SPACES PLANNING LEARNING

We believe the learning environment has a profound effect on the educational outcomes for all pupils. If you would like to join us to improve these environments worldwide we would love to hear from you. This magazine is a not-for-profit journal and is the official magazine for A4LE (Europe). It is given free to European members and distributed to 8,000 A4LE members globally in e-format. If you would like to contribute articles to the magazine or purchase additional copies please contact us.

Editorial Board Murray Hudson

Production Editor Clare Cook

Sub Editor Christopher Westhorp

Design clockstudio

For A4LE (Europe) Terry White

CONTACT:

magazine@planninglearningspaces.com

SPONSORS: Gratnells

Academic freedom and unlimited holiday: inside the Brave Generation Academy (BGA)

Gijs Bruggink reveals the school focused on tackling nature deficit disorder

Dr Robert Dillon celebrates the importance of colour in teaching and learning

Irena Barker discovers how nature is helping to heal young people’s trauma and adversity

PHOTO CREDITS:

Cover: Gesher School

P4: Gratnells

P6–7: Gratnells

P8–13: Brave Generation Academy

P14–19: ORGA, Ruben Visser

P20–24: Naomi Davies

P26–29: Jim Stephenson

P30–32: West Lab

P34–48: Gesher School, David Brown

P49: David Strudwick

Everything you need to know about the chemical storage guidelines

Case study: explore the relationship between pedagogy and space at the Gesher School

Professor Stephen Heppell reflects

Terry White Principal Education Advisor, Planning Learning Spaces and Planning Learning Spaces in Practice (PLSiP)

Guest Editor

As we move beyond the first quarter of this century, we are starting to see a deeper understanding of the relationship between pedagogy and space and the social, emotional and educational outcomes that environments for learning can make possible. There is universal acceptance that the spaces and places in which our children and young people learn should be ones that develop their ability to live, work and participate in a world where they will need to communicate effectively, collaborate, think critically, be creative and problem-solve.

Making learning personal and placing students at the heart of a more inclusive and innovative model of education promotes the design of learning environments that can enhance a sense of belonging and well-being for all learners and staff. Engaging young people in an authentic and relevant curriculum experience creates a sense of agency over their own learning. Learners are motivated to enquire more deeply and investigate projects that have meaning for them and can connect to the natural world through a local, national and global learning community.

The Brave Generation Academy (BGA) in Portugal (p8) has developed a more flexible and personalised approach to learning. Students have autonomy and responsibility for developing – with specialist course managers – bespoke programmes of study through an online platform. Students work at their own pace, exploring their own passions and interests as an integral part of course provision. Learning coaches are central to the success of this approach and they use technology to monitor student progress and support all aspects of the student’s academic, personal and social development. The South African entrepreneur Tim Vieria and his

wife Lidia founded the academy to provide a more personalised approach to educate their own children. Their breakthrough solution has developed a model of inclusive learning hubs for 30 students that can be created in a range of existing and refurbished premises.

The importance of designing environments for learning that are more closely related to nature is explored through the work of ORGA architects at De Verwondering primary school in the Netherlands (p14). The school’s name translates as “a sense of wonder” or “amazement”, referring to the sensation of curiosity in children when they explore the natural world. The holistic design is reflected in the seamless connections between internal and external spaces and the material composition of the building. The presence of nature is more than visual in the interior design of the school and awakens all the senses, especially that of touch, smell and hearing. The outdoor classroom facilitates curriculum activity throughout the school year. The children exercise stewardship over the environment in which they live and learn, the produce they create and even the animals that live on the school grounds.

This theme is further explored through the work of the Harmeny Educational Trust near Edinburgh (p26). The trust provides therapeutic support and education for young people suffering the consequences of trauma and adversity. It has developed a new vocational Learning Hub and located it within its woodland estate with direct access to tree-lined external spaces within the landscape.

In Vibrant Classrooms, (p20) we are reminded of the importance of the use of colour in enhancing learning, emotional well-being and the cognitive engagement of young people within their learning environments.

The design and use of colour schemes can create welcoming spaces and a sense of belonging in the wider range of spaces and places now being developed in schools. Good Chemistry (p30) draws attention to the important critical issues of health and safety that we need to consider when designing more-specialist areas in schools.

In this edition, we also share a case study of the work that the PLSiP team has developed in partnership with Gesher School in London (p34). It is an all-through school for children and young people who are differently able and who learn differently. The school believes that every young person should be profoundly well known, and that the learning should be personalised and informed through project-based activity and the passions and interests of the learners.

The approach to learning is trans-disciplinary, and teachers, support staff, therapists, parents, carers and the community all work to ensure that each young person has an individually tailored programme of care and support throughout their journey of learning through the school.

In On Reflection (p50) my longstanding colleague and friend Stephen Heppell reminds us that the “pace of change in learning is gathering momentum”, and his words resonate throughout many of the transformational initiatives that we feature in this edition, and is “creating a place where everyone can be their diverse selves”.

In making learning personal we all have a part to play in designing for the future and not building for the past.

The new Labour government has announced £135 million to fund the conversion of primary school classrooms.

It is predicted that England is likely to have around 400,000 fewer pupils of primary school age by 2029, and therefore will have “spare” spaces that could serve as nursery rooms for pre-school children.

Labour inherited the last Conservative administration’s plans for childcare expansion, which, from September 2025, will see children from the age of nine months receive 30 hours of funded care each week.

The government estimates that the conversion plans would create around 100,000 new spaces in 3,000 new nurseries, which is a 6 per cent increase on current spaces. In October 2024, schools were invited to bid for a share of the first round of funding to deliver 300 new or expanded nurseries.

Paul Whiteman, general secretary of the National Association of Headteachers (NAHT), welcomed the plans and said there was a “clear logic in using free space in primary schools to expand nursery provision”.

He added: “Having the right space is one part of the picture, and it will be equally important that there is a strong focus on attracting more people into the early years workforce.”

However, Christine Farquharson, an associate director at the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), said that the funding may “nudge the market in a different direction”, but won’t transform it.

She continued: “Targeting provision at childcare ‘deserts’ could help to expand access to childcare in underserved areas – but a sensible plan would take into account the likely local demand for childcare, not just the (lack of) supply.”

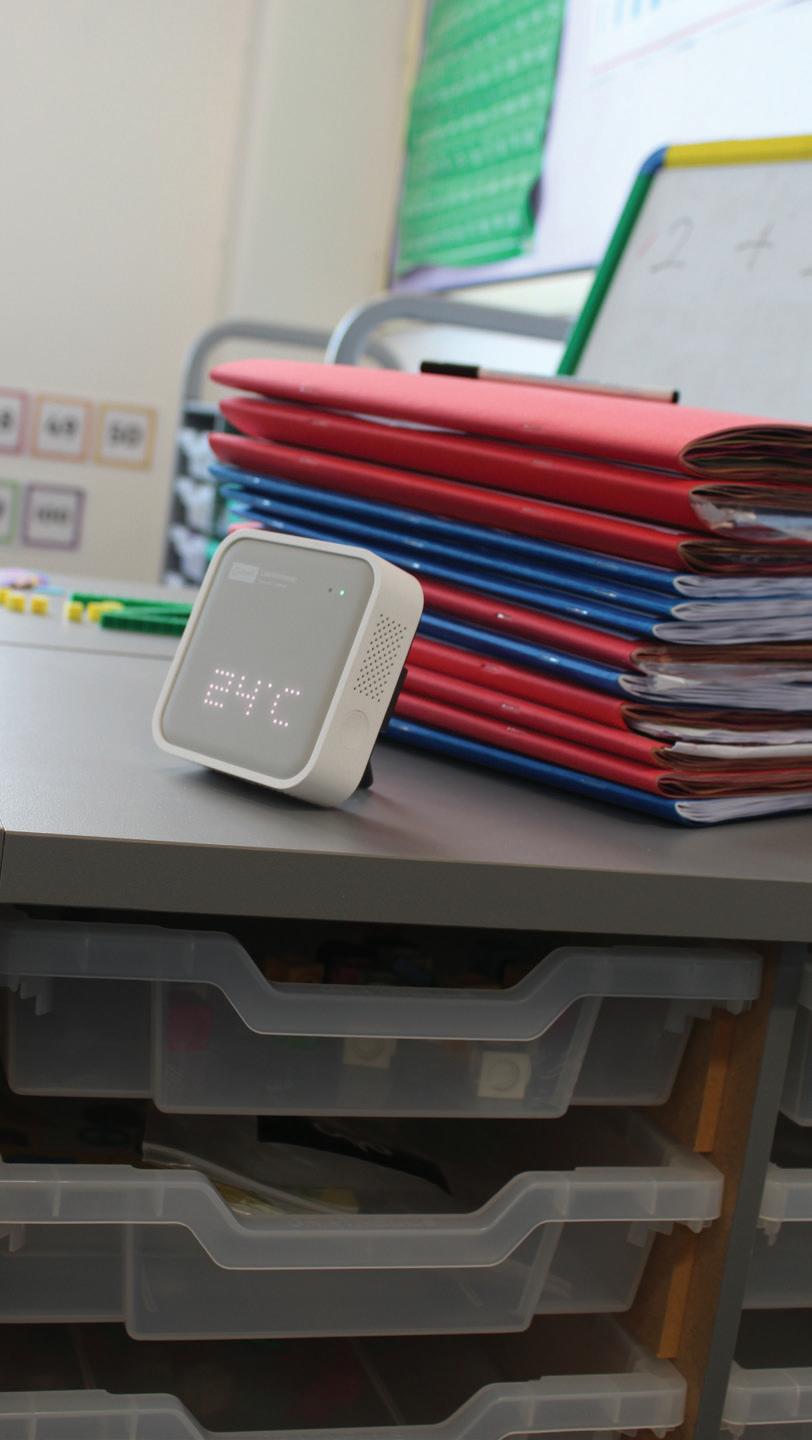

Researchers at the University of York are set tomeasure the impact that hot weather has on classrooms in the UK.

The action comes as climate change is leading to more frequent and extreme heatwaves worldwide. In the summer of 2022, the UK experienced five heatwave periods, with record-breaking temperatures of over 40 degrees Celsius in England. The Met Office’s UK Climate Projections predicts that the country will continue to see summers that are between 1 degree Celsius and 6 degrees Celsius warmer.

UK guidance suggests that if employees are not carrying out physical work the temperature of the workplace environment should be at least 16 degrees Celsius. However, there are no legal maximum working temperatures for schools in the UK.

Researchers at the University of York believe that many school buildings in the UK are not made out of suitable materials, and glass and concrete in newer schools contribute to “heat island” effects that can make schools dangerously hot.

Children are particularly vulnerable to high temperatures. When it is very hot, the human body produces sweat to cool itself down. However, children do not sweat as much as adults and are therefore much less able to regulate their body temperature, increasing health risks and posing significant challenges for teachers and school staff.

Research shows that temperatures above 24 degrees Celsius can compromise reaction time, processing speed and accuracy through changes in heart rate and respiratory rates.

Paul Hudson, senior lecturer in Environment and Geography in the University of York’s Department of Environment and Geography, said: “We are seeing more and more record-breaking heatwaves, and extreme weather overall, in the UK. We will have to start proactively thinking about how we need to change how we live and work for the climate we will have rather than the climate we had.

“Even when temperatures do not reach headlinegrabbing highs, unexpected increases in temperature can harm the way pupils learn, how they behave, and their health, depending on what they are doing. It is not just the effect on pupils; when teachers work in classrooms that are too hot they can become fatigued or lose concentration, potentially putting themselves and the children in their care at risk.”

Researchers will involve teachers, parents and pupils in the study, which will not only measure how hotter temperatures are impacting schools but also what can be done about it.

“It’s one of the only schools that makes Mondays not horrible.”

For most students, total academic freedom, hot-desking and unlimited holiday is but a dream, but for those enrolled at BGA, it’s a reality. Irena Barker finds out more.

It all started with a hut. At just 70 square metres, with a thatched roof and a wooden floor, BGA’s first learning hub didn’t really resemble most people’s idea of a secondary school.

Close to the ocean near the seaside resort of Cascais in Portugal, with a nearby swimming pool, tennis and horse-riding academies, it sounds more like a luxurious Airbnb.

But despite this apparent holiday atmosphere, BGA hybrid school is a serious business.

In just four years it has grown from a handful of learners in that first seaside hut to 1,400 learners around the world. They follow the British international curriculum (with IGCSEs and A-levels), the US curriculum and a number of accelerated higher education pathways.

Starting from 7th Grade, learners attend a network of 60 small, local hubs where they access a tailor-made online learning platform, which is remotely overseen by expert teachers known as “course managers”.

“Learning coaches” are on site at each hub to ensure students are supported and inspired, both in their academic work and personal development. They also help them to get involved in non-academic activities and community work off site.

Students of all ages, who all work in the same space, are encouraged to interact at the hubs too, supporting each other and developing their social skills.

BGA aims to give students autonomy and responsibility, helping them to follow their passions and strengths and create entrepreneurial young people. Students can move at their chosen pace through their courses, with the learning coaches using an app to monitor students’ progress with their online work.

They take breaks when they want and there are no fixed holiday periods, so learners can leave on a trip whenever they like – as long as they are on track with their work.

South African entrepreneur Tim Vieira and his wife Lidia, who were looking for a more flexible and personalised way to educate their own three children, founded the academy three years ago.

Vieira has been well known in Portugal since he first appeared in 2015 as a “shark” on the Portuguese version of the reality TV business show Shark Tank, and is also now – rather impressively – standing in the country’s 2026 presidential election.

Vieira says that with the BGA project he “wanted to make an impact that would be quite democratic”.

“My children were my first ‘guinea pigs’, and if it worked for them then I could expand it and it sort of all worked organically,” he continues.

“I can’t even say that I had this big idea. I wanted to make education more flexible, with a platform, using technology. I wanted to have the schools in the right

places, close to home or where they surf or play rugby.”

He was adamant that he didn’t want to build new hubs from scratch. “I wanted to use what existed; find a sustainable way of doing it,” he says.

The result of this ethos is learning hubs accommodating up to 30 learners situated in equestrian centres, marinas, office buildings, empty shop units and, increasingly, within traditional schools.

The majority of the hubs in existence are in Portugal, with others spread across eight other countries from Mozambique to Thailand and the USA. One is expected to open in Cambridge, UK, and plans are afoot for a hub in Australia as well.

Inside, the hubs are simply furnished, with a main coworking space where students must hot-desk at least 20 hours a week, although many do more. Learning coaches are not provided with desks, encouraging them to move around between learners, and there are glass-walled “focus rooms” for quiet work or personal meetings. A kitchenette provides the basics for hot drinks and sustenance, while carpets reduce echo and

distraction. There is a large blackboard for people to make notes on, and inspirational quotes on the walls.

“It’s all really very simple, we’ve never really got into a huge design,” explains Vieira.

In the spirit of BGA, learners arrange the furniture how they like. While the spaces are quite spare and undistracting, learners sometimes add their own personal touches such as a bunch of flowers, Vieira remarks.

As the BGA concept expands around the world, it is hoped that more hubs can be opened in existing schools – there are already hubs at schools in the cities of Wellington near Cape Town and Durban in South Africa. But Vieira talks of the challenge of this, including “difficult conversations” about changing existing spaces: “Schools don’t like letting go of their furniture but in our mindset sitting like you would in a normal school doesn’t work because we have a lot of peer-to-peer.”

He says some of the “legacy schools” in South Africa can be very traditional, even likening some of them to “museums”: “A lot of schools are going to have to rethink the space they’re using... Some of them have

these massive libraries that aren’t being used. Tradition is a good thing but it’s also something that holds you back.”

Luis Brito e Faro, BGA’s director of expansion, believes that opening future hubs within existing schools is going to be the best route for future growth to enable them “to reach as many learners as possible”.

“We want to equip other organisations to do what we are doing,” he says, but he admits many schools in Portugal have “a very conservative mindset”.

Reaching the unreachable

But the BGA concept is not just about educating the children of globetrotting parents – middle-class kids disenchanted with restrictive school systems and wannabe surfers and pilots. It is also turning out to be a way of educating children in adverse situations where education is not readily available.

Through its non-governmental organisation (NGO) Brave Future, BGA has opened a hub at Kakuma in Kenya, the biggest refugee camp in the world with 200,000 residents. Around 16 young people there are using the academy’s learning platform.

Six children in Kakuna are also studying with BGA independently, including one who is ploughing through his IGCSE maths course, completing a year’s worth of learning in just four months. Even away from the war zones, BGA is run as a non-profit, with those able to afford to pay subsidising those who cannot.

A typical hub might include 15 learners paying full price, ten paying half fees and another five who attend for free, says Vieira. The mix of learners from different socioeconomic backgrounds is a huge benefit to everyone, he adds: “The children from disadvantaged backgrounds tend to be more hungry for success and that hunger rubs off on some of the others.”

From a personal point of view, the true success of his initial educational experiment is surely how it has turned out for his first “guinea pigs”, Vieira’s own children. And it certainly looks like they are all confidently striking out and following their passions as intended. One son is starting at UC Berkeley in California to study global studies this year. Another has moved to Durban in South Africa and plans to study out of a BGA hub while he works towards his pilot’s licence. His daughter, meanwhile, is happily studying for IGCSEs at her local

hub in Cascais, where the BGA headquarters is situated.

But perhaps it is the positive feedback from other students that provides the even-greater proof of BGA’s success.

Victoria, aged 13, who attends the Caldas da Rainha hub in Portugal, says of her experience: “I always got distracted at school and didn’t get good grades on the test. At BGA I can do whatever subject I want, whenever I want.”

Fernando, aged 15, who lives in Porto and attends the Anje hub, enjoys the freedom and absence of conventional teachers. “In traditional schools I used to have a big problem with teachers; I would get really mad at teachers... because the learning coaches are young, it’s a lot easier to create that connection... they can understand what you’re feeling,” he says. “It’s one of the only schools that makes Mondays not horrible.”

An education revolution?

Given what he has achieved with BGA, will education play a part in Vieira’s presidential bid?

It’s clear that if he is elected in 2026 he would like to change the conservative mindset that he believes

“I always got distracted at school and didn’t get good grades on the test. At BGA I can do whatever subject I want, whenever I want.”

holds back education. He says: “In education we keep doing the same things over and over, we put in more money, we waste more money, we’re not investing it wisely, then we’ve got all these stakeholders that are not happy.

“We’ve got teachers that aren’t happy, we’ve got learners not happy and parents not happy and yet we keep doing the same thing... and it’s not improving.”

Whether or not Vieira wins in the election, maybe Brave Generation Academy is the education revolution the world has been waiting for.

Tim Vieira founder of BGA

Designed to connect students with nature, Gijs Bruggink, coordinator at ORGA architect, explains that De Verwondering primary school in the Netherlands is like no other.

Today, children spend large amounts of time behind screens. TVs, computers, tablets and smartphones form their windows onto the world, and there seems to be an increasing separation between the natural world and the environment in which our children grow up.

Author Richard Louv describes the consequences of this separation as “nature deficit disorder” in his excellent 2005 publication Last Child in the Woods. In short, he states that spending a large amount of time in sterile and understimulating environments that lack the enriching, inspirational and recovering effects of nature can lead to both cognitive and physical issues in children’s development.

In addition to this worrying effect on a young person individually, it’s also worth considering their roles as future leaders. Will a person that grows up with little affinity with the natural world possess, as an adult, the sense of responsibility needed to take care of the planet?

These considerations led to plans for the creation of a new type of school building in the city of Almere in the Netherlands: primary school De Verwondering, designed by the firm ORGA architect.

The school name translates as “sense of wonder” or “amazement”, referring to the sensation of curiosity in children that is triggered when they come into contact

with the natural world. Any parallels with Rachel Carson’s timeless publication from 1965, The Sense of Wonder, are coincidental, but both very much speak to the same sentiment.

In the early stages of the project our design team found a lot of common ground with clients Prisma and the municipality of Almere. Their ambitions towards bringing nature into their education were clear, and a biophilic exploration with the project team provided a great foundation for a holistic design process. Nature was going to play a big role in the educational programmes and this was to be reflected in the space, appearance and material composition of the school building.

Architects Daan Bruggink and Guus Degen set two goals for the inclusion of various connections to

nature in the building design: first, to create a healthy educational environment, beneficial for learning by triggering curiosity and a sense of exploration in the pupils; second, to create more awareness in children and start fostering a sense of responsibility for nature as they grow up.

The way the spaces in the building work together is analogous to the system of natural habitats: shared spaces in nature that allow species to both thrive and coexist. Pupils spend most of the time in an “ecotope” with children of the same age – the classroom. Three clusters of classrooms, including a small gym and an outdoor classroom on the roof, form “habitats” where pupils meet others of adjacent ages. A couple of times each day the children venture outside of the familiar

Improvements in the maths test scores over a sevenmonth period were over three times higher in the biophilic classroom.

surroundings of the habitat and into the larger biotope of the school complex. For example, to the central gathering area for school meetings or to the playground outside, where they can learn more about nature and the world.

The design offers a strong physical connection to nature, with approximately 85 per cent of the aboveground construction of the building consisting of natural materials. The hybrid wooden structure is part timber frame and part mass timber, utilising the specific advantages of each building method. All the insulation materials in the walls and roofs are bio-based – either wood fibre, flax or straw. Some of the interior walls contain a little window at kids’ height, exposing the insulation and showing the pupils that the building is actually made from plants.

To both maximise the effect of the material and showcase all the different ways in which wood can be used, paint or varnish was avoided. Natural oil finishing sufficed to protect the wood, bring out the textures and the grain, and still allow the smell of wood to be present in the interior. The peeled tree trunk columns that support parts of the central area seem to hold special biophilic appeal because most passers-by fail to resist the urge to run their hands over the smooth wood texture.

Nature has more than a visual presence in the interior of school; it’s also there to be touched, smelled and heard, providing a more-rounded biophilic experience. Climbing plants grow into green walls on both the interior and exterior walls, and a system of hatches and roof vents enables fresh air to flow through the building,

...spending a large amount of time in sterile and understimulating environments that lack the enriching, inspirational and recovering effects of nature can lead to both cognitive and physical issues in children’s development.

letting in the scents from the garden playground, like freshly mown grass or the damp smell of rainfall. Part of the lessons take place in the outdoor classroom or in the playground, regardless of the season or weather conditions. Different types of animals live on the school’s grounds and are cared for by the pupils. Planters in the playground are used to grow edible plants. These learning experiences teach the children about the natural cycles of the seasons or about growth and decay. And just as important, they learn that when you nurture and care for nature you’re rewarded with beauty – and produce.

Comparing the De Verwondering school building to a natural organism isn’t a huge stretch of the imagination. The structure provides its own energy from renewable sources distributed across the year using innovative buffer systems. A natural ventilation system lets it breathe on its own. The trees and living walls provide a protective layer of shade and greenery that changes along with the seasons. Similar to humans and some animals, the wooden facade will age and gradually turn grey. In short, the building will slowly but surely evolve, following the natural cycles and, like many things in nature, will only grow more beautiful over time.

The building was completed in 2021 and the school’s principal reports notable differences from the previous school environment. The children seem to really feel at home and love the playground. Teachers see that pupils are able to get rid of their excess energy by exploring and playing outside, after which they are able to focus better on their schoolwork once back in the classroom. School attendance ratios have improved and there are fewer signs of hyperactive behaviour.

Although subjective in nature, these findings indicate real potential for an education system that’s closer connected to nature. Objective research confirms this; a study at the Green Street Academy charter school in Baltimore, USA, measured the effects of a biophilic classroom compared to a control classroom without natural features. Among other findings, only 35 per cent of the students reported experiencing stress compared to 67 per cent in the control group. Improvements in the maths test scores over a seven-month period were over three times higher in the biophilic classroom. Since completion, the building’s design and its biophilic concepts have resonated throughout the world of sustainable architecture. It has won several Dutch architecture awards and both the European and global Stephen R. Kellert Biophilic Design Award in 2023. Our firm has been actively promoting how to reconnect to nature through architecture, both in publications and through guided tours of the building. It’s our sincere hope that this design provides an inspirational example and results in many more biophilically designed school buildings appearing all around the world.

Reprinted with permission from the Journal of Biophilic Design. Project information:

• Architects: ORGA architect, Daan Bruggink and Guus Degen

• Commissioned by: city of Almere and Prisma

• Advisor on education: Bladgroen, Evert van Kampen

• Contractor: Van Norel Bouwgroep

• Structural engineer: Lüning

• Technical advisor: Nieman Raadgevende Ingenieurs

• Interior design: Projectum

• Landscape design: Goed Geplant

Introducing colour design into classrooms takes time, but small changes can build momentum and create a big impact in teaching and learning.

Designer, educator and leader Dr Robert Dillon explores the underappreciated role that colour can play in teaching and learning.

The integration of colour within classroom environments is a powerful tool that extends beyond aesthetic appeal by playing a critical role in enhancing learning, emotional well-being and cognitive engagement. The strategic use of colour, informed by psychological insights and educational principles, can create an optimal setting for mind, brain and education (MBE).

The characteristics of colour Colours can elicit psychological responses that can influence students’ emotions and behaviours. Although the research continues to emerge from schools, we already have enough information to show that using the right colours can bring additional benefits to students. Some studies have concluded the following about these colours:

• Blue is calming and serene, ideal for spaces dedicated to reading and deep focus.

• Green symbolises nature and balance, fostering relaxation and concentration.

• Yellow is vibrant and stimulating, suitable for areas of collaboration and creativity.

• Red is energising but should be used sparingly to avoid inducing stress.

We can instinctively feel a quality colour palette when we’re in one; it fits together without feeling like a circus or a bag of skittles. Done with intention, a coherent colour palette in classrooms impacts both learning and emotional well-being.

Specific colours can make learning materials more stimulating, potentially improving attention and memory retention. For example, in marketing red is considered the colour that most easily captures attention and stands out in memory – it’s bold and can evoke powerful psychological responses, but as with all colour choices you can overdo it and that reduces its impact.

Thoughtfully designed colour schemes create welcoming spaces, fostering a sense of belonging. Many use blue to create this feeling, but beyond colours it could be textures, patterns, symbols or artworks that resonate with the students or express their values.

Optimal colour choices can alleviate visual fatigue, aiding in sustained focus. Studies vary on which colours can bring out these desired effects, but it is generally understood that avoiding high contrast and intensely complementary colours in your decorative scheme will reduce eye strain.

Certain colours can have therapeutic benefits for students with special educational needs (SEN), enhancing concentration and reducing anxiety. Our understanding of SEN continues to grow and as it does we should continue to research the impacts of colour. Classroom design should support all students, and the colours that we choose could impact individuals with SEN quite differently, which we need to be mindful of when following the general research on colour.

Choosing your perfect hue

So how can you craft a coherent colour palette for your classroom?

Your palette should combine a calming base colour with vibrant accent colours to highlight key areas, which will support memory retention. There should be harmony and balance within the space, with reduced clutter and distraction to foster cognitive engagement, as well as colours with cultural and contextual relevance that can

enhance students’ sense of connection to their learning environments.

Ultimately, the colour palette should enhance both aesthetic and functional aspects of classroom design. It needs to be easy on the eyes, relaxing minds and bodies – and, as a result, setting students up for academic success.

The history and tradition of many schools might well mean that they already have an associated colour palette. Logos, school uniform colours, websites and printed materials all provide clues on how to design classrooms to sync with the school. When introducing a new scheme, teachers don’t need to be constrained by any colours already identified with the school, however, they should remain coherent.

Strategic colour application in various classroom zones can maximise their effectiveness, allowing them to sync with the learning purpose of that particular zone, and

creating the right learning energy for students, such as the following:

• Collaboration zone: energetic colours like orange to stimulate group dynamics.

• Reading zone: calming blues for concentration and comprehension.

• Independent zone: greens for harmony and focus in individual study areas.

• Quiet/reflective zone: soft tones for a peaceful atmosphere conducive to reflection.

• Guided group zone: warm colours to foster engagement in teacher-led activities.

• Makerspace zone: vivid hues to spark creativity in hands-on learning areas.

• Presentation zone: neutral backgrounds with colour accents to focus attention during presentations. By thoughtfully integrating colour into classroom

designs, educators can create environments that not only enhance learning outcomes but also support the holistic well-being of students, thereby contributing to a more enriching and effective educational journey.

Introducing colour design into classrooms takes time, but small changes can build momentum and create a big impact in teaching and learning.

A colourful celebration

In 2024, schools’ storage-solutions manufacturer Gratnells is celebrating the importance of colour in the classroom by commissioning the artist Naomi Davies to produce a painting containing 40 of its iconic school trays, each in one of its distinctive colours.

Based in Cambridge, Naomi embraces colour not only in her paintings of the university’s colleges, street scenes, cafes and landscapes, but also in her own life.

“Colour’s massively important to me,” she says.

“There are certain colours that I just don’t feel happy having around and there are other colours that make me happy. Certain colour combinations really zing for me.”

From flame red to grass green, via deep-sea blue, mushroom brown and silver, the painting presented a special challenge for Davies. Handwriting the labels was a nerve-racking process with plenty of scope for mistakes, so she worked on two versions at the same time.

The deceptively simple-looking task was actually painstaking, requiring careful measurement, while colour matching watercolours with the real-life trays was also a challenge.

But, coming from a family of teachers, she says she was delighted to be involved: “My husband was a science teacher for 25 years and brought the old Gratnells trays home when the school replaced them. We stored our games in an old one.

“I absolutely value the design of the Gratnells tray, they are just great. I’m not just saying that. They’re just one of those genius ideas.”

Colours can elicit psychological responses that can influence students’ emotions and behaviours.

IF YOU’RE A MEMBER OF A4LE

If you’re a member of A4LE Europe, you’ll get a print copy of this magazine as part of your membership.

If you’re a member of A4LE in another region then you’ll receive an e-journal version of this magazine free of charge.

If you’d like a print version, it’s available for the reduced rate of £30 a year.

IF YOU’RE NOT A MEMBER OF A4LE

Subscriptions are available from £30 a year for three editions, published during the Spring, Summer and Autumn school terms.

Europe

£30

Rest of the World

£45

Send us an email with your name and address and we’ll do the rest!

magazine@planninglearningspaces.com

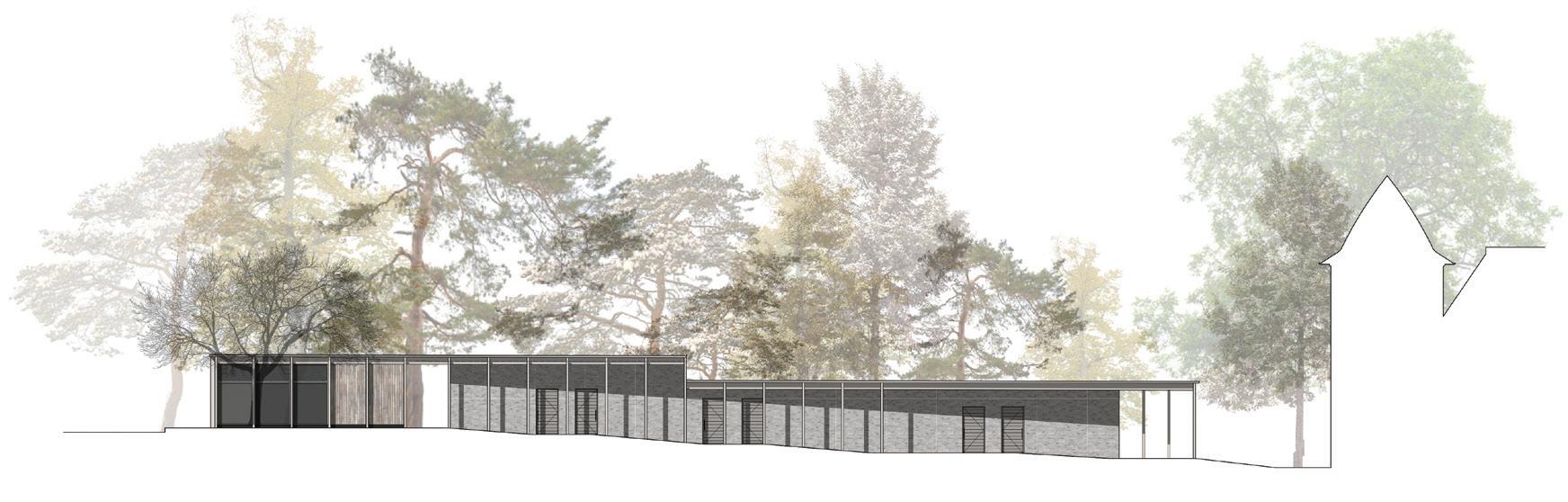

When building new provision for older teenagers suffering from trauma and adversity, the Harmeny Education Trust put well-being at the heart of its plans. Irena Barker takes a look inside.

Every day, Harmeny Education Trust provides therapeutic support and education to children suffering the consequences of trauma and adversity. This is why, when it set out to build a new vocational learning centre on its 35-acre wooded estate, well-being was at the forefront of its mind.

Making the most of its calm, natural setting in Balerno, near Edinburgh, the trust wanted to create a nurturing space that would allow it to extend the outdoor learning provision and welcome older teenagers for the first time.

The resulting, new, single-storey Learning Hub has huge windows set off by elegant larch timber cladding and muted grey brick that complements its natural setting. All rooms have views outside into the woods and overhead glazing provides extra natural light and a connection to nature.

Wherever students are in the building, there is immediate access to tree-lined outdoor spaces, emphasising the therapeutic and practical benefits of nature. Inside, there are the facilities to provide a new hands-on technology, arts and design curriculum: four classrooms including wood and bike-repair workshops, an art space and one for secondary learners mean children can be equipped with practical career skills. A foyer, bathrooms and staff accommodation are also included in the design.

Mandy Shiel, head of education at Harmeny Education Trust, describes the new hub as “thoughtful and highly functional”.

“Through the Learning Hub young people who have had some of the most difficult starts in life now have the continued care and learning that they need to unlock their potential and thrive,” she adds.

Sarah-Jane Storrie, director of Studio SJM, says that she hoped the design of the learning spaces would – as well as nurturing their well-being – help children’s overall engagement in education and ability to focus.

The £3.1 million low-profile hub, designed by Loader Monteith with Studio SJM, contrasts with Harmeny Education Trust’s historic Grade II listed main building nearby, with its white render and slate-roofed tower.

But the build of the L-shaped hub was not without its challenges: Loader Monteith had to work hard to place it within the woods with minimal environmental disturbance and a number of tree preservation orders had to be worked around. In the end, just three trees had to be relocated to make the project work. Loader Monteith also emphasised making the building low on energy consumption – something vital to Harmeny as a charitable organisation. Timber-framed and -clad, the Learning Hub includes high levels of insulation, solar panels, ground source heat pumps (GSHPs) and mechanical ventilation with heat recovery (MVHR) systems.

Inside, Studio SJM provided expertise in developing nurturing spaces attuned to students’ learning needs; the classrooms and vocational learning areas have neutral interiors and pastel colours designed to be engaging but not overstimulating. Entry ways are designed to

offer a sense of welcome and create an informal, safe atmosphere from the start. The vocational spaces have been designed to mimic real-world workshop or creative environments to familiarise the students with future workplaces. Artificial lighting in warm tones supports the incoming natural light.

Matt Loader, director at Loader Monteith, says that placing well-being at the forefront of education design was “the key to unlocking learning environments that serve their students well”. Providing for and prioritising their social and emotional needs allowed them to receive “the best education possible”, he adds.

Wherever students are in the building, there is immediate access to tree-lined outdoor spaces, emphasising the therapeutic and practical benefits of nature.

Chemical storage is a serious issue and recent official guidelines stress the importance of doing it properly. Murray Hudson explains.

Getting it right is not an option: it’s a must.

The new guidance* for science department chemical stores now goes further than the expected advice on leaks and fires. It says that if schools notice that chemicals of “security concern” have gone missing, or there is “suspicious behaviour” relating to such chemicals, they must report that to the local police or even an anti-terrorism hotline.

While schools may not house the vast quantities of chemicals typical of industrial settings, careful management is still needed to ensure complete safety. So what does good chemical storage look like in a school?

It should be possible to store all chemicals in the same store, including toxic, corrosive and flammable ones. There is no need for separate cupboards; when amounts are small, they can all be kept on shelves in a secure space. There are only two exceptions: radioactive substances and gas cylinders need to be kept separately from the chemicals store and away from each other.

The chemical store needs to be a separate room opening directly into the prep room, close to the dispensing area and the prep room fume cupboard. If possible, the store should have an outside wall for easier ventilation, which will help with cooling provided the wall is not exposed to the sun. Size matters too: the floor area should be more than 12 square metres for a small 11–16 secondary school and more than 20 square metres for a school of around 1,000 pupils. The floor area will need to be even larger for bigger schools and those teaching post-16 students.

Walls, floors, ceilings and doors will need to be fireresistant for a minimum of 30 minutes. Schools also need to beware of false ceilings, where the space above is shared with neighbouring rooms – the chemical store and prep rooms rooms need to be fully fire-stopped to prevent the spread of fumes, smoke and flames.

Voids under the floor can also pose a problem and floors need to be sealed to prevent leaks of liquids, fumes or smoke travelling throughout the building. There should also be a viewing window into the room so that anyone working in the store can be seen. Schools need to keep careful track of keys to the storage room and who has access to them. Only the technician(s), head of science and site staff should have direct access to the chemical store room. Teachers should not have routine direct access to the chemical store.

The surface of the floor should be sealed at the edges, waterproof, resistant to chemicals and non-slip. To contain spills, the floor should slope slightly to the back or centre of the store so that liquids don’t trickle outside. Don’t install drains – hazardous chemicals should be prevented from entering the drainage system. Because schools store relatively small amounts of chemicals, there is no need for a sill across the doorway to contain spills. In fact, it is more likely to be a trip hazard than anything else.

For a more modern aesthetic, with both easy maintenance and protection against humidity and chemical spills in mind, consider powder-coated metal shelving. Keep shelf depths shallow, at around 150

millimetres, to ensure that packets and bottles are not stacked more than two deep. Bulk containers, such as Winchester bottles, should be stored on the floor in deep Gratnells trays.

Where trays containing bottles of stock solutions are in use, and the store is big enough, there should be racks for these trays. A limited amount of flammable substances (up to 50 litres per cabinet) can be stored in a metal cabinet inside the chemicals store; it has to be able to withstand fire for at least 30 minutes.

The light switch should ideally be situated outside of the room. There should be no other electrical equipment in the storage room, including power sockets. There is no requirement for any electrical items to be ATEX (or spark-proof) rated. Chemical storage is a serious issue and recent official guidelines stress the importance of doing it properly.

The ideal temperature for the store is10–25 degrees Celsius. There should be no heating pipes or heaters within the store itself. The ventilation rate for storage should be more than two air changes per hour, rising to five air changes an hour if someone is working in there for an extended period of time (making the store a working place rather than a store). Place extractors at both high and low levels, as the majority of fumes involved are heavier than air. These should operate 24/7 all year round. Ducting routes must be as direct as possible and fans should be positioned outside the main building, taking into account any downdraughts.

In conclusion, there is a lot to think about in setting up your school chemical store, but there is plenty of advice and guidance out there to help you to get it right.

While schools may not house the vast quantities of chemicals typical of industrial settings, careful management is still needed to ensure complete safety.

*SYC – Secure Your Chemicals, Education, Home Office, 2012. Further advice direct from CLEAPSS (UK), cleapss.org.uk, or SSERC (Scotland), sserc.org.uk

At VITTA Group, we empower educational institutions to realise their curriculum vision by transforming plans into fully functional, strategically aligned learning environments.

Our unique methodology and expert guidance combine curriculum alignment with resource provisioning to ensure that every learning space supports the educational goals and engages students effectively.

• Curriculum-Driven Design

• Equipment and Resource Alignment

• Comprehensive Resource Mapping

• Transparent Delivery Framework

• Continuous Improvement

Find out how our 7-Step Methodology can help bring your curriculum strategy to life. Contact our team on 0333 996 1611 or visit our website, vittagroup.com/curriculum

Your Implementation Partner for New Curriculum

Gesher School in London is a high-quality, innovative, all-through, Jewish faith, special school for young people with language, communication and social challenges. In this study, David Strudwick, a school principal and founder of Beautiful Mind Learning Labs, reports on the effectiveness of the Planning Learning Spaces in Practice (PLSiP) model for developing holistic and systemic educational change at Gesher. The model explores the important relationship between pedagogy and space and the evidence that reveals its impact on improving learning outcomes.

I will show RESPECT to the environment around me

Look after playground equipment

Use school resources with care

Take care of my uniform and wear it to school each day

Make positive choices with my behaviour

I will ENGAGE with my education

Come to school every day and be on time

Be ready to participate and enjoy learning

Work hard and try to listen carefully to others

Be responsible for doing my homework and reading assignments to the best of my ability

I will ACCEPT others and their di erences

Respect that other pupils might have di erent ideas and backgrounds to me

Try hard to learn about the other pupils and what they like and don’t like

I will CARE for others in my community

Treat all pupils and adults in the school with respect

Include others within my games and learning

I will HONOUR my physical and mental wellbeing

Eat healthy food at school and only bring healthy food to school

Use IT equipment safely and only go to sites I have been told to use

Engage with the therapies that the school provides

Speak to an adult when I have a worry or a concern

Inspired by its core Jewish values THE SCHOOL has created REACH goals – a motivating and positive basis to GUIDE behaviour within the school environment.

Gesher school educates learners with challenges – such as autism, ADHD, dyslexia and Down’s syndrome –who require a tailored educational experience to meet their needs. Gesher’s approach integrates therapy, authentic project-based learning, life skillls and well-being.

The physical spaces and places in which children learn can be influential and should be designed to meet the needs of all learners in a community and to reflect the vision, values, ethos and culture of a school. Gesher School, working in partnership with the PLSiP team, has developed a range of design principles to ensure its vision becomes a reality, in all aspects of the school’s life and work.

Inspired by our core Jewish values we have created our REACH goals - a motivating and positive basis to behaviour within the school environment. The name itself is aspirational and embodies the high expectations we have for all our pupils

the design process for the newly remodelled school for all generic and specialist teaching spaces, therapy areas and the external landscape. In the redeveloped school environment there are occupational therapy and sensory spaces and practical, applied-learning settings, which include a state-of-the-art makerspace studio where students can apply authentic real-life learning. This case study shows both the process and impact of the collaboration that brought students, staff and the community together to rethink and redesign the use of their learning spaces.

Innovation and creativity have been at the heart of

The PLSiP team collaborated with learners, staff and the wider community to empower, engage and create an inclusive sense of ownership for the spaces and

places that they would design together. Learners were engaged in the initial design workshops, giving true agency and value to their thoughts on the environments in which they would love to learn.

A key focus at the beginning or front end of the PLSiP design process is how to translate the school’s vision, values and ethos into the learning behaviours and activities that create the design principles for the new spaces. Headteacher Tamaryn (Tammy) Yartu highlighted: “Collaborating with the PLSiP team has been instrumental in shaping our school’s environment to cater to the unique needs of our students, fostering a dynamic and purpose-driven atmosphere. Their commitment to innovation, while carefully considering the functionality and meaning of space for our students,

has been evident through every stage of the design process. We look forward to continuing this journey with them and are excited at the prospect of the inspiring spaces we will create for our students!”

A learning ecology has evolved that combines Gesher’s distinctive and aspirational approach to learning with the PLSiP Design Framework. The process recognised the complexity of developing a holistic, integrated and ambitious vision where solutions were not just a series of new, separate, siloed spaces but included the creation of appropriate learning environments that enabled and reinforced the organisational model that Gesher wished to build.

Ecology is used intentionally for living and learning well

The significant impact of relationships and space is fundamental to the way we live and learn. Consider the power that a relationship can have on your life in terms of what feels possible. As a young child, many of us will remember how a parent, teacher or friend made us feel safe. Similarly, space has an impact on how we behave. This is not always obvious, but try cooking a meal in a kitchen where you don’t know where anything is, and you might end up feeling frustrated. At Gesher, ecology is intentionally utilised and created. In many schools teachers just arrive in the room without considering the space’s impact on learning. Picture teachers who sit young people in rows but want collaboration, or who say they want independence but don’t give access to resources. At Gesher, following its work with PLSiP, it is at another level: spaces are zoned and considered purposefully; learning is seen as a relational, co-created act where young people and adults collaborate together with authenticity and agency.

Throughout my visit there was a wonderful sense of young people’s needs being met. This was partly due to thoughtful communication, children being known, and rigorous systems based on meeting needs. The staff see behaviour as communication. I was curious to discover how thinking around communication and learning was translated into the learning spaces. As you enter a room there is a sense of what is being learned through your project and immediately there is a clear space for your personal belongings. There is an organisational principle behind each area – an expectation, a purpose. Spaces that connect to emotional needs – for social connection, privacy, calm and independence – were all in the service of learning and living well.

From personal visual timetables to a recognition that we all learn differently and have different abilities, an ongoing approach to making learning personal is the antidote to the “one-size-fits-all” ethos with everyone passively facing the teacher throughout. This has not just happened – there is a progression and themes at play throughout the school.

Throughout my visit there was a wonderful sense of young people’s needs being met. This was partly due to thoughtful communication, children being known, and rigorous systems based on meeting needs. The staff see behaviour as communication.

This has been expertly steered and the desired learning behaviours have been surfaced and translated into the layout through the school’s collaboration with PLSiP. You will see the team having ongoing conversations around space. This might be scaffolded by a checklist or the need of a young person as described by a therapist. As you walk around the school there is a sense of everyone wanting to broaden what is possible for a child and that these young people need change, as long as it is carefully scaffolded. The scaffold might be preparatory, like a social story, or it might take the form of a wonderful chef expanding the palette of what the children will eat – but they are not playing it safe, they are learning to make sushi. Again and again, a child is known, and his or her horizon extended.

There is a playfulness between the children and the adults, with some adults being like a “professional big brother or sister” and reflecting a palpable sense of family. As Jody, a Year 6 teacher, stated: “There is fun and safety that we reflect for the pupils, allowing us to connect to real-world and sensitive issues.”

New and existing staff were impressed and felt engaged with the learning environments that were being developed. All staff felt they were better equipped, compared to their previous settings, to meet the full range of learning needs for students. The partnership with PLSiP has listened to the adults and students and transformed their ideas into design principles that make a reality of their vision.

Every space is used thoughtfully and is continuing to evolve. Where existing box classrooms needed to remain in the newly remodelled school, they have been paired together to create improved collaboration and extended-learning opportunities. Younger children used a horseshoe table while older students used small individual tables arranged into a group in a variety of agile ways. There were independent spaces away from groups that could be personalised. Reading zones promoted private nooks, which responded to student ideas and focused on building a love of reading.

Outside of the classroom, the types of tables for eating at lunchtime were chosen to support social interaction. Corridors support students’ self-regulation to become alert, organised or calm through different

activities. There is a sense that the space itself is a form of provision map, which moves from freely accessible to a more-specialist temporary need. I observed staff using the space and each other to quickly intervene and maximise the learning opportunity. The links between pedagogy, curriculum experience and space are clear and explicit. For example, the way that project-based learning was enhanced through a zoned makerspace developed in partnership with PLSiP.

A space for collaboration or a boardroom; a space for media, including lights, podcasting and editing; a space for factory and production; and a space for reflection, where the experience could be connected. This is not a school that just wanted a shiny new space, but a school where such a space could be seen to enhance the learning and teaching process. The school is continuing to adapt and develop authentic learning behaviours that prepare young people for life.

The impact of the work with PLSiP was recognised and, interestingly, the impact is not just on the learning spaces but also on the wider ecology and intentionality of the spaces. Staff have ideas about where they could improve further and the school is far from being a place to which people just turn up and use a space without awareness – it is a can-do team that finds solutions.

Authentic learning through project-based learning underpins a context for learning, relationships and space

The school has invested in a project-based approach for much of its learning. The development of flexible spaces to support this form of learning can have a significant impact on its effectiveness. This has been thoughtfully scaffolded through external support and teamwork, where staff plan in small teams and create a context in which student learning and agency can emerge rather than be prescribed in advance of the project.

The approach, as with other areas, is continuing to evolve. The school makes effective use of exhibitions, where the process and product of learning are brought together. The learning spaces are appropriately zoned and support independence. There are small, dedicated areas for making within the classrooms, and this is further enhanced by the school’s makerspace.

One team member described how students developed a puppet show and filmed the final production, alongside a further behind-the-scenes film that revealed how things were made. When children travel from a long way away the use of digital work can increase parental and wider family access. What was palpable was the energy of the project. The children care about their learning and are motivated by their projects, whether they are linked to space, dinosaurs, a fashion show or a Dragon’s Den-style entrepreneurial experience. The agency for learning, as with the spaces, connects

A focus on the flexibility of spaces is recognised in the range of ways that learning can pivot through a project and within a single day.

to the school’s vision. The curation of learning is clear and involves students. The corridor could become a rainforest or a fashion show runway. A focus on the flexibility of spaces is recognised in the range of ways that learning can pivot through a project and within a single day.

Authentic learning continues into Gesher’s life skills curriculum (its life skills scheme is The Bridges, which the school developed themselves), which is taught in a room that is based on a studio flat with a bed, kitchen space and dining table. Learning and living are again interconnected at Gesher, with therapeutic work being used to enhance this further.

There is a playfulness between the children and the adults, with some adults being like a “professional big brother or sister” and reflecting a palpable sense of family.

Therapy and academic learning interconnect in a symbiotic manner within ecology

So often there is a separation of therapy and learning into separate silos of expertise. In many schools, this means that teachers get therapeutic reports and multiple ideas that they cannot immediately see how to implement.

Similarly, the ability of a therapist to understand the demands of the classroom and curriculum means they lack a bridge to the world of the children they are supporting. Gesher’s proactive approach connects therapy and school learning, and its use of space and relationship helps to utilise the magic of this. As a result, at Gesher you will see therapists in classrooms. Their ideas and expertise are used in planning and it means that the therapist can show the teacher or the teaching assistant (TA) what something looks like in the moment rather than waiting for a meeting.

Having a dedicated occupational therapy (OT) space and two occupational therapists is having a massive impact. The OT room is open and engaging. It’s a room that is popular and that you want to investigate due to the porthole windows. This use of movement for living and learning is too often lost in the mainstream school and Gesher has much to teach the education sector. Art therapy is similarly valued, with the art therapist supporting art and design, circle time activities and the development of physical spaces. Therapy is contextualised within a clear global or generic need such as learning, communicating and focusing. By doing this therapy is normalised as a form of helpful learning.

Leadership matters

If we consider culture to be what we do, around here we can’t just tell people what to do and expect this to be sustained. Culture emerges and is as much about what people do when they are not being told as when they are being directed. If leadership is making something happen that wasn’t going to happen anyway, Gesher exudes leadership with a creative staff team who are imagining possibilities and who value the diversity of their team’s skills.

Tammy, the school’s headteacher, is a wonderful mentor for new teachers. After a day with her, I have expanded my thinking, been introduced to new things and guided along the way. The leadership of working with Terry White and Bhavini Pandya from the PLSiP

team has also had an impact. PLSiP translates needs into learning behaviours and design principles, which bridges the gap between education and design. This ability to create a new system is critical to the way that PLSiP works because it brings energy, new eyes, fresh ideas and capacity to any team examining their learning spaces.

A school like this ensures that leadership is not defined exclusively by an individual’s role. When TAs can lead the learning in the school, you have a different culture. This is partly made possible by the strength of relationships, the quality of partnerships and by the clarity of the blueprint that enables group members to take risks in alignment with the school vision. The style of communication, whether inward- or outwardfacing, shows coherence and ambition. Gesher communicates the need for change in education beyond its locality. These voices for transformation are a super representation of the school’s leadership and they raise the question of where the school is heading next. I know I cannot wait to return and see its developments. Gesher and PLSiP have developed an approach that is transferable to other schools. It is systemic and holistic. It supports the development of starting conditions that will impact on both ecology and culture. Enquiry and research regarding such work is essential if we are to enable practice-based evidence to emerge from schools that are innovating in response to the limitations of the status quo. This is an antidote to the narrow distillation of what has worked historically and it shows new forms of learning, with evidence, which will result in meaningful change across the sector. Following pandemics, wars and lightning-speed advances in technology, we need to be supporting learning processes and partnerships that move us forwards and discover learning in a new context.

Gesher and PLSiP have developed an approach that is transferable to other schools.

In our recent publication Planning Learning Spaces we describe an agenda for change that illustrates the need to design for the future and not build for the past. All those who collectively worked with us to produce this practical guide shared their own successful experiences of the approach required to design and deliver sustainable contemporary educational facilities. We all endorsed the same message: “You can’t successfully design educational spaces unless you fully understand the learning and teaching practices they are intended to support.”

Reaffirming our approach

In setting out this agenda for change, as a team we have recognised the critical importance of working directly with and engaging teachers, all staff, students and the local learning community at the front end of any design process. In this way they are empowered to become the “creators and not just the consumers” of the new or remodelled learning facilities that are appropriate for their school.

The Planning Learning Spaces in Practice Design Framework has been developed to work in partnership with schools to support their own collective review process for planning, designing and implementing their environments for learning.

The Planning Learning Spaces in Practice (PLSiP) team has a passion for excellence in developing the spaces and places in which we learn.

Our process of collaborative engagement starts, as it must, with the vision, values and ethos of a school to ensure there is a shared, well-defined and collectively understood agenda for change. In this way we also create certainty, understanding and support for the transitions to new learning environments for all staff, learners and the wider community.

Bhavini Pandya: Co-Director of PLSiP.

Terry White: Co-Director of PLSiP. Cheryl Hill-Cottingham: PLSiP Administrator.

David Strudwick is Director of Beautiful Mind Learning Labs – bringing agency for educational innovation. His passion is enabling young people and adults to create possibility as they navigate uncertainty. He has founded schools and worked as a principal in the state and independent sectors in England and internationally.

David is a published author with expertise in leadership, learning spaces, pedagogy, curriculum design and wellbeing. He co-created the Blackawton Bees project, which resulted in the world’s youngest published scientists, and also the I, scientist programme, which has been shared in countries around the world.

The pace of change in learning is gathering momentum. For a couple of decades, compliance replaced creativity in our schools and colleges, and opportunities for music, theatre trips, invention, adventure, discovery days, imagination and ICT projects diminished.

Ofsted led the charge, imposing a “right way to do things”, crushing the professional ingenuity of teachers as well as the agency and joy of children. Inevitably, this has hemorrhaged both teachers’ employment and pupils’ attendance.

The impact on school design and learning spaces has been profound: we have barren silent corridors, desks in rows, upright chairs, rigid uniforms, and dull science labs that look like classrooms. When Michael Gove axed the impressive Building Schools for the Future Programme in England, he even took a moment to ban “curved walls”.

But mercifully, this is not the case everywhere. Creative teachers have other ideas, and many didn’t enter the profession to impose compliance and follow scripts, but rather to promulgate a love of learning. There’s much we can learn from their successes in our learning space designs.

For example, the corridors in a Welsh school I visited are themed and dressed around current movies, with annotated scripts, revealing images and crafted artefacts displayed. When I was there, the film was War Horse and the corridors were dressed to include a huge papier-mâché horse’s head.

A school in Silkebor, Denmark, that I enjoyed time with has a running track painted around its corridors and an expectation that anyone who steps onto the track has to run, even the teachers. It was the children’s idea and they arrive rapidly, happy and alert because of the stimulating en-route exercise. Local companies have copied this initiative.

In other schools, arriving at a classroom offers a variety of furniture from Harkness tables to standing desks. The variety ensures that everyone arrives early (more choice for earliest arrivals!) and promulgates an everfresh learning experience.

Of course, the growth in outdoor learning is the success story of recent years everywhere. In our local primary school, every child has an extended science-rich experience on their beach. Nature has no standardisation; there is learning, complexity, surprise and science everywhere.

The swing back to ingenuity and creativity is driven in part by economic imperative. We need an imaginative, collaborative, problem-solving, creative, engaged population to solve the emerging challenges that surround us. Designing seductive learning spaces for that outcome is a wholly more-complex task than designing them for compliance. Creating a place where everyone can be their diverse selves, apply knowledge freshly and surprise others with their work is the design challenge of our lives, and it has already started. How very exciting.

Professor Stephen Heppell is CEO of Heppell.net and holds the Felipe Segovia Chair of Learning Innovation at Universidad Camilo José Cela, Madrid.

A4le is an interdisciplinary association of professionals working at the intersection of learning and place. We belie ve that the design of environments for learning must ensure a meaningful, empowered and creative world for the student, enabled by teachers and communities of learning Our approach is inclusive and fully recognises and responds to the voice of all learners throughout the design process.

Standard membership is £120.00 per year, and includes:

• Printed copies of Planning Learning Spaces Magazine

• Log in access to the A4le Europe and International websites

• Free on-line attendance to all A4le forum meetings during 2025

• Exclusive access to ar ticles and research papers through the website

• Reduced ticket prices for all A4le Europe Conference e vents in 2025.

We have a Lead Membership Category of £200.00 per year with a range of additional benefits as Lead Members, please contact Terry White for more details at terry.white@a4le.eu.

Schools can enjoy all the benefits of A4Le Europe as associate members at no cost by sharing innovatory projects that the y have de veloped and are willing to make available through the Association for Learning Environments. Please contact Terry White for more details.