The Great Dixter Journal 2024

Great Dixter was a superb sight, dressed overall for the Christmas Fair at the end of November last year. Perhaps, as the snowdrops are already in flower, you may think it perverse of me to turn the clock back to that event. But I wanted to say a loud thank you to the team who made it all happen and filled the garden buildings as well as the house with such a rich mixture of artists and makers. And it was an inspired idea to bring sheep onto the grass alongside the path to the porch, exactly the kind of unexpected vision that makes any visit to Dixter so memorable. Actually what I saw was the hurdles of their pen, as the sheep had been temporarily removed having been spooked by a dog on the loose. Nevertheless, I loved the pastoral quality the scene added to the well-known approach.

On the occasion of the Christmas Fair, the Great Hall was filled with stalls, but curiously intimate still, with a fire blazing in the vast fireplace that dominates one end. Christopher held some terrific parties in the Great Hall. I remember a birthday feast followed by music, when Graham Gough gave us some of Franz Schubert’s Lieder accompanied by Pip Morrison at the piano. Graham was a professional singer before he became an inspired nurseryman, original owner of Marchants Hardy Plants.

Christopher loved German lieder and they played a big part in the programme he had devised for his birthday. He stood in the centre of the Great Hall, surrounded by friends, and introduced each piece with wonderfully confident panache. He might have been a presenter on Radio 3, a kind of Donald Macleod Composer of the Week figure, who happened to do a bit of gardening on the side. He was magnificent. ■

by Anna Pavord, Patron

CONTENTS

6. Sir Edwin Lutyens and Great Dixter Charles Hind

10. Young Daisy Roy Brigden

21. Trees:

22. Spring trees Daniel Carlson

26. Autumn Jamie Todd

30. Propagation of trees from seed Samuel Walker

34. Conifers Ros Crowhurst

38. Visitors from America 1928-1939 Roy Brigden

46. Study in two world-class gardens Annie Guilfoyle

50. A place of opportunity Tom Stuart-Smith

52. Great Dixter inside and out Karen Edwards

54. An entomologist at Great Dixter Chris Bentley

58. 5 things I had to unlearn Michael Wachter

60. The Fergus 4 Fergus Garrett

66. Great Dixter scholars 2023-2024

83. Work experience Hannah Moore

84. Donor pages

Door to the sales shed in the nursery

Photograph taken in the top carpark of the people working onsite at Great Dixter on Tuesday 13th February 2024 at 1.30pm. Back row: Zu Harrison, Lauren Ware, Michael Morphy, Sarah Seymour, Nigel Ford, Bill Ludgrove, Peter Chowney, Shaun Blower, Jamie Todd, Ros Crowhurst. Middle row: Samuel Walker, Hetty Fruer Denham, Ben Jones, Luke Bennett, Mikey McGuinness, Linda Jones, Alice Rodriguez, Carol Joughin, Jodie Jones.

Front row: Naciim Benkreira, Ernie Weller, Luke Senior, Talitha Slabbert.

Photograph taken in the top carpark of the people working onsite at Great Dixter on Tuesday 13th February 2024 at 1.30pm. Back row: Zu Harrison, Lauren Ware, Michael Morphy, Sarah Seymour, Nigel Ford, Bill Ludgrove, Peter Chowney, Shaun Blower, Jamie Todd, Ros Crowhurst. Middle row: Samuel Walker, Hetty Fruer Denham, Ben Jones, Luke Bennett, Mikey McGuinness, Linda Jones, Alice Rodriguez, Carol Joughin, Jodie Jones.

Front row: Naciim Benkreira, Ernie Weller, Luke Senior, Talitha Slabbert.

SIR EDWIN LUTYENS AND GREAT DIXTERTHE LAST OF HIS ‘VERNACULAR’ COUNTRY HOUSES

by Charles HindChief Curator at the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), which holds the Edwin Lutyens’ archive of drawings, letters and models. Charles was appointed by Christopher Lloyd as a Trustee at the start of the Great Dixter Charitable Trust.

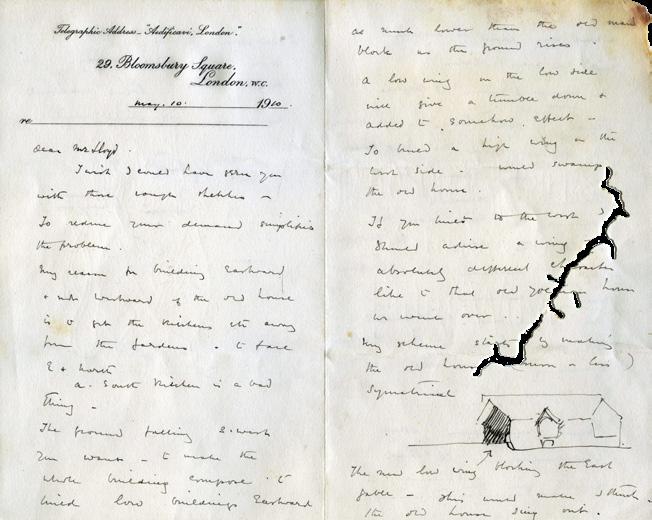

EDWIN LUTYENS paid his first visit to Dixter on 10th May 1910. There is no record of how exactly Nathaniel Lloyd had approached him to look at the farmhouse that he and his wife Daisy had purchased earlier that year. But Nathaniel would certainly have known of Lutyens’s work from Country Life, whose owner, Edward Hudson, had been actively promoting him since the launch of the magazine in 1897 and to which Nathaniel had been a subscriber since the first issue. Furthermore, he must have known of Lutyens’s rebuilding of Great Maytham a few miles away at Rolvenden, just over the border into Kent, which was begun in 1909. Given Nathaniel’s well-known self-assurance demonstrated both in his business life and in his requests for access to old houses a few years later (resulting in his History of the English House, published in 1931), I am sure that he had driven over from Rye to inspect

the building site at Rolvenden and it was the same self-assurance that was behind his approach to a man who was already one of the leading architects in the country and who two years later was to start work on the planning of the new capital of Britain’s Indian Empire in Delhi.

Lloyd had hedged his bet in approaching Lutyens, for he also invited Sir Ernest George to submit proposals. George was a Royal Academician and had been designing country houses since the 1870s, so he was approaching the end of a distinguished career whilst Lutyens had not yet attained the peak of his. This time there was a known connection, for one of Lloyd’s friends and golfing partners was George’s son Allen. Allen George was thoroughly aggrieved at the rejection of his father’s proposals for Dixter (there are letters in the Dixter Archives) and his friendship with Nathaniel does not appear to have survived. Neither have Sir Ernest’s proposals but undoubtedly, he would have produced a thoroughly serviceable and comfortable house that would have had none of the understanding of old work and brilliant suggestions for new that distinguish a Lutyens building.

From 1900, Lutyens had been

LUTYENS HAD BEEN INCREASINGLY DRAWN TO CLASSICAL ARCHITECTURE AND DIXTER WAS THE LAST OF HIS VERNACULAR HOUSES

increasingly drawn to classical architecture and Dixter was the last of his vernacular houses. It was completed in 1912 and its porch provided the inspiration for the very last timbered structure that Lutyens built, at the Shakespeare’s England Exhibition at Earls Court, which ran from June to October that year, coinciding exactly with the Lloyds moving into their new house. But what was unique about Dixter was the involvement in the design process of the client, which Lutyens had never encountered before. In making his initial suggestions back in 1910, Lutyens had stated that he wanted ‘to make the old house sing out while making the whole building compose well’ and he suggested looking at local 15th and 16th century buildings for precedents. Nathaniel took this to heart and was soon bombarding Lutyens with sketches and photographs of houses and their details, many of which Lutyens took on board. Furthermore, Nathaniel loved the process of building his house, making a nuisance of himself to his clerk of works by visiting almost every day, but his enthusiasm turned a retired middle-aged printer into an architectural historian and what would today be described as a conservation architect. ■

YOUNG DAISY

by Roy Brigden, Great Dixter archivistDAISY LLOYD (1881-1972)

is a key figure in the twentieth century story of Great Dixter. We know her of course as the wife of Nathaniel and mother of six children, of whom Christopher was the youngest. But there is so much more, because in her own right Daisy was a woman of extraordinary talents and personality that even now permeate the house and gardens. This first section looks at the earlier, pre-Dixter, phase of the young Daisy’s life, through to her marriage in 1905, and relies entirely on material from the Great Dixter archive.

Daisy Field and her sister Myrtle, younger by a year, had a comfortable and happy middle class upbringing. Her father Basil was a respected solicitor who was also engaged in the London literary and arts scene. He dabbled in writing and his brother Walter Field was an artist so there was clearly an artistic streak running through the family. Perhaps also there was a touch of the unconventional about them. The first family photographs of toddlers Daisy and Myrtle, for example, are dated Southsea June 7 1884, a clear six months before their parents were officially married in Bournemouth in January 1885.

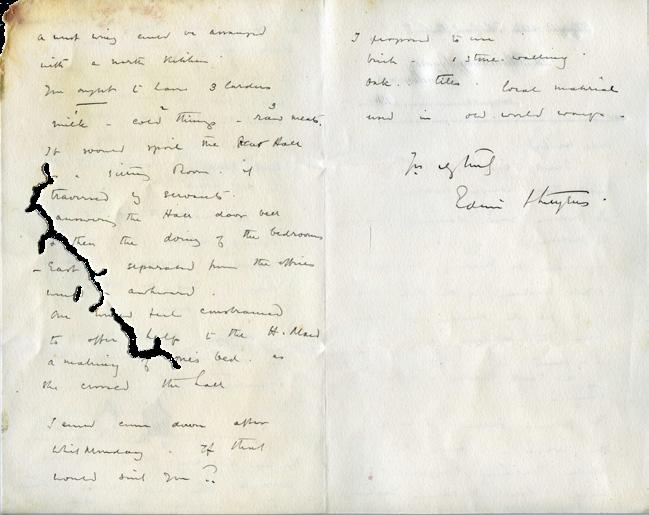

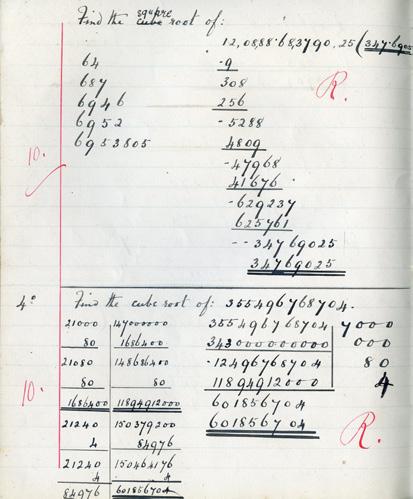

If those earliest years are a little hazy, Daisy’s later childhood was spent in a large Victorian town house, ‘Basildene’, at 14 Cambalt Road, Putney. It does not appear that either she or Myrtle went to school as such but rather were taught at home by a tutor. Some of Daisy’s exercise and examination books survive

Daisy (left) and Myrtle, June 1884

Daisy (left) and Myrtle, June 1884

running through from 1892 to 1898. They include composition and dictation in French, English and German; complex exercises in arithmetic and algebra; and detailed instruction in botany. All demonstrate an early emergence of the exquisite handwriting, and the acute attention to spelling and grammar, that were lifelong characteristics. Needlework and other artistic and craft activity were also firmly planted in the domestic household.

AN EARLY EMERGENCE OF THE EXQUISITE HANDWRITING, AND THE ACUTE ATTENTION TO SPELLING AND GRAMMAR, THAT WERE LIFELONG CHARACTERISTICS.

Countryside pursuits were nurtured in holiday times at the Mill House in Ramsbury, Wiltshire, which Basil leased for the shooting and fishing on the River Kennet that he so enjoyed. A diary entry for 24th August 1893 records the first mention by the 11 year old Daisy of Mr Lloyd who had come down to shoot moorhen with Basil. Nathaniel Lloyd, a successful London businessman of 26, was a client of Basil Field’s law firm and they bonded over their shared enthusiasm for shooting and fly fishing. There is a photographic portrait of Daisy taken the following year, 1894.

In 1901, Mrs Amy Field and her two daughters took a trip to America. They sailed from London to New York on the S.S. Minnehaha in April and returned at the end of August, the voyage taking a week each way. The itinerary was arranged around a scattering of Amy’s relatives and friends over there. Daisy kept a stack of mementos from the tour: menu cards, for example, concert programmes and annotated passenger lists from life on board ship; some water damaged souvenirs from a close-up view of the Niagara Falls; postcards from Ottawa and Quebec. On July 31st, she writes from Belleville, Ontario, whilst doing some carriage driving on business with Mr Baker, a friend of Amy’s cousin: ‘We expect to get home by about 8 o’clock just fancy! I shall have driven 46 miles altogether! Isn’t that just dandy! I can manage ‘Lady’ perfectly, and am really learning to be quite cute about picking out the best pieces of road’. There is also material from a stay in the city of Sedalia, Missouri, over 1,000 miles west of New York. In one of the drawers in the Yeomans Hall at Great Dixter is a fan carefully labelled in Daisy’s own hand: ‘Another youthful fan. I was carrying it when

Daisy’s mother Amy at the Field family home in Putney, c.1890

Comparing the ox-eyed daisy and the cornflower in Daisy’s botany exercise book, 1895

A maths exam, 1896

The tiro’s (beginner’s) guide to gowf’. The non-sporty Rudolph’s tongue in cheek summary of the game which had become a passion for Nathaniel by the early 1900s

I learned to dance “The Washington Post” in Sedalia, Mo., in 1901’. There was an important German dimension to Daisy’s younger life that stayed with her and was passed seamlessly on to her children. A few doors down at No.20 Cambalt Rd, Putney, lived the family of Lewis and Klara Tomalin and their four children. They had re-located to London from Frankfurt. Tomalin was a prosperous businessman and had set up Jaeger (then a health conscious woollen clothing company rather than the fashion brand it later became) with his brother in law Heinrich Ihlee, also from Frankfurt and also now in London with his family. The Fields and the Tomalins were close friends, and as teenagers Daisy and her sister would often spend holidays with what became their extended German family back in Frankfurt. Here they became fluent in the language and mixed with other members of the cultural and industrial elite of the city – like Paul and Olga Hirsch, for example, whose marriage Daisy attended and whose daughter Renate would many years later have a son, Michael Schuster, godson to Christopher Lloyd.

When Lewis Tomalin’s business partner, Heinrich Ihlee, died in 1891 at the young age of 47, some of his nine children returned to Germany with their mother while the older ones stayed behind in England. One of these was Rudolph Ihlee (1883-1968) who was taken under the wing of his aunt Klara Tomalin in Putney. He formed part of the circle in which Daisy moved and they became great friends. His first appearance in the archive is in the form of an exquisite pen and ink sketch of Frankfurt which he drew in Daisy’s commonplace book and is dated 1899. At the turn of the new century, they spent a lot of time together and when they were apart they wrote to each other. There are 42 letters and cards from Ihlee to Daisy, covering the period 1900 to 1920, which she carefully kept together amongst her personal records in a marked envelope. From 1902, Ihlee spent periods away in Manchester and Scotland as a trainee draughtsman with electrical engineers Ferranti Ltd, before changing tack and registering at the Slade in London in 1906 to prepare for his chosen career as an artist. In that same envelope of letters, is an Ihlee drawing for an electric car. Daisy’s books at Great Dixter from this era of her life still have the Ex Libris bookplate, featuring his take on the legendary

RUDOLPH WAS NO FAN OF NATHANIEL AND HIS PROBLEM WAS THAT AS A TEENAGER, FREQUENTLY AWAY FROM LONDON, AND WITH UNCLEAR PROSPECTS AHEAD OF HIM, HE DIDN’T HAVE MUCH WITH WHICH TO FEND OFF A MORE ESTABLISHED RIVAL.

trochilus or crocodile bird, that he designed for her in 1904. Daisy wrote at least as many letters to Rudolph as he to her, but all that survives is his side of the correspondence. He was two years younger so to begin with it’s as if he were writing to an older sister, and mockingly addresses her as ‘Dear old Daisy’. That rapidly transitions into something rather deeper with frequent expressions of affection and innocent young love, clearly reciprocated. As early as February 1902, having just received a framed photograph of Daisy to brighten up his gloomy Manchester digs, he is aware from her letter that Nathaniel Lloyd is becoming a more frequent visitor to Putney. In his long reply he tries, with as much subtlety as he can muster, to tell her not to encourage him unless she is serious. Rudolph was no fan of Nathaniel and his problem was that as a teenager, frequently away from London, and with unclear prospects ahead of him, he didn’t have much with which to fend off a more established rival. The letters continued, still with fondness but with rather more reserve and distance than before. When at last he received from Daisy the announcement of her engagement in April 1905, Rudolph replied from Falkirk with good wishes that were almost buried under expressions of angst and black humour. More letters followed through the years leading up to the First World War, when Rudolph was struggling to break through as an artist and battling his own mental problems (‘Tan’s away. Come and see me!’ wrote Daisy in June 1911). They resumed after the War when the fallout from his own disastrous marriage had added further to his anguish. He came to stay at Great Dixter in May 1919 and was much taken with everything, particularly the then youngest child, Quentin, whom he dubbed ‘Mr Tippins’ or ‘Mr T’. His health was still of concern and the following year he asked Daisy if he could come and stay for a week to recuperate. During this time, after much searching, he purchased the ceramic white jack that still remains in the basket of carpet bowls in the Solar. Before long he would set off with his friend and fellow artist Edgar Hereford to make a new artistic life in the south of France. The last letter in the archive from

April 15th 1905, Daisy makes her decision

For the happy couple, a wedding message and present from the staff of Nathaniel Lloyd & Co.

Daisy

25, in November 1905, six months after her marriage

Rudolph to Daisy is dated October 1920, where he apologises to her for a late cancellation of another visit. He signs off with: ‘At present I am not only depressed but greatly depressing so think of what you have escaped & be cheerful. My dismallest regards to D.T (this was how he referred to Nathaniel) & just the least suspicion of a smile to my old friend Mr T. Yrs R.’

Nathaniel Lloyd succeeded in his wooing of the young Daisy but, as the extensive correspondence in the archive shows, it was a slow process and there were some bumps in the road. From the early 1890s, Daisy would write on his birthday, 4th March, in a tone of respect, as to an elder relative, addressing him as Mr Lloyd and passing on family news. He would respond in terms of muted affection. In 1897, Daisy starts referring to him as ‘The Holluschickie’, which means a bachelor seal, and in 1900 her now much chattier birthday letter opens with: My Dear Holluschickie, I wish you many happy returns of your birthday!

Papa says that when one reaches a certain age, it becomes unkind to remind one of this anniversary. Have you got there yet? If so you only have to tell me and I will cease being unkind!’

Moving on to March 1903, there is some turmoil in the air. Nathaniel had sent Daisy a book on bridge to which she replied briefly with a card. A longer, more edgy letter followed the next day, opening with: ‘Dear Mr Lloyd, I am feeling dreadfully tired & stupid tonight so you won’t get a very nice birthday letter this year, but my good wishes are none the less sincere. I wrote an awfully long one (6 pages) this morning, but then that was to a boy who doesn’t relish “brevity” as much now as he may do when he gets to your time of life!’ The six pages would have been a pouring out of her thoughts and feelings to Rudolph.

In April 1903, Nathaniel made his move and was rejected. The following day he wrote to her: ‘I must write to thank you for being so frank with me last night & to tell you how much I appreciate your kindness in letting me have a talk which was so painful to you.’ Daisy responded: ‘Yes it was a “painful” thing that I did the other evening – more painful I fancy, than even you can realise, for by nature I am really very tender-hearted & shrink from hurting anybody’s feelings - & much more those of an old & valued friend.’ In his reply, Nathaniel goes for broke and hopes she will reconsider: ‘My love for you, which was little

more than affectionate friendly regard three years ago, has grown & grown until it seems to have absorbed my whole being & you are almost always in my thoughts. To cut off the hope of winning you would be to cut off all the sunshine out of my life & make everything blackness.’

NATHANIEL SUCCEEDED IN HIS WOOING OF THE YOUNG DAISY BUT, AS THE EXTENSIVE CORRESPONDENCE IN THE ARCHIVE SHOWS, IT WAS A SLOW PROCESS AND THERE WERE SOME BUMPS IN THE ROAD.

Daisy’s parents, Basil and Amy, stepped in at this point and advised Nathaniel to stay away from Cambalt Road for the time being, as the situation was becoming stressful, and they would keep him informed of any developments. They declared themselves neutral but clearly Nathaniel was a friend of longstanding and in that Edwardian age represented a suitable match for their daughter. Amy was the main channel of communication and engaged in regular correspondence with Nathaniel to pass on news of Daisy. This brought them closer together and in July 1904, after more than a year of impasse, she wrote: ‘My Dear Tan……If I can ever do anything for you, I think you know how gladly I would do it. It grieved me more than you know when I thought our friendship was to end. I liked you first through your love for Daisy but now I love you for your own sake.’

Another year passed before Daisy herself suddenly broke the deadlock on April 15th 1905 with a card to Nathaniel that read simply: ‘Dear Friend, I find I can’t do without you after all, Your Daisy’. They were married a month later, 20th May 1905, in Wandsworth Unitarian Church (Daisy Field’s grandfather, Edwin Wilkins Field, having been a prominent Unitarian). It was a low key event from which there are no photographs, and little else that has survived. They opted not to live in Nathaniel’s London home but in Willersley, his golfing bolt-hole in Rye, from where Daisy wrote on June 26th: ‘Tan dear, I don’t know how to begin this, my first married letter to you….I think you’re the very dearest husband that woman was ever blessed with, and the truest friend too, & I thank God every hour of the day (& the night too when I wake up) that you belong to me.’ The first child, Selwyn, came along in 1908, and the search was on for a country home suitable for a growing family. The Great Dixter adventure was about to begin. ■

Trees

PLANTED AND CARED FOR OVER GENERATIONS, TREES KNIT THE GARDEN INTO THE WIDER LANDSCAPE. HERE, MEMBERS OF THE NURSERY TEAM, WITH THE HELP OF ARCHIVIST ROY BRIGDEN, EXPLORE THEIR ENDURING PRESENCE AT DIXTER

by Daniel Carlson, Nursery worker

by Daniel Carlson, Nursery worker

SPRING RUSHES INTO Dixter with a force. It can be hard to imagine more coming while we enjoy winter snowdrops and early crocus, but when spring really arrives, long and heavy, you can be knocked back by its beauty and intensity. While the Gardeners are still busy with final plantings and preparations for the main growing season to take over, the flowering bulbs are stars of the garden, but in the background, if you can step back and look up, are the spring trees of Dixter.

The lower meadow, down from the long border, is full to the brim with naturalized bulbs and wildflowers but it was originally planted as a prolific orchard. Some trees still remain and their blossom and falling petals fill the air. Towards the bottom, at a cross in the meadow paths, stands an incredibly tall wild pear tree. It is a seedling grown by Christo, the seed wild collected. The lowest branch of which has bent over the path and kisses the growing grasses. The arch created is a spectacle with people laughing their way through the portal.

Christo writes, “I am fond of pear blossom, for its sickly sweet scent; also for the distinct manner in which the flowers (which are always dead white) are borne in clusters.”

-Christopher Lloyd’s Gardening Year

At Dixter there is a pursuit to connect the garden to the wider landscape, the meadows connecting to the garden. There is an espaliered culinary pear trained on the chimney at the side of the house. The balance between this tree, so clearly showing the gardeners hand, and the wild, inedible, towering specimen is striking. Clearly Christo loved pears - edible or not. “In writing about pears, I am torn between the fruit and the tree. An old pear tree, whether or not it fruits, is venerable and achieves a great age, with thick stems and rough, scaly bark. It is easy to admire the trees without caring whether or not they fruit. They just are splendid to look at, especially, but not only, when in flower, and that is enough.”Christopher Lloyd, The Guardian

When asked about the espaliered tree ‘That must be terribly old,’ a lady visitor said to me. ‘Well,’ said I, ‘how old are you, for instance?’ ‘I was seventy last week.’ ‘That’s just about the pear’s age,’ I told her. ‘Not so very ancient, is it?’ - Christopher Lloyd’s Gardening Year

Continuing into the garden stands a gnarled pear, just hanging onto life, though clearly supporting others with its moss-laden branches and countless holes from birds and insects. “Yet another

old pear, a nineteenth-century survivor, is in the peacock garden, and that is a beautiful shape, especially noticeable when flowering.”

-Christopher Lloyd’s Gardening Year

In the garden the queen of spring is the tulip magnolia. There are a few specimens through the garden. Stepping up the circular steps you find the Magnolia x soulangeana ‘Lennei’ seemingly tumbling down from the upper terrace to the path below. “Some of the branches of mine trail on the paving below it. They are not much in the way, so I allow that and it gives the opportunity of looking down into the flower by way of a change from always looking upwards.”

This tree is now entwined with wisteria, the pale lilac racemes mixing with the “Large, electric light bulb shaped, deep mauve-pink on the outside, off-white within.” -Christopher Lloyd’s Gardening Year

Another cultivar is M. ‘Galaxy’ with an upright habit growing along the path from the high garden down to the long border. The tree is well seen from the east side of the house, the Day Nursery or even higher.

Nearby, to the side of the circular steps grows a subtle yet glorious small tree. Corylopsis glabrescens with hanging pale yellow flowers creating the perfect foil for a colony of pale blue Scilla bithinica. Christo would pick the branches for its matching lemony scent.

It would be impossible to write about spring at Dixter without mentioning the Malus hupehensis. These enormous crab apples dot the site, one in the orchard,

four in car park, their crowns connecting into one mass, and a new generation about head high, ensuring continued blossom into the future. In May the trees are covered in large white flowers opening from pink buds. The snow of falling blossoms match the cow parsley below.

“Malus hupehensis, the Chinese crab, is the best crab apple according to experienced tree people and another fine discovery of the great plant hunter, Ernest Wilson. Wilson had impeccable taste and the tree, which is quite substantial in maturity, is a spectacle in flower…It was one of Christopher Lloyd’s favourite trees and, naturally, he selected a superior form.” - Dan Pearson, Dig Delve We grow and sell this form in the nursery.

In the spring, with its bounty and rebirth, it can be hard to believe that trees don’t live forever. In researching for this, many trees we see images of or read about in Christo’s books and columns are now gone. Lost in the historical storms, or simply by outliving their years. One such specimen I wish I could have seen is the Malus floribunda, with its twisted trunk absolutely covered in flowers. Or the second Mulberry, planted as a twin, lost in the storm of 1987. But we don’t despair. Of course the loss of a tree can hurt, but it is always an opportunity for something else. More light falling through, a new vista opening, a sign of the passage of time, or simply the benefit of the ecological explosion of growth we see on the decaying branches. Moss, lichen and insects going to work to return all to the soil. Because of course dead wood is dead good. ■

Above, Malus hupehensis in the carpark.

Left, letter to Nathaniel Lloyd from a fruit tree supplier in 1918. Below, wild pear in the lower meadow.

Autumn

BY JAMIE TODD, NURSERY WORKERAs autumn creeps upon us slowly, the boundary between the abundance of summer and creeping senescence is often hard to gauge. Fruits slowly ripen in the last of the sun’s heat and the vibrant colours of the summer mute, becoming richer and deeper. Starlings arrive en masse in the Ash trees at the edge of the garden, making group flights to feast on the glassy red fruits of Malus hupehensis in the car park. With the transition of seasons, temperatures decrease, and daylight hours shorten. Trees receive less direct sunlight, leading to the breakdown of chlorophyll in their leaves, revealing pigments disguised in the summer months.

Starlingsperching on Fraxinus excelsior

There are three trees at Dixter whose fruits always catch your eye. Crataegeus pentagyna at the top of the kitchen drive has clusters of shiny jet-black berries. Crataegus elwangeriana, by the lower moat, is covered in tomato red pomes. Christo thought Crataegus orientalis the best. Sitting in the front meadow and often asked about, this tree was rated ‘not just for berries, either. I consider it the best small tree available. Its roundtopped crown is pleasing. Its grey leaves remain a pleasure through summer; then, in autumn, it carries crops of large, soft orange haws’.

elwangeriana

CrataegusGinkgobiloba

Taxodium distichum

Two deciduous conifers illustrate this transition perfectly. The Taxodium distichum, which sits mirrored in the Horse Pond, turns countless shades of oranges, reds and browns. The living fossil, Ginkgo biloba, protected within the tapestry plants in the Old Rose Garden is almost the last to turn, its scallop-shaped leaves becoming buttery yellow. A marked contrast to the glaucous foliage surrounding it.

Two trees formerly classified as Sorbus are particular favourites of mine. Cormus domestica (syn. Sorbus domestica var. pyrifera) I knew from my time working at Oxford Botanic Garden where two huge forms reside in the walled garden. Our tree, in the orchard meadow at Dixter has a huge canopy, which in autumn is covered in pome fruits resembling miniature pears which on falling, gradually carpet the ground.

Karpatiosorbus bristoliensis

Karpatiosorbus bristoliensis

(syn. Sorbus bristoliensis) is the only tree that resides within the nursery footprint. A British endemic, it is only found in the wild along the Avon Gorge. The tree is covered in lichen, giving the grey bark the appearance of verdigris, with tiny bright orange fruits reaching toward the sky. Eventually the chatter of the starlings subsides, leaves have fallen and fruit has dispersed. For our deciduous trees only structure remains and ever swelling buds holding the promise of spring. ■

PROPAGATION OF TREES FROM SEED

By Samuel Walker, Nursery Scholar

ARRIVING AT GREAT DIXTER on the cusp of autumn means that I have done a fair amount of tree propagation thus far. I have found propagating trees to be quite an adventure, scrambling to find fruits and berries, prising them open or fermenting them to reveal the seeds. You may marvel at trees, standing beneath them to revel in their natural beauty or you may just wander past. They offer such a multitude of interest: their differing leaf tones, structure, height, their individuality and their contribution to the greater landscape. The following is my recent experience of propagating by seed, although many trees will successfully grow from hardwood cuttings.

To propagate Morus nigra, the old mulberry by the Lutyens circular steps, I collected fruit from its laden limbs, the ground underneath was splattered deep purple with fallen mulberries. I placed the slightly squished berries in a jar of warm water and left it to ferment for a couple of weeks. I drained and rinsed the fruits before spreading the pulp onto a sheet of newspaper to dry, taking time to carefully separate the seed from the flesh. During my research, I found that a 100 day cold stratification would increase the germination rate from a mere 33% to a far more satisfactory 88%. The dried seed was then placed into a bag of damp sand

and put into the fridge set at 4oC. Come early January, the seed will be sown and placed on a heat bench to encourage germination.

I have also propagated Malus hupehensis and Karpatiosorbus bristoliensis (syn. Sorbus bristoliensis) using a similar fermentation method. The fermentation mimics an animal’s stomach, stripping the flesh from the seed. Although not necessary, I find placing your jar of fermenting fruit on a heat bench, at around 25oC, is a great way to speed up this process.

Propagating Cormus domestica (syn. Sorbus domestica) from seed was particularly interesting. I collected the pear-shaped fruits from the tree in the orchard. Looking for ripe, undamaged fruits either from the tree or from the hundreds that littered the ground. When it came to extracting the seeds, I used a YOU MAY MARVEL AT TREES, STANDING BENEATH THEM TO REVEL IN THEIR NATURAL BEAUTY OR YOU MAY WANDER PAST. THEY OFFER SUCH A MULTITUDE OF INTEREST: THEIR DIFFERING LEAF TONES, STRUCTURE, HEIGHT, INDIVIDUALITY AND THEIR CONTRIBUTION TO THE GREATER LANDSCAPE.

wooden mallet to break the hard fruits, careful not to damage the seed within. Each fruit produced only 1 seed, and extracting a sufficient amount took some time. To prevent the seed coat from hardening, I placed the cleaned seeds in water as I extracted them.

By the end, I had a pile of Sorbus fruit flesh and one small pot of seeds. I sowed these fresh into our seed mix, covered lightly with sieved soil and topped with a final layer of grit before labelling and placing outside. Exposing the seed to a winter period, acts as a natural cold stratification, which will aid their germination.

Crataegus orientalis is a prominent specimen at Dixter, one of the first trees you see as you enter the garden, towards the right hand side of the path. One afternoon, I went to collect the mottled orange-red fruits, not many of which remained on the tree. Extracting the seeds was simple enough: the fruits were soft and easily squished in the hand, then the several seeds picked out with ease.

I sowed half the seed in our regular way, a pot of seed compost, lightly tamped, seeds equidistantly sown, covered lightly with a sieved soil, and a final covering of grit.

The other half was placed in a bag of damp sand along with a label and

Fermentation method for

placed on one of our heat benches. After 3 months on the heat bench at around 25oC, it will then move to the fridge at around 4oC for a further 3 month period. This warm-cold stratification will help to simulate the natural seasons and speed up the germination process. After the cold period, it will be sown and left outside to germinate in the spring.

Tree propagation is neither a quick nor easy task, germination in some cases can take years. I have learnt that research is crucial for successful propagation as every specimen will vary. I look forward to the rest of my year at Great Dixter and hopefully in that time my tree propagation will come to fruition! ■

Below and bottom, Cormus domestica

‘ONCE YOU SEE THE CHARMS OF CONIFERS - THE TREES, THAT ISYOU’LL BE HOOKED’CHRISTOPHER LLOYD by Ros Crowhurst, Nursery worker

STARTING MY HORTICULTURAL journey at Lime Cross nursery, a conifer specialist, back in 2018 I developed a love for this fascinating group of plants before I learnt of their sometimes dismissed status among gardeners. At Dixter, conifers are embraced, creating a constant for the everchanging landscape of perennials, bulbs, biennials and annuals tying one year’s display to the next. Yew divides up the garden and

creates structural topiary, other conifers such as pine, fir, cedar and spruce are nestled in providing consistent colour and texture all year round. Only shifting slowly as they grow, albeit some more steadily than others, upwards and outwards.

Yew saplings, supplied by Pennell and Sons between Oct 1914 and Feb 1915, created a backdrop and shelter and peacocks began taking shape soon after.

Hedge trimming in the early 1900s

Hedge trimming in the early 1900s

Clipping this hedging every autumn is a mammoth task performed by the gardeners each year and yew equally works its socks off to give rise to these consistent forms and shapes. Found both in the high garden and in the topiary lawn these formal shapes of the yew meet the informality of the meadow in a contrast that sets both off beautifully.

Planted in the 1950s and perhaps the most dominant conifer in the garden is the Chamaecyparis lawsoniana ‘Ellwood’s Gold’ which rises 40ft out of the high garden. A ‘marmite’ plant, as occasionally gardeners can be heard joking about matches or storms seeing it out, others love its impact. It certainly can’t be ignored as it pushes out into the path and rises right out of view for the visitor with feet on the ground. Viewed from the house however, it punctuates the high garden; a real landmark from which to negotiate the view.

A new addition to the topiary lawn this last year is Chamaecyparis lawsoniana ‘Imbricata Pendula’. Differing from the high garden Chamaecyparis, this pendulous form has scaley whip like foliage and will create an almost eery effect as it grows into its conical form, which should contrast nicely with the trimmed topiary structures and tie in perfectly with the smoky ethereal Cotinus display.

Other new coniferous additions can be seen in the Blue Garden where this year pines and cedars were planted in close proximity among the existing shrubs, perennials, bulbs and selfseeding annuals and biennials. This

Chamaecyparis lawsoniana 'Imbricata Pendula' in the topiary lawn

scene is a far cry from the traditional rock gardens or island beds where ‘dwarf’perhaps more accurately described ‘slow growing’ - conifers are usually seen. The caricatural forms of Picea omorika ‘Pendula’ and Cedrus deodara ‘Pendula’ bring a theatrical feeling to the display alongside Astelia and a Phormium tenax and an Abies pinsapo ‘Glauca’. Turn around and the curved branches of Chamaecyparis obtusa ‘Tetragona Aurea’ show off a beautiful soft textured bark.

Any visitor to Dixter will be able to recall interacting with conifers in the old rose garden, used again in a completely different manner, pushing up against bananas, Tetrapanax and Amicia and a visitor or two. Here the needles of Larix contrast with the huge leaves of tropical specimens and combine with Cryptomeria specimens seamlessly. On the topic of his love for conifers, Christo wrote “I shouldn’t want to confine myself to a diet of nothing but conifers”

and feeling the same about roses, “why herd them together?” it seems fitting to find them combined alongside such a diverse display of plants in the Old Rose Garden.

To the west of the gardens, along the boundary, a row of Pinus sylvestris or Scots pine can be found. Our only native pine and one of only three native conifers (along with juniper and yew), these trees tie the gardens conifers into the surrounding landscape. Planted by Christo they had their lower branches removed to create an elegant shape, “Is there a tree with more character, at maturity, than this?”.

In contrast to how conifers are often seen as individuals, unusable in a mixed border, Christo embraced and included them in his tapestry of

planting. Exampled by the Pinus mugo on the Long Border, Christo wrote ‘tulips grow through the gaps in the spring and nasturtiums are apt to investigate them in summer. It is completely different from any other plant around it and I like that.” Recently Lathyrus grandiflorus can be found winding its way through its branches. And this seamless integration of conifers carries on in many areas of the garden - Cupressus cashmeriana creates a perfect shady haven for Begonia and Colocasia and the horizontal form of Juniperus sabina ‘Tamariscifolia’ pushes up against the contrasting more upright forms of Osmanthus and Peonia. Hopefully, as Christo wrote, this allows visitors to experience the charm of conifers and changes perceptions about this varied and ancient group of plants. ■

VISITORS FROM AMERICA 1928-1939

by Roy Brigden, Archivist‘THE BICYCLE BOYS’ 1928

The RHS Lindley Library has a fascinating online exhibition tracking a tour of English and Welsh gardens by two young American landscape architecture students, Loyal Johnson and Sam Brewster. Arriving in Liverpool on the 10th June 1928, they cycled 1500 miles around the country in the course of their three months stay and visited over 80 of the best gardens, large and small, old and new, public and private. They departed from Southampton on the 8th September. The journals and photographs that Loyal Johnson (1904-99) meticulously compiled of the trip as part of his studies were donated to the Lindley Library after his death and prompted The Bicycle Boys exhibition. It tracks their exhaustive itinerary and provides then and now insights into some of the gardens visited. See: www.rhs.org. uk/digital-collections/the-bicycle-boys

The zig-zagging southern stage of their route brought Johnson and Brewster to Great Dixter on the 15th August, having journeyed via Warnham Court, Sedgwick Park House, Lindfield Place and Gravetye Manor the previous day. They then stayed the night at Forest Row and moved on to Penshurst Place and other sites the following day before coming to Great Dixter, staying over at Rolvenden, and heading off to Canterbury on the 16th via Great Maytham Hall, where Sir Edwin Lutyens had incorporated the old walled garden into his re-building works. This typified a punishing and thereby necessarily flexible schedule

Background image: Loyal Johnson’s diary account of the visit to Great Dixter. Top, Loyal Johnson, below, Sam Brewster and the British made Cayouses, both August 1928

Johnson and Brewster’s drawing and photograph of the Sunk Garden

that made advance notification difficult. So it was that, arriving unannounced and late in the day at Great Dixter, they knocked on the door and encountered an irritable Nathaniel Lloyd who let them have a look at the garden. Then, seeing that they were making sketches and taking photographs, he went out and castigated them for not seeking the appropriate permission first. Belatedly realising no doubt that these were not trouble makers but serious and knowledgeable young men, he mellowed and went on to discuss with them details of the Sunk Garden which he had created in 1921, and the finer points of trimming the yew hedges. All was good humouredly recorded in Johnson’s notes. Daisy does not appear to have been at home at the time. If she had been the reception would likely have been rather different: a greeting with open arms; tea, jam and drop scones accompanied by lashings of gardening and family gossip; invitations to return and promises to stay in touch.

THE GARDEN CLUB OF AMERICA, 1929

A year later, on 3rd June 1929, 60 members of the Garden Club of America disembarked at Southampton to begin a two week whistlestop tour of gardens in the midlands and south of England. They came at the invitation of the English Speaking Union, an international educational charity founded in 1918. The Garden Club of America (GCA), predominantly then an organisation for women, had emerged in 1913 when the Garden Club of Philadelphia aligned with similar counterparts around the country to form a national garden club dedicated to educational programmes for the promotion of knowledge and love of gardening. The first president of the GCA, Elizabeth Price Martin from the Garden Club of Philadelphia, Massachusetts, was a member of the 1929 tour party to England. One can’t help wondering whether there wasn’t some linkage between the tour of the Bicycle Boys in 1928 and the GCA the following year, with Massachusetts as a common factor because Loyal Johnson was studying for his master’s degree at university there.

The GCA continues its work today through almost 200 associated clubs across America and many thousands of individual members. It has a substantial historic archive which is housed at the Smithsonian in Washington. In 1999, Christopher Lloyd wrote to the GCA Awards Committee in support of a nomination that John W. Trexler (1951-2019), Director of Worcester County Horticultural Society at Tower Hill Botanic Garden, Massachusetts, be awarded the Garden Club of America Medal of Honor.

A printed report of the GCA’s 1929 visit to England is in the archive at Great Dixter. It is a lively descriptive account of the sites visited and was coordinated by Romayne Latta Warren of the Garden Club of Michigan, and Foreign Gardens Editor of the Bulletin of the Garden Club of America. Her own garden, on the Fairlawn estate at Lake Shore near Detroit, was included in Louise Shelton’s 1915 book Beautiful Gardens in America.

In her summing up of the tour, Romayne Warren writes: Two weeks in English gardens can teach us many things, one

outstanding lesson we learn being the relation of the house to the garden. No matter how simple the plan, an Englishman seems to know instinctively how to attain an intimate and delightfully inviting connection from the one to the other. For this reason they really live more in their gardens than we do.

And garden walls left a particular impression: One could easily write an entire book on the subject of walls in England! They are so beautiful from the outside and do such wonders for the protection and privacy of the owners within. They make living out of doors entirely possible, they shield the gardens from winds, prolonging the flower and vegetable season besides giving a perfect background for planting. We can raise English flowers in our gardens but we cannot grow these lovely old-world walls – moss and lichen covered – and oh! How we long to possess them!

For the last few days of the tour, the party split into five groups and went on separate trips to different gardens. The last, Group E, went to Waddesdon, Aldenham House, Knole, Ightham Mote, Groombridge Place, Great Maytham, Port Lympne and, finally, Great Dixter. Here the visit was a

family affair, with the young Letitia and Christopher playing starring roles, as the report describes: Our last garden was that of Nathaniel Lloyd, architect and author of a book on old English brick. We were greeted at the gate by a cordial host and hostess and their eager, happy children who devoted themselves to our comfort and happiness. We had tea in a pergola in the midst of the garden, then gathered in the great hall to hear Mr Lloyd talk on Medieval Architecture illustrated by the ancient house itself. It is hard to describe the charm of it all, the wonderful old house, the beautiful Lutyens garden and the gracious hospitality. The last touch was from the precious little only-daughter of the family, who presented each of us with a bunch of fragrant pinks gathered by her curlyheaded little brother.

On the long way back to London we were ‘sustained and soothed’ by the delicious fragrance of the little Nosegays and the particularly happy memories of the last garden.

There are two images of Great Dixter and the Sunk Garden, taken during this visit, in the GCA archive at the Smithsonian in Washington. They appear to have been hand coloured and turned into lantern slides for educational purposes by Edward Van Altena’s specialist slide production company in New York.

A decade later, in June 1939, the GCA returned for another tour of English gardens again under the auspices of the English Speaking Union. Correspondence in the archive shows that Great Dixter was on the itinerary. There were 42 delegates, mostly women, many of them wealthy widows with substantial estates or gardens of their own. They included, for example, Mrs Flora Zinn of Lochiel, a Georgian revival house and garden that she had created on the family estate in Virginia. But also in the party was Caroline RuutzRees who had been headmistress of a private girls’ school in Greenwich, Connecticut, and a leading activist in the state for women’s suffrage. Heading up the delegation was Mrs Mabel Kerr, a director of the GCA, whose High Hatch estate, with distinctive early twentieth century house and garden near Portland in Oregon, is now a listed historic site. From there, she sent Daisy a Christmas card expressing fond memories of the trip to Great Dixter ‘and not forgetting you in your much envied gardening costume!’ ■

STUDY IN TWO WORLD-CLASS GARDENS

by Annie Guilfoyle, garden designer and tutorIF YOU WERE to ask my advice on the best way to learn and fully understand the craft of gardening or how to become an accomplished garden designer? My initial response would be to go and study in a world-class garden and surround yourself with experts. Seek out people who are passionate about what they do, the sort of people who feel that it is important to share their skills. Two such gardens are Great Dixter and Chanticleer near Philadelphia, PA and I feel incredibly fortunate to teach the subject of garden design in both of these locations.

Chanticleer and Great Dixter have enjoyed a strong relationship for many years, Christopher Lloyd first visited Chanticleer back in the days when Chris Woods was the garden

director. Christo was so taken with the exuberant, tropical planting by horticulturist Dan Benarcik that it most certainly influenced the transformation of the rose garden into an exotic garden. Thirteen years ago, Fergus Garrett and the Bill Thomas (the current director of Chanticleer) hatched a plan to bring the two gardens even closer together by collaborating on educational programmes. It is not at all surprising that this came about and has been very successful, possibly because both gardens share so many things in common. Both have extraordinarily high horticultural standards, combined with exceptionally imaginative and artistic design and planting.

Gardens are nothing without the people who work there and I think this is the key to why there is such a strong alliance between Great Dixter and Chanticleer. In both gardens the staff and trainees have a strong commitment to learning and sharing, combined with a spirit of excellence which makes these gardens such prominent and influential centres of study.

The Art and Craft of Garden Design is a course that I have been teaching at Great Dixter since 2017. The course is held one-day a month, over nine months and covers the fundamentals

of garden design, guiding students through the entire design process from the initial stages of site survey and analysis through to completing a design and model-making. Each day begins with the all-important garden walk, guided by one of Great Dixter’s horticultural team. This is such a valuable opportunity, being able to study the changes in the garden from month to month, there is usually a focus on what the horticultural team are doing that month and then we all share our thoughts and opinions. I always make a point of saying that just because this is Great Dixter, we can still question and even critique things such as plant choices and colour combinations. Design can be subjective and it is not wrong to voice your opinions about how the garden looks or feels, we can all learn a lot by listening to one another. This course appeals to people who are considering a career in garden design or those who want to re-design their own garden, along with people who want to revitalise their previously learnt design skills. Great Dixter is such an incredible garden to learn from, studying the planting alone is inspiring, not only the plant selection and combinations but also the placement of plants in the garden. Biodiversity and sustainability are vital to the ethos of Great Dixter and form an important part of what we teach. Design and gardening are integral, it is my belief that to be a successful designer you really do need to know how to garden well, with a good understanding the soil and how plants grow.

Chanticleer and Great Dixter have so many similarities and yet so many differences, probably the most obvious is the size, Chanticleer garden covers 35 acres compared to Great Dixter which is 6 acres. The different climate of north-eastern USA means that the plant palette varies noticeably but there are a good number of plants that thrive in both gardens. Another major difference is that at Chanticleer each area of the garden is designed managed by a member of the horticultural team who reports back to Bill Thomas. Every few years there may be some changes made, moving people around and ringing the changes. This allows the

team to make their area very different to the next and from year to year you will notice changes.

Dixter assistant head gardener, Coralie Thomas, with attendees of Art and Craft of Design in the Walled Garden

What these two gardens have in common is an extraordinary artistic flair combined with being leaders in gardening practice and planting design. Education and training are also at the fore of their work, not only shaping future horticulturists but also offering education to a wider audience. I have been teaching at Chanticleer since 2016 and my course generally runs in July, over a period of four days. It is a garden design masterclass where people from all over the USA ‘bring their garden’ to Chanticleer to redesign under my tutelage. This often results in a diverse range of garden situations and climatic zones, which can be quite a challenge, although I do have the incredible Chanticleer garden team supporting me. The course is a mixture of in-studio sessions and lectures, along with time spent in the gardens with the horticultural team. This is what makes the course so special, as the students get to really dig deep into how the gardens are designed and managed. Every student will leave with a finished design and I will occasionally receive photos of the finished results. Occasionally I will have a question like, ‘What do I do about the armadillos in my garden?’ to which I reply, think about moving to Manhattan!

Both courses are intensive and my students do work very hard, as we have to pack a lot into the time allotted. Garden design is a huge and all-encompassing subject, therefore the benefits from learning in such exceptional locations are enormous. Nothing compares with walking, sitting, observing and sketching in a garden such as Great Dixter or Chanticleer, this will allow you to truly appreciate the principles of good design. I have noticed that each and every student will leave my course changed in some way. It may be in the way that they ‘see’ things, or it could simply be that they have taken up sketching again after many years. But of course, it is also a huge learning process for me, every year I am learning more and more about the complexity of these gardens, the extraordinary range of plants and the wonderful people that work there. I might even find the answer to the armadillo question yet! ■

A PLACE OF OPPORTUNITY

by Tom Stuart-Smith, garden designer

FIVE YEARS AGO my wife Sue was in the middle of writing her book The Well Gardened Mind and I was planning to move my garden design practice out of London to a new studio we would built at home. We had already spent the best part of 30 years making a garden here in Hertfordshire that we opened periodically to raise funds for the National Gardens Scheme snd other charities. But we wanted to do more. It felt not quite enough for us to retreat into our cosy rural cocoon and cultivate our garden. Both of us have always been committed to sharing some of the advantages we’ve been lucky enough to have and this seemed to be the moment. We decided to try and build a community horticultural hub where we could welcome people into a beautiful, educational and therapeutic garden. as you might imagine, Great Dixter was a big inspiration.

Dixter has always been a place of sanctuary and beauty but under Fergus’ watch it has also become a place of opportunity, diversity and a beacon of hope. I think first of the dazzling talent of gardens that have been fostered and the inclusion of many people of different abilities on the payroll, then the mind slips easily to images of Fergus in his orange hat marshalling the car parking on a plant fair day, (taking the worst job on offer) or the crazy abundance of the long border, the biodiversity audit, the pit roast venison. The way of doing things and the joy that brings to all involved is every bit as important as the finished result. Perhaps many of us gardeners and especially designers are too focused on what we see as the end product and a little too removed from the process of making things and then caring for them. Dixter is a great lesson to us that what we see has so much more meaning when we understand how it is made. And if something is made with integrity and understanding then the rest tends to fall in to place.

Our project gets going this summer. We already have 16 school visits planned and have made a garden around a beautiful new building where we can hold events and training. The garden is a little unusual in that it’s a filing system of plants. About 2000 so far laid out in a grid so that you can really see how plants behave. We call it the Plant Library and of course it’s very different from anything at Dixter. But it does have a few things in common: burgeoning, eclectic abundance, eye- popping diversity and a seemingly endless capacity to draw people in to its flowery embrace. ■

GREAT DIXTER INSIDE AND OUT

by Karen EdwardsKaren began volunteering as a Garden Steward in March 2023. She studies at the Royal Drawing School and was asked to create a cutaway drawing to illustrate the inside and outside of a favourite building. “I arrived early for my interview and was ushered through the Lutyens Wing into the Yeoman’s Hall to wait. The hall was already occupied by Head Gardener, Fergus Garrett who waved me in. My drawing Great Dixter Inside and Out captures the surreal moment when Fergus joined his Zoom call, introducing himself: “I’m a gardener”.

AN ENTOMOL GREAT DIX TER at

by Chris Bentley

by Chris Bentley

SINCE I WAS A BAIRN I’ve have always been interested in invertebrates. One of my earliest memories is of my aunt showing me her colleges butterfly collection and since then I’ve been fascinated by this whole tiny world. I’ve acquired degrees in Zoology and Invertebrate Ecology and was lucky enough to spend nearly 20 years a Warden at Rye Harbour Nature Reserve, initially for Sussex County Council but more recently for the Sussex Wildlife Trust, where I got to hone my skills. I left this job at the start of 2023 and embarked on (hopefully) the start of a career as a freelance entomologist. However, I felt I needed a little part time employment to help make ends meet and when the chance to work at Great Dixter as a parking attendant came along

I jumped at the chance! I was already quite familiar with the habitats here; a few years ago I helped Andy Phillips, who has done a good deal of entomology at Dixter, undertake a study of bumblebee forage plants and was blown away by the place. Great Dixter is just a wonderful site for invertebrates, with some fantastic semi-natural woodland and grassland, ornamental beds crammed with a huge range of nectar sources, and the old buildings and wood piles which offer nesting, basking and overwintering sites. Why not combine making a bit of extra money with the chance to see some interesting invertebrates? Once I started I always made sure I was equipped with a camera, a magnifying loupe and my trusty pocket net just in case. I was only employed for a couple of months but in

BUILDINGS AND WOOD PILES OFFER

that time I found some really interesting, and occasionally notable invertebrates.

Some of my favourite insects are Spearhorn hoverflies and I had at least three different types at Great Dixter during July and August. These little beauties are so-called Batesian mimics (named after a Mr Bates – harmless insects that pretend to be venomous or poisonous ones, in this case mimicking those skin-heads of the insect world the social wasps). This is partly achieved through colour and pattern, through structure (the extended antennae from which they get their English name) but also behaviour. Hoverflies are often among the most agile of insect aviators but Spearhorns mimic the rather wobbly, indirect flight of wasps to great effect.

Another good find this year was Ectophasia crassipennis, one of a group of flies called ‘Twist-wings’ due to the way they hold their wings. They are internal parasitoids of various bugs, the larvae developing inside the host,

devouring their internal organs before emerging to pupate (the difference between parasitoids and parasites is that parasitoids kill their host, parasites don’t). This species only appeared in the UK in 2019 (global warming anyone?) and while I’ve previously seen it on Jersey, where it is fairly common, this is the first time I’ve come across it in the UK. I recorded it twice at Great Dixter this year: once on Kalimeris mongoliensis on 16th August and again on Sium sisarum in the plant nursery on the 18th.

Box bug (Gonocerus acuteangulatus) used to be extremely rare in the UK, with the only population on Box Hill in Surrey (as you may have guessed this species is associated with Box (Buxus sempervirens)), but has spread to become widespread in England, with records as far north as Yorkshire. I also found the characteristic nymphs with their green abdomens, showing that the species is definitely breeding at Great Dixter.

Another rare species which is becoming commoner in the UK (though

NESTIN AND OVERWINTERING SIT

it is still not what you would call common) is the Large-headed Resin Bee (Heriades truncorum). This species nests in holes in wood and gets its name from the fact it seals its nests with resin from pine trees. It used to be thought that this would naturally limits its range in the UK to areas where pines occur, but it seems that it can also use the resin from man-made structures which are made out of pine such as fences and countryside furniture. I saw this species virtually daily during

my time at Great Dixter, indicating a healthy population.

Last, but definitely not least, and probably the best thing I saw during my time at Great Dixter was Tree Snipe-fly (Chrysopilus laetus). This is yet another species which used to be extremely rare, with the population confined to Windsor Forest and Great Park , and while it is now much more widespread it is still not that common. In fact, this one was the first I have ever seen and it also looks like the first record for Sussex! Larvae are associated with wood mould in rotten trees, often, but not always, in ancient woodland.

All in all I had a great time during my short stint at Great Dixter. Great place, great people and great insects! What more could I ask for?

In February 2023, after nearly 20 years as a Warden at Rye Harbour Nature Reserve, I left and began a career as a freelance entomologist. ■

by Michael Wachter, ethno-botanist and Dixter gardener

by Michael Wachter, ethno-botanist and Dixter gardener

5 THINGS I HAD TO UNLEARN ABOUT ECOLOGY & REWILDING

OVER THE YEARS I have been lucky to learn alongside Fergus, the team and our entomologist Andy Phillips about the garden and its value for wildlife and often when I thought I knew something, I was proved wrong. Here are five of the things I had to re-learn

1. USE ONLY NATIVE PLANTS

There is a big movement that calls for only native plants to be planted in order to boost biodiversity. However what we found at Dixter was that invertebrates don’t mind feeding on native or non-natives but prefer natives for breeding (especially in the case of moths). A double-flowered dahlia can provide a perfect hunting ground for a parasitic wasp or a dark-leaved canna can be a wonderful basking area in the morning for flies. In order to cover a wide range of species a good mix of natives and non-natives seems to work.

2. USE WILDLIFE-FRIENDLY PLANTS

Some animals are generalists, feeding on a wide range of plants and some are specialists only feeding on one or two. We need to cater for both, especially for those with a complicated life cycle. For example, only bumblebees are heavy enough to trigger successful pollination in birds foot trefoil, showing their close and necessary relationship.

3. THERE IS NO PLACE FOR HUMANS IN THE WILD

Nature and wilderness are no place for humans is an approach with colonial roots and undermines indigenous human culture. Humans have always gardened and altered the ecosystem around them. It is the extractive way in which humans interact with land that is harmful, not humans per se. Conservation is humankind’s attempt to protect nature from ourselves.

4. SOME PLANTS ARE BAD

Ragwort, creeping thistle, dandelion, docks and nettles are all important plants. Some provide hunting grounds, some food, some homes. Creeping thistle for example has an incredibly high nectar content that is available late season.

5. BIRD FEEDERS & INSECT HOTELS ARE GOOD FOR BIODIVERSITY

Bird feeders can become a hotspot for pest and diseases and are really only effective in the depth of winter. In fact our greenfinch population has been badly affected by dirty birdfeeders. If you have one, make sure to clean it every so often. Insect hotels often come with a roof which stops them from decaying. That makes them static. They then lack the ability to transform, decompose and change in a way log piles or deadwood can. Log piles are dynamic, alive and don’t cost anything.

SO, WHAT TO DO RIGHT?

We often get asked that question. What I hear over and over again is the thinking that overall complexity will boost biodiversity. Complexity can mean a long and diverse flowering season, various heights in the borders, undulation not just with plant heights but soil profile as well, complexity in terms of habitats, materials, etc.

Don’t feel sad about having a small garden, every garden is important. A small garden can be a stepping stone while a bigger garden forms a complete habitat. Five small gardens next to each other can form a complete habitat. One thing is for sure; leave the chemicals in the shed! And don’t feel guilty about growing dahlias because a garden is a home for bumblebees and butterflies – but it’s also a home for you. ■

May 2023 in the Peacock Garden

May 2023 in the Peacock Garden

May 2023 across the Topiary Lawn

May 2023 across the Topiary Lawn

20232024

SRALO *

RUO G R EATDIXTERSC H

IN THEIR OWN WORDS

TALITHA SLABBERT

UK Christopher Lloyd Scholar 2023-24I’VE BEEN AT DIXTER for a month now, and it still feels a little surreal. Reading back through my notes, it’s remarkable how nervous I was in the build-up to coming here, feeling out of my depth and unsure of what to expect. Yet from the moment I arrived I’ve been made to feel so welcome, and the warmth and generosity with which we’ve all been received has surprised and heartened me. I would like to extend my heartfelt thanks to the entire Dixter team for this welcome, and to everyone who has made it possible for me to be here. In particular, I would like to thank Club 22 for sponsoring me– I feel incredibly lucky and grateful.

The garden itself has been magical. Even late in the season, it is a welter of colour, form, and texture. Each day, every change in the weather or in the light, every corner turned reveals something new, a colour combination or a little vignette. Each day after work, I wander around the garden drinking it in, looking up plants I don’t know, noting the planting combinations, and occasionally being trapped by Neil, the Dixter cat.

The learning, too, has been an overwhelming and exciting inundation. This first month, we’ve done a lot of meadow work – cutting, raking, and bagging up grasses and wildflowers gone to seed from the orchard meadow, the topiary lawn, and other patches of grassland. Fergus explained to us how the best time to cut a meadow for strewing is in fact before the seedheads fully ripen, as this means you carry away more seed on

the stalks, which can then ripen and drop when strewed in a new location. However, this doesn’t allow for much seeding on the existent meadow, and so for our meadow maintenance at Dixter we cut after the seed has ripened, allowing some to fall on site, and carrying some of it away to strew on a new field. We did this with some of the clippings from around the horse pond, where the meadow is rich in autumn hawkbit, strewing them onto the topiary lawn and the orchard garden, which should hopefully help to establish hawkbit in those areas.

It was fascinating to be shown the contrast between different patches of meadow, resulting from differences in

SARAH SEYMOUR

SARAH SEYMOUR

history or topography – where there used to be an old compost heap, for example, or a bonfire, the grass is far more lush, outcompeting the wildflowers. Under the trees, too, the clippings are less good, as the falling leaves add too many nutrients to the soil, allowing grasses to dominate. Clippings from these areas went on the compost heap, which is in itself a structure to behold! We piled the clippings on in layers, working from one end to another, and trying to keep the shape square (grass is draped slightly over the edges to keep them straight and firm). We also added a layer of sheep’s wool (for additional nitrogen), stretching it out thinly with our hands. The smell of the lanolin was lovely.

In some ways, this theme of nutrient density characterised a lot of my learning this month -- how it builds up, how we can manage it as gardeners, and which plants we can expect to see at different nutrient levels. These considerations informed much of our ‘crack gardening’ this month, by the ticket office, on Christo’s terrace, and on the kitchen drive, where Michael Wachter explained Grime’s triangle to us. The gist of it was that in an area where the build-up of organic matter gradually increases the nutrient levels in the soil, certain competitor plants will eventually outcompete their neighbours and dominate that area, unless we intervene. And so, on the kitchen drive, we combed through the gravel, removing the rampant clover, plantains, and grasses, and carefully saving the ox-eye daisies, dandelions, and especially the tiny grass-like seedlings of

the beautiful Dierama pulcherrimum, or Angel’s fishing rod. I loved the attention and care with which we treated each little pavement crack or patch of gravel, looking at it as though through a magnifying glass, and editing it accordingly. Also exciting are the things that might grow in the cracks – woad and Eryngium giganteum to be sowed on Christo’s terrace, along with perhaps creeping thymes as plug plants; and for the ticket office, verbascum and hollyhock.

Amidst all of this, the hedge cutting season has begun. This is a task I thoroughly enjoy. Perhaps it appeals to my slightly obsessive side. The hedges here are old, so we treat them with respect, following their organic ebb and flow, lines sagging a little here and there, like the lines of the roofs around them. In places, we’ll cut a little less hard, leaving things softer, so that a few years’ cutting might even out some of the imbalances and blend together some of the more extreme undulations. But (and this seems to be the way with a lot of things at Dixter) it is a sensitive and attentive process, responsive to each individual plant and the way it wants to grow, and mindful of how our actions today might ripple on into the future.

Talitha hails from the Western Cape in South Africa, and moved to England in 2017 to complete a PhD in English at Oxford University. During the pandemic she rediscovered her childhood love of plants, and left academia to pursue a career in horticulture.

WILL LARSON

The Chanticleer USA Christopher Lloyd Scholar 2023-2024

THE NORTH AMERICAN ASTERS in the genus Symphyotrichum are some of the most striking autumn-flowering plants in the borders at Great Dixter. They are also some of my favorite plants to see in the wild, occurring in a variety of different habitats throughout the New England region and in my home state of Maine. As the 2023-24 Chanticleer scholar at Great Dixter, I have been given a project to work on during my time in the garden. My focus is on more unusual propagation methods, making small divisions, and caring for the newly propagated plant material growing in the cold frames. I have been splitting very small aster divisions, mostly cultivars of Symphyotrichum lateriflorum, S. cordifolium, S. laeve, which produce clumps of small basal shoots in late fall. These asters, native to woodland edge habitats, happily come into their own in the borders at Great Dixter in September and bloom all the way through October.

The asters are first lifted and split down into small, simple divisions by using two hand forks back-to-back and gently prising the clump apart. A single aster clump can easily provide twenty small divisions by carefully feeling for natural breaks and slowly teasing the stems apart by hand, washing the roots as needed to untangle the intermingled stems. Each single-stem division will have multiple eyes, the buds from which new growth will emerge, on the basal portions of the aster. These look

SARAH SEYMOUR

SARAH SEYMOUR

like small purple nubs which protrude from the crown area where stem meets root. These simple divisions can be split down further into one and twoeye splits, taking sections of shoots or dormant buds with some roots attached and potting them into small pots or cell trays. The main stems can also be split down the middle to produce split-stem divisions. A sharp pair of secateurs and a scalpel are useful for these operations, which require a clean working area with good organization to quickly pot on the small divisions, so they do not dry out. Using these methods, I split down two clumps of S. lateriflorum ‘Dixter’s Chloe’, a seedling of S. lateriflorum ‘Chloe’, with darker coloration found at Great Dixter, into 150 basal cuttings and 50 small divisions. These divisions are watered and then moved into cold frames, where they are carefully looked after to ensure good rooting.

In the Peacock Garden, the aster bloom builds into a great blue and purple crescendo, accompanied by many other perennials native to the eastern and midwestern US states. Species of Eutrochium, Veronicastrum, and Vernonia, native to woodland edges, floodplains, and tall grass prairies, erupt in tall pink and purple flowers above the asters. I particularly like the pairings of lemon yellow Oenothera with the cool periwinkle and lavender blues of the asters, which saturate with intense color in the dusk right after the sun has set. Different aster species can inhabit a wide range

of habitats, even seemingly inhospitable sites in saturated bogs or in rocky cliffsides. Nearby Dixter in the salt marshes at the Rye Harbour Nature Preserve, the UK native Tripolium pannonicum thrives in saltwater flooded conditions. At Chanticleer Garden in Wayne, PA, native asters can be found in a wide variety of different habitats, including woodland species such as Eurybia divaricata which relish the shade. Other asters at Chanticleer, such as the cultivars of Symphotrichum oblongifolium, originate from drier prairie and open sandy bluffs in the southern US. It is a joy to see the diversity of these plants succeeding in different habitats, and I am grateful to Chanticleer for providing me the opportunity to see asters in new habitats in the wild and in gardens hundreds of miles away from their native range.

Will lives in Portland, Maine, USA, he has a wealth of experience with wild plant communities from his work with conservation organisations and native plant nurseries.

ERNIE WELLER

Christopher Lloyd Scholar 2023-2024

MY HORTICULTURAL JOURNEY started in 2020, the year after taking my A Levels in Photography, Graphic Design and Business, when I designed and built my own smallscale tropical-style garden at home.

I realised that all my design projects in school and college were focused on the natural world, my GCSE art piece looked at the connection between pollinators and flowers, painting wildflower meadows, and my A Level projects were based on natural patterns, organic structures, Kew Gardens and the Natural History museum.

When I discovered gardening all my main interests seemed to click together. At the start of my gardening journey, I thought design would be my main career, but I felt it would be best to understand gardens better before going into design.

For the next couple of years, I worked at Fairlight Hall, Athelas Plants and Mantel Farm, I also volunteered for Crowhurst Environment Group and studied at Hever Castle for my RHS Level 2 Diploma.

While working at Fairlight Hall I enjoyed working with one of my first mentors, Philip Leighton, who first introduced me to the idea of applying to work at Great Dixter.

In March 2022, I started volunteering for the Garden Team, and I have since developed a passion for the practical side of gardening and being a part of a team to create the ideas right from the start, being able to appreciate the outcomes all the more for it.

Design is still important to me, but I now wish to express this through physically

creating designs in a garden setting, following the processes from start to finish, from seed to flower, from compost heaps to soil mixes and so on.

I want to extend my thanks to Philip, Club 22 for making the Christopher Lloyd Scholarship possible, and everyone who has helped me along the way as I truly enjoy every aspect of gardening, the connection to the land and the people I work with. I feel so lucky to have discovered this appreciation of the natural world, gardens and design at a young age and I am keen to help encourage others to as well.

Ernie from East Sussex has been part of the Dixter family since March 2022.

MATT PADBURY

MATT PADBURY

NACIIM BENKREIRA

The Ruth Borun Scholar 2023-2024EVERY GREAT ADVENTURE has a prelude. And this is one of gratitude. A month has flown by, and I would have never thought that I would be able to garden and study abroad at Great Dixter. Really want to give my deepest thanks and gratitude to the Borun family for their support in making this dream become a reality. I truly feel honored and blessed to be at Great Dixter as the Ruth Borun Scholar for 2023-2024. I also want to say thank you to Sandy Flowers, Leigh Merinoff, Clare Adams and all the gardeners/country heroes who have taught me along the way.

Quick info about me. My name is Naciim Benkreira. I was raised in a big multi-cultural family in the capital of USA Washington D.C., (also known as Chocolate City). Gardening, floristry and farming are huge passions of mine that overlap in all aspects of my life. I believe gardens have a crucial role in to solving our environmental problems, social justice and land access. Regenerative farming and teaching others to garden will always be my roots. I transitioned into the world of horticulture because gardens have the ability to inspire anyone. Especially bring us together. Flowers and trees allow us the moments in space and time to be present.

OVER THE POND AND THROUGH THE YEWS

After much anticipation of packing and saying good byes to friends and family, I jumped on a plane to go to England. I was very fearful about the adventure