Pushing the limits of what’s possible

Explore more solutions at MarinoWARE.com/RethinkSteelFraming

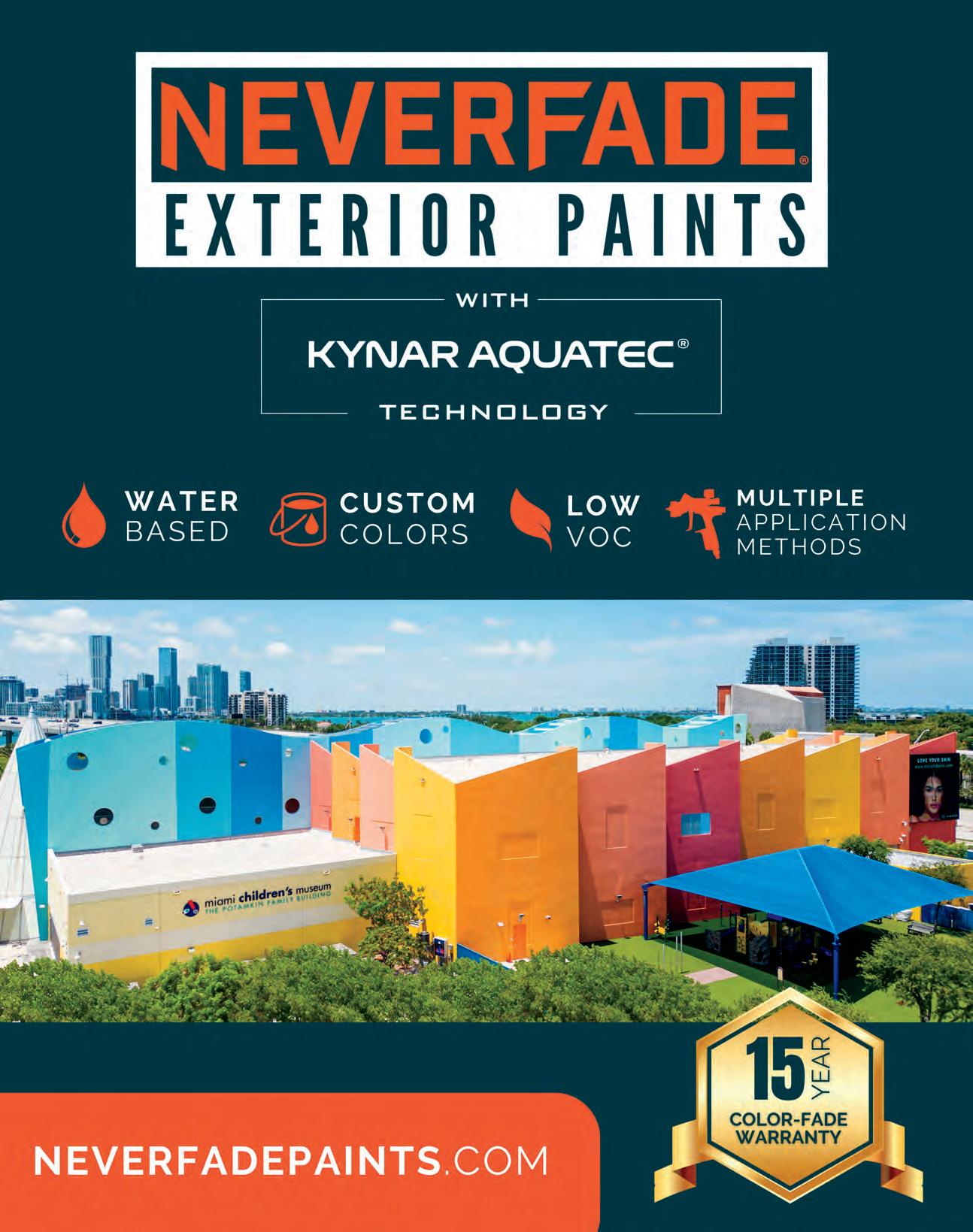

SOUNDGUARD ® | Designed to easily construct narrower, more economical interior non-load bearing partitions, SoundGuard delivers high STC ratings.

STUDRITE® | Engineered with lip-reinforced knockouts, StudRite’s design increases structural performance and reduces sound transfer through the wall.

HOTROD® XL | FIRE-RATED DEFLECTION BEAD

A surface mounted fire-rated deflection bead tested to UL 2079, HOTROD XL provides 1 hr and 2 hr joint protection, is sound tested according to ASTM E90, and does not harden over time.

PG 38

Connected Door Entry

Long-lasting, flexible tech solutions are an upgrade from basic intercoms.

PG 76

Proven Performance

How insulation makes an impact on design, not the environment

PG 90

The Beauty of Mass Timber Cutting emissions and spurring more carbon sinks

VOLUME 16 | SPRING/SUMMER 2025

PG 98

Future-Proofing

A sustainable future means making continuous improvements that support client goals.

PG 120

Verifiable Vision Transparency is the new currency in sustainable construction.

PG 136

Health Care Design for Everyone

CannonDesign on designing the new Petrocelli Surgical Pavilion on Long Island

PG 140

Door to Success

Technology is improving privacy, acoustics, flexibility, and sustainability in health care.

PG 254

Evolving Outdoor Living Demand for customizable products and unity between inside and out

PG 260

The Future of Turf is Circular

The shift to high-performance, low-impact synthetic grass

PG 266

Low-Maintenance

Luxury

The benefits of porcelain pavers in elegant outdoor spaces

PG 272

The Power of Structural Steel

New possibilities with increased strength and more

PG 280

The Artistic Authenticity of Terra-Cotta

A timeless building material made by hand meets higher ed needs and more.

PG 13

Editors’ Picks

The look and feel of stone

PG 18

Taking the Heat

Exploring fire-retardant-treated wood

PG 24

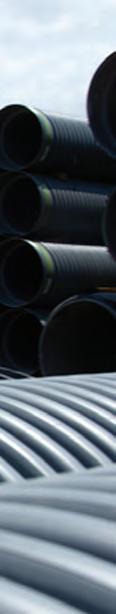

Smarter Stormwater

Good water infrastructure accounts for the future.

PG 30

A New Standard in HVAC

Creating new paths to efficiency, adaptability, and accessible comfort

PG 44

Strong Roofing

A long life cycle and recyclability are key to PVC roofing.

PG 52

Sealing Sustainability

Curbing energy waste with air sealing

PG 60

Cold-Formed Steel Construction industry needs and pushing the limits of what’s possible

PG 68

Certifiably Sustainable Evolving certifications are reframing building design.

PG 82

Above-Ground

Plumbing

An efficient and cost-effective alternative for many applications

PG 106

Insulating for the Future

Choosing the right insulation for the environment and for occupant health

PG 114

Helping Manufacturers

Get Greener

How certifications and code compliance drive sustainable innovation

PG 128

The Evolution of HVAC Electrification and the rise of all-electric buildings

PG 146

Controlled Comfort Inside changing hospitality expectations

PG 154

Accessible Bathrooms Where design meets functionality

PG 162

Classrooms for the Future Intentional furniture design is reshaping educational spaces.

PG 172

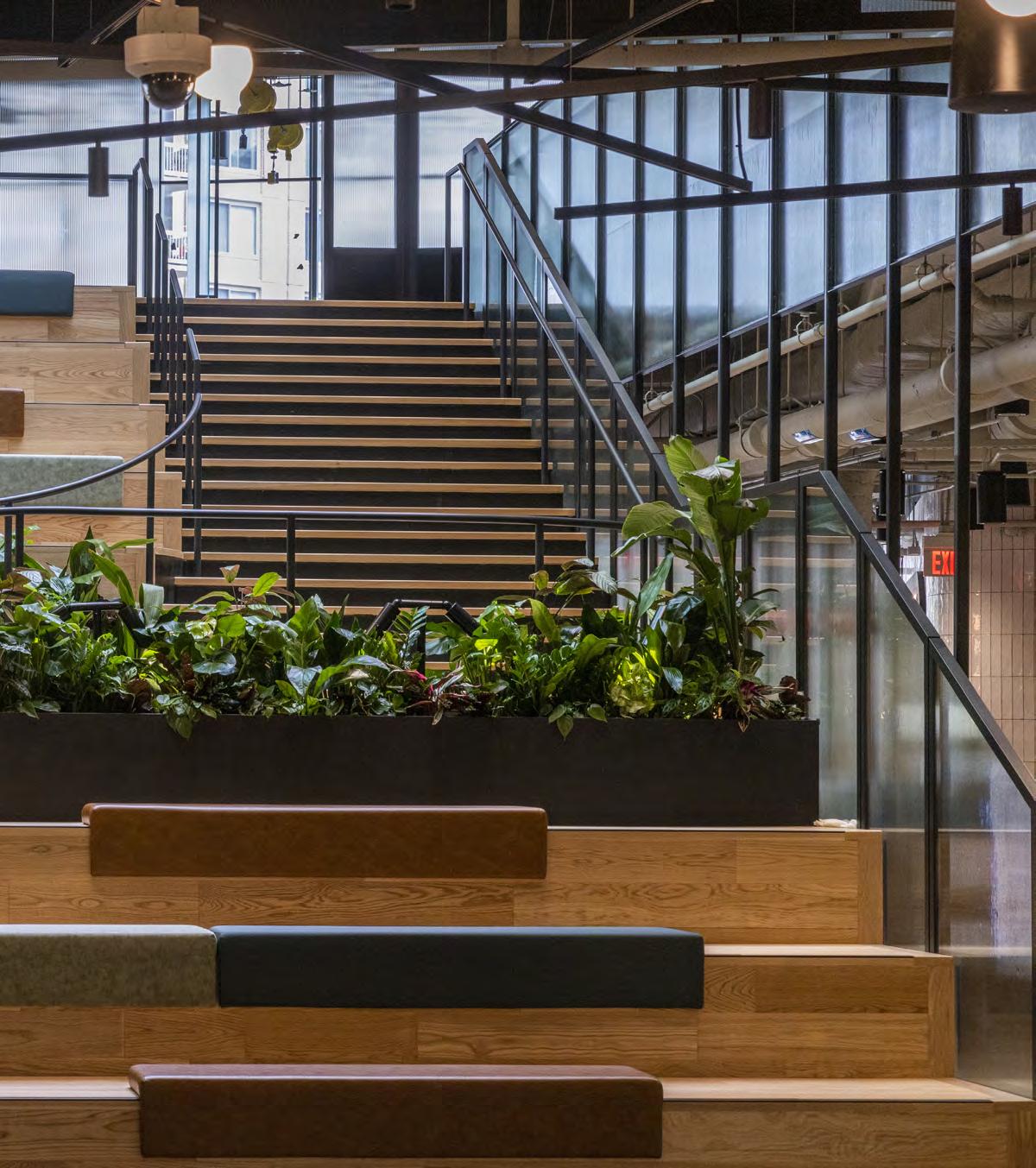

Setting Sustainability Standards

Lessons from Amazon’s HQ2 in Virginia, using climate-friendly solutions at scale

PG 178

Safe, Secure, & Smart

How office storage technologies and access are changing

PG 184

Persuasive Placemaking

The challenges of modern workplace design and where furniture fits in

PG 194

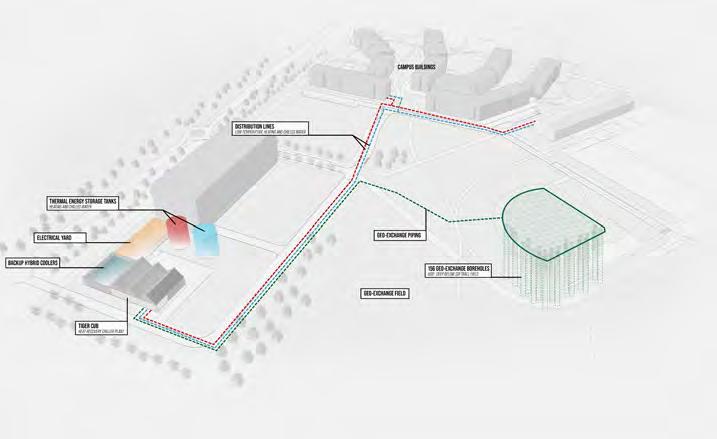

Princeton Utility Plants ZGF reimagines the humble energy building.

PG 200

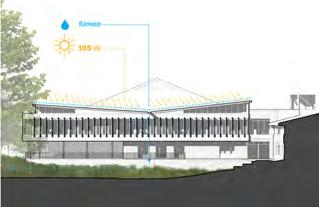

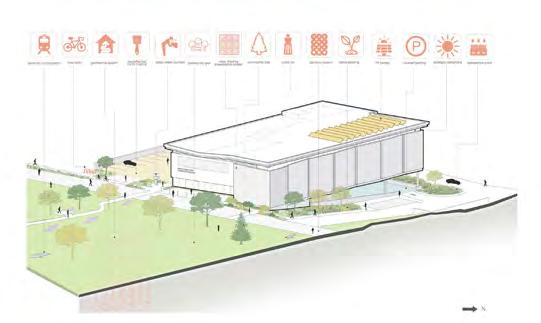

Collaboration and Cross-Pollination

A net-zero project generates at least 100% of its own energy.

PG 206

A New Cultural Destination

The SOM-designed Mulva Cultural Center in De Pere, Wisconsin

PG 212

Designed to Delight Donelson Library in Nashville is a nod to the area’s mid-century heritage.

PG 218

Aro Homes

New, design-forward, and sustainable path for infill residences

PG 224

One Heart

An affordable housing development in San Francisco’s Outer Mission

PG 234

City in a Forest Metropolis meets oasis in Georgia’s capital city

PG 236

More Than a Path

Atlanta’s Beltline is an inspiring greenway that continues to evolve.

PG 242

Hospitality Living

Scout Living at Ponce City Market brings the comforts of home to flexible stays.

PG 246

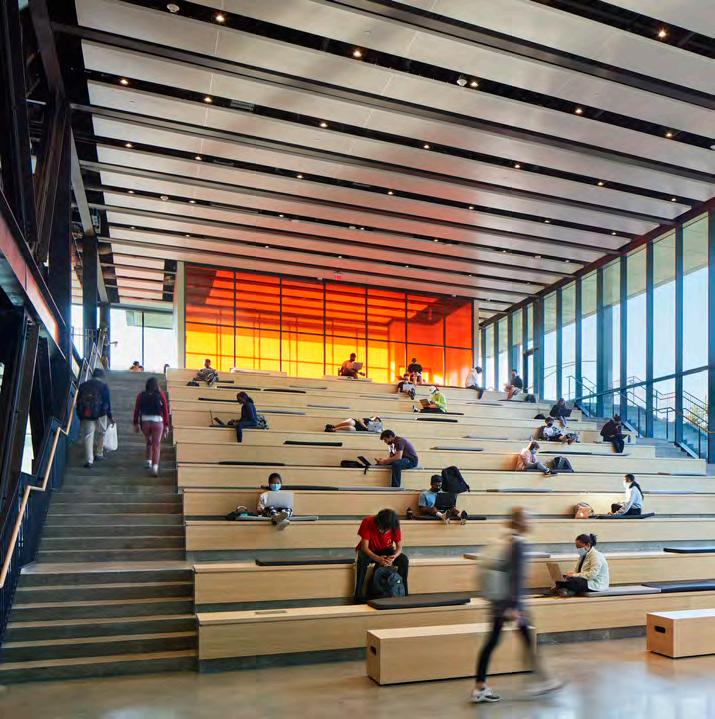

New Beginnings

Establishing connections between Spelman College and the Westside Atlanta community

PG 250

In Nature

Inside the Biophilic Leadership Summit at Serenbe, just outside Atlanta

PG 287

Preservation

Reducing material use while respecting the authenticity of historic buildings

PG 292

Collaborating to Reduce Carbon SOM’s in-house Sustainable Engineering Studio transforms project outcomes.

PG 296

Decarbonizing

Landscape Architecture

A blueprint in SWA’s Climate Action Plan and a call to action

Editor-in-Chief

Christopher Howe

Associate Publisher

Laura Howe

Managing Editor Laura Rote

Designer Michael Esposito

Content Marketing Director Julie Veternick

Content Marketing Manager Colette Conway

Contributors

Timothy Anscombe-Bell, Gerdo Aquino, Andrew Biro, Lark Breen, Michael Chalmers, Sophia Conforti, Rachel Coon, Amber Corrin, Valerie Craven, Christina Dean, Ashley D’Souza, Lauren Gallow, Pauline Hammerbeck, Elyse Hauser, Nicole Javorksy, Russ Klettke, Nancy Kristoff, Emma Loewe, Keith Loria, Beth Luberecki, Ian P. Murphy, Mikenna Pierotti, Haniya Rae, Emy Rodriguez Flores, Ben Schulman, Matt Watson

ONLINE

gbdmagazine.com gbdmagazine.com/digital-edition

SUBSCRIPTIONS

Online shop.gbdmagazine.com

Email service@gbdmagazine.com

gb&dPRO

Online gbdmagazine.com/gbdpro

Email info@gbdmagazine.com

Green Building & Design

47 W Polk Street, Ste 100-285 Chicago, IL 60605

Printed in the USA.

© 2025 by Green Advocacy Partners, LLC. All rights reserved.

Green Building & Design (gb&d) is printed in the United States using only soy-based inks. Please recycle this magazine.

The contents of this publication may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the consent of the publisher. The publisher is not responsible for product claims and representations.

The Green Building & Design logo is a registered trademark of Green Advocacy Partners, LLC.

PAULINE HAMMERBECK

(“Certifiably Sustainable,” pg 68; “Verifiable Vision,” pg. 120) is a freelance writer and editorial consultant based between Chicago and Milwaukee, covering everything from package design and retail strategy to real estate and the built environment. She lives in an American Foursquare and has strong thoughts about Brutalism.

TIMOTHY ANSCOMBE-BELL

(“The Evolution of HVAC,” pg 128) is a Los Angeles–based design consultant who has spent his career collaborating with architects, developers, and leading manufacturers on the creation of healthy and sustainable interior spaces. He moved from London to LA in 2023 and today works on green building projects across the US. He also writes for international publications about the intersection of health and sustainability within global architecture and design.

NANCY KRISTOF

(“Understanding Above-Ground Plumbing,” pg 82) is a Denverbased freelance writer with more than 30 years of experience working within and writing about the built environment. Her words have been published in online and print magazines devoted to mechanical engineering, architecture, design, and more.

1

As sustainable rehabs and historic preservations become increasingly popular, design professionals have the opportunity to integrate vintage architectural features with contemporary design motifs to create original spaces that don’t necessarily conform to current trends. “I think authenticity is so important when designing spaces for people,” says Sara Agrest, design director and senior associate at Spectorgroup. “We don’t need to add extraneous materiality or become beholden to passing trends.”

Sustainable Historic Preservation, pg. 288

As technology evolves, it’s important to keep some traditional features, like physical buttons on a modern intercom system. “Everybody loves mechanical buttons,” says Robert Bhiro, Comelit’s vice president of sales. “Having a tactile button that you press every time you do something—it sounds silly, but it’s something that is universal for everybody.”

Connected Door Entry, pg. 38

3

Amazon’s HQ2 in Arlington, Virginia, has eight occupied terraces and more than two acres of green roofing and landscaping. These green roofs help reduce energy consumption by swapping synthetic, impervious materials with plant life, according to Amazon’s director of workplace innovation and sustainability. While conventional roofs and pavement absorb sunlight and convert that energy into heat, warming the surrounding structures and putting greater strain on the HVAC system, green roofs and landscaping mitigate this through the naturally cooling functions of plants, reflecting solar energy and off-setting heat through evaporation. Setting Sustainability Standards, pg. 172

4

CannonDesign is no stranger to huge projects. Leaders from the recent Petrocelli Surgical Pavilion on Northwell Health’s flagship Long Island campus emphasize the importance of continuity in long-term work. Institutional projects often take longer than other commercial projects, said CannonDesign’s Dale Greenwald, and Northwell was a 10-year project. “People come and go and you still have to develop and create a framework and a vocabulary,” he says. “You have to continue … to get to the outcome that was initially intended. There’s a level of complexity that is added as the project timeframe gets longer.” Health Care Design for Everyone, pg 136

“Greenways are really important infrastructure that we need to be building; they’re one of the ways that a city is connected to its place in the world,” says Ryan Gravel, an urban designer based in Atlanta whose master’s thesis led to the now widely used Beltline. Greenways are often along waterways or other natural routes that are part of an area’s topography, history, and culture, providing connectivity for people, nature, and wildlife. Beyond the Beltline, Gravel is inspired by projects like the Washington, DC 11th Street Bridge Park, which aims to utilize abandoned infrastructure—a set of piers from a now-defunct vehicular bridge—to create a pedestrian link between east and west. The project is ongoing. More Than a Path, pg. 236

A truly circular solution transforming manufacturing waste into new acoustic product accessories. From Spinfix™ to End Caps and Vicinity™ Workstation Clamps, we’re taking responsibility for the impact our products have on the planet at every stage of their lifecycle.

BY ANDREW BIRO

Architects, engineers, urban planners, and other building professionals are increasingly adopting regenerative design principles to create buildings, sites, and systems that actively replenish resources and rejuvenate the landscapes in which they are embedded.

In ecology, regeneration describes the process by which an organism or ecosystem suffering from damage or degradation recovers and restores its equilibrium over time. From a development standpoint, regenerative designs are engineered to give back more than they take by mimicking the restorative biological systems found in nature.

“Regenerative design in its simplest form is design that goes beyond sustainability with the mantra of ‘do no harm,’” Don Haynes, EHS and sustainability manager for Florim USA, previously wrote for gb&dPRO. “It is based on holistic thinking and draws inspiration from systems and images found in nature. It aims to reconnect and realign humans and their activities with the natural environment, thereby reducing the negative environmental impacts of today’s society while addressing urgent issues

such as climate change, the lingering Covid-19 pandemic, and whatever may come next.”

The basic ideas behind regenerative design are nothing new; many regenerative strategies are fundamentally rooted in Indigenous practices and traditional ecological knowledge. The idea of “doing less harm” has long dominated the green building movement, but many in the field are coming to the realization that it is not enough to simply sustain current levels of planetary health.

“A majority of the conversation around sustainability in architecture has focused on mitigating environmental impact, i.e. producing less waste and doing less harm to the planet,” Henry Celli, an associate principal and senior architect at CBT, wrote in a previous gb&d article (gbdmagazine.com/regenerative-design-trends). “While this is a critical pillar of environmentally conscious design, our current climate crisis calls for more aggressive action.”

Regenerative design is that aggressive action, as it aims to create built environments with a net-positive impact on the natural world.

A whole-systems approach considers how environmental elements like climate, seasonality, annual precipitation, groundwater tables, prevailing winds, geographic features, animal and insect migration patterns, and soil composition might influence a design, and also begs consideration as to how existing sociocultural and economic factors will be impacted by the completed design.

Implementing design strategies that emulate the biological processes found in nature are crucial to transforming projects so they can benefit their communities. For regenerative designs to be truly integrated, they must replenish the resources they use. Green roofs seeded with native plantings, for example, help to restore native habitat lost as a result of development while helping to maintain biodiversity with birds, bees, and butterflies. These features also function as passive cooling systems by reducing solar heat absorption.

Certain technologies used to harness and store renewable energies rely on rare, finite minerals. For this reason regenerative design frameworks encourage an extremely high degree of energy efficiency to minimize operational energy requirements as a whole. Strategies like daylighting, natural ventilation, passive solar heating, air sealing, and insulation can all help designs drastically reduce their energy use, which in turn allows for smaller energy grids and fewer energy storage batteries, minimizing the need for new material extraction.

Building circularity into regenerative design starts with making responsible material choices. Materials should be durable, nontoxic, and have a low embodied carbon to ensure they remain in use for as long as possible without posing a threat. Making smart material choices enables these designs to be engineered with disassembly and adaptive reuse in mind. “Renovating, remodeling, and repurposing existing buildings almost always generates significantly fewer embodied emissions than new construction,” Haynes previously wrote for gb&dPRO.

For regenerative designs to be successful, they must involve people from a wide range of backgrounds—including those from the immediate community. This helps ensure equitable development, as it integrates values and needs of the existing community into the project and its future growth. “By integrating community needs into the design process, projects can address food security, housing affordability, and equitable access to resources,” Joseph Mamayek, a principal at SGA, previously wrote for gb&d (gbdmagazine. com/regenerative-design-climate-resilience/).

SGA is designing Innovation Square to have amenities like a café, fitness center, roof deck, conference and event space, and outdoor public seating.

The Innovation Square 3 project demonstrates how regenerative design can meet the needs of highperformance industries while advancing environmental goals.

9to5 Seating Pg. 184

9to5seating.com

310.220.2500

Advanced Drainage Systems Pg. 24

adspipe.com

800.821.6710

Condair Pg. 146

condair.com

866.667.8321

KI Pg. 162 ki.com

800.424.2432

Digilock Pg. 178 digilock.com

Aeroseal Pg. 52

aeroseal.com

877.349.3828

Autex Acoustics Pg. 68

autexacoustics.com

424.203.1813

Bestbath

Pg. 154

bestbath.com

800.727.9907

Comelit USA Pg. 38

comelitusa.com

626.930.0388

Hanover Architectural Products Pg. 266 hanoverpavers.com

800.426.4242

Hoover Treated Wood Products Pg. 18 frtw.com

706.595.9855

ICC Evaluation Service Pg. 114 icc-es.org 800.423.6587

Kawneer Company Pg. 120

kawneer.us

Knauf North America Pg. 76 knaufnorthamerica.com

317.398.4434

LG Electronics USA Pg. 128 lghvac.com

888.346.1923

Ludowici Pg. 280 ludowici.com

740.342.1995

Marino\WARE Pg. 60 marinoware.com

800.627.4661

Mid-Atlantic Timberframes Pg. 90 matfllc.com

717.288.2460

New Millennium Pg. 272

newmill.com

260.321.8080

Q-PAC Pg. 30 q-pac.com

904.863.5300

Special-Lite Pg. 140

special-lite.com

800.821.6531

TenCate Grass Americas Pg. 260

tencategrass.com

423.775.0792

Renson North America Pg. 254 renson.net

ROCKWOOL Pg. 106 rockwool.com/north-america 800.265.6878

USG Corporation Pg. 98 usg.com

SFA Saniflo Pg. 82 sfasaniflo.com 800.571.8191

Sika Corporation-Roofing & Waterproofing

Pg. 44

usa.sika.com/sarnafil 888-509-3350

Since 1888 Ludowici has offered the most uniquely beautiful, highest quality architectural terra cotta products to homeowners, architects, universities, commercial, and government clients. As simple as taking dirt, fire, and water, our clay products use ecofriendly materials from the earth and incoprporates zero-waste manufacturing—making our processes the most eco-friendly and environmentally responsible. Made in America with ASTM C1167 Grade 1 ratings, qualifying LEED credits, Build America Buy America compliance, and a 75-Year Material Warranty, our tile is the best choice in sustainability.

Travertine is a hallmark of classical architecture, celebrated for its elegance and strength, with warm tones and distinctive veining that make it timeless. Trail reinterprets travertine’s beauty in two aesthetic expressions. The result is a surface that combines sophistication, superior performance, and the allure of the natural material for indoor and outdoor applications.

This collection includes 11 colors in a variety of finishes, plus seven available in Landmark’s outdoor 2-centimeter pavers.

LANDMARKCERAMICS.COM

LANDMARK CERAMICS, A 100% AMERICAN CERAMIC TILE COMPANY, SPECIALIZES IN PRODUCING HIGHQUALITY PORCELAIN FROM ITS HOME IN MOUNT PLEASANT, TENNESSEE.

The new Alabastri collection from Casalgrande Padana emulates the ancient beauty of alabaster. This original take on the extraordinary sheen and vibrant color of the highly sought-after material creates memorable ornamental motifs and decorative friezes.

Alabastri’s delicate shading, subtle mother-of-pearl transparencies, and the interplay of light and shadow make for a remarkable, rich look. The new collection comes in five colors (Alabastri Black, Blue, Green, Pink, and White) in a variety of sizes.

Like all the Casalgrande Padana stoneware collections, Alabastri is made from natural raw materials. It is eco-compatible, fire-resistant, non-absorbent, antibacterial, and self-cleaning.

CASALGRANDEPADANA.COM

Marblique’s revolutionary Visual Touch technology, manufactured by Crossville in partnership with Italy’s Ceramica del Conca, brings design to life with rich, textural realism. The four stone surfaces that make up Marblique are rendered to have a look and feel that is out of this world, with meticulous veining alongside the nuanced textures of acid etching, brushing, and bush hammering. Seen here in Invisible Grey, Marblique is also available in four other colors. Choose from 24-by-48, 24-by-24, or 12-by-24 field tiles.

CROSSVILLEINC.COM

We pioneered the first PVC-free wall protection. Now, we’re aiming for every 4x8 sheet of Acrovyn® to recycle 130 plastic bottles—give or take a bottle. Not only are we protecting walls, but we’re also doing our part to help protect the planet. Acrovyn® sheets with recycled content are available in Woodgrains, Strata, and Brushed Metal finishes. Learn more about our solutions and how we’re pursuing better at c-sgroup.com.

Versetta Stone is now available in three fresh colors—Granite Peak, a sophisticated dark gray; Lunar Drift, a clean, modern white; and Glen Canyon, a warm, earthy blend of neutrals. The versatile modern stone siding solution offers easy panelized installation for the hand-crafted look of traditional stone masonry without the complexity.

The collection’s convenient, panelized design features a tongue-and-groove interlocking system that ensures perfect spacing, a virtually seamless look, and easy installation with screws or nails in any weather.

Versetta Stone is also designed to maintain its beauty over time with minimal upkeep, as there’s no need for painting, coating, or sealing once installed. Versetta Stone features an advanced moisture management system, offers wind resistance up to 110 miles per hour, and carries a Class A fire rating for protection against water intrusion and harsh elements.

VERSETTASTONE.COM

Tando Composites, a division of Derby Building Products, now includes the new ProBrick, an extension of the TandoStone line. ProBrick is Tando’s latest composite brick and is a natural extension of the TandoStone composite stone offering, according to Ralph Bruno, CEO of Derby Building Products. “Adding ProBrick to our Stacked Stone and Creek Ledgestone TandoStone lines will continue to elevate our brand leadership. Our complete TandoStone line, now including ProBrick, meets the industry needs of a masonry product that the siding installer wants to install. The word composite has baked-in connotations as superior, and the receptivity is very high, but today’s consumer demands products that have authenticity and natural looks. That is what ProBrick delivers, along with faster, easier installation and no need for masons, scaffolds, or special tools; it installs in panels rather than painstaking individual bricks.”

Tando Composites’ products, including ProBrick, require less labor, faster job cycle times, and require virtually no upkeep, Bruno says. “Additionally, unlike concrete-based products, ProBrick is impervious to moisture.” ProBrick can also be recycled.

TandoStone ProBrick is available in two colors—Madeira, a rich, classic red, and Racinette, a deep, earthy brown. The ProBrick line also includes the aLL-Pro Corner, a onepiece corner designed to save time and labor no matter the project. TANDOCOMPOSITES.COM

INCREASED RISK

Fire risks to life and property are not new, but mass conflagrations are on an alarming increase.

“It is generally recognized that there is really no such thing as a fireproof building.”

Those may be surprising words considering the source. It’s what Dave Bueche, director of fire and life safety codes at Hoover Treated Wood Products, wrote in “New Developments in Structural Engineering and Construction” (published in 2013).

And he knows what he’s talking about. Bueche holds a Ph.D. in wood utilization and marketing from Colorado State University and is an active member in a wide breadth of fire-prevention professional associations:

ASTM, International Code Council (ICC), National Fire Protection Association, Society of Fire Protection Engineers, Society of Wood Science and Technology, and is a past board member of the Forest Products Society. He is also an industry representative on UL Solutions Standards technical panel on surface burning characteristics of building materials and serves on ASTM and NFPA committees.

But none of this is to say Bueche is pessimistic about what can be done to prevent fires in both residential and commercial structures. Quite the opposite, in fact.

“Fires can occur in any type of structure,” Bueche writes. “The severity of a fire, however, is contingent on the ability of a construction to confine the fire, limit its effect on the supporting structure, and control the spread of smoke and gasses.”

Particularly in the wake of the epic wildfires in Los Angeles—an increasingly common occurrence across the globe in a warming climate—there is more than a germ of hope in that statement.

Fires that affect structures are hardly new. Rome burned, as did Chicago. More recently the fires in Pacific Palisades, Altadena, Paradise, and other California towns are said to have destroyed more than 36,000 homes. Approximately 200,000 residents, possibly more, were displaced in the 2023 Canadian wildfires. As the climate warms there is an increasing risk of fires to whole communities, sometimes in places previously unaffected by wildfires.

The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) reported in 2021 that fire departments across the US responded to 1.3 million fires that year. Those fires led to 14,700 civilian injuries and 3,800 civilian deaths. About three-quarters of those deaths were in home fires. The damage from those fires is believed to have cost $15.9 billion.

Wildfires that affect dozens if not hundreds or thousands of homes at a time usually exist in what’s called the Wildland-Urban Interface, or WUI. As the name suggests, the term sums up the many interconnected factors for communities that border on natural (unbuilt) areas that are vulnerable to burning: fuel availability (wildland vegetation, its density and proximity to structures); the built environment combustibility (roofing, siding, decking, and fencing materials); historic fire patterns (fire causes, be they human or natural, seasonal weather trends), and ember exposure (how embers are subject to prevailing winds and accumulate near structures).

“UNPROTECTED STEEL IS PRETTY WEAK,” BUECHE SAYS. “FRTW MAINTAINS ITS STRUCTURAL INTEGRITY AND SLOWS THE PROGRESSION OF FIRE.”

1.3 MILLION

THE NUMBER OF FIRES IN 2021, ACCORDING TO THE NFPA

Insurers look at WUI for population density, firefighting infrastructure, and fire suppression capacity, such as water availability, municipal fire department equipment, and documented response times.

More than one-third of the US population lives in a WUI, according to “Planning the Wildland-Urban Interface,” a 2019 report published by the American Planning Association.

Building codes to address this vary from state to state and even city to city in addressing these risks. Because of how structures are built, the materials used can make a great deal of difference. So too are the distances between structures, if any, and the proximity of combustible landscaping.

Bueche, in his work with Hoover Treated Wood Products, endeavors to mitigate those risks. The company produces fire-retardant-treated wood (FRTW) that does just that: It slows or stops fire from igniting buildings. One product, ExteriorFireX, is used on structure exteriors and is specifically formulated to also withstand weather, high humidity, and dampness. The product best used indoors is its PyroGuard pressure-impregnated FRTW.

These aren’t just company claims, though. Building codes, architects, and owners require third-party verification of such materials. The gold standard of certification is UL (UL Solutions), which found “PyroGuard Fire-Retardant-Treated (FRT) Wood covered under this report has a flame spread index of 25 or less and a smoke developed index of 50 or less, when tested in accordance with UL 723 (ASTM E84) and did not show any evidence of significant progressive combustion when the test was continued for an additional 20-minute period. The flame front did not progress more than 10-and-ahalf feet beyond the centerline of the burners at any time during the test.”

This is good news for builders opting to use wood in a quest for both safety and sustainability. After all, trees sequester carbon long before harvesting. That is in contrast to the carbon footprint of steel, concrete, brick, and glass manufacturing. Surprising to many is the fact that wood, particularly FRTW, is actually stronger than steel when exposed to extreme fire heat.

“Unprotected steel is pretty weak,” Bueche says. “FRTW maintains its structural integrity and slows the progression of fire. The char layer formed on FRTW is tenaciously adhered to the surface and, as the FRTW burns, it releases carbon dioxide and water vapor, which dilute the combustible gases produced by the wood. It also cools the wood surface.”

In light of the mass destruction of wildfires everywhere, Bueche is seeing increased interest in fire-retardant-treated wood. Had more homes in Los Angeles used FRTW materials, would it have reduced the damage?

“Probably, particularly with siding and decks near the WUI,” Bueche says (wood decks in particular, with spaces between boards that can capture flying embers, are vulnerable to catching fire).

But the application of FRTW goes beyond homes in WUI regions. In addition to single-family residential applications, the Hoover products are useful in townhome construction, where FRTW eliminates the need for roof parapets at code-required firewalls.

It’s useful in the huge roof systems of large warehouses and big-box retail stores. There are military and nuclear power plant applications, particularly where wood scaffolding is used for construction and maintenance.

Roughly a third of the US is subject to disaster-resistant building codes. And as Bueche describes it, those codes have advanced over time. Decades ago the codes primarily addressed property assets as a value, less so that of human life.

“The codes originated from the insurance industry,” he says. “Over time a number of regional codes were developed based

on the experience of catastrophes—fires, earthquakes, and storms.”

Guiding many states and municipalities is the International Wildland Urban Interface Code update in 2021, which addresses wildfire risks through regulations on materials, construction, and vegetation management. That code is created and published by the International Code Council (see page 114).

So, as Bueche says, no building is fireproof. But with advancing materials technologies, methodologies, and code requirements—and greater public awareness about safety and property protection—stopping the advance of fires is getting better all the time. gb&d 1/3

Good water infrastructure stands up to the needs of today and anticipates the needs of the future.

Building a truly resilient stormwater system means also planning how to recover from problems if needed.

In 2024 Hurricane Helene unleashed more than 40 trillion gallons of rain across its path. That’s the amount of water that’s in Lake Tahoe.

Now picture Niagara Falls. If you waited for that amount of water to go over the falls, “you’d be standing there for 21 months,” says Brian King, executive vice president of product management and marketing at Ohio-based Advanced Drainage Systems (ADS), which manufactures stormwater and onsite septic wastewater solutions.

Hurricane Helene wasn’t your average hurricane, ranking as the seventh costliest US tropical cyclone and one of the country’s deadliest hurricanes. But right now the definition of an average storm isn’t crystal clear.

“Your 50-year storm now happens every 20 years, right? Or even every 10 years,” King says. “Stormwater management is becoming increasingly important as you see the changing weather patterns.”

And that’s making it increasingly important to build in resiliency, sustainability, and

Did You Know?

any adaptability you can into your water infrastructure. You want to think holistically about how to manage stormwater today— and how to do it 25 or 50 years into the future. “Generally speaking when you build stormwater infrastructure there’s not a lot of opportunity to go back and revamp and renovate that,” he says.

Taking those steps can require looking at the investment in water infrastructure in a different way. “A lot of times, we look at the initial cost, and not the total cost over the life cycle of how long that infrastructure is supposed to last,” says King.

For ADS its water management solutions are designed to last decades. “Our pipe is designed and manufactured to last up to 100 years.”

People should also be thinking about how to use stormwater to their advantage. “Traditionally stormwater has been seen as a nuisance: You try to get it away from where you don’t want it to somewhere that’s not going to cause any harm,” King says. “And now we’re starting to think about stormwater as a resource or an asset.”

Can it be stored and used for irrigation, gray water, or even potable water? “I think that’s how things are starting to change, as opposed to just ‘get it away from where I don’t want it to be,’” King says.

ADS PROCESSES 540 MILLION POUNDS OF RECYCLED MATERIALS AND DERIVES 54% OF ITS PIPE REVENUE FROM RECYCLED PRODUCTS.

CLOCKWISE, FROM OPPOSITE: Stormwater management is in process for a commercial project in Nebraska. An apartment project gets high-quality water infrastructure. HP Storm offers up to 100% greater pipe stiffness over traditional plastic pipe, according to ADS.

Last fall ADS opened its new $65 million Engineering and Technology Center. The 110,000-square-foot, stateof-the-art facility centralizes the company’s R&D efforts to create innovative stormwater management solutions.

The center includes fabrication and 3D printing labs for developing prototypes, material science capabilities for assessing different plastic polymers, and tools for testing and analyzing performance. A hydrodynamics lab can recirculate up to 90,000 gallons of water for testing purposes.

“It’s taken all the different capabilities that we had across the network and put them all into one place,” King says.

“That’s going to help us go through the product development cycle a lot faster.” 60%

THE PERCENTAGE OF AMERICANS CONCERNED ABOUT THEIR COMMUNITY’S STORMWATER MANAGEMENT INFRASTRUCTURE

ADS, which manufactures corrugated plastic drainage pipe for its water management solutions, offers various advantages in terms of resiliency. “Most systems, if they’re going to fail, they’re likely going to fail at the joint between one pipe and another pipe,” King says. “Our pieces of pipe are 20 feet long versus, if you’re using concrete, 6 to 8 feet long. So there are less joints.”

Plastic pipe can also make for easier recovery should a system run into problems.

“I’M HERE TO TELL YOU THAT RECYCLING DOES WORK. IT’S NOT EASY; THERE’S NO SILVER BULLET TO RECYCLING. THERE ARE ALL SORTS OF CHALLENGES TO OVERCOME, BUT IT CAN WORK, AND IT IS ECONOMICALLY VIABLE.”

“We would tell you that one of the benefits of using plastic pipe is you can recover faster. Everyone wants to build a system that’s resilient and is going to last, but you also have to plan for what happens if it doesn’t.”

ADS focuses on not just resiliency but also sustainability, manufacturing many of its products from recycled plastic. It’s been doing that since the 1970s, initially because it was a source of raw materials that offered financial benefits. But that’s taught the company an important lesson: “Good sustainability practices have to be based on good financials,” King says.

These efforts reduce the greenhouse gas emissions of the company’s products and help keep plastic out of landfills. In 2024 ADS bought 540 million pounds of recycled material, helping to recycle 33% of all high-density polyethylene (HDPE) bottles in the US.

An expansion of its recycling facility in Cordele, Georgia, that kicked off in early 2025 will help ADS increase its capacity for processing recycled material and support recycling in general. “It’s going to provide

that outlet for demand, so the material recovery facilities down there can actually sell it,” King says. “And that spurs investment in more recycling.

“I’m here to tell you that recycling does work,” he says. “It’s not easy; there’s no silver bullet to recycling. There are all sorts of challenges to overcome, but it can work, and it is economically viable.”

For King, resiliency and sustainability go hand in hand. “Plan for the future; make sure what you’re building is going to be a good investment and be resilient enough to address what’s going to change,” he says. “And then, if you can build it using sustainable materials, or materials that have less greenhouse gas emissions, that’s the trifecta of good stormwater management.”

But while these are general approaches everyone should consider, every stormwater management solution is unique to the piece of property being developed and the

area where it is. “Developing a system in the south of Florida, where the water table is very high and where you have some interesting storm activity going on, is going to be very different than if you’re developing a system in Colorado, where you’ve got snow melts and some other pieces,” King says.

That’s why it’s important to think more about the long-term cost of a system than just the initial cost, and to make sure it’s accomplishing exactly what you need it to do. “We think about that as the life cycle of a raindrop,” he says. “I think that’s how people need to think about stormwater solutions. What happens to that raindrop once it hits the ground, and where does it go?”

gb&d

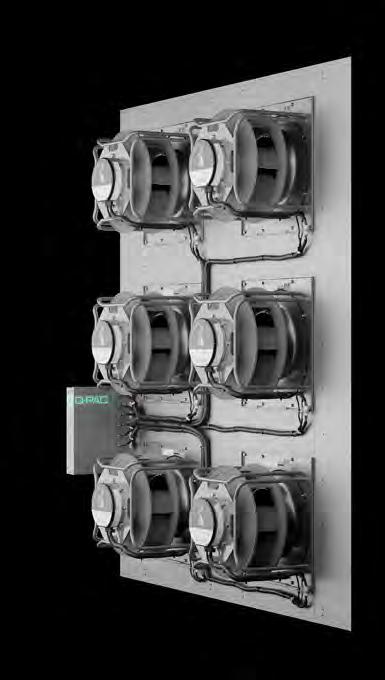

Creating new paths to efficiency, adaptability, and accessible comfort

BY AMBER CORRIN

Architects designing new buildings—or redesigning elements of iconic structures— must take countless aspects into consideration as they work. The nuances of the building’s HVAC system may not necessarily rank consistently among highest priorities.

In some ways that’s changing amid shifting awareness and demand for better energy efficiency, air quality, and reliability. Nonetheless, at least one HVAC industry leader would argue that architecture and design shouldn’t be sacrificed to accommodate customized equipment and space for heating and cooling.

“When you want a nice-looking building you end up making the engineering incredibly challenging because it’s not all straight lines. High-occupancy verticals typically have interesting architecture. A 66-story building in Manhattan is a unique building,” says Matt Kent, Q-PAC’s CEO. “Architecturally, our fans and our company history center around highly occupied spaces that need human comfort.”

Q-PAC’s direct work with architects, in particular, shapes how they view their clients’ needs. “That’s what creates the mar-

ket for custom air handling units. When an architect’s working on a building the last thing they want to hear is that their equipment room needs to be two times bigger. They aren’t designing the building for the equipment; they’re designing it or the visitors and the people using it,” Kent says. The problem is this: If that 66-floor, high-occupancy building has a traditional air handler with a single fan that loses its motor, a lot of people just lost airflow as a result.

An early solution to failed motors in commercial fan systems was to build an array of multiple fans, creating reliability through redundancies. But engineers found that introducing multiple fans also introduced more complexity, compounding hardware and investment. But what if there was an approach that could leverage the reliability of multiple fans and eliminate the complexity of fan arrays?

This is the idea behind Q-PAC’s Multimotor Plenum Fan, a single fan that integrates multiple motorized impellers within a custom frame and is operated by a single, software-based fan controller—functioning essentially as a single fan but still offering the redundancy of a fan array. “Customers never really wanted a fan array anyway; what they wanted was reliability,” Kent says. “We wanted to make it easy. Our model is we manufacture a fan, ship it, and it’s so easy you don’t need a Q-PAC person to be there.”

Q-PAC’S NEW MULTIMOTOR PLENUM FAN

is engineered to replace large single fans and fan arrays in commercial air handlers, swapping them for streamlined, low-maintenance, and more resilient airflow solutions.

BY ESTABLISHING A PLATFORM THAT’S USERFRIENDLY—EASY TO INSTALL AND SIMPLER TO OPERATE—Q-PAC LOOKS TO BRING INNOVATION TO CUSTOMER CHALLENGES AND ACHIEVE NEW LEVELS OF EFFICIENCY.

This is critical as skilled labor becomes harder to find. A solution that can be moved by two people instead of a crane and installed safely with basic hand tools now has extra appeal.

Nest thermostats were a big inspiration, Kent says. “When I worked in residential HVAC 15 years ago, you would have never in a million years asked a homeowner to replace the thermostat. Nest defied all that logic. They basically made it so almost anyone with a screwdriver could change the thermostat for $200.”

Q-PAC’s MPF also streamlines maintenance and emergencies; the modern system eliminates components that traditionally require servicing, repairs, replacement, and upkeep. This means no grease, no belt changes, no bearing swaps, no burn-ups that contaminate air quality—freeing up facilities teams to focus on more critical issues and reducing total cost of ownership.

In those big, high-occupancy buildings still equipped with older, large fans, owners and operators face scarce options when that single fan reaches end of life, Kent says. Retrofitting these setups requires physically destroying the old fan—the most challenging part of the project, according to Kent—then installing a replacement.

After some difficult experiences on these types of projects, Q-PAC went back to the drawing board and spent two years figuring out how to reduce complexity by pre-engineering the equipment in a factory setting.

“The idea of a fan with multiple motors hadn’t really been done, but it simplifies things for end users, and our whole focus is on end users,” Kent says. “The invention of the Fan Controller really unlocked our ability to build this category. We realized over the years of innovation that really what we needed was a new type of fan.”

“ARCHITECTURALLY, OUR FANS AND OUR COMPANY HISTORY CENTER AROUND HIGHLY OCCUPIED SPACES THAT NEED HUMAN COMFORT.”

The demand for more energy-efficient and environmentally friendly solutions is a significant driver for change, and Kent says Q-PAC is already delivering on some of that demand. Today their biggest gains in energy efficiency are through their retrofit projects. “A building running off a legacy technology provides them an easy way of replacing it with more advanced motor technology, and that’s probably the biggest offset today—reducing power consumption,” he says.

This has been Q-PAC’s focus in recent years: building a multimotor plenum fan that’s easy to install, maintain, operate, and control. And while retrofit projects are essential elements of the company’s portfolio—and its progress—new air handlers now account for some 70% of the fans they’re manufacturing. Q-PAC’s primary objective is to have one of their fans in every air handler, whether it’s new or existing, according to the team.

“We’re actively building out this new category, building a platform that is easy to adopt. Then we’ll start talking about new ways of achieving never-before-seen reductions in power consumption and similar breakthroughs,” Kent says. “But we’re not going to skip step one, which is a highly, highly reliable product.”

One especially prominent retrofit project for Q-PAC was the US Steel Tower (USX) in Pittsburgh, an iconic 64-story skyscraper completed in 1971. When a mechanical problem crippled the original fan system, the building’s management faced repairs that would shut down city blocks for weeks, creating major disruptions. It would also require crane access through a massive hole cut into the side of the historic structure, which is one of the largest LEED-certified buildings in the world.

Q-PAC’s application engineering team worked closely with Havtech to design a 120,000-CFM (cubic feet per minute) solution that would meet both the established airflow capacity and the filtration and fresh air exchanges necessary to maintain LEED certification.

“These older buildings, a lot of the air handlers were placed here when they built it,” Paul Kotchey, mechanical engineer at K&I Sheet Metal, says in a Havtech video feature on the project. “Doing a replacement like this, you need a qualified team of a good replacement contractor, a good system to replace the existing—which Q-PAC fulfills—and an owner that’s willing to work with you to make it all possible.”

Instead of initial grim prospects for fixing the USX failed fan system, Q-PAC delivered a pre-engineered kitted fan system with single-point power and controls ready to go. Installation started on a Friday evening and finished on Sunday morning, with Q-PAC onsite to assist throughout the process. Work finished within 48 hours with no disruption to the city.

“To be able to take this system up in an elevator over a weekend and be up and running Sunday morning, it’s almost unbelievable. But we were able to help eliminate so much risk,” Kent says. “Old infrastructure is hard to upgrade. We provide the opportunity to make significant improvements to existing infrastructure. Going forward we’re building an AMCA wind tunnel, we’re leaning into our technology, and we’re going to crack the code on energy efficiency—way beyond what we have already accomplished. I’m really excited about our path for the future.” gb&d

“TO BE ABLE TO TAKE THIS SYSTEM UP IN AN ELEVATOR OVER A WEEKEND AND BE UP AND RUNNING SUNDAY MORNING, IT’S ALMOST UNBELIEVABLE.”

DOOR ENTRY SYSTEMS NOW INTEGRATE WITH APPS AND SOFTWARE, OFFERING EASY REMOTE CONTROL AND INSTANT INFORMATION ABOUT BUILDING ACCESS.

Long-lasting, flexible tech solutions are an upgrade from basic intercoms.

WORDS BY ELYSE HAUSER

PHOTOS COURTESY OF COMELIT

The days of a stainless steel, two-way intercom on every multifamily building are over. New connected door entry solutions break the mold to offer convenient, hightech security.

“When I first started, multifamily basically meant old infrastructure, old intercom systems: you know, a typical buzzer. Somebody’s at your front door, you buzz them in,” says Robert Bhiro, vice president of sales at Comelit.

Today’s systems streamline and elevate the experience: They’re intuitive to use and offer reassuring layers of security. “No matter where the project’s located, I think there’s always a desire to keep a sense of security and ownership of the spaces for the residents of the building,” says architect Nate Sunderhaus, senior associate at Perkins Eastman.

That security goes hand-in-hand with sustainability, too. Flexible modern systems can reduce waste, conserve resources, and even fit aesthetically with buildings of any style.

Smart intercom systems integrate with other software for sleek, comprehensive security. Property management software and mobile apps are popular integration options. Video that shows what’s happening at an access point has become valuable, too. “With the use of Wi-Fi and the ability to have everything interconnected, video is incredibly important, and live feeds,” Sunderhaus says.

These integrations are also highly customizable. “Security is now proactive rather than reactive,” Bhiro says. Landlords and property managers can decide which tech integrations they’d like, instead of picking a one-size-fits-all option.

Integrated modern systems offer not just high-end security, but visual reassurance that helps tenants feel secure. “The better the tech looks, the more they’re going to feel that way and the better it’s going to feel,” Sunderhaus says.

These high-tech options can be more sustainable than older, simpler designs. “Most intercom companies, back when I started, their life cycle was five, six years,” Bhiro says. Each time an old system got removed and replaced, it became e-waste.

Today’s systems are more durable. Improved sustainability requires hardware that lasts: Even touchscreens must stand up to heavy use and inclement weather. It also requires software that upgrades easily without replacing hardware. “A big part of sustainability is reusing or not having to rework things, making things flexible,” Sunderhaus says. These long-lasting systems offer longterm value for users and for the planet.

Not all buildings have the same budget, but they all can have secure, modern door entry systems. The options range from simple intercom-less designs that work by calling a resident’s phone to fancy 7-inch touchscreens that control entry from inside apartments.

Developed by Extell, 70 Charlton in Manhattan is a luxury residential building equipped with Comelit’s VIP video entry system. The property features 316 Touch entrance panels, in-unit monitors, app-based access control, and integrated elevator management—delivering both security and modern convenience.

“A big part of sustainability is reusing or not having to rework things, making things flexible.”

The Mercer Building in Denver uses Comelit’s VIP video entry solution across more than 230 units. Its setup includes two 316 Touch panels and one Ultra Touch panel, with app-based access that streamlines secure entry for residents.

“Intercoms are no longer just a communication tool. They’re part of an access control solution.”

Visual style is important, too. Comelit’s graphic user interfaces can be tailored with custom wallpapers, images, and information. So can the physical intercom panels; a range of designs can always match a building’s style.

“Lobbies are typically very high-design spaces,” Sunderhaus says. “So we’re always trying to show off a little bit of what’s going on inside and how nice the interiors of the building are.” At The Ryland, a multifamily building in Philadelphia, the design team added an intricate decorative wall to the lobby. They chose to place a well-matched intercom system on a pedestal in front of the wall to suit the design without distracting from it.

When Comelit was founded in Italy in 1956 its analog systems had to work on the existing wiring of old Italian buildings. While the systems have modernized, the compatibility remains the same. “We’ve installed intercom systems on wiring that was put in in the 1960s, 1970s, and it still works perfectly fine,” Bhiro says.

After 10 or 20 years go by and it’s time for a replacement, the newer replacement system can still use existing wiring. This not only saves time and money but cuts back on material waste, since buildings don’t need to be rewired for new intercoms.

As technology evolves user friendliness remains key. Comelit prioritizes intuitive designs, like a button that flashes green to answer an intercom call, and another that flashes red to hang it up.

Software is part of user-friendliness, too. App-integrated smart intercoms allow for easy control from anywhere. For example, residents can use a mobile credential app to send visitors a single-use access pin or QR

code. “Before intercoms were smart, none of these things existed,” Bhiro says. “Intercoms are no longer just a communication tool. They’re part of an access control solution.”

Property managers can use similar solutions, like granting access to new tenants through a management app. “You can provide and take away access remotely, and you can do it in real time,” Sunderhaus says.

Security isn’t just about physical access. In the digital era cybersecurity is paramount; intercoms need to be encrypted and protect against digital threats. “Especially now that some of the intercom systems require people’s email addresses and phone numbers and apartment numbers to be inside the system,” Bhiro says. Storing tenant information locally at the building, instead of on the cloud, can protect tenants against cybersecurity leaks.

Connected door entry systems continue to evolve, with exciting possibilities on the horizon. “We’re thinking about what is going to be part of this building solution that lasts longer, that works smarter, and provides property managers and residents with better control over the security,” Bhiro says. gb&d

BY LAUREN GALLOW

With the building and construction industry responsible for nearly half of annual global carbon emissions, making sustainable choices in the built environment can have a big impact on reducing global warming. We know buildings contribute to carbon emissions in two major ways: the embodied carbon of the raw materials used in putting together and taking down buildings, and the operational carbon needed to power buildings. When it comes to lowering the carbon footprint of buildings, we must look at both sides of this equation, acknowledging that “sustainable” is a complex term—one that often involves tradeoffs and making informed choices.

We also know that when it comes to building materials, the sum of those choices is what adds up to sustainable—and ideally zero-carbon—buildings. While much of the embodied carbon conversation of late has centered on structural materials and how we might shift away from steel and concrete toward a renewable resource like wood, there

“If we’ve chosen materials well and with circularity in mind, it can live a number of lifetimes. That’s ideal.”

are many other essential components of buildings that deserve our attention. One such component is the roof—one of the most important, but least discussed, elements of a building.

Because design tends to focus on the visible aspects of a building like the facade or the interiors, choices about roofing materials are often an afterthought. However, if a roof fails, the impact can be catastrophic. “The roof is such a critical aspect of the building in terms of how the building operates, and the money that’s spent to protect everything inside it,” says Myrrh Caplan, senior vice president of sustainability at Skanska. “What I advocate for in terms of roofing is quality.”

One of the largest construction and development companies in the US, Skanska is helping drive the industry toward a more sustainable mindset. The company is aiming to reach net-zero carbon emissions in their projects by 2045 and is actively transitioning to low-carbon construction across its portfolio. Having been ISO 14001-certified for nearly three decades, sustainability is embedded

in Skanska’s DNA, and the company works closely with partners across the industry to improve access to information that can inform more sustainable material choices, particularly with their EC3 Tool. Co-created by Skanska with industry partners, the free tool indexes more than 100,000 Environmental Product Declarations to help inform decisions around sourcing low-carbon materials, including those used for roofing.

“Where I have been involved in conversations around roofing, the number one topic is green (vegetated) roofs,” Caplan says. “Other conversations are around heat resilience and durability. When it comes to creating a more energy-efficient building, you have to do the analysis to determine what is the right product given the clients’ goals or what the building needs to be.”

Just as with other building materials, Caplan suggests there are a multiplicity of factors that play into decision-making for roofing, including climate, product lifespan and makeup, and budget. “You have to look at balancing out the effects and the opportunities that come with each individual product,” she says.

One of the most durable and longest-lasting roofing materials is PVC. Short for “polyvinyl chloride,” PVC is a highly versatile plastic material that has been used for many construction products, including roofing, since the mid-20th century. Manufacturer Sika has been a leader in developing PVC roofing solutions globally for more than 60 years.

“There is a heritage at Sika of producing a really high-quality, long-lasting, durable product,” says William Bellico, vice president of marketing and inside sales for roofing at Sika. As such, Sika is grounded in a vision of sustainability that takes the entire life cycle of a building into account. Today the company is committed to supporting a global transition toward circular, sustainable design, aiming to reduce its company carbon emissions by 90% by 2050.

For Sika, the long service life of PVC makes it a highly desirable roofing solution. “When you’re looking at material impacts, the life cycle of the products should be at the forefront,” Bellico says. “With embodied carbon metrics, one of the current limita-

tions is that typically only a ‘cradle-to-gate’ view is being analyzed, which only looks at the carbon impacts of the initial production of the material. If a product lasts twice as long, that’s less extraction of raw materials and less operational carbon to create replacement materials—and that’s a huge sustainability element in our minds.”

While some roofing technologies have lifespans of 10 to 20 years, several of Sika’s PVC membranes have been third-party verified to last more than 35 years and have published cradle-to-grave EPDs.

When it comes time for replacement, Sika has developed an industry-leading recycling program for their vinyl roof products. Every year Sika not only recycles millions of pounds of pre-consumer production scrap material but also roof membranes at the end of their service, reducing the burden on landfills. “Our primary recycling process is closed loop, taking old roofs back, processing them and working the material back into new roofing products,” Bellico says. “We’ve also been trying to grow the overall volume of recycling that we’re doing.”

BY

“The question is— how do we continue to move the needle and lessen the environmental impact of roofing?”

Today the company is actively expanding its recycling program, also working with partners in open-loop recycling channels. “The question is—how do we continue to move the needle and lessen the environmental impact of roofing?” Bellico asks.

As with any building material selection, it’s important to weigh the various attributes of products within a material category. When it comes to roofing sustainability, it’s important to look at the real-world performance of the material (versus warranty offered), third-party certifications on performance and/or sustainability claims, recycling, carbon offsetting with “cool roof” colors, fire resistant performance, and Cradle-to-Grave EPDs. All these attributes correlate directly to the sustainability of a product, Bellico says.

He says the Red List is another interesting consideration, as it’s often a top focus

when teams are considering a particular solution—whether products have ingredients listed on various Red Lists. It is important, Bellico says, to look beyond just being listed and understand how that ingredient is used in the product. If used during production but not harmful after the finished product has been created, does it pose an actual notable risk after production, for example, he asks.

“The plastics and PVC industry is one of the heaviest regulated industries in the US,” says Stefan Long, Sika’s sustainability manager for roofing. “This helps ensure that modern PVC is not only manufactured the right way but doesn’t pose a risk to the environment or the public. At the same time Sika is always looking at ways to continue to push the PVC roofing industry to be more and more sustainable.”

Only looking at one attribute to guide material selection may lead a building professional to a product that, on paper, may

For the roofing membrane at Sunset Glenoaks Studios in California (above), the project team used Sarnafil G 410 60-mil, Energy Smart Reflective Gray. It was fully adhered using the lowVOC water-based Sarnacol 2121 adhesive. At right, Sika’s first post-consumer recycling project, the Marriott Long Wharf in Boston, was completed in 2005.

captions .....

look like it is more sustainable but doesn’t have the real-world performance history and could fail prematurely. “When you’re thinking about roofing, you have to look at the full spectrum of all the different options and create your own report card for sustainability,” Long says. “You can get advice from manufacturers and see how all the options stack up, but ultimately you have to make up your own mind. Rather than relying on only one sustainability metric, we always recommend taking a multi-attribute assessment approach.”

Skanska’s Caplan agrees. “With roofing, if something is durable, resistant to water intrusion and staining and all those things

that become future maintenance and cost nightmares, what is the tipping point of how much carbon emissions it’s offsetting by providing a better box?” she asks. “You are choosing your own adventure by weighing the benefits and also the potential future risks.”

Ultimately the conversation around roofing reminds us that considering the full life cycle of a building and each material component is one of the best ways to gauge its sustainability. As we know, the most sustainable solution is often the one that simply uses less: less raw materials, less embodied carbon, and less operational energy.

Skanska’s approach to a new project with the New York City Economic Development Corporation for a Science Park and

Research Campus embodies this mindset, as the project involves deconstructing a substantial existing building on site before new construction.

“With this project we’re looking at the life cycle full circle,” Caplan says. “It calls into question: Where does that life cycle of a building end, and where does it start, and could we have a continuation of that life cycle? To me, if we’ve chosen materials well and with circularity in mind, it can live a number of lifetimes. That’s ideal.” gb&d

BY VALERIE DENNIS CRAVEN

Regardless of building type or age, occupant comfort is a top contributor to overall happiness and productivity for the people inside the building. The temperature and quality of air inside homes and commercial spaces is a key contributor to indoor comfort. If not controlled well, this can come at a price to the environment and energy efficiency, too.

The commercial and residential building sector accounts for 31% of greenhouse gas emissions in the US, according to the EPA. Many of a building’s core systems—including lighting, HVAC, and equipment and appliances—rely on energy to run, while maintaining occupant comfort, health, and safety.

Heating and cooling lead as the main consumers of energy in both commercial and residential buildings. In a typical home about 20 to 30% of the air moving through the duct system is lost due to leaks, holes, or poorly connected ducts, according to EPA estimates, resulting in a significant use of energy.

“We don’t need to wait for Aeroseal’s solutions to be applied 10 years from now; we can start fixing our buildings today. We can start reducing and making the environment better, more sustainable today.”

Small changes, like adjusting a thermostat or swapping more efficient equipment, can have a big impact on energy efficiency and, in turn, greenhouse gas emissions. But implementing these practices alone isn’t enough.

“The biggest bang-for-your-buck opportunity to improve energy use is in your air sealing and insulation of your structure,” says Lindsay Schack, founder and principal architect of Love Schack Architecture.

“If you’re not sealing properly between the assemblies, among all the ventilation, mechanical units, openings, doors, windows, thresholds, everything, you’re giving up on energy that’s inside the structure,” the certified PHIUS consultant says.

The goal for efficiency, conservation, and comfort is thermal continuity. Keep a space stable at the optimum thermal level at all times through balanced ventilation, which includes keeping outside air away and inside air from escaping. “The way to achieve that is to have good air sealing,” Schack says.

She offers a visual check to look at a building’s profile, pretend to cut it in half, and draw a continuous line all the way around, from the floor up the wall over the ceiling back down again. Vulnerabilities often occur where windows or doors connect, and where walls and roof come together, Schack says.

Gone are the days of poor ventilation and sick building syndrome. Today is about controlling emissions, waste, and air quality due to leaks in ducts.

Supply, equipment, or return duct leaks can compromise indoor air quality by bringing in air from places it shouldn’t be pulled (for example, the outdoors, attics, or crawl spaces), says Amit Gupta, CEO of Aeroseal, a leading manufacturer of duct and air sealing technology. The benefits of duct sealing are many—from overall comfort and money savings to improved air quality and safety.

Both Gupta and Schack agree that an airtight building with a reliable, well-functioning duct system helps move air where it’s intended. “Duct sealing is really important for balanced systems to work effectively,” Schack says.

All buildings—new construction or retrofit, residential or commercial—are susceptible to leaks. The challenge lies in both finding and accessing leaks, since ductwork is typically right behind a wall or ceiling.

“To seal all around the ducts is close to impossible; you can’t get your hand around it,” Gupta says. “If you can’t put tape around it, the ducts are left leaking all throughout the building’s life.”

To address the hard-to-reach inevitable gaps and cracks in ductwork or envelope, Aeroseal offers a nontoxic aerosol sealant solution to stop leaks where they occur.

Before sealing begins, HVAC professionals pressurize the ductwork and protect vital equipment, and a pressure test runs to measure initial leakage. Next, Aeroseal adhesive particles are heated, aerolizing them so that they are suspended in the air. The particles are then blown into the ducts, where they adhere to gaps and cracks, slowing filling them in until they are sealed without compromising other areas of the ductwork.

The automated process monitors to optimize overall effectiveness, with building or homeowners receiving a detailed before-and-after certified report that highlights results and air saved.

Unlike traditional sealing methods, which may have messy application meth -

ods, limited durability, or continued maintenance and upkeep, Aeroseal advantages are speed, quality, and level of seal, Gupta says. The duct sealant resists mold, mildew, and moisture.

With Aeroseal a duct system can be sealed in hours, and an envelope in a day. This is especially important for retrofits where people may be living or working. In retrofit situations, Aeroseal can reach leaks behind ceilings and walls—something that cannot be done by any traditional method without demolition and reconstruction, offering old homes and buildings a way to become significantly more energy-efficient without the typical high costs associated with a teardown and rebuild to get to the ductwork.

Gupta gives an example of hospitals and hotels, where air quality and minimizing disruption are important. He explains how

these areas are treated, isolating a small section of the building where each air handler is—typically 10 or 20 rooms—servicing the area in a few hours. “By the time we clean up and leave the air handler is back on and people can move in. There’s no downtime at all,” Gupta says.

Experts say duct sealing is an immediate solution to help make projects greener. It doesn’t involve any occupant or owner behavior changes and can contribute to building and home certifications. And the results are immediate.

“We don’t need to wait for Aeroseal’s solutions to be applied 10 years from now; we can start fixing our buildings today. We can start reducing and making the environment better, more sustainable today,” Gupta says. gb&d

As an industry leader, we are committed to protecting and managing water, the world’s most precious resource, by providing sustainable water management solutions that safeguard our environment and build resilient communities.

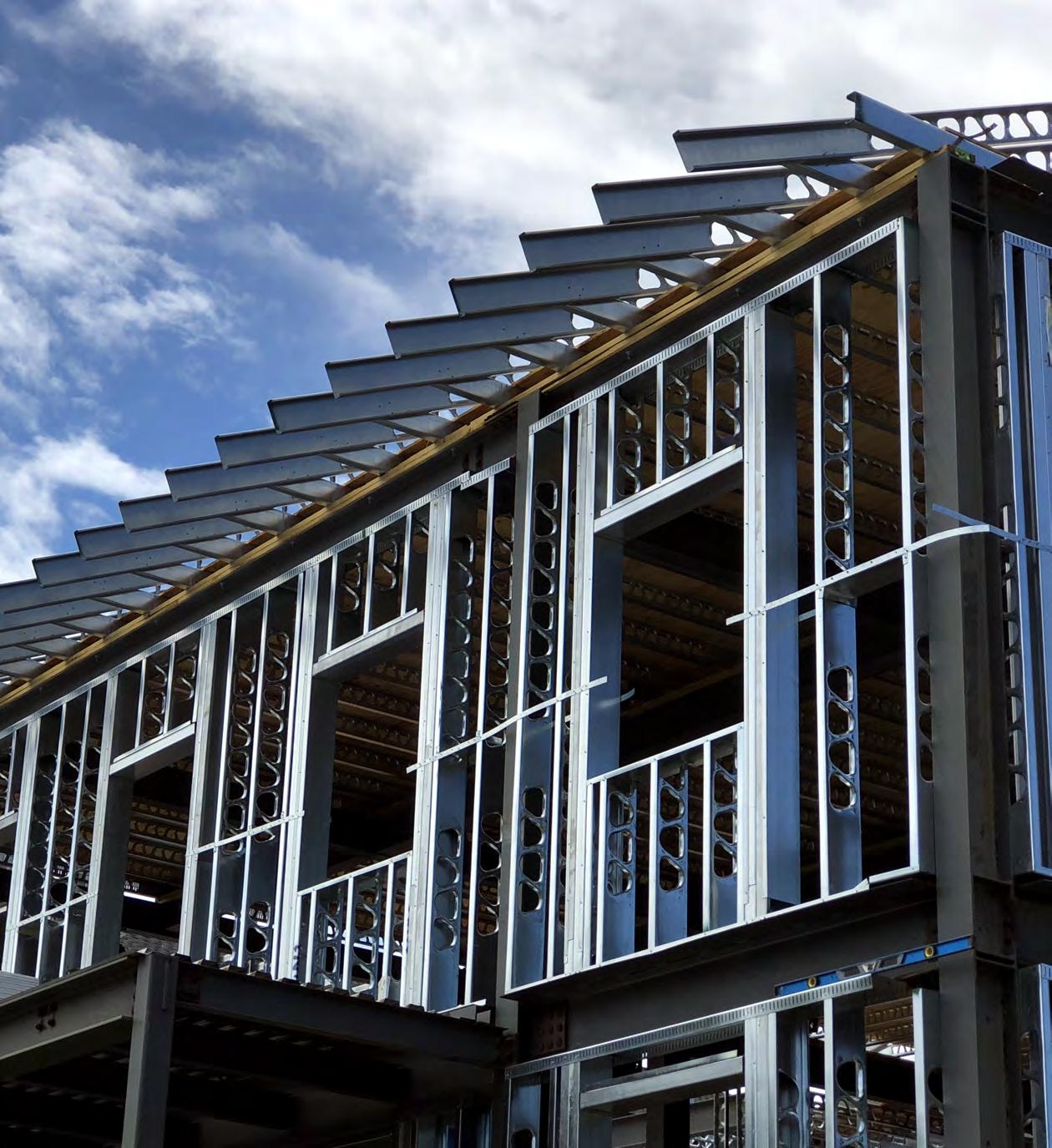

construction industry needs and pushing the limits of what’s possible

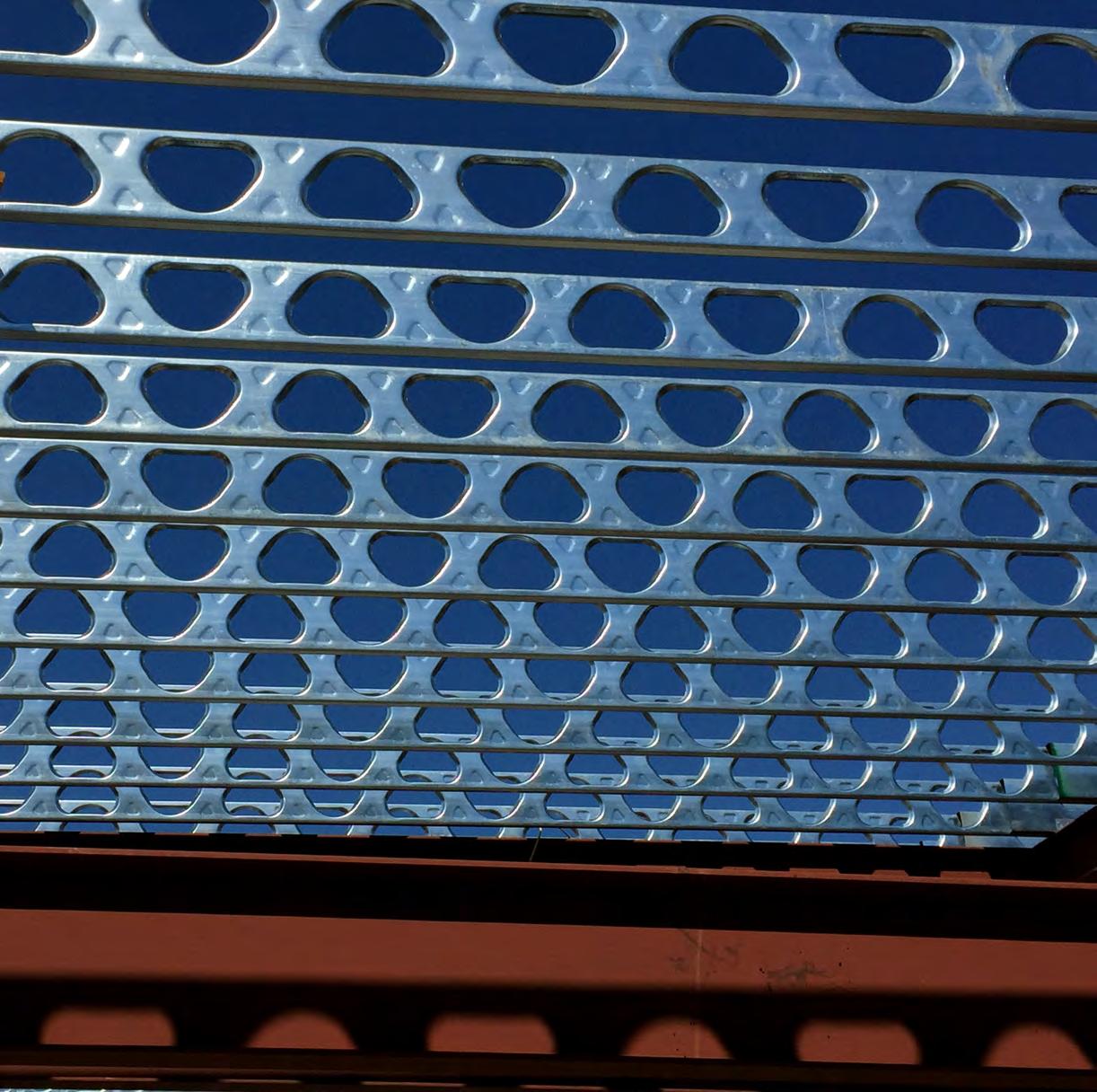

BY MATT WATSON PHOTOS COURTESY OF MARINO\WARE

The last couple of years have seen robust growth in the market for cold-formed steel. A combination of trends in the construction industry—from labor shortages to a greater emphasis on sustainable materials and improved workplace safety—has increased demand for cold-formed steel framing systems.

“Cold-formed steel is transforming modern construction by offering a versatile, sustainable, and high-performance alternative to traditional building materials,” says Steve McDaniel, vice president of business development at Marino\WARE, a leading manufacturer of steel framing products.

The overall benefits of cold-formed steel framing systems are well known in the building industry, yet many professionals may not be aware of the technological advancements that manufacturers of coldformed steel have invested in to improve its performance.

“We’ve gone out of our way in the industry to adapt and modernize to address the pain points we’re hearing from customers,” says Jim DesLaurier, vice president of engineering and technical resources at Marino\ WARE. “Our research and development has

focused on streamlining installation and addressing issues like sound quality and safety on the jobsite.”

These innovations have made coldformed steel lighter, stronger, more sustainable, and easier to work with. At the same time Marino\WARE and other cold-formed steel manufacturers have made advancements in products focused on acoustical control and fire safety.

“AEC professionals benefit from its superior strength, efficiency, and adaptability, making it an ideal choice for diverse applications across commercial, residential, and industrial projects,” McDaniel says.

Cold-formed steel can be used in nearly any type of project for interior framing, partitions, curtain wall construction, roof trusses, and floor systems.

“It combines the versatility of wood construction with the strength and reliability that concrete gives you,” says Eric Zuidema, senior structural engineer with global design and construction firm Stantec. “It’s a good mix between the two, so I think that

“This minimizes labor costs by eliminating or reducing onsite cutting, and streamlines installation, ultimately leading to overall project savings.”

really is the highlight of cold-formed steel.”

The most popular use cases for coldformed steel studs are typically for the framing of mid-rise projects like multi-family residential and hotels, as well as modular construction. Cold-formed steel can generally be used to construct buildings up to around 10 stories without the need for other structural materials.

Though elevated interest rates and the continued popularity of remote work have dampened demand for new office space, other areas of the construction industry are seeing robust demand for cold-formed steel framing. Data centers have been a true bright spot, as the rapid adoption of AI has set off a frenzy of activity in this sector.

“We are observing a dramatic rise in data center construction, a sector where coldformed steel excels,” McDaniel says. “Cutto-length cold-formed steel framing offers unparalleled efficiency in these projects, enabling rapid installation and ensuring compliance with stringent deflection and non-combustible material specifications.”

Despite federal policy uncertainty, the demand for sustainable building products has continued to grow at an impressive clip, which has boosted the market for coldformed steel framing in particular.

Most cold-formed steel products used today have a high recycled content, and the material can be recycled indefinitely—making it one of the most sustainable construction

materials on the market, and one that can contribute to green building certifications.

The manufacturing process for coldformed steel is also highly efficient. One of the most popular methods, electric arc furnace steelmaking, involves using high-current electric arcs to melt recycled scrap steel, which is then processed through rollers. This method emits significantly less GHG emissions than the blast furnace-basic oxygen furnace steelmaking process. “You get high recycled contents, excellent embodied carbon numbers, and you do so without having to clear-cut forests as you would for wood studs,” DesLaurier says.

Marino\WARE’s steel products also feature a choice of Product-Specific Type III Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) that provide project teams with detailed, transparent data on the environmental impact of its products.

One applies to all of the company’s coldformed steel framing products, regardless of production method. The other is a low embodied carbon EPD that specifically details the environmental advantages of coldformed steel products manufactured with the electric arc furnace method, allowing customers to make informed decisions on embodied carbon metrics.

“These efforts empower our customers and partners with the information they need to make environmentally responsible choices while reinforcing our dedication to reducing the industry’s carbon footprint,” McDaniel says.

The demand for cold-formed steel framing has risen to meet industry challenges.

AEC professionals benefit from increased versatility and flexibility in their designs.

Compared to its main competitors, coldformed steel is resistant to corrosion, mold, and fire, and impervious to termites and other pests, which all contribute to the longterm structural integrity of a project.

Cold-formed steel studs don’t warp, shrink, or crack like traditional wood studs. And with such a high strength-to-mass ratio, the material provides a higher level of structural strength while remaining lightweight and easy to work with. “This allows for more efficient material usage, smaller foundations, and lower transportation costs,” McDaniel says.

For example, Marino\WARE’s StudRite open-web stud system has one of the best strength-to-mass ratios of any stud available on the market. Though they are far lighter than traditional studs, the lip reinforced repetitive triangular cutouts and embossments help it achieve maximum structural integrity.

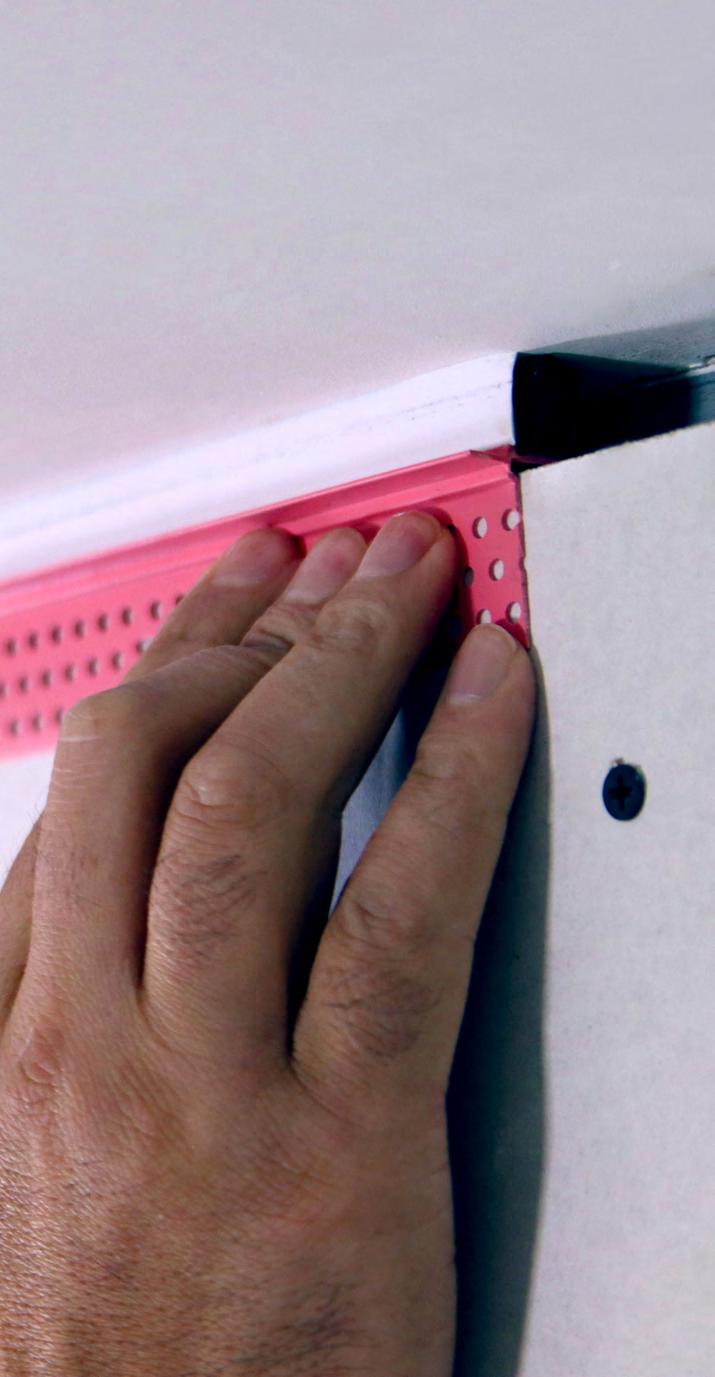

This superior performance makes it an excellent choice for projects in seismic zones or high-wind environments that require additional resilience and safety. “These features are especially important for multi-family residential buildings, hospitals, hotels, and other high-risk environments,” McDaniel says.

And with a growing focus on durability, the steel framing industry has made advancements in firestopping devices that, unlike traditional caulk, have no curing time, do not crack over the life of the structure, and minimize the need for maintenance every few years.

“The beauty of the next generation of preformed firestopping devices is that you don’t have to worry about any of that,” DesLaurier says. “Their efficacy is long-term versus having to go back and pull out the ceiling tiles or the wallboard to treat those.” Marino\ WARE’s HOTROD XL surface-mounted fire deflection device addresses these pain points by slotting directly between wall and ceiling joints, combining a flat deflection bead with compressible foam and intumescent tape for a full seal that provides one- and two-hour firestopping solutions.

“Cut-to-length cold-formed steel framing offers unparalleled efficiency ... enabling rapid installation and ensuring compliance.”

In recent years developers and design professionals have placed a greater emphasis on improving the acoustics of a space and exploring how framing materials can positively or negatively impact sound quality. Marino\WARE has responded to this shift in the market by focusing some of its research and innovation efforts with SoundGuard, a proprietary acoustically decoupled steel stud system. “A wood stud is stiff so it transmits more sound, whereas a steel stud is much better when it comes to sound transmission,” DesLaurier says.

SoundGuard was chosen as the primary framing material for a recent courtroom project where stringent sound control was critical for privacy. The design features architectural reveals that present a common challenge in achieving optimal acoustical performance.

Marino/WARE addressed this challenge by providing detailed technical data demonstrating that the SoundGuard system could achieve high sound transmission control ratings even with the reveals, ensuring

courtroom confidentiality. “SoundGuard was designed to overcome these challenges, offering a streamlined and highly effective acoustic solution that enhances performance while optimizing cost and installation efficiency,” DesLaurier says.

With labor shortages and rising material costs affecting the industry, firms everywhere are looking for innovative ways to cut down on time and resources for onsite construction. Developers and contractors have turned to modular construction and offsite prefabrication to address these issues, and steel framing systems—which are lighter and more flexible than wood—remain the ideal material for these practices.

“Costs are absolutely a driver in the industry,” Zuidema says. “On one of our projects we had an entire load-bearing cold-formed steel wall premanufactured and brought onsite to cut down on construction time,” versus stick-building the stud frame one at a time.

Most of Marino\WARE’s cold-formed steel orders are cut to specification, which significantly reduces wasted materials onsite. “This minimizes labor costs by eliminating or reducing onsite cutting, and streamlines installation, ultimately leading to overall project savings,” McDaniel says.

And the fact that cold-formed steel studs have gotten lighter means that instead of needing two workers to lift a tall stud into place, that process now only requires one, further cutting down on labor.