Thessaloniki

THE LADIES OF AIGAI A WALK THROUGH SEVENTEEN CENTURIES

EVANGELOS GEROVASSILIOU, THE WINE PIONEER

VERIA: THE PERFECT GETAWAY

BRUNELLO CUCINELLI

ZEGNA

KITON

TOM FORD

BERLUTI

BRIONI

ETRO

LORO PIANA

JACOB COHEN

SANTONI

CANALI

CORNELIANI

HERNO

MANDELLI

MOORER

ORLEBAR BROWN

PAUL AND SHARK

ISAIA

BOSS

VILEBREQUIN

POLO RALPH LAUREN

PT 01

MOOSE KNUCKLES

LARDINI

INCOTEX

BARBA NAPOLI

ELEVENTY

SERAPHIN

COLOMBO CASHMERE

PREMIATA

LUIGI BORELLI

CESARE ATTOLINI

FEDELI

THESSALONIKI, ON THE MOVE

BY THE GREECE – IS TEAM

THERE’S A HUM TO Thessaloniki this year – the sound of a city adjusting its rhythm. With the long-awaited opening of the metro, an engineering feat that doubles as an underground museum of antiquities, the conversation has shifted from “If ...” to “What’s next?” Test runs on the Kalamaria extension began in September, pushing the network seaward and signaling a more connected urban future.

Above ground, the city’s fabric is being rewoven. The Flyover, an elevated artery along the eastern ring road designed to ease the bottlenecks that have tested the patience of the city’s drivers for years, is moving steadily forward. At the port, record results and an approved master plan confirm a maritime hub that’s thinking in decades, not seasons, while anticipation is building for the Metropolitan Park taking shape on the grounds of the former Pavlos Mela army barracks.

Momentum is visible on the arrivals board, too. Thessaloniki Airport welcomed more than 4.3 million passengers in the first seven months of the year – a 7.3 percent increase year-on-year – with growth climbing to 10 percent by September. The hospitality sector is also keeping pace. New arrivals are broadening choice and raising the bar for quality. Cruise calls keep stacking up, while the port readies for its next leap. The challenge now is to channel that growth into better city experiences, higher value and more sustainable flows.

This is also a significant year for cultural institutions. The 66th Thessaloniki International Film Festival has cemented its place as one of the Mediterranean’s premier cinematic gatherings, spotlighting Balkan voices and bringing audiences back to the city’s historic theaters. Later this month, Open House will once again transform the city into a living museum of design and memory, turning buildings into stories and streets into itineraries. The Holocaust Museum of Greece, a testament to remembrance that will become an integral part of the living cityscape, has already entered its construction phase.

Between sea and skyline, the city is finding its stride. At last, Thessaloniki feels less like a promise deferred and more like a promise kept – and renewed.•

by

www.internistore.com · www.modabagno.gr · T. 2310 431000 · www.baxter.it

10 | HAPPENING NOW

Events, exhibitions and new openings for a richer urban experience.

32 | FAVORITE THINGS

Creative locals share their personal city tips.

38 | CITY SCENES

Thessaloniki, captured through the lens.

44 | HIGH EXPECTATIONS

A dynamic metropolis redefining its place at the heart of the Balkans.

54 | FOUR VOICES, ONE CITY

Cultural leaders reflect on history, art, memory and change.

62 | A WALK THROUGH SEVENTEEN CENTURIES

An itinerary of eleven landmarks showcasing the city’s enduring grandeur.

78 | THE LADIES OF AIGAI

At Aigai’s new museum, the forgotten queens of ancient Macedonia reclaim their place in history.

86 | ECHOES OF BLOOD

From the fall of a monarch to the silencing of a voice for peace, Thessaloniki has witnessed murders that changed Greece’s course.

94 | THE GATEKEEPERS

On the city’s eastern edge, a community with roots stretching back to Byzantine times.

100 | A THREAD OF SILK, A STORY OF GRACE

Near Serres, a woman keeps the rare art of sericulture alive, breeding silkworms and crafting silk treasures by hand.

106 | VERIA, A TROVE OF HISTORICAL AND NATURAL TREASURES

With its lush riverbanks, fine museums, Byzantine and postByzantine churches and some very good food, Veria is the perfect place for a mini break.

CONTENTS

116

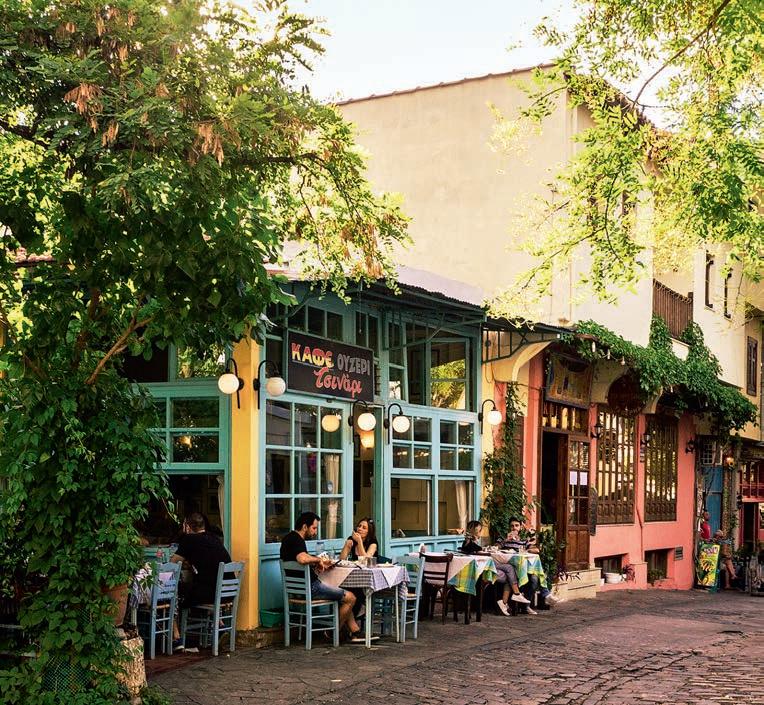

| WHAT IS A “KOUTOUKI”?

An insider selects 13 spots that still capture the warmth and spirit of this classic modest eatery.

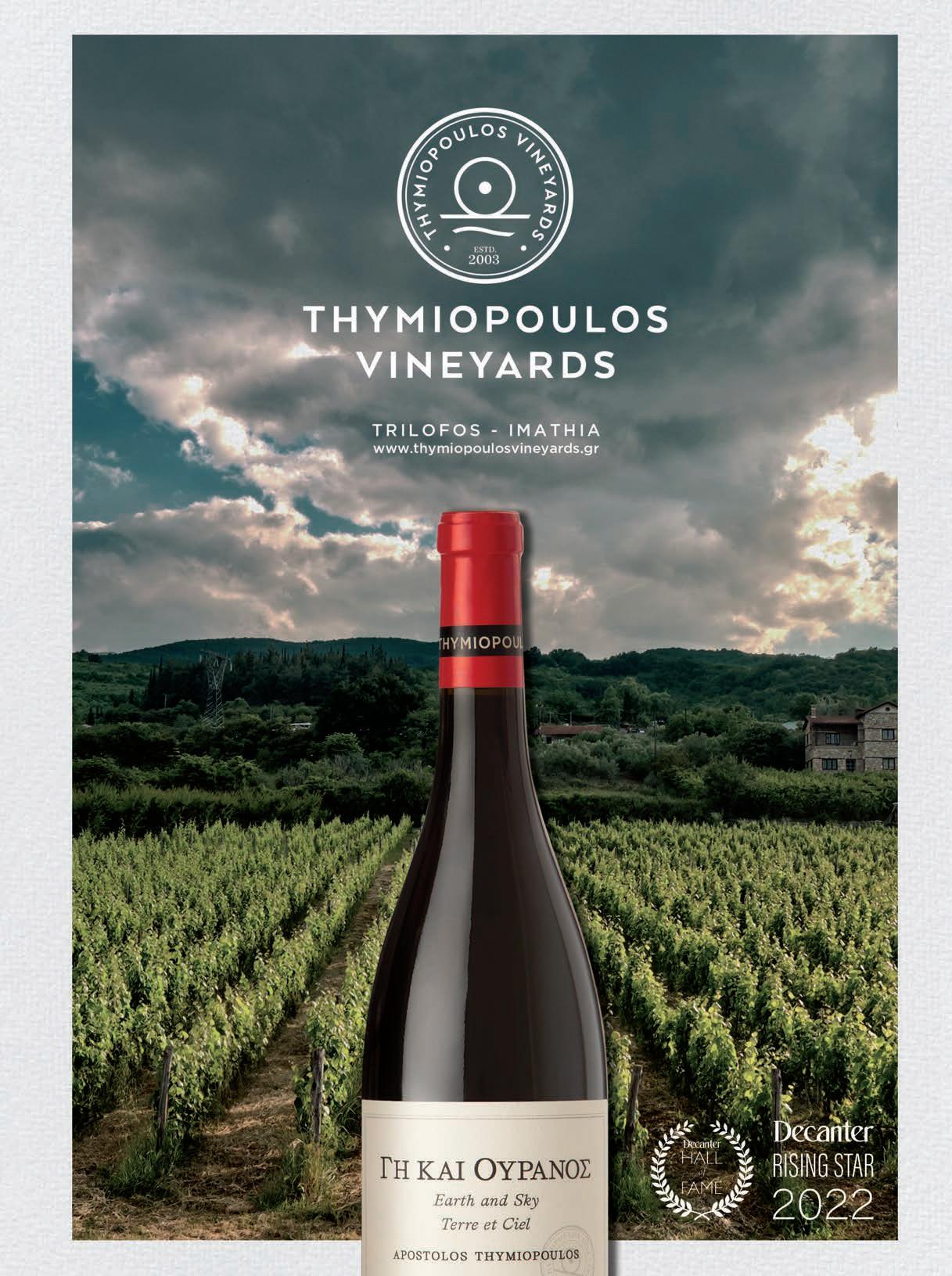

126 | IN LOVE WITH THE VINEYARD

Evangelos Gerovassiliou: The story of a true Greek wine pioneer, in his own words.

136 | STREET FOOD

From a postmodern bougatsa to woodfired pizza and pirozhki, street food here celebrates both tradition and innovation.

EXECUTIVE EDITOR

Alexis Papahelas

PUBLISHED BY:

Nees Kathimerines Ekdoseis

Single Member S.A. Ethnarhou Makariou & 2 Dimitriou Falireos, Neo Faliro, 185 47 Piraeus, Greece

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Giorgos Tsiros tsiros@kathimerini.gr

DEPUTY EDITOR

Nena Dimitriou nenadim@kathimerini.gr

EDITORIAL COORDINATOR

Niki Agrafioti

230408

ADVERTISING MANAGER

Kelly Lorentzou klorentzou@kathimerini.gr

COMMERCIAL INQUIRIES

Tel. (+30) 210.480.8227 Fax (+30) 210.480.8228 sales@greece-is.com emporiko@kathimerini.gr

PUBLIC RELATIONS welcome@greece-is.com

GREECE IS - ATHENS is a biannual publication, distributed free of charge. It is illegal to reproduce any part of this publication without the written permission of the publisher.

ON THE COVER

Artwork by Dimitris Tsoumplekas

Timeless elegance

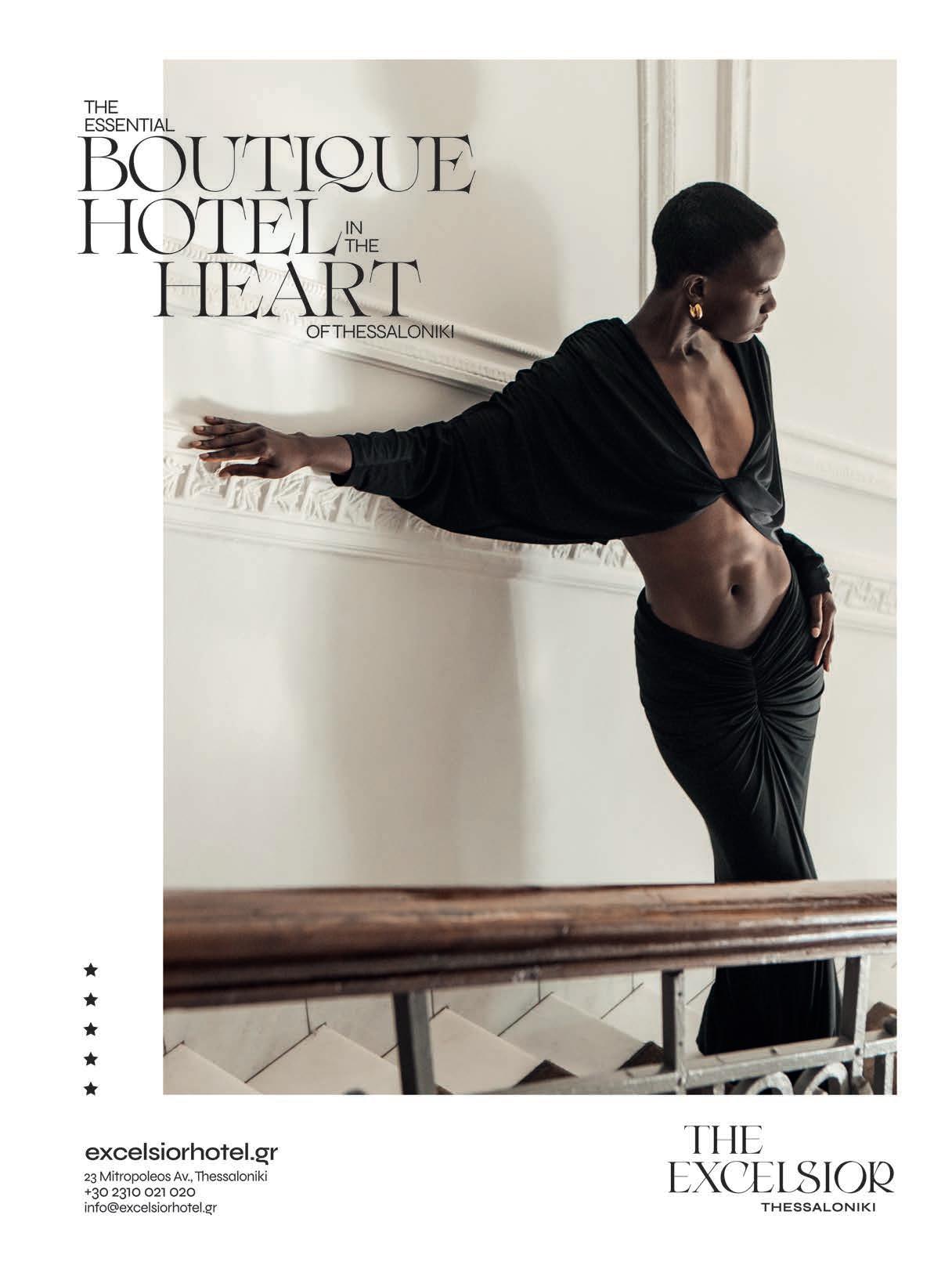

Discover the ultimate luxury address in Thessaloniki’s glittering promenade

Happening Now!

Events, exhibitions and new openings for a richer Thessaloniki experience.

BY THE GREECE-IS TEAM

Frida Kahlo: A Life in Images

“FRIDA KAHLO WAS STRATEGIC with the camera – she would gaze directly into the lens, head slightly turned to the side. She constructed a persona, she staged her own presence,” notes photographer and writer Pablo Ortiz Monasterio. Nearly sixty years after the Mexican artist’s death, Monasterio undertook the task of cataloguing the vast trove of photographs discovered in Casa Azul. Curated by Monasterio, the resulting exhibition, “Frida Kahlo – Her Photos,” unveils an intimate visual map of Kahlo’s life. For her, photography was never merely a tool of art; it was a mirror reflecting her relationship with identity, love, politics and, above all, the pain she never concealed. xenia georgiadou → Until 04/01/26, 2026 MOMus - Thessaloniki Museum of Photography. Warehouse A, Pier A, Thessaloniki Port Area, momus.gr

Echoes of War

THE EXHIBITION “Bringing History to Life,” co-organized by the Ministry of MacedoniaThrace and the National Historical Museum, transports visitors to the turbulent years of 1940-1944. In a vivid chromolithograph by Kostas Grammatopoulos, women ascend the rugged slopes of the Pindos Mountains, burdened with supplies yet radiant with courage, in an enduring image of daily heroism and self-sacrifice. Periklis Vyzantios’s painting “Mobilization in Delphi” (1940) captures the emotion sparked by the outbreak of the Greco-Italian War, while the works of Frederick Carabott depict the somber experience of captivity. A special section is dedicated to the Macedonian Struggle (1904-1908), featuring personal relics and archival materials from the Museum of the Macedonian Struggle Foundation. xenia georgiadou → Until 28/02/2026 Thessaloniki Administrative Building (Dioikitirio), Dioikitiriou Square, nhmuseum.gr

A City-Wide Museum

WHY IS THE YMCA building such a defining landmark of Thessaloniki? Which workspaces are redefining contemporary design? And what stories are hidden within the grand villas along Vasilissis Olgas Avenue? The answers will be revealed during Open House Thessaloniki, the city’s beloved architectural event, returning for its 13th edition. For one weekend, Thessaloniki itself becomes a museum, with architecture as its main exhibit. From Vardaris to the Castles and from the Old Slaughterhouses to Panorama, dozens of landmarks are opening their doors to the public. This year’s program also includes Open Walks, thematic tours that reveal lesser-known spots where architecture, history and daily life meet in unexpected ways. pantelis tsompanis → 22-23/11/2025, openhousethessaloniki.gr

Into the Depths of Time

STONE AND BONE TOOLS, pottery, sculptures, inscriptions, coins, bronze weapons, clay figurines, jewelry, votive images, anthropological, archaeobotanical, and archaeozoological material, and even contemporary artworks reveal the cave as an integral part of human existence. The exhibition “In the Cave: Stories from Darkness Brought to Light” unfolds across five thematic sections and features 296 objects dating from the Palaeolithic era to modern times. The exhiition explores the cave not merely as a geological formation but as a lived space, at times associated with trauma and confinement, at others with ritual, revelation and shelter.

xenia georgiadou

→ Until 31/12/2025 Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki, 6 Manoli Andronikou, amth.gr

Greece Through a Modern Gaze

THE UKRAINIAN PAINTER and art theorist Alexis Gritchenko bridged East and West through his visionary art. After his formative trip to Paris in 1911, he developed a distinctive visual language that fused the modernist movements of Fauvism, Cubism and Futurism with the Byzantine tradition. In 1919, he was offered the directorship of Moscow’s Tretyakov Gallery, an honor he declined before fleeing via Crimea to Istanbul, leaving everything behind. By 1921, he had settled in Greece, where he remained for two years, capturing the country’s light and spirit in radiant compositions. The exhibition “Alexis Gritchenko (1883-1977), The Greek Adventure: A Ukrainian Avant-gardist in Greece” traces his journey from Athens to Mystras, Delphi, Olympia, Thessaloniki and the islands, as he depicted ancient ruins, temples, and landscapes through a modernist gaze of bold geometry and explosive color. xenia georgiadou

→ From 22/11/2025 to 30/04/2026

MOMus-Museum of Modern Art, 1 Kolokotroni, Moni Lazariston, Stavroupoli, momus.gr

Between Light and Shadow

“I WAS OBSERVING the shades of green under the sunlight and the shadows as one leaf overlapped another. The organic shapes of the leaves often reminded me of the human figure,” says Philippos Theodorides, describing the inspiration behind a body of work in which nature is rendered not as landscape but as rhythm and breath. In his exhibition “The Sound Between the Leaves,” Theodorides presents collages, drawings, photographs, and paintings that deconstruct organic forms and reassemble them into pure, abstract shapes in an exploration of the quiet dialogue between light, shadow and movement. xenia georgiadou

→ Until 02/12/2025 Nitra Gallery, 51 Philippou, Roman Forum nitragallery.com

Wim Mertens in Concert

BELGIAN COMPOSER Wim Mertens returns to Greece for a one-night-only performance at the Royal (Vasiliko) Theater, presenting the world premiere of his new album “As Water Is to Fish.” The concert, two and a half hours long, interlaces new compositions and such career-defining works as “Struggle for Pleasure,” “Often a Bird,” and “Maximizing the Audience.” With just his piano and voice, Mertens crafts a spellbinding musical language that is minimalist in form yet profoundly affective. xenia georgiadou

→ 01/12/025

Royal (Vasiliko) Theatre White Tower Square

Operatic Magic with Angela Gheorghiu

WORLD-RENOWNED Romanian soprano Angela Gheorghiu comes for a one-night-only performance with the Thessaloniki State Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Spanish maestro David Giménez, nephew of the legendary José Carreras. The audience will enjoy Gheorghiu’s expressive voice, flawless technique and captivating stage presence, qualities that have established her as one of the most magnetic opera singers of our time, in this coproduction of the city’s Concert Hall and the Thessaloniki State Symphony Orchestra.

xenia georgiadou

→ 15/12/2025

Thessaloniki Concert Hall

25 Martiou & Paralia tch.gr

The Café on the Water

WITH ITS FRESH, contemporary aesthetic, the MOMus-Museum of Photography now welcomes visitors to redesigned spaces with a distinctly modern character. The ultramarine blue that defines the entrance and museum shop brings vibrancy and depth to the space, thanks to the design intervention of mma architects. Overlooking the port, the museum’s café appears to float above the water, offering a serene yet lively setting for coffee or brunch. The spot’s name “Hush” is inspired by the silence that precedes inspiration: that quiet pause before the shutter clicks and the perfect image is captured. stavroula kleidaria → Pier 1, Thessaloniki Port

The Legacy of Thessaloniki

MARKING THE CENTENARY of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and the 25th anniversary of the Teloglion Foundation of Art, the exhibition “Techni – Diagonios and the Museum That Never Happened” brings together over 600 works and archival materials from two landmark institutions: the Techni Macedonian Art Society, and the Small Gallery – Diagonios founded by Dinos Christianopoulos. From the 1950s to the mid-1990s, these two organizations shaped the city’s cultural core through pioneering exhibitions, educational programs, and artistic initiatives, leaving behind a lasting creative legacy. As curator and director Alexandra GoulakiVoutyra notes, “Although Techni and Diagonios seemed to move in opposite directions – Techni looking outward to the Greek avant-garde and Diagonios focusing on Thessaloniki’s own artists – they were driven by the same passion: to serve the city and support its younger generation.” xenia georgiadou

→ Until 10/02/2026

Teloglion Foundation of Art, A.U.Th. 159A Aghiou Dimitriou teloglion.gr

Fine wines for connoisseurs. Discover high quality wines full of aroma and taste at our stores and at Lidl prices.

7,99€ ANACHORITES

P.G.E. Peloponnese

BARRIQUE

3,99€

Nemea

5,99€ METAFYADES

P.G.E. Achaia

Wearable Thessaloniki

“THESSALONIKI IS A PLACE with an irresistible rhythm: offbeat yet elegant, layered with a rich heritage, standing timelessly at the crossroads of East and West, myth and modernity.” With these words, Zeus+Dione announced the opening of its first boutique in the city (46 Proxenou Koromila), along with the debut of a limited-edition silk accessory that doubles as a work of art: “Thessaloniki.” Designed by Em Prové in collaboration with the brand’s creative director Marios Schwab, the square scarf maps the city both geographically and emotionally, tracing its hills, landmarks, and boulevards in delicate, hand-drawn lines, interwoven with symbols and subtle references to the city’s Macedonian heritage. As Prové explains, “Each illustration began in pencil, then continued in black Indian ink, the brush moving carefully – but never too carefully. I like the line to breathe, to be elegant yet imperfect.” It’s the perfect way to carry a piece of Thessaloniki with you wherever you go. nena dimitriou → zeusndione.com

The DNA of Style

IN THE HEART OF THE CITY, Eleanna Tabouri introduces Nevro, a brand devoted to precision, craftsmanship and timeless tailoring. Her recently opened atelier and showroom present hand-sewn blazers, jackets and outerwear pieces of refined aesthetics, each garment meticulously crafted one stitch at a time. At the core of the collection lies what Tabouri calls the “blazer DNA,” a design identity that runs through every piece, even unexpected ones such as dresses with lapels and tailored collars. The name “Nevro” stems from the idea of the blazer as the neuron of a wardrobe – a vital point of connection, the centerpiece that ties everything together. Having studied Tourism Management in Milan, Tabouri credits the city for sharpening her aesthetic sensibility and shaping her creative perspective. Returning to Greece, she founded Nevro on principles of sustainability and slow fashion: limited stock, small runs and many pieces made to order. “Women in Thessaloniki,” she notes, “wear the blazer as it deserves to be worn, with strength, ease and confidence.”

nena dimitriou

→ @nevro_blazer, 8 Kalapothaki

Slow food for the soul

NEAR THE ROMAN FORUM, Soumaki is a small, unpretentious eatery where chef Giorgos Papounidis celebrates Greek cuisine with seasonal ingredients and traditional recipes. He serves hearty, flavor-packed dishes made with care, including his signature slow-cooked goat with pasta; young mutton with chickpeas and galomizithra cheese; meatballs with fries; and grilled pork knuckle. The menu is complemented by a fine selection of beers, tsipouro and bottled wines, all at refreshingly reasonable prices. Here, simplicity reigns and the food speaks for itself.

john papadimitriou → 79 Olympou

Retro Flavors, Fresh Start

LOCALS IN THESSALONIK i often start their day with a warm slice of sweet or savory bougatsa. This beloved breakfast staple, made of buttery layers of phyllo filled with either custard, cheese, minced meat or spinach, has found a new home at Tzeneral, a recently opened pâtisserie in the heart of the city. Blending retro aesthetics with authentic flavors, Tzeneral reintroduces Thessaloniki’s pastry star in the most delicious way. Each bougatsa is crafted daily with homemade filo dough, filled with classic choices and baked to golden perfection. Try the custardfilled or the mixed spinach-andcheese version, ideally paired with the homemade chocolate milk – thick, velvety and nostalgically comforting. pantelis tsompanis → 44 Pavlou Mela @tzeneral_zaxaroplasteio

Soul Connection

THE NAME F Ó LKI (Icelandic for “people”) is a fitting choice for a space built around interaction, creativity and community. This all-day spot has quickly become a favorite hangout for Thessaloniki’s young and vibrant crowd. Petfriendly and dotted with witty mottos across its walls, Φólki also hosts the work of a different local artist each month, turning coffee breaks into cultural encounters. Come for the exhibition, stay for the affogato. stavroula kleidaria

→ 5 Stratigou Makrygianni

A New Culinary Approach

ONE OF THESSALONIKI’S most talked-about chefs, Yiannis Loukakis, has joined forces with acclaimed pastry chef Spyros Pediaditakis to launch Orbital, a bold new gastronomic project that blurs the line between bakery and restaurant. Opened in September, Orbital produces its own breads and desserts on-site, each crafted with laboratory precision and the warmth of a neighborhood bakery. Diners can enjoy them in-house or take them home. Among the standout dishes are the much-discussed rooster schnitzel with pickled okra and mashed potatoes, and the traditional sourdough pie filled with mutton pastirma and melted kasseri cheese, two creations already making waves on the city’s dining scene. The concise wine list offers every selection by the glass, while the rakí from Iliana Malihin in Rethymno, made from native Thrapsathiri and Liatiko grapes, adds a distinctly Cretan touch. john papadimitriou → 3 Platonos

Favorite THINGS

CREATIVE LOCALS OFFER THEIR OWN TIPS

BY STAVROULA KLEIDARIA

ATHAN DAPIS

Visual artist @athandapis

1. The MOMus museums (at the port, the TIF and the Lazariston Monastery) always have interesting exhibitions; the Byzantine Museum is an architectural masterpiece, designed by architect Kyriakos Krokos.

2. You can see up to 15 UNESCO cultural heritage monuments, most within walking distance of each other. From the Church of Panaghia Chalkeon (2 Chalkeon) with its splendid architecture to the Church of Aghioi Apostoli (1 Olympou) with its frescoes and mosaics, they are all so important.

3. I prefer quiet places such as Philia (Navarinou Square) or Purovoku (3 Karipi), which has taken cocktails to another level entirely. My “nightcap” is often a sandwich from Kantina Othonas in Nea Paralia.

4. The colorful atmosphere at Piece of Cake (19 Chrysostomou Smyrnis) goes perfectly with its very good coffee and delicious cakes. Must-tries are the red velvet and the carrot cake. A timeless classic is the Kitchenbar at the port, with the most beautiful views of the city.

5. On Sundays I wake up late. I usually have my coffee, and later my lunch, at Kappu (16 Palaion Patron Germanou) before I head to Toumba Stadium to watch PAOK play.

1. Cultural destination

2. Only in Thessaloniki

3. Night out

4. Favοrite coffee place

5. Sunday ritual

ISMINI TORNIVOUKA

Director of Operations

Tor Hotel Group

@isminious

1. The Museum of Byzantine Culture is Thessaloniki’s quiet jewel, a serene, beautifully curated space that reflects the timeless spirit of Byzantine art. It’s where you feel the city’s soul most deeply: contemplative and eternal.

2. A walk on the New Waterfront captures the best of Thessaloniki: the sea breeze, the light, and the rhythm of the city. A koulouri or a creamy bougatsa in hand completes the ritual. But what truly defines the city is how easily you run into friends there.

3. Dinner at Olympos Naoussa is pure Thessaloniki elegance, a legendary restaurant recently revived. And then there’s Gorilla Bar (3 Veroias) : vibrant, eclectic and full of life, the kind of place where everyone somehow knows everyone else.

4. Shed (11 Patriarchou Dionysiou) and Peach Boy (44 Ermou) are my go-tos. Both capture the modern Thessaloniki spirit: creative, stylish and effortlessly welcoming.

5. Brunch with the kids at Ergon Agora (42 Pavlou Mela) is our family tradition. Lunch at Clochard (10 Komninon & 23 Mitropoleos) is a timeless Thessaloniki experience.

The revival of a legend

Nearly 100 years after its first opening, Olympos Naoussa has returned to Thessaloniki’s waterfront. True to the Greek urban cuisine values and the city’s gastronomic traditions, it awaits you to discover it.

LABRINI STAVROU

Co-founder of the fashion brand Ancient Kallos @labrini_stavrou

1. Every November, Thessaloniki hosts its International Film Festival, with premieres, screenings and discussions that celebrate contemporary cinema. It's become a key event for film lovers and creators alike.

2. What I love about Thessaloniki is how quickly you can connect with people. Ten minutes for a quick coffee at Proxenou Koromila to meet a friend, then a walk by the sea, and somehow the day already feels full.

3. I’m very much a summer person, and one of my favorite spots is the rooftop of the ON Residence hotel (5 Nikis), with the city stretched out below. In winter, if there isn’t a good play to catch, I usually head to Le Cercle de Salonique (7 Vasileos Irakleiou)

4. It’s hard to choose just one. I go to Tom Dixon (6 Chrisostomou Smirnis) for the interiors; it’s a place where design becomes part of the experience. Local (17 Palaion Patron Germanou) is my go-to spot with friends, where a coffee easily turns into drinks.

5. Sundays often start with brunch at the Hyatt Regency; it’s my little weekend indulgence. Refined flavors, great coffee and an easy, relaxed atmosphere.

GEORGE DORAS

Founder of Le Cercle de Salonique @georgedoras

1. Cultural destination

2. Only in Thessaloniki

3. Night out

4. Favοrite coffee place

5. Sunday ritual

1. The city’s multicultural past is still visible as you walk through it. The Roman Agora feels like an open-air museum, but even more exciting are the small galleries and artist-run spaces such as Volume R Concept Space (24 Paparigopoulou) and French Fries – French Kisses (12 Pavlou Mela).

2. Even on a bad day, Thessaloniki’s sunset can lift your mood. After seven years here, I still catch myself taking photos of it. It’s the only city where I never get tired of watching the sun sink into the sea.

3 Thessaloniki’s nightlife never disappoints; there’s something special for every taste. Folki (5 Stratigou Makriyianni) is a unique little wine bar full of thoughtful details and youthful energy. For aperitivo lovers, Giulietta Spritzeria (33 Palaion Patron Germanou) serves superior spritzes.

4. A coffee spot I appreciate for its quality and for a minimalist vibe that reminds me of Japan is Hue (38 Filippou), with its own in-house roastery. When I need a little city break, I go to Estet Café (78 Olympou) for a coffee and their signature cheese sandwich with homemade coffee-sriracha sauce.

5. Sunday is my breakfast-in-bed day, usually with a classic Greek breakfast from Paradosiako (27 Aristotelous), a Thessaloniki staple for over 25 years, but I will leave the house for dessert at the Pink Dot Café at Apollonia Center.

KONSTANTINOS MATHEAS

Architect

@kmatheas

1. Every stroll through Thessaloniki feels like a privilege, and you don’t need a map. There’s something magical about wandering around the center. A simple walk from Ano Poli down to the sea is enough to feel the city’s grandeur as you drift through time and soak up its stories and secrets.

2. Υou can wake up and go for a morning walk or run along the New Waterfront, a project that’s transformed the city, and watch the sun reflect off the anchored ships and port cranes against the majestic backdrop of Mt Olympus, once home to the gods of ancient Greece.

3. Thessaloniki’s nightlife caters to every taste and I’ve recently become fascinated by the historic Vardaris neighborhood. The triangle formed by Aghiou Dimitriou, Karaoli & Dimitriou ton Kyprion and Lagkada streets is now dotted with new bars and eateries.

4. Pelosof (22 Tsimiski) stands out among Thessaloniki’s coffee destinations. Located in the inner courtyard of a historic downtown building, it has added contemporary design elements to the original grandeur of the building.

5. Instead of settling in a café or heading out for brunch, I grab a koulouri or bougatsa and make my way to Pier 1 at the port. There, I sit with friends on the dock, as gentle sea breezes sweep across the Thermaic Gulf. It’s a simple ritual, but it captures the city’s unhurried weekend pace.

5.

1.

Cultural destination

2.

Only in Thessaloniki

3.

Night out

4.

Favοrite coffee place

Sunday ritual

SYNTHIA SAPIKA

Journalist, General Director ERT3 @synthiasapika

1. At the Venizelou metro station, you’ll see remains of the Decumanus Maximus, the east-west Roman road, and hear echoes of the city’s ancient commercial splendor. The Kostakis Collection at Moni Lazariston (21 Kolokotroni), a priceless art legacy, is just a part of the MOMus museum network.

2. Take a boat ride and see the city from the sea. As the poet says, “Only from the water should Thessaloniki be seen; never dare to look at her from the land.” Back on land, wonderful will lead you to the Trigonion Tower and the Yedi Kule.

3. I love concerts at Mylos (56 Georgiou Andreou) with international bands, small theatres staging independent productions, intimate live gigs in bars scattered throughout the center, and having drinks with my friends at hangouts such as Souel (16 Pavlou Mela).

4. Unfortunately, I no longer have the luxury of lingering over coffee for hours. Ιf there is one place to mention, however, it’s the city’s oldest café-bar, De Facto (19 Pavlou Mela), the place where I spent my teenage years.

5. My mother says that if you want to know a city, you should visit its cemeteries. Zeitenlik, an Allied military cemetery and WWI memorial park, is the largest military cemetery in Greece.

CITY SCENES

A MAGICAL MEETING POINT

Every evening, as the sun sinks below the horizon, Pier A at Thessaloniki’s port comes alive. The pier, whose former warehouses now serve as Thessaloniki International Film Festival venues, has become a beacon for residents seeking a touch of cinematic magic in their own lives. They often find it here, too, thanks to the waterfront’s unique atmosphere and ever-changing light.

IN THE LIGHT OF DUSK

As twilight falls, the park near the YMCA takes on a new glow. Mount Olympus seems almost within reach as shadows grow longer and the lights along the seafront begin to sparkle. The statue of Alexander the Great, framed in part by a row of shields and Macedonian long spears, has stood here proudly since 1974. Today, with skateboarders gliding across the marble that surrounds it, the statue and the scene form a reminder of the city’s timeless balance between past and present.

URBAN BALANCE

Every day, joggers and walkers fill the promenade of the New Waterfront, exercising or strolling along its six kilometers. Since its completion in 2013, Thessaloniki’s residents have taken pride in this landmark urban redevelopment, where a swath of greenery skirts the sea, creating a harmonious space in which to relax, stay fit or simply connect with the city’s coastal rhythm.

HIGH EXPECTATIONS

From major infrastructure projects to a renewed cultural landscape, Thessaloniki is asserting itself as a dynamic metropolis at the heart of the Balkans.

BY JOHN PAPADIMITRIOU

by

Construction is already underway on the city’s Flyover project.

AANYONE DRIVING ALONG

Thessaloniki’s ring road these days can witness first-hand the impressive progress of the Flyover project, a new elevated expressway that will double the capacity of the city’s main traffic artery. Scheduled for completion by May 2027, the Flyover is designed to handle up to 10,000 vehicles per hour and is expected to significantly ease congestion in and around the city.

For now, however, traffic woes persist, especially during the morning rush. But at least drivers won’t be waiting decades, as they did for the city’s long-anticipated metro system, which is finally delivering results. Almost a year after the inauguration of the main metro line, Thessaloniki is finally beginning to reap the benefits of this long-awaited project.

The numbers speak for themselves: in its first ten months of operation, the Thessaloniki Metro recorded 22 million validated tickets, proving that many residents are already using it daily, reducing car traffic across the city. The metro isn’t just easing traffic; it’s revitalizing entire neighborhoods. Along Delfon Avenue, east of the city center, three new stations – Efkleidis, Fleming, and Analipsi – have sparked renewed activity, and property values there have soared in response.

According to Bank of Greece data, apartment prices in Thessaloniki rose by an average of 7.3% in the second quarter of 2025 compared to the same period in 2024, outpacing even Athens, where property values increased by 5.9% over the same time frame.

THE NUMBERS SPEAK FOR THEMSELVES: IN ITS FIRST TEN MONTHS OF OPERATION, THE THESSALONIKI METRO RECORDED 22 MILLION VALIDATED TICKETS.

The forthcoming metro extension to Kalamaria, with five new stations expected to open by late March 2026, is also energizing the city’s eastern side. Meanwhile, despite the lingering presence of “For Rent” signs on central streets such as Tsimiski and Mitropoleos, Thessaloniki’s urban core appears to be experiencing a revival. New retail chains are opening, new hotels are joining the city’s hospitality scene – among them the recently launched NYX and a new five-star Electra Group property under construction near the YMCA – and new commercial pockets are emerging. Egnatia Street, which for two decades was hidden behind metal sheets and construction dust from the metro works, is thriving again. Around the Church of the Acheiropoietos, near the Aghia Sofia and Venizelou stations, a lively new food and café scene has also sprung up.

Projects Everywhere

Beyond the metro, Thessaloniki’s resurgence is also being driven by a series of smaller-scale projects that promise to make the city more beautiful and boost its economic growth even further. Eleftherias Square is set to be transformed into a Memorial Park honoring the victims of the Holocaust, and the redevelopment of the Aristotelous Axis is awaiting final approval. Major changes are also in store for Thessaloniki’s seafront.Work is progressing on the creation of an additional deck along the old promenade on Nikis Avenue. The

Consistency. Is an Estate of Mind.

quay stretching from the White Tower to the port will resemble a “ship” moored along the old waterfront: a boardwalk extending 12 meters over the water and stretching 1.1 km in length. The project includes a new bicycle lane and a tactile path for the visually impaired. Once completed, it will allow residents and visitors to enjoy their stroll along the city’s historic waterfront without the current congestion of pedestrians, cyclists and scooters sharing a narrow strip of land.

If the famous work “Umbrellas” by sculptor George Zongolopoulos is on your list of Thessaloniki must-sees, you might be disappointed to find it missing – for now. The 13-meter-high, stainless steel sculpture, one of the city’s most iconic and most photographed landmarks, has been taken to Athens for restoration. Originally installed on the New Waterfront in 1997, when Thessaloniki was the European Capital of Culture, the work has endured harsh winds as well as the weight of countless love locks that couples used to hang from its rods – a romantic habit that had to be stopped to preserve the sculpture.

Just west of that spot, another major infrastructure project is advancing along the seafront: the redevelopment of Thessaloniki’s commercial port, a €180 million investment that includes the expansion of Pier 6. Once completed, the port will be able to accommodate the largest mainline container ships, significantly enhancing its competitiveness in the global market.

Plans are also in motion to pedestrianize the southern section of Aghia Sofia Street, which will make that central area more welcoming to walkers.

A New Cultural Landmark

Alongside Thessaloniki’s urban transformation, the past three years have also brought a remarkable cultural awakening. The Thessaloniki International Film Festival continues

THE NUMBERS SPEAK FOR THEMSELVES: IN ITS FIRST TEN MONTHS OF OPERATION, THE THESSALONIKI METRO RECORDED 22 MILLION VALIDATED TICKETS.

to shine as the city’s flagship event, drawing audiences and artists from around the world. Also on the city’s annual calendar is the Dimitria Festival, Thessaloniki’s oldest cultural event. With international collaborations –such as this year’s partnership with composer Goran Bregović – and bold performances such as last year’s Tiger Lillies concert at the Olympion, the festival is once again drawing crowds from across Macedonia and the Balkans.

The most significant recent development, however, came in mid-October, when Minister of Culture Lina Mendoni announced a major cultural milestone: the Kostakis Collection, a treasure trove of 1,275 works of Russian Avant-Garde art, some of which are currently displayed at MOMus–Museum of Modern Art, will soon be permanently housed in the historic S2 building of the former FIX brewery complex. The venue will also host the State Orchestra of Thessaloniki.

“The permanent exhibition of the Kostakis Collection will help transform Thessaloniki into a cultural destination of international importance, as the Russian Avant-Garde is one of the most influential artistic movements of the 20th century,” says Epaminondas Christofilopoulos, president of MOMus.

At long last, Thessaloniki seems ready to make the most of its cultural legacy; hopefully, it will continue to do so. After all, it takes more than infrastructure to make a city bloom.•

MonAsty Hotel Thessaloniki Autograph Collection

Where City Living Meets Serenity

FOR TODAY’S TRAVELER , a hotel is more than comfort and design –it’s about character and a sense of story, too. In Thessaloniki, few places capture that balance as gracefully as MonAsty, Autograph Collection.

Nestled in the vibrant heart of the city, where Byzantine echoes meet contemporary rhythms, MonAsty stands as a sanctuary of quiet elegance and urban energy. Its name – “Mon” for monastery, “Asty” for city –reflects the dialogue between heritage and modern sophistication.

Each room and suite feels like a personal retreat, with bespoke furnishings, textured materials and subtle references to Byzantine silk weaving. Culinary experiences further the narrative: Botargo Restaurant celebrates Mediterranean flavors with understated finesse, while Samite Gastro Bar reimagines Byzantine-inspired tastes through a modern lens. Above it all, the Ennea Rooftop Bar offers panoramic views of the Thermaic Gulf, with crafted cocktails and curated DJ sets in perfect harmony with the city’s nocturnal pulse.

Managed by SWOT Hospitality, MonAsty delivers an experience of authenticity and refined ease; an invitation to discover Thessaloniki’s layered spirit, where history, art and contemporary life blend seamlessly. n

• www.monastyhotel.com

• 45 Vasileos Irakleiou, Thessaloniki

@monasty.hotel

@MonAstyThessaloniki

Alexandra Goulaki -Voutyra

Director, Teloglion Foundation of Art, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki

“FOR ME, THE CITY is Dinos Christianopoulos’s short stories. I had read them when I was younger, but now, through the exhibition ‘Techni – Diagonios and the Museum That Never Came to Be’ I returned to them with the maturity to truly understand what he was talking about.”

Christianopoulos (1931-2020) was one of Thessaloniki’s most distinctive literary figures – a writer of poetry and prose, and the founder of Diagonios, the legendary postwar magazine and cultural circle that nurtured an entire generation of northern Greek artists and intellectuals. Alongside Techni, the city’s pioneering art association founded in the 1950s to promote contemporary Greek art, Diagonios helped shape Thessaloniki’s modern cultural identity.

Voutyra remembers the 1970s, when these two institutions defined the intellectual life of the city. “Every Tuesday there was a lecture at Techni, in a small hall on Komninon Street. Afterwards we’d go to Diagonios, in the arcade between Mitropoleos and Tsimiski. There you were welcomed by Christianopoulos himself, standing before portraits of Cavafy and Tsitsanis, and he would personally guide you around, eager to introduce you to the city’s future, its young artists.”

The exhibition “Techni – Diagonios and the Museum That Never Came to Be," at the Teloglion Foundation of Art in Thessaloniki until February 10, 2026, celebrates the foundation’s 25th anniversary and revisits that vibrant era when the city’s cultural scene was being redefined through dialogue, experimentation and friendship. Voutyra believes Thessaloniki has always had this spirit because it is, above all, a city of youth. “You see young people in the streets, sometimes joyful, sometimes angry, and you know that they are the source of its rhythm and its energy.”

For her, Thessaloniki is also the music of Aimilios Riadis, which she first encountered as a student at the State Conservatory, as well as long walks along the seafront and through Ano Poli.

“Thessaloniki is a city made for walking – from monument to monument, from its Byzantine churches to its archaeological sites and museums. But with scarce parking, crowded pavements and constant noise, visitors are often deprived of the simple pleasure of exploring it on foot.” She acknowledges, however, that the city has improved greatly in recent years. “The entire waterfront has been redesigned with new thematic parks, and Ano Poli, too, has become more accessible. The city’s markets have been beautifully restored. Yet progress must go hand in hand with balance; I sometimes fear that authenticity is slipping away.”

She closes our conversation with an image that, for her, captures Thessaloniki’s enduring allure: “The city has been portrayed countless times in Greek art, in every style and medium, yet the subject is always the same. Ιts sunset.”

Cultural leaders reflect on Thessaloniki’s layers of history, art, memory and change.

Four Voices, One City

BY XENIA GEORGIADOU

PHOTOS: PERIKLES MERAKOS

FOR THOULI MISIRLOGLOU, the small 14th-century Byzantine Church of Agios Nikolaos Orphanos, perched on the edge of Ano Poli, remains a personal refuge. “Its exquisite frescoes and the lovely garden with its orange trees help you shut out the city’s noise and gather your thoughts.”

When asked to choose works that capture Thessaloniki, she pauses. There are, she says, easy and obvious ways to answer – but the city’s memory runs deep, layered with stories that can’t simply be left out.

If Thessaloniki were a film, she says, it would be “Salonika, Nest of Spies” (1936) by Wilhelm Pabst. “For some reason, it still feels like a compelling reference – though it isn’t really about Thessaloniki, it captures a fragment of its character, seen from a slightly off-center angle.”

If the city could be revealed through the pages of a book, her choice would be “Salonika: City of Ghosts” by the British historian Mark Mazower. “Mainly because it prompted us to look at major parts of our own history, such as the Holocaust and the story of the city’s Jews, through the prism of trauma.”

And if Thessaloniki could be translated into color, it would have been painted by the self-taught artist Nikos-Gabriel Pentzikis. “Because his subjects reflected the many layers and meeting points that compose the city.”

She believes Thessaloniki is changing – not only in terms of infrastructure, but also in its intentions and self-image. What could truly support this transformation, she says, would be for people capable of formulating a shared vision to sit together and shape a coordinated plan for how to make the best use of the city’s potential.

“There should be a clear calendar of Thessaloniki’s major cultural events,” she adds. “It would help both residents and visitors plan what they want to see – rather than discovering things by chance at the moment they happen.”

RAISED IN THE LEAFY suburban village of Filiro overlooking Thessaloniki, Simos Papanas believes that all you need to grasp the city’s long and often contradictory history is to walk through it. “Even if you know nothing about it, history will find you on every street. In the center, among postwar modernist apartment blocks, you come across Roman ruins, Bauhaus details, Art Nouveau façades, Byzantine churches and eclectic buildings – testimonies to the city’s many layers of influence. In Ano Poli, you’ll meet its Balkan soul and the legendary walls built by Emperor Theodosius the Great as an act of repentance for the massacre of Thessalonians in the Hippodrome in AD 390.”

“Every step here,” Papanas says, “carries a historical weight that can transport you, without warning, from past to present, from East to West.”

His favorite spot is the Byzantine Bath in Ano Poli, known as the Koule Hamam. “This bathhouse, part of a tradition from the Roman era that survived through Ottoman times, bridges different periods of the city’s history.”

If Thessaloniki were a song, it would be “Jasmines and Minarets” (“Giasemia kai Minaredes”) by Aimilios Riadis, the Thessaloniki-born composer (1880-1935) often described as the “Schubert of Greece.”

If Papanas could change one thing, it would be the way his fellow citizens treat public space. “Because of my work, I travel constantly, and nowhere else is graffiti so out of control. Here it’s no longer about creativity but about the idea that anyone can grab a can of paint and scribble whatever they like, wherever they like.”

Another welcome change is already underway; Papanas is looking forward to the day when the State Orchestra will finally have a permanent home, sharing space with the Kostakis Collection in the historic former FIX brewery complex, now undergoing renovation.

Simos Papanas

Director, State Orchestra of Thessaloniki

“THESSALONIKI IS the image that unfolds before your eyes as you approach the shore from the sea. If you set off in a small boat from Karabournaki toward the city center, the splendor of the city reveals itself: the walls, Ano Poli and the Eptapyrgio.”

Having grown up in Patras, she is well acquainted with open seascapes, yet what she finds unique about Thessaloniki is the way the city seems to rise above the water, built in layers that connect land and sea.

She finds it difficult to name a single place that inspires or calms her, yet she speaks with genuine passion about an orchestra. “I feel uplifted every time I attend a concert by the State Orchestra of Thessaloniki, whether at the Concert Hall, in the Ceremonial Hall of the Aristotle University, or in the foyer of the Archaeological Museum, where once a month they perform chamber music.”

Thessaloniki is known for its unhurried pace, yet she would like to see a little more momentum. “If I could change one thing, it would be the pace at which things move forward,” she says. She would also love to see the museum’s surroundings upgraded. “Ideally, I would want an extension to display more of our collection’s unique finds, which are now confined to a very limited space.”

The object that best symbolizes Thessaloniki for her is a marble base inscription preserved in the Archaeological Museum. It’s part of a pedestal bearing statues of Philip II’s family, dating to the 2nd century AD. The inscription reads: “Thessalonike, daughter of Philip, Queen.”

“I associate it with the city because it bears the name of the woman from whom the city itself took its own.”

Thessalonike, daughter of Philip II and the Thessalian Nicesipolis of Pherae, and half-sister of Alexander the Great, married Cassander, the founder of the city, who named it after her.

The inscription is displayed in the gallery dedicated to the city’s Roman past. “For me, it’s the most profound link between Thessaloniki and its history; a tribute to its queen, about whom we know so little.”

Anastasia Gadolou

Director General, Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki

A Stroll Through Seventeen Centuries

Thessaloniki is an architectural palimpsest, where every corner reveals the layers of eras, faiths and ideas that shaped it. This short walk takes in eleven buildings whose magnificent architectural elements testify to a city’s grandeur across the ages.

BY TASOS PAPADOPOULOS, ARCHAEOLOGIST

1

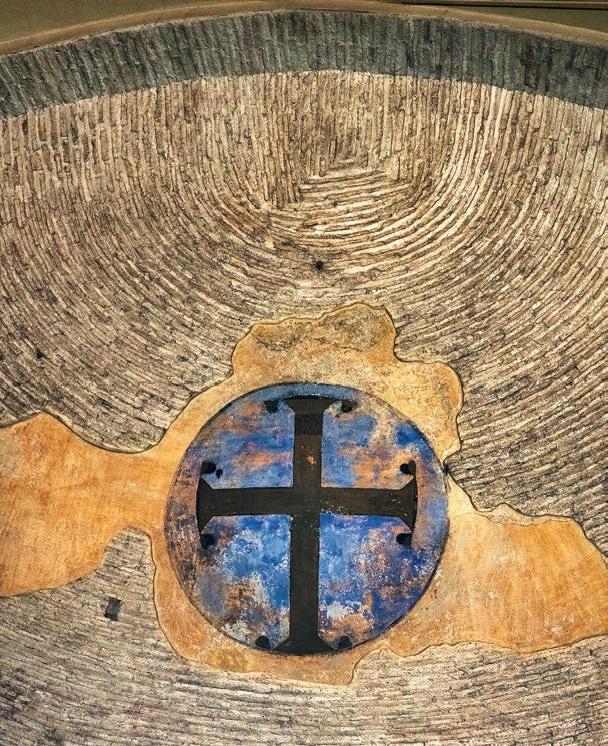

THE ROTUNDA

Early 4th c. AD, 5 Aghiou Georgiou Square

FEW MONUMENTS BUILT 1,700 years ago still retain their original roof. What’s more, for the Rotunda in Thessaloniki, that roof is no ordinary structure; it’s a monumental crowning dome twenty-five meters wide. Yet it is not its architectural splendor, nor even its archaeological significance that is the most important aspect of the Rotunda. It has a deeper symbolic worth as one of the very few buildings to have served three of humanity’s great faiths: the ancient GrecoRoman pantheon, Christianity, and Islam.

The monument was commissioned by the Roman Emperor Galerius in the early 4th century AD as the crowning element of an ambitious architectural complex that also included a hippodrome, an octagonal throne hall, a Roman basilica, baths and, of course, the triumphal Arch of Galerius (Kamara), where the emperor is shown victorious over the Persians in distant Mesopotamia. Long thought to have been intended as Galerius’ mausoleum, the Rotunda is now believed by most scholars to have been built as a temple, perhaps dedicated to Zeus, Ares or perhaps all the gods of Olympus, much like the Pantheon in Rome.

A few decades later, at the end of the 4th or the beginning of the 5th century AD, the Roman Rotunda was converted into a Christian church and remained one for over a thousand years. Christianity was spreading throughout the Roman Empire, and ancient beliefs were slowly but steadily disappearing. The Rotunda’s magnificent mosaics, true masterpieces of early Byzantine art, date from this early Christian phase.

In 1591, when Thessaloniki was part of the Ottoman Empire, the Rotunda was transformed once again, this time into a mosque. Even today, a tall, slender minaret – the only one to have survived in the city – rises beside the original Roman building. The Rotunda stands as the living imprint of Thessaloniki’s timeless soul.

2

THE CHURCH OF THE ACHEIROPOIETOS

Late 5th c. AD, 54-56 Aghias Sofias

IN THE HEART OF THE CITY beside the Aghia Sofia metro station stands the early Christian Church of the Acheiropoietos, the oldest church in Thessaloniki still in use today.

A three-aisled basilica built in the late 5th century AD, it has endured for more than fifteen centuries. Its evocative name, Acheiropoietos (“Not made by human hands”), recalls a miracle that occurred during the Byzantine era; according to tradition, an icon of the Virgin and Child changed form by itself. Because this transformation occurred without human intervention, the icon – and, by extension, the church – came to be known as Acheiropoietos.

Inside the church, a sense of serenity prevails. The marble floor, the graceful columns crowned with exquisitely carved early Christian capitals, the galleries and the abundance of light streaming through dozens of windows give the ancient sanctuary a warm feeling. In the north aisle, Roman mosaics survive from an earlier structure, possibly a bathhouse. Only fragments of the original decorations remain, including some mosaic work on the arches of the arcades, where the name of Andreas, Bishop of Thessaloniki, is still visible. In the south aisle, a rare fragment of a 13th-century fresco depicts the Forty Martyrs of Sebaste. When Thessaloniki fell to the Ottomans on March 29, 1430, Sultan Murad II, the city’s conqueror, converted the Church of the Acheiropoietos into a mosque. A succinct dedication, elegantly framed in a medallion, was carved onto the eighth column of the north aisle: “Sultan Murad Khan conquered Thessaloniki, year 833 of the Hegira.” After the city’s liberation in 1912, the church was once again used for Christian worship.

HAMZA BEY MOSQUE

Alkazar, 1467-1468, 49 Egnatia

EVERY CIVILIZATION

LEAVES its mark on the ever-changing fabric of cities. The Ottoman period in Thessaloniki lasted nearly five centuries and gifted Thessaloniki a number of significant monuments. The Hamza Bey Mosque, the oldest mosque in the city, was built between 1467 and 1468 by Hafsa Hatun in honor of her father, the Ottoman official Hamza Bey. According to historical accounts, Hamza Bey met a gruesome fate in Romania, executed in public by either Vlad III Țepeș – the historical figure who inspired the character of Count Dracula – or by Stephen III the Great.The impressive mosque dominates the junction of Egnatia and Venizelou streets. Its core, almost square in shape, is crowned by a majestic dome. It features a spacious courtyard with imposing columns, many of which were repurposed from earlier Christian or Roman monuments. Following the Greco-Turkish War and the subsequent population exchange between Greece and Turkey in 1923-1924, Thessaloniki’s Muslim inhabitants were forced to leave the city. The mosque soon fell into disuse; a few years later, it was converted into a cinema named “Alkazar,” a name still familiar to most Thessalonians today. In the 1980s and 1990s, the building suffered significant damage through unsympathetic renovations by private owners, who turned the interior into a series of shops selling imitation leather goods.

With the construction of the nearby Venizelou metro station, the mosque has been included in a restoration program. In the near future, it will reopen to the public as a cultural venue, reclaiming its rightful place as one of Thessaloniki’s architectural and historical landmarks.

SAUL MODIANO ARCADE

1881

17 Eleftheriou Venizelou

THE HISTORY OF THE MODIANO family is synonymous with the cosmopolitan spirit of old Thessaloniki. Arriving from Livorno, Tuscany, in the 18th century, the Modianos became part of the city’s large Sephardic Jewish community and soon left a lasting mark on Thessaloniki’s urban and social life. The family patriarch, Saul, rose from humble beginnings as a poor orphan to become one of the wealthiest men not only in Thessaloniki but in the entire Ottoman Empire. Among the architectural legacies left by the Modianos (including their family mansion, which now houses the Folklife and Ethnological Museum of Macedonia-Thrace, and the famous Modiano Market, recently restored at the junction of Ionos Dragoumi and Vasileos Irakleiou streets) is the remarkable Saul Modiano Arcade. Completed in 1881, it was a groundbreaking addition to the Ottoman city center. One of Thessaloniki’s first multipurpose commercial complexes, it combined shops, offices, and workshops, and even included a han, an early form of inn where merchants and tradesmen could stay overnight. It was fittingly named Cité Saul, and its passageways pulsed with the same energy that animated the commercial heart of the city. The great fire of 1917 severely damaged the building, which once occupied an entire city block, but a portion of the original facade survives along Vasileos Irakleiou Street, where visitors can still see exquisite neo-Renaissance architectural details: elegant Corinthian capitals, ornate balconies with fine balustrades, and a heraldic emblem bearing the intertwined initials “S” and “M,” the monogram of Saul Modiano.

THE IMMACULATE CONCEPTION CATHEDRAL

1900

19 Fragkon

THE LEVANTINES OF THESSALONIKI formed a distinctive community within the city’s old multicultural mosaic. Though relatively few, they played a significant role in the commercial, social, and cultural life of the great Balkan metropolis. Locally, they were referred to as Franks, a term broadly used to describe Western Europeans and, by extension, Roman Catholics. Among them were merchants, consuls, bankers, missionaries, doctors, and even a few adventurers.

Despite being subjects of various European states, they were united by their shared Catholic faith. The presence of an imposing church to serve their spiritual needs was essential to the prestige and cohesion of their community. In 1896, the renowned architect Vitaliano Poselli was commissioned to design Thessaloniki’s Catholic Cathedral. On the site of a smaller earlier chapel, Poselli built a grand basilica dedicated to the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary.

According to local lore, when the final tile was placed on the roof, the Italian architect knelt in prayer and made the sign of the cross, thanking God that no worker had been injured or killed during construction. Even today, the three-aisled basilica on Fragkon Street impresses visitors with its exceptional acoustics and towering 40-meter-high bell tower. The flags of the Vatican fluttering in the courtyard welcome worshippers from around the world, while the same premises also house the offices of Thessaloniki’s Catholic community.

MALAKOPI ARCADE

1907

7 Syngrou

ON HISTORIC Stock Exchange Square – today a lively hub of with bars, restaurants, shops and constant foot traffic – one building continues to command attention. Known today as the Malakopi Arcade, it was originally constructed in 1907 to house the headquarters of the Banque de Salonique, a powerful financial institution owned by the influential Allatini family.

The Allatinis, from Livorno, were in a sense the rivals of the Modiano family. Their industrial and social reach was vast; by 1900, their flour mills employed more than two hundred workers, and their grand villa in Thessaloniki famously hosted Sultan Abdul Hamid II, who lived there in exile for three years after being deposed by the Young Turks.

At the dawn of the 20th century, the Allatinis commissioned celebrated architect Vitaliano Poselli to design a new building that would house their bank. The result was a two-story rectangular structure with a Baroque-style curved pediment, organized around a central square atrium covered by a glass roof that allowed natural light to flood into the interior. Remarkably, the original vault of the Banque de Salonique still survives in the basement of what is now a commercial arcade.

On the building’s façade, an ornate circular clock indicates 11:07. It was at that moment on the night of June 20, 1978, when a powerful 6.5-magnitude earthquake shook Thessaloniki. The stopped clock stands today as a silent, melancholy memorial to that night.

THE BOSPORION MANSION

8 Aristotelous

IN 1917, THESSALONIKI reached its all-time peak in population. To its residents were added hundreds of thousands of soldiers from the Entente forces, stationed in the region to fight – and perhaps die – on the Macedonian Front. Amid the turmoil of WWI, the city was struck by a devastating fire. Paradoxically, the blaze was not caused by a munitions explosion, bombardment, or other act of war, but – according to legend – by the carelessness of two Greek women frying eggplants, who inadvertently set much of the city ablaze.

The government of Eleftherios Venizelos reacted swiftly, appointing a committee of experts to redesign the burnt city. At its head was the French architect, urban planner and archaeologist Ernest Hebrard, who drafted an ambitious reconstruction plan. Though never fully realized, his plan gave Thessaloniki its most beautiful public space: Aristotelous Square. The square is distinguished by its unified architectural vision, as all buildings were required to conform to Hébrard’s design principles.

Among them stands the Bosporion Mansion, at number 8 Aristotelous. This twin four-story building was constructed as a residential property along the city’s new central axis. It’s notable for its Neo-Byzantine features, particularly the six biforate (or twin-arched) openings on the top floor that form elegant balconies. Another distinctive feature is its magnificent Art Nouveau entrance on the ground floor, one of the very few surviving examples in Thessaloniki. The Bosporion Mansion remains a vibrant fragment of the city’s past and one of the enduring jewels of Aristotelous Square.

THE ERGAS MANSION

1925

19 Dionysiou Solomou & 41 Eleftheriou Venizelou

IT WOULD FIT in as easily in Paris or Vienna, yet the Ergas Mansion stands in the heart of Thessaloniki, drawing the gaze of even of the most indifferent passerby. Built in 1925 in the fire-ravaged zone of the city near the Ottoman Bezesteni and the Venizelou metro station, this six-story building was designed by two prominent interwar architects, S. Mylonas and E. Kotzambassoulis.

The construction of such grand edifices became common in Thessaloniki during the 1920s and 1930s, reflecting a broader urban trend to combine ground-floor retail spaces with offices on the lower levels and luxury apartments above. What sets the Ergas Mansion apart is its curved corner, crowned by an impressive dome punctuated with elegant circular skylights. The dome resembles a vast observatory overlooking the bustling streets and shops below, while the building’s eclectic decorative features lend it both grace and harmony.

The mansion was commissioned by the affluent Sephardic Jewish family of Alberto and Allegra Ergas. On the upper floor, within an oval medallion framed by ornate plaster garlands, one can still read the family’s name. Another subtle tribute survives at the main entrance on Dionysiou Solomou Street: the intertwined letters A and E – the initials of the original owners – can be seen on the wroughtiron door, silent relics of a cosmopolitan world long vanished.

9

THE MASONIC MANSION 1932

44 Filikis Etaireias

FOR MANY, FREEMASONRY is shrouded in mystery; for others, it represents a romantic remnant of the past. Whatever one’s view, it is a fact that Thessaloniki during the Belle Epoque was home to several Masonic lodges whose members included many prominent figures of local society. Today, the city’s impressive Masonic Mansion, constructed in 1932 by architects G. Manousos and S. Mylonas, still stands proudly on Filikis Etaireias Street.

The structure displays bold Art Deco influences and features various inventive elements, such as the vertical openings that frame its skylights, allowing abundant natural light to flood the interior. Few know that the entire Makedonikon Cinema, with its later modernist façade, was one of the mansion’s grand halls before being rented out as a movie theater.

Inside, a powerful sculpture by an unknown artist depicts the three stages of Masonic initiation through three male figures: the young Apprentice, the mature Fellow, and the elderly Master. The high-ceilinged halls, embossed symbols, carved wooden doors and ceremonial chamber all reflect the dignity and prestige of the lodge.

During the Nazi occupation, the building was requisitioned and the invaders destroyed or looted much of its prized library and other valuable treasures. Despite these losses, the Masonic Mansion endures as a living monument of Thessaloniki’s history and architecture, and a reminder of the city’s lesser known mysteries.

10

THE YMCA MANSION 1934

1 Nikolaou Germanou

IN 1924, THE FOUNDATION stone for one of Thessaloniki’s most iconic buildings was laid. Ten years later, the YMCA Mansion opened its doors to welcome hundreds of young men and women eager to engage in athletic and intellectual pursuits. Designed by architect Marinos Delladetsimas, the building consists of two three-story wings connected by an open circular balcony, crowned by an impressive dome that dominates the skyline and draws the eye. The influence of Ernest Hebrard’s vision for Aristotelous Square is unmistakable, and the Neo-Byzantine touches bring to mind the city’s rich medieval heritage.

Thessaloniki’s long and proud basketball tradition owes much to the YMCA, whose members first introduced the sport to the city. Within this very building was Thessaloniki’s first indoor basketball court, and even today it houses the only heated swimming pool in the city center. Generations of Thessalonians have trained in its pioneering facilities, gaining not only physical strength but also the values of fair play and discipline.

Today, the YMCA Mansion remains a vibrant institution: it hosts a wide range of athletic programs, maintains an excellent library and serves as a venue for exhibitions, concerts and other cultural events. Still open to all, it continues to inspire, true to its long legacy.

THE OTE TOWER

1970

154 Egnatia

THE THESSALONIKI International Fair (TIF) was launched in 1926 with the mission of ushering in a “new era,” showcasing modern technologies and scientific innovations, and creating opportunities for commercial exchange between Greek and international entrepreneurs. After the Second World War, the need for technological modernization became even greater, leading to the construction of new modernist pavilions and buildings within the fairgrounds. The most emblematic of these – and still a defining feature of Thessaloniki’s skyline – is the OTE Tower.

Construction began in 1966 and was completed in 1970. Designed by architect Alexandros Anastasiadis, the tower was a bold experiment in the use of reinforced concrete, resulting in a fusion of function and futuristic design. It was named after the Hellenic Telecommunications Organization (OTE), to which it was leased.

Visitors can ascend its 166 steps or take the elevator to reach the tower’s restaurant and bar, which offer spectacular views over the city and the sea. The restaurant floor slowly rotates, completing a full 360° turn every hour and providing an ever-changing panoramic vista of Thessaloniki.

The OTE Tower also played a pioneering role in the history of Greek broadcasting; some of the very first Greek television programs were transmitted from here, introducing Thessaloniki’s residents tο the “small screen” in the early 1970s. Today, it remains both a technological landmark and a beloved symbol of the city’s modern identity.

THE LADIES OF AIGAI

Behind every great Macedonian king ...

BY JOHN LEONARD

The mysterious pre-Temenid "queens" of Aigai reveal that wealth and power were already a fact of life in what would become the heartland of Philip II's Macedonia.

IIF YOU HAVEN’T been to the new museum at Aigai (modern Vergina) yet, you should put it immediately on your list of must-see Greek historical destinations. Northern Greece, and particularly the Veria area southwest of Thessaloniki that represents the heartland of ancient Macedonia, is a treasure trove of archaeological sites, lush landscapes and fascinating history, featuring most prominently the Temenid (or Argead) royal dynasty and its unforgettable kings Philip II and his son Alexander the Great. But what of the ladies or queens of ancient Macedonia?

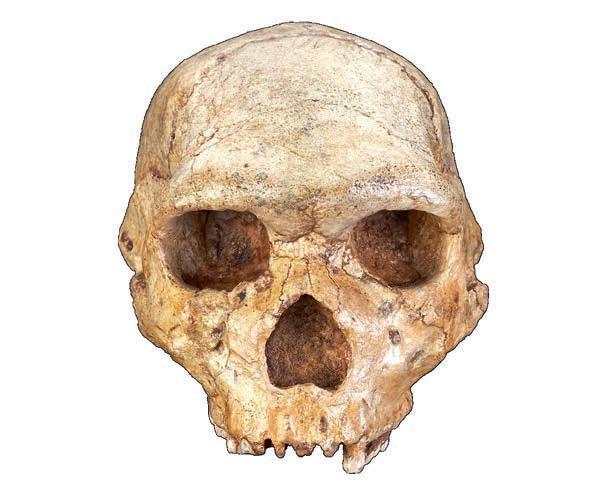

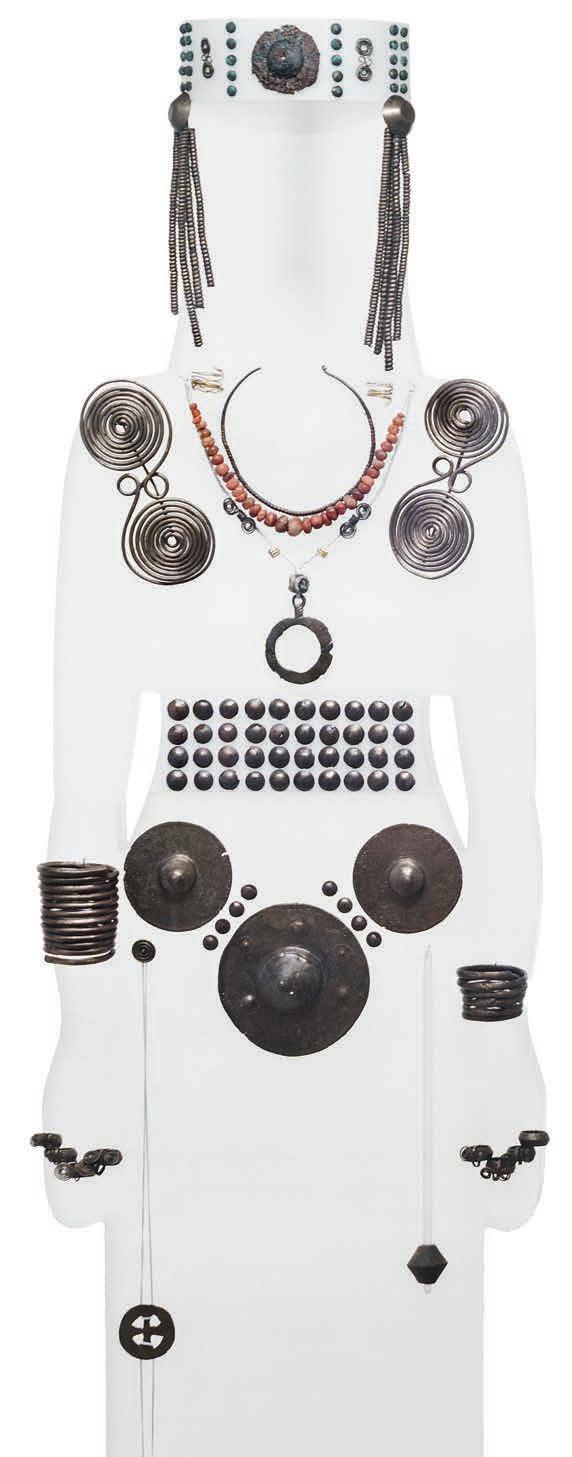

One of the most intriguing, perhaps little-considered historical revelations highlighted by the new Polycentric Museum is the presence at Aigai of clearly high-status women richly adorned with once-gleaming bronze jewelry who are presented as “Queens of Macedonia” – and who date from the early Iron Age (10th through 8th centuries BC) – an era beginning hundreds of years before the appearance of the Macedonian Temenids (about 700 BC). The exact identity or role of these ladies remains a mystery, but what they can tell us is that the splendid metals-rich culture we identify with Philip II and his empire was already a characteristic of this northern Greek region long before Philip was even a twinkle in his mother Eurydice’s eye.

Who were the ancient Macedonians?

In the 5th century BC, Herodotus and Thucydides wrote that the

inhabitants of Macedonia were descendants of Temenus, the legendary king of Argos. Their primogenitor in northern Greece was Perdiccas I, who left Argos about 700 BC, eventually establishing himself and his people “near the Gardens of Midas … in the shadow of the mountain called Vermio” – not far from the confluence of the Aliakmon and Lydias (now Loudias) rivers and present-day Veria. These were the “Macedonians,” whose name – likely deriving from “makros” in ancient Greek – meant “the highlanders” or “the tall ones.” They were hard-living mountain folk, mainly shepherds and farmers, whose elite leaders apparently based themselves at an already long-inhabited spot near a major crossroads known as Aigai, or The Place of the Goats (or Many Flocks).

Thanks to the archaeologists who have explored Aigai, led most notably in recent decades by now-retired ephor Angeliki Kottaridi, recognized today as one of the great “ladies of Aigai,” a vast necropolis of roughly 200 hectares dotted with hundreds of distinctive burial tumuli has been investigated and found to contain thousands of graves. Its southern, eastern and west/ northwestern areas include Archaic and Classical tombs (6th-4th centuries BC), but at its core lies an even older

cemetery dating to the early Iron Age. It is from here that the Aigai museum’s magnificently attired “queens” have once again come into the light.

Metals, mercantilism and telltale bling

...A VAST NECROPOLIS... DOTTED WITH HUNDREDS OF DISTINCTIVE BURIAL TUMULI... AND THOUSANDS OF GRAVES. AT ITS CORE LIES AN... OLDER CEMETERY DATING TO THE EARLY IRON AGE.

From an ancient Athenian perspective, the North was a wild, largely uncivilized region ruled by an ambitious, imperially minded king, Philip II, who posed a threat to his southern neighbors. Nevertheless, this area of ancient Greece, especially eastern Macedonia and Thrace, was also known to be rich in metals – iron, copper for bronze, silver and gold – as well as timber for shipbuilding. Consequently, it became a target for colonization, as shown by Athenian efforts to establish themselves near Amphipolis in the 470s and 460s BC, and more permanently in 437 BC. Long before this Athenian push, however, the Euboeans in the 8th century BC had already installed numerous colonies, emporia and commercial ports in the northern Aegean and Thermaic Gulf region, attracted in great part by the lure of profitable trade in metals, wood and wine. The early exploitation of northern Greece by southern outsiders attests to its resources. The pre-Classical graves of the Aigai ladies confirm an obvious truth: this natural bounty had already existed and was being exploited in the early Iron Age.

Burgeoning Prosperity

The magnificent array of gold, silver and other luxury grave goods in Tomb II within the Great Tumulus at Aigai, purported to be the royal burial of Philip II, showcases the high level of material wealth that characterized the ancient Macedonian elite. This historic moment in the 330s BC, just before Philip was assassinated (336) and Alexander took up the imperial reins, was an apex of traditional Macedonian civilization, before the new young king changed that

world radically, expanding Macedonianborne Hellenism into far-off Asian lands.

By the time of Philip II and Alexander III, the belief that the Macedonians were originally settlers from Argos, and thus descendants of not only royal Temenus but also the mythical hero Heracles, had become tradition. In fact, it seems they were Dorian Greeks, initially northern migrants who’d spread throughout mainland Greece and had already long resided in what later became the Macedonian heartland. Their rich and diverse culture in northern Greece remained little changed over the centuries – as indicated archaeologically – from the Late Bronze Age into the early Iron Age. The Macedonians’ traditionally-held Argive origin story may well reflect a real-life Dorian “return” to the north, as evidenced by the colonization efforts of Evia, or of Corinth at Potidaea (ca. 600 BC) in Halkidiki.

Eventually, change did come to Macedonia, with the rise of the Argead dynasty, especially under Philip II, as Alexander famously reminded his rebellious troops while campaigning in Asia: “He found you wandering about without resources, many of you clothed in sheepskins and pasturing small flocks in the mountains, defending them with difficulty against the Illyrians, Triballians and neighboring Thracians. He gave you cloaks to wear instead of sheepskins, brought you down from the mountains to the plains, and made you a match in war for the neighboring barbarians, owing your safety to your own bravery and no longer to reliance on your mountain strongholds. He made you city dwellers and civilized you with good laws and customs” (Arrian, Anabasis). Philip undeniably brought changes, with military innovations – such as the lengthy sarissa spear – and greater military effectiveness, his conquest of Thrace and other outlying neighboring regions, and his consequent bestowal of greater prosperity upon his people, but clearly wealth and power were already a characteristic of the “pre-Macedonian” Iron Age elite.

Macedonia’s great ladies

The early Iron Age ladies of Aigai were important, well-respected figures. Their personal attire and funerary accoutrements were strikingly lavish, especially compared with those of men, who were usually buried with only an occasional bronze ring or other small ornament and their iron weapons (sword, spearhead, arrowheads, or knife). Adorning the women’s heads were dangling triple-spiral bronze pendants and small golden spirals for the ends of the hair. Some wore cloth or leather diadems (now gone) with bronze buttons or other ornamentation. These noble ladies also wore carnelian bead necklaces, as well as bronze pendants, eight- or bow-shaped brooches, spiral bracelets, and rings. Their belts featured buckles, bosses and buttons. Beside them were placed tall wooden staffs capped with three double-axe heads.

Aigai’s extensive funerary evidence illuminates a complex, clan social structure necessary for effecting and controlling the exploitation and distribution of Iron Age Macedonia’s rich natural resources. The elite males were warrior kings and the females ornately clad, power-projecting queens.

Kottaridi suggests the ladies, with their double-axe staffs and other ritualistic objects, also served as priestesses.

Continuity in roles

During the ensuing Archaic and Classical eras, the Temenid ladies carried on these roles, as we see from the bronze “phialai” (libation bowls) ubiquitously placed in high-status female graves, and from the embossed silver phiale of the so-called “Lady of Aigai” – identified as the wife of King Amyntas I (ruled 512-497 BC), who received a magnificent burial about 495 BC. Her grave goods of gold, silver, bronze and ivory included a gilt-edged veil, pins, jewelry, scepter, distaff, spindle and golden-soled slippers.

Eurydice and Olympias

BY THE TIME OF PHILIP II AND ALEXANDER III, THE BELIEF THAT THE MACEDONIANS WERE ORIGINALLY FROM ARGOS, AND ... DESCENDANTS OF THE MYTHICAL HERO HERACLES, HAD BECOME TRADITION.

Two of the greatest ladies of Aigai were Eurydice I, wife of Amyntas III and mother of Philip II, and Olympias, Philip’s fourth wife and mother of Alexander. Royal succession was a crucial concern for Macedonian queens, and Eurydice, at no little personal danger and through extraordinary manipulation that even included recruiting an Athenian general supportive of her efforts, managed to ensure that her son Philip avoided murderous usurpers and became king (359 BC). Without her strength, Kottaridi reminds us, and that later of Olympias, who likely also worked behind the scenes to support Alexander, Macedonian history and Greece’s cultural impact on the ancient known world would certainly have turned out differently. Although little trace of Olympias has yet been found at Aigai, the Temenid necropolis excavations have revealed an elaborately decorated tomb with a monumental throne, discovered by Manolis Andronikos (1987), which has been attributed to Eurydice. Today, Queen Eurydice can be seen standing commandingly in one of the Aigai Museum’s courtyards, her sculpted image a votive offering to the goddess Eukleia made by the queen herself.•

Macedonia

Theme

Queen Eurydice I of Macedonia, whose courage and determination ultimately helped pave the way towards the Hellenistic world.

ECHOES OF BLOOD

From the fall of a monarch to the silencing of a voice for peace, the city has witnessed murders that changed the course of Greek history.

BY TASOS PAPADOPOULOS ILLUSTRATIONS: DIMITRIS TSOUMPLEKAS

Thessaloniki is famous for iconic landmarks such as the Rotunda, the Church of Aghios Dimitrios, and its sweeping seafront. It is equally beloved for its rich gastronomy, a blend of cultures and flavors that mirrors its long, layered history. Yet, beneath this luminous image lies another story – one written in blood. From the bullet that ended the life of King George I and the iron bar that struck down Grigoris Lambrakis to a certain bound body found floating in the Thermaic Gulf, Thessaloniki has often served as the stage for acts of political violence. These assassinations became turning points in the nation’s history, casting long shadows and creating legends – some still unresolved. We trace their echoes through the heart of a city that remembers more than it reveals.

ON OCTOBER 26, 1912, the feast day of Thessaloniki’s patron saint, Aghios Dimitrios, the Greek army marched triumphantly into the city. After nearly five centuries of Ottoman rule, Thessaloniki was finally part of the Greek state. A few days later, King George I arrived and took up residence, his presence a clear signal to the Great Powers – and to rival Balkan states – that the city was now irrevocably Greek.

Born in Denmark and a member of the House of Glücksburg, George had reigned since 1863 and was known as a prudent, steady monarch. Married to the Russian princess Olga, he had guided Greece through turbulent times. His stay in Thessaloniki was a momentous event: crowds gathered daily outside his villa in the Exoches district, hoping to catch a glimpse of the monarch.

Thessaloniki in 1912 was a very different place – a true mosaic of cultures and communities. The majority were Sephardic Jews, alongside Turkish Muslims, Greek Orthodox, and smaller groups of Slavs and Armenians.

On March 5 (18), 1913, after a formal visit to a German warship, the King set out on foot back to his residence. Security was strikingly lax for a city still unsettled by war. His only companion was his loyal aide-de-camp, Major Fragoudis, reportedly hard of hearing and leaning toward the King to catch his words rather than scanning their surroundings.

As they walked, they passed a man who looked like a beggar sitting on the curb. As the pair continued on, the stranger stood, drew a pistol from his coat, and shot the King in the back. Pandemonium followed. George collapsed instantly, and the gunman was seized moments later. To everyone’s shock, he was not a foreign agent but a Greek: Alexandros Schinas.

News of the assassination spread quickly, plunging the country into mourning and alarming diplomats across Europe. Schinas refused to speak to anyone except Queen Olga, the King’s widow, and died soon after – officially by leaping from a police-station window, though many believed he was thrown. His motives remain obscure.

The assassination of King George I marked the end of an era and the beginning of years of upheaval. Within months, Greece would be drawn into the First World War, and the path toward the Asia Minor Campaign and the national disaster that followed had already begun.

THE ASSASSINATION OF KING GEORGE I, 1913

THE 1940S WERE A DECADE of devastation for Greece. After repelling an Italian invasion in October 1940, the country fell under Nazi occupation from April 1941 until October 1944. And while the world celebrated the end of the Second World War, Greece descended into a bloody civil conflict between the National Army and the Democratic Army, the latter organized by the Greek Communist Party (KKE).

The Greek Civil War quickly drew international attention, widely viewed as the first battlefield of the emerging Cold War. Among the foreign correspondents who arrived in Greece was George Polk, a reporter for CBS News in New York. Born in Fort Worth, Texas, in 1913, Polk came from a once-wealthy family that lost its fortune after the 1929 crash, preventing him from completing the higher education he desired. Restless and adventurous, he traveled across the United States and beyond – to Alaska, the Philippines, China and Europe – before serving in the Pacific during World War II, where he was wounded in combat.