degree program for students who came thoroughly prepared to do collegelevel work.

All students seeking the Mistress of Arts degree had to achieve certificates of proficiency in the various disciplines, and, judging from the course offerings, the requirements had been tightened. There were "optionary" courses but these might be pursued only after the requirements were met. Six terms of English language and literature, six terms of French, six terms of Latin, three terms of Algebra, two terms of Geometry, and one term of Trigonometry were twt "optionary," though Mensuration was. Three terms of Roman History and two terms of Ancient Geography had to be completed, as well as one term each of Natural Philosophy, and chemistry. Mental and Moral Philosophy, Evidences of Christianity, and Logic completed the list. French was the required modern language, though Italian and Spanish might be opted for in addi tion. The continued emphasis on "Reading, Writing, and Spelling," and the semi-monthly essav requirement were retained (1864^65 REGISTER 9).

The grading scale was identical to that of the La Monte regime. Students and parents were warned, however, that a perfect 5". . . will occur exceedingly seldom, as it requires a perfect recitation in even/ subject every day"(1864-65 REGISTER 9). Most students were prob ably overjoyed to receive an "excellent" 4! They were judged "Deficient, when an average is less than 3y4," and "they are required to study that subject again" (REGISTER 9). The music requirement, as might be expected, remained unaltered and proba bly strengthened, if the following statement of President Preot is any indication:

To become an intelligent, correct, and tasteful performer, it is deemed indispensable for the student in Music to rely more on the musical training and education of the mind than on what is termed "an ear for music." The latter will almost invariably result from the former (REGISTER 8).

For the boarders, the "home atmosphere" continued unchanged, as the 1863 advertisement maintained:

The President and his lady will have charge of the Boarding Department and supervise personally all arrangements for the comfort and well being of the pupils whether in sickness or in health. They will regard and treat the young ladies as members of their own family, and, together with the other teachers, will strive to render them happy and content, and will not fail to protect and advise them whenever necessary.

The discipline, though rigidly enforced, will not be burden some. The rules are few and will tend to the moral, intellectual, and physical welfare of the students(REGISTER 10-11).

The convenience of the "physical plant" was noted:

The communications between the young ladies' rooms, the parlors, the dining room, school room, and recitation room are such as to avoid all exposure, even in the most inclement weather. The music rooms are in separate buildings, where practicing will neither interrupt nor be interrupted (REGISTER 10).

Finally, fees for one term, "invariably in gold or its equivalent" were payable in advance: board,including washing, was S64; tuition including music and languages, plus 33.00 for "incidental charges" came to $63. And as before, students furnished their own towels, sheets and pillowcases, "... and a spoon to use in the room" (REGISTER 11).

The College had grown during the La Monte years; the 1864-65 REGISTER lists a student enrollment of eighty-seven, plus twentyseven Latin scholars, fifty-eight French scholars, and sixty music scholars seeking certificates of proficiency in their respective disci plines. And students continued to enroll. It is surprising to note how little the War intruded. Only scattered references in the 1862 La Monte correspondence revealed that the students knitted and hemmed sheets and pillowcases, and probably rolled bandages as well, for the Confederate General Hospital, which had opened in 1862 for ". . . cases of chronic disease and convalescents from the hospitals in the cities and others near the field of active operations" (Wall 195). That same summer, refugees ". . . from Richmond and Winchester, and some from Warren, New Kent, and Caroline Counties, then the scenes of hard battles and marching armies" (Bradshaw 387) began to arrive in Farmville, many of whom found

temporary shelter at the College until the students returned for the fall term. Troops came through occasionally. But the greatest problem was the steadily growing food shortage, and the inevitable increase in prices. Bradshaw notes that prices "... in September 1863. . . were flour, S25 a barrel; bacon, SI a pound; molasses, $50 a barrel; coffee, S12.50 a pound;tea,87a pound..."(390). By March 15, 1864, flour was quoted at". ..SlOO a barrel; bacon,$7 a pound; molasses, S50 a barrel; coffee, S12.50 a pound"(390). However, as Bradshaw continues.

These were not the peak prices. Flour sold in Farmville for $1,000 a barrel. Most of the commodities listed were impossible to obtain. . . Parched wheat, rye, or sweet potatoes were used to make coffee. Tea was hoarded for use in sickness; sassafras root tea took the place of tea in general use. .. Medicine was hard to obtain, and some kinds could not be gotten; people had to fall back on herbs, both wild and cultivated. . . The cost of clothing was so high that few could buy it, and fresh impetus was given to spinning and weaving of cloth in the farmhouses (391-2).

(An early, rather amusing indication of the clothing shortage is found in a letter from Tille Kern to her father, dated May 22, 1862, begging him to send her a corset, "size 22 or 23," which was "indispensable" to her.)

Ultimately, the War in all its fury and tragedy reached Farmville itself. An eye-witness account of the effects of the last battle and the Confederate retreat survives in an article by Mary Lynn Williamson in HARPER'S WEEKLY, dated July 10, 1909. Mrs. Williamson, in April 1865, was Mary Lynn(Minnie) Harrison of Albemarle County. Her article entitled "The Chivalric Side of General Grant" is, as might be expected, highly partisan, but it remains an invaluable resource. She does not mention the events immediately preceding April 6, 1865, which would have been for many people both in the south and in the north within living memory in 1909, and they should perhaps be briefly recapitulated for 20th century readers.

General Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia had held the cities of Richmond and Petersburg and the intervening territory throughout the winter of 1864-65. However, the Federal Forces commanded by General Ulysses S. Grant had managed to outflank Lee at Petersburg, and had soundly defeated the Confed erate defenders at the Battle of Five Forks on April 1, 1865. Lee, recognizing that he could no longer hold Richmond, began what he

had hoped would be an orderly retreat, planning to rendezvous with General Joseph E. Johnston, a native of Prince Edward County (who was himself retreating through North Carolina pursued by the cavalry of Major General William T. Sheriden) at Amelia Court house. The Confederates marched without rest—or food. Ironically enough,"The storehouses of Richmond, Petersburg, and Danville were full of supplies, but with a system bound hand and foot with red tape not a pound of it was available" (Wall 91). Lee's men lost valuable time searching'for food at Amelia, thus allowing Sheriden to cut them off at Jetersville.

It must be remembered that 1865 was not the era of "instant communication"; television did not record and relay nightly the news into the family parlor. Thus, the first inkling that the students at Farmville Female College had of impending disaster was the Confederate attempt in their retreat to destroy High Bridge, the scene of a carefree College outing only three years before. "On the 6th day of April 1865, rapid firing was heard in the direction of High Bridge, and ere long it was known within the college that General Lee's army was in full retreat, closely pursued by the hosts of Grant" (Williamson). But the attempt to destroy the bridge only partially succeeded, and the armies had confronted each other at Sailor's Creek on April 7. Surrounded on all sides. Lee's men fought and finally again retreated in the only possible direction, straight through Farmville.

Great was the consternation which prevailed among the fourscore girls within the college walls. All school operations were discontinued, and the evening was passed in watching the vanguard of the weary, starving Southern army march by. Not a few soldiers stopped long enough to speak to sisters and friends and bid them be courageous, as it was evident that they would soon be in the hands of the enemy. All night long, the rumble of wheels and the sound of marching feet could be heard;and the next morning. . . the weeping girls bade farewell to the Army of Northern Virginia, as they saw a squadron of the First Virginia Cavalry dash by at a gallop, bridle reins on the necks of their horses, and firing backward as they went. Behind them, out of the mist, rode the advance guard of the splendid legions of Sheriden. Minie balls fell about the building—one crashed through a window where several girls were standing and, when they had recovered from their panic, their friends in gray had vanished like the phantom of a dream.

On came Sheriden. For hours the girls, benumbed by grief

and fear, stood gazing at the wonderful spectacle. The men on their fine, well fed horses and clad in their winter overcoats and big hats looked like giants. The mist turned to rain, but,looking neither to the right nor to the left, the columns moved on to the music of their magnificent bands (Williamson).

The terror of the students was unimaginable. Not only did they watch ". . . the Federals marching on in a never-ending stream by day and by night until, as far as the eye could reach, the country around was one vast camp," but also, "... several regiments of black troops had been encamped in the rear of the college." It was their shouting and cheering on the night of April 9th that an nounced Lee's surrender at Appomattox Court House.

The immediate consequence in Farmville was the establishment of marshal law. Bradshaw gives the comment of Dr. W. H. H.Thaxton: ". . . as a rule, the conduct of Yankee officers and real soldiers was better, more creditable, and more honorable than expected; campfollowers, thieves, and plunderers invaded every house not pro tected by guards, stealing and hunting for what they thought was concealed" (409). The College was unmolested, but the students must have felt as though they were under siege. Further,"Each day their meals became scantier and poorer in quality, and they were told that supplies of the storerooms would soon be exhausted" (Williamson). Then, after two days of waiting, help came from a most unexpected quarter. General Grant, escorted by Sheriden's cavalry, returned to Farmville on April 11 (Bradshaw 412).

. . . he had heard of their(the students') distress, and sent an officer to the college with an order for each one of these students to be passed, free of charge, to her home,or anywhere else in the United States where she might find friends. This order seemed to be a mockery just then, for the Southside Railroad had been torn up and rolling stock burned, and there seemed no other way of getting to the James River. But a few days after word came from the provost marshal, who had in mind General Grant's order, that the last wagon train of the army would move towards Burkeville that afternoon, and that those who wished to reach Richmond could get to the railroad in these wagons.

The principal. . . favored the scheme, and in a few minutes twenty-six were on their way to the wagon train. The girls knew that they were running from Scylla into Charybdis, but they were hardly prepared to find in each of the wagons a dis-

mounted [Confederate] cannon. . . These munitions of war were the only seats provided, their being neither straw nor hay in these rough wagons. One of the girls exclaiming at the unique seat, the driver said,"Can't yer ride on one of your own guns?" ... These young people had eaten nothing since the scanty breakfast that moming,and each had with her only two small rolls of sour bread (Williamson).

The harrowing journey took three days. The first night, they stopped at the deserted house of a Mr. Watkins.

The young girls were conducted to a room which proved to be the parlor of the mansion, and were informed by a polite officer that they would be entirely safe, and that they would make an early start in the morning. The parlor had been stripped of all its furniture save a Brussels carpet and a divan. The sick girl of the party was placed upon the divan, and the others rested as they could best dispose themselves on the floor.

The next overnight stop, at a hospital in Burkeville, was a little more comfortable; at least there were bunks and blankets but still no food.

The next morning, the lieutenant sent in a small paper sack of "hardtack" which, with water for a beverage proved a great treat. Having a little specie, they made quite an effort to buy something to eat before setting out again but found nothing for sale; the citizens had not enough for their own necessity and the rations of the Union forces were very scanty.'

The train trip to City Point could only have exacerbated their realization of "The Cause's" total defeat.

The coaches were old and rickety and threatened each moment to collapse. .. The coaches in which the girls were seated were filled with Federal officers resplendent in epaulets, stars, and gold braid. Outside the car windows on all the country roads could be seen wagon trains, artillery, and soldiers on the march. The Southern girls, in their gypsy-like attire— each one being a fashion to herself—wearing homemade hats, pieced-out dresses, and calfskin shoes, were great curiosities for the well-groomed and dashing soldiers of the North. Some of the latter tried to "make conversation," but the girls were too proud and too sore hearted to respond.

Then, just outside Petersburg, the "boiler of the ancient engine burst," and all the passengers had to walk the rest of the way into town.

Another day of fasting, fatigue, and terror had not improved the condition of the travelers;indeed,it was with great difficulty that they followed their conductor to the office of the provost marshal. There the orders of General Grant again proved an "open sesame." They were very soon conducted to the wharf and put on board a fine new steamboat. Then they were placed in the charge of a stewardess, who led them to nice staterooms. After resting and making fresh toilets, they supped sumptu ously at Uncle Sam's expense;and afterwards gathered strength to pace the deck and view the busy and beautiful scene presented by the shipping gathered there to receive the legions of General Grant (Williamson).

The next day, aboard another steamer, they were on their way to Richmond, where they arrived that same evening. General Grant's safe-conducts must have been honored thereafter as well; we know at least that Mary Lynn Harrison Williamson reached her home in Albemarle County.

There is no information concerning the other students at the College. Probably the majority were from Prince Edward, Cumber land, and Appomattox Counties,so their safe return home could be accomplished more easily. But Federal troops remained in the area for six weeks(Bradshaw 417),"eating off the land." That the College remained in session at all was miraculous under the combined circumstances of little food and the bitterness of Reconstruction politics, ".. . unequaled before or since in Prince Edward history" (Bradshaw 435). That the College did remain in session is evidenced by the report card of Miss Mary Chappell for April 10-June 25,1868, which survives in the Longwood College archives. Miss Chappell during that term pursued Algebra, Geometry, Latin, French, En glish Branches, and Music, and her highest grade was AVa. Evidently the standards of demonstrated proficiency remained unaltered.

In 1869, Arnaud Preot resigned as Farmville Female College president, and took his family to Danville, where he joined his friend George La Monte at the Danville Female College. There is no reason given for this decision, but probably the strain of holding the Farmville College together had taken too great a toll. When Danville College closed, he went on to the Roanoke Female College to become its president, where he dies on June 17, 1873. Burdened by

the harsh realities of the immediate situation, the town and county must have given Farmville Female College little hope of survival. But apparently, the same will and courage that had inspired the incorporators of the Female Seminary was aroused in the members of the College Board of Trustees, and they refused to abandon an institution which had proved to be both valuable and important without a fight.

—- he years between 1869 and 1873 were the Farmville Female College's truly "dark years," and we have only glimpses of the activities at that time. In 1870, the president was S. F. Nottingham. In the NEW COMMONWEALTH of January 12,1871, the following advertisement appeared:

The undersigned have purchased the College property, and with much gratification announce the services of the Rev. FJrands Marion] Edwards have been secured in the capacity of President. Young ladies schooled in the Colleges of our land and experienced in teaching are associated with him,so that the institution is now prepared to lead pupils through as thorough a curriculum as can be had at any similar school.

President Edwards, by profession a teacher before his en trance into the ministry, enjoyed a high reputation as a success ful instructor of youth. His experience as a scientific lecturer has been extensive.

Payments to be made semi-annually or monthly in advance. ]. D. Crawley, R. S. Paulette, J. T. Gray, W. G. Venable, T. J. Davis, J. W. Gills, H. E. Warren, stockholders.

The college administration changed hands again, when the Rev erend James D.Crawley took the presidency in 1873, of whom it was said, "As a teacher, he was patient, thorough, painstaking, and many hundreds of people owe their success in life to his faithful ness"(Richmond CHRISTIAN ADVOCATE, June 28, 1888).

But the financial situation of the College was precarious at best, suffering as did all institutions of higher learning from the post-war depression. According to Shackelford, ". . . at a meeting held on July 1, 1870, the stockholders decided to sell the college property, and after paying off the debts, distributed the proceeds among themselves"(7), but it took two-and-a-half years to find a buyer. The property was sold to Garnett and Martha Bickers on February 6, 1873. Bickers made no effort to run the College; as a businessman, he acted as a "holding agent," once again demonstrating the community's faith in the institution and their desire to see it continue. The manner of that continuance has been a matter of some debate; one historian notes that, "Apparently after being closed for several years, the school was revived in 1875 when it was incorpo rated as Farmville College by the Prince Edward County Circuit Court. The sponsor of the revived school was the Methodist Conference, and its president was a Methodist minister, Paul Whitehead" (Schlegel, 4). However, the FARMVILLE COLLEGE CATALOGUE, 1875-76, states that the buildings ". . . were pur chased in 1873 by citizens of the town,chiefly Methodists"(9). If this was, in fact, a repurchase, it certainly represents a consummate act of faith, considering the devastation caused by the panic of 1873, described as "... one of the major depressions and financial crises in the nation's history . . ." (Bradshaw 529). Bickers still held the title to the land which is doubtless the explanation of a debt of $3,050 which was not repaid until 1882.

That "citizens of the town, chiefly Methodists" had attempted to interest the Methodist Virginia Conference in taking over the College as one of their educational institutions, probably several years before 1873, is evidenced by the minutes of the CONFER ENCE EDUCATION REPORT for 1873, which note the following:

The communication from the owners of the buildings occu pied by this College [Farmville Female] was referred to a special committee, whose report was adopted as follows:

Resolved 1st: That while we highly appreciate the generous offer by our friends of the Farmville Female College buildings, we do not feel prepared at this time to assume any further responsibility in regard to institutions of learning, and therefore most respectfully and affectionately decline said offer.

Resolved 2nd: That we rejoice in the favorable auspices under which Farmville Female College has opened, and wish for it a long and ever widening sphere of influence.

Resolved 3rd: That we most cordially commend it to our people as in hearty sympathy with our Church and in every way eminently worthy of their patronage.

The "favorable auspices" of the second "resolved" can only refer to the arrival early in 1873 of the new president, the Reverend Paul Whitehead. Whitehead (1830-1906) was a native of Nelson County, and was considered ". . . one of the first minds of the Virginia Conference"(EDUCATION REPORT 1873). He had been formally admitted to the Conference in 1853, and was named Clerk of the Conference in 1860, a position he would hold until his death. For twenty-five years, he served as Presiding Elder. He was also an experienced administrator: "Associated with him are the same faculty who, under his presidency, earned for the Wesleyan Female College at Murfreesboro a high reputation"(EDUCATION REPORT 1873). His presence was sufficient reason for a glowing endorsement from the Conference, even though the hierarchy had declined to take possession of it.

Last but not least, the youngest of our Female Colleges, is that just opened with favorable auspices by the Rev. Paul Whitehead in the town of Farmville. . . Farmville, in the centre [sic.] of our territory on the Southside Railway,in a healthy and beautiful section of the State, with an intelligent and refined population seems excellently to be adapted to be the seat of a first-rate College; and the name of Paul Whitehead at its head is sufficient guarantee that this will be an institution of the first class(EDUCATION REPORT 1873).

Despite financial difficulties, the College completed a successful academic year, and the first Commencement exercises of the Whi tehead regime were held from Sunday,June 28 to Wednesday,July 1, 1874. The Baptist and Methodist churches cancelled their Sunday morning worship services so that members might attend ". . . the commencement sermon at the College which was delivered by W.

Longwood College: A History

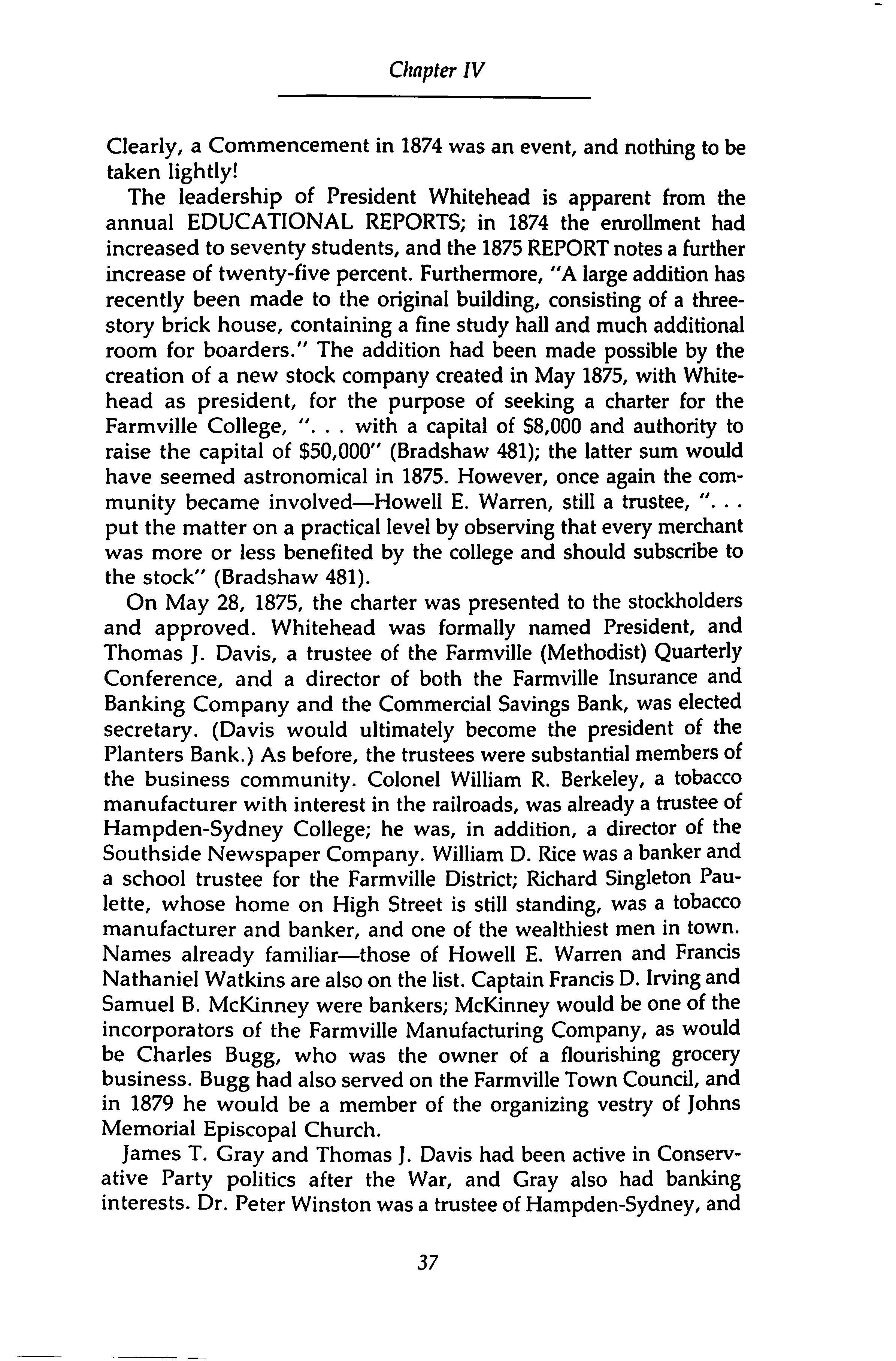

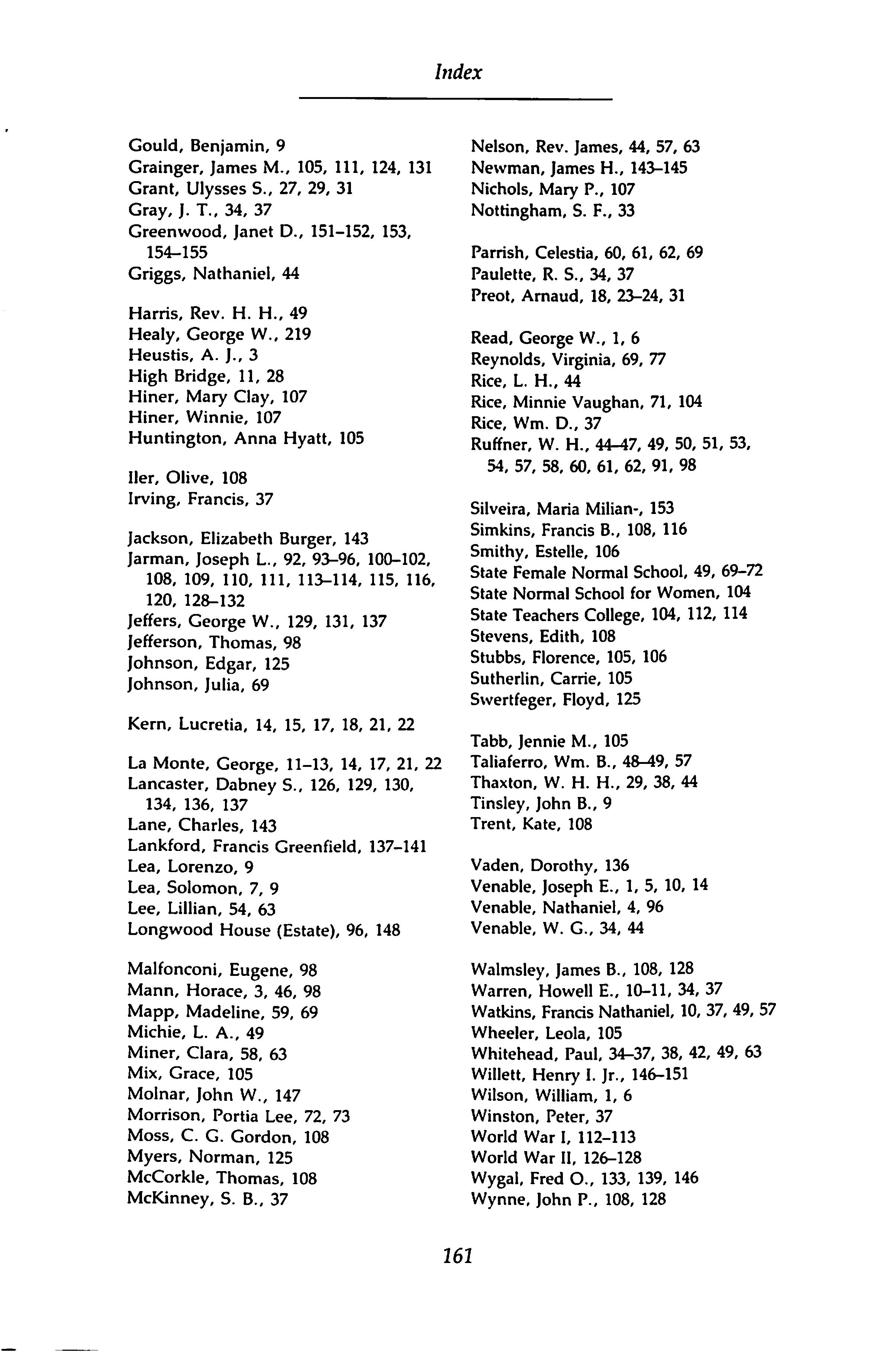

y^VRM Vll,l,F., irittUINlA.

/j» Alfif ^k4*9/ tit ^d

t4t tut tuttttnU, ^o d/utly dtt^/tclt

tttt^taett/ta tati/ iSttutt tttt^ei dttt AatuA /Att ^'*.ji.vr^ An^ ^:£- Jif,."

{■tofnatrsf ^>r, ^ ■/'/A/^ " /y ) PraitaiC

1880 Certificate

W. Bennett, editor of the Richmond CHRISTIAN ADVOCATE" (Bradshaw 490). There were two student organizations: The Cecilian Society which held "A soiree , . . once a fortnight, the program of which comprises classical music and the highest order of more recent compositions, calculated to elevate the taste," and the Mar garet J. Preston Literary Society, ". . . a voluntary association of students for literary culture" (1875-76 CATALOGUE 23). Accord ingly, the Cecilians entertained on Monday evening, and the Prestonians on Tuesday evening, both events, of course, open to the public. And on Wednesday morning, July 1, the Misses Lalla T. Saunders of Farmville and Alice E. Custis of Acromac County received their degrees.